?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study was designed to investigate the impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures and their associated self-reported threats on female labor force participation (FLFP) in Uganda following the March 20th, 2020 shutdown of the economy by the government. The interest in women in this study stems from the fact that despite the economic activity shutdown, women’s work and roles extend even to their homes. The participation of women in the labor force is a significant factor in the development and growth of society. It is also worth acknowledging that in developing nations like Uganda, women join the workforce as a coping strategy for shocks (i.e. COVID-19 pandemic) and also because of poverty. Therefore, using the Uganda High-Frequency Phone Survey on the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (i.e. COVID-19) pandemic (UHFS) data set. That was collected by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) immediately after the government instituted strict lockdown measures, our results indicated a 17% reduction in FLFP especially in the early days of the economic shutdown. The findings also indicated larger effects on female labor market activities in case of extreme lockdown when both partners were locked down (i.e. both stayed home at the same time). However, the impact of lockdown was more pronounced than the self-reported COVID-19 threat among women with children as opposed to those without children. We also find larger predicted probabilities for female labor market participation for those employed than those unemployed as the pandemic evolved. Given the above results, our results are somewhat consistent with the famous household labor supply theories. As a policy direction, the government should institute a gender-sensitive pandemic response social support plan. This would enable the government to compensate women for the double burden (i. e. formal employment loss and increased unpaid household work) suffered during such pandemic outbreaks in future.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Our research delves into a critical aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact: the participation of women in the labor force in Uganda. Through the lens of the 2020 Uganda High-Frequency Phone Survey on COVID-19, we aim to uncover the unique challenges and opportunities faced by Ugandan women during this unprecedented time. By analyzing this data, we hope to shed light on how the pandemic has influenced women’s ability to engage in economic activities, support their families, and contribute to the nation’s development. Our findings offer insights into the immediate effects of the pandemic but also provide valuable information for policymakers, organizations, and individuals striving to create a more equitable and resilient society for women in Uganda and beyond.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The origins of the coronavirus the disease 2019 pandemic (i.e. COVID-19) can be traced to Wuhan, a city in a central province of China. The disease is believed to have been caused by a novel coronavirus known to epidemiologists as the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Mckibbin & Fernando Citation2020). With its first epicenter in China, COVID-19 quickly spread around the world like wildfire at the start of 2020 which caught the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a global pandemic of international concern. This was very important to enable governments around the world to coordinate efforts in response to the pandemic. The impact of COVID-19 on the global economy has been immersed and it is more pronounced in developing countries like Uganda, i.e. just mortality and morbidity concerns. For instance, there have been interruptions in the production and global supply chains, given the fact that much of transportation systems were halted as a measure to curb the spread of the disease. According to (Alon et al., Citation2020; Mckibbin & Fernando, Citation2020), the pandemic caused too much turmoil and panic in the global business community which has caused household consumption and employment distortions affecting household purchasing power. Add despite some recoveries in some developed economies, some developing parts of the world are still nursing social and economic distortions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Fiaschi & Tealdi, Citation2023; Yang et al., Citation2024).

In Uganda, in response to the pandemic outbreak, the government was swift in the early stages of the disease and instituted a wave of sweeping strict containment measures as early as the 18th of March 2020 even without a single case reported by then (Lone & Ahmad, Citation2020; MoFPED, Citation2020; Nattabi et al., Citation2020; Ssonko, Citation2020; Wemesa et al., Citation2020). Such measures among others included local and international travel restrictions including the banning of public transport and closure of the international airport, a 14-day quarantine instituted for those suspected to have the disease, international and local conferences and gatherings including religious, weddings, and musical concerts, and shows were banned to disperse crowds to ensure social distancing. Eight days after Uganda reported its first COVID-19 case, the president on the 30th of March declared a national curfew that was to run from 7 pm to 6:30 am (Nattabi et al., Citation2020). These strict containment measures helped the country to avert the catastrophe that waited for it, this is because any surge in infections would have overwhelmed the national healthcare system which is underdeveloped and underfunded. In addition, the fear factor in the early days of the pandemic also played a crucial role in forcing people to obey the standard operating procedures (SoPs) instituted by the Ministry of Health (MoH) for the fear of loss of lives as witnessed in developed countries like Italy, Spain and the United States of America (Aldila et al., Citation2020; Lone & Ahmad, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2020). However, despite the effectiveness of some of those strict measures on the spread of the novel coronavirus, it is extremely important to understand how these measures impacted the different dimensions of the household, particularly their likelihood of participating in the labor market and its impact on the general household welfare as the crisis evolves.

Most countries implemented stringent COVID-19-related measures with the sole aim of halting the progression of the disease. These measures included but were not limited to; curfews, lockdowns, restrictions on movements, hand washing, and social distancing among others (MoFPED, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2021). With these measures, the world generally acknowledged that the disease would have a great impact on economies and populations alike, but to what extent and what the impact would be was largely a grey area. It is against this background that an in-depth look at how the Pandemic affected women who are the most vulnerable members of society especially under pandemics is imperative. A brief background shows that the last time the government of Uganda published official COVID-19 results was on 1 September 2020, as this time the official number of COVID-19 infections in Uganda stood at 18,002 cases, with 186 deaths (MOH, Citation2020; Nattabi et al., Citation2020; Ssonko, Citation2020). Despite the low levels of infection then, Uganda like many other countries took drastic measures to prevent the spread of the virus, including the closure of international borders, banning of public transport, and enacting a strict lockdown (see the full description of the measures undertaken in Nattabi et al., Citation2020; Ssonko, Citation2020; Wemesa et al., Citation2020). It is against this backdrop that this current study purposefully seeks to fill a gap in academic knowledge and generate evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s labor force participation in Uganda in particular using the first round of Uganda High Frequency Phone Survey on COVID 19. Despite comprising the majority of the labor force in Uganda, women and girls remain marginalized and discriminated against in decision-making processes, allocation and control of resources within families and communities, and in employment situations. Besides given the gender roles in the household coupled with lockdowns it is imperative to understand such impacts on women’s labor market metrics in Uganda in the early stages of the pandemic.

