Abstract

This paper aims to develop a conceptual framework that elucidates the factors that impact sustainable luxury brand marketing, specifically focusing on the luxury fashion industry. The framework aims to highlight the role played by the industry in promoting economic, social, and environmental sustainability. By examining these factors, the study seeks to contribute to a better understanding of how luxury fashion brands can effectively incorporate sustainability into their marketing strategies, thereby fostering a more sustainable and responsible approach to luxury consumption. Applying the theoretical framework derived from the literature review and systematic mapping approach, we examine its relevance in the luxury fashion market. This exploration allows us to assess its practical applicability and gather empirical evidence regarding sustainable brand marketing in this context. This research will give an in-depth analysis of the major elements influencing the consumption of sustainable luxury goods. The findings expand our understanding of the sustainable practices adopted by luxury fashion brands, providing valuable insights for academia and the industry. This study’s implications are profound: luxury brand managers can enhance brand value through insights on sustainable fashion consumption drivers, while sustainable brands gain strategies for audience engagement and loyalty.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Governments, private organization and consumers are increasingly advocating the need to adopt more ecologically sustainable consumption and business models. This groundswell of support is driven by concerns about the harmful environmental effects of climate change and the limited natural resources that are being depleted due to growing populations, especially in agriculture. Sustainability practices aim to meet present needs without compromising the needs of future generations (Franco et al., Citation2019; Kerr & Landry, Citation2017). The luxury fashion industry is one sector that has been particularly scrutinized for its business practices concerning sustainability.

Recently the fashion industry has come under critical scrutiny from the media. Despite being a US $3 trillion industry representing 2% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (Fashion United, 2018; GDP), the industry’s sustainability shortcomings have been exposed by various incidents, such as Burberry’s burning of unsold clothes and the BBC’s documentary ‘Fashion’s Dirty Secrets’. These events have shed light on the social impact of fashion and raised concerns about traditional fashion production and consumption practices. To address these concerns, sustainable luxury fashion (SLF) has emerged as a term encompassing clothing and behaviors that are less harmful to people and the planet. This movement has introduced alternative approaches to fashion, such as eco-fashion, ethical fashion, and slow-fashion, which challenge the rest of the industry to slow down and adopt more sustainable practices (Amatulli, De Angelis, & Donato, Citation2021). While the practical climate for SLF is rapidly developing through various initiatives, the academic literature, with few exceptions has been slow to define and conceptualize SLF (Henninger et al., Citation2016).

Unlike other industries with modest sustainability records, luxury fashion companies have faced criticism for damaging biodiversity, animal abuse, generating waste and pollution, and exploitative labor practices, especially in developing countries (Hepner et al., Citation2020; Woodside & Fine, Citation2019). Moreover, luxury fashion is accused of failing to use recycled and reusable materials and of shunning the circular economy. Despite these concerns, the luxury fashion sector has grown astoundingly, with a retail market of over US $1 trillion (Brosseau et al., Citation2019). Luxury goods and services were once only accessible to the wealthy, but now younger consumers and all social classes can afford them, a phenomenon known as the democratisation of luxury (Jain et al., Citation2017). In addition to increasing consumer desire for luxury brands, this democratisation, facilitated by fashion companies, launched affordable brands marketed through shopping malls or sold online, such as Polo Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and Tag Heuer Hepner (Woodside & Fine, Citation2019). These brands often take advantage of lower production costs to enhance affordability and are referred to as ‘masstige’—having broad consumer accessibility while maintaining an image of prestige (Diddi & Niehm, Citation2017).

Luxury fashion brands significantly impact the economy, with the industry valued at US $240 billion (Hashmi, Citation2017). However, many luxury firms are not profitable due to intense competition and abundant brand choices for consumers in the global market. Sustainable brand marketing suggests that a strong brand identity is essential to compete in the luxury fashion market (Böcker & Meelen, Citation2017). This can be achieved through various means, including innovative and impeccable product craftsmanship, innovation in sustainable practices, exclusivity, recognizable style, and premium pricing (Legere & Kang, Citation2020). From the customer’s perspective, luxury brands offer multifaceted benefits, such as social status, identity affirmation, and a sense of belonging. To maintain a strong brand identity and relevant branding strategy, luxury firms have invested millions of dollars in developing comprehensive corporate brand identities, such as the top four conglomerates Prada, Gucci Group NV, LVMH, and Richemont Group. A successful corporate branding strategy allows luxury firms to create distinguishable brands that attract customers’ preferences and loyalty (Kapferer & Valette-Florence, Citation2022).

In the context of this background, this theoretical paper is positioned. This paper aims to address two primary objectives. Firstly, it sheds light on the sustainability concerns that the luxury fashion industry is facing. Secondly, it seeks to comprehensively explore factors influencing sustainable luxury consumption and its role in helping luxury fashion marketers understand their consumers and develop sustainable marketing strategies (Athwal et al., Citation2019; Kapferer & Michaut-Denizeau, Citation2020). Balancing survival goals with sustainability objectives is a significant challenge for luxury fashion marketers. Marketing theory and concepts must shift to address the negative impact of consumption (Hepner et al., Citation2020; Kaur & Arora, Citation2019). While some corporate sectors have actively adopted the sustainability agenda, the luxury industry has lagged behind (Hashmi, Citation2017). This is interesting because the luxury market is viewed as exacerbating socioeconomic disparities, igniting social instability, and ignoring environmental and animal welfare concerns (Kong et al., Citation2021). This paper discusses sustainability measures that cover social, environmental, and economic aspects as outlined in the triple bottom line (TBL) model. While our study is focused on the luxury fashion sector, the insights presented in this paper are highly relevant to managers in other industries. By understanding their consumers better, luxury fashion marketers can develop sustainable business models that strike a balance between survival goals and sustainability objectives. Through this paper, we hope to encourage the shift towards sustainable practices in the luxury fashion industry (Amatulli, De Angelis, Peluso, et al., Citation2021). By exploring the reasons why customers buy luxury goods and to what extent they are aware of the ethical implications of such consumption, we can help the luxury fashion industry transition towards sustainability and promote ethical consumption (Amatulli, De Angelis, & Donato, Citation2021; Dean, 2018; Kapferer & Michaut-Denizeau, Citation2020).

Thus, the paper starts with a discussion of the conceptual framework and an overview of the literature concerning Schwartz’s value dimensions and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Followed by the conceptual framework, discussion and implications and finally, the limitations and future research scope of the study is provided in the last section.

2. Overview of literature

Based on the existing literature, there is a possibility for developing the idea of sustainable luxury and researching consumer and marketing trends in the luxury sector. This agenda is further extended and demonstrates the need for further research to support the sustainable growth of the luxury industry. Effective marketing tactics for future sustainable-luxury products are yet unknown, and a precise definition of sustainable luxury is still elusive. The research has shown that the luxury industry stands to win and lose significantly from moving toward more sustainable practices and that any sustainability plan must be in line with the core values of luxury, which include heritage, quality, longevity, and timelessness (Jain & Mishra, Citation2020; Li & Leonas, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2021).

