Abstract

This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the scholarly work and discussion on greenwashing in sustainability reporting (GiSR) and tease out dominant themes that emerge from the literature, and the different emphasis of research between G7 and non-G7 nations. Based on a total of 87 articles from the Web of Science (WoS) database, this study adopts the bibliometrics and content analysis approach, which uses both numerical and visualization techniques to examine the extant literature from 2003 – 2022. The outcomes of the scientific bibliographic coupling identified three dominant themes: (i) Greenwashing (exaggeration of green effort); (ii) ESG disclosures and performance gap and (iii); Communicative legitimation strategies and reporting of negative aspects. Results highlighted overlaps and differences between G7 and non-G7 countries, and the need for further research in non-G7 countries on the institutional, cultural, and socioeconomic variances on greenwashing, firm-level variations in behavior, leadership and strategy on greenwashing, the use of technology in detecting greenwashing, as well as the role of regulatory and governance in corporate reporting to mitigate greenwashing. This study hopes to attract the attention of researchers, policymakers, and businesses to counteract greenwashing by recognizing its determinants and contribute to the quality and credibility of sustainability reporting.

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving and dynamic business landscape, businesses are expected to deliver economic as well as social and environmental value through the encouragement of innovative and creative approaches in the area of sustainable and responsible business practices, including socially responsible investing and responsible procurement of sustainable products (Camilleri, Citation2016). This denotes a change in the business environment toward one that is more ethical and sustainable, where companies are judged not only on their bottom line but also on how well they contribute to a more sustainable future. In accordance with stakeholders’ expectations, practices traditionally focused on financial reporting and compliance are undergoing a transformation to incorporate sustainability considerations (Setiawan et al., Citation2023). This change requires firms to embrace a principled approach, and avoid indulging in the deceptive practice of greenwashing (Alzghoul et al., Citation2024).

The growing importance of sustainability reporting (SR) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosures (Cho et al., Citation2020; Adams & Abhayawansa, Citation2022; Balogh et al., Citation2022; Diab & Eissa, 2023, Citation2023) arises from an increased awareness of the mutual interdependence of business operations, the well-being of society, and environmental sustainability (Solomon et al., Citation2011; Verheyden et al., Citation2016; Antoncic, Citation2019). In the current corporate reporting stage (2020s-onwards), sustainability reporting has become critical, with investors and stakeholders focusing on a company’s environmental and societal impact. As a result, there is a growing call for standardized reporting frameworks, increased regulatory scrutiny, and stakeholder education to curb information manipulation and foster genuine sustainability efforts. Governments and regulators are also tracking the achievements of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) by introducing new requirements and unification of sustainability reporting and disclosure (GRI & SASB, Citation2021).

While many reporting requirements are being imposed on firms, there is evidence that a few firms also view these requirements as value-added, and not merely compliance (Macias & Farfan-Lievano, Citation2017; Petrescu et al., Citation2020). This is largely because sustainability reporting and ESG disclosures satisfy the information needs of the key stakeholders (de Villiers et al., Citation2014; Kılıç & Kuzey, Citation2018), assist organizations in raising their reputation (Elder et al., Citation2016), by objectively documenting societal goals (Silvestri et al., Citation2017; Veltri & Silvestri, Citation2020). Sustainability reports therefore have become a tool to legitimize the status of socially responsible enterprises. Nevertheless, a recent systematic literature review by Silva et al. (Citation2019) shows stakeholders’ dissatisfaction with sustainability performance measurement and reporting approaches. This is largely due to the fact that the quality and comprehensiveness of sustainability reports vary due to institutional and stakeholder pressures, as well as differences in culture, formal requirements, and expectations across countries. These pressures and expectations have given rise to information manipulation practices in corporate reports. Some organizations might employ ESG disclosure to redirect scrutiny or modify public perceptions while maintaining their fundamental operating methods (Adnan et al., Citation2023). Thus, the quality of sustainability reports may vary a lot. Poor quality reports reduce the reputation and credibility of companies associated with these reports, which increases pressure to indulge in corporate greenwashing (Moses et al., Citation2020). Perhaps because of this, parallel to the developments in the demand for sustainability reporting, the phenomenon of greenwashing has also become increasingly prevalent as an aspect of reporting on sustainability and related issues (e.g. de Freitas Netto et al., Citation2020; Delmas & Burbano, Citation2011). Thus, this study intends to fill the research gap by consolidating the existing literature and highlighting the prevalent scholarly discussion in both the G7 and non-G7 countries.

Greenwashing is the act of making false and deceptive claims about a company’s environmental and social benefits (Becker-Olsen & Potucek, Citation2013), which may undermine the efforts of genuinely environmentally responsible companies. Enterprises engage in greenwashing as a means of enhancing their reputation in terms of ESG performance through adaptive institutional isomorphism (Huang et al., Citation2022). It also may cause potential investors to question the credibility of information presented in sustainability reports (Friske et al., Citation2022; Kim & Lyon, Citation2015; Uyar et al., Citation2020). The factors determining the quality of sustainability reporting are the subject of numerous scientific studies (Khan et al., Citation2021; Pramono Sari et al., Citation2023; Moses et al., Citation2020; Ogundajo et al., Citation2022). A growing number of studies have investigated organisational-level and sectoral-level determinants of corporate sustainability reporting such as board attributes, audit committee meetings, shareholders’ activism, ownership structure and sustainability-linked compensation, and industry type (Khan et al., Citation2021; Dong et al., Citation2023; Ogundajo et al., Citation2022; Zyznarska-Dworczak, Citation2023; Almaqtari et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the level of sustainability performance, sustainability offices, sustainability research, teaching programs, student clubs, and financial statements also have a significant effect on the extent of sustainability reporting (Pramono Sari et al., Citation2023). Therefore, researchers (f.e. Benvenuto et al., Citation2023) highlight the need for future research dedicated to investigating the determinants of ‘greenwashing’ in sustainability reporting. Moreover, the prevalence and tolerance of greenwashing vary significantly across nations due to diverse institutional, cultural, and historical contexts, as well as enforcement mechanisms for reporting frameworks (Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021; Sangiorgi & Schopohl, Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2020; Delmas & Burbano, Citation2011). These differences have implications for firm valuation and green investing by institutional investors across borders, considering the varying demands of stakeholders across countries (Lashitew, Citation2021; Testa et al., Citation2018).

Our context differentiates between G7 countries and non-G7 countries. G7 consists of 6 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US) and one non-enumerated member (the European Union). G7 is organized around a few shared values – democracy, pluralism, and representative government. Together, this group wields significant economic, political, and cultural influence over the world, and frequently initiates dialog on policies and issues of global import (Morgan, Citation2012). Many of the policies adopted in G7 countries serve as guides to similar policies in other countries, e.g. on environment, democratic processes, workplace safety, providing voice to the marginalized, and women in the workforce (Morgan, Citation2012). Non-G7 countries, as the term suggests, are countries that do not belong in the G7 group. Non-G7 is much more heterogeneous group, consisting of developed as well as developed countries, with different political and governing philosophies, and widely different institutional contexts.

In the context of resolving sustainability reporting issues that have significant externalities beyond a country’s political borders, and resolution of which may require some degree of consensus, it seems important to understand the trajectory of knowledge development in these two different groups. In G7 countries, one that is formed around shared values and a high degree of dialog, and hence the recognition and resolution of relevant sustainability reporting issues may trace a different trajectory and may coalesce around common themes. On the other hand, in non G7 countries, there may be sparse discussion of sustainability reporting among countries due to a high degree of heterogeneity and low level of shared values. This may be reflected in the trajectory of knowledge development, and various themes that emerge from studies from this group. Understanding the differences between these groups is critical to comprehend how to develop a workable global consensus on sustainability reporting that can be trusted around the world. It is the first step to shed light on knowledge that has been developed from G7 that is organized around a common set of values and coordinates as well as influences global policy in a variety of areas including sustainability, and the corresponding efforts by non-G7 group countries. Our study addresses this gap.