To understand the impact of COVID-19 on female labor force participation in Uganda, we had to answer a few key questions. The main research questions were: What immediate impact did COVID-19 have on female labor force participation (FLFP) in Uganda in the early stages of the pandemic? What are the specific sectors that women were working in then, and how has this evolved since the pandemic lockdown in 2020? In addition to this, the researchers wanted to establish what the possible long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the future of women’s employment in Uganda, focusing on what led to these changes.

1.1. Motivation

The motivation for studying the pandemic as it evolves is that effective sector-targeted policies can be designed to tackle the negative effects of the pandemic on the household and the economy at large. Secondly, several human rights organizations in Uganda have reported that COVID-19-related containment measures have combined killed more people than the disease itself (see: Nattabi et al., Citation2020; Wemesa et al., Citation2020). For instance, lockdowns and the curfew have meant that families members are now forced to stay together in a limited space this has caused a rise in domestic violence and child abuse including rape and which has unfortunately resulted in isolated incidences of death across the country, given the fact that for many women and children stayed at home which exposed them to more danger. Other pandemic-related studies have reported similar results (see: Arenas-Arroyo et al., Citation2020; Corsi & Ilkkaracan, Citation2022; Utter, Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2024).

Our study aims to analyze the impact of COVID-19-related containment measures on female labor force participation given the fact that women’s time is divided between employment and home production. There is an assertion that women’s time and work at home instead increased during the pandemic thus we tried to test this notion (UBOS-Abstract, Citation2021). Secondly, the paper also documents the impact of income loss since the lockdown was instituted on working parents and its ripple impact on the household’s food security. Thirdly, the study also explains the linkages between job loss, homeschooling, or remote learning as welfare and household food security. Finally, the study incorporates heterogeneity anticipated between these relationships, particularly across regions, genders, and income groups among household members both employed and unemployed, with particular emphasis on women in the household.

To answer the questions raised in this paper, we made use of the first round of the National Pandemic Monitoring survey known as the HFPS on COVID-19 that was carried out by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) from the period of June 2020–May to 2021 under the support of the World Bank to enable countries to effectively monitor the pandemic as it evolves. Using this dataset, we compared employment status, income loss, and food security of households including time for homecare for both working and non-working women during the pandemic period.

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we analyze the impact of forced homestay (lockdown) on economic stress (income loss) and labor participation of women using a real-time pandemic-evolving high-quality data set. Given the fact the Uganda HFPS COVID-19 is based on Uganda National Panel Survey (UNPS) samples, we made use of pre-COVID-19 variables to endogenous for the initial conditions for working household members. Second, we explored the relationship between food security and work with special attention given to time allocation for home care and remote learning of children. Lastly, we analyzed the burden of COVID-19 along with gender, wealth quintile, and residence dimensions. Understanding these inter-relationships is important because it aids in the development of sector-specific policies and measures to mitigate and reduce both short and long-run negative impacts of the disease on women.

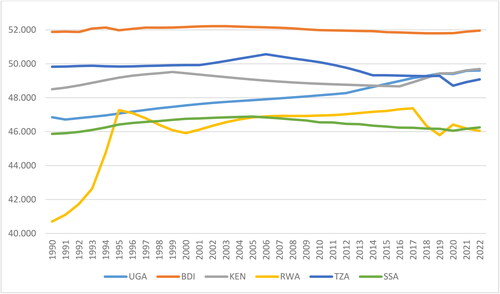

From , we can observe that female labor force participation in Uganda has been on an up-world trajectory since the early 1990s. The above trend can be explained by several factors, first is the continued level of political stability in the country and also increased levels of access to education by the girl child in Uganda. However, from 2019 when the COVID-19 Pandemic broke up, we can see a reduced growth in women’s employment. This could be explained by the sudden shock in caused by the pandemic-related measures such as lockdowns and job layoffs due to losses incurred by employers. Secondly, women mostly worked in the hard-hit sectors such as services sectors which relied on personal contact to deliver services. According to Verick, (Citation2018) and Winkler (Citation2022), the economic activity of women outside the home benefits society overall (i.e. higher economic growth) as well as girls and women (i.e. better health, less domestic abuse against women) in general.

Figure 1. Trends in Female Force Participation in Uganda Compared to other developing East African Counties and the Sub-Saharan African (SSA) Region in general.

Source: Authors compilation from World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank.

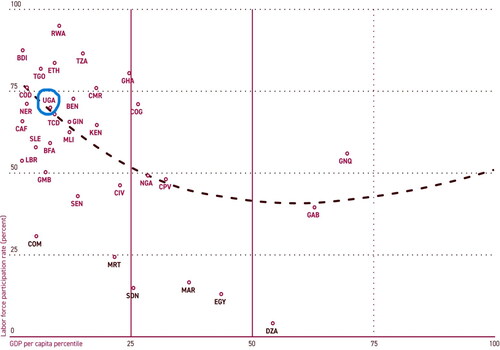

From the below, the smoothed average line is shown by the dashed line. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO3) assigns country codes (i.e. Uganda is UGA). It can be observed that countries denoted by black have the lowest FLFP rates for their level of GDP per capita. Income deciles are computed for each year between 1990 and 2017. The 25th and 50th percentiles are denoted by the vertical lines. Women’s involvement in the labor force has historically followed a U-shaped trajectory (Klasen et al., Citation2020). Women work in domestic businesses or on family farms for very little pay but they are joining the workforce as the countries are growing (Choudhry & Elhorst, Citation2018; Winkler, Citation2022). However, as the nation develops and family income rises, the family reclaims women’s time for domestic tasks such as taking care of the elderly and children. This idea might not, however, apply in nations whose religious legislation forbids women from engaging fully in the workforce, particularly in those in northern Africa. The graph shows Uganda exhibits higher levels of female labor force participation for its level of GDP per capita.

