Abstract

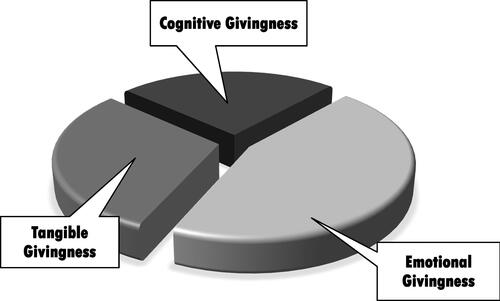

This study investigates how culture influences job satisfaction among academics. Through a two-stage interview process involving 294 Arab academics, 20 satisfaction categories were identified, with ‘institutional givingness’ emerging as the most significant. Institutional givingness, rooted in Arab culture, reflects the key to satisfaction. It manifests in three forms: tangible, emotional, and cognitive. Three perspectives on satisfaction were highlighted: the role of givingness in organizational dynamics, technology’s influence on satisfaction, and emotional obstacles to givingness. These insights underscore the interaction of cultural, technological, and hierarchical elements in Arab academia. The study contributes in three ways: advocating a ‘power and give’ approach for boosting job satisfaction in Arab contexts; revealing cultural differences in satisfaction determinants, with Arabs placing significant emphasis on givingness; and underscoring the importance of addressing hierarchical, technological, and emotional aspects of givingness. These findings are crucial for policymakers and educational leaders, offering a strategic framework to create a more satisfying academic environment aligned with Arab cultural values and expectations, thereby fostering a more engaged and committed academic workforce.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Understanding job satisfaction within various cultural contexts has become an area of interest in organizational studies (Al Smadi et al., Citation2023; Andreassi et al., Citation2012; Eskildsen et al., Citation2010; Gu et al., Citation2022; Hauff et al., Citation2015). The interest has extended to job satisfaction in academic settings (Chipunza & Malo, Citation2017; Eyupoglu et al., Citation2017; Kuwaiti et al., Citation2020). The interest is rooted in the recognition that satisfaction in academic environments is not solely the product of institutional policies or practices but is deeply interwoven with the cultural fabric within which these institutions operate. That research on job satisfaction among academics is dominated by studies far removed from the Arab cultural context is problematic given Parsons (Citation1990) ‘cultural – -institutional’ conceptualization of organizations as parts of a more extensive social system whose values they are subject to and must observe in order to gain legitimacy. According to contemporary Institutional Theory, formal and informal institutions shape and influence organizational cultures and practices (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977; Ali & Weir, Citation2020). In that regard, institutions are country-specific (Hussein, 2007), implying that how they affect or influence organizational practices, including those affecting employee job satisfaction, varies. Notwithstanding many studies on determinants of job satisfaction, particularly in the West, few studies focus on the Arab world. Further, Arab world-based studies have primarily been quantitative and, therefore, inadequately nuanced to capture Arab context-specific aspects of academics’ job satisfaction (for example, Asfahani, Citation2024; Bataineh, Citation2014; Asan & Wirba, Citation2017; Jawabri, Citation2017). This article contributes towards reducing this identified gap in knowledge by using a qualitative approach to investigate how the Arab culture affects members’ satisfaction in academia by answering the question: What is the major determinant of Arabs’ satisfaction in academia?

1.1. Arab culture

Culture is constituted by a community’s collective social values, principles, and attitudes (Hofstede, Citation1980). It includes attitudes, beliefs, behavioural norms, and basic assumptions and values shared by a group that influence the group members’ behaviours and their interpretation of ‘meanings’ of others’ actions (Spencer-Oatey, Citation2000). Hofstede (Citation1980) differentiated national cultures based on the dimensions: power distance, masculinity versus femininity, individualism versus collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, short-term versus long-term orientation, and indulgence versus restraint. Arab culture was characterised as high on power distance, uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, and moderate on masculinity/femininity (Hofstede, Citation2011). While Hofstede’s (Citation1980) seminal work has provided a framework for understanding how cultural dimensions influence organizational behaviour, including in academic settings, it has also faced criticism. With specific reference to Saudi Arabia, Hofstede has been criticised for generalising the culture of Middle East countries based on data collected from IBM employees based in a single country. In that context, while mindful of Hofstede’s theory, this study sought an explanation of the nexus of Arab culture as experienced in Saudi Arabia and job satisfaction among academics that was grounded in the experiences of academics in Saudi higher education institutions. Islam is an integral component of Arab culture and is the main element that distinguishes the culture from other cultures. Similarly, religion is embedded in Saudi Arabia’s culture. Hofstede (Citation2011) characterised Arab culture as high on power distance, uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, and moderate on masculinity/femininity (Hofstede, Citation2011). In a high power distance culture, those in authority exert power and demand unquestioned submission from those with less power. Uncertainty avoidance reflects the tolerance of uncertainty and ambiguity in the environment, as reflected by the extent to which a culture does not welcome change (Hofstede, Citation2011). Collectivism refers to the extent to which people pursue group interests ahead of individual interests. Masculinity/femininity refers to the extent to which a society accepts the conservative male work role model of power, achievement, and control.

Dominant traits of Arab culture include the perception that age confers wisdom (Wilson, Citation1996) and a strong desire to increase one’s influence (Dwairy et al., Citation2006), arising from the high power distance; blood-based solidarity among group members which makes them willing to fight for one another (Shihade, Citation2020), and interfering in others’ affairs, and giving advice (Buda & Elsayed-Elkhouly, Citation1998), strong family and tribal bonds (Al-Ghanim, Citation2012), all arising from the society’s high collectivism as group interests override individual ones.

Institutional Theory posits that organisational cultures and practices are influenced by formal and informal institutions shaped by a country’s culture (Iannotta et al., 2016; Ali & Weir, Citation2020). This approach is based on the notion that human beings are historically embedded in their culture and society and cannot be understood separate from their socio-cultural environment (Hussien, Citation2007). Also, linking organisation cultures to their context, Janićijević (Citation2011) portrays such culture as a combination of assumptions based on shared values, norms, beliefs, and attitudes that a group develops and adopts as it responds to its environment. Institutions are country specific as they are shaped by a country’s culture (Ali & Weir, Citation2020). Further, institutional support can be tangible and intangible, highlighting the possible multi-dimensional effect on academic satisfaction and the factors contributing to it. Given that Islam influences Arab culture, the same influence can extend to conceptualising what institutional factors influence job satisfaction in academic settings.

Studies have confirmed possible links between national culture and that which prevails in organisations, and thus affecting employee behaviour and sense of job satisfaction. Schein’s insights (2010) into organizational culture and leadership are particularly relevant, shedding light on how institutional values and practices can significantly impact employee engagement and satisfaction. In academic settings, where the confluence of diverse cultural values and institutional norms is pronounced, understanding the nuances of this relationship becomes even more critical. Literature has focused on the role of institutional support and environment in shaping academic satisfaction.

Given that organisations are embedded in their cultural environments to an extent that their cultures and practices are, to some extent, a reflection of their external environment, this article examines the influence of Arab culture as practiced in Saudi Arabia on the work environment in academic institutions and the implications for the job satisfaction of academics. While acknowledging the universal nature of certain human traits, a concerted effort is made to delineate characteristics that are distinctly Arab. This involves critically examining the traits identified by Abdulrahman (Citation1981) within the modern Arab institutional context, emphasizing cultural peculiarities like collective decision-making, the role of family and social connections, and specific communication styles. This distinction is vital to understand the unique cultural dynamics influencing Arab academic environments, moving beyond general human behaviours to uncover culturally specific nuances.

Ahmad et al. (Citation2021) investigated national culture, leadership styles, and job satisfaction in the United Arab Emirates. Their findings showed that national culture mediated the relationship between leadership style and job satisfaction among academic staff in a public university.

1.2. Job satisfaction among academics

Recent reports, including ‘The State of Higher Education 2022 Report’ by Gallup (Gallup, Citation2022), highlight the significant challenges faced by faculty and staff in higher education, such as increased workloads and burnout, contributing to a rise in dissatisfaction within the academic sector. Additionally, the ‘2023 Higher Education Trend Watch’ by EDUCAUSE (EDUCAUSE, Citation2023) underscores the continued resignation and migration of leaders and staff from higher education institutions, further evidencing this dissatisfaction.

