Abstract

Conceptualizations of jogging and strolling in English and Arabic may represent a key element in the successful performance of such actions. We aimed to demonstrate similarities and differences between the English verbs ‘jogging’ and ‘strolling’ and their Arabic counterparts ‘yuharwil’and ‘yatanazzah’. As our theoretical framework, we adopted the Natural Semantic Metalanguage Approach to meaning and relied on Arabic and English semantic primes to create a semantic template consisting of Lexicosyntactic Frame, Prototypical scenario, Manner, and Prototypical outcome to explicate these verbs. To facilitate our comparative analysis of the English verbs and their Arabic counterparts, we consulted four English monolingual dictionaries: Merriam-Webster, Macmillan, Oxford learner’s Dictionary, and Cambridge Dictionary, and consulted three Arabic monolingual dictionaries: Mu’jam maqayis al-lughah by Aḥmad Ibn Fāris al-Qazwīnī, Lisān al-ʿArab by ibn Manzūr, and Mu’jam al-lughah al-’arabīyah al-mu’āṣirah by Ahmed Mukhtar Omar. Our analysis revealed that: A) The English and the Arabic verbs relied on similar conceptualization elements including the use of legs and feet, having a starting point, a destination, as well as alternation, and repetition. B) ‘jogging’ was conceptualized as nonurgent and slower in comparison to ‘yuharwil’. C) Duration of contact with the ground in ‘strolling’ and ‘yatanazzah’ was found to be similar. The same was also true for ‘jogging’ and ‘yuharwil’ whose duration of contact was shorter than ‘strolling’ and ‘yatanazzah’. D) As for purpose, ‘jogging’, and ‘strolling’ were found to be motivated by a desire to exercise or relax while ‘yatanazzah’ was found to be motivated by entrainment only, and ‘yuharwil’ did not state a purpose.

1. Introduction

Understanding how human motion is conceptualized and lexicalized in a language can be considered a key element in the ability to distinguish between different actions and translate them. Verbs of human locomotion received considerable attention from cognitive linguistics. Several attempts including Talmy’s (Citation1985) were made to determine whether verbs of human locomotion encode ‘manner’ or ‘path’ and the extent to which they do so. However, it becomes clear that classifying verbs of human locomotion into ones encoding ‘manner’ or ‘path’ does not demonstrate the ways through which these verbs’ meanings are lexicalized and whether such lexicalized meanings could vary across languages. In cases where ‘manner’ and ‘path’ are analyzed cross linguistically, it is also observed that English concepts and interpretations are heavily drawn upon to represent the conceptualization of non-English speakers. This may become problematic because over reliance on English can be a form of Anglicization and contribute to an automatic betrayal of the non-European culture by giving ‘full weight to mistranslation and misreading’ as stated by (Rashwan, Citation2020, p. 363). If we consider the verbs ‘yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’ and translate them into their English counterparts ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’, a potential loss of the Arabic meaning can be incurred. When the verb ‘yuharwil’ is looked up in an Arabic- Arabic dictionary such as al-Mu’jam al-wajiz (1999, p. 648), the meaning given is ‘.هَرْوَلَ): أَسْرَعَ بيْن العَدوِ والمشي. (الهَرْوَلَةُ): سَيْرٌ حثيثٌ بين الصَّفَا والمرْوَة) /haɾwala ʔasɾaʕa bajna ʔal-ʕadwi wa-ʔal-maʃji ʔal-haɾwalatu sajɾun ħaθiːθun bajna ʔalsˤafaː wa-ʔal-maɾwati/(Brierley et al., Citation2016), which can be translated into English as ‘walking fast in a speed that is between running and walking’ and ‘a fast-paced form of walking done between Al Safa and Al Marwa’. This means that ‘yuharwilu’, refers also to Sa’i i.e. a pillar of Hajj and Umrah in Islam that ‘jogging’ does not capture. The same may also be true for ‘yatanazzah’ which is defined by the same dictionary as ‘.تَنَزَّهَ) عن الشيء: بَعُدَ عنه وتصَّوَنَ. و- فلانٌ: خَرَجَ إلى الاَرضِ للنُزْهَةِ)’/ tanazzaha ʕan ʔal-ʃajʔi baʕuda ʕanhu watasˤawwana w fulaːnun xaɾaʤa ʔilaː ʔal-aːaɾdˤ li-ʔal-nuzhati/(Brierley et al., Citation2016) which means in English ‘refraining from doing something, or to protect oneself from something’ or ‘going out for a stroll’. When the Arabic meaning is compared to that of the English verb strolling, it becomes clear that the religious connotation is absent in English. This could mean that despite being associated with a religious meaning and context that we do not focus on in our study, translating the Arabic verbs into English may be a complex task. This is because in religious contexts such as in Prophetic Hadith or Quranic verses, rendering the religious meaning is of paramount importance, and not having an equivalent that represents this in English renders such terms as untranslatable. Such untranslatability may be also attributed to the use of European languages and cultures to understand languages and cultures that are non-European. Therefore, attempting to ‘deconstruct the well-established practice of employing Eurocentric terms to describe, label, and define other languages, especially in cross-linguistic syntax’, as Rashwan (Citation2020, p. 363) notes is significant. What may also warrant conducting a study like the current one is that while linguistic attempts concentrated on classifying languages based on ‘manner’ and ‘path’, such attempts did not seem to focus on the conceptual semantics of verbs of human locomotion. Thus, based on the existence of such research gaps, we attempted to demonstrate similarities and/or differences between the verbs ‘jogging’ and ‘strolling’ and ‘yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’. To do so, we adopted the Natural Semantic Metalanguage Approach, and we relied on the English semantic primes and their Arabic counterparts as proposed by AlBader (Citation2016) to create a sematic template consisting of Lexicosyntactic Frame, Prototypical scenario, Manner, and Prototypical outcome. Since creating a semantic template requires an understanding of how the verbs we analyzed are conceptualized and lexicalized, we based our analysis solely on consulting English and Arabic monolingual dictionary entries.

