Abstract

This paper aims to explore the bottom-up emergence of inter-organizational knowledge flow mechanisms within collaborative innovation processes in the research-based organizations, including universities and companies. The knowledge flow mechanism in collaborative innovation is viewed from the process of knowledge sharing and absorption. The data is primarily based on interviews with representatives of the case organizations involved in open innovation projects, who also act as actors in the collaborative innovation processes. This research discovers and provides insights into the mechanisms used in knowledge sharing and absorption. It also posits the role of actors as ‘intermediaries’ in the process of cross-organizational team interaction in managing knowledge flows.

IMPACT STATEMENT

This study aims to explore the bottom-up emergence of inter-organizational knowledge flow mechanisms within collaborative innovation processes in the research-based organizations, including universities and companies. The knowledge flow mechanism in collaborative innovation is viewed from the process of knowledge sharing and absorption. By conducting in-depth interview, our findings highlight the importance of mechanisms that used in knowledge sharing and absorption. In addition, our findings are also show the intermediaries role of actors in the process of cross-organizational team interaction in managing knowledge flows. The results offer significant perspectives for managers overseeing collaborative innovation initiatives, especially those that operate in cross-border or cross-cultural contexts with suppliers, partners, or other external entities.

1. Introduction

This paper discusses open innovation (abbreviated OI) from a knowledge flow perspective. As attention to OI constantly growing, including in practice by many firms (Enkel et al., Citation2009), in particular issues related to firm openness and innovation capacity became foci in OI research (Le et al., Citation2019). The definision of the concept has been shifted to the importance of the management of knowledge flows, inbound and outbound, in firms’innovation process (Bigliardi et al., Citation2021). This shift put knowledge and its management central to OI research (Natalicchio et al., Citation2017). OI has therefore been about organizational ability to combines internal and external knowledge to increase innovation capacity (Bogers, Citation2011). Firm’s ability to manage knowledge flows is therefore core to OI (Chesbrough & Bogers, Citation2014). Despite the centrality of knowledge flow management, surprisingly, OI research still lacks appropriate attention to detailed management of knowledge flow processes. This includes the process of sharing and absorbing knowledge that determines the success of OI (Sung & Choi, Citation2018).

Knowledge flow means ‘knowledge movements across people, organizations, places and time, depicting changes, shifts and applications’ (Chauvel, Citation2016). Knowledge and know-how are delivered through various paths of human, group, and/or organizational interactions (Kim et al., Citation2017). In OI context, firms manage and capitalize on internal innovation. Knowledge inflows and outflows show active knowledge sourcing and sharing processes between relevant parties involved in a project (Engelsberger et al., Citation2022). In such a process, absorptive capacity plays a central role in OI.

Despite its centrality, literature is scant on aspects to understand the nature of knowledge flows in OI (Cleveland et al., Citation2015). In addition to that, only a few OI studies use a knowledge flow perspective (Shi et al., Citation2021). With the aforementioned, we argue that, first, it is important to study how knowledge flows within OI projects (Vanhaverbeke et al., Citation2008). Likewise, knowledge sharing (KS) process is crucial. Both knowledge sharing (KS) and absorptive capacity (AC) are therefore two, among others, important concepts in understanding knowledge flows in OI. Unfortunately, these concepts are often discussed separately in OI studies. In a review of the nature of the relationship between KS and AC, researchers show that these two concepts are in mutually reinforcing relationship (Balle et al., Citation2020). We believe that the process of sharing and absorbing knowledge between parties involved in OI does not occur automatically but requires certain mechanisms. Therefore, our study on knowledge flows thus pays attention to both the knowledge-sharing and absorptive capacity of organizations involved in OI.

To study the phenomenon of knowledge flows management within OI projects naturally, we propose a rather general research question, ‘How does knowledge flow occur within OI project?’ We expect to capture rich processes of inflows and outflows of knowledge, also to understand the capacity (including willingness) to share and absorb knowledge while organizations interact in OI project. We emphasize a process-oriented approach in this research, intending to build a bottom-up understanding of collaborative innovation or OI implementation, through the lens of a knowledge flow perspective.

To present the result of our research, we organize thies article as follow. In the next section we first present and discuss relevant literature on knowledge flow within OI setting. As we pay attention to interaction at individual level, we include a review of micro-foundation of knowledge flow. The following section describes our research method. Research findings are presented afterwards, followed by discussion, implications, and conclusions.

2. Literature review

Capability to innovate has become an important factor in revealing the competitiveness in a rapidly changing and competitive business environment. The increasing degree of technological change and economic globalization demands constant innovation from companies to survive in a highly competitive business landscape (Donate et al., Citation2016). Not only product life cycle becomes shorter, the ability to innovate is also getting increasingly crucial as substitute products emerge and breaks the boundaries of product lines. Innovation much be while companies must also be able to adapt to changes. Therefore, OI was first introduced by Chesbrough (Citation2003), it is considered an appropriate and response to such a situation therefore it has received increasing attention from researchers and practitioners (West & Bogers, Citation2017).

OI means a few of things. It is systematic encouraging and exploring a wide range of internal and external (knowledge) resources for innovation opportunities (West & Gallagher, Citation2006), consciously integrating that (knowledge) exploration with firm capabilities and resources, and broadly exploiting those opportunities through multiple channels (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990). In such a nature, Chesbrough (Citation2003) views that through OI external ideas, as well as internal ideas, are used in innovation processes inside and/or outside firm boundaries. OI can therefore be understood as the ability to create an ecosystem that encourage co-creation (West & Bogers, Citation2017) between two or more firms through various activities that are carried out continuously. In such a process the acquisition, transfer, and use of information happen across organizational boundary of the companies.

OI research and practice covers a wide range of topics, including open source, crowdsourcing, IP licensing, university collaborations, startup engagements, corporate venture capital, supplier-driven innovation, and user innovation – to name a few. All the processes involve the flow of knowledge across organizational boundaries (Shi et al., Citation2021). The inflows and outflows of knowledge are used to accelerate innovation (Bogers et al., Citation2018). Cross-boundary interactions take place between companies that allows the flow and utilization of knowledge between them. The combine of inflows and outflows of knowledge for innovation purposes is called coupling process (Bogers et al., Citation2018; Enkel et al., Citation2009; Laursen & Salter, Citation2006; Mazzola et al., Citation2015).

Although knowledge flows perspective has not been widely used in OI studies (Ogink et al., Citation2023). Yet there have been studies such as patent citation information that explores OI a knowledge flow perspective (Yun et al., Citation2018). However, research still overlooks interactions between individuals and/or groups and the role of actors in the flow of knowledge. We argue that efforts are needed to manage the flows of knowledge between individuals or groups, both for knowledge-sharing and knowledge absorption. In order to understand that, a conceptual explanation regarding knowledge flow, knowledge sharing, absorption capacity, and organizational mechanism happen during OI is provided below, started with an understanding of knowledge management framework.