2.1. Sustainability

The broadly accepted definition of sustainable development is rooted in the principle of meeting current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Brundtland Commission. World Commission on Environment and Development WCED, Citation1987, p. 43). This foundational concept acknowledges the finite nature of resources and emphasizes the need for responsible management to ensure their sustainability for future generations. In contemporary times, consumers exhibit a distinct preference for ethical and environmentally conscious products that align with their values and beliefs (Hennigs et al., Citation2013; Jain & Mishra, Citation2020). As a holistic concept, sustainability extends beyond environmental considerations, encompassing aspects such as personal well-being, elevated quality of life, and a sense of responsibility toward the community (Pavione et al., Citation2016). Consumers today actively seek out green products that not only resonate with their values but also contribute to a more sustainable and responsible lifestyle. Previous studies have categorized sustainable fashion consumption into sociocultural, ego-centred, and eco-centered values (Cervellon & Shammas, Citation2013). Moreover, luxury sustainability customer values have been classified into financial, functional, personal, and interpersonal categories (Hennigs et al., Citation2013). Ki and Kim (Citation2016) revealed that intrinsic values related to personal style and social consciousness were significant drivers of sustainable luxury purchases. In contrast, environmental consciousness did not significantly impact these decisions.

2.2. Luxury and sustainability

Luxury and sustainability have traditionally been viewed as incompatible by consumers, as indicated by research conducted by Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau (Citation2014) and Kong et al. (Citation2016). However, since 2015, the luxury industry has drawn the attention of advocates for sustainable development, according to Johnstone and Tan (Citation2015). Luxury consumers tend to view certain luxury items as inherently sustainable, as noted in various studies (Amatulli et al., Citation2017; Diddi & Niehm, Citation2017). Scholars refer to this newfound compatibility between luxury and sustainability as ‘positive luxury’ (Winston, 2017), ‘green luxury’ (Kong et al., Citation2016), and ‘responsible luxury’ (Janssen et al., Citation2014). According to Kapferer and Laurent (Citation2016), luxury goods must have rare raw materials, exceptional quality, noble components, and preserve artisanal practices across generations. Additionally, transparency in manufacturing conditions is essential for luxury, as high quality that harms the environment cannot be considered true luxury. Thus, Kong et al. (Citation2016) argues that luxury products created locally by talented artists respecting the source of raw materials are consistent with sustainability. Many major luxury groups have also transformed their value chain into an eco-friendly one, including post-purchase recycling, according to Winston (2017) and Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau (Citation2020).

2.3. Fashion and sustainability

There has been a prevailing assumption that fashion and sustainability are incompatible concepts. Fashion is often associated with constant change and innovation, leading to short production runs and fast style cycles, which can result in waste. In contrast, sustainability is related to enduring quality over time (Hashmi, Citation2017). However, some categories of luxury fashion, such as luggage, watches, or jewellery, can leverage their heritage to produce high-quality, durable, and timeless products which can be sustainable. In this context, luxury and sustainability can be interdependent, where both benefit from such a partnership. Moreover, merging sustainability and luxury appeals to customers, especially to new generations of consumers who value brands that incorporate sustainable practices as part of their values. Consumer behavior is shifting from self-indulgence to community concerns, from conspicuous consumption to conscientious consumption, and from immediate gratification to concern for future generations (Jain et al., Citation2017). Therefore, many luxury brands are including new practices and evolving sustainable business practices to meet the expectations of customers who are more sensitive to a brand’s sustainability narrative.

Sustainability can also become a marketing strategy. A sustainable image can differentiate one brand from another, providing a competitive advantage. Sustainability practices require considering the entire value chain, which may require creating strategic partnerships with suppliers. By doing so, luxury brands can appeal to their customers’ expectations while also benefiting from a sustainable image.

2.4. Major sustainability challenges and strategies

Luxury fashion companies must quickly recognize and respond to sustainability challenges and adopt sustainable models. This section discusses the significant sustainability challenges that fashion luxury firms face in three essential dimensions: social, environmental, and economic.

Regarding social challenges, the luxury fashion industry has been criticized for accepting dangerous working conditions in factories, engaging in gender inequality, and paying meager wages. The fashion luxury sector faces social challenges on two levels: Firstly, to safeguard the well-being of all employees (the firm-oriented approach), the organization should ensure that all actions enhance employees’ quality of life within the company while also being aware of arrangements across the entire supply chain. Secondly, to protect the well-being of society (the market-oriented approach), the concern should be for the whole industry, not just the firm. Market-level involvement ensures that decisions made at the industry level are informed and beneficial for all stakeholders (Rattalino, Citation2018). To achieve this, firms in a particular market need to monitor trends in consumer attitudes and behavior continuously, changes to government regulations and policies at home and abroad, and emerging technological innovations. For instance,

LVMH, a conglomerate of luxury brands, has taken comprehensive steps towards sustainability. Brands under the LVMH umbrella, such as Louis Vuitton and Dior, have not only embraced sustainable materials and practices within their collections and marketing campaigns but have also recognized the imperative of addressing social issues. LVMH’s ‘Life 360’ sustainability strategy plays a pivotal role in guiding these efforts, illustrating a collective commitment not only to environmental responsibility but also to addressing social challenges that are inherent in the pursuit of sustainable luxury fashion. – Angevine et al. (Citation2021)

Patagonia’s emphasis on quality and socially responsible consumption sets a noteworthy example. Their marketing strategy, though not typical of luxury brands, underscores the company’s unwavering commitment to social values. By encouraging consumers to choose fewer, higher-quality items, Patagonia not only promotes responsible consumption but also fosters a community of conscientious consumers who prioritize ethical and socially responsible choices in the domain of fashion. – Rattalino (Citation2018)

Environmental challenges are a significant concern for the luxury fashion industry as it relies heavily on unique and rare natural resources threatened by climate change, population growth, biodiversity loss, and excessive demand. This situation could impact the availability and cost of critical materials that affect the price of luxury goods. The fashion luxury sector faces two significant environmental challenges. Firstly, luxury firms must ensure and preserve natural resources used in production, which is crucial for maintaining their competitive advantage. This requires adopting new practices to regenerate ecosystems and secure the supply of raw materials. Secondly, luxury firms must find new types of sustainable natural resources or create substitutes for current raw materials through production and design innovations. To exemplify,

Gucci, a leading luxury fashion brand, has launched the ‘Gucci Equilibrium’ platform, dedicated to environmental and social sustainability. This initiative includes a commitment to carbon neutrality and the utilization of sustainable materials such as ECONYL, a regenerated nylon fabric sourced from discarded fishing nets. Gucci’s marketing campaigns emphasize these sustainability efforts, appealing to eco-conscious consumers. – Hendriksz (Citation2018)

Burberry, a luxury brand, has embarked on ambitious sustainability goals, with a commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2022. The ‘ReBurberry’ initiative centers on recycling and upcycling, while ‘Burberry Regeneration’ supports environmentally-focused youth projects. These initiatives take center stage in Burberry’s marketing campaigns, underscoring their unwavering dedication to sustainability. – Angevine et al. (Citation2021)

On the economic front, luxury firms must take strategic and operational actions to become ecologically sustainable. They must go beyond reducing environmental damage and preventing pollution by finding innovative systems to produce, reuse, and exploit materials and products. For instance,

