Abstract

This study investigates the impact of digital capability (DC) on digital business transformation (DBT), and its effect on small business performance (BP). This study adopts a quantitative approach. The theoretical framework uses knowledge-based view (KBV) and dynamic capability theories. This study empirically examines the direct relationship between DT and DBT in small business performance (financial, flexibility, and quality performance). This study involved 330 small businesses in East Java, Indonesia, using a convenience sampling technique. This hypothesis was tested using structural equation modeling. The findings showed a significant effect of DC on DBT and BP, DBT, and BP. Thus, the results provide evidence that DBT plays a mediating role between DC and BP. This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, empirical evidence supports the KBV and dynamic capability theories that knowledge is the most valuable asset in the digital age. Second, this study significantly extends the relevant literature by highlighting the relationship between DC, DBT, and BP. Finally, this study proposes a multiple-dimension small business performance model that uses three dimensions (financial, flexibility, and quality) as the determinant factors of DC and DBT in the SMEs sector.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The prevalence of digital disruptions in business has intensified significantly with the advent of COVID-19 (Pfister & Lehmann, Citation2023). This global outbreak also forces entrepreneurs to be more flexible and adaptive and accelerates organizational change based on new market behavior, from conventional to digital (Soto-Acosta, Citation2020). Moreover, entrepreneurs must be able to follow technological advances (Shafi et al., Citation2020), create innovations (Thukral, Citation2021), and adapt to consumer behavior changes (Fauzi & Sheng, Citation2022). Only businesses that have successfully transitioned to digital operations are likely to survive (Zapata-Cantu et al., Citation2023). Moreover, adapting new digital technology can improve product and process innovation (Ardito et al., Citation2021), significantly increase efficiency and effectiveness, and play a pivotal role in enhancing short- and long-term competitive advantages in the digital era (Neumeyer et al., Citation2021; Neumeyer & Liu, Citation2021).

The findings of Kamar et al. (Citation2022), Ullah et al. (Citation2021), and Wang et al. (Citation2022) show that Digital Capability significantly influences business performance. Khin and Ho (Citation2019) also found that digital competence significantly affects digital innovation development and can gradually and continuously enhance business performance. The two key successes of digital competence are the ability to manage information well and the flexibility of the digital infrastructure (Levallet & Chan, Citation2018). This means that digital capability encompasses more than just the knowledge of digital tools and platforms. It also includes proficiency in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills; specialized knowledge regarding digitalization; and a mindset that encompasses legal, ethical, privacy, and security aspects. Additionally, digital capability involves understanding the role of ICT in society and maintaining a balanced approach toward technology (Janssen et al., Citation2013). Moreover, a digital mindset is a fundamental factor in formulating a digital strategy (Solberg et al., Citation2020). From a digital transformation perspective, digital capabilities are critical in encouraging sustainability in business (Annarelli et al., Citation2021). This means that digital capability is essential for digital business transformation. Digital transformation is believed to facilitate the work of individuals and organizations more effectively and improve business performance when companies can optimize digital tools, such as artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things (Hirvonen & Majuri, Citation2020; Kahrović & Avdović, Citation2023).

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), one of the business entities most affected by COVID-19, necessitate more orientation in acquiring digital competency and technology adaptability (Neumeyer & Liu, Citation2021). SMEs actors must build greater adaptability through digitization (Bai et al., Citation2021). In addition, Pfister and Lehmann (Citation2023) MSMEs must possess general knowledge of effective technology use. However, many MSMEs must quickly and effectively switch from old to new technology, which often struggle to utilize technology because of their limited digital capabilities (Erlanitasari et al., Citation2020). A significant barrier for many MSMEs to embrace new technologies is the scarcity of resources, expertise, dedication, and comprehension of digital prospects (Rowan & Galanakis, Citation2020). Meanwhile, the basic digital competence to use many technologies is crucial in facilitating the digital transformation (Bai et al., Citation2021). Collective knowledge, talent, skills, and characteristics–referred to as human resources at the unit level–can improve business performance (Kafetzopoulos, Citation2022). A previous study showed that SMEs’ digital capabilities have a significant impact on their business performance (Rupeika-Apoga et al., Citation2022) and digital transformation (Ullah et al., Citation2021). However, previous research (Heredia et al., Citation2022) indicates no significant correlation between digital capabilities and business performance. A survey (Yasin et al., Citation2022) found that SMEs’ digital transformation did not significantly impact their business performance. In addition, there is a need for more in-depth research to address the digital challenges facing SMEs, especially those focusing on digital capabilities (González-Varona et al., Citation2021). This study fills this gap by investigating how SMEs’ digital capabilities affect digital business transformation and small business performance, especially in Indonesia’s context.

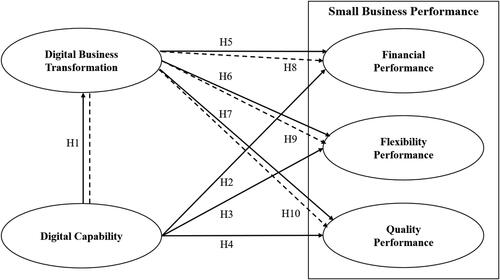

MSMEs owners in Indonesia must improve their digital competence to enhance business performance (Priyono et al., Citation2020) and achieve a competitive advantage by optimizing information technology literacy and capabilities (Anatan, Citation2023; Yusuf et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the OECD report (OECD/ERIA, Citation2018) revealed that Indonesian MSMEs lagged behind Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand in terms of competitiveness at the ASEAN level. Specifically, there is a need for improvement in productivity, technology, and innovation. SMEs can survive and become more competitive in the disruption era by developing new competencies, improving their expertise, and adopting new technologies (Bai et al., Citation2021). Therefore, this study aims to analyze the influence of digital capability on SMEs digital business transformation and its effect on efforts to improve business performance. The main theoretical perspectives used in this study are the knowledge-based view (KBV) and dynamic capability theory (DCT), which are relevant for exploring SMEs performance with high dynamism (Bai et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Cooper et al., Citation2023). illustrates the conceptual model of this study.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Knowledge-based view