Figure 2. Female Labor Force Participation and Economic Growth, the U-shaped function.

Source: Gandhi (Citation2020), computed from WDI and ILOSTAT.

2. Literature review

There is already an established and still growing body of literature on the economic impact of health-related pandemics and epidemics on the economic performance and growth of any nation. Particularly health economists use population vital statistics such as child and maternal mortality and life expectancy to study the impact of the pandemic outbreak on the performance of the economy. For example, studies on earlier pandemics found a positive impact of the above measures on economic welfare and growth (see; Donovan & Labonte, Citation2020; Mckibbin & Fernando, Citation2020; Mwabu, Citation2007; Sarker, Citation2021)). Other studies on the impact of pandemics on the economy, have analyzed the impact of the pandemic on different dimensions of human life at both macro and micro levels for instance on firms’ performance in Italy (Balduzzi et al., Citation2020; Fiaschi & Tealdi, Citation2023), cost of school closures-(Psacharopoulos et al., Citation2020; Utter, Citation2021; Wemesa et al., Citation2020), Price Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic (Balleer et al., Citation2020; Bluedorn et al., Citation2021), Intimate Partner Violence under forced lockdown (Arenas-Arroyo et al., Citation2020; Goldin, Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2024), and Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19 (Tani et al., Citation2020).

The world has experienced several pandemics of varying catastrophic proportions ranging from HIV/AIDS, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and pandemic influenza with the deadliest being the 1918–19 Spanish influenza (Mckibbin & Fernando, Citation2020). According to the burden of the disease literature, there are several ways that a pandemic can impact the economy which are either direct or indirect (cost of illness) that result in economic burden. The traditional analysis of disease burdens has been to rely on death and morbidity records to estimate the loss of future productivity due to lost lives and disability. However, it has been said that these conventional methods of estimating the economic impacts of a pandemic that has no vaccination like in cases of HIV/AIDS and SARS underestimate the impacts. This provides a basis for deeply thinking about how to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as it evolves since the disease may not end any time soon.

According to Appiah, (Citation2018; Choudhry & Elhorst, Citation2018), diseases such as AIDS which has lived with humans for close to four decades have affected households, governments, and businesses through constraints on labor markets, loss of livelihoods, and increased private and public sector costs on treatment and care for disabled persons and disadvantaged children. Despite the damaging impacts of AIDS, there have been treatments and preventive measures that have minimized the risks associated with the disease and several studies have documented this success at a macro level. Other studies purely study determinants of female labor force participation (see; Jaumotte, Citation2003; Kiani, Citation2021; Klasen et al., Citation2020; Verick, Citation2018; Winkler, Citation2022), these studies conclude that female labor participation is unique due to the role of women in society more especially in developing world, where women not only participate in the labor markets but also bear children and take care of the family.

More specifically, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic in late 2019, there has been a plethora of studies from different parts of the world addressing the different dimensions of the impact of pandemics on COVID-19 pandemic on the different metrics of female labor force participation, among these include the following (Bluedorn et al., Citation2021; Corr, Citation2022; Corsi & Ilkkaracan, Citation2022; Fiaschi & Tealdi, Citation2023; Goldin, Citation2022; Jingyi et al., Citation2021; Lim & Zabek, Citation2021; Rahmadhani et al., Citation2021; Risse & Jackson, Citation2021; Sarker, Citation2021; Utter, Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2024).

A study by Goff et al., (Citation2020) examined the impact of COVID-19 on the education sector, the authors applied a within-subject comparison method to the survey data collected from college students just before and after the pandemic hit the United States of America to gauge their market attitude. They found evidence of a significant decline in the support for markets just before the pandemic started. Similarly, Psacharopoulos et al., (Citation2020) estimated the cost of school closures on education, they found that school closures reduce the future earnings of students according to the level of education, and this was larger developing countries. Closely related results are reported by Gaudecker et al., (Citation2020) in the Netherlands, where the authors found that economic welfare programs limited the impact of the pandemic on the job market in the early stages of the pandemic and thus work from home increase as a substitute for officer work.

Relatedly, Shin et al., (Citation2020) in South Korea found that there was an increase in foot traffic and a reduction in retail sales within a limited distance of the COVID-19 program.

At the micro-level, the impact of the pandemic has been analyzed by Arenas-Arroyo et al., (Citation2020) on the effect of COVID-19 on intimate partner violence (IPV) under economic shutdown conditions, using an online survey, their results indicate a 23% increase in IPV, and the impact of economic consequence is a large as that of the lockdown. In addition, the effect worsens if the position of men is threatened within the household. This result is supported by Tani et al., (Citation2020) who found that mental health was worse for working mothers than their non-working mother counterparts, and the disease burden on mental health greatly varied by gender and wealth quintile.

A paper by Jingyi et al., (Citation2021) examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labor market in ten ASEAN countries. The authors find that the pandemic indeed hurt the ASEAN economies. Job losses escalated, particularly affecting vulnerable workers in informal sectors, self-employed workers, gig workers, migrant workers, and micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. The authors further argued that the pandemic could reshape ASEAN’s digital landscape and the way work is done in the future. They further also highlighted disparities in labor force participation rates, unemployment rates, and education levels. The findings emphasize the importance of income support for workers and businesses, particularly in the informal sector, to prevent further economic decline and poverty. Similar arguments can be found in studies such as Kiani, (Citation2021) in Asia, Risse & Jackson, (Citation2021), in Austria, and (Alon et al., Citation2020; Corr, Citation2022; Donovan & Labonte, Citation2020; Utter, Citation2021) in the USA. But Goldin, (Citation2022) found contrary results in the USA where women’s labor participation did not decline during the early stages of the pandemic. However, an alternative perspective could argue that technological advancement and automation will not necessarily lead to widespread job loss and unemployment.

