Abstract

The International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 15, ‘Revenue from Contracts with Customers’, became effective for National Health Service (NHS) bodies from the annual period beginning 1 April 2018. NHS Foundation Trusts, as part of UK public sector organisations, adopted IFRS for their 2009/2010 financial statements to improve the consistency and comparability of financial reports globally and to follow best practices from the private sector. The implementation of new or revised accounting standards can have both intended and unintended effects. Understanding these effects is essential for healthcare policymakers and managers to navigate the changes this standard brings. This study analyses the impact of IFRS 15 on the financial performance of University and Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trusts, considering both financial and management accounting perspectives. The research initially outlines the expected effects of the new revenue recognition standard. It then addresses unique considerations within the healthcare sector before empirically evaluating the significance of annual financial performance changes after IFRS 15 implementation, specifically in terms of accounting effects. This exploration paves the way for discussions on further anticipated effects. The article uses Friedman’s test to analyse the impact of IFRS 15 on total operating income for a sample of 33 University and Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trusts and finds that the adoption of the new revenue recognition standard had a significant impact on this item, i.e. financial performance was affected, which is classified as an unintended effect.

1. Introduction

The implementation of IFRS 15 ‘Revenue from Contracts with Customers’ marks a significant shift in global financial reporting, emphasising transparency, consistency and comparability across borders. IFRS 15 establishes a standardised framework for revenue recognition, facilitating clearer communication of financial information, enhancing investor confidence and supporting informed decision making. Enhanced relevance, usefulness and quality of information classified as outputs within intended effects of IFRS 15 implementation enable this (Osma et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, harmonising accounting standards on a global scale reduces the complexity and cost associated with cross-border transactions, thereby promoting international trade and investment.

The aim of this article is to examine the impact of IFRS 15 adoption on performance measurement in healthcare. It simultaneously classifies it among the described effects of IFRS 15 adoption, distinguishes between intended and unintended effects, and explores the relationship between them. IFRS 15 was intended to enhance the relevance, usefulness, and quality of information for investors to make informed decisions in financial accounting. However, unintended effects occurred in performance measurement changes, which were classified as accounting effects, along with real effects that affected actual performance, managerial decision-making, and management control systems (MCSs). The implementation of this revenue standard has led to changes in MCS, highlighting the interdependence between financial and management accounting. This article contributes to both financial reporting and earnings management literature, as well as literature on the interdependence of financial and management accounting.

With any new or amended accounting standard, the way assets, liabilities, income and expenses are recognised and measured could be revised. This is associated with accounting effects and could affect performance measurement as an unintended effect of IFRS 15 (Osma et al., Citation2023). If these effects are significant, management might communicate the effects to stakeholders (information effects) (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020). As performance is a topic that permeates contemporary societies, it is used to assess the quality of individual and collective efforts (Corvellec, Citation2018). Thus, organisations are not only required to perform, but also to communicate their achievements to key stakeholders (Micheli & Mari, Citation2014). Thereby this could have capital market effects from the perspective of equity and debt markets and could also involve pressure to maintain or improve performance and financial position (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020). Additionally, there is a belief among CFOs that reported earnings, rather than cash flows, is the primary metric used by external stakeholders, which may lead to the management of reported results to enhance the firm’s reputation with external parties. This is also demonstrated by real earnings management (REM) (Bereskin et al., Citation2018) as a part of the real effects of corporate disclosure and reporting (Leuz & Wysocki, Citation2016). REM could be observed from either a signalling perspective, when managers signal private information to capital market participants manifested through positive future operating performance (Gunny, Citation2010), or a managerial opportunistic perspective, which increases information risk because such opportunistic actions disguise the true economic performance (Roychowdhury, Citation2006).

For this reason, performance measurement, represented by both financial and non-financial measures, is a major issue for both for-profit and non-profit organisations, not excluding those in the healthcare sector. Moreover, despite the primary focus of public healthcare organisations on prevention and health promotion of the entire population, they are under increasing pressure to apply effective management tools and associated performance measures (Grigoroudis et al., Citation2012). There also have been numerous academic discussions on whether financial (objective) measures are sufficient for performance measurement, or if they should be replaced with non-financial (subjective) ones or just complemented by others (Hult et al., Citation2008; Meier & O’Toole, Citation2013; Shea et al., Citation2012; Singh et al., Citation2016).

Since ‘revenue is a crucial number to financial statements’ users in evaluating the financial performance of the entity’ (Yassin et al., Citation2022, p. 81), in compliance with previous research, this article concerns itself with one of the latest external reporting regulatory changes, namely the adoption of IFRS 15 ‘Revenue from Contracts with Customers’ and its impact on financial performance measurement. This revenue standard is expected to give clearer guidance on revenue recognition for all entities with contracts with customers, while reducing the potential for earnings management (Malikov et al., Citation2019). It is also expected that the introduction of IFRS 15 would not only have direct effects, but also real effects in the manner in which the business operates, cash flow changes and implementation and application costs (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020). As there is a pressure involved not only on healthcare delivery performance but also on financial performance both from profitmaking and finance sustainability perspectives, the healthcare industry was chosen. The UK setting was selected because every public hospital under NHS Foundation Trusts adopted IFRS for their 2009/10 financial statements there ‘to bring benefits in consistency and comparability between financial reports in the global economy and to follow private sector best practice’ (HM Treasury, Citation2007, para. 6.59). This provided a good ground for a sufficient sample collection in the healthcare sector. Another good reason to choose a healthcare setting is that NHS Foundation Trusts were proven to engage in earnings management manipulation in the past (Anagnostopoulou & Stavropoulou, Citation2021; Ballantine et al., Citation2007), and therefore the adoption of IFRS 15 is expected from to prevent earnings management practices.

IFRS 15 is expected to initially improve several aspects of this industry in the UK, being beneficial for NHS bodies (DHSC, Citation2019b). One of the primary aspects is the standardisation of revenue recognition practices, as before the implementation of IFRS 15, UK healthcare organisations may have used different methods to recognise revenue from patient services, leading to inconsistency and difficulty in comparing financial statements. With the adoption of IFRS 15, these organisations now follow a standardised approach to revenue recognition, ensuring consistency and comparability across the industry.

Another aspect is enhanced transparency in contract terms, since IFRS 15 requires UK healthcare organisations to provide detailed disclosures about contract terms, including performance obligations, variable consideration and contract modifications. For example, a healthcare organisation may have previously bundled services in a way that made it unclear when revenue should be recognised. With IFRS 15, they are now required to clearly define each performance obligation within the contract, leading to greater transparency and understanding of revenue recognition practices.

Simultaneously, it brings better management of contract modifications, because under IFRS 15, UK healthcare organisations must assess whether contract modifications represent separate contracts or changes to existing contracts, with corresponding implications for revenue recognition. For instance, if a patient requests additional services halfway through a treatment plan, the organisation needs to determine whether this constitutes a separate performance obligation. This clarity helps organisations manage contract modifications more effectively and ensure accurate revenue recognition.

