?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Country image, brand image, and warranty knowledge are essential for evaluation and decision-making. This study examines the effects of these three variables on the purchase intentions of a car as a high-involvement product with high-risk attributes. This study investigates the role of consumer knowledge of essential product external cues, namely product warranty, which is relevant mainly for risk-averse consumers. Specifically, the present research tests the moderating effects of two categories of product warranty knowledge, subjective and objective, on the relationship between country image and brand image on purchase intentions in two different consumption situations: personal and business. The current study applies a quantitative approach and collected data through a survey of 386 respondents who are the owners and managers of car rental service providers in Central Java, Indonesia. The hypothesis was tested using structural equation modeling, and the findings indicate the significant effects of country image and brand image on purchase intentions in personal and business settings. Further tests demonstrate that only subjective warranty knowledge moderates the relationship between country image and purchase intentions but not the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions in personal and business backgrounds. This study offers several managerial implications for future research, particularly when comparing the models of individual and business consumers.

Introduction

The automotive industry has made a significant direct and indirect contribution to the Indonesian economy, creating five million jobs and contributing 20% of non-oil and gas sector revenue (Kiki, Citation2022). Accordingly, to revitalize the automotive industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the government provides incentives through sales tax exemption on luxury goods for automotive sales (Kusumastuti, Citation2022). Price and other factors undoubtedly influence car purchasing decisions, including the country of origin (Han, Citation2020). The country-of-origin effect serves as an indicator of product quality for consumers with limited product knowledge (i.e. halo effect) and also for consumers who use the country of origin as a cue that summarizes their knowledge and experience of using products from a particular country (i.e. summary effect) (Knight & Calantone, Citation2000). The international business literature has focused on evaluating the significance of the country of origin’s effect on the purchase decisions for tangible products such as cars (Bartikowski et al., Citation2019), cosmetics (Hsu et al., Citation2017), food (Jin et al., Citation2020), and services such as medical tourism (Schmerler, Citation2019).

Compared to other countries, Japanese car manufacturers dominate car sales in Indonesia (Negara & Hidayat, Citation2021). The dominance of Japanese vehicles corresponds with reliability, fuel efficiency, and low costs of repair and maintenance associated with Japanese cars (Allcot, Citation2024). Alongside the dominance of Japanese vehicles, only one Chinese car brand can rank among the top 10 car brands with the highest sales in Indonesia in 2023 (The Association of Indonesia Automotive Industry, Citation2024). However, market players continue to harbor doubts regarding Chinese car brands, which are considered to have several deficiencies concerning engine durability, spare part availability, and service quality (Wahyu, Citation2018). Therefore, a Chinese car manufacturer implemented a long-term product warranty to mitigate the perception of high risk associated with its products (Tolok, Citation2019).

A product warranty is a mechanism to mitigate the risks associated with product purchases, particularly for Asian consumers with a propensity for risk aversion and increased sensitivity to loss (Han & Kim, Citation2017). It is a cognitive signal that signifies a company’s commitment to fulfilling consumers’ expectations (Martín et al., Citation2011). The absence of a product warranty may deter consumers from purchasing products, especially when the products are expensive and require direct inspections (Clemes et al., Citation2014). In this respect, car purchases highly involve consumers’ decision-making (Dahiya, Citation2018) because of the amount of committed financial resources, potential performance, and technological and physical risks. Therefore, consumers’ product knowledge, including product warranty knowledge, is essential in car buying decisions. Product warranties reduce risks, especially when consumers’ decisions likely lead to unfavorable consequences. Product warranty knowledge is particularly critical in evaluating products with unfavorable country image.

Situational factors affect consumers’ decision-making (Filiatrault & Ritchie, Citation1988). Situational factors include purchasing, consumption, and communication (Liang & Yeh, Citation2009). End consumers may develop risk perceptions due to situational factors (Ramtiyal et al., Citation2022). Consumers prioritize or evaluate risk factors, especially when they are highly involved in decision-making (Mitchell, Citation1998). Consumers evaluate high-involvement products when the products are considered critical, such as expensive products, those associated with performance risks, complex products, and products associated with consumer ego (Assael, Citation2005). Consumer behavior varies when goods are acquired for personal use. To illustrate, gift-giving circumstances elicit distinct purchasing behaviors and product preferences compared to personal use (Dominici et al., Citation2021).

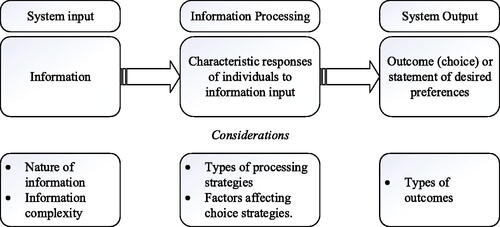

The current study utilizes the psychology theory perspective, particularly cognitive theory (i.e. information processing theory), as the theoretical foundation (Tybout et al., Citation1981). Consumers acquire process, learn, and use information for decision-making. The consumer Information Processing System (CIPS) framework establishes the three phases through which consumers develop: system inputs, information processing, and system output (Chestnut & Jacoby, Citation1977). The framework aligns with the stimulus-organism-response paradigm (Kotler & Levy, Citation1969). Information regarding objects, situations, or behavior in a particular situation is derived from internal stimuli (e.g. prior experience) and external stimuli (e.g. marketing efforts). Aside from country image and brand image, which function as external stimuli, knowledge of warranty serves as an internal stimulus that significantly affects behavioral variables.

Image constructs, consumption situations, and warranty knowledge are associated with risk attributes in consumer decision-making, particularly among Asian consumers (Han & Kim, Citation2017). Nevertheless, previous studies mainly investigate the role of the constructs within the context of individual consumers, with a lack of studies focusing on the setting of business or organization consumers. Accordingly, the current study aims to fill the gap by examining the effects of image constructs (i.e. country image and brand image) on car purchase intentions from the perspective of business consumers (i.e. car rental service providers). The business owners or managers evaluate and demonstrate their likelihood to purchase a car for two different consumption situations (business vs. personal).