Our study comprised five sections and proceeded as follows: In Section 2, we provided a review of related literature written on verbs of human locomotion and pinpointed the research gaps existing in the current literature. This section also highlighted the significance of the current study. In Section 3, we explained the theoretical framework adopted by our study, its analysis tools, and the steps according to which we conducted our analysis. In Section 4, we provided a detailed analysis of the verbs selected by the present study. We began with our identification of core notions in the conceptualization and lexicalization of these verbs, the four semantic explications we proposed for each verb based on the English and Arabic semantic primes and the analysis template we adopted. We concluded this section by highlighting the results of our analysis. In Section 5, we concluded the study by summarizing its major findings, and highlighting remaining gaps that could present possible venues for future research.

2. Literature review

Motion is one of several concepts through which different languages construct their view of the world. It is also a concept that received considerable attention from Cognitive Linguistics and cross linguistic research. Such attention led, as a result, to the emergence of attempts aiming at elucidating how motion is conceptualized as manifested by language users in a relatively similar manner as Blomberg (Citation2014, p. 3) notes. However, this assumption was soon proven to be inaccurate, especially, after cross-linguistic research and experiments revealed the existence of typological differences in the portrayal and expression of motion because of existing differences across languages in the conceptualization of motion.

One of the greatest contributions which drew attention to the existence of typological differences in the conceptualization of human locomotion is that of Talmy (Citation1985). He proposes four basic semantic components (i.e. figure, ground, path and manner) that enable the analysis of motion events. Talmy (Citation1972, Citation1975, Citation1985) also notes that figure refers to the moving or located entity, ground refers to the entity which performs the function of a spatial reference point to the motion or location of the figure, while path refers to the figure’s motion path, and manner refers to the figure’s motion manner along the path. After comparing how grammar encodes manner and path, Talmy (Citation1985) reveals that languages pack information related to motion events using limited lexicalization patterns. He also adds that manner and path as expressed across different languages can be classified into: manner incorporating (manner is expressed in the main verb), path incorporating (path instead of manner is expressed in the main verb and ground incorporating (shape and consistency which are salient properties of ground are expressed in the main verb). Talmy’s (Citation1985) work inspired several studies. It also emphasized and provided evidence supporting the tightknit relationship between the typological theory and construction grammar as noted by Croft (Citation2001, Citation2008). Despite the contributions that it made, Talmy’s (Citation1985) work received some criticism, especially by Slobin (Citation2006, p. 59) who criticized Talmy’s (Citation1985) definition of manner for being ambiguous. Despite such criticisms, Goddard et al. (Citation2016, p. 305) note that Talmy’s (Citation1985) motion was an effective umbrella term due to encompassing motor pattern, rate of motion, force dynamics, and attitude i.e. motion-related aspects. However, and from a lexicalization research perspective, Talmy’s (Citation1985) contribution to explicating the specifics of manner-of-motion was faced with disinterest.

Talmy’s (Citation1985) views and classification of manner and path inspired several works including (Berman & Slobin, Citation1994), (Slobin, Citation1996, Citation2004), (Slobin & Hoiting, Citation1994), and (Özçalışkan & Slobin, Citation2000). Such works aimed to test and validate Talmy’s (Citation1985) typology. They also aimed to provide evidence supporting the existence of differences in the conceptualization of human locomotion events across languages. The researchers mentioned above relied on the Frog Story picture book (i.e. a twenty-four-page story book about a boy and his pet dog who go searching for the boy’s pet frog that escaped) to collect their data and to examine how native speakers of distinct twenty-one languages including English, Turkish, and Spanish described motion events. Their data analysis confirmed the prediction made by the typology and they concluded that native speakers of Romance languages such as French and Spanish preferred using Path when describing motion events while native speakers of Germanic languages such as English and German preferred to use Manner.

Malt and Wolff (Citation2010) expressed a similar interest in investigating differences in the manner of motion across languages and conducted a study in which they tested whether languages such as English, Dutch, Spanish and Japanese differ in terms of describing manner of motion or not. To collect their data, the researchers used video clips of a person on a treadmill performing different forms of movement including trudging, skipping, and strolling which is a different tool in comparison to the studies cited above. The researchers concluded after analysis of the descriptions given that there is a gap between ‘walking’ and ‘running’. Within the same lines and in an attempt to provide a fine-grain comparative analysis of two verbs of human locomotion i.e. ‘walking’ and ‘running’ in German and English, Goddard et al. (Citation2016) adopted the Natural Semantic Metalanguage approach and proposed semantic explications for the verbs ‘walking’ and ‘running’ in English and German. After analysis of their explications, the researchers concluded that even in the case of closely related languages such as English and German, significant differences in conceptualizing manner of motion exist. In a manner similar to that of Malt and Wolff (Citation2010) and (Goddard et al., Citation2016), Kudrnáčová (Citation2021) examined differences in how English and Czech conceptualize ‘walking’. By relying on data from Intercorp (a synchronized translation corpus), Kudrnáčová (Citation2021) conducted a cognitive contrastive semantic analysis of the English human locomotion verb ‘walking’ and its Czech equivalents ‘jít’ and ‘kráčet’. She concluded that English and Czech do not portray walking in the same way. She added that unlike English, the Czech ‘jít’ and ‘kráčet’ focused on the position of the body and leg movement and that even in Czech, the verb ‘kráčet’ emphasized verticality of the body, and leg movement more than ‘jít’ which placed, as a result, the English ‘walking’ somewhere in between these two verbs.

Verbs of human locomotion also received research interest in another language pair i.e. English and Romanian where Bodean-Vozian & Cincilei (Citation2019) analyzed comparatively how human motion is conceptualized. The researchers relied on two corpora of the novel The Lord of the Rings to extract and analyze examples demonstrating the challenges posed by typological differences between SLs, TLs and translation strategies used to translate manner and human locomotion. The researchers concluded that: A) Manner of motion verbs in English were larger in range and more expressive in comparison to Romanian. B) Unlike English, Romanian encoded motion with path, thus, subjecting manner to omission or subordination by gerunds or adverbs.

