Abstract

Geofence mobile technology can offer significant benefits to all stakeholders in the retail property sector ecosystem. This paper investigated the opportunities and challenges associated with the adoption of geofence mobile technology by retailers in South Africa. The paper adopted a qualitative research approach and interviewed property management professionals who have several years of work experiences in the retail sector in the country. As key stakeholders, retail property managers significantly contribute to the retail environment, especially with the integration of technology. Findings revealed that targeted marketing, shopper engagement and increased sales are opportunities presented by geofencing mobile technology to retailers. These opportunities potentially encourage retailers, and by implication property owners and property portfolio managers, to have management buy in and invest in employees’ skills for the adoption of geofence mobile technology. Additionally, the presence of vendor support and clear and assured data privacy and regulations are needed for the adoption of geofence mobile technology. These results represent a solid attempt to extend knowledge – in terms of research, policy, and practice – of the impact that new technologies have on the retail sector within a developing country, which is ripe for the adoption of geofence technology across its many economic sectors.

Introduction

The evolution of tracking technology combined with the rapid growth of smart mobile devices and applications has enabled a wide range of applications and efficiencies for personalising content and services to users in a specific place (Wang & Feeney, Citation2017). Individuals’ physical positions can be determined using geographical location (geolocation) data obtained from their mobile devices. This geolocation data can be of value to various users across various economic sectors in a given economy.

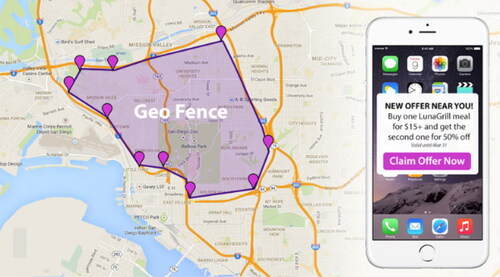

Geofencing, which is a combination of smartphones, the internet, and geo-positioning technologies, has gained popularity as a means of promoting context-based personalised services and advertisements (Bareth & Kupper, Citation2011). Geofencing technology achieves these by establishing a geographic boundary over a physical site using a global positioning system (GPS) or radio frequency identification. With smartphones easily allowing integration with apps, geofencing, and location-aware technologies, digital marketing has been revolutionised significantly in recent years (Usman et al., Citation2018; Singh et al., Citation2020; Al-Qumayri & Ahmed, Citation2021; Streed et al., Citation2017). As this happens, digital marketing, especially mobile marketing in this case, has a significant financial benefit for all stakeholders in the retail property sector ecosystem. (Singh et al., Citation2020).

For retailers and marketers, they can communicate with and deliver information to devices inside specific geographic areas once a virtual fence has been established. This valuable information is important to retailers because it provides them with a lot of details about their shoppers, like where they work and live, how frequently they commute, and which restaurants they prefer (Wang et al., Citation2019). As such, retailers can use geofencing to send notifications to shoppers by text message, email, or social media about specials, deals, or discounts at a particular merchant when the shopper is near the retailer or shopping centre (Andrews et al., Citation2016). In these instances, where shoppers have less time to reflect on their decisions, shoppers are likely to make impulse purchases when notifications occur near the point of sale (Albuquerque et al., Citation2021; Tong et al., Citation2020). Additionally, retailers can now follow their shoppers’ point progress and use that information to establish long-term relationships with them, thanks to mobile intermediaries (Bernritter et al., Citation2021).

Retail property managers are the decision-makers who can integrate geofencing technology within their properties to enhance marketing strategies, attract more tenants, and ultimately increase foot traffic. This has the potential to influence the valuation of such retail properties. Retail property managers can use quantitative value of online sales that are geo-coded and attributed to a shopping centre base as guide in the negotiation for the share of revenue generated by such online sales within a specified geographical radius of the shopping centre between tenants and landlords (Pretorius & Cloete, Citation2020).

Although not the primary adopters in the technological implementation sense, shoppers play a critical role in the adoption ecosystem. Shoppers’ acceptance and response to geofencing initiatives directly influence retailers’ and property managers’ decisions to adopt and invest in geofencing mobile technology. Ultimately this also benefits them. For instance, shoppers will be able to access valuable information on nearby points of interest, such as restaurants, thus experiencing wider choice of merchandise accompanied with price comparability. Shoppers may also receive non-monetary incentives, such as free mobile data, with any transaction made during a mobile promotion (Andrews et al., Citation2016).

Despite its potential, few African countries, including South Africa, Kenya, Egypt, Nigeria, and Ghana, currently use geofencing technology in few sectors, such as vehicle tracking, fleet management, security and marketing in some sectors in their economies (Cartrack, Citation2022). The adoption and integration of geofencing within South Africa’s retail property sector remain nascent, underscoring a critical gap in both practice and research. Existing literature predominantly focuses on the technical aspects and potential applications of geofencing, with studies such as those by Cardone et al. (Citation2014) highlighting its utility in enhancing customer engagement through context-aware notifications. However, these discussions often overlook the nuanced challenges and barriers to adoption specific to emerging markets, particularly in contexts like South Africa where digital infrastructure and consumer behaviours exhibit unique characteristics (Leibbrand, Citation2017; AlFayad, Citation2018). Moreover, the literature is scant on comprehensive analyses that consider the socio-economic, regulatory, and organizational factors influencing geofencing technology’s adoption in the retail property sector, revealing a significant research gap.

