Abstract

Gender roles have evolved with time; however, males often demonstrate aggressive and risk-prone behaviours. Both genders show different attitudes towards objects and situations due to hormonal differences. Nevertheless, such a relationship is significantly influenced by the perception of the retail mix. It has been argued that women, in particular, are more influenced by the retail mix, shaping their view of a retail brand’s image. Consequently, this study aims to explore women’s perceptions of the retail mix on the retail brand image and examine the mediating role of employee attitudes. A quantitative research approach was used for this study. A purposive sampling technique was used to collect primary data from 287 women who were shopping. Partial Least Square Structural equation modelling was used to analyse the primary data and investigate the relationship among the variables. The study’s findings have revealed a positive relationship between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image and employee attitude and retail brand image. The study revealed that the location and environment of a retail store do not significantly impact consumers’ evaluation of the brand. The study’s findings also indicated that employee attitude fully mediates the connection between retail store location and environment, retail brand image, and the association between retail pricing and retail brand image, but partially mediates the connection between retail stock/brand quality and retail brand image. This study addresses a subject matter that is rarely covered in retail literature: the function of employee attitudes as a mediator between marketing mix and brand image in retail settings, particularly in emerging markets. The study builds on the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory (S-O-R) by providing new insights into a largely unstudied area of retail marketing dynamics. Specifically, it deepens our understanding of how customer perceptions of employee attitudes shape a retail firm’s image and reputation. The findings of this study suggest that retail managers should prioritize effective management of retail stock and product quality as a strategy for competitive advantage. Additionally, it is imperative for them to invest significantly in employee training. This investment is crucial as the study highlights the impact of employees’ attitudes on the perception and reputation of the retail brand. Therefore, fostering positive employee attitudes through comprehensive training programs is essential for enhancing brand perception and gaining a competitive edge in the market.

Subjects:

Introduction

Globally, consumers spend billions of dollars on branded products; hence, branding has been touted by leading marketing academics and practitioners as part of organisations’ most valuable strategic assets (Dwivedi et al., Citation2023; Mundel et al., Citation2018; Qalati et al., Citation2022). Branding helps to attract and retain customers for life. Robust branding of products projects uniqueness, which engenders lasting customer trust and confidence for prompt purchase action (Leung et al., Citation2022; Rashid & Barnes, Citation2021). As such, marketing experts continue to investigate consumer behaviour regarding how retailing underscores the strategic importance of customer experience. Thus, different aspects of branding and its effect on retailing have been researched (De Keyser et al., Citation2020; Grewal et al., Citation2009; Kandampully et al., Citation2018). Pandey and Chawla (Citation2018) and Reinartz et al. (Citation2019) recommend that retailers constantly assess the customer experience of their store or retail mix to inform the development of new retail strategies. The retail mix (service interface, retail atmosphere, variety, and branding) is a variable that retailers can control.

For decades, marketing experts and practitioners have assessed customer brand appreciation by evaluating how brand equity affects the corporate image. The image of a brand is largely associated with a brand’s perceived positive outcome, based on experience and word-of-mouth recommendations (Gonzales-Chávez & Vila-Lopez, Citation2021; Sürücü et al., Citation2019). Brand equity is therefore said to be the degree of confidence consumers associate with brands compared to competing brands, affecting consumer loyalty and willingness to spend on a noted brand (Wei et al., Citation2023). Similarly, Esch et al. (Citation2006) argue that customer-based brand equity occurs when consumers are familiar with and have positive associations with a well-known brand, reflecting in their recognition and perception of the brand. Hence, a positive brand image increases consumers’ trust and confidence to strongly influence perceived brand credibility in most markets, including emerging markets (EMs).

Amidst stagnation in developed markets, organizations are increasingly targeting emerging markets for growth and profitability, aiming to boost shareholder value in the face of global dynamic changes (Sinha & Sheth, Citation2017). Cassia and Magno (Citation2015), and Meyer and Peng (Citation2016) describe EMs as a unique market, signifying a world full of potential. This market is recognised as one of the emerging economies with the fastest rate of growth, giving rise to the highest-growing middle-class to high-class consumers (Paul, Citation2020; Kastner et al., Citation2019). Emerging market and developing economies are projected to have a modest decline in growth from 4.1 percent in 2022 to 4.0 percent in both 2023 and 2024. Emerging market and developing economies are expected to grow by 4% in 2024 (International Monetary Fund, Citation2023).

Retailing, serving as an intermediary function, encompasses the communication and distribution of products, along with the implementation of marketing plans and strategies, all aimed at benefiting the end-users of these products. Building on the understanding of retailing as an intermediary activity, it’s important to note the evolution of gender roles over time. Men often display aggressive and risk-prone behaviours (Herter et al., Citation2014; Roper & Alkhalifah, Citation2021). Adding to this, Asad and Abid (Citation2018), along with Herter et al. (Citation2014), observe that hormonal differences lead to varying attitudes in men and women towards objects and situations. Furthermore, these gender-specific behaviours and attitudes are significantly influenced by perceptions of the retail environment (Herter et al., Citation2014). In sub-Saharan Africa and other EMs, women are traditionally in charge of shopping (Reinartz et al., Citation2011) because they are primarily homemakers who are responsible for the daily upkeep of their families. Women possess the requisite know-how for shopping at traditional local markets and modern stores, including newly established shopping malls in urban communities. Women further consider shopping as an experience rather than a mere purchase (Badewi et al., Citation2023; Herter et al., Citation2014). In line with this perspective, Ghana, a lower-middle-income economy, has seen a surge in the number of shopping malls spread across urban areas over the past two decades, catering to the needs of the middle and upper classes.

Again, even though gender roles are changing gradually worldwide as more women work in the formal sector, their traditional responsibilities, especially in developing countries, have not changed much. Hence, women continue to combine home responsibilities, including shopping, with their jobs. Surprisingly, over the last five years, various academic papers on retailing in Ghana, such as online retailing stores (Jibril et al., Citation2020), airport retailing (Kosiba et al., Citation2020), bank retailing (Blankson et al., Citation2017; Narteh, Citation2018; Omoregie et al., Citation2019; Tweneboah-Koduah & Farley, Citation2015), petroleum retailing (Mbawuni et al., Citation2016), and drug retailing (Ansah et al., Citation2016), show very little focus on women’s shopping experience and the retail brand image in developing countries like Ghana (Pandey & Chawla, Citation2018). Therefore, this study seeks to assess how women perceive the retail mix on the retail brand image and the mediating effect of employee attitude. Based on Srivastava and Thaichon (Citation2023) systematic literature review, (which highlights women’s predominance in shopping activities) this study specifically concentrates on women. The examination of these background characteristics is instrumental in understanding their demographic impact. Additionally, acknowledging these gender differences is vital for retailers to formulate and implement effective marketing strategies (Asad & Abid, Citation2018; Borges et al., Citation2013; Herter et al., Citation2014; Pandey & Chawla, Citation2018).

This study tackles a topic that is rarely discussed in retail literature: the role that employee attitudes play in mediating brand image and marketing mix in retail environments, especially in emerging markets. The study offers fresh perspectives on retail marketing dynamics in a mainly unexplored field. In particular, it broadens our comprehension of how consumer opinions about employee attitudes impact the reputation and image of a retail company.