More broadly, this research endeavors to undertake a rigorous examination of greenwashing in sustainability reporting, denoted here as GiSR. Through a meticulous approach combining bibliometric and content analyses, this study seeks to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by highlighting the current state of scholarship and discourse surrounding GiSR. This study aims to investigate knowledge development on greenwashing in sustainability reporting in G7 and non-G7 countries, allowing for an exploration of the varying degrees of attention accorded to this phenomenon in different geographical contexts.

Through bibliographic coupling, prominent themes prevalent in the literature were identified, allowing for an in-depth exploration of divergences in research focus. Additionally, this study aptly identifies gaps in the current body of knowledge, thus paving the way for prospective research trajectories in this critical domain. The findings of this study should contribute to future scholarly discussions on meaningful action to address sustainability reporting challenges, enhancement of public policies and reporting regulation, and ultimately contribute to the development of a more sustainable and responsible corporate strategy.

The study contributes to the available literature in the following ways. Via a systematic analysis, we map the trajectory of knowledge development on GiSR between G7 and non-G7 countries. We extract themes emerging from research on GiSR between G7 and non-G7 countries, including any common themes across the two groups. Detecting commonality is critical for developing global standards on sustainability reporting. In case of high commonality, it would be reassuring that the understanding and definition of ‘sustainability’ is shared between the globally influential G7 countries and countries in the non-G7 group. This can further spur the rapid development of common standards for sustainability reporting to minimize greenwashing. Two common themes identified were exaggeration of green efforts, and gap between ESG disclosure and actual performance. These common themes across both groups suggest that a global sustainability reporting standard may be a worthwhile solution. The third theme was evident only in G7 countries – the communicative legitimation strategies and reporting of negative effects. This suggests a high degree of professional expertise dedicated to greenwashing, which can influence the linguistic construction of sustainability narratives to make sustainability efforts meaningless. If these efforts are identified early, additional legal and policy safeguards as well as strengthening the professional training and socialization around ethical and societally responsible conduct could be initiated, before current practices become the standard across the world. For each of these themes, we identify the gaps and suggest future research agendas for mitigating greenwashing and concurrently enhancing sustainability reporting.

The research also has several practical implications. It helps to map out greenwashing in sustainability reporting from different perspectives – as exaggeration of green effort, ESG disclosures and performance gap, as well as communicative legitimation strategies and reporting of negative aspects. Each of them can be an area for future empirical research based on corporate reporting practice. Moreover, the conclusions of this study may be of use to company managers who are expected to report the results ethically, avoiding information manipulation and not using, intentionally or unconsciously, greenwashing as a form of impression management in reporting. The study may also be used by external stakeholders, which may evaluate the disclosed sustainability performance with a greater awareness of the various factors involved in the use of greenwashing in different parts of the world (and the differences between G7 and non-G7 countries. It gives a new perspective on sustainability reporting quality, opening the opportunities to understand, detect, and limit greenwashing, and reducing its prevalence.

Another practical implication of this research arises from the explicit comparison of greenwashing in sustainability reporting in G7 and non-G7 countries, indicating the key differences between these regions. The conclusions based on this highlight the key factors determining the deployment and prevalence of greenwashing – such as cultural and socioeconomic factors, or the perceived need to ensure symbolic legitimation due to institutional pressures. The study may help regulators in preparing legislation and contextually-adapted sustainability reporting procedures to combat greenwashing as well as development of comprehensive education mechanisms and vehicles to create agency in solving salient social and environmental concerns.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the methodology, mainly the data extraction protocols, and discusses the software integrated for the data analysis. Section 3 discusses the bibliometric findings and a critical analysis of the themes based on bibliographic and content analysis. Section 4 identifies the gaps and meticulously articulates future research. Section 5 concludes.

2. Methodology

This study adopts the bibliometric analysis, which uses both numerical and visualization techniques to examine the extant literature (Baker et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Sundarasen et al., Citation2023) and subsequently contribute to the advancement of scholarly work (Martínez et al., Citation2015; Pizzi et al., Citation2020). Bibliometric analysis has multifaceted benefits (Kumar et al., Citation2023; Alatawi et al., Citation2023). demonstrating its role in objectively uncovering knowledge clusters, nomological networks, and patterns (Hasan et al., Citation2022). This approach facilitates a comprehensive understanding of research themes, collaborative relationships and patterns, and publication trends, offering insights into field evolution and knowledge gaps.

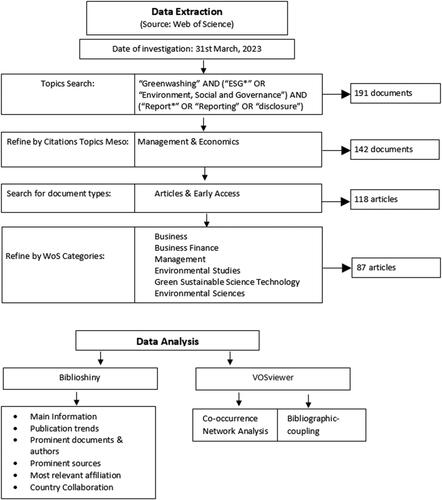

2.1. Data extraction

The Web of Science (WoS) database is used in this study as it offers high-quality peer-reviewed articles. As a first step to data extraction, a systematic search was performed, including the title, abstract, and keyword list, utilizing the specified terms ‘Greenwashing’ AND (‘ESG*’ OR ‘Environment, Social and Governance’) AND (‘Report*’ OR ‘Reporting’ OR ‘disclosure’). This initial process yielded a total of 191 scholarly articles. To ensure a refined dataset, we applied inclusion and exclusion criteria within the Web of Science database search. Firstly, using the ‘citation topics Meso - Management & Economics’, we identified 142 relevant articles. By integrating these precise terms into the search methodology, the study ensures the inclusion of relevant scholarly articles on greenwashing within the domains of economic and management. Subsequently, we limited the document type to include only Articles & Early Access, resulting in 118 articles. Further criteria were then applied, to focus on English-language articles within the domains of Business, Business Finance, Management, Environmental Studies, Green Sustainable Science Technology, and Environmental Sciences, resulting in a final selection of 87 articles published between 2003 and 2022. Each article was carefully assessed to ascertain its relevance to the study’s objectives. As a concluding step, considering the study’s intention to delineate trends and content on ‘Greenwashing and Sustainability Reporting (GiSR)’ in both G7 and non-G7 regions, a manual review of the final set of 87 articles was conducted. This review identified two distinct sets: twenty-five articles from G7 regions and twenty-two from non-G7 regions, facilitating a refined assessment of global perspectives in the context of greenwashing and sustainability reporting. depict a flowchart on the scientific process of data extraction and analysis criteria for the study on GiSR among G7 and non-G7 countries.

2.2. Data analysis

In line with other bibliometric studies, Bibliometrix R-package (Biblioshiny) application (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017) is used to generate textual and graphic representations of publication and citation trends, prominent documents, authors, sources, relevant affiliation and country collaboration by region (G7 and non-G7). Additionally, VOSviewer is utilized for the visualization network – keywords and bibliographic coupling (Baker et al., Citation2020a,Citation2020b). Based on the bibliographic coupling, this study performed a content analysis and identified themes and future research within the realms of greenwashing and GiSR. To conclude the content analysis, a detailed analysis and summary of articles published on GiSR between 2021 and 2022 in Web of Science is undertaken. The reason being, that most of these articles were not captured under the bibliographic coupling output due to their recency in publication. Based on the bibliographic coupling, content analysis, and the 2021-2022 summary (), potential future research is proposed.

