Abstract

Using the assertions of the social exchange theory, this study investigates the moderating effect of supervisory role in human resource management (HRM) practices and employee engagement relationships. This study used a cross-sectional survey design and collected data from 280 employees in Bangladesh’s readymade garments (RMG) industry. We tested the hypothesized model in SMART-PLS software through a structural equation model (SEM). An importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA) was also performed to prioritize managerial actions. According to our findings, HRM practices have a significant relationship with employee engagement in the RMG industry, and the supervisory role of line managers moderates this relationship. Specifically, employee engagement increases in tandem with positive supervisory roles and vice versa. The IPMA analysis demonstrates that training and development is the most important determinant of employee engagement. Firms will benefit from increased employee engagement if line managers are empowered to implement HRM practices. This study expands the employee engagement literature by investigating different aspects of HRM practices in a globally dominant labor-intensive industry. It highlights the priority areas of HRM practices to foster employee engagement. However, the study is limited to Bangladesh’s RMG industry, though the findings are more applicable to labor-intensive manufacturing industries. Therefore, a full-length generalization across industries might not be feasible.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Employee engagement is a job attitude that signifies employees’ active involvement with their job. It reflects job satisfaction and involvement, encompassing employees’ cognitive, emotional, and physical investment toward citizenship behavior in the workplace (Macey & Schneider, Citation2008; Saks & Gruman, Citation2014). Extant literature documents that successful engagement of employees increases firm productivity and decreases employee turnover, thus contributing to firms’ financial performance (Harter et al., Citation2002; Sun & Bunchapattanasakda, Citation2019). Favorable outcomes of employee engagement at the employee and organizational levels call for research (Gavin, Citation2020). However, the debate on how employers can promote employee engagement remains unsettled (Young et al., Citation2018), and researchers have called for further studies to examine antecedents of employee engagement and job outcomes to improve organizational functioning (Barreiro & Treglown, Citation2020; Kwon & Kim, Citation2020). In response to calls for systemic academic research, this study examines the linkage between human resource management (HRM) practices and employee engagement. There is a growing interest among human resource professionals in understanding the impact of HRM practices on employee engagement due to their continuous contribution to competitive business improvement (Shuck et al., Citation2014; Sydow et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, it investigates the moderating effect of the supervisory role as a crucial interpersonal resource, given that interpersonal resources can moderate the relationship between organizational resources and individual outcomes, which, in this research, are HRM practices and employee engagement, respectively. In particular, this study seeks to address the following research questions: ‘How do HRM practices impact employee engagement, and does the supervisory role moderate this relationship?’

HRM practices encompass dynamic processes to achieve competitive business success through effective people management practices and policies (Dessler, Citation2019; Dhamija et al., Citation2019). HRM practices play a pivotal role in fostering employee engagement by intervening in work design, facilitating reciprocity in mutual help, and providing social support to employees (Strobel et al., Citation2017). As employee engagement is a significant outcome of HRM practices in organizations (Markoulli et al., Citation2017), employers worldwide are increasingly prioritizing HRM practices to attain higher levels of engagement (Garg et al., Citation2022; Shuck et al., Citation2014).

Social exchange theory (SET) provides theoretical justification for this study by shedding light on how workers develop mutually beneficial relationships with their employers through the exchange of voluntary efforts and engagement for perceived benefits from HRM practices and the positive role of the supervisor. When HRM practices are effectively designed and implemented, employees experience a heightened level of satisfaction, leading to increased engagement. Supervisors play a crucial role in implementing and communicating HRM practices (Aybas & Acar, Citation2017), influencing employees’ perceptions of the exchange relationship. Thus, the positive role of the supervisors enhances the perceived benefits of HRM practices (Straub et al., Citation2018), fostering higher levels of engagement (Pires, Citation2021) and reducing turnover intentions (Straub et al., Citation2018). The absence or inadequacy of supervisors’ role may hinder the exchange relationship, reducing engagement. Besides the SET, relying on the JD-R (Job Demand-Resource) theory, this study asserts that employee engagement is a job demand. At the same time, HRM practices and supervisory roles are job resources at the organizational and interpersonal levels. Therefore, this research delves into the crucial effect of the supervisory role as a moderating variable in optimizing the outcomes of HRM practices.

The supervisory role has been shown to positively moderate the impact of management decisions on employee benefits (Korankye et al., Citation2020), emphasizing the significance of supervisors as management representatives in implementing HRM practices within organizations. As crucial contact points, supervisors play a pivotal role in effectively executing HRM practice initiatives and psychologically stimulating subordinates to develop a positive impression of HRM practices (Aybas & Acar, Citation2017; Pandey et al., Citation2018). Moreover, prior studies have shown that the supervisory role significantly influences employee engagement by fostering work engagement (Pires, Citation2021). Conversely, research has shown that even well-intentioned HRM practices may fail to yield desired outcomes if they lack the involvement and support of immediate supervisors, particularly in labor-intensive industries (Pandey et al., Citation2018). Labor-intensive industries face unique HRM challenges related to worker engagement, human rights, ethics, and diversity and inclusion on a global scale (Stahl et al., Citation2020). As a result, the relevance of HRM practices in labor-intensive industries is gaining prominence (Tensay & Singh, Citation2020).

Particularly in the Readymade Garments (RMG) industry, the role of HRM practices in fostering employee engagement becomes critical due to multifaceted labor issues, necessitating the development of appropriate organization-level frameworks and mechanisms for stakeholder engagement (Stahl et al., Citation2020). Human resources in the RMG industry are susceptible to high workloads and job stress that cause low job satisfaction and work engagement. Besides, the RMG industry has struggled to overcome its production deficit compared to other sectors, partly due to the need for more structured HRM practices (Hasnin & Ahsan, Citation2016). Therefore, this study aims to investigate the linkage between HRM practices and employee engagement, specifically in labor-intensive industries, focusing on Bangladesh’s RMG industry.