In addition, in the retail sector in these countries, however, the adoption of geofence mobile technology remains anecdotalFootnote1 – hence the lack of benefits accruing to the various actors in the retail property sector ecosystem as indicated above (Daniel, Citation2015; Leibbrand, Citation2017; Wang & Feeney, Citation2017; Andrews et al., Citation2016). This limited literature around the use of geofencing mobile technology in the retail sector in developing countries, despite these countries being ripe for the adoption of geofence technology, is worrying. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to contribute to the body of knowledge of the potential impact of geofence mobile technology on the retail sector by investigating (a) the opportunities associated with and (b) barriers to the adoption of geofence mobile technology in the retail sector in the developing world using South African retail sector as an empirical case study.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The second section provides a literature review on the meaning of geofencing technology, factors influencing its adoption, as well as shopper and user perceptions around its use. The third section describes the methods used to conduct the research, while the fourth section presents and discusses the results. Lastly, the paper ends with a conclusion.

Literature review

Understanding geofencing technology

Geofencing is a method of establishing a geographic boundary over a physical site using a GPS or radio frequency identification. It allows for remote surveillance of real-world geographic areas encircled by a virtual fence, but the user must always be followed in the background even while the mobile device is inactive (Zuva & Zuva, Citation2019). The technology is being used in vehicle tracking, fleet management, security, and marketing in some business sectors.

In the retail sector, illustrates how retailers who have subscribed to geofencing technology can have their promotions or information delivered to shoppers’ mobile devices who are near them as shoppers walk into or drive through the geofence boundary (Cardone et al., Citation2014). This information may be obtained while a shopper goes past a restaurant where the restaurant’s daily specials are provided to shoppers through text messages. Similarly, it may involve retailers detecting shoppers near their stores and serving product reviews to those shoppers via their social media channels and other platforms (Dix et al., Citation2017).

Factors influencing the adoption of geofencing mobile technology

Adoption of any technology is defined by the voluntary decision of individuals or organisations to initially embrace and operationally employ it to address issues. In the literature, several factors shape how geofence technology is adopted and used. These include customers’ perception, issues of privacy and security, regulations and policies, employees’ skills and their social environment, and organisation resources and costs of technologies.

Shoppers’ perception

Shoppers’ perception regarding the product, usage intention, and user satisfaction are usually connected with the adoption of new technology (Santa et al., Citation2019). Akman and Mishra (Citation2017) also note that user attitudes are thought to influence the impacts of a service’s perceived qualities, influencing user intentions to consume or reuse the service. If shoppers have a positive attitude toward location-based applications, they are more likely to accept those applications (Santa et al., Citation2019). Users are more likely to trust location-based services (LBS) providers if they believe they will deliver positive results in the future (Klumpe et al., Citation2020). When it comes to the adoption of LBS, trust has a negative impact on perceived risk but a positive one on usage intention (Klumpe et al., Citation2020; Dubé et al., Citation2017). However, shoppers’ gender and levels of education may have mediating effects on shoppers’ receptiveness to mobile marketing (Wang et al., Citation2020) and their ultimate intentions to make online purchases (Blut & Wang, Citation2020; Akman & Mishra, Citation2017; Lin et al., Citation2018).

Kim (Citation2021) further warns that unless real estate businesses gain a better knowledge of how smart devices can deliver tailored value as this is crucial in the mobile world, their attempt to expand their influence on mobile devices through applications, has a likelihood of swarming shoppers with choice and information overflows. These may aggravate feelings where shoppers are overwhelmed and irritated. Therefore, real estate businesses must regard apps as instruments for creating and maintaining shopper engagement through tailored and user-relevant solutions, rather than just extensions of their websites (Murillo-Zegarra et al., Citation2020).

Elsewhere, the low screen resolutions offered by smartphones have been observed to lead shoppers to reserve their research on vehicles or life insurance for bigger screen devices, such as computers, and only prefer to utilise smart mobile devices for routine purchases. As a result, mobile devices are unlikely to totally replace conventional sources of information, particularly for complex purchases. However, it has been demonstrated that shoppers who utilise smart mobile devices as an alternative channel of information, in addition to their regular channels, may have a better lifetime value than those who do not (McLean et al., Citation2020).

Privacy and security

Privacy and security concerns such as trust, perceived risk, and perceived usefulness (Klumpe et al., Citation2020) have a bearing on their adoption and use of technology that enable shoppers to make online purchases. In instances, where government surveillance affects shoppers’ privacy concerns, shoppers’ desire to supply personal information to conduct online transactions will be hampered (Steinhoff et al., Citation2019). This has to do with how data is collected, the level of accuracy, how it is accessed and used by third parties (Blut & Wang, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020). Zhou (Citation2017) indicates that the proliferation of LBS considerably increases the potential of such misuse. Because geolocation information discloses where a phone is physically located, an unethical mobile network employee could reveal such data to an acquaintance who desires to harm the phone owner (Zhou, Citation2017). The inherent possibility of a seamless trailing of sites that the user has visited in the past may also work against adoption and use of geofencing technology. In the event seamless trailing of sites happens, attackers may use such data for illegal purposes rather than for commercial activities (Steinhoff et al., Citation2019).

To encourage geofencing technology adoption and use, security measures should be versatile, agile, resilient, and capable of detecting a broad range of dangers and making timely judgments. However, Fearnley (Citation2020) warns that implementing these privacy features is quite difficult and frequently conflicts with geofence LBS’s main capabilities. Unless this is done, cyber-attacks result in a loss of reputation, shopper loss, and financial loss for enterprises, as well as a loss of trust, privacy, and financial loss for shoppers (Özoğlu & Topal, Citation2020).

Regulations and policies

Regulations and policies should be suitable for the development of information systems to be entrenched. Volkodavova et al. (Citation2019) argue that obsolete corporate regulations make introducing and implementing new technologies more difficult. Sorkun (Citation2020) adds that digitisation process may be slowed by security and regulatory concerns. These rules may include copyright and legal provisions that safeguard new products, trademarks, and corporate logos (Iqbal & Yadav, Citation2020).

