Abstract

Prior research has examined the relationship between workplace ostracism with various work-related outcomes. However, relatively little is known about the mechanisms that link ostracism to work outcomes. This study uniquely contributes to the body of knowledge by examining the mechanisms through which workplace ostracism harms employees’ affective commitment. The study examines the roles of resource depletion and psychological safety as underlying psychological mechanisms that link workplace ostracism to affective commitment. A three-wave time-lagged data collected from employees (N = 271) of the service industry in Pakistan indicates that workplace ostracism may reduce employees’ psychological safety and contribute to resource depletion. Moreover, workplace ostracism reduces affective commitment by depleting employees’ psychological resources and psychological safety.

Introduction

Being ignored or overlooked by others is a common experience in all social contexts. These experiences are often studied under the ambit of mistreatment and specifically labelled as ‘ostracism’ (Williams, Citation2007). Workplace ostracism is a form of emotional abuse that includes ignoring, disregarding, hiding information, being silent when asked about something, not replying, and avoiding eye contact at work (Robinson et al., Citation2013). Workplace ostracism is a relatively tacit and covert mistreatment compared to other interpersonal mistreatments (e.g. abusive supervision, harassment, and bullying), which are more overt and visible (Buss, Citation1961). Consistently, the detrimental effects of workplace ostracism are expected to be greater than those of other mistreatments, such as workplace harassment (O’Reilly et al., Citation2015) and bullying (Williams & Nida, Citation2009). Moreover, the harmful effects of ostracism are not limited to individual health, absenteeism, depression, emotional energy, and insomnia (e.g. Jiang & Poon, Citation2021; Niu et al., Citation2016; Rabiul, Alam, et al., Citation2023) but organizations also suffer from low work engagement (Haldorai et al., Citation2020), lack of creativity (Tu, Cheng, et al., Citation2019), lower organizational citizenship behaviors (Wu et al., Citation2016), poor job performance (Choi, Citation2020), and conflicts among the victims of ostracism (Zaman et al., Citation2021). According to Hogan et al. (Citation2020), 43% of Irish workers experienced mistreatment, such as incivility, disrespect, being ignored, and being excluded in the workplace. Similarly, 33% and 12.9% of Chinese experienced workplace discrimination and victimization, respectively (Zhang, Citation2021). In addition, cultural differences may also contribute to the differential effects of mistreatment on employee outcomes. For example, Singaporean employees are less affected by mistreatments than Australian (Loh et al., Citation2021). In financial terms, the estimated cost incurred by organizations in terms of poor employee health, poor performance, or target delays goes up to 200 billion US dollars annually (Perrewe et al., Citation2015).

Preliminary research indicates that ostracism depletes cognitive regulatory resources (Leung et al., Citation2011) and social support (i.e. social resources), resulting in less commitment toward organizations (Mao et al., Citation2017). Similarly, a lack of supportive job resources creates a psychologically unsafe environment, thereby decreasing an individual’s capacity to cope with stress (Newman et al., Citation2017). Research also suggests that individuals with low self-efficacy (De Clercq et al., Citation2019) may not be able to cope with ostracism effectively. However, prior research has ignored the potential role of resource depletion and psychological safety in determining how workplace ostracism affects employees’ outcomes. In other words, the underlying mechanisms (e.g. resource depletion and psychological safety) through which workplace ostracism affects work outcomes remain largely unexplored. Furthermore, scholarship on workplace ostracism calls for more research on the causal mechanisms from a victim’s perspective (Howard et al., Citation2019; Sharma & Dhar, Citation2021). Specifically, there is a need to explore how workplace ostracism depletes personal resources (De Clercq et al., Citation2019). Examining the underlying causal mechanisms is important to enhance an understanding of the processes through which ostracism affects job outcomes, as it would help to address workplace ostracism. Moreover, the majority of the prior studies have been conducted in the developed Western settings. Therefore, more research is needed in the Eastern work contexts for a better understanding of the cross-cultural perspectives on workplace ostracism (Lyu & Zhu, Citation2019).

Consequently, this study attempts to address these gaps by investigating the effects of ostracism on affective commitment. Moreover, the study draws upon the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001) and examines how resource depletion and psychological safety act as the underlying mechanisms explaining the link of workplace ostracism with employees’ affective commitment. COR theory posits that individuals strive to acquire and maintain resources, and when faced with resource loss or threat, they may experience heightened stress and diminished well-being (Hobfoll, Citation2001; Rabiul, Alam, et al., Citation2023). In the context of workplace ostracism, the depletion of psychological resources is considered as a key mechanism through which this workplace mistreatment may detrimentally affect employee outcomes. Finally, the study examines these relationships in a developing Eastern context (i.e., Pakistan) to provide generalizability of ostracism research predominantly conducted in the Western work settings.