H&M, while not traditionally considered a luxury brand, has introduced the ‘Conscious Collection’ to provide sustainable fashion options at affordable prices. The marketing for this collection targets consumers seeking both affordability and sustainability in their fashion choices. – Whiting (Citation2019)

Prada’s ‘Re-Nylon’ Project, with its focus on recycling ocean plastics to produce sustainable nylon products, is a pivotal driver of economic value within their marketing strategy. Prada’s campaigns emphasize the intersection of environmental responsibility and innovation, showcasing how sustainability can contribute to both brand success and economic prosperity in the luxury fashion industry. – Indvik (Citation2016)

Measuring the impact of their environmental and social footprint is also essential. The most critical economic challenge facing the luxury fashion industry is to engage in the circular economy, which involves recycling and reusing materials in a closed-loop system. Luxury firms can manufacture without polluting by becoming eco-efficient and contributing to a more sustainable future. In conclusion, luxury fashion companies must navigate social, environmental, and economic sustainability challenges, as exemplified by industry leaders like LVMH, Gucci, and Burberry, while fostering innovation and responsible practices to ensure a sustainable and prosperous future.

3. Existing theories

Fusion of the Schwartz Value Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior

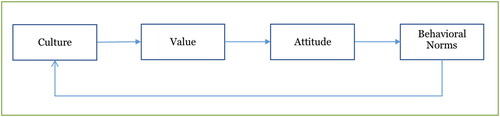

Schwartz’s value theory is used for research on attitude and behavior with a preference for individuals’ or groups’ underlying ideals (Kaur & Arora, Citation2019; Pai et al., Citation2022). The theory focuses on understanding the impact of values on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors surrounding the consumption of sustainable luxury products as exhibited in . The foremost challenge people confront balancing their self-interest and pro-social and pro-environmental ambitions. Their dynamic structure motivates them with these dilemmas (person-focus versus social-focus).

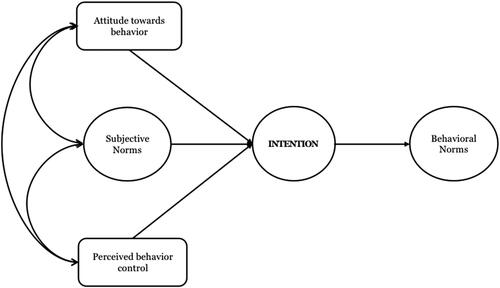

Another theoretical framework employed in this study is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) proposed by Ajzen (Citation1991), which integrates societal ideals and personal values into various consumer behavior studies (Jain et al., Citation2017; Simanjuntak & Putra, Citation2021). TPB was developed to enhance the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and address its limitations (Ajzen, Citation1991; Kumar et al., Citation2022). According to TPB, people’s attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) all contribute to their behavioral intention and subsequent behavior, as exhibited in . Scholars have utilized TPB to investigate the relationship between ethical ideals and behavioral motivations (Brandão & Da Costa, Citation2021). Environmental awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and purchasing intentions have been examined in studies exploring the influence of ethical and materialistic values on consumers’ willingness to purchase counterfeit items (Kaur et al., Citation2021).

Figure 2. Theory of planned behavior.

Source: Ajzen (Citation1991, p. 182).

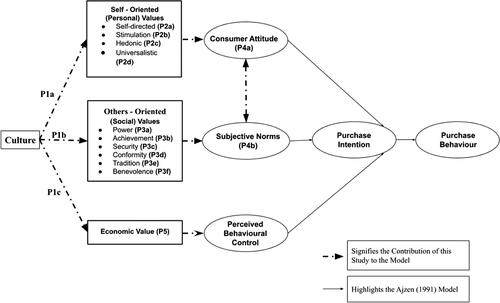

This research relies on a combined theoretical framework comprising the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Schwartz’s value theory. These frameworks are employed to explore the correlation between Schwartz’s values (self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence, and universalism) and the components of TPB in the context of sustainable luxury fashion goods. The TPB provides a foundation for examining various constructs to elucidate consumer behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Building on existing literature, this study expands the TPB model to integrate cultural and Schwartz’s values dimensions within the facets of sustainable luxury, exhibited in .

Figure 3. Conceptual integration of theory of planned behavior and schwartz value theory.

Source: Author (s) work.

Furthermore, a positive correlation has been identified between attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and consumers’ inclination to purchase luxury goods (Youn et al., Citation2021). Customers’ perceptions of the brand, subjective norms, attitudes toward advertisements, engagement in eco-fashion, and environmental concern have been identified as antecedents to the intention to purchase environmentally conscious clothing brands (Su & Tong, Citation2020). McNeill and Moore (Citation2015) established a strong relationship between one’s fashion perspective, peer pressure, and understanding of sustainable fashion when examining the link between attitude and behavior. The past research exclusively believes luxury’s economic and reputational aspects and fails to apprehend luxury purchases’ as the more individualized, subjective, and argumentative characters (Jain et al., Citation2017; Wallace et al. Citation2020). The strategies for sustainable-luxury marketing are yet largely undetermined, and a precise definition of sustainable luxury is indeed elusive. The prospect of different and conflicting viewpoints has increased as the luxury environment changes over time.

4. Determinants influencing the intention to purchase sustainable luxury

The factors impacting the intention to purchase sustainable luxury; four significant categories may be used to group various aspects of sustainable luxury buying intention, including culture, self-oriented (personal) ideals, others-oriented (social) ideals, and economic benefit as exhibited in the .

4.1. Culture

Culture plays a significant influence on an individual’s behavior as evidenced by Jain (Citation2019). In numerous studies, culture has emerged as a pivotal factor in elucidating consumer purchasing patterns for sustainable products. portrays the profound cultural influence on values, attitudes, and behaviors. Numerous studies have consistently highlighted the ‘individualism/collectivism’ dimension as the primary cultural factor for understanding variations in consumer behavior across different nations. According to Czarnecka and Schivinski (Citation2021), individuals with higher collectivism scores are more inclined to support sustainable business practices and attribute different values to recycling activities. This finding suggests that people from collectivistic cultures prioritize community-oriented behaviors and are more likely to invest in products that benefit their community (Rehman, Citation2021). In collectivist societies, group achievements, pro-social principles, and collective advantages hold greater significance compared to individual rewards. The preservation of the environment is seen as a means to advance society as a whole (Diddi & Niehm, Citation2017). On the other hand, individualistic cultures tend to exhibit an ego-centric value orientation, motivating individuals to preserve the environment based on personal interests (Amatulli et al., Citation2017). Some studies have classified certain cultures as ‘ego-centered’ while others as ‘eco-centered’ (Henninger et al., Citation2016). For example, consumers influenced by French and Italian cultures may exhibit a desire to showcase their environmental awareness as a means of self-expression and social status. They buy eco-friendly luxury goods to be recognised by society as conscious buyers. In other cultures, the primary drivers of sustainable luxury spending are economic values, including superior quality, high end fashion brands, premium price and individual values, including hedonism, greater quality, health, and well-being (McCormick & Ram, Citation2022; Henninger et al., Citation2016). In light of the existing literature, the following propositions are made:

