ABSTRACT

Despite literature critically examining trafficking representations, few studies have investigated visual representations of trafficking, or done so with reference to the national policy context wherein they are being utilized. This article explores visuals associated with trafficking in Italy with a focus on digital imagery retrieved via Google. The findings show that more “international” understandings of trafficking coexist alongside national conceptualizations, expressed through representations which conflate irregular migration, smuggling and trafficking. These representations convey national anxieties, that are reflected in policy and practice. The article discusses how visuals can help construct trafficking within a given society as well as raises questions and makes tentative suggestions about their interaction with policy-making. Given the critical lens adopted throughout the paper – including crucially as concerns raced and gendered representations – and its critique of images which are produced and circulated in the online space, this article supports progress toward UN SDG 5- Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment and 12- Responsible Production and Consumption.

Seeing has, in our culture, become synonymous with understanding. We “look” at a problem. We “see” the point. We adopt “a viewpoint.” We “focus” on an issue. We “see things in a perspective.” The world as we see it, rather than “as we know it,” and certainly not as “we hear it” or “as we feel it,” has become the measure for what “is real” and “true.” (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021, p. 159)

The “visual” is a distinctive feature of today’s world. Government agencies, NGOs and corporate actors all employ visuals to promote their work, engage the public and pursue their agendas. At the start of 2023, a world-renowned organization active in the humanitarian field, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Norway, released a YouTube video publicly calling into question its own visual marketing strategies.Footnote1 As any other NGO working toward a social or humanitarian cause, over the years MSF has employed myriad photographs for promotional, awareness-raising and fundraising purposes. The dominant narrative underlying these visuals has been that of a White, Western doctor helping a Black person, preferably a child. Yet, this representation, as the speakers in the video concede, “propagates a single narrative” and “perpetuates racist stereotypes of so-called White saviors and powerless victims.”Footnote2 Taking a few images as examples, the video zooms out to reveal the cropped-out details of several photographs, the missing context, the silences that have likely led viewers to form a narrow understanding of MSF’s humanitarian work and the circumstances in which it operates.

The risk of producing and circulating biased representations of social phenomena is by no means exclusive to the humanitarian field. Critical trafficking literature is rife with examples of trafficking representations which embrace neo-colonial and White saviorist approaches. Various scholars have debunked anti-trafficking campaigns run by governmental and non-governmental actors decrying their racialized and gendered undertones, victim and perpetrator constructions, and lamentable silences about the role of the State in fueling exploitation (Cojocaru, Citation2016; O’Brien, Citation2016, Citation2019). Particular attention has been devoted to women’s bodies in trafficking imagery, frequently portrayed as dismembered, wounded and objectified by the male gaze (Andrijasevic, Citation2007; Bischoff et al., Citation2010). Academic inquiry has also spoken to the misguided conflations between trafficking, migration and sex work (Bernstein, Citation2018; Mai, Citation2012, Citation2016; McGarry & FitzGerald, Citation2019), once more commonly exemplified by stereotyped representations of the female body (Russell, Citation2013).

A large share of the literature examining discourse surrounding trafficking has focused on the contents of media publications or NGO campaigns with the spotlight generally being on the United States – the “self-proclaimed” global leader in the fight against trafficking (Kempadoo, Citation2007) – and other countries in the Anglo-Saxon world. Considerably less scholarship has turned the analytical focus on different parts of the globe,Footnote3 or devoted particular attention to visual representations of trafficking (Krsmanović, Citation2020). Studies in other disciplines show that despite certain Western conventions of representation continuing to be dominant, around the world various groups have re-interpreted and ultimately re-worked numerous depictions of different phenomena (Albawardi & Jones, Citation2023). National and socio-cultural specificities are likely to affect whether prevailing visual representations are accepted, rejected, re-qualified or imbued with different meaning, with consequent reverberations over how a phenomenon is framed and understood by the general public and other relevant actors in each societal context.

The impact of representations on public sentiment and policy has been the subject of ongoing study and debate (Beale, Citation2006; Grossman, Citation2022; Mangal, Citation2022), further complicated by the intricacies of multimodal communication (Gunther & van Leeuwen, Citation2001) – namely the growing number of modes of communication beyond written word alone (e.g. visual, aural) – and the accrescent role of technology. Yet, the relationship between visual representations of trafficking and policy-makers’ understandings of the phenomenon in different national contexts remains underanalyzed. Through an exploratory examination of visual imagery related to trafficking, this paper strives to raise questions about the role of visuals in framing social issues – more specifically, trafficking in Italy – and the potential implications stemming from the use of specific media frames. The intent here is not of drawing cause-effect conclusions about mediatic influence on policy-making in the field of trafficking. As others have argued, the interaction between media and policy is shaped by a multitude of interlocking factors, which include the internal dynamics and pressures of the media industry, the modes of communication utilized, and the particular cultural, political and historical context that is being scrutinized (Beale, Citation2006). Making sense of these multilayered dialectic processes goes well beyond the scope of this article. Rather, by focusing on Italy, a country located in the South of Europe and on the most dynamic and thus allegedly most up-to-date form of visual imagery – that is online visual imagery available via Google, the number one search engine worldwide – this paper wishes to contribute to broadening the scope of existing analyses on the impact of media representations on societal understandings of trafficking.

The first section of this paper presents key insights gleaned from literature on imagery and policy-making. This is followed by a scene-setter for policies, practices and discourse around trafficking in the Italian context and a description of the methodology employed by the authors. Google images related to trafficking in Italy are then presented and analyzed with an eye to identifying patterns and trends, including vis-à-vis international literature on trafficking and national discourses.

The Visual and Policy-Making

In her book Media framing of human trafficking for sexual exploitation – a study of British, Dutch and Serbian media Krsmanović, (Citation2020) outlines the various domains of media influence, which include awareness raising, public support, policy change, influence, monitoring, deconstructing stereotypes, and shaping the environment in which trafficked people recover and exercise their rights. When it comes to the policy change domain, the media have the potential to fuel improvements in anti-trafficking policies, or conversely promote damaging policies. As Krsmanović’s research shows, although each national context is unique, the relationship between the media and government/policy is often a “two-way street” (Krsmanović, Citation2020, p. 141). Increased media reporting routinely occurs in response to a new policy, and concurrently, politicians react to the media agenda engaging with human trafficking issues.

While Krsmanović includes visual representations in her examination, as she herself concedes, limited attention has been granted to images and their influence in the trafficking field. This is a notable shortcoming, as research shows that imagery influences our understandings of the world, the ways in which we categorize various phenomena or box people as “good,” “evil,” “victims” and “culprits” (Traue et al., Citation2019). Moreover, in the post-modern era, the power of images also resides in the fact that they are polysemous. They “may be bent to multiple forms and purposes, to the construction and expression of the social imaginaries of modernity” (Kapferer, Citation2012, p. 8) and can therefore act as instruments to spread a certain worldview or reading of an issue and ultimately, wield power and instigate action.

Among scholars in the fields of communication, psychology and other disciplines, there is a general consensus that images are often more impactful, memorable (Newhagen & Reeves, Citation1992) and attention-grabbing (Garcia & Stark, Citation1991) than pure text and this holds true vis-à-vis members of the general public and policy-makers alike (Damasio, Citation1998). Examples of images which are said to have had an impact on political decision-making include the graphic depictions of the massacre of thousands of Bosnians in the 1990s, which according to Robinson (Citation2002) created a binding obligation for the international community to act. Similarly, the viral image of Alan Kurdi’s lifeless body washed ashore on a Turkish beach appears to have influenced attitudes toward Syrian refugees, leading to tangible policy outcomes, such as the immediate increase in resettlement targets for Syrian migrants in many Western countries (Adler-Nissen et al., Citation2020; Imanishi, Citation2022). Although no specific literature on the matter appears to be currently available, it can be argued that images and videos of COVID-19 patients fighting for their lives in intensive wards in the Lombardia Region in Italy – the hardest hit part of Europe at the start of the pandemic – might have worked in a similar manner. The public was frightened, the national government had to take action to limit the spread of infection, and several other European countries followed suit.