Theoretical framework and literature review

This study is grounded in the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), a theory from social psychology as its theoretical framework. TRA stems from Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1980), and examines the interplay between individuals’ beliefs, attitudes, norms, intentions, and behaviours. The theory posits that an individual’s attitude towards a behaviour is shaped by their beliefs about the behaviour’s outcomes, coupled with their evaluation of these outcomes. Essentially, it is the individual’s subjective perception that engaging in a particular behaviour will lead to specific outcomes that forms the basis of their beliefs.

In order to better understand consumer decision-making in the context of retailing, the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) theory has been applied. This theory addresses how the nature of the stimulus affects how an organism behaves. S-O-R delves into how stimuli influence an organism’s behaviours, mirroring a learning process where behaviour is fundamentally shaped by the interplay between stimuli and the reactions they elicit. Stimulus, organisms, and responses make up the three structures of the theory. This theory essentially stresses that environmental cues (stimuli) have a direct effect on a consumer’s cognitive state (organism), which in turn influences consumer behaviour (response) (Kim et al., Citation2020; Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2021; Zhu et al., Citation2020).

Consequently, this model suggests that external stimuli impact attitudes by altering the nature of an individual’s beliefs. In this paper, this implies that the retail mix stimuli are what determine the image formed by consumers. The retail mix level is judged by the consumer, and therefore, determines the brand image in consumers’ minds. The alignment between the retail mix and the retail brand image is crucial for fair outcomes. These theories, the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R), are aptly chosen for this study as they delve into the consumer decision-making process, uniquely viewed through the lenses of both a female perspective and the context of a developing economy.

Retail mix

A retail store may refer to organisations whose businesses mainly sell products either in bulk or single pieces to final consumers (Arenas-Gaitán et al., Citation2021; Prasad Konti & Sumanth, Citation2016). As consumer knowledge of the market grows, they can shop for goods and services in many different stores. Retailers provide an assortment of goods and services to consumers to maximise profit from their business operations (Hogreve et al., Citation2017; Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2021). Retailers pursue creative marketing policies that enable them to achieve their businesses’ goals, which are known as the retailing mix.

The term retailing mix describes how a retail store packages its goods and services to meet customer desires and needs (Brocato et al., Citation2012). In other words, the retail mix is the blend of factors a retail store uses to satisfy its customers’ needs and influence their buying decisions (Terblanche, Citation2017). The success of a retail store is dependent on shoppers’ response to the retailing mix because it affects the store’s profits, turnover, market share, store, or brand image, and lastly, the retailer’s survival (Prasad Konti & Sumanth, Citation2016).

Empirical findings from studies on different retail mix instruments vary, which makes it hard for retail managers to get appropriate direction on when to utilise the diverse instruments (Jebarajakirthy et al., Citation2021; Pan & Zinkhan, Citation2006). For instance, Berekoven (Citation1995) offers ten retail marketing components, namely, Assortment, Commercial Brands, Quality and Quality Assurance, Service, Price, Advertising, Sales Promotion, Store Layout and Merchandising, Salesforce, and Location. In a similar vein, Hansen (Citation2003) suggests nine elements that make up the retail mix: price, sales financing, product, assortment, location, store layout, customer service, and complaint handling. The retail mix proposed by Berekoven ignores location whilst Hansen identifies and agrees with the retail mix component by Berekoven and further adds location and complaints management to enrich the retail mix. Again, Müller-Hagedorn (Citation2005) has proposed six retail mix attributes, including Location, Assortment, Price, Promotion Planning, Salesforce, and In-Store-Management. This article tests the retail mix on the retail brand image using Müller-Hagedorn (Citation2005) six retail mix attributes. The uniqueness with Müller-Hagedorn’s retail mmix component is the addition of in-store management. Thus, we discuss the six components of the retail mix: location, merchandise assortment, pricing, communication, store design and display, and customer service (Terblanche, Citation2017; Terblanche & Boshoff, Citation2006).

Retailers use merchandise assortment to create novel balance through colour, size, brand, materials, and quantities (Utami, Citation2014). Merchandise assortment differentiates a retailer from its competitor and conveys a message to customers about the company they are buying from (Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2021). Retailers have a responsibility to plan their merchandise assortment to meet the expectations of their target customers, especially women since they are highly influenced by the assortment of stock. Characteristics such as its uniqueness and new product styles largely affects their perception of the retailer’s brand image (Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, internal design elements, including fixtures, ceilings, colours, and lighting, as well as exterior design elements, including building style, signage, windows, entrance, materials, and lighting, contribute to the store’s aesthetic and communicate the store’s identity to customers (Khan et al., Citation2021). The purchase decisions of women are particularly influenced by the store design and display, which includes the store interior, general interior, store layout, and interior display (Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020). The store design and layout contribute to the retail establishment’s image. As a result, to achieve a favourable perception among consumers, the store design must incorporate every retail mix strategy.

Retailers rely on effective communication to create attractive brand images, draw in buyers to store outlets and websites and motivate them to purchase products (Blakeman, Citation2023; Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020). Communication informs customers of a store’s shopping hours, promotions, product features, fashion trends and other retailers’ facilities. Retail stores often use advertising, individual selling, promotions, publicity, and direct marketing to communicate their brand (Zahid et al., Citation2022). With these elements, retailers can influence the views, attitudes, and behaviours of customers to increase store visits and product purchases.

Store design serves a functional role in protecting, enclosing, and displaying goods conveniently in optimal locations (Levy & Weitz, Citation2012). Additionally, it caters to the specific needs of shoppers, which include the social dimensions of shopping or associating with a particular store. Ultimately, customer service encompasses a range of actions taken by retailers to enhance the overall shopping experience for customers. Customer service comprises components such as tangible (physical facilities, equipment, staff and communication resources), reliability and accurate service, responsiveness (readiness to support buyers and offer swift services), assurance (knowledge and courtesy of sales personnel and their capacity to provide trust and comfort), and empathy (provision of special care to consumers) (Amoako et al., Citation2023; Levy & Weitz, Citation2012). Retail stores can provide additional services in the form of gifts, wrapping, and mailing to gain a sustainable competitive advantage. Nonetheless, this study focuses on three main components of the retail mix: Retail store location and environment, Retail stock/product quality, and Retail pricing.

Retail store location and environment

Retail store location plays a vital role in determining buyer decisions based on where the sales store is located (Gorji et al., Citation2021; Roggeveen et al., Citation2020). For women, location is particularly important since it communicates the image of the retail brand to them (Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020). By situating retail outlets in prime locations, retailers could build a sustainable competitive advantage (Reynolds & Wood, Citation2010; Terblanche, Citation2017) because of the accessibility and convenience such a location offers shoppers. The retailers could change their product assortments, prices, and services in a short time, but when a building is constructed, bought or rented and a store is started, it becomes difficult to change the location for several reasons. For example, if a sales store must relocate, then it may lose some of its loyal customers and staff. Also, the new location might not have the same features, and usually, store fixtures cannot be moved to the new location (Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020; Krey et al., Citation2022).

Choosing the right location is a critical strategic decision, as a poor location can be a significant disadvantage, one that even a very large retailer may struggle to overcome. Therefore, certain criteria such as population size and characteristics, competition, accessibility, access to a parking place, the characteristics of neighbouring stores, property costs, duration of the contract, legal limitations, etc. need to be taken into consideration when making location decisions. Consequently, location is the most significant component of the retail mix and for women especially, because as Edirisinghe et al. (Citation2020) argues females prefer and enjoy in-store shopping experience than online shopping due to the retail environment. We, therefore, hypothesize that:

H1: Retail store location and environment have a positive and significant impact on retail brand image.