3. Findings and discussion

3.1. Main information

compares academic publication data on greenwashing for G7 and non-G7 nations from 2003 to 2022 and 2005 to 2022, respectively. G7 nations initiated greenwashing-related research earlier, possibly due to regulatory concerns. The number of articles published by G7 (25 articles and early access) and non-G7 (22 articles and early access) did not differ significantly. However, non-G7 nations demonstrated a higher average yearly growth rate of 10.41% compared to G7’s 4.14%, indicating remarkable progress in greenwashing-related research. G7 countries had a higher average citation per document (52.76) than non-G7 nations (15.73), likely due to their early initiation of research, greater interest, funding support, and established academic networks. G7 nations had 64 authors, while non-G7 nations had 47 authors, with a small percentage of single authors in both groups. The degree of international collaboration differed significantly, with G7 nations having 8% international co-authorship, while non-G7 nations showed a higher rate of 31.82%. International collaboration is essential for sharing ideas, information, and resources to advance scientific progress and address global challenges. In summary, G7 nations started greenwashing research earlier, but non-G7 nations demonstrated remarkable growth in publication rates. Moving forward, global collaboration is crucial for knowledge exchange, addressing global issues, and promoting scientific advancement.

Table 1. Main information summary relating to the research on GiSR in G7 and non-G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

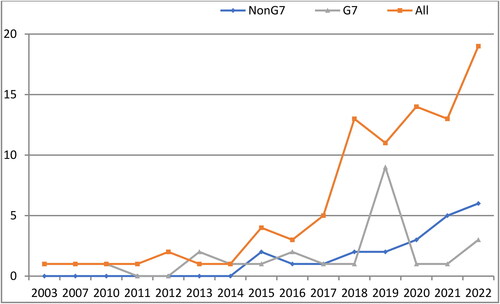

3.2. Publication trend (G7 and non-G7 countries)

3.2.1. Most relevant documents and authors

illustrates an overall uptrend in greenwashing publications in the past decade, but the growth dynamics within specific regions (G7 and non-G7) are not as significant. However, there is a consistent increase in research interest in greenwashing in both regions. The majority of G7 country publications come from authors in the USA (56%), while countries like Canada, England, and Germany each contribute around 8%. In non-G7 countries, China accounts for the majority (55%) of publications, followed by Australia (23%). The uneven growth dynamics among G7 and non-G7 studies suggest a regional bias in greenwashing research. This bias may lead to an imbalanced understanding of the global greenwashing landscape, as regional factors like regulations, corporate practices, and contextual influences differ. The discrepancy in research and citations between G7 and non-G7 countries may result in limited diversity of perspectives and insights in the field, potentially hindering effective identification and mitigation of greenwashing practices in non-G7 countries. This imbalance in knowledge and awareness can also have negative consequences, allowing greenwashing practices to go unnoticed and impacting the environment, society, and stakeholders. Future research should focus on examining greenwashing prevalence and impact in different regional contexts, evaluating the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks, and exploring socio-cultural, economic, and political factors influencing corporate reporting on environmental claims. Diversification and collaboration in research efforts will contribute to more comprehensive strategies in combating greenwashing in corporate reporting and beyond.

Figure 2. Overview of the number of articles included in the Web of Science database relating to the research of greenwashing in sustainability reporting.

Source: Web of Science on 2023.03.30.

presents notable articles on GiSR from both G7 and non-G7 countries. G7 articles are published in reputable journals like Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research, and Organization Science, showcasing their significance in the field. Wang et al. (Citation2018), Siano et al. (Citation2017), Mahoney et al,. (2013), Kim and Lyon (Citation2015), and Hahn and Lülfs (Citation2014) are notable contributors to the GiSR discussion, addressing topics such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting, regulatory frameworks, deceptive manipulation, and legitimation strategies. Non-G7 countries have also made significant contributions through articles by scholars like Du (Citation2015), Khalil and O’Sullivan, (Citation2017), Huang and Chen (Citation2015), and Sial et al. (Citation2018). These articles, published in reputable journals including the Journal of Business Ethics and Asia Pacific Journal of Management, provide valuable insights into areas such as internet social and environmental reporting (ISER), deceptive claims, disclosure efficacy in mitigating environmental pollution, and authentic CSR. Future research should build upon the insights provided by these influential articles and further examine global greenwashing practices. To attain a comprehensive understanding on a global level, it is imperative to focus on sustainability reporting and greenwashing in non-G7 nations. Rigorous research can uncover patterns, trends, and best practices, enabling the development of effective strategies to combat greenwashing and promote responsible corporate reporting practices. Collaboration among researchers from different nations will facilitate cross-cultural comparisons and enrich the collective knowledge on this critical matter.

Table 2. The ranking of the most cited documents and researchers in the Web of Science database relating to greenwashing in sustainability reporting.

3.2.2. Prominent sources (journals)

presents leading journals in the field of GiSR, providing information on their total publications, rankings, and publishers. The top journals for G7 nations include Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Journal of Business Ethics, Organization Science, and Journal of Business Research. These journals cover a wide range of subjects including accounting practices, corporate behavior, ethical issues, business decision-making, and financial reporting. For non-G7 nations, prominent journals include the Journal of Business Ethics, the Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, and Business Strategy and The Environment. The Journal of Business Ethics emphasizes business ethics, whereas the Asia Pacific Journal of Management examines regional organizational achievement, including sustainability reporting. Business Strategy and the Environment examines sustainable business practices and their relationships. The above journals cover management, accounting, communication, and energy economics. The presence of numerous articles on GiSR in these top academic journals highlights the importance and criticality of this research domain. These journals contribute to the dissemination of knowledge and understanding of greenwashing practices, ethical issues, and sustainability reporting. It has implications for various stakeholders, including corporations, policymakers, and environmentalists.

Table 3. The ranking of the most prominent sources in the Web of Science database relating to GiSR for G7 and non-G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

3.2.3. Most relevant affiliation

presents a comparison of affiliations for research publications on greenwashing and sustainability reporting in G7 and non-G7 nations. The data shows that academic institutions from both G7 and non-G7 countries contribute to this research. In the G7 nations, institutions such as Georgia State University, Eastern Michigan University, and George Washington University from the United States lead the way in terms of publications on greenwashing. Among non-G7 countries, Xiamen University and Shanghai University from China, along with Notredame University, are the leading contributors. The increasing interest in sustainability reporting is fostering collaboration and information exchange among scholars, potentially attracting more researchers to the field, and driving the development of innovative techniques for measuring greenwashing and promoting sustainable practices.

Table 4. Top affiliations in the Web of Science database relating to GiSR for G7 and non-G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

3.2.4. Citation trend by country (G7 and non-G7 countries)

provides a comparison of total citations and average article citations for research on GiSR in G7 and non-G7 countries. Citations are an important measure of research prominence and impact, reflecting the extent to which other researchers refer to and build upon previous work. The G7 countries generally have higher total citations, which can be attributed to a higher number of publications and a well-established research ecosystem in these countries. The mature regulatory landscape and increased scrutiny of environmental and social performance in G7 countries have likely contributed to more research and awareness of greenwashing practices. However, there is a need for more rigorous research on greenwashing in non-G7 countries to understand its various aspects. Without such research, companies in non-G7 countries may engage in greenwashing practices without proper scrutiny, leading to negative impacts on the environment, society, and stakeholders. Future research should focus on filling the knowledge gaps in greenwashing in non-G7 countries, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon globally.