A further aspect concerns changes in revenue recognition timing, as IFRS 15 requires revenue to be recognised when control of the goods or services is transferred to the customer, which may result in changes in the timing of revenue recognition for healthcare services. Recognition of bundled services is a significant factor in healthcare organisations, where bundled services often include multiple components such as medical procedures, consultations, and follow-up care. According to IFRS 15, these bundled services may need to be separated and recognised separately if they represent distinct performance obligations. This could potentially impacti the timing and amount of revenue recognised. Healthcare contracts may involve variable consideration, such as discounts, rebates, or performance bonuses. IFRS 15 requires estimation and adjustment of variable consideration, which could affect the amount and timing of revenue recognition.

Following is an aspect related to improvement of decision-making on pricing strategies, since IFRS 15 requires UK healthcare organisations to consider the impact of variable consideration, such as discounts or bonuses, on the transaction price and revenue recognition. For example, a healthcare organisation may offer volume discounts to insurers based on the number of patients referred. Accurately estimating and recognising the impact of these discounts under IFRS 15 enables organisations to make more informed decisions about pricing strategies and contract negotiations.

Regarding the impact on financial statements aspect, the implementation of IFRS 15 may result in changes in the presentation of financial statements, including adjustments to revenue figures and related disclosures. For instance, IFRS 15 introduces more detailed disclosure requirements regarding revenue recognition policies, contract balances and performance obligations. Healthcare organisations need to provide comprehensive disclosures to meet these requirements, which may involve additional effort and resources.

An additional aspect brings increased comparability with international peers, which means that by adopting IFRS 15, UK healthcare organisations align their revenue recognition practices with international accounting standards, making it easier for investors, creditors and regulators to compare their financial performance with organisations operating in other countries. This alignment enhances the organisation’s credibility and attractiveness to global stakeholders, potentially lowering the cost of capital and increasing access to investment opportunities.

In particular, while the transition to IFRS 15 may require initial adjustments and resource allocation, the benefits include greater transparency, improved financial management and alignment with international accounting standards.

However, implementing IFRS 15 in the healthcare industry poses several challenges, including complex revenue streams from multiple sources, such as patient services, insurance reimbursements, government funding and grants. Determining when and how to recognise revenue from these diverse sources under the new standard can be challenging, particularly when contracts involve bundled services or variable consideration. Another challenge lies within contractual arrangements with patients, insurers and other parties, which may involve complex terms and conditions, including multiple performance obligations, variable consideration and contract modifications. The assessment and application of revenue recognition criteria to contractual arrangements require careful analysis and judgment, especially where the terms are ambiguous or subject to interpretation. The following challenges are also presented by variable consideration and uncertainty, resource constraints including skilled accounting personnel, IT support and training and finally communication of the impact on financial metrics and ratios to stakeholders.

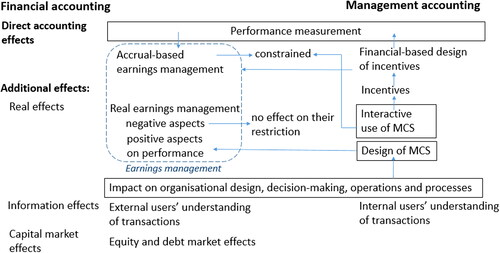

In relation to the effects of IFRS 15 mentioned in the previous research, this article deals with the impact of this new standard on the financial performance of University and Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trusts from both a financial and management accounting perspective. First, the article gives a summary of the anticipated effects and implications of a new revenue recognition standard, based on a literature review (). This brings us to the edge of financial and management accounting, where an interaction of both systems promotes the real effects of IFRS 15 adoption. The article also addresses specific aspects and issues from the healthcare industry, demonstrating that each could potentially generate real effects. Finally, the article presents an analysis, which tests the significance of financial performance yearly changes after IFRS 15 implementation in terms of accounting effects and confirms the influence of the new revenue recognition standard on the financial performance of Teaching and University Hospital NHS Foundation Trusts. This supports the existence of an accounting effect of IFRS 15 adoption among the UK public healthcare sector, thereby opening a discussion on the possibility of the occurrence of additional effects (information effects, capital market effects and real effects) to contribute to further research.

2. Literature review

The following section delves into the strategic practices of earnings management within the healthcare sector, with a particular focus on hospitals’ use of different tactics to navigate financial reporting standards. With the introduction of IFRS 15, mandatory for NHS bodies from April 2018, this research explores the nuanced implications of the standard for financial and management accounting. It highlights how regulatory changes are shaping earnings management strategies, the adaptation challenges unique to the healthcare industry, and the wider implications for financial reporting and accounting practices. It also looks at empirical studies examining the impact of IFRS 15 across different industries, highlighting its potential to refine revenue recognition and influence earnings management.

2.1. Earnings management strategies in healthcare

According to the previous research, there are three main earnings management strategies employed in hospitals. The first two are real activities manipulation (RAM), such as cutting expenditures and accrual-based earnings management (AEM) (Healy & Wahlen, Citation1999; Roychowdhury, Citation2006), and there is an evidence of a trade-off effect between these two strategies (Zang, Citation2012). Their usage was described in previous research (L. G. Eldenburg et al., Citation2011; Hoerger, Citation1991; Leone & van Horn, Citation2005; Vansant, Citation2016). For instance, while tighter accounting standards may be successful in constraining AEM, they do little to restrict REM, thereby promote a substitution effect (Ewert & Wagenhofer, Citation2005). Most of the studies in this field conclude that managers substitute AEM with REM in the post-SOX regime to inflate earnings, thus supporting the opportunistic theory of REM (Habib et al., Citation2022). Incentives for REM among non-profit hospitals are on the one hand losses avoidance, as reported losses will affect their reputations adversely, and on the other hand high earnings reduction, to avoid any regulatory scrutiny or third-party demand for reduced service charges (L. G. Eldenburg et al., Citation2011).

The third one consists in overbilling via misclassifying patients’ ailments, which unlike the first two strategies increases operating cash flows. It was found that hospitals are overbilling instead of RAM, when RAM is constrained due to hospitals’ weaker competitive status or financial distress, or AEM, when AEM is constrained by prior accounting choices. However, overbilling is likely to be constrained by hospitals’ operations (Heese, Citation2018). Hospitals’ motives for overbilling are poor financial condition and/or higher marginal costs (Soderstrom, Citation1993), the provision of charity care and medical education among non-profit hospitals (Heese et al., Citation2016) and the for-profit orientation of hospital (Silverman & Skinner, Citation2004). Additionally, it was found that for-profit hospitals’ motives to manage earnings are similar to those observed in other for-profit industries (L. Eldenburg et al., Citation2004), such as bonus payments (Roomkin & Weisbrod, Citation1999), career concerns (Dafny & Dranove, Citation2009) and pressure from stakeholders (L. Eldenburg et al., Citation2004).

2.2. Potential impact of IFRS 15 implementation and interdependence of financial and management accounting

As IFRS 15 ‘Revenue from Contracts with Customers’ is a mandatory requirement for NHS bodies and becomes effective for the annual period beginning on 1 April 2018, University and Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trusts started to recognise revenue in accordance with the core principles of IFRS 15 by applying the following five-step approach:

Identify the contract(s) with the customer.