Review of literature and hypotheses

Workplace ostracism and resource depletion

Workplace ostracism is referred to as the ‘feeling of being ignored and excluded by others in the workplace’ (Ferris et al., Citation2008, p. 220). When an employee observes such behaviors in their surroundings, they search for the cause, and a subconscious self-analysis process starts. Consequently, personal resources, such as willpower, are the first to be depleted (Yan et al., Citation2014). Studies indicate that social interactions tend to improve work performance (Deepa et al., Citation2022). However, workplace ostracism can act as an interpersonal stressor (Chung, Citation2018; Williams, Citation2001) that may deplete the victims’ personal energies.

According to the COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018), resources possessed by an individual can be classified as tangible resources (e.g. car, assets, tools for work), environment- and context-specific resources (e.g. job span, seniority), individual/personal resources (e.g. knowledge, key skills, capacity), and energy resources (e.g. credit, time, mental energy). In various contexts, specifically when exposed to stressful situations, individuals need to maintain self-control and emotional balancing, which can deplete specific psychological and cognitive resources (Hagger et al., Citation2010). Research also suggests that stressful conditions tend to consume individuals’ psychological resources (Baumeister et al., Citation1998). The term ‘ego depletion’ refers to the psychological conditions of overutilization of this limited resource, making the individual vulnerable to multiple challenging situations and lessened functioning (Ciarocco et al., Citation2001). Employees facing ostracism undergo personal and social resource erosion, while controlling for resource loss, they tend to engage in protective mechanisms (Anasori et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, Baumeister et al. (Citation2005) found that the ability to maintain self-control was lower among individuals who were exposed to social exclusion. Similarly, workplace exclusion negatively affects employees’ organization-based self-esteem (Sharp et al., Citation2020). In addition, the depletion of self-control reduces employees’ self-regulatory capacities (e.g. the capability to control thoughts and behaviors). When individuals experience workplace ostracism, they direct their energy and attention toward coping with these stressful demands, resulting in the loss of resources (Anjum et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, workplace ostracism reduces social ties causing resource loss (Hua et al., Citation2023). Therefore, we suggest that the exposure to workplace ostracism may act as a stressor and deplete personal and psychological resources. Consequently, we propose:

Hypothesis 1:

Workplace ostracism is positively related to resource depletion.

Mediating role of resource depletion

Affective commitment refers to ‘employees’ emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in, the organization’ (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990, p. 1). Earlier studies indicate that mistreatments (e.g. incivility) have a negative effect on affective commitment (Taylor et al., Citation2012). Workplace ostracism may also harmfully affect employee association with their organization because employees who feel ostracized may reduce their contributions towards the organization (Ferris et al., Citation2015). When individuals are exposed to workplace ostracism, their association with the organization may be reduced (Wu et al., Citation2016). Similarly, their experience of thriving at work reduces (Han & Hwang, Citation2021) because of a lack of belongingness with the organization (Haldorai et al., Citation2020).

COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001) indicates that stressful situations (e.g., workplace ostracism) may deplete employees’ psychological resources, as they may spend their time and energy coping with stressors. The theory further states that when resources run low or run out, people often go into a defensive mode to protect themselves which may make them act aggressively or behave irrationally (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Thus, to prevent further loss of resources, victims may disengage and reduce their affective commitment. Therefore, we suggest that resource depletion mediates the effects of workplace ostracism on affective commitment. In other words, workplace ostracism, as a social stressor, may lead to resource depletion among the victims. Such depletion of psychological resources may in turn dampen the victims’ affective commitment. Consequently, we suggest:

Hypothesis 2:

Resource depletion mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism and affective commitment.

Workplace ostracism and psychological safety

Psychological safety refers to ‘the perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in particular context such as a workplace’ (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014, p. 23). When exposed to workplace ostracism, employees lack the social contact, trust, and support required from others. Consequently, it affects learning behavior and information sharing (Wang, Qin, et al., Citation2021). The peers and organizational support play a significant role in the workplace (Newman et al., Citation2017) as psychological safety largely depends on the support from colleagues, their caring attitudes, and the trust level among colleagues (Zhang et al., Citation2010). Similarly, a lack of such support may threaten psychological safety.