It is widely accepted that the knowledge-based view (KBV) of firms is a recent elaboration of the resource-based view (RBV). The competitive paradigm has shifted from resource-based competitiveness to knowledge-based competitiveness, so knowledge is crucial for determining how well an organization performs (Spender, Citation1994). The KBV emphasizes that knowledge is an essential firm resource for creating value (Grant, Citation1996). This means that competitive advantage comes from physical (tangible) and non-physical (intangible) resources, such as knowledge, information, and technology, which are essential in providing long-term advantages. Knowledge is the most precious strategic asset with the potential to sustain a competitive advantage and achieve success (AlKoliby et al., Citation2023) as well as to create long-term competitive advantage and improve performance (Heenkenda et al., Citation2022; Kulathunga et al., Citation2020; Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, Citation2018; Taghizadeh et al., Citation2020). Moreover, Cooper et al. (Citation2023) state that KBV is one of the appropriate theories used to analyze the determinants of organizational performance in emerging markets.

2.2. Dynamic capability

Teece and Pisano (Citation1994) developed dynamic capabilities theory (DTC) to describe organizational capabilities in creating, changing, absorbing, and remaining competitive in a rapidly changing environment. Teece and Pisano (Citation1994) argued that there needs to be a paradigm that explains how the acquisition and maintenance of competitive advantage occurs. Dynamic capabilities are made up of two keywords, each having a different meaning: ‘dynamic’ indicates the ability to upgrade competencies to continually suit changing business environments; responsive innovation is required when time is crucial, the pace of technological change is quick, and the future of business competition is complicated to predict. Meanwhile, ‘capability’ asserts the essential role in aligning, integrating, and reconfiguring functional resources and business skills to adapt to the business environment changes. Practically, Teece et al. (Citation1997) define dynamic capability as a competency or ability that enables a company to produce new products or services to respond to the dynamic environment.

Thus, in the company context, dynamic capabilities are a company’s innovative capabilities in dealing with rapidly changing environments, solving potential problems, and making timely market-oriented decisions by adjusting internal resources and competencies (Teece, Citation2007). On the other hand, from the information systems perspective, dynamic capabilities comprise capacity measurements: sensing, seizing, and transforming. Sensing capability refers to the recognition, cultivation, collaboration, exploration, and evaluation of technical opportunities relevant to market demand. Seizing capacity refers to efficiently utilizing resources to meet demands and taking advantage of opportunities from observed activities. The transforming capacity encompasses updating asset modifications, synergistic changes, realignments, and redeployments (Wang et al., Citation2022; Yeow et al., Citation2018). Wang et al. (Citation2022) claimed that dynamic capability in the digital transformation context consists of three aspects: digital sensing, seizing, and transformation capabilities. Furthermore, the DCT is helpful in explaining how companies adapt to swift technological and environmental changes (Pieroni et al., Citation2019) and support SMEs in enhancing their competitive edge (Bai et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, this study uses the DCT as its theoretical foundation.

2.3. Business performance

Performance concerns the capability of generating future results and is meaningful only when used by a decision-maker. The concept of performance involves three steps: outcomes, processes, and foundations (Neely, Citation2004). The outcomes are separated into two types: conventional perspectives (e.g. accounting income) and non-conventional perspectives (e.g. social welfare, labor, and social climate). The process involves innovation, working conditions, price, and others. The foundations are competence, awareness of brand value, maintenance policy, existing negotiation structures, partnerships with customers and suppliers, and organizational responsibility structure (Neely, Citation2004). Therefore, performance is a complex concept, and the output of performance is determined by its process and inputs.

The most popular performance measurement system for evaluating business performance is the balanced scorecard, which asserts a balance between financial and nonfinancial perspectives to gain competitive advantages (Kaplan & Norton, Citation1991). In the context of SMEs, many scholars argue that the measurement of SMEs’ business performance is appropriate for various classifications (Ferreira et al., Citation2020; Vrontis et al., Citation2022). Many scholars have suggested that sub-aspects of business performance, mainly financial, non-financial performance, innovation, and quality, can be utilized to measure a company’s overall performance (Kafetzopoulos, Citation2022). Furthermore, Alsufyani and Gill (Citation2022) stated that there are six dimensions to measure adaptive organizational performance: Competitiveness, Financial, Quality of Service, Flexibility, Resource Utilization, and Innovation. Moreover, SMEs business performance can also be measured from financial and non-financial perspectives (Hudson et al., Citation2001). Financial performance measurement, such as profitability, market share, product cost reduction, etc. Furthermore, non-financial performance measurement is reflected in quality (e.g. product and process quality), flexibility (e.g. volume flexibility), time (e.g. delivery time), customer satisfaction (e.g. complaint management), and human resources (e.g. employee welfare) performance.

2.4. Conceptual framework and hypothesis development

2.4.1. Digital capability and digital business transformation

The role of digital capability in driving the success of a company’s digital transformation, including SMEs, can be explained using the dynamic capability theory and a knowledge-based view. Digital capability is a dynamic skill that an organization possesses to generate innovative products and business processes and effectively adapt to changes in the business environment (Kerti Yasa et al., Citation2019; Khin & Ho, Citation2019). The dynamic capability theory suggests that a company’s capacity to adjust to an unpredictable environment increases its business resilience to achieve a competitive advantage.

A previous study has stated that digital capabilities can enhance digital transformation (Cetindamar et al., Citation2024; Kulathunga et al., Citation2020; Okundaye et al., Citation2019; Priyono et al., Citation2020; Zhang-Zhang et al., Citation2022). Therefore, based on KBV theory, Dynamic Capability Theory, and previous research regarding digital capabilities as an antecedent factor in accelerating the accomplishment of digital transformation, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Digital capability has a significant effect on digital business transformation.

2.4.2. Digital capability and small business performance

This study considers digital capability as a form of dynamic capability needed for an organization’s success in improving its business performance in an emerging market. Knowledge is a crucial factor in creating digital capabilities as intangible assets. Knowledge owned by a company is the main determinant of its sustainable competitive advantage and excellent performance (Ullah et al., Citation2021). In this research, digital capabilities are assumed to play a strategic role in SMEs achieving successful performance. This means that digital capabilities are the main resources for SMEs to achieve superior performance and a source of competitive advantage. The knowledge-based view theory assumes that all forms of knowledge are resources for improving competitive advantage (Grant, Citation1996).

