Abstract

Informal social and economic systems of kinship, labour relations, child fostering, food sharing and shelter sharing have characterized African societies. These arrangements have played significant roles in household risk management in Ghana in previous times and are still relevant in the management of economic hardships. Within the context of rapid globalisation and modernisation, these social and economic arrangements have changed over time, with some dire ramifications including economic hardships. Using secondary data consisting of literature sources, this paper examines these informal social and economic systems, highlighting their underlying concepts, transformations, and relevance in the prevention and management of risks associated with care, labour, and poverty. The author finds reciprocity and solidarity as the dominant underlying concepts of the social and economic systems understudied. Further, there were transformations in these arrangements contributed by factors, such as scarcity of resources, modernisation, weakening of kinship ties, unmanaged urbanisation, economic monetisation, and economic development. The paper recommends the incorporation of underlying concepts, such as reciprocity and solidarity in social protection policies for sustainable management of risks and economic hardships in the future. This will support poverty reduction efforts and the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goal 1 (SDG1).

1. Introduction

In many developing countries, managing economic hardship and risks of various kinds have been conducted mainly within informal social and economic systems that are supported by familial and kinship relations. Economic hardships and risks were managed through gifts, transfers, and informal loans between households and close relatives (Fafchamps & Gubert, Citation2007; Fafchamps & Lund, Citation2003; Rosenzweig, Citation1988; Rosenzweig & Stark, Citation1989). Labour pooling relations (Krishnan & Sciubba, Citation2004) and child fostering (Akresh, Citation2004; Evans & Miguel, Citation2007), shelter provision and support for new migrants (Granovetter, Citation2000), and food transfer between households (Ambrus et al., Citation2010; Bhattamishra & Barret, Citation2010), also helped to reduce economic hardship and have served as safety nets. Informal social systems, such as funeral societies (Dercon et al., Citation2006; Mariam, Citation2003), rotating savings and credit associations, and credit cooperatives (Besley, Citation1995) are all avenues of managing risks associated with life cycle events and managing economic hardship.

These arrangements and systems have been a source of attraction to various disciplines of researchers, such as Anthropologists, Sociologists, and Economists. These arrangements and systems are usually described as non-market and make little use of formal contractual arrangements that need to be codified through a legal system (Besley, Citation1995). Fafchamps (Citation1992) and Dercon et al. (Citation2006) described them as informal, traditional, or preindustrial, while Booth (Citation1994) described them as premarket institutions. These systems are based on moral obligations and operate with the moral economy or community (Fafchamps, Citation1992; Tufuor et al., Citation2015). In this paper, the author refers to all such arrangements and systems in this range as informal systems.

While these systems address specific risks that may be social or economic in nature, they have the potential to provide support during economic hardships. Economic hardships resulting from macroeconomic crisis is experienced differently by developing countries where State Welfare support is limited. In Africa for instance, several strategies are adopted during economic crises at both the individual and collective level to attain survival (Garuba, Citation2006), while in Western economies, State welfare benefits provide support during economic hardships (Obert et al., Citation2018). In the absence of State welfare benefits, the dependence on informal social and economic systems that offer resource redistribution could be of help in present times of economic hardship aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent Russia–Ukraine war (Rabbi et al., Citation2023). Even in developed economies with State welfare support, such systems also help in providing resilience in the face of economic hardship through ties with families, friends, colleagues, and churches that offer immaterial support (Reeskens & Vandecasteele, Citation2017).

Studies are already showing a decline in these informal systems (Aboderin, Citation2004a; Maclean, Citation2010). There are also transformations in some of these systems as they evolve in adjustment to changes in society (Amanor & Diderutuah, Citation2001; Baah & Kidido, Citation2020). While the modern versions of these systems continue to offer some social and economic support in times of economic hardship, it is necessary to revisit their underlying concepts and also analyse their transformation and the implications for managing economic hardship. Studies on specific informal social and economic systems in Ghana are lacking. Existing studies have either focussed on the economics of risk-sharing, such as the efficiency of risk-sharing (Fafchamps, Citation2011) the structure of networks (Bourlès et al., Citation2021), the sustainability of such arrangements and enforcement mechanisms (Dercon et al., Citation2006). This paper reviews and analyses six informal social and economic systems in Ghana. The paper further discusses their underlying concepts and their transformations and implications for managing economic hardship within the context of poverty reduction in in present times of limited State welfare support. While this knowledge contributes to the literature on informal social and economic systems from the Ghanaian perspective, it also provides insights for managing economic hardship in the future. The remaining part of this paper consists of the methodology, the results and discussion, the policy implications, conclusions, and policy recommendations.

2. Methodology

This study is a literature review that employs the integrative review approach. The aim of integrative review is to provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. It makes use of diverse sources of secondary data with diverse sources of designs (Oermann & Knafl, Citation2021). In this study, both empirical and theoretical literature sources were used to understand the phenomenon of informal care and support within the context of poverty reduction. This study dwelt on the framework for integrative review developed by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005). This framework consists of five processes namely problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation of findings.

In concretising the problem for the study, the following research question was the focus ‘What are the underlying concepts of informal systems of care and support? What lessons can be drawn from them for managing economic hardships in recent times? To what extent have they changed over time?’

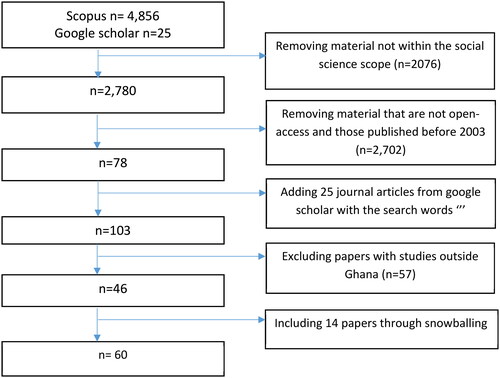

In the literature search on the Scopus database, using the keywords informal social and economic systems and economic hardships, 4856 items were retrieved. Due to the nature of the study, not much of the literature obtained in this manner was helpful and was excluded through filtering to maintain material within the social science scope. Thus 2780 journal articles and books were maintained. Upon further filtering to obtain open access material and sources published before 2003, 78 articles, review articles, and books were obtained. An additional 25 articles were included from google scholar, making a total of 103 journal articles and books. A review of these sources of literature led to the identification of the scope of informal systems of support and care available in developing countries. These are burial societies, kinship norms, labour relations, child care, and support (child fostering), shelter sharing, food sharing, and information sharing. However, as the focus of the study was Ghana, 57 studies from countries aside from Ghana were excluded from the review, maintaining a total of 46 journal articles and books. In addition, due to limited studies on burial societies and information sharing in Ghana, these themes were excluded from the study. These 46 journal articles and books were used for the review and through snowballing and an iterative process, 10 relevant articles cited by some authors were searched, and included these sources were also included in the study, making a total of 56 journal articles and books. presents a chart showing the process of selection and exclusion of material.

The quality of each literature was evaluated and high quality literature was given much focus as the main sources of data. Eventually, a total of 56 literature materials were used. The literature was analysed and the findings that address the research problem and research questions were extracted from the literature. Findings on the underlying concepts of kinship norms, informal labour relations, child fostering, shelter sharing, and food sharing within the contexts of managing economic hardships and poverty reduction were extracted from the literature.