2.1. Knowledge management process and flow

Knowledge management can be defined in different ways (Lopez-Cabrales et al., Citation2009), for example in accordance with the way knowledge is defined (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001). If we take the process view of knowledge management, for example, knowledge management comprises of the creation, capturing, or acquisition, documentation or storing, sharing, distribution, or transfer, and use or application of knowledge (e.g. Andreeva & Kianto, Citation2011) as ‘the primary source economic rent (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001)’. Business enterprises therefore develop the ways knowledge resources can be effectively managed in order to maintain or increase their level of competitiveness dealing with rising challenges from the increasing competitive environment (Liao et al., Citation2010).

While knowledge flow perspective, as previously mentioned, sees knowledge management as the movement of knowledge across contexts, including between individual (Chauvel, Citation2016). This understanding is in line with OI’s definition as the process of leveraging inflows and outflows of knowledge to increase both internal innovation and use of external markets (Chesbrough, Citation2003; Lopes & de Carvalho, Citation2018; Shi et al., Citation2021). Knowledge flow is a knowledge system that passes between individuals or a knowledge processing mechanism (Zhuge, Citation2002). In this case knowledge sharing and acquisition are important factors in knowledge flow. They reflect the flow of knowledge where the knowledge possessed by an individual is converted into a form that can be understood, absorbed, and used by other individuals (Ipe, Citation2003). Therefore knowledge flow includes direction, content, and carrier (Zhuge, Citation2002).

2.2. Knowledge flow in open innovation

Innovation occurs because of the effective exchange, transfer, and application of existing knowledge (Özbağ et al., Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2014). This reflects the flow of knowledge where the knowledge held by an individual is shared, absorbed, and used by other individuals (Ipe, Citation2003). The process of knowledge flow among individuals can stimulate innovation (Mabey et al., Citation2015; Wei et al., Citation2011). Therefore, unconstrained knowledge flows refine collective thinking and spur the application and utilization of knowledge, thereby enhancing the ability of a firm to develop innovative responses to environmental challenges. Thus, the flow of knowledge that occurs without barriers between individuals and groups has an impact on innovation (Kang et al., Citation2007; Mabey et al., Citation2015; Wei et al., Citation2011).

Chesbrough and Bogers (Citation2014) also describe OI as ‘a distributed innovation process on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries’. It provides insights into how firms can harness inflows and outflows of knowledge to improve their innovation success (Bogers et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, Engelsberger et al. (Citation2022), they were conceptualizing the mutual inflow (sourcing) and outflows (sharing) of knowledge. It represents the mutual sharing and sourcing of knowledge at the individual level which translates into the inflow and outflow of knowledge at the organizational level, ultimately driving OI performance (Engelsberger et al., Citation2022). However, Cabrera and Cabrera (Citation2002) suggested reducing the time in distributing individual ideas (e.g. Make systematic efforts to facilitate the knowledge sharing process at both individual and organizational levels) is an effective way of managing organizational knowledge (Cabrera & Cabrera, Citation2002). Thus various facilitation practices will relate to the flow of knowledge (Sung & Choi, Citation2018).

2.2.1. Knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing is considered to be the central element of knowledge flow. As a coupled process of OI, collaborative innovation combines the inflows and outflows so that its success is therefore predetermined by how knowledge is shared during the collaborative process (Bogers, Citation2011). Although, how to effectively manage knowledge sharing in open collaborative innovation is not yet fully understood (Enkel et al., Citation2009). To be successful in open collaborative innovation, firms and external partners need to aggregate and share valuable knowledge between themselves (Bogers, Citation2011; Gulati & Singh, Citation1998). The exchange of information among organizational employees is a vital component and thus modern information and telecommunications technology is available to support such exchanges across time and distance barriers that are common in cross-organizational innovation collaborations. Information technology is often built around some type of intranet, shared database, or group software that enables people to communicate with each other, share ideas, and engage in discussions, among others (Cabrera & Cabrera, Citation2002). Knowledge sharing is a behavioral phenomenon that involves information exchange and knowledge creation among employees, groups, and organizations through socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization (van den Hooff & de Ridder, Citation2004).

Many scholars emphasized the important role of knowledge sharing in enhancing innovation capability (Liao et al., Citation2007; Wang & Wang, Citation2012). For example, Wang and Wang (Citation2012) supposed that innovation initiatives mostly arise from the process of sharing knowledge, experience, and skill, and a firm’s capability to transform and apply knowledge may decide its level of innovation capability. Engagement of employees in KS contributes to learning and improves their skills and competencies which enhances their abilities to develop new routines and procedures (Chen & Huang, Citation2009) and innovative products (Wang & Wang, Citation2012).

The knowledge-sharing process also helps the dissemination of knowledge within an organization (Bock et al., Citation2005). Knowledge sharing in organizations is the process by which one unit (e.g. group, department, or division) is affected by the experience of another (Argote & Ingram, Citation2000). It is a dynamic, interactive process (Bengoa & Kaufmann, Citation2014), which occurs when one individual wants to either donate knowledge or acquire that of other individuals to build skills (Naim & Lenkla, Citation2016) and new knowledge (Song, Citation2014). In sharing knowledge, the knowledge held by the donor is transferred to the recipient through a variety of methods such as personal interaction, information systems, and networks (Daghfous & Ahmad, Citation2015). Therefore, to encourage knowledge sharing, it is necessary to promote social interaction between individuals (Naim & Lenkla, Citation2016).

An emphasis on knowledge sharing fosters individual learning, organizational learning, and innovation (King, Citation2009; Swift & Hwang, Citation2013). To nurture knowledge sharing in the organization and between organizations, it is critical to establish a process of social interactions between individuals, grups, and cross organization. Social interactions involve the exchange of knowledge, skills, and expertise, in turn, creates a learning environment, which reinforces organization-wide learning. When sharing knowledge, the participating units influence each other’s knowledge, facilitating the joint creation of new knowledge (van Wijk et al., Citation2008).

2.2.2. Absorptive capacity

Knowledge acquisition can be enabled through an organization’s external and internal networks, which would be used to absorb knowledge to promote innovation within an organization (Lopez & Esteves, Citation2013). Acquisition of knowledge from external resources enables individuals to develop new knowledge and revamp existing knowledge (Chen & Huang, Citation2009) which improves their creative thinking leading toward enhanced innovation. However, the use of knowledge obtained from both external and internal sources requires the absorptive capacity to generate innovation (Liao et al., Citation2010; Liao & Barnes, Citation2015).

OI and absorptive capacity are two concepts in contemporary innovation management literature. Although there is not much literature systematically linking each other way, absorptive capacity determines their ability to in-source externally developed ideas (Vanhaverbeke et al., Citation2008). Absorptive capacity is an important capability that enables organizations to leverage external knowledge for innovation purposes (Dahlin et al., Citation2020).