H2: Retail stock/product quality has a positive and significant impact on retail brand image.

Retail pricing

Several researchers have explored variations in shopping behaviour within individual households. Kahn and Schmittlein (Citation1989) suggest that this behaviour can differ, especially during major shopping trips by a family. Furthermore, the importance of pricing decisions is emphasized, as they are crucial for companies to maintain healthy profit margins for long-term sustainability (Amir & Asad, Citation2018; Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2021; Venkatesh et al., Citation2022).

It is recommended that the target market, store policies, stock variety, competition and customers be taken into consideration in making pricing decisions (Pradhan, Citation2004). Price is an essential aspect of the retail marketing mix (Amir & Asad, Citation2018; Ho et al., Citation2022). It plays a significant role in consumer decision-making in today’s market, where price sensitivity is high. Consequently, pricing strategies have become a fundamental tool for many retailers (Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2021). Further, shoppers growing inclination to purchase quality goods and services affects the significance of pricing decisions (Zahid et al., Citation2022). Customers’ price consciousness significantly influences their purchasing behaviour, as they generally prefer not to pay high prices for products and services. However, it’s noted that some customers are willing to pay a premium for superior service (Amoako, Citation2020; Bucko et al., Citation2018). Regardless of whether the item is expensive or affordable, every customer, particularly women, seeks the assurance that their purchase is valuable and justifies the price paid (Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020). Hence, retailers must price their goods in a manner that ensures that they make a profit and at the same time satisfy their customers.

H3: Retail pricing has a positive and significant impact on retail brand image.

Retail brand image

The most successful businesses globally, such as Sony, Disney, and Coca-Cola, are successful mainly because of the strength of their brands (Davis, Citation2003). The brand image could be defined as a distinct set of connotations within the minds of target customers (Erdil, Citation2015; Syah & Olivia, Citation2022). It represents beliefs consumers associate with a brand. Thus, the brand image is the buyers’ perception of a product (Erdil & Uzun, Citation2010; Graciola et al., Citation2020; Konuk, Citation2018). The brand image carries emotional value and is not merely a mental picture; it denotes an organisation’s character (Högström et al., Citation2015). The key component of a positive brand image, among other things, is the brand identifier, which supports the core values (Khaled et al., Citation2021). Hence, a brand image is the general impression buyers have of a product or company, which is shaped by all. Adokou and Kyere-Diabour (Citation2017) have indicated that brand image affects customer decisions in the retail industry in Ghana.

Buyers develop different connections with a brand and dependent on their experiences, they create a brand image (Horvâth & Birgelen, Citation2015). Therefore, based on customers’ subjective perceptions of a brand, they form the brand image. The thought behind the brand image is that a customer does not purchase just a product or service, but the image connected to it (Grewal et al., Citation1998). Brand image must be positive, unique, and direct. The brand image could be enhanced by utilising brand communication such as advertisement, packaging, word of mouth, other promotional instruments, etc.

The brand image forms and indicates a product’s features in a way to distinguish it from its competitor’s image (Erdil, Citation2015; Hafez, Citation2018; Rai & Narwal, Citation2022). The brand image comprises several brand attributes, which consist of the functional and mental associations consumers have with the brand either specifically or conceptually. The brand image consists of the product’s appeal, usability, functionality, popularity and general value (Schmitt, Citation2012; Swoboda et al., Citation2016). Hence, users buy a product as well as its image. Therefore, brand image is measured from the consumers’ objective and mental feedback when they buy a product. In this way, a positive brand image enhances the retail store’s goodwill and brand value and creates a positive store image.

In this case, the brand image is operationalised as a store image. The origin of store image is traced back to Martineau (Citation1958, p. 55) when he first defined store image as ‘a store defined in customers’ mind partly based on functional attributes and partly based on psychological attributes’. By this definition, Martineau (Citation1958) considered a store to comprise functional and psychological attributes that make patrons feel the store is different from others. He explained functional attributes as the variety of commodities, design, location, price value relation, and the service that customers could factually compare with other stores. The psychological attributes are attractiveness and luxuriousness that indicate unique attributes of a specific store. After the work of Martineau (Citation1958), the concept of store image has garnered research attention.

For instance, Burlison and Oe (Citation2018) opine that a store image is a set of complex meanings and relations that make buyers differentiate one store from others. In this way, the store image is a positive experience developed by a customer that causes him/her to buy at a specific store (Burlison & Oe, Citation2018). Again, Oxenfeldt (Citation1974) defines store image as complex attributes that customers feel about a store. Thus, it is not just simply the sum of objectively distinct attributes as the various aspects of attributes interact in consumers’ minds.

Employee attitude

Employee attitude refers to the state of mind that makes an employee react positively or negatively toward certain work tasks, products or services, colleagues or managers, or the organisation (Choi, Citation2019). Bad attitudes can lead to indifference to daily tasks and trigger employee agitation by minor problems. A retail employee’s attitude can be measured by his/her interest in the job, working without continuous supervision, having a positive perception of the business and customers, being always ahead of the customer, and the willingness to contribute his/her best to the success of the company (Hussain et al., Citation2020; van Esch et al., Citation2020). To evaluate employee attitude, various formulas have been designed and utilised.

Employees with a positive attitude: 1) develop various ideas about the work and consistently discover new approaches for enhancing their job; they go to every length to provide customer expectation and even provide customer delight; 2) they require little or no supervision to produce results, which allow their supervisors to have adequate time to focus on their jobs; 3) employees with a positive attitude do not simply have ample job knowledge, but they can also foresee the outcomes of various actions; 4) instead of giving negative comments and excuses, workers with a positive attitude look at difficulties in their job as an interesting part of their work, and find new ideas to overcome barriers; 5) when employees have the right attitude, they are willing to contribute to ensuring the competitiveness of the organisation, and they volunteer to take on tasks when they can (Gonzales-Chávez & Vila-Lopez, Citation2021; Qalati et al., Citation2022). According to Makanyeza et al. (Citation2018) and Kim et al. (Citation2019), employee relationships can affect firm performance. Thus, an employee’s attitude has a major role to play in moderating the connection between the retail marketing mix and brand image.

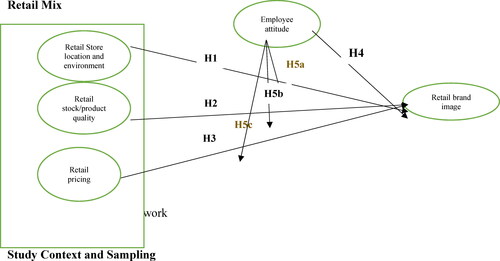

As the first point of contact for customers and those who tend to their needs in a retail sales store, retail employees play a critical role in brand image (De Gauquier et al., Citation2023; Gonzales-Chávez & Vila-Lopez, Citation2021). Because of their accessibility to the customer, employees with a positive attitude also shape the service experience of the customer and improve satisfaction, repeat purchases and customer loyalty (Becker & Jaakkola, Citation2020). The extant literature also shows how employees with a positive attitude can learn new things and understand their customers so that they meet their expectations. This helps to develop a wonderful supplier-customer relationship that can last for a long time. This demonstrates that a highly motivated employee with the necessary positive work attitude to the retail store will enhance productivity, improve sales profitability, and service excellence (Borges et al., Citation2013). The literature reviewed so far explains the need to focus on the moderating effect of employee attitude in the retail mix on retail brand image ().

