?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This research aims to explore the nexus between business strategy and dividend payments. Utilizing a dataset encompassing U.S.-listed firms spanning the period from 1995 to 2018, our analysis reveals that firms employing prospector strategies exhibit a higher propensity for dividend payments compared to defender firms. Our findings persist even when accounting for firm fixed effects, employing an alternative subsample methodology, and demonstrating resilience to endogeneity and Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analysis. We also document that agency conflict issues related to free cash flow in prospector firms, stemming from overinvestment and capital expenditure reduction, contribute to an escalation in dividend payouts relative to defender firms. Finally, the prospector-dividend payment association is more pronounced in the context of weaker firm-level information and governance environments and during periods characterized by high policy uncertainty. Overall, our study fills a crucial gap in the literature on the complexities of dividend decisions within the context of different strategic orientations.

1. Introduction

In the corporate finance literature, the importance of corporate dividend policy for shareholders, managers, and the stock market has been highlighted by seminal works such as those by Walter (Citation1956), Black and Scholes (Citation1974), Allen and Michaely (Citation1995), Grullon et al. (Citation2002), DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006), and Akindayomi and Amin (Citation2022). Despite the extensive empirical research on the dividend puzzle, a conspicuous gap in the literature emerges concerning the influence of firms’ business strategies on corporate dividend policy. This study aims to address this gap and shed light on the factors shaping corporate dividend payouts, exploring the potential mechanisms driving this association.

A composite measure of business strategy was crafted by Ittner et al. (Citation1997) and Miles and Snow (Citation1978, Citation2003), leading to the categorization of firms into three distinct groups: prospectors, defenders, and analyzers. Prospector firms are characterized by their innovation-oriented approach, actively participating in research and development (R&D) activities, and dynamically adapting their product-market mix. In contrast, defender strategy-following firms prioritize efficiency, maintaining lower R&D intensity, concentrating on a stable product base, and showcasing consistent growth patterns within existing product lines. Analyzers, positioned between these two extremes, embody a balanced approach, as outlined by Miles and Snow (Citation1978, Citation2003) and Hambrick (Citation1983). Existing studies suggest that organizations characterized by a prospector strategy may face an elevated risk of information asymmetry due to the absence of R&D pricing information and a high level of outcome uncertainty associated with risky and innovative projects (Aboody & Lev, Citation2000; Rajagopalan, Citation1997). Additionally, prospectors, with their broad range of products and markets, exhibit more growth opportunities, exacerbating information asymmetry problems between managers and external stakeholders interested in these firms (Miles & Snow, Citation1978, Citation2003). Prior research also links prospectors to higher agency conflicts compared to defenders (Chen & Keung, Citation2019; Dang et al., Citation2022; Ittner et al., Citation1997; Rajagopalan, Citation1997; Rajagopalan & Finkelstein, Citation1992). The argument posits that the intensive requirements of R&D investment (Hambrick, Citation1983; Sabherwal & Chan, Citation2001; Snow & Hambrick, Citation1980) and the absence of well-defined performance assessment (Miles & Snow, Citation2003; Naiker et al., Citation2008) in prospector firms create incentives for managers to over-invest in inefficient projects. Literature also indicates that managerial risk-taking behavior and reporting opacity in prospectors exacerbate agency problems between managers and external stakeholders in these firms (Armstrong et al., Citation2013; Brockman et al., Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2015). Further research highlights that prospector firms have heightened incentives to mitigate information asymmetry and agency costs with capital providers, given their reliance on external financing sources (Bentley et al., Citation2013; Miles & Snow, Citation1978, Citation2003). According to dividend signaling theory, a high dividend payout ratio could serve as an effective strategy for these firms to send costly positive signals about future prospects, the trustworthiness of management, and the low level of agency conflicts (Lloyd et al., Citation1985). Hail et al. (Citation2014) find that investors demand fewer dividend payments when information asymmetry is low, as they are more confident about the security of the wealth they have invested in the firm.

Despite the extensive body of research on this subject, a conspicuous gap exists, particularly in the exploration of how firms’ business strategies influence their dividend decisions. Prior studies have predominantly focused on financial metrics, ownership structure, and macroeconomic factors as determinants of dividend policy, often neglecting the crucial role played by a firm’s chosen business strategy. This oversight represents a significant theoretical gap as business strategy, encompassing choices regarding innovation, efficiency, and market positioning, fundamentally shapes a firm’s operations and long-term objectives. The absence of empirical evidence addressing this gap implies an incomplete understanding of the intricate interplay between strategic choices and dividend outcomes. Also, prior research lacks a comprehensive examination of the underlying mechanisms driving the relationship between business strategy and dividend payouts. Our study seeks to address these theoretical limitations by integrating business strategy into the dividend policy framework, offering a better understanding of how strategic choices impact the distribution of profits to shareholders.

Employing the framework of Ittner et al. (Citation1997) and Miles and Snow (Citation1978, Citation2003), we test the relationship between prospector business strategy and dividend payouts using a large sample of U.S. firms over the period from 1995 to 2018. We find consistent evidence that the dividend payout is larger in firms with a prospector-type business strategy than in those with a defender-type business strategy. This finding holds in all specifications using alternative proxies for dividend payment, and when we conduct a series of tests controlling for firm and year fixed effects and even employing different subsamples with separate prospectors and defenders. Further, our results remain robust to various tests using two-stage least squares (2SLS) regressions and propensity score matching (PSM) analysis to address potential endogeneity concerns that may arise due to reverse causality problems and omitted variables. Collectively, our findings suggest that investors require lower dividends in firms adopting a defender-type strategy. Additionally, we find that this positive association between a prospector business strategy and corporate dividend policy is more pronounced in the context of weaker firm-level information and governance environments and during periods characterized by high policy uncertainty, as gauged by economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and presidential elections.

This paper makes four primary contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, our study enhances the limited literature by focusing on the factors influencing dividend payouts. By incorporating business strategy, we are the first to empirically support the notion that business strategy could serve as a determinant of dividend policy. Specifically, firms adopting an innovation-oriented prospector strategy are inclined to pay higher dividends than those adhering to an efficiency-oriented defender strategy. This understanding of the impact of business strategy on dividend payments can aid shareholders in effectively allocating their resources among firms with diverse business strategies. In essence, our study makes a substantial contribution to the corporate finance literature. Secondly, previous research has outlined the repercussions of business strategy on various corporate finance decisions, such as investment (Habib & Hasan, Citation2021; Navissi et al., Citation2017), budgetary usage (Collins et al., Citation1997), cash holdings (Magerakis & Tzelepis, Citation2020), and tax aggressiveness (Higgins et al., Citation2015). We extend this line of research by providing evidence that business strategy has a more extensive application in the field of corporate finance than previously acknowledged in the literature. Thirdly, our paper also investigates the underlying channels driving the positive relationship between prospectors and dividend payouts. This extension is crucial for constructing more robust explanations regarding the transmission mechanisms through which firms’ business strategy influences their dividend decisions. Our findings indicate that agency conflict issues related to free cash flow in prospectors, stemming from over-investment and capital expenditure reduction, contribute to an increase in dividend payouts in these firms compared to those adopting a defender business strategy. Lastly, we contribute further evidence for the association between firms’ business strategy and dividend decisions by examining this core relationship within different information and governance environments, particularly during periods of high economic and political uncertainty. We discover that this positive relationship is more pronounced in weaker information and governance environments and is more affected during periods of high economic policy uncertainty and U.S. presidential elections. To the best of our knowledge, this research focus has not been extensively detailed in the previous literature.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related literature and develops the hypothesis. Section 3 elucidates the research methodology and data. Empirical results are presented in Section 4, and conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2. Background