Table 5. Citation trends by country relating to articles on GiSR for G7 and non-G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

3.2.5. Country collaboration

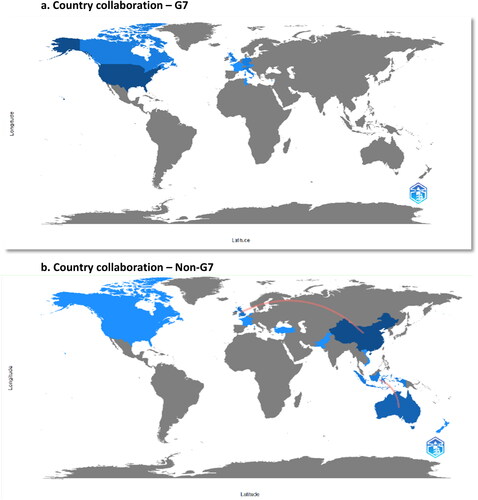

, and show research collaboration patterns on greenwashing and sustainability reporting in G7 and non-G7 nations. The G7 nations, which include the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, show a high level of cooperation and synergy among themselves. However, the cooperation does not extend to countries outside the G7 group, as its members seem to prefer to prioritize their internal dynamics and shared interests over those of other countries. On the other hand, China is the main non-G7 nation that has several collaborations with Australia, Canada, the UK, the US, and Vietnam, whereas Australia collaborates with Indonesia and Vietnam. Collaboration is thus lacking among other non-G7 states, the US, and European nations. Research collaboration is pivotal as it helps set global norms and laws, exchange knowledge and innovation, and share resources and skills. Collaboration may increase publications, citations, funding possibilities, and research impact by reaching a wider audience and being relevant in different settings. Thus, it is imperative that efforts are taken to further enhance collaboration between the G7 and non-G7 nations.

Table 6a. Country collaboration – Non-G7 nations.

Table 6b. Country collaboration – G7 nation.

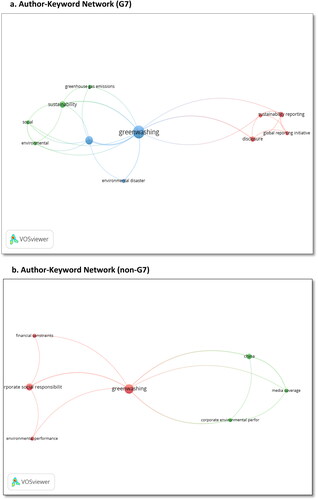

3.2.7. Co-occurrence analysis

presents the author-keywords from the author-keyword network depicted in and . The keyword network reveals that G7 countries have a broader coverage of greenwashing research, with three main clusters: greenwashing (blue cluster), sustainability related to the environment and greenhouse gas emissions (green cluster), and sustainability reporting (red cluster). In contrast, the non-G7 countries exhibit two main clusters: greenwashing and corporate social responsibility (Red cluster), and China’s involvement in corporate environmental performance (Green cluster). The keyword network emphasizes the significance of greenwashing as a research topic, particularly within the G7 countries, while also recognizing China’s contribution to corporate environmental performance research. Further study and collaboration between G7 and non-G7 nations in the areas of sustainability reporting and greenwashing can facilitate knowledge-sharing, capacity-building, and the development of specialized solutions to prevent greenwashing globally. Comparative research can provide insights into the cultural, economic, and legal factors influencing greenwashing and sustainability reporting, leading to more effective strategies in addressing this issue internationally.

Figure 4. (a) Author-Keyword Network (G7). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Web of Science and Biblioshiny on 2023.03.30. (b) Author-Keyword Network (non-G7). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Web of Science and Biblioshiny on 2023.03.30.

Table 7. Author Keywords relating to GiSR for G7 and non-G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

3.3 Content analysis

3.3.1 Major clusters or themes

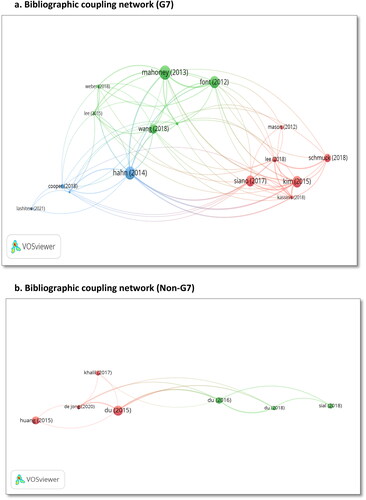

Bibliographic coupling using VOSviewer was performed to discover the associations among citing publications. This analysis forms clusters based on the convergence of citing publications. Coupling analysis compares two papers’ reference counts and concludes their shared subject matter from the referenced works of others. Clustering supports a thematic assessment of the co-citation network (Xu et al., Citation2018). It is a subjective method, requiring a review by knowledgeable parties to refine and generate meaningful clusters. We adjusted the number of minimal citations to ten, requiring that emerging clusters comprise articles that are cited collectively at a minimum of ten times. The bibliographic coupling output is shown in (G7 publications) and (non-G7 publications).

Figure 5. (a) Bibliographic coupling network (G7). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Web of Science and Biblioshiny on 2023.03.30. (b) Bibliographic coupling network (Non-G7). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Web of Science and Biblioshiny on 2023.03.30.

As shown in the bibliographic coupling network, three clusters were identified - . for the G7 publications and two clusters for the non-G7 publications in . All articles were systematically and thoroughly examined in both clusters, and it was concluded that two of the clusters overlapped for both G7 and non-G7, whilst the third cluster was exclusively for G7 publications. A critical analysis of the articles indicates that both G7 and non-G7 research have similar areas of concentration – ‘Greenwashing (exaggeration of green efforts)’ and ‘ESG disclosure and performance gap’. Nevertheless, based on the bibliographic output, ‘communicative legitimation strategies on negative activities’ does not seem to be a prominent area of research in non-G7 countries. The key eccentricities of each theme (both G7 and non-G7 countries) are summarized in (non-G7) and (G7).

Table 8. Key eccentricities relating to GiSR for G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

Table 9. Key eccentricities relating to GiSR for non-G7 countries between 2003 and 2022.

3.3.2. Theme 1: Greenwashing (exaggeration of green efforts)

Theme 1 highlights the greenwashing practices across various countries. Scholars have shed light on the use of greenwashing as a reporting strategy, that aims to demonstrate social responsibility while potentially engaging in deceptive activities (Mason & Mason, Citation2012; Siano et al., Citation2017; Kassinis & Panayiotou, Citation2018; Kim & Lyon, Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2018; Sial et al., Citation2018; Du et al., Citation2016; Du et al., Citation2018). There is a recurring pattern in the US, Germany, the UK, and China that suggests that businesses are using more complex strategies, that extend beyond conventional exaggerations of environmental efforts. Decision to engage in such greenwashing practices may be influenced by institutional context, stakeholder pressure, the need for societal legitimacy, and individual circumstances (Ruiz-Blanco et al., Citation2022). Although motivations differ in accordance with differences in analytical levels, in general, at the firm level, greenwashing is an action motivated by opportunistic purposes (Huang et al., Citation2022), meaning that companies act to portray greater legitimacy of activities with the ultimate aim of enhancing organizational value (Ali et al., Citation2021).

Based on the bibliographic coupling network output, studies collectively highlight the sophistication and diversity of greenwashing methodologies; from ideological persuasion Mason and Mason (Citation2012), and deceptive manipulation Siano et al. (Citation2017), to the strategic use of imagery (Kassinis & Panayiotou, Citation2018), and diversified deceptive practices (Kim & Lyon, Citation2015). Mason and Mason (Citation2012) examination of American companies exposes the utilization of ideological persuasion in environmental reports to project a socially responsible image. This approach involves the communication of a green corporate culture, blurring the lines between genuine environmental commitments and strategic greenwashing initiatives. Similarly, Kim and Lyon (Citation2015) used the US data to further demonstrates that firms employ both greenwashing and brown washing practices, with the extent of deception contingent on corporate growth, deregulation and profitability, suggesting a strategic manipulation of environmental narratives based on prevailing economic conditions. Meanwhile, Siano et al. (Citation2017) research in Germany introduces a novel classification of greenwashing termed ‘deceptive manipulation’, a form of sustainability communication that serves as a platform for constitutional force, further complicating the landscape of irresponsible corporate conduct. Kassinis and Panayiotou (Citation2018) explores into the UK context, revealing how companies resort to the use of images to establish an illusion of realism, diverting attention from environmentally risky practices. This visual-centric approach, coupled with deepened greenwashing practices, provides companies with a platform for rebuilding their image when faced with exposure of decoupling from authentic environmental responsibility. Moving to the non-G7 countries, Sial et al. (Citation2018) study unveils two types of corporate sustainability - substantive and symbolic. Genuine sustainability positively impacts firm performance, but the presence of earnings management diminishes this impact. Institutional theory holds that there are a variety of factors at multiple levels (firm, business function, individual, etc.) that may have an influence on firms’ symbolic strategy (Marquis et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, Du et al. (Citation2016) highlights how Chinese firms in environmentally unfriendly industries employ greenwashing through corporate philanthropy platforms to mitigate weaknesses in environmental reporting. In fact, Du et al. (Citation2018) extend the discussion by emphasizing the importance of corporate environmental performance as a dimension of sustainability.