RMG is Bangladesh’s largest labor-intensive manufacturing industry and is the world’s second-largest apparel exporter (Asian Center for Development, Citation2020). This industry serves as the country’s largest employment hub. With its significant contribution of 83% to the national economy through exports (Hassan, Citation2021), the RMG industry has a crucial role in shaping Bangladesh’s economic landscape. However, despite its economic importance, the industry has been grappling with severe employee disengagement, leading to low productivity levels (Hassan, Citation2021). This disengagement can be attributed to the industry’s poor HRM practices, which could be more conducive to effectively engaging its massive workforce of 4.2 million, often relying on a man-machine integrated approach. As a result, the RMG industry faces a substantial gap compared to its Chinese counterpart, which boasts four times more apparel business due to its success in labor productivity (Uddin et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, the RMG industry primarily consists of family-owned organizations (95%), where HRM practices may lack an adequate level of professional framing to engage and retain talents effectively, ultimately hindering the development of long-term competitive advantages (Madison et al., Citation2018; Pandey et al., Citation2018). Given the labor-intensive nature of the RMG industry and its current state of HRM practices, studying the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement in Bangladesh’s RMG industry becomes imperative to address the pressing issues and identify opportunities for improvement. Since the RMG industry is not adequately structured enough to accommodate formal HRM practices, how to tackle the situation arises. In this perspective, the supervisory role can be critical in alleviating the industry’s lack of structured HRM practices.

The rest of the paper is organized in a few parts. First, a brief review of the literature and the development of the hypothesis is presented. Second, the methods adopted are detailed, leading to the presentation of the study’s results. The study concludes by discussing the findings, their implications, and the potential scope of future research.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Definition of study variables

Employee engagement is defined as employees’ psychological attachment to their occupations, wherein they remain attentive, connected, integrated, and focused on their tasks (Saks & Gruman, Citation2014). This psychological attachment encompasses three dimensions: vigor, dedication, and absorption (Shuck et al., Citation2014). Vigor denotes employees’ willingness and intention to utilize emotion and their high levels of energy and psychological satisfaction in the workplace (Fong & Ho, Citation2015; Gera et al., Citation2019; Stolarski et al., Citation2020). Dedication represents employees’ extreme work involvement, courage, motivation, and commitment to achieving the organization’s specific goals (Gera et al., Citation2019). Absorption refers to employees’ positive experience and satisfaction with their work (Stolarski et al., Citation2020).

In labor-intensive organizations, the scope of HRM practices continues to expand (Tensay & Singh, Citation2020). While various functions fall under HRM practices, as mentioned in , the core functions, according to scholars, include recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation (Markos & Sridevi, Citation2010; Urbini et al., Citation2021). Rubel et al. (Citation2020) added participation and teamwork as the core functions of HRM practices in labor-intensive organizations. However, for the labor-intensive RMG industry, this study focuses on four fundamental HRM functions: recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation, as these directly impact employee benefits and are crucial for the industry’s success (Hassan, Citation2022).

Table 1. Key HRM practices.

Recruitment and selection are vital in labor-intensive industries, as hiring competent employees is essential for productivity and maintaining a skilled workforce, given the industry’s man-machine integrated approach (Dieu et al., Citation2019; Iles et al., Citation2010). Training and development are crucial for keeping employees updated with work and preparing them for current responsibilities and future roles in the organization (Noe & Kodwani, Citation2018; Taylor & Bisson, Citation2020), ultimately enhancing employee performance (Ravi et al., Citation2017).

Performance appraisal involves documenting, reviewing, and evaluating employees’ performance during a specific period, enabling individual improvement (CIPD, Citation2018; Ismail & Gali, Citation2017). A robust performance appraisal system also helps management identify potential employees (Bolarinwa, Citation2017; Kilger & Jonsson, Citation2016). Compensation refers to all forms of pay and rewards provided to employees in exchange for their efforts (Dessler & Varkkey, Citation2018). Compensation significantly affects employee performance, family conflicts financial issues, and living standards (Chrisman et al., Citation2017; Reddy & Medipally, Citation2017; Young et al., Citation2007). The level of COMPENSATION varies based on organizational nature and employees’ localization tendencies (Berber et al., Citation2017; Kang et al., Citation2017).

On the other hand, the supervisory role in this study refers to the pivotal position of immediate supervisors in an organization’s hierarchy, where they play a crucial role in implementing and overseeing HRM practices and policies. Their influence directly impacts employee engagement, as they can stimulate and guide their subordinates positively toward HRM practices and foster a supportive work environment.

2.2. HRM practices & employee engagement

Numerous scholars have explored the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement, finding that HRM practices significantly influence employee engagement (Aktar & Pangil, Citation2017; Jose et al., Citation2022; Sydow et al., Citation2020). Studies by Sydow et al. (Citation2020), Jose et al. (Citation2022), and Aktar and Pangil (Citation2017) reveal a positive link between HRM practices and employee engagement, with core functions such as rewards, performance appraisal, and employee participation enhancing employee engagement, as emphasized by Saks (Citation2006). Employee recruitment and selection, highlighted by Acikgoz (Citation2019) and Dieu et al. (Citation2019), are critical functions impacting employee engagement. Furthermore, training and development programs contribute to improved employee engagement by enhancing employee knowledge and behaviors (Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Bell et al., Citation2017), while effective performance appraisal and feedback are positively associated with workplace engagement (Ugwu & Okojie, Citation2016; Volpone et al., Citation2012). Additionally, compensation is considered a motivating factor for employee engagement in the workplace (Crawford et al., Citation2013), particularly in labor-intensive industries like the RMG sector in Bangladesh (Ugarte & Rubery, Citation2021).

The linkage between HRM practices and employee engagement can also be understood through the lens of SET (Blau, Citation1964), which posits that employees reciprocate perceived benefits received from the organization. HRM practices act as catalysts, accelerating employees’ perception of receiving benefits and ultimately leading to increased engagement. Conversely, when an organization fails to meet employee expectations in HRM practices, employees perceive the reciprocity as failing, resulting in lower levels of engagement (Lee & Jeong, Citation2017). As per the above empirical evidence and theoretical support, the functions of HRM practices need to be more structured in labor-intensive industries, like the RMG industry of Bangladesh, to ensure enhanced employee engagement for its competitive business advantages. Based on the empirical evidence and theoretical support, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: HRM practices positively influence employee engagement

2.3. The moderating effect of supervisory role

Supervisors play a crucial role in successfully implementing HRM practices as they are responsible for putting policies into action (Straub et al., Citation2018). Their active participation in executing HRM practices is indispensable for fostering employee engagement as they are the most influential entity among all possible sources of support at work (Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Imam et al., Citation2022). Supervisors, as crucial contact points, play a pivotal role in effectively executing HRM practice initiatives and psychologically stimulating subordinates to develop a positive impression of HRM practices (Aybas & Acar, Citation2017; Pandey et al., Citation2018). In cases where supervisors fail to effectively communicate the importance of implementing appropriate HRM practices, employee perceptions of HRM practices can be negatively impacted (Pandey et al., Citation2018).