Employees’ skills and their social environment

Employees’ skills and their social environments (encompassing employees’ agents and associations, as well as management buy in) have a great bearing on employees’ willingness to adopt innovations (Ahluwalia et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2019; Ghaleb et al., Citation2021). Scholars warn that rapid adoption of innovative technology and quick changes in business environments have a significant impact on employee’’ well-being – this in turn affecting their loyalty, performance, and dedication to the company. In the worst-case scenario, poorly managed introduction of smart technologies at the workplace have led to sabotage by employees (Arias-Pérez & Vélez-Jaramillo, Citation2021).

Yoo et al. (Citation2018) suggest that to boost the pace of innovation adoption inside a company, peers should provide support and encouragement to such employees with little digital skill to enable them to quickly acquire innovative skills. A social environment that massages individual’s characteristics such as perceived usefulness, personal innovativeness, prior experience, image, and satisfaction with innovation has been proven to have a higher impact on an individual’s adoption of innovative technology (Acheampong et al., Citation2017). Slimane et al. (Citation2019) add that innovation adoption is likely to be influenced by the innovation employed by others in the employee’’ social context. As such, real estate firms must create enabling conditions in form of supportive factors, such as the availability of training programmes, to encourage staff to embrace and apply innovation (Lee et al., Citation2019; Ghaleb et al., Citation2021; Slimane et al., Citation2019).

Organization resources and costs of technology

Organization resources have the power to leverage on appropriate infrastructures needed for the adoption of new technology. These infrastructures necessitate digital processes that enable a business to comprehend the environment, display the appropriate responses, assess competitor’’ shopper demands and threats, and make the appropriate judgments. In the present-day competitive world, retailers, by geofencing around the sites of their competitors will be able to compete more effectively (Arief et al., Citation2020). The most perceptible problem that businesses face is lack of access to resources as technology becomes outdated (Burch & Mohammed, Citation2019). Fountaine et al. (Citation2019) explain that the reason real estate businesses are slow to switch away from legacy systems and infrastructure could be explained by the marginal benefit acquired by shifting to a new system rather than the technological difficulty of converting services to a modern system. Moreover, Ciuffoletti (Citation2018) indicates that initial adoption of a new technology with no evident proof of concept and lack of alignment to business innovation strategy may threaten investment return in the long run.

Ecosystem for the adoption of geofence mobile technology in developing countries

There is widespread evidence that several developing countries’ markets are ripe for the adoption of geofence technologies across many of their economic sectors. Across Africa, the market reflects growth in its tech ecosystem that continues to see a record number of investments amid rising demand for digital techs (The Citizen, Citation2022). Because of the benefits of leapfrogging among other favourable conditions, there is widespread use of mobile devices in developing countries. For instance, StasSA (2021) indicates that 97.6% of South African households have access to at least one mobile phone. Beyond data costs issues that likely limit internet use, there is still room to reach wider shoppers through the short messaging service (sms), mall advertising, tv/radio adverts, etc. that do not need internet connection. In Kenya, Juma et al. (Citation2022) describe that the country has favourable conditions for mobile application use. In their study aimed at establishing the potential for a mobile-phone-based application in nature interpretation amongst visitors and guides visiting Kenyan national parks and reserves, Juma et al. (Citation2022) show that there is adequate threshold of needed transportation and hospitality infrastructure, such as charging stations and internet access that are installed in transportation hubs and carriages, making tourists in Kenya national parks and reserves more comfortable.

The evident policy shifts have also led governments and other players to invest in free Wi-Fi, for instance, around shopping centres could be the needed boost required to allow for accurate measurement of actual visits to a shopping centre (Pretorius & Cloete, Citation2020). For instance, in Kenya the government plans to roll out 25,000 free community Wi-Fi hotspots to markets around the country, while in the South Africa the government plans to connect over 33,000 community Wi-Fi hotspots nationally (Business Daily, Citation2023; Khumalo, Citation2022). When shoppers opt-in to use free in-mall Wi-Fi and provide information about themselves, retailers are able to build shopper personas allowing them to draw insights from the generic and personalised shopper data. Retailers can further get more shopper data through targeted surveys using mall Apps integrated to their Wi-Fi infrastructure. A combination of the in-mall data, drawn from the Wi-Fi infrastructure and out-mall data, using geofence mobile technology can help retailers predict what shoppers want and influence them across marketing channels.

Also, there is huge potential for the adoption of new and inventive marketing technologies since there is a sizable younger population and relatively well-off shoppers who are likely to prefer the convenience of online and mobile transactions. In South Africa, for instance, StatsSA (2021) show that younger South Africans (e.g. millennials and later generations at least 15 years) account for almost 50% of the total population. With the African younger and rich residents probably being more urban as well, it portends a fertile ground for the use of digital technologies, including geofencing technology (The Citizen, Citation2022).

So far, several developing countries, for example, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Cameroon and South Africa, have had many of their economic sectors transformed by innovation in e-hailing firms, such as Uber, Bolt, Yookoo Ride, Scoop a Cab, Airbnb, Gett, Ola Cabs, Little Cab, Free Now, Easy Taxi, and Wingz (Briefly, Citation2022; The Citizen, Citation2022). These businesses by embracing digital business strategies have expanded their market share faster and performed better than those that still followed traditional business practices (Haffke et al., Citation2017). Beyond these business models centred on sharing, such as ride-sharing and room sharing, several developing countries have also witnessed the adoption and use of geofencing mobile technology in vehicle tracking, fleet management, security and marketing in some sectors in these countries (Cartrack, Citation2022).

