?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The Tourism sector has become increasingly competitive globally, and destination branding has emerged as one of the strategic tools for establishing a competitive edge. This study attempted to discover the determinants of loyalty in destination branding from the supply side perspective. This study was conducted in the Tanzania mainland using a cross-sectional survey research design and data were collected data from 302 respondents. The results were analyzed using Structural Equation Modelling. The findings unveiled that local residents’ engagement has a positive influence on loyalty towards destination branding when mediated with destination identification. The findings have also shown that when local residents develop strong identification towards the destination, they tend to express commitment to destination branding.

Introduction

Tourism sector has become increasingly competitive globally and destination branding has emerged as one of the strategic tools for establishing a competitive edge (Zenker et al., Citation2017). According to statistics, 65.5% of tourism market share is owned by fewer destinations mostly from Europe and America, and 34.5% is competed by the rest of destinations mostly from developing economies (United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2017). There is scant evidence on what constitutes destination branding from a supply-side perspective as the basis for achieving loyalty in destination branding (Hildreth, Citation2010; Medway et al., Citation2015). The majority of tourist destinations adopt branding approaches used to brand physical goods or products, which do not offer a holistic view about the branding of tourist destinations (Jeuring & Haartsen, Citation2017). Unlike physical goods and products, the tourist destination is made of different products, and services that require an integrated branding approach for forming a unified destination brand (Morrison, Citation2013). An integrated approach suggests that local residents are key to loyalty in destination branding (Zouganeli et al., Citation2012). This means the process should start from within (Merrilees et al., Citation2009). The general perception is that destination branding is an internal branding process that is established under conviction that, branding cannot be effective unless it well communicated first internally before going externally (Merrilees et al., Citation2009).

There is little empirical evidence on loyalty in destination branding while viewing local residents as central to the process i.e. supply-side perspective (Zouganeli et al., Citation2012). Evidence indicates that the focus has been on the demand-side perspective, i.e. destination brand image, with little attention to supply-side perspective, i.e. how destination brand identity is constructed in the lens of local residents’ perspectives (Zenker et al., Citation2017). Local residents consider the relationship which they have with a destination as a social relationship that offers both social and economic benefits (Marcoz et al., Citation2016). The identity theory proposed that, when the destination offers the possibility for local residents to accrue benefits, they start to develop identification with the destination branding (Saraniemi & Komppula, Citation2019). Destination identification from this perspective is an outcome of feelings of local residents that the destination programs reflect their interests and personal goals. It is generally considered that the basis for achieving local residents’ commitment towards the brand is the identification that they develop towards the destination (Strzelecka et al., Citation2017; Wassler et al., Citation2019).

Destination marketing has become a key driver for the national strategy and it is forcing all destinations to compete intensively for the opportunity to win more tourists (Konecnik, Citation2002) and to remain competitive in the international market (Omerzel, Citation2006). Statistically tourism destinations from developed economies own 65.5% of the world tourism market, and the remaining 34.5% is competed by the emerging destinations from developing economies including Tanzania (UNWTO, Citation2015). The national tourism growth plan for global tourism as opposed to domestic tourism is systematically biased in Sub Sahara Africa.

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), tourism accounted for 10.3% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 10.4% of total employment in 2019 (WTTC, Citation2020). In Africa, the sector contributes to 24.3 million African jobs, or 6.7% of total employment while in Tanzania it accounts for 11.7% of GDP (WTTC, Citation2020).

As more developing nations are depending on international tourism (Mora-Rivera & García-Mora, Citation2021) the destination branding is of a critical relevance. Providing insights towards how to build a sustainable tourism destination will play a critical contribution in national as well as welfare improvement of the people. From the practical and managerial point of view, the understanding of how to build a destination branding will enable the return on investment from the activities and programs which are being designed and implemented. In recent years many countries with developing economies have made a significant effort in branding their destination, but most of these efforts tend to ignore the local tourism ecosystem. Tanzania is an interesting case for this study because over recent years, the country has made a significant journey in the efforts to build its destination brand. A recent initiative was by a current president who made into a royal tour film, which has been viewed in various countries as attempt for building destination brand. The country has also recently enjoyed spotlight from the tourism ecosystem as it has attracted good ratings from some of its destinations. This paper examines the determinants of loyalty towards destination branding.

Theoretical review and hypothesis development

Social identity theory (SIT)

Social identity theory has been used extensively in both marketing and organizational studies (Berrozpe et al., Citation2018; Elbedweihy et al., Citation2016; Lam et al., Citation2013). Within the context of organizational studies, the identification construct has been used in developing the understanding of relationship between employees and organizations (Lam et al., Citation2013). In similar vein, the identification has been extended in marketing in examining its influence on consumer behaviour (Elbedweihy et al., Citation2016; Rather & Hollebeek, Citation2019). Organizations are made up of value creating networks (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2000) and similar networks do exist in tourism destination (Stokburger-Sauer, Citation2011; Tsaur et al., Citation2016). Building long-term relationships remains to be an important ingredient in sustaining the tourism sector. Social identity theory has been studied in various contexts, ranging from the work environment (employee branding) (Mael & Ashforth, Citation1992), service/hospitality context (Rather & Camilleri, Citation2019; Rather & Hollebeek, Citation2019), corporate branding (Tuskej & Podnar, Citation2018) and several others. Stokburger-Sauer, Citation2011) extended the application of social identification to tourism destination branding. In spite of these research efforts, and application SI in tourism, destination branding context still remains unexplored (Rather, Citation2020; Rather & Hollebeek, Citation2020).

Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory is a relationship-based theory, and identity theory is a role-based theory. Social exchange theory by Blau (Citation1964) suggested that in exchange behaviors have three key norms exist which are solidarity, role integrity, and mutual exchange. It is a shared problem domain that necessitates collaboration among organizations within the industry (Trist, Citation1983). The theory also suggests that, when a distinct group of individuals face a common problem, the best approach is to collaborate to share resources in addressing the problem (Kaufmann & Stern, Citation1988). It is through collaboration, a common solution can be obtained, and hence mutual benefits are achieved between parties who collaborate in solving the problem (Blau, Citation2017). Through a common approach in addressing the problem, solidarity, unification developed which creates the basis for these two parties to collaborate on other aspects in the future. It is believed that, through a collaborative approach to solving a common problem, the parties create a sense of belonging, and hence elicit behavior such as commitment, attachment, readiness to share resources, etc. among parties in the relationship (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2012).

Destination identification

Identity theory has been very essential in the development of various concepts in sociology, and social psychology (Burke & Stets, Citation2009). The theory was developed by Stryker (Citation1980) who tried to theoretically explain how an individual attaches specific meanings to different forms of identifies which are negotiated and managed in given interactions or situations. The theory is based on ‘what one does’ as opposed to ‘who one is’ in the construction of group identity.

Identity suggested that an individual who accepts a particular role identity is likely to act in a way which focuses on accomplishing the expectations of the role, negotiating and coordinating interaction with other role partners, and importantly manipulating the situation to control the resources given the responsibilities of the role (Stets & Burke, Citation2000, p. 226). The theory proposed that through negotiation, meanings, and role behavior which are different but interrelated can produce self-verification (role identity verification), which is very important in building a strong attachment to the group.

It is generally accepted that identification is behavior expressed by a person who feels happy to be defined with a particular thing which is his/her favorite (Alrawadieh et al., Citation2019; Hultman et al., Citation2015). From this perspective, destination identification is emotional behavior expressed by a local resident who has developed a strong connection with a destination (Choo et al., Citation2011). It is emotional feelings expressed by local residents when they feel that there is congruence between their expectations and what the destination delivers (Campelo et al., Citation2014). In the context of identity theory, destination identification is a role-based behavior expressed by a person who reciprocates to what the destination does to him/her (Kumar & Nayak, Citation2019). When local residents develop solid destination identification, they expected to express a strong commitment to the destination and stay active in different programs aiming at ensuring the growth and development of the destination.

Relationship between destination identity and governance

When local residents are involved by local authorities in making decisions regarding tourism programs, it provides an atmosphere that influences local residents to feel ownership of the programs and strategies (Sebele, Citation2010). Recent evidence shows that, if local residents feel that local authorities do not engage them in deciding the future of the destination, they can share information through the social community (e.g. Online and offline social community) purposely for sabotaging local authorities initiatives or efforts in ensuring destination development.

Destination identification is portrayed in the form of a sense of belonging to a certain group (destination) and being able or willing to remain or to stay physically active (Freire, Citation2009). Empirical evidence indicates that loyalty in destination branding is a product of strong self-identification, which local residents develop with the destination. It is widely accepted that to achieve any form of loyalty there must be a strong connection between two parties who exchange things of value (Zouganeli et al., Citation2012). Local residents are expected to express commitment towards the destination branding as indicators of loyalty when the probability for them to benefit from the program is assured. Based on the above arguments it is hypothesized that;

H1: Ability of Involvement by Local Authorities has a positive influence on destination identification

Relationship between destination identify and brand loyalty

The term destination brand is defined as the sum of perceptions that a person has concerning a certain tourism destination (whether based on experience, hearsay or prejudice), which influences his attitude towards that destination at an emotional level; exists in the eyes of the beholder (Cretu, Citation2011). A destination brand generates sets of expectations or experiences of a destination prior to a visit (Qu et al., Citation2011). The primary role of the destination brand is to help prospective tourists to build expectations, or promise of a memorable travel experience that is matchlessly associated with a certain destination (Blain et al., Citation2005; Ritchie & Crouch, Citation2003). A destination brand plays a significant role in influencing tourists’ choices over which destination to visit (Reisinger & Turner, Citation2003; Chiappa and Bregoli Citation2012). In this study, destination brand is defined as a unified expression of a destination that combines the way stakeholders would prefer the destination to be perceived (the identity of a place) and the way tourists define the destination (an image of a place). There have been different perspectives on destination branding, however, there is a general principal that, destination branding is a collaborative coordinating process. Destination branding can be described as a dynamic and complex process that aims at establishing and communicating the unique identity of a destination through integrating efforts, interests, resources and the public at large (Kaplanidou & Vogt, Citation2003; Kwortnik & Hawkes, Citation2011).

