ABSTRACT

Conservative estimates place the number of individuals affected by human trafficking in the sub-Saharan African region at close to nine million. While there has been growing attention paid to innovative prevalence estimation approaches, and development of evidence-based interventions in the region, literature examining how these interventions are adapted, implemented, and delivered across multiple sectors, populations, and geo-political settings remains nascent at best. This critical gap in implementation research stymies the scale-up of effective anti-trafficking approaches. The central aim of this scoping review is to contribute to the anti-trafficking knowledge base by describing the current state of implementation research in this region based on 12 identified peer-reviewed human trafficking studies in sub-Saharan Africa. While none of the retrieved studies focuses solely on the implementation of a human trafficking intervention, the studies identified and discussed the acceptability and cost impacts of their implementation efforts. We conclude that advancing trafficking knowledge and praxis would require the synergistic and concurrent pursuit of both implementation and intervention strategies.

SDG Statement

By illuminating the dearth of implementation research in the anti-trafficking field, this manuscript seeks to advance UN Sustainable Development Goals 5, 16, and 8 (specifically Target 8.7). These goals aim to eliminate violence, exploitation, and the abuse of women and children with particular focus on the eradication of crimes associated with modern slavery and human trafficking. In addition to illustrating this critical gap in the human trafficking literature we proffer a roadmap that will help the field better coordinate research that seeks to strengthen and leverage regional anti-trafficking interventions.

Introduction

This study examines the human trafficking (HT) literature about sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with the view of describing the current state of implementation research in the region. While there has been two decades of private and public investment in anti-trafficking interventions, scholars and policymakers report that the impact of such efforts remains unclear (e.g., Bryant & Landman, Citation2020; Zhang, Citation2022). The difficulty of measuring trafficking contributes to this lack of clarity, as difficulties in mapping change in prevalence over time stymies efforts to track impact (de Pérez, Citation2015; Landman, Citation2020). It is notable too that the need for rigor in designing and evaluating human trafficking interventions has only recently garnered effort (Bryant & Joudo, Citation2018; Dell et al., Citation2019; Zhang, Citation2022). Concerted multidisciplinary and multisector efforts have been made more recently to improve measurement techniques and design and evaluate interventions (Bossard, Citation2022). For instance, in 2020, the University of Georgia launched the Prevalence Reduction Innovation Forum (PRIF) coordinating multidisciplinary teams in six countries (Brazil, Costa Rica, Morocco, Pakistan, Tanzania and Tunisia), measuring various types of trafficking (Center on Human Trafficking Research & Outreach, Citationn.d.). Additionally, numerous reviews of various interventions are now available. These include reviews of exit and post-exit programs for commercially sexually exploited children and young adults (Dell et al., Citation2019), and programs by law enforcement and civil society agencies collaborating to combat human trafficking (Winrock International, Citationn.d.).

Despite the growing and much needed progress in measurement and intervention studies, there remains a lack of progress regarding the strategies needed to promote the adoption, implementation, and sustainment (referred to as implementation strategies) of evidence-based anti-trafficking interventions. Zhang (Citation2022), for instance, notes that the growing demand for rigorous evaluation designs in anti-trafficking efforts rarely comes with attention to associated cost implications to all parties involved, and Sertich, Sertich and Heemskerk (Citation2011) discuss the cost-related struggles of implementing interventions to protect trafficked individuals in Ghana. Considering that the impact of interventions emerges from the complex interplay between intervention, implementation strategy, and context (Pfadenhauer et al., Citation2017; Proctor et al., Citation2011), knowledge gaps about implementation limit replication and scale up of effective interventions that have potential for meaningful impact. Knowledge on what works is insufficient without knowledge on how best to implement and deliver these strategies (Proctor et al., Citation2011). This is particularly critical as human trafficking interventions typically occur in places and populations facing multiple social, economic, and political challenges (Rothman et al., Citation2017; Zhang, Citation2022). Many of these challenges to implementation, such as poverty, natural disasters, government corruption, civil unrest and gender inequality, overlap with the root causes of human trafficking.

Given this backdrop, this present study examines the human trafficking implementation research literature in SSA to inform future efforts in disseminating and sustaining evidence-based anti-trafficking practices. In the first section, we define implementation science. Next, we provide an overview of human trafficking in SSA and the common intervention points across the region. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018), we report scoping review findings from identified peer reviewed implementation studies, then conclude with the implications of the findings for research, practice and policy.

Implementation Science

Implementation scienceFootnote1 (Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006, p. 1) is taking as a basic assumption that interventions are ineffective unless implemented well (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Implementation research examines implementation delivery, quality gaps in implementation, contextual factors (including micro-level, agency-specific and wider social, political, and economic characteristics and challenges), and the effectiveness of implementation strategies (Brownson et al., Citation2017). The identification and management of barriers (e.g., the lack of trained staff to conduct an intervention) and facilitators of intervention success (e.g., a trusted local champion for a service novel to the community) in the implementation context (Bauer, Citation2015), for instance, is of particular interest in implementation research.

Notably, implementation outcomes are distinct from service system outcomes and intervention/treatment outcomes (E. Proctor et al., Citation2009). Implementation outcomes are the effects of implementation strategies, i.e., deliberate and purposive actions to implement new treatments, practices, and services that include planning, education, restructuring, quality management, and policy changes among others (Powell et al., Citation2012). Proctor et al. (Citation2011) synthesized implementation literature to create definitions for seven implementation outcomes: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability of interventions. Acceptability, appropriateness, cost and feasibility reflect elements or features about the fit of the interventions within the implementation context, whereas adoption, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability reflect different gradations and time points of actual intervention use. Acceptability is the “perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment, service, practice, or innovation is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory” (Proctor et al., Citation2011, p. 67). Adoption or “uptake” is “the intention, initial decision, or action to try or employ an innovation or evidence-based practice” (Proctor et al., Citation2011, p. 69). Appropriateness is the “perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the innovation or evidence-based practice for a given practice setting, provider, or consumer” (Proctor et al., Citation2011, p. 68). Cost is the cost impact of an implementation effort which depends on the complexity of the intervention and implementation strategy, and the location of service delivery (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Feasibility is “the extent to which a new treatment, or an innovation, can be successfully used or carried out within a given agency or setting” (Karsh, Citation2004 as cited in Proctor et al., Citation2011, p. 69). Fidelity is “the degree to which an intervention was implemented as it was prescribed in the original protocol or as it was intended by the program developers” (Dusenbury et al., Citation2003; Rabin et al., Citation2008 as cited in Proctor at el., Citation2011, p. 70). Penetration or reach is “the integration of a practice within a service setting and its subsystems” (Proctor et al., Citation2011, p. 70). Sustainability is “the extent to which a newly implemented treatment is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations” (Proctor et al., Citation2011, p. 70). Implementation outcomes serve as indicators of the implementation success, as proximal indicators of implementation processes, and as key intermediate outcomes (Rosen & Proctor, Citation1981).