Bluedorn et al. (Citation2021) investigated the ‘she-cession’ phenomenon in a quarterly sample of 38 advanced and emerging market economies where women’s employment fell disproportionately during the pandemic. The authors showed that there is a large degree of heterogeneity across countries, with over half to two-thirds exhibiting larger declines in women’s than men’s employment rates. In this study, these gender differences in COVID-19’s effects are typically short-lived, lasting only a quarter or two on average. The previous study is supported by Goldin, (Citation2022) in the USA who also investigates the moniker of the ‘she-cession’ phenomenon due to the disproportionate impact that COVID-19 had on women than men, however, he argues that the impact of the pandemic in this part of the world was more between education and uneducated women and then between genders. In his study, Goldin, (Citation2022) finds contrary results that women did not exit the labor market in large numbers nor did they reduce the number of hours worked.

Related, Sarker, (Citation2021) examined the labor market and unpaid work implications of COVID-19 for women in Bangladesh. The author finds that indeed the pandemic exacerbated gender and socioeconomic inequalities, with feminized sectors such as agriculture and garments being hardest hit. Further, he also found that female workers lost their means of earning income, and were confined to their homes, leading to an increase in unpaid workloads, contrary to Goldin, (Citation2022). These results thus point to the fact the impact of COVID-19 was country-specific, comparing results from the USA and Asia.

Yang et al., (Citation2024) examined the impact of the pandemic on digitalization and employment gender gaps in Latin America. The authors argue that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated digitalization in these countries in several ways, thus acting as a catalyst for digital transformation across various sectors, thus pushing the region towards greater digitalization and adoption of technology. Their results showed that the region experienced a significant increase in e-commerce, with a 36.7% rise relative to pre-pandemic levels. For instance, over 13 million people in Latin America completed an online transaction for the first time in 2020. Secondly, there was a shift in the education delivery, with classes continuing through digital technologies. They also found that there was a surge in the use of telemedicine which increased access to healthcare, there was an increased digital adoption in various sectors, such as education, healthcare, and labor markets saw a significant increase in the use of digital technologies. There was also the creation of new job opportunities in fields like E-commerce, digital marketing, and software development, which were done remotely. Contrary arguments are provided by Fiaschi and Tealdi (Citation2023) in the Italian economy, where women were overrepresented in the informal service sector hit hard by the pandemic which reduced their labor force participation.

Finally, Corr, (Citation2022) analyzed the effect of the pandemic on different demographic groups’ labor force participation in the United States, considering factors such as gender, marital status, and having children under 18. Using a probit model, the study compared data from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to analyze the impact on labor force participation by using the US Census Bureau’s Monthly Current Population Survey data from March 2019 to February 2021. The findings indicate that, except for single males with children, all other demographics experienced negative effects during April and May 2020, with married and single females with children being particularly affected due to increased childcare responsibilities. In addition, due to extra childcare work for females, their labor participation was lower during typical school times. Other studies investigating different dimensions of female labor force participation during the pandemic included (Alon et al., Citation2020; Donovan & Labonte, Citation2020; Lim & Zabek, Citation2021; Utter, Citation2021;).

2.1. Literature summary

As a form of critique, one would argue that the gender impact analysis of COVID-19 neglects the experiences and challenges faced by men and that men too are affected by job losses and increased unpaid workloads. Thus a broader socioeconomic impact analysis should be undertaken instead. This is because the effects on men spill over to women since they share the same social spaces. Another perspective could be that while women may be disproportionately affected by the pandemic, it is important to consider intersectionality and acknowledge that different groups of women may experience varied impacts. For instance, in countries with racial problems, women from marginalized communities, such as women of color or women with disabilities, may face additional barriers and vulnerabilities that should be addressed (Corr, Citation2022; Lim & Zabek, Citation2021; Utter, Citation2021). However, we do not address this issue due to data limitations. Also solely focusing on women’s vulnerability in the labor market neglects the experiences of men who work in feminized sectors. The argument here could be that there is a need for a more comprehensive analysis that includes all individuals in feminized industries, regardless of gender, and works towards improving conditions for everyone affected.

Another alternative viewpoint could be that the focus on women in the response to COVID-19 perpetuates gender stereotypes and reinforces traditional gender roles. Critics may argue that a more inclusive approach should be taken, emphasizing the importance of shared responsibilities between men and women in both paid and unpaid work. Another alternative perspective could suggest that instead of solely focusing on the negative impacts of COVID-19 on women, opportunities for empowerment and advancement should also be explored. This perspective may argue that the crisis can be a catalyst for positive change, with the potential to challenge and disrupt existing gender inequalities. Some may question the need for gender-inclusive policies and argue that a more neutral approach, considering the needs of all individuals regardless of gender, would be more effective in minimizing the effects of the pandemic. In nutshell, a critic may also argue that the focus on gender impacts overlooks other important factors such as age, class, or geographic location, which may play significant roles in determining the extent of vulnerability and challenges faced by individuals during the pandemic. They may propose a broader analysis that takes into account multiple intersecting factors.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data sources

The study used the 2020 Uganda High-frequency Phone Survey on COVID-19 (UHFS) conducted by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) in June of 2020. This survey was the first round of high-frequency phone surveys of households that were initiated to track the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Ugandan households on a month-to-month basis for one year during the pandemic period. The survey was part of the effort by the World Bank to support countries around the world in data collection to enable the monitoring of the pandemic as it evolved with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The survey is part of the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) Program which is responsible for similar data collection for many countries across the globe. In the first phase of UHFS, a total of 2,257 households out of 2,421 households that were previously interviewed in the 2019/2020 Uganda National Panel Survey (UNPS) were contacted and successfully interviewed accounting for a 93% response rate (UBOS, Citation2020). The goal was to carry out more than 11 rounds of similar interviews as the pandemic evolved. Uganda National Panel Survey (UNPS) being nationally representative data, the HFPS sample had its weights and calibrations calculated based on UNPS frameworks. Mainly for two reasons first; to counteract selection bias and second to mitigate against response bias caused by not interviewing UNPS households without phones and phone numbers respectively.