Despite the evidence that HRM practices increase employee engagement, Parker and Griffin (Citation2011) argued that a low level of HRM practices does not always lead to low employee engagement because other organizational resources can mitigate the negative effects of low job-related factors on employee engagement. Additionally, prior research also suggests that negative work behaviors are unlikely to have a negative impact on work outcomes because other organizational resources (e.g. organizational support) can mitigate the relationship (Hur et al., Citation2013; Shantz et al., Citation2014). Supervisory role, a form of organizational support, provides a psychological climate that provides resources to employees for better performance and engagement (Li et al., Citation2021). Thus, it can be asserted that employees with negative perceptions of their HRM practices are no longer expected to exhibit a reduced level of engagement at work if they receive a higher level of supervisor support.

The moderating effect of the supervisory role on the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement can be explained through Social Exchange Theory (SET). According to Jain et al. (Citation2013), in any social interaction, the outputs of both parties are directly proportional to the inputs received. A higher level of supervisory role can compensate for a comparatively low level of job-related resources (Poor HRM practices), resulting in employees’ positive attitudes (employee engagement) as they exert more energy and invest extra effort in the workplace.

Besides, supervisors act as critical agents of social exchange between the organization and employees. Supervisors’ successful implementation of well-designed HRM practices benefits employees, motivating them to reciprocate and strengthen their engagement with the organization. Perceived supervisor support during the implementation of HR policies contributes to positive perceptions, ultimately enhancing work engagement and reducing turnover intentions (Straub et al., Citation2018). Henceforth, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Supervisory role positively moderates the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement

2.4. Conceptual framework

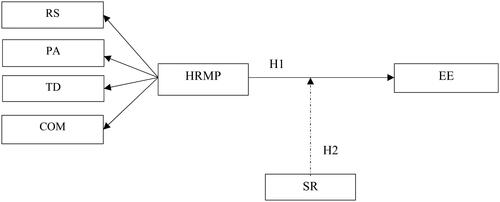

The conceptual framework of this study () envisages that HRM practices influence employee engagement, and the supervisory role in the workplace further enhances such influence. Thus, HRM practices are independent variables, and employee engagement is a dependent variable, whereas supervisory role is regarded as the moderating variable. On the other hand, both employers and employees of an organization act as individual parties to optimize their benefits in the organization (Aryee et al., Citation2002; Ogbonna & Mbah, Citation2022; Urbini et al., Citation2021) as stated by the SET. SET explains that when one party offers a benefit to anyone, the receiving person becomes appreciative of responding (Huang et al., Citation2016), which is also applicable from the organizational perspective as employees gradually amplify their engagement if they see the scope of their return (Joshi & Sodhi, Citation2011).

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and procedure

The working professionals of the RMG industry of Bangladesh served as the population of this study. We chose the RMG industry because of its dominance in the local economy through employment and export earnings (Hassan, Citation2021; RMG Bangladesh, Citation2023). In selecting the respondents, we followed multiple steps. At first, we followed simple random sampling to select RMG firms using two criteria: firms that continued operation for at least two years and were members of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA). The required sample firms was 43 calculated by the equation of n = Z2CV2/e2, where n = sample size; CV = coefficient of variation (5%); e = precision level (1.5%); Z = standard normal variate value at 95% confidence level.

In the next step, respondents were selected from 43 firms based on convenience sampling. The required sample size was 269, which was calculated using the equation n = Z2PQ/d2 where n = sample size; Z = standard normal variate at 90% confidence level, p = dichotomous probability, q = (1−p), and d = precision level (5%).

Finally, we developed a structured closed-ended questionnaire in English and the local language with a 5-point Likert-type scale to collect responses from individual employees. The questionnaire was pre-tested by taking personal interviews. Afterward, questionnaires were distributed in person to 400 participants who had worked in the firm for at least 2.0 years. Respondents freely consented to participate in the survey and were informed that they could withdraw from the survey at any time. Respondents who participated in the pre-testing and pilot-testing phases were also excluded from the final survey. We obtained 280 valid responses (70% response rate) and analyzed the data using the PLS-SEM path model. According to Nitzl et al. (Citation2016), more than 200 responses are sufficient to implement the PLS-SEM analysis. Among the respondents, 49.3% were males, and 50.7% were females, with 59% from the worker level and 41% from the management level. Furthermore, 53.58% of our respondents were below 30 years of age ().

Table 2. Respondent demographics.

3.2. Measures

In this study, we initially adopted well-established and validated scales from prior research to measure the study’s variables (). Then, we followed a meticulous process to improve the relevance and accuracy of the measurement scales. We formed an expert group of a diverse panel of esteemed academics and practitioners. We obtained their critical evaluation focusing on the clarity and face validity of the scales and asked for their expert opinions on any potential additions. Following their recommendations, we made informed decisions about item retention, modification, inclusion, and exclusion.

Table 3. Measures.

Moreover, we conducted a comprehensive pilot study involving a diverse sample representing our target population. Apart from the quantitative feedback, we encouraged their qualitative feedback and paid close attention to their perception. We analyzed the pilot study results, interpreted the items, and ensured face validity. Thus, we refined the measurement scales before the actual data collection.

Our survey questionnaire comprised two sections. The first section captured respondents’ key demographic information, while the second section contained 36 items to assess the study’s variables: HRM practices, employee engagement, and supervisory role. To gauge HRM practices, we focused on four key aspects: recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation. For recruitment and selection, we adapted a 7-item scale from Aoin (Citation2017) with some modifications in sentence construction based on the work of Korankye et al. (Citation2020). The scale’s reliability was found to be high at 0.905. During the pre-test and pilot test, experts’ opinions and respondents’ feedback led to removing one item (‘Firms use advertisements to recruit’) due to low face validity. Regarding training and development, we used a 5-item scale from Otoo and Mishra (Citation2018) with minor sentence construction changes from Korankye et al. (Citation2020), and the scale demonstrated a reliability of 0.929.