Examining the intervention and its implementation enables practitioners and policymakers to distinguish whether an intervention failed to achieve intended outcomes because the intervention was ineffective in the new setting (intervention failure), or if the intervention was deployed incorrectly (implementation failure) (Proctor et al., Citation2011); this distinction is critical for improving translation of intervention from laboratory settings to “real world” venues (Balas & Boren, Citation2000). Annual reports, such as the Trafficking in Persons report by the U.S. Department of State, and the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons by UNODC [United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime], as well as a host of regional and local level reports continue to reveal that current efforts have yet to come close to the eradication of human trafficking or providing adequate services to survivors; implementation research could contribute to our understanding of why this is so and the way forward.

Human Trafficking in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is characterized by a variety of cross-border migration as well as domestic migration configurations (Adepoju, Citation2005). Within these movements of people, displaced, unskilled, or otherwise at-risk individuals are vulnerable to human trafficking. The Global Slavery Index (Citation2018) estimates that around 9.26 million individuals are victimized by human trafficking in Africa. Reported forms of trafficking in SSA include labor trafficking in various industries and domestic situations, sex trafficking, organ trafficking, forced begging, forced or child marriage, rituals, illegal surrogacy and trafficking of children for adoption, child soldiering, and child camel jockeys (Alabi, Citation2018; Lucio et al., Citation2020). Approximately 94% of reported trafficking involves forced labor and sexual exploitation (UNODC, Citation2018). SSA has notably high rates of child and female survivors (Okech et al., Citation2018; Umukoro, Citation2021).

SSA invests significant amounts of domestic and foreign aid for anti-trafficking interventions. Many of these activities are funded by international organizations and donor countries in the Global North (Gleason & Cockayne, Citation2018). Reported anti-trafficking efforts in SSA include enactment and enforcement of anti-trafficking laws, programs to reduce vulnerability of at-risk groups, and direct services to victims (Limoncelli, Citation2016; Woo, Citation2022). Interventions are carried out by religious and secular community groups, local and regional government bodies, and local and international nongovernmental organizations. Implementation of anti-trafficking interventions in SSA is complex as these interventions often have to be implemented in contexts characterized by poverty, gender and racial inequity, and substantial instability (e.g., armed conflict, natural and manmade disasters), and limited institutional support and accountability (e.g., lack of prosecution for criminal organizations) (UNODC, Citation2018). The nature of institutional, legal and policy frameworks regarding human trafficking in SSA also impacts the implementation of interventions. For instance, in 2016, only 23 of the countries in SSA had domestic statutory laws addressing human trafficking (Woo, Citation2022), and the absence of legal tools would stymy the implementation of interventions to prosecute human traffickers (Adepoju, Citation2005). Within delivery settings, challenges include inadequate resources, competition for resources, corruption, fraud, insensitivity toward local norms, organizational problems such as poor management practices and difficulties in collaborating with other agencies and community partners (Chima, Citation2015; Nwogu, Citation2014).

Methods

Scoping reviews are used to identify and analyze research gaps and to examine how research is being conducted on a specific topic, particularly for beginning work in a new area (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Due to the nascent nature of implementation research in anti-trafficking efforts, we sought to conduct a scoping review to answer the exploratory question of “What is the state of implementation research in human trafficking interventions in sub-Saharan Africa?” The objectives were to review peer-reviewed literature on implementation of exit and post-exit human trafficking interventions in sub-Saharan Africa to:

Identify the types of evidence-based HT interventions discussed in the literature;

Describe the barriers and facilitators in the implementation context;

Describe the implementation strategies used, and

Describe the implementation outcomes examined.

Identifying Relevant Studies

We used the PRISMA-ScR to guide our methodology and reporting (Tricco et al., Citation2018). Four social science and humanities databases were searched to obtain peer-reviewed articles published after 2000 in English from a wide variety of scholarly fields through SocINDEX, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Academic Search Complete and Social Work Abstracts. The following combinations of search terms were used: “Africa” OR “sub-Saharan Africa” AND “Anti-trafficking” or “human trafficking” or “sex trafficking” or “labor trafficking” or “slavery” or “child labor” or “child sex trafficking” or “child soldier” or “forced begging” or “organ trafficking.” The authors identified a total of 502 records. Two records were removed through duplicate removal.

Study Selection

Next, the first two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts using Covidence (Citationn.d.). After discussion and consensus, 83 records were retained. Full-text screening was performed on these records using the following inclusion criteria for peer-reviewed studies:

Implementation study of an intervention (program or service) that directly impacts human trafficking survivors, or individuals who directly impact survivors (family, community, or professionals including social service providers or educators).

Evaluation studies, critiques or review of programs and services, and study protocols were included if implementation outcomes (acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, costs, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, sustainability) or factors affecting implementation such as culture were also discussed.

Published in English between the period of 2000 and 2022.

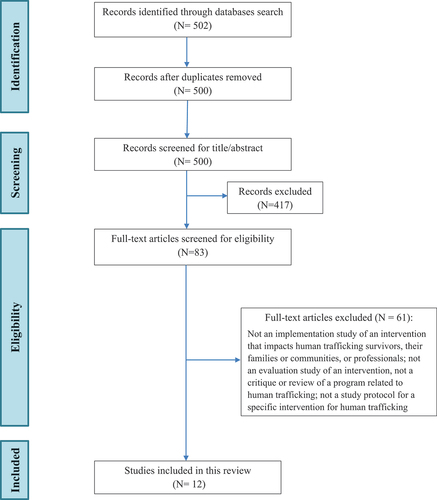

After discussion and consensus, 12 articles were retained for the scoping review. is a PRISMA chart that presents a summary of the study selection process.

Data Charting and Summarizing

Next, we “charted” information from the 12 studies using the method described by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). The first author extracted the following information: (i) Study details: study type, purpose, methodology, (ii) Intervention details: target population, trafficking industry, (iii) Implementation details: context, implementation strategies, barriers, facilitators, and (iv) Implementation outcomes (Proctor et al., Citation2011): acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability. This “descriptive-analytical” method (Pawson, Citation2002) provides a common analytical framework that captures pertinent and contextualized information on implementation across the different studies. This information was then summarized and tabulated in a spreadsheet for review (see ).