The first round of data collection upon which this study is based took place for a total of two weeks starting on June 3rd, 2020. Information was gathered on the different dimensions of social and economic interactions under the pandemic. The data collected include Updated Household roaster, Knowledge regarding the spread of COVID-19, Behavior and social distancing, households’ access to services and other necessities, respondent’s employment Information on Agriculture, Income loss Food insecurity experience scale, concerns of the head of the household on COVID-19, Copping strategies and Safety nets UBOS, (Citation2020). The interest of this study will be in the employment sector of the survey.

The main purpose of UHFS was to enable the government of Uganda to monitor the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic and the containment measures associated with it (UBOS-UHFS 2020). The beauty of this kind of survey is that it follows the COVID-19 pandemic as it evolves in a real-time scenario, such information is valuable to health workers and the government’s national COVID-19 task force to design effective policies and standard operating procedures to mitigate the negative impacts of the pandemic.

3.2. Description of the Outcome Variable

The outcome variable is employment status, captured as a dichotomous variable, where those employed took on 1 (FLFP = 1) and unemployed took a zero (FLFP = 0) during the pandemic. Secondly, a change in employment is also studied to account for the impact of the pandemic on labor force participation. Other variables of interest include the sector of employment and revenue fluctuations on businesses to capture the impact on self-account workers.

4. Estimation Strategy

We are interested in analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on the labor market outcomes in Uganda during the pandemic-related containment measures such as lockdowns, with particular attention paid to female labor force participation. This is because women face competing demands on their time both at the workplace and home on child care. To achieve this goal, we estimate the following regression equation based on a probit regression model for economically active women aged 18–54 years. The reduced form is;

(1)

(1)

where,

, represents the outcome variable about female labor force participation for women I during the COVID-19 lockdown,

is an indicator of a working mother engaged in household child care during the lockdown, this includes homeschooling for remote learning pupils and students and child care. Vector

includes both individual and household characteristics that are assumed to also affect the likelihood of participating in the labor market by women. The variables contained in the vector

included age, marital status, presence of a child, household size, education, gender, household income status, residence, religion, other labor market activities during COVID-19, lockdown variables, and jobless variables are all dummy in nature. We assume at any point in time during the pandemic, either mother, father, or both parents are locked down thus we incorporate a dummy for parent’s lockdown donated as

.

Incorporating all the variables in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) above, the following expanded model is estimated in the first phase:

(2)

(2)

where vector

represents partners’ characteristics and

controls for labor participation status before the onset of the pandemic to avoid multi-collinearity between

and household and individuals characteristics,

we control for the date of the interview DOI to capture the intensity of the responses as the pandemic evolves. Economic stress is captured by COVID-19, which was captured by asking whether people thought the outbreak of the pandemic posed an economic threat.

The data were analyzed using STATA Version 14, a descriptive summary for female labor force participation is done controlling for lockdown, and second, we carried out binary analysis using the famous Pearson’s chi-square test this was done purposely to identify variables that have some association with the outcome variable of interest. Significant variables and those deemed to be important in explaining the outcome variable are advanced to the next level for subsequent analysis. Lastly, we fit a probit model at a 5% level of significance. These results and more are reported in the results section below.

5. Results and discussions

From , the survey in wave 1 interviewed a total of 2,255 individuals with women taking on the largest number. Our unit of analysis is the women who made up 28.25% of the total individuals during the pandemic. Further analysis from this point onwards is focused on women in comparison with their male counterparts regarding their participation in the labor markets during the COVID-19 outbreak. More women worked a week before the survey than men at the same time more women did not work as seen from the fourth column of ().

Table 1. Summary of the descriptive statistics.

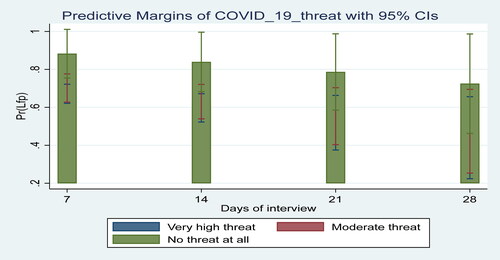

From the plunger plot above, it can be observed that the predicted probability of female labor force participation was highest among those who thought that the pandemic posed no threat to their economic and social welfare, followed by those who thought the COVID-19 risk was moderate and those who reported a very high COVID-19 threat come in a third-place at the pandemic progressed captured here in terms of the days of the interview ().

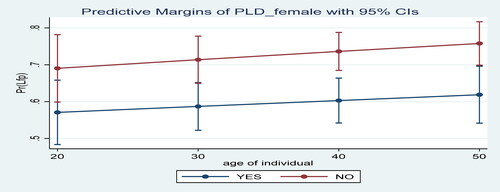

The predicted probability of female labor force participation during lockdown increases with one’s age between those who were locked and those who were not locked during the COVID-19 outbreak. Here locked parents are those who were either unemployed at home or those who were working from home during the lockdown period, similar definitions have been used by Arenas-Arroyo et al., (Citation2020) in a study in Spain.

6. Discussions

We begin by looking at the preliminary results from , where the coefficients are expressed in terms of marginal effects or the percentage points (pp.) change for the women either working or not working during the COVID-19 lockdown. From panel A1, there was a 7.1 percentage point significant increase in the female labor force participation when only females were locked as opposed to a decrease of 13.6 pp for those that did not work for those of the same gender category. On the other hand, 20 percentage points are observed among female workers if only the male partner is locked down as opposed to a decrease of 24.3 pp if both partners are locked down. If we consider the self-reported COVID-19 threat to capture economic or financial anticipated stress, we see a significant decrease in the female labor force participation for both those who thought the pandemic posed a higher and moderate threat at 32.4 pp and 25.3 pp respectively as opposed to those who thought it that it posed no threat at all. Considering those who either own or operate a family business the picture is no different for instance a 13.5 percentage point is observed among women who were either unemployed or working from home.