Furthermore, exposure to workplace ostracism is a critical workplace stressor (Glazer et al., Citation2021) that may foster perceptions of unsafe work environments. Ostracized individuals have a higher risk of psychological depression, anxiety, and aggression (Twenge et al., Citation2007). Research indicates that a lack of psychological safety arises from the presence of risk and discomfort in the environment (Holley & Steiner, Citation2005). Interpersonal threats, humiliation, fearfulness, ignorance, expulsion, indifference, lack of peer support, and unwillingness to give information and explanations may result in a lack of psychological safety among victims. Similarly, psychological detachment is caused by workplace ostracism, which leads to employees’ unsafe behavior (Chen & Li, Citation2020).

Furthermore, the COR perspective indicates that socioemotional resources contribute towards psychological safety (Lee, Citation2021). However, situations of conflict, exclusion, boycott, and a lack of support from the coworkers act as a social stressor, causing loss of psychological resources. Additionally, people’s resources depend on the environment they’re in, which can either help them grow and thrive or make it hard for them to create and maintain resources (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Thus, employees who are more sensitive towards workplace ostracism are more likely to develop negative emotions (Wang, Qin, et al., Citation2021), eventually forming negative perceptions of their colleagues and organization. They may overthink about a trivial act or consider the omission of an act by a colleague as hostile. In such an environment, they feel unsafe and ostracized in their work environment. Therefore, it is argued that workplace ostracism may reduce employees’ perceptions of psychological safety. Consequently, we suggest:

Hypothesis 3:

Workplace ostracism is negatively related to psychological safety.

Mediating role of psychological safety

We further explore whether workplace ostracism influences affective commitment through psychological safety. Previous research suggests that psychological strain is an important mechanism between workplace mistreatment and its consequences (Liang, Citation2020). COR theory posits that individuals’ resources are shaped by the surroundings they’re in, which can either support their growth and well-being or hinder their ability to create and maintain resources (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018).

Commonly, safe and supportive social environments help people maintain and gain more resources (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). The employees’ perceptions of psychosocial climate and psychological resources play a significant role in their innovative contributions and overall well-being (Brunetto et al., Citation2021). COR theory also indicates that many resources, such as social support can reduce the negative effects of unfavorable social environments on individuals (Van Woerkom et al., Citation2016). Similarly, social support diminishes the detrimental impact of psychological violence on affective commitment (Courcy et al., Citation2019).

Supervisors’ and coworkers’ support are the two most important workplace relationships for employees (Tu, Lu, et al., Citation2019; Wang, Qin, et al., Citation2021). The behavior of supervisors and coworkers develops a deeper commitment towards the organization (Tenbrunsel et al., Citation2003). According to the COR perspective, the availability of social support and social interaction, as social resources, helps to enhance an intrinsic resource, such as psychological safety (Singh et al., Citation2018). Therefore, in case of employees, who feel psychologically safe, have high energy levels and emotional resources, and consequently, their involvement and dedication towards work is also high (Rabiul, Karatepe, et al., Citation2023). However, when faced with workplace ostracism, the victims may feel psychologically unsafe, which in turn may dampen their affective commitment. Consequently, we suggest:

Hypothesis 4:

Psychological safety mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism and affective commitment.

Methods

Population and sample

The study used a time-lagged field survey to reduce the issues related to common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). We collected data using self-administered surveys. The survey forms were distributed among 600 full-time employees from the services sector in Pakistan. Service industries, such as telecommunication companies, banks, and educational institutions in the Pakistani context provide more opportunities for interaction among employees, which likely enhances the chances of workplace ostracism (Jahanzeb & Fatima, Citation2018). In addition, these organizations have reported instances of workplace ostracism (Anjum et al., Citation2022). The surveys were randomly distributed among the participants and the participation was voluntary. We attached a cover letter with each survey assuring the respondents’ data confidentiality and explaining the purpose of this study. The survey was in English as it is the official language in Pakistan and previous studies in the region have also used English surveys (Abbas & Bashir, Citation2020; Bouckenooghe et al., Citation2017; Fatima et al., Citation2023; Malik et al., Citation2023).

Data collection

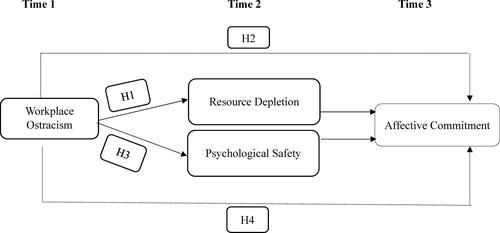

The theoretical model is presented in . To test the model, a three-wave time-lagged design was used. At Time 1, data on workplace ostracism and employee demographics were collected. After three weeks, at Time 2, employees responded to the items related to resource depletion and psychological safety. Finally, another three weeks later, at Time 3, respondents were asked to provide data on their affective commitment.