The above review has shown that while little is understood about geofence mobile technology and how it can impact other new business models, the little evidence mimics a potentially lucrative ecosystem for the widespread adoption, use and influence of geofence mobile technology across the entire business structures in developing countries (Lenka et al., Citation2017). More importantly, the recent global Covid-19 pandemic, which saw the South African listed real estate sectors endure loses in capitalised value, for example, may have heightened the need for retailers to embrace new technologies to generate other sources of income and bring more feet to their centres going forward.

Research approach

Data collection

This paper employed interpretivism research approach since the researchers wanted to determine participants’ comprehension, perspective, and experience rather than relying on statistics (Thanh & Thanh, Citation2015). As advised by Thanh and Thanh (Citation2015), the researchers chose qualitative research approach in form of semi-structured in-depth face-to-face interviews that allowed for flexibility in gathering information from participants’ experiences towards obtaining rich and in-depth information on the research problem at hand.

Participants, namely retail property managers, were conveniently identified by the researchers and invited to participate in the study. The choice of retail property managers was motivated by the need to select participants with work experience in the retail property sector and had some knowledge about geofence mobile technology. Retail property managers offer a wide range of services to retailers in areas such as market analysis and insights, operational support and maintenance, marketing and promotional activities, technology integration, tenant mix and placement strategy, sustainability initiatives, lease management and negotiation, and compliance and risk management. In this way, retail property managers help create and maintain an environment that is conducive to retail operations, customer satisfaction, and ultimately, sales. The respondents were easily identified and requested to participate in the survey by one of the researchers who worked in the real property sector.

The sample size of eight individuals with experience in asset management, property management, or data analysis in a property company within the city of Johannesburg agreed to participate in the interview. The sample size of eight achieved data saturation point or the point where the researchers were no longer able to obtain more additional information from participants (Dworkin, Citation2012; Alsaawi, Citation2014; Guest et al., Citation2006; Marshall et al., Citation2013). Kuzel (Citation1992) recommends six to eight interviews for a homogeneous sample in qualitative research using in-depth interviews. shows that the participants positions, industry roles, and length of experiences provided confidence in participants’ responses based on their experiences.

Table 1. Description of interview participants.

Participants were probed to respond to what they considered to be the opportunities of and main barriers to adopting and implementing geofence mobile technology in the retail property sector in South Africa. The semi-structured interviews adopted by the researchers were generally relevant since they were open-ended and permitted further probing in case further details were needed. Probing and follow up questions enabled the researcher to elicit more responses and clarity from the participants. The open-ended questions also gave the participants complete freedom to go into as much depth as possible when discussing the various subjects and bring in new information that they felt relevant to the study (see Annexure A for interview questions).

Before the interview, participants’ consent was sort and the interview only proceeded if participants agreed to it – with an option to terminate the interview at any time if they felt uncomfortable or for any other reason. Each interview took approximately 30 minutes. The interviews were conducted in English as all participants were proficient in the English language. In addition to ethical clearance that was approved by the University Ethics Committee, pseudonyms were used instead of real names in the paper, which kept the identities of the participants private.

Data analysis

The paper adopted thematic analysis as its analytical strategy. This was motivated by the fact that the huge amounts of qualitative data obtained meant that the thematic analysis, such as from transcripts in this paper’s case, was the appropriate analysis strategy. This paper used a six-phase theme analysis as defined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The six-phase theme entailed the researchers; (i) familiarising themselves with the data, (ii) generating preliminary codes, (iii) searching for themes in the data, (iv) reviewing the identified themes, (v) defining and naming the identified themes, and (vi) producing a report.

NVivo 12 software was used to load the data and code it for meanings. The first phase’s notes acted as a preliminary list of concepts for the material, emphasising important themes that arose from the data. Each data item received ‘full and equal attention,’ as recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Codes were frequently checked ensuring that meaning was not missed, and occasionally more codes were given to a data item. The researcher made notes of any potential connections within codes and recurring patterns that came to mind at the coding stage. NVivo 12 software allowed for a systematic identification of potential connections between codes and potential themes that would represent a collection of codes that appeared to be similar (For more details on what each of these phases entail, see Braun and Clarke (Citation2006)). Subsequently, discussion in the next section of the paper focuses on the identified themes.

Results and discussions

Opportunities arising from the adoption of geofence mobile technology in the retail sector

The participants were unanimous on the potentials that geofence mobile technology has to offer the retail property sector in South Africa. While responses relate directly to retailers, there are implied benefits that accrue to shoppers and property owners (landlords) as well. The following section, however, presents and discusses results associated with retailers.

Targeted marketing and shopper engagement

Geofencing mobile technology is a new means of providing targeted marketing to shoppers as their presence can be tracked within some radius near stores. VU and SU shared the following views:

Unlike traditional models where an organisation can use in-mall advertising, TV adverts, radio adverts, newspaper adverts and pamphlets to drive marketing campaigns – the technology will allow a landlord (or retailers) to study their shopper’s purchase patterns, their affinity to certain brands, when they commute, when they spend time and how much time they spend in shopping malls, and their preferred mediums of communication (SU).

This technology involves the tracking of people and then generating data points that can be used to draw insights and create specialised targeted marketing campaigns to shoppers (VU).