Job satisfaction has been variously defined as feeling, belief, attitude, or value (Gan & Voon, Citation2021); described job satisfaction as ‘a combination of psychological, physiological and environmental circumstances that cause a person to say ‘I am satisfied with my job truthfully’ (Gan & Voon, Citation2021, p. 6); the favourable or unfavourable feelings an employee has towards their work (Newstrom & Davis, Citation2002); a happy emotion brought about by perceiving that the job fulfils an individual’s values (Locke, 1969 cited in Judge et al., Citation2008); and as emotions retained by employees during their work performance (Lee et al., Citation2022). It consists of employee characteristics, attitudes, and the work environment. (Gan & Voon, Citation2021).

In this article, job satisfaction is defined as a happy emotion toward the overall work environment brought about by perceiving that the job fulfils an individual’s values (Locke, 1969, cited in Judge et al., Citation2008). Included in the work environment are perceptions of the employer’s givingness or generosity with regard to meeting employees’ needs.Maslow and Lewis’s (1987) hierarchy of needs and Hertzberg’s (2015) two-factor theory are arguably the most popular job satisfaction theories. According to Maslow’s theory, individual needs fall into five progressive categories (physiological, safety, belonging, esteem and self-actualisation), and the fulfilment of lower-level needs precedes that of higher-level needs, meaning higher level needs cannot serve as a motivator if lower-level needs are unmet. Hertzberg introduced the concepts ‘Motivators’ and ‘Hygiene’ factors and posited that motivators (recognition, responsibility, advancement, and growth) are intrinsic and when present, lead to employee job satisfaction. Hygiene factors are extrinsic and, when not present, lead to job dissatisfaction. Maslow’s lower-level needs and Hertzberg’s hygiene factors focus on the employer’s givingness or generosity as they include physiological needs. Based on Hertzberg’s two-factor theory, studies have come up with various determinants of job satisfaction which constitute its dimensions (Lee et al., Citation2022; Orgambídez-Ramos et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2020). Spector’s (Citation1997) job satisfaction survey covered nine dimensions for determining job satisfaction: pay, promotion, supervision, fringe benefits, contingent rewards, operating conditions, co-workers, nature of work, and communication.

Job satisfaction factors are context sensitive. Miah and Hasan (Citation2022) investigated factors responsible for increasing job satisfaction of academics working for private universities in Bangladesh and found that extrinsic and intrinsic factors caused dissatisfaction. In the same environment, compensation packages, job security, and working conditions contribute significantly to academic job satisfaction (Masum et al., Citation2015). Similarly, Singh and Bhattacharjee (Citation2020), in an India-based study, found both extrinsic and intrinsic factors to be positively and significantly associated with job satisfaction, suggesting that in some contexts, the absence of satisfaction due to unaddressed intrinsic factors can result in dissatisfaction and that adequately addressing extrinsic factors can lead to satisfaction. A Romania-based study identified research recognition and value, efficient management, and work incentives as significantly contributing to academic staff job satisfaction (Udrea & Semenescu, Citation2023). Among lecturers in Thailand, reduced stress and work–family conflict influenced work satisfaction (Kim et al., Citation2023). In Oman, Hinai and Bajracharya (2914) identified workload, perception about colleagues, job status, support from management, compensation, and development as strongly associated with job satisfaction among academics. In Saudi Arabia, Al-Rubaish et al. (Citation2009) associated promotion, appreciation, remuneration, availability of alternatives, and freedom of choice with job satisfaction, while (Kuwaiti et al., Citation2020) identified salary as the most significant indicator of overall job satisfaction.

Studies have associated organisational culture with employee job satisfaction (Oppong et al., Citation2017; Serinkan & Kiziloglu, Citation2021; Tran, Citation2021). Organisational culture has been associated with national culture, implying a possible link between aspects of national culture and job satisfaction. The university system is embedded in a specific culture. It expresses a given culture, consistent with the view that professionals’ thinking and social relationships are grounded in the culture and society in which they find themselves (Mollo, Citation2023).

1.3. Study purpose

This study seeks to contribute to this ongoing discourse by specifically examining academic satisfaction within the context of Arab cultural values. By exploring the intersection of cultural dynamics, institutional support, and job satisfaction, this research aims to understand better what drives satisfaction in Arab academic settings. Such an understanding is critical given that its absence or the existence of job dissatisfaction has been associated with adverse outcomes such as health problems (Han et al., Citation2020; Kinman, Citation2014) and counterproductive work behaviour (Yean et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, this article explores the key factors influencing job satisfaction levels among Arab academics. Specific research objectives were to use the lived experiences of academics in Saudi Arabia to:

Verify the influence of Arab culture on the institutional practices of academic institutions in Saudi Arabia.

Analyse the characteristics of the institutional practices relating to job satisfaction.

Explore the influence of the embeddedness of Arab culture in institutional practices on the job satisfaction of academics.

2. Methodology

Job satisfaction has been investigated quantitatively, focusing on measuring satisfaction levels using specific dimensions of job satisfaction or the relationship among the dimensions (Asan & Wirba, Citation2017; Jawabri, Citation2017). The perspective does not lend itself to exploring detailed aspects of the nexus of national cultural context, organisational beliefs and practices that constitute its culture, and job satisfaction among academics. This study employs a grounded theory qualitative approach to explore the major determinant of Arabs’ satisfaction in academia by investigating the influence of Arab cultural values. We aimed to understand how culturally constructed values in the Arab context regulate and are regulated by psychological aspects related to academic satisfaction.

2.1. Grounded theory approach

For this study, we intentionally began work on the research directly rather than starting with a detailed literature review on the area of study. The initial literature review was limited and focused on deriving sensitising concepts to be used as points of departure in the analysis of collected data, consistent with, for example, Charmaz (Citation2014) and Thornberg (Citation2012). A more detailed literature review was performed post-hoc after the fieldwork was completed. As researchers, we thought that a proper understanding of cultural values would necessitate our limiting presuppositions that could exert influence over our interpretations. We preferred to conduct the fieldwork without being overly swayed or guided by pre-existing studies, notions, and concepts, instead willingly letting the data lead us (Yeo & Dopson, Citation2018). We embraced open-minded and unprejudiced approaches driven by limited literature, allowing the field data to manifest itself and be the primary encounter with relevant knowledge. Specifically, we utilized the constructivist school of grounded theory founded by Charmaz (Citation2014). This approach allows theories to emerge directly from the qualitative data through systematic yet flexible data collection and analysis guidelines. Constructivism acknowledges the subjectivity in meaning-making, positioning the researchers as co-constructors of knowledge with participants. We chose grounded theory for several reasons. First, it facilitates an in-depth exploration of cultural phenomena, enabling us to capture the nuances and complexity of Arab academic satisfaction. Second, the flexibility of grounded theory allows unconstrained discovery without preconceived hypotheses, which was critical in examining how modern factors like social media impact cultural notions of identity and satisfaction. Finally, the systematic data collection and analysis provides analytic power to this interpretive approach.

Through iterative interviewing and constant comparison, codes and categories emerged from the data, revealing conceptual relationships between Arab cultural values and satisfaction, integrating participants’ voices to build a contextual understanding grounded in their lived experiences. Our approach aligns with seminal cultural psychology works like Cole (Citation1996) that emphasize meaning-making in context.

2.2. Participant and data collection

We employed a ‘chain-referral approach’ for participant selection during both phases of our study. This approach, often called snowball sampling, involves existing participants recommending potential candidates. It is particularly effective in studies where participants are part of a specific cultural or professional group, as it allows researchers to access a population that might be difficult to reach through conventional sampling methods (Biernacki & Waldorf, Citation1981). This method was strategically used in our study to select individuals who met specific criteria relevant to our research on Arab academic satisfaction. The process continued until we achieved a minimum representation of one individual per criterion, ensuring a diverse and comprehensive sample. This approach was vital to capture various perspectives within the Arab academic community.