Identify the performance obligations in the contract.

Determine the transaction price.

Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract.

Recognise revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation.

IFRS 15 has a particular impact on customer contracts, financial reports (Statement of Comprehensive Income), internal control, systems and processes. Additionally, the new standard requires an entity to create new quantitative and qualitative disclosure notes. Notwithstanding the many instances when IFRS 15 results in the same accounting as under IAS 18, the framework introduces completely new measurement differences when compared to IAS 18 in certain cases (DHSC, Citation2019b).

Although the implementation of IFRS 15 ‘Revenue from Contracts with Customers’ is primarily perceived as making a huge impact on financial reporting, as with any other standard or regulatory changes it also provides a fertile ground for management accounting research, according to Wagenhofer (Citation2016) due to at best three reasons:

The aim of regulatory change is to affect firms and managers to encourage desirable behaviours, or to discourage behaviours considered undesirable. A straightforward research question is whether the regulation is successful in achieving its objective, as well as in making an assessment of its indirect costs and benefits.

An interconnected research question is how regulation modifies the organisational design of firms, i.e. how firms optimally react and transform their internal organisation, decision-making and operations.

Occasionally, new regulations or standards oblige firms to disclose more information on corporate governance and on their business operations. The availability of such data provides researchers with new opportunities for empirical tests.

Owing to the interdependence of financial and management accounting, challenging questions arise with new or amended IFRS enactment. For instance, IFRS 15 on revenue recognition requires the allocation of the transaction price of a multicomponent contract to separable performance obligations based on their fair values. As a result, revenue and profit are often deferred to later periods, henceforth interfering with performance measurement and the provision of incentives at the time of closing a deal (Wagenhofer, Citation2016). Additionally, it was found that financial-based design of incentives is positively associated with earnings management actions and therefore the design of MSC plays a great role there (Abernethy et al., Citation2017). In line with a recent study on unintended effects, preparers find that changes introduced by IFRS 15 have impact on MCS and IT, and users consider that the implementation of IFRS 15 has led to changes in the use and design of MCS, changing some internal decision making and having positive consequences for efficiency (Osma et al., Citation2023). According to the latest findings in this field, MSC is also positively associated with REM. REM is also positively related to performance in combination with the interactive use of MSC (Osma et al., Citation2022), when the interactive use of MSC tears down heretical and functional obstacles (Abernethy & Brownell, Citation1999; Henri, Citation2006) and enables continual challenge and debate, encouraging and facilitating dialogue and contribution, sharing promoting ongoing discussions and innovation in finding action plans (Janke et al., Citation2014). However, AEM is constrained by the interactive use of MSC, which brings us back to their substitutive nature (Osma et al., Citation2022).

A summary of expected effects and impact of the new revenue recognition standard on financial and management accounting perspective is presented in . According to this summary, it is obvious that AEM should be constrained within direct accounting effects under IFRS 15. Concurrently the same effect should be achieved within an interactive use of MSC. On the other hand, a relating system for incentives using financial-based incentives could reverse support AEM. The other part of the effects is demonstrated within real effects, which interfere both with financial and management accounting. They affect the design of MSC and its interactive use enhances the positive influence of REM. However, unlike AEM, IFRS 15 has no restrictive effect on negative REM. Nevertheless, due to the substitutive nature of AEM and REM, we should expect REM to prevail after IFRS 15 adoption. Direct accounting effects could appear due to the AEM restriction. There are also expected to be other additional effects of IFRS 15 adoption, which are intended for further research. The following information effects could affect how external and internal users understand transactions. If these effects are significant, they are communicated to stakeholders. This leads to capital market effects, where equity market effects, debt market effects and subsequent pressure to maintain or improve performance could occur (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020).

While it might seem out of the ordinary that regulation should have a significant influence on management accounting as companies determine their organisational and management decision processes internally. Nevertheless, there are many regulatory influences constraining organisational design, incentives and management accounting procedures (van der Stede, Citation2011). Financial information used in management accounting is usually derived from financial accounts where it is sometimes accommodated for specific intentions and analyses. For instance, constructing an economic-value-added measure commonly includes an analysis of the incentive influence a measure has on operations and investment decisions, and making adjustments where necessary, such as for research and development or non-recurring items (Wagenhofer, Citation2016).

The first key empirical study on the relationship between regulated external financial reporting and management information was presented by Joseph et al. (Citation1996). The study was based on a survey of 308 qualified U.K. management accountants, which indicated a general trend towards integration not only between external financial reporting and internal accounting reports, but also with respect to the underlying data capture systems. On the other hand, the study detected ‘little evidence of a generally held belief that external reporting dominates internal accounting’ (Joseph et al., Citation1996, p. 90).

Nevertheless, the financial system in German-speaking countries since the 1990s has been transforming itself towards investors as the crucial stakeholder group (Benston et al., Citation2006; Krahnen & Schmidt, Citation2004), as signified by the growing use of IFRS, and supported by empirical evidence that MCS in these countries are also becoming more financially orientated (Colwyn Jones & Luther, Citation2005). Additionally, it has also been shown that companies whose financial accounting is targeted at investor decision making, especially those following IFRS or US GAAP standards, were motivated to integrate financial and management accounting (Hemmer & Labro, Citation2008). Generally, the harmonisation of international financial reporting standards has a major influence on the convergence of management accounting and financial accounting in areas, such as goodwill impairment, segment reporting and adoption of financial accounting principles in management accounting (Taipaleenmäki & Ikäheimo, Citation2013). The literature provides us with ample evidence that international accounting standards and principles, in particular, are suitable for internal control purposes (Ewert & Wagenhofer, Citation2006), in addition to depicting the increasing use of IFRS in the foremost German companies as a ‘choice opportunity’ (Joseph et al., Citation1996, p. 182) to align both financial and managerial accounting. IFRS-based financial accounting systems also have a twofold impact on controllership, firstly, by driving the use of integrated financial accounting systems, instead of the traditional dual accounting model for decision-making and control purposes and secondly, by extending the controllers’ roles towards becoming an information provider to the financial accounts (Angelkort et al., Citation2008).

Given this interdependence, the IAS Regulation that requires listed companies to adopt IFRS in consolidated financial statements has influenced management reporting systems. There is also the possibility that some performance measures that had been formerly used for management reporting are replaced by others supplied after the adoption of IFRS (DHSC, Citation2019b). As a consequence of adopting IFRS, a research opportunity arose as some internally used information had to be disclosed. One can now question whether the disclosure requirement itself has an impact on the selection of the data that are reported internally (Weißenberger & Angelkort, Citation2011).