Absorptive capacity is an organization’s capability to absorb knowledge from its external environment and use it for innovation purposes (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990; Zahra & George, Citation2002). Therefore, in terms of gathering external knowledge, companies need the ability to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge (Schmidt, Citation2009). Absorptive capacity comprises several stages sequential, such as an organization first has to identify and obtain valuable external knowledge (i.e. recognition); it then has to understand this knowledge and internalize it by blending it with existing knowledge (i.e. assimilation and transforms); finally, it must be able to apply the internalized knowledge commercially (i.e. exploitation), such as by innovating its products, processes, or services. Knowledge is considered successfully absorbed only after the successful completion of all stages (von Briel et al., Citation2019).

Absorptive capacity is therefore now an important concept in OI (Vanhaverbeke et al., Citation2008). Absorptive capacity provides an overview of the organization’s need to recognize and fulfill knowledge from the external environment through inter-organizational relationships. This explains that absorptive capacity is a determinant of the company’s ability to obtain capabilities from partners (Mowery et al., Citation1996) and is an example of using external knowledge (Lane & Lubatkin, Citation1998; Sun & Anderson, Citation2008; Szulanski, Citation1996) in generating greater innovation (Tsai, Citation2001). However, linking the organization’s internal networks with external sources of information, the mechanism of absorptive capacity underlines that any individual effort combining external search with assimilation and utilization activity will lead to more effective absorption (i.e. learning) from external knowledge (Ogink et al., Citation2023). Therefore the concept of absorptive capacity is important in OI studies because it explains the company’s ability to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge from outside the organization (Schmidt, Citation2009) to accelerate innovation.

In inter-organizational activities that are interdependent, this gives rise to interactions across organizational boundaries that can have an impact on the flow of knowledge, both inflows and outflows that transcend organizational boundaries. In this case, absorption is needed to utilize the various knowledge provided by each party to produce valuable things with transfer and collaboration capabilities (Buckley & Carter, Citation2004).

Based on the literature review, to understand the mechanism of knowledge flow in OI there are 3 large groups: (1) knowledge flows, (2) knowledge flow processing, and (3) barriers in knowledge flow. The 3 major groups listed are explained in column 2 which is divided into several subcategories, related to ‘direction’, ‘mechanism’, and ‘potential obstacles’ to the flow of knowledge in OI.

Table 1. Relevant themes of knowledge flow in open innovation found in the literature.

2.3. Micro faoundation of knowledge flow within open innovation

Taking into account the complexity of interactions in innovation collaboration between organizations, a micro foundation approach is needed (Abell et al., Citation2008; Barney & Felin, Citation2013) to build a model that pays attention to the process of interaction between individuals (Barney & Felin, Citation2013) so that it can help explain how the process of knowledge flow is in the implementation of OI.

In collaborative innovation, the individual plays a role in the process of acquiring new knowledge (Schuler et al., Citation2004). Individuals also play a role in monitoring and delivering technical information in a form that can be understood by the group. Therefore, the role of individuals as knowledge carriers and intermediaries in the knowledge flows process requires appropriate internal organizational mechanisms that support the flow of knowledge between teams or across organizations.

The effective management of the knowledge flow requires the development of internal organizational mechanisms that focus on accessing, integrating, and sharing external and internal knowledge (Cleveland et al., Citation2015). Cleveland et al. (Citation2015) argues that several practices (e.g. degree of communication formality, interaction mode, information flow, coordination mode) will have a positive impact on knowledge flow under certain conditions (Cleveland et al., Citation2015).

Inter-firm knowledge transfer success is predetermined by how knowledge is shared in such collaborative efforts (Bogers, Citation2011). It means the exchange of information among organizational employees is a vital component. Likewise, intra-firm knowledge transfer is essential for effective knowledge management, it is carried out by bringing the knowledge acquired by individuals, teams, or business units to the level of the entire organization (Tsai, Citation2001). As a consequence, firms should facilitate knowledge sharing among individuals to improve their knowledge base. The geographical dispersion of knowledge repertoires makes knowledge sharing and exchange within multinational firms even more difficult.

According to the knowledge-based view, the main purpose of a firm is to coordinate and combine knowledge, and its capacity to perform these mechanisms determines organizational boundaries. Information technologies have evolved rapidly during the last decade and their collaborative properties have leveraged data exchange and knowledge sharing within and between organizations. Information technologies and collaborative platforms have fostered organizational learning and corporate knowledge management practices (Argote et al., Citation2003).

3. Methods

In this study, a qualitative case study was conducted in a very formal organization. This approach is used to reveal the organization’s internal mechanisms in maintaining the flow of knowledge in an open collaborative innovation process. As this was not immediately apparent in the literature, we felt that an in-depth study through case study would help to reveal how knowledge flows through the processes of knowledge sharing and absorption in open collaborative innovation.

Qualitative case studies were taken from collaborative innovation projects in very formal organizations. This was done to explore the internal organizational mechanisms used in maintaining the flow of knowledge during the open innovation process. One case takes from the university-industry collaborative innovation, which will be used to describe the open collaborative innovation between university and industry. Although the primary orientation of higher education institutions and industrial companies is different, there is a key element that can be shared and mutually important for both institutions namely the exchange of knowledge (Meyer-Krahmer & Schmoch, Citation1998) or transfer of knowledge (Gertner et al., Citation2011). Benefits for universities, it can increase scientific productivity and even it can increase university funding and status in the middle of the challenge of the rising cost of education. Meanwhile, benefits for the industry can increase the company’s reputation and competitiveness. Through, university-industry open collaborative innovation, the university can play an important role to solve industry problems by designing new and innovative products. It also facilitates companies to get access to experts from universities.

The other two cases are drawn from the producer-consumer collaborative innovation they will be used to describe the open collaborative innovation between producer and consumer. Although the primary orientation of producers is to develop new products and markets, meanwhile, consumers are oriented to find a partner to develop new products or technologies, there is a key element that can be shared and mutually important for both institutions namely the exchange of knowledge (Meyer-Krahmer & Schmoch, Citation1998) or transfer of knowledge (Gertner et al., Citation2011). Two cases were taken from different organizational backgrounds, one case was taken from a research-based company engaged in the developing automation technology in collaboration with its consumer and the other case was taken from a manufacturing company engaged in the furniture industry in collaboration with retail company. Benefits for consumers are the fulfillment of the need for new products or technologies by company policies. Meanwhile, the benefits for producers can improve the company’s innovation, reputation, and competitiveness. Through producer-consumer collaborative innovation, producers can play an important role in solving consumer problems by designing new and innovative products or new technologies. It also facilitates the consumer to get access to experts from manufacturers.

The exchange of knowledge can be facilitated by for an example, the ‘university research team’ or ‘product development project team’ (acts as an R&D agent). These teams can also act as a facilitator of collaborations or mediators among the stakeholder to ensure a mutually beneficial partnership can be formed. provides additional information on the case organizations.

Table 2. The characteristics of the case organizations.