Furthermore, the current study breaks down the analysis by examining the role of warranty knowledge (subjective vs. objective) in enhancing the effects of country and brand image on car purchase intentions for each type of consumption situation. Therefore, the current study proposes the following research questions: First, do country image and brand image affect car purchase intentions based on types of consumption situations? Second, does warranty knowledge moderate the effect of image constructs (i.e. county and brand image) on car purchase intentions based on consumption situations? The research object was Wuling, a Chinese automotive brand that has been present in the Indonesian market since 2017 (Wuling, Citation2023), which encountered the following challenges: (1) becoming an emerging brand that competes with well-established car brands, especially those from Japan, (2) confronting the stereotypes associated with a negative country image that is linked to a brand (On Marketing, 2015), despite efforts to enhance the reputation of Chinese products (Shepard, Citation2016).

Literature review and hypotheses development

Various theoretical backgrounds have been used to understand consumer behavior. Scholars utilize several perspectives, such as rational, behavioral, cognitive, motivational, personality, attitudinal, and situational (Pachauri, Citation2001). The cognitive perspective, as one of the perspectives, assumes that consumers function as ‘information processors’ (Bray, Citation2008). Cognitive perspective-based information processing theory explains how consumers seek, perceive, learn, remember, and develop purchase or preference decisions regarding products and brands. The Consumer Information Processing Model (CIPS) () illustrates the sequence of processes (Chestnut & Jacoby, Citation1977), and the model corresponds with the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R), which was initially proposed as the paradigm in consumer behavior research by Kotler and Levy (Citation1969).

Figure 1. Consumer Information Processing System.

Source: Chestnut and Jacoby (Citation1977).

The theoretical foundation of the present study is established on a cognitive perspective, with information processing theory serving as the foundation for the proposed research model (Shao et al., Citation2021). Internal signals manifest as product attributes and specifications (Choi et al., Citation2018). External cues are expressed as country of origin, brand, price, and warranty (Lee & Lee, Citation2009). Two image constructs (i.e. country and brand image) serve as stimuli that consumers receive and process to form an expected response (i.e. purchase intentions). The current study considers several factors that potentially intervene the information processing, such as consumer ability to retain information (i.e. consumer knowledge of warranty), the nature of product involvement (i.e. car as a high involvement product associated with high risks), and situational factors (i.e. consumption situation: personal vs business use). Such factors potentially moderate the influences of country and brand image on purchase intentions. The interaction of such constructs indicates the complexity of decision-making.

Consumption situation in decision-making

Environmental factors may influence consumer behavior, and the situationist paradigm explains that consumer behavior is a response function determined by circumstances, contexts, or use situations (Arndt, Citation1986). One situational variable is the context of use (Ramtiyal et al., Citation2022) and purchase and communication situations (Assael, Citation2005). The context of use refers to ‘… the very concrete environment in which a technology is going to be used.’ (van de Wijngaert & Bouwman, Citation2009). The context of using different products determines exposure to risks and uncertainties that can influence consumer decisions (Ramtiyal et al., Citation2022). The consumption situation may moderate extrinsic cues’ impact on consumers’ risk assessment (Aqueveque, Citation2006). Consumers frequently experience situational effects when confronted with opportunities, time constraints, and tasks (Ramtiyal et al., Citation2022). For instance, purchasing and using a high-involvement product for personal instead of business use signifies a different level of complexity in the decision-making process. Purchasing a product for another individual is typically more intricate than doing so for one’s personal use. Given the importance of usage situations in brand choice, marketers must incorporate a situation variable (i.e. consumption situation) when developing marketing strategies (Assael, Citation2005).

Country image and brand image on purchase intentions

The country of origin affects consumers’ general perception of product quality and the characters of people from a particular country (Knight & Calantone, Citation2000). Schooler (Citation1965) introduced the term country of origin as a signal for evaluating products. Along with international business development, the country of origin has evolved from a single cue to multiple signals, including the country of design and assembly (d’Astous & Ahmed, Citation1999), country of manufacturing, and brand origin (Usunier, Citation2011). The different terms in the literature used to indicate the role of country of origin in product evaluation and consumer decision-making are country image, product-country image, country equity, made-in-country image, and origin country image (Kleppe et al., Citation2002). Despite a multitude of related terms, scholars can analyze the role of the country-of-origin effect at the country and product levels (Knight & Calantone, Citation2000; Parameswaran & Pisharodi, Citation1994). The current study utilizes a country image to describe the effect of country information on consumer evaluation and decisions.

Country image is essential for consumers, especially those with limited product knowledge because it can provide a shortcut in information search and product evaluation (Lee & Lee, Citation2009). The halo model explains that country image offers a halo effect for consumers with limited knowledge to develop certain beliefs or stereotypes about a product. In contrast, the summary construct model posits that the country image summarizes beliefs regarding product attributes based on consumer knowledge or experience (Cilingir & Basfirinci, Citation2014). Other theories explain the influence of a country image on consumer evaluation and decision-making. The cue theory identifies country image as an extrinsic signal influencing product evaluation by conveying product quality information without product information (Jin et al., Citation2020). The signaling theory views consumers subconsciously evaluating brands by using information called signals, such as the Kaizen culture, as a signal of the quality of Toyota products from Japan (Miyamoto et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, the attribution theory establishes that consumers’ cognitive and affective reactions to particular unexpected events or behaviors vary based on their perception of the underlying cause; for instance, Japanese brands are commonly associated with high prices as an attribute of quality (Miyamoto et al., Citation2023).

The current study analyzes country image conducted at the product level, specifically for automotive products categorized as high-involvement products. Country image affects attitudes, preferences, purchase intentions, and willingness to pay (Luis-Alberto et al., Citation2021). Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that country image affects consumer behavior (e.g. Diamantopoulos et al., Citation2011; Godey et al., Citation2012; Wang & Yang, Citation2008; Yu et al., Citation2013). However, previous studies have not explicitly examined the role of situational influences (i.e. consumption situations) in intervening in the impact of a country image on consumer decision-making. Therefore, the following hypothesis H1 is proposed:

H1: Country image affects purchase intentions based on consumption situations

Furthermore, several studies juxtapose country and brand image as predictors of product evaluation and behavioral intentions (Diamantopoulos et al., Citation2011; Yu et al., Citation2013). In line with a cue utilization theory (Olson, Citation1972), a brand is an essential product element, as it serves as an extrinsic product cue (Jin et al., Citation2020). Consumers utilize a brand to capture, select, organize, and interpret product evaluation and purchase decisions (Ahmed et al., Citation2004). Brand image is ‘…. The associations’ external target groups have in their minds about brands’ (Burmann et al., Citation2008), and companies seek to communicate brand image positively to improve brand positioning better than competing product brands (Gómez-Rico et al., Citation2023). Prior studies support these arguments by demonstrating that brand image affects product evaluation and purchase intentions (Bian & Moutinho, Citation2011; Diamantopoulos et al., Citation2011; Godey et al., Citation2012; Kim & Chao, Citation2019; Lien et al., Citation2015). As the signaling theory suggests, brand image infers product quality and value (Karanges et al., Citation2018). In line with the halo theory, consumers utilize brand image to infer products’ unknown attributes (Woo, Citation2019). The summary construct model also explains that brand image retrieves from memory all product attributes that customers may consult when assessing the product for purchase decisions (Park et al., Citation2011). Therefore, brand image becomes a pivotal factor in improving business performance, prompting marketers to invest significant efforts in preserving and strengthening their well-established brand image (Hamin et al., Citation2014). Based on the arguments, the following hypothesis H2 is proposed:

H2: Brand image affects purchase intentions based on the consumption situation

Warranty knowledge in decision-making

Consumer knowledge is essential for decision-making (Kang et al., Citation2013) because it represents memory and the information-search activities required before product evaluation and purchase decisions. Consumer knowledge can be classified into three categories: subjective knowledge (i.e. consumers’ subjective evaluation of their understanding of product or service-related matters), objective knowledge (i.e. consumers’ actual understanding of the factual and accurate product or service conditions), and prior experience (i.e. consumers’ factual experience when buying or consuming the products or services) (Brucks, Citation1985). Consumers who are highly involved in the products are more interested in product-associated information. The elaboration likelihood model explains that consumers activate central information processing (high elaboration) for high-involvement products and peripheral information processing (low elaboration) for low-involvement products (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). Consumer knowledge is the output of memory and the results of information-search activities.

Following the cue utilization theory (Olson, 1972), products consist of internal and external cues. Internal cues are realized in product features and specifications (Choi et al., Citation2018), while external cues are expressed as country of origin, brand, price, and warranty (Lee & Lee, Citation2009). Warranty is a critical extrinsic cue for consumers to evaluate a company’s commitment to meeting consumer expectations (Martín et al., Citation2011). Companies’ commitment becomes even more necessary when consumers purchase high-involvement products - i.e. those considered essential because they are associated with self-image, symbolic in nature, and expensive (Assael, Citation2005). For instance, a car is considered a high-involvement product (Dahiya, Citation2018). The absence or lack of a product warranty that guarantees product quality is a factor that prevents consumers from buying products (Clemes et al., Citation2014). Product warranties are increasingly relevant, especially for risk-averse consumers who are loss-sensitive like Asians; therefore, product warranty availability can attract Asian consumers (Han & Kim, Citation2017). A product warranty is a strategy for reducing risk (Mansour & Ali, Citation2009). Risk-reduction strategies increase certainty and reduce unexpected consequences of human actions (Lo et al., Citation2011). A product warranty reduces risk perception (Mahmoodi & Heydari, Citation2021), protects consumers from the negative consequences of product failure, and signals quality (H. Huang et al., Citation2021). In addition, product warranties provide consumers with greater assurance in dealing with uncertainty related to the performance of new products and serve as a signal of product quality (Murthy & Djamaludin, Citation2002).

It has been demonstrated that risk knowledge reduces risk perceptions (Zhu & Deng, Citation2020). Featherman et al. (Citation2021) establish that strong beliefs about product warranty will protect consumers regardless of whether they rely on research (i.e. objective knowledge) or intuition (i.e. subjective knowledge). In this sense, beliefs regarding product warranty are the function of product warranty knowledge, encompassing both actual knowledge (i.e. objective warranty knowledge) and perceived knowledge (i.e. subjective warranty knowledge). Product warranty knowledge as an external cue is particularly relevant for risk-averse consumers confronted with high-involvement purchasing decision-making situations. Previous studies have examined the role of consumer knowledge in decision-making but rarely discuss warranty-specific consumer knowledge. Awareness of product-warranty existence is critical, especially when consumer decision-making for high-involvement products has a higher potential risk than for low-involvement products. Moreover, the complexity of decision-making is compounded by the situational influences that consumers encounter, leading to greater risk levels.

Previous studies have investigated the relationship between objective and subjective knowledge. However, the findings have indicated that such a relationship is weak (Hadar et al., Citation2013), likely because consumers tend to be overconfident, which causes subjective knowledge to be more prevalent than objective knowledge (Pieniak et al., Citation2010). Hoque and Alam (Citation2020) posit that subjective knowledge significantly affects purchase intentions, whereas objective knowledge yields similar results. Consistent with Featherman et al. (Citation2021), this study specifically examines the role of objective and subjective consumer product knowledge, especially in strengthening the effect of country and brand image on behavioral intention. Considering that the current study is conducted among Asians (i.e. Indonesians), who are arguably more risk-averse, the present study formulates the following hypotheses:

H3a: Subjective warranty knowledge moderates the relationship between product-country image and purchase intentions for personal use

H3b: Subjective warranty knowledge moderates the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions for business use.

H4a: Objective warranty knowledge moderates the relationship between product-country image and purchase intentions for personal use.

H4b: Objective warranty knowledge moderates the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions for business use.

Research methods

Sampling and data collection

The current study is explanatory research to test the effects of the independent and moderating variables on the dependent variables in the proposed research model. The owners or managers of car rental providers in Central Java, Indonesia, were selected as the research respondents based on the non-probability sampling method of purposive sampling technique. Questionnaires were distributed to potential respondents individually and through car rental provider forums on social media (WhatsApp and Facebook), and the respondents filled out a form to confirm their consent to participate in the current study. Those who submitted their consent completed the questionnaire independently and submitted their responses through a Google form. Data collection was conducted from July to August 2020.

Measurement

The research instrument utilized questions about the respondents’ demographic profiles (gender and age) and business profiles (number of employees and car fleets). Furthermore, the research instrument comprised questions that measured the following concepts: country image, brand image, consumer knowledge (i.e. subjective and objective), and purchase intentions. The present study modified the measurement items used in previous studies. Consecutively, the current study used five question items to measure country image (Knight & Calantone, Citation2000), nine-question items for brand image (Driesener & Romaniuk, Citation2006), two question items to measure subjective warranty knowledge (Brucks, Citation1985), and four question items for purchase intentions (Huang et al., Citation2014; Jalilvand & Samiei, Citation2012)—see Appendix 1 for consulting a complete questionnaire. All the question items for the four variables were measured using a Likert scale.