P1a: There is a considerable correlation between consumer culture and self-oriented (personal) ideals when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

P1b: There is a considerable correlation between consumer culture and others-oriented (social) ideals when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

P1c: There is a considerable correlation between consumer culture and economic values when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

4.2. Self-oriented (personal) ideals

Sustainability value centred on oneself is linked to consumer personality (Hennigs et al., Citation2013; Hyun & Ko, Citation2017). Consumers who prioritize themselves emphasise the inner self since they are more self-aware in private than in public. These customers strongly emphasise hedonistic, practical, and self-expression ideals (Jain & Mishra, Citation2020). According to Belk (1988), an individual’s personality and belongings appear to be associated with and a critical component of luxury consumer behavior. In recent years, the relevance of sustainability value has grown in consumers’ purchasing choices (Saraswati & Wirayudha, Citation2022). High-end consumers choose brands that should represent their worries and ambitions for a better future (Lou et al., Citation2022). They demand that luxury firms pay attention to moral concerns surrounding the purchase of luxury goods and provide substantial responses to problems of environmental and social responsibility (McCormick & Ram, Citation2022). Luxury brands with a reputation for sustainability are viewed as value enablers by conscious consumers as contrasted to vanity (Kale & Öztürk, Citation2016). Recently, luxury buyers have shifted from being ‘self-oriented’ to being ‘sustainable-oriented’ (Jain et al., Citation2017). The link between individual ideals and sustainability has been examined by several researchers (Chi et al., Citation2021; Tilley & Young, Citation2006). The present research delivers the self-oriented ideals listed below as the preliminary driving powers behind customers’ adoption of sustainable luxury goods:

4.2.1. Self-directed ideals

The literature also exhibits that self-orientation, in addition to social orientation, is a significant driving force behind purchasing luxury goods (Atkinson & Kang, Citation2021). The research indicates that the factors that precede self-orientation toward the consumption of luxury brands include self-directed gratification, self-gift giving, congruity with the inner self, and quality assurance. Research in a western setting has revealed that the primary drivers behind purchasing luxury items are personal objectives like self-directed pleasure and perfectionism (Chi et al., Citation2021; Park & Ahn, Citation2021). According to Shukla et al. (Citation2022), many consumers purchase luxury goods for their own self-directed needs rather than for display. Such consumers have recently shown a greater interest in responsible consumption (Wang et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the following proposition is made in light of the above-cited literature:

P2a: There is a considerable correlation between Self-directed ideals and customers’ attitudes when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

4.2.2. Stimulation potential

Consumers who view fashion as crucial to their sense of self and seek constant ‘newness’ in fashion are not likely to purchase sustainable clothing (McNeill & Moore, Citation2015). They care primarily about the product’s cost and aesthetics than about how it will affect the environment (Sun et al., Citation2022). However, few studies show that luxury customers who want to feel happy and not guilty when purchasing a luxury brand are stimulated by sustainable consumption (Agapie & Sîrbu, Citation2020; Eastman et al., Citation2021; Teona et al., Citation2020). They invest in their health and well-being to find value beyond the product (Hashmi, Citation2017). In light of the preceding literature, the following proposition is made:

P2b: A considerable correlation exists between consumers’ stimulation potential and attitudes when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

4.2.3. Hedonic value

The hedonic value is crucial to the perceived usefulness obtained from luxury things (Ekawati et al., Citation2021). Hedonistic consumers want to express themselves and are ready to pay a premium for luxury goods. Wang et al. (Citation2018) stressed that hedonic experiences, particularly in personal motives for luxury purchasing, are fueled by positive emotions like feeling good or happy. However, according to Cervellon and Shammas (Citation2013), luxury comes with a psychological price that they classify as ‘guilty pleasures’ that could cause unhappy feelings following the purchase. To enjoy themselves ‘guilt-free’, an increasing number of consumers are purchasing sustainable luxury goods. According to a study by Ki and Kim (Citation2016), sustainable luxury purchases have a more emotional impact on luxury customers than standard ostentatious luxury purchases. Emphasis is positioned on ‘valuing and knowing the object’ in a sustainable fashion (Bae & Jeon, Citation2022). It strongly emphasises providing customers with unforgettable experiences by educating them about the complete sustainable value chain that an ethical product travel through. A hedonic consumer’s value system is ingrained with ethical consumption (Manchiraju & Sadachar, Citation2014). Therefore, the following proposition is developed in light of the previous studies:

P2c: A considerable correlation exists between consumers’ hedonic value and attitudes when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

4.2.4. Universalistic ideals

Ideals that promote understanding, tolerance, appreciation, compassion, and preservation for all individuals and the environment welfare are referred to as universalistic (Jain & Mishra, Citation2020). Millennials hope to justify their expensive purchases by promoting societal progress (Dabas & Whang, Citation2022). The definition of luxury has changed from ‘material’ to ‘immaterial’ in many societies (Hashmi, Citation2017). Among the new generation of fashion buyers, luxury businesses that ‘concurrently respect craftspeople and the environment’ foster more profound pro-sustainability ideals (Park & Ahn, Citation2021). Individuals’ perspectives on social and environmental issues are influenced by universalistic ideals (Ramasamy et al., Citation2020). Numerous researchers in several fields have found a strong link between responsibility towards society and the environment and universalistic beliefs (Eastman et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the following proposition is developed:

P2d: A considerable correlation exists between consumers’ universalistic values and attitudes when buying sustainable luxury fashion items.

4.3. Others-oriented (social) ideals

For decades, luxury has been employed to represent the social self. The urge to ‘buy to impress others’ was once thought to be the primary driver behind purchasing luxury goods (Dubois et al., Citation2021). According to Jain (Citation2019), the main factor influencing the consumption of luxury items is vulnerability to the peer-group effect. Ramchandani and Coste-Manière (Citation2012) described the consumption of sustainable luxury goods in public as philanthropic and pro-environmental behavior. However, they also suggested that this behavior might hold for developing nations like India and China, where conspicuity, imitation, and word-of-mouth significantly impact the luxury product market.

Likewise, Cervellon and Carey (Citation2011) discovered that sustainable consumption has become a new type of conspicuous consumption in some societies. According to Casadei and Lee (Citation2020), individuals are now spending money on ‘green to be seen’ as opposed to in previous eras when they would spend money to exhibit their wealth (Kapferer & Michaut-Denizeau, Citation2020). In essence, showing one’s concern for the environment is fashionable right now. Sustainable goods enable people to be recognized for their social contributions (Cervellon & Shammas, Citation2013). Subjective standards exert social pressure on people to act in an environmentally responsible way (Legere and Kang, Citation2020). Luxurious consumption transforms from a showy effort into an intellectual pursuit when aspiration is refocused from affiliation with a thing to association with a purpose. According to Kapferer & Michaut-Denizeau (Citation2020), as psychological complexity increased, people became more concerned about others and the environment than themselves (Agapie & Sîrbu, Citation2020). According to a thorough analysis of the literature, this study identifies the following values as the main driving forces behind consumers’ adoption of sustainable luxury goods.