Focus of this study is directed on the internal organizational mechanisms used in the knowledge-sharing and absorption process to maintain the flow of knowledge in open collaborative innovation. This is done by exploring from the bottom up the emergence of knowledge flow mechanisms in open collaborative innovation. The interview process was carried out for approximately six months starting from the end of May 2021 until the middle of November 2021. The empirical material comprises 20 interviews with 11 informants who participated in face-to-face narrative interviews, conducted in Indonesia language, lasting 1.5 to more than 2 hours, all digitally recorded and transcribed. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world, which led to heavy restrictions on movement and physical meetings, and as a direct consequence all the remaining interactions in the study had to be held online, via Zoom or Meet. Hence, the interviewees were selected based on their roles and engagement in the collaborative innovation project.

The interviews were designed to gain an overview of their work or role in the company’s open innovation, including exploring practices such as with whom they interacted and how social integration processes were developed to support innovation collaboration activities. Some questions such as how the collaborative innovation process takes place. And the interview related to how the process of knowledge sharing and absorption takes place during collaborative innovation. What mechanism is used? How do the organization’s efforts support this process?

3.1. Data analysis

The empirical material was coded by the main author (manual coding), following general coding practices in inductive qualitative research (Miles & Huberman, Citation1984). First, when reading and rereading the transcripts, sections of text were marked, labeled, and sorted into initial concepts, in what is often called open coding (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). These initial concepts included mechanisms of ‘knowledge sharing within the team’, ‘knowledge sharing between teams’, ‘intermediary role in knowledge sharing’, ‘knowledge acquisition’, ‘knowledge assimilation’, ‘knowledge transformation’, ‘knowledge exploitation’, and ‘intermediary role in knowledge absorption’. Second-order dimensions were then formed about both the inductively generated empirical codes and previous research on knowledge flow and OI. This was an iterative processed in which all the authors of the paper participated, which helps us structure the second-order dimension into third-order themes that made sense to all co-authors. in the empirical section presents selected evidence from the empirical data analysis. In the last step, we developed a theoretical model by linking the themes and attributes to one another based on the empirical analysis, supported by logical reasoning and connections to ongoing conversations in the knowledge flow in OI literature.

Table 3. Profile of key informants.

4. Research findings

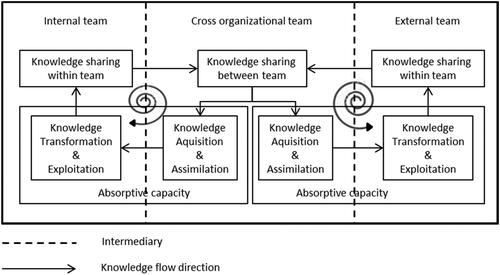

This research takes the context of collaborative innovation carried out between companies and partners along with the differences they have such as geography, language and culture, ways of working, or experience. The existence of these differences requires a mechanism that helps the flow of knowledge remain smooth and supports the collaborative innovation process. The results showed that one of the approaches taken was to form an internal team or a cross-organizational team in the implementation of collaborative innovation. Internal teams focus more on the process of transformation and exploitation of knowledge to innovate, while cross-organizational teams focus on the process of knowledge acquisition and assimilation as well as coordinating joint research project activities. The placement of the employees in cross-organizational teams as bridges that can help maintain the flow of knowledge within OI.

The success of the collaborative innovation process is determined by the flow of knowledge to support the process of transformation and exploitation of knowledge between the parties involved in the development of new products. This requires various efforts to maintain the flow of knowledge during the collaborative innovation process (Bogers et al., Citation2018; Engelsberger et al., Citation2022), not only forming internal teams and cross-organizational teams but also establishing mechanisms that encourage knowledge sharing (Bogers, Citation2011) and knowledge absorption (Buckley & Carter, Citation2004). Thus, collaborative innovation not only requires the willingness of each party to share their knowledge and competencies but also requires the organization’s ability to absorb external knowledge and combine it with internally available knowledge and competencies to be used in joint innovation.

Based on the research results, bottom-up exploration of the knowledge flow process during collaborative innovation can reveal the mechanisms used by organizations to support the process of knowledge sharing and absorption. Some examples of the data obtained can provide an overview of the process of knowledge flow and the role of intermediaries during collaborative innovation activities. It can be seen in below.

Table 4. Example of exploring the bottom-up emergence of knowledge flow mechanisms in open innovation.

The table above shows the emergence of bottom-up organizational knowledge flows mechanisms during OI activities. The flow of knowledge in OI occurs through the process of sharing and absorbing knowledge both within internal teams and across organizations team. To maintain the flow of knowledge among team members (internal and cross-organizational teams), the role of intermediaries is needed so that barriers to the flow of knowledge (such as language differences, ways of working, geography, working methods, knowledge, and experience) can be minimized.

The process of knowledge flow in collaborative innovation through the process of knowledge sharing and absorption and the role of intermediaries will be described in the sections below.

4.1. Knowledge flow in open innovation

Based on the results, shows that there are certain mechanisms in the knowledge flow process between parties involved in open innovation. The three cases studied show several approaches that organizations take to support the flow of knowledge. For example, there is a mechanism that encourages the process of sharing knowledge among all parties involved. Likewise, there are mechanisms used for the knowledge absorption process so that it can support innovation.

The mechanism used to support the knowledge-sharing process between each party is to form a work team that supports OI activities. The team consists of an internal team consisting of internal members of the organization who are more focused on processing information and knowledge generated from collaborative innovation activities. While the cross-organizational team consists of a group of individuals who come from every organization involved in OI. This team is more focused on the process of sharing and absorbing information and knowledge contributed by each member. The team is also more focused on coordinating OI activities.

The formation of an internal team involves various competencies that are internally owned by the organization according to the needs of collaborative innovation. Individuals as knowledge carriers play a role in maintaining the flow of knowledge so that it can facilitate the accumulation of knowledge for use in problem-solving or innovation.

Meanwhile, cross-organizational teams involve a group of actors with different organizational backgrounds to support each other in the joint innovation process. The actors here act as intermediaries representing the internal organization’s team to connect with partners or external parties. The existence of intermediaries in this process facilitates the flow of knowledge among the organizations involved in collaborative innovation.

4.1.1. Knowledge sharing

This research shows that knowledge sharing conducted between team members is a form of contribution from each OI participant in developing joint products. Information, knowledge, and ideas flow between internal team members as well as cross-organizational teams through the process of sharing knowledge. For example, the thoughts given by each member to be used in innovation, such as progress reports are shared among members along with problems that have been identified and solutions that can be developed together. This is done with the intention of each party obtaining information and knowledge to produce a common understanding so that it can be the basis for following up on the innovation process.

4.1.1.1. Knowledge sharing in cross-organizational team member

The existence of cross-organizational teams facilitates the flow of knowledge between firms through sharing of knowledge. The team consists of a group of individuals who represent each organization in the innovation collaboration. In the three cases observed, cross-organizational team members are individuals who have roles as an organization’s boundary spanners who play a role in information exchange and access to clients and resources.

