Abstract

The explosion of information technology has created new marketing trends and advertising appeals from brands. These brands have also become diverse often defending the equality of the LGBTQ + group as a societal issue which garners attention in the modern era. Many firms frequently depict members of the LGBTQ + community in their advertising to demonstrate their position on this issue. We create a model in the context of the fashion industry, drawing on the Stimulus Organism Response Theory (SOR), to investigate how the rainbow element affected the correlation between advertising appeals, (inner and social) self-expression, and behavioral intention when comparing Vietnamese and U.S. Data from the experimental survey were collected from 472 respondents, including Vietnamese and U.S. The finding indicates that rainbow LGBTQ + ads only moderate the relationship between advertising appeals and self-expressive in the U.S. case, while the Vietnamese case does not. Self-expressive partially mediates the link between advertising appeals and behavioral intention. By comprehending the behavioral traits of both domestic and U.S. consumers, this study seeks to broaden existing research models and provide suitable recommendations to improve the commercial operations of firms.

1. Introduction

Marketing strategies for businesses have always included an important element called advertising appeal. Recently, there has been a rise in the scientific research of advertising appeal, including attempts to synthesize data through meta-analyses. Although single-appeal effects have been the focus of earlier academic studies, moderating factors like the LGBTQ + factor have frequently been disregarded (Yousef et al., Citation2021). Globalization, social media, and information technology have contributed to recent societal shifts. Gender equality and acceptance of sexual orientation variations are on the rise. The number of individuals identifying as LGBTQ + has increased significantly since the 1980s and is currently at its highest (Ciszek & Pounders, Citation2020). In 27 different nations, 19,069 people identify as anything but heterosexual, and 11% of them, according to Ipsos (Citation2021), identify as neither male nor female. Around the world, 80% of individuals identify as heterosexual, 3% as gay, lesbian,…and 11% do not know or will not acknowledge their sexual orientation. After that, concerns over issues affecting the LGBTQ + community grew.

The acronym LGBTQ+, which includes transsexuals (T) with the plus (+) displaying a variety of alternative sexual orientations and gender identities, has replaced the earlier word LGB in the community during the past ten years. LGBTQ + issues are one of the most significant social issues for the general population, according to Cone Communications (Citation2017). Marketers’ interest in this sector has been sparked by the greater LGBTQ + community and this group’s considerable spending power. Since marketing and advertising have made corporate social responsibility (CSR) a core tenet that directs an organization’s values and identity (Scheinbaum et al., Citation2017), an increasing number of businesses are getting active in CSR and LGBTQ + societal issues.

Gender equality and, in particular, the rights of the LGBTQ + community, are major concerns for many people. To increase brand recognition and overall sales for the company, businesses use advertising to raise awareness of the ways they contribute to society and social issues (Castaldo et al., Citation2009). According to Champlin and Li (Citation2020), many businesses make a big effort to market their rainbow-patterned Pride-themed items throughout June in order to show their support for the LGBTQ + community. Most recently, three businesses formally supported the LGBTQ + Equality Act in 2015, which attempted to criminalize discrimination in the US based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. More than 260 corporations have now backed it (Human Rights Campaign, Citation2022).

From the remarks above, it is obvious that businesses are benefiting more and more from using ‘rainbow’ in marketing and advertising. Additionally, more studies on consumer behavior and LGBTQ-supportive policies are recommended (Parshakov et al., Citation2022). The LGBTQ + community is the main subject of this study’s analysis of company marketing initiatives. How will the LGBTQ + aspect (‘rainbow’) affect the relationship between advertising and self-expressive (inner-social), beginning with the advertising appeal, notably in the fashion industry? Find out how their propensities for conduct change after that.

Shepherd et al. (Citation2021) claim that whether LGBTQ representation is regarded as ‘wholesome’ or ‘family-friendly,’ as well as how consumers react to such representation, is influenced by political ideology. Consumer’s political ideology underpins their emotional reactions to such advertisements and that the resulting product-related attitudes. (Northey et al., Citation2020). Vietnam scored a 30 on Hofstede’s scale, making it a communist country with a higher degree of collectivism than individualism. Individual self-expression is often discouraged in countries where collectivism is the prevalent value (Lawrence, Citation2010) and they would be less likely to express their desires or support to the LGBTQ + community openly. The United States, on the other hand, has a score of 60 according to Hofstede, making it a democratic country where individualism is valued highly. Individual self-expression in The United States is encouraged or accepted (Lawrence, Citation2010), and Americans would most likely be more inclined to publicly declare or carry out their wish to support the LGBTQ + community.

Another motivation is based on a common pattern in the US: it is among the most accepting of all time periods (UCLA 2020) and its trajectory continues to go up. Meanwhile, Asian countries (typically Vietnam) are making relatively slow progress in accepting the rights of the LGBTQ + community. This difference is one of the motivations to conduct this research focusing on consumers from these regions. This comparison provides insights into varying levels of LGBTQ + acceptance and cultural sensitivities, which are crucial for tailoring marketing strategies. It helps in understanding the diverse consumer markets, adapting marketing strategies to different cultural contexts, and balancing global branding with local nuances as well as optimizing cost structure in business operation, especially for marketing aspect. The findings aim to guide fashion brands in creating effective, culturally sensitive and socially responsible advertising campaigns across different global markets.

Therefore, the aim of this research is to examine the influence of LGBTQ + factors on advertising appeal and to investigate whether this relationship affects customers’ behavioral intentions. The study also explores the differences between Vietnamese and U.S. consumers’ behavior intentions in these relationships.

Furthermore, the research investigates the moderating effect of rainbow LGBTQ + ads on the relationship between advertising appeal and consumer self-expressive. The findings of this study are expected to contribute to the advancement of knowledge on advertising and consumer behavior and provide valuable insights for firm managers on how to interact with a diverse clientele effectively.

2. Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

2.1. Theoretical framework: the stimulus organism response theory (S-O-R Theory)

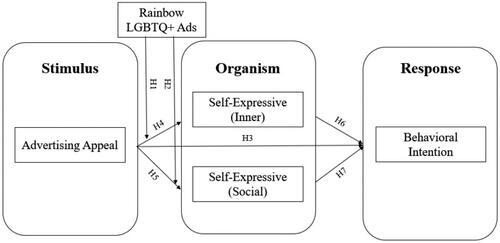

The S-O-R Theory, as expanded by Mehrabian and Russell (Citation1974), is used as the theoretical framework in this study. According to the S-O-R theory, various environmental elements operate as stimuli to alter people’s or creatures’ mental (psychological) health and produce behavioral reactions (Sohaib et al., Citation2022). Moreover, the S-O-R theory has been frequently applied in consumer behavior research (H.-J. Chang et al., Citation2011).

The stimulus is related to an environmental element that activates an organism’s internal states (Song et al., Citation2021). Percy and Rossiter (Citation1992) investigated the impact of advertising stimulation. Earlier research has demonstrated that advertising appeals can operate as an external environmental influence that changes consumers’ views (Zhang et al., Citation2014). Specifically, advertising appeal is involved with the management and presentation of advertising to prospective customers (Schmidt & Eisend, Citation2015). In our study’s context, advertising appeal under the moderating role of rainbow LGBTQ + ads is considered as a stimulus. Brands show their support for LGBTQ + rights by incorporating rainbow colors into their marketing campaigns, such as producing a line of T-shirts with rainbow designs or redesigning their logo to include rainbow colors during Pride Month. These campaigns will act as an effective booster influencing consumers’ perception and assessment of this brand.

The organism serves as a platform for consumers’ affective and cognitive states to be reflected and particular behavioral responses to be generated (Manganari et al., Citation2009). Self-expressive is defined as the degree to which consumers perceive a brand represents their inner self (‘the sort of person I genuinely am on the inside’) or boosts their social self (‘how society perceives me’) (Carroll & Ahuvia, Citation2006). Besides, Loureiro et al. (Citation2012) also indicated that self-expression refers to how well a brand reflects a consumer’s self-concept as well as how effectively it helps them to express their ‘public self’ to others. As a result, we infer that self-expressive can play a function as an organism. In particular, the message of the advertising is that dressing in this brand’s apparel is a way to show one’s individuality and ideals in addition to style. LGBTQ + ads is defined as the representation of the LGBTQ + community in advertising. Leite (Citation2022) indicated that LGBTQ + representation in advertising exists in a variety of forms of iconography such as LGBTQ + flag, rainbow, illustration of same-sex couples, etc. Wearing clothing from these LGBTQ + support collections might be interpreted by a customer who identifies as LGBTQ + or supports LGBTQ + rights. It is a means of expressing both consumers’ social and inner selves, showing their support for LGBTQ + inclusion and identification with the LGBTQ + community.

The response is related to the outputs revealed by consumer actions and behaviors (Roschk et al., Citation2017). A previous study suggested that customers’ responses might be conveyed in the form of behavioral intention (Zhu et al., Citation2019). The degree to which a person is prompted to carry out specific behaviors is known as behavioral intention (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Davis, Citation1989). This study analyzed behavioral intention as consumers’ reactions in the context of companies adopting rainbow LGBTQ + advertising appeals. After interpreting rainbow LGBTQ + advertising appeals, behavioral intentions will start to appear in consumers. By resonating with their values and identity, consumers are prompted to have specific behavioral intentions, for example, purchase this brand’s clothing, either to express solidarity with the LGBTQ + community or to showcase their own identity as part of this community.

In general, advertising appeal under the moderating role of rainbow LGBTQ + ads is a strong stimulus affecting consumers’ perception and evaluation of a specific brand. Then, consumers absorb the stimulus from the information in the brand attributes. Self-expressive acts as a mediator when consumers analyze the stimulus of advertising appeals to formulate their intention. Finally, our study considered behavioral intentions as consumer responses in the context of brands using advertising appeals under the moderating role of rainbow LGBTQ + ads. Therefore, the S-O-R theory provides an appropriate framework for exploring how advertising appeals under the moderating role of rainbow LGBTQ + ads (external stimuli) affect inner & social self-expressive (as organisms) to predict consumers’ behavioral intention (response).

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Moderating effects of rainbow LGBTQ + ads

According to Leite (Citation2022), LGBTQ + representation in advertising takes the shape of imagery such as the LGBTQ + flag, rainbow, illustrations of same-sex couples, and so on. As a result, to measure the direct impact of LGBTQ + ads on behavioral intention, a combination of many of those elements is needed. In this study, the rainbow factor is the main focus since it is the world’s most recognized LGBTQ + symbol. According to Wareham (Citation2020), the rainbow’s distinct and brilliant colours of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet combine to provide a strong emblem for the LGBT + community. Li (Citation2022) demonstrates that during Pride Month in June, companies are more welcoming to LGBTQ + individuals. During this period, businesses promote items and marketing with rainbows and equality-themed language (Champlin & Li, Citation2020). Several global companies have incorporated rainbow colors in their advertising and donated a portion of the revenues from such campaigns to groups that protect the rights of the LGBTQ + community.