Table 1. Summary of Scoping Review Results.

Results

Study Details

Two studies described interventions with inclusion of implementation issues: Sensoy Bahar et al. (Citation2020) presented an implementation-effectiveness study protocol for an intervention program aimed at preventing adolescent girls’ unaccompanied rural-to-urban migration for child labor, and Blakemore et al. (Citation2019) presented a framework for safeguarding children from UN peacekeepers and its implementation considerations. Two studies focused on education for service professionals: Lucio et al. (Citation2020) and De Bruin Cardoso et al. (Citation2020) described and evaluated the development, implementation and effectiveness of an interprofessional college course on human trafficking, and training and support for professionals implementing reintegration programs respectively. One study, Yeboah and Daniel (Citation2021), explored the impact of rejecting indigenous knowledge on the sustainable implementation of child-focused anti-trafficking interventions. The remaining studies explored implementation issues and the intervention impact of existing direct service programs. Four studies explored the intervention impact and included discussion of matters related to implementation (Emser & Francis, Citation2017; Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010; Zibagwe et al., Citation2013), and three studies focused on identifying and describing implementation challenges faced by practitioners in direct service (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warria, Citation2018).

Overall, qualitative designs with data collected through interviews and focus groups predominated; exceptions were Sensoy Bahar et al. (Citation2020); De Bruin Cardoso et al. (Citation2020); and Lucio et al. (Citation2020) which were mixed-methods studies. Studies drew on data from seven types of respondents including parents or children (n = 4) (Hilson, Citation2010; Sensoy Bahar et al., Citation2020; Warria, Citation2018; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021); employers (n = 3) (Hilson, Citation2010; Warria, Citation2018; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021); agency staff (n = 3) (Hilson, Citation2010; Warria, Citation2018; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021); government officials (n = 3) (Hilson, Citation2010; Warria, Citation2018; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021); social workers (n = 2) (Botha & Warria, Citation2021, Citation2021); NGO personnel and other service professionals (n = 4) (Blakemore et al., Citation2019; De Bruin Cardoso et al., Citation2020; Emser & Francis, Citation2017; Hilson, Citation2008) and students who received training (n = 1) (Lucio et al., Citation2020).

Intervention Details

The majority of the interventions targeted either sex trafficking or child labor: sex trafficking involving adult female victims (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Emser & Francis, Citation2017); human trafficking involving child victims – gender not specified (Blakemore et al., Citation2019; Warria, Citation2018); child labor in cocoa farming and/or family farming (Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021; Zibagwe et al., Citation2013); small-scale mining (Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010); and unaccompanied child migration which puts children at high risk of being trafficked (Sensoy Bahar et al., Citation2020). Only two interventions (De Bruin Cardoso et al., Citation2020; Lucio et al., Citation2020), both of which focused on provider training and education, were described as effective.

Sex Trafficking Interventions

Three articles covered sex-trafficking aftercare services for victims being housed in high security shelters in South Africa (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warria, Citation2018). One intervention described a framework and its implementation plan for strengthening the safeguarding of children from sexual abuse and exploitation by peacekeeping forces in Liberia (Blakemore et al., Citation2019). Emser and Francis (Citation2017) reviewed how an under-resourced provincial government task force in South Africa, the KwaZulu-Natal human trafficking, prostitution, pornography and brothels task team, carried out the “4P model” (protection, prevention, prosecution, partnership). To reduce the risk of unaccompanied migration by adolescent girls in Ghana, a two-arm cluster randomized control trial implementation-effectiveness study was planned for the ANZANSI (resilience) family program that aimed at combining family-level economic empowerment with family group interventions on family functioning and beliefs around girls’ education, gender norms and child labor (Sensoy Bahar et al., Citation2020). De Bruin Cardoso et al. (Citation2020) conducted a study on the impact of a facilitated learning program on the uptake and effective use of different tools and approaches by practitioners for monitoring of reintegration of sexually exploited children.

Child Labor Interventions

Child labor interventions generally focused on increasing school attendance and decreasing child labor by financial support and by promoting the importance of education. For instance, Operation Sunlight focused on enabling 150 children to stop mining by providing school fees and promoting education to parents (Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010), and the ANZANSI program provided girls a savings-matching program that could be used for school fees or to start a business (Sensoy Bahar et al., Citation2020), in conjunction with family level programming to promote girls’ participation in education and business. Zibagwe et al. (Citation2013) reviewed the social protection program, Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP), which attempted to improve school attendance during the post-harvest period of April to September when food insecurity is the highest by providing food or cash for work.

Implementation Details

Interventions were implemented in South Africa (n = 4), Ghana (n = 4), Ethiopia (n = 1), and Liberia (n = 1). Two were described as being implemented in “sub-Sahara Africa” or as having recipients in “countries in Africa.” All interventions were described as being implemented and largely funded by government agencies, nonprofit or international nongovernmental organizations partnering with local agencies. Child exploitation or labor interventions were implemented in rural communities with low-income families involved in farming or mining, or at risk of unaccompanied migration (Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010; Sensoy Bahar et al., Citation2020; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021; Zibagwe et al., Citation2013). Agency or institutional settings for intervention delivery included long-term residential facilities for sex trafficking victims (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warria, Citation2018), a law enforcement agency (Emser & Francis, Citation2017), an interagency anti-trafficking collaboration for provider training and support (De Bruin Cardoso et al., Citation2020); and a university (Lucio et al., Citation2020).

Barriers

Several barriers to intervention implementation were described in the studies. These could be categorized into two broad groups: (1) barriers related to the differences between implementers’ priorities and worldviews with those of the intervention recipients, and (2) barriers related to low resource environments. Notably, the majority of the studies (n = 9) described anti-trafficking organizations or service providers as failing to enact implementation strategies to overcome either type of barrier, contributing to the failure of most interventions.