In contrast, objective warranty knowledge was measured using a ratio scale. Participants responded to five questions to evaluate the degree to which they possessed factual knowledge of the Wuling automobile product warranties. The sum of correct answers determines the level of objective warranty knowledge. The current study transformed the warranty knowledge score measured by interval scale into a standardized value. It then calculated its mean value as a cut-off to establish two levels of warranty knowledge: high and low. This process uses multi-group analysis to test the moderating effects of subjective and objective warranty knowledge.

Data analysis

Before analyzing the data, the data screening stage was carried out by identifying and addressing issues such as missing data, unengaged responses, and data normality. A disengagement response occurs when the variation of respondents’ answers is low, as indicated by the standard deviation value of less than 0.5 for all responses (Steyn, Citation2017). Data normality was indicated when the skewness and kurtosis values for every variable question item fell from -1 to 1 (Ramos et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the validity and reliability tests used factor analysis with a minimum factor loading of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2010) and the Cronbach α test with a minimum score of 0.6, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2018). After the data were deemed valid and reliable, further analysis was performed using a structural equation modeling to obtain the proposed hypothesis testing results. A structural equation modeling was conducted using SmartPLS 4 with a copyright license for this study.

Findings

Data collection yielded a total of 386 respondents without missing data. In general, the data did not suggest unengaged responses, as indicated by the magnitude of the variation in the answers to all variable items in the research model (i.e. ≥ 0.5 standard deviations), except for two responses whose standard deviation values were within an acceptable range (approximately 0.5 standard deviations). Examining the skewness and kurtosis values for each variable question item reveals that the data are normally distributed, as both measures remain within the range of -1 to 1. Once the data screening process was complete, the subsequent phase involved assessing the validity and reliability of the data. presents the final results of the validity and reliability tests. All variable measurement items were valid and reliable, except for three items measuring brand image (BIW5, BIW8, and BIW9), which were invalid because the loading factors were below 0.5.

Table 1. Demographic and business profiles.

Respondent profiles

demonstrates respondents’ demographic and business profiles. The demographic profile revealed that most respondents were male (90.7%) and belonged to the age groups of > 20–30 years (59.1%) and > 30–40 years (27.5%). Further, most respondents were owner-managers (46.6%). Car providers with no more than five employees dominated the respondents (65.5%), followed by those with > 5–10 employees (19.9%). Meanwhile, most respondents had a maximum of five operational vehicles (56.5%), followed by those with car ownership > 5–10 units (23.8%).

Validity and reliability test

The subsequent phase involved the validity and reliability tests before further data analysis using structural equation modeling. The validity test was carried out using factor analysis because it is considered the most commonly used method for testing construct validity (H. Kang, Citation2013). The results of the first round of data processing with factor analysis showed a KMO value of 0.917, higher than the cut-off value of 0.5 (Yong & Pearce, Citation2013), indicating the adequacy of the sample used. Consistent with the KMO results, the Bartlett test of sphericity value of 8,793.374 (p < 0.001) demonstrated the adequacy of the correlation matrix, suggesting that it is feasible to proceed with the factor analysis. Except for BIW5, BIW8, and BIW9, which have factor loading values below 0.5, the rotation factor matrix reveals that the measurement items for each tested variable (country image, brand image, subjective knowledge, and purchase intentions) are on their corresponding factors and have factor loadings exceeding 0.5. Therefore, the second round of the factor analysis was repeated by excluding BIW5, BIW8, and BIW9. The second round of factor analysis generated a KMO of 0.906 and a Bartlett test of sphericity of 7,709.455 (p < 0.001). The rotated component matrix table indicates that all items measuring the same variable were on the same factor. Furthermore, the reliability test results showed all variables had a Cronbach α value greater than 0.6. Therefore, as displayed in , all measurement items were valid and reliable.

Table 2. Validity and reliability tests.

Subsequently, demonstrates further validity and reliability tests for all exogenous (i.e. country and brand image) and endogenous (i.e. purchase intentions) constructs. Following Hair et al. (Citation2022), the results suggest that all constructs satisfy the requirement for internal consistency reliability as indicated by composite reliability (CR), convergent validity as indicated by average variance extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity as evaluated by Fornell-Larcker’s criterion and heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT). Each construct exhibits composite reliability higher than the treshold level value of 0.6, average variance extracted (AVE) higher than 0.5, the square root of each construct’s AVE greater than its highest correlation with any other construct, and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) below 0.85.

Table 3. Internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity.

Hypothesis testing

The hypotheses were empirically tested based on valid and reliable datasets. The current study used structural equation modeling. demonstrates that country image significantly affects purchase intentions in two different consumption situations: personal use (p < 0.001) and business use (p < 0.001). The brand image also significantly influences purchase intentions for personal use (p < 0.001) and business use (p < 0.001). These results indicate that hypotheses H1 and H2 are empirically supported. However, the impacts of both image constructs on purchase intentions do not differ between the two types of consumption scenarios (p > 0.05).

Table 4. The effect of image constructs on purchase intentions (personal vs business).

The next test empirically analyzed the moderating effect of subjective warranty knowledge on the relationship between the independent variables (country image and brand image) and purchase intentions in personal and business use settings. indicates that subjective warranty knowledge in the personal use setting moderates the relationship between country image and purchase intentions (β difference = -0.351, p < 0.001) and also the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions (β difference = 0.189, p = 0.036)

Table 5. The moderation effect of subjective warranty knowledge.

Furthermore, presents information regarding the presence or absence of the moderating effect of subjective warranty knowledge on the relationship between two image constructs and purchase intentions in the business use setting. A structural equation modeling test reveals a significant moderation effect of subjective warranty knowledge on the relationship between country image and purchase intentions for business purposes (β difference = -0.286, p = 0.012). However, in the business setting, subjective warranty knowledge does not moderate the effect of brand image on purchase intentions (β difference = 0.081, p = 0.349). Therefore, the findings from support hypothesis H3a and partially support hypothesis H3b.