At Time 1, around 600 questionnaires were distributed, of which we received 550 completed surveys (response rate of 91.67%). Of these 550 employees, 400 completed survey forms were received after three weeks at Time 2 (response rate: 72.72%). Finally, after another three weeks, at Time 3, we received around 300 survey forms. After screening for missing data and incomplete responses, the final sample size was 271, yielding a response rate of 45%.

Measures

Workplace ostracism

Workplace ostracism was gauged with a 17-item revised Workplace Ostracism Scale (adapted from Ferris et al., Citation2008: Fiset & Bhave, Citation2019). A few sample items used include ‘Others ignore you at work’, ‘Others leave the area when you arrive’, and ‘Your greetings have gone unanswered at work’. The responses were taken on a 7-point Likert-type scale with anchors ranging from 1 = Never to 7 = Always. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for this scale was 0.89.

Resource depletion

A 5-item scale developed by Deng et al. (Citation2016) was used to measure resource depletion. The response anchors ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Some sample items used were as follows: ‘I feel lazy’, and ‘I feel like my willpower is gone’. The alpha reliability for this scale was 0.89.

Psychological safety

We used a 7-item scale developed by Edmondson (Citation1999) to measure psychological safety. The responses were taken on a 5-point Likert-type scale with anchors ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The sample items included, ‘Members of this organization are able to bring up problems and tough issues’, and ‘It is safe to take a risk in this organization’. The alpha reliability of this scale was 0.76.

Affective commitment

Affective commitment was measured using the Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) instrument with five items. Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The anchors ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The sample items included, ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization’, and ‘I really feel as if this organization’s problem is my own’. The alpha reliability of this scale was 0.90.

Results

Reliability, validity, and correlations

First, to gauge the measurement model, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2001). Discriminant validity was established by conducting CFA on various models. These results are reported in . First, the CFA of the workplace ostracism revised scale was conducted to validate the four-dimensional model of workplace ostracism. As reported in , the CFA result showed that the indices for a four-factor model (CMIN/df = 2.03; IFI = .94; TLI = .92; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .06) were better than a one-factor model (CMIN/df = 5.36; IFI = .74; TLI = .70; CFI = .73; RMSEA = .13). We ran another CFA and tested a second-order one-factor model. The indices for a second-order one-factor model were slightly better than the four-factor structure (CMIN/df = 1.93; IFI = .95; TLI = .94; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .06). Therefore, for the sake of parsimony, the second-order factor was considered and an aggregate measure for workplace ostracism was used.

Table 1. Results of confirmatory factor analyses (measurement model).

Finally, to establish the discriminant validity of all four variables (workplace ostracism, resource depletion, psychological safety, and affective commitment), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to compare a four-factor structure with a single factor structure. The CFA results revealed that a four-factor model provided a good fit to the data (CMIN/df = 1.73, IFI = .92; TLI = .91; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .05) as compared to a one-factor model (CMIN/df = 4.07, IFI = .64, TLI = .61, CFI = .64, RMSEA = .11), thus establishing discriminant validity of the study constructs.

reports the means, standard deviations, correlations, and scale reliabilities for the variables. The correlations between the study variables were in the expected direction. Workplace ostracism was found to be positively related to resource depletion (r = .66, p < .01) and negatively related to affective commitment (r = −.53, p < .01). Similarly, resource depletion was negatively related to affective commitment (r = −.44, p < .01). Workplace ostracism was found to be negatively related to psychological safety (r = −.48, p < .01). However, psychological safety was found to have positive relationship with affective commitment (r = .45, p < .01).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities.