For performance appraisal, we adapted a 4-item scale from Otoo and Mishra (Citation2018) and slightly changed sentence construction based on Korankye et al. (Citation2020), resulting in a reliability of 0.939. We added a new item (‘In my firm, employee performance appraisal takes place on time every year’) based on experts’ input. To measure the compensation level in the organization, we adapted a 4-item scale from Otoo and Mishra (Citation2018) with some subtle changes in sentence construction from Korankye et al. (Citation2020), yielding a reliability of 0.827. Experts recommended adding the item: ‘Financial and non-financial benefits are competitively fair in my firm’ to enhance the scale’s face validity.

We adapted a 9-item scale developed by Balducci et al. (Citation2010) to assess employee engagement. Additionally, we used a 6-item scale from Pyhältö et al. (Citation2012) to measure supervisory role. All measures were rated using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’.

3.3. Data analysis

The data collected from the survey were analyzed using two approaches, namely structural equation model (SEM) and importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA). As indicated by Mardia’s multivariate skewness (β =16.693, p < 0.01) and kurtosis (β = 92.511, p < 0.01), our data were not multivariate normal. Therefore, we applied the partial least squares (PLS) approach (Hair et al., Citation2014) using Smart PLS Version 3.9. Additionally, we applied the PROCESS macro in SPSS to investigate the moderating effect. Following Ferraro and Miranda (Citation2013), a floodlight analysis (the Johnson–Neyman methodology) was conducted (Johnson & Fay, Citation1950) to identify the points at which the interaction became significant at the p = 0.05 level. The floodlight analysis is a highly effective technique to exert a noticeable impact within a model of a continuous moderating variable. When theoretically significant values (focal values) do not exist for the moderating variable, the Johnson–Neyman methodology is considered appropriate (Spiller et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, Spiller et al. (Citation2013) proposed that the floodlight analysis is the best test when the moderating variable is continuous, and the measurement is conducted without focal values. Moreover, following Hair et al. (Citation2014), we conduct an IPMA to understand the current priorities of various HRM practices and to determine the priority to be given by human resource managers.

3.4. Bias concern

Methodological and response biases are two key challenges that can affect the credibility of a study’s results (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). To address these issues, we adopted several measures. First, respondents were granted anonymity, encouraging them to provide genuine responses without the fear of being identified. Second, Harman’s single factor examined the common method variance (CMV) problem. This revealed that one factor accounted for 44.531% of the total variance (below 50%), indicating that our findings were free from CMV issues (Uddin et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, we used a correlation matrix to determine whether the linkage between any two variables exceeded 80% (Pavlou et al., Citation2007; Spector & Brannick, Citation2010). Notably, the highest correlation coefficient between any two variables was 0.773 (), indicating that our findings were not biased.

Table 4. Convergent validity with loading, α, CR, AVE.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model

The measurement model’s evaluation primarily concerns the constructs’ reliability and validity. Cronbach Alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) were used to assess the reliability of our constructs, with a cut-off value of 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014). As shown in , both the α and CR scores range from 0.723 to 0.939, indicating the reliability of the variables (Abboh et al., Citation2022; Hair et al., Citation2011; Citation2017). We assessed convergent and discriminant validity using the average variance extracted (AVE) and the HTMT ratio, respectively. The AVE scores, presented in , vary between 0.581 and 0.756, above the threshold limit (>0.50) for adequate convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, as shown in , HTMT’s first-order values are lower than 0.90, indicating that all constructs differ significantly (Gold et al., Citation2001), confirming the discriminant validity.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics, correlation, and discriminant validity.

In addition, we molded HRM practices as reflective-reflective second-order constructs (Bolarinwa, Citation2017). Recruitment & selection, training & development, performance appraisal, and compensation are the dimensions of HRM practices. We opted for the second order because it makes the PLS Path model more compact and intuitive by lowering the total number of relationships (and hence the number of hypotheses to be evaluated) in the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2014). Similar to the first order, the second-order construct meets the criteria of reliability and validity. shows that α and CR scores for the second-order construct are 0.909 and 0.936, respectively, greater than 0.7. The AVE of HRM practices (0.786), greater than 0.5, meets the convergent validity criterion (Ringle et al., Citation2018; Hair et al., Citation2017).

4.2. Structural model evaluation

The structural model was evaluated using fit indices such as R2, F2, Q2, Inner VIF, and several other indicators. presents the results of the structural model evaluation. The R2 value is 0.65, indicating that the overall model predictability is relatively strong (Cohen, Citation1988). Similarly, following Cohen’s (Citation1988) recommendations, HRM practices have a significant effect (F2=0.804), whereas supervisory role has a negligible effect (F2=0.048). Furthermore, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance limit are used to test for multicollinearity (Marsh et al., Citation2004). The maximum VIF score is 1.717, and the tolerance value is 0.582, indicating no multicollinearity issues (Hair et al., Citation2014). The SRMR value is 0.07 (less than 0.08), indicating a good model fit, and Q2 is 0.378 (greater than 0), indicating that the model has moderate predictive relevance (Hair et al., Citation2014).

Table 6. Structural model evaluation.

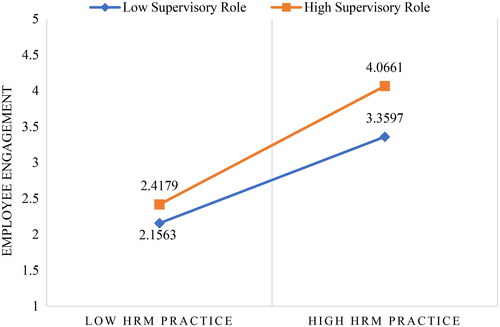

To investigate the hypothesized relationships, we used the Hayes (Citation2013) process (Model 1) with 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The analysis reveals a positive relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement (β = 0.71, p < 0.005, CI: 0.62–0.80), meaning that hypothesis ‘H1’ is supported. On testing the moderating effect using the bootstrapping procedure, we discovered a significant interaction effect between HRM practices and the supervisory role (β = 0.11, p< 0.005, CI: 0.05–0.17), indicating that the supervisory role has a moderating effect in the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement. The floodlight analysis revealed a positive association between HRM practices and employee engagement when the level of supervisory support is −4.17 or higher (). According to the confidence interval range, there is no significant relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement when employee perceptions of HRM practices fell below the −4.17 level.