The findings based on a structural equation modeling analysis demonstrate the role of objective warranty knowledge in the relationship between image constructs (i.e. country image and brand image) and purchase intentions for personal and business use. indicates that objective warranty knowledge does not have a moderation effect on the relationship between country image and purchase intentions (β difference = 0.030, p = 0.763), also the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions (β difference = -0.099, p = 0.302), both for personal use. The same pattern applies to business use settings where objective warranty knowledge does not moderate the effect of country image on purchase intentions (β difference = -0.132, p = 0.194) and the impact of brand image on purchase intentions (β difference = 0.008, p = 0.917). The results from indicate that hypotheses H4a and H4b are not empirically supported.

Table 6. The moderation effect of objective warranty knowledge.

Discussions

The findings indicate that country and brand image positively affect purchase intentions in both personal and business situations. Nevertheless, the effects of country and brand image remain the same across consumption situations (i.e. personal and business use). The findings are consistent with the cue utilization theory, arguing that consumers activate external cues as information sources for product evaluation. In general, considering that both image constructs directly influence purchase intentions, it is likely that country image and brand image create a halo effect, assuming that the respondents were not familiar with the product (i.e. Chinese car brand).

However, when evaluating more established products, such as Japanese car brands, the respondents might regard country and brand image as summary effects. The findings also suggest that respondents considered country and brand images essential information sources irrespective of the consumption context. As car rental business owners with knowledge and experience in evaluating, purchasing, and utilizing automobiles, the respondents consider brand and country image influential factors in their car purchase decisions. However, the results indicate that the respondents tend to emphasize brand image more than country image as an information source. Regardless of the roles of country image and brand image (i.e. halo or summary effect), the respondents considered country image and brand image vital in purchasing decisions.

Subjective warranty knowledge significantly moderates the effect of country image on purchase intentions for personal and business use. Enhanced subjective knowledge arguably strengthens the impact of a country image on purchase intentions. Subjective warranty knowledge boosts consumers’ confidence, which enables them to anticipate potential risks, particularly when purchasing products from countries whose reputations have evolved from inferior to better image, such as Chinese products. Given the product’s characteristics (i.e. cars as high-involvement products) and the assumption that most Asian consumers are risk-averse, they are more likely to reduce unexpected product failure through product warranties. Following the elaboration likelihood model, respondents conducted an intensive information search about product offerings, including product warranties.

In contrast, subjective warranty knowledge moderates the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions only for personal use, not business use. Interestingly, subjective warranty knowledge weakens the effect of brand image on purchase intentions for personal use. This result might occur when respondents depend on external cues, such as product warranties, to compensate for perceived high risks associated with a newcomer brand. Subjective warranty knowledge is irrelevant in the relationship between brand image and purchase intentions for business use. Given the higher complexity of consumption situation for business use than personal use, respondents likely lack confidence in new brands due to limited references to obtain accurate information about the new brand’s success for business use through mainly word-of-mouth communication. Therefore, subjective warranty knowledge is insufficient to elevate the brand image effect on purchase intentions for business use, given that respondents might still ‘wait and see’ new car brands’ performance history. In contrast, Japanese car brands are more established and dominate the Indonesian car market (The Association of Indonesia Automotive Industry, Citation2024).

Subjective warranty knowledge has a more pronounced role than objective warranty knowledge in moderating the effect of country image on purchase intentions. Objective warranty knowledge does not moderate the relationship between the two external cues (i.e. country and brand image) on car purchase intentions for personal and business use. Consistent with Pieniak et al. (Citation2010), it is likely that the respondents are highly self-confident and thus rely more on subjective warranty knowledge than objective warranty knowledge, which causes subjective warranty knowledge to be more relevant for respondents than objective warranty knowledge. Respondents’ backgrounds as owners or managers of car rental providers arguably explain their greater confidence in their subjective knowledge than relying on objective warranty knowledge when evaluating and making decisions.

Conclusions

The findings partially lend support to all hypotheses proposed in the current study. For the hypothesized main effects of country and brand image on purchase intentions, the results indicate that country and brand images are essential external cues in consumers’ decision-making processes in personal and business use contexts. The respondents consistently utilize the effects of both image constructs on purchase intentions irrespective of the two consumption situations. The impact of brand image is greater than a country image, indicating that specific external cues such as brand image are more prominent than general external cues such as a country image on consumer decision-making.

Subjective warranty knowledge strengthens the effect of country image on purchase intentions for personal and business use. Given that respondents are mostly business consumers, they are highly confident due to greater subjective warranty knowledge to anticipate the potential risks associated with the ‘made-in’ products from ‘unfavorable country image.’ However, subjective knowledge only substantiates the effect of brand image on purchase intentions when respondents purchase a car for personal use instead of business use. Purchasing a car can be considered a high-involvement decision despite a continuum of purchase involvement following the consumption situations (i.e. personal vs business use). The nature of newcomer brands and high-involvement purchases, which increase uncertainty and complexity, are more likely to attenuate the effect of brand image on purchase intentions, particularly for business use.

Objective warranty knowledge significantly moderates the effect of country and brand image on purchase intentions for personal and business use. Subjective warranty knowledge outperforms objective warranty knowledge in strengthening or attenuating the impacts of country and brand image on purchase intentions. The results correspond with the respondent’s profile as business consumers, leading to greater confidence in their subjective product warranty knowledge. Respondents rely more on subjective than objective warranty knowledge when evaluating and making purchase decisions. Confidence bias creates an inconsistency/gap regarding the effects of warranty knowledge on purchase intentions. Subjective warranty knowledge does not necessarily reflect objective warranty knowledge regarding its weight and significance and vice versa.

Managerial and theoretical implications

Brand cars from a country of origin with an ‘unfavorable image’ encounter challenges in attracting consumers to purchase their products. Wuling may focus on boosting its product/brand image among image constructs because its effect on purchase intentions is greater than country image. Additionally, it is more difficult to intervene country image. The outcomes of brand image measurements indicate specific issues that Wuling should address. Specifically, Wuling must handle the stereotype that Chinese brands are less durable and frequently require maintenance through intensive marketing communications and services that might reduce risk perceptions, including by providing reliable after-sales services through the availability of extensive workshop services and spare parts. Besides, Wuling needs to continue its research and development (R&D) to improve certain aspects of its product, such as product quality and durability.

The role of subjective warranty knowledge is relevant in influencing product evaluation and purchase intentions. Wuling could communicate its product warranty policy to potential consumers through various channels to enhance their perception of product warranties. Additionally, Wuling must provide convenient access to information regarding warranty. For instance, each promotion staff incorporates product warranty information into the promotion materials delivered during direct marketing activities. Furthermore, the product website must display product warranty information to facilitate consumers’ access to the data more conveniently.