Hypotheses testing

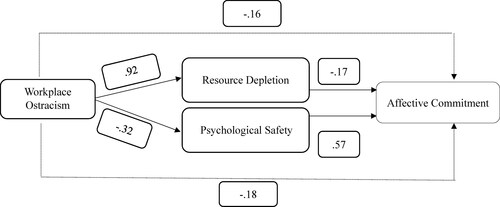

To investigate the direct and indirect effects, the study utilized PROCESS macro which uses bootstrap methods (Hayes, Citation2013). presents the results for hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2. We also present the results in . Hypothesis 1 predicted that workplace ostracism would have a positive effect on resource depletion. The results in show that workplace ostracism had a positive relationship with resource depletion (B = .92, t = 14.36, p < .001), thus supporting hypothesis 1. further shows that resource depletion has a negative effect on affective commitment when controlling for ostracism (B = −.17, t = −2.44, p < .01). Further, Hypothesis 2 predicted a mediation effect, whereby the relationship between workplace ostracism and affective commitment was proposed to be mediated through resource depletion. shows that workplace ostracism was significantly related to affective commitment when resource depletion was controlled for (B = −.61, t = −6.13, p < .000). Moreover, the bootstrapped indirect effect of workplace ostracism on affective commitment through resource depletion was also significant (B = −.16), as the bootstrapped 95% CI did not contain zero (−.30, −.02). This suggests that a partial mediation exists between workplace ostracism and affective commitment. Overall, these findings support hypothesis 2 and suggest that workplace ostracism has a negative indirect effect on affective commitment through resource depletion.

Figure 2. Hypothesis testing results. Note: Dotted lines reflect mediation (indirect) effects. Significant Beta values are presented.

Table 3. Mediation effects of resource depletion (Time 2) in the relationship between workplace ostracism (Time 1) and affective commitment (Time 3).

presents the regression results for hypothesis 3 and hypothesis 4. Hypothesis 3 predicted that workplace ostracism would have a negative effect on psychological safety. As shown in , workplace ostracism has a negative effect on psychological safety (B = −.32, t = −8.85, p < .000), thus supporting hypothesis 3. Also, psychological safety had a positive effect on affective commitment when controlling for ostracism (B = .57, t = 4.61, p < .000). Similarly, workplace ostracism had a negative effect on affective commitment even when psychological safety was controlled (B = −.59, t = −7.11, p < .000). Finally, hypothesis 4 predicted a mediation effect, whereby the relationship between workplace ostracism and affective commitment was proposed to be mediated by psychological safety. As shown in , workplace ostracism had an indirect negative and significant relationship with affective commitment through psychological safety, as the bootstrapped 95% CI did not contain zero (−.28, −.09). Overall, these findings supported hypothesis 3 and hypothesis 4, and suggested that workplace ostracism both directly and indirectly (through psychological safety) affected affective commitment.

Table 4. Mediation effects of psychological safety (Time 2) in the relationship between workplace ostracism (Time 1) and affective commitment (Time 3).

Discussion

Drawing on COR theory, this study examines how workplace ostracism drains individuals’ resources, which leads to diminished affective commitment. This study contributes to the literature by showing that workplace ostracism has a positive relationship with resource depletion. Respondents who reported a high level of workplace mistreatment also reported high resource depletion. Workplace ostracism seems to deplete resources (such as self-esteem, belongingness needs, self-control, etc.), consequently leaving individuals emotionally drained and with reduced commitment.

Consistent with COR theory, our findings suggest that individual resources are depleted because of the exposure to stressors, such as workplace ostracism. Previous studies indicate a negative relationship between workplace ostracism and job attitudes, such as job satisfaction (e.g. Chung & Kim, Citation2017), and a positive effect on turnover intentions (Wang, Du, et al., Citation2021). Consistently, the current study found a negative relationship between workplace ostracism and affective commitment. These findings are noteworthy for organizations that want to boost their employees’ affective commitment. COR theory suggests that individuals possess a limited set of key resources (physical, personal, and social) that help them handle job demands or stressful situations (Hobfoll, Citation2001). We found that workplace ostracism is a covert mistreatment that threatens employees’ psychological safety, thereby reducing a critical psychological resource. Psychological safety can help to promote desirable behaviors in the workplace (Robinson et al., Citation2013). However, workplace mistreatments or interpersonal stressors (e.g., workplace ostracism) damage these important psychological resources.

Furthermore, the findings of the current study extend the work of Wang, Du, et al. (Citation2021) by providing an explanation for workplace ostracism causing resources to deplete and threaten psychological safety, consequently resulting in decreased affective commitment. These findings suggest that the environments where there is high workplace ostracism may damage both psychological safety and other personal resources. Consistent with COR, our study explains that resource depletion due to workplace ostracism further reduces employees’ affective commitment. Additionally, by adopting a resource perspective, this study enriches the workplace ostracism literature by providing an additional account of mediating paths and explaining its harmful effect on employees’ commitment. Finally, our findings suggest that workplace ostracism may both directly and indirectly affect affective commitment. In other words, workplace ostracism is a harmful interpersonal stressor that may directly or indirectly affect important job outcomes.