These findings can be explained from the lens of signaling theory, whereby firms use such tactics to signal as socially responsible citizens and/or to mitigate corporate responsibility reporting weaknesses, as well as to legitimize and reinforce the organization’s sustainability messages. The legitimacy can be systematically sought to create value, but when sustainability actions cannot be objectively verified, it creates the possibility of deception. To establish legitimacy, companies are gradually transitioning from symbolic to substantive changes in their disclosure behaviors (Manes‐Rossi & Nicolo, Citation2022). However, both sustainability reporting and its audit are still in their infancy and need further scrutiny via fraud-fighting tools (Kurpierz & Smith, Citation2020), which may limit greenwashing practices. Regulatory efforts alone may not effectively promote sustainable outcomes (Lee et al., Citation2018). In summary, greenwashing involves deceptive actions driven by profit, while continuous and honest communication of environmental and social initiatives, accompanied by significant changes in disclosure motivation and behavior, is essential for sustainability reporting. The findings underline the need for awareness and stringent regulatory measures to address the deceptive communication of environmental responsibility, fostering a more genuine commitment to sustainable practices within the corporate landscape globally. Hence, there is a need for additional research in this crucial domain of sustainability reporting. delineates the research gaps and potential research.

Table 10. Potential research on Greenwashing (exaggeration of green efforts).

3.3.3. Theme 2: ESG disclosures and performance gap

Corporate sustainability reports, although voluntary, are expected to provide an objective and comprehensive overview of sustainability practices within companies (Hahn & Lülfs, Citation2014). This expectation arises from the stakeholder theory, which emphasizes the engagement and addressing of stakeholders’ concerns (Freeman et al., Citation2010). Enterprises need to demonstrate the legitimacy of their actions through ESG disclosures, as they influence stakeholders’ perceptions of company activities (Huang et al., Citation2022). However, there is often a disconnect between stakeholders’ information needs and the information provided in non-financial reporting (Hadro et al., Citation2022). Thus, based on the output from the bibliographic coupling network, theme 2 discusses the scholarly work in both the G7 and non-G7 nations on disclosure-performance gap between corporate sustainability claims and actual activity.

Research within G7 nations has explored into various facets of corporate sustainability reporting, encompassing voluntary disclosures (Mahoney et al., Citation2013), the readability of sustainability reports (Wang et al., Citation2018), the provision of accurate sustainability information, and the alignment of these reports with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework (Lee & Maxfield, Citation2015). Firms strategically leverage voluntary sustainability reports to demonstrate commitment to social and environmental responsibilities to stakeholders, as highlighted by Mahoney et al. (Citation2013). According to the findings of the study, U.S. firms that issue standalone CSR Reports demonstrate a higher level of corporate citizenship compared to those that do not, aligning with the signaling theory perspective. This implies that these firms utilize standalone CSR Reports as a signal of their commitment to CSR, with ‘good’ companies willing to bear the associated costs for the sake of signaling their dedication to corporate social responsibility. Font et al. (Citation2012) further stress the pivotal role of corporate disclosure systems, featuring the discrepancies that may arise between established guidelines and actual business operations. Similar to the earlier findings, the authors reveal a detachment between corporate policies and actual operations in the hotel industry as environmental performance is often driven by cost savings, while labor policies prioritize local compliance, and socioeconomic policies are restricted and self-constrained. Thus, larger hotel groups (context of the study) exhibit more extensive disclosure policies with implementation gaps, while smaller groups focus on environmental management and fulfill their commitments. This emphasis on disclosure not only aligns with ethical requirements but also contributes to shaping a corporate landscape where environmental and social engagement is integral to corporate identity and accountability. Wang et al. (Citation2018) research further supports the importance of genuine sustainability initiatives, indicating that they lead to clearer and more legible reports, with a particular emphasis on the need for regulating disclosed narratives. This highlights the increasing importance of proper sustainability information for stakeholders and investors alike, as these studies collectively emphasize the significance of transparent and genuine sustainability practices in shaping investor perceptions and minimizing the gap between disclosed information and actual performance (Cooper & Weber, Citation2021). In a comparable context, a study by Lee, J., & Maxfield, S. (2015) advocates for aligning sustainability reports with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework, emphasizing its positive impact on both corporate social and financial performance. Drawing from institutional and stakeholder–agency perspectives, the study suggests that corporate responsibility activity-reporting (CRA-R) positively influences corporate social performance (CSP) and financial performance (CFP). In fact, companies facing a notable performance-disclosure gap without external assurance encounter higher equity costs and increased scrutiny, raising concerns about potential greenwashing (Weber, Citation2018).

On the flip side, the scholarly discussion on the ‘disclosure-performance gap’ in the non-G7 countries is an equally complex issue, ranging from deceptive practices such as lies and half-truths (de Jong et al., Citation2020), and the proliferation of environmentally friendly initiatives (Du, Citation2015). Khalil and O’Sullivan (Citation2017). These underline the prevalence of symbolic disclosures (Khalil & O’Sullivan, Citation2017), emphasizing a detachment between expressed intentions and actual performance, thus contributing towards the ‘disclosure-performance gap’ while de Jong et al. (Citation2020) draw attention to the damaging impact of lies and half-lies on this gap, further eroding investor trust. Similarly, Du (Citation2015) documented that the propagation of environmentally friendly practices, while superficially positive, can contribute to a distorted perception of corporate responsibility. This discord can have significant repercussions for various stakeholders. Investors may make decisions based on inaccurate or inflated representations, leading to financial risks. Additionally, the erosion of trust resulting from such discrepancies can harm relationships with shareholders and the broader public. The misalignment between expressed intentions and actual actions may also impede progress towards genuine sustainability, hindering the overall advancement of responsible business practices and also potentially exposing companies to reputational damage and legal scrutiny.

These factors collectively contribute to a disclosure-performance gap, resulting in an increased cost of equity (Weber, Citation2018) in non-G7 nations. Thus, an increased focus on environmentally friendly practices should be accompanied by transparency and genuine commitment to sustainability to avoid creating a distorted view of corporate responsibility. In this regard, Chinese policymakers are initiating improvements in environmental information disclosure systems for listed companies, aiming to enhance stakeholder trust in company operations and their effects (Huang & Chen, Citation2015). These efforts align with stakeholder theory and a country-specific stakeholder orientation (Orij, Citation2010; Parmar et al., Citation2010). To address these gaps more comprehensively, global standardization and transparency in ESG reporting can be recommended. Initiatives such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) could propose unified guidelines for businesses to disclose their risks and opportunities. This is crucial due to the increasing responsibility assigned by legal regimes to sustainability activities and reporting, as evidenced both by guidelines and scandals in recent years (Kurpierz & Smith, Citation2020). delineates the research gaps and potential research.

Table 11. Potential research on ESG disclosures and performance gap.