H4: Employee attitude has a positive and significant impact on retail brand image.

H5: Employee attitude mediates the relationship between a) retail store location and environment, b)retail stock/product quality and c) retail pricing; and retail brand image.

Methodology

Study context and sampling

This study was conducted in Ghana, a developing sub-Saharan African economy in West Africa, where women’s roles keep changing from a typical stay-at-home women culture to career-oriented women. Interestingly, women in this part of the world continue to combine their careers with family responsibilities. The study sample comprised middle-class women who shopped at seven leading malls in Accra, the national capital of Ghana. These malls include Accra, Junction, Achimota, West Hills, A & C Mall, Citydia and Yoo Malls. The mall culture has become a growing shopping avenue for the middle class. Such sales stores provide a convenient shopping experience. Also, the malls stock a variety of products including fast-moving-consumer products, fashion, electronic products, food products, and hardware among others. The respondents were selected through the purposive non-random sampling technique over four weekends. Purposive sampling was considered appropriate because women respondents were most likely to provide different, useful and valuable information in line with the research objective (Campbell et al., Citation2004; Kelly, Citation2010; Patton, Citation2002). Again, this strategy was expedient using the face-to-face data completion process with limited resources (Palinkas et al., Citation2015).

Data collection instrument

The research instrument was divided into two sections. The first section concentrated on the study’s main concepts, and the second section addressed the respondents’ demographic characteristics. All of the instrument’s items were modified from reputable earlier studies, including Bell and Lattin (Citation1998), DeKinder and Kohli (Citation2008), Reynolds and Wood (Citation2010), and Terblanche (Citation2017), in order to guarantee the validity and reliability of the instrument. For the purpose of obtaining an accurate assessment of each construct, all the items were adjusted in this way to fit the study’s context. Suitable analysis such as Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were conducted initially before the SEM to ensure the accuracy of the scales used (see Appendix for details). The data collection instrument was worded in English.

The store location and environment were measured utilising seven items adapted from Terblanche (Citation2017) and Reynolds and Wood (Citation2010); for example, ‘My retail mall is conveniently located’, and ‘Lighting in my favourite sales store is adequate to aid product selection’. The stock/product quality was assessed using four items (DeKinder & Kohli, Citation2008) (e.g. ‘My sales store always has quality products’, and ‘Products in the sales store meet the desired quality standards’). The retail pricing was assessed with five items (Bell & Lattin, Citation1998) (e.g. ‘Prices of products sold match price value’, and ‘There is frequent/special sales promotion to influence purchase’). Employee attitude was determined using five items (e.g. ‘Employees of my sales store are friendly and possess the right knowledge about products and their location’, and ‘Employees demonstrate a high sense of credibility during transactions’). Finally, retail brand image was measured with three items (Burt et al., Citation2007) (e.g. ‘Retail branding creates a good brand image for my sales store’, and ‘Retail brand has made my sales store competitive’). The items were measured with the help of a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Likewise, the remaining items were assessed utilising a five-point Likert Scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data collection

In all, 287 women responded to the study and purposive sampling data collection was adopted. Out of this number, 173 (60.3%) respondents were between 18-28 years, followed by 70 persons (24.4%) who were between 29-39 years while 44 of them were between ages 40-59 years or above. One in every three respondents was married, with the remaining 198 (69%) being single. 46 respondents (16%) did not have a university level education, while the majority 241 (84%) were graduates. Regarding the employment status of respondents, 161 (56.1%) were unemployed, while 126 (43.9%) were employed. When asked about the frequency of shopping at these malls, 80 (27.9%) were regular shoppers, 107 (37.3%) were occasional shoppers, 68 (23.7%) were usual shoppers, and 32 (11.1%) rarely shopped at these malls. For respondents who rarely shopped at the mall, it could be attributed to them being unemployed. When respondents were asked whether they shop based on sales promotions, it was discovered that 197 (68.6%) shopped at malls based on regular promotions, while 90 (31.4%) shopped without being influenced by promotions. Again, 235 (81.9%) were regular shoppers, while 52 (18.1) were first-time shoppers. 118 respondents (41.1) also noted that the malls met their shopping needs, 53 (18.5) answered ‘not really’, 107 (37.3%) were neutral while the remaining 9 (3.1%) indicated ‘not at all’. Regarding shopping expenditure, 230 (80.2%) spend below 400 cedis ($66.00) per visit, 34 (11.8%) spend $105.00, and 23 of them (8%) spend above $140.00. The consent of respondents was sought before the questionnaire was administered. Respondents were assure of the anonymity and their ability to exit the survey whenever they feel they can no longer continue with the survey.

Data analysis

Data were analysed utilising the structural equation modelling partial least squares (PLS-SEM) for two reasons. First, it helps to identify the connection between constructs of a study more comprehensively and second, PLS-SEM has the ability to evaluate the reliability and validity of the instrument’s items, including testing of proposed research hypotheses. Furthermore, PLS-SEM fully stresses the predictive orientation, model and theory testing among other benefits (Becker et al., Citation2013; Sarstedt et al., Citation2014).

Results

Because of the high response rate of 96%, the test for non-response bias was not done (Ledden et al., Citation2011). We put some preventive measures in place to address the possible common method bias in our survey. First, we made sure the questions were unambiguous and direct. Second, in accordance with Ranaweera and Jayawardhena (Citation2014), the questionnaire’s scale items were sporadically placed throughout. Exploratory factor analysis with the extraction of just one factor demonstrated that it made up about 37.85% of the variance explained (that is below 50% variance) (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003; Pugh et al., Citation2011). Hence, common method variance bias is not present in this data. In the examination of data, partial least squares (PLS) were utilised (SmartPLS Release: 3.2.7 (Ringle et al., Citation2005). PLS is not influenced by sample size; therefore, it is ideal for data that is not normally distributed (Hair et al., Citation2011). The significance of each path was checked utilising bootstrap t-values (5000 sub-samples) (Tortosa et al., Citation2009), a technique accessible in PLS.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality gave 0.199 < α < 0.284; p < 0.01 for all items. Likewise, the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality obtained 0.829 < W < 0.908; p < 0.01 for all items. These outcomes suggest that the data is not normally distributed; consequently, PLS-SEM was utilised to conduct confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modelling. After applying PLS to the model, certain retail mix items, such as ‘SLE6’ and ‘SLE7’ under ‘store location and environment’, and ‘RP4’ and ‘RP5’ under ‘Retail Pricing’ were removed as the items significantly cross-loaded into other constructs. The model’s quality criteria were evaluated after purification: Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and average variance extracted values all met the minimum of 0.7, 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, as proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2016) and depicted in . Also, all other item loadings were statistically significant utilising bootstrap t-values (5000 sub-samples) (Tortosa et al., Citation2009). The outcomes suggest that convergent validity was sufficiently met.

Table 1. Reliability and convergent validity.