Practical implications

This study supports the critical role that individual resources play in enhancing affective commitment. Resources related to self-control and social support are necessary for affective commitment. A psychologically safe organizational environment is likely to provide social support and relational resources to employees, enhancing their other resources and making them more committed towards their employers. Additionally, employees may be less affected by ostracism when working conditions are characterized by trust and appreciation for risk taking. Similarly, this study suggests that managers should especially consider mistreatments that are ambiguous in nature and not regulated by any policy, such as ostracism. More specifically, managers should be cognizant of acts of ostracism and deal with them immediately to protect employees from resource depletion and lack of psychological safety. Moreover, managers should make efforts to maintain a good working environment where employees do not ostracize their colleagues and maintain positive work relationships. Managers should also develop training interventions to guide employees about how to avoid discriminatory behaviors that lead to feelings of ostracism. For example, employees should be made aware of the problem that talking in a language, that is alien to others, may develop feelings of ostracism among others.

Similarly, hiding information and not replying to emails and official chats may also trigger feelings of ostracism among others. Therefore, such issues should be regulated by policies to ensure employees do not exhibit such counterproductive acts. Finally, given the evidence that psychological safety leads to affective commitment, managers should ensure a psychologically safe work environment to foster affective commitment among the organizational members.

Limitations and future research direction

Similar to other studies, this study has some limitations. First, although this study used a time-lagged design to avoid method bias issues, longitudinal studies or experimental studies are more helpful in examining theoretically causal models. Future research may use these designs to examine the intricate relationship between workplace ostracism and job outcomes. Second, our study sample includes a variety of service industry organizations. Future research may replicate these findings in other sectors as well, such as the manufacturing sector. Third, this study focuses only on employees’ affective commitment. Future research may include other important work behaviors, such as creativity and job performance. Finally, future research may also examine potential moderators (e.g. mental resilience and psychological capital) for the effects of ostracism on work outcomes.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethical review committee of the authors’ university. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution.

Informed consent

Participants were informed about the study’s procedures, risks, benefits, and other aspects before their participation. Only those who explicitly provided their consent were allowed to participate in the study.

Author contributions

Shahida Noor presented the idea. Dr. Muhammad Abbas encouraged her to investigate and develop the theoretical background for the study. He guided Shahida Noor at every step of the research. Shahida Noor did the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. The draft went through revisions under the supervision of Dr. Muhammad Abbas, whereby revisions were done critically for intellectual content. The final version is approved by both authors to be published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data may be available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shahida Noor

Shahida Noor ([email protected]) is a PhD scholar at FAST School of Management, Islamabad. Moreover, she has seven years of teaching experience. She has an excellent academic record. Ms. Noor received gold medals and high achievement awards throughout her academic discourse. She has presented her research at multiple national and international conferences. Her research interests include workplace mistreatments, job stressors and career counseling.

Muhammad Abbas

Dr. Muhammad Abbas ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor at FAST School of Management, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan. Dr. Abbas holds a PhD in Management. He has over twelve years of experience in teaching and research. His publications appear in Journal of Management, Journal of Business Ethics and Journal of Business & Psychology, among others. His primary research interests include positive OB, psychological capital, workplace mistreatment, AI in HRM and generative AI usage.

References

- Abbas, M., & Bashir, F. (2020). Having a green identity: Does pro-environmental self-identity mediate the effects of moral identity on ethical consumption and pro-environmental behavior? Studies in Psychology, 41(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02109395.2020.1796271

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Anasori, E., Bayighomog, S. W., De Vita, G., & Altinay, L. (2021). The mediating role of psychological distress between ostracism, work engagement, and turnover intentions: An analysis in the Cypriot hospitality context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102829

- Anjum, M. A., Liang, D., Ahmed, A., & Parvez, A. (2022). Understanding how and when workplace ostracism jeopardizes work effort. Management Decision, 60(7), 1793–1812. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-02-2021-0195

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252

- Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(4), 589–604. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589

- Bouckenooghe, D., Raja, U., Butt, A. N., Abbas, M., & Bilgrami, S. (2017). Unpacking the curvilinear relationship between negative affectivity, performance, and turnover intentions: The moderating effect of time-related work stress. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(3), 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.10

- Brunetto, Y., Saheli, N., Dick, T., & Nelson, S. (2021). Psychosocial safety climate, psychological capital, healthcare SLBs’ wellbeing and innovative behaviour during the COVID 19 pandemic. Public Performance & Management Review, 45(4), 751–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2021.1918189

- Buss, A. H. (1961). The psychology of aggression. Wiley.