Rainbow LGBTQ + ads are supposed to be a form of self-expressive for LGBTQ + consumers. According to Oakenfull and Greenlee (Citation2005), advertisers efficiently target gay and lesbian consumers by allowing them to identify themselves via the product being promoted, which implies the brand is offering LGBTQ + consumers a chance to inner self-express. Bond and Farrell (Citation2020) study also found that exposure to advertisements with sexual imagery in line with the audience’s sexuality leads to favorable consumer behavioral outcomes. So, we propose that rainbow LGBTQ + ads serve as a moderator in the link between advertising appeal and inner self-expressive:

H1: Rainbow LGBTQ + ads moderate the effect of advertising appeal to inner self-expressive.

H2: Rainbow LGBTQ + ads moderate the effect of advertising appeal to social self-expressive.

2.2.2. Advertising appeal & behavioral intention

Advertising appeal includes both emotional and rational appeal, which is assessed on five dimensions: entertainment, informativeness, deceptiveness, irritation, and advertising value (De Battista et al., Citation2021). It is concluded that advertising appeal can lead to a favorable appraisal of specific items or services (Nguyen, Citation2014). Previous research has identified advertising appeal as an external source of information that can influence the establishment of consumer beliefs and attitudes, ultimately leading to product purchase intention. The degree to which a person is compelled to perform certain actions is defined as behavioral intention (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). According to Raza et al. (Citation2017), advertising appeal is deliberately connected to intention. Wardhani and Alif (Citation2019) discovered that advertising appeal, particularly emotional appeals, generated a favorable attitude among consumers toward the commercial and the brand, and so have a higher effect on driving customer purchase intentions. Advertising appeal can lead to the adoption of an attitude or behavior (Lee & Hong, Citation2016). In accordance with previous observations, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Advertising appeal has a positive effect on behavioral intention.

2.2.3. Advertising appeal and self-expressive (inner & social)

The degree to which customers feel a brand symbolizes their inner self (‘the type of person I actually am on the inside’) or promotes their social self (‘how society views me’) is characterized as self-expressive (Carroll & Ahuvia, Citation2006). Besides, Jan et al. (Citation2015) noted that fashion may be used to express self-expressive, which can help individuals improve their social standing and become more accepted in a class of society (Rahman et al., Citation2018). As a result, this study chose the fashion industry due to its relationship to self-expressive.

More study into two types of self-expressive brands is required, according to the emerging literature on the importance of brand self-concept. Recent research on self-expressive brands of Gaustad et al. (Citation2019) also showed that the impacts of brands on the ability to express the inner or social self should be explored individually. Consequently, we perform the research with a separation of inner and social self-expressive.

Self-expressive brands reflect the inner self, mirror consumers’ true selves, serve as an extension of their personality, and represent the type of person they are on the inside (Carroll & Ahuvia, Citation2006). Consumers nowadays regularly use brands as a way of self-expressive, therefore it stands to reason that they would choose items that match their self-concept (Cătălin & Andreea, Citation2014). Previous research has also shown that congruent advertising appeals to viewers’ self-concepts are better than incongruent appeals when it comes to optimizing advertising effectiveness (C. Chang, Citation2014). Therefore, the following hypothesis is logically proposed by this study:

H4: Advertising appeal has a positive effect on inner self-expressive.

H5: Advertising appeal has a positive effect on social self-expressive.

2.2.4. Self-expressive (inner & social) and behavioral intention

Customers use brands to represent themselves, according to consumer behavior research (Belk, Citation1988), which piqued marketers’ interest in examining the impact of self-expressive on behavioral intention. Significant research demonstrates that consumers form strong self-brand links in which brands become key aspects of their self-expressive (Sprott et al., Citation2009), and that such perceptions can have a significant influence on actions (Ruane & Wallace, Citation2015). Consumers who perceive a brand to be self-expressive are more likely to advocate that brand favorably (Ruane & Wallace, Citation2015). In accordance with the findings, inner self-expressive can have a favorable effect on behavioral intention. Moreover, inner self-expressive can act as a mediator between advertising appeal and behavioral intention.

H6: Inner self-expressive has a positive effect on behavioral intention.

Social self-expressive is considered to be significant in determining consumer behavioral intentions. Individuals, according to Hardy and Van Vugt (Citation2006), have a larger motivation to consume in a way that helps society. This is also a reason for firms pursuing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in their operations. Preceding studies indicated that CSR has a positive impact on customers’ behavioral intention including purchase intention, recommend intention, loyalty product evaluation, word of mouth and so on (Deng & Xu, Citation2017; Palihawadana et al., Citation2016; Walsh & Bartikowski, Citation2013). Furthermore, consumers who contact with socially self-expressive brands are more likely to tolerate a brand’s wrongdoing (Wallace et al., Citation2014). Similar to inner self-expressive, we believe the hypothesis of social self-expressive has a favorable influence on behavioral intention. Additionally, social self-expressive can mediate the link between advertising appeals and behavioral intention.

H7: Social self-expressive has a positive effect on behavioral intention.

In general, our proposed research model was developed from the S-O-R theory. Advertising appeal is predicted to have a positive influence on consumers’ inner and social self-expressive, which leads to consumers’ behavioral intention with the moderating effect of rainbow LGBTQ + ads ().

3. Methodology

According to Miller (Citation2005), the experimental approach has been extensively used in consumer behavior research as a powerful way to examine cause-and-effect relationships with a purposely narrow focus and more conclusive findings than other research methods such as observations or surveys. In addition to developing new theories or testing the validity of current ones, experimental consumer research studies can also be used to investigate the fundamental causes of phenomena and establish their boundary conditions (Morales et al., Citation2017). The best way to examine causal hypotheses is through experimental research since it can confidently establish the first three causality criteria, including association, time order, and non-spuriousness (Chambliss & Schutt, Citation2018).