Table 7. Conditional effects of HRMPs on EE at different levels of SR.

depicts the interaction effects of HRM practices and employee engagement at different levels of supervisory support. Besides the nature of HRM practices, our findings reveal that employees are more involved with their work when a supervisory role is high, and vice versa. Thus, employees are most engaged when HRM practices and supervisory support are effective.

4.2.1. IPMA

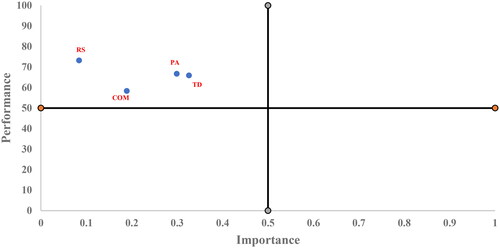

We conducted an IPMA to determine the importance and performance of each variable in influencing employee engagement. Using the average scores of the latent variables that correspond to HRM practices and their indicators, we calculated the index values (HRM practices scoring) by rescaling the scores of all latent constructs, with values ranging from 100 (highest) to 0 (lowest). An IPMA identifies variables with a comparatively high and low priority for improving target outcomes (Hair et al., Citation2014), extending the PLS-SEM results. presents the IPMA results, and illustrates the priority map.

Figure 3. Importance-performance matrix analysis. Note: RS: recruitment and selection; PA: performance appraisal; TD: training and development; and COM: compensation.

Table 8. IPMA results.

Regarding the total effect on outcome variable performance, training and development is the most important for effective employee engagement, followed by performance appraisal, compensation, and recruitment and selection. A one-point increase in training and development performance contributes to a 0.326 increase in employee engagement performance. A considerable gap exists regarding the importance of variables in determining performance effects. Nevertheless, the performance of these variables is comparable.

5. Discussion

Despite the extensive studies on the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement in various contexts, there is a notable gap in research regarding labor-intensive industries (Stahl et al., Citation2020). This study aims to address this gap by exploring the connection between HRM practices and employee engagement, specifically in the context of labor-intensive industries, focusing on the RMG industry in Bangladesh. Apart from its significance to global trade, the Bangladeshi RMG sector was selected for this study due to the industry’s problematic ownership structure and HRM practices. Firms in the RMG industry in Bangladesh are mostly family-owned, and this ownership structure often leads to HRM practices that may fail to engage employees in their work effectively (Madison et al., Citation2018; Pandey et al., Citation2018). Consequently, this study assesses how these HRM practices impact employee engagement.

Given the prevalence of family-owned businesses and the absence of standardized HRM practices, the link between HRM practices and employee engagement is likely to vary across different firms within this sector. Supervisors play a crucial role in boosting employee engagement, particularly when HRM practices are deficient. They can compensate for organizational resource deficits and inspire employees to go the extra mile. Therefore, the study also examines the moderating effect of supervisory role in the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement.

In hypothesis one, it is assumed that HRM practices have a direct positive influence on employee engagement. The study’s result supports the assumption that a high level of HRM practices results in high employee engagement and vice-versa. This finding is also consistent with previous studies (such as Jose et al., Citation2022; Huertas-Valdivia et al., Citation2018; Strobel et al., Citation2017) and the claim that HRM practices promote employee engagement through different interventions to ensure employees feel valued, respected, and involved (Devi, Citation2009). The study’s finding also aligns with the underlying concept of social exchange theory (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Based on the idea of SET, the study reveals that when HRM practices reflect employees’ expectations, a psychological contract is created, and they reciprocate with a higher engagement level. Thus, employees perceive HRM practices as a social exchange where they put discretionary effort in exchange for well-designed HRM practices.

Proper HRM practices, including recruitment and selection, training and development, compensation, and performance management, send strong signals to employees that they are valued, appreciated, and acknowledged within their organizations. Employees who perceive that the organization values them and makes an equal judgment in terms of HRM practices will reply to those good deeds with increased output and engagement (Joshi & Sodhi, Citation2011; Ogbonna & Mbah, Citation2022; Urbini et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, the study delves into which HRM practices are more influential in employee engagement. Therefore, the importance-performance map analysis (IMPA) is conducted. According to the IPMA results, training and development strongly influence employee engagement, followed by performance appraisal, compensation, and recruitment and selection. The influence of training and development in improving employee engagement is obvious as it provides employees with the required knowledge and skills to perform their tasks effectively and paves the way for their career advancement (Ahmed et al., Citation2016). Training programs increase employee engagement as they lead to personal development, leading to career growth (Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Bell et al., Citation2017). Besides, prior studies also support the distinct HRM practices-employee engagement linkages. According to Ugwu and Okojie (Citation2016), employee engagement is linked significantly with pay and compensation. In contrast, recruitment and selection is one of the driving factors of employee engagement, which is required for the labor-intensive industry, as it goes with the man-machine integrated human resources approach.

In hypothesis two, it is presumed that the supervisory role has a positive, significant moderating effect on the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement. The study’s result supports the assumption that HRM practices’ influence on employee engagement is strengthened when supervisors effectively implement HRM practices and provide necessary support. Thus, supportive supervisors act as an amplifier that reinforces the HRM practices and employee engagement linkage. In line with previous research (Hur et al., Citation2013; Shantz et al., Citation2014), this study confirmed that the supervisory role moderates the relationships between all HRM practices and employee engagement. Supervisors can mitigate the relatively negative views of HRM practices. Employees with negative perceptions of their HRM practices are no longer expected to exhibit reduced engagement at work if they perceive supervisors to play positive roles.

The findings can also be explained in the lens of SET. Supervisors act as critical agents of social exchange between the organization and employees. They facilitate the implementation of HRM practices, leading to an enhanced social exchange between employees and the organization. Employees’ perceptions of receiving benefits through HRM practices are amplified when they have supportive supervisors who provide guidance, support, and recognition for their efforts. Even when individuals work with inadequate job-related resources (deficient HRM practices), they typically have access to other organizational resources (supervisory role) that may have a positive effect on employee engagement.

In short, the findings reveal that the HRM practices – employee engagement relationship becomes stronger when supervisors’ support is high and vice-versa ().

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical implications

Considering the social exchange theory as a theoretical underpinning, the findings of this study offer significant theoretical implications regarding the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement in the labor-intensive industry, specifically the RMG industry of Bangladesh. The study supports the tenet of SET, demonstrating that when organizations invest in well-designed HRM practices, employees perceive them as beneficial and exert discretionary effort to reciprocate the exchange. Thus, it can be concluded that, like other sectors, in RMG sectors, the level of sophistication in HRM practices, in turn, leads to heightened employee engagement.