Differences in Priorities and Worldviews

Adoption of interventions seemed driven mostly by the funding priorities of international organizations or international foundations, with local sensibilities and indigenous knowledge rarely having influence on such decisions (e.g., Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021). For instance, Yeboah and Daniel (Citation2021) reported that Ghanian parents saw children’s work on the family farm or cocoa farms as essential preparation for their futures and a sign of maturity and responsibility, whereas global policy constructions of childhood underlying the interventions by nongovernmental organizations such as the International Labor Organization framed such labor as detrimental to children’s development and futures. Hilson (Citation2008, Citation2010) noted that failure to analyze and understand complex local realities around issues such as poverty and child labor contributed to the implementation of interventions that were unhelpful and potentially furthered poverty and child labor. More specifically, anti-child labor interventionists prioritized children’s school attendance while local communities and parents viewed children’s labor as necessary to sustain their family (e.g., Hilson, Citation2008). Notably, these interventions did not also target the quality of local schools or availability of jobs for school completers (e.g., Hilson, Citation2008). The mismatch between the way childhood is viewed by outside interventionists and local communities led to pertinent differences between the implementors and recipients regarding the acceptability and appropriateness of the interventions: implementers found the interventions acceptable and appropriate, but the recipients did not. Hilson (Citation2008, Citation2010), and Yeboah and Daniel (Citation2021) also found that some implementors “rejected local realities” (Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021, p. 181) and had judgmental or hostile attitudes toward parents for finding the interventions unacceptable and inappropriate, rather than strategizing how the intervention or its implementation might be changed to improve outcomes.

For sex trafficking interventions, there were clear distinctions between what service providers and clients saw as necessary and helpful. For instance, while the shelter and government anti-trafficking policy prioritized isolating women from alleged traffickers and situations of high-risk, women prioritized being able to earn an income, whether for themselves or for remittance to their families (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warria, Citation2018). The restrictive safety policies in the sex trafficking shelters that curtailed clients’ individual freedoms, e.g., not being permitted to own a cell phone, alongside clients not being able to work when at the shelters, especially in the absence of financial aid and other social services, created an environment where clients would leave the shelters as soon as possible, cutting short opportunities to receive care (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warria, Citation2018).

Lack of Resources in the Environment

The lack of material resources in the external environment posed contextual barriers to successful implementation. For instance, the poor quality or distance of local schools and lack of jobs for educated individuals contributed to parents’ reluctance to place their children in schools in lieu of labor. These problems contributed to parents deciding that school would not ensure the best possible future for their children and prioritizing children’s labor which was indeed urgently needed to sustain their families (Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021). Zibagwe et al. (Citation2013), who reviewed the Ethiopian government’s food or cash for work exchange program (the PSNP) reported on an implementation issue the time of the year PSNP was implemented. The intervention was implemented during the post-harvest period of April to September when food supply is low – which negatively affected rather than improved children’s school attendance and increased child labor. This was due to families supplementing adult labor with child labor, and the lack of physical assets that could reduce child labor, such as easy access to water and fuel sources.

In anti-trafficking service or law enforcement interventions aimed at adult victims, lack of adequately trained staff also contributed to implementation difficulties, and the lack of access to health care and therapeutic services for victims in their care (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Emser & Francis, Citation2017; Warria, Citation2018). In South Africa, there is only one shelter in the country that provides services to male victims of trafficking (Emser & Francis, Citation2017).

The lack of structural resources also hinders implementation. For instance, Emser and Francis (Citation2017), in their focus on a law enforcement intervention, reported on how the lack of operational anti-trafficking legislation and policy that only partially criminalized trafficking negatively affected counter-trafficking governance in South Africa. The lack of coordinating bodies or mechanisms for provincial and other local-level anti-trafficking efforts also creates operational and institutional challenges for law enforcement (Emser & Francis, Citation2017).

Implementation Strategies

Only three studies described implementation strategies that targeted specific barriers. Sensoy Bahar et al. (Citation2020) described an intervention for reducing labor migration risk for adolescent girls in Ghana which involved not only financial incentives that would benefit the entire family but also programs with the family to address misconceptions about gender, education and labor to improve acceptability and thus participation. De Bruin Cardoso et al. (Citation2020) described the creation of a learning network where members could pilot preferred tools from the RISE Monitoring and Evaluation of Reintegration Toolkit (Cody, Citation2013). The learning networks were intended to promote the feasibility of their partner agencies’ attempts to effect and monitor the reintegration of trafficked children and included topic-focused webinars, online meetings and peer-to-peer learning sessions. Lucio et al. (Citation2020) described using constant collaboration and consultation with a faith-based organization and a key informant at their university to improve the acceptability and appropriateness of an interprofessional human trafficking course for Catholic sisters. This collaboration was used to provide insights into Catholic doctrine, local culture, and perspectives of human trafficking. Additionally, they used dialogue with the university upper-level administration and changing project leadership where necessary to address acceptability of their course within the university structure.

Facilitators

Overall, the majority of the interventions discussed in the studies did not include strategies for addressing cultural or resource-related barriers. However, the articles identified external collaborations with larger international agencies including the International Labor Organization and the United Nations (e.g., Blakemore et al., Citation2019) and international foundations like the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation (Lucio et al., Citation2020) as being fundamental to funding and training for implementing the interventions.

Implementation Outcomes

In terms of seven implementation outcomes, overall the studies were most explicit about acceptability and costs (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Only one study, Sensoy Bahar et al. (Citation2020), included a measurable strategy for assessing implementation outcomes. Her team focused on two outcomes: feasibility as measured by enrollment rates of 70% and higher, and acceptability as assessed by the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (csqscales.com).

Acceptability

Three studies included implementation strategies to promote acceptability: De Bruin Cardoso et al. (Citation2020), Lucio et al. (Citation2020), and Sensoy Bahar et al. (Citation2020) (see Implementation Strategies subsection for a description). Most (n = 9) of the studies, however, described the interventions as unacceptable to their target populations, with the interventionists having no implementation strategies to address unacceptability. For example, the long length of stay at a shelter for sex trafficking survivors where they could not work or earn any money, due to long waits for court dates, was described as rendering services unacceptable, but the service providers were unable to change these conditions (Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Warria, Citation2018). For child labor directed interventions that promote schooling in place of children’s work, unacceptability was generated by a frank mismatch between families’ needs and the support offered by these interventions. Yeboah and Daniel (Citation2021), Zibagwe et al. (Citation2013) and Hilson (Citation2008, Citation2010) all reported that children, parents and employers shared that children’s labor was still needed to sustain their families despite food, cash or other forms of support given, and that the monies given to school fees still left families struggling to cover other costs incidental to school attendance, such as books and uniforms.