3. Findings

3.1. Informal social and economic systems in Ghana

In Ghana, various forms of informal systems of social and economic relations which help individuals and groups to mitigate risks have been in existence from prehistoric times and these are reflected in norms and customs across various ethnic groups in Ghana (Awedoba, Citation2005). Child fostering (Klomegah, Citation2000; Kuyini et al., Citation2009), labour pooling (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, 1995) food sharing (Atobrah, Citation2014), are all practices that have been in existence since prehistoric times. In Ghana, these informal institutions are usually enforced by the traditional norms of many ethnic groups which support the notion of helping kinsmen in need and perceive it shameful when wealthy kinsmen refuse to support others in need.

Reciprocity has been a major driving force in informal relations of the Ghanaian culture and the readiness to offer emotional, moral, and financial support to relatives in times of trouble and during life cycle events is well documented in literature (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Manful & Cudjoe, Citation2018; Nukunya, Citation2016). In many traditional societies, human settlements are set-up in a manner to encourage constant interaction with extended family members. I illustrate specific social and economic relations and activities which provide support to parties and analyse the underlying concepts of these relations.

3.1.1. Informal economic systems of care and support: labour pooling and share tenancy

In the informal labour market, labour pooling is an informal avenue of managing risk. Despite criticisms from Economists concerning inefficiencies in informal labour market arrangements, they have supported labour efforts in times past and have contributed to the success of the cocoa economy in Ghana (Boadu, Citation1992). These economic arrangements, which are losing relevance are worth reviewing. Labour arrangements among fisher folk in the Coastal zones of Ghana (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995) and crop farmers particularly in the cocoa sub-sector (Robertson, Citation1982) are typical examples of avenues of support that results in economic gains. In such labour arrangements, kinship plays an important role.

Among the Ga-Dangme fisher folk in the coastal parts of Ghana, the whole space of artisanal marine fisheries used to be organized around kinship norms. There has been the dependence of family members for labour, financing, and sustenance of the fishing business. On another hand, family members also benefit from canoe owners engaged in fishing known as the owners of capital. With this informal system of labour relations, family members are secured as they obtain a source of livelihood, and there is labour pooling when they all go fishing together. In the case of illness where the wealthy kinsman is unable to go fishing, the family members will go fishing on his behalf and provide him with some revenue. Bortei-Doku Aryeetey (Citation1995) likened this labour relation to a Marxist social relation where the owners of capital seek to offer support to other family members who do not own capital but have the manpower and are not skillful. Here, the family members known as workers are offered informal training in the fishing trade and provided with a source of livelihood. Bortei-Doku Aryeetey (Citation1995), also noted that the owners of capital also ensured family members benefitted from employment with other business partners along the fish value chain. They directed their trading customers, such as fish smokers and traders to employ their family members in their businesses. Here, I see a fusion of kinship and economic relations.

The female family members were also not left out of the system. Whenever the crew returned from fishing, the wives and other female family members were the first to be supplied with fish for sale before selling to other buyers. Usually, for kinsmen, the fish is provided on credit while for non-kinsmen, payment is expected before the fish is supplied. With time, the female family members are able to build up their financial resources through consistent trading to the extent of providing credit to the male canoe owners to fuel the canoe (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995). Through this system, the females who do not have initial capital to trade receive trade support. This alleviates poverty and the consequences of economic hardship.

Share tenancy is another informal system of economic relations practiced in Ghana. This typically occurs in crop farming communities and typically in the cocoa industry. The tenancy agreement is made informally between the owner of land and the tenant, who works on the land. Six kinds of labour contracts exist in the cocoa industry in Ghana. These are the Abusa, Nkotokuano, daily labourer, contract labourer, dual rate, and land compensation arrangements (Boadu, Citation1992). The most common is Abusa (Boadu, Citation1992; Robertson, Citation1982). Abusa simply means one-third in the Twi language but also has an important meaning in the cocoa industry. It represents a crop sharing arrangement whereby the harvested crops are divided in three parts. The sharing ratio depends on the type of share tenancy. If the share tenancy is an abusa labourer arrangement, the supplier of labour and other inputs, known as the abusa man receives a third of the cocoa produced in each season from the farm owner. Alternatively, if the share tenancy is an abusa tenant arrangement, the abusa man takes two thirds of the proceeds of the farm (Robertson, Citation1982; Baah and Kidido, Citation2020). Robertson (Citation1982), notes that in the early days of practicing abusa, outright ownership of land was given to tenants overtime. However, in the latter days, there were restrictions on access to land by tenants.

3.1.2. Informal social systems of support and care based on kinship norms

In Ghana, the traditional norms of many ethnic groups support the notion of helping kinsmen in need and it is deemed shameful when wealthy kinsmen refuse to support other kinsmen in need. Kinship norms fuelled by reciprocity have been the backbone of the Ghanaian culture (Manful & Cudjoe, Citation2018; Nukunya, Citation2016). The readiness to offer emotional, moral, and financial support to relatives in times of trouble and life cycle events is well documented in the literature (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006). These acts of kindness serve as risk reduction elements during economic hardship and in situations where the act of kindness is reciprocated, it deepens kinship ties. In Ghana, many informal systems have been built on kinship norms.

In matrilineal Akan societies for instance, through kinship norms of patronage, a historical strong relationship is built between uncles and their nephews and nieces. Matrilineal kinship norms require that an uncle, referred to as wofa will take care of the needs of the children of his sister in addition to the needs of his own children. It is expected of the uncle to bequeath his assets to the nephews and nieces (Kutsoati & Morck, Citation2016; La Ferrara, Citation2007). Traditionally his own children are not considered to be his blood kin but rather the children of his sister. The nephews and nieces are also expected to take care of their uncle when he is aged. In situations where the biological parents of the nephew are experiencing economic hardship, the support received through this kinship norm is invaluable. Through the dependence on kinship relations, some nephews have received support from their uncles to suppport their farming activities in the 1980s when cocoa farms were engulfed by bushfires as a result of prolonged droughts. Uncles in urban centres provided financial resources to their nephews to engage in tomato farming (Maclean, Citation2010, p. 17). This not only provided alternative livelihood sources but also enabled them to circumvent economic hardship.

La Ferrara (Citation2007) also shows another dimension of this social norm. She provides evidence of high rates of transfers from children of Akan descent to their fathers. This occurred particularly among households with nephews. She also noted that the presence of co-resident nephews increased the likelihood of receiving transfers from biological children. The author interpreted this as a response to the threat of disinheritance and to induce the bequeathal of cocoa farms to biological children rather than nephews. Thus biological children increased transfers to their parents during their lifetime to induce the donation of assets before the default inheritance is enforced. Thus the insurance notion underpins transfers by children to parents in households with coresident nephews.