Table 2. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on female labor force participation.

However, we observe a decrease in female labor market activities if only the male partner is locked. However, their participation again rises by 6.3 pp when both partners are locked, this can be explained by the combined effort of both partners to look after the family, and this result may be against explanations put forward in partner violence-related studies (Arenas-Arroyo et al., Citation2020). Labor market activity still significantly decreased for individuals who operated their businesses and thought that the pandemic outbreak posed a high and moderate threat (33.9 and 35.8pp) respectively, resulting in column 5 of . The decrease in labor activity for those who operated their own business can be explained by the need to cut back on costs and remain afloat during and even after the pandemic since the business environment was unclear when the diseases started, a similar finding is found by Balduzzi et al., (Citation2020) in a study of the impact of the pandemic on Italian firms and business sector in general and a global macroeconomic impact of COVID-19 study by (Fiaschi & Tealdi, Citation2023; Mckibbin & Fernando, Citation2020).

The results of this study’s main specification are captured in (results table), here we disaggregate, the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown and its associated self-reported threat and concern, we also progressively incorporate other control covariates in the model as suggested in the model specification section. Needless to mention we controlled for employment status before COVID-19, the education level of the partner, days of the interview to capture the change in the people’s attitudes and perceptions towards the pandemic as it progressed, marital status, age of the women, receipt of assistance from any source, ownership of a business, homeschooling to capture the demands on the mother’s time allocation and behavioral change (e.g. social distancing, hand washing and wearing of masks) about the pandemic. Unlike other pandemic outbreaks like HIV/AIDS, Spanish influenza, Ebola, and others, COVID-19 demands immediate individual change and life adjustments for the successful fight against it.

Table 3. The impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Female Labor Force Participation: with subgroups.

has a total of eight models from columns (2) to (9), here analysis is done for women with children, their age categories, and their level of education, all of which critically not only affect female labor force participation but also the outcomes of the labor market such as wages and other earnings.

In columns (2) and (3), we analyze the impact of the presence of children on the female labor force participation, we see that the impact is highest when only the female partner is locked down, its impact ranges from as low as 47.1 to 51.7 pp, the COVID-19 threat causes an even greater effect on female labor market activity of a decrease of 18.4 and an increase of 62.7 pp for those with and without children respectively, clearly female labor force activity significantly reduces for those with children, this can be explained by multiple demands on women’s time during the lockdown such as engaging in household chores and children homeschooling. Conversely, the impact of age on female labor force participation is highest when female parents are locked and this effect is significant for ages 18–30, 31–50, and 51 plus as seen in . Concerning women’s education level, higher impacts are reported when only the male parent is locked down, these effects range from 4.1, 62.7, and 72.2 pp for women with No schooling, primary and post-primary, here post-primary includes, vocational certificates, diplomas, degrees and higher.

Whereas the impact of business ownership or being own account worker is significantly high across all the estimated models among the controlled covariates (i.e. presence of children, age of the women, and educational level) for female labor force participation, the highest impacts can be seen among those aged 51 and above where effects increased by 83.8 pp. considering the impact of the presence of children, the impacts of owning a business on female labor force participation range from a high of 51.3 to a low of 8 pp for women with and without children respectively. Considering education, the impact of owning a business on female labor force participation is highest among those in post-primary and primary education respectively (72.2 & 62.9 pp). However, the impact decreases with No schooling. The impact of behavioral change (handwashing) on female labor force participation is highest among women with children compared to those with no children. This effect is significant at a 1% level of significance in columns (2) and (3) in case of the presence of children, columns (4–6) for age, and (7) to (9) for the education level of the women respectively. It is not surprising, however, that those children had to adjust quickly to the SOPs in response to the pandemic outbreak not only to safeguard their families but also a requirement for most employers and governments for workers to participate in the labor markets. For the age, the impact is highest among 31–50-year-olds which is the most age category, but also those aged below 30 years suffer unprecedented levels of unemployment in Uganda.

Last but not least, we consider the impact of the marital status of the women on FLFP we see significantly greater effects in column (2) for women in other categories of marital status (separated, widowed, and divorced) with children. However, this significantly reduces among married women with no children by (78.6pp). Highly educated women that are either married or separated/widowed/divorced significantly participate in the labor market and these effects increase FLFP by (62.3 & 75.3pp).

Lastly, we move to test the impact of the COVID-19 government relief program on the female labor force participation during the lockdown, this is done by including a variable Received government assistance among the regression covariates as captured in the UHFS questionnaire. We see an increase in FLFP among women with children by 18.2pp compared to a decrease of 7.4pp among those with no children. Taking receipt of government as a measure of public health compliance with SOPs, some level of compliance can be reported among women with children and those in post-primary education as shown in columns (3) and (9) respectively where FLFP reduces.

7. Conclusions

Female labor force participation is of national and global concern with the potential to quickly evolve into a human rights violation and economic crisis for women. The motivation for studying women’s labor market activities is that women’s work does not end in workplaces, it extends even to their homes (in terms of household chores and homeschooling of their children). This situation we anticipated was worsened by the lockdown needless to mention the potential for domestic violence due to forced coexistence. Using the first round of a monthly COVID-19 pandemic-evolving data set, our results indicate bigger impacts of the pandemic outbreak on female labor participation, the prevalence of female labor market activities drastically declines by 17% in the first months following strict shut down of the economy in Uganda. This situation is particularly worrying given the fact most women in the country not only live hand to mouth but also are mostly employed in the informal sector. Thus it is important to incorporate in the analysis even unreported events. We also observe that lockdown and the related COVID-19 threat are important facts that explain female labor market activities. However, lockdown had some unintended consequences for instance income loss, an increase in domestic violence, theft, and other anti-social behavior, political unrest in worst cases death. Conceivably the only sanguine finding from our study is that in extreme cases of lockdown i.e. when both partners are locked down female labor markets activities drastically reduce across all models in . The reason for such a trend is unclear and thus leaves a vacuum to pose questions for future research in the case of other pandemics.