The current study presents empirical evidence that country and brand image consistently predict purchase intentions in two distinct consumption situations: personal and business use. As with risk knowledge, the status of product warranty knowledge, particularly subjective warranty knowledge, is better than objective knowledge as risk knowledge. The respondents exhibit a certain degree of confidence bias due to their profiles, which are highly involved with the product (i.e. car-rental service providers)-such bias results in a gap between subjective knowledge and objective knowledge.

Research limitations

The primary contribution of the current study is to investigate the effects of consumers’ product warranty knowledge on the evaluation and purchase decisions of high-involvement products (i.e. cars) among Asian respondents (i.e. Indonesians) who are arguably more risk-averse. Nevertheless, consumer knowledge may not only be related to product warranty issues. Consumer knowledge is multidimensional, and each dimension potentially contributes to evaluation and purchase decision-making. The current study has not investigated the relative contribution of warranty knowledge across other potential risk-associated cues, such as price and product information.

Future research

Future research can further investigate the role of product warranty in strengthening or attenuating the relationship between image constructs and purchase intentions for new and well-established brands. The current study involves the owners or managers of car rental providers as business consumers to express their responses in two different consumption situations (personal vs. business use). Subsequent hypothesis testing may involve individual consumers in two other car purchase situations (purchase vs rent) or comparing two unrelated samples: individual and business consumers. Additionally, subjective knowledge can be expressed in multiple dimensions, such as product features, price, and warranty. Future research needs to investigate the contribution of warranty knowledge across other internal and external cues in consumer decision-making.

Authors’ contributions

Albert Kriestian Novi Adhi Nugraha: Research idea, creation of final research model, literature review and methodology development, data analysis, writing the initial and final draft, English translation, and proofreading for the final manuscript. Cara Edo Krista: Created initial research model, researched instrument design, and collected data. Andrian Dolfriandra Huruta: data analysis and visualization.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Albert Kriestian Novi Adhi Nugraha

Albert Kriestian Novi Adhi Nugraha is an Associate Professor at Satya Wacana Christian University in Indonesia. His research interests include consumer behaviour, digital marketing, and green marketing. Some of his work has been published in internationally recognized journals. He received his Ph.D from Macquarie University in Australia.

Cara Edo Krista

Cara Edo Krista is a graduate of the undergraduate program in Management at the Faculty of Economics and Business at Satya Wacana Christian University in Indonesia. His research interests are in marketing and consumer behaviour.

Andrian Dolfriandra Huruta

Andrian Dolfriandra Huruta is is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business, Satya Wacana Christian University, Indonesia. His primary research interests are macroeconomics, econometrics, and international trade. He received his PhD from Chung Yuan Christian University in Taiwan.

References

- Ahmed, Z. U., Johnson, J. P., Yang, X., Fatt, C. K., Teng, H. S., & Boon, L. C. (2004). Does country of origin matter for low-involvement products? International Marketing Review, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330410522925

- Allcot, D. (2024). 7 Most reliable Japanese cars on the Market. Nasdaq. https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/7-most-reliable-japanese-cars-on-the-market

- Aqueveque, C. (2006). Extrinsic cues and perceived risk: The influence of consumption situation. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(5), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760610681646

- Arndt, J. (1986). Paradigms in consumer research: A review of perspectives and approaches. European Journal of Marketing, 20(8), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004660

- Assael, H. (2005). Consumer Behavior: A Strategic Approach. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Bartikowski, B., Fastoso, F., & Gierl, H. (2019). Luxury cars made-in-China: Consequences for brand positioning. Journal of Business Research, 102, 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.072

- Bian, X., & Moutinho, L. (2011). The role of brand image, product involvement, and knowledge in explaining consumer purchase behaviour of counterfeits: Direct and indirect effects. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111095658

- Bray, J. P. (2008). Consumer behaviour theory: Approaches and models.

- Brucks, M. (1985). The effects of product class knowledge on information search behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(1), 1–16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489377 https://doi.org/10.1086/209031

- Burmann, C., Schaefer, K., & Maloney, P. (2008). Industry image: Its impact on the brand image of potential employees. Journal of Brand Management, 15(3), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550112

- Chestnut, R. W., & Jacoby, J. (1977). Consumer information processing: Emerging theory and findings. Graduate School of Business, Columbia University.

- Choi, H. S., Ko, M. S., Medlin, D., & Chen, C. (2018). The effect of intrinsic and extrinsic quality cues of digital video games on sales: An empirical investigation. Decision Support Systems, 106, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2017.12.005

- Cilingir, Z., & Basfirinci, C. (2014). The impact of consumer ethnocentrism, product involvement, and product knowledge on country of origin effects: An empirical analysis on Turkish consumers’ product evaluation. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 26(4), 284–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2014.916189

- Clemes, M. D., Gan, C., & Zhang, J. (2014). An empirical analysis of online shopping adoption in Beijing, China. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(3), 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.08.003

- d’Astous, A., & Ahmed, S. A. (1999). The importance of country images in the formation of consumer product perceptions. International Marketing Review, 16(2), 108–126. http://simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=2204721&site=ehost-live https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339910267772

- Dahiya, R. (2018). A research paper on digital marketing communication and consumer buying decision process: An empirical study in the Indian passenger car market. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(2), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1365991

- Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B., & Palihawadana, D. (2011). The relationship between country‐of‐origin image and brand image as drivers of purchase intentions: A test of alternative perspectives. International Marketing Review, 28(5), 508–524. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331111167624

- Dominici, A., Boncinelli, F., Gerini, F., & Marone, E. (2021). Determinants of online food purchasing: The impact of socio-demographic and situational factors. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102473

- Driesener, C., & Romaniuk, J. (2006). Comparing methods of brand image measurement. International Journal of Market Research, 48(6), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530604800605

- Featherman, M., Jia, S. J., Califf, C. B., & Hajli, N. (2021). The impact of new technologies on consumers beliefs: Reducing the perceived risks of electric vehicle adoption. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 169, 120847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120847

- Filiatrault, P., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1988). The impact of situational factors on the evaluation of hospitality services. Journal of Travel Research, 26(4), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758802600406

- Godey, B., Pederzoli, D., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., Chan, P., Oh, H., Singh, R., Skorobogatykh, I. I., Tsuchiya, J., & Weitz, B. (2012). Brand and country-of-origin effect on consumers’ decision to purchase luxury products. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1461–1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.012

- Gómez-Rico, M., Molina-Collado, A., Santos-Vijande, M. L., Molina-Collado, M. V., & Imhoff, B. (2023). The role of novel instruments of brand communication and brand image in building consumers’ brand preference and intention to visit wineries. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 42(15), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02656-w

- Hadar, L., Sood, S., & Fox, C. R. (2013). Subjective knowledge in consumer financial decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0518

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hulth, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): Third Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2018). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall Upper.