In the US, Jenner (Citation2012) has studied the impact of news photographs on issue salience among the public and policymakers, compared to news stories. He found that while environmental news stories increase public attention toward the environment and this is sustained over time, they do not appear to capture the attention of the U.S. Congress; on the other hand, photographs which appear in the media seem to spark a more immediate response from policy-makers, leaving the public somewhat undecided. Powell et al. (Citation2015) have looked into the differing impact of media visuals depicting war and conflict as standalone means of communication and as accompanied by text. Interestingly, when media messages include both visuals and text, images affect readers’ behavior intentions (desire to act in some shape or form through campaigning, petitioning or other), while text shapes their opinions of the conflict and relatedly, their support toward specific policies, regardless of the image utilized.

A more recent experimental study of refugee and gun control news further complicates the picture, uncovering the effects of multimodal media on individuals’ decisions to read – or altogether discard – political news. Use of imagery alongside text appears to further skew readers toward choosing news items which confirm their existing beliefs. Nevertheless, it would seem that even when there is lack of congruence between readers’ views and the perspectives presented, multimodal political news is conducive to stronger emotional reactions and higher levels of agreement than pure text (Powell et al., Citation2021).

These studies testify to the challenges of unraveling the multilayered interconnections between visual imagery and public sentiment and policy, and indeed, the hurdles to establishing clear-cut causal relationships. At the same time, they are also a testament to the important role played by images both as independent means of communication and in conjunction with textual elements, their potential to affect public views of certain issues and crucially, incite action/reaction by policy-makers – all excellent reasons to take visuals seriously.

While all of the literature mentioned thus far focuses on official media – whether national, local, and more or less mainstream – an additional challenge in unpacking the mutual influence between representations (textual and visual) and policy-making lies in the proliferation of a range of different sources of news and information in the online domain. There is currently meager research looking at the relationship between online discourse – let alone multi-modal discourse – by non-official media and policy-making. A noteworthy exception is a recent study focusing on online citizen journalism, media agendas and policy-making in China, which highlighted that online public opinions on social media influence the agenda of mainstream-oriented media, as well as partially impact the policy agenda (Luo & Harrison, Citation2019). The dearth of research in this area leads to a dearth of knowledge concerning how content – both textual and visual – available in the online domain and distributed both by traditional media and other actors, such as NGOs, influencers and more, affects policy-making. As previously mentioned, addressing these gaps in their entirety is no easy feat. The exploratory analysis of Google images related to trafficking in the Italian context presented in this paper makes a modest contribution to this decidedly larger endeavor by helping shed light on the range of actors actively involved in the (re)production of representations of trafficking in the digital space, whilst concurrently hoping to instigate future and more in-depth reflection on the impact of visuals on trafficking policy-making in Italy.

Setting the Scene – Trafficking and Its Representations in Italy

The examination of visual constructions of trafficking in Italy cannot do without a more general discussion about representations of human trafficking in the national context, their relationship with the broader migration scenario, and the complex intersections between smuggling and trafficking. Italy’s location at the borders of Europe has rendered immigration a chief concern as early as the 1980s, making the country a forerunner in the criminalization of migrant smuggling. The first piece of legislation governing the phenomenon, which effectively anticipated supranational obligations, dates back to 1989 and punishes “whoever carries out activities aimed at favouring [emphasis added] the entrance of foreigners into the territory of the state” (Militello & Spena, Citation2019, p. 7). From the 1990s onwards, Italy has implemented a range of laws striving to regulate various facets of migration with a key preoccupation being that of preventing and combating “illegal entry” (Colombo, Citation2013). Accordingly, media discourses have systematically relied on the tropes of invasion, threat and irregularity, thus reflecting developments in law and practice. Notwithstanding migration by sea being just one form of migration to Italy (Colombo, Citation2013), media reports are replete with images of overcrowded boats captioned with vocabulary such as “die,” “massacre,” “missing,” “wreck,” “sink,” “tragedy,” “drowning,” “victim,” “horror,” “traffickers,” and “smugglers” (Montali et al., Citation2013).

Aside from the emphasis on boat migration, Italy has also witnessed a blurring of smuggling and trafficking. While the complex overlaps between consent and coercion in the experiences of migrants journeying to Italy by sea (Aziz et al., Citation2015; Beretta et al., Citation2018) are frequently acknowledged, even in institutional settings (Ministero dell’Interno DIPARTIMENTO DELLA PUBBLICA SICUREZZA DIREZIONE CENTRALE DELLA POLIZIA CRIMINALE Servizio Analisi Criminale, Citation2021), they have largely been used as a justification to bolster efforts against irregular migration, viewed as part and parcel of the fight against transnational organized crime. The mounting involvement of agencies and departments commonly tasked with anti-mafia investigations which would generally not concern themselves with migration breaches, is a testament to this. The declared objective of their involvement is a more effective implementation of the Palermo protocol, yet as a 2022 report by a group of NGOs working on the frontlines underscores, anti-mafia operations have either had injurious repercussions on the lives of innocent migrants, or targeted the low-ranking representatives of criminal organizations. Purporting to combat organized crime, they have employed extremely invasive methods typical of anti-mafia investigations, and routinely embarked on “witch hunts” to seek out alleged culprits, all too often building their cases on a mere handful of testimonies (Arci Porco Rosso & Alarm Phone, Citation2021).

Alongside its “tough on irregular migration = tough on crime” approach, Italy has strongly advocated for the protection of victims of trafficking. The country was one of the first to adopt measures to contrast trafficking and severe exploitation, and promote action in support of victims (Palumbo & Romano, Citation2022). A major focus has been on trafficking for sexual exploitation, which continues to be described as the most widespread form of trafficking (Ministero dell’Interno DIPARTIMENTO DELLA PUBBLICA SICUREZZA DIREZIONE CENTRALE DELLA POLIZIA CRIMINALE Servizio Analisi Criminale, Citation2021; Osservatorio Interventi Antitratta, Citation2018). As Serughetti (Citation2018) aptly observes, over the years Nigeria has accounted for one of the main countries of origin of trafficked persons and – albeit with fluctuations from one year to the other – also for irregular migration. Migration from Nigeria thus exemplifies many of the tensions and contradictions mentioned so far, particularly with regard to “the interconnectedness of trafficking and smuggling along the migration route from North Africa to Southern Europe, and the convergence of voluntary and involuntary, economic and forced migration” (Serughetti, Citation2018, p. 18).