4.3.1. Power

According to earlier studies, buying luxury goods is a highly communicative activity. Consumers purchase luxuries to display their positions, wealth, class, and economic and social power (Aw et al., Citation2021). Koo and Im (Citation2017) investigated how the consumption of luxuries offered a code that assisted people in communicating their positions and power to attract attention and favor from society. Power is the ability to influence people while resisting external pressure to submit to influence (Rehman, Citation2021). Few studies have shown that influential people have a greater desire to resist external normative influence, which raises the risk that they may act socially unacceptable (Kim and Oh, Citation2020). Individuals who indulge in luxury to enhance their status and influence may thus transgress social norms related to moral and ecological consumption (Beckham & Voyer, Citation2014). According to several studies, adopting eco-friendly fashion brands by well-known luxury consumers can inspire others to embrace pro-environmental and pro-social behaviors (Khandual and Pradhan, Citation2019; Kumar et al. Citation2022). Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed in light of the earlier works:

P3a: A significant relationship exists between subjective norms and power regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

4.3.2. Achievement

Conspicuous consumerism is consuming luxury items publicly to flaunt money, success, and status (Bian & Forsythe, Citation2012). When it comes to gender, men buy luxury goods predominantly to show off their degree of achievement and competence in the workplace. However, the primary motivators for women are quality, individuality, and social value (Pavione et al., Citation2016). According to Su and Tong’s (Citation2020) research, peer pressure is especially prevalent among young individuals who frequently seek the attention and prestige of expensive products. Consumer interest in sustainable or environmentally friendly products has recently increased (Kim et al., Citation2015; Maloney et al., Citation2014). They are willing to spend a premium for sustainable luxury designed to promote their prosperity and economic performance in society (Athwal et al., Citation2019). The distinctive quality of a product is represented by its sustainability. Going green or eco-friendly to be noticed in society or sustainability enhances a user’s societal standing, according to Khandual and Pradhan (Citation2019). In light of the earlier research, the following hypothesis is developed:

P3b: A significant relationship exists between subjective norms and achievement regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

4.3.3. Security

Bekimbetova et al. (Citation2021) assert that people’s surroundings and interactions with others in their reference group greatly influence and govern their behavior. Dubois et al. (Citation2021) argues that preserving one’s looks and purchasing upscale items are interconnected. He thought that one way to show respect and appreciation to one’s family and the greater community was to display the visible results of one’s achievements and success. Primarily, East Asian consumers engage in luxury spending and other perceived means of maintaining social standing and sustaining good relationships in society and across communities (Han et al., Citation2017; Rehman, Citation2021). People who identify as ‘social’ feel comfortable spending money on luxury items that are ‘sustainable’, ‘organic’, and ‘ethical’ as sustainability becomes the new big thing (Bekimbetova et al., Citation2021). In light of the preceding studies, the proposition that follows is developed:

P3c: A significant relationship exists between subjective norms and security regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

4.3.4. Conformity

Social value is defined as a person’s desire to acquire expensive items representing adherence to the group (Amatulli et al., Citation2017). The opinions of others exert a significant impact on individuals who consider themselves to be ‘social’. In comparison, the cost has a more negligible influence on their buying decision. They are influenced by cultural norms and peer pressure to engage in sustainable fashion purchases (McNeill & Moore, Citation2015). Sustainable fashion consumers are influenced by many desired outcomes, including aesthetic fulfilment, self-expression, and group dynamics (Agapie & Sîrbu, Citation2020). Thus, the following proposition is proposed:

P3d: A significant relationship exists between subjective norms and conformance regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

4.3.5. Tradition

Countries differ in terms of their cultures and customs, and as a result, the sustainability strategies used in various countries vary greatly (Dubois et al., Citation2021). Sustainable luxury promotes the resurgence of luxury’s original meaning, emphasising regional customs and craftsmanship, the know-how of old customs and traditions. Sustainable luxury supports local artisans and craftsmanship in multiple ways (Kale & Öztürk, Citation2016). Numerous luxury brands participate in social and environmental activities to support a more significant cause. For instance, Louis Vuitton bases its social responsibility on four guiding principles: eliminating discrimination, fostering local traditions, improving talent development and working conditions, and workplace well-being. Thus, based on the given literature, the following hypothesis is proposed:

P3e: A significant relationship exists between subjective norms and tradition regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

4.3.6. Benevolence

When it comes to protecting and increasing the well-being of individuals with whom one is in frequent intimate contact, one is said to have benevolent principles (Ramasamy et al., Citation2020). Consumers make ethical decisions because of benevolent principles, which prioritize the well-being of others over one’s own. Benevolent values are evaluated based on the importance that a person attaches or assigns to elements like kinship, nobility, and sincere relationships (Diddi & Niehm, Citation2017). It was discovered that benevolent principles were essential for consumers in countries like the US to purchase fair trade goods. Consumers who prioritize altruistic principles are more likely to be swayed by essential people in society and their personal lives (Diddi & Niehm, Citation2017). Few wealthy customers are rethinking and rearranging their priorities to make their fashion purchases less obvious and more sensitive towards society and the environment (Bhardwaj & Bedford, Citation2017; Teona et al. Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). Few pro-environment consumer studies (Bae & Jeon, Citation2022) also believed that a small percentage of wealthy customers make purchases out of an obligation to uphold moral principles rather than selfish interests (Agapie & Sîrbu, Citation2020). Due to consumers’ move from ‘conspicuous value’ to ‘conscientious value’, luxury brand marketers recently altered their business models to focus on sustainability (Wang et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the following proposition is developed:

P3f: A significant relationship exists between subjective norms and goodness regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

4.4. Economic value

Customer attitudes are central to this study, defined as individuals’ overall evaluation of a product or service, influenced by their beliefs, feelings, and behavioral intentions (McNeill & Moore, Citation2015). In this research, we employ the Theory of Reasoned Action to understand how these factors influence customer attitudes. Researchers should consider the significant relationship between subjective norms and attitudes while evaluating reasoned behavior theory. Jain (Citation2019) states that norms prescribe not only perceptions and attitude but also behavior. Jain and Mishra (Citation2020) suggested that normative and attitudinal variables might be interrelated and provided crucial support for these findings. There has not been much research in the domain that shows how subjective norms can affect attitude (Saraswati & Wirayudha, Citation2022). According to Chi et al. (Citation2021), social influences and the formation of attitudes are not independent processes. According to Ekawati et al. (Citation2021), customers’ attitudes about sustainability in the fashion products they buy are influenced by their concern for the well-being of society and the environment. Therefore, the following proposition is made based on the given arguments:

P4a/P4b: Subjective norms (P4a) and attitudes (P4b) have a huge impact on consumer decisions to purchase sustainable luxury fashion products.

P5: A significant relationship exists between perceived behavioral control and economic value regarding customers’ purchases of sustainable luxury fashion products.

5. Discussion and implications

The main objective of this study is to comprehend customers’ attitudes and intentions towards purchasing sustainable luxury products and the associated marketing strategies. The study categorizes sustainable luxury consumption into two dimensions: personal (self-oriented) and social (others-oriented) ideals. This study holds significance for both managerial and theoretical domain. This study begins by presenting a comprehensive and systematic exploration of the personal and social ideals influencing consumers’ decisions to acquire sustainable luxury goods. It elucidates how individuals may have distinct motivations for choosing sustainable luxury items. While the influence of significant others may guide some consumers, others make purchasing decisions based on their own preferences (Eastman et al., Citation2021). Therefore, marketers should have a realistic understanding of these dynamics and develop communication strategies accordingly.