Digital Capability, a knowledge resource, is an antecedent factor for enhancing business performance (Chen et al., Citation2023; Khin & Ho, Citation2019). Several studies have also shown that digital capability can affect the speed of accelerating business performance (González-Varona et al., Citation2021; Kafetzopoulos, Citation2022; Ullah et al., Citation2021). Specifically, a study by Nasiri et al. (Citation2020) and Wang et al. (Citation2022) showed that digital capability affects Financial Performance. Moreover, digital capability influences flexibility (Lee et al., Citation2022) and quality performance (Saryatmo & Sukhotu, Citation2021; Sharma & Joshi, Citation2023). Therefore, we developed the following hypothesis:

H2: Digital capability has a significant effect on financial performance.

H3: Digital capability has a significant effect on flexibility performance.

H4: Digital capability has a significant effect on quality performance.

2.4.3. Digital business transformation and small business performance

Digital business transformation is a broad, deep, and significant technological change; as an illustration, how the company gains market share not only depending on physical shops but also by expanding to a digital marketplace (Pfister & Lehmann, Citation2023). It encompasses continuous endeavors involving numerous interconnected stakeholders (Solberg et al., Citation2020). According to Galindo-Martín et al. (Citation2019), digital transformation refers to the necessary conveyance of business activities to incorporate digital technology, such as cloud computing and office software applications. Li et al. (Citation2018) described digital transformation as the influence of information technology (IT) on the structure, processes, and flow of information within an organization. The process is perpetual and iterative as information technology continues to evolve. Companies must undergo regular changes in their reactions to technological advancements. Thus, Yu et al. (Citation2022) it is clear that the motivation for digital transformation is based on the optimism that new digital solutions have a significant potential to enhance performance and gain a competitive advantage.

This impact can be seen from four perspectives: (1) cost-saving channels: the digitalization of enterprises expedites the transmission of information, knowledge, labor, and other resources; (2) advanced technology application: the digitalization process can enhance decision-making quality because of their ability to perform environmental scanning with diverse information data and make massive calculations properly; (3) resource allocation efficiency: digitization can overcome information asymmetry and allow companies to manage fragmented resources; and (4) diversified innovative ways: digitalization can encourage companies to create innovation as a critical factor in gaining business performance (Li et al., Citation2023). In an uncertain environment, the dynamic capability is useful for explaining how firms respond to technological and environmental changes (Pieroni et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, the relationship between digital business transformation and business performance is closely related to how organizations manage their knowledge in the context of digital technology change. This relationship can be explained through knowledge-based view (KBV) theory, a theoretical approach to understanding how firms might enhance their business performance by implementing knowledge management strategies (Grant, Citation1996). Additionally, several earlier studies show that digital business transformation significantly influences business performance (Ganawati et al., Citation2021; Mubarak et al., Citation2019). In particular, Teng et al. (Citation2022) claim that digital business transformation impacts financial performance. Digital business transformation significantly affects flexibility performance (Huo et al., Citation2021; Rossini et al., Citation2021) and quality performance (Alathamneh & Al-Hawary, Citation2023; Saryatmo & Sukhotu, Citation2021). This confirms the knowledge-based view (KBV) theory, in which a company’s ability to optimize its knowledge positively impacts company competitiveness (Spender, Citation1994). Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5: Digital business transformation has a significant effect on financial performance.

H6: Digital business transformation has a significant effect on flexibility performance.

H7: Digital business transformation has a significant effect on quality performance.

H8: Digital business transformation mediates the relationship between digital capability and financial performance.

H9: Digital business transformation mediates the relationship between digital capability and flexibility performance.

H10: Digital business transformation mediates the relationship between digital capability and quality performance.

3. Research method

This study uses a quantitative approach. The field study was conducted in Indonesia, specifically in the East Java region, particularly in the cities of Malang, Batu, and Malang Regency, called Greater Malang. Greater Malang is one of the areas with the rapid growth of small industries that contribute to increasing the welfare of the people in East Java. Moreover, the growth of small industries has strengthened the position of these three cities as industrial cities.

This research involved 3 (three) leading sectors of Greater Malang small business as research objects: culinary (food and beverage), craft, and fashion. Besides, these catagories are primary industries that employ the largest workers in Greater Malang. The respondents’ criteria refer to the definition of a Small Business by the number of employees (5–19) used by BPS-Statistics Indonesia (OECD/ERIA, Citation2018). The sample size of this study was 330. Convenience sampling was used. Data were collected by distributing questionnaires to the respondents. The questionnaire was adopted from previous studies in English and translated into Indonesian using a back translation technique to control questionnaire quality properly. Furthermore, partial questionnaires were distributed online using Google Forms (139 respondents), followed by the offline method (191 respondents). For each survey item, we used a five-point Likert scale of ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘neutral’, ‘agree’, and ‘strongly agree’ (Taherdoost, Citation2019). Moreover, this study used Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis with SmartPLS software to assess the measurement and structural model.

3.1. Research instrument

Referring to several previous studies, scale measurements were applied to assess the constructs of this study, with modifications. The antecedent of Digital Capability was measured using a seven-item scale adapted from (Baker et al., Citation2015).

Digital devices (e.g. smartphones and computers) were used to support our business activities.

We use various software and digital applications to support our business activities.

We can use data or information on the Internet to support our businesses (e.g. Google Analytics).

We can use digital platforms to support and conduct business activities (e.g. using social media as an advertising tool and customer satisfaction surveys).

We use an e-commerce platform to maximize sales

We can create and develop our own websites or digital platforms.

We can update our own website or digital platform (e.g. promotion content).

As for the mediating variable, Digital Business Transformation was assessed by adopting a five-item scale, as applied by Khin and Ho (Citation2019), Proksch et al. (Citation2021), and Zhou and Wu (Citation2010).

We encourage business functions (marketing, production, distribution, and staffing) to use a digital approach.