Empirical finance research indicates that a range of financial characteristics play a significant role in influencing corporate dividend payouts. Important factors include firm size, as highlighted by Farinha (Citation2003), financial leverage, as explored by Cooper and Lambertides (Citation2018), and the impact of free cash flow, a concept originally introduced by Jensen (Citation1986). Other determinants, including growth opportunities (La Porta et al., Citation2000), idiosyncratic risk (Ben-David, Citation2010), ownership structure (Bataineh, Citation2021; Firth et al., Citation2016; Grinstein & Michaely, Citation2005), corporate governance (Atanassov & Mandell, Citation2018), corporate risk management (Dionne & Ouederni, Citation2011), board gender (Chen et al., Citation2017), and the life cycle of firms (Bhattacharya et al., Citation2020), collectively contribute to shaping the dynamics of corporate dividend payouts. Taxation is also identified as a significant factor in firms’ payout policies (Brav et al., Citation2008; Brown et al., Citation2007; Chetty & Saez, Citation2005; Floyd et al., Citation2015; Poterba, Citation2004; Poterba & Summers, Citation1984). Legal environment factors, such as insider trading laws, trading restrictions, or general investor protection, also play a role in corporate dividend payments (Alzahrani & Lasfer, Citation2012; Brockman et al., Citation2014; Efthymiou et al., Citation2021; Fang et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, another strand of research explores the influence of the information environment, as demonstrated by Miller and Rock (Citation1985) and Li and Zhao (Citation2008), along with the impact of price informativeness, as highlighted by De Cesari and Huang-Meier (Citation2015), on corporate dividend decisions. Existing literature also highlights the significant role of uncertainty, with particular attention to economic policy uncertainty, as explored by Abreu and Gulamhussen (Citation2013), Bliss et al. (Citation2015), and Attig et al. (Citation2021), in shaping the dynamics of dividend payments. Despite the extensive discourse on the determinants of dividend policy in corporate finance literature, a gap exists in understanding the impact of business strategy on corporate dividend policy. This paper addresses this issue by incorporating business strategy into the analysis.

The management literature categorizes businesses into three strategies: prospectors, analyzers, and defenders, based on competitive advantages like products, markets, technology design, and organizational structures (Miles & Snow, Citation1978, Citation2003). Previous studies have linked R&D-intensive firms, such as prospectors, with heightened information asymmetry compared to defenders. Several factors contribute to this phenomenon. Firstly, as R&D investments are unique to each firm, outside investors lack pricing information by observing other firms’ R&D activities (Aboody & Lev, Citation2000). Additionally, the absence of organized markets for intangible assets deprives investors of asset pricing information (Aboody & Lev, Citation2000; Barth et al., Citation2001). Moreover, as prospectors pursue risky and innovative projects, they inherently exhibit greater outcome uncertainty than defenders (Bentley et al., Citation2013; Rajagopalan, Citation1997), resulting in a higher level of information asymmetry. Smith and Watts (Citation1992) also demonstrate that prospectors, focused on seeking new and innovative products, identifying and exploiting new market opportunities, tend to possess more growth options. Consequently, they exhibit greater information asymmetry between managers and outside investors concerning the expected future cash flows from investment opportunities. In a similar vein, the less formalized and decentralized organizational structure of prospectors affords significant decision-making discretion to their managers (Ittner et al., Citation1997; Miles & Snow, Citation1978). This discretion enables managers to act in their self-interest, potentially at the expense of outside investors. Bizjak et al. (Citation1993) reveal that prospector managers are motivated to over-invest in order to maximize stock price performance, even when cognizant that such sub-optimal investment decisions may lead to future under-performance. Moreover, when prospector managers have a higher level of stock-based compensation, the propensity for over-investment is further exacerbated to maximize personal benefits. Empirical studies indicate that prospector firms are at a higher risk of experiencing crash events (Habib & Hasan, Citation2017) compared to defenders. Research by Armstrong et al. (Citation2013), Brockman et al. (Citation2015), and Chen et al. (Citation2015) suggests that such managerial risk-taking behavior heightens agency conflicts between managers and external stakeholders. Furthermore, prospectors are associated with greater financial reporting irregularities (e.g., restatements and shareholders’ lawsuits), higher audit fees (Bentley-Goode et al., Citation2017), and weaker internal control over financial reporting (Bentley-Goode et al., Citation2017). These factors further contribute to heightened agency conflicts between managers and outside investors in prospector firms. On the other hand, utilizing a dataset comprising publicly traded companies in Indonesia spanning the period from 2012 to 2018, Herusetya et al. (Citation2023) applied Miles and Snow (Citation1978, Citation2003) framework. Their investigation revealed that firms adopting prospector-type business strategies exhibited lower levels of accrual earnings management and real activities manipulation compared to those employing defender-type business strategies. This means that business strategies categorized as prospector types, which emphasize innovation and long-term performance goals, may not inherently encourage management to partake in earnings management.

Overall, the exploration of the impact of business strategy on corporate dividend policy constitutes an essential and timely context for this study. Given the evolving landscape of corporate governance and strategic decision-making, understanding how distinct business strategies shape dividend policies becomes crucial. The prospectors, driven by innovation and risk-taking, present an intriguing dynamic with heightened information asymmetry, managerial discretion, and a propensity for over-investment. As businesses navigate a complex relationship of market dynamics, regulatory frameworks, and strategic orientations, investigating how these strategies influence dividend policies provides a better understanding of corporate behavior. The uniqueness of this context lies in the examination of not only the financial determinants but also the strategic choices that impact shareholder value. As a result, examining the influence of business strategy on dividend policies contributes to a broader comprehension of corporate financial strategies, making it a relevant and insightful area of study.

3. Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework designed for this study is intensely rooted in two major theoretical perspectives: agency theory and signaling theory. Agency theory explores the relationship dynamics between managers and shareholders within organizations. Jensen and Meckling’s seminal work in 1976 established the theoretical foundations by recognizing the fundamental misalignment of interests between these two key stakeholders. Managers, acting as agents, are tasked with making decisions on behalf of shareholders, who are the principals. The central idea of agency theory is that conflicts arise due to the differing priorities and incentives of managers and shareholders. In the context of business strategy heterogeneity, this theory becomes a powerful tool to analyze how various strategic orientations introduce distinct agency conflicts, shaping the decision-making processes related to dividend distributions. Particularly, a prospector firm, driven by a risk-taking and innovative orientation, may encounter heightened agency conflicts compared to defender or analyzer firms. The pursuit of new opportunities, potentially involving high levels of uncertainty and risk, could create tensions between managers eager to undertake ambitious projects and shareholders seeking consistent returns. Agency theory, in this context, allows for a better understanding of how strategic choices impact the nature and intensity of agency conflicts. The literature on agency theory, spanning classic works like Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) to more recent contributions (Bentley et al., Citation2013; Bentley-Goode et al., Citation2017; Habib & Hasan, Citation2021; Hsu et al., Citation2018), helps unpack the complexities of the principal-agent relationship within the framework of diverse business strategies. By applying the lens of agency theory, the study gains a comprehensive understanding of how managerial behaviors align with or deviate from shareholder interests in the context of varied business strategies, thereby enriching the theoretical foundation of the research.