- Chen, Y., & Li, S. (2020). Relationship between workplace ostracism and unsafe behaviors: The mediating effect of psychological detachment and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports, 123(2), 488–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118813892

- Choi, Y. (2020). A study of the influence of workplace ostracism on employees’ performance: Moderating effect of perceived organizational support. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 29(3), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-09-2019-0159

- Chung, Y. W. (2018). Workplace ostracism and workplace behaviors: A moderated mediation model of perceived stress and psychological empowerment. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 31(3), 304–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1424835

- Chung, Y. W., & Kim, T. (2017). Impact of using social network services on workplace ostracism, job satisfaction, and innovative behavior. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(12), 1235–1243. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2017.1369568

- Ciarocco, N. J., Sommer, K. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Ostracism and ego depletion: The strains of silence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(9), 1156–1163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201279008

- Courcy, F., Morin, A. J., & Madore, I. (2019). The effects of exposure to psychological violence in the workplace on commitment and turnover intentions: The moderating role of social support and role stressors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(19), 4162–4190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516674201

- De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2019). Workplace ostracism and job performance: Roles of self-efficacy and job level. Personnel Review, 48(1), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2017-0039

- Deepa, V., Baber, H., Shukla, B., Sujatha, R., & Khan, D. (2022). Does lack of social interaction act as a barrier to effectiveness in work from home? COVID-19 and gender. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 10(1), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-11-2021-0311

- Deng, H., Wu, C. H., Leung, K., & Guan, Y. (2016). Depletion from self‐regulation: A resource‐based account of the effect of value incongruence. Personnel Psychology, 69(2), 431–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12107

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Fatima, S., Abbas, M., & Hassan, M. M. (2023). Servant leadership, ideology-based culture and job outcomes: A multi-level investigation among hospitality workers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 109, 103408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103408

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348–1366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012743

- Ferris, D. L., Lian, H., Brown, D. J., & Morrison, R. (2015). Ostracism, self-esteem, and job performance: When do we self-verify and when do we self-enhance? Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0347

- Fiset, J., & Bhave, D. P. (2019). Mind your language: The effects of linguistic ostracism on interpersonal work behaviors. Journal of Management, 47(2), 430–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319833445

- Glazer, S., Farley, S. D., & Rahman, T. T. (2021). Performance consequences of workplace ostracism. In Workplace ostracism (pp. 159–188). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hagger, M. S., Wood, C., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 495–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019486

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., Phetvaroon, K., & Li, J. J. (. (2020). Left out of the office “tribe”: The influence of workplace ostracism on employee work engagement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(8), 2717–2735. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0285

- Han, M. C., & Hwang, P. C. (2021). Who will survive workplace ostracism? Career calling among hotel employees. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.09.006

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Hogan, V., Hodgins, M., Lewis, D., Maccurtain, S., Mannix-McNamara, P., & Pursell, L. (2020). The prevalence of ill-treatment and bullying at work in Ireland. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(3), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-09-2018-0123

- Holley, L. C., & Steiner, S. (2005). Safe space: Student perspectives on classroom environment. Journal of Social Work Education, 41(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2005.200300343

- Howard, M. C., Cogswell, J. E., & Smith, M. B. (2019). The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 577–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000453

- Hua, C., Zhao, L., He, Q., & Chen, Z. (2023). When and how workplace ostracism leads to interpersonal deviance: The moderating effects of self-control and negative affect. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113554

- Jahanzeb, S., & Fatima, T. (2018). How workplace ostracism influences interpersonal deviance: The mediating role of defensive silence and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(6), 779–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9525-6

- Jiang, Y., & Poon, K. T. (2021). Stuck in companionless days, end up in sleepless nights: Relationships between ostracism, rumination, insomnia, and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 42(1), 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01474-4

- Lee, H. (2021). Changes in workplace practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of emotion, psychological safety and organisation support. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 8(1), 97–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-06-2020-0104

- Leung, A. S., Wu, L. Z., Chen, Y. Y., & Young, M. N. (2011). The impact of workplace ostracism in service organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 836–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.01.004

- Liang, H. L. (2020). How workplace bullying relates to facades of conformity and work–family conflict: The mediating role of psychological strain. Psychological Reports, 123(6), 2479–2500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294119862984

- Loh, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Loi, N. M. (2021). Workplace incivility and work outcomes: Cross‐cultural comparison between Australian and Singaporean employees. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59(2), 305–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12233

- Lyu, Y., & Zhu, H. (2019). The predictive effects of workplace ostracism on employee attitudes: A job embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3741-x