3.3.4. Theme 3: Communicative legitimation strategies and reporting of negative effects

The bibliographic coupling network analysis indicates that research efforts in this specific domain are exclusively undertaken on G7 countries only. Hahn and Lülfs (Citation2014) reveals that firms employ ‘symbolic legitimation strategies’ to alter stakeholders’ perceptions of sustainability reports, but these fall short of meeting the rigorous standards set by GRI guidelines. This approach raises critical questions about the sincerity of corporate commitment, as it suggests a deliberate shaping of image rather than substantial efforts, potentially undermining the credibility of sustainability initiatives. The study advocates the development of a GRI-compliant scheme, especially for reporting negative aspects. In the USA, research by Cooper et al. (Citation2018) highlights the absence of a ‘halo effect’, indicating that a firm’s positive reputation for social responsibility does not shield it from the unfavorable consequences of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This finding suggests that public perceptions of corporate social responsibility may not serve as a protective buffer against the negative impact of news about harmful environmental practices, emphasizing the importance of tangible and comprehensive sustainability practices in mitigating reputational risks. Moving to Europe, Lashtiew, (2021) suggest an institutional shift towards frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards. Regulatory surveillance, exemplified by the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive, is seen as a crucial driver to enhance transparency and reliability in sustainability reporting. In conclusion, these studies collectively emphasize the imperative for more robust reporting standards and a genuine commitment to sustainability practices on a global scale, urging businesses to align their actions with the principles of transparency, accountability, and authentic social and environmental responsibility.

The relative paucity of research in this area, in the non-G7 nations may be a signal that corporate disclosure is not ‘a way to fulfill the organization’s social contract’ (Zyznarska-Dworczak, Citation2018b). In line with legitimacy theory, this could be because the need for legitimacy is driven by cultural, cognitive, organizational, religious, and institutional factors (Milne, Citation2002; Palthe, Citation2014; Zyznarska-Dworczak, Citation2018a). This divergence may impact stakeholder perceptions, hinder effective engagement, and impede the establishment of trust and legitimacy for businesses operating in these regions. The question of when or should GiSR be officially treated as fraud remains open, necessitating standardized arrangements and comprehensive research worldwide. In conclusion, sustainability reports serve as a means of legitimizing companies’ actions and addressing stakeholder information needs. However, the risk of greenwashing exists in both G7 and non-G7 countries due to variations in information expectations. To combat greenwashing, efforts are required to manage information expectations and reduce inter-country differences, necessitating joint standardization agreements and stricter governance. delineates the research gaps and potential research.

Table 12. Potential future research on Communicative legitimation strategies and reporting of negative effects.

3.3.5. Summary of discussion of Web of Science articles published in 2021 and 2022

Since bibliographic coupling outcomes depend on authors’ references, they may not completely capture the more recent developments in the area of greenwashing and corporate reporting, thus unable to fully reflect the field’s present state and discussion. In that context, to have a more holistic and comprehensive understanding of the most recent scholarly discussion, summarizes the articles published in 2021 and 2022 in greenwashing and corporate reporting.

Table 13. Summary of Web of Science articles published in 2021 and 2022.

4. Conclusion

Sustainability reporting and ESG disclosures are critical features of sustainability reporting regimes across many countries due to the increasing awareness of the financial risks and opportunities linked to sustainability reporting, stakeholders’ demand for greater transparency and accountability, the rising recognition of organizations’ role in addressing global challenges and the attempts by government and regulators to unify sustainability reporting and disclosures. This study provides a map of knowledge on greenwashing in sustainability reporting in G7 and non-G7 countries. While our study is a small, exploratory step, understanding the similarities and differences may spur further studies to deepen our understanding of greenwashing in specific countries and its determinants. In practice, it may also help in developing a workable global consensus on sustainability reporting that can be trusted around the world. We find that knowledge on greenwashing in corporate reporting is prevalent across G7 and non-G7 corporations, with businesses from various sectors engaging in practices such as inflating ESG achievements or omitting negative environmental and social impacts from financial reports. While G7 countries currently have an edge in the knowledge base created in that context, published knowledge in non-G7 countries is growing more than two times faster than G7 countries. This bodes well for a global understanding of sustainability, and greenwashing in sustainability reporting. We also mapped the trajectory of knowledge development on GiSR between G7 and non-G7 countries. We extract themes emerging from research on GiSR between G7 and non-G7 countries. Two common themes identified were exaggeration of green efforts, and gap between ESG disclosure and actual performance. These common themes across both groups suggest that a global sustainability reporting standard may be a feasible and worthwhile solution. The third theme was evident only in G7 countries – the communicative legitimation strategies and reporting of negative effects. A professional mindset to legitimize greenwashing and putting a positive spin on negative effects could be viewed as a pernicious trend that could make greenwashing even harder to detect in the future in G7 countries.

This study demonstrates that most research in greenwashing tends to examine if GiSR is being used as a platform to communicate green activities, gaps between disclosures and actual green activities, and symbolic legitimation. In general terms, the results highlight the need for more research in non-G7 countries on the determinants of greenwashing, the extent of greenwashing, and the regulatory aspects of greenwashing. Inter-country, inter-region, and global comparisons are also proposed. Research on institutional and firm-level determinants of greenwashing as well as the use of technological tools to detect and mitigate greenwashing would be especially fruitful.

Businesses may face increased pressure in the future to engage in sustainability activities and adapt their reports to uncertain business conditions, including meeting ESG requirements for external funding. A practical implication of our study is that it is crucial to establish the same level of importance for a ‘true and fair view’ in sustainability reporting as in financial reporting, to effectively reduce greenwashing,. This necessitates the development of new tools and approaches that can counteract greenwashing practices and manipulation of non-financial information. Importantly, these reporting practices need to be implemented within an organizational culture that views and even celebrates sustainability as a core value, equal to economic returns. Government and regulatory bodies can enhance transparency and accountability by imposing stricter penalties for non-compliance with sustainability reporting regulations, thus deterring companies from engaging in greenwashing. Ultimately, the aim is to replace the legitimization of activities through greenwashing with audited non-financial statements that ensure the quality and credibility of communicated data to stakeholders. This research highlights the different perspectives of scholarly work on greenwashing and provides direction for future research, acknowledging the fraudulent nature of greenwashing, its causes, and its sources.

One limitation of our study is the variance in heterogeneity among G7 and non-G7 countries. Non-G7 countries are significantly more heterogeneous in many aspects, since, unlike the G7, they are not organized in a formal group, and are a contrast group to G7 countries. As an exploratory study mapping the field, however, this limitation does not constrain the contributions of the study significantly. Additionally, the process of selecting publications and databases involves making choices based on specific keywords, criteria, or parameters. This selection process may inadvertently introduce a certain level of bias. As a consequence, some studies may be excluded from consideration due to the limitations inherent in the chosen keywords or criteria.

We have several directions for future research embedded above within the discussion of each theme. More broadly, future research could explore within-group differences in non-G7 based on a variety of categorical divides, including political system, economic status, performance and sources (e.g. degree of dependence on international trade), dominance of particular industry groups (e.g. mining, manufacturing, technology, services) organization types (e.g. state-owned, family businesses, MNCs, etc.), social stratification, etc. Each of these would be a multi-layered, nested design study accounting for a variety of contextual factors embedded as concentric factors that influence the development of sustainability conversation and practice in each context. Understanding of these differences is critical to developing ways to achieve a broad consensus on sustainability reporting standards and metrics. In G-7 countries, research could explore the process of developing a consensus on sustainability reporting standards and metrics and enforcement regimes, especially given that G7 countries are likely to have representative voices from a variety of stakeholders in the process.

Authors’ contribution

Conception and design: Sundarasen, S; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Goel, S.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Sundarasen, S; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.

Drafting of the paper: Sundarasen, S; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Goel, S.

Revising it critically for intellectual content: Sundarasen, S; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.

Final approval of the version to be published: Sundarasen, S; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Goel, S

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We thank Marie (Beaux) Simmons, University of North Dakota, and Deepa Nakiran, Monash University for their research assistance.

We thank Prince Sultan University for the financial support.