The knowledge-sharing process carried out in cross-organizational teams is more directed at sharing information and knowledge provided by each party (representing the organization) as a contribution to collaborative innovation. In this process, the information and knowledge that is shared help identify common needs to address the problem through the resulting innovations. The results of sharing information and knowledge in this section become input for the internal team of each organization to be followed up. For example, sharing ideas, information related to progress reports produced by each member, problems that have been identified, or solutions developed by the company’s internal team are shared in cross-organizational teams. A coordination process is also carried out on this team to build agreement and commitment between organizations.

Based on the three cases studied, the process of knowledge sharing in cross-organizational teams tends to be a formal, and scheduled and uses various media that have been agreed upon from the start. For example, by holding a meeting to discuss the problems faced either face-to-face or not. This is also supported by various communication media that can be used such as email or other media to support the knowledge-sharing process in this cross-organizational team.

4.1.1.2. Knowledge sharing between internal team member

The existence of an internal team is more directed at internal R&D activities to generate innovation. This team consists of a group of individuals who represent the various internal competencies to support the company’s innovation. Based on the three cases observed, cross-organizational team members are individuals with various competencies needed in developing new products.

The knowledge sharing among members of the internal team is also not much different from what is done in cross-organizational teams. The sharing process is carried out both formally and informally with various supporting media. However, in the internal team, the knowledge-sharing process is more directed at the process of sharing knowledge and information owned by each team member so that later it can be accumulated with various information and knowledge obtained from external parties. The more information and knowledge generated during collaborative innovation, it supports the process of developing solutions or innovations. In this process, the information and knowledge that is shared help to identify the problems and solutions through innovation development. The results of sharing information and knowledge in this section will be shared with cross-organizational teams.

4.1.1.3. Intermediaries role in knowledge sharing

Collaborative innovation activities will be followed by the emergence of a ‘pool of actors’ from different organizational backgrounds (such as work methods, work culture, geographic location, and other characteristics). In cross-organizational teams, these differences have the potential to become barriers to knowledge sharing. Thus, the role of intermediaries is needed in such a context to maintain knowledge sharing between the parties involved.

For example, in cases 1 and 2, there is a different background between the organizations. Such as, language and culture, geography, and differences in work methods and working hours. These differences have the potential to become an obstacle in the knowledge-sharing process during collaborative innovation (e.g. miscommunication or misperceptions). In this case, the existence of intermediaries who has a good understanding of cross-cultural and linguistics is very helpful to facilitate the process of sharing knowledge. The role of intermediaries in this case can minimize the occurrence of problems in the interaction process during the knowledge-sharing process. Thus, intermediaries not only bridge the knowledge-sharing process between organizations but also between teams (internal teams and cross-organizational teams).

4.1.2. Absorptive capacity

‘A basic sign of an absorptive capacity is an ability to accept the external knowledge, use it to create innovative solutions and to imitate other organizations’ (Lenart, Citation2014).

Absorptive capacity is the ability of innovating firms to assimilate and replicate new knowledge gained from external sources. The ability to recognize, value, and exploit external sources of knowledge, in general, explains an organization’s innovative capabilities (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990). The level of the organization’s absorbance depends on the absorptive capacity of its separate members (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990).

Based on the results of the study, it is shown that during OI, organizations also need absorption capacity to support innovation. Through this research, certain patterns are found that can describe the process of absorption of external knowledge to be used in innovation. This is in line with the explanation of the existing literature that inter-organizational knowledge flows do not materialize automatically (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990). In another word, the implementation of OI requires insourcing mechanisms, routines, and structures. Hence, OI implementation forces firms to develop new organizational routines to tap into external knowledge (Vanhaverbeke et al., Citation2008).

4.1.2.1. Absorptive capacity in cross-organizational team member

Based on the previous explanation, the existence of internal teams and cross-organizational teams are needed to help in the flow of knowledge during collaborative innovation. It not only helps in the knowledge-sharing process but also the knowledge-absorption process.

In cross-organizational teams, knowledge absorption is more directed at the acquisition and assimilation of knowledge provided by external parties. As found in the three cases studied, show that in cross-organizational teams, team members strive to acquire and understand valuable information and knowledge provided by partners. This is then followed up by the respective internal teams. For example, by holding regular meetings to exchange information and experiences related to new product development. This helps the identification process carried out by each member of the cross-organizational team to capture the need for innovation to be carried out. In addition, in the cross-organizational team, each member identifies the problems encountered in the development of new products. This needs to be done so that each member gains the same understanding to use in developing solutions so that a common understanding of the problems at hand is obtained.

4.1.2.2. Absorptive capacity in internal team member

The results of the study show that in collaborative innovation activities, the presence of individuals in the internal team reflects a collection of internal competencies needed in developing innovation. In the three observed cases, the existence of an internal team was more focused on the internal innovation activity itself rather than cross-organizational coordination activities.

The absorption of information and knowledge that occurs in the internal team is more directed at the process of knowledge transformation and exploitation. Based on the three cases studied, shows how internal team members combine existing knowledge with knowledge obtained from partners to use in generating innovations. For example, by holding intense meetings both formally and informally, to discuss solutions needed in new product development. Thus, the information, knowledge, and experience obtained from partners will be used together with existing knowledge and experience to generate innovation.

4.1.2.3. Intermediaries role in absorptive capacity

Just as intermediaries play a role in the knowledge-sharing process, so also intermediaries play a role in absorptive capacity. For example in case 1 or case 2, there are differences in background between companies such as geography, differences in work methods, and working hours. These differences have the potential to become obstacles in the process of absorbing knowledge. In this case, the existence of intermediaries can bridge the differences between the teams they face to minimize the occurrence of problems in the process of interaction and absorption of knowledge between organizations also between teams (internal teams and cross-organizational teams).

Based on the results, it shows that the process of absorption of knowledge occurs both in cross-organizational teams and in company internal teams. The existence of individuals in cross-organizational teams facilitates the process of absorbing knowledge from external parties to then be brought into the company’s internal team. Furthermore, the knowledge brought to the internal team will be absorbed and used by team members to develop problem-solving as part of the innovation process.

In collaborative innovation, individuals play a role in the process of acquiring new knowledge (Schuler et al., Citation2004). The existence of individuals in cross-organizational team also plays a role in monitoring and absorbing information and technical knowledge obtained from external parties to be later transformed into a form that can be understood by the group. They are also the ones who will absorb the knowledge generated in the internal team and then bring it back to the cross-organizational team. Through this research, it can be said that the process of absorbing knowledge and utilizing knowledge during the open innovation process requires an intermediary.

4.2. Toward a model of knowledge flow in collaborative innovation

Based on the previous explanation, the flow of knowledge in OI that is carried out through the process of sharing and absorbing knowledge can be seen in the below.