Cost

Implementation costs were described by eight studies as having a negative impact on other implementation outcomes and intervention effectiveness; implementors in these studies did not have strategies for addressing cost. Despite the support of foreign organizations who worked with local partners, costs negatively impacted several implementation outcomes such as feasibility, fidelity, penetration and sustainability (e.g., Emser & Francis, Citation2017). For instance, while long-term aftercare was seen as necessary for survivors of sex trafficking, such services cost too much (e.g., Botha & Warria, Citation2020) and social protection programs that provided nonconditional food or food/cash for work were not able to provide enough food for their recipients (e.g., Zibagwe et al., Citation2013). Hilson (Citation2008; Hilson, Citation2010) reported that Operation Sunlight was not carried out as planned (poor fidelity) – schools that recipients attended did not receive the promised school fees due to the program being under-funded, and local officials expressed concerns about the sustainability upon the end of funding by international organizations. The feasibility of having a task force to address sex trafficking and shelter services was affected by costs, as agencies were not able to provide the full extent of necessary resources and training to staff (e.g., Emser & Francis, Citation2017). Material and time costs also limited the adoption and penetration of successful human trafficking interventions (e.g., Emser & Francis, Citation2017; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021).

Discussion

In exploring the question “What is the state of implementation research in human trafficking interventions in sub-Saharan Africa?,” we identified 12 articles reporting on implementation. Only a few types of trafficking were addressed in the retrieved articles despite a search strategy designed to retrieve intervention efforts for a wide range of trafficking activities in SSA, and only three of the twelve described implementation strategies to address barriers and improve implementation outcomes for specific interventions, suggesting that implementation research in human trafficking in this region is still in a very early stage.

Overall, the reviewed studies generated more robust information about barriers (to acceptability and costs) than details about how acceptability and costs were addressed by the implementation strategies. Nonetheless, insights from the authors who highlighted how local perspectives on poverty, gender norms, child labor, and family expectations differ from the perspectives of implementers suggest that this distinction be first addressed as a fundamental step toward improving service implementation. This is critical because, as demonstrated by these authors, such differences not only diminish both the effectiveness and acceptability of the interventions to the clients but also cause social and material harm. For instance, unsuccessful child labor reduction programs not only create the loss of children’s income with little chance of the child gaining an education in a context where that education would provide access to livable wage employment (e.g., Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010) but also diminish children’s status or roles in the family, as children’s contributions to their family through work is viewed as a sign of maturity and responsibility (e.g., Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021).

For shelter-based services, distinctions between what service providers consider as necessary “safety” and “security” measures and what clients consider as such also need to be addressed (e.g., Botha & Warria, Citation2020). Again, these differences led to intervention failure and mistrust between client and providers, such as increased stigmatization, loss of income, mistrust of service providers, and risk of abuse by law enforcement personnel. Similarly, the authors who highlighted how insensitivity to the local context of implementation, such as the lack of decent schools (e.g., Hilson, Citation2008) and the farming cycle combined with lack of child labor-saving assets (e.g., Zibagwe et al., Citation2013), either failed to decrease child labor or inadvertently increased child labor, suggest that pre-implementation studies that assess for local and cultural factors is an essential first step. Engaging survivors in intervention and implementation design is essential for improving the fit between interventions and implementation strategies and the local context. Sensoy Bahar et al. (Citation2020) exemplified this practice by addressing both cultural and contextual factors in their study protocol, which involved gathering community stakeholders to be involved in adapting their intervention to the target community, training facilitators from the local community to deliver the intervention, and conducting ongoing process evaluation to assess satisfaction, obstacles to program, and barriers/motivators to participation. Their study may provide a feasible, participatory model for the simultaneous study of implementation and intervention effectiveness in a low resource rural community.

The implementation challenges and the lack of strategies to address these challenges expose a knowledge gap and a ripe opportunity to expand implementation research into human trafficking. For instance, research could be done regarding characteristics of recipients and deliverers, relationships with other bodies, influence of funding, competitive pressure to implement an intervention and their readiness for change and other pertinent factors with the view of uncovering currently overlooked resources or re-strategizing implementation to reduce costs with attendant effect on other implementation outcomes (Damschroder et al., Citation2022). This knowledge could also shed light on why particular agencies are behaving the way they do in their implementation efforts, and how change for the better could be explored. In addition to the agency-specific frameworks that affect implementation, it would be of vital importance to study legal and state-wide policy strategies for promoting implementation since the institutional and political context were critical contextual influences in the studies included in this review. Emser and Francis’ study (Citation2017) of the KwaZulu-Natal intersectoral task team, for instance, stated that the partial criminalization of human trafficking in South Africa and lack of interagency coordination mechanisms at the national level hindered the ability of provincial anti-trafficking task teams to obtain funding for, and formalize coordinating responses between key actors at provincial and local levels, creating delays in responses to suspected cases of human trafficking and victim services. They suggest a national policy framework that enables the operationalization of comprehensive anti-trafficking legislation; Implementation research could examine comparatively across different SSA countries the impact of similar and disparate frameworks on anti-trafficking interventions by state bodies and their partners. Since implementation strategies that target systems and policies have received limited empirical attention despite their importance in limited resource environments, this line of research has potential to advance both implementation science and new knowledge on addressing human trafficking (Lovero et al., Citation2023).

The studies indicated that conflicts between provider and client priorities and lack of material resources and structural support are major barriers to implementation. While no specific strategies were explored in their studies for addressing these issues, the articles on child labor (e.g., Hilson, Citation2008; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021) highlight the importance of valuing indigenous knowledge and context, and incorporating these into frameworks for child protection and other anti-trafficking efforts, rather than imposing Western notions of what constitutes “a good childhood” and other norms on local communities. They also recommended that parents be involved in creating, monitoring, and sustaining child protection that integrated meaningful aspects of indigenous knowledge, ideals and global policy frameworks in contextually appropriate ways (Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021). These results point to the importance of participatory approaches that share power and decision-making for designing studies of interventions and implementation strategies so that definitions of “successful implementation” and “successful intervention” incorporate local knowledge and are meaningful locally (Nápoles & Stewart, Citation2018).