3.1. Data collection and sample

To construct an online experiment approach with Vietnamese consumers and U.S. consumers, this study employs data obtained through a self-administered online questionnaire in the form of a Microsoft Form. We conducted an online survey and divided the respondents into two groups at random: those who notice rainbow LGBTQ + ads and those who do not. In this way, we assess the variations in how advertising appeal affects customers’ behavioral intentions. To prevent the respondents from having preconceived notions about real fashion brands, we first created a fictional fashion brand named Mig Clothing. The design of the products and logos (non-LGBTQ+ & LGBTQ+) is then depicted using graphics ().

We used the same survey settings for an 8-week global survey. The questionnaire was distributed through Facebook online survey filling groups for Vietnamese participants. Additionally, the survey was distributed using the Messenger app, with contacts urged to complete the questionnaire and share it with other parties. For U.S. participants, the study team traveled to An Thuong streets, My An beach, and Hoi An ancient town, where the majority of foreigners visit and live, to disseminate the survey through a QR code. Furthermore, the team distributed the survey by links and QR codes to foreign exchange survey and foreign expat groups on Facebook. For the sole purpose of this study, all participant data will be maintained in confidence and will not be identified. We employed a check attention question which asked, ‘Please select the response ‘Paper’’ for this question: How do you feel?’ to assess the participants’ attention. Also, the concentration test questions ‘Please choose ‘Agree’ option’ and ‘Please choose ‘Disagree’ option’ (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree) are utilized in the questionnaire. Those who made a choice other than the mandatory response were not included in the sample. After eliminating outliers and incomplete surveys, 472 of the 526 administered questionnaires were determined to be suitable for data analysis. Respondents who were not from the United States were excluded from the sample. In addition, some demographic questions such as gender, age, education level, nationality, and occupation were included at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Based on the research overview, a questionnaire was created and then customized for the Vietnamese and global research contexts. The questions were initially written in English before being translated into Vietnamese. The Vietnamese version of the survey is then back-translated by 5 lecturers from the Faculty of English, University of Foreign Language Studies, University of Danang, Vietnam to ensure translation accuracy. To improve the content validity of the measurement, a pre-test was carried out with a sample of 15 Vietnamese and 15 U.S. users. They were requested to complete the survey and review the questionnaire for readability, relevance, and meaning.

3.2. Variables measurement

The constructs’ measurement items were adopted from previous studies and modified to correspond with the present research setting to ensure content validity. The questionnaire for this study has 26 measurement items modified from earlier research (See Appendix B). Advertising appeal was specifically assessed using 15 items derived from a previous study by Lou and Yuan (Citation2019). Wallace et al. (Citation2014) research was used to assess Inner self-expressive (04 items) and Social self-expressive (04 items). Finally, 03 items derived from Bian and Forsythe (Citation2012) comprised behavioral intention. The measures of each concept were rated using a 5-point Likert scale. ‘Totally Disagree’ was placed at ‘1’ on the scale, and ‘Totally Agree’ was moored at ‘5’. The questionnaire was divided into three sections: an introduction, demographic data of the respondents, and a 26-item evaluation of those respondents (See Appendix C).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistic

Referring to the research sample description, female constitutes over half of the respondents (equivalent to 53.2%), while males and other genders comprise 36.4% and 10.4%, respectively. Regarding the age criterion, there are 41.1% of respondents in the age range of 18 to 25, while the figure for participants above 45 years old is the lowest (about 12.7%). The proportion of respondents having bachelor’s degrees is the highest, at 40.3%, followed by the data of participants whose highest education level is high school (21.0%). The lowest figure is 2.1% for respondents having a Ph.D. degree. Lastly, students account for the highest portion (32.6%), whereas clerks and officers rank second with 18.0% (See Appendix A). Considering the research sample description by proposed variables, respondents tend to answer at a high level (mean value almost above 3) for most items ().

Table 1. Sample description.

4.2. Measurement validity and construct reliability

In both cases, Cronbach’s alpha of all the latent variable’s advertising appeal, inner self-expressive, social self-expressive, and behavioral intention met the minimal standard of 0.6. The composite reliability of these four constructs also lies between 0.8 and 0.95. Also, VIFs are under the 3.0 cutoff, which means multicollinearity is not a problem ( and ) (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Measurement validity and construct reliability of Vietnamese sample.

Table 3. Measurement validity and construct reliability of U.S. sample.

4.3. Exploratory factor analysis

In both cases, all scales met the standards of having a KMO between 0.05 and 1, a Sig. value below 0.05, and a cumulative percent of extraction above 50%. Also, all item factor loadings surpass 0.5. They reveal that the sample qualifies for EFA analysis, variable correlations exist and each latent variable only generates one component.

4.4. Structural equation model testing

Measuring the connections between observed and latent variables using structural equation modeling (SEM) could include two primary methods: Covariance based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) and Partial Least Squares based Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Among them, PLS-SEM approach enables researchers to estimate complex models involving various constructs, indicator variables, and structural pathways without imposing distributional hypotheses on the data (Sarstedt et al., Citation2017; Wold, Citation1982). Additionally, PLS-SEM can be utilized for both prediction and explanation, while CB-SEM is solely applicable to explanation (Hair et al., Citation2017). According to Dash and Paul (Citation2021), PLS-SEM has the major advantage of being able to specify both formative and reflective measurement models, whereas CB-SEM is limited to utilization with reflective measurement models. Since our study’s model combines formative and reflective constructs, PLS-SEM would be the most appropriate technique for our analysis. In other words, structural model testing with SmartPLS 4.0 is employed to assess the hypotheses of our study ().

Table 4. Structural equation modeling results.