On the other hand, signaling theory is an important theoretical fundamental integrated to understand the strategic use of dividend payments as communicative signals by firms. According to Miller and Rock (Citation1985), firms utilize dividend policies as a deliberate signaling mechanism to convey relevant information to external stakeholders, especially investors. This perspective aligns with the idea that dividends serve as a reliable signal of a firm’s financial health and growth potential, addressing information asymmetry and uncertainty. Contemporary contributions by Bentley et al. (Citation2013), Cao et al. (Citation2017), and Harakeh et al. (Citation2020), further enrich the signaling theory, emphasizing the strategic nature of dividend decisions and their implications for investor perceptions. In the context of diverse business strategies, signaling theory can explain how prospectors, defenders, and analyzers strategically deploy dividends to signal their unique characteristics and prospects. For instance, a prospector firm may use higher dividend payouts as a signal of its ability to manage increased risk and uncertainty, demonstrating financial stability and a commitment to shareholder value. In contrast, a defender firm, prioritizing stability and efficiency, might signal carefulness by maintaining lower dividend payouts and retaining earnings for potential internal investments. Through the integration of signaling theory into our theoretical framework, our investigation focuses on the landscape of dividend decisions, employing a perspective that recognizes the deliberate signaling strategies employed by firms with diverse business orientations.

4. Literature review and hypotheses development

4.1. Business strategy and dividend payments

The finance literature suggests that conflicts between managers and shareholders arise within a firm, leading to decisions that diminish shareholder wealth. Increased dividend payments can mitigate these conflicts by reducing cash flows available to managers, deterring private benefits and wealth expropriation (Easterbrook, Citation1984; Grossman & Hart, Citation1982; Jensen, Citation1986; Koo et al., Citation2017). In other words, the fundamental premise is that managers, driven by self-interest, may make choices that prioritize their private benefits and engage in wealth expropriation, leading to adverse implications for the broader shareholder base. However, agency theory contends that this conflict can be strategically managed, and one such mechanism is through increased dividend payments. By allocating a significant portion of earnings to shareholders in the form of dividends, firms can actively curtail the cash flows available to managers. This reduction acts as a deterrent, discouraging managers from pursuing avenues that may cater primarily to their personal gains at the expense of shareholder value. Thus, the agency theory perspective suggests that heightened dividend payments serve as a mechanism to mitigate conflicts of interest, foster a more equitable distribution of wealth, and align the incentives of managers with the broader shareholder base.

Signaling theory suggests that managers possess superior knowledge, and firms can use substantial dividends to convey positive signals, reassuring financial markets and attracting investors. One powerful tool in this signaling is the allocation of substantial dividends, which acts as a tangible demonstration of the firm’s financial health, stability, and growth potential. As the literature suggests, signaling through dividends serves the dual purpose of reassuring existing shareholders about the firm’s trajectory and attracting potential investors seeking promising opportunities. In the context of our study, the signaling theory becomes particularly significant when considering different business strategies. Previous research, as evidenced by Bentley et al. (Citation2013), Miles and Snow (Citation1978, Citation2003), Cao et al. (Citation2017), and Harakeh et al. (Citation2020), indicates that prospectors, in contrast to defenders, deal with heightened information asymmetry and agency conflicts. Facing greater uncertainty and risk, prospectors are compelled to communicate their growth potential and financial soundness more assertively, making substantial dividend payments a potent signaling mechanism. Hence, the literature on signaling theory aligns with the specific characteristics associated with prospector firms, highlighting their heightened incentives to strategically use dividends as a positive signal to reassure stakeholders and attract external financing sources. Our first hypothesis aligns with agency and signaling theories, considering the characteristics of prospectors:

Hypothesis H1: Firms with prospector strategies tend to pay more dividends than firms following defender strategies.

4.2. The role of information and governance environments

Prior literature argues that more precise, useful information and better corporate governance help mitigate insiders’ information advantage over outside investors. Lower information asymmetry and agency problems, in turn, alleviate the pressure on managers to demonstrate commitment via cash disbursement. Dividend payouts decrease consequently (Hail et al., Citation2014).

Existing studies show a negative association between the quality of a firm’s information environments and its corporate payout policy. For example, using a sample of Belgium-listed firms over the 1905–1909 period, Van Overfelt et al. (Citation2010) find that firms paying dividends have a less transparent income statement, supporting the notion that dividends are a substitute for income statement transparency. Employing a large global data set of 49 countries during the period from 1993 to 2008, Hail et al. (Citation2014) report that, following the improvement of the information environment (e.g., the mandatory adoption of IFRS and the initial enforcement of new insider trading laws), firms are less likely to pay dividends, and more likely to cut this payout. In other words, more information about firms mitigates the information asymmetry problem and results in firms with less reliance on dividend payments.

Besides, a body of empirical works views dividends as a governance substitute. For instance, Atanassov and Mandell (Citation2018) find support for the prediction that firms with weaker governance tend to exhibit higher dividends than better-governed firms. They argue that when governance is weak, managers must pay dividends to assure shareholders that they will not expropriate their investment. In better-governed firms, shareholders do not require dividend payouts as they believe that the managers will act on shareholders’ interests. In a similar vein, John et al. (Citation2015) document that firms subject to weak monitoring mechanisms are more likely to allocate a larger proportion of their payout to cash dividends. Jo and Pan (Citation2009) demonstrate that firms with entrenched managers are more likely to pay dividends. Additionally, Hu and Kumar (Citation2004) document a positive relation between dividends and CEO tenure, cash compensation, and board independence. Similarly, Gyapong et al. (Citation2021) employ a dataset of Australian listed enterprises to investigate the impact of corporate governance, particularly board gender diversity, on corporate dividend payouts. Their results reveal a positive correlation, indicating that a more gender-diverse board has a beneficial influence on dividend payments. Conversely, Elmagrhi et al. (Citation2017) employ a sample of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the UK and find a significant negative relationship between board gender diversity and the level of dividend payout. In a comprehensive review of literature spanning the last two decades, Das Mohapatra and Panda (Citation2022) systematically examine the nexus between corporate governance and dividend policy. Their findings reveal a prevailing trend across the majority of studies, indicating a positive association between enhanced corporate governance practices and increased dividend payouts.

Based on the above analyses, we predict that better information and governance environments help prospectors to reduce information asymmetry and agency conflicts, thereby lessening their dividend pressure. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H2: The positive association between prospector strategy and dividend payments is more pronounced for firms with weaker information quality and poorer governance environments.

4.3. The impact of policy uncertainty

Corporate dividend policy exhibits sensitivity to economic and political uncertainty, with arguments suggesting that dividend payouts can function as effective tools for firms to reassure investors and shareholders during periods of economic and political flux (Attig et al., Citation2021; Sarwar et al., Citation2020). The rationale posits that higher uncertainty amplifies the necessity of employing dividends as mechanisms of assurance.

Empirical studies substantiate that firms adjust their dividend policies in response to economic uncertainty. For instance, Buchanan et al. (Citation2017) investigate how firms react to uncertainty surrounding U.S. tax policy changes and find that firms tend to increase dividend payments one year before anticipated tax increases. Abreu and Gulamhussen (Citation2013) demonstrate that larger, more profitable, but low-growth banks increase dividend payouts before and during financial crises. This evidence suggests that dividends serve as signals of future growth opportunities, attracting debt and equity financing when needed, even during financial crises. Attig et al. (Citation2021) further support this notion by showing that firms pay higher dividends during periods of high Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU). They find that EPU has a stronger impact on dividends in family firms and those with concentrated ownership, which are prone to greater agency problems. Additionally, the positive correlation between EPU and dividend payouts is more pronounced in countries with weak investor protection, disclosure, securities regulation, and enforcement quality.