Following this, the study concentrates on an integrated conceptual model that offers a holistic perspective and comprehension of the factors that shape customers’ attitudes towards the intention of buying sustainable luxury products, drawing upon the existing literature. The buying intention is influenced by four key factors: culture, personal values (self-oriented), social ideals (others-oriented), and economic factors (Han et al., Citation2017). The conceptual framework delineates the impact of culture on both personal (self-oriented) values and social (others-oriented) values concerning the acquisition of luxury goods (Legere & Kang, Citation2020). Self-oriented values encompass aspects such as self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, and universalism. On the other hand, others-oriented values include power, achievement, security, conformity, tradition, and benevolence. Economic value signifies consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for sustainable luxury goods. This study endeavor to integrate the cultural and Schwartz value dimensions into Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The goal is to present a behavioral framework that enhances our understanding, analysis, and explanation of consumer purchasing behavior for sustainable luxury fashion goods (Park & Ahn, Citation2021).

The current research aims to present a behavioral framework that assists in understanding, analyzing, and explaining consumers’ purchasing behavior in the context of sustainable luxury fashion consumption. Furthermore, it seeks to integrate the cultural component with Schwartz’s value dimensions and Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior, as highlighted by Pai et al. (Citation2022). Lastly, by comprehending the factors influencing the purchase of sustainable luxury goods, luxury brand managers can adapt their marketing strategies and enhance their companies’ brand value. Sustainable luxury enterprises can attract, involve, engage, and retain customers by crafting marketing strategies aligned with consumers’ beliefs and motivations surrounding sustainable purchasing behavior, as proposed by Legere and Kang (Citation2020).

The study endeavors to assist marketers in comprehending how individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds perceive the purchase of sustainable products—a perception that may significantly differ. Existing literature confirms that in socialist cultures, ‘anthropocentric value orientation’ governs environmental protection, whereas in individualistic societies, ‘egocentric value orientation’ prevails (Amatulli et al., Citation2017). These findings underscore the crucial importance of developing country-specific marketing strategies for sustainable products while considering cultural norms within society.

6. Conclusion, limitations and scope for future research

This study has illuminated the valuable insights into consumer attitudes and intentions towards sustainable luxury products and marketing strategies. Our research categorized sustainable luxury consumption into personal and social ideals, offering valuable insights into consumers’ motivations. Culture, personal values, social ideals, and economic factors collectively influence intentions to buy sustainable luxury products, as depicted in our integrated model. Notably, culture plays a pivotal role in shaping ideals associated with luxury consumption (Indvik, Citation2016).

In examining our claims, this study did not distinguish between social, economic (such as labour rights and community development), and environmental (such as resource exploitation) sustainability. Instead, our focus encompassed sustainability as a broad, overarching concept. While this choice aligns with previous studies, particularly those by Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau in 2017 and 2020, which similarly considered sustainability in a generalized framework to test their hypotheses, it may curtail the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, our research concentrated specifically on the sustainable luxury fashion market. Expanding the scope to include other luxury sectors such as food, travel, housing, automobiles, among others, could offer a more comprehensive understanding of consumer behavior. Exploring additional factors that influence luxury consumer behavior, including beliefs, moral standards, and ethics, could provide valuable insights into their impact on attitudes, intentions, and purchasing behaviors related to sustainable luxury items.

In terms of future research directions, there is an opportunity to investigate the influence of demographic variables such as age, income, gender, and education on consumers’ decisions to purchase sustainable luxury goods. To further strengthen the proposed framework, future research should prioritize reinforcing its theoretical foundations and addressing the propositions’ bases. This involves a more in-depth exploration of existing theories or the development of new frameworks that align with the complexities of the luxury fashion industry. Additionally, empirical studies, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methods, play a crucial role in validating the proposed relationships and providing practical insights. Moreover, a longitudinal study could be undertaken to unravel how shifts in cultural dynamics over time impact the moral behavior of luxury consumers. These considerations underscore the need for a more nuanced and expansive exploration of the multifaceted aspects influencing consumer choices in sustainable luxury.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Harpreet Kaur

Harpreet Kaur is an assistant professor at CHRIST (Deemed to be University) within the School of Commerce, Finance, and Accountancy. Her research expertise lies in the domain of services marketing, consumer behaviour, luxury fashion marketing, and cross-cultural studies. Her scholarly pursuits primarily delve into topics such as customer retention, service selection parameters, and model development. Dr. Kaur has contributed significantly to her field, and her work has been published in numerous top marketing journals, such as International Journal of Bank Marketing, Journal of Financial Services Marketing, etc.

Shruti Choudhary

Shruti Choudhary is an undergraduate student currently pursuing her Bachelor in Business Administration (BBA) with a focus on finance and accountancy at CHRIST (Deemed to be University) within the School of Commerce, Finance, and Accountancy.

Adarsh Manoj

Adarsh Manoj is an undergraduate student pursuing his Bachelor of Commerce (B. Com) degree at CHRIST (Deemed to be University) within the School of Commerce, Finance, and Accountancy.

Muskan Tyagi

Muskan Tyagi is an undergraduate student currently pursuing her Bachelor in Business Administration (BBA) with a focus on finance and accountancy at CHRIST (Deemed to be University) within the School of Commerce, Finance, and Accountancy.

References

- Agapie, A. R., & Sîrbu, G. (2020). Young consumers demand sustainable and social responsible luxury. Directory of Open Access Journals). https://doaj.org/article/9353452980284aad9f4e7ce6ba3a08d2

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., & Donato, C. (2021). The atypicality of sustainable luxury products. Psychology & Marketing, 38(11), 1990–2005. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21559

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Peluso, A. M., & Guido, G. (2021). Recycled luxury: Consumer responses to luxury products made from recycled materials. Journal of Business Research, 128, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.019

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Pino, G., & Guido, G. (2017). Unsustainable luxury and negative word-of-mouth: The role of shame and consumers’ cultural orientation. Advances in Consumer Research, 45, 1–10. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v45/acr_vol45_1023733.pdf

- Angevine, C., Keomany, J., Thomsen, J., & Zemmel, R. (2021). Implementing a digital transformation at industrial companies. McKinsey & Company.

- Athwal, N., Wells, V. K., Carrigan, M., & Henninger, C. E. (2019). Sustainable luxury marketing: A synthesis and research Agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(4), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12195

- Atkinson, S. A., & Kang, J. (2021). New luxury: Defining and evaluating emerging luxury trends through the lenses of consumption and personal values. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(3), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2020-3121

- Aw, E. C., Chuah, S. H., Sabri, M. F., & Basha, N. K. (2021). Go loud or go home? How power distance belief influences the effect of brand prominence on luxury goods purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102288

- Bae, J., & Jeon, H. G. (2022). Exploring the relationships among brand experience, perceived product quality, hedonic value, utilitarian value, and brand loyalty in unmanned coffee shops during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 14(18), 11713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811713

- Beckham, D., & Voyer, B. G. (2014). Can sustainability be luxurious? A mixed-method investigation of implicit and explicit attitudes towards sustainable luxury consumption. ACR North American Advances. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v42/acr_v42_17922.pdf.