To maintain the integrity of the study, we ensured that the representation for each criterion was roughly equal to others in the same category. Interviews, averaging about ten minutes each, were conducted digitally via Zoom, primarily for cost-effectiveness and adherence to safety protocols during the COVID-19 outbreak. The choice of digital interviews also allowed for a broader geographical reach, enhancing the diversity of our sample.

The following criteria guided the participant selection:

Gender: To ensure a balanced representation of perspectives.

Language: Participants varied in their primary language of communication within the academic context.

Country: Individuals from different Arab countries were included to capture regional diversity.

Qualification: Participants’ academic qualifications were considered to include a range of educational backgrounds.

Rank: The academic rank of participants (e.g. lecturer, professor) was considered.

Age: A range of age groups was included to reflect different generational perspectives.

Work Experience: The length and nature of participants’ experience in academia was a key criterion.

Each of these criteria was carefully selected to ensure that the study encompassed a wide range of views and experiences within the Arab academic community, thereby enriching the quality and depth of our findings. Two rounds of interviews were conducted (see ) to elucidate cultural values influencing their satisfaction. Questions explored experiences, perceptions, behaviours, attitudes and identities related to Arab academic culture.

Table 1. Criteria for selecting interviewees.

2.3. Data analysis

Our study’s methodology incorporated qualitative and quantitative elements to analyze the data comprehensively. While the primary method was thematic content analysis, a qualitative approach, we also integrated a quantitative aspect by tracking the frequency of specific themes mentioned by participants. This combination allowed us to identify key themes and quantify their prevalence, offering a more nuanced understanding of the data’s significance. Further, we utilized Ayoa software, a tool typically associated with mind mapping, in a novel way to assist in our data analysis process. The software was employed to organize and categorize the qualitative data visually. Through the creation of mind maps, Ayoa helped us represent thematic connections and relationships between various data points. This visual representation was valuable in identifying patterns and themes within the data. Additionally, it provided a means to visually track the frequency of these themes, as the mind maps were adjusted to reflect the number of times specific themes emerged from the participants’ responses.

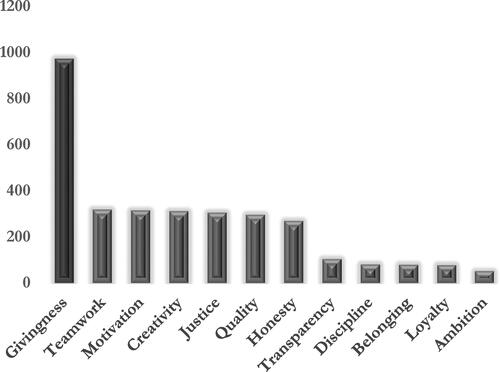

The innovative application of Ayoa in our study was instrumental in synthesizing and interpreting the qualitative data. It added another layer of analysis, enhancing our ability to make sense of complex data sets. This unique approach to data analysis, combining thematic content analysis with quantitative frequency tracking and mind mapping software, contributed significantly to the depth and reliability of our research findings. In Round 1, we asked 294 individuals to express what they liked and did not like about their organisations’ dealings with them. This process involved thematic content analysis, following the approach outlined by Krippendorff (Citation2018). Our analysis focused on identifying and categorizing themes within the responses, delineating 20 satisfaction categories. Each time a participant mentioned a specific aspect they liked or disliked, this mention was recorded and added to the frequency count of the relevant category. Notably, there was some overlap among the categories, with specific features occasionally fitting into more than one category, an aspect considered during the analysis. in the manuscript illustrates the frequency values of each category identified. The methodology employed here, particularly the thematic content analysis, allowed us to extract and organize the data from participants’ responses systematically ().

Figure 2. The frequency of different types of institutional givingness in Arab participants’ responses.

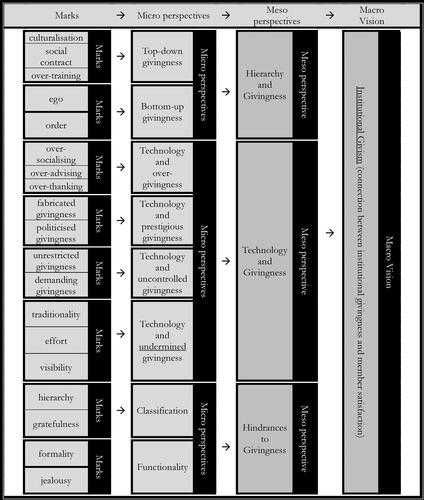

In the subsequent phase, Round 1 participants were once again engaged in interviews, roughly lasting ten minutes. They discussed their perspectives on the preliminary conclusion that the generosity of institutions might play a pivotal role in the satisfaction of Arabs in academic settings. A summary of each discussion was documented and shared with the respective participant for validation. Upon receiving their nod, the researcher used the Ayoa software (Bhattacharya & Mohalik, Citation2020) to derive patterns from the confirmed summaries. Each significant statement was labeled with a keyword or phrase that captured its essence. Subsequently, similar labels were grouped to form preliminary insights, termed ‘micro perspectives’. These micro perspectives were further amalgamated to develop more defined insights, termed ‘meso perspectives’. Ultimately, these meso perspectives converged to formulate an overarching ‘macro perspective’, which aimed to provide a conceptual foundation for ‘institutional give’—highlighting the potential link between an institution’s generosity and the contentment of its employees. This entire approach was shaped by the feedback from Round 1 and further refined in Round 2. presents a visual representation of this process and its outcomes.

We have meticulously applied Grounded Theory Analysis, as originally conceptualized by Glaser et al., (Citation1968). This method, distinct from other qualitative approaches, involves a systematic and iterative process. We initiated our analysis with open coding, identifying initial categories. This was followed by axial coding, as explained by Charmaz (Citation2014), to establish connections between these categories. The process was iterative, involving continuous data comparison against emerging categories, ensuring a grounded understanding of the data.

Theoretical sampling, a cornerstone of Grounded Theory, was also rigorously implemented. This involved selecting participants and data sources to effectively contribute to developing our theory, as illustrated in Bryant and Charmaz (Citation2007). Furthermore, our analysis aimed to construct a substantive theory deeply rooted in our empirical data. This approach, advocated by Glaser et al., (Citation1968), was executed through a rigorous and reflexive data interpretation process, aligning our findings with meaningful theoretical insights. These steps underscore our commitment to the authentic application of Grounded Theory Analysis, ensuring credible and valuable outcomes for the academic community.

Three fundamental criteria were established to categorize the satisfaction feedback obtained during Round 1 and to formulate labels and insights at the micro, meso, and macro levels based on the Round 2 data. Initially, the researchers collaboratively defined the categories, labels, and insights, drawing upon their interpretative expertise and existing research knowledge. Subsequently, a rigorous validation process was undertaken, involving cross-referencing the content within and across interview transcripts.

An external expert was engaged to ensure the accuracy and fidelity of each satisfaction category and its corresponding label. The external expert verified the labels’ alignment with each category’s intended essence and confirmed the logical and narrative coherence of the progression from labels to the micro, meso, and macro insights.

In the subsequent ‘Findings’ section, each statement of result is accompanied by a set of numerals in both Arabic and Roman formats. Here, the Arabic numerals represent the interviewees, while the Roman numerals indicate the specific statement from the interview report linked to the finding. For instance, the notation (4-IV) would point to the fifth observation shared by the fourth respondent.

3. Findings and discussions

In examining the nuances of academic environments in Arab institutions, it is essential to distinguish between universal cultural elements and those unique to Arab culture. This research delves into specific Arab cultural traits, such as the emphasis on community, respect for hierarchy, and the value placed on personal relationships, significantly influencing the dynamics within academic institutions. These traits are explored in depth, contrasting with broader international cultural generalities to highlight their unique impact on academic satisfaction and institutional behaviours in the Arab academic context. This distinction enriches our understanding of how cultural specificity shapes academic environments, providing valuable insights for regional and international educational discourse.

3.1. Hierarchy and givingness (meso perspective)

This meso perspective is formed from two underlying micro perspectives. The initial one illustrates generosity cascading from higher echelons, with institutions and leadership extending benevolent acts towards their members. The second shows givingness moving up from the bottom of hierarchies, whereby members are directing giving behaviours towards institutions and managers.