3.1.3. Informal social institution of care and support—child fostering

Child fostering is an informal social system of child support common to African countries which is practiced in Ghana. Child fostering represents the practice of transferring care responsibility of a child to non-biological parents (Affum, Citation2019; Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Serra, Citation2009). This is reversible and differs from adoption (Serra, 2009). Children are fostered out to live with surrogate parents in the event of family crises or when the biological parents are unable to care for them. It is noted to have been practiced by all socio-economic groups whether rich or poor, urban, or rural. The foster children may also be healthy or handicapped (Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation1985; Klomegah, Citation2000). Thus, the determinants of child fostering are not distinct. However, reasons, such as child orphanage, illness and/or separation of parents, mutual help, socialization, education, and ritual guardianship have influenced fostering (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Cassiman, Citation2010; Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation1985). Further the need to strengthen extended family ties, redistribute child labour, and taking advantage of informal insurance mechanisms embedded in child fostering drives child fostering in African economies.

Based on the purpose of fostering, three types of fostering have been identified across West Africa by Klomegah (Citation2000), namely crisis fostering, alliance and apprentice fostering, and domestic fostering. Crisis fostering occurs when parents are divorced, separated, or in the situation of the death or illness of a parent or both parents. Both maternal and paternal family members decide on the family that can give a better upbringing and protection to the child (Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation1985). Crisis fostering usually engages kinsmen as foster parents and there could be instances where the foster parents are not in favour of the task of fostering (Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014). In Ghana, among the Krobos, crisis fostering also involves the community, where non-kinsmen are engaged as foster parents in the event of the death of both parents of children through HIV/AIDS (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006). The main purpose of crisis fostering is the welfare of the child. However, the foster parents also benefit from the services of the child through errands and house chores. The underlying concept of crisis fostering, whether by kinsmen or non-kinsmen is sympathy and altruism (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006).

In alliance and apprenticeship fostering, the parents send the child to live with non-relatives and acquaintances as a symbol of social, economic, and political alliances. The main purpose is to enable the child to learn a trade and some skills from the foster parents and to enable the social mobility of the child. The choice of foster parents depends on the social status and ability to groom the child (Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation1985; Klomegah, Citation2000). Alliance and apprenticeship fostering is a kind of non-kinship fostering.

In domestic fostering, children are sent out to provide services and household chores in certain homes. These may be homes of kinsmen or non-kinsmen. The purposes of domestic fostering include the benefit of the services of the children and the grooming of the children to play domestic roles effectively. The focus of domestic fostering is usually the girl child who is groomed to be a good wife in the future. In this case, the child is sent away to be fostered by an experienced wife. Domestic fostering also involves the act of sending children away to live with childless couples to give emotional support (Klomegah, 2000). Within the context of economic hardship, the biological parents of fostered children are relieved of financial burden and the care and educational needs of the child are met. The underlying concept of domestic fostering is reciprocity.

In Ghana, before colonial rule, there was a traditional system of care which requires that care and protection of children be carried out through the extended family and other kinship networks. It was common for parents who faced economic hardship to place their children with extended family members. In situations where the parents of the child are deceased, the family members willingly accept to foster the child for the fear of reprisal from the dead kinsmen (Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014). More so, among many ethnic groups, there was a strong sense of community ownership of children, and this made child fostering easy among kinsmen and non-kinsmen. There was also a high incidence of child mortality, and everyone in the community contributed to provide care for the child to avoid any loss of lives through any child (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006). In Northern Ghana, child fostering was commonly practiced among the Dagombas who held a strong belief that children are gifts from God, and it is the communal responsibility of all extended family members to bring up the child. Consequently, children are sent to uncles and aunties and in some cases, distant cousins to take care of them (Affum, Citation2019; Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014; Kuyini et al., Citation2009).

Using a case of the Gonjas, three types of fostering have been identified in Ghana, namely kinshi from the dead kinsmen p fostering, voluntary fostering, and crisis fostering Goody (Citation1982). Kinship fostering engages kinsmen and relatives as foster parents. Voluntary fostering occurs when biological parents decide to send out their own children into fostering. This occurs when parents are going through economic hardships and have financial difficulties in taking care of their children. It could also be that the parents are travelling for short or long periods and would need someone to take care of their children. Other reasons for voluntary fostering include child education and vocational purposes, where there are no schools in the area where the parents lived. Voluntary fostering also includes the situation where foster parents volunteer to take care of other children in addition to their biological children (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006).

Other forms of fostering identified in Ghana include long-term and short-term fostering. Fostering by sympathisers and queenmothers is also common in Ghana. Evidence of this is found among the Krobos in the Manya Krobo Municipality in the care of orphaned children through HIV/AIDS (Ansah-Koi, 2006).

3.1.4. Informal social systems of care and support—food sharing and shelter sharing

Food sharing is also an interesting phenomenon that had existed since pre-colonial era. Although not much has been documented on this phenomenon, it symbolises solidarity. In a study on caring for the seriously ill in Ghanaian society, one respondent indicated that it is a common practice to share food and feed the seriously ill (Atobrah, Citation2014). There is also evidence of food sharing between Fulani cattle herders and native farmers of Asante Akim North District in the Ashanti Region and Gushiegu District in Northern Ghana. In both jurisdictions, there has been food exchanges between farmers and herders where food crops are exchanged for milk (Bukari et al., Citation2018). Whilst this signifies co-operation between the two parties, it depicts solidarity and reciprocity. Reciprocity has long been argued as constituting a fundamental social structure of African societies such that in situations of possible conflicts, reciprocity tends to change the dynamics to cooperation (Lévi-Strauss, Citation1969; Tsai & Dzorgbo, Citation2012). Food sharing is also evidenced among single migrant women from Northern Ghana to Accra in search of greener pastures. Food sharing by established migrants is one of the non-market (informal) coping strategies of newly arrived migrants. This practice is inspired by moral obligation (altruism) and ethnic commitment (Tufuor et al., Citation2015).

Shelter sharing is also another informal arrangement of care common among migrants in Ghanaian cities. Lack of decent accommodation or dwelling place is a major challenge for migrants to cities in search of greener pastures. The negotiation strategies of newly arrived migrants include teaming up with existing migrants who are usually their kinsmen for shelter (Imam & Tamimu, Citation2015). Tufuor et al. (Citation2015) recount the role of shelter-sharing as a non-market strategy for coping with financial hardships by single migrant women. At the Old Fadama Market in Accra, the migrants form associations based on ethnic groups, and their leaders known as magajias spearhead the support of new migrants in the areas of shelter, food, and finance. The support for accommodation is motivated by ethnic commitment and solidarity. There was no evidence of reciprocity in offering such support to new migrants.

Shelter sharing was previously common in family-houses where deported Ghanaian migrants were provided shelter. Korboe (Citation1992), recounts how millions of Ghanaian migrants deported from Nigeria in 1983 were provided shelter by relatives in family-houses. This extension of support which was based on kinship ties contributed to lessening the effect of economic crises on these deported migrants. With the provision of shelter, they quickly found livelihood activities that facilitated their stabilisation. It was common to find extended family members who had marital challenges return to their family-houses for shelter. Danso-Wiredu and Poku (Citation2020) recount the role of family compound houses in providing shelter to both extended family members and migrant workers. Residents do not pay any rent and are only responsible for the upkeep of the houses. Migrant workers who are nonkinsmen are also provided shelter to the extent that they are given recognition in the family and accepted in the family and given their own room.