Loyalty in destination branding can be well conceptualized by looking at the phenomena as an internal branding process. Destination branding from a supply-side perspective is viewed as a social, political, and cultural process (Ooi, Citation2004). It is believed that the basis for branding a destination is the supply-side perspective as opposed to a demand-side perspective which has been commonly used in branding physical goods or products (Merrilees et al., Citation2009). Destination branding from this perspective considers the branding process as an internal process that requires the combined efforts of all potential players including local residents (Zouganeli et al., Citation2012). Destination branding cannot achieve its intended objectives if local residents are not fully engaged in designing and implementation of the destination branding programs.

Loyalty in destination branding requires the full engagement of local residents. Local residents’ engagement means involving local residents in decisions making and active involvement in strategic areas for the advancement of the destination (Lee et al., Citation2012; Molinillo et al., Citation2019). These strategic areas include the willingness and readiness of local authorities such as in involving local residents in making decisions regarding destination advancement, and local residents’ propensity to invest in various areas for the destination development (Medina-Muñoz et al., Citation2016). Local residents’ engagement can be explained as circumstances in which local residents including service providers, indigenous, etc. are empowered to engage or participate in various strategic tourism operations and programs in a tourism destination (Vollero et al., Citation2018). In the view of Zouganeli et al. (Citation2012) one aspect of sustainability in destination branding is the involvement of local residents in the branding process.

Lee et al. (Citation2012) pointed out that local residents’ engagement aims at ensuring local residents become the source of sustainable tourism advancement. Local resident engagement is an important dimension in realizing destination growth and development (Diedrich & García-Buades, Citation2009). Local resident engagement does not only ensure sustainable tourism development, rather it is very helpful in ensuring Destination Marketing organizations (DMOs) realizing their goals and objectives (Canavan, Citation2015). Evidence indicates that local residents who are not engaged in destination management may develop brutal behavior towards the destination including sabotaging various destination programs including branding programs (Postma & Schmuecker, Citation2017).

The decision for local residents to invest in a given destination implies that they expect a benefit from different tourism operations in the destination. This idea is supported by the theory of relational exchange that, one part may decide to enter into an agreement with other parts if the agreement offers the possibility of obtaining the value. When local residents perceive that there is significant value when investing in tourism activities within the destination, they will be ready to invest their resources to ensure the destination prosper (Ap, Citation1992). It has been well documented that, local residents’ tendency to invest in tourism development and eventually destination development tends to develop a sense of place (Del Chiappa, Citation2012). Destination branding is not a one man activity, it is a process that demands support in terms of investment from all stakeholders in the destination (Simpson & Bretherton, Citation2009).

In the context of tourism, the term local residents’ or local people or local communities can imply any person (eg. service providers or passers-by) who has the privilege of having direct contact or encounter with tourists at given tourism destinations (Crick, Citation2003). Therefore, local communities or residents’ engagement has proved to be influential factors in sustainable tourism development (Presenza et al., Citation2014), destination development (Diedrich and Buades, 2009), and DMO success (Pechlaner et al., Citation2012).

H2: Local Residents’ Propensity to Invest in Tourism is positively influence destination identification.

From supply-side perspective loyalty in destination branding is perceived as an attempt to view destination branding as a local resident centered process (Schultz & Block, Citation2015). Loyalty in destination branding is the extent to which local residents are committed to branding programs with the intention of ensuring that the destination continues to exist by delivering value to existing stakeholders without compromising the values, interests, and benefits of future stakeholders and the entire communities. To realize this, local residents should develop self-identification with the destination as the antecedent of the loyalty in destination branding from supply-side perspective. Therefore, it hypothesizes that;

H3: Destination Identification has a positive influence loyalty towards destination branding

Research methods

Research design and context

The study adopted a cross-sectional survey research design using data collected from Tanzania mainland. Tanzania tourism sector has generated a value of about 1.4 billion dollars from 2021 compared to 2020 when it was severely affected by COVID pandemic. The tourism sector contribution from GDP felled from 107% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020. In 2021 there was 922,692 tourists, an increase of 48.6% from 620, 867 in 2020. Tanzania is an important destination in Africa and thus relevant for being selected in this study because it earned a title of the leading destination in 2021 and has allocated 25% of its total area of four wildlife national parks and protected areas (Tanzania Investment Report, Citation2022).

Target population and sample size

The study involved a sum of 300 respondents who are owners, supervisors, owner-manager of services organizations operated in the tourism sector in Tanzania. The study population was obtained from the Tourism Confederation of Tanzania (TCT). TCT is the umbrella organization (apex body) which represent various private business sector (Sub-Sector Associations) operated in the travel and tourism industry in Tanzania. Final sample used in the study was 201 which was extracted from the sample frame.