4.4.1. The moderating effect of rainbow LGBTQ + ads

Regarding the VN case, ADS had an insignificant moderating impact on the linking between AP and SI (β = -.155, p> .1), also AP and SS (β = -.016, p> .1). Contrarily, in the U.S. case, ADS significantly and positively moderated both relationships between AP and SI (β = .250, p< .05), AP and SS (β = .188, p< .05). Thus, H1 and H2 were supported in the US but not in Vietnam. The observed results showed that rainbow LGBTQ + ads only moderate the correlation between advertising appeal and self-expressive in the case using a the U.S. sample, while the remaining case does not. The reason could be that there is a greater level of self-determination and higher acceptance towards the LGBTQ + community in the US compared to Asian countries. The mainstream beliefs and attitudes towards this community are shifting in meaningful ways (Frankel & Ha, Citation2020). Hence, in the U.S. sample, the moderating role of rainbow LGBTQ + ads fosters the customer’s perception of self-expressive brands, shedding light on why there was a rapidly growing interest in LGBTQ culture and its prominence in fashion marketing (Bhat et al., Citation1996).

4.4.2. The direct effect of advertising appeal on behavioral intention

AP has a significant and supportive influence on BI in both the VN case (β=.309, p < .001) and U.S. case (β=.290, p < .001), this finding is also in line with the prior study’s findings of Diehl et al. (Citation2011); Raza et al. (Citation2019). Hence, the results support H3 in both Vietnam and the US context.

4.4.3. The mediating effect of inner self-expressive

Referring to the VN case, there is a favorable connection between AP and SI (β=.454, p < .001), SI and BI (β=.161, p< .05). Therefore, SI partially mediates the correlation between AP and BI. Furthermore, SI had a substantial and possible effect on SS (β=.690, p< .001), and SS had a similar effect on BI (β=.401, p< .001). It means that SI and SS performed as partial serial mediators in the relationship between AP and BI. In U.S. case, similarly, SI partially mediated the favorable link between AP and BI, and that link was also partially serial mediated by SI and SS. Thus, supporting H4 and H6 in both countries studied.

4.4.4. The mediating effect of social self-expressive

There is a substantial relationship between AP and SS in both the VN case (β=.201, p< .01) and U.S. case (β=.173, p< .05). Similarly, both cases showed that SS had a significant impact on BI (p< .001). Therefore, in both cases, SS partially mediated the correlation between AP and BI, accepting H5 and H7 in these two national settings.

Inner self-expressive and social self-expressive play quite well as mediators associating advertising appeal with users’ behavioral intention. Besides, there was an unexpected outcome that inner self-expressive had a significant influence on social self-expressive. Consumers express their inner identity through brands (Batra et al., Citation2012), in which tangible items play a role as means of expression within the framework of the fashion industry. Consequently, this also leads to how society perceives them. Since inner and social self-expressive are linked, the relationship between advertising appeal and behavioral intention is serially mediated through these two variables.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Theoretical implications

First, we examine the role rainbow LGBTQ + ads play in regulating self-expressive brands, particularly the social element, based on the S-O-R Theory. Additionally, the involvement of rainbow LGBTQ + ads as moderators has helped in the construction of a model for the impact of advertising appeals on consumers’ behavioral intentions. We focused on improving the study methods and exploiting the impact of advertising containing LGBTQ + components on both Vietnamese and U.S. consumers as it is a new factor compared to prior studies. This exemplified the importance of rainbow LGBTQ + ads in marketing, which may influence consumers’ behavioral intentions directly or indirectly based on their demographic, cultural, and geographical traits. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) iconography has become more prevalent in advertisements in recent years, drawing the attention of marketing professionals and academics (Northey et al., Citation2020). Understanding how these consumers are represented in the media is increasingly important as the LGBTQ movement matures and the market’s interest rises (Nölke, Citation2018). Eisend and Hermann (Citation2019) and Ginder and Byun (Citation2015) identified gaps in the existing body of literature pertaining to LGBTQ consumer research. This present study aims to address these gaps by providing a more comprehensive elucidation of the factors influencing the perception of rainbow LGBTQ representation in advertising, specifically regarding its favorability.

Second, we learned from our research that self-expressive brands have a partial mediation function in the link between advertising appeals and behavioral intention. Based on earlier research, this conclusion is entirely consistent. We anticipate that the partial mediating function of self-expressive brands will add to the list of factors influencing the relationship between advertising appeal and behavioral intention from previous studies since the relationship between advertising appeal and behavioral intention is dynamic in nature (Raza et al., Citation2017).

Finally, our research will further the concept of examining how societal values, particularly gender equality, affect the LGBTQ + community’s right to self-expressive and the reimagining of marketing strategies for the digital age.

5.2. Managerial implications

Businesses, marketers that wish to engage consumers globally should think about creating marketing campaigns with advertising that support societal principles like gender equality, particularly for the LGBTQ + community (when this issue is spreading across countries). These messages ought to satiate consumers’ desires for internal and interpersonal expression. They also need to be more watchful to avoid being accused of ‘rainbow washing’. To raise revenues, some brands tried to concentrate on developing rainbow marketing strategies by capitalizing on new social trends and growing consumer base. This might cause waves of controversy if clients feel exploited or if members of LGBTQ + community feel offended by being used as a tool for business gain.

The study found that consumer reactions to advertisements featuring or excluding LGBTQ + aspects differ by countries. Based on the result, rainbow LGBTQ + ads only moderate the correlation between advertising appeal and self-expressive in U.S. case, meanwhile, the opposite situation was witnessed in Vietnamese case. Following that, in regions with more acceptance and positive growth in attitudes towards the LGBTQ + community, like the U.S., such advertising appeals are more likely to resonate with consumers on a personal level. In contrast, in areas where acceptance is lower, as often found in some Asian countries like Vietnam, the impact of these ads might be less pronounced in terms of influencing self-expressive perceptions.