We have a top priority planned to change our organization continuously based on digitalization.

We always follow the newest technological developments to improve our business functions/activities.

We always try to optimize e-commerce for sales channel

We are always looking for the newest (trending or viral) information on the Internet or digital media platforms to keep our businesses competitive.

Business performance outcomes were operationalized based on three dimensions: financial performance, flexibility performance, and quality performance (Hudson et al., Citation2001). The item scales developed in a previous study are as follows:

Financial Performance (Bourlakis et al., Citation2014; Hussain & Papastathopoulos, Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2018)

Our products/services sales increased compared to last year

Our profit increased compared to last year

We are always on time to pay all our obligations (e.g. wages/salaries, banking loans, debts to suppliers, etc.)

We have been able to manage our finances properly and adequately.

We have been able to divide and use our finances according to budget planning, such as production costs, distribution costs, and employee salaries.

Flexibility Performance (Bourlakis et al., Citation2014; Huo et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2018)

We can accept orders from consumers in large quantities.

We can accept orders with various types of products according to consumer wishes.

We can design and develop new products using the newest technology.

We can distribute products in a fast time.

Quality Performance (Bourlakis et al., Citation2014; Gao et al., Citation2023; Liu et al., Citation2018; Saryatmo & Sukhotu, Citation2021)

We have a straightforward program to improve our employee competency.

We have guidelines for maintaining and improving our product/service quality.

We have good relationships with our suppliers and consumers.

We always pay attention to our employee’s welfare.

4. Model analysis

4.1. Characteristics of respondents

There are 330 small business actors in Malang Raya (Great Malang) who acted as respondents in this study. Most of the respondents were female (56%; n = 182). The major challenge for female SMEs owners is their ability to quickly adjust to the dynamic environment. In developing countries, women entrepreneurs have more potential to succeed in their businesses if they can fulfill internal entrepreneurial behavior requirements, namely good motivation, risk-taking, and self-confidence, and consider economic and sociocultural factors as external factors (Khan et al., Citation2021). A total of 190 small businesses were established between 2011 and 2019, dominated by 209 respondents from the culinary (food and beverage) business sector. Based on descriptive data, as many as 76% of the 184 respondents used e-commerce between 2016 and 2020. The respondents’ characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Respondent’s characteristics.

4.2. Measurement model result

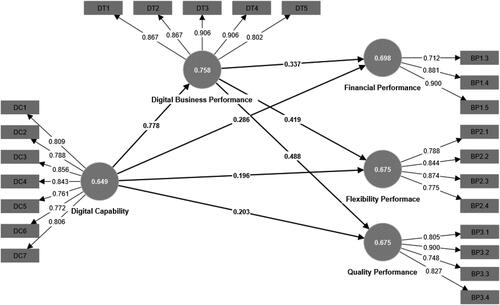

An examination of the feasibility of the model is an assessment of its appropriateness using research data (). Hair et al. (Citation2019) state that the study uses reflective model measurement, there are prevail several provisions, namely, reflective indicators/items loadings factor value ≥0.708, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability are used to describe the internal consistency reliability with a value ≥0.7 to ≤0.95 to avoid indicator or item redundancy, which would compromise content validity. Moreover, convergent validity determines the extent to which a given construct’s size is positively correlated with alternative measures. Hair et al. (Citation2019) state convergent validity was assessed using Average Variance Extracted (AVE). A model is considered to have good convergent validity if its AVE value is equal to or above 0.5 (AVE ≥ 0.5).

Table 2. Evaluation of the measurement model.

The next step in the measurement model test was the variance inflation factor (VIF). VIF was used to assess the collinearity of the indicators/items. A VIF score of five or higher indicates significant collinearity problems between the indicators of the measured constructs. The VIF score can be accepted when the VIF is ≥3–5 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Based on VIF calculations, the VIF scores of BP1 = 6.34 and BP2 = 6.28 must be eliminated from the research model because a VIF score >5. This refers to indications of collinearity and potential bias problems. BP1 is our products/services sales increased compared to last year, and BP2 is our profit increased compared to last year.

The last step is to evaluate discriminant validity, which measures the degree to which a construct is empirically different from other constructs within the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2019). The measurement of discriminant validity was determined by following the Fornell-Larcker criteria, which states that the square root of the AVE for a construct must exceed the correlation between that construct and any other construct (Kwong-Kay Wong, Citation2019). indicates that the study fulfills all of the Fornell-Larcker criteria.

Table 3. Fornell-Lacker criterion to discriminant validity of the model.

Discriminant validity was also assessed using the correlations’ heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio, which has a lower threshold value below 0.85 or 0.90 (Hair et al., Citation2019). demonstrates that each variable possesses an HTMT value below 0.9, indicating that all the variables in this study satisfy the HTMT criteria.

Table 4. Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) criterion to discriminant validity of the model.

Moreover, cross-loadings can be used as one of the discriminant validities in which the loadings of an indicator on its specified latent variable should surpass those of all other latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2019). shows that the cross-loading value for each item met these criteria.

Table 5. Cross loading criterion to discriminant validity of the model.

4.3. Structural model result

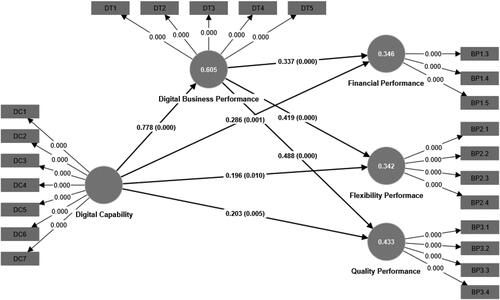

Furthermore, after the measurement model (), the last stage assesses the structural or inner model. The first test used the coefficient of determination (R2). If the R2 value is 0.75 or higher, it means that exogenous variables have a substantial impact on the endogenous variable. If the R2 value is in the range of 0.5–0.75, it implies a moderate impact, a weak effect with a range of 0.25–0.5, and the R2 value is 0.25 or less is typically indicative of no impact value (Hair et al., Citation2019).