Moreover, the study also reveals the crucial role of supervisors in RMG sectors in strengthening the HRM practices – employee engagement linkage. These findings shed light on the unique contribution of SET in understanding the dynamic between HRM practices and employee engagement. The social exchange between the organization and employees works best only when the supervisor is supportive. Employees are unwilling to reciprocate the benefits of HRM practices with higher engagement until they find supervisor support, guidance, and recognition.

6.2. Practical implications

Apart from the theoretical significance, this study has provided some implications of HRM practices for practitioners from a practical perspective, which will undoubtedly improve the present scenario of HRM practices and thus contribute to employee engagement. Firstly, organizations should develop sophisticated HRM practices that align with employee needs and expectations. This fosters greater engagement and ensures a more favorable social exchange between employees and the organization. Secondly, HR practitioners must exercise result-oriented structured HRM practices as employees perceive. Thirdly, they have to carry out the functions of HRM practices on a priority basis as all the functions do not have the same merits of impact on employee engagement. The findings of this study indicate that training programs play a significant role in improving employee engagement, followed by performance appraisal, compensation, recruitment, and selection. Therefore, placing the right people in the right place, career-focused training programs, conducting on-time performance appraisals, and ensuring fair and equal compensation should be the core functions of the HRM practices that will increase employee engagement. Finally, the employer and HR practitioners of the RMG industry should empower supervisors to play their desired roles effectively. They should invest in supervisor leadership skills, others’ training and support, and establish formal front-line management to optimize the impact of HRM practices on employee engagement.

7. Conclusions

This study delved into the relationship between HRM practices and employee engagement within the labor-intensive RMG industry of Bangladesh. With social exchange theory as its framework, the research demonstrated that HRM practices significantly enhance employee engagement in the workplace, making them a critical driver of employee engagement. The study further revealed the pivotal role of employee supervisors in this dynamic, as their support positively moderates the impact of HRM practices on employee engagement. This underscores the importance of supervisors in effectively implementing HRM practices initiatives and fostering a positive work environment. These findings hold broader implications, offering valuable insights for organizations across industries aiming to optimize their workforce engagement. By prioritizing well-designed HRM practices and empowering supervisors, businesses can cultivate a culture of engagement, boosting overall productivity and success.

7.1. Limitations & future scope of the study

Certain limitations of this study point to important directions for future research. First, the conceptual framework of this study includes only four core HRM functions, excluding the potential impact of other HRM functions. Second, our findings have limited generalizability as RMG is a labor-intensive manufacturing industry with low formal HRM practices and high family ownership and control. Third, this research does not account for firm heterogeneity. The RMG industry has over 4000 firms, so their HRM practices and operational managers’ liberty may differ. Different degrees of HRM practices formalization may produce different outcomes. Employee engagement and supervisory role may also vary as generations change in the top-tier management. Therefore, future research can use purposive or stratified sampling rather than convenient sampling. Finally, given the diversity of the workforce and the wide range of working conditions in the RMG industry, future studies can employ multi-group analysis to obtain more comprehensive results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Jahangir Alam

Mohammad Jahangir is a PhD Researcher at the Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP). He is a prominent HR practitioner in the private organization on local and international platforms. Currently, he is engaged in the RMG industry in Bangladesh. He is also a researcher in the field of human resource management.

Muhammad Shariat Ullah

Dr. Muhammad Shariat Ullah is a Professor and Chairperson in the Department of Organization Strategy & Leadership at the University of Dhaka. He is also working as a Senior Research Fellow, at the Center for Trade and Investment (CT I) of this University and a reviewer of scholarly journals.

Muhaiminul Islam

Muhaiminul Islam is a lecturer in the Department of Organization Strategy & Leadership at the University of Dhaka. Notable accomplishments distinguish his academic life. As a mark of academic excellence, he was awarded a gold medal. His area of research interest includes technology adoption, contemporary leadership, and HR analytics.

Tania Ahmed Chowdhury

Tania Ahmed Chowdhury is a prominent statistician. She is currently working as an MIS Consultant at the RADDA MCH-FP Center, Dhaka, Bangladesh. He also worked in UNICEF Bangladesh, WHO Bangladesh, and Medecins Sans Frontieres-Bangladesh. Her areas of research are big-data analysis and management information systems for organizational performance.

References

- Abboh, U. A., Majid, A. H., Fareed, M., & Abdussalaam, I. I. (2022). High-performance work practices lecturers’ performance connection: Does working condition matter? Management in Education, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/08920206211051468

- Asian Center for Development. (2020). A survey report on the garment workers of Bangladesh (Asian Center for Development survey report).

- Acikgoz, Y. (2019). Employee recruitment and job search: Towards a multi-level integration. Human Resource Management Review, 29(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.02.009

- Aybas, M., & Acar, A. (2017). The effect of human resource management practices on employees’ work engagement and the mediating and moderating role of positive psychological capital. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(1), 363–372.

- Aktar, A., & Pangil, F. (2017). The relationship between employee engagement, HRM practices and perceived organizational support: Evidence from banking employees. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 7(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v7i3.11353

- Aoin, H. M. (2017). Impact of human resource management on organizational performance within firms in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced Research, 4(3), 1–19.

- Ahmed, S., Ahmad, F. B., & Joarder, M. H. R. (2016). HRM practices-engagement-performance relationships: A conceptual framework for RMG sector in developing economy. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(4), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n4p87

- Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., & Chen, Z. X. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.138

- Barreiro, C. A., & Treglown, L. (2020). What makes an engaged employee? A facet-level approach to trait emotional intelligence as a predictor of employee engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 159, 109892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109892

- Bell, B. S., Tannenbaum, S. I., Ford, J. K., Noe, R. A., & Kraiger, K. (2017). 100 Years of training and development research: What we know and where we should go. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000142

- Berber, N., Morley, M. J., Slavić, A., & Poór, J. (2017). Management compensation systems in Central and Eastern Europe: a comparative analysis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(12), 1661–1689. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1277364

- Bolarinwa, K. K. (2017). Agricultural Extension Personnel (AEP) perception of performance appraisal and its implication on the commitment to the job in Ogun State agricultural development program, Nigeria. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 45(2), 64–72.