2.3. Empirical studies on impact of IFRS 15 implementation

According to Trabelsi (Citation2018), results of the early application of the IFRS 15 analysis indicate that early adoption of IFRS 15 by Real Estate companies listed in the Dubai Financial Market has a significant positive affect on earnings and stockholder equity for all firms analysed in the article. The study shows that the new standard has a doubly favourable effect: revenue can be recognised over time and not at a point of time when almost all contracts with customers and contract costs are more likely capitalised rather than expensed. It is also expected that the new revenue accounting standard would, at the same time, give clearer guidance on revenue recognition for all entities with contracts with customers and reduce the potential for earnings management (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020). Concurrently Tutuno et al., based on a statistical analysis of a sample of Italian-listed companies, stated that the introduction of IFRS 15 should benefit the industries where earnings management is more frequent, such as the telecommunications industry (Tutino et al., Citation2019). Van Wyk and Coetsee (Citation2020) found that IFRS 15 provides an appropriate, control-based framework to account for construction contracts at a point in time when control is transferred to the end of the project, or over time when control is deemed to be transferred over time. One of the latest articles on revenue recognition practices in South Africa (Coetsee et al., Citation2022) found that it contributes to improving the overall decision usefulness of financial reporting as well. However, C. J. Nappier and C. Stadler (2020) introduced a cross-industry article assessing the multiple effects of IFRS 15 implementation, where they found that for recognition and measurement changes within direct accounting effects, the overall impact of IFRS 15 on profit was insignificant. According to findings of Ma et al. revealed that ‘for many firms (43) there was not a material impact of transition to IFRS 15, very few (5) experienced increase in retained earnings and the remainder 18 reported a reduction in retain earnings’ among Australian listed firms (Ma et al., Citation2021, p. 3). The following study on the impact of IFRS 15 adoption in Australia and New Zealand stated that there was no material impact, but that the impact varied by sector and suggested focusing on specific sectors for further research (Kabir & Su, Citation2022).

In conclusion, this literature review has analysed earnings management in the healthcare sector, focusing on hospital strategies and the impact of IFRS 15 on accounting practices. It has highlighted the challenges of adaptation and the potential for regulatory change to shape financial reporting. Empirical evidence underscores the role of IFRS 15 in refining revenue recognition and its broader implications across industries, providing critical insights for future research and practice within financial and management accounting.

3. Hypothesis development

The impact of IFRS 15 on financial statements could be observed, according to the academic study for EFRAG, from two perspectives – users (auditors, consultants, academics and professional investors) and preparers (controllers, chief accountants, heads of accounting policies departments, CFOs, CEOs and other preparers including internal auditors and managers of the IT system). While according to the users’ questionnaire results, in addition to a significant impact on disclosures, the impact of IFRS 15 on financial statements is assessed as moderate, particularly with regard to changes in the measurement and recognition of figures considering revenue, according to the preparers’ questionnaire result, this impact of IFRS 15 is assessed as low-moderate, except for a significant impact on disclosures (Osma et al., Citation2023). On the one hand, large-sample empirical studies (Kabir & Su, Citation2022; Ma et al., Citation2021; Napier & Stadler, Citation2020) found no material impact, but admitted that that this impact could vary by industry. On the other hand, according to the findings of the literature review, from earnings management perspective, we should expect an impact on financial performance after IFRS 15 adoption due to the AEM restriction and the relating RAM. Moreover, NHS Foundation Trusts have been proven to engage in earnings management manipulation in the past (Anagnostopoulou & Stavropoulou, Citation2021; Ballantine et al., Citation2007). Generally, there are many common forms of manipulation, as pointed out by Caylor (Citation2010): accounts receivables and deferred revenue to avoid negative earnings surprises and losses in earnings, contractual agreements with customers using manipulation or changes in accounting estimates in order to accelerate the recognition of receivables. As for hospitals cases, it is also needed to take into account that there could be also the third earnings management strategy employed – overbilling and we cannot exclude it. For this reason, it was decided to examine the impact of IFRS 15 within the healthcare industry in terms of the direct accounting effects in accordance with hypothesis:

H1. IFRS 15 ‘Revenue from Contracts with Customers’ implementation has a significant impact on the financial performance of Teaching and University Hospital Foundation Trusts.

Nevertheless, the ongoing results of this hypothesis are just about to open a discussion on which of the effects of IFRS 15 adoption played a primary role there, whether direct accounting effects within constraining AEM or real effects within promoting positive aspects on performance of REM. These questions are intended for further research, though. Motivation for REM among non-profit hospitals could be two folded. On the one hand, there is losses avoidance, as reported losses will affect their reputations adversely, and on the other hand high earnings reduction, to avoid any regulatory scrutiny or third-party demand for reduced service charges (Eldenburg et al., Citation2011). The potential real effects (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020) and special ones for healthcare industry, delimited by the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS Improvement in their manual ‘IFRS 15 and NHS Standard Contract’ (DHSC, Citation2019b), are demonstrated within five steps-approach of IFRS 15 implementation:

3.1. Identify the contract(s) with the customer

One of the first potential real effects could be observed within the first step, when identification of the contract with customer is performed. Although business contracts are written primarily to achieve commercial goals, rather than to fit an accounting standard, businesses may seek to align the form of their legal agreements to the way they are identified for the purposes of IFRS 15 to some extent. This could be performed by rewriting standard terms and conditions of operation. This may be a common strategy within the private healthcare, however due to a special legislation this effect could be restricted in public hospitals.

3.2. Identify the performance obligations in the contract

The next potential real effect lies in reviewal of services provided to the customers, so that distinct performance obligations may be easier identified and taken into consideration, when contracts are negotiated and accounted for. As a salesman may have had the discretion to offer incentives, such as ‘free’ maintenance agreement, to encourage customers to buy goods and under a new standard the recognition of an incurred cost is insufficient. These practices may be also performed in private hospitals, but there could be little motivation to perform so within the public healthcare sector.

3.3. Determine the transaction price

Another real effect could be observed when customer’s payments are deferred, which may imply a significant financing component in the contract, requiring the deferred payments to be included at their discounted present value and the discount to be treated as a finance income rather than revenue. Companies that employed such a structure in the past may tend to replace such terms by another structure that avoids splitting the transaction price between revenue and financial income. NHS Foundation Trusts come also with other specific issues for healthcare sector, which could cause at least three other effects within the third step (DHSC, Citation2019b):

3.3.1. Variable consideration

Applying step 3 of the IFRS 15 5-step approach, the total transaction price in treating a patient is determined by calculating the amount of consideration to which a provider will be entitled, including variable amounts. In case of any uncertainty that the expected income is going to be generated from the provision of services to a patient, the provider determines the probable total transaction price at the point of the patient’s admission.

The likelihood and the effect of a range of services being provided are incorporated into the initial transaction price at the beginning. The likelihood of the expected tariffs is designated on a portfolio basis and incorporated into the initial price at the inception of a new contract. Nevertheless, providers may struggle to calculate variable consideration in many situations because, from an individual patient perspective, the range or level of required services and the associated revenue is not known at the patient admission date. In this instance, revenue is recognised after these services are provided.

3.3.2. Multiple tariff elements

There are two ways that tariffs can be structured:

One tariff comprised multiple services, for example surgery and subsequent follow up appointments.

One tariff including only individual services, for example one tariff for surgery and one for each follow-up appointments separately.