The R2 value in the current research shows that the digital capability variable influences 0.61 (61%) of the digital business transformation variable, which is a moderate level (Hair et al., Citation2019). The mean R2 value of small business performance was 37%. This indicates that small business performance is influenced by digital capability and transformation by only 37%. Specifically, quality performance had the highest value (R2 = 0.43, 43%), followed by financial performance (R2 = 0.346) and flexibility performance (R2 = 0.342). Generally, the R2 values for small business performance are weak. It assumes that the many factors influencing business performance, including financial, flexibility, and quality performance, are beyond the scope of this research. Digital capability and business transformation have only a small effect on business performance.

Thus, cross-validated redundancy (Q2) is an alternative approach for evaluating the predictive relevance of a model. Q2 served as an indicator of the model’s predictive strength. Q2 demonstrates the predictive significance of endogenous constructs. To illustrate the predictive accuracy of the structural model, Q2 values must exceed 0. Generally, Q2 values >0, 0.25, and 0.50 indicate the small, medium, and large predictive relevance of the PLS-path model (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Based on the results of Q2 measurement, the Q2 value of digital business transformation is 0.6, which means that the latent variable has a large predictive value. Meanwhile, the Q2 value of small business performance (financial, flexibility, and quality performance) indicates a medium predictive value, in which the Q2 value of quality performance (Q2 = 0.333) is the highest compared to financial performance (Q2 = 0.290) and flexibility performance (Q2 = 0.264).

Finally, the hypotheses in this study were evaluated using path coefficients among the variables. From the results obtained, it can be highlighted that all of the hypotheses, both direct and indirect, in this study are accepted, as shown in and and and .

Table 6. Path coefficient.

Table 7. Mediating effect of digital business transformation.

5. Discussion

First, our study confirms that digital capability positively and significantly affects digital business transformation. This finding proves that digital capabilities significantly accelerate the digital transformation of small businesses. This means that the better small business actors possess digital capabilities, the greater the possibility of realizing digital transformation. These findings support those of a previous study (Cetindamar et al., Citation2024; González-Varona et al., Citation2021; Kulathunga et al., Citation2020; Okundaye et al., Citation2019; Priyono et al., Citation2020; Zhang-Zhang et al., Citation2022). This study also makes obvious contributions to knowledge-based view theory, which posits that technological proficiency is the decisive factor for achieving success in the digital era (Cooper et al., Citation2023). Adapting quickly to rapid technological and environmental changes will greatly determine small business competitiveness (Pieroni et al., Citation2019). It is relevant to the dynamic capability theory, which emphasizes the ability to respond and deal with a rapidly changing environment (Teece et al., Citation1997). The ability of small businesses to identify technological opportunities related to customer needs and optimize internal resources to use potential digital platforms, such as social media and e-commerce, is a fundamental factor in accelerating digital business transformation.

Second, our results indicate that digital capabilities significantly affect financial performance. A positive coefficient indicates that the better the digital capability, the more financial performance will increase. Empirically, these results reinforce the findings of Hussain and Papastathopoulos (Citation2022), Lee et al. (Citation2022), Nasiri et al. (Citation2020), and Wang et al. (Citation2022). The ability to use various digital devices, software, and digital applications can improve financial performance, such as budget planning and financial management properly and adequately. Generally, this result confirms the findings of Chen et al. (Citation2023), Khin and Ho (Citation2019), and Ullah et al. (Citation2021) claim that digital capability, a knowledge resource, is an antecedent factor in enhancing business performance. This result also reinforces the knowledge-based view theory, in which all forms of knowledge are resources for improving competitive advantage (Grant, Citation1996).

Third, our study showed that digital capability directly and significantly positively affects flexibility performance. This proves that digital capabilities can significantly increase the flexibility performance of small businesses, such as the ability to respond to and fulfill customers’ needs quickly. This result confirms (Alsufyani & Gill, Citation2022) that flexibility performance is appropriate for measuring adaptive organizational performance. In addition, this study aligns with the results of previous studies by Lee et al. (Citation2022).

Fourth, digital capabilities can significantly increase the quality performance of small businesses. This means that the better the digital capabilities, the greater the possibility of increased quality performance. These findings support the statements of Saryatmo and Sukhotu (Citation2021) and Sharma and Joshi (Citation2023). Although it does not explicitly examine the relationship between digital capability and quality performance, the effect of digital capability on quality performance is one of the factors supporting an increase in quality performance. The ability to provide programs that focus on improving employee competencies, establishing strong relationships with suppliers and consumers, and increasing employee welfare are proven to enhance the quality performance of small businesses.

Furthermore, our study confirms that digital business transformation has a direct and significant effect on small business performance, both financially and in terms of flexibility and quality. First, digital business transformation can enhance financial performance. This implies that the greater the digitally managed SMEs, the greater their potential to improve financial performance. These findings support the previous study by Teng et al. (Citation2022). Thus, Hypothesis H5 is accepted.

Second, digital business transformation significantly influences flexibility performance, supporting Hypothesis H6. This means that the flexibility performance to respond to customers’ needs rapidly will be influenced by how well SMEs actors can transform their business using the digital technology mindset. This result also supports the findings of Huo et al. (Citation2021) and Rossini et al. (Citation2021).

Additionally, hypothesis H7 states that digital business transformation significantly impacts small business quality performance. This result confirms that hypothesis H7 can be accepted and aligns with prior research from Alathamneh and Al-Hawary (Citation2023) and Saryatmo and Sukhotu (Citation2021) who state that small business quality performance can improve through digital transformation. Generally, these results confirm the knowledge-based view (KBV) concept, in which the organizational ability to optimize its knowledge will positively impact performance and company competitiveness (Spender, Citation1994).

Finally, our findings validate the significant role of digital business transformation in mediating the relationship between digital capabilities and small business performance: financial, flexibility, and quality performance. This result strengthens the assumption that the effect of digital capability on small business performance will be more significant if digital business transformation is simultaneously strengthened. Therefore, these findings support the previous studies of Heredia et al. (Citation2022) and Tsou and Chen (Citation2023).