After checking for convergence validity, the discriminant validity was checked. Discriminant validity was met because the square root of the average variance extracted values for all five constructs was more than the inter-construct associations between them as is depicted in (Barclay et al., Citation1995; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). This demonstrates that each construct is distinct and varies from the other measurement constructs in the model. Besides the Fornell and Lacker criteria, discriminant validity was measured utilising the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT0.85) (Henseler et al., Citation2009). The outcomes also given in show that no connection is more than 0.85; therefore, the five-construct model exhibits discriminant validity.

Table 2. Discriminant validity (square root of AVEs in bold-diagonal).

Structural model

An assessment of the model’s predictive accuracy (R2) demonstrated that retail store location and environment, retail stock/product quality and price explained about 52% of the variance in employee attitude. Furthermore, retail store location and environment, retail stock/product quality, retail pricing and employee attitude jointly accounted for about 37% of the retail brand image variance. These results were greater than the minimum level of 33% recommended by Chin (Citation1998) for good explanatory power. Q2 – values of 0.279 and 0.238 were gotten for employee attitude and retail brand image, respectively; both values are higher than 0, indicating predictive relevance (Chin, Citation2010). Lastly, the effect sizes (f2) calculated for the exogenous variables demonstrated that the retail store location and environment had a medium effect size on employee attitude, whereas retail stock/product quality and retail pricing had small effect sizes on employee attitude. Likewise, retail stock/product quality and employee attitude had small effect sizes on retail brand image, whereas the retail store location and environment and retail pricing had no effect sizes on retail brand image. The outcomes of the predictive accuracy (R2), predictive relevance (Q2) test, and effect sizes (f2) are given in .

Table 3. Predictive accuracy (R2), predictive relevance (Q2) and effect sizes (f2).

Hypothesis testing

The outcomes of the structural model are indicated in . Two of the four hypothesised paths are statistically significant; consequently, the second and fourth hypotheses are affirmed in this context. Precisely, a positive and significant association is present between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image, and employee attitude and retail brand image.

Table 4. Structural path results.

Mediation test

To check for mediation in PLS-SEM, Nitzl et al. (Citation2016) suggest checking the significance of the exogenous variables’ indirect impact on the endogenous variable through the mediators. If the indirect impact is significant, then mediation is present or else there is no mediation (Tetteh & Boachie, Citation2021). From , employee attitude fully mediates the connection between retail store location and environment and retail brand image, and the association between the retail pricing and retail brand image, but partially mediates the connection between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image. Thus, the fifth hypothesis of this study was not confirmed.

Table 5. Mediation of employee attitude on retail brand image.

Discussion of findings

The study’s findings have revealed a positive and significant connection between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image and employee attitude and retail brand image. These findings confirm earlier research indicating that customers consider product features when making buying and consumption decisions, especially with perishables (Amir & Asad, Citation2018; Dokcen et al., Citation2021; Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020; Mehta & Tariq, Citation2020). Conventional wisdom will suggest that low-quality stock could result in lower brand image perception. Retailers with a negative image could enhance their image by stocking brands with a better image, in the same way, a retailer’s image could be destroyed by associating with unfavourable brands (Walsh et al., Citation2017). This study confirms earlier studies (Dokcen et al., Citation2021; Hoppe, Citation2018; Kucharska, Citation2020; Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2021) that indicate that a positive employee attitude can improve retail brand image in the mind of consumers, and a lack of commitment by an employee may also destroy a brand’s reputation.

The study’s findings confirmed earlier work by Akhter et al. (Citation1987), which demonstrates that the store environment does not affect brand evaluation by consumers. However, this study’s findings are contrary to earlier studies, which indicate that the store environment and the pleasantness of shopping can positively influence store image (Dokcen et al., Citation2021; Edirisinghe et al., Citation2020; Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2021). Also, findings indicating that price does affect retail brand image are contrary to earlier research (Beneke & Zimmerman, Citation2014) showing that pricing can be used to build a higher brand image.

The study’s findings also indicate that employee attitude fully mediates the connection between retail store environment and retail brand image, and the association between product price and brand image, but partially mediates the connection between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image. This implies that the store environment does not automatically lead to a good retail brand image, and employee attitude is necessary for this context to create a good brand image. Moreover, this study underscores the importance of employees’ attitudes within the Ghanaian retail context as it is an antecedent for product pricing to lead to brand image. The partial mediation effect of employees’ attitudes between retail stock/product quality and retail brand within the Ghanaian retail context suggests that retail stock/product quality does not always lead to a good retail brand image.

Theoretical and managerial implications

The findings demonstrate that retail stock/product quality leads to a positive retail brand image have significant managerial implications. Retail managers and businesses must develop prioritize maintaining high quality products to ensure that they gain a competitive advantage. Retail managers must invest heavily in quality product control, and employee training to ensure positive employee attitudes since this study indicates that employees’ attitudes affect retail brand perception and reputation. Retail companies should encourage a happy and motivated workforce by offering incentives to their employees, as employee attitude affects how consumers perceive the brand.

Though this study’s findings imply that the retail store environment does not significantly affect the retail brand image, the extant literature supports the contrary, and therefore, retail managers need to work hard to maintain a good store environment. The distribution of resources and approaches that prioritize location and environment over product quality should also be taken into account by retailers. Additionally, retailers need to be flexible and adaptive to changing consumer preferences.

This study makes a substantial theoretical contribution to academic literature, particularly as research in the retail sector within Ghana and Africa is limited. Its emphasis on the behavioural dimensions of women in retail is distinctive, given the scarcity of studies focusing on this demographic in these regions. Additionally, the research enhances the existing body of knowledge on the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and S-O-R theory by delving deeper into the relationship between customer perceptions of employee attitudes and their impact on the image and brand reputation of retail firms in the minds of consumers.

Limitations and future research direction

In a retail grocery store study by Helgesen and Nesset (Citation2010), it was observed that gender does not have any moderating influence on the connection between antecedents and store satisfaction, and females have greater satisfaction levels than males. Again, Pandey and Chawla (Citation2018) recognised that gender moderate antecedents of satisfaction and loyalty. However, satisfaction drivers were found to be gender independent. Therefore, it will be insightful if, in the future, that a study is conducted using the same variables used for this study to assess men. The use of longitudinal data to conduct more research in Ghana’s retail sector is necessary for a long-term view of customer behaviour since this research, and most other research in retailing usually use cross-sectional data. Finally, a study by Jain et al. (Citation2014), Salem and Alanadoly, (Citation2021) and Dokcen et al. (Citation2021) indicated that women are influenced in their purchase decisions when exposed to a show window, which is determined by the extent to which buyers ‘feel good’ about the store. A study combining the constructs used in this study on women and a show window will bring useful retailing insights in Ghana and Africa can be done.

Conclusion

The study concludes that a positive and significant association is present between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image, and employee attitude and retail brand image. This research also concludes that employee attitude completely mediates the connection between store environment and retail brand image, and the association between product price and brand image, but partially mediates the connection between retail stock/product quality and retail brand image.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Dzogbenuku

Robert Kwame Dzogbenuku is a Senior Marketing Lecturer at the Central Business School of Central University (CU) Accra. Robert holds an MPhil and MBA in Marketing from the London Metropolitan University, United Kingdom (UK) and the University of Cape Coast, respectively. In 2000, Robert qualified as a member of the Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM), United Kingdom and served many years in industry marketing and managing services. Robert joined Central University in 2010 a lecturer and researcher. His scholarly works has been published 14 Scopus-rated journals including the International Journal of Emerging Markets, the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Marketing Intelligence and Planning among others. The 2024, AD Scientific Rankings for Business Researchers, ranked him 2nd at his university and the 12th in Ghana. His research interests are climate change and green marketing, entrepreneurship and small business marketing, digital marketing and marketing of financial services. Robert is also a marketing consultant.