Retailers can send geo-based advertisements using a variety of technologies, such as near-field communications, beacons, and GPS when shoppers are near their stores. This proximity to the store provides a moment when shoppers are more likely to consider a mobile promotion and, as a result, make a buy, sometimes impulse purchases (Ghose et al., Citation2019). Retailers can use beacon technology to send shoppers mobile promotions that contain in-store maps to assist them in finding the item they want. One respondent indicated that:

Retailers can send them notifications on promotions and specials only relevant to the individual shopper. This will eliminate random advertising and reduce marketing budgets. The technology will, therefore, also allow businesses to drive foot traffic into their malls as the mobility data will allow them to achieve an optimal tenant mix aimed at the right demographic and LSM (living standard measure) groups in their catchment areas (SH).

The perceived advantages of a new innovation are determined by the data that each decision-maker has at their disposal (Chavas & Nauges, Citation2020). Some respondents shared similar views:

The insights drawn from the data generated from shoppers would have to be presented to marketing teams, leasing teams, renewal teams, asset management and exco so that such insights may be implemented (GO).

By using geofence mobile technology, the marketing budget can be spent more efficiently because it will be directed at the correct market segment (RA).

Increased sales

Due to the freedom of time and location offered by geofencing mobile technology, retailers can engage shoppers through special offers at any time. Retailers may gain a better understanding of their shoppers by collecting useful data on them through mobile channels. Automated systems and digitised procedures give retailers access to up-to-date information on the go. Two respondents had this to say:

Geofence mobile technology enables retailers to build differentiated experiences based on the demographics and preferences of shoppers in their catchment areas and those visiting their malls, thereby increasing sales (RA).

There will also be an opportunity to draw in shoppers who visit competitors by looking at the brands they visit and possibly getting these brands (tenants) into their shopping centres (GO).

Mobile advertising can also help retailers decrease market research expenses (Dwivedi et al., Citation2021). When shoppers use geofence mobile, retail stores can get important data from digital recognition, like how often shoppers visit, how long they stay, if they are new or return clients, how busy the business is when they go, what they buy, how much, how many, and what kinds and what mobile operator they use. Retailers can accomplish their marketing goals at a cheap cost by using digital and social media promotions (Ajina, Citation2019).

The type of value that retailers provide to shoppers through mobile advertising may present serious risks (Ajina, Citation2019). For example, giving monetary rewards runs the risk of undermining the company’s price strategy. In addition, shoppers may become used to receiving discounts from the shop, which may deter them from purchasing at full price. Non-monetary value exchanges, on the other hand, may not be sufficient to encourage desired shopper behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2019). When a product is sold at a lower price, discounts pose the risk of lowering its value. Owing to the risk of weakening the brand, manufacturers and retailers may disagree on the quantity and nature of mobile promotions to provide.

Barriers to the adoption of geofence mobile technology in the retail property sector

Still there is need to address some of the issues respondents highlighted they may stand on the way of adoption and use of geofencing mobile technology in developing countries, such as South Africa. The respondents were unanimous that for geofencing mobile technology to be fully adopted and its benefits accrue to retailers, and by implication to shoppers and property owners alike, bottlenecks around management buy-ins, employees’ skills and competence, and costs of technology need attention.

Some respondents shared the view that management buy-in is critical for technology adoption in an organisation:

If management (of retail companies) embraces a culture of technology and new ideas, this should trickle down the entire organisation and will result in easy adoption (HO).

With the adoption of any new technology, you will need management buy-in which then needs to trickle down to business units and employees (GO).

It is critical that management buys in and establishes a culture around data and business intelligence (RA).

Adoption will depend on whether an organisation has employees with capabilities to use and draw insights from the use of this technology or whether an organisation will have to hire new people who will be an added cost on human resources (KC).

There has been a slow move to implement this technology in this country because of the high costs of technology and data (SU).

The cost of technology and a company’s resource would also influence adoption (VU).

Adoption of new technology comes with an extra cost of training staff on its use in addition to the initial cost of the technology (HO).

If people are going to be tracked, it is critical that no sensitive information is shared or lost, as this can cause an organisation’s reputational risk and litigation (SU).

The ever-changing privacy regulation poses a big challenge for most technologies considering that they are dependent on consumer data. Technology like geofencing uses consumer information to track and send a personalised advertisement to shoppers. Under the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), individuals are given statutory protection over their private data. Therefore, businesses looking to adopt this technology will be looking at challenges around data sharing without consent (SH).

Conclusion

The research that informs this paper is published at a time when marketing continues to face unprecedented changes. The paper set out to investigate (a) the opportunities associated with and (b) barriers to the adoption of geofence mobile technology in the retail sector using South African retail sector as an empirical case study. It thus contributes to the body of knowledge of the potential impacts of geofence mobile technology on the retail sector in the developing world.

As evident in the literature that geofence mobile technology can offer significant benefits to all stakeholders in the retail property sector ecosystem, this paper’s findings concur. While participants’ responses in this paper relate directly to the benefits that accrue to retailers, there are implied benefits that accrue to shoppers and property owners (landlords) as well. Retailers are able to implement targeted marketing and positive shopper engagement in the process succeeding in the development of brand compliance. Ultimately these events allow retailers to boost footfall and trading densities needed for increased sales.

By implication, shoppers are able to access valuable information on nearby points of interest, such as restaurants, thus experiencing wider choice of merchandise accompanied with price comparability. Similarly, mobile promotions also mean that shoppers are able to enjoy financial benefits through price reductions and free mobile data. Property portfolio managers are able to tap into massive geo-coded data attributed to shopping centre(s) base as guides in the negotiation for the share of revenue generated by such online sales within a specified geographical radius of the shopping centre between tenants and lessees (Pretorius & Cloete, Citation2020). This is true for developed and developing economies, such as South Africa. Still barriers, such as bottlenecks around management buy-ins, employees’ skills and competence, and costs of technology, that were unanimously highlighted by the participants need attention.