It should come as no surprise then, that a considerable number of NGO-led support programs for victims of trafficking cater to Nigerian women – particularly mothers with children – (Artibani et al., Citationn.d.; Osservatorio Interventi Antitratta, Citation2022; Save the Children, Citationn.d.) who generally reach the country by boat. The organizations offering support to trafficking victims include government-funded agencies and cooperatives, as well as religious organizations.Footnote4 While the form of support provided answers to baseline requirements set by the Italian government, each organization brings its own understanding of the phenomenon to the table, which translates into distinct approaches and practices. Despite the wide range of initiatives that are currently being rolled out in support of survivors, the most recent GRETA (Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings) report for Italy:

notes with serious concern that there is a significant gap between the above-mentioned figures of assisted victims and the real scale of the phenomenon of human trafficking in Italy, due to difficulties in the detection and identification of victims of trafficking, problems of data collection, and insufficient attention to trafficking for purposes other than sexual exploitation, as well as to internal trafficking. The authorities acknowledge that mixed migration flows makes it difficult to distinguish between migrants and those who are trafficked and/or in need of international protection. (GRETA, Citation2018, p. 8)

Thus, while Italy is said to be strongly affected by the trafficking phenomenon and to date, has implemented both initiatives to supposedly target traffickers and support victims, there are still severe gaps in available data making it arduous to get a real grasp of the issue. This is exacerbated by the above-mentioned conflations between trafficking and smuggling, and the widespread alarmist discourse surrounding irregular migration, reflecting unresolved tensions and dilemmas over the management of migration and diversity.

Methodology

Analyzing trafficking imagery on Google to identify its intersections with key elements of trafficking realities and discourse, necessarily implies understanding the platform’s core features and basic functioning. Google is by and large the most popular Search Engine worldwide. The number of Google searches per day has risen steadily over the years, from millions in the early 2000s to billions more recently (Seo Tribunal, Citation2018). The Google Search function is a fully automated solution relying on web crawlers (read: Internet bots), which download text, images and videos they find on the Internet. The content retrieved is then analyzed by Google, which examines textual and visual material present on pages, tags and more; ascertains whether a certain page is a duplicate; and finally stores it in a database called Google index. Not all pages end up being indexed, as indexing depends on the good quality of a page, its design and the absence of the so-called “noindex” rule, that in very simple terms can be described as a set of meta tags – namely snippets of code – that prevent Google indexing. When we type a query into Google, the system is designed to yield the results that are thought to be better and most relevant to the search [emphasis added] (Google Search Central, Citation2023). The argument goes that individuals and organizations which invest both in SEO (Search Engine Optimization) and in building a solid social media strategy, boost their online profile, thereby also improving their Google ranking (Benoit, Citation2017).

Regrettably, even if Google relies on seemingly objective factors, its assessment of “relevance” has been proved to be deeply discretional. Numerous scholars and activists have shed light on the structural faults underlying Google algorithms, ultimately questioning the quality of Google searches. Worrisome gender and racial biases emerging in many Google searches have begged the question of human prejudice influencing the functioning of seemingly objective technological processes (Papakyriakopoulos & Mboya, Citation2021). Safiya Noble’s book Algorithms of Oppression – How Search Engines Reinforce Racism is a powerful example of denunciation of Google’s chilling history of bias against Black girls and of the intersectional discrimination marring its algorithms (Noble, Citation2018). Visuals play a big role in Roble’s argumentation, as is evident in the account of her 2016 Google search of “gorillas” which shockingly yielded images of African Americans.

Despite being affected in first instance by the preconceptions which creators feed the technology, it is worth noting that the type of results users obtain are also influenced by other intervening factors, “which could include information such as the user’s location, language, and device” (Google Search Central, Citationn.d.). As opposed to making postulations about algorithmic bias, given the authors’ expertise and the focus of this article on visual imagery on trafficking in a specific geographical context, in this instance priority was given to the key intervening factors – namely location and language – that are most relevant to the analysis.

In order to explore digital imagery about trafficking in Italy and question its impact on framing the trafficking debate as well as its potential influence on policy, web scraping of images from Google Search results relative to Italy between July and September 2022 was carried out. Web scraping is a process by which a user can access and download large volumes of data from websites based on pre-defined criteria. Google image scraping for this study was conducted using Outscraper. Outscraper is an online web scraper, which does not require coding, thus allowing for users to easily download large batches of images off the Internet. The platform permits to set various search criteria to run queries on Google. These include unlimited keywords, desired number of image results (0–100+) and selection of the specific country that the search should focus on.

Four different searches were run via the system, including a few days prior to the International Day Against Trafficking in Persons, on the 31st of July also known as International Day Against Trafficking in Persons, in early August just a few days after the occurrence and finally, a month later, in early September. The keyword used was “tratta di esseri umani” (human trafficking). The search was capped at 50 images, meaning that the four searches yielded a total of 200 pictures. Outscraper generated an Excel file which comprised the following information: original query, position (Google image ranking), link to original image, source and source link. In cases where more than one image was featured, the banner or cover image was considered as main image. Given that there were negligible differences between image results on different dates, a decision was made to focus on the search conducted on 31st July, immediately following the International Day against Trafficking in Persons.

All the images retrieved were thematically analyzed in terms of subjects involved and type of image (e.g. photograph, infographic, drawing); content analysis of the 50 article titles emerging from the search was also conducted. The top 10 image results were selected for more in-depth content analysis guided by Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2021) grammar of the visual and inspired by Carol Bacchi’s What is the Problem Represented to Be (WPR) approach insofar as questioning how a problem is represented in visual imagery and teasing out the underlying assumptions and silences.

Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2021) grammar of the visual places a strong emphasis on composition and arrangement, presupposing that signs are never arbitrary and that the relationship between sign-maker and context should always be parsed. The methodological approach is one that draws on established semiotic principles which have come to be acknowledged as “conventions in the history of Western visual semiotics” (Kress & van Leeuwen’s, Citation2021, p. 1) and cover aspects such as viewer’s gaze, composition, framing and use of color. Although recognizing cultural and regional variations, the argument made is that the “seemingly ‘universal’ aspect of meaning (…) lies in general semiotic principles and processes, while the culture-specific aspects lie in their application over history, and in specific instances of use” (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021, p. 5). Moreover, inspired by Halliday’s meta-functions, the grammar of the visual offers guidance to identify the relationship between specific semiotic modes and functions served, which can be ideational (representing the world around and within us), interpersonal (depicting social actions, interactions and relations of community members) or textual (using text alongside visuals to shape meaning). This in turn can lead to categorizing visuals as “narrative” namely involving participants engaging in action or reaction processes, or “conceptual,” representing “participants in terms of their more generalized and more or less stable and timeless essences” (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021, p. 76).

The semiotic principles presented in Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2021) work were employed in this analysis to make sense of the compositional aspects of the images extracted, identify relevant semiotic modes and explore their effects on meaning-making. Bacchi’s WPR approach, which has been extensively utilized in studies on trafficking (Carson & Edwards, Citation2011; Chandrasena, Citation2022; De Shalit et al., Citation2021), served to critically analyze the representation of the problem made by the visuals, with attention being devoted both to the images themselves and to the use of captions, texts in photographs and the broader context of articles so as to better grasp their combined influence on framing the issue at hand.

Analyzing Visual Lexicon on Trafficking

A quick glance at the Google images extracted via web scraping reveals people to be the undisputed protagonists. In most cases, participants are Black and Minority Ethnic (BMEs) (n = 20) with a particular focus on children (n = 17) often viewed close-up and engaging with the viewer. There are also photographs of more or less large groups of people on the move (n = 10), as well as conceptual visuals of handcuffed/tied-up hands and feet, blindfolded faces with taped mouths, people confined behind bars or fences of some sort, hands signaling to stop, people covering their hands with their faces or barcodes (n = 24). Many of the latter are in black and white (n = 13) contributing to an overall sense of abstraction. What is striking is that apart from conceptual images, which clearly point to the notion of exploitation and even slavery, a significant number of images (n = 19) can easily be associated with migration – including boat migration and/or smuggling – humanitarian aid and more generally “difference.” There are very few graphics (n = 5) and infographics (n = 2) or text in images (n = 10). The preference appears to be for images with human subjects who “speak for themselves” or more conceptual representations.