Cifuentes Férez (Citation2007) tested whether English and Spanish arrange verbs of human locomotion similarly and whether any of these two languages has a larger range of verbs in addition to ‘walking’, ‘running’ and ‘jumping’ verbs. Unlike the previous studies, Cifuentes Férez (Citation2007) conducted two experiments: the Free Verb Listing task and the Rating task where participants were given a list of 108 English verbs and 54 Spanish verbs to rate. After analyzing the responses given, she concluded that: A) English and Spanish follow the pattern of lexicons organization even though English has more manner verbs than Spanish. B) Many verbs in both languages focus on depicting ways of walking in comparison to ‘running’ and ‘jumping’. C) Verbs given to participants for rating were mostly rated as good ways or kinds of motor patterns, while a few verbs such as trip in Spanish and English were rated as not good ways or kinds of motor patterns. Cifuentes Férez (Citation2007) also found that some verbs including rush, and scoot were good ways or kinds of two superordinate categories.

Unlike all previous studies, Yuan (Citation2009) investigated verbs of human locomotion in English and Chinese by relying on Language Typology and Comparative Semantics principles. The researcher aimed to (1) Determine which language places more emphasis on and pays closer attention to manner specification, (2) Identify lexicalization patterns used by the two languages, (3) Identify the manner salience in verbs analyzed in the two languages, and (3) Explain how human locomotion verbs in English and Chinese are similar and/or different in terms of lexicalization patterns and manner specifications. Yuan (Citation2009) concluded that English and Chinese share semantic similarities and differences in relation to verbs of human locomotion. The researcher also added that in comparison to Chinese, English exhibits a higher degree of lexicalization of this type of verbs and that English should be placed at a higher place than Chinese on high-manner end.

Human locomotion verbs also received research interest in Arabic where some studies including Al-Qarni (Citation2010) and Abdulrahim (Citation2013) investigated the conceptualization and lexicalization of human locomotion verbs in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Al-Qarni (Citation2010) aimed to fill in an existing research gap that often overlooked other patterns of motion lexicalization in linguistic investigations of motion by examining lexicalization patterns of motion and the semantics of motion verbs in Arabic. She adopted Talmy's (Citation1985) theory of motion conceptualization: Figure-Ground-Move-Path as her theoretical framework. After surveying patterns of general conflations and grammatical realizations of motion in Arabic, Al-Qarni (Citation2010) concluded that: 1) Conflation of motion with direction in the verb of motion was the most notable pattern of motion lexicalization in Arabic. 2) The notion of path in Arabic path verbs was realized linguistically in some while not in others. 3) Arabic manner of motion verbs were different from those found in English and they constituted a smaller set-in comparison to English. 4) Just like any other language, the lexicon of Arabic motion verbs could express different types of manner and path. Abdulrahim (Citation2013) adopted a different approach to studying motion verbs in Arabic than that of Al-Qarni (Citation2010). She relied on a corpus-based and a constructionist approach in her investigation of three GO verbs (dahaba, madā, and rāha) and four COME verbs (atā, hadara, gˇā’a, and qadima). Abdulrahim (Citation2013) used qualitative and quantitative analysis methods in her examination of contextual features such as inflectional marking, syntactic frames, semantic features of collocating lexical items, and the way motion events are conceptualized and understood in Arabic. Abdulrahim (Citation2013) concluded that the presence of multiple verbs expressing GO and COME was not a matter of embellishing the language, but in fact, the presence of several verbs supported the fact that motion is a conceptually complex event whose meaning is context independent.

The studies reviewed above highlight the existence of several research gaps which the current study attempts to fill. One research gap is that a limited number of studies adopted the Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM) approach to comparatively analyse two verbs of human locomotion as it was the case in Goddard et al. (Citation2016). Another gap is that unlike other language pairs which received adequate research attention, Arabic received minimal attention in terms of analysing verbs of human locomotion as well as comparing the conceptualization and lexicalization of such verbs to English. A third gap is that existing Arabic literature does not seem to be interested in analyzing the human locomotion verbs ‘walking’ and ‘running’ in Arabic unlike other studies such as (Cifuentes Férez, Citation2007), and (Kudrnáčová, Citation2021).

Our study stands different in several ways. First, we opt for a similar approach to Goddard et al.’s (Citation2016) by adopting the NSM approach to propose semantic explications which facilitate achieving our objectives. Second, we contrast Arabic with English; a different language pair than the ones analysed by previous studies. Third, we focus on the English verbs of human locomotion ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ and their Arabic counterparts which have not been contrastively analysed by any of the studies above.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model of analysis

3.1.1. The NSM Approach, and NSM semantic templates for verbs of physical activity

The Natural Semantic Metalanguage Approach (henceforth NSM) developed by Wierzbicka, (Citation1996) which we adopted in our study is one that provides a tool which enables the systematic description of all meanings in all languages by means of reductive paraphrases. Such reductive paraphrases, also known as semantic explications, are formulated using semantic primes which consist of 65 semantic exponents in total. These primes possess inherent and combinatorial features. Such features make them an optimal tool for semantic-conceptual analysis due to the impossibility of their reduction by means of paraphrase, and their universality which means that they are lexicalized in all languages including Arabic and English. Thus, we adopted them as our analysis tool.

Since our study also dealt with verbs of human locomotion, i.e. physical activity verbs, we used the template which (Goddard et al., Citation2016) used in the analysis of physical verbs which comprised the following sections:

3.1.1.1. Lexicosyntactic Frame

In this section, we highlight commonalities of all verbs analyzed such as having a human actor, a locus expression, and a concurrent localized movement which the human actor controls.