The above benefits highlighted by this study are possible to countries, such as South Africa, since these countries are ripe for geofencing technology since the needed ecosystems are maturing. These maturing ecosystems are manifested in various ways. This is experience through the adoption of relevant technologies by various sectors of their economies allowing such sectors to create geofence boundaries in their business models. These should provide a sufficient threshold of retailers and shopping centre owners that are inclined to embrace the use of the technology in retail. Additionally, the move towards the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) means that such countries are buzzing with certain segments of their population that are already disposed with digital marketing and are sufficiently internet savvy and reliant on their mobile devices for shopping, whether online or in person. More importantly, the recent Covid-19 pandemic has heightened the need for all economic sectors to embrace new technologies to enhance shopper experiences, increase loyalty, feet and trading densities, globally.

Given the limited adoption of geofence mobile technology in South Africa there was a potential for the results of this paper not to generalized. This was addressed by purposely identifying widely knowledgeable retail property managers offer a wide range of services to retailers. However, the paper was limited in scope since didn’t delve deeper into the costs and functional and non-functional requirements of implementing geo-fencing technology in specific organizations, as that was beyond the scope of the present paper. Similarly, the paper did not focus on how data protection laws, such as the Protection of Personal Information Act in South Africa (see Daigle (Citation2021) for a list of countries with data protection laws as of September 2020), may impact the use of the geofencing mobile technology in such countries needs further examinations. Future research could also focus on quantitative-empirical approach where the development and testing of hypotheses utilizing surveys and statistical analyses to quantify the impact of specific barriers and drivers for the geofencing technological adoption could be explored. This direction would not only complement the insights gained from the current qualitative study but also enhance the generalizability of the findings across different contexts and sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Koech Cheruiyot

Koech Cheruiyot is a senior lecturer in the School of Construction Economics and Management at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Cheruiyot’s areas of expertise are in urban economics, real estate economics, trade/market area analysis and shopping centres. His scholarship in real estate has appeared in Journal of Corporate Real Estate, Journal of Real Estate Literature, Journal of Sustainable Real Estates, among others.

Kalasipa Moenyane

Kalasipa Moenyane has a Masters in Property Development and Management from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. As a qualified actuarial analyst, he is interested in studying consumer behaviour and is currently a manager in customer analytics at a real estate investment trust (REIT) in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Notes

1 One of the property portfolio managers overseeing one of the shopping malls in the City of Johannesburg alluded that they use geofence technology to gauge customer traffic to their malls. This assists them in planning tenancy. Unfortunately, all process is proprietary and cannot be identified.

References

- Acheampong, P., Zhiwen, L., Antwi, H. A., Otoo, A. A. A., Mensah, W. G., & Sarpong, P. B. (2017). Hybridizing an extended technology readiness index with technology acceptance model (TAM) to predict e-payment adoption in Ghana. American Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 5(2), 1–14.

- Ahluwalia, S., Mahto, R. V., & Walsh, S. T. (2017). Innovation in small firms: Does family vs. non-family matter? Journal of Small Business Strategy, 27(3), 39–49.

- Ajina, A. S. (2019). The perceived value of social media marketing: An empirical study of online word-of-mouth in Saudi Arabian context. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 6(3), 1512–1527. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.6.3(32)

- Akman, I., & Mishra, A. (2017). Factors influencing consumer intention in social commerce adoption. Information Technology & People, 30(2), 356–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-01-2016-0006

- Albuquerque, D. D., Bhavani, G., Gaur, B., & Kuttipravan, S. (2021 A smart mobile application to boost grocery shoppers experiential marketing [Paper presentation]. 2021 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Knowledge Economy (ICCIKE), In 213–218. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCIKE51210.2021.9410740

- AlFayad, F. S. (2018). Geofencing in the GCC and China: A marketing trend that’s not going away. Journal of Marketing and Consumer Research, 46, 84–98.

- Al-Qumayri, R. A., & Ahmed, M. (2021). The use of digital marketing tools and practices of multinational corporations to the SME’S of the Middle East. Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 18(12), 52–63.

- Alsaawi, A. (2014). A critical review of qualitative interviews. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 3(4), 149–156.

- Andrews, M., Goehring, J., Hui, S., Pancras, J., & Thornswood, L. (2016). Mobile promotions: A framework and research priorities. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 34(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.03.004

- Andrews, M., Luo, X., Fang, Z., & Ghose, A. (2017). Mobile ad effectiveness: Hyper-contextual targeting with crowdedness. Marketing Science, 35(2), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2015.0905

- Arias-Pérez, J., & Vélez-Jaramillo, J. (2021). Understanding knowledge hiding under technological turbulence caused by artificial intelligence and robotics. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(6), 1476–1491. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2021-0058

- Arief, R. R., Renaldi, F., Umbara, F. R., & Bon, A. T. (2020). Dynamic geofencing in supervision of seller performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 1388–1395.

- Bareth, U., & Kupper, A. (2011). Energy-efficient position tracking in proactive location-based services for smartphone environments. In. 2011 IEEE 35th Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference, 516–521. IEEE.

- Bernritter, S. F., Ketelaar, P. E., & Sotgiu, F. (2021). Behaviorally targeted location-based mobile marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(4), 677–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00784-0

- Blut, M., & Wang, C. (2020). Technology readiness: A meta-analysis of conceptualizations of the construct and its impact on technology usage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(4), 649–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00680-8

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briefly. (2022). List of taxi apps in South Africa, accessed 23 October 2022, https://briefly.co.za/52647-list-taxi-apps-south-africa.html

- Business Daily. (2023). Kenya starts roll out of 25,000 free Wi-Fi hotspots to markets, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/corporate/technology/city-market-gets-free-internet-hotspot-in-e-commerce-push-4014484

- Burch, Z. A., & Mohammed, S. (2019). Exploring Faculty perceptions about classroom technology integration and acceptance: A literature review. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES), 5(2), 722–729. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/facpubs/307

- Camilleri, M. A. (2018). Integrated marketing communications. In Travel marketing, tourism economics and the airline product (pp. 85–103). Springer.