Notably, none of the articles mentioned grassroots level or community-initiated groups as being the implementers; only one article (Sensoy Bahar et al., Citation2020) mentioned community stakeholders as having a part in adapting an intervention for local implementation. In other words, survivors of human trafficking themselves, and/or communities at risk of human trafficking, have been rarely involved in intervention or implementation efforts in SSA despite their knowledge of trafficking, personal and community needs and resources, and local systems. This oversight and violation of survivors’ rights is not unique to SSA. Academics and activists have made slow progress to acknowledge survivors as equitable producers of trafficking-related knowledge (Gerassi & Nichols, Citation2018; Knight et al., Citation2023; Twis & Praetorius, Citation2021). Strategies that leverage existing community perspectives, strengths and resources, rather than those that require sustained input from foreign aid organizations or currently inefficient government aid mechanisms, may be a priority as a next step for the implementation of HT interventions. This is particularly critical as many of the root causes of trafficking, e.g., poverty and gender inequality, affect the implementation of trafficking interventions. The problems faced in implementing sex trafficking and child labor interventions due to the lack of resources foreground how important the material and structural support is to implementation success. The lack of community-created and community-resourced interventions, in addition to the conflict between global policy and local norms, perpetuates conditions of inequity both socially and materially for those that HT interventions aim to “help”. As evidenced by the majority of the papers reviewed here (e.g., Botha & Warria, Citation2020, Citation2021; Emser & Francis, Citation2017; Hilson, Citation2008, Citation2010; Warria, Citation2018; Yeboah & Daniel, Citation2021), these interventions did not increase or sustain school attendance, child food insecurity, the safety of women trafficking victims or their ability to access services or resources that would equip them for financial viability and improved mental or physical health. These interventions also appeared to have unintended negative consequences including stigmatizing local parents and women who have been trafficked, and introducing values and social roles to children that are at odds with their family and cultural norms. A socially just, inclusive and equitable approach is necessary for the framing and formulation of interventions that promote social justice and survivors’ rights, and which avoid the subtle replications of structural or state violence (McNulty et al., Citation2019). To address the barriers identified in the studies in this review, successful implementation of HT interventions likely depends on strategies that disrupt, manipulate, or alter the status quo in systems and policies. Therefore, it is not only ethical but also morally imperative for the HT research community to study the impact of implementation strategies on individuals and the local socio-cultural ecology. Engaging survivors equitably in this work will be critical for understanding institutional and legal contexts, and reaching more survivors in effective interventions.

Shelton et al. (Citation2021) provide three recommendations addressing structural racism in public health research that could be adapted for progressing socially just implementation research and practice in anti-HT efforts in SSA: (1) include structural racism and other structural or power disparities into the implementation science frameworks, models, and related measures, (2) use a multi-level approach for selecting, developing, adapting, and implementing evidence-based and implementation strategies to increase equity between all stakeholders and integrate indigenous and contextual knowledge, and (3) apply transdisciplinary, community-engaged and intersectoral collaborations and engagement as essential components of implementation (Knight & Kagotho, Citation2023). Few implementation studies have been conducted in the Global South. A recent review of research on implementation outcomes only had 40 implementation studies conducted in African countries, i.e., 10% of the studies identified (E. K. Proctor et al., Citation2023). This indeed indicates strongly the need for anti-racist paradigms to inform implementation research priorities.

Finally, many scholars have examined the issues of language, power, gender, race, and nationality in the constructions of human trafficking that currently informs policy and practice (e.g., Bernstein, Citation2018; authors). Typically, such scholarship explicates failure of anti-trafficking efforts in identifying various disparities and biases involved in the globally normative construction of HT propagated by international bodies, and the harms easily caused by such constructions, such as the justification of “human trafficking” policies that essentially criminalize migration (e.g., Kaye, Citation2017; Knight & Kagotho, Citation2022). Embracing implementation science will enable a concrete look at how the concerns raised in the critical literature affect the unfolding of interventions in local contexts. It could tie together the praxis-oriented scholarship that focuses on tangible program designs and outcomes, and the critical scholarship that focuses on the potential harms of the discourses and paradigms informing the construction of HT and the attendant interventions.

Future Research Directions

This review has highlighted a sizable gap in implementation science in anti-trafficking efforts in SSA requiring a robust program of research to address. First, basic studies that examine implementation outcomes of existing interventions are needed to identify implementation gaps and establish research priorities. Second, real-world observational studies examining the relationship and impact of the contextual barriers and challenges (including personnel-, agency-, community-, and state policy-based contexts), on implementation outcomes can inform the development of salient implementation strategies. Third, rigorous pragmatic studies examining the mechanisms of action and effectiveness of strategies for implementing HT interventions are necessary for informing future scale-up. It bears repeated emphasis that survivors and vulnerable communities themselves must be deeply engaged with meaningful roles in all these research efforts. Community-engaged, participatory research where survivors and their communities take equitable roles in research and its application acts as a bulwark against the replication of structural inequality, and promotes the likelihood that the knowledge truly emerges and attends to local preferences, sensibilities and challenges (Hounmenou, Citation2020; Kaye, Citation2017). Engaging survivors in future intervention and implementation studies is important for understanding the institutional and legal contexts, and reaching more survivors. Although implementation has been traditionally considered after intervention development and testing, methods that synergize intervention and implementation could accelerate this process (Gitlin & Czaja, Citation2015). Studies that “design for dissemination” consider upfront the challenges and complexities in the practice settings where the intervention will reside (Gitlin & Czaja, Citation2015) to design the intervention in ways that would facilitate implementation and scalability (for examples drawn from the behavioral health literature in SSA, see Kumar et al., Citation2020; Mellins et al., Citation2014; Musanje et al., Citation2023). Intervention optimization approaches like the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) inform the development, optimization, and evaluation of multi-component interventions that balance intervention effectiveness with acceptability, scalability, and efficiency (Collins, Citation2018; Guastaferro & Collins, Citation2021). Hybrid effectiveness-implementation studies enable investigators to assess the effects of both intervention and implementation strategy in context (Curran et al., Citation2012), such as in Sensoy Bahar et al.’s (Citation2020) study protocol for the ANZANSI program. Hybrid approaches that comprehensively explicate the issues that matter to recipients and front-line workers have tremendous potential to map the linkages between interventions, and survivor and community outcomes, while identifying resource misuse and untapped local resources. Furthermore, since implementation challenges overlap with the root causes of human trafficking, such as gender inequity, that are often the target of interventions, hybrid effectiveness-implementation studies would clarify the particular interplays between intervention, implementation strategy, and context for specific localities in situations in SSA, leading to more precise adaptations and strategies for intervention and implementation.

Limitations

The results of this review should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. First, only studies published in English were included. While there exist a significant number of English-language periodicals which enjoy wide distribution in SSA, French and Arabic are also prominent languages of science in the region. Only studies published after the Palermo Protocol was established were reviewed; a cutoff determined to account for significant global and local policy and resource investments in anti-trafficking interventions. Finally, while we restricted our search to peer-reviewed literature, we acknowledge that our central question could very well be addressed in non-scholarly publications including evaluation briefs and organizational reports.