3.1.1.2. Prototypical Scenario

A proposed scenario for verbs of human locomotion where a human actor is depicted doing something which results in his/her movement from his/her original location to another one after some time lapses. It may also involve pinpointing what Goddard et al. (Citation2016) refers to as ‘Prototypical Motivation’ such as exercising, pleasure or escaping.

3.1.1.3. Manner

As its name suggests, Manner involves describing how verbs being analyzed are performed. In other words, it involves emphasizing the repetitiveness of the action in addition to describing how body parts’ interactions result in an overall effect on the body including changes in posture or changes in position leading to the forward movement of the body.

3.1.1.4. Potential Outcome

Potential Outcome focuses on describing what happens because of repeating the action long enough and for a period of time such as the actor ending in a different location from that in which the action started or being far from the location in which the action began.

3.2. Analysis procedure

To meet our objectives, we proceeded as follows:

Stage1: Consult English monolingual online dictionaries including Merriam-Webster, Macmillan, Oxford learner’s Dictionary, and Cambridge Dictionary to identify semantic molecules in meanings provided by each dictionary. Doing so aids in understanding how the two verbs, ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’, are conceptualized and lexicalized, thus, facilitating the creation of a semantic template for these verbs.

Stage 2: Propose NSM explications for the verbs ‘Jogging’ and ‘Strolling’ using the semantic prime exponents in Goddard (2007).

Stage 3: Conduct a comparative analysis of differences and similarities detected in explications proposed for the two English Verbs.

Stage 4: Consult Arabic monolingual dictionaries including Mu’jam maqayis al-lughah by Aḥmad Ibn Fāris al-Qazwīnī, Lisān al-ʿArab by ibn Manzūr, Mu’jam al-lughah al-’arabīyah al-mu’āṣirah by Ahmed Mukhtar Omar to analyze the Arabic counterparts and identify semantic molecules and create a semantic template for ‘yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’.

Stage 5: Propose NSM explications for ‘yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’ using the sematic prime exponents proposed by AlBader (Citation2016).

Stage 6: Analyze the semantic explications created for ‘jogging’ and ‘strolling’ in English and Arabic to identify differences and similarities in conceptualizing these human locomotion verbs.

Stage 7: Conclude the study by stating major findings and avenues for future research.

4. Results and discussion

This section is dedicated to contrastively analyse the verbs ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ and their Arabic counterparts. The first part of the section focused on analysing the English verbs. This was done by consulting monolingual dictionaries, then proposing a comprehensive sematic explication of the two verbs using the semantic primes and the sematic template we adopted. The second part of this section focused on the analysis of the Arabic counterparts where we adopted a similar method to the one used to analyse the English verbs.

4.1. English strolling vs. jogging

The use of monolingual dictionaries aids in shedding light on how conceptually different ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ are when compared to one another. As illustrated below (see ), strolling or stroll is defined by Merriam Webster (2022), Cambridge Dictionary (2022), McMillan Dictionary (2007), and Oxford Learner’s Dictionary (2022) as follows:

Table 1. Definitions Provided for ‘Stroll’ by Merriam Webster (Citation2022a), Cambridge Dictionary (Citation2022a), Macmillan Dictionary (Citation2007a), and Oxford Learner’s Dictionary (Citation2022a).

illustrates similarities shared by the three definitions in their conceptualization of ‘strolling’. The first of these similarities is how ‘strolling’ is defined as ‘walking’. Thus, on a spectrum of all verbs of human locomotion, ‘strolling’ is placed in a position that is closer to ‘walking’ than that of ‘running’; i.e. ‘strolling’ is a form of ‘walking’. In addition, the four definitions conceptualize the manner of ‘strolling’ similarly where it is defined as an action done in a ‘slow’, ‘without hurrying’ ‘relaxed’ manner. This focus on the relaxed pace of ‘strolling’ implies that ‘strolling’ does not involve a sense of urgency. The four definitions also demonstrate a similar purpose of ‘strolling’ where it is done for ‘pleasure’ or ‘leisure’.

Table 3. Definitions of ‘Yatanazzah’ in Mu’jam maqayis al-lughah (1979a), Lisān al-ʿArab (1993a), Mu’jam al-lughah al-’arabīyah al-mu’āṣirah (2008a)

Using the semantic primes in Goddard and Wierzbicka (Citation2014) and the explication template in Goddard et al. (Citation2016), we propose the following explication for the human locomotion verb ‘stroll’, and we notate the semantic molecules i.e. the core concepts in the conceptualization of ‘strolling’ by an [m]:

The explication above despite its length provides a detailed description for the act of strolling which allows a language user to understand that:

Strolling is an action performed using the legs and feet just like other human locomotion activities that involve using lower limbs and body parts.

It is a repetitive and an alternating action: movement of legs and feet must happen more than once, and a switch must take place between a person’s legs and feet.

It involves two places i.e. a starting point and a destination.

Strolling is an action whose speed is like that of walking which is a slow one.

It is an action whose purpose and outcome are relaxing or entertainment i.e. feeling good.

How do ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ differ from one another? And do they share any similarities in conceptualization? The first step to answer these questions is to consult monolingual dictionaries to identify core notions in the conceptualization of ‘jogging’ as illustrated in below:

Table 2. Definitions Provided for ‘Jog’ by Merriam Webster (Citation2022b), Cambridge Dictionary (Citation2022b), Macmillan Dictionary (Citation2007b), and Oxford Learner’s Dictionary (Citation2022b).

In definitions (1), (3), (4), (5), ‘jogging’ is defined as ‘running’ while in definition (2), it is defined as ‘going’. Unlike ‘running’, ‘jogging’ is slower. This difference in terms of speed is highlighted by using words and phrases such as ‘slow’, ‘regular speed’, ‘steady speed’. ‘Jogging’ is also defined as a purposeful activity where it may be done for the purpose of exercise or pleasure as seen in definitions (2), (3), (4), and (5). Interestingly, definitions (2) and (5) expand the meaning of ‘jogging’ by focusing on duration and repetitiveness where in definition (5), the phrase ‘for a long time’ is used and in definition (2), the word ‘monotonous’ is used. The significance of using such words/expressions can be clearly seen in helping a language user/learner to understand that ‘jogging’ is closer to running in terms of meaning if compared to ‘walking’ for instance.