4. Discussions

4.1. Underlying concepts of informal social and economic systems

4.1.1. Underlying concepts of informal systems of labour relations

In the context of the Ga-Dangme coastal fisher-folks, the practice of labour pooling and providing any support concerning livelihood is tied to kinship. In the spirit of solidarity, family members were prioritized over other members of the fishing community. In the same spirit of solidarity, the owner of capital decides to include less endowed family members in the fishing crew. Guided by solidarity, the less endowed family member refuses to decline the offer to join the fishing crew. Eventually, both the owner of capital and the less endowed family members benefit from this labour relation (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995). Solidarity with kinsmen motivates the owner of capital to also supply fish on credit to the female family members and seek assistance for other family members who lack employment avenues. The less endowed family members, after receiving support and are economically sound, are also expected to reciprocate support to other family members (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995). This connotes unbalanced reciprocity.

In the case of share tenancy in tree crop production, it enabled land owners who were indigenes of cocoa farming communities expand their cocoa production as they aquired additional land and employed tenants or labourers who were usually migrants to work on their lands. In this arrangement, the land owners expanded their enterprises while the migrants also had access to farmlands and livelihood opportunities (Boadu, Citation1992; Robertson, Citation1982). This arrangement is underpinned by reciprocity, where there is mutual benefit for both parties. These labour arrangements offer the opportunity for migrants and the landless to have access to land to engage in farming activities. The land owners who do not also have the labour or are not available to carry out farming activities on the land also gain from the proceeds of the farm. This opportunity has the potential to reduce the effect of economic hardships experienced by vulnerable socio-economic groups, such as landless individuals and migrants.

4.1.2. Underlying concepts of informal systems based on kinship norms

Informal systems based on kinship norms are characterised by support for kinsmen. It is expected that a kinsman endowed with material resources support others. In so doing, the needs of the less endowed will be met and as they also get out of the poverty trap, they also support others. From the findings on kinship relationships between uncles and nephews in matrlineal akan societies, it is expected that the uncles uphold their responsibilities of caring for the children of their sisters without any recompense (Maclean, Citation2010). This social norm expresses kinship solidarity. Rationally, as the uncle transfers resources to the nephew at a point in time, the nephew also transfers resources to the uncle at a later period when he is aged. There is also the tendency of uncles to intensify their care of nephews and nieces to receive maximum care when they are aged. With this, reciprocity is seen as the thread holding and sustaining this kinship relation. Informal relations are not codified and their success and enforcement depend on strong motivators. Consequently, the expectation of receiving a commensurate or near commensurate support in the future serves as a motivating factor.

Maclean (Citation2010) describes the transfers between uncles and nephews in matrilineal akan societies as intergenerational reciprocity. Agree et al. (Citation2005), illustrate three models of intergenerational transfer, namely altruism, exchange, and insurance, that explain the transfer of resources from one generation to the other. Altruistic transfers are not expected to be reciprocated while exchange and insurance transfers are expected to be reciprocated. The altruistic motive of transfer seeks to enhance the wellbeing of the recipient and transfers will reduce when the income of the recipient increases and vice versa (Kananurak & Sirisankana, Citation2018). From the observation of La Ferrara (Citation2007), the intensification of transfers by biological children in households with nephews as co-residents is made to induce the bequeathal of cocoa farms. The motivation here for transfer is exchange, which is intergenerational reciprocity.

Maclean (Citation2010) again observed in some Akan societies, a neglect by uncles associated with a decline in transfers to nephews following unmet expectations. Although the underlying concept of these social relations is kinship solidarity, support is withdrawn if opportunistic behaviours are exhibited. Consequently, reciprocity whether balanced or unbalanced, is an important concept to consider in kinship relations.

4.1.3. Underlying concepts of child fostering

In crisis fostering, extended family members of orphans and other community members have the strong need or desire to see the survival of the orphan (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014). Among the Krobos in the Manya Krobo Municipality, queenmothers who have no blood ties with orphans take up their care after the demise of their parents through HIV/AIDS (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006). Among the Gonjas, foster parents willingly accept foster children whose parents are going through economic hardship (Goody, Citation1982). The belief among the Dagmobas that children are gifts from God and that everyone must support in their upbringing also motivates community members to extend care to orphans (Kuyini et al., Citation2009). These acts are the demonstration of altruism and solidarity. However, overtime, foster parents also benefit from the children through errands and performance of household tasks and the foster parents also benefit from the children.

Alliance and apprenticeship fostering, and domestic fostering occur in different forms. These fostering types have deliberate intentions. In providing training and skills to foster children, alliance and apprenticeship fostering is also embedded with service to the foster parents (Klomegah, Citation2000). An alliance is also established with the foster parents which serves as a benefit for the child as well as the biological parents. The foster parents also benefit from the fostering relations. Domestic fostering is encouraged purposely to offer emotional support to childless couples (Klomegah, Citation2000). As the child receives care and support from the couple, they also receive emotional support. Reciprocity is the motivating force in these fostering types. Similarly, the foster parents also benefit from the services of the child in running errands and performing household chores.

From the studies reviewed, child fostering in Ghana is usually underpinned by altruism, solidarity, sympathy, and reciprocity (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014; Klomegah, Citation2000).

4.1.4. Underlying concepts of food sharing and shelter sharing

The underlying concepts of food sharing vary by context. In the context of the critically ill, it is a common practice among the Gas in Ga communities to share food with the critically ill (Atobrah, Citation2014). This act comes naturally and has been practiced for a long time without questioning. The belief in helping the vulnerable is a force in this action. There may be latent reciprocal intentions of bequest from the sick person. However, the visible motive which can be explained is altruism. In the context of food sharing between the herders and farmers of Asante-Akim North and Gushiegu Districts of Ghana, the motive for food sharing is needed, as crops are exchanged for milk (Bukari et al., Citation2018). The exchange model, a strand of reciprocity, explains this kind of transfer. Many food sharing relations in the past that have operated similarly to barter trade have been driven by reciprocity. Food sharing relations between newly-arrived migrants and established migrants from Northern Ghana to Accra are worthy of study. The newly-arrived migrants, similar to the sick are vulnerable and the initial motivating force to offer support is altruism and solidarity (Tufuor et al., Citation2015).

The motivating factors and underlying concepts of shelter sharing also vary depending on the context. In the case of newly arrived migrant workers who are provided shelter by established migrants, the decision to share accommodation is motivated by kinship and ethnic ties (Imam & Tamimu, Citation2015; Tufuor et al., Citation2015). In the case of shelter sharing with deported Ghanaian migrants, the migrants are vulnerable and need help at the time of providing the shelter. Altruism could be the initial motivation for a well-established migrant to accommodate a newly-arrived migrant (Korboe, Citation1992). In family compound houses where non-kinsmen migrant workers are provided shelter and acceptance into families, the relation follows a different order. The initial expectation is that the migrant worker runs some errands around the house and helps in the cleaning and upkeep of the house. The migrant worker may present him or herself as a person in need of shelter and it requires an altruistic instinct to accept and accommodate such a migrant who is not known to the family (Korboe, Citation1992). Altruism could be the initial driving force in this relation. There could also be reciprocity as an underlying concept as the migrant worker is expected to run some errands around the house as he or she receives shelter without the payment of housing rent. An illustration of the underlying concepts of the various informal systems is presented in .