- Boselie, P., Harten, J., & Lippényi, Z. (2019). HR investments in an employable workforce: Mutual gains or conflicting outcomes? In Investments in a sustainable workforce in Europe, pp. 145–160.

- Balducci, C., Fraccaroli, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000020

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley and Sons.

- CIPD. (2018). Performance appraisal factsheets [online]. https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/people/performance/appraisal-factsheets.

- Chrisman, J. J., Devaraj, S., & Patel, P. C. (2017). The impact of incentive compensation on labor productivity in family and nonfamily firms. Family Business Review, 30(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486517690052

- Crawford, E. R., Rich, B. L., Buckman, B., & Bergeron, J. (2013). The antecedents and drivers of employee engagement. Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice, 44(6), 57–81.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed, pp. 12–13). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

- Dhamija, P., Gupta, S., & Bag, S. (2019). Measuring of job satisfaction: The use of quality of work life factors. Benchmarking, 26(3), 871–892. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2018-0155

- Dieu, D., Pham, T., & Paille, P. (2019). Green recruitment and selection: An insight into green patterns. International Journal of Manpower, 41(3), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-05-2018-0155

- Dessler, G. (2019). Human resource management (16th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Dessler, G., & Varkkey, B. (2018). Human resource management (15th Edition (Revision)).

- Devi, V. R. (2009). Employee engagement is a two-way street. Human Resource Management International Digest, 17(2), 3–4.

- Fong, T. C., & Ho, R. T. (2015). Dimensionality of the 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale revisited: A Bayesian structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Occupational Health, 57(4), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.15-0057-OA

- Ferraro, P., & Miranda, J. (2013). Heterogeneous treatment effects and mechanisms in information-based environmental policies: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Resource and Energy Economics, 35(3), 356–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2013.04.001

- Flippo, E. B. (1971). Principles of personnel management. New York: Mc-Graw Hill Book Co. https://www.abebooks.com/Principles-Personnel-Management-Edwin-BFlippo/30813382982/bd

- Garg, N., Murphy, W. M., & Singh, P. (2022). Reverse mentoring and job crafting as resources for health: A work engagement mediation model. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 9(1), 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-12-2020-0245

- Gavin, M. (2020). 6 strategies for engaging your employees. Harvard Business Review, 2(18), 1–4.

- Gera, N., Sharma, R., & Saini, P. (2019). Absorption, vigor and dedication: Determinants of employee engagement in B-schools. Indian Journal of Economics and Business, 18(1), 61–70.

- Gold, A., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

- Griffin, R. W. (2013). Management, 11th ed. Texas A & M University, South-Western, Cengage Learning.

- Hassan, M. (2022). Human resource management (HRM) practices in readymade garments sector in Bangladesh. IRE Journals, 5(7), 437–445.

- Hassan, F. (2021). Analysis: Golden jubilee of Bangladesh – the role of RMG industry and looking forward. Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/business/economy/317267/analysis-golden-jubilee-of-bangladesh-role-of.

- Hair, J., Jr, Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Huertas-Valdivia, I., Llorens-Montes, F. J., & Ruiz-Moreno, A. (2018). Achieving engagement among hospitality employees: A serial mediation model. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0538

- Huang, M., Lin, W., & Tsai, C. (2016). Outlier removal in model-based missing value imputation for medical datasets. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2018(1), 1817479–1817479. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1817479

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

- Hasnin, N., & Ahsan, M. (2016). Employee training and operational risks: The case of RMG sector in Bangladesh. World Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 71–81.

- Hur, W.-M., Han, S.-J., Yoo, J.-J., & Moon, T. W. (2013). The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Management Decision, 53(3), 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379

- Hair, F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Smith, D., & Reams, R. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.01.002

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

- Imam, H., Sahi, A., & Farasat, M. (2022). The roles of supervisor support, employee engagement and internal communication in performance: A social exchange perspective. Corporate Communications, 28(3), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-08-2022-0102

- Ismail, H. N., & Gali, N. (2017). Relationships among performance appraisal satisfaction, work–family conflict and job stress. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(3), 356–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.15

- Iles, P., Preece, D., & Chuai, X. (2010). Talent management as a management fashion in HRD: towards a research agenda. Human Resource Development International, 13(2), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678861003703666

- Jose, G., Nimmi, P., & Kuriakose, V. (2022). HRM practices and employee engagement: Role of personal resources-a study among nurses. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 73(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-04-2021-0212

- Jain, A., Ong, S. P., Hautier, G., Chen, W., Richards, W. D., Dacek, S., Cholia, S., Gunter, D., Skinner, D., Ceder, G., & Persson, K. A. (2013). Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials, 1(1) https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4812323

- Joshi, R. J., & Sodhi, J. S. (2011). Drivers of employee engagement in Indian organizations. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(1), 162–182.

- Johnson, P., & Fay, L. (1950). The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika, 15(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288864

- Korankye, B., Musah, S., & Ifeamalume, O. (2020). Determining the moderating role of supervisory support on the relationship between organization career management and employee career satisfaction: Evidence from private insurance companies in Ghana. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 8(12), 2069–2083. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v8i12.em07

- Kwon, K., & Kim, T. (2020). An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100704

- Kilger, M., & Jonsson, R. (2016). Talent production in interaction: Performance appraisal interviews in talent selection camps. Communication & Sport, 5(1), 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479515591789

- Kang, H., Shen, J., Kang, H., & Shen, J. (2017). International training and development policies and practices. In International human resource management in South Korean Multinational Enterprises, pp. 85–112.

- Li, P., Sun, J.-M., Taris, T. W., Xing, L., & Peeters, M. C. (2021). Country differences in the relationship between leadership and employee engagement: A meta-analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(1), 101458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101458

- Lee, S. H., & Jeong, D. Y. (2017). Job insecurity and turnover intention: Organizational commitment as mediator. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(4), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.5865

- Madison, K., Daspit, J. J., Turner, K., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2018). Family firm human resource practices: Investigating the effects of professionalization and bifurcation bias on performance. Journal of Business Research, 84(5), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.06.021

- Mayhew, R. (2017). Six main functions of a human resource department. https://doi.org/10.1080/07343469.2017.1404851, https://smallbusiness.chron.com/six-main-functions-human-resource-department-60693.html.