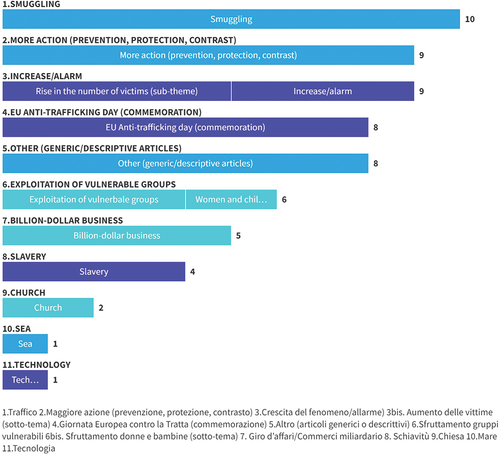

An analysis of the main words and concepts present in the titles of the online articles to which the images are linked reveals that “smuggling” (traffico) is the most recurrent theme/term (). This is not surprising given that in the Italian context the words “traffico” (smuggling) and “tratta” (trafficking) are often erroneously used interchangeably. Almost equally frequent is the call for more action and the use of words such as “growth” and “alarm,” including in relation to the increase in the number of victims. In addition, there are a range of articles focusing on EU Anti-Trafficking Day, more generic pieces on the definitions of the phenomenon itself or announcements related to new programs/activities. The exploitation of vulnerable groups, including women and children, trafficking as a “multi-billion dollar business” and slavery are also evoked, albeit to a lesser extent. While these themes generally align with the representations expressed by the imagery, as the more detailed analysis of the top 10 image results will show, the titles and textual contents of articles are sometimes out of synch with the accompanying visuals, reflecting what could be a poor editorial choice and/or the confusion surrounding trafficking and smuggling in the Italian scenario. Mismatches become even more patent if one read the captions accompanying the original image sources (provided under each image whenever available), which provide the background of the image itself. No original caption mentions the word trafficking, yet the images are being employed in articles on the topic of trafficking. These inconsistencies should not be underestimated, as studies on the role of visual messaging posit that the incongruence between visual and verbal message can be considered as a form of disinformation (Bucy & Joo, Citation2021).

The top 10 Google Search results for the search conducted on the topic of trafficking in Italy comprise articles by a host of organizations, ranging from media outlets, to NGOs, supra-national organizations and religious organizations, the latter being extremely active in anti-trafficking efforts in the country (see: , Annex 1 for further information). For each image included in this section, both technical aspects – drawing on Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2021) – and representational elements connected with trafficking are considered so as to provide a more in-depth assessment of the nature, content and potential influence of imagery on viewers and their understandings of the trafficking phenomenon. The images are categorized into three main groups: 1) people on the move/regularized migration; 2)difference/humanitarian aid; and 3) exploitation and slavery.Footnote5Footnote6

People on the Move/Irregularized Migration

Three images featuring in the top 10 Google search results for trafficking can be associated with the concept of “people on the move” and irregularized migration. The images are all “narrative images” namely pictures which tell a story; yet they involve different subjects (in terms of age, gender and ethnicity), situations (as regards modes of migration and stage in the migration journey) and settings (in terms of location), as well as exemplify different methodological choices from a visual perspective, which give rise to distinct emotions and messages.

features a boat packed with people, which is about to reach land. Most participants are on the boat, with three men standing in the water seemingly helping drag/push the boat. The picture involves many participants as reactors (participants who do the looking) and phenomena (what is being looked at, which we do not see). Migrants include men and women of different ages with certain attributes, such as clothing and color of the skin, giving hints about the region of origin of individuals and potential migration route. The photo is being taken from below, a technique which in this case makes the boat look larger, more prominent and threatening – somehow evoking the trope of invasion mentioned earlier on in the discussion of media representations of migration in the Italian context. There is only one participant who appears to be interacting directly with the viewer (reactor – phenomenon) with their gaze staring directly at them, yet his body is not facing the front; thus, in some manner he is inviting the gaze and at the same time, shielding himself and his “world” from it (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021). His demand does not appear to be a call for help, rather he conveys preoccupation with what awaits or perhaps strenuousness as a result of the journey and the effort he is making to help drag the boat to the shore. In the background, we can make out the outline of hills, although there is no clear marker that may help pinpoint a location. In the version published in Italian magazine Vita.it a textual caption was added at the bottom of the image, which reads “Trafficking in human beings, a 150 billion dollar business.” Despite this, the image could easily be associated with boat migration more generally.

Picture 2. Copyright: Sergey Ponomarev, with permission. Original image caption: over one million refugees entered Europe in 2015, most arriving by sea through Greece and Italy. Many landed in Greece and wanted to move on through the Balkan countries to enter the Schengen area of the European Union, where movement between member states does not require a passport. Balkan countries tended to steer refugees toward the next border in the most significant movement of people on the continent since World war II. Hungary, to the north, closed its frontiers, first with Serbia, then with Croatia.5 published in Vita.It, online magazine. “The voice of the not-for-profit”.

represents people on the move who may either be in transit or have just reached their destination and be awaiting release in the community. All participants in the photo are Black and most likely migrants from different African countries. There are individuals of all ages and all of those whose faces are discernible, appear to be men. They are seated on the floor very close to each other and are looking in different directions. The photo was taken from the left angle, and several participants in the foreground are glancing in that direction. No participant seems to be engaging frontally with the viewer. Their facial expressions range between blank, thoughtful, questioning, and perhaps even curious. The image conveys the feeling of time being suspended as there is no temporal or spatial marker. People are waiting, but are oblivious to how long they have been or will be waiting for. Just like , this image could easily depict irregularized migrants, who have likely been smuggled, yet the title of the article it accompanies reads “Trafficking in human beings, a business on the rise” making a clear statement about how the picture should be interpreted. Footnote7Footnote8

Picture 3. Source: AP. Original image caption: men sit on the deck of the rescue vessel golfo azzurro after being rescued by Spanish NGO Proactiva open arms workers on the Mediterranean Sea Friday, June 16, 2017. A Spanish aid organization Thursday rescued more than 600 migrants who were attempting the perilous crossing of the Mediterranean Sea to Europe in packed boats from Libya.7 published in Nigrizia – magazine founded by the comboni missionaries. Article title: trafficking in human beings, a business on the rise (IT: Tratta di esseri umani, un commercio in ascesa).8

features a cropped version of a photograph representing displaced people. While the original image depicted what appears to be a mother walking with her young children, in the photograph utilized by Italian newspaper Avvenire, the mother and two sisters have disappeared and we can now visualize the young girl on the left walking on her own in what appears to be the desert, alongside other people – allegedly families with children traveling on foot – whose silhouettes are visible behind her. While it is difficult to make assumptions as to who cropped the picture and the intentions behind it, the ensuing effect of such manipulation cannot be ignored. Although the original image conveys a sense of vulnerability at the sight of entire families being displaced, by representing the girl walking alone in the desert, her perceived vulnerability is amplified in the eyes of viewers as she “becomes” an unaccompanied female minor. Unlike the previous pictures where the participants appear to be crammed together, following editing, the main focus of this image is on the girl walking on her own. Her facial expression is somewhat strained and tired and her clothing is dirty with sand and soil, possibly a sign of the long journey already conducted. The central focus on the apparently lone girl, conveys a sense of solitude and fatigue, as she seems to be carrying all the weight of the journey on her small shoulders. The title of the article associated with this image reads ‘The emergency. Caritas: “Trafficking in human beings alongside Covid, violence and exploitation,” yet once again the image utilized simply represents migration, albeit a type of migration which is quite obviously conceived as arduous and perilous, particularly for young girls traveling on their own.Footnote9Footnote10

Picture 4. Source: FastMedia. Original image caption: 16 June, 2016 displaced people from the minority Yazidi sect, fleeing violence from forces loyal to the Islamic State in Sinjar town, walk toward the Syrian border on the outskirts of Sinjar mountain near the Syrian border town of Elierbeh of Al-Hasakah Governorate in this August 11, 2014.9 published in edited version (see image within white frame) in avvenire – self-described as a “Catholic-inspired” publication article title: the emergency. Caritas: “trafficking in human beings alongside covid, violence and exploitation”.