Table 1. Underlying concepts of informal social and economic systems of relations.

4.2. Transformations in informal social and economic systems

There has been much concern by Economists on the efficiency and effectiveness of informal systems. Notably, there is much concern on the sustainable enforcement of reciprocity in these systems. There is an equal concern by Anthropologists about the weakening of reciprocity in these informal systems discussed in this paper (Maclean, Citation2010; Tsai & Dzorgbo, Citation2012). While these systems are evolving to modern forms, it is important to examine their transformations to understand how the foundational concepts have taken on new forms. This raises concern for the sustainability of these systems. Whereas many of these systems are built on kinship ties, what happens when kinship ties are weakened? There is evidence of weak kinship ties in Ghana and Africa Following modernisation and economic development (Aboderin, Citation2004a, Citation2004b). Over the years, endogenous and exogenous factors have resulted in changes in the operation of these systems discussed above. The following sections discuss the transformations in each of the informal social and economic systems understudied.

4.2.1. Transformation in informal systems of labour relations

Baah and Kidido (Citation2020) report a transformation in the ratio of crop sharing in the share tenancy relationship. In the abusa tenancy agreement which initially ensured two-thirds of the farm produce was given to the tenant farmer, eventually, the ratio shifted to half of the proceeds as in the abunu system. It further shifted to the abusa labourer arrangement where a third of the proceeds are given to the labourer farmer and two-thirds are given to the owner of land due to scarcity of land. There is also limited access to the land by the labourer farmer. The labourer is not encouraged to live on the farmland (Amanor, Citation2008; Amanor & Diderutuah, Citation2001; Baah & Kidido, Citation2020). This current crop sharing ratio defines the abusa share tenancy arrangement.

There are also new developments where financial commitments by tenants and labourers are requested by land owners before land is released for farming activities. This resulted from the increased opportunity cost of land. Owing to population growth, alternative uses of land for human settlements became the reality (Baah & Kidido, 2020). These incidences weakened the attractiveness of share tenancy (share cropping) to farmers as the turn of events favoured land owners. Robertson (Citation1982), attributed the lack of attractiveness of this informal economic system to change in land tenure system. As the right of ownership became obscure and complicated, the tendency to seek greater rents from land became high. Again increasing population and scarcity of land is also another factor that tend to drive land owners to seek greater rents and divert away from the established insitutions of crop sharing (Baah & Kidido, Citation2020; Robertson, Citation1982). Undoubtedly, these new developments have a tendency to collapse the established crop sharing arrangements that offer risk-sharing support to individuals lacking the means of production and owners of the means of production seeking to expand production. The implication is an increased vulnerability of the less priviledged in society.

Overtime, other crop sectors, such as the oil palm and citrus sectors started practicing the abusa sharecropping arrangement and developed variants of the abusa sharecropping arrangement and also introduced transformations into the institution. The abusa system evolved into two distint systems namely abusa tenant and abusa labourer contracts. In the abusa tenant agreement, the worker on the farm is seen as a tenant and caretaker of the land, and at the end of the harvesting season, the tenant receives two-thirds of the yield. Meanwhile, in the abusa labourer arrangement, the worker provides labour and is not obliged to serve as a caretaker. In this instance, the worker receives a third of the proceeds while the landowner receives two-thirds (Amanor & Diderutuah, Citation2001).

Labour relations among fisherfolk in the Ga-Dangme coastal area have also received some transformations following economic hardship and monetisation of the economy. Previously, male relatives involved in fishing supplied fish to their wives and other female relatives on credit. However due to economic hardship and the immediate need for financial resources, this practice ceased and the fishermen had to receive payment upfront from their relatives just like other customers (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995).

4.2.2. Transformations in informal systems based on kinship norms

Over the years, there has been much concern about the weakening of kinship ties and a decline in intergenerational reciprocity (Aboderin, Citation2004a, Citation2004b; Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014; Maclean, Citation2010; Oppong, Citation2006). Intergenerational reciprocity is also important to strengthen kinship ties peculiar to kinship norms and other kinship relations in Africa. This is the fabric of kinship ties without which kinship ties are weakened. This is an endogenous contribution to the breakdown of kinship ties.

In Ghana, Maclean (Citation2010, p. 53) identified that a change in focus of economic activity weakened intergenerational reciprocity and eventually weakened kinship relations. A change in choice of economic activity from cocoa cultivation to tomato crops fuelled a break-down in intergeneration reciprocity in some cocoa-growing communities in the Ashanti, Bono, and Western Regions of Ghana. After the onset of bushfires on cocoa farms as a result of prolonged droughts in the early 1980s, many young cocoa farmers diverted to tomato farming. Tomato farming did not require much land, but rather much labour. Consequently, the need for land from uncles through bequest declined and this was a disincentive for transfers to matrilineal uncles. Contrariliy, Akans in Ivory Coast maintained kinship ties with their uncles and elders because of the high value placed on cocoa cultivation (Maclean, Citation2010).

A neglect by uncles associated with a decline in transfers to nephews has also been noted among some Akan societies in Ghana. Maclean (Citation2010) in comparing matrilineal Akan societies in Ghana and Ivory Coast, observed a lower extent of transfers from uncles to nephews in the Bono areas of Ghana (2%) than in Ivory Coast (16%). This, she explained had a repercussion on transfers from nephews to their uncles. Lévi-Strauss (Citation1969), emphasised the role of reciprocity as a fundamental social structure of African societies. When uncles reduce their transfers to nephews, it follows that nephews also reduced their transfers to the uncles in later years. Fuelled by economic hardships, poverty, and nucleation of families, it becomes burdensome for uncles to care of their nephews. It became rationally difficult when their biological children did not receive commensurate care from their maternal uncles. This situation represents unbalanced and unequal reciprocity which is a precursor to a breakdown of kinship ties.

The loss of filial piety is also recorded as a contributor to the weakening of kinship ties. Respect for parents and grandparents and also uncles is gradually dictated by the success of the elderly in terms of material possessions. Sadly, the loss of filial piety have resulted in the neglect of the aged who are not wealthy (Oppong, 2006). While this has implications for deepening economic hardship and poverty among the aged, it shows not only a breakdown of traditional values that supported Ghanaian societies in times past but a drift to materialistic values.

Urban-rural shifts is also one external factor that directly or indirectly weakens kinship ties and transforms informal systems based on kinship norms. Younger generations seeking employment and eductional opportunities in urban areas deprive the older generations in rural areas of intergenerational co-operation and support in the homes and farms. Expected transfers are not made regularly because of distance (Oppong, 2006). With migration of younger generations to the cities for schooling or work, the desire to engage in cocoa farming dwindles. Here the interest in receiving parcels of land from uncles through bequest is declined and there is little motivation for transfers from nephews to uncles (Maclean, 2010). However, with advancement in technology which facilitates transfer, some little amounts trickle into the older generation.

Modernisation, marketization of economies, and economic development have also been reported as a contributing factor to the weakening of kinship ties in Africa. These factors induce smaller family sizes which have taken the form of nuclear families in Western economies and reduce the role of extended family networks and reciprocity which traditionally have served as safety nets in mitigating economic hardships (Aboderin, Citation2004a, Citation2004b; Tsai & Dzorgbo, Citation2012).