- Bekimbetova, G. M., Erkinov, S. B., & Rakhimov, U. F. (2021). Culture and its influence on consumer behavior in the context of marketing (in case of “Coca-Cola” company). Deutsche Internationale Zeitschrift Für Zeitgenössische Wissenschaft, 2021(7-2), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.24412/2701-8369-2021-7-2-4-6

- Belk. (1998). The double nature of collecting: materialism and anti-materialism. Stichting Etnofoor, Jstor, 11(1), 25757924.

- Bhardwaj, V., & Bedford, S. C. (2017). (Not) Made in Italy: Can sustainability and luxury co-exist? In: Gardetti, M. (eds.), Sustainable Management of Luxury. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes, 411–426. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2917-2_19

- Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.010

- Böcker, L., & Meelen, T. (2017). Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.004

- Brandão, A., & Da Costa, A. M. R. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behaviour to understand the effects of barriers towards sustainable fashion consumption. European Business Review, 33(5), 742–774. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2020-0306

- Brosseau, D., Ebrahim, S., Handscomb, C., & Thaker, S. (2019). The journey to an agile organization. McKinsey & Company.

- Brundtland Commission. World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our Common Future.

- Casadei, P., & Lee, N. (2020). Global cities, creative industries and their representation on social media: A micro-data analysis of Twitter data on the fashion industry. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(6), 1195–1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20901585

- Cervellon, M., & Carey, L. (2011). Consumers’ perceptions of “green”: Why and how consumers use eco-fashion and green beauty products. Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty, 2(1), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.2.1-2.117_1

- Cervellon, M., & Shammas, L. (2013). The value of sustainable luxury in mature markets: A customer-based approach. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2013(52), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2013.de.00009

- Chi, T., Ganak, J., Summers, L., Adesanya, O., McCoy, L., Liu, H., & Tai, Y. (2021). Understanding perceived value and purchase Intention toward Eco-Friendly Athleisure Apparel: Insights from U.S. Millennials. Sustainability, 13(14), 7946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147946

- Czarnecka, B., & Schivinski, B. (2021). Individualism/collectivism and perceived consumer effectiveness: The moderating role of global–local identities in a post-transitional European economy. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 21(2), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1988

- Dabas, C. S., & Whang, C. H. (2022). A systematic review of drivers of sustainable fashion consumption: 25 years of research evolution. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 13(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2021.2016063

- Diddi, S., & Niehm, L. S. (2017). Exploring the role of values and norms towards consumers’ intentions to patronize retail apparel brands engaged in corporate social responsibility (CSR). Fashion and Textiles, 4(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-017-0086-0

- Dubois, D., Jung, S., & Ordabayeva, N. (2021). The psychology of luxury consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology, 39, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.011

- Eastman, J. K., Iyer, R., & Dekhili, S. (2021). Can luxury attitudes impact sustainability? The role of desire for unique products, culture, and brand self-congruence. Psychology & Marketing, 38(11), 1881–1894. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21546

- Ekawati, N. W., Yasa, N. N. K., Kusumadewi, N., & Setini, M. (2021). The effect of hedonic value, brand personality appeal, and attitude towards behavioral intention. Management Science Letters, 2021, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.8.008

- Franco, J., Hussain, D., & McColl, R. (2019). Luxury fashion and sustainability: Looking good together. Journal of Business Strategy, 41(4), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-05-2019-0089

- Han, J., Seo, Y., & Ko, E. (2017). Staging luxury experiences for understanding sustainable fashion consumption: A balance theory application. Journal of Business Research, 74, 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.029

- Hansen, A., Nielsen, K. B., & Wilhite, H. (2016). Staying cool, looking good, moving around: Consumption, sustainability and the ‘rise of the south. In Forum for Development Studies (Vol. 43, No. 1, pp.5–25). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2015.1134640

- Hashmi, K. (2017). Millennials, luxury consumption and sustainability: An exploratory study. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management. An International Journal, 21(3), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-09-2016-0073

- Hendriksz, V. (2018, June 5) Gucci unveils Gucci Equilibrium as it strengthens its sustainability strategy. Fashion United. https://fashionunited.uk/news/fashion/gucci-unveils-gucci-equilibrium-as-it-strengthens-its-sustainability-strategy/2018060530038.

- Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K., Klarmann, C., & Behrens, S. (2013). Sustainability as part of the luxury essence: Delivering value through social and environmental excellence. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2013(52), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2013.de.00005

- Henninger, C. E., Alevizou, P. J., & Oates, C. (2016). What is sustainable fashion? Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(4), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2015-0052

- Hepner, J., Chandon, J., & Bakardzhieva, D. (2020). Competitive advantage from marketing the SDGs: A luxury perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(2), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-07-2018-0298

- Hyun, M. K., & Ko, E. (2017). Why do consumers choose sustainable fashion? A cross-cultural study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 8(3), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2017.1336458

- Indvik, L. (2016). Why is it taking fashion so long to get on board with sustainability. V Fashionista.

- Jain, S. (2019). Factors affecting sustainable luxury purchase behavior: A conceptual framework. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 31(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2018.1498758

- Jain, S., & Mishra, S. (2020). Luxury fashion consumption in sharing economy: A study of Indian millennials. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 11(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2019.1709097

- Jain, S., Khan, M. Z. A., & Mishra, S. (2017). Understanding consumer behavior regarding luxury fashion goods in India based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 11(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-08-2015-0118

- Janssen, C., Vanhamme, J., Lindgreen, A., & Lefebvre, C. (2014). The catch-22 of responsible luxury: Effects of luxury product characteristics on consumers’ perception of fit with corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1621-6

- Johnstone, M., & Tan, L. P. (2015). An exploration of environmentally-conscious consumers and the reasons why they do not buy green products. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(5), 804–825. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2013-0159

- Kale, G. Ö., & Öztürk, G. (2016). The importance of sustainability in luxury brand management. Intermedia International e-Journal, 1(3), 106–106. https://doi.org/10.21645/intermedia.2016319251

- Kapferer, J., & Laurent, G. (2016). Where do consumers think luxury begins? A study of perceived minimum price for 21 luxury goods in 7 countries. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.005

- Kapferer, J., & Michaut-Denizeau, A. (2014). Is luxury compatible with sustainability? Luxury consumers’ viewpoint. Journal of Brand Management, 21(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2013.19

- Kapferer, J., & Michaut-Denizeau, A. (2020). Are millennials really more sensitive to sustainable luxury? A cross-generational international comparison of sustainability consciousness when buying luxury. Journal of Brand Management, 27(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-019-00165-7

- Kapferer, J., & Valette-Florence, P. (2022). The myth of the universal millennial: Comparing millennials’ perceptions of luxury across six countries. International Marketing Review, 39(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-04-2021-0155

- Kapferer, J. N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2018). Luxury brand strategy and brand extension: The perpetual paradox. Journal of Brand Management, 25(5), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0062-2

- Kapferer, J. N., Michaut, A., Gardetti, M. A., & Torres, A. L. (2014). Are luxury consumers really insensitive to sustainable development and why? In Sustainable Luxury: Managing Social and Environmental Performance in Iconic Brands (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351287807.