5.1. Theoretical implications

The present research provides substantial evidence concerning the impact of digital capabilities on digital business transformation and business performance using a knowledge-based view and dynamic capability theory. Additionally, we contribute to the discussion (Bai et al., Citation2020; Pieroni et al., Citation2019) on the role of dynamic capability to explain how SMEs respond to rapid technological and environmental changes and support them to enhance competitive advantage. Dynamic digital capability can enhance small business performance by effectively coordinating digital technologies and business performance. Furthermore, we enhance the existing body of knowledge by emphasizing the suitability of employing the knowledge-based view (KBV) theory to address strategic concerns in the development of SMEs, particularly in dynamic environments.

This study also proposes multiple dimensions of the small business performance model. It uses three dimensions of small business performance (financial, flexibility, and quality) as determinant factors of digital capability and digital business transformation in the SMEs sector. Within this framework, the impacts of several antecedents on specific small business performance are likely to be clarified from a digital perspective. Subsequently, one of the contributions of this research is related to a deeper understanding of SMEs performance, not only from financial but also non-financial aspects, and to the development of theories for improving SMEs performance. This study may serve as a guide for future research.

5.2. Practical implications

This study has several practical implications for business practitioners (entrepreneurs) and policymakers. First, digital capability is crucial for SMEs to enhance their business performance in emerging markets. By improving digital capabilities, SMEs owners may relatively easily sense, seize, and transform new information, as well as new knowledge useful for increasing business performance.

Second, for public policymakers, a project grant can be used to offer digital proficiency training to both employees and owners of SMEs. Simultaneously, policymakers can create an SMEs digital ecosystem to collaborate with SMEs owners and strengthen social capital positively.

6. Conclusions and limitations

These findings demonstrate that digital capability significantly and positively influences digital business transformation and small business performance. Particularly during the emerging era, when digital capabilities became essential for all business actors, it was observed that digital capability also played a crucial role in ensuring small business performance, including financial, flexibility, and quality performance. Moreover, this study revealed that digital business transformation affects business performance. additionally, digital business transformation acts as a mediator, reinforcing the effect of digital business transformation on small business performance. Based on these findings, this study provides several recommendations.

First, small business owners must continuously improve their digital capabilities. By doing so, they can survive and capitalize on digital opportunities, foster digital business transformation, and enhance business performance. Second, the government should optimize the scope of its economic stimulus policies, mainly focusing on supporting small business owners to enhance digital capabilities through training, coaching, mentoring, and other programs. This approach will accelerate the resurgence of the small business sector in the digital age. In conclusion, this study highlights the critical role of digital capability and transformation in small business development, especially in developing countries.

Finally, this study had several limitations. First, it was restricted to small businesses located in East Java, Indonesia. The participants of this study were limited to small business owners who were selected using convenience sampling, and only 330 respondents were selected. The sample may not represent all small businesses that perform digital transformation. The second limitation concerns item interpretation; therefore, respondents may need to help understand the meaning of the question.

Author contributions

Yudha Prakasa developed the research design and collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. Zulfiqar Ali Jumani verified the analytical methods and supervised the findings of this study. All authors drafted and discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yudha Prakasa

Yudha Prakasa is a lecturer at Business Administration, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia. Currently, he is PhD student at Khon Kaen Business School in Khon Kaen, Thailand. His research interests include entrepreneurship, human resources, and organizational development.

Zulfiqar Ali Jumani

Zulfiqar Ali Jumani obtained his PhD from Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai campus, between January 11, 2017, and March 2020. He is currently working as a lecturer at Khon Kaen Business School in Khon Kaen, Thailand. His research interests include consumer behavior, digital marketing, Islamic branding, and halal branding.

References

- Alathamneh, F. F., & Al-Hawary, S. I. S. (2023). Impact of digital transformation on sustainable performance. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 7(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2022.12.020

- AlKoliby, I. S. M., Abdullah, H. H., & Suki, N. M. (2023). Linking knowledge application, digital marketing, and manufacturing SMEs’ sustainable performance: The mediating role of innovation. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01157-4

- Alsufyani, N., & Gill, A. Q. (2022). Digitalisation performance assessment: A systematic review. Technology in Society, 68, 101894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101894

- Anatan, L. (2023). Micro, small, and medium enterprises’ readiness for digital transformation in Indonesia. Economies, 11(6), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies

- Annarelli, A., Battistella, C., Nonino, F., Parida, V., & Pessot, E. (2021). Literature review on digitalization capabilities: Co-citation analysis of antecedents, conceptualization and consequences. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120635

- Ardito, L., Raby, S., Albino, V., & Bertoldi, B. (2021). The duality of digital and environmental orientations in the context of SMEs: Implications for innovation performance. Journal of Business Research, 123, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.022

- Bai, C., Dallasega, P., Orzes, G., & Sarkis, J. (2020). Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: A sustainability perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 229, 107776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107776

- Bai, C., Quayson, M., & Sarkis, J. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic digitization lessons for sustainable development of micro-and small-enterprises. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 1989–2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.035

- Baker, G., Lomax, S., Braidford, P., Allinson, G., & Houston, M. (2015). Digital capabilities in SMEs: Evidence review and re-survey of 2014 small business survey respondents.

- Bourlakis, M., Maglaras, G., Aktas, E., Gallear, D., & Fotopoulos, C. (2014). Firm size and sustainable performance in food supply chains: Insights from Greek SMEs. International Journal of Production Economics, 152, 112–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.12.029

- Cetindamar, D., Abedin, B., & Shirahada, K. (2024). The role of employees in digital transformation: A preliminary study on how employees’ digital literacy impacts use of digital technologies. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2021.3087724

- Chen, Y. A., Guo, S. L., & Huang, K. F. (2023). Antecedents of internationalization of Taiwanese SMEs: A resource-based view. International Journal of Emerging Markets. Ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-05-2022-0875

- Cooper, S. C., Pereira, V., Vrontis, D., & Liu, Y. (2023). Extending the resource and knowledge based view: Insights from new contexts of analysis. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113523

- Erlanitasari, Y., Rahmanto, A., & Wijaya, M. (2020). Digital economic literacy micro, small and medium enterprises (SMES) go online. Informasi, 49(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.21831/informasi.v49i2.27827