Difference/Humanitarian Aid

and are narrative representations that can be linked back to the concept of difference and humanitarian aid. Both pictures feature young Black boys, but while involves many subjects, primarily focuses on one subject in the foreground. In both pictures, participants (reactors) engage with viewers, yet do so in distinct ways. In the boys in the foreground are making a “demand,” inviting viewers in and opening up their world to them. Nevertheless, their bodies are either not visible or represented as slightly angled away from viewers – the perception is of the boys being portrayed as “other” (turned away) and simultaneously as “one of us,” individuals with whom we can engage (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021). They relate to onlookers, but from their own, separate world and their somewhat indecipherable facial expressions show some ambivalence about that interaction. The same cannot be said about the boys in the background, who engage in an “offer” and thus become objects of the viewer’s gaze. This objectification is nonetheless limited, as their faces and bodies are mostly hidden. On the other hand, in the boy’s body is facing the front and he is leveraging a demand to the viewer, who is not represented in the photo, yet invited into his world. In the background one can make out the blurred profiles of four other boys, most likely his peers, who are glancing in his and the viewer’s direction.

Picture 5. Copyright: Tom Niwemaani, with permission. Published in Repubblica – center-left newspaper. Article title: trafficking in human beings: the victims increase and amount to tens of thousands. However, prevention and contrast actions are also on the rise (IT: tratta di esseri umani: aumentano le vittime che si contano a decine di migliaia, ma si diffondono le azioni di contrasto e prevenzione).11

Picture 6. Copyright: action aid, with permission – Italian office of international NGO. Article title: the meaning of trafficking? In one word: slavery (IT: il significato del traffico di esseri umani? In una sola parola: schiavitù).12

While the setting of is quite obviously a classroom – and thus evokes the theme of access to school education in limited-resource settings – the background of is harder to decipher, particularly in the version published on Repubblica, where a few centimeters from the top and bottom have been cropped out. The children standing in the background have their arms lifted and appear to be holding on to something to avoid losing their balance. They could be standing on the back of a covered pick-up truck, glancing out to look at and/or smile at the viewers. This picture is somewhat reminiscent of the trope of child labor exploitation in low-resource settings, where it is common to see minors traveling on crowded pick-ups to their place of work. Nevertheless, there is a scarcity of markers hinting to this specific situation – i.e. no distinct clothing or accessories, no caption or accompanying text. An unsuspecting viewer seeing the picture on its own may simply interpret the image as representing a group of young boys heading somewhere together.Footnote11

Neither picture contains visual elements that make the relationship with trafficking obvious. However, accompanies the title “Trafficking in human beings: the victims increase and amount to tens of thousands,” which interestingly focuses on Latin America, showing a disconnect between image choice and textual content; and is associated with the title “The meaning of trafficking? In one word: slavery” and employs the words “smuggling” (IT: traffico) and “tratta” interchangeably, reflecting the conflations previously discussed in this paper.

Exploitation and Slavery

are all conceptual images, meaning that they rely on symbolism to express a concept. While picture 7 is a graphic and essentially different in terms of methodological choices, the remaining images bear numerous similarities. They are all, to an extent, abstract, because they “select specific details to reduce a phenomenon to what, in the context, are regarded as its essential qualities” (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021, p. 157). More specifically, they reduce the phenomenon of trafficking and even more so, the experience of victimization as a result of trafficking, to unidentified bodies or even body parts, be they chained feet or hands, blindfolded eyes and taped mouths. The use of black and white in and further enhances this sense of abstraction, stepping away from naturalistic representations of reality. appears to represent a child whose facial traits could be associated with Asian ethnicity, however there are too few elements present to reach a definitive conclusion.

Figure 10. Source: iStock. Published in Repubblica – center-left leaning newspaper.

Picture 7. Copyright: Luce website, with permission – describes itself as “the first publication on diversity, inclusion and cohesion.” Article title: trafficking in human beings, slaves still exist in Italy. Here’s who and how many they are. (IT: Tratta di esseri umani, gli schiavi in Italia esistono ancora. Ecco chi e quanti sono).13

Picture 8. Source: 123RF. Published in Difesa Popolo – weekly publication of the diocese of Padova. Article title: 18 October: European day against trafficking in human Beings.

Picture 9. Source: Adobe stock. Published on the website of the European parliament. Article title: stop human trafficking: the European parliament calls for more action (It: stop al traffico di esseri umani: il parlamento europeo chiede maggiore azione).15

Picture 11. Source: Pixabay. Published in Giustizia insieme – online magazine for lawyers and magistrates. Article title: first jurisprudence on human trafficking (IT: prime applicazioni giurisprudenziali in tema di tratta di esseri umani).17

is slightly different in that it is clear that the figures depicted are those of two children, standing on what appears to be a pile of rubbish, holding two cardboard cutouts which read “I’m not for sale” and “stop trafficking” in English. Given that their faces are not visible, despite relying on a different technique, this picture similarly contributes to the de-personification of participants. This picture recalls the phenomenon of “kids scavenging on rubbish dumps” (Actionaid, Citation2015) typical of some limited-resource settings, yet is patently artificial and staged in that it is unlikely that children in that setting rely on banners of the sort, and even more so choose to express themselves in the English language.Footnote12 The fact that the titles of the articles in which these images are used are generic titles on trafficking stands as evidence of the images merely serving to get across key concepts in a simple and direct manner, even if it comes at the expense of dehumanizing the subjects who are being represented and more broadly, the real or imagined communities to which they belong. Conceptual images such as these are reminiscent of the pictures commonly used in trafficking campaigns around the world, which have been examined and critiqued by other scholars in their work (Cojocaru, Citation2016; O’Brien, Citation2016, Citation2019). Nonetheless, in this case, the imagery does not make a direct link with sexual exploitation – an all-too-frequent trope in anti-trafficking – and merely channels the notion of slavery, or as per picture 11 in particular, labor exploitation.Footnote13Footnote14

is also associated with the theme of slavery and exploitation, yet does not feature dismembered bodies and constitutes one of the few graphics in the sample. Among the first elements which capture one’s attention is the broken chain cutting across the image from the right hand-side. The vector created by the chain is also broken – just like the chain itself – by a flock of swallows, flying away into the sky in different directions. The symbolism is that of the chain of slavery being ruptured and the slaves finally attaining freedom. Sense of perspective and depth are used to draw attention to the sky and the swallows, which embody the ultimate goal of freedom. Color is used strategically to create contrast between the right-hand side of the image, characterized by greater darkness and use of the red color and the middle and left-hand side dominated by lighter hues and higher brightness. The very light tonalities on the left-hand side of the picture suggest a sense of “ethereal brightness” (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021, p. 156) as if depicting some sort of ideal world, or desired/aspired outcome. More generally, the colors employed in the image – red, yellow, blue, green and black – do not contribute to a naturalistic representation and rather, fuel a sense of abstraction.Footnote15

The picture is mostly occupied by the sky, yet below the chain one can make out the silhouettes of the slaves, chained to one another by their necks, wearing garments covering their bodies from the waist to the knees. Some participants are visibly spent and have fallen to the ground (see for instance 4th participant from the right). The vector created by the slaves is parallel to the one created by the broken chain, making the conceptual association between the slaves and their condition of slavery as represented by the chain and the prospect of freedom symbolized by the swallows, more evident. The setting of the image is a vast field surrounded by mountains – again, there is no distinct characteristic which makes the location recognizable.