- Kaur, H., & Arora, S. (2019). Demographic influences on consumer decisions in the banking sector: Evidence from India. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 24(3-4), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-019-00067-4

- Kaur, J., Parida, R., Ghosh, S., & Lavuri, R. (2021). Impact of materialism on purchase intention of sustainable luxury goods: An empirical study in India. Society and Business Review, 17(1), 22–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-10-2020-0130

- Kerr, J., & Landry, J. (2017). Pulse of the fashion industry – Global fashion agenda.

- Khandual, A., & Pradhan, S. (2019). Fashion brands and consumers approach towards sustainable fashion. In Textile science and clothing technology (pp. 37–54). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1268-7_3

- Ki, C., & Kim, Y. (2016). Sustainable versus conspicuous luxury fashion purchase: Applying self-determination theory. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 44(3), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12147

- Kim, J., Taylor, C. R., Kim, K. H., & Lee, K. H. (2015). Measures of perceived sustainability. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 25(2), 182–193.

- Kim, Y., & Oh, K. W. (2020). Which consumer associations can build a sustainable fashion brand image? Evidence from fast fashion brands. Sustainability, 12(5), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051703

- Kong, H. M., Ko, E., Chae, H., & Mattila, P. (2016). Understanding fashion consumers’ attitude and behavioral intention toward sustainable fashion products: Focus on sustainable knowledge sources and knowledge types. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 7(2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2015.1131435

- Kong, H. M., Witmaier, A., & Ko, E. (2021). Sustainability and social media communication: How consumers respond to marketing efforts of luxury and non-luxury fashion brands. Journal of Business Research, 131, 640–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.021

- Koo, J., & Im, H. (2017). Going up or down? Effects of power deprivation on luxury consumption. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.017

- Kumar, N., Garg, P., & Singh, S. (2022). Pro-environmental purchase intention towards eco-friendly apparel: Augmenting the theory of planned behavior with perceived consumer effectiveness and environmental concern. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 13(2), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2021.2016062

- Legere, A., & Kang, J. (2020). The role of self-concept in shaping sustainable consumption: A model of slow fashion. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120699

- Li, J., & Leonas, K. K. (2019). Trends of sustainable development among luxury industry. In Environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes (pp. 107–126). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0623-5_6

- Lou, X., Chi, T., Janke, J., & Desch, G. (2022). How do perceived value and risk affect purchase intention toward second-hand luxury goods? An empirical study of U.S. Consumers. Sustainability, 14(18), 11730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811730

- Maloney, J., Lee, M. Y., Jackson, V., & Miller-Spillman, K. A. (2014). Consumer willingness to purchase organic products: Application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 5(4), 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2014.925327

- Manchiraju, S., & Sadachar, A. (2014). Personal values and ethical fashion consumption. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 18(3), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-02-2013-0013

- McCormick, H., & Ram, P. (2022). ‘Take a Stand’: The importance of social sustainability and its effect on Generation Z Consumption of Luxury Fashion Brands. Springer eBooks, 2022, 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06928-4_11

- McNeill, L. C., & Moore, R. (2015). Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12169

- Pai, C., Laverie, D., & Hass, A. (2022). Love luxury, love the earth: An empirical investigation on how sustainable luxury consumption contributes to social-environmental well-being. Journal of Macromarketing, 42(4), 640–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/02761467221125915

- Park, J., & Ahn, J. (2021). Editorial introduction: Luxury services focusing on marketing and management. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102257

- Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R., & Dall, M. (2016). Emerging competitive strategies in the global luxury industry in the perspective of sustainable development: The case of Kering group. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy Journal, 4(2), 241–261.

- Ramasamy, S., Singh, K. S. D., Amran, A., & Nejati, M. (2020). Linking human values to consumerCSRperception: The moderating role of consumer skepticism. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1958–1971. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1939

- Ramchandani, M., & Coste-Manière, I. (2012). Asymmetry in multi-cultural luxury communication: A comparative analysis on luxury brand communication in India and China. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 3(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2012.10593111

- Rattalino, F. (2018). Circular advantage anyone? Sustainability-driven innovation and circularity at Patagonia, Inc. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(5), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21917

- Rehman, A. U. (2021). Consumers’ perceived value of luxury goods through the lens of Hofstede cultural dimensions: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(4), 660. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2660

- Saraswati & Wirayudha. (2022). Sustainability marketing mix on purchase decision through consumer’s green attitude as the moderating variable. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research (IJEBAR), 6(3), E-ISSN: 2614-1280.

- Shukla, P., Rosendo-Rios, V., & Khalifa, D. (2022). Is luxury democratization impactful? Its moderating effect between value perceptions and consumer purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 139, 782–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.030

- Simanjuntak, M., & Putra, A. H. P. K. (2021). Theoretical implications of theory planned behavior on purchasing decisions: A bibliometric review. Golden Ratio of Mapping Idea and Literature Format, 1(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.52970/grmilf.v1i1.18

- Su, J., & Tong, X. (2020). An empirical study on Chinese adolescents’ fashion involvement. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12564

- Sun, Y., Wang, R. R., Cattaneo, E., & Mlodkowska, B. (2022). What influences the purchase intentions of sustainable luxury among millennials in the UK? Strategic Change, 31(3), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2501

- Teona, G., Ko, E., & Kim, S. H. (2020). Environmental claims in online video advertising: Effects for fast-fashion and luxury brands. International Journal of Advertising, 39(6), 858–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1644144

- Tilley, F., & Young, W. (2006). Sustainability entrepreneurs: Could they be the true wealth generators of the future. ?Greener Management International, 2006(55), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.3062.2006.au.00008

- Wallace, E., Buil, I., & Catalán, S. (2020). Facebook and luxury fashion brands: Self-congruent posts and purchase intentions. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 24(4), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-09-2019-0215

- Wang, C., Zhang, J., Yu, P., & Hu, H. (2018). The theory of planned behavior as a model for understanding tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors: The moderating role of environmental interpretations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 194, 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.171

- Wang, P., Kuah, A. T., Lu, Q., Wong, C., Thirumaran, K., Adegbite, E., & Kendall, W. Y. (2021). The impact of value perceptions on purchase intention of sustainable luxury brands in China and the UK. Journal of Brand Management, 28(3), 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00228-0

- Whiting, T. (2019, June 27) The truth behind the marketing of H&M’s conscious collection. ‘Sustainable Style’. https://tabitha-whiting.medium.com/sustainable-style-the-truth-behind-the-marketing-of-h-ms-conscious-collection-805eb7432002.

- Woodside, A. G., & Fine, M. B. (2019). Sustainable fashion themes in luxury brand storytelling: The sustainability fashion research grid. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 10(2), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2019.1573699

- Youn, S., Lee, J. P., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2021). Fashion consumers’ channel switching behavior during the COVID-19: Protection motivation theory in the extended planned behavior framework. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 39(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X20986521