Firms also adjust their corporate decisions in response to electoral uncertainties, such as paying fewer taxes, reducing investment and hiring, and delaying financing (Durnev, Citation2013; Jens, Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2016). Given the uncertainty about the continuity of economic policies under incoming governments, managers, possessing better information about potential policy changes, contribute to increased information asymmetry between managers and outside investors surrounding elections (Durnev, Citation2013). This information asymmetry becomes a pivotal determinant of an increase in dividend payouts. Analyzing a substantial dataset covering six U.S. presidential elections from 1996 to 2016, Farooq and Ahmed (Citation2019) demonstrate that election years are associated with higher dividend payout ratios relative to non-election years. They affirm that information asymmetries linked to election years prompt firms to pay elevated dividends.

In this paper, we expect that increased information asymmetry and agency costs arising from economic and political uncertainty require prospectors to pay higher dividends. We formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H3: The positive association between prospector firms and dividend payments is more pronounced during high policy uncertainty.

5. Research design

5.1. Data and sample characteristics

To validate our hypotheses, we employ a sample comprising all U.S.-listed firms spanning the period from 1995 to 2018. We utilize the methodology established by Ittner et al. (Citation1997) and Miles and Snow (Citation1978, Citation2003) to quantify the business strategy variable, as outlined in Appendix 2. Firm characteristics and other control variables were collected from Compustat, the Thomson Reuters Institutional Holdings (13 F), I/B/E/S, and the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) database. Economic policy uncertainty and presidential election variables are taken from the website www.policyuncertainty.com And the Database of Political Institutions. The definition and measurement of all variables in our research models are described in Appendix 1. To ensure potential outlying observation control, we winsorize all continuous variables at the 1% and 99% levels. Initially, we selected a sample comprising all firms with a minimum of two years’ worth of data available in the Compustat database, resulting in an initial dataset of 51,671 firm-year observations. Subsequently, firms lacking both business strategy measures and dividend payment data were excluded. Following this screening process, our final analytical sample consisted of 47,536 firm-year observations.

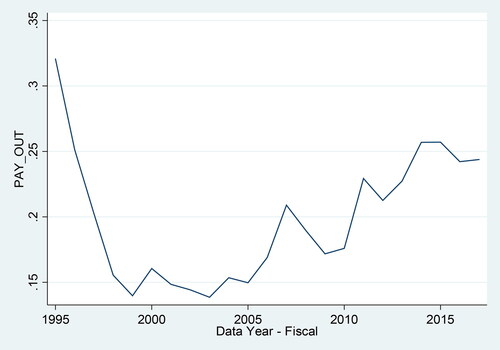

The findings presented in , indicating the dividend payout ratio of U.S. non-financial firms over the research period from 1995 to 2018, reveal a dynamic trend. The graph illustrates a substantial decline in the dividend payout ratio, dropping from its peak of approximately 0.325 in 1995 to a trough of 0.10 in the early 2000s. This sharp decrease implies that firms allocated a smaller portion of their earnings to dividends during this period. However, the subsequent recovery, though gradual, appears erratic, with the ratio gradually increasing and reaching nearly 0.25 by 2018. This observation suggests a fluctuating landscape of dividend policy decisions among non-financial firms over the years. The erratic nature of the recovery may indicate various external factors influencing firms’ dividend distribution strategies, such as economic conditions, industry-specific challenges, or shifts in corporate priorities.

Figure 1. Cross-sectional summary statistics for the dividend payout ratio for U.S. non-financial firms by year, from 1995 to 2018.

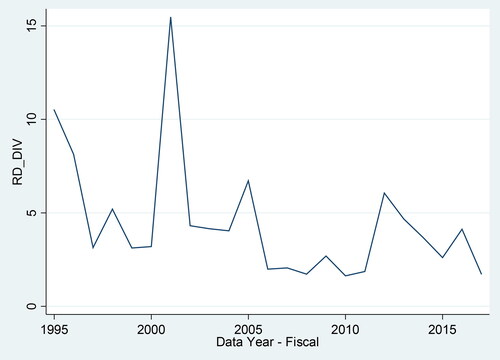

adds another layer of complexity by illustrating the pattern of R&D expenditure to dividend payouts by non-financial firms. The depiction is characterized by a considerable level of volatility throughout the analyzed period, suggesting fluctuations in the balance between investment in research and development (R&D) activities and the distribution of dividends. Despite the erratic pattern, an upward trend in recent years is noticeable. This upward trend in R&D expenditure relative to dividend payouts indicates an increasing emphasis on innovation and strategic investment in recent times. Firms seem to be allocating a larger share of their earnings to R&D activities, possibly reflecting a strategic response to technological advancements, competitive pressures, or changing market demands. This pattern aligns with the broader narrative of businesses prioritizing innovation and long-term growth strategies over immediate dividend distributions, suggesting a shift in corporate priorities.

5.2. Empirical model

The main model used for the panel regression analysis is illustrated in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . Each subsequent test then examines the relationship between dividend payments (DIVPAY) and corporate business strategy (PROSPECTOR) for a subset of the data appropriate for each hypothesis.

(1)

(1)

The dependent variable, denoted as DIVPAY, serves as an indicator for dividend payments, employing alternative proxies such as:

DIVEARN, known as the Dividend Payout Ratio. The calculation of DIVEARN involves deriving the ratio of total dividends paid to accounting earnings before extraordinary items (IB). Consistent with the methodology outlined by Holmen et al. (Citation2008), instances where dividends are paid when accounting earnings are negative are substituted with one. Additionally, if the resulting DIVEARN exceeds one, it is adjusted to one.

DIVSALE is another proxy, representing the ratio of total dividends paid divided by sales, multiplied by 100.

DIVCASH, the third proxy, is calculated as the ratio of total dividends paid to cash flow multiplied by 100.

These alternative proxies provide distinct perspectives on the relationship between dividend payments and various financial metrics, allowing for a comprehensive examination of the factors influencing dividend policies within the study framework.

The independent variable, denoted as PROSPECTOR, is a dummy variable which takes the value of one for prospector-type firms and zero for defender firms and analyzer firms. This variable is a composite measure encompassing six comprehensive elements. The average values are then ranked into quintiles per industry, with the highest quintile score of 5 and the lowest score of 1. The scores are summed over the six sub-measures per company-year, leading to a maximum score of 30 (considered prospector type) and a minimum score of 6 (considered defender type). For our analysis, we categorize firms with scores ranging from 6 to 12 as defenders, scores from 13 to 23 as analyzers, and scores of 24 or above as prospectors.

We also follow the existing literature (Cooper & Lambertides, Citation2018; Bhattacharya et al., Citation2020; and Attig et al.,Citation2021), to include the set of control variables (CONTROLS) with a one-year lag (as reported in Appendix 1), including firm size (SIZE), market to book (MB), leverage (LEV), operating performance (ROA), capital expenditure (CAPEX), retained earnings (RETA), the deviation of ROA (ROVOL), firm age (AGE), institutional ownership (IO), and analyst coverage (ANALYST). The correlation coefficients fall within acceptable ranges, as reported in Appendix 3.

The findings presented in offer a comprehensive analysis of dividend payouts across various dimensions, shedding light on patterns and disparities within the dataset. In Panel A, providing descriptive statistics for the entire sample, a detailed overview of each variable is presented. Panel B delves into the mean and median values for dividend payouts by industry, revealing variations in dividend distribution practices across different sectors. Particularly, the construction industry stands out with the lowest dividend payments, contrasting with transportation companies that exhibit the highest dividend payouts. This stark divergence emphasizes the industry-specific nature of dividend policies, influenced by unique economic factors, market conditions, and capital requirements inherent to each sector.

Table 1. Summary of sample characteristics.