- Hamin, H., Baumann, C., & L. Tung, R. (2014). Attenuating double jeopardy of negative country of origin effects and latecomer brand: An application study of ethnocentrism in emerging markets. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 26(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-07-2013-0090

- Han, C. M. (2020). Assessing the predictive validity of perceived globalness and country of origin of foreign brands in quality judgments among consumers in emerging markets. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 19(5), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1829

- Han, M. C., & Kim, Y. (2017). Why consumers hesitate to shop online: Perceived risk and product involvement on Taobao. com. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2016.1251530

- Hoque, M. Z., & Alam, M. N. (2020). Consumers’ knowledge discrepancy and confusion in intent to purchase farmed fish. British Food Journal, 122(11), 3567–3583. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2019-0021

- Hsu, C.-L., Chang, C.-Y., & Yansritakul, C. (2017). Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.006

- Huang, H., Liu, F., & Zhang, P. (2021). To outsource or not to outsource? Warranty service provision strategies considering competition, costs and reliability. International Journal of Production Economics, 242, 108298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108298

- Huang, Y.-C., Yang, M., & Wang, Y.-C. (2014). Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 32(3), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-10-2012-0105

- Jalilvand, M. R., & Samiei, N. (2012). The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention: An empirical study in the automobile industry in Iran. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 30(4), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501211231946

- Jin, B. E., Kim, N. L., Yang, H., & Jung, M. (2020). Effect of country image and materialism on the quality evaluation of Korean products: Empirical findings from four countries with varying economic development status. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(2), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-11-2018-0456

- Kang, H. (2013). A guide on the use of factor analysis in the assessment of construct validity. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 43(5), 587–594. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2013.43.5.587

- Kang, J., Liu, C., & Kim, S. (2013). Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12013

- Karanges, E., Johnston, K. A., Lings, I., & Beatson, A. T. (2018). Brand signalling: An antecedent of employee brand understanding. Journal of Brand Management, 25(3), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0100-x

- Kiki, S. (2022). April 4). Industri Otomotif Indonesia Diprediksi Kembali Bangkit Tahun Ini. Kompas.Com. https://money.kompas.com/read/2022/04/04/132922326/industri-otomotif-indonesia-diprediksi-kembali-bangkit-tahun-ini?page=all

- Kim, R. B., & Chao, Y. (2019). Effects of brand experience, brand image and brand trust on brand building process: The case of Chinese millennial generation consumers. Journal of International Studies, 12(3), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2019/12-3/1

- Kleppe, I. A., Iversen, N. M., & Stensaker, I. G. (2002). Country images in marketing strategies: Conceptual issues and an empirical Asian illustration. Journal of Brand Management, 10(1), 61–74. http://simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=7346290&site=ehost-live https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540102

- Knight, G. A., & Calantone, R. J. (2000). A flexible model of consumer country-of-origin perceptions: A cross-cultural investigation. International Marketing Review, 17(2), 127–145. http://simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=3526534&site=ehost-live https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330010322615

- Kotler, P., & Levy, S. J. (1969). Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 33(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296903300103

- Kusumastuti, H. (2022 The Effectiveness of Implementing Tax Incentives for Sales Tax on Luxury Goods in the Manufacturing Industry during the COVID-19 Pandemic (a Case Study in Indonesia) [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings (Vol. 83, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022083067

- Lee, J. K., & Lee, W.-N. (2009). Country-of-origin effects on consumer product evaluation and purchase intention: The role of objective versus subjective knowledge. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 21(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530802153722

- Liang, T.-P., & Yeh, Y.-H. (2009). Situational effects on the usage intention of mobile games. Designing EBusiness Systems. Markets, Services, and Networks: 7th Workshop on E-Business, WEB 2008, Paris, France, December 13, 2008, Revised Selected Papers 7, 51–59.

- Lien, C.-H., Wen, M.-J., Huang, L.-C., & Wu, K.-L. (2015). Online hotel booking: The effects of brand image, price, trust and value on purchase intentions. Asia Pacific Management Review, 20(4), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2015.03.005

- Lo, A. S., Cheung, C., & Law, R. (2011). Hong Kong residents’ adoption of risk reduction strategies in leisure travel. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(3), 240–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.562851

- Luis-Alberto, C.-A., Angelika, D., & Juan, S.-F. (2021). Looking at the brain: Neural effects of ‘made in’ labeling on product value and choice. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102452

- Mahmoodi, H., & Heydari, J. (2021). Consumers’ preferences in purchasing recycled/refurbished products: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Services and Operations Management, 38(4), 594–609. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSOM.2021.114249

- Mansour, S., & Ali, Y.-N. (2009). A survey of the effect of consumers’ Perceived risk on purchase intention in e-shopping. Business Intelligence Journal, 2.

- Martín, S. S., Camarero, C., & José, R. S. (2011). Does involvement matter in online shopping satisfaction and trust? Psychology & Marketing, 28(2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20384

- Mitchell, V. W. (1998). A role for consumer risk perceptions in grocery retailing. British Food Journal, 100(4), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709810207856

- Miyamoto, J., Shimizu, A., Hayashi, J., & Cheah, I. (2023). Revisiting ‘Cool Japan’ in country-of-origin research: A commentary and future research directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(9), 2251–2265. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-07-2022-0596

- Murthy, D. N. P., & Djamaludin, I. (2002). New product warranty: A literature review. International Journal of Production Economics, 79(3), 231–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(02)00153-6

- Negara, S. D., & Hidayat, A. S, Senior Fellow in the Regional Economic Studies Programme at the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. (2021). Indonesia’s automotive industry: Recent trend and challenges. Southeast Asian Economies, 38(2), 166–186. https://doi.org/10.1355/ae38-2b

- Olson, J. C. (1972). Cue utilization in the quality perception process: A cognitive model Andan empirical test. Purdue University.