- Markoulli, M. P., Lee, C., Byington, E., & Felps, W. (2017). Mapping human resource management: Reviewing the field and charting future directions. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 367–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.10.001

- Markos, S., & Sridevi, M. S. (2010). Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(12), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v5n12p89

- Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2007.0002.x

- Marsh, H. W., Wen, Z., & Hau, K. T. (2004). Structural equation models of latent interactions: evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods, 9(3), 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275

- Noe, R. A., & Kodwani, A. D. (2018). ? Employee training and development, 7e. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- Ogbonna, H. O., & Mbah, C. S. (2022). Examining social exchange theory and social change in the works of George Caspar Homans–implications for the state and global inequalities in the world economic order. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 13(1), 90–90. https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2022-0009

- Otoo, F., & Mishra, M. (2018). Measuring the impact of human resource development (HRD) practices on employee performance in small and medium scale enterprises. European Journal of Training and Development, 42(7/8), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-07-2017-0061

- Pires, M. L. (2021). The impact of supervisor support on employee-related outcomes through work engagement. In M. H. Bilgin, H. Danis, E. Demir, & S. Vale (Eds.), Eurasian business perspectives (vol. 16, pp. 3–18). Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics.

- Pandey, A., Schulz, E. R., & Camp, R. R. (2018). The impact of supervisory support for high-performance human resource practices on employee in-role, extra-role and counterproductive behaviors. Journal of Managerial Issues, 30(1), 97–121.

- Pyhältö, K., Vekkaila, J., & Keskinen, J. (2012). Exploring the fit between doctoral students’ and supervisors’ perceptions of resources and challenges vis-à-vis the doctoral journey. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7(7), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.28945/1745

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Parker, S. K., & Griffin, M. A. (2011). Understanding active psychological states: Embedding engagement in a wider nomological net and closer attention to performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.532869

- Pavlou, P., Liang, H. and Xue, Y. (2007). Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 105–136 https://doi.org/10.2307/25148783

- Bangladesh, R. M. G. (2023). Bangladesh’s RMG exports to non-traditional markets up by 23.75% in July. https://rmgbd.net/2022/08/rmg-exports-grow-in-fy22-from-newer-markets/.

- Rubel, M. R. B., Kee, D.M.H and Rimi, N. (2020). High commitment human resource management practices and hotel employees’ work outcomes in Bangladesh. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 40(5), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22089

- Ringle, C. M., Becker, J. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2018). Estimating moterating effects in PLS-SEM andPLSc-SEM: Interaction term gerneration* data treatment. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 2(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.2(2)01

- Ravi, M., Mayya, P., & Shetty, N. (2017). Training and development: A tool to enhance employees’ performance. Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 7(9), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.5958/2249-7315.2017.00467.1

- Reddy, I. V., & Medipally, U. (2017). A study on compensation management with reference to bank employees working in Hyderabad. Management, 2(11), 33–38.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., Gonzalez-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A confirmative analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92.

- Stolarski, M., Pruszczak, D., & Waleriańczyk, W. (2020). Vigorous, dedicated, and absorbed: Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Polish version of the sport engagement scale. Current Psychology, 41(2), 911–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00607-5

- Stahl, G. K., Brewster, C. J., Collings, D. G., & Hajro, A. (2020). Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100708

- Sydow, J., Wirth, C., & Helfen, M. (2020). Strategy emergence in service delivery networks: Network-oriented human resource management practices at German airports. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(4), 566–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12298

- Sun, L., & Bunchapattanasakda, C. (2019). Employee engagement: A literature review. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 9(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v9i1.14167

- Straub, C., Vinkenburg, C. J., van Kleef, M., & Hofmans, J. (2018). Effective HR implementation: The impact of supervisor support for policy use on employee perceptions and attitudes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(22), 3115–3135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1457555

- Strobel, M., Tumasjan, A., Spörrle, M., & Welpe, I. M. (2017). Fostering employees’ proactive strategic engagement: Individual and contextual antecedents. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12134

- Shantz, A., Alfes, K., & Latham, G. P. (2014). The buffering effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between work engagement and behavioral outcomes. Human Resource Management, 55(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21653

- Saks, A., & Gruman, A. (2014). What do we really know about employee engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 155–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21187

- Shuck, B., Twyford, D., Reio, T. G., Jr., & Shuck, A. (2014). Human resource development practices and employee engagement: Examining the connection with employee turnover intentions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 239–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21190

- Spiller, S., Fitzsimons, G., Lynch, J., & Mcclelland, G. (2013). Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: Simple effects tests in moderated regression. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(2), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.12.0420

- Spector, P. E., & Brannick, M. T. (2010). Common method issues: An introduction to the feature topic in organizational research methods. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 403–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110366303

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690169

- Tensay, A., & Singh, M. (2020). The nexus between HRM, employee engagement and organizational performance of federal public service organizations in Ethiopia. Heliyon, 6(6), e04094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04094

- Taylor, M. A., & Bisson, J. B. (2020). Changes in cognitive function: Practical and theoretical considerations for training the aging workforce. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.02.001

- Ugarte, S. M., & Rubery, J. (2021). Gender pay equity: Exploring the impact of formal, consistent and transparent human resource management practices and information. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12296

- Urbini, F., Chirumbolo, A., Giorgi, G., Caracuzzo, E., & Callea, A. (2021). HRM practices and work engagement relationship: Differences concerning individual adaptability. Sustainability, 13(19), 10666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910666

- Uddin, M. A., Mahmood, M., & Fan, L. (2019). Why individual employee engagement matters for team performance? Mediating effects of employee commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. Team Performance Management, 25(1/2), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-12-2017-0078

- Ugwu, C. C., & Okojie, J. O. (2016). Human resource management (HRM) practices and work engagement in Nigeria: The mediating role of psychological capital (PSYCAP). International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Review, 6(4), 71–87.

- Volpone, S. D., Avery, D. R., & McKay, P. F. (2012). Linkages between racioethnicity, appraisal reactions, and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(1), 252–270.

- Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131.

- Young, T., Hazarika, D., Poria, S., & Cambria, E. (2018). Recent trends in deep learning-based natural language processing. IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine, 13(3), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCI.2018.2840738

- Young, L. M., Baltes, B. B., & Pratt, A. K. (2007). Using selection, optimization, and compensation to reduce job/family stressors: Effective when it matters. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(4), 511–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-007-9039-8