The second step that would assist with answering our two questions is to propose a semantic template for ‘jogging’. Thus, based on the five definitions above, and by using the same template that we used for the analysis of ‘strolling’, we propose the following semantic explication for ‘jogging’:

Semantic explications proposed for the two verbs using the NSM template for physical activity verbs reveal the presence of similarities in the conceptualization of ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’. One of these similarities is in the Lexicosyntactic Frame where both verbs talk about ‘doing something for some time’ which results in ‘moving in this place’. The presence of these elements in both explications indicates that both verbs denote an action carried out by a human subject (I) for a short or a long period of time. This leads to a change in that subject’s place where he/she moves further from the starting point and closer to a destination. A second similarity is in how both verbs convey some aspect of the subject’s control over these actions where both explications state performing the action as the speaker i.e. I ‘want(s)’. The Prototypical Scenario section of the template reveals that both verbs convey the motive of performing these two actions i.e. wanting to ‘feel good’ or ‘think good’ in addition to describing the destination of the action as ‘not near’ the starting point. This similarity can be rationalized by the fact that ‘strolling’ and jogging can be performed for the purpose of pleasure and/or exercise which could result in feeling good and thinking good i.e. having fun and relaxing. The third section of the template i.e. Manner demonstrates a fourth similarity between the two verbs where both verbs require legs [m], feet [m] and a solid floor i.e. the ground [m] to perform the action. The same section also emphasizes forward movement of the body though the use of the molecule: in front of [m]. A final similarity is demonstrated by the last section of the template Potential outcome where both verbs denote achieving a goal i.e. reaching a destination farther than the starting point and achieving the purpose for which the action was performed: relaxing, having fun and/or exercising.

Explications [A] and [B] also reveal differences in the conceptualization of ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’. One difference is evident in the Prototypical Scenario section where a person gets to ‘somewhere else’ after a ‘short time’ when he/she is ‘jogging’ while when they are ‘strolling’, they get ‘somewhere else’ after a ‘some time’. The use of ‘short time’ and ‘some time’ allows marking both verbs as different in terms of speed, especially, since’ jogging’ as seen earlier is defined as ‘running’ while ‘strolling’ is defined as ‘slow walking’. However, unlike the sense of urgency that normally sets ‘walking’ apart from ‘running’, this sense of urgency is absent in ‘jogging’. The Manner section indicates additional differences in the conceptualization of ‘strolling’ and’ jogging’ including the speed at which the legs alternate, their relationship with the ground and the duration of their contact with it the moment they touch it. For example, when a person jogs, his/her legs move at a moderate speed ‘not quickly, not slowly’ yet when the same person strolls, his/her legs move at a slower speed than that of ‘jogging’. This may be attributable to the fact that strolling is a type of walking and jogging is a type of running, thus, a difference of speed must exist to allow accounting for other types of ‘walking’ and ‘running’ which we do not consider in our study. In addition, when a person’s feet alternate while jogging, one foot becomes above the ground for a shorter period than the duration that the same foot spends above the ground while strolling. Duration of contact with the ground also reveals how ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ differ where when a person strolls, his/her foot stays on the ground for some time but when they jog, their foot stays on the ground for ‘a short time’.

4.2. Arabic ‘yuharwil’ vs. ‘ yatanazzah ‘

‘Yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’ are two Arabic verbs of human locomotion that represent potential counterparts of the English verbs ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’. As seen in the previous section, ‘jogging’ and ‘strolling’ shared both similarities and differences in conceptualization, but what about Arabic? Do the verbs ‘yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’ share any similarities or are they conceptualized differently? To answer these two questions, and understand how ‘yuharwil’ and ‘yatanazzah’ are conceptualized in Arabic, we consult the following Arabic monolingual dictionaries (see ):

which provides definitions of ‘yatanazzah’ as stated in three dictionary entries reveals that:

‘yatanazzah’ denotes going outdoors to an open area that is covered in grass and full of trees. This is illustrated by using the word ‘al-rīāḍi’ which means a garden, a park or an open area that is covered in grass.

Since ‘yatanazzah’ means ‘going to a place’, then it implies movement which can be carried out by using one’s body (the legs or feet) or by using a vehicle. However and for the purpose of our study, we exclude carrying out the action of ‘yatanazzah’ using a vehicle since we focus on verbs of human locomotion which denote using one’s body.

It involves moving to a place that is very far from the starting point a person or a group of people left from.

It is an action that may be carried out by an individual or a group of people. This is understood from the use of words like ‘alʾusratu’ and the pronoun ‘na’ in ‘kharajnā’ which may be used to refer to dual or plural subjects.

It is a purposeful activity done for the purpose of entertainment, fun, and renewal of one’s energy.

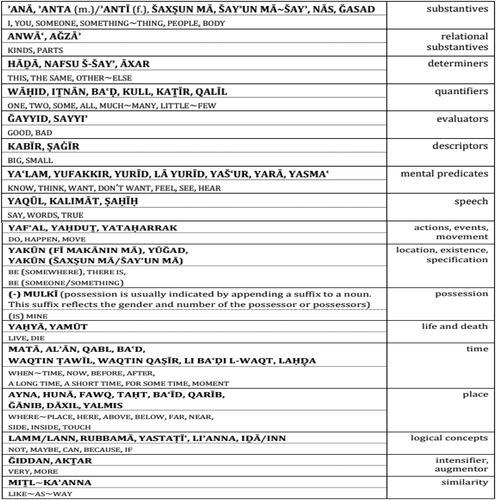

Based on the Arabic counterparts of the English primes provided by AlBader (Citation2016) (see ), and the same template adopted to analyse ‘jogging’ and ‘strolling’, we propose the following explication for ‘yatanazzah’:

‘Yatanazzahu’ is a controlled human locomotion activity carried out by a human subject and it’s one that lasts for some time. It can also be described as a location bound activity which has a starting point and a destination as depicted in the Prototypical Scenario section of the template. The Prototypical Scenario section emphasizes that the distance between its starting point and destination is very far. Since ‘yatanazzah’ is an activity done for the purpose of entertainment and leisure, it does not involve urgency. This is seen in the Manner section of the template where ‘yatanazzah’ entails using and moving one’s legs and feet in a particular way, but not quickly. The same section also demonstrates that ‘yatanazzah’ involves forward body movement. This is made clear in the preposition ʾamāma (in front of). As for the last section of the potential outcome, if the action was repeated and lasted for some time, then a person becomes very far from the place where he/she started.

What about ‘yuharwil’? Does Arabic exhibit any similarities and/or differences in its conceptualization of ‘yuharwil’if compared with ‘yatanazzah’? The following part (see ) attempts to answer these two questions.

Table 4. Definitions of ‘Yuharwil’ in Mu’jam maqayis al-lughah (1979b), Lisān al-ʿArab (1993b), Mu’jam al-lughah al-’arabīyah al-mu’āṣirah (2008b).

which provides the three Arabic dictionary entires' definition of 'yuharwil' demonstrates the following:

All three definitions provided for the human locomotion verb ‘yuharwilu’ place the verb in an intermediary position between ‘almashyi wa-al-’adwi’ yet it is placed at a higher level than that of ‘almashyi’ on a spectrum of human locomotion.

Unlike definition (1), definitions (2) and (3) use ‘ʾasra’a’ and ‘alʾisrā’u’ which add speed due to a sense of urgency.

In comparison to definitions (1) and (3), definition (2) adds a religious significance to the meaning of ‘yuharwilu’ where part of its meaning denotes a ritual performed by men in Hajj or Umra at Al Safa wa Al Marwa. However, since our study does not focus on the religious semantics of this verb, we exclude it from our analysis.

We propose the following explication for the verb ‘yuharwilu’ based on how similar and different the three definitions provided for the Arabic verb of human locomotion ‘yuharwilu’, and based on the semantic primes used for explicating the verb ‘yatanazzahu’ as proposed by AlBader, (Citation2016):

Explication [E] provides a comprehensive description ‘yuharwilu’ which, in turn, facilitates defining unique aspects which makes it different from ‘yatanazzah’ such as:

‘yuharwilu’is an action that is performed using both legs and feet.

It involves alternation and repetition.

It involves two places i.e. a starting point and a destination.

It is an action whose speed is faster than that of ‘almashyi’(walking).

Proposed explications for the verbs ‘yatanazzahu’ and ‘yuharwilu’i.e. [C] and [D] reveal some similarities and differences in terms of conceptualization. Such similarities include that both verbs entail a forward movement of the body, they both involve the use of identical body parts i.e. legs and feet which alternate when performing these two actions, and they both involve two places i.e. a starting point and a destination. Explications [C] and [D] also reveal conceptualization differences in terms of speed, and purpose. For example, when a person is ‘yatanazzahu’, he/she moves their legs and feet at a slower pace than that of ‘yuharwilu’. This is made clear in the duration of contact with the ground where in the case of ‘yuharwilu’, this contact is fast due to the presence of a sense of urgency unlike ‘yatanazzahu’. The two verbs also differ in terms of purpose where ‘yatanazzahu’ is only performed for the purpose of entertainment, and leisure.

What do explications [A], [B], [C], and [D] reveal about the English ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’, and their Arabic counterparts ‘yatanazzahu’ and ‘yuharwilu’? The answer to this question can be summarized as follows:

All verbs analysed and due to being verbs of human locomotion share several elements of conceptualization such as the use of legs and feet to perform the actions, having a starting point and a destination, alternation and repetition of body parts’ movement, and denoting forward body movement based on the position of the performer’s body.

In relation to speed and urgency, explications [B] and [D] reveal that ‘jogging’ is not the same as ‘yuharwilu’. This is because the former is done at a moderate speed and implies urgency while the latter is done quickly and implies urgency.

Duration of contact with the ground in the case of ‘strolling’ and ‘yatanazzahu’ is similar since contact with the ground happens for some time. Duration of contact with the ground is also the same in the case of ‘jogging’ and ‘yuharwilu’ where such contact is shorter when compared to ‘strolling’ and ‘yatanazzahu.’

Explications also reveal that in relation to purpose and outcome, ‘jogging’, and ‘strolling’ are motivated by a person’s desire to exercise and/or relax i.e. feel good. However, the conceptualization of ‘yuharwilu’ does not entail this and the conceptualization of ‘yatanazzahu’ emphasizes the purpose of entertainment only.

5. Conclusion

Understanding how human activities are performed by exploring how they are conceptualized and lexicalized within a linguistic system is important to gain a better understanding of how languages are unique in a non-hegemonic light.

After surveying existing literature written on verbs of human locomotion, several research gaps became apparent. Such gaps included the limited number of studies that adopted the NSM approach to conduct a comparative analysis of verbs of human locomotion, the limited research attention that English and Arabic as a language pair received, and the little to no interest exhibited by existing Arabic literature in analyzing the Arabic counterparts of ‘jogging’ and ‘strolling’. Thus, in our attempt to bridge the existing gaps, we aimed to demonstrate whether an understudied language pair such as Arabic and English lexicalizes the verbs ‘strolling’, jogging’, ‘yuharwilu’ and ‘yatanazzahu’ similarly or differently. To achieve this objective, we adopted the NSM Approach, consulted monolingual Arabic and English dictionaries, and proposed semantic explications for these verbs.