From , it can be understood how the flow of knowledge occurs in the internal team and the external team which is assigned by a cross-company team. The role of intermediaries in cross-organizational teams is crucial to maintaining the flow of knowledge between companies.

5. Discussion and implication

Knowledge flows are at the heart of open innovation. Therefore, knowledge sharing and knowledge absorption are two important concepts in understanding knowledge flow. Researchs on knowledge sharing and absorption mechanisms therefore has the potential to strengthen our understanding of knowledge flows in open innovation.

Even though most studies dealing with knowledge sharing and absorptive capacity tend to regard one as the antecedent of the other (Szulanski, Citation1996). But apart from that, knowledge sharing will always be associated with absorptive capacity. We argue that the accumulation of knowledge causes individuals to learn to share it more effectively and that sharing leads to the accumulation of knowledge.

In this research, the results show how knowledge moves between individuals, groups and organizations. This explains how the flow of knowledge occurs through a reciprocal mechanism of sharing and absorbing knowledge carried out by each member involved. The flow of knowledge that is reflected through the process of sharing and absorbing knowledge forms a kind of spiral of knowledge that will accumulate along with the activities of sharing and absorbing knowledge. This is in line with Engelsberger et al. (Citation2022) who conceptualize the mutual inflow (sourcing) and outflows (sharing) of knowledge that occurs at the employee level or/and at the organizational level, which ultimately driving OI performance (Engelsberger et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, managing unconstrainted knowledge flows can enhance collective thinking, spur the application and utilization of knowledge, and develop companies’ innovative responses to environmental challenges. Thus, the free flow of knowledge between individuals and groups has an impacts innovation (Kang et al., Citation2007; Mabey et al., Citation2015; Wei et al., Citation2011).

However, previous research found that there were obstacles in the process of knowledge flow (for example way of working, working hours, geographical location or others) (Ardichvili et al., Citation2003). In that case, intermediaries are needed to maintain the flow of knowledge between the parties involved. The research results show how cross-organizational teams facilitate team members who have an intermediary role in the flow of knowledge across individuals, groups and organizations. The existence of intermediaries can reduce the obstacles faced in distributing individual ideas and become an effective way of managing organizational knowledge (Cabrera & Cabrera, Citation2002; Sung & Choi, Citation2018). So far, this research is still limited to the mechanisms of knowledge flow in OI, it is still necessary to further investigate the capabilities that actors must have.

5.1. Theoretical implication

This paper proposes an understanding of knowledge flow in open innovation through an exploration of the organizational mechanisms used in the process of knowledge sharing and absorption. The results seem to show the real contribution of the knowledge flow process through knowledge sharing and absorption capacity involving internal teams and cross-organizational teams. Furthermore, to improve the flow of knowledge, the role of intermediaries is needed in maintaining the flow of knowledge during the open innovation process. Consequently, the presence of intermediaries in a collaborative innovation context can enrich the reconceptualization of absorptive capacity that has been previously developed by Zahra and George (Citation2002) and becomes part of the knowledge flow mechanism in a cross-organizational context (Zahra & George, Citation2002).

Likewise, Lopez’s literature review shows that the flow of knowledge has a crucial role in achieving OI success, but attention is more focused on skills and AC (Lopes & de Carvalho, Citation2018). There is still a lack of attention to the knowledge sharing process and AC as well as the role of intermediaries in knowledge flow. Through this empirical study, we explore the knowledge flow through the process of knowledge sharing and absorptive capacity while providing evidence that the intermediaries are significant to support knowledge flow in the context of collaborative innovation.

5.2. Practical implication

The finding provides valuable insights for managers who may be particularly working across country or cultural contexts with suppliers, partners, or other external entities in managing collaborative innovation activities. This study also takes a nuanced approach by studying the role of actors as intermediaries in knowledge-sharing mechanisms and absorptive capacity in cross-organizational teams.

From practitioners’ perspective, the finding of this study can help managers do better in acquiring and using the internal and external resources available in any form (knowledge, ideas, human resources, etc). Managers can accordingly benefit by building and encouraging their subordinates to build strong connections/bonds/ties with managers of other organizations and universities/research centers/government representatives. By adopting a collaborative approach and the two-way exchange of knowledge and other valuable resources, managers can build valuable networks to support their organizations’ innovation-related goals.

By understanding that innovation can be described as an information-creation processes that arises out of social interaction (Gutmann et al., Citation2023). These interactions provide the opportunity for thoughts, potential ideas, and view to be shared and exchanged. Furthermore, the proper placement of managers can be a bridge in building the flow of knowledge both inside and outside the organization to support innovation. Managers who have good relations with other organizations, it has an impact on the process of obtaining and using external knowledge resources for innovation (Naqshbandi & Kamel, Citation2017).

5.3. Limitation and future research

One of the challenges faced in open innovation activities is the willingness of each party to develop and implement the innovations that have been produced. It’s not a simple thing to do. Therefore the risk of failure in the collaborative innovation process is very likely to occur. For example, the emergence of opportunistic behavior or being more concerned with their own goals so that individuals or companies can enter and leave the team at any time.

The complexity of the elements of the process in innovation collaboration between organizations requires a micro foundation approach so that the dynamics between individuals and groups that affect organizational-level results and performance can be well understood (Abell et al., Citation2008). Mäkimattila et al. (Citation2013), for example, have paid attention to the existence of actors in open innovation (Mäkimattila et al., Citation2013). However, how multi-actor interactions with multi-identities are involved in open innovation is still not considered in this study and needs to be investigated further. Therefore, future research needs to use a micro-foundation approach. For example, using a social identity perspective to gain a more detailed and integrated understanding of how HRM practices can build social integration in the OI process.

6. Conclusion

OI is an alternative for companies to access knowledge and external competencies to support the company’s innovation process. Building relationships between organizations can be an infrastructure for the flow of knowledge both inside and outside the organization. In addition, the relational capacity possessed can help assess external resources that can be integrated with internal knowledge or competencies (Lichtenthaler, Citation2010). Integrating diverse but relevant expertise can help in creating ideas for new products (Dodgson et al., Citation2006).

Furthermore, having a relational capacity of employees can help in assessing external resources that can be integrated with their knowledge base or internal competence (Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, Citation2009). Integrating diverse but relevant expertise can help in the creation of ideas for new products (Dodgson et al., Citation2006). Relational capacity is needed especially for individuals as gatekeepers and boundary-spanners who play a role in the process of acquiring new knowledge (Schuler et al., Citation2004).

Referring to the research results, the existence of intermediaries in the flow of knowledge does not only bridge the differences, but more than that, intermediaries are individuals who build relationships between individuals and between organizations earlier before the knowledge exchange process takes place. Based on the existing literature, it is explained that the process of knowledge transfer occurs easily in a strong social bond between members (Reagans & McEvily, Citation2003). Unfortunately, not much literature discusses how HRM as an organizational mechanism plays its role support in collaborative innovation implementation.