Another set of authors does not necessarily perceive that the weakening in kinship ties with rural ancestors signifies the least the loss of value for support from kinsmen and vice versa. There are rather transformations in these informal social and economic systems which are carried out in other dimensions. Maclean (Citation2010) reports of increasing alliance with friends and peers in terms of transfers. Again, the principle of reciprocity is the fabric of the support to friends as respondents found it more appropriate to approach their friends and peers for help during financial difficulties. While this reflects the loss of importance of familial ties, it reveals weaknesses in familial relationships. Familial relationships are set and one can easily take it for granted when support is received. In urban communities, different forms of informal social systems are plumeting to meet the needs of communities where kinship support is waning. These systems, known as informal networks involve family members, friends, neighbours, co-workers, and members of religious groups (Manful & Cudjoe, 2018). This suggests a transformation in the meaning of kinsman. For migrants in cities, kinsmanship seems to be extended to neighbours and parties with whom there is regular exchange. It is however not known if the progression of these networks weakens the linkage with extended families in rural areas or not. Again, the priniciple underlying such informal networks is reciprocity. This underscores the importance of reciprocity in all forms of informal relationships relevant for managing economic hardships.

4.2.3. Transformations in child fostering arrangements

Frimpong-Manso (Citation2014), notes a transformation in the traditional informal type of foster care system following social change, economic hardship, and social issues, such as the occurrence of HIV/AIDS, and unmanaged urbanisation. Poverty also made it difficult for people to foster children voluntarily. In addition, the extended family’s capacity to take care of the needs of orphans also declined (Nukunya, Citation2016). Consequently, there was a decline in the practice of the traditional foster care practices of Ghanaian societies. The gap in care of orphans and the needy was taken care by foreigners who introduced residential care facilities (Apt et al., Citation1998). Later on missionaries also took up the task in caring for physically challenged children and those at risk of being used as collateral for money lending (Darkwa, Citation1999) until children’s homes, such as the Osu Children’s home was established.

It is interesting to note how domestic fostering has transformed into domestic house steward arrangements because of monetisation of the Ghanaian economy. Children sent away to live with extended family members are expected to be given regular allowances or provided training in a vocation in return. It is interesting to note that the underlying concept in the domestic house help arrangement is reciprocity. The parent of the child ensures the child also benefits from staying with the family. While the child receives a regular income from the family members, the family also benefits from the services of the steward.

4.3. Implications for sustainable management of economic hardship within the context of poverty reduction

The SDG1 seeks to end poverty in all its form globally. One of its targets is to implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all and by 2030, achieve sustainable coverage of the poor and vulnerable. The findings from the review indicate three main underlying concepts of the informal social and economic systems. These are reciprocity, altruism, and solidarity (). The study also highlights transformations and declines in these informal systems.

In the face of recent economic hardship following COVID-19 and the Russian-Ukraine war, the implications of the decline in these informal systems which have served as social safety nets are threatening poverty reduction. Weakening kinship ties threaten the bond of solidarity and prevent filial care and support. This is even more threatening with economic hardship, where resources are limited and the chances of interhousehold transfers and support are low. The implications of weakening kinship ties could be an exploration of ties with friends and colleagues. Maclean (Citation2010) identifies an increase in transfers between friends in Ghana overtime, underpinned by reciprocity as kinship ties weakened. It is likely individuals will increase ties with friends, colleagues at work, churches, and other religious groups to receive support underpinned by reciprocity. This tends to weaken further the kinship ties. Although other forms of ties are necessary for informal social support and care, filial piety which supports transfers among kinsmen cannot be overlooked. In circumstances of asymmetric information and opportunistic behaviours, a strong driving force beyond reciprocity is required to sustain informal systems of care and support. Extending filial piety and solidarity to informal systems of care and support among friends and colleagues is necessary. Upholding values of truthfulness, integrity, and loyalty is necessary to guide and strengthen informal systems of care and support among friends and colleagues.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendation

This paper reviews six informal social and economic systems that have traditionally served as safety nets in mitigating economic hardship. The economic systems identified include labour pooling and share tenancy and the social systems understudied are kinship relations, child fostering, shelter sharing, and food sharing.

Matrilineal kinship norms pertaining to matrilineal Akan societies were examined. The informal social system where an uncle, known as wofa, is expected to take care of the needs of the sons and daughters of his sister in addition to his own children, was discussed. The concepts driving this practice are kinship solidarity and reciprocity, which also sustain this social system (La Ferrara, Citation2007; Maclean, Citation2010). Over the years, weakening kinship ties and a decline in intergenerational reciprocity have been threatening the sustainability of this social system (Aboderin, Citation2004a, Citation2004b; Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014; Maclean, Citation2010; Oppong, Citation2006). Rural-urban shifts, economic monetisation, and loss of filial piety are some of the factors that have contributed to the weakening of kinship ties (Oppong, Citation2006).

Labour pooling arrangements among fisher folk in the coastal zones of Greater Accra Region of Ghana, and share tenancy arrangement among crop farmers in cocoa growing areas of Ghana were examined. The study finds that among the Ga-Dangme fisher folk, the whole space of artisanal marine fishing and it’s allied economic activities are organised around kinship norms (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995). Kinsmen were the first preference for the owners of capital, when in search of labour. The motive of this labour pooling arrangement is to provide livelihood opportunities for the kinsmen who in turn through hard work contribute to the progress of the fishing venture (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995). The study also observed from the review that when canoe owners returned from fishing, women relatives were given preference in the sale of fish and were allowed to buy on credit. Canoe owners also connected their relatives to their trade partners for employment. In examining these informal labour relations, the underlying concepts observed were altruism and reciprocity. Canoe owners are driven by altruism to help the less privileged relatives and they are also in turn expected to work hard to contribute to the progress of the business and help others. The review noted a decline in these arrangements particularly with the sale of fish on credit to kinsmen, due to economic hardship, this practice is on a decline (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, Citation1995). Future studies on the causes of the decline in the other labour arrangements among the fisher folk are recommended.

Share tenancy, another informal labour arrangement, which is common in the cocoa subsector was examined. In share tenancy, there is a crop sharing agreement between the landowner and the farmworker, who is the supplier of labour. The common type of share tenancy in Ghana is the abusa arrangement. This labour relation is underpinned by reciprocity as there is a mutual benefit between the landowner and labourer tenant or farm worker. The paper noted transformations in this labour arrangement based on changes in crop sharing ratio and access to farmland by the labourer. Initially, the abusa tenancy arrangement ensured two-thirds of the crops were given to the tenant labourer (Robertson, Citation1982). This changed overtime to the abunu system where half of the crops were given to the labourer tenant. Overtime this has changed to the abusa labourer arrangement, where a third of the proceeds is given to the labourer (Amanor, Citation2008; Amanor & Diderutuah, Citation2001; Baah & Kidido, Citation2020).

Child fostering and its various forms were also examined in the paper. Crisis fostering, alliance and apprenticeship fostering, and domestic fostering were discussed. The concepts that support child fostering in Ghana are altruism, solidarity, and reciprocity (Klomegah, Citation2000). The review discussed the decline in the traditional child fostering arrangements following social change, economic hardship, weakening kinship ties, and unmanaged urbanisation (Frimpong-Manso, Citation2014). The extended family’s lack of financial capacity to take care of orphans also affected the practice (Nukunya, Citation2016).