- Malik, M., Abbas, M., & Imam, H. (2023). Knowledge-oriented leadership and workers’ performance: Do individual knowledge management engagement and empowerment matter? International Journal of Manpower, 44(7), 1382–1398. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2022-0302

- Mao, Y., Liu, Y., Jiang, C., & Zhang, I. D. (2017). Why am I ostracized and how would I react? A review of workplace ostracism research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(3), 745–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9538-8

- Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

- Niu, G. F., Sun, X. J., Tian, Y., Fan, C. Y., & Zhou, Z. K. (2016). Resilience moderates the relationship between ostracism and depression among Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 77–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.059

- O’Reilly, J., Robinson, S. L., Berdahl, J. L., & Banki, S. (2015). Is negative attention better than no attention? The comparative effects of ostracism and harassment at work. Organization Science, 26(3), 774–793. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0900

- Perrewe, P. L., Halbesleben, J. R., & Rosen, C. C. (2015). Mistreatment in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Rabiul, M. K., Alam, M. M., & Karim, R. A. (2023). Workplace ostracism and service-oriented behaviour: Employees’ workload and emotional energy. Management Decision. Ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2023-1299

- Rabiul, M. K., Karatepe, O. M., Al Karim, R., & Panha, I. M. (2023). An investigation of the interrelationships of leadership styles, psychological safety, thriving at work, and work engagement in the hotel industry: A sequential mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 113,103508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2023.103508

- Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J., & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. Journal of Management, 39(1), 203–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312466141

- Sharma, N., & Dhar, R. L. (2021). From curse to cure of workplace ostracism: A systematic review and future research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 32(3), 100836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2021.100836

- Sharp, O. L., Peng, Y., & Jex, S. M. (2020). Exclusion in the workplace: A multi-level investigation. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-07-2019-0097

- Singh, B., Shaffer, M. A., & Selvarajan, T. T. (2018). Antecedents of organizational and community embeddedness: The roles of support, psychological safety, and need to belong. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2223

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- Taylor, S. G., Bedeian, A. G., & Kluemper, D. H. (2012). Linking workplace incivility to citizenship performance: The combined effects of affective commitment and conscientiousness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(7), 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.773

- Tenbrunsel, A. E., Smith-Crowe, K., & Umphress, E. E. (2003). Building houses on rocks: The role of the ethical infrastructure in organizations. Social Justice Research, 16(3), 285–307. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025992813613

- Tu, M., Cheng, Z., & Liu, W. (2019). Spotlight on the effect of workplace ostracism on creativity: A social cognitive perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01215

- Tu, Y., Lu, X., Choi, J. N., & Guo, W. (2019). Ethical leadership and team-level creativity: Mediation of psychological safety climate and moderation of supervisor support for creativity. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 551–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3839-9

- Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Bartels, J. M. (2007). Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.56

- Van Woerkom, M., Bakker, A. B., & Nishii, L. H. (2016). Accumulative job demands and support for strength use: Fine-tuning the job demands-resources model using conservation of resources theory. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000033

- Wang, D., Qin, Y., & Zhou, W. (2021). The effects of leaders’ prosocial orientation on employees’ organizational citizenship behavior–the roles of affective commitment and workplace ostracism. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1171–1185. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S324081

- Wang, Z., Du, J., Yu, M., Meng, H., & Wu, J. (2021). Abusive supervision and newcomers’ turnover intention: A perceived workplace ostracism perspective. The Journal of General Psychology, 148(4), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2020.1751043

- Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. Guilford Press.

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

- Williams, K. D., & Nida, S. A. (2009). Is ostracism worse than bullying. In Bullying, rejection, and peer victimization: A social cognitive neuroscience perspective (pp. 279–296). Springer Publishing.

- Wu, C. H., Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., & Lee, C. (2016). Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: An organizational identification perspective. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000063

- Yan, Y., Zhou, E., Long, L., & Ji, Y. (2014). The influence of workplace ostracism on counterproductive work behavior: The mediating effect of state self-control. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(6), 881–890. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.6.881

- Zaman, U., Nawaz, S., Shafique, O., & Rafique, S. (2021). Making of rebel talent through workplace ostracism: A moderated-mediation model involving emotional intelligence, organizational conflict and knowledge sharing behavior. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1941586. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1941586

- Zhang, H. (2021). Workplace victimization and discrimination in China: A nationwide survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), 957–975. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517729403

- Zhang, Y., Fang, Y., Wei, K. K., & Chen, H. (2010). Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. International Journal of Information Management, 30(5), 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.02.003