Sample size

Sample size refers to selected cases which deemed necessary to represent the entire targeted population (Neergaard, Citation2007). The sample for the study was obtained from the selected associations of business firms dealing with tourism business or activities. The selection of these associations was done based on their dominance in the tourism sector and number of members as indicated in below. The sample size was determined from the associations instead of individual firms because, it is very easy to obtain key informants who have plenty and relevant information about the phenomenon under the study from these associations rather than dealing with individual firms who are not members of the associations.

Table 1. Different tourisms associations.

The sample size for the study was determined by using Slovin’s Formula as follows:

Where:

N = Total number of the population of the study

n = Sample size

E = Margin of error (0.05)

Therefore;

n = 232 Tourism Business Organizations

This study expanded the sample size to 280 so as to enhance the accuracy of the study findings (Cohen et al., Citation2007). Proportionately, the following sample size was obtained from each association as indicated in the below.

Table 2. Proportional sample size from each association.

Sampling procedure

There are two distinctive approaches which can be used to determine the number of respondents for participating in a study, namely probability sampling and non-probability sampling approach (Baker, Citation2003). In this study non-probability sampling was adopted, whereby the sample was selected through the use of purposive and snowball sampling. Purposive sampling provides a specific and unique sample which yield the most relevant, accurate and plentiful data about the study topic. It allows a researcher to select few sources or key informants which are in rich of information about the issues pertaining to the study. Moreover, in snowball sampling approach the first respondent who fits the respondent profile is selected. Thereafter, the respondent refers others with similar characteristics (Bonita, Citation2008). This approach is useful when a researcher is less knowledgeable on potential participants, or the majority of participants are not ready to participate in the study.

Data collection instruments and procedures

This study used a semi-structured questionnaire that was self-administrated to different supervisors, managers, owners, owner-managers of various business firms operates in different sub-sectors in the tourism industry in Tanzania. Before the data collection exercise, pilot testing was conducted to achieve the content validity of the instruments. Thereafter, necessary improvements were done on the instruments to reduce vagueness, repetition, etc. Also, prior informal and formal meetings were done with respondents to establish rapport and to familiarize themselves with the sector. Thereafter, data were collected through the use of research assistants who were recruited based on their knowledge and experience in the tourism sector in Tanzania. However, frequent feedbacks were obtained from the research assistants to ensure the accuracy of the data collected.

Measures

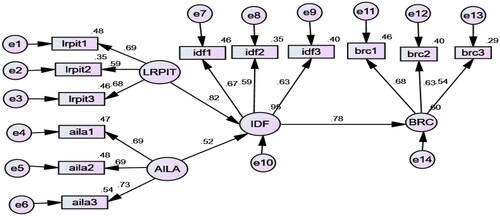

The study variables were measured by adapting measurement scales from previous studies in tourism. All variables were captured by using 5-point Likert scales from 1-strong agree to 5 – strongly disagree. The construct Local Residents’ Engagement (LRE) has two variables i.e. Ability of Involvement by Local Authorities (AILA) and Local Residents’ Propensity to Invest in Tourism (LRPIT). Measurement scales for both variables were adopted from Presenza et al. (Citation2014). On the other hand, Destination Identification (DEI) was measured by measures scales from Zouganeli et al. (Citation2012), Bregoli (Citation2013), and Zenker et al. (Citation2017). Finally, the construct loyalty in Destination Branding (SDB) is defined by one variable Brand Commitment (BC). The measurement scales for the variable was adapted from Sartori et al. (Citation2012); Zhong et al. (Citation2017). The table below provides a detailed overview of how the variables were measured .

Table 3. Operationalization of variables.

Results

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to analyze data. SEM is a multivariate data analysis technique that is more powerful in testing a series of relationships that exist between study constructs through modeling a regression structure for latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2010). It can accommodate unobserved or latent variables in causal models. This technique was suitable for this study because, the hypothetical constructs used in the study were not directly observable and hence the constructs were measured indirectly by employing observed scores or indicators (Kline, Citation2015).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Value of goodness of fit indicators as presented in below and falls within the threshold indicating a perfect fit of the hypothesized model. The value of GFI, AGFI, NFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI should be > 0.9, the value for x2/df should be < 3 and the cutoff point for RMSEA is < 0.1 (Hooper et al., Citation2008). The measurement items were confirmed to be a good measure of the Local Residents’ Engagement (LRE) construct. On the other hand loadings for all items were > 0.3 indicating good convergent validity (Tableachnick & Fidell, 2012). The value of Cronbach Alpha Coefficient was > 0.7 for all variables, implying a good internal reliability and consistency of the constructs of the study (Pallant, Citation2000; Tableachnick & Fidell, 2012). All variables had the value of Composite Reliability > 0.6 and Maximal Reliability(MaxR(H) > 0.7 indicating that the instruments were reliable (Santos & Reynaldo, Citation2013; Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011). Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was > 0.5 for both variables indicating a convergent validity of the data (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988).