- Fauzi, A. A., & Sheng, M. L. (2022). The digitalization of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs): An institutional theory perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(6), 1288–1313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1745536

- Ferreira, J., Coelho, A., & Moutinho, L. (2020). Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation, 92–93, 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2018.11.004

- Galindo-Martín, M. Á., Castaño-Martínez, M. S., & Méndez-Picazo, M. T. (2019). Digital transformation, digital dividends and entrepreneurship: A quantitative analysis. Journal of Business Research, 101, 522–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.014

- Ganawati, N., Soraya, D., & Yogiarta, I. M. (2021). The role of intellectual capital, organizational learning and digital transformation on the performance of SMEs in Denpasar, Bali-Indonesia. International Journal of Science and Management Studies, 4(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.51386/25815946/ijsms-v4i3p122

- Gao, J., Zhang, W., Guan, T., Feng, Q., & Mardani, A. (2023). The effect of manufacturing agent heterogeneity on enterprise innovation performance and competitive advantage in the era of digital transformation. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113387

- González-Varona, J. M., López-Paredes, A., Poza, D., & Acebes, F. (2021). Building and development of an organizational competence for digital transformation in SMEs. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 14(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.3279

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Heenkenda, H. M. J. C. B., Xu, F., Kulathunga, K. M. M. C. B., & Senevirathne, W. A. R. (2022). The role of innovation capability in enhancing sustainability in SMEs: An emerging economy perspective. Sustainability, 14(17), 10832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710832

- Heredia, J., Castillo-Vergara, M., Geldes, C., Carbajal Gamarra, F. M., Flores, A., & Heredia, W. (2022). How do digital capabilities affect firm performance? The mediating role of technological capabilities in the “new normal”. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(2), 100171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100171

- Hirvonen, J., & Majuri, M. (2020). Digital capabilities in manufacturing SMEs. Procedia Manufacturing, 51, 1283–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.10.179

- Hudson, M., Smart, A., & Bourne, M. (2001). Theory and practice in SME performance measurement systems. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 21(8), 1096–1115. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005587

- Huo, B., Haq, M. Z. U., & Gu, M. (2021). The impact of information sharing on supply chain learning and flexibility performance. International Journal of Production Research, 59(5), 1411–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1824082

- Hussain, M., & Papastathopoulos, A. (2022). Organizational readiness for digital financial innovation and financial resilience. International Journal of Production Economics, 243, 108326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108326

- Janssen, J., Stoyanov, S., Ferrari, A., Punie, Y., Pannekeet, K., & Sloep, P. (2013). Experts’ views on digital competence: Commonalities and differences. Computers & Education, 68, 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.06.008

- Kafetzopoulos, D. (2022). Performance management of SMEs: A systematic literature review for antecedents and moderators. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(1), 289–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-07-2020-0349

- Kahrović, E., & Avdović, A. (2023). Impact of digital technologies on business performance in Serbia. Management: Journal of Sustainable Business and Management Solutions in Emerging Economies, 28(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.7595/management.fon.2021.0039

- Kamar, K., Lewaherilla, N. C., Muna, A., Ausat, A., Ukar, K., & Gadzali, S. S. (2022). The influence of information technology and human resource management capabilities on SMEs performance. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 6(1), 2579–7298. https://doi.org/10.29099/ijair.v6i1.2.676

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1991). The balanced scorecard-measures that drive. Performance Harvard Business Review.

- Kerti Yasa, N. N., Ekawati, W. N., & Dewi Rahmayanti, L. P. (2019). The role of digital innovation in mediating digital capability on business performance. European Journal of Management and Marketing Studies, 4(2), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3483780

- Khan, R. U., Salamzadeh, Y., Shah, S. Z. A., & Hussain, M. (2021). Factors affecting women entrepreneurs’ success: A study of small- and medium-sized enterprises in emerging market of Pakistan. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00145-9

- Khin, S., & Ho, T. C. F. (2019). Digital technology, digital capability and organizational performance: A mediating role of digital innovation. International Journal of Innovation Science, 11(2), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-08-2018-0083

- Kulathunga, K. M. M. C. B., Ye, J., Sharma, S., & Weerathunga, P. R. (2020). How does technological and financial literacy influence SME performance: Mediating role of ERM practices. Information, 11(6), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11060297

- Kwong-Kay Wong, K. (2019). Praise for mastering partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS in 38 hours.

- Lee, K. L., Azmi, N. A. N., Hanaysha, J. R., Alzoubi, H. M., & Alshurideh, M. T. (2022). The effect of digital supply chain on organizational performance: An empirical study in Malaysia manufacturing industry. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 10(2), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2021.12.002

- Levallet, N., & Chan, Y. E. (2018). Role of digital capabilities in unleashing the power of managerial improvisation. MIS Quarterly Executive, 17, 4–21.

- Li, L., Su, F., Zhang, W., & Mao, J. Y. (2018). Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Information Systems Journal, 28(6), 1129–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12153

- Li, S., Gao, L., Han, C., Gupta, B., Alhalabi, W., & Almakdi, S. (2023). Exploring the effect of digital transformation on firms’ innovation performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(1), 100317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100317

- Liu, X., Zhao, X., & Zhao, H. (2018). Absorptive capacity and business performance: The mediating effects of innovation and mass customization. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(9), 1787–1803. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2017-0416

- Mubarak, M. F., Shaikh, F. A., Mubarik, M., Samo, K. A., & Mastoi, S. (2019). The impact of digital transformation on business performance: A study of Pakistani SMEs. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research, 9(6), 5056–5061. https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.3201

- Naqshbandi, M. M., & Jasimuddin, S. M. (2018). Knowledge-oriented leadership and open innovation: Role of knowledge management capability in France-based multinationals. International Business Review, 27(3), 701–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.12.001

- Nasiri, M., Ukko, J., Saunila, M., Rantala, T., & Rantanen, H. (2020). Digital-related capabilities and financial performance: the mediating effect of performance measurement systems. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 32(12), 1393–1406. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1772966

- Neely, A. (2004). Business performance measurement: Theory and practice.