- On, M. (2015). What Will It Take For Chinese Brands To Be Accepted By Global Consumers? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/onmarketing/2015/03/20/what-will-it-take-for-chinese-brands-to-be-accepted-by-global-consumers/?sh=46346c2f3970

- Pachauri, M. (2001). Consumer behaviour: A literature review. The Marketing Review, 2(3), 319–355. https://doi.org/10.1362/1469347012569896

- Parameswaran, R., & Pisharodi, R. M. (1994). Facets of country of origin image: An empirical assessment. Journal of Advertising, 23(1), 43–56. http://simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9406223876&site=ehost-live https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1994.10673430

- Park, J. Y., Park, K., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2011). Impact of retailer image on private brand attitude: Halo effect and summary construct. Australian Journal of Psychology, 63(3), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9536.2011.00015.x

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Springer.

- Pieniak, Z., Aertsens, J., & Verbeke, W. (2010). Subjective and objective knowledge as determinants of organic vegetables consumption. Food Quality and Preference, 21(6), 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2010.03.004

- Ramos, C., Costa, P. A., Rudnicki, T., Marôco, A. L., Leal, I., Guimarães, R., Fougo, J. L., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2018). The effectiveness of a group intervention to facilitate posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 27(1), 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4501

- Ramtiyal, B., Verma, D., & Rathore, A. S. (2022). Role of risk perception and situational factors in mobile payment adoption among small vendors in unorganised retail. Electronic Commerce Research, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09657-2

- Schmerler, K. (2019). Country-of-origin preferences and networks in medical tourism: Beyond the reach of providers? Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism: 7th ICSIMAT, Athenian Riviera, Greece, 1269–1277.

- Schooler, R. D. (1965). Product bias in the Central American common market. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 2, 2(4), 394–397. http://simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=5004698&site=ehost-live https://doi.org/10.1177/002224376500200407

- Shao, B., Cheng, Z., Wan, L., & Yue, J. (2021). The impact of cross border E-tailer’s return policy on consumer’s purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102367

- Shepard, W. (2016). How ‘made in China’ became cool. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2016/05/22/how-made-in-china-became-cool/#1eae713f77a4

- Steyn, R. (2017). How many items are too many? An analysis of respondent disengagement when completing questionnaires. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(2), 1–11.

- The Association of Indonesia Automotive Industry. (2024). Indonesian Automobile Industry Data. https://www.gaikindo.or.id/indonesian-automobile-industry-data/#

- Tolok, A. D. (2019). Garansi panjang bikin harga jual mobil China terjaga. Bisnis.Com. https://otomotif.bisnis.com/read/20190806/275/1133063/garansi-panjang-bikin-harga-jual-mobil-china-terjaga

- Tybout, A. M., Calder, B. J., & Sternthal, B. (1981). Using information processing theory to design marketing strategies. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800107

- Usunier, J. (2011). The shift from manufacturing to brand origin: Suggestions for improving COO relevance. International Marketing Review, 28(5), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331111167606

- van de Wijngaert, L., & Bouwman, H. (2009). Would you share? Predicting the potential use of a new technology. Telematics and Informatics, 26(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2008.01.002

- Wahyu, D. (2018). Ternyata, masih banyak yang ragu kualitas mobil Cina. Liputan6.Com. https://www.liputan6.com/otomotif/read/3419542/ternyata-masih-banyak-yang-ragu-kualitas-mobil-cina

- Wang, X., & Yang, Z. (2008). Does country-of-origin matter in the relationship between brand personality and purchase—intention in emerging economies? International Marketing Review, 25(4), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330810887495

- Woo, H. (2019). The expanded halo model of brand image, country image and product image in the context of three Asian countries. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 31(4), 773–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-05-2018-0173

- Wuling, I. (2023). Celebrating Six Years in Indonesia, Wuling Continues to Present Endless Innovations. https://wuling.id/en/blog/press-release/celebrating-six-years-in-indonesia-wuling-continues-to-present-endless-innovations

- Yong, A. G., & Pearce, S. (2013). A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 9(2), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079

- Yu, C.-C., Lin, P.-J., & Chen, C.-S. (2013). How brand image, country of origin, and self-congruity influence internet users’ purchase intention. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(4), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.4.599

- Zhu, H., & Deng, F. (2020). How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103514

Appendix 1.

Questionnaires

Country Image*

How would you rate Chinese products compared to Japanese products in the following areas:

PIC1 - Products made with meticulous workmanship.

PIC2 - Products are distributed worldwide.

PIC3 - Products need minimum repair.

PIC4 - Products are long-lasting or durable.

PIC5 - Reliable after-sales service.

Brand Image **

To what extent do you agree that Wuling is an automotive product brand that is:

BIW1 – Advanced.

BIW2 – Broadly distributed.

BIW3 – Possessing good value.

BIW4 – Safe.

BIW5 – Trustworthy.

BIW6 – Modern.

BIW7 – Interesting.

BIW8 – Prestigious.

BIW9 – Responsive.

Purchase intentions**

To what extent do you agree with the following statement:

PIN1 - I will purchase the brand (Wuling) for …. (personal or business use).

PIN2 - I am willing to recommend others to purchase the brand (Wuling) for …. (personal or business use).

PIN3 - I will make the brand (Wuling) my priority when purchasing a car for … (personal or business use).

PIN4 - I am willing to wait for a car indent if the brand (Wuling) that I want for … (personal or business use) is not yet available.

Subjective warranty knowledge***

SKG1 - To what extent is your knowledge of the terms and conditions governing Wuling car warranty?

SKG2 - How would you rate your knowledge of Wuling car warranty terms and conditions compared to your peers?

Objective warranty knowledge****

1. Wuling Motors provides a general warranty for five years or 100,000 km.

2. Wuling Motors provides engine and transmission main components with a warranty of three years or 100,000 km.

3. Wuling Motors provides a warranty on spare parts and installation for one year or 20,000 km.

4. Wuling Motors provides a warranty of free periodic service fees for up to 4 years or 50,000 km.

5. The warranty remains in effect when the vehicle ownership is transferred.

* 5-point scale (inferior/superior)

** 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree/strongly agree)

*** 5-point scale (very low/very high)

**** Binomial scale (Yes/No).