In Panel C, we take a closer look at dividend payouts based on three distinct business strategies. The results highlight an important trend, indicating that defender firms consistently exhibit the lowest dividend payout ratios, while prospectors stand out with the highest ratios. This observation aligns with expectations derived from the study’s hypotheses and theoretical framework, reinforcing the view that business strategy plays a pivotal role in shaping dividend policies. The lower dividend payouts observed among defender firms suggest a conservative financial approach, possibly prioritizing internal investments or debt reduction over distributing profits to shareholders. On the contrary, prospectors, characterized by risk-taking and innovation, appear more inclined to allocate a higher proportion of earnings to dividends, possibly as a signaling mechanism or to manage agency conflicts.

6. Empirical findings

6.1. Baseline regressions

Our first hypothesis examines whether prospector firms are associated with higher dividend payouts by undertaking a panel regression of prospector business strategy on dividend payout and controlling a set of appropriate variables. The results of three models using alternative proxies for dividend payments with year and industry effects are presented in .

Table 2. The impact of business strategy on dividend payments.

Examining reveals compelling evidence in support of our first hypothesis. Across the three models utilizing alternative proxies for dividend payments, the coefficient of the PROSPECTOR variable is consistently positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that prospector firms exhibit a tendency to pay higher dividends. Previous research suggests that a substantial dividend payment can serve to alleviate agency conflicts by reducing available cash flows to managers, discouraging private benefits, wealth expropriation, and overinvestment (Easterbrook, Citation1984; Grossman & Hart, Citation1982; Jensen, Citation1986). Additionally, such dividend payments can convey positive signals about the firm’s prospects to investors in the context of information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders (Miller & Rock, Citation1985). Simultaneously, prospector firms are found to grapple with greater information asymmetry and agency conflicts compared to defenders or analyzers, leading them to rely heavily on external financing sources. Consequently, these firms have heightened incentives to address such issues, attracting capital providers by increasing the dividend payout ratio (Bentley et al., Citation2013; Miles & Snow, Citation1978, Citation2003). Our results support hypothesis H1 and suggest that augmenting cash disbursement assists prospector firms in cultivating a favorable market reputation, attracting more investors, and subsequently securing additional external resources.

6.2. Robustness tests

To verify the robustness of our regression results for the first hypothesis, we conduct several additional tests using alternative modeling techniques. Initially, we rerun the baseline regression while controlling for firm and year fixed effects, as outlined in . All other variables remain consistent with those in . The results across all models in align with the findings reported in , reinforcing the positive and significant correlation between prospector firms and dividend payouts, as indicated by the 1% level of significance for the PROSPECTOR variable.

Table 3. Firm and year fixed effects.

As mentioned earlier, in this study, we limit our focus on a sample of firms with prospector and defender strategies only. Therefore, we conduct the second robustness check by repeating our tests using a subsample of prospectors and defenders only. The results are provided in and are in line with those found in and . The direction and significance of coefficients for the PROSPECTOR variable hold for both sub-samples and therefore confirm the robustness of our results.

Table 4. Subsample with prospector vs. defender firms.

Finally, to address potential concerns related to endogeneity stemming from issues like the reverse causality problem and omitted variables, we perform various tests employing 2SLS regression and Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analysis. The first stage results of the 2SLS model are presented in , where corporate business strategy is predicted (Ex.PROSPECTOR) using prospector strategy as a dependent variable (PROSPECTOR). The five-year lagged business strategy serves as an instrument in the first stage. The results reveal a positive and statistically significant coefficient (0.6981) for L1.PROSPECTOR at the 1% level, affirming the positive relationship between the instrument and prospector strategy. Subsequently, also provides the results of the second stage of the 2SLS model, demonstrating that the coefficients of the instrumented variables are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests the robustness of our findings even after correcting for endogeneity.

Table 5. Endogeneity.

Moving forward, presents the panel regression of dividend payments on corporate business strategy utilizing PSM analysis. In Panel A, we observe the average treatment effects obtained from PSM, with firms possessing high business strategy scores (above the yearly two-digit SIC industry median) constituting the treatment group, and those with low business strategy scores as the control group. Panel B presents the results based on PSM regression. Panel A indicates that all variables are closely matched with no significant differences. The results of the panel regression, incorporating year (Y) and industry (I) fixed effects, are detailed in Panel B. Consistent with the findings in the preceding tables, PROSPECTOR remains significant and positive with strong significance across all specifications.

Table 6. Propensity score matching analysis.

In short, after conducting a series of tests controlling for firm and year fixed effects, employing different subsamples with separate prospectors and defenders, and addressing potential endogeneity concerns, our findings remain robust and suggest that firms adopting a prospector-type strategy tend to pay more dividends than defenders.

6.3. Prospector firms, corporate overinvestment and capital expenditure

This section investigates the possible underlying channels driving the positive correlation between business strategy and dividend payments. We would like to examine whether business strategy raises dividend payments via its impact on firm overinvestment and capital expenditure. Prior studies suggest that agency conflicts provide managers with incentives to maximize their private interests through retaining cash inside the firm instead of paying dividends or investing in negative NPV projects at the expense of shareholders (Ding et al., Citation2019; Fu, Citation2010; Liu & Bredin, Citation2010). Shi and Gao (Citation2018) also argue that with the availability of excess free cash flow, managers have incentives to use the discretionary funds under their control to seek individual benefits that lead to overinvestment. Increasing dividend payments mitigates such potential agency conflicts and helps alleviate the overinvestment problem with the lower cash flows available to managers (Easterbrook, Citation1984; Grossman & Hart, Citation1982; Jensen, Citation1986).

Moreover, Lang and Litzenberger (Citation1989) state that reducing overinvestment can enhance firm value and increase dividend payments. Navissi et al. (Citation2017) argue that prospectors are more likely to over-invest than defenders due to greater information asymmetry and agency conflicts between managers and outside investors in prospector firms. We, therefore, expect that the prospector strategy will be positively correlated with overinvestment, and through this channel, with dividend payments.

Furthermore, motivated by the study of Denis et al. (Citation1994) on the correlation between capital expenditures and dividend changes, we also examine whether business strategy options exert different impacts on capital expenditure. Prior studies affirm that prospectors are associated with non-capital expenditure, especially in the form of R&D, but exhibit low capital expenditure (Maury, Citation2021; Navissi et al., Citation2017), whereas defenders are efficiency-oriented and maintain a lower level of R&D intensity in support of investing in capital expenditures (Hambrick, Citation1983; Miles & Snow, Citation1978, Citation2003). Accordingly, it is expected that the prospector strategy is negatively correlated with capital expenditure.

presents the panel regression of the impact of business strategy on overinvestment and capital expenditure. OVERINVEST (overinvestment) and CAPEX (capital expenditure) are the dependent variables in our models. We follow Biddle et al. (Citation2009) to construct our measure of overinvestment. The OVERINVEST variable is ranked by the mean of a decile-based measure of cash and leverage. We multiply leverage by minus one before ranking, so that the variable increases in the tendency of overinvestment. The key explanatory variable, PROSPECTOR, is a dummy variable that takes the value of one for prospector-type firms and zero for defenders. A set of control variables includes firm size (SIZE), market-to-book ratio (MB), loss (LOSS), cash holdings (CASH), cash flow volatility (CFVOL), sale volatility (SALEVOL), investment volatility (INVESTVOL), firm age (AGE), financial distress (Z-Score), tangibility (TANG), operating net cash flow to sales (CFO/SALE), dividend status (DIVDUM), operating cycle (CYCLE), institutional ownership (IO), and analyst coverage (ANALYST).

Table 7. The effects of business strategy on corporate overinvestment and capital expenditure.