- Neumeyer, X., & Liu, M. (2021). Managerial competencies and development in the digital age. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 49(3), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2021.3101950

- Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., & Morris, M. H. (2021). Overcoming barriers to technology adoption when fostering entrepreneurship among the poor: The role of technology and digital literacy. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(6), 1605–1618. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2020.2989740

- OECD/ERIA (2018). ASEAN 2018 broasting competitiveness and inclusive growth. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305328-en

- Okundaye, K., Fan, S. K., & Dwyer, R. J. (2019). Impact of information and communication technology in Nigerian small-to medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 24(47), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEFAS-08-2018-0086

- Pfister, P., & Lehmann, C. (2023). Measuring the success of digital transformation in German SMEs. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 33(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.53703/001c.39679

- Pieroni, M. P. P., McAloone, T. C., & Pigosso, D. C. A. (2019). Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.036

- Priyono, A., Moin, A., & Putri, V. N. A. O. (2020). Identifying digital transformation paths in the business model of SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040104

- Proksch, D., Rosin, A. F., Stubner, S., & Pinkwart, A. (2021). The influence of a digital strategy on the digitalization of new ventures: The mediating effect of digital capabilities and a digital culture. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1883036

- Rossini, M., Cifone, F. D., Kassem, B., Costa, F., & Portioli-Staudacher, A. (2021). Being lean: How to shape digital transformation in the manufacturing sector. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 32(9), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-12-2020-0467

- Rowan, N. J., & Galanakis, C. M. (2020). Unlocking challenges and opportunities presented by COVID-19 pandemic for cross-cutting disruption in agri-food and green deal innovations: Quo Vadis? The Science of the Total Environment, 748, 141362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141362

- Rupeika-Apoga, R., Petrovska, K., & Bule, L. (2022). The effect of digital orientation and digital capability on digital transformation of SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 17(2), 669–685. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17020035

- Saryatmo, M. A., & Sukhotu, V. (2021). The influence of the digital supply chain on operational performance: A study of the food and beverage industry in Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(9), 5109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095109

- Shafi, M., Liu, J., & Ren, W. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium-sized Enterprises operating in Pakistan. Research in Globalization, 2, 100018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2020.100018

- Sharma, M., & Joshi, S. (2023). Digital supplier selection reinforcing supply chain quality management systems to enhance firm’s performance. The TQM Journal, 35(1), 102–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-07-2020-0160

- Solberg, E., Traavik, L. E. M., & Wong, S. I. (2020). Digital mindsets: Recognizing and leveraging individual beliefs for digital transformation. California Management Review, 62(4), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620931839

- Soto-Acosta, P. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Shifting digital transformation to a high-speed gear. Information Systems Management, 37(4), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2020.1814461

- Spender, J.-C. (1994). Knowing, managing and learning: A dynamic managerial epistemology. Management Learning, 25(3), 387–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050769402500302

- Taghizadeh, S. K., Karini, A., Nadarajah, G., & Nikbin, D. (2020). Knowledge management capability, environmental dynamism and innovation strategy in Malaysian firms. Management Decision, 59(6), 1386–1405. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-01-2020-0051

- Taherdoost, H. (2019). What is the best response scale for survey and questionnaire design; Review of different lengths of Rating Scale/Attitude Scale/Likert Scale. International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 8(1), 1–10.

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Teece, D., & Pisano, G. (1994). The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(3), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/3.3.537-a

- Teng, T., Tsinopoulos, C., & Tse, Y. K. (2022). IS capabilities, supply chain collaboration and quality performance in services: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 122(7), 1592–1619. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2021-0496

- Teng, X., Wu, Z., & Yang, F. (2022). Research on the relationship between digital transformation and performance of SMEs. Sustainability, 14(10), 6012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106012

- Thukral, E. (2021). COVID-19: Small and medium enterprises challenges and responses with creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Strategic Change, 30(2), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2399

- Tsou, H.-T., & Chen, J.-S. (2023). How does digital technology usage benefit firm performance? Digital transformation strategy and organisational innovation as mediators. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 35(9), 1114–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2021.1991575

- Ullah, H., Wang, Z., Bashir, S., Khan, A. R., Riaz, M., & Syed, N. (2021). Nexus between IT capability and green intellectual capital on sustainable businesses: Evidence from emerging economies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 28(22), 27825–27843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-12245-2

- Vrontis, D., Chaudhuri, R., & Chatterjee, S. (2022). Adoption of digital technologies by SMEs for sustainability and value creation: Moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Sustainability, 14(13), 7949. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137949

- Wang, X., Gu, Y., Ahmad, M., & Xue, C. (2022). The impact of digital capability on manufacturing company performance. Sustainability, 14(10), 6214. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106214

- Yasin, A., Vehari, W., & Sadia Hussain, P. (2022). Digitalization and firm performance: mediating role of smart technologies. Journal of Tianjin University Science and Technology, 55(4). https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8FNDC

- Yeow, A., Soh, C., & Hansen, R. (2018). Aligning with new digital strategy: A dynamic capabilities approach. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 27(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2017.09.001

- Yu, H., Fletcher, M., & Buck, T. (2022). Managing digital transformation during re-internationalization: Trajectories and implications for performance. Journal of International Management, 28(4), 100947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2022.100947

- Yusuf, M., Surya, B., Menne, F., Ruslan, M., Suriani, S., & Iskandar, I. (2022). Business agility and competitive advantage of SMEs in Makassar City, Indonesia. Sustainability, 15(1), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010627

- Zapata-Cantu, L., Sanguino, R., Barroso, A., & Nicola-Gavrilă, L. (2023). Family business adapting a new digital-based economy: Opportunities and challenges for future research. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14(1), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00871-1

- Zhang-Zhang, Y. Y., Rohlfer, S., & Varma, A. (2022). Strategic people management in contemporary highly dynamic VUCA contexts: A knowledge worker perspective. Journal of Business Research, 144, 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.069

- Zhou, K. Z., & Wu, F. (2010). Technological capability, strategic flexibility, and product innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 547–561. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.830