Food sharing and shelter sharing were also examined. Food is shared with the critically ill (Atobrah, Citation2014) and is also exchanged between parties for cooperation and peace (Bukari et al., Citation2018). Food sharing also occurs among migrants in search of greener pastures (Tufuor et al., Citation2015). The concepts underpinning food sharing include altruism, reciprocity, and solidarity. Shelter sharing is common among migrants, where newly arrived migrants are sheltered by established migrants (Tufuor et al., Citation2015). Shelter sahing also occurs in family houses where individuals in need of accommodation are sheltered (Korboe, Citation1992). Shelter sharing is driven by altruism, solidarity, and reciprocity. The transformation in food sharing and shelter sharing in Ghana are not well documented.

While these systems have historically played important roles in mitigating economic hardships, the decline in their practice is consequential to poverty reduction in the face of recent economic hardships. Deliberate efforts to incorporate lessons from these informal social and economic systems are needed to reduce poverty and achieve SDG1. Firstly, there is the need to preserve the underlying concepts of solidarity, altruism, and reciprocity in society to maintain informal support and care. Informal social and economic systems of support and care, which constitute social safety nets are known to play an important role in complementing public safety nets and contribute to economic growth (Alderman & Yemtsov, Citation2014). Even in developed economies with strong social protection programs, there is evidence of the impact of informal social systems of support in minimising economic hardship (Reeskens & Vandecasteele, Citation2017).

There is also the need to promote altruism and solidarity to induce support and care for the vulnerable and needy in society. A study from Thailand shows that for three decades, as the economy developed, the level of altruism demonstrated through interhousehold transfers did not decline (Kananurak & Sirisankana, Citation2018). It is important to nurture and preserve the spirit of altruism, community, and solidarity through policies that seek to increase family and community strength. Government support in terms of tax reliefs and tax rebates to promote filial support and care is needed. In Ghana, there are tax incentives for individuals with aged parents. This can be extended to child fostering and other forms of informal social support whereby documented evidence can be provided to prevent negative externalities.

Thirdly, a revisitation of the traditional systems of care and management of economic hardship is needed to attain SDG1. In adopting nationally appropriate social protection systems, there is the need to incorporate concepts, such as reciprocity, solidarity, and altruism in public programs. Beneficiaries of support programs are to support other vulnerable members within their community when they rise above the poverty line. The formation of network groups among beneficiaries of social protection programs tends to induce values of solidarity, altruism, and reciprocity. A typical example for developing countries is the Ethiopia’s national Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP). This public safety-net program provides poor rural households cash in exchange for seasonal labour at public works. This tends to promote the spirit of reciprocity (giving back to society) and promote solidarity when beneficiaries work in teams or groups (Buller, et al., Citation2023). Consequently, in developing countries with limited resources, the need to reorganise existing social protection programs to incorporate existing informal systems is critical. Furthermore, In the face of economic hardships, efforts to motivate society to offer care and support for the needy following altruism and solidarity are necessary to reduce extreme poverty. Reciprocity may also be a motivating factor in some contexts where the beneficiary of care and support may be in the position to run some errands for the giver.

These efforts will contribute to the sustenance of informal social and economic systems of care and support which have contributed as safety nets for poverty reduction in developed and developing countries.

Secondly, deliberate efforts to include the concepts of solidarity, altruism, and reciprocity in existing social protection policies are recommended. The formation of network groups among beneficiaries of such programs is necessary. Thirdly, efforts to inculcate the attributes of altruism, solidarity, and balanced reciprocity through civic education are needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Theodora Akweley Asiamah

Theodora Akweley Asiamah is a Lecturer at the Department of Sustainable Development and Policy at the University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana. She earned her PhD in Development Studies from the University of Ghana’s Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, under the sponsorship of DAAD. Theodora has a diverse background and has published on broad themes, such as Financial Inclusion, Renewable Energy, Gender, and Sustainable Development. Her research interests include Social Change and Evolution, The informal Economy, Gender and Social Inclusion, Sustainable Agriculture, and Natural Resource Management.

References

- Aboderin, I. (2004a). Decline in material family support for older people in urban Ghana, Africa: Understanding processes and causes of change. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.3.s128

- Aboderin, I. (2004b). Modernisation and ageing theory revisited: Current explanations of recent developing world and historical Western shifts in material family support for older people. Ageing and Society, 24(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X03001521

- Affum, J. B. (2019). Origin-destination linkages as livelihood strategy for migrants from three regions in the northern sector of Ghana resident in the Cape Coast Metropolis [Master of Philosophy thesis]. University of Cape Coast.

- Agree, E., Biddlecom, A. E., & Valente, T. W. (2005). Intergenerational transfers of resources between older persons and extended kin in the Taiwan and the Philippines. Population Studies, 59(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720500099454

- Akresh, R. (2004). Adjusting household structure: School enrollment impacts of child fostering in Burkina. Institute of Labor Economics – IZA Discussion Papers, No. 1379, 1–41.

- Alderman, H., & Yemtsov, R. (2014). How can safety nets contribute to economic growth? The World Bank Economic Review, 28(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lht0

- Amanor, K. S. (2008). The changing face of customary land tenure. In J. Ubink & K. S. Amanor (Eds.), Contesting land and custom in Ghana state, chief, and the citizen (pp. 55–80). Leiden University Press.

- Amanor, K., & Diderutuah, M. K. (2001). Share contracts in the oil palm and citrus belt of Ghana. Lied.

- Ambrus, A., Mobius, M., & Szeidl, A. (2010). Consumption risk-sharing in social networks. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. Working Paper, 15719, 1–67. http://www.nber.org/papers/w15719

- Ansah-Koi, A. A. (2006). Care of orphans: Fostering interventions for children whose parents die of AIDS in Ghana. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(4), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3571

- Apt, N. A., Blavo, E., & Wilson, S. (1998). Children in need: A study of children in institutional homes in Ghana. Social Administration Unit, University of Ghana.

- Atobrah, D. (2014). Caring for the seriously ill in a Ghanaian society: Glimpses from the past. Ghana Studies, 15–16(1), 69–101. https://doi.org/10.3368/gs.15-16.1.69

- Awedoba, A. K. (2005). Culture and Development in Africa. Historical Society of Ghana, Legon.

- Baah, K., & Kidido, J. K. (2020). Sharecropping arrangement in the contemporary agricultural economy of Ghana: A study of Techiman North District and Sefwi Wiawso Municipality, Ghana. Journal of Planning and Land Management, 1(2), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.36005/jplm.v1i2.22

- Besley, T. (1995). Nonmarket institutions for credit and risk sharing in low-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(3), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.3.115

- Bhattamishra, R., & Barret, C. (2010). Community-based risk management arrangements: A review. World Development, 38(7), 923–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.12.017

- Boadu, F. O. (1992). The efficiency of share contracts in Ghana’s cocoa industry. Journal of Development Studies, 29(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389208422264

- Booth, W. J. (1994). On the idea of the moral economy. American political science review, 88(3), 653–667.

- Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, E. (Ed.). (1995). Kinsfolk and workers: Social aspects of labour relations among Ga-Dangme coastal fisherfolk. In Dynamique et Usage des ressources en sardinelles de côtier du Ghana et de la Côte d’Ivoire (pp. 134–151).

- Bourlès, R., Bramoullé, Y., & Perez-Richet, E. (2021). Altruism and risk sharing in networks. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(3), 1488–1521. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaa03

- Bukari, K. N., Sow, P., & Scheffran, J. (2018). Cooperation and co-existence between farmers and herders in the midst of violent farmer-herder conflicts in Ghana. African Studies Review, 61(2), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2017.124

- Buller, A. M., Pichon, M., Hidrobo, M., Mulford, M., Amare, T., Sintayehu, W., Tadesse, S., & Ranganathan, M. (2023). Cash plus programming and intimate partner violence: A qualitative evaluation of the benefits of group-based platforms for delivering activities in support of the Ethiopian government’s Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP). BMJ Open, 13(5), e069939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069939

- Cassiman, A. (2010). Home call: Absence, presence and migration in rural northern Ghana. African Identities, 8(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725840903438269

- Danso-Wiredu, E. Y., & Poku, A. (2020). Family compound housing system losing its value in Ghana: A threat to future housing of the poor. Housing Policy Debate, 30(6), 1016–1032. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1792529

- Darkwa, O. K. (1999). Social work education in an electronic age: The opportunities and challenges facing social work education in Ghana. Professional Development: The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education, 2(1), 38–43.

- Dercon, S., De Weerdt, J., Bold, T., & Pankhurst, A. (2006). Group-based funeral insurance in Ethiopia and Tanzania. World Development, 34(4), 685–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.09.009

- Evans, D. K., & Miguel, E. (2007). Orphans and schooling in Africa: A longitudinal analysis. Demography, 44(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2007.0002

- Fafchamps, M. (1992). Solidarity networks in preindustrial societies: Rational peasants with a moral economy. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 41(1), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1086/452001

- Fafchamps, M. (2011). Risk sharing between households. In J. Benhabib, A. Bisin, & M. O. Jackson (Eds.), Handbook of social economics (pp. 1255–1279). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7218(11)01029-X

- Fafchamps, M., & Gubert, F. (2007). The formation of risk sharing networks. Journal of Development Economics, 83(2), 326–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.05.005

- Fafchamps, M., & Lund, S. (2003). Risk sharing networks in rural Philippines. Journal of Development Economics, 71(2), 261–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00029-4

- Frimpong-Manso, K. (2014). From walls to homes: Child care reform and deinstitutionalisation in Ghana. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(4), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12073

- Garuba, D. S. (2006). Survival at the margins: Economic crisis and coping mechanisms in rural Nigeria. Local Environment, 11(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830500396099

- Goody, E. N. (1982). Parenthood and social reproduction: fostering and social roles in West Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Granovetter, M. (2000). The economic sociology of firms and entrepreneurs. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship.

- Imam, H. A., & Tamimu, H. (2015). ‘Life beyond the walls of my hometown’: Social safety networks as coping strategy for Northern migrants in Accra. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Management Studies, 2(1), 25–43.

- Isiugo-Abanihe, U. C. (1985). Child foster age in West Africa. Population and Development Review, 11(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973378

- Kananurak, P., & Sirisankana, A. (2018). As an economy becomes more developed, do people become less altruistic? The Journal of Development Studies, 54(10), 1878–1890. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1371297

- Klomegah, R. (2000). Child fostering and fertility: Some evidence from Ghana. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 31(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.31.1.107

- Korboe, D. (1992). Family-houses in Ghanaian cities: To be or not to be. Urban Studies, 29(7), 1159–1171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989220081101

- Krishnan, P., & Sciubba, E. (2004). Endogenous network formation and informal institutions in village. Working Paper in Economics, No. 462.

- Kutsoati, E., & Morck, R. (2016). African successes, volume II: Human capital. In S. Edwards, S. Johnson, & D. N. Weil (Eds.), Family ties, inheritance rights, and successful poverty alleviation: Evidence from Ghana (pp. 215–252). University of Chicago Press.

- Kuyini, A. B., Alhassan, A. R., Tollerud, I., Weld, H., & Haruna, I. (2009). Traditional kinship foster care in northern Ghana: The experiences and views of children, carers and adults in Tamale. Child & Family Social Work, 14(4), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00616.x

- La Ferrara, E. (2007). Descent rules and strategic transfers: Evidence from matrilineal groups in Ghana. Center for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper, (611), 1–36.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969). Elementary structure of kinship. Beacon Press.

- Maclean, L. M. (2010). Informal institutions and citizenship in rural Africa: Risk and reciprocity in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire. Cambridge University Press.

- Manful, E., & Cudjoe, E. (2018). Is kinship failing? Views on informal support by families in contact with social services in Ghana. Child & Family Social Work, 23(4), 617–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12452

- Mariam, D. H. (2003). Indigenous social insurance as an alternative financing mechanism for health care in Ethiopia (the case of Eders). Social Science & Medicine, 56(8), 1719–1726. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00166-1

- Nukunya, G. K. (2016). Tradition and change in Ghana: An introduction to sociology. Ghana Universities Press.

- Obert, P., Theocharis, Y., & van Deth, J. W. (2018). Threats, chances and opportunities: Social capital in Europe in times of social and economic hardship. Policy Studies, 40(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2018.1533109

- Oermann, M. H., & Knafl, K. A. (2021). Strategies for completing a successful integrative review. Nurse Author & Editor, 31(3–4), 65–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/nae2.30

- Oppong, C. (2006). Familial roles and social transformations: Older men and women in sub-Saharan Africa. Research on Aging, 28(6), 654–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506291744

- Rabbi, M. F., Hassen, T. B., El Bilali, H., Raheem, D., & Raposo, A. (2023). Food security challenges in Europe in the context of the prolonged Russian–Ukrainian conflict. Sustainability, 15(6), 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064745

- Reeskens, T., & Vandecasteele, L. (2017). Economic hardship and well-being: Examining the relative role of individual resources and welfare state effort in resilience against economic hardship. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9716-2

- Robertson, A. F. (1982). Abusa: The structural history of an economic contract. The Journal of Development Studies, 18(4), 447–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388208421840

- Rosenzweig, M. (1988). Risk, implicit contracts and the family in rural areas of low-income countries. The Economic Journal, 98(393), 1148–1170. https://doi.org/10.2307/2233724

- Rosenzweig, M., & Stark, O. (1989). Consumption smoothing, migration, and marriage: Evidence from rural. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 905–926. https://doi.org/10.1086/261633

- Serra, R. (2009). Child fostering in Africa: When labor and schooling motives may coexist. Journal of Development Economics, 88(1), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.01.002

- Tsai, M.-C., & Dzorgbo, D.-B S. (2012). Familial reciprocity and subjective well-being in Ghana. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00874.x

- Tufuor, T., Niehof, A., Sato, C., & van der Horst, H. (2015). Extending the moral economy beyond households: Gendered livelihood strategies of single migrant women in Accra, Ghana. Women’s Studies International Forum, 50, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2015.02.009

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x