Our analysis yielded several interesting findings. First, we noted the presence of several differences including duration and length of action, pace and speed, as well as urgency. We attributed the existence of such differences to the existence of other types of ‘walking’ and ‘running’ which we did not consider in our study. Second, after proposing sematic explications of the Arabic counterparts ‘yuharwilu’ and ‘yatanazzahu’ and analyzing them, we observed the presence of similarities as well as differences. On the one hand, similarities included entailing forward movement, using the same body parts while performing the actions, as well as having a starting point and a destination. On the other hand, differences observed included differences in terms of speed and pace as well as differences in terms of purpose. Third, despite belonging to unrelated language families, English and Arabic shared several similarities in their conceptualization and lexicalization of ‘strolling’, ‘jogging’, ‘yuharwilu’ and ‘yatanazzahu’. Such similarities included the use and alteration of the same body parts, denoting forward movement, and having a starting point and a destination. Fourth, English and Arabic differed significantly in terms of conceptualization where English focused on assigning a purpose for its verbs ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ while Arabic either assigned a different purpose, no purpose, or focused on elements that English did not show interest in such as the place in which the action is being carried out. In addition, we found differences in terms of speed and urgency especially in the case of ‘jogging’ which was done at faster pace when compared to its Arabic counterpart. These findings corroborate those of Malt and Wolff (Citation2010) where English and Arabic just like the languages that Malt and Wolff (Citation2010) analyzed showed a discontinuity in the lexical conceptualization of ‘strolling’, ‘jogging’, 'yuharwilu' and ‘yatanazzahu’ which is expected to impose constraints on lexical content of these verbs. Our findings also corroborate those of Goddard et al. (Citation2016) by providing additional evidence for the existence of semantic-conceptual differences between ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ and ‘yuharwilu’ and ‘yatanazzahu’ which are often offered as potential translation equivalents of the English verbs. The current study provides corroborating evidence for the findings of Kudrnáčová (Citation2021) who concluded that English and Czech are different in their conceptualization of ‘walking’ which may be attributed to both languages being unrelated which has been the case in English and Arabic. Since our study relied on Arabic counterparts of the English Semantic Primes as proposed by AlBader (Citation2016), we noted that such counterparts have proven to be efficient. This efficiency means that these Arabic counterparts may be utilized to explore Arabic verbs of human locomotion other than the ones we explored.

As for future research venues, future studies may explore other verbs of human locomotion in English and their Arabic counterparts as findings of such studies may corroborate or contradict ours. They may also examine Arabic verbs of human locomotion by pairing Arabic with other languages belonging to the same family such as Hebrew or German or pair Arabic with other non-relative languages such as French or Spanish. Future research may examine the translation strategies used to translate verbs of human locomotion in general and those with religious meanings from Arabic into English in particular. Regardless of the venue that future research may opt for, it is important for future studies to attempt to identify universal traits of verbs in a non-European language such as Arabic and attempt to compare such traits to those found in European languages such as English. It is only then and by adopting a non-hegemonic system that the uniqueness of languages may be truly understood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nada Alhammadi

Nada Alhammadi holds the academic rank of a lecturer and joined the Department of Foreign Languages at the University of Sharjah in 2014. She obtained her BA degree in English Language and Literature with a minor in Linguistics and Translation from the University of Sharjah in 2011. In 2014, she obtained her MA degree in Translation from the same university and obtained her CELTA license which was offered by the University of Sharjah in collaboration with the University of Cambridge. She is currently pursuing her PhD in Linguistics and Translation. Her research interests include Audio Visual Translation, Comparative Semantics, Contrastive Linguistics, CDA, and Explicitation and Implicitation.

Sane Yagi

Sane M. Yagi received his education in Jordan, USA, and New Zealand. He is currently a Professor of Linguistics at the University of Sharjah and the University of Jordan. The primary themes are corpus development, computational lexicography and lexicology, computational morphology, syntactic parsing, automatic punctuation, and machine learning. His research interests include computational linguistics, CMC, CALL, and TEFL.

References

- Abdulrahim, D. (2013). A corpus study of basic motion verbs in modern standard Arabic [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Alberta, ProQuest One Academic. DAIA 75/06(E), Dissertation Abstracts International. https://uoseresources.remotexs.xyz/user/login?dest=?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/corpus-study-basic-motion-verbs-modern-standard/docview/1504609626/se-2?accountid=42604

- AlBader, Y. B. (2016). Arabic Semantic Primes with English equivalents. Academia. https://www.academia.edu/28156768/Arabic_Semantic_Primes_with_English_equivalents

- Al-Qarni, S. (2010). Conceptualization and lexical realization of motion verbs in standard written Arabic [Doctoral dissertation]. King AbdulAziz University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275823288_Conceptualization_and_Lexical_Realization_of_Motion_Verbs_in_Standard_Written_Arabic

- Berman, R. A., & Slobin, D. I. (1994). Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Erlbaum.

- Blomberg, J. (2014). Motion in Language and Experience: Actual and non-actual motion in Swedish, French and Thai [Doctoral dissertation]. Centre for Languages and Literature. Research Portal at Lund University. https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/motion-in-language-and-experience-actual-and-non-actual-motion-in

- Bodean-Vozian, O., & Cincilei, C. (2019). Talking about human locomotion: a contrastive analysis based on the English and Romanian narratives. Linguistics and Literary Science, 4(124), 1–15. http://dspace.usm.md:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/2353/04.-p.26-331.pdf?sequence=1

- Brierley, C., Sawalha, M., Heselwood, B., & Atwell, E. (2016). A Verified Arabic-IPA Mapping for Arabic Transcription Technology, Informed by Quranic Recitation, Traditional Arabic Linguistics, and Modern Phonetics. Journal of Semitic Studies, 61(1), 157–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgv035

- Cifuentes Férez, P. (2007). An experimental investigation into English and Spanish human locomotion verbs. International Journal of English Studies, 7(1), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.6018/ijes.7.1.48931

- Croft, W. (2001). Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Croft, W. (2008). Methods for finding language universals in syntax. In Sergio Scalise and Elisabetta Magni (Eds.), With more than chance frequency: Forty years of universals of language (pp. 147–164). Springer.