Solomon Keelson

Solomon Abekah Keelson is an Associate Professor of Marketing and Strategy at the Business Faculty of Takoradi Technical University, Ghana. He holds a PhD in Marketing and Strategy from Open University, Malaysia, an MBA in Marketing, and a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Prof Keelson also holds a professional certificate in Marketing from the Chartered Institute of Marketing UK. He is a Chartered member of Marketing - UK and Ghana and a fellow of the Chartered Institute of Management Consultants. Keelson is a renowned academic with several publications and taught for over 25 years. He has also worked as theses Assessor (internationally and externally) for various tertiary institutions in Ghana and other countries. Keelson has also gotten industry experience from working with the Electricity Company of Ghana for about 10 years and consulting for companies such as Ghana Rubber Estate and Laine Service. He is currently the Dean of the Faculty of Business, at Takoradi Technical University.

George Kofi Amoako

George Kofi Amoako, is an Associate Professor at Marketing Department and Director at the Directorate of Research Innovation and Consultancy at Ghana Communication Technology University Accra Ghana, an academic and a practising Chartered Marketer (CIM-UK). He obtained his PhD at London Metropolitan University. He obtained Post Graduate Certificate in Education from University of Cape Coast, Ghana in 2014 and Postgraduate International Certificate in Academic Practice from Lancaster University UK in 2018. He consults for British Council Jobs for the Youth Program and Connecting Classroom Program in Ghana. George has published extensively in internationally peer-reviewed academic journals (A, B and C ranked journals) and presented many papers at international conferences in Africa, America, Europe and Australia. His research is in sustainability, marketing, branding, business strategy and CSR. This paper aligns with students’ choices and decision to patronise specific higher learning institutions and the main determinants of such choices made by students particularly those in developing economies.

Antoinette Yaa Benewaa Gabrah

Antoinette is a PhD candidate of University of Professional Studies Accra. She holds an MPhil in Marketing from the University of Ghana. She is currently a faculty at Academic City University College. Antoinette has published in Scopus Indexed journals. Her research interest includes e-business, services marketing, green marketing, entrepreneurship, Small business marketing, family business, Artificial intelligence, Sustainability and digital marketing strategies.

References

- Adokou, F. A., & Kyere-Diabour, E. (2017). Positioning strategies of retail firms in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 18(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2017.12786

- Akhter, H., Reardon, R., & Andrews, C. (1987). Influence on brand evaluation: Consumers’ behaviour and marketing strategies. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 4(3), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb008206

- Amir, A., & Asad, M. (2018). Consumer’s purchase intentions towards automobiles in Pakistan. Open Journal of Business and Management, 06(01), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2018.61014

- Amoako, G. K. (2020). Customer satisfaction: Role of customer service, innovation, and price in the Laundry Industry in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 23(1), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2020.1826855

- Amoako, G. K., Ampong, G. O., Gabrah, A. Y. B., de Heer, F., & Antwi-Adjei, A. (2023). Service quality affecting student satisfaction in higher education institutions in Ghana. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2238468. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2238468

- Ansah, E. K., Whitty, C. J., Bart-Plange, C., & Gyapong, M. (2016). Changes in the availability and affordability of subsidised artemisinin combination therapy in the private drug retail sector in rural Ghana: Before and after the introduction of the AMFm subsidy. International Health, 8(6), 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihw041

- Arenas-Gaitán, J., Peral-Peral, B., & Reina-Arroyo, J. (2021). Ways of shopping & retail mix at the Greengrocers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102451

- Asad, M., & Abid, U. (2018). CSR practices and customer’s loyalty in restaurant industry: Moderating role of gender. NUML International Journal of Business & Management, 13(2), 144–155.

- Badewi, A. A., Eid, R., & Laker, B. (2023). Determinations of system justification versus psychological reactance consumer behaviours in online taboo markets. Information Technology & People, 36(1), 332–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-12-2018-0555

- Barclay, D., Thompson, R., & Higgins, C. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: personal computer adoption and use an illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2), 285–309.

- Becker, J. M., Rai, A., & Rigdon, E. (2013). Predictive validity and formative measurement in structural equation modeling: Embracing practical relevance. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS). Available http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2013/proceedings/ResearchMethods/5/ (Access 11/09/2023).

- Becker, L., & Jaakkola, E. (2020). Customer experience: Fundamental premises and implications for research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(4), 630–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00718-x

- Bell, D. R., & Lattin, J. M. (1998). Shopping behavior and consumer preference for store price format: Why “large basket” shoppers prefer EDLP. Marketing Science, 17(1), 66–88. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.17.1.66

- Beneke, J., & Zimmerman, N. (2014). Beyond private label panache: The effect of store image and perceived price on brand prestige. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(4), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-12-2013-0801

- Berekoven, L. (1995). Erfolgreiches Einzelhandelsmarketing. Grundlagen und Entscheidungshilfen (2nd ed.). Vahlen.

- Blakeman, R. (2023). Integrated marketing communication: Creative strategy from idea to implementation. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Blankson, C., Ketron, S., & Darmoe, J. (2017). The role of positioning in the retail banking industry of Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(4), 685–713. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2016-0055

- Borges, A., Babin, B. J., & Spielmann, N. (2013). Gender orientation and retail atmosphere: Effects on value perception. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41(7), 498–511. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-02-2012-0014

- Brocato, E. D., Voorhees, C. M., & Baker, J. (2012). Understanding the influence of cues from other customers in the service experience: A scale development and validation. Journal of Retailing, 88(3), 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2012.01.006

- Burt, S., Johansson, U., & Thelander, Å. (2007). Retail image as seen through consumers’ eyes: Studying international retail image through consumer photographs of stores. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 17(5), 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593960701631516

- Bucko, J., Kakalejčík, L., & Ferencová, M. (2018). Online shopping: Factors that affect consumer purchasing behaviour. Cogent Business & Management, 5(1), 1535751. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1535751

- Burlison, J., & Oe, H. (2018). A discussion framework of store image and patronage: A literature review. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 46(7), 705–724. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2017-0275

- Campbell, S., Watson, B., Gibson, A., Husband, G., & Bremner, K. (2004). Comprehensive service and practice development: City Hospitals Sunderland’s experience of patient journeys. Practice Development in Health Care, 3(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/pdh.118

- Cassia, F., & Magno, F. (2015). Marketing issues for business-to-business firms entering emerging markets: An investigation among Italian companies in Eastern Europe. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 10(1), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-09-2010-0078

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and application (pp. 645–689). Springer.