The picture clearly represents freedom from slavery, yet while one might be inclined to believe that it is a mere representation of the facts of history, from slavery to its abolishment, use of color, particularly in its lighter and more ethereal hues, hints to another level, namely that of “otherworldliness” and aspiration. In other words, rather than representing the historical abolition of slavery, the image may be denouncing ongoing forms of exploitation and striving toward a future where they no longer exist. This title to which it is associated “Trafficking in human beings, slaves still exist in Italy. Here’s who and how many they are” brings to bear the link between slavery and so-called modern-day slavery which the image appears to conjure. There are other two images present in the article, where the main participants are African women.Footnote16Footnote17

Discussion

The content analysis of imagery on trafficking in the Italian context paints a rather mixed picture. Both the more in-depth examination of the top 10 results and the categorization of the top 50 results reveal the presence of images depicting difference, humanitarian aid and people on the move, as well as conceptual images bearing signs symbolically associated with slavery and exploitation, such as “chains, shackles and padlocks, whip marks, wounds and bruises” (Krsmanović, Citation2016, p. 155), the latter strongly evocative of widespread visual representations of trafficking already identified by the critical trafficking literature. Thus, more “international” understandings of trafficking appear to coexist alongside national conceptualizations of the phenomenon, expressed through portrayals of migration and difference. The main ethnicity represented is Black, a reflection both of the reality of migration from Africa and of the racialized preoccupations which underpin it. Children, primarily girls, are the primary protagonists of most images. This is consistent with the media’s frequent use of imagery depicting children as a strategy to build empathy and compassion, a blatant example of which is the previously-mentioned photo of Aylan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy who drowned on the beach in Turkey, which has literally traveled the world (Rash, Citation2015). There is often a disconnect between titles and images evident in the fact that the most common word utilized in titles is “traffico” (EN: smuggling) and this is often associated with conceptual images relying on trafficking tropes.

The main themes identified resonate with the findings of research on media coverage of migration in Italy, which is characterized by the awkward marriage between touching images of suffering and representations of migration fluxes as a danger to the lives of citizens in the host country (ICMPD, Citation2017). Despite the evident contradictions between them, both pictures of suffering and images of “bothersome” migration flows depict and convey a sense of vulnerability, which comes through powerfully in the visuals analyzed in this paper. On the one hand, vulnerability is embodied by children hailing mostly from Africa, framed as vulnerable to trafficking, but more broadly visually illustrated as vulnerable to poverty and displacement. The dominance of pictures of girls hints to gendered understandings of vulnerability as an almost innate characteristic of young foreign females. The children featured represent “difference,” but concurrently elicit empathy. They invite viewers to engage with them in what could be interpreted as a cry for help. These representations of vulnerability summon viewers to tap into their inner “White Savior,” instigating them to take action, whether it’s by donating to an organization, signing petitions or other.

The conceptual images of shackled feet and chained body parts also provide a representation of vulnerability, yet one that is unlikely to fuel empathy or action, rather outrage with the portrayed subjugation of human beings. This rendering of vulnerability is occasionally out of time and place (e.g. in the black and white photos), yet is sometimes also a representation of “otherness,” when certain identity markers such as skin color or snippets of the background – if included – allow to discern a reality other than the West. In this case, the reaction is likely one of horror toward the atrocities that allegedly happen outside of one’s democratic country, where such brutalities would never be allowed. On the other hand, vulnerability is also presented as an attribute of the viewers looking in on the representations of the migration journeys of people fleeing their home countries. The photos depicting large groups of people crammed on boats or other means of transport are intended to elicit a sense of anxiety and relatedly, communicate the vulnerability of a country which continues to act as one of the first ports of arrival for migrants journeying to Europe.

Despite the dominance of images embodying the conflation between sex work and trafficking in anti-trafficking discourse (de Villiers, Citation2016; Gregoriou, Citation2018; Krsmanović, Citation2016) and trafficking for sexual exploitation being described as the most common form of trafficking in the Italian context, there are no sexualized images of women in the sample. More generally, there are only three adult women featured in the top 50 results. This may simply stem from the fact that the search relied on the keyword “trafficking” (IT: tratta) exclusively. This choice was intentional given that the article sought to explore how trafficking is generally depicted visually, in the Italian context. This also means that a search utilizing other complementary keywords, such as “sexual exploitation” (sfruttamento sessuale) will mostly likely return images such as the ones identified by the literature and conceivably shed light on other common representations of trafficking in the Italian context, for instance those of Nigerian women routinely identified as trafficked by the authorities. The fact that a generic search does not do so is a telling finding in its own right – if the average citizen were to type the work trafficking (“tratta”) into Google, the images emerging would bear little relationship with sexual exploitation specifically and rather, include a variety of images related to the themes discussed above.

A clear advantage of conducting a Google Search of trafficking imagery such as the one carried out for the purposes of this article, is that the results are not restricted to the media. The search yielded results linked to the websites of national and local media outlets, parishes, NGOs, legal organizations, European institutions and much more, providing a glimpse into the vast variety of actors engaging with trafficking in the Italian context and their multifaceted depictions of the phenomenon. A particularly interesting insight is the presence of a range of religious/religiously-orientated organizations not only among the top 50, but also among the top 10 results. This is a reflection of their involvement in the anti-trafficking field in Italy, as well as of the attention which they undoubtedly devote to their online presence.

Interestingly, there are only minor discrepancies between the imagery utilized by the different organizations. The only noticeable difference is the tendency by media outlets to use images relying on the trope of “invasion” exemplified by representations of people on the move crammed in overcrowded boats. NGOs and religious organizations prefer to rely on more emotive images depicting difference/humanitarian aid or conceptual images associated with slavery/exploitation, which in turn are also utilized by the media. While in her book exploring representations of trafficking for sexual exploitation in Serbia, UK and the Netherlands, Krsmanović (Citation2020) talks about the tensions between the media and anti-trafficking activists in the framing of trafficking stories, the findings presented here indicate that the visual imagery used by numerous NGOs/religious organizations engaging in anti-trafficking efforts is not radically different, nor less problematic than that employed by the media. A more focused search on NGOs only is needed to shed further light on the various representations of trafficking present in the anti-trafficking field, yet it would seem that the NGO sector needs to do more soul-searching with regard to the constructions of victimhood, vulnerability, gender and race which it is propagates. It is also worth noting that the comparison between the original image caption (when available) and the article title or novel caption shows significant incongruities and a use of images that is often decontextualized, even superficial. In two cases, both involving mainstream media outlets, original images were edited. In one case this led to a non-negligible distortion of meaning and interpretation. Such practices ought to be scrutinized further by scholarship with an eye to promoting more responsible and conscious use of imagery by the media and other organizations.

Finally, although this article can only aspire to provide tentative suggestions about the relationship between visual representations of trafficking and policy-making, it is striking to witness some of the tensions undergirding discourse on trafficking and more broadly, migration/management of diversity, emerging so brazenly in Google Searches. Images of migration and difference associated with titles referencing trafficking and the interchangeable use of the words trafficking and smuggling hint to deeper, unresolved dilemmas, that, as previously elucidated, appear to extend to policy-making. Further research ought to explore this relationship in more depth.