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

Discriminant validity was examined by comparing the value of the square root of AVE and correlations between the variable and other variables and by comparing the value of AVE of each specific variable and its respective Maximum Shared Variance (MSV). The rule of thumb is that the square root of AVE should greater than the value of correlations between the variable and other variables. As indicated in the discriminant validity of the data was achieved because, the square root of AVE was greater than the value of correlations between the variable and other variables (Said et al., Citation2011), and the value of each AVE is greater than their respective MSV (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) .

Table 5. Standardized regression weight, cronbach alpha coefficient (α), composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and goodness of it indexes for LRE construct.

Structural model

Local Residents’ Engagement (LRE), Destination Identification (DEI), and the Loyalty are three constructs used for modeling the Destination Branding (LDB). The findings indicate that the goodness of fit index for the structural model falls within the recommended ranges as indicated in , which provided the way for regression analysis to establish the relationship between variables under the study .

Table 6. The goodness of fit index for the structural model.

Regression analysis

The regression analysis indicates that Local Residents’ Propensity to Invest in Tourism (LRPIT) influences positively the Loyalty in Destination Branding (LDB) (β = 0.500; p < 0.05). Further, there is a positive relationship between the Ability of Involvement by Local Authorities (AILA) and Loyalty in Destination Branding (LDB) (β = 0.373; p < 0.05). Destination Identification (DEI) has also been found to be the mediator of the relationship between Local Residents’ Engagement (LRE) and Loyalty in Destination Branding (SDB). These findings suggest that, the Ability of Involvement by Local Authorities (AILA) have a positive influence on Destination Identification (DEI) (β = 0.469; p < 0.05). Local Residents’ Propensity to Invest in Tourism (LRPIT) had also a positive influence on Destination Identification (DEI) (β = 0.728; p < 0.05). The relationship between Destination Identification (DEI) and Loyalty in Destination Branding (LDB) (β = 0.829; p < 0.05) were also found to be positive .

Table 7. Regression analysis output.

Testing the strength of mediator variable

The strength of the mediator variable was tested by SOBEL test and the results were interpreted as suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986). The findings indicate that Destination Identification (DEI) is a partial mediator between Local Residents’ Engagement (LRE) and Loyalty in Destination Branding (LDB) .

Table 8. SOBEL test output.

Discussion of findings

The study focused on understanding the determinants of loyalty in the destination branding with the focus on the supply side in response to the increasing relevance from the economical point of view (Mora-Rivera & García-Mora, Citation2021) and the research gap which has not been well explored (Rather, Citation2020; Rather & Hollebeek, Citation2020). The three hypotheses developed in this study aimed at understanding how the destination identification is influence of local authorities’ involvement and propensity of local residents to invest. Further, the hypothesis also examined the relationship between destination identification and destination branding. All these hypotheses were supported at different degrees.

The ability of involvement by local authorities and local residents’ propensity to invest in tourism were found to influence positively destination identification. It was also found that, destination identification as a mediator variable influences loyalty in destination branding confirming all three proposed hypotheses of the study.

When local authorities have the power to involve local residents in the management of the destination it has a direct effect on the willingness of local residents to be identified or defined themselves with the destination. Local authorities’ willingness and abilities to engage local residents should focus on ensuring that, local residents benefit by being engaged in different tourism programs, and the destination benefits from engaging local residents in its development programs. Each part should be identified with a specific role that plays in the whole process of designing and executing various tourism programs including destination branding. This creates a role-based identity between the parties which is very crucial in building destination identification.

It is believed that, when local residents invest in the sector, they become co-investors with Government and its agencies i.e. DMOs, and hence it is likely that they will be ready to define themselves with the destination. They are ready to defend the interest of the destination by subduing their interests, particularly when there is a likelihood of benefiting from the destination. Local residents as co-investors expect mutual benefits with other parties or investors who operate mutually in the sector. Identification towards the destination by local residents depends on whether there are possibilities of accruing benefits due to their decision to invest in the sector.

On the other side, DMO expects local residents’ supports to various programs such as destination branding which empirical evidence confirms that they require a bottom-up approach as opposed to a top-down approach. Therefore, in any destination program in this case destination branding, local residents are recognized by their role that they play in the development of the destination identity. It is this role as co-investors that prompt local residents’ behavior to identify themselves with the destination and its programs.

It has been articulated in this study that, loyalty of destination branding is an expression of loyalty by local residents. This strong connection is outward behavior expressed by a person who prefers to be defined in connection with the destination and its programs. The findings are consistent with Jeuring and Haartsen (Citation2017) who found that local residents engage actively if they were involved in the process of building the brand. They argue that the specific role that they play in realizing the brand induces the sense of ownership, and hence they feel to have a stake in the brand and its outcomes. Vollero et al. (Citation2018) also discovered that minimal level of local residents’ involvement is the most critical challenge that hampers the destination branding process. The sustainability of destination branding is a role-based process that should be initiated by adopting a bottom-up approach (Zouganeli et al., Citation2012). The bottom-up approach considers destination branding as a process that should start from within and ensures the results of destination branding carry values, norms, culture, etc. of local residents. The results share the opinion from Kalandides et al. (Citation2012) who suggested the investment in destination branding should consider local residents and other stakeholders as central to the process to achieve significant results.