- Choi, Y. (2019). A study of the effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between narcissism and job-related attitudes of Korean employees. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1573486. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1573486

- Davis, S. (2003). Brand Asset Management: How businesses can profit from the power of a brand. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(4), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760210433654

- DeKinder, J. S., & Kohli, A. K. (2008). Flow signals: How patterns over time affect the acceptance of start-up firms. Journal of Marketing, 72(5), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.72.5.084

- De Gauquier, L., Willems, K., Cao, H. L., Vanderborght, B., & Brengman, M. (2023). Together or alone: Should service robots and frontline employees collaborate in retail-customer interactions at the POS? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70, 103176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103176

- De Keyser, A., Verleye, K., Lemon, K. N., Keiningham, T. L., & Klaus, P. (2020). Moving the customer experience field forward: Introducing the touchpoints, context, qualities (TCQ) nomenclature. Journal of Service Research, 23(4), 433–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520928390

- Dokcen, C., Obedgiu, V., & Nkurunziza, G. (2021). Retail atmospherics and retail store patronage of supermarkets in emerging economies: Mediating role of perceived service quality. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science, 4(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCMARS-09-2020-0037

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Wang, Y., Alalwan, A. A., Ahn, S. J. (., Balakrishnan, J., Barta, S., Belk, R., Buhalis, D., Dutot, V., Felix, R., Filieri, R., Flavián, C., Gustafsson, A., Hinsch, C., Hollensen, S., Jain, V., Kim, J., Krishen, A. S., … Wirtz, J. (2023). Metaverse marketing: How the metaverse will shape the future of consumer research and practice. Psychology & Marketing, 40(4), 750–776. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21767

- Edirisinghe, D., Nazarian, A., Foroudi, P., & Lindridge, A. (2020). Establishing psychological relationship between female customers and retailers: A study of the small-to medium-scale clothing retail industry. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 23(3), 471–501. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-12-2017-0167

- Erdil, T. S. (2015). Effects of customer brand perceptions on store image and purchase intention: An application in apparel clothing. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.10.088

- Erdil, T. S., & Uzun, Y. (2010). Marka Olmak (2nd ed.). Istanbu: Beta Publishing.

- Esch, F., Langner, T., Schmitt, B. H., & Geus, P. (2006). Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610658938

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gangwani, S., Mathur, M., & Shahab, S. (2020). Influence of consumer perceptions of private label brands on store loyalty–evidence from Indian retailing. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1751905. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1751905

- Gonzales-Chávez, M. A., & Vila-Lopez, N. (2021). Designing the best avatar to reach millennials: Gender differences in a restaurant choice. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(6), 1216–1236. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-03-2020-0156

- Gorji, M., Grimmer, L., Grimmer, M., & Siami, S. (2021). Retail store environment, store attachment and customer citizenship behaviour. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(9), 1330–1347. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2020-0438

- Graciola, A. P., De Toni, D., Milan, G. S., & Eberle, L. (2020). Mediated-moderated effects: High and low store image, brand awareness, perceived value from mini and supermarkets retail stores. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102117

- Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J., & Borin, N. (1998). The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers’ evaluations and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80099-2

- Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.01.001

- Hafez, M. (2018). Measuring the impact of corporate social responsibility practices on brand equity in the banking industry in Bangladesh: The mediating effect of corporate image and brand awareness. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 36(5), 806–822. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2017-0072

- Hair, J. F. J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed, a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hansen, T. (2003). Intertype competition: Speciality food stores compete with supermarkets. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 10(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-6989(01)00038-8

- Helgesen, Ø., & Nesset, E. (2010). Gender, store satisfaction and antecedents: A case study of a grocery store. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(2), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011027222

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modelling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Advances in international higher degree thesis(Vol. 20; pp. 277-319). University of Waterloo, Canada.

- Herter, M. M., dos Santos, C. P., & Pinto, D. C. (2014). “Man, I shop like a woman!” The effects of gender and emotions on consumer shopping behaviour outcomes. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(9), 780–804.

- Ho, C. I., Liu, Y., & Chen, M. C. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of consumers’ attitudes toward live streaming shopping: An application of the stimulus–organism–response paradigm. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2145673. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2145673

- Hogreve, J., Iseke, A., Derfuss, K., & Eller, T. (2017). The service-profit chain: A meta-analytic test of a comprehensive theoretical framework. Journal of Marketing, 81(3), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0395

- Högström, C., Gustafsson, A., & Tronvol, B. (2015). Strategic brand management: Archetypes for managing brands. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.009

- Hoppe, D. (2018). Linking employer branding and internal branding: Establishing perceived employer brand image as an antecedent of favourable employee brand attitudes and behaviours. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(4), 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-12-2016-1374

- Horváth, C., & Birgelen, M. V. (2015). The role of brands in the behavior and purchase decisions of compulsive versus noncompulsive buyers. European Journal of Marketing, 49(1/2), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2012-0627

- Hussain, K., Abbas, Z., Gulzar, S., Jibril, A. B., & Hussain, A. (2020). Examining the impact of abusive supervision on employees’ psychological wellbeing and turnover intention: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1818998. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1818998

- International Monetary Fund. (2023). Navigating global divergences. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/10/10/world-economic-outlook-october-2023

- Iyer, G., & Kuksov, D. (2010). Consumer feelings and equilibrium product quality. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 19(1), 137–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2009.00248.x

- Jain, V., Takayanagi, M., & Malthouse, E. C. (2014). Effects of show windows on female consumers’ shopping behaviour. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(5), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-04-2014-0946

- Jebarajakirthy, C., Das, M., Maggioni, I., Sands, S., Dharmesti, M., & Ferraro, C. (2021). Understanding on-the-go consumption: A retail mix perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102327

- Jibril, A. B., Kwarteng, M. A., Pilik, M., Botha, E., & Osakwe, C. N. (2020). Towards understanding the initial adoption of online retail stores in a low internet penetration context: An exploratory work in Ghana. Sustainability, 12(3), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030854

- Kahn, B. E., & Schmittlein, D. C. (1989). Shopping trip behavior: An empirical investigation. Marketing Letters, 1(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00436149

- Kandampully, J., Zhang, T. C., & Jaakkola, E. (2018). Customer experience management in hospitality: A literature synthesis, new understanding and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 21–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0549

- Kastner, A. N., Mahmoud, M. A., Buame, S. C., & Gabrah, A. Y. (2019). Franchising in African markets: Motivations and challenges from a Sub-Saharan African country perspective. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21987

- Kelly, S. (2010). Qualitative interviewing techniques and styles. In I. Bourgeault, R. Dingwall, & R. de Vries (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative methods in health research(Vol. 19; pp. 307-326). Sage Publications.

- Khaled, A. S. D., Ahmed, S., Khan, M. A., Al Homaidi, E. A., & Mansour, A. M. D. (2021). Exploring the relationship of marketing & technological innovation on store equity, word of mouth and satisfaction. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1861752. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1861752

- Khan, A. A., Asad, M., Khan, G. U. H., Asif, M. U., & Aftab, U. (2021, December). Sequential mediation of innovativeness and competitive advantage between resources for business model innovation and SMEs performance [Paper presentation]. 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA) (pp. 724–728). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DASA53625.2021.9682269

- Kim, M. J., Lee, C. K., & Jung, T. (2020). Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. Journal of Travel Research, 59(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518818915

- Kim, Y. J., Kim, W. G., Choi, H. M., & Phetvaroon, K. (2019). The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behaviour and environmental performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.04.007

- Konuk, F. A. (2018). The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.04.011

- Kosiba, J. P. B., Acheampong, A., Adeola, O., & Hinson, R. E. (2020). The moderating role of demographic variables on customer expectations in airport retail patronage intentions of travellers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102033

- Krey, N., Picot-Coupey, K., & Cliquet, G. (2022). Shopping mall retailing: A bibliometric analysis and systematic assessment of Chebat’s contributions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102702

- Kucharska, W. (2020). Employee commitment matters for CSR practice, reputation and corporate brand performance—European model. Sustainability, 12(3), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030940

- Ledden, L., Kalafatis, S. P., & Mathioudakis, M. (2011). The idiosyncratic behaviour of service quality, value, satisfaction, and intention to recommend in higher education: An empirical examination. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(11–12), 1232–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2011.611117

- Leung, F. F., Gu, F. F., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Online influencer marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(2), 226–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00829-4

- Levy, M., & Weitz, B. A. (2012). Retailing management (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Makanyeza, C., Chitambara, T. L., & Kakava, N. Z. (2018). Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance? Empirical evidence from Harare, Zimbabwe. Journal of African Business, 19(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2017.1410047

- Martineau, P. (1958). The personality of the retail store.