In the context of collaborative innovation, social integration mechanisms can have an impact on the absorption of knowledge by organizations (Björkman et al., Citation2007). This occurs because social integration contributes to the process of assimilation of knowledge, either through informal mechanisms (using social networks) or formal (using coordinators).

However, it is not immediately apparent, research that explains the process of multi-actor interaction with different abilities and organizational backgrounds is involved in the dynamic implementation of OI. This needs to be studied more deeply because the success of OI depends on the process of transfer and absorption of knowledge between individuals and groups. The existence of internal and independent workers in the context of collaborative innovation requires appropriate HRM practices.

Project-based job design tends to be temporary and very specific making the role of the HR function shift from HR specialist managers to innovation project managers or non-HR specialist managers. Therefore, they are not only required to have technical competence related to projects but are also required to carry out HR functions that are not simple.

Informed consent statement

All respondents provided informed consent before answering questions.

Institutional review board statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to all respondents provided informed consent before answering questions.

public interest statement.docx

Download MS Word (13.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tutuk Ari Arsanti

Tutuk Ari Arsanti is an Assistant Professor at Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Satya Wacana Christian University, Indonesia. She is active as an academic researcher. Her research interests are HRM, innovation, behavioral, and organizational. She has published many publications in various outlets.

Neil Rupidara

Neil Semuel Rupidara is an Associate Professor from Bhakti Semesta Polytechnic, Indonesia. He is active as an academic researcher. His research interests are international HRM, leadership, and organizational institutionalism. He has published journal articles and book chapters, also presented papers in conferences.

Tanya Bondarouk

Tanya Bondarouk is a Professor of Human Resource Management at the University of Twente, the Netherlands. Her main publications concern an integration of Human Resource Management and social aspects of Information Technology implementations.

References

- Abell, P., Felin, T., & Foss, N. (2008). Building micro-foundations for the routines, capabilities, and performance links. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1413

- Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250961

- Andreeva, T., & Kianto, A. (2011). Knowledge processes, knowledge‐intensity and innovation: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(6), 1016–1034. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271111179343

- Ardichvili, A., Page, V., & Wentling, T. (2003). Motivation and barriers to participation in virtual knowledge-sharing communities of practice. Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(1), 64–77.

- Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2893

- Argote, L., McEvily, B., & Reagans, R. (2003). Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes. Management Science, 49(4), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.49.4.571.14424

- Balle, A. R., Oliveira, M., & Curado, C. M. M. (2020). Knowledge sharing and absorptive capacity: Interdependency and complementarity. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(8), 1943–1964. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2019-0686

- Barney, J., & Felin, T. (2013). What are microfoundations? Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0107

- Bengoa, D. S., & Kaufmann, H. R. (2014). Questioning western knowledge transfer methodologies: Toward a reciprocal and intercultural transfer of knowledge. Thunderbird International Business Review, 56(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21593

- Bigliardi, B., Ferraro, G., Filippelli, S., & Galati, F. (2021). The past, present and future of open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(4), 1130–1161. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-10-2019-0296

- Björkman, I., Stahl, G. K., & Vaara, E. (2007). Cultural differences and capability transfer in cross-border acquisitions: The mediating roles of capability complementarity, absorptive capacity, and social integration. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 658–672. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400287

- Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G., & Lee, J. N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669

- Bogers, M. (2011). The open innovation paradox: Knowledge sharing and protection in R&D collaborations. European Journal of Innovation Management, 14(1), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061111104715

- Bogers, M., Foss, N. J., & Lyngsie, J. (2018). The “human side” of open innovation: The role of employee diversity in firm-level openness. Research Policy, 47(1), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.10.012

- Buckley, P. J., & Carter, M. J. (2004). A formal analysis of knowledge combination in multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400095

- Cabrera, A., & Cabrera, E. F. (2002). Knowledge-sharing dilemmas. Organization Studies, 23(5), 687–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840602235001

- Chauvel, D. (2016). Knowledge as both flows and processes. Proposed by GeCSO 2013 conference committee. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 14(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2016.1

- Chen, C.-J., & Huang, J.-W. (2009). Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. Journal of Business Research, 62(1), 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.11.016

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business School Press.

- Chesbrough, H., & Bogers, M. (2014). Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation. Oxford University Press, Forthcoming (pp. 3–28).

- Cleveland, S., Mitkova, L., & Goncalves, L. C. (2015). Knowledge flow in the open innovation model the effects of ICT capacities and open innovation practices on knowledge streams [Paper presentation]. SoutheastCon 2015, pp. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1109/SECON.2015.7133033

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive cpacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

- Daghfous, A., & Ahmad, N. (2015). User development through proactive knowledge transfer. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 115(1), 158–181. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2014-0202

- Dahlin, P., Moilanen, M., Østbye, S. E., & Pesämaa, O. (2020). Absorptive capacity, co-creation, and innovation performance: A cross-country analysis of gazelle and nongazelle companies. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(1), 81–98.

- Dodgson, M., Gann, D., & Salter, A. (2006). The role of technology in the shift towards open innovation: The case of Procter & Gamble. R and D Management, 36(3), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2006.00429.x

- Donate, M. J., Peña, I., & Sánchez de Pablo, J. D. (2016). HRM practices for human and social capital development: Effects on innovation capabilities. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(9), 928–953. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1047393

- Engelsberger, A., Halvorsen, B., Cavanagh, J., & Bartram, T. (2022). Human resources management and open innovation: The role of open innovation mindset. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 60(1), 194–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12281

- Enkel, E., Gassmann, O., & Chesbrough, H. (2009). Open R&D and open innovation: Exploring the phenomenon. R&D Management, 39(4), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2009.00570.x

- Gertner, D., Roberts, J., & Charles, D. (2011). University‐industry collaboration: A CoPs approach to KTPs. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(4), 625–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271111151992

- Gulati, R., & Singh, H. (1998). The architecture of cooperation: Managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 781. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393616

- Gutmann, T., Chochoiek, C., & Chesbrough, H. (2023). Extending open innovation: Orchestrating knowledge flows from corporate venture capital investments. California Management Review, 65(2), 45–70.

- Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484303257985

- Kang, S.-C., Morris, S. S., & Snell, S. A. (2007). Relational archetypes, organizational learning, and value creation: Extending the human resource architecture. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23464060

- Kim, A., Kim, Y., Han, K., Jackson, S. E., & Ployhart, R. E. (2017). Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. Journal of Management, 43(5), 1335–1358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314547386

- King, W. R. (Ed.). (2009). Knowledge management and organizational learning (Vol. 4). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0011-1

- Lane, P. J., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19(5), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199805)19:5<461::AID-SMJ953>3.0.CO;2-L

- Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27(2), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.507

- Le, H. T. T., Dao, Q. T. M., Pham, V.-C., & Tran, D. T. (2019). Global trend of open innovation research: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1633808. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1633808

- Lenart, R. (2014). Operationalization of absorptive capacity. International Journal of Contemporary Management, 13(3), 86–98.