3.1.1. Top-down givingness (micro perspective)

The first remark relates to culturalisation. It is instructive to highlight the proactive role of wider Arab culture and religious teachings in heavily promoting givingness (Al-Tuni, Citation2005; Ahmed, Citation2010; Hisani & Matlub, 2019). This cultural promotion of givingness has encouraged members of academic institutions to demand institutional givingness from their employers. Arab citizens are culturalised to be ‘excessive takers’ (201-LXI), requiring high levels of givingness from others, including their institutions.

The second mark relates to a social contract. Public sector organizations are socially expected to give more to their members than those in the private sector (111-LVIII). The expectations could be explained by the fact that many Arab countries sustain a type of ‘social contract’ (Thompson, Citation2019) wherein governmental givingness to citizens constitutes a fundamental social agreement and requirement. In the public sector, some organisations have regulations that grant employees the right to obtain international sponsorship to undertake overseas masters and doctoral study programmes (27-LXXX). An additional right allows researchers to receive a sponsorship to attend an international conference if their work is published in a high-quality journal (235-LXXXVI; 90-XLIV). Payment is given every time an employee attends a meeting for department councils or high committees (12-XLVI), and individuals get a monthly financial allowance if they receive a patent or their work is published in Clarivate Analytics- or Scopus-indexed journals (86-XLIII; 100-LXXI). Monthly allowances can also be given to those using certain technologies for teaching, employees who hold managerial positions (63-XLIV; 50-XXXVIII), or people working in isolated universities or teaching rarely studied subjects such as mathematics and information technology (250-LX). In short, in some organisations, employees’ salaries can ‘end up being full of allowances’ (43-XXIII). The giving nature of such regulations has educated people to assess their organisations mainly based on their capability to give to their members. This nature has fostered a culture of ‘takism’ (123-XLIII) among employees, whereby individuals become habituated to taking to the extent that they even ‘expect to obtain over-time allowances even if work requires no overtime’ (34-LXXVII; 25-XCIII). In general, when Arabs want something from someone, they tend to place so much pressure on him/her to give them what they want. However, if someone else wants to get something from them, they tend to keep postponing, using such phrases as ‘tomorrow, tomorrow’. They would generally like it to be easy to take but difficult to give. They usually find it difficult to put themselves in others’ shoes.

The third mark is over-training. Some individuals require that their institutions provide them with many training opportunities, to the extent that members may be ‘over-trained’ (150-LXII). However, many are keen on training (and the resulting qualifications) and accumulate training credentials simply because they want to use these certifications as credits for promotion. Training is therefore undertaken, not for the sake of enlightenment but rather for promotions and increased monetary earnings. Members demand attendance certificates for any offline or online workshop or training session, irrespective of how small or brief it is (30-LXIV). They also require that institutions give trophies (or, at minimum, certificates of gratitude/acknowledgment) ‘in almost every small or large celebration’ (75-LXXVIII). One interviewee referred to many shops where ‘trophies are made from different materials in different forms and elaborate styles’ (55-LVI), and another respondent mentioned ‘long streets dedicated to trophy shops’ (2-LIX). It is common practice that ‘one has at home a bundle of shelves allocated for trophies’ (233-XXXVI) – having such shelves is socially appreciated and is regarded as signifying and illustrating individuals’ levels of professional success and community engagement. In this context, the givingness of institutions to members (here, in the form of certificates and trophies) is essential to members as it symbolises their efforts.

The tendency towards receiving (salary and related benefits) promoted by a culture of ‘takism’ and away from giving (through job performance) is reflected by dissatisfaction with Western models of performance appraisal that link rewards to objective measures of performance (Alharbi, Citation2018; Harbi et al., Citation2017).

3.1.2. Bottom-up givingness (micro perspective)

The first mark relates to the ego, ‘a well-established character of many bosses, which can be fulfilled by being over-thanked and over-praised by members’ (32-XCVI). Managers generate a ‘narcissistic character’ (98-XXXVIII) due to being over-thanked and over-praised. These behaviours are ‘not socially regarded to undermine the praiser and thanker’ (71-LIX); rather, they are perceived ‘as characteristics of a good employee’ (92-XXXVIII). Arabic literature contains many poems and narrations wherein inferiors over-compliment their superiors who, in return, give them a gift – the worth of the gift may increase if the compliment is more exaggerated (Mafqudat, Citation2003). Managers may ‘ask employees not to over-praise them, but they normally do not mean it as they just fake modesty and humbleness’ (261-XLV). One interviewee commented that ‘ingenuine over-thanking is not naively given, and is, rather, articulated in a clever way that makes the thanked feel that the thanker is genuine’ (42-XCVI). Because Arab employees and students are accustomed to over-complimenting managers and teachers, when studying abroad, they sometimes continue to do so with non-Arab supervisors and teachers, who may find this behaviour’ strange and over-the-top’ (155-LIII). The nature of thankful expression and emotional givingness can vary from one social context to another.

The second mark is order. Although many managers show their superiors gratitude and praise, they do not extend the same to their subordinates (8- XCVIII). Where they do, it lacks sincerity. Therefore, emotional givingness only travels up from the bottom – not vice versa (33-XXIII). To illustrate the point, when an employee ends their service, their manager may send a letter to thank them for their work. These letters are ‘standard and granted to everyone regardless of whether one does a good or bad job’ (66-XLIV); therefore, they represent ‘thanks with no thanks’ (235-LXXX). One interviewee remarked that ‘in the presence of those above them, thankless managers may suddenly become very generous in thanking those below them so as to fraudulently show those above them how kind and supportive they are to their team members’ (6-LXXVIII). Another respondent added that, in some cases, when people gain temporary access to power over an individual or institution, they become emotionally ungenerous. In his words, ‘if a customer has swift power over an institution through a customer satisfaction survey, their evaluation is more likely to be mean, meaning that the results of such surveys are normally negatively skewed’ (44-XXXVII). Bottom-up givingness reflects Arab culture’s high power distance that privileges those in positions of authority, whether through their job or age (Al-Ghanim, Citation2012).

3.2. Technology and givingness (meso perspective)

It is worth exploring the ways in which offline givingness has influenced online givingness (Al-Saggaf, 2004; Samin, Citation2008).

3.2.1. Technology and over-givingness (micro perspective)

The first mark in this area is over-socialising. It seems from our data that, considering that Arab men and women tend to be ‘social’, there is an expectation for institutions to give members space for having conversations (28-LXXII; 45-LXXXIV). Many Arab people love to share their experiences, leading to frequent meetings that are also usually long (151-XLIX). Some expect institutions to give members (and customers) space for unexpected visits. Office visits are typically unexpected or arranged spontaneously at short notice. They tend to be lengthy, and visitors cannot be declined even if the person they are visiting was previously occupied (27-LXIII). Irrespective of how brief an office visit is, employees are expected to serve visitors tea, coffee, dates, chocolate and biscuits (58-LV). Some workplaces employ ‘a person whose job is merely to serve tea to visitors and participants in meetings’ (81-XLIII; see also Eidrat, Citation1997). The interest in socialising at work has now also been transferred to online settings, with institutions’ members spending much of their time chatting with their contacts through WhatsApp during working hours. As one of our interviewees stated, ‘offline over-socialising has become online in the forms of over-tweeting and over-retweeting’ (144-XLVI).

The second mark relates to over-advising. In face-to-face contexts, Arab culture can aptly be termed a ‘counsel-centric society’ (60-LXXVII) where individuals advise (in fact, often ‘over-advise’ [81-LIII]) each other, meaning that individuals receive a great deal of advice from colleagues regularly. Among colleagues, ‘unsolicited advice is given on how to dress, how to decorate the office and how to raise their children’ (41-LII). This offline practice has been transferred to the online domain, with social media users over-advising one another (244-LXXVIII). Conventionally, Arab society is ‘a verbally giving society’ (1-LVI), in the sense that individuals (even scholars) prefer, for instance, to share information and knowledge in verbal rather than written form. As a corollary, sharing knowledge through digitally recorded lectures is common and constitutes the norm. However, due to social media, acts of sharing information and expertise have often taken a written form, such as tweets.