These findings underscore the importance for marketers to exercise caution when creating advertising campaigns with LGBTQ + components in various countries, especially in developing countries with Asian cultures where mistakes may cost businesses money and potential customers. It also highlights the importance for companies to consider how consumers perceive and evaluate brand advertising to develop effective and ethical marketing strategies. Global informed consumers have higher expectations for products, services, information, presenting both challenges and opportunities for firms to achieve sustainable growth goals while addressing social issues.

Furthermore, consumers are putting increasing pressure on advertisers to be inclusive (Wiklund, Citation2022). Decisions about whether to include LGBTQ + representation may be made in a hurry without giving careful thought to the brand’s personality, its audience, and the complex interactions between these factors. This is similar to other pressures that force marketers to make quick adjustments to the marketing environment (e.g. branding changes, websites pivoting to video content, etc.). Additionally, our study points to the possibility that ideology may influence creative decisions more generally. It is also important to consider consumer reactions to advertising to avoid accusations of rainbow-washing in marketing, especially amid the globally growing acceptance of the LGBTQ + community.

The acceptance of LGBTQ + individuals in developed countries like the US is an emerging trend that may lead to changes in consumer habits globally. This presents an opportunity for companies to adjust their production and marketing strategies to promote gender equality principles. Adapting to the evolving social and human rights landscape will be beneficial for businesses, and this trend is being driven by strong countries and is expected to spread globally.

Finally, businesses should prioritize meeting the needs of LGBTQ + consumers as society becomes more accepting of gender equality. It is important for businesses to establish goods and marketing plans that respect and do not exploit this group of people to avoid negative perceptions. Showing kindness and respect towards the LGBTQ + community can help businesses flourish sustainably.

6. Limitations and further research

First, the number of samples will be limited, making it difficult to give the most objective results. Second, we employed only three products from two brands in our experiment. The number of goods simply represented the bare minimum for product generalizability. In future research, it would be good to add more products from various brands. Third, we test the effects of advertising images on behavioral intention, however, there are other factors to consider. In other words, LGBTQ + ads and self-expressive brands are merely two of the decision-making criteria and may not ultimately affect a customer’s purchasing choice. Further research is thus required to develop a more comprehensive campaign that people may directly experience. The sample size might be increased and more variables regarding the perceptions of the consumers might be added. The study can be conducted in the context of some other industry (while we have just studied the fashion area). Future studies look at more dimensions of the influence of the LGBTQ + factor in several different industries, in addition to the factors affecting customers’ self-expression.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Loan Pham Thi Be

Loan Pham Thi Be a Full-time Lecturer and Researcher of the Faculty of International Business at University of Economics-The University of Danang since 2012. Her research interests include Social Marketing, Brand Management, Cross-Cultural Management, and Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior. She recently holds a Ph.D. in Marketing from Grenoble Alpes University.

Dinh Tran Dinh

Dinh Tran Dinh a fourth-year student in International Business major at University of Economics, The University of Danang. She takes an interest in researching Social Responsibility, recently specifically in the setting of social entrepreneurship. Through her favorite research field, she aims to investigate the effects of how social organizations operate.

Ha Le Thi Khanh

Ha Le Thi Khanh an International Business student at University of Economics, The University of Danang. She is interested in social sciences and marketing fields. Her interest focuses on the underlying causes of customer behavior and motivation in diverse marketing contexts such as e-commerce.

Thao Dinh Thi Phuong

Thao Dinh Thi Phuong a fourth-year International Business student at University of Economics, The University of Danang. She is interested in understanding how psychological factors affect users’ behavior and their decision-making. Understanding these factors will assist any marketer in understanding the behavior of their consumers to successfully appeal to them.

Thao Le Nguyen Phuong

Thao Le Nguyen Phuong a last-year International Business student at University of Economics, The University of Danang. She is interested in the human desire to experience the product through other senses, how to integrate Virtual Reality Technology into the buying experience, and how materials to activate senses influence consumer decisions.

References

- Ajzen, I & Fishbein. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predictiing social behavior. Englewood Cliffs. Retrieved from https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1572543024551612928

- Angelini, J. R., & Bradley, S. D. (2010). Homosexual imagery in print advertisements: attended, remembered, but disliked. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918361003608665

- Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R. (2012). Brand love. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.09.0339

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Bhat, M. A., Philp, A. V., Glover, D. M., & Bellen, H. J. (1996). Chromatid segregation at anaphase requires the barren product, a novel chromosome-associated protein that interacts with topoisomerase II. Cell, 87(6), 1103–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81804-8

- Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.010

- Bond, B. J., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). Does depicting gay couples in ads influence behavioral intentions?: How appeal for ads with gay models can drive intentions to purchase and recommend. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(2), 208–221. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2019-026

- Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-006-4219-2

- Castaldo, S., Perrini, F., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2009). The missing link between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust: The case of fair trade products. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9669-4

- Cătălin, M. C., & Andreea, P. (2014). Brands as a mean of consumer self-expression and desired personal lifestyle. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.427

- Chambliss, D. F., & Schutt, R. K. (2018). Causation and experimental design. In Making sense of the social world: Methods of investigation (6th ed, pp. 120–149). Sage Publications Inc.

- Champlin, S., & Li, M. (2020). Communicating support in pride collection advertising: The impact of gender expression and contribution amount. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 14(3), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2020.1750017

- Chang, C. (2014). Why do Caucasian advertising models appeal to consumers in Taiwan? International Journal of Advertising, 33(1), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-1-155-177

- Chang, H.-J., Eckman, M., & Yan, R.-N. (2011). Application of the stimulus-organism-response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 21(3), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2011.578798

- Chauhan, G., & Shukla, T. (2016). Social media advertising and public awareness: Touching the LGBT Chord!. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 18, 145–155.