Limitations

Given the dynamic nature of the Internet, the main limitation of this article relates to the fact that imagery in the only domain is subject to constant change. Google rankings shift affecting the prominence of certain articles and the associated digital imagery. In a sense therefore, the images analysed herein may already be somewhat obsolete.

In addition, while this article makes tentative suggestions on the impact of imagery on policy-making, it does not establish any correlation or causation mechanism. In order to do so, more in-depth research relying on different methodologies - such as the ones utilised by authors quoted in the ‘visual and policy-making’ section of this article - is required. Moreover, as was previously mentioned, this article draws on Google image searches where the keyword ‘human trafficking’ was employed. Although this was intentional as the paper sought to explore how trafficking is ‘generally’ depicted visually in the Italian context, it may well be that a search utilizing complementary keywords, such as ‘sexual exploitation’ (IT: sfruttamento sessuale) will return different images from the ones collected, thus providing further nuance to the conceptualisation of trafficking in the Italian context.

Finally, it is worth noting that this paper has a narrow geographical scope limited to Italy and focuses exclusively on Google imagery. Comparative research extending to other countries in Southern Europe may yield further insights on imagery and policy. Utilising different online sources beyond Google is also likely to further enrich the analysis.

Conclusion

As this article was being penned, a popular Italian TV program hosted an expert debate on the stabbing of four children in a Parisian playground at the hand of a Syrian refugee. The conversation quickly took an abrupt turn – while initially discussing the route taken by the migrant to reach Europe from Syria almost a decade ago, within seconds speakers moved on to questioning the good nature of refugees and asylum seekers traveling to Lampedusa by boat. The discussion was interspersed with frenzied exclamations such as “There’s reason to be afraid!” (C’è da aver paura!).

Migration is, without shadow of a doubt, an important element of the Italian reality, past and present (Colombo, Citation2013). Anxieties over migration are deeply interrelated with broader uneasiness with diversity. Visuals have a lot to tell us about how a phenomenon is viewed and understood in a given society. In the Italian context, digital imagery associated with trafficking includes numerous pictures broadly related to migration and difference, which embody national anxieties, as well as conflations between irregular migration, smuggling and trafficking in discourse, policy and practice. By focusing on the Italian case study, this exploratory article contributes to discussions about the role of visuals in creating and reinforcing social constructions of trafficking within a given society, and raises questions about their potential interaction with policy-making. It builds upon current debates around trafficking representations, making the argument for further nuance and attention toward national specificities in discussions over trafficking discourse.

Concurrently, this piece opens up room for further exploration of a host of unanswered questions and issues. These extend to the impact of visuals associated to trafficking – both individually and in combination with text – on the views and perceptions of the general public and policy-makers; the cultural differences which exist between national and regional contexts in terms of representations, and the reasons underpinning potentially diverging constructions; the presence and role of trafficking imagery in the digital domain and the distinct use of visuals that the media make. Future research in this direction ought to bring together scholars from different disciplines drawing on diverse methodological approaches, thus contributing to the development of a more well-rounded understanding of the place of visual representations of trafficking in a world which puts increased emphasis on our sense of vision (Adkins, Citation2014; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Leger Uten Grenser. 2016. Anti-racism: When you picture Doctors Without Borders, what do you see? Available from.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8DFemg94ufU

2 Ibid.

3 Notable exceptions : Andrijasevic (Citation2007); Trujillo, Citation2016; de Sousa Santos et al., Citation2009.

4 See for instance: https://piattaformaantitratta.blogspot.com/

10 See: https://www.avvenire.it/mondo/pagine/caritas-covid-porta-a-maggior-sfruttamento-piu-vulnerabili

References

- Actionaid. (2015). Meet the kids scavenging on rubbish dumps to survive. Retrieved 2023, June 3, from. https://www.actionaid.org.uk/blog/news/2015/01/30/meet-the-kids-scavenging-on-rubbish-dumps-to-survive

- Adkins, K. (2014). Aesthetics, authenticity and the spectacle of the real: How do we educate the visual world we live in Today? The International Journal of Art & Design Education, 33(3), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12062

- Adler-Nissen, R., Andersen, K. E., & Hansen, L. 2020. Images, emotions, and international politics: The death of Alan Kurdi. Review of International Studies, 46(1), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210519000317

- Albawardi, A., & Jones, R. H. 2023. Saudi women driving: images, stereotyping and digital media. Visual Communication (London, England), 22(1), 96–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572211040851

- Andrijasevic, R. (2007). Beautiful dead bodies: Gender, migration and representation in anti-trafficking campaigns. Feminist Review, 86(86), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400355

- Arci Porco Rosso & Alarm Phone. (2021). From Sea to Prison: The Criminalization of Boat Drivers in Italy. Retrieved 2023, May 12, from https://dal-mare-al-carcere.info/

- Artibani, S., Balestrin, P., Ciambezi, I., Galati, M., Godino, M. E., Liotti, R., Luciani, V., Moroni, V., Pellegrino, V., Resta, C., & Taricco, M. (n.d). Right way. Retrieved 2023, May 20, from. https://www.apg23.org/downloads/files/La%20vita/Antitratta/RIGHT_WAY_ITA_WEB.pdf

- Aziz, A. N., Monzini, P., & Pastore, F. (2015). The changing dynamics of cross-border human smuggling and trafficking in the Mediterranean, report. New-Med Research Network.

- Beale, S. S. (2006). The news media’s influence on criminal justice policy: How market-driven news promotes punitiveness. William and Mary Law Review, 48(2), 397.

- Benoit, S. (2017). Does social media affect google authority and rankings? Media Group. 21 April 2017. https://jbmediagroupllc.com/blog/does-social-media-affect-google-rankings/

- Beretta, P., Abdi, E. S., & Bruce, C. (2018). Immigrants’ information experiences: An informed social inclusion framework. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(4), 373–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2018.1531677

- Bernstein, E. (2018). Brokered subjects: Sex, trafficking, and the politics of freedom. University of Chicago Press.

- Bischoff, C., Falk, F., & Kafehsy, S. (2010). Images of victims in trafficking in women. The Euro 08 campaign against trafficking in women in Switzerland. In Images of illegalized immigration (Vol. 9. pp. 71–82). transcript. https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839415375.71

- Bucy, E. P., & Joo, J. (2021). Editors’ introduction: Visual politics, Grand Collaborative Programs, and the opportunity to think big. The International Journal of Press/politics, 26(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220970361

- Carson, L., & Edwards, K. (2011). Prostitution and sex trafficking: What are the problems represented to be? A discursive analysis of law and policy in Sweden and Victoria, Australia. Australian Feminist Law Journal, 34(1), 63–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.2011.10854453

- Chandrasena, U. (2022). Can willing migrant sex workers be real victims of human trafficking? A wpr analysis of the Australian modern slavery act inquiry report. International Journal of Gender, Sexuality and Law, 2(1), 48–72.

- Cojocaru, C. (2016). My experience is mine to tell: Challenging the abolitionist victimhood framework‟. Anti-Trafficking Review, (7), 12–38. https://www.antitraffickingreview.org/index.php/atrjournal.

- Colombo, M. (2013). Discourse and politics of migration in Italy the production and reproduction of ethnic dominance and exclusion. Journal of Language and Politics, 12(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.12.2.01col

- Damasio, A. R. (1998). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. In The prefrontal cortex. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198524410.003.0004

- De Shalit, A., van der Meulen, E., & Guta, A. (2021). Social service responses to human trafficking: The making of a public health problem. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(12), 1717–1732. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1802670

- de Sousa Santos, B., Gomes, C., & Duarte, M. (2009). The sexual trafficking of women: Representations of illegality and victimization. Revista crítica de ciencias sociais, 87, 69–94.