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available on request from the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sheela Sundarasen

Sheela Sundarasen is currently a faculty at Prince Sultan University, Saudi Arabia. Her area of specialization is Financial Accounting and Auditing. Her current research interests includes governance, ESG reporting and financial literacy.

Beata Zyznarska-Dworczak

Beata Zyznarska-Dworczak (PhD) is a professor at the Department of Accounting and Financial Audit, Poznan University of Economics and Business. She is a certified auditor - a member of Polish Chamber of Statutory Auditors. She is an ordinary member of the Polish Association of Accountants and also a member of the Polish Economic Society. She is a lecturer of subjects such as Financial Reporting, Advanced Financial Accounting and Financial Auditing. She is an author of more than 70 papers relating accounting, corporate reporting and financial audit. Her current academic interests are: non-financial disclosures in corporate reporting, sustainability accounting and sustainability assurance.

Sanjay Goel

Sanjay Goel is a Professor and Burwell Chair in Entrepreneurship at the University of North Dakota. His current research interests are in governance, entrepreneurial thinking, entrepreneurial ecosystem, and family business groups

References

- Adams, C. A., & Abhayawansa, S. (2022). Connecting the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing and calls for ‘harmonisation’of sustainability reporting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 82, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2021.102309

- Adnan, S. M., Alahdal, W. M., Alrazi, B., & Husin, N. M. (2023). The impact of environmental crimes and profitability on environmental disclosure in Malaysian SME sector: The role of leverage. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2274616

- Alatawi, I. A., Ntim, C. G., Zras, A., & Elmagrhi, M. H. (2023). CSR, financial and non-financial performance in the tourism sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 89, 102734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102734

- Ali, I., Lodhia, S., & Narayan, A. K. (2021). Value creation attempts via photographs in sustainability reporting: A legitimacy theory perspective. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(2), 247–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2020-0722

- Almaqtari, F. A., Hashed, A. A., Shamim, M., & Al-Ahdal, W. M. (2021). Impact of corporate governance mechanisms on financial reporting quality: A study of Indian GAAP and Indian Accounting Standards. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 18(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.18(4).2020.01

- Alzghoul, A., Aboalganam, K. M., & Al-Kasasbeh, O. (2024). Nexus among green marketing practice, leadership commitment, environmental consciousness, and environmental performance in Jordanian pharmaceutical sector. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2292308. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2292308

- Ansari, Y., Arwab, M., Subhan, M., Alam, M. S., Hashmi, N. I., Hisam, M. W., & Zameer, M. N. (2022). Modeling socio-economic consequences of COVID-19: An evidence from bibliometric analysis. Frontiers Media S.A., 10, 941187. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.941187

- Antoncic, M. (2019). Why sustainability? Because risk evolves and risk management should too. Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions, 12(3), 206–216.

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

- Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., & Pandey, N. (2020a). A bibliometric analysis of managerial finance: A retrospective. Managerial Finance, 46(11), 1495–1517. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-06-2019-0277

- Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., & Pattnaik, D. (2020b). Fifty years of the financial review: A bibliometric overview. Financial Review, 55(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/fire.12228

- Balogh, I., Srivastava, M., & Tyll, L. (2022). Towards comprehensive corporate sustainability reporting: An empirical study of factors influencing ESG disclosures of large Czech companies. Society and Business Review, 17(4), 541–573. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-07-2021-0114

- Barbu, E. M., Ionescu-Feleagă, L., & Ferrat, Y. (2022). The evolution of environmental reporting in Europe: The role of financial and non-financial regulation. The International Journal of Accounting, 57(02), 2250008. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1094406022500081

- Becker-Olsen, K., & Potucek, S. (2013). Greenwashing. Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1318–1323.

- Benvenuto, M., Aufiero, C., & Viola, C. (2023). A systematic literature review on the determinants of sustainability reporting systems. Heliyon, 9(4), e14893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14893

- Camilleri, M. A. (2016). Reconceiving corporate social responsibility for business and educational outcomes. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1142044. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1142044

- Cho, C. H., Bohr, K., Choi, T. J., Partridge, K., Shah, J. M., & Swierszcz, A. (2020). Advancing sustainability reporting in Canada: 2019 report on progress. Accounting Perspectives, 19(3), 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3838.12232

- Coen, D., Herman, K., & Pegram, T. (2022). Are corporate climate efforts genuine? An empirical analysis of the climate ‘talk–walk’ hypothesis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 3040–3059. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3063

- Cooper, S. A., Raman, K. K., & Yin, J. (2018). Halo effect or fallen angel effect? Firm value consequences of greenhouse gas emissions and reputation for corporate social responsibility. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 37(3), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2018.04.003

- Cooper, L. A., & Weber, J. (2021). Does benefit corporation status matter to investors? An exploratory study of investor perceptions and decisions. Business & Society, 60(4), 979–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319898462

- de Freitas Netto, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., & da Luz Soares, G. R. (2020). Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe, 32(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3

- de Jong, M. D., Huluba, G., & Beldad, A. D. (2020). Different shades of greenwashing: Consumers’ reactions to environmental lies, half-lies, and organizations taking credit for following legal obligations. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 34(1), 38–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651919874105

- de Villiers, C., Rinaldi, L., & Unerman, J. (2014). Integrated reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(7), 1042–1067. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2014-1736

- Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

- Diab, A., & Eissa, A. (2023). ESG performance, auditor choice, and audit opinion: Evidence from an emerging market. Sustainability, 16(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010124

- Dong, S., Xu, L., & McIver, R. P. (2023). Sustainability reporting quality and the financial sector: Evidence from China. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(5), 1190–1214. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-05-2020-0899

- Du, X. (2015). How the market values greenwashing? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 547–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2122-y

- Du, X., Chang, Y., Zeng, Q., Du, Y., & Pei, H. (2016). Corporate environmental responsibility (CER) weakness, media coverage, and corporate philanthropy: Evidence from China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(2), 551–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9449-5

- Du, X., Jian, W., Zeng, Q., & Chang, Y. (2018). Do auditors applaud corporate environmental performance? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 1049–1080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3223-6

- Elder, M., Bengtsson, M., & Akenji, L. (2016). An optimistic analysis of the means of implementation for sustainable development goals: Thinking about goals as means. Sustainability, 8(9), 962–986. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090962

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 403–445.

- Friske, W., Cockrell, S., & King, R. A. (2022). Beliefs to behaviors: How religiosity alters perceptions of CSR initiatives and retail selection. Journal of Macromarketing, 42(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/02761467211030440

- Font, X., Walmsley, A., Cogotti, S., McCombes, L., & Häusler, N. (2012). Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure-performance gap. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1544–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.012

- GRI, SASB. (2021). A practical guide to sustainability reporting using GRI and SASB standards. https://www.globalreporting.org/media/mlkjpn1i/gri-sasb-joint-publication-april-2021.pdf.