Accounting for tariffs currently following the first structure creates more differences under IFRS 15. A tariff including multiple elements can have an element of variability significant to the uncertainty over the volume of service provided under the single tariff. For instance, there is the possibility that some patients could have a significantly higher volume of follow-up appointments while the tariff remains the same. In this case, any individual follow-up appointment exceeding the original expectations covered by the initial tariff results in a greater amount of services being provided. This is treated as a retrospective contract modification. With an increase in the level of services the tariff needs to be treated as a prospective contract modification.

According to the second structure, outpatient follow-up appointments are recognised as separate events; therefore, providers receive income for these individually, for instance, on a monthly basis. This means that this accounting treatment causes no differences under IFRS15. This enables providers to bundle care together and agree on a package-type approach, whereby there is an annual local tariff set which is paid on a monthly basis to the provider according to the number of patients. This makes a ground for another real effect when the hospital is going to choose a structure, which suits its revenue recognition the best or appears easier and less costly to implement.

3.3.3. Portfolio approach and variable consideration

In contrast with the 5-step model required by IFRS 15 for single contracts (a contract-by-contract approach), a portfolio approach is employed when the provider’s expectations on the impact of a portfolio approach application to the group of patients requiring treatment would not lead to materially different results, as when applying IFRS 15 to individual contracts.

For instance, when mental healthcare is provided, and healthcare treatment prolongs to a full-life term, with a large number of patients accessing multiple care packages over time, it is possible to not currently generate income on an individual level of activity. This provides a pragmatic way to apply IFRS 15 in a business environment where a large number of similar contracts are generated for which individual application of the 5-step model would be rather impractical.

3.4. Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract

As in some cases the determination of stand/alone selling prices may be a complex process and business may decide to no longer to include obligations in contracts where they need to estimate stand/alone selling prices, or to change their operations in order that stand-alone selling prices can be observed rather than estimated. This may be probably applied also in the healthcare sector.

3.5. Recognise revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation

In the last step, business may decide to reduce any degree of uncertainty by amending contracts to include a definite point at which an obligation may be considered to be satisfied. This may be applied also within NHS Foundation Trusts dues another specific issue at the fifth step (DHSC, Citation2019b):

3.5.1. Contracts lasting more than one year and incomplete visits

In relation to long-term contracts (exceeding one year) where patients receive long-term care overreaching multiple reporting periods, IFRS 15 requires information concerning that part of the transaction price allocated to unsatisfied performance obligations at the end of the year and a certain point of the time of revenue recognition in relation to these obligations.

Another issue concerns partially completed hospital visits when performance obligations may not be completed. If a visit is incomplete, an estimate should be made at the beginning of the contract to determine the expected length of the visit based on portfolios of different types of patient’s created in accordance to certain characteristics. Revenue recognition should be done evenly as the services are delivered and deferred to the end of the year to the point where extra services are expected to be received under the original tariff. When tariffs are not received at the end of the reporting period, a contract asset or contract receivable is recognised.

On the contrary, when the tariff has been received upfront without the full service having been provided at the end of the year, it should equally result in the revenue recognition reflecting the fair value of the provided services, concurrent with the recognition of a contract liability on the Balance sheet for the services still to be provided.

4. Research design

According to the new revenue recognition standard the transition to IFRS 15 can be implemented via one of the two transition approaches available: fully retrospective or partially retrospective (cumulative catch-up). The approach chosen must be applied throughout the organisation in a consistent way to all applicable income streams. However, in compliance with paragraph 4.47 of the Group Accounting Manual (GAM) (DHSC, Citation2019a), the transition option has been omitted and NHS Foundation Trusts should adopt IFRS in the year of transition via the partial retrospective or cumulative catch-up method. Consistent with the partial retrospective method, NHS Foundation Trusts recognise the cumulative effect of the new standard application at the date of the initial application by opening income and expenditure reserve within taxpayers’ equity (or another component of equity, as appropriate). Therefore, there is no restatement of the comparative periods presented. For this reason, the following comparative analysis is based on yearly changes of chosen figures of the Statement of Comprehensive Income and the Statement of Financial Position. Nevertheless, this GAM modification does not distort data in comparison to general market practices, where according to C. J. Nappier and C. Stadler ‘only 25% companies chose retrospective application’ (Napier & Stadler, Citation2020, p. 491) and according to findings of Ma et al. ‘relatively few firms adopted the retrospective approach’ among Australian (Ma et al., Citation2021, p. 3) listed firms.

Data for this analysis were hand-collected during August 2019 since all NHS trusts had to publish their 2018/2019 Annual Report and Accounts on their website before 31 July 2019, which was the first annual report prepared under IFRS 15. The same way was collected data from 4 last annual reports prepared under the previous revenue standards to enable Friedman’s Test. The starting point was a list of 45 Teaching and University Hospital NHS Foundation Trusts. Some of them were excluded due to missing Annual Reports and Accounts for year 2018/2019, incomplete timelines and recent mergers of 12 NHS trusts, so the final tested sample consisted of 33 Teaching/University Hospital NHS Foundation Trusts out of 150 NHS Foundation Trusts in total in 2019 (144 in March 2023). From the chosen scope of five years for financial statements from 2014/15 to 2018/19, four relative yearly changes were obtained 4 and entered into the analysis.

The analysis of the impact of IFRS 15 application concerning H1. ‘IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers implementation has a significant impact on the financial performance of Teaching and University Hospital Foundation Trusts’ is based on total operating income relative yearly changes represented by growth coefficients obtained from Statements of Comprehensive Income.

Friedman’s test, also known as two-way analysis of variance by ranks, was used to find differences in treatments across multiple trials. H0 assumes that there is no difference between the variables. If the calculated probability Sig. is below the selected significance level, H0 is rejected and it can be concluded that at least two of the variables are significantly different from each other. This test was chosen after testing the whole data set with the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. The test is based on the assumption that H0 is based on a normally distributed population, i.e. if the p value is below the alpha level, then H0 is rejected, which is evidence that the data under test are not normally distributed. Conversely, if the p value is above the chosen alpha level, the null hypothesis that the data come from a normally distributed population cannot be rejected. Except for a few samples, the p value for the rest of the dataset was above an alpha level of 5%, rejecting H0 and considering the entire dataset as not normally distributed, with high heterogeneity and extreme values. Therefore, a nonparametric Friedman test was used instead of T-test statistics.

5. Limitations

Assuming that the financial performance of an individual economic subject is highly sensitive to macroeconomic performance, there is a significant risk that the materiality of the change in revenues after IFRS 15 implementation has been distorted by the economic situation. The chosen indicator of macroeconomic evaluation (GDP) is shown in .

Table 1. Gross domestic product: year-on-year growth: CVM SA%.

According the data represented in , GDP growth rate of the UK slowed down over the last five years but remained stable with no evidence of a financial crisis. Additionally, all rate changes were slightly equalised due to the fact that financial statement of NHS Foundation Trusts always occur over two calendar years as they begin on 1 April. This means that the economic situation in the UK over the analysed period was stable, therefore, there is no significant risk of affecting the materiality of the potential change in revenues in the financial statements over 2018/19. Another supporting fact is that Government Expenditure on Health Services, the main source of NHS funding, has been constantly growing over the last five years with no fluctuation ().