Conclusion

The complex nature of HT which presents as interconnected exploitation across multiple industries is a prime area for implementation science to create the knowledge needed to translate intervention findings across contexts and industries for a multiplier effect. The status of implementation studies of HT interventions in sub-Saharan Africa is in its nascent stage. Using the PRISMA-ScR method, we identified 12 articles reporting on implementation of human trafficking interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the interventions targeted sex trafficking or child labor. While several barriers to intervention implementation were described, only three of the twelve described implementation strategies to address these barriers and improve implementation outcomes. In terms of seven implementation outcomes, these studies were most explicit about acceptability and cost outcomes. Synergizing intervention and implementation research has the potential to advance human trafficking research and praxis by enabling interventions to be more quickly applied successfully and adopted sustainably by individuals, communities and organizations. Going forward, it is imperative that HT intervention research in SSA involves implementation research, particularly on ways to increase acceptability through the incorporation of local knowledge, appropriateness through an assessment of local situations, lower costs and efficient use of community and international resources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other EBPs (Evidence-based practice) into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services.

References

- Adepoju, A. (2005). Review of research and data on human trafficking in sub-saharan Africa. International Migration, 43(1–2), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-7985.2005.00313.x

- Alabi, O. J. (2018). Socioeconomic dynamism and the growth of baby factories in Nigeria. SAGE Open, 8(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018779115

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Balas, E. A., & Boren, S. A. (2000). Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 9(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1637943

- Bernstein, E. (2018). Brokered subjects: Sex, trafficking, and the politics of freedom. University of Chicago Press.

- Blakemore, S., Freedman, R., & Lemay-Hébert, N. (2019). Child safeguarding in a peacekeeping context: Lessons from Liberia. Development in Practice, 29(6), 735–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1614148

- Bossard, J. (2022). The field of human trafficking: Expanding on the present state of research. Journal of Human Trafficking, 8(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2021.2019527

- Botha, R., & Warria, A. (2020). Social Service provision to adult victims of trafficking at shelters in South Africa. Practice, 32(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2019.1567702

- Botha, R., & Warria, A. (2021). Challenges of social workers providing social services to adult victims of human trafficking in select shelters in South Africa. Social Work, 57(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.15270/57-1-906

- Brownson, R. C., Colditz, G. A., & Proctor, E. K. (Eds.). (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. Oxford University Press.

- Bryant, K., & Joudo, B. (2018). What works? A review of interventions to combat modern day slavery. Retrieved from https://www.walkfreefoundation.org/news/resource/works-review-interventions-combat-modern-day-slavery/

- Bryant, K., & Landman, T. (2020). Combatting human trafficking since Palermo: What do we know about what works? Journal of Human Trafficking, 6(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2020.1690097

- Center on Human Trafficking Research & Outreach. (n.d.). Prevalence reduction innovation forum. https://cenhtro.uga.edu/prif/about_prif/

- Chima, S. C. (2015). Religion politics and ethics: Moral and ethical dilemmas facing faith-based organizations and Africa in the 21st century-implications for Nigeria in a season of anomie. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(7), S1–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.170832

- Cody, C. (2013). RISE monitoring and evaluation of reintegration toolkit. UHI Centre for Rural Childhood.

- Collins, L. M. (2018). Optimization of behavioral, biobehavioral, and biomedical interventions: The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST). Springer. Covidence (n.d.). https://www.covidence.org/

- Covidence. (n.d.). Covidence. https://www.covidence.org/

- Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M., & Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

- Damschroder, L., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O., & Lowery, J. C. (2022). The updated consolidated framework for implementation research: CFIR 2.0.

- De Bruin Cardoso, I., Bhattacharjee, L., Cody, C., Wakia, J., Tachie Menson, J., & Tabbia, M. (2020). Promoting learning on reintegration of children into family-based care: Implications for monitoring approaches and tools. Experiences from the RISE learning network. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 15(2), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2019.1672910

- Dell, N. A., Maynard, B. R., Born, K. R., Wagner, E., Atkins, B., & House, W. (2019). Helping survivors of human trafficking: A systematic review of exit and postexit interventions. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 20(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017692553

- de Pérez, J. L. (2015). Examining trafficking statistics regarding Brazilian victims in Spain and Portugal. Crime, Law and Social Change, 63(3–4), 159–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-015-9562-x

- Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., & Hansen, W. B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice, 18(2), 237–256.

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. ImplementationSci, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Emser, M., & Francis, S. (2017). Counter-trafficking governance in South Africa: An analysis of the role of the KwaZulu-natal human trafficking, prostitution, pornography and brothels task team. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 35(2), 190–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2017.1309363

- Gerassi, L. B., & Nichols, A. (2018). Heterogeneous perspectives in coalitions and community-based responses to sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Implications for practice. Journal of Social Service Research, 44(1), 63–77. 10.1080/01488376.2017.1401028

- Gitlin, L. N., & Czaja, S. J. (2015). Behavioral intervention research: Designing, evaluating, and implementing. Springer.

- Gleason, K., & Cockayne, J. (2018). Official development assistance and SDG target 8.7: Measuring aid to address forced labor, modern slavery, human trafficking and child labor. United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, September 15. Retrieved September 15, 2019, from http://collections.unu.edu

- Global Slavery Index. (2018). Global Slavery Index 2018. https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/ resources/downloads/

- Guastaferro, K., & Collins, L. M. (2021). Optimization methods and implementation science: An opportunity for behavioral and biobehavioral interventions. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 26334895211054363. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211054363

- Hilson, G. (2008). ‘A load too heavy’: Critical reflections on the child labor problem in Africa’s small-scale mining sector. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(11), 1233–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.03.008

- Hilson, G. (2010). Child labour in African artisanal mining communities: Experiences from Northern Ghana. Development and Change, 41(3), 445–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01646.x

- Hounmenou, C. (2020). Engaging anti-human trafficking stakeholders in the research process. Journal of Human Trafficking, 6(1), 30–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2018.1512284

- Karsh, B. T. (2004). Beyond usability: Designing effective technology implementation systems to promote patient safety. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 13, 388–394.

- Kaye, J. (2017). Responding to human trafficking: Dispossession, colonial violence, and resistance among indigenous and racialized women. University of Toronto Press.