The third mark is over-thanking. As mentioned above, individuals tend to over-thank their superiors in offline settings. This trend has also appeared on social media (e.g. Twitter), with employees and students expressing excessive gratitude to their superiors (managers and teachers) by over-liking and over-retweeting their posts (276-LVIII). That said, some people who show these behaviours also have anonymous Twitter accounts through which they over-criticise and even bully their superiors to the extent that, in some cases, authorities have had to intervene and set strict regulations to protect people (80-LXXXI; 56-LXV). Therefore, it seems reasonable to contend that social media has given rise to the two extremes of identifiable over-thankers of superiors alongside anonymous over-criticisers (23-LIX; 15-XXIX; 10-L).

3.2.2. Technology and prestigious givingness (micro perspective)

The first mark is fabricated givingness. Within cultural contexts, generosity is often seen as a reflection of honesty, valour, influence, nobility, and knightly attributes (70-LXXVIII). Researchers like Ahmed (Citation2010) support this cultural perspective. To uphold these generosity-driven societal merits, individuals and institutions invest substantial resources in prominently showcasing their benevolence. They exploit various avenues to project this trait, with social media being a prime channel. On such platforms, numerous users exhibit two distinct acts related to generosity. The foremost act centers around the portrayal of contrived intellectual generosity. When an individual participates in a small workshop or performs an ordinary daily task, they may tweet about it exaggeratedly and share photos on social media, presenting it as ‘an exceptional event or achievement’ (120-XXIX). The second matter concerns the fabrication of emotional givingness. When an individual tweets about the death of a relative, they will receive many replies from strangers sharing their condolences to show their followers their emotional givingness (97-XCVI; 11-XXVII). Likewise, when people attend weddings or funerals, visit a hospitalised person or show their support for individuals who are in need, they will often tweet about these actions and post pictures to exhibit their emotional generosity to their followers (141-XCIII).

The second mark is politicised givingness. There is little doubt among the interviewees that many social media users work hard to display a sense of ‘community service’, ‘voluntarism’ and, thus, givingness (37-XXXV). In brief, social media channels are more like ‘theatrical stages’ (31-XLVII) that allow people to show off their quality of givingness. Acts of generosity are often not driven by altruism but because such behaviour is a pathway to societal dominance, recognition, esteem, influence, and honour (Hammadi, Citation2007). Many individuals are interested in offering training, not for societal development but to be recognised for being cognitively giving, which facilitates one’s ascent on the hierarchy of prestige and ranks (Al-Barghathi, Citation2014). Training and consultation are prevailing activities to the extent that ‘there has emerged a joke that, these days, everyone is a trainer and a consultant’ (10-L).

3.2.3. Technology and uncontrolled givingness (micro perspective)

The first mark is unconstrained givingness. If an individual refuses to share information or knowledge, this is considered ‘a firmly punishable vice and blameworthy conduct’ (20-XXXVIII. Cognitive stinginess is commonly perceived as ‘one of the worst and ugliest types of stinginess’ (Al Saqaf, Citation2009, p. 17). In the Arab online domain, resources are usually made ‘open access’ by default, which is a conscious or unconscious reflection of Arab cognitive givingness (38-XCVI). The high acceptance of open-science/open-source policies associated with givingness gives Arab academic institutions and, thus, their members an advantage in implementing these policies. Intellectual property and copyright laws hardly exist in this culture as they contradict the Arab value of cognitive givingness (290-XLIV) – culturally speaking, ‘one does not expect to pay for obtaining knowledge’ (19-XXXVIII). Most books can be ‘illegally’ (in Western terms) downloaded online for free without legal restriction (12-XCVIII). For some of our interviewees, when knowledge is transformed into materialistic forms, it should remain available at no cost in line with the Arab tradition of generosity with materials (266-LXXX). One interviewee specifically stated that ‘knowledge should not be influenced and controlled by the capitalistic mindset’ (33-LXXXVIII), and another claimed that ‘knowledge should always belong to the public domain, not to the private domain, and should not be propertised’ (16-LV).

The second mark is demanding givingness. Our data indicates that many members use social media to exert considerable pressure upon their institutions to give them more and more (even beyond what they deserve) – they can be termed ‘demanding members’ (42-XC). Whether or not their institution is giving to them, and to what extent, is a constant inquiry that ‘colonises the mindset of many members’ (76-XCIV), primarily occupying many employees’ daily online (and, of course, offline) discourse (280-LXVIII). Thus, many members ‘read their institution through its ability to give to them’ (44-LXVIII). If the institution ensures a sense of givingness, members will feel satisfied even if many other values are discarded (18-XVII).

In some cases, employees expect to be given more by their institutions despite their limited givingness to those institutions (16-XX). Many employees are ‘takenism’-driven, more inclined to take from their institutions than to give back to them. As Arabs consider institutional stinginess an unacceptable behaviour, if they feel neglected by their institution, frustration can accumulate, and negativity can spread throughout the institution (70-LXXVIII). Additionally, their loyalty to their institution will drop dramatically (35-LXXXIX). Consequently, they may only undertake minimal work for their institutions and begin secretly doing other jobs elsewhere through which they feel like they are given more (281-LXXXIX). To illustrate, academics in the education and technology fields who feel that their institution has failed to give them sufficient wages may start doing less academic work while taking on various side businesses (e.g. work in cafés, real estate, or sports shops) unrelated to their academic domain and through which they can obtain more income (35-LXXXIX).

3.2.4. Technology and undermined givingness (micro perspective)

Our data illustrates that, in some cases, what matters is not merely givingness itself but also the means of giving (77-LXVIII). How givingness is delivered can culturally increase or undermine the value of what is given for both the giver and the receiver (96-XXV). Givingness can be delivered in culturally respectful or disrespectful ways (24- XLVIII); in other words, although two individuals may be given the same thing, how it is given illustrates who is accorded more respect (288-XLVIII). Increasing or decreasing the value of givingness through its delivery can be carried out in three main ways (i.e. by one of three marks).

The first mark is traditionality. Giving by hand or in person is socially perceived as more respectful than digital giving (9-LX). Giving in person demonstrates more respect than when given via technological means (84-XX). Technology has modernised some ways of delivering givingness, thereby undermining its value (15-LIV), which is why givingness ‘is more appreciated if delivered in traditional and old-school manners’ (21-LXIX). The second mark is effort. Givingness is more appreciated and viewed as having ‘deeper’ (66-LXXI) meaning based on the giver’s effort. Giving is thus admired based on ‘not necessarily its worth but rather the effort that the giver has put in’ (79-LIX). In this light, technologically delivered givingness requires less effort and is often less appreciated than manual delivery. The third mark is visibility. Givingness appears to be ‘more valued if more people know of and hear about what is given’ (86-LXXIII). To illustrate, if an individual is given thanks in offline gatherings (e.g. meetings or events), this is considered less valuable than when one is given thanks online (e.g. on Twitter, where there is a higher level of visibility).

3.3. Hindrances to givingness (meso perspective)

Most of the reported hindrances are primarily related to emotional givingness. Hence, in this section, the focus comes to rest mostly upon this type of givingness.

3.3.1. Classification (micro perspective)

The first mark is hierarchy. Thanking is understood to travel in only one direction – from the top to the bottom of hierarchies. For many managers, ‘thanks are like rain, coming down from the top’ (52-XL). By these approaches, parents, teachers and managers may not give thanks to children, students and employees, respectively (109-XXIV). The connections between managers and employees are more like the relationships between wealthy and working-class individuals, whereby the former infrequently thank the latter (18-LXI; 23-XXII).

The second mark is gratefulness. Gratefulness, and therefore thankfulness, are expected to travel from lower-level employees to managers, and not in the opposite direction. To illustrate this point, one interviewee stated, ‘managers are the ones who have done a favour to employees by granting them the job and, therefore, should be thanked with gratitude and should not thank employees’ (58-XCVII). Similarly, gratitude (and, thus, thankfulness) is expected to flow from junior to senior managers, not the reverse. That is, executive managers employ middle managers, who employ lower managers; hence, executive managers demand gratitude from middle managers, who demand it from lower managers (199-XXXVI). In Arab culture, gratitude is a profound value in that individuals will constantly remind others that they did them a favour once (85-LV; 28-XXV; 57-XXVI). When someone does something ‘good’ for others, those others should show gratitude for the rest of their lives – for this reason, ‘many teachers feel that their students should be grateful to them all their life for having helped educate them’ (222-XVIII).