Table 2. Government expenditure on health services: 2014/2015–2018/2019: UK (£billion).

6. Results and discussion

An entire data set was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, where H0 is based on a normally distributed population. This means that, if the p value is below alpha level, the H0 is rejected thereby providing evidence that the tested data are not normally distributed. On the contrary, if the p value is above the chosen alpha level, the null hypothesis that the data came from a normally distributed population cannot be rejected. Apart from a few samples, the p value for the rest of the data set was above an alpha level of 5%, with H0 being rejected and the overall data set being considered to be not normally distributed, characteristic with a high heterogeneity level including extreme values. For this reason, a non-parametric Friedman test, instead of T-test statistics was used.

Friedman’s test, known also as a two-way analysis of variance by ranks was employed to find differences in treatments across multiple attempts. H0 assumes no difference between the variables. If the calculated probability Sig. is below the selected level of significance, H0 is rejected, and it can be concluded that at least two of the variables significantly differ from each other.

The results of the two-way analysis of total operating income growth coefficients among 33 subjects within five years referring to H1 are shown in . According to the 2-sided Test of Two-Way Analysis the Sig. value is 0.000, which is below the selected level of significance at 5%, thus H0 is rejected and it is assumed that at least two of the growth coefficients significantly differ from each other. According to the mean rank growth coefficient, 2018–2019/2017–2018 is significantly different from growth coefficient 2015–2016/2014–2015. For this reason, H1 was accepted, which means that the new recognition standard implemented to 2018/2019 financial statements had a significant impact on the financial performance of Teaching and University Hospital NHS Foundation Trusts represented by total operating income. This means that the existence of accounting effect of IFRS 15 adoption among UK public healthcare sector was proven.

Table 3. The impact of IFRS 15 implementation on yearly changes in growth coefficients of total operating income and operating income from patient care activities.

This can be explained by operating income from patient care activities growth coefficients – a main component of total operating income. According to the two-sided test of two-way analysis, the Sig. value is 0.003, which is below the selected level of significance at 5%, thus H0 is rejected and it is assumed that at least two of the growth coefficients significantly differ from each other. According to the Mean Rank growth coefficient, 2018–2019/2017–2018 is significantly different from the 2015–2016/2014–2015 growth coefficient, which corresponds with the results for total operating income.

The question arising is whether this impact leads to an increase or reduction in total operating income. Despite the 2018–2019/2017–2018 growth coefficient being, on average, 4 pp lower than the 2017–2018/2016–2017 growth coefficient, there are 22 absolute increases and 11 absolute reductions in growth coefficients in comparison to five absolute increases and 28 absolute reductions in coefficient rates of single coefficients for 2017–2018/2016–2017. For Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, the operating income from patient care activities increased by 10.46% from 2017–2018 to 2018–2019, compared to an increase of 2.47% from 2016–2017 to 2017–2018. Similarly, for North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust, the operating income increased by 9.51% from 2017–2018 to 2018–2019, compared to an increase of 1.17% from 2016–2017 to 2017–2018. Finally, for North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust, the operating income increased by 8.5% from 2017–2018 to 2018–2019, compared to an increase of 1.96% from 2016–2017 to 2017–2018. However, at Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, the operating income from patient care activities decreased by 0.23% from 2017–2018 to 2018–2019, compared to an increase of 6.42% from 2017–2018 to 2016–2017. Similarly, at Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, the operating income decreased by 2.04% from 2017–2018 to 2018–2019, compared to an increase of 3.1% from 2017–2018 to 2016–2017. It is obvious that following IFRS 15 adoption, the trend absolute differences in individual growth coefficients measured in percentage points has changed, which is the same for operating income from patient care activities. The results are in line with the academic study for EFRAG, where, according to the results of the users’ questionnaire, the impact of IFRS 15 on financial statements is assessed as moderate, in particular with regard to changes in the measurement and recognition of figures considering revenue, and according to the results of the preparers’ questionnaire, this impact of IFRS 15 is assessed as low-moderate (Osma et al., Citation2023).

However, the contradictory results could imply the coexistence of direct accounting effect and real effects. Simultaneously, existence of different real effects is also coherent with two different types of motivation for REM among non-profit hospitals and it could be interconnected with actual financial performance. The poor one could support losses avoidance, as reported losses will affect their reputations adversely. The outstandingly good one could stand behind high earnings reduction, to avoid any regulatory scrutiny or third-party demand for reduced service charges (Eldenburg et al., Citation2011). However, there are other real earnings opportunities arising from each step of IFRS 15 implementation, combined with the specific issues of NHS Foundation Trusts, described in the section Hypothesis development. For example, multiple tariff elements issuing a different amount of revenue in single periods is recognised according to the chosen tariff structure. This means that different tariff structures implemented by different NHS Foundation Trusts can have a varied impact on operating income from patient care activities. Nevertheless, the article has identified potential real effects of the IFRS 15 adoption in the healthcare sector, but their examination is intended for further research.

7. Conclusion

The objective of this article was, first, to summarise the expected effects and impacts of a new revenue recognition standard. Based on the literature review, as a direct accounting effect, it was expected AEM to be constrained under IFRS 15. Concurrently the same effect was expected to be achieved within an interactive use of MSC. There is a point, we occur on the edge of financial and management accounting, simultaneously an interaction of both systems promotes real effects of IFRS 15 adoption. Thereby his article also represents a contribution to prior research on the interdependence of financial and management accounting. Real effects such as the impact on organisational design, decisions, operations and processes affect a design of MSC and its interactive use enhances the positive influence of REM. However, IFRS 15 is expected to have no restrictive effect on the negative aspects of REM, unlike on AEM. Nevertheless, due to the substitutive nature of AEM and REM, the REM was expected to prevail after IFRS 15 implementation. Thus, direct accounting effects could appear due to AEM restriction.

Second, the article was dealing with the potential real effects of IFRS 15 adoption and special aspects and issues from the healthcare industry demonstrated within five-step approach. It was shown, that each step could potentially generate real effects. Finally, the article presented an analysis testing the significance of financial performance yearly changes after IFRS 15 implementation in terms of accounting effects to prove the impact of IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers adoption on performance measurement among Teaching and University NHS Foundation Trusts. As a part of UK public sector organisations, they switched to IFRS for their 2009/2010 financial statements ‘to bring benefits in consistency and comparability between financial reports in the global economy and to follow private sector best practice’ (HM Treasury, Citation2007, para. 6.59).

As a result, the hypothesis H1: ‘IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers implementation has a significant impact on the financial performance of Teaching and University Hospital Foundation Trusts’ was proven, thus the influence of the new revenue recognition standard on the financial performance of Teaching and University Hospital NHS Foundation Trusts was confirmed. This supports the existence of accounting effect of IFRS 15 adoption among UK public healthcare sector. This result is also in accordance with previous research run on real estate companies listed in the Dubai Financial Market, where a significant effect on earnings among early adopters of IFRS 15 was found (Trabelsi, Citation2018). Concurrently, as GDP growth rate was stable and the NHS foundation funding grew steadily over the analysed period of time, due to a strong and constant source – Government Expenditure on Health Services, the results of this analysis were not distorted by any economic cycle fluctuation.