- Cardone, G., Cirri, A., Corradi, A., Foschini, L., Ianniello, R., & Montanari, R. (2014). Crowdsensing in urban areas for city-scale mass gathering management: Geofencing and activity recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal, 14(12), 4185–4195. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2014.2344023

- Cartrack. (2022). Why geofencing is a crucial part of fleet management, accessed 16 July 2022, https://www.cartrack.co.za/blog/why-geofencing-is-a-crucial-part-of-fleet-management

- ChartItSpot. (2023). Geo-fencing and geo-targeting help retailers reach customers, accessed February 10, 2023, https://chargeitspot.com/geo-fencing-and-geo-targeting-help-retailers-reach-customers/

- Chavas, J. P., & Nauges, C. (2020). Uncertainty, learning, and technology adoption in agriculture. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 42(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13003

- Ciuffoletti, A. (2018). Low-cost IoT: A holistic approach. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks, 7(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan7020019

- Daigle, B. (2021). Data protection laws in Africa: A pan-African survey and noted trends. Journal of International Commerce and Economics, 1–27.

- Daniel, L. (2015). SA retailers yet to harness location-based messaging, accessed 16 July 2022, https://www.itweb.co.za/content/YKzQenvj6xQvZd2r

- Dix, S., Phau, I., Jamieson, K., & Shimul, A. S. (2017). Investigating the drivers of consumer acceptance and response of SMS advertising. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2016.1251526

- Dubé, J. P., Fang, Z., Fong, N., & Luo, X. (2017). Competitive price targeting with smartphone coupons. Marketing Science, 36(6), 944–975. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2017.1042

- Dwivedi, G., Srivastava, S. K., & Srivastava, R. K. (2017). Analysis of barriers to implement additive manufacturing technology in the Indian automotive sector. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 47(10), 972–991. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-07-2017-0222

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., Jain, V., Karjaluoto, H., Kefi, H., Krishen, A. S., Kumar, V., Rahman, M. M., Raman, R., Rauschnabel, P. A., Rowley, J., Salo, J., Tran, G. A., & Wang, Y. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168

- Dworkin, S. L. (2012). Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(6), 1319–1320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

- Fearnley, N. (2020). Micromobility – Regulatory challenges and opportunities. In Shaping smart mobility futures: Governance and policy instruments in times of sustainability transitions (pp. 169–186). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Fountaine, T., McCarthy, B., & Saleh, T. (2019). Building the AI-powered organization. Harvard Business Review, 97(4), 62–73.

- Ghaleb, E. A., Dominic, P. D. D., Fati, S. M., Muneer, A., & Ali, R. F. (2021). The assessment of big data adoption readiness with a technology–organization–environment framework: A perspective towards healthcare employees. Sustainability, 13(15), 8379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158379

- Ghose, A., Li, B., & Liu, S. (2019). Mobile targeting using customer trajectory patterns. Management Science, 65(11), 5027–5049. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3188

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Haffke, I., Kalgovas, B., & Benlian, A. (2017 The transformative role of bimodal IT in an era of digital business [Paper presentation]. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2017.660

- Itweb. (2022). Mobile marketing strategies for small businesses mobile marketing strategies for small businesses. | ITWeb

- Iqbal, B. A., & Yadav, A. (2020). Copyright and intellectual property in digital business: Issue of protection and retrieval of investment in intellectual creation. In Digital business strategies in blockchain ecosystems (pp. 555–567). Springer.

- Juma, L. O., Bakos, I. M., Juma, D. O., & Khademi-Vidra, A. (2022). Mobile-application usage potential for nature interpretation and visitor management at Maasai Mara national reserve, Kenya; wildlife viewers ‘perspectives. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 43(3)2022, 1163–1174. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.43338-932

- Kang, M. Y., & Park, B. (2018). Sustainable corporate social media marketing based on message structural features: Firm size plays a significant role as a moderator. Sustainability, 10(4), 1167–1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041167

- Khumalo, S. (2022). Govt revises plan to roll out 33 000 Wi-Fi hotspots, and ropes in small business, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.news24.com/fin24/companies/govt-revises-plan-to-roll-out-33-000-wi-fi-hotspots-and-ropes-in-small-business-20220520

- Kim, E. (2021). In-store shopping with location-based retail apps: Perceived value, consumer response, and the moderating effect of flow. Information Technology and Management, 22(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-021-00326-8

- Kim, J., Thapa, B., & Jang, S. (2019). GPS-based mobile exercise application: An alternative tool to assess spatio-temporal patterns of visitors’ activities in a national park. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 37(1), 124–135.

- Kim, S. H., Jang, S. Y., & Yang, K. H. (2017). Analysis of the determinants of Software‐as‐a‐Service adoption in small businesses: Risks, benefits, and organizational and environmental factors. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(2), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12304

- Klumpe, J., Koch, O. F., & Benlian, A. (2020). How pull vs. push information delivery and social proof affect information disclosure in location-based services. Electronic Markets, 30(3), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-018-0318-1

- Kuzel, A. J. (1992). Sampling in qualitative inquiry. Research Methods for Primary Care, 3, 31–44.