3.3.2. Functionality (micro perspective)

The first mark is formality. Some supervisors may not express gratitude to their employees because they want to maintain an emotional power gap (Hofstede, Citation2011) with them. They are concerned that gestures of gratitude may reduce this gap and make their subordinates feel unduly comfortable with them (181-XXXVI). Some of our participants believe that the relationship between managers and workers is often characterised by a high degree of formality, which discourages managers from expressing gratitude (13-LXVI; 71-LXVII). To consider a similar example from broader society, the relationship between fathers and children tends to be formal, discouraging many fathers from directly thanking their children (50-LXXIII; 16-LXXVI).

The second mark is jealousy. At times, some employees are cognitively ungenerous towards their colleagues. They see it as ‘wise’ (83-XXXV) and ‘clever’ (97-LX) practices that they do not share knowledge with them. They echo the widely held Arab attitude that ‘when one wants to do something, one shall not tell others, who may hinder one out of jealousy’ (26-LXXXIX). The last aspect seems consistent with the strong desire to increase one’s influence found in Arab culture (Dwairy et al., Citation2006). Further, it may be a way of handling the strong tendency to interfere in others’ affairs and giving unsolicited advice found in Arab culture (Buda & Elsayed-Elkhouly, Citation1998). In an academic work environment where knowledge is critical, reluctance to share it can result in the absence of job satisfaction among those denied the knowledge.

Some employees feel anxious that colleagues may direct ‘the evil eye’ (14-LXXXVIII) towards them, a look given when, deep inside, an individual feels jealous of others who have a certain positive quality in the hope that they will lose it. Some people may not share their thoughts because they fear that others may steal their ideas; hence, seminars are limited among postgraduates and even academics (176-LXXI; 9-XV; 15-XVI). This aspect contradicts the collectivist dimension of Arab culture, where refusal to share information or knowledge is considered ‘a firmly punishable vice and blameworthy conduct’ (20-XXXVIII) but is consistent with a strong desire to increase one’s influence (Dwairy et al., Citation2006).

Moreover, people may not share their thoughts out of concern that managers may stop them from implementing their ideas, especially given that some Arab managers are worried that any social innovation undertaken by academic employees may bring negative attention from society, leading to the managers themselves being punished for not stopping the innovator. This highlights that one of the roles of managers in the Arab academic domain is to ensure that researchers do not take culturally and socially unacceptable actions, an aspect coming from the Arab culture’s high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Citation2011). Managers’ actions in this regard impede what Hertzberg identified as intrinsic aspects of job satisfaction.

4. Concluding remarks

This article on cultural psychology examines the key factor behind Arabs’ satisfaction in academia, utilizing an innovative two-part methodology. The study identifies ‘institutional givingness’ as the most influential factor, supported by various scholars (Alsarihi, Citation1996; Al-Otaibi, Citation2004; Khadir, Citation2015; Abdulrahman, Citation1981). Arabs’ satisfaction levels are heavily influenced by institutional givingness, a top personality trait in Arab culture, reflected in their academic institutions and viewed as the primary lens for assessing the world (Albishri, Citation2002; Bishara, Citation2018; Alkhamsia, Citation2009; Al-Takriti, Citation2012; Musa, Citation2018). The research highlights that Arabs’ diverse values converge on generosity, a central value and primary determinant of satisfaction (Abdulrahman, Citation2001; Al-Awadi, Citation1997; Al Zahrani, Citation2002; Al-Barghathi, Citation2014; Alwan, Citation2019). This concept is deeply embedded in Arab culture and widely represented in academic and non-academic Arabic literature (Tayzini, Citation1971; Badawi, Citation1976; Hammadi, Citation2007).

The study also notes the extensive portrayal of givingness in Arabic literature, emphasizing its universal celebration and social importance across economic strata (Mahjoub, Citation1997; Abu Mustafa, Citation1999; Zurzur, Citation2011; Hanfi, Citation2001; Rababaa, Citation1974; Al-Sudais, Citation1991; Hassani & Matloob, Citation2019; Saleh, Citation2012). The research contributes by establishing a philosophical framework for ‘institutional givism’, presenting givingness as a critical determinant of employee satisfaction overlooked in existing models, and proposing a new method to measure member satisfaction through content analysis of interviews (Alsharidt, Citation2002; Quraishi et al., Citation2010; Al Maskini, Citation1994; Ambrose et al., Citation2005). Future studies could explore the role of generosity in enhancing satisfaction and the potential of a ‘power and give’ approach in Arab environments, paralleling Kahane’s (Citation2010) ‘power and love’ concept.

The findings of this study, particularly the emphasis on institutional givingness and cultural nuances in Arab academic environments, have significant practical implications for policy and educational practices in these institutions. It suggests a need for policies that acknowledge and integrate cultural traits such as respect for hierarchy, the value of personal relationships, and the culture of ‘givingness’ into institutional frameworks. Educational leaders should consider developing programs that foster a culture of mutual respect and generosity, which aligns with Arab cultural values. This could involve revising performance appraisal systems to incorporate culturally relevant criteria and recognizing contributions beyond mere academic achievements, such as community involvement and interpersonal relationships. Moreover, technology policies should be adapted to support the unique ways in which Arab academic communities interact, such as facilitating online social interactions and knowledge sharing. Emphasizing these cultural characteristics in policy and practice could lead to more effective management and enhanced job satisfaction among staff and students, ultimately contributing to a more dynamic and culturally congruent academic environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Ali Alhazmi

Ahmed Ali Alhazmi (PhD, RMIT University) is a Saudi Arabian associate professor and is the head of the Education Department of Jazan University. His research interests include the fields of education, sociology, and anthropology, with a focus on the Arab context. His works have been published by some of the largest publishers worldwide (Springer, SAGE, Taylor & Francis, Palgrave, Nature Research, and Wiley), and he has written in different languages for impact-factor journals. He has co-formulated theories on retroactivism, multiple stupidities, the pedagogy of poverty, idiocy-dominated communities, crowd reflection, and the fragmentation of organisational identity.

Abdulrahman Essa Al Lily

Abdulrahman Essa Al Lily is an Amazon bestselling author, Oxford graduate, manager and associate professor. He is the director of the National Research Centre for Giftedness and Creativity and the editor-in-chief of the Scientific Journal of King Faisal University. He has published with the largest global academic publishers: Elsevier, Springer, Taylor and Francis, Wiley, SAGE, Palgrave, Nature Research and Oxford University Press. His writings and interviews have been translated into different languages, including Chinese, Spanish, German, Italian, Filipino, Arabic and English. He has co-coined the following theories and concepts: ‘multiple stupidities’, ‘retroactivism’, ‘idiocy-dominated communities’, ‘on-the-go sourcing’, ‘academic centrarchy’ ‘crowd-authoring’ and ‘crowd-reflecting’. For more info., visit: https://abdulallily.wordpress.com

References

- Alharbi, S. (2018). Criteria for performance appraisal in Saudi Arabia, and employees interpretation of these criteria. International Journal of Business and Management, 13(9), 1. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v13n9p106

- Ali, S. A., & Weir, D. T. (2020). Wasta: Advancing a holistic model to bridge the micro-macro divide. Management and Organization Review, 16(3), 657–18. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6750-6722 https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2020.27

- Abdulrahman, A. M. (1981). Almathalu walqim al’akhlaqiat fi alshier aljahli [Ideals and moral values in pre-Islamic poetry]. Journal of the Jordanian Arabic Language Academy, 4(13–14), 127–158. [in Arabic]

- Abdulrahman, D. (2001). Taeadudiat Alqim [Multiple virtues]. Cadi Ayyad University. [in Arabic]

- Abu Mustafa, N. O. (1999). Dirasatan mqarnt lasamat alshakhsiat ladaa ‘abna’ albadw walhudr fi albiyat alfilastiniati [A comparative study of personality traits among Bedouin and urban children in the Palestinian environment]. The Future of Arab Education, 4–5(16–7), 77–142. [in Arabic]

- Ahmad, A. R., Alhammadi, A. H. Y., & Jameel, A. S. (2021). National culture, leadership styles and job satisfaction: An empirical study in the United Arab Emirates. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(6), 1111–1120.