Conclusion and implications

Conclusion

The study has found the important role that the local authorities play in facilitating destination branding. Sustainability of destination branding to a large extent is driven by how the local communities are actively engaged in the destination branding programs. These program involve their active participation in various activities as well as becoming co-investors. For the local residents to become the active players of destination branding, it is not something that happens automatically but it has to be established by developing enabling environment. Proper environment which is cultivated by government will ensure a sense of ownership among the local residents, but also it will lower the cost of building the destination branding over time. As local residents perceive the benefits accrued from the engagements in various programs, the role of government will also decrease and become supervisory. Lack of adequate engagement of local residents is a channel for creating hindrances in the process of building a destination branding (Vollero et al., Citation2018), thus this should be avoided. Any destination branding building program which is owned by local residents will stimulate the both business and welfare of the communities. This bottom up approach for building destination branding (Zouganeli et al., Citation2012) should be adopted for sustaining the destination branding because it provides a proper foundation which consists of the key players in the process (Kalandides et al., Citation2012).

Policy implications

We recommended the Government should involve local residents in the decision regarding the management of the destination. The decisions around destination should focus on ensuring sustainability by conserving the attractions as well as providing stimulating programs for the locals to be fully engaged. Government should also encourage, support, and empower local residents to invest in the tourism sector and its sub-sectors.

It is important to ensure enabling environments in terms of policies, laws, and regulations for local residents to participate in the sector through local investment.

The empirical findings confirm that this decision may boost local resident identification towards the destination and its programs. Furthermore, empowerment programs should focus to ensure local people in the grassroots participate in the conservation and promotion of natural tourist attractions found in the locality.

Practical implications

The study provides a practical guide on how to build a destination branding from the bottom up. From the perspective of this study, a successful destination branding needs to be developed through engaging the local communities.

The study has also provided a proper way to engage the local communities. These local communities can be properly engaged by making them involve in tourism activities and by ensuring that they are benefiting from such engagements. To sustain such engagement the local communities can be co-investors of the tourism related activities.

Local authorities need to play a central role in facilitating the active engagement of local communities in various programs related to destination branding. Combining co-investment, the active role of local authorities and benefits accrued for participation in local tourism, a successful destination branding can be built.

Limitation and future studies

This study employed a quantitative approach that does not provide an opportunity to explore a naturalistic picture of the subject under the study. Future studies can be done to explore the study topic by adopting a qualitative approach or a mixed approach. Future studies can be done by extending the participation of other stakeholders who do not have direct contact with tourists.

The study has found a significant role which can be played by local authorities in influencing destination branding, however the mechanism through which these authorities can use has not well been studied. Future research work can explore for example the various engagement methods and how they can ensure the local communities’ active participation. Co-investment has also been found to influence the local residents’ engagement in destination branding, however the various mechanisms and challenges for such investment is not yet understood.

There is implied relationship between local residents’ loyalty and destination branding (Jeuring & Haartsen, Citation2017) but such a relationship is not clear, thus future studies can explore further. Concepts such as loyalty of a destination, destination branding seems to be interelleted, but a nature of that relationship is not clear. Future studies can explore the programs and process involved in these concepts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alrawadieh, Z., Prayag, G., Alrawadieh, Z., & Alsalameen, M. (2019). Self-identification with a heritage tourism site, visitors’ engagement and destination loyalty: the mediating effects of overall satisfaction. The Service Industries Journal, 39(7–8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1564284

- Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Baker, M. (2003). Business and management research, how to complete your research project successfully. Westburn.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). Moderator mediator variables distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Berrozpe, A., Campo, S., & Yagüe, M. (2018). Am I Ibiza? Measuring brand identification in the tourism context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 11, 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.04.005

- Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2005). Destination branding: Insight and practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505274646

- Blau, P. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. Wiley.

- Blau, P. M. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge.

- Bonita, K. (2008). Marketing Research: A Practical Approach (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Bregoli, I. (2012). Effects of destination managemnet organization (DMO) coordination on destination brand identity: A mixed method study on the city of Edinburg. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512461566

- Bregoli, I. (2013). Effects of DMO coordination on destination brand identity: A mixed-method study on the city of Edinburgh. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512461566

- Burke, J. P., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory. Oxford University Press.