- Goddard, C., & Wierzbicka, A. (2014). Words and meanings: Lexical semantics across domains, languages and cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goddard, C., Wierzbicka, A., & Wong, J. (2016). “Walking” and “running” in English and German: The conceptual semantics of verbs of human locomotion. Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 14(2), 303–336. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.14.2.03god

- Kudrnáčová, N. (2021). Contrastive semantics of human locomotion verbs: English walk vs. Czech jít and kráčet. In Wei-lun Lu, Naděžda Kudrnáčová and Laura A. Janda (Eds.), Corpus Approaches to Language, Thought and Communication. Benjamins Current Topics (pp. 53–77) John Benjamins. https://benjamins.com/catalog/bct.119

- Malt, B. C., & Wolff, P. (2010). Words and the mind: how words capture human experience. Oxford University Press.

- Özçalışkan, Ş., & Slobin, D. I. (2000). Expression of manner of movement in monolingual and bilingual adult narratives: Turkish vs. English. In A. Göksel, & C. Kerslake (Eds.), Studies on Turkish and Turkic languages. Harrasowitz.

- Rashwan, H. (2020). Arabic jinās is not pun, wortspiel, calembour or paronomasia: A post-Eurocentric comparative approach to the conceptual untranslatability of literary terms in Arabic and ancient Egyptian cultures. Rhetorica, 38(4), 335–370. https://doi.org/10.1525/rh.2020.38.4.335

- Slobin, D. I., & Hoiting, N. (1994). Reference to Movement in Spoken and Signed Languages: Typological Considerations. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 20(1), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v20i1.1466

- Slobin, D. I. (1996). From "thought and language" to "thinking for speaking. In J. J. Gumperz & S. C. Levinson (Eds.). Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 70–96). Cambridge University Press.

- Slobin, D. I. (2004). The many ways to search for a frog. In S. Stromquist, & L. Verhoeven (Eds.), Relating Events in Narrative: Typological and Contextual Perspectives (pp. 219–258). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Slobin, D. I. (2006). What makes manner of motion salient? Explorations in linguistic typology, discourse, and cognition. In M. Hickmann & S. Robert (Eds.), Space in languages: Linguistic systems and cognitive categories (pp. 59–81). John Benjamins.

- Talmy, L. (1985). Lexicalization patterns: Semantic structure in lexical forms. Language typology and syntactic description. In T. Shopen (Ed.). Grammatical categories and the lexicon (pp. 57–149). Cambridge University Press.

- Talmy, L. (1972). Semantic structures in English and Atsugewi [Doctoral dissertation]. University of California. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5g15p348#main

- Talmy, L. (1975). Semantics and syntax of motion. In John Kimball (Eds.). Syntax and Semantics (Vol. 4, pp. 181–238). Academic Press.

- Wierzbicka, A. (1996). Semantics: Primes and universals. Oxford University Press.

- Yuan, W. (2009). A Study of Language Typology and Comparative Semantics: Human Locomotion Verbs in English and Chinese [MA dissertation]. Beihang University. https://www.linguistics-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Thesis-Wenjuan-Yuan.pdf

English Dictionary Entries

- Cambridge University Press. (2022a). Jog. In Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/jog

- Cambridge University Press. (2022b). Stroll. In Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/stroll

- Macmillan. (2007a). Stroll. In M. Rundell (Ed.), Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (Second Edition, p.916). Macmillan.

- Macmillan. (2007b). Jog. In M. Rundell (Ed.), Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (Second Edition, p.812). Macmillan.

- Merriam Webster. (2022a). Jog. In Merriam-Webster.com.Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jog

- Merriam Webster. (2022b). Stroll. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stroll#synonyms

- Oxford University Press. (2022a). Jog. In Oxford Learner’s Dictionary. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/jog_1?q=jog

- Oxford University Press. (2022b). Stroll. In Oxford Learner’s Dictionary. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/stroll_1?q=strolling

Arabic Dictionary Entries

- Ibn Manzur. (1993). Naziha. Lisan al Arab. Volume 11, (pp.549). Dar-Sader. Beirut. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://al-maktaba.org/book/21710/2524#p1م

- Ibn Manzūr. (1993). Harwala. Lisān al-ʿArab. Volume 11, (pp.595). Dar-Sader. Beirut.Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://al-maktaba.org/book/34077/7110#p1

- Majma Al-Lughah Al- Arabiyah. (1999). Tanazzaha. al-Mujam al-wajiz. (p.611). Majma Al-Lughah Al- Arabiyah. Cairo.

- Majma Al-Lughah Al- Arabiyah. (1999). Harwala. al-Mujam al-wajiz. (p.649). Majma Al-Lughah Al- Arabiyah. Cairo.

- Ibn Fāris al-Qazwīnī, Aḥmad. (1979). Harala. Mu’jam maqayis al-lughah. Volume 6 (p.48). Darl Al Fiker. Jordan. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://al-maktaba.org/book/21710/2524#p1

- Ibn Fāris al-Qazwīnī, Aḥmad. (1979). Nazaha. Mu’jam maqayis al-lughah. Volume 5 (p.117). Darl Al Fiker. Jordan. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://archive.org/details/WAQ73918/73918/page/n647/mode/2up

- Mokhtar Omar, Ahmed. (2008). Harwala. Mu’jam al-lughah al-’arabīyah al-mu’āṣirah. First Edition. Volume 3 (P.2345). Alam Al Kutub. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://al-maktaba.org/book/31852/30081#p1

- Mokhtar Omar, Ahmed. (2008). Naziha.Mu’jam al-lughah al-’arabīyah al-mu’āṣirah. First Edition. Volume 3 (P.2198). Alam Al Kutub. Retrieved March, 27th 2022 from https://al-maktaba.org/book/31852/28058