- Mbawuni, J., Mbawuni, M. H., & Nimako, S. G. (2016). The impact of working capital management on profitability of petroleum retail firms: Empirical evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(6), 49. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v8n6p49

- Mehta, A. M., & Tariq, M. (2020). How brand image and perceived service quality affect customer loyalty through customer satisfaction. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 24(1), 1–10.

- Meyer, K., & Peng, M. W. (2016). Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2015.34

- Müller-Hagedorn, L. (2005). Trade marketing (4th ed.). Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Mundel, J., Huddleston, P., Behe, B., Sage, L., & Latona, C. (2018). An eye tracking study of minimally branded products: Hedonism and branding as predictors of purchase intentions. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(2), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2016-1282

- Narteh, B. (2018). Service quality and customer satisfaction in Ghanaian retail banks: The moderating role of price. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 36(1), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2016-0118

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- Omoregie, O. K., Addae, J. A., Coffie, S., Ampong, G. O. A., & Ofori, K. S. (2019). Factors influencing consumer loyalty: Evidence from the Ghanaian retail banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(3), 798–820. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2018-0099

- Oxenfeldt, A. R. (1974). Developing a favorable price-quality image. Journal of Retailing, 50(4), 8+.

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Pan, Y., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2006). Determinants of retail patronage: A meta-analytical perspective. Journal of Retailing, 82(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.11.008

- Pandey, S., & Chawla, D. (2018). The online customer experience (OCE) in clothing e-retail: Exploring OCE dimensions and their impact on satisfaction and loyalty–does gender matter? International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 46(3), 323–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-01-2017-0005

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Paul, J. (2020). Marketing in emerging markets: A review, theoretical synthesis and extension. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(3), 446–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-04-2017-0130

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method Biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Pradhan, S. (2004). Retailing management: Text and cases. Tata-McGraw-Hill.

- Prasad Konti, D. V. V. P., & Sumanth, K. (2016). A study on customer perception towards retail mix strategies of Hyderabad retail market. Journal for Studies in Management and Planning, 2(1), 363–376.

- Pugh, S. D., Groth, M., & Hennig-Thurau, T. (2011). Willing and able to fake emotions: A closer examination of the link between emotional dissonance and employee well-being. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021395

- Qalati, S. A., Qureshi, N. A., Ostic, D., & Sulaiman, M. A. B. A. (2022). An extension of the theory of planned behaviour to understand factors influencing Pakistani households’ energy-saving intentions and behaviour: A mediated–moderated model. Energy Efficiency, 15(6), 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-022-10050-z

- Rai, S., & Narwal, P. (2022). Examining the impact of external reference prices on seller price image dimensions and purchase intentions in pay what you want (PWYW). Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(8), 1778–1806. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-04-2020-0204

- Ranaweera, C., & Jayawardhena, C. (2014). Talk up or criticize? Customer responses to WOM about competitors during social interactions. Journal of Business Research, 67(12), 2645–2656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.002

- Rashid, A., & Barnes, L. (2021). Exploring the blurring of fashion retail and wholesale brands from industry perspectives. The Journal of the Textile Institute, 112(3), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405000.2020.1757295

- Reinartz, W., Dellaert, B., Krafft, M., Kumar, V., & Varadarajan, R. (2011). Retailing innovations in a globalizing retail market environment. Journal of Retailing, 87(1), S53–S66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.04.009

- Reinartz, W., Wiegand, N., & Imschloss, M. (2019). The impact of digital transformation on the retailing value chain. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(3), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2018.12.002

- Reynolds, J., & Wood, S. (2010). Location decision making in retail firms: Evolution and challenge. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 38(11/12), 828–845. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011085939

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2005). Smart pls 2.0 m3, university of hamburg. ‘^’eds.’): Book Smart Pls, 2, M3.

- Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., & Schweiger, E. B. (2020). The DAST framework for retail atmospherics: The impact of in-and out-of-store retail journey touchpoints on the customer experience. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.11.002

- Roper, S., & Alkhalifah, E. (2021). Online shopping in a restrictive society: Lessons from Saudi Arabia. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 24(4), 449–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-01-2020-0012

- Salem, S. F., & Alanadoly, A. B. (2021). Personality traits and social media as drivers of word-of-mouth towards sustainable fashion. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 25(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-08-2019-0162

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Henseler, J., & Hair, J. F. (2014). On the emancipation of PLS-SEM: A commentary on Rigdon (2012). Long Range Planning, 47(3), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2014.02.007

- Schmitt, B. (2012). The consumer psychology of brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.09.005

- Sinha, M., & Sheth, J. N. (2017). Growing the pie in emerging markets: Marketing strategies for increasing the ratio of non-users to users. Journal of Business Research, 86, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.05.007

- Srivastava, A., & Thaichon, P. (2023). What motivates consumers to be in line with online shopping?: A systematic literature review and discussion of future research perspectives. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(3), 687–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-10-2021-0777

- Sürücü, Ö., Öztürk, Y., Okumus, F., & Bilgihan, A. (2019). Brand awareness, image, physical quality and employee behaviour as building blocks of customer-based brand equity: Consequences in the hotel context. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 40, 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.07.002

- Swoboda, B., Weindel, J., & Hälsig, F. (2016). Predictors and effects of retail brand equity–A cross-sectoral analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.007

- Syah, T. Y. R., & Olivia, D. (2022). Enhancing patronage intention on online fashion industry in Indonesia: The role of value co-creation, brand image, and E-service quality. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2065790. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2065790

- Terblanche, N. S. (2017). Customer involvement, retail mix elements and customer loyalty in two diverse retail environments. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 11(2), 1–10.

- Terblanche, N. S. (2017). Customer involvement, retail mix elements and customer loyalty in two diverse retail environments. In The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World: Proceedings of the 2011 World Marketing Congress (pp. 795–804). Springer International Publishing.

- Terblanche, N. S., & Boshoff, C. (2006). A generic instrument to measure customer satisfaction with the controllable elements of the in-store shopping experience. South African Journal of Business Management, 37(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v37i3.603

- Tetteh, J. E., & Boachie, C. (2021). Bank service quality: Perception of customers in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana in the post banking sector reforms era. The TQM Journal, 33(6), 1306–1324. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-05-2020-0096

- Tortosa, V., Moliner, M. A., & Sánchez, J. (2009). Internal market orientation and its influence on organizational performance. European Journal of Marketing, 43(11–12), 1435–1456. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560910989975