- Ahmed, A. M. (2010). Alqiam al’akhlaqiat fi shaear almukhdrimin: Alkaram namudhaja [Moral values in veteran poetry: Generosity as a model]. Dar Al-Ulum Journal for Arabic Language, Literature and Islamic Studies, 18(36), 315–344. [in Arabic]

- Al Maskini, F. (1994). Filsfat Alnawabt [The philosophy of constants]. Dar Al-Tali’a Publishing. [in Arabic]

- Al Saqaf, A. A. (2009). Sur albakhl walshah [Pictures of miserliness and stinginess]. Sunni Pearls, 1801(2), 1–28. [in Arabic]

- Al Smadi, A. N., Amaran, S., Abugabah, A., & Alqudah, N. (2023). An examination of the mediating effect of Islamic Work Ethic (IWE) on the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance in Arab work environment. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 23(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705958221120343

- Al Zahrani, A. H. (2002). Alkarm: Eawamiluh w abeadih alaijtimaeiat fi hayat alearab [Generosity: Its factors and social dimensions in Arab life]. King AbdulAziz Foundation for Research and Archives, 28(4), 97–137. [in Arabic]

- Al-Awadi, A. (1997). Alkarm qimat ‘akhlaqiatan eind alearab min khilal namadhij min alshier aljahli [Generosity is an ethical value for Arabs through paradigms of pre-Islamic poetry]. Alqayrawan Literature, 2(1), 7–22. [in Arabic]

- Al-Barghathi, S. H. (2014). Alqiam al’akhlaqiat lilkarm fi aleasr aljahli [The moral values of generosity in the pre-Islamic era]. Arabic and Islamic Studies, 5(11), 1–66. [in Arabic]

- Albishri, T. A. S. (2002). Hawl aleaql al’akhlaqaa aleurbaa [About the Arab virtuous mind]. The Future of Arab, 24(276), 55–72. [in Arabic]

- Al-Ghanim, K. (2012). The hierarchy of authority based on kinship, age, and gender in the extended family in the Arab Gulf States. Int’l J. Jurisprudence Fam, 3, 329.

- Alkhamsia, A. (2009). Tajdid aleaql al’akhlaqy: Aldarurat walmuntalqat [The renewal of the virtuous mind: Necessity and premises]. Rahanat Journal, 10(1), 4–10. [in Arabic]

- Al-Otaibi, M. K. (2004). Nizam aldiyafat walquraa fi wasat aljazirat alearabiati [Hospitality and village systems in the middle of the Arabian Peninsula]. The Journal of King Saud University, 16(2), 315–360. [in Arabic]

- Al-Rubaish, A. M., Rahim, S. I. A., Abumadini, M. S., & Wosornu, L. (2009). Job satisfaction among the academic staff of a Saudi university: An evaluative study. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 16(3), 97. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.96526

- Al-Saggaf, Y. (2004). The effect of online community on offline community in Saudi Arabia. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2004.tb00103.x

- Alsarihi, S. (1996). Hijab Aleadati: Arkiulujia Alkaram min Altajribat Iilaa Alkhitabi [Veiling Habit: Archaeology of generosity from experience to discourse]. Center of Arabic Culture. [in Arabic]

- Alsharidt, H. N. (2002). Bed aleawamil almuatharat fi almustawaa alradaa ladaa ‘aeda’ hayyat altadris ean alkhadamat almuqadamat lahum fi jamieat alyarmuk bialmamlakat al’urduniyat alhashimiati [Some factors influencing faculty member’s satisfaction concerning Yarmouk University services in the Hashmite Kingdom of Jordan]. The Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Social Sciences, 14(2), 39–57. [in Arabic]

- Al-Sudais, M. S. (1991). Mueamalat jar albayt eind alearab kama yanm eanha alshier alqadimu [Treating the neighbor of the house to Arabs as evidenced by old poetry]. Journal of Imam Muhammad Bin Saud Islamic University, 4(2), 249–279. [in Arabic]

- Al-Takriti, N. (2012). Filsfat Al’akhlaq Eind Alfaraby [The philosophy of virtue according to Al-Farabi]. Dar Dijlat. [in Arabic]

- Al-Tuni, A. S. (2005). Aikram aldayf li’abi ‘iishaq alharbi [Honoring the guest by Abu Ishaq Al-Harbi]. Islamic Knowledge, 10(40), 233–235. [in Arabic]

- Alwan, N. M. (2019). Maeayir alsuluk liqimat alkarm fi mashahid aldiyafat alearabiati [Standards of behavior for the value of generosity in Arab hospitality scenes]. Annal Journal for Humanities, 12(1), 177–208. [in Arabic]

- Ambrose, S., Huston, T., & Norman, M. (2005). A qualitative method for assessing faculty satisfaction. Research in Higher Education, 46(7), 803–830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-004-6226-6

- Andreassi, J. K., Lawter, L., Brockerhoff, M., & Rutigliano, P. (2012). Job satisfaction determinants: A study across 48 nations .

- Asan, J., & Wirba, V. (2017). Academic staff job satisfaction in Saudi Arabia: A case study of academic institutions in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 7(2), 73–89.

- Asfahani, A. M. (2024). Nurturing the scientific mind: Resilience and job satisfaction among Saudi faculty. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1341888. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1341888

- Badawi, A. (1976). Al’akhlaq Alnazariatu’ [Theoretical virtue]. Publications Agency. [in Arabic]

- Bataineh, O. T. (2014). The level of job satisfaction among the faculty members of colleges of education at Jordanian universities. Canadian Social Science, 10(3), 1.

- Bhattacharya, D., & Mohalik, R. (2020). Digital mind mapping software: A new horizon in the modern teaching-learning strategy. Journal of Advances in Education and Philosophy, 4(10), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.36348/jaep.2020.v04i10.001

- Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205

- Bishara, A. (2018). Swaal Al’akhlaq fi Alhadarat Alearabiat Al’iislamiata [Question of virtue in the Arab Islamic civilization]. Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. [in Arabic]

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (2007). The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. SAGE Publications.

- Buda, R., & Elsayed-Elkhouly, S. M. (1998). Cultural differences between Arabs and Americans: Individualism-collectivism revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(3), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022198293006

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Chipunza, C., & Malo, B. (2017). Organizational culture and job satisfaction among academic professionals at a South African university of technology. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 15(2), 148–161. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.15(2).2017.14

- Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Dwairy, M., Achoui, M., Abouserie, R., & Farah, A. (2006). Parenting styles, individuation, and mental health of Arab adolescents: A third cross-regional research study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(3), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106286924

- EDUCAUSE. (2023). 2023 Higher education trend watch. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.educause.edu/ecar/research-publications/higher-education-trend-watch/2023

- Eidrat, H. (1997). Altaqalid alaijtimaeiat lilqahwat ladaa earab albady [The social traditions of coffee for Bedouin Arabs]. Social Affairs, 14(56), 171–177. [in Arabic]

- Eskildsen, J., Kristensen, K., & Gjesing Antvor, H. (2010). The relationship between job satisfaction and national culture. The TQM Journal, 22(4), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731011053299

- Eyupoglu, S. Z., Jabbarova, K., & Saner, T. (2017). Job satisfaction: An evaluation using a fuzzy approach. Procedia Computer Science, 120, 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.297

- Gallup. (2022). The state of higher education 2022 Report. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.gallup.com/analytics/391829/state-of-higher-education-2022.aspx

- Gan, E., & Voon, M. L. (2021 The impact of transformational leadership on job satisfaction and employee turnover intentions: A conceptual review [Paper presentation]. SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 124, p. 08005). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202112408005

- Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; Strategies for qualitative research. Nursing Research, 17(4), 364. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014

- Gu, M., Li Tan, J. H., Amin, M., Mostafiz, M. I., & Yeoh, K. K. (2022). Revisiting the moderating role of culture between job characteristics and job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis of 33 countries. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 44(1), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-03-2020-0099