However, this accounting effect does not necessarily or generally signify either an increase or decrease of total operating income and could indicate a varied impact on the revenue recognition process. The reason lies in coexistence of direct accounting effect and real effects that affect performance measurement, defined as unintended effect of IFRS 15 adoption. Simultaneously existence of different real effects is also coherent with two different types of motivation for REM among non-profit hospitals and it could be interconnected with actual financial performance. The poor one could support losses avoidance, as reported losses will affect their reputations adversely. The outstandingly good one could stand behind high earnings reduction, to avoid any regulatory scrutiny or third-party demand for reduced service charges (Eldenburg et al., Citation2011). This could be driven both by information and capital market effects. Other potential real effects could occur, when applying each out of the five steps of IFRS 15 implementation combined the specific issues of the NHS Foundation Trusts described in the section Hypothesis Development. For instance, the twofold impact could be caused by different tariff structures, where NHS Foundation Trusts can choose between one tariff comprising multiple services and one tariff including only individual services with a choice between a portfolio approach and variable consideration, as well as in the treatment of contracts exceeding one year and incomplete hospital visits. Nevertheless, the detailed examination of the additional effects is intended for further research.

Finally, it is important for policy makers and managers in the healthcare industry considering IFRS 15 to fully understand the impact of IFRS 15 on revenue recognition practices in the healthcare industry. This includes recognising the complexity of healthcare contracts, the potential impact on financial statements and the need for enhanced disclosures. In addition, managers should establish processes for monitoring and evaluating compliance with IFRS 15 on an ongoing basis. This includes reviewing financial statements, assessing the effectiveness of internal controls and addressing any issues or discrepancies identified during the implementation process. This process should be accompanied with clear communication, which is key to the successful implementation of IFRS 15 in healthcare organisations. Policy makers and managers should communicate the importance of compliance with the new standard, provide guidance and support to staff, and engage with stakeholders to address any concerns or questions related to changes in revenue recognition practices.

At the same time, managers should assess existing accounting systems, processes and controls to ensure that they are capable of supporting compliance with IFRS 15. This may involve updating systems to capture and track relevant data, implementing new accounting policies and procedures, and strengthening internal controls to mitigate risks associated with revenue recognition. Which brings us to the importance of considering that the new revenue recognition standard could have real effects, such as an impact on organisational design, decision making, operations and processes, that will affect the design of the MCS. In order to realise this potential, it is crucial to consider the interactive use of MCS to positively influence the performance of the organisation and constrain AEM.

Availability of data and material

Available from author on request.

Code availability

Non applicable.

Disclosure statement

None.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anita Tenzer

Anita Tenzer is affiliated with the Department of Management Accounting at Prague University of Economics and Business. Her research focuses on the impact of IFRS adoption on management accounting practices within healthcare.

References

- Abernethy, M. A., Bouwens, J., & Kroos, P. (2017). Organization identity and earnings manipulation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 58, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2017.04.002

- Abernethy, M. A., & Brownell, P. (1999). The role of budgets in organizations facing strategic change: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(3), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(98)00059-2

- Anagnostopoulou, S. C., & Stavropoulou, C. (2021). Earnings management in public healthcare organizations: the case of the English NHS hospitals. Public Money & Management, 43(2), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1866854

- Angelkort, H., Sandt, J., & Weißenberger, B. E. (2008). Controllership under IFRS: Some critical observations from a German-speaking country. Universitat Giessen.

- Ballantine, J., Forker, J., & Greenwood, M. (2007). EARNINGS MANAGEMENT IN ENGLISH NHS HOSPITAL TRUSTS. Financial Accountability & Management, 23(4), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2007.00436.x

- Benston, G. J., Bromwich, M., Litan, R. E., & Wagenhofer, A. (2006). Worldwide financial reporting. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195305833.001.0001

- Bereskin, F. L., Hsu, P. H., & Rotenberg, W. (2018). The real effects of real earnings management: Evidence from innovation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(1), 525–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12376

- Caylor, M. L. (2010). Strategic revenue recognition to achieve earnings benchmarks. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 29(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2009.10.008

- Coetsee, D., Mohammadali-Haji, A., & van Wyk, M. (2022). Revenue recognition practices in South Africa: An analysis of the decision usefulness of IFRS 15 disclosures. South African Journal of Accounting Research, 36(1), 22–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10291954.2020.1855886

- Colwyn Jones, T., & Luther, R. (2005). Anticipating the impact of IFRS on the management of German manufacturing companies: Some observations from a British perspective. Accounting in Europe, 2(1), 165–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180500379160

- Corvellec, H. (2018). Stories of achievements: Narrative features of organizational performance. Stories of achievements: Narrative features of organizational performance. Transaction Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351292009

- Dafny, L., & Dranove, D. (2009). Regulatory exploitation and management changes: Upcoding in the hospital industry. The Journal of Law and Economics, 52(2), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1086/589705

- DHSC. (2019a). Group accounting manual 2018–19. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/791486/dhsc-group-accounting-manual-2018-to-2019.pdf

- DHSC. (2019b). NHS improvement: “IFRS 15 and NHS standard contract” manual. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/DHSC_-_IFRS_15_and_NHS_Standard_Contract.pdf

- Eldenburg, L. G., Gunny, K. A., Hee, K. W., & Soderstrom, N. (2011). Earnings management using real activities: Evidence from nonprofit hospitals. The Accounting Review, 86(5), 1605–1630. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10095

- Eldenburg, L., Hermalin, B. E., Weisbach, M. S., & Wosinska, M. (2004). Governance, performance objectives and organizational form: Evidence from hospitals. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10(4), 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1199(03)00031-2

- Ewert, R., & Wagenhofer, A. (2005). Economic effects of tightening accounting standards to restrict earnings management. The Accounting Review, 80(4), 1101–1124. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2005.80.4.1101

- Ewert, R., & Wagenhofer, A. (2006). Management accounting theory and practice in German-speaking countries. Handbooks of Management Accounting Research, 2, 1035–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1751-3243(06)02021-9

- Grigoroudis, E., Orfanoudaki, E., & Zopounidis, C. (2012). Strategic performance measurement in a healthcare organisation: A multiple criteria approach based on balanced scorecard. Omega, 40(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2011.04.001

- Gunny, K. A. (2010). The relation between earnings management using real activities manipulation and future performance: Evidence from meeting earnings benchmarks*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 855–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2010.01029.x

- Habib, A., Ranasinghe, D., Wu, J. Y., Biswas, P. K., & Ahmad, F. (2022). Real earnings management: A review of the international literature. Accounting & Finance, 62(4), 4279–4344. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12968

- Harker, R. (2019). NHS funding and expenditure, briefing paper CBP0724. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN00724/SN00724.pdf