- Lee, J., Suh, T., Roy, D., & Baucus, M. (2019). Emerging technology and business model innovation: The case of artificial intelligence. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 5(3), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc5030044

- Leibbrand, M. R. (2017). [Geofencing–enhancing the effectiveness of mobile marketing]. [Doctoral dissertation].

- Lenka, S., Parida, V., & Wincent, J. (2017). Digitalization capabilities as enablers of value co‐creation in servitizing firms. Psychology & Marketing, 34(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20975

- Lin, C. T., Chen, C. W., Wang, S. J., & Lin, C. C. (2018). The influence of impulse buying toward consumer loyalty in online shopping: A regulatory focus theory perspective. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 14(11), 14611–14621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-018-0935-8

- Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

- McLean, G., Osei-Frimpong, K., Al-Nabhani, K., & Marriott, H. (2020). Examining consumer attitudes towards retailers’ m-commerce mobile applications–An initial adoption vs. continuous use perspective. Journal of Business Research, 106, 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.032

- Murillo-Zegarra, M., Ruiz-Mafe, C., & Sanz-Blas, S. (2020). The effects of mobile advertising alerts and perceived value on continuance intention for branded mobile apps. sustainability, 12(17), 6753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176753

- Özoğlu, B., & Topal, A. (2020). Digital marketing strategies and business trends in emerging industries. In Digital business strategies in Blockchain ecosystems (pp. 375–400). Springer.

- Pretorius, J. A., & Cloete, C. E. (2020). Retail turnover clauses in an online world. Journal of Business & Retail Management Research, 14(03), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.24052/JBRMR/V14IS03/ART-05

- Republic of South Africa. (2013). Protection of personal information act no. 4 of 2013. Pretoria.

- Santa, R., MacDonald, J. B., & Ferrer, M. (2019). The role of trust in e-Government effectiveness, operational effectiveness and user satisfaction: Lessons from Saudi Arabia in e-G2B. Government Information Quarterly, 36(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.10.007

- Singh, J., Mittal, A., Mittal, R., Singh, K., & Malik, V. (2020). i-Fence: A spatio-temporal context-aware geofencing framework for triggering impulse decisions. In International Conference on Big Data Analytics (pp. 63–80). Springer.

- Slimane, K. B., Chaney, D., Humphreys, A., & Leca, B. (2019). Bringing institutional theory to marketing: Taking stock and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 105, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.042

- Sorkun, M. F. (2020). Digitalization in Logistics Operations and Industry 4.0: Understanding the Linkages with Buzzwords. In Digital business strategies in blockchain ecosystems (pp. 177–199). Springer.

- Steinhoff, L., Arli, D., Weaven, S., & Kozlenkova, I. V. (2019). Online relationship marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(3), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-0621-6

- Streed, O. J., Cliquet, G., & Kagan, A. (2017). Optimizing geofencing for location-based services: A new application of spatial marketing. In Ideas in marketing: Finding the new and polishing the old (pp. 203–206). Springer.

- Suganya, V. (2022) Usage and perception of geofencing. EPRA International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Studies 9(2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.36713/epra9463

- The Citizen. (2022). Ride-hailing services find success in Africa’s urban centres, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/magazines/ride-hailing-services-find-success-in-africa-s-urban-centres-3835826

- Thanh, N. C., & Thanh, T. T. (2015). The interconnection between interpretivist paradigm and qualitative methods in education. American Journal of Educational Science, 1(2), 24–27.

- Tong, S., Luo, X., & Xu, B. (2020). Personalized mobile marketing strategies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00693-3

- Tran, T. P. (2017). Personalized ads on Facebook: An effective marketing tool for online marketers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.010

- Usman, M., Asghar, M. R., Ansari, I. S., Granelli, F., & Qaraqe, K. A. (2018). Technologies and solutions for location-based services in smart cities: Past, present, and future. IEEE Access. 6, 22240–22248. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2826041

- Volkodavova, E. V., Zhabin, A. P., Yakovlev, G. I., & Khansevyarov, R. I. (2019). April. Key priorities of business activities under economy digitalization. In International scientific conference “digital transformation of the economy: Challenges, trends, new opportunities (pp. 71–79). Springer.

- Wang, S., & Feeney, M. K. (2017). Determinants of information and communication technology adoption in municipalities. The American Review of Public Administration, 46(3), 292–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014553462

- Wang, X., Pacho, F., Liu, J., & Kajungiro, R. (2019). Factors influencing organic food purchase intention in developing countries and the moderating role of knowledge. Sustainability, 11(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010209

- Wang, Y., Genc, E., & Peng, G. (2020). Aiming the mobile targets in a cross-cultural context: Effects of trust, privacy concerns, and attitude. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2019.1625571

- Yoo, W., Yu, E., & Jung, J. (2018). Drone delivery: Factors affecting the public’s attitude and intention to adopt. Telematics and Informatics, 35(6), 1687–1700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.04.014

- Zhou, T. (2017). Understanding location-based services users’ privacy concern: An elaboration likelihood model perspective. Internet Research, 27(3), 506–519. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0088

- Zuva, K., & Zuva, T. (2019). Tracking of customers using geofencing technology. International Journal of Scientific Research & Engineering Technology, 13, 10–15.

Annexure A.

Semi-structured interview questions

Section A

How many years have you been working in the property sector/asset management/leasing?

What is your speciality?

What is your position/job title?

How many years have you been in your current position?

How many years have you been in the retail property sector?

Do you belong to any professional property bodies in South Africa? In which capacity?

What is your age range?

Section B

What would influence your clients (retailers) to adopt geofence mobile technology?

What are the opportunities that accrue from the implementation of geofence mobile technology)?

What do you consider to be the main challenges with adopting geofence mobile technology?