- Liao, S., Fei, W.-C., & Chen, C.-C. (2007). Knowledge sharing, absorptive capacity, and innovation capability: An empirical study of Taiwan’s knowledge-intensive industries. Journal of Information Science, 33(3), 340–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551506070739

- Liao, S., Wu, C., Hu, D., & Tsui, K. (2010). Relationships between knowledge acquisition, absorptive capacity and innovation capability: An empirical study on Taiwan’s financial and manufacturing industries. Journal of Information Science, 36(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551509340362

- Liao, Y., & Barnes, J. (2015). Knowledge acquisition and product innovation flexibility in SMEs. Business Process Management Journal, 21(6), 1257–1278. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-05-2014-0039

- Lichtenthaler, U. (2010). Notice of retraction: Outward knowledge transfer: the impact of project-based organization on performance. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(6), 1705–1739. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtq041

- Lichtenthaler, U., & Lichtenthaler, E. (2009). A capability-based framework for open innovation: Complementing absorptive capacity. Journal of Management Studies, 46(8), 1315–1338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00854.x

- Lopes, A. P. V. B. V., & de Carvalho, M. M. (2018). Evolution of the open innovation paradigm: Towards a contingent conceptual model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 132, 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.02.014

- Lopez, V. W. B., & Esteves, J. (2013). Acquiring external knowledge to avoid wheel re‐invention. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271311300787

- Lopez-Cabrales, A., Pérez-Luño, A., & Cabrera, R. V. (2009). Knowledge as a mediator between HRM practices and innovative activity. Human Resource Management, 48(4), 485–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20295

- Mabey, C., Wong, A. L. Y., & Hsieh, L. (2015). Knowledge exchange in networked organizations: Does place matter? R&D Management, 45(5), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12099

- Mäkimattila, M., Melkas, H., & Uotila, T. (2013). Dynamics of openness in innovation processes-a case study in the Finnish food industry: Dynamics of openness in innovation processes. Knowledge and Process Management, 20(4), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1421

- Mazzola, E., Perrone, G., & Kamuriwo, D. S. (2015). Network embeddedness and new product development in the biopharmaceutical industry: The moderating role of open innovation flow. International Journal of Production Economics, 160, 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.10.002

- Meyer-Krahmer, F., & Schmoch, U. (1998). Science-based technologies: University–industry interactions in four fields. Research Policy, 27(8), 835–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00094-8

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft. Educational Researcher, 13(5), 20–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1174243 https://doi.org/10.2307/1174243

- Mowery, D. C., Oxley, J. E., & Silverman, B. S. (1996). Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledge transfer. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171108

- Naim, M. F., & Lenkla, U. (2016). Knowledge sharing as an intervention for Gen Y employees’ intention to stay. Industrial and Commercial Training, 48(3), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-01-2015-0011

- Naqshbandi, M. M., & Kamel, Y. (2017). Intervening role of realized absorptivecapacity in organizational culture–openinnovation relationship: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of General Management, 42(3), 5–20.

- Natalicchio, A., Ardito, L., Savino, T., & Albino, V. (2017). Managing knowledge assets for open innovation: A systematic literature review. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(6), 1362–1383. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2016-0516

- Ogink, R. H. A. J., Goossen, M. C., Romme, A. G. L., & Akkermans, H. (2023). Mechanisms in open innovation: A review and synthesis of the literature. Technovation, 119, 102621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102621

- Özbağ, G. K., Esen, M., & Esen, D. (2013). The impact of HRM capabilities on innovation mediated by knowledge management capability. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99, 784–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.550

- Reagans, R., & McEvily, B. (2003). Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(2), 240–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/3556658

- Schmidt, T. (2009). Absorptive capacity-one size fits all? A firm-level analysis of absorptive capacity for different kinds of knowledge. Managerial and Decision Economics, 31(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1423

- Schuler, R. S., Tarique, I., & Jackson, S. E. (2004). Managing human resources in cross-border alliances. In Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions (Vol. 3; pp. 103–129). JAI Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-361X(04)03005-4.

- Shi, X., Lu, L., Zhang, W., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Managing open innovation from a knowledge flow perspective: The roles of embeddedness and network inertia in collaboration networks. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(3), 1011–1034. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-07-2019-0200

- Song, J. (2014). Subsidiary absorptive capacity and knowledge transfer within multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.55

- Sun, P. Y. T., & Anderson, M. H. (2008). An examination of the relationship between absorptive capacity and organizational learning, and a proposed integration: Absorptive capacity and organizational learning. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00256.x

- Sung, S. Y., & Choi, J. N. (2018). Building knowledge stock and facilitating knowledge flow through human resource management practices toward firm innovation. Human Resource Management, 57(6), 1429–1442. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21915

- Swift, P. E., & Hwang, A. (2013). The impact of affective and cognitive trust on knowledge sharing and organizational learning. The Learning Organization, 20(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696471311288500

- Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm: Exploring Internal Stickiness. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171105

- Tsai, W. (2001). Knowledge transfer in intraorganizational networks: Effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 996–1004. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069443

- van den Hooff, B., & de Ridder, J. A. (2004). Knowledge sharing in context: The influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(6), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270410567675

- van Wijk, R., Jansen, J. J. P., & Lyles, M. A. (2008). Inter- and intra-organizational knowledge transfer: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 830–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00771.x

- Vanhaverbeke, W., Van de Vrande, V., & Cloodt, M. (February 7, 2008). Connecting absorptive capacity and open innovation. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1091265 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1091265

- von Briel, F., Schneider, C., & Lowry, P. B. (2019). Absorbing knowledge from and with external partners: The role of social integration mechanisms: Absorbing knowledge from and with external partners. Decision Sciences, 50(1), 7–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12314

- Wang, C., Rodan, S., Fruin, M., & Xu, X. (2014). Knowledge networks, collaboration networks, and exploratory innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 484–514. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0917

- Wang, Z., & Wang, N. (2012). Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Systems with Applications, 39(10), 8899–8908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.017

- Wei, J., Zheng, W., & Zhang, M. (2011). Social capital and knowledge transfer: A multi-level analysis. Human Relations, 64(11), 1401–1423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711417025

- West, J., & Bogers, M. (2017). Open innovation: Current status and research opportunities. Innovation, 19(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2016.1258995

- West, J., & Gallagher, S. (2006). Challenges of open innovation: The paradox of firm investment in open-source software. R and D Management, 36(3), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2006.00436.x

- Yun, J., Jeon, J., Park, K., & Zhao, X. (2018). Benefits and costs of closed innovation strategy: Analysis of Samsung’s galaxy note 7 explosion and withdrawal scandal. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 4(3), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4030020

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. The Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134351

- Zhuge, H. (2002). A knowledge flow model for peer-to-peer team knowledge sharing and management. Expert Systems with Applications, 23(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0957-4174(02)00024-6