- Campelo, A., Aitken, R., Thyne, M., & Gnoth, J. (2014). Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496474

- Canavan, B. (2015). Marketing a tourism industry in late stage decline: The case of the Isle of man. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2015.1004227

- Casley, D. J., & Kumar, K. (1987). Project monitoring and evaluation in agriculture. CABI Digital Library. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10 .5555/19891865962

- Chiappa, G., & Bregoli, I. (2012). Destination branding development: Linking supply-side and demand-side perspectives. In R. Tsiotsou, & R. Goldsmith (Eds.), Strategic Marketing in Tourism Services (1st ed., pp. 51–61). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Choo, H., Park, S. Y., & Petrick, J. F. (2011). The influence of the resident’s identification with a tourism destination brand on their behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(2), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2011.536079

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Cretu, I. (2011). Destination Image and Destination Branding in Transition Countries: The Romanian Tourism Branding Campaign ‘Explore the Carpathian Garden The University of New York. A Thesis for the Award of Masters Degree

- Crick, A. P. (2003). Internal marketing of attitudes in Caribbean tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15(3), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110310470202

- Del Chiappa, G. (2012). Community integration: A case study of Costa Smeralda, Italy. In Fayos-Sola, E., Silva, J., & Jafari, J. (Eds.), Knowledge management in tourism: Policy and governance applications bridging tourism theory and practice (pp. 243–226). Bingley.

- Diedrich, A., & García-Buades, E. (2009). Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management, 30(4), 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.009

- Elbedweihy, A., Jayawardhena, C., Elsharnouby, M., & Elsharnouby, T. (2016). Customer relationship building: The role of brand attractiveness and consumer–brand identification. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2901–2910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.059

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Freire, J. R. (2009). Local people a critical dimension for place brands. Journal of Brand Management, 16(7), 420–438. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550097

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson University Press.

- Hildreth, J. (2010). Place branding: A view at arm’s length. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.7

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Hultman, M., Skarmeas, D., Oghazi, P., & Beheshti, H. M. (2015). Achieving tourist loyalty through destination personality, satisfaction, and identification. Journal of Business Research, 68(11), 2227–2231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.002

- Jeuring, J. H. G., & Haartsen, T. (2017). Destination branding by residents: The role of perceived responsibility in positive and negative word-of-mouth. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(2), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2016.1214171

- Kalandides, A., Kavaratzis, M., Boisen, M., & Kavaratzis, M. (2012). From “necessary evil” to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331211209013

- Kaplanidou, K., & Vogt, C. (2003). Destination branding: Concept and measurement. Michigan State University, Department of Park, Recreation, and Tourism Resources.

- Kaufmann, P. J., & Stern, L. W. (1988). Relational exchange norms, perceptions of unfairness and retaired hostility in commercial litigation. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 32(3), 534–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002788032003007

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Konecnik, M. (2002). The image as a possible source of competitive advantage of the destination—The case of Slovenia. Tourism Review, 57(1/2), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb058373

- Kumar, J., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Exploring destination psychological ownership among tourists: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 39(2019), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.01.006

- Kwortnik, R., & Hawkes, E. (2011). Positioning a place: Developing a compelling destination brand. Cornell Hospitality Reports, 11(2), 6–14.

- Lam, S. K., Ahearne, M., Mullins, R., Hayati, B., & Schillewaert, N. (2013). Exploring the dynamics of antecedents to consumer–brand identification with a new brand. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0301-x

- Lee, S., Rodriguez, L., & Sar, S. (2012). The influence of logo design on country image and willingness to visit: A study of country logos for tourism. Public Relations Review, 38(4), 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.06.006

- Mael, F. A., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their Alma Matier: A partial test of a reformulated model of organisational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130202

- Marcoz, E. M., Mauri, C., Maggioni, I., & Cantù, C. (2016). Benefits from service bundling in destination branding: The role of trust in enhancing cooperation among operators in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(3), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2002

- Medina-Muñoz, D. R., Medina-Muñoz, R. D., & Gutiérrez-Pérez, F. J. (2016). A Sustainable development approach to assessing the engagement of tourism enterprises in poverty alleviation. Sustainable Development, 24(4), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1624

- Medway, D., Swanson, K., Neirotti, L. D., Pasquinelli, C., & Zenker, S. (2015). Place branding: Are we wasting our time? Report of an AMA special session. Journal of Place Management and Development, 8(1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-12-2014-0028

- Merrilees, B., Miller, D., & Herington, C. (2009). Antecedents of residents’ city brand attitudes. Journal of Business Research, 62(3), 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.011

- Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2019). Smart city communication via social media: Analysing residents’ and visitors’ engagement. Cities, 94(1), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.06.003

- Mora-Rivera, J., & García-Mora, F. (2021). International remittances as a driver of domestic tourism expenditure: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Travel Research, 60(8), 1752–1770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520962222

- Morrison, A. M. (2013). Destination positioning and branding: Still on the slow boat to China. Tourism Tribune, 28(2), 6–9.

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). (2016). Tanzania Tourism Sector Survey: The 2014 International Visitors’ Exit Survey Report.

- Neergaard, H. (2007). 10 Sampling in entrepreneurial settings. Handbook of qualitative research methods in entrepreneurship, 253.

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2012). Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 997–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.11.017

- Omerzel, D. G. (2006). Competitiveness of Slovenia as a tourist destination. Managing Global Transitions, 4(2), 167–189.