- Healy, P. M., & Wahlen, J. M. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.1999.13.4.365

- Heese, J. (2018). The role of overbilling in hospitals’ earnings management decisions. European Accounting Review, 27(5), 875–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2017.1383168

- Heese, J., Krishnan, R., & Moers, F. (2016). Selective regulator decoupling and organizations’ strategic responses. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 2178–2204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0446

- Hemmer, T., & Labro, E. (2008). On the optimal relation between the properties of managerial and financial reporting systems. Journal of Accounting Research, 46(5), 1209–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2008.00303.x

- Henri, J. F. (2006). Management control systems and strategy: A resource-based perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(6), 529–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2005.07.001

- HM Treasury. (2007). HM treasury budget 2007, economic and fiscal strategy report, financial statement and budget report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/231363/0342.pdf

- Hoerger, T. J. (1991). “Profit” variability in for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals. Journal of Health Economics, 10(3), 259–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6296(91)90030-Q

- Hult, G. T. M., Ketchen, D. J., Griffith, D. A., Chabowski, B. R., Hamman, M. K., Dykes, B. J., Pollitte, W. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2008). An assessment of the measurement of performance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6), 1064–1080. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:pal:jintbs:v:39:y:2008:i:6:p:1064-1080 https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400398

- Janke, R., Mahlendorf, M. D., & Weber, J. (2014). An exploratory study of the reciprocal relationship between interactive use of management control systems and perception of negative external crisis effects. Management Accounting Research, 25(4), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2014.01.001

- Joseph, N., Turley, S., Burns, J., Lewis, L., Scapens, R., & Southworth, A. (1996). External financial reporting and management information: A survey of U.K. management accountants. Management Accounting Research, 7(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1006/mare.1996.0004

- Kabir, H., & Su, L. (2022). How did IFRS 15 affect the revenue recognition practices and financial statements of firms? Evidence from Australia and New Zealand. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 49, 100507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2022.100507

- Krahnen, J., & Schmidt, R. (2004). Corporate Governance in Germany: An Economic Perspective. In J. Krahnen & R. Schmidt (Eds.), The German financial system (pp. 450-482). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199253161.001.0001

- Leone, A. J., & van Horn, R. L. (2005). How do nonprofit hospitals manage earnings? Journal of Health Economics, 24(4), 815–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.01.006

- Leuz, C., & Wysocki, P. D. (2016). The economics of disclosure and financial reporting regulation: Evidence and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(2), 525–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12115

- Ma, L., Onie, S., Spiropoulos, H., & Wells, P. A. (2021). An evaluation of the impacts of the adoption of IFRS 15 revenue from contracts with customers. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1-40. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3963462

- Malikov, K., Coakley, J., & Manson, S. (2019). The effect of the interest coverage covenants on classification shifting of revenues. The European Journal of Finance, 25(16), 1572–1590. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2019.1618888

- Meier, K. J., & O’Toole, L. J. (2013). Subjective organizational performance and measurement error: Common source bias and spurious relationships. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(2), 429–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus057

- Micheli, P., & Mari, L. (2014). The theory and practice of performance measurement. Management Accounting Research, 25(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2013.07.005

- Napier, C. J., & Stadler, C. (2020). The real effects of a new accounting standard: the case of IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers. Accounting and Business Research, 50(5), 474–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2020.1770933

- Osma, B. G., Gomez-Conde, J., & Lopez-Valeiras, E. (2022). Management control systems and real earnings management: Effects on firm performance. Management Accounting Research, 55, 100781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2021.100781

- Osma, B. G., Gomez-Conde, J., & Mora, A. (2023). Intended and unintended consequences of IFRS 15 adoption. https://www.efrag.org/Assets/Download?assetUrl=/sites/webpublishing/SiteAssets/Academic%2520study%2520-%2520Intended%2520and%2520Unintended%2520Consequences%2520of%2520IFRS%252015%2520Adoption.pdf

- Roomkin, M. J., & Weisbrod, B. A. (1999). Managerial compensation and incentives in for-profit and nonprofit hospitals. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 15(3), 750–781. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/15.3.750

- Roychowdhury, S. (2006). Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 335–370. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:jaecon:v:42:y:2006:i:3:p:335-370 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.01.002

- Shea, T., Cooper, B. K., de Cieri, H., & Sheehan, C. (2012). Evaluation of a perceived organisational performance scale using Rasch model analysis. Australian Journal of Management, 37(3), 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896212443921

- Silverman, E., & Skinner, J. (2004). Medicare upcoding and hospital ownership. Journal of Health Economics, 23(2), 369–389. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:jhecon:v:23:y:2004:i:2:p:369-389 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.09.007

- Singh, S., Darwish, T. K., & Potočnik, K. (2016). Measuring organizational performance: A case for subjective measures. British Journal of Management, 27(1), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12126

- Soderstrom, N. S. (1993). Hospital behavior under medicare incentives. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 12(2), 155–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4254(93)90010-9

- Taipaleenmäki, J., & Ikäheimo, S. (2013). On the convergence of management accounting and financial accounting – the role of information technology in accounting change. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 14(4), 321–348. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:ijoais:v:14:y:2013:i:4:p:321-348 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2013.09.003

- Trabelsi, N. S. (2018). IFRS 15 early adoption and Accounting Information: Case of real estate companies in Dubai. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 22(1), 1-12. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/ifrs-15-early-adoption-and-accounting-information-case-of-real-estate-companies-in-dubai-6983.html

- Trading Economics. (n.d). United kingdom GDP annual growth rate. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/gdp-growth-annual

- Tutino, M., Regoliosi, C., Mattei, G., Paoloni, N., & Pompili, M. (2019). Does the IFRS 15 impact earnings management? Initial evidence from Italian listed companies. African Journal of Business Management, 13(7), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2018.8735

- van der Stede, W. A. (2011). Management accounting research in the wake of the crisis: Some reflections. European Accounting Review, 20(4), 605–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2011.627678

- Van Wyk, M., & Coetsee, D. (2020). The adequacy of IFRS 15 for revenue recognition in the construction industry. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/jef.v13i1.474

- Vansant, B. (2016). Institutional pressures to provide social benefits and the earnings management behavior of nonprofits: Evidence from the US hospital industry. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(4), 1576–1600. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12215

- Wagenhofer, A. (2016). Exploiting regulatory changes for research in management accounting. Management Accounting Research, 31, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.08.002

- Weißenberger, B. E., & Angelkort, H. (2011). Integration of financial and management accounting systems: The mediating influence of a consistent financial language on controllership effectiveness. Management Accounting Research, 22(3), 160–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2011.03.003

- Yassin, M. M., Shaban, O. S., Al-Sraheen, D. A. D., & Al Daoud, K. A. (2022). Revenue standard and earnings management during the covid-19 pandemic: a comparison between ifrs and gaap. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 11(2), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.22495/jgrv11i2art7

- Zang, A. Y. (2012). Evidence on the trade-off between real activities manipulation and accrual-based earnings management. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 675–703. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10196