Inclusion and the easing of lockdown measures have not translated into a fast increase in female labor market activities. Thus deliberate government effort should be devoted towards woman who has children, below the age of 30 and with no schooling, since we observe particularly greater impacts among them. Special attention should be given to those who have lost their jobs or source of livelihood and those who were previously unemployed since the outbreak has hit the hardest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study sought approval from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) being the custodians of the data set used for analysis. Secondly, the data is approved for public use and made publically available by the third party which is the World Bank (WB) in this case. In addition, we sought approval from The Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (NCST) for Ethical consideration, and a go-head was given since the data was made public by a third party.

Consent for publication

‘Not applicable’ the data about persons was made anonymous there were no names that could pertain to the persons for their traceability. There is no personal identification information in the dataset used and thus we could not trace people for their consent.

Authors’ contributions

Mukoki James: Carried out the literature review and conceptualized the idea under study, he also formulated the motivation for the study, and wrote the concept that was funded. Candia Andabati: Carried out the data collection and preliminary data explorations and other study-related information gathering, did data cleaning, editing, and other manipulations and analysis, he also carried out interpretation of results and other write-ups. Musoke Edward: carried out proofreading and further formatting and editing of the manuscript. Mukisa Ibrahim: conducted the overall quality assurance and guided the entire writing process.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial contribution from the College of Business and Management Science (COBAMS) of Makerere University and the Support and advice of Prof B. Yawe and also members of staff of the School of Statistics and Ph.D. in Economics class of 2019. Latly we also want to acknowledge the efforts of the following people Ssebulime Kurayishi who works as a senior labor Economist at the National Planning Authority (NPA) in Uganda, and he is currently a Ph.D. student of Economics from the School of Economics of Makerere University, He has a host of experience in the areas of labor economics, Tumuramye Nicholas for his insightful contributions towards this work. Lastly I also acknowledge the enouragement of my dear wife Leilah and my beautiful daughter princess Imani.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of data and materials

Data about the conclusions made in this study is available and it was downloaded from the World Bank website. Other additional datasets that support our results can be availed at the request of the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James Mukoki

James Mukoki is a Ph.D. candidate (Economics) at Makerere University in Uganda. He holds a Master of Arts in Economics (MA) from the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He has over ten years of research experience in developing countries. He holds a diploma in Sterile Processing & Healthcare Management from Niles College, Burlingame, California, USA. His research interest lies in macroeconomics, development, and applied economics, Labor economics, and Public Health. He is a 2021–2022 CEGA Research fellow at University of California, Berkeley, where he gained a lot of experience in the design of field experiments and Randomized Control trials (RCTs) studies.

Douglas Candia Andabati

Douglas Candia Andabati, is an Assistant Lecturer at the School of Statistics of Makerere University and he is also currently a Ph.D. student in Social Statistics from the University of Nairobi, he is an expert in Biostatistics and he is a well-researched fellow. Lastly we want to acknowledge the expert knowledge given by Kurayish Sebulime who is an expert in labor Economics and a seasoned Researcher and National Planner, and Nicholas Tumulamye who is a researcher and consultant in Uganda.

Ibrahim Mukisa

Ibrahim Mukisa (Ph.D.) is a seasoned academician researcher, Economist and coordinator of graduate programs at the School of Economics at Makerere University. His research has made a significant contribution to the scholarly body of knowledge both in Africa and internationally.

Edward Musoke

Edward Musoke, currently works as an assistant lecturer at Makerere University, he carried out proofreading and further formatting and editing of the manuscript.

References

- Aldila, D., Khoshnaw, S. H. A., Safitri, E., Anwar, Y. R., Bakry, A. R. Q., Samiadji, B. M., Anugerah, D. A., Gh, M. F. A., Ayulani, I. D., & Salim, S. N. (2020). A mathematical study on the spread of COVID-19 considering social distancing and rapid assessment: The case of Jakarta, Indonesia. Chaos, Solitons, and Fractals, 139, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110042

- Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). This time it’s different: The role of women’s employment in a pandemic recession. In IZA Journal of European Labor Studies (Issue 13562).

- Appiah, E. N. (2018). Female labor force participation and economic growth in developing countries. Global Journal of Human-Social Science, 18(2), 175–17. http://wol.iza.org/articles/female-labor-force-participation-in-developing-countries.

- Arenas-Arroyo, E., Fernandez-Kranz, D., & Nollenberger, N. (2020). Discussion Paper Series can’t leave you now ! Intimate partner violence under forced coexistence and economic uncertainty. Can’t leave you now ! Intimate Partner Violence under Forced Coexistence and Economic Uncertainty. 13570

- Balduzzi, P., Brancati, E., Brianti, M., & Schiantarelli, F. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. The economic effects of COVID-19 and credit constraints: Evidence from Italian firms’ expectations and plans. The Economic Effects of COVID-19 and Credit Constraints: Evidence from Italian Firms’ Expectations and Plans. 13629.

- Balleer, A., Link, S., Menkhoff, M., & Zorn, P. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. Demand or supply ? Price Adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic demand or supply ? Price Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 13568.

- Bluedorn, J., Caselli, F., Hansen, N.-J., & Tavares, M. M. (2021). Covid economics, vetted and real-time papers. In G. I. G. Wyplosz, & C. Charles (Ed.), Covid economics (No. 76; 76th ed., Issue 9, p. 166). https://portal.cepr.org/call-papers- covid-economics.

- Choudhry, M. T., & Elhorst, P. (2018). Female labour force participation and economic development. International Journal of Manpower, 39(7), 896–912. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2017-0045

- Corr, A. (2022). How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected married female labor force participation? [Mount Holyoke College South]. https://ida.mtholyoke.edu/handle/10166/6360%0Ahttps://ida.mtholyoke.edu/bitstream/handle/10166/6360/Corr_SeniorThesis_LibSubmission.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Corsi, M., & Ilkkaracan, I. (2022). COVID-19, Gender and Labour. (No. 1012; Issue 1012).