- Chintrakarn, P., Treepongkaruna, S., Jiraporn, P., & Lee, S. M. (2020). Do LGBT-supportive corporate policies improve credit ratings? An instrumental-variable analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4009-9

- Choi, L., & Burnham, T. (2020). Brand reputation and customer voluntary sharing behavior: The intervening roles of self-expressive brand perceptions and status seeking. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(4), 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-12-2019-2670

- Ciszek, E. L., & Pounders, K. (2020). The bones are the same: An exploratory analysis of authentic communication with LGBTQ publics. Journal of Communication Management, 24(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-10-2019-0131

- Cone Communications. (2017). CSR study. Retrieved 30 March 2023, from http://conecomm.com/2017-cone-communications-csr-study-pdf

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

- Davis, F. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- De Battista, I., Curmi, F., & Said, E. (2021). Influencing factors affecting young people’s attitude towards online advertising: A systematic literature review. International Review of Management and Marketing, 11(3), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.32479/irmm.11398

- Deng, X., & Xu, Y. (2017). Consumers’ responses to corporate social responsibility initiatives: The mediating role of consumer–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(3), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2742-x

- Diehl, M., Hay, E. L., & Berg, K. M. (2011). The ratio between positive and negative affect and flourishing mental health across adulthood. Aging & Mental Health, 15(7), 882–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.569488

- Eisend, M., & Hermann, E. (2019). Consumer responses to homosexual imagery in advertising: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advertising, 48(4), 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1628676

- Frankel, S., & Ha, S. (2020). Something seems fishy: Mainstream consumer response to drag queen imagery. Fashion and Textiles, 7(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-020-00211-y

- Gaustad, T., Samuelsen, B. M., Warlop, L., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2019). Too much of a good thing? Consumer response to strategic changes in brand image. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(2), 264–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.01.001

- Ghaziani, A., Taylor, V., & Stone, A. (2016). Cycles of sameness and difference in LGBT social movements. Annual Review of Sociology, 42(1), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112352

- Ginder, W., & Byun, S.-E. (2015). Past, present, and future of gay and lesbian consumer research: critical review of the quest for the queer dollar. Psychology & Marketing, 32(8), 821–841. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20821

- Hair, J. J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hardy, C. L., & Van Vugt, M. (2006). Nice guys finish first: The competitive altruism hypothesis. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206291006

- Hossain, M., Atif, M., Ahmed, A., & Mia, L. (2020). Do LGBT workplace diversity policies create value for firms? Journal of Business Ethics, 167(4), 775–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04158-z

- Human Rights Campaign. (2022). The 2022 Corporate Equality Index. Retrieved 30 March 2023, from Human Rights Campaign website: https://www.hrc.org/resources/corporate-equality-index

- Ipsos. Ipsos. (2021). LGBT + Pride 2021 Global Survey. Retrieved 30 March 2023, from website https://www.ipsos.com/en/lgbt-pride-2021-global-survey-points-generation-gap-around-gender-identity-and-sexual-attraction

- Jan, M. T., Abdullah, K., & Momen, A. (2015). Factors influencing the adoption of social networking sites: malaysian muslim users perspective. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 3(2), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.7763/JOEBM.2015.V3.192

- Lawrence, A. A. (2010). Societal individualism predicts prevalence of nonhomosexual orientation in male-to-female transsexualism. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9420-3

- Lee, J., & Hong, I. B. (2016). Predicting positive user responses to social media advertising: The roles of emotional appeal, informativeness, and creativity. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 360–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.01.001

- Leite, F. (2022). LGBTQIA + representations in advertising studies: A look at the Brazilian scientific production of Intercom, Compós and Pró-Pesq PP from 2000 to 2020. Intercom: Revista Brasileira De Ciências Da Comunicação, 45, e2022102.

- Li, M. (2022). Influence for social good: Exploring the roles of influencer identity and comment section in Instagram-based LGBTQ-centric corporate social responsibility advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 41(3), 462–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1884399

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Ruediger, K. H., & Demetris, V. (2012). Brand emotional connection and loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 20(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2012.3

- Manganari, E. E., Siomkos, G. J., & Vrechopoulos, A. P. (2009). Store atmosphere in web retailing. European Journal of Marketing, 43(9/10), 1140–1153. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560910976401

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology (pp. xii, 266). The MIT Press.

- Miller, S. (2005). Experimental design and statistics (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Morales, A. C., Amir, O., & Lee, L. (2017). Keeping it real in experimental research—understanding when, where, and how to enhance realism and measure consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(2), 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx048

- Nguyen, H. (2014). Advertising appeals and cultural values in social media commercials in UK, Brasil and India: Case study of nokia and samsung. International Journal of Business, Human and Social Sciences, 7 (0). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1337363

- Nölke, A.-I. (2018). Making diversity conform? An intersectional, longitudinal analysis of LGBT-specific mainstream media advertisements. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(2), 224–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1314163

- Northey, G., Dolan, R., Etheridge, J., Septianto, F., & Esch, P. V. (2020). LGBTQ imagery in advertising: How viewers’ political ideology shapes their emotional response to gender and sexuality in advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(2), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2020-009

- Oakenfull, G. K., & Greenlee, T. B. (2005). Queer eye for a gay guy: Using market-specific symbols in advertising to attract gay consumers without alienating the mainstream. Psychology and Marketing, 22(5), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20066

- Palihawadana, D., Oghazi, P., & Liu, Y. (2016). Effects of ethical ideologies and perceptions of CSR on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 4964–4969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.060

- Parshakov, P., Naidenova, I., Gomez-Gonzalez, C., & Nesseler, C. (2022). Do LGBTQ-supportive corporate policies affect consumer behavior? Evidence from the video game industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 187(3), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05137-7