- de Villiers, N. (2016). Rebooting trafficking. Anti-Trafficking Review, (7), 161–181. https://www.antitraffickingreview.org/index.php/atrjournal.

- Diritto alla protezione | Lazio. Retrieved 2023, June 2, from https://retezerosei.savethechildren.it/approfondimenti/diritto-protezione/le-minori-vittime-di-tratta-e-sfruttamento-sessuale/

- Garcia, M., & Stark, P. (1991). Eyes on the news. Poynter Institute for Media Studies.

- Google Search Central. (n.d.). In-depth guide to how Google search works. Retrieved 2023, May 2, from https://developers.google.com/search/docs/fundamentals/how-search-works

- Gregoriou, C. (2018). Call for purge on the people traffickers’: An investigation into British Newspapers’ representation of transnational human trafficking, 2000–2016. In Representations of transnational human trafficking. Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78214-0

- GRETA. (2018). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on action against trafficking in human beings by Italy. SECOND EVALUATION ROUND. Retrieved 2023, June 2, from https://rm.coe.int/greta-2018-28-fgr-ita/168091f627

- Grossman, E. (2022). Media and policy making in the digital age. Annual Review of Political Science, 25(1), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-103422

- Gunther, K., & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

- ICMPD. (2017). How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration? – a study by journalists, for journalists and policymakers, International Centre for Migration Policy Development,

- Imanishi, K. O. (2022). The boy on the beach: Shifts in US policy discourses on Syrian asylum following the death of Alan Kurdi. Media, Culture & Society, 44(5), 882–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437211069965

- Jenner, E. (2012). News photographs and environmental agenda setting. Policy Studies Journal, 40(2), 274–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2012.00453.x

- Kapferer, J. (2012). Images of power and the power of images. Berghahn Books.

- Kempadoo, K. (2007). The war on human trafficking in the Caribbean. Race & Class, 49(2), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063968070490020602

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2021). Reading images – the grammar of visual design. Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

- Krsmanović, E. (2016). Captured ‘realities’ of human trafficking: Analysis of photographs illustrating stories on trafficking into the sex industry in Serbian media. Anti-Trafficking Review, (7), 139–160. https://www.antitraffickingreview.org/index.php/atrjournal.

- Krsmanović, E. (2020). Media framing of human trafficking for sexual exploitation : a study of British, Dutch and Serbian media. Eleven International Publishing.

- Luo, Y., & Harrison, T. M. (2019). How citizen journalists impact the agendas of traditional media and the government policymaking process in China. Global Media & China, 4(1), 72–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419835771

- Mai, N. (2012). The fractal queerness of non-heteronormative migrants working in the UK sex industry. Sexualities, 15(5–6), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460712445981

- Mai, N. (2016). ‘Too much suffering’: Understanding the interplay between migration, bounded exploitation and trafficking through Nigerian sex workers’ experiences. Sociological Research Online, 21(4), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.4158

- Mangal, F. (2022). Case study: Role of media in policy making: Special reference to Afghanistan. Integrated Journal for Research in Arts and Humanities, 2(6), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.55544/ijrah.2.6.5

- McGarry, K., & FitzGerald, S. A. (2019). The politics of injustice: Sex-working women, feminism and criminalizing sex purchase in Ireland. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 19(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817743285

- Militello, V., & Spena, A. (2019). Between Criminalization and Protection: The Italian Way of Dealing with Migrant Smuggling and Trafficking Within the European and International Context (1st ed.). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004401723.

- Ministero dell’Interno DIPARTIMENTO DELLA PUBBLICA SICUREZZA DIREZIONE CENTRALE DELLA POLIZIA CRIMINALE Servizio Analisi Criminale. (2021). LA TRATTA DEGLI ESSERI UMANI in ITALIA FOCUS. Retrieved May 8, 2023, from. https://www.interno.gov.it/sites/default/files/2021-04/focus_la_tratta_10mar2021_10.30.doc1_.pdf

- Montali, L., Riva, P., Frigerio, A., & Mele, S. (2013). The representation of migrants in the Italian press a study on the corriere della sera (1992-2009). Journal of Language and Politics, 12(2), 226–250. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.12.2.04mon

- Newhagen, J. E., & Reeves, B. (1992). The evening’s bad news: Effects of compelling negative television news images on memory. Journal of Communication, 42(2), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00776.x

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press.

- O’Brien, E. (2016). Human trafficking heroes and villains. Social & Legal Studies, 25(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663915593410

- O’Brien, E. (2019). Challenging the human trafficking narrative: Victims, villains, and heroes (victims, culture and society). Victims, Culture and Society. Routledge.

- Osservatorio Interventi Antitratta. (2018). Sfruttamento sessuale. Retrieved 2023, June 7, from https://osservatoriointerventitratta.it/sfruttamento-sessuale/

- Osservatorio Interventi Antitratta. (2022). Seminario “Donne nigeriane vittime di tratta: la valutazione del loro ruolo di madri” – Napoli, 23 giugno 2022. June 8 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2023 from https://osservatoriointerventitratta.it/seminario-donne-nigeriane-vittime-di-tratta-la-valutazione-del-loro-ruolo-di-madri-napoli-23-giugno-2022/

- Palumbo, L., & Romano, S. (2022). Prostituzione e lavoro sessuale in Italia: Oltre le semplificazioni, verso i diritti. Rosenberg & Sellier.

- Papakyriakopoulos, O., & Mboya, A. M. (2021). Beyond algorithmic bias: A socio-computational interrogation of the google search by image algorithm. Social science computer review, 41(4), 1100–1125. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211073169

- Powell, T. E., Boomgaarden, H. G., De Swert, K., & de Vreese, C. H. (2015). A clearer picture: The contribution of visuals and text to framing effects. Journal of Communication, 65(6), 997–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12184

- Powell, T. E., Hameleers, M., & Van Der Meer, T. G. L. A. (2021). Selection in a snapshot? The contribution of visuals to the selection and avoidance of political news in information-rich media settings. The International Journal of Press/politics, 26(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220966730

- Rash, J. (2015). Even in the video age, still images move; a now-famous photograph of a drowned 3-year-old Syrian boy finally gets the world to take notice of the migration crisis. Star Tribune.

- Robinson, P. (2002). The CNN effect : The myth of news, foreign policy, and intervention. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203995037

- Russell, A. M. (2013). Embodiment and abjection: Trafficking for sexual exploitation. Body & Society, 19(1), 82–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X12462251

- Save the Children. (n.d.). LE MINORI VITTIME DI TRATTA E SFRUTTAMENTO SESSUALE. Save the Children.

- Seo Tribunal. (2018). 63 fascinating google statistics. Retrieved 2018, September 26, from. https://seotribunal.com/blog/google-stats-and-facts/

- Serughetti, G. (2018). Smuggled or trafficked? Refugee or job seeker? Deconstructing rigid classifications by rethinking women’s vulnerability. Anti-Trafficking Review, 11(11), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201218112

- Traue, B., Blanc, M., & Cambre, C. (2019). Visibilities and visual discourses: Rethinking the social with the image. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(4), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418792946

- Trujillo, J. M. (2016). Artistic representations of Andean diasporas: Food and carework; music and dance performance; and human trafficking. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Annex 1

Table A1. Top 10 Search Results for Italy by Organization and Page Title.