- Hadro, D., Fijałkowska, J., Daszyńska-Żygadło, K., Zumente, I., & Mjakuškina, S. (2022). What do stakeholders in the construction industry look for in non-financial disclosure and what do they get? Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(3), 762–785. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-11-2020-1093/FULL/PDF

- Hahn, R., & Lülfs, R. (2014). Legitimizing negative aspects in GRI-oriented sustainability reporting: A qualitative analysis of corporate disclosure strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1801-4

- Hamza, S., & Jarboui, A. (2022). CSR or social impression management? Tone management in CSR reports. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 20(3/4), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-04-2020-0115

- Hasan, E., Zeeshan, H. M., Ahmad, F., Bukhari, S. N. A., Anwar, N., Alanazi, A., Sadiq, A., Junaid, K., Atif, M., Abosalif, K. O. A., Iqbal, A., Hamza, M. A., & Younas, S. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of publications on the omicron variant from 2020 to 2022 in the Scopus database using R and VOSviewer. In Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912407

- Huang, R., & Chen, D. (2015). Does environmental information disclosure benefit waste discharge reduction? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(3), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2173-0

- Huang, R., Xie, X., & Zhou, H. (2022). ‘Isomorphic’behavior of corporate greenwashing. Chinese Journal of Population, Resources and Environment, 20(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjpre.2022.03.004

- Karaman, A. S., Orazalin, N., Uyar, A., & Shahbaz, M. (2021). CSR achievement, reporting, and assurance in the energy sector: Does economic development matter? Energy Policy, 149, 112007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112007

- Kassinis, G., & Panayiotou, A. (2018). Visuality as greenwashing: The case of BP and Deepwater Horizon. Organization & Environment, 31(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026616687014

- Khalil, S., & O’Sullivan, P. (2017). Corporate social responsibility: Internet social and environmental reporting by banks. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(3), 414–446. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-10-2016-0082/FULL/PDF

- Khan, H. Z., Bose, S., Mollik, A. T., & Harun, H. (2021). “Green washing” or “authentic effort”? An empirical investigation of the quality of sustainability reporting by banks. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(2), 338–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2018-3330

- Kılıç, M., & Kuzey, C. (2018). Assessing current company reports according to the IIRC integrated reporting framework. Meditari Accountancy Research, 26(2), 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-04-2017-0138

- Kim, E. H., & Lyon, T. P. (2015). Greenwash vs. Brownwash: Exaggeration and undue modesty in corporate sustainability disclosure. Organization Science, 26(3), 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0949

- Koseoglu, M. A., Uyar, A., Kilic, M., Kuzey, C., & Karaman, A. S. (2021). Exploring the connections among CSR performance, reporting, and external assurance: Evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102819

- Kumar, S., Lim, W. M., Sivarajah, U., & Kaur, J. (2023). Artificial intelligence and blockchain integration in business: trends from a bibliometric-content analysis. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(2), 871–896.

- Kurpierz, J. R., & Smith, K. (2020). The greenwashing triangle: Adapting tools from fraud to improve CSR reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 11(6), 1075–1093. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2018-0272/FULL/PDF

- Lashitew, A. A. (2021). Corporate uptake of the Sustainable Development Goals: Mere greenwashing or an advent of institutional change? Journal of International Business Policy, 4(1), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00092-4

- Lee, H. C. B., Cruz, J. M., & Shankar, R. (2018). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) issues in supply chain competition: should greenwashing be regulated? Decision Sciences, 49(6), 1088–1115. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12307

- Lee, J., & Maxfield, S. (2015). Doing well by reporting good: Reporting corporate responsibility and corporate performance. Business and Society Review, 120(4), 577–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12075

- Macias, H. A., & Farfan-Lievano, A. (2017). Integrated reporting as a strategy for firm growth: Multiple case study in Colombia. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(4), 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-11-2016-0099

- Mahoney, L. S., Thorne, L., Cecil, L., & LaGore, W. (2013). A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signaling or greenwashing? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24(4-5), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2012.09.008

- Manes-Rossi, F., Nicolò, G., Tiron Tudor, A., & Zanellato, G. (2021). Drivers of integrated reporting by state-owned enterprises in Europe: A longitudinal analysis. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(3), 586–616. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-07-2019-0532

- Manes‐Rossi, F., & Nicolo’, G. (2022). Exploring sustainable development goals reporting practices: From symbolic to substantive approaches—Evidence from the energy sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(5), 1799–1815. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2328

- Martínez, M. A., Cobo, M. J., Herrera, M., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2015). Analyzing the scientific evolution of social work using science mapping. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(2), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514522101

- Marquis, C., Toffel, M. W., & Bird, Y. (2015). Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organization Science, Harvard Business School Organizational Behavior Unit Working Paper (pp. 11–115 ) .

- Mason, M., & Mason, R. D. (2012). Communicating a green corporate perspective: Ideological persuasion in the corporate environmental report. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(4), 479–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651912448872

- Matakanye, R. M., van der Poll, H. M., & Muchara, B. (2021). Do companies in different industries respond differently to stakeholders’ pressures when prioritising environmental, social and governance sustainability performance? Sustainability, 13(21), 12022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112022

- Milne, M. J. (2002). Positive accounting theory, political costs and social disclosure analyses: a critical look. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 13(3), 369–395. https://doi.org/10.1006/cpac.2001.0509

- Morgan, M. (2012). Consensus formation in the global economy: The success of the G7 and the failure of the G20. Studies in Political Economy, 90(1), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2012.11674993

- Moses, E., Che-Ahmad, A., & Abdulmalik, S. O. (2020). Board governance mechanisms and sustainability reporting quality: A theoretical framework. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1771075. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1771075

- Ogundajo, G. O., Akintoye, R. I., Abiola, O., Ajibade, A., Olayinka, M. I., & Akintola, A. (2022). Influence of country governance factors and national culture on corporate sustainability practice: An inter-country study. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2130149. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2130149

- Orij, R. (2010). Corporate social disclosures in the context of national cultures and stakeholder theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 23(7), 868–889. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571011080162

- Palthe, J. (2014). Regulative, normative, and cognitive elements of organizations: Implications for managing change. Management and Organizational Studies, 1(2), 59. https://doi.org/10.5430/mos.v1n2p59

- Parmar, B. L., Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Purnell, L., & Colle, S. d (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 403–445. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2010.495581

- Petrescu, A. G., Bîlcan, F. R., Petrescu, M., Holban Oncioiu, I., Türkeș, M. C., & Căpuşneanu, S. (2020). Assessing the benefits of the sustainability reporting practices in the top Romanian companies. Sustainability, 12(8), 3470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083470

- Pizzi, S., Caputo, A., Corvino, A., & Venturelli, A. (2020). Management research and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs): A bibliometric investigation and systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, 124033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124033

- Popescu, I. S., Hitaj, C., & Benetto, E. (2021). Measuring the sustainability of investment funds: A critical review of methods and frameworks in sustainable finance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 314, 128016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128016

- Pramono Sari, M., Faisal, F., & Harto, P. (2023). The determinants of higher education institutions’(HEIs) sustainability reporting. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2286668. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2286668

- Reig-Mullor, J., Garcia-Bernabeu, A., Pla-Santamaria, D., & Vercher-Ferrandiz, M. (2022). M. Evaluating ESG corporate performance using a new neutrosophic AHP-TOPSIS based approach. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 28(5), 1242–1266. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2022.17004

- Ruiz-Blanco, S., Romero, S., & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2022). Green, blue or black, but washing–What company characteristics determine greenwashing? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(3), 4024–4045. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10668-021-01602-X/TABLES/8

- Sangiorgi, I., & Schopohl, L. (2021). Why do institutional investors buy green bonds: Evidence from a survey of European asset managers. International Review of Financial Analysis, 75, 101738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101738

- Setiawan, D., Rahmawati, I. P., & Santoso, A. (2023). A bibliometric analysis of evolving trends in climate change and accounting research. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2267233. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2267233

- Sial, M. S., Chunmei, Z., Khan, T., & Nguyen, V. K. (2018). Corporate social responsibility, firm performance and the moderating effect of earnings management in Chinese firms. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 10(2/3), 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-03-2018-0051/FULL/PDF

- Siano, A., Vollero, A., Conte, F., & Amabile, S. (2017). More than words: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal. Journal of Business Research, 71, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.002

- Silva, S., Nuzum, A. K., & Schaltegger, S. (2019). Stakeholder expectations on sustainability performance measurement and assessment. A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.203

- Silvestri, A., Veltri, S., Venturelli, A., & Petruzzelli, S. (2017). A research template to evaluate the degree of accountability of integrated reporting: A case study. Meditari Accountancy Research, 25(4), 675–704. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-11-2016-0098

- Solomon, J. F., Solomon, A., Norton, S. D., & Joseph, N. L. (2011). Private climate change reporting: An emerging discourse of risk and opportunity? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 24(8), 1119–1148. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571111184788