- Percy, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (1992). A model of brand awareness and brand attitude advertising strategies. Psychology & Marketing, 9(4), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220090402

- Rahman, M., Albaity, M., Isa, C. R., & Azma, N. (2018). Towards a better understanding of fashion clothing purchase involvement. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 9(3), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-03-2017-0028

- Raza, S. H., Abu Bakar, H., & Mohamad, B. (2019). The effects of advertising appeals on consumers’ behavioural intention towards global brands: The mediating role of attitude and the moderating role of uncertainty avoidance. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(2), 440–460. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-11-2017-0134

- Raza, S. H., Bakar, H. A., & Mohamad, B. (2017). Relationships between the advertising appeal and behavioral intention: The mediating role of the attitude towards advertising appeal. SHS Web of Conferences, 33, 00022. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20173300022

- Roschk, H., Loureiro, S. M. C., & Breitsohl, J. (2017). Calibrating 30 years of experimental research: A meta-analysis of the atmospheric effects of music, scent, and color. Journal of Retailing, 93(2), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2016.10.001

- Ruane, L., & Wallace, E. (2015). Brand tribalism and self-expressive brands: Social influences and brand outcomes. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(4), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2014-0656

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2017). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In C. Homburg, M. Klarmann, & A. Vomberg (Eds.), Handbook of market research (pp. 1–40). Springer International Publishing.

- Scheinbaum, A. C., Lacey, R., & Liang, M.-C. (2017). Communicating corporate responsibility to fit consumer perceptions: How sincerity drives event and sponsor outcomes. Journal of Advertising Research, 57(4), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2017-049

- Schmidt, S., & Eisend, M. (2015). Advertising repetition: A meta-analysis on effective frequency in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 44(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1018460

- Shepherd, S., Chartrand, T. L., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2021). Sincere, not sinful: Political ideology and the unique role of brand sincerity in shaping heterosexual and LGBTQ consumers’ views of LGBTQ Ads. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 6(2), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1086/712608

- Snyder, B. (2015). LGBT Advertising: How Brands Are Taking a Stance on Issues

- Sohaib, M., Wang, Y., Iqbal, K., & Han, H. (2022). Nature-based solutions, mental health, well-being, price fairness, attitude, loyalty, and evangelism for green brands in the hotel context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 101, 103126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103126

- Song, S., Yao, X., & Wen, N. (2021). What motivates Chinese consumers to avoid information about the COVID-19 pandemic?: The perspective of the stimulus-organism-response model. Information Processing & Management, 58(1), 102407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102407

- Sprott, D., Czellar, S., & Spangenberg, E. (2009). The importance of a general measure of brand engagement on market behavior: Development and validation of a scale. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.46.1.92

- Wallace, E., Buil, I., & de Chernatony, L. (2014). Consumer engagement with self-expressive brands: Brand love and WOM outcomes. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2013-0326

- Walsh, G., & Bartikowski, B. (2013). Exploring corporate ability and social responsibility associations as antecedents of customer satisfaction cross-culturally. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 989–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.022

- Wardhani, P. K., & Alif, M. G. (2019). The effect of advertising exposure on attitude toward the advertising and the brand and purchase intention in Instagram. 196–204. Atlantis Press.

- Wareham, J. (2020). Why some LGBT + people feel uneasy at the sight of NHS rainbow flags. Forbes. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2020/05/06/should-the-lgbt-community-call-out-nhs-appropriation-of-rainbow-flag/).

- Wiklund, C. (2022). Inclusive marketing: A study of Swedish female consumers’ perceptions of inclusive advertisements in the fashion industry. Retrieved from https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-197004.

- Wold, H. (1982). Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. Part, II, 2.

- Yousef, M., Rundle-Thiele, S., & Dietrich, T. (2021). Advertising appeals effectiveness: A systematic literature review. Health Promotion International, 38(4) https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab204

- Zhang, H., Sun, J., Liu, F., & Knight, J. (2014). Be rational or be emotional: Advertising appeals, service types and consumer responses. European Journal of Marketing, 48(11/12), 2105–2126. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2012-0613

- Zhu, B., Kowatthanakul, S., & Satanasavapak, P. (2019). Generation Y consumer online repurchase intention in Bangkok: Based on stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-04-2018-0071

Appendices

Appendix A.

Descriptive statistics.

Appendix B.

Measurement scales

Appendix C

Questionnaire

PART 1: surveyor’s information

Your gender:

Male

Female

Others

Your education:

Lower than high school

High school

College

Bachelor

Master

PhD

Which age group are you in?

From 18 to 26

From 27 to 35

From 36 to 45

Above 45

What is your nationality?

American

Vietnamese

Others

What is your current career?

Student

Lecturer

Civil Servants

Clerk, Officer

Start-up

Business Household, Business Owner

Homemaker/retirees

Employee

Others

PART 2: evaluate

To confirm that you have read the instructions carefully and focused on our survey, please skip the next question about how you feel, and you only choose the ‘Paper’ option to answer this question. Thank you for your concentration!

Please choose 1 word that describes your current feeling or state.

Angry

Anxious

Excited

Happy

Paper

Proud

Ashamed

—————————

Random assign:

Case 1:

Next, you will be asked to look carefully at some promotional images of a brand during Pride Month, then answer a few questions related to this image.

*Note: Pride Month is a month-long observance in celebration of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people-and the history, culture, and contributions of these people and their communities.

Case 2:

Next, you will be asked to look closely at some promotional images of an international brand and answer a few questions related to this image.

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with each of the following statements after viewing the ad above.

10. Advertising appeal

11. Self-expressive

12. Behavioral intention

THANK YOU FOR YOUR PRESTIOUS CONTRIBUTIONS!