- Knight, L., & Kagotho, N. (2022). On earth and as it is in heaven—there is no sex trafficking in heaven: A qualitative study bringing Christian church leaders’ anti-trafficking viewpoints to trafficking discourse. Religions, 13(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010065

- Knight, L., & Kagotho, N. (2023). A scoping review of faith-based responses to human trafficking in Sub-Sahara Africa. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work, 42(3), 370–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2023.2206803

- Knight, L., Ploss, A., Benavides, J., & Yoon, S. (2023). A qualitative study of risk and protective factors for resilience in survivors of sex trafficking. Violence Against Women. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012231192587

- Kumar, M., Huang, K. Y., Othieno, C., Wamalwa, D., Hoagwood, K., Unutzer, J., Saxena, S., Petersen, I., Njuguna, S., Amugune, B., & Gachuno, O. (2020). Implementing combined WHO mhGAP and adapted group interpersonal psychotherapy to address depression and mental health needs of pregnant adolescents in Kenyan primary health care settings (INSPIRE): A study protocol for pilot feasibility trial of the integrated intervention in LMIC settings. Pilot Feasibility Studies, 6(136). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-020-00652-8

- Landman, T. (2020). Measuring modern slavery: Law, human rights, and new forms of data. Human Rights Quarterly, 42(2), 303–331. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2020.0019

- Limoncelli, S. A. (2016). What in the world are anti-trafficking NGOs doing? Findings from a global study. Journal of Human Trafficking, 2(4), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2015.1135605

- Lovero, K. L., Kemp, C. G., Wagenaar, B. H., Giusto, A., Greene, M. C., Powell, B. J., & Proctor, E. K. (2023). Application of the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) compilation of strategies to health intervention implementation in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 18(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01310-2

- Lucio, R., Rapp McCall, L., & Campion, P. (2020). The creation of a human trafficking course: Interprofessional collaboration from development to delivery. Advances in Social Work, 20(2), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.18060/23679

- McNulty, M., Smith, J. D., Villamar, J., Burnett-Zeigler, I., Vermeer, W., Benbow, N., Gallo, C., Wilensky, U., Hjorth, A., Mustanski, B., & Schneider, J. (2019). Implementation research methodologies for achieving scientific equity and health equity. Ethnicity & Disease, 29(Supplement 1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.29.S1.83

- Mellins, C. A., Nestadt, D., Bhana, A., Petersen, I., Abrams, E. J., Alicea, S., Holst, H., Myeza, N., John, S., Small, L., & McKay, M. (2014). Adapting evidence-based interventions to meet the needs of adolescents growing up with HIV in South Africa: The VUKA case example. Global Social Welfare, 1(3), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-014-0023-8

- Musanje, K., Camlin, C. S., Kamya, M. R., Vanderplasschen, W., Louise Sinclair, D., Getahun, M., Kirabo, H., Nangendo, J., Kiweewa, J., White, R. G., & Kasujja, R. (2023). Culturally adapting a mindfulness and acceptance-based intervention to support the mental health of adolescents on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(3), e0001605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001605

- Nápoles, A. M., & Stewart, A. L. (2018). Transcreation: An implementation science framework for community-engaged behavioral interventions to reduce health disparities. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3521-z

- Nwogu, V. I. (2014). Anti-trafficking interventions in Nigeria and the principal-agent aid model. Anti-Trafficking Review, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121433

- Okech, D., Choi, Y. J., Elkins, J., & Burns, A. C. (2018). Seventeen years of human trafficking research in social work: A review of the literature. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(2), 102–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1415177

- Pawson, R. (2002). Evidence-based policy: In search of a method. Evaluation, 8, 157–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358902002008002512

- Pfadenhauer, L. M., Gerhardus, A., Mozygemba, K., Lysdahl, K. B., Booth, A., Hofmann, B., Wahlster, P., Polus, S., Burns, J., Brereton, L., & Rehfuess, E. (2017). Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: The context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–17.

- Powell, B. J., McMillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Carpenter, C. R., Griffey, R. T., Bunger, A. C., Glass, J. E., & York, J. L. (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Review, 69(2), 123–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558711430690

- Proctor, E. K., Bunger, A. C., Lengnick-Hall, R., Gerke, D. R., Martin, J. K., Phillips, R. J., & Swanson, J. C. (2023). Ten Years of implementation outcomes research: A scoping review. Implementation Science, 18(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01286-z

- Proctor, E., Landsverk, J., Aarons, G., Chambers, D., Glisson, C., & Mittman, B. (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 65–76.

- Rabin, B. A., Brownson, R. C., Haire-Joshu, D., Kreuter, M. W., & Weaver, N. L. (2008). A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 14(2), 117–123.

- Rosen, A., & Proctor, E. K. (1981). Distinctions between treatment outcomes and their implications for treatment evaluation. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 49(3), 418.

- Rothman, E. F., Stoklosa, H., Baldwin, S. B., Chisolm-Straker, S., Kato Price, R., Atkinson, H. G., & HEAL Trafficking. (2017). Public health research priorities to address US human trafficking. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 1045–1047. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303858

- Sensoy Bahar, O., Ssewamala, F. M., Ibrahim, A., Boateng, A., Nabunya, P., Neilands, T. B., Asampong, E., & McKay, M. M. (2020). Anzansi family program: a study protocol for a combination intervention addressing developmental and health outcomes for adolescent girls at risk of unaccompanied migration. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 6(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-020-00737-4

- Sertich, M., & Heemskerk, M. (2011). Ghana’s human trafficking act: Successes and shortcomings in six years of implementation. Human Rights Brief, 19(1), 2–7.

- Shelton, R. C., Adsul, P., & Oh, A. (2021). Recommendations for addressing structural racism in implementation science: A call to the field. Ethnicity & Disease, 31(Supplement 1,), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.31.S1.357

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Twis, M., & Praetorius, R. (2021). A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis of evangelical christian sex trafficking narratives. Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 40(2), 189–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2020.1871153

- Umukoro, N. (2021). Human trafficking in Africa: Strategies for combatting the menace. In A. D. Hoffman & S. O. Abidde (Eds.), Human trafficking in Africa (pp. 73–86). Springer.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2018). Global report on trafficking in persons 2018. Author.

- Warria, A. (2018). Challenges in assistance provision to child victims of transnational trafficking in South Africa. European Journal of Social Work, 21(5), 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1320534

- Winrock International. (n.d.) Spanning borders to counter human trafficking in Asia. https://winrock.org/project/ctip-asia/

- Woo, B. D. (2022). The impacts of gender-related factors on the adoption of anti-human trafficking laws in sub-saharan african countries. SAGE Open, 12(2), 21582440221096128. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221096128

- Yeboah, S. A., & Daniel, M. (2021). Towards a sustainable NGO intervention on child protection: Taking indigenous knowledge seriously. Development in Practice, 31(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1832045

- Zhang, S. X. (2022). Progress and challenges in human trafficking research: Two decades after the palermo protocol. Journal of Human Trafficking, 8(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2021.2019528

- Zibagwe, S., Nduna, T., & Dafuleya, G. (2013). Are social protection programmes child-sensitive? Development Southern Africa, 30(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.756100