The results in indicate that the coefficient for the PROSPECTOR variable is positive at the significance level of 5% for the model in Column (1), but significantly negative at the 1% level for the model in Column (2). The results are consistent with our expectations that prospectors are more likely to engage in overinvestment compared to defenders, which may result in higher dividend payments. The finding also indicates that firms adopting a prospector strategy experience lower capital expenditure than those following a defender strategy. This evidence suggests that one possible mechanism linking business strategy and dividend policy is a reduction in capital expenditure that may raise the agency costs of free cash flow excess in prospectors.

6.4. Information and governance environments and dividend payments

We continue investigating our understanding of the moderating effect of information and governance environments on the association between prospector business strategy and dividend payments (Hypothesis H2). Prior studies argue that the availability of precise and useful information and the betterment of corporate governance help mitigate insiders’ information advantage over outside investors, which in turn alleviates the pressure on managers to demonstrate commitment via cash disbursement, and subsequently leads to lower dividend payouts (Atanassov & Mandell, Citation2018; Hail et al., Citation2014; John et al., Citation2015). Therefore, we predict that better information and governance environments help prospectors reduce the level of information asymmetry and agency conflicts, which lessen their dividend pressure.

To test the hypothesis, we initially examine how information asymmetry influences the relationship between business strategy and dividend payments. To proxy information asymmetry, we employ the probability of insider trading (PIN) and the financial statement opacity (OPAQUE) variables. Following the theoretical framework outlined by Easley and O’Hara (Citation1987), we calculate the probability of insider trading (PIN) by analyzing imbalances between buy and sell trades, estimating the likelihood of informed and uninformed information events. The OPAQUE variable represents the moving sum of the absolute value of discretionary accruals over the three-year period from t-1 to t-3, with discretionary accruals computed using the modified Jones model (Dechow et al., Citation1995). Throughout the sample period, we categorize firms into High and Low sets based on the median value of each measure for empirical estimation, maintaining consistency with all other variables in our tests. The results are presented in .

Table 8. Information environment, business strategy and dividend payments.

Panel A presents the result of the moderating effect of the probability of insider trading (PIN), which promotes a positive relationship between prospector firms and dividend payouts. However, the association is more explicit and displays more significance when there is a high probability of insider trading than the association in the case of a low probability of insider trading. For HighPIN, the coefficients of PROSPECTOR are positive and statistically significant in three models with alternative proxies of dividend payments at the 1% and 10% level, whereas for the LowPIN group, the coefficient of PROSPECTOR is positive, but insignificant in the model with DIVSALE proxy.

We further examine how financial statement opacity (OPAQUE) impacts the core relationship of our study as demonstrated in Panel B. Similarly, the results for the effect of financial statement opacity on dividend payments for prospector firms are more significant in the More OPAQUE group of firms for three alternative models at the 1% and 10% levels. For the Less OPAQUE set, PROSPECTOR is found to be insignificant to explain for DIVSALE and DIVCASH. The findings align with our prediction that the positive association between prospector firms and dividend payouts is promoted when the firm-level information environment is not transparent.

We continue testing our second hypothesis on the moderating effect of the governance environment on the business strategy—dividend payment relation. It is argued that firms with weaker governance mechanisms tend to raise higher dividends than better-governed firms (Atanassov & Mandell, Citation2018; John et al., Citation2015). In the study, we use the external market for corporate control measured by the index of takeover susceptibility (TSIND) developed by Cain et al. (Citation2017) as a proxy for governance quality. The index measures the likelihood of a hostile acquisition, in which a higher takeover susceptibility index suggests a greater probability of being taken over and, therefore, indicates weaker protections for corporate governance. Likewise, for the information measure, we split the firms by the median value into two categories as high and low for each given fiscal year for our estimation. We report the results of the regression in . The results again confirm our prediction. The positive coefficients of the PROSPECTOR variable are more statistically significant in the High TSIND set, which supports our view that the prospector strategy does increase dividend payments to a greater extent in firms with weaker governance mechanisms, as reflected by higher takeover protection.

Table 9. Corporate Governance, business strategy and dividend payments.

6.5s. Political uncertainty and dividend payments

We perform testing our final hypothesis on the effect of economic and political uncertainty on the dividend payments of prospector firms. Attig et al. (Citation2021) argued that firms use dividends as an effective tool to assure investors and shareholders when faced with uncertain situations due to economic and political changes. Besides, it is studied that the information asymmetries are exaggerated in election years (Durnev, Citation2013), which induce firms to pay high dividends. Farooq and Ahmed (Citation2019) also point out that higher dividend payouts are associated with election years relative to non-election years. Pursuing risky and innovative projects, prospector firms’ growth outcome seems more uncertain and particularly sensitive to such unexpected changes relative to defender counterparts (Bentley et al., Citation2013; Kester, Citation1984; Myers, Citation1977; Rajagopalan, Citation1997). Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that increased information asymmetry and agency costs arising due to economic and political uncertainty require prospectors to pay higher dividends.

outlines the findings regarding the relationship between business strategy and dividend payments, specifically considering the influence of U.S. policy uncertainty. Economic policy uncertainty and U.S. Presidential elections (ELECT) serve as proxies for U.S. policy uncertainty in our analysis. In Panel A, we examine the impact of economic policy uncertainty on the dividend payments of prospector firms. The EPU variable is derived from the monthly economic policy uncertainty index developed by Baker et al. (Citation2016). Subsequently, by using median values for EPU, we categorize firms into High EPU and Low EPU groups for each fiscal year. Our results exhibit statistical significance in both the High EPU and Low EPU groups regarding the impact of prospector strategy on dividend payments. Particularly, the coefficient for PROSPECTOR is marginally higher for the High EPU group, aligning with the hypothesis H3 that prospector firms tend to pay higher dividends under conditions of elevated policy uncertainty.

Table 10. Policy uncertainty, business strategy and dividend payments.

Panel B examines how our main association is impacted by the U.S. presidential elections. We use a dummy variable, taking the value one if the USA holds a presidential election in year t (ELECT) and zero otherwise (Non-ELECT). The coefficients of the PROSPECTOR variable are higher and more significant at the 1% and 10% levels in three alternative models of the ELECT group that imply a stronger association between prospector business strategy and dividend payments during the presidential elections. Meanwhile, this association is insignificant during non-election periods for dividend payments proxied by DIVSALE and DIVCASH. These findings support our third hypothesis.

7. Summary and conclusion

This paper argues the articulation between prospector strategy and dividend policy from an agency costs perspective. The firm’s decision as to whether to distribute profits to shareholders through dividends or to retain profits to invest within the firm is a sensitive decision from an agency theory perspective, since there is a possibility that the management may retain profits to satisfy their own rather than shareholders’ interests. Jensen (Citation1986) demonstrates that a dividend acts as a mechanism to reduce agency costs, particularly in firms with substantial free cash flows, by restricting management access to such funds. Our core contention is that firms with a prospector strategy experience higher information asymmetry and, therefore, pay more dividends than defender firms. We provide compelling new evidence to indicate that the prospector strategy indeed has a significant and positive effect on dividend payments. Our findings are robust after controlling for firm fixed effects, use of alternative modeling approaches, and methods to address potential endogeneity issues related to business strategy. We further find that, given the importance of investment and free cash flows to agency-related problems, overinvestment and capital expenditure are the underlying channels driving the positive association between prospector firms and dividend payments. In addition to providing convincing support for our basic tenet, we investigate how the positive relation between prospector strategy and dividend payments differs across different information and governance environments. We find that the relationship is more pronounced for firms with higher levels of information asymmetry and weak governance mechanisms. More importantly, we document that the relationship is more affected in times of higher policy uncertainty measured by economic policy uncertainty and presidential elections.