- Ooi, C. S. (2004). Poetics and politics of destination branding: Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 4(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250410003898

- Pallant, J. F. (2000). Development and validation of a scale to measure perceived control of internal states. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(2), 308–337. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7502_10

- Pechlaner, H., Volgger, M., & Herntrei, M. (2012). Destination managemnet organizations as interface between destination governance and corporate governance. Anatolia, 23(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2011.652137

- Pelton, L. E., Chowdhury, J., & Vitell, Jr, S. J. (1999). A Framework for the examination of relational ethics: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 19(3), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005935011952

- Postma, A., & Schmuecker, D. (2017). Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: conceptual model and strategic framework. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2017-0022

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 79–90.

- Presenza, A., Micera, R., Splendiani, S., & Chiappa, G. D. &. (2014). Stakeholder e-involvment and participatory tourism planning: Analysis of an Italian case study. International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development, 5(3), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKBD.2014.065320

- Qu, H., Kim, L. H., & Im, H. H. &. (2011). A model of destination branding: Intergrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tourism Management, 32(3), 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.014

- Rather, R. A. (2020). Customer experience and engagement in tourism destinations: The experiential marketing perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1686101

- Rather, R. A., & Camilleri, M. A. (2019). The effects of service quality and consumer-brand value congruity on hospitality brand loyalty. Anatolia, 30(4), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2019.1650289

- Rather, R. A., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2019). Exploring and validating social identification and social exchange-based drivers of hospitality customer loyalty. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1432–1451. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0627

- Rather, R. A., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2020). Experiential marketing for tourism destination. In Saurabh Kumar Dixited (Ed). The Routledge handbook of tourism experience management in marketing. Routledge Publications.

- Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. (2003). Cross-Cultural Behaviour in Tourism: Concepts and Analysis. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Ritchie, J. B., & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination: A suistainable tourism perspective. CABI Publishing.

- Said, H., Badru, B. B., & Shahid, M. (2011). Confirmatory factor analysis (Cfa) for testing validity and reliability instrument in the study of education. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(12), 1098–1103.

- Santos, A., & Reynaldo, J. (2013). Cronbach ‘ s Alpha : A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Journal of Extension, 37(2013), 6–9.

- Saraniemi, S., & Komppula, R. (2019). The development of a destination brand identity: A story of stakeholder collaboration. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(9), 1116–1132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1369496

- Sartori, A., Mottironi, C., & Corigliano, M. A. (2012). Tourist destination brand equity and internal stakeholders: An empirical research. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(4), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766712459689

- Schultz, D. E., & Block, M. P. (2015). Beyond brand loyalty: Brand sustainability. Journal of Marketing Communications, 21(5), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2013.821227

- Sebele, L. S. (2010). Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino sanctuary trust, central district, Botswana. Tourism Management, 31(1), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.01.005

- Simpson, K., & Bretherton, P. (2009). The impact of community attachment on host society attitudes and behaviours towards visitors. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 6(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903363431

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

- Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. (2011). The relevance of visitors’ nation brand embeddedness and personality congruence for nation brand identification, visit intentions and advocacy. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.12.004

- Stryker, S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company.

- Strzelecka, M., Boley, B. B., & Woosnam, K. M. (2017). Place attachment and empowerment: Do residents need to be attached to be empowered? Annals of Tourism Research, 66(2017), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.06.002

- Tanzania Investment Report. (2022). National Bureau of Statistics (NSB). https://www.nbs.go.tz/index.php/en/investment-statistics/899-tanzania-investment-report-2022

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- Trist, E. L. (1983). Referent organizations and the development of interorganizational domains. Human Relations, 36(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678303600304

- Tsaur, S. H., Yen, C. H., & Yan, Y. T. (2016). Destination brand identity: Scale development and validation. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(12), 1310–1323. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1156003

- Tuškej, U., & Podnar, K. (2018). Consumers’ identification with corporate brands: Brand prestige, anthropomorphism and engagement in social media. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2016-1199

- United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2015). UNWTO Tourism Highlights. UNWTO.

- Vollero, A., Conte, F., Bottoni, G., & Siano, A. (2018). The influence of community factors on the engagement of residents in place promotion: Empirical evidence from an Italian heritage site. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2164

- Wassler, P., Wang, L., & Hung, K. (2019). Identity and destination branding among residents: How does brand self-congruity influence brand attitude and ambassadorial behavior? International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2271

- World Travel and Tourism Council. (2020). Economic impact reports. https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact.

- Zenker, S., Braun, E., & Petersen, S. (2017). Branding the destination versus the place: The effects of brand complexity and identification for residents and visitors. Tourism Management, 58, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.008

- Zhong, Y. Y., Busser, J., & Baloglu, S. (2017). A model of memorable tourism experience: The effects on satisfaction, affective commitment, and storytelling. Tourism Analysis, 22(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14888192562366

- Zouganeli, S., Trihas, N., Antonaki, M., & Kladou, S. (2012). Aspects of sustainability in the destination branding process: A bottom-up approach. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 21(7), 739–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2012.624299