- Hammadi, A. J. (2007). Alqiam al’akhlaqiat eind alearab wa’athariha fi tawahudihim alqawmii qabl zuhur alaislam [Moral values among Arabs and their impact on their national unity before the emergence of Islam]. Journal of Babl University, 11(1), 154–160. [in Arabic]

- Han, J., Yin, H., Wang, J., & Zhang, J. (2020). Job demands and resources as antecedents of university teachers’ exhaustion, engagement and job satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 40(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1674249

- Hanfi, H. (2001). Alturath Waltajdidu [Heritage and renewal]. University Institute for Studies and Publishing. [in Arabic]

- Harbi, S. A., Thursfield, D., & Bright, D. (2017). Culture, Wasta and perceptions of performance appraisal in Saudi Arabia. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(19), 2792–2810. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1138987

- Hassani, K. H., & Matloob, Q. F. (2019). Alqiam alhadariat eind alearab qabl alaslam alkarm waljud anmwdhja [Social values among Arabs before Islam: Generosity as a model]. Journal of Tikrit University for Humanities, 26(10), 183–195. [in Arabic]

- Hauff, S., Richter, N. F., & Tressin, T. (2015). Situational job characteristics and job satisfaction: The moderating role of national culture. International Business Review, 24(4), 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.01.003

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. SAGE Publications.

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- Hussien, S. (2007). Critical pedagogy, Islamisation of knowledge and Muslim education. Intellectual Discourse, 15(1), 87–104.

- Janićijević, N. (2011). Methodological approaches in the research of organizational culture. Economic Annals, 56(189), 69–99.

- Jawabri, A. (2017). Job satisfaction of academic staff in the higher education: Evidence from private universities in UAE. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 7(4), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v7i4.12029

- Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Klinger, R. (2008). The dispositional sources of job satisfaction: A comparative test. Applied Psychology, 57(3), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00318.x

- Kahane, A. (2010). Power and love: A theory and practice of social change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00318.x

- Khadir, B. K. (2015). Tahlil ayat albukhl fi alquran alkarim fi daw’ altadawliaat almudamijat [Analyzing verses of miserliness in the Holy Qur’an]. Awruk Journal for Humanities, 8(1), 85–134. [in Arabic]

- Kim, L., Pongsakornrungsilp, P., Pongsakornrungsilp, S., Horam, N., & Kumar, V. (2023). Key determinants of job satisfaction among university lecturers. Social Sciences, 12(3), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030153

- Kinman, G. (2014). Doing more with less? Work and wellbeing in academics. Somatechnics, 4(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2014.0129

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Kuwaiti, A. A., Bicak, H. A., & Wahass, S. (2020). Factors predicting job satisfaction among faculty members of a Saudi higher education institution. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(2), 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-07-2018-0128

- Lee, B., Lee, C., Choi, I., & Kim, J. (2022). Analyzing determinants of job satisfaction based on two-factor theory. Sustainability, 14(19), 12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557

- Mafqudat, S. (2003). Alqiam al’akhlaqiat lilearabii min khilal alsheraljahli [The moral values of the Arab through Aljahli’s poetry]. Journal of Humanities in Mohammed Khdeer University, 1(1), 183–196. [in Arabic]

- Mahjoub, M. A. (1997). Dirasat fi Almujtamae Albadawii [Studies in the Bedouin Society]. University Knowledge House. [in Arabic]

- Maslow, A., & Lewis, K. J. (1987). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Salenger Incorporated, 14(17), 987–990.

- Masum, A. K. M., Azad, M. A. K., & Beh, L. S. (2015). Determinants of academics’ job satisfaction: Empirical evidence from private universities in Bangladesh. PloS One, 10(2), e0117834. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117834

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Miah, M. T., & Hasan, M. J. (2022). Impact of Herzberg two-factor theory on teachers’ job satisfaction: An implication to the private Universities of Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management Research, 10(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.37391/IJBMR.100101

- Mollo, M. (2023). Academic cultures: Psychology of education perspective. Human Arenas, 6(3), 542–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-021-00238-7

- Musa, M. Y. (2018). Mubahith fi Falsifat Alakhlaq [Research in the philosophy of virtue]. Hindawi Foundation. [in Arabic]

- Newstrom, J. W., & Davis, K. (2002). Organizational behavior. (1 Ith ed.). McGrawHill Higher Education.

- Oppong, R. A., Oppong, C. A., & Kankam, G. (2017). The İmpact of organisational culture on employees’ job satisfaction in colleges of education in Ghana. African Journal of Applied Research, 3(2), 28–43.

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A., Almeida, H., & Borrego, Y. (2022). Social support and job satisfaction in nursing staff: Understanding the link through role ambiguity .

- Parsons, T. (1990). Prolegomena to a theory of social institutions. American Sociological Review, 55(3), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095758

- Quraishi, U., Hussain, I., Syed, M. A., & Rahman, F. (2010). Faculty satisfaction in higher education: A TQM approach. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 7(6), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v7i6.127

- Rababaa, A. (1974). Almujtamae Albadawiu Al’urduniyu fi Daw’ Dirasat Anthirubulujiati [The Jordanian Bedouin community in the light of an anthropological study]. Publications of the Department of Culture and Arts. [in Arabic]

- Saleh, T. I. (2012). Alqiam fi alshier aljahilii dabtaan ajtmaeyaan: Qimat alkarm anmwdhjaan [The values in pre-Islamic poetry as social control: The value of generosity as a model]. Journal of Kirkuk University Humanity Studies, 7(1), 1–38. [in Arabic]

- Samin, N. (2008). Dynamics of Internet use: Saudi youth, religious minorities and tribal communities. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 1(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1163/187398608X335838

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Serinkan, C., & Kiziloglu, M. (2021). The relationship between organisational culture and job satisfaction in higher education institutions: The Bishkek case. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 29(2), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPso.15319

- Shihade, M. (2020). Asabiyya–Solidarity in the age of barbarism: An Afro-Arab-Asian alternative. Current Sociology, 68(2), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392119898203

- Singh, M., & Bhattacharjee, A. (2020). A study to measure job satisfaction among academicians using Herzberg’s theory in the context of Northeast India. Global Business Review, 21(1), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918816413

- Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences (Vol. 3). Sage.

- Spencer-Oatey, H. (2000). Introduction: Language, culture and rapport management. Culturally Speaking: Managing Rapport through Talk across Cultures, 19, 1–10.

- Tayzini, T. (1971). Mashrue Ruyatan Jadidatan Lilfukr Alearbii [A new vision project for Arab Thought]. Dar Dimashq. [in Arabic]

- Thompson, M. C. (2019). Being young, male and Saudi: Identity and politics in a globalized kingdom. Cambridge University Press.

- Thornberg, R. (2012). Informed grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.581686

- Tran, Q. H. (2021). Organisational culture, leadership behaviour and job satisfaction in the Vietnam context. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-10-2019-1919

- Udrea, E. C., & Semenescu, A. (2023). Determinants of academics’job satisfaction: Examining the perspective of academic staff. Revista de Tehnologii Neconventionale, 27(1), 46–52.

- Wang, H., Jin, Y., Wang, D., Zhao, S., Sang, X., & Yuan, B. (2020). Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among primary care providers in rural China: Results from structural equation modeling. BMC Family Practice, 21(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-1083-8

- Wilson, M. E. (1996). Arabic speakers: Language and culture, here and abroad. Topics in Language Disorders, 16(4), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-199608000-00008

- Yean, T. F., Johari, J., Yahya, K. K., & Chin, T. L. (2022). Determinants of job dissatisfaction and its impact on the counterproductive work behavior of university staff. SAGE Open, 12(3), 215824402211232. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221123289

- Yeo, R., & Dopson, S. (2018). Getting lost to be found: The insider–outsider paradoxes in relational ethnography. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 13(4), 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-06-2017-1533

- Zurzur, N. K. (2011). Altttwr aldalalia li’alfaz albakhl bayn lughat alshier aljahilii walighat alquran alkarim [The semantic development of miserliness between pre-Islamic poetry and the language of the Noble Qur’an]. Al-Mustansiriya Journal of Arts, 9(54), 1–43. [in Arabic]