This research carries significant relevance for various stakeholders in the financial landscape. Firstly, the observed higher propensity for dividend payments in firms employing prospector strategies compared to defender firms suggests that investors may benefit from incorporating strategic considerations into their stock selection process. Understanding a firm’s strategic orientation could serve as a valuable indicator of its likelihood to distribute dividends, providing investors with insights into potential income planning. Further, the identification of agency conflict issues related to free cash flow in prospector firms sheds light on the complex relationship between strategic decisions, financial policies, and corporate governance. Investors and financial analysts should consider these dynamics when evaluating investment opportunities, especially in environments characterized by weaker information and governance structures or heightened policy uncertainty.

While this research makes valuable contributions to understanding the nexus between business strategy and dividend payments, we acknowledge certain limitations of its findings. Firstly, the chosen time frame from 1995 to 2018 might not fully capture more recent shifts in business strategies or changes in the financial landscape. Moreover, while the research attempts to address endogeneity through various methodologies such as firm fixed effects and PSM, there may still be unobserved variables or omitted variable bias that could influence the study’s outcomes. Lastly, the study assumes rational decision-making by firms in terms of selecting and executing their business strategies. However, behavioral biases, organizational politics, and cognitive limitations among executives may introduce deviations from purely rational choices that the study does not explicitly address.

Overall, this study provides promising directions for future research. A deeper investigation of behavioral aspects manipulating strategic decisions, including managerial risk attitudes and management communications, could provide a more thoughtful understanding of the association between business strategy and dividend payments. Future research could also focus on alternative payout mechanisms beyond dividends, such as share repurchases.

Author contributions

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. Conception and design of study: Viet Anh Hoang, Thanh Huong Nguyen, My Hanh Nguyen. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: Viet Anh Hoang, Thanh Huong Nguyen, My Hanh Nguyen, Ba Thanh Truong. Drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content: Viet Anh Hoang, Thanh Huong Nguyen, My Hanh Nguyen, Ba Thanh Truong

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Collins Ntim (Academic Editor) and the anonymous referees for very helpful comments and suggestions. We thank Premkanth Puwanenthiren for sharing his data, the participants at the 2020 Australasian Finance and Banking Conference, the 2021 Financial Markets and Corporate Governance Conference, and the seminar at the University of Danang, University of Economics, for very fruitful comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Viet Anh Hoang

Viet Anh Hoang and My Hanh Nguyen are senior lecturers at Department of Banking, the University of Danang, University of Economics (Vietnam).

Thanh Huong Nguyen

Thanh Huong Nguyen is a senior lecturer at Department of Finance, the University of Danang, University of Economics (Vietnam).

My Hanh Nguyen

Viet Anh Hoang and My Hanh Nguyen are senior lecturers at Department of Banking, the University of Danang, University of Economics (Vietnam).

Ba Thanh Truong

Ba Thanh Truong is a professor at Department of Accounting, the University of Danang, University of Economics (Vietnam).

References

- Aboody, D., & Lev, B. (2000). Information asymmetry, R&D, and insider gains. The Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2747–2766. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00305

- Abreu, J. F., & Gulamhussen, M. A. (2013). Dividend payouts: Evidence from US bank holding companies in the context of the financial crisis. Journal of Corporate Finance, 22, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.04.001

- Akindayomi, A., & Amin, M. R. (2022). Does business strategy affect dividend payout policies? Journal of Business Research, 151, 531–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.07.028

- Allen, F., & Michaely, R. (1995). Dividend policy. Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, 9, 793–837.

- Alzahrani, M., & Lasfer, M. (2012). Investor protection, taxation, and dividends. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(4), 745–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2012.06.003

- Armstrong, C. S., Gow, I. D., & Larcker, D. F. (2013). The efficacy of shareholder voting: Evidence from equity compensation plans. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(5), 909–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12023

- Atanassov, J., & Mandell, A. J. (2018). Corporate governance and dividend policy: Evidence of tunneling from master limited partnerships. Journal of Corporate Finance, 53, 106–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.10.004

- Attig, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Zheng, X. (2021). Dividends and economic policy uncertainty: international evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101785

- Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2016). Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1593–1636. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw024

- Barth, M. E., Kasznik, R., & McNichols, M. F. (2001). Analyst coverage and intangible assets. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00001

- Bataineh, H. (2021). The impact of ownership structure on dividend policy of listed firms in Jordan. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1863175. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1863175

- Ben-David, I. (2010). Dividend policy decisions. Behavioral Finance: Investors, Corporations, and Markets. John Wiley & Sons. 435–451.

- Bentley, K. A., Omer, T. C., & Sharp, N. Y. (2013). Business strategy, financial reporting irregularities, and audit effort. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(2), 780–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2012.01174.x

- Bentley-Goode, K. A., Newton, N. J., & Thompson, A. M. (2017). Business strategy, internal control over financial reporting, and audit reporting quality. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(4), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51693

- Bhattacharya, D., Chang, C. W., & Li, W. H. (2020). Stages of firm life cycle, transition, and dividend policy. Finance Research Letters, 33, 101226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.06.024

- Biddle, G. C., Hilary, G., & Verdi, R. S. (2009). How does financial reporting quality relate to investment efficiency? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(2-3), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.09.001

- Bizjak, J. M., Brickley, J. A., & Coles, J. L. (1993). Stock-based incentive compensation and investment behavior. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 16(1-3), 349–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(93)90017-A

- Black, F., & Scholes, M. (1974). The effects of dividend yield and dividend policy on common stock prices and returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 1(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(74)90006-3

- Bliss, B. A., Cheng, Y., & Denis, D. J. (2015). Corporate payout, cash retention, and the supply of credit: Evidence from the 2008–2009 credit crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(3), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.10.013

- Brav, A., Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Michaely, R. (2008). The effect of the May 2003 dividend tax cut on corporate dividend policy: Empirical and survey evidence. National Tax Journal, 61(3), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2008.3.03

- Brockman, P., Ma, T., & Ye, J. (2015). CEO compensation risk and timely loss recognition. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 42(1-2), 204–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12100

- Brockman, P., Tresl, J., & Unlu, E. (2014). The impact of insider trading laws on dividend payout policy. Journal of Corporate Finance, 29, 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.09.002

- Brown, J. R., Liang, N., & Weisbenner, S. (2007). Executive financial incentives and payout policy: Firm responses to the 2003 dividend tax cut. The Journal of Finance, 62(4), 1935–1965. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01261.x

- Buchanan, B. G., Cao, C. X., Liljeblom, E., & Weihrich, S. (2017). Uncertainty and firm dividend policy: A natural experiment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 42, 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.11.008

- Cain, M. D., McKeon, S. B., & Solomon, S. D. (2017). Do takeover laws matter? Evidence from five decades of hostile takeovers. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3), 464–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.04.003

- Cao, L., Du, Y., & Hansen, J. O. (2017). Foreign institutional investors and dividend policy: Evidence from China. International Business Review, 26(5), 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.02.001

- Chen, M. A., Greene, D. T., & Owers, J. E. (2015). The costs and benefits of clawback provisions in CEO compensation. Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 4(1), 108–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfu012

- Chen, G. Z., & Keung, E. C. (2019). The impact of business strategy on insider trading profitability. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 55, 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2019.04.007

- Chen, J., Leung, W. S., & Goergen, M. (2017). The impact of board gender composition on dividend payouts. Journal of Corporate Finance, 43, 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.01.001

- Chetty, R., & Saez, E. (2005). Dividend taxes and corporate behavior: Evidence from the 2003 dividend tax cut. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 791–833.