- Donovan, S. A., & Labonte, M. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: Labor Market Implications for Women. https://crsreports.congress.gov.

- Fiaschi, D., & Tealdi, C. (2023). The attachment of adult women to the Italian labour market in the shadow of COVID-19. Labour Economics, 83(vember 2022), 102402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2023.102402

- Gandhi, D. (2020). Figure of the week: Economic gains from increasing female labor force participation in Africa. | Brookings. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/figure-of-the-week-economic-gains-from-increasing-female-labor-force-participation-in-africa/.

- Gaudecker, H.-M v., Holler, R., Janys, L., Sifinger, B., & Zimpelmann, C. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. Labour supply during lockdown and a “New Normal”: The Case of the Netherlands. Labour Supply during Lockdown and a “New Normal”: The Case of the Netherlands. 13623.

- Goff, S., Ifcher, J., Zarghamee, H., Reents, A., & Wade, P. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on government- and Market-Attitudes. 13622.

- Goldin, C. (2022). Understanding the economic impact of COVID-19 on women. In Bpea Sp22, 2022(1), 65–139. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2022.0019

- Jaumotte, F. (2003). Labour force participation of women: Empirical evidence on the role of policy and other determinants in OECD Countries. In OECD Working Paper Series (No. 37; 2003/2, Vol. 37, Issue 2).

- Jingyi, L., Lim, B., Hanim Pazim, K., & Furuoka, F. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the labour market in ASEAN countries. AEI Insights, 7(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.37353/aei-insights.vol7.issue1.5

- Kiani, A. Q. (2021). Determinants of female labor force participation. ASEAN Marketing Journal, 1(2). 86. https://doi.org/10.21002/amj.v1i2.1986

- Klasen, S., Le, T. U. T. H. I. N. G. O. C., Pieters, J., & Santos Silva, M. (2020). What drives female labour force participation? Comparable micro-level evidence from eight developing and emerging economies. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(3), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1790533

- Lim, K., & Zabek, M. (2021). Women’s labor force exits during COVID-19: Differences by motherhood, race, and ethnicity. In Finance and economics discussion series, 2021(066), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2021.067

- Lone, S. A., & Ahmad, A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic–an African perspective. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 9(1), 1300–1308. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1775132

- Mckibbin, W., & Fernando, R. (2020). The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19 : March. 1–43.

- MoFPED. (2020). BMAU Briefing Paper (3/20) MAY 2020 The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the urban poor in Uganda BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (3/20). (Issue May).

- MOH. (2020). Definition of Covid FAQ – COVID-19 _ Ministry of Health.

- Mwabu, G. (2007). Health economics for low-income. Handbook of Development Economics, 4, 3305–3374. http://ideas.repec.org/h/eee/devchp/5-53.html.

- Nattabi, A. K., Mbowa, S., Guloba, M., & Kasirye, I. (2020). Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment prospects for Uganda’s youth in the Middle East. 124, October 2020, 17–20.

- Psacharopoulos, G., Collis, V., Patrinos, H. A., & Vegas, E. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. Lost wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures Lost Wages : The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures. 13641.

- Rahmadhani, P., Vaz, F., & Affiat, R. A. (2021). COVID-19 Crisis and Women in Asia Economic impacts and policy responses COVID.

- Risse, L., & Jackson, A. (2021). A gender lens on the workforce impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. In Australian Journal of Labour Economics (VOL. 24, Issue 2).

- Sarker, M. R. (2021). Labor market and unpaid works implications of COVID-19 for Bangladeshi women. Gender, Work, and Organization, 28(Suppl 2), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12587

- Shin, J., Kim, S., & Koh, K. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. Economic impact of targeted government responses to COVID-19: Evidence from the First Large-scale Cluster in Seoul Jinwook Shin Economic Impact of Targeted Government Responses to COVID-19: Evidence from the First Large-scale Clu. 13575.

- Ssonko, G. W. (2020). Central Banks, Consumer Protection, and COVID- 19 in Uganda (No. 01/2021, Issue 29). https://www.bou.or.ug/bou/bouwebsite/Statistics/Statistics.html.

- Tani, M., Cheng, Z., Mendolia, S., Paloyo, A. R., & Savage, D. (2020). Discussion Paper Series. Working parents, financial insecurity, and child-care: Mental health in the time of working parents, financial insecurity, and child-care: Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19. 13588.

- UBOS-Abstract. (2021). Uganda bureau of statistics 2021 statistical abstract. Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

- UBOS. (2020). Uganda High-Frequency Phone Survey on COVID-19 Round One (Issue June). https://www.ubos.org/publications/statistical/.

- Utter, R. I. (2021). Exploring the labour patterns of women and mothers through the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of school closures and a new kind of recession (Issue May). University of California.

- Verick, S. (2018). Female labor force participation and development. IZA World of Labor 2(Issue December), 87. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.87.v2

- Wemesa, R., Wagima, C., Bakaki, I., & Turyareeba, D. (2020). The economic impact of the lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic on low income households of the five Divisions of Kampala District in Uganda. Open Journal of Business and Management, 08(04), 1560–1566. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2020.84099

- Winkler, A. E. (2022). World of Labor Women’s labor force participation. IZA World of Labor 2(Issue August), 289. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.289.v2

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Archived : WHO Timeline -. Archived: WHO Timeline – COVID-19 Archived.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). COVID-19 Weekly Situation Report on Uganda. In World Health Organization (WHO) (Vol. 43, Issue October). https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/whe/coronavirus19/sear-weekly-reports/weekly-situation-report-week-37.pdf?sfvrsn=ac89cd23_2.

- Yang, Y., Ghazanchyan, M., Granados-Ibarra, S., & Canavire-Bacarreza, G. (2024). Employment gender gaps during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Latin America. IMF Working Papers, 2024(012), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400263248.001