- Collins, F., Holzmann, O., & Mendoza, R. (1997). Strategy, budgeting, and crisis in Latin America. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(7), 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(96)00050-5

- Cooper, I. A., & Lambertides, N. (2018). Large dividend increases and leverage. Journal of Corporate Finance, 48, 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.10.011

- Dang, M., Puwanenthiren, P., Jones, E., Nguyen, T. Q., Vo, X. V., & Nadarajah, S. (2022). Strategic archetypes, credit ratings, and cost of debt. Economic Modelling, 114, 105917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105917

- Das Mohapatra, D., & Panda, P. (2022). Impact of corporate governance on dividend policy: A systematic literature review of last two decades. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2114308. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2114308

- De Cesari, A., & Huang-Meier, W. (2015). Dividend changes and stock price informativeness. Journal of Corporate Finance, 35, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.08.004

- DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., & Stulz, R. M. (2006). Dividend policy and the earned/contributed capital mix: a test of the life-cycle theory. Journal of Financial Economics, 81(2), 227–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.07.005

- Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225.

- Denis, D. J., Denis, D. K., & Sarin, A. (1994). The information content of dividend changes: Cash flow signaling, overinvestment, and dividend clienteles. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 29(4), 567–587. https://doi.org/10.2307/2331110

- Ding, S., Knight, J., & Zhang, X. (2019). Does China overinvest? Evidence from a panel of Chinese firms. The European Journal of Finance, 25(6), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2016.1211546

- Dionne, G., & Ouederni, K. (2011). Corporate risk management and dividend signaling theory. Finance Research Letters, 8(4), 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2011.05.002

- Durnev, A. (2013). The Real Effects of Political Uncertainty: Elections and Investment Sensitivity to Stock Prices. Working Paper, McGill University, Canada.

- Easley, D., & O’Hara, M. (1987). Price, Trade Size and Information in Securities Markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 19(1), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(87)90029-8

- Easterbrook, F. (1984). Two agency cost explanations of dividends. American Economic Review, 74, 650–659.

- Efthymiou, V. A., Episcopos, A., Leledakis, G. N., & Pyrgiotakis, E. G. (2021). Intraday analysis of the limit order bias on the ex-dividend day of U.S. common stocks. International Review of Economics & Finance, 72, 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2020.11.017

- Elmagrhi, M. H., Ntim, C. G., Crossley, R. M., Malagila, J. K., Fosu, S., & Vu, T. V. (2017). Corporate governance and dividend pay-out policy in UK listed SMEs: The effects of corporate board characteristics. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 25(4), 459–483. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-02-2017-0020

- Fang, H., Song, Z., Nofsinger, J. R., & Wang, Y. (2017). Trading restrictions and firm dividends: The share lockup expiration experience in China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 85, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.08.012

- Farinha, J. (2003). Dividend policy, corporate governance and the managerial entrenchment hypothesis: an empirical analysis. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 30(9-10), 1173–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0306-686X.2003.05624.x

- Farooq, O., & Ahmed, N. (2019). Dividend policy and political uncertainty: Evidence from the US presidential elections. Research in International Business and Finance, 48, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.01.003

- Firth, M., Gao, J., Shen, J., & Zhang, Y. (2016). Institutional stock ownership and firms’ cash dividend policies: Evidence from China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 65, 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.01.009

- Floyd, E., Li, N., & Skinner, D. J. (2015). Payout policy through the financial crisis: The growth of repurchases and the resilience of dividends. Journal of Financial Economics, 118(2), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.08.002

- Fu, F. (2010). Overinvestment and the operating performance of SEO firms. Financial Management, 39(1), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2010.01072.x

- Grinstein, Y., & Michaely, R. (2005). Institutional holdings and payout policy. The Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1389–1426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00765.x

- Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1982). Corporate financial structure and managerial incentives. The Economics of Information and Uncertainty, University of Chicago Press.

- Grullon, G., Michaely, R., & Swaminathan, B. (2002). Are dividend changes a sign of firm maturity? The Journal of Business, 75(3), 387–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/339889

- Gyapong, E., Ahmed, A., Ntim, C. G., & Nadeem, M. (2021). Board gender diversity and dividend policy in Australian listed firms: the effect of ownership concentration. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(2), 603–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09672-2

- Habib, A., & Hasan, M. M. (2017). Business strategy, overvalued equities, and stock price crash risk. Research in International Business and Finance, 39, 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2016.09.011

- Habib, A., & Hasan, M. M. (2021). Business strategy and labor investment efficiency. International Review of Finance, 21(1), 58–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/irfi.12254

- Hail, L., Tahoun, A., & Wang, C. (2014). Dividend payouts and information shocks. Journal of Accounting Research, 52(2), 403–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12040

- Hambrick, D. C. (1981). Environment, strategy, and power within top management teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(2), 253–275.

- Hambrick, D. C. (1983). Some tests of the effectiveness and functional attributes of Miles and Snow’s strategic types. Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management, 26(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/256132

- Harakeh, M., Matar, G., & Sayour, N. (2020). Information asymmetry and dividend policy of Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Journal of Economic Studies, 47(6), 1507–1532. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-08-2019-0355

- Herusetya, A., Sambuaga, E. A., & Sihombing, S. O. (2023). Business strategy typologies and the preference of earnings management practices: Evidence from Indonesian listed firms. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2161204. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2161204

- Higgins, D., Omer, T. C., & Phillips, J. D. (2015). The influence of a firm’s business strategy on its tax aggressiveness. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(2), 674–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12087

- Holmen, M., Knopf, J. D., & Peterson, S. (2008). Inside shareholders’ effective tax rates and dividends. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(9), 1860–1869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.12.048

- Hsu, P. H., Moore, J. A., & Neubaum, D. O. (2018). Tax avoidance, financial experts on the audit committee, and business strategy. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 45(9-10), 1293–1321. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12352

- Hu, A., & Kumar, P. (2004). Managerial entrenchment and payout policy. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(4), 759–790. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109000003203

- Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F., & Rajan, M. V. (1997). The choice of performance measures in annual bonus contracts. The Accounting Review, 72(2), 231–255.

- Jens, C. E. (2017). Political uncertainty and investment: Causal evidence from US gubernatorial elections. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.01.034

- Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review, 76(2), 323–329.

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Jo, H., & Pan, C. (2009). Why are firms with entrenched managers more likely to pay dividends? Review of Accounting and Finance, 8(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/14757700910934256

- John, K., Knyazeva, A., & Knyazeva, D. (2015). Governance and payout precommitment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 33, 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.05.004

- Kester, W. C. (1984). Today’s options for tomorrow’s growth. Harvard Business Review, 62, 153–160.

- Koo, D. S., Ramalingegowda, S., & Yu, Y. (2017). The effect of financial reporting quality on corporate dividend policy. Review of Accounting Studies, 22(2), 753–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9393-3

- Kwak, B., Ro, B. T., & Suk, I. (2012). The composition of top management with general counsel and voluntary information disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54(1), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2012.04.001

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2000). Agency problems and dividend policy around the world. The Journal of Finance, 55(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00199

- Lang, L. H., & Litzenberger, R. H. (1989). Dividend announcements: cash flow signalling vs free cash flow hypothesis? Journal of Financial Economics, 24(1), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(89)90077-9

- Li, Q., Maydew, E., Willis, R., & Xu, L. (2016). Corporate Tax Avoidance and Political Uncertainty: Evidence from National Elections Around the World. Working Paper, University of North Carolina USA.

- Liu, N., & Bredin, D. (2010). Institutional investors, over-investment and corporate performance. University College Dublin.

- Li, K., & Zhao, X. (2008). Asymmetric information and dividend policy. Financial Management, 37(4), 673–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2008.00030.x