Abstract

Consultation and collaboration are identified by the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) as practices that permeate all aspects of service delivery. These practices allow school psychologists to extend their reach by collaborating with community organizations, shifting tasks to capable individuals who can complete those tasks more cost-effectively, and training key stakeholders to intervene with students to improve outcomes. Both consultation and cross-system collaboration promise to improve outcomes for marginalized students and may begin to address some structural inequalities related to school-based services. This article describes consultation and cross-system collaboration, reviews the history of scholarship in this area published in School Psychology Review, and highlights five articles appearing in this issue on these topics. Specific implications for future scholarship and implications for practice are highlighted.

Impact Statement

This article highlights the central role of consultation and collaboration in the practice of school psychology. These service delivery methods are essential in extending the reach of school psychologists to meet the needs of students, especially those from marginalized groups. Practitioners can benefit from the innovative application of community collaboration and the identification of factors that influence consultative relationships, student outcomes, and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords:

Approximately 10% of children in the United States meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder, and twice as many individuals experience sub-threshold but significant impairment related to a mental health difficulty (SAMHSA, Citation2013). However, in part due to a shortage of trained professionals, most children who would benefit from mental health interventions do not receive these services (Herman et al., Citation2021; Strein et al., Citation2003; Weist et al., Citation2014). Further, students from marginalized groups are even less likely to receive mental health support compared to their white peers (Zablotsky & Ng, Citation2023). Consequently, it is imperative that practicing school psychologists maximize their capacity to improve outcomes for the students they serve, especially those from marginalized backgrounds.

Consultation and collaboration emerged as an effective and efficient means to extend the reach of mental-health professionals (Albee, Citation1968; Hughes et al., Citation2014; Medway, Citation1979). The promise of these models for maximizing practitioner capacity has been recognized for over 50 years (e.g., Mayer, Citation1973) and is now understood to offer an evidence-based and efficient means to extend the reach of school-based professionals in supporting students from marginalized backgrounds (Hughes et al., Citation2014). The practices are widely implemented and permeate all aspects of professional activities (NASP, Citation2020).

Consultative services improve outcomes for target students by leveraging the dynamic relationship between consultees, such as teachers or parents, and the school-based consultant (Rosenfield, & Humphrey, Citation2012). Since its adoption into school psychology, consultation models have proliferated to encompass diverse approaches tailored to address specific needs within educational settings (Ingraham, Citation2017; Sander et al., Citation2016). These models include Mental Health Consultation, Instructional Consultation, and Systems-Level Consultation, among others. Despite the evolving landscape of consultation models, the problem-solving model remains the cornerstone of school psychological practice (Fallon & Bender, Citation2023). This model follows a structured four-step process, including: (a) problem identification, (b) problem analysis, (c) plan implementation, and (d) plan evaluation. The problem-solving model, also generally known as the behavioral consultation model, holds a substantial body of evidence supporting its effectiveness in improving student’s academic, behavioral, and social functioning (Fallon & Bender, Citation2023; Gormley & DuPaul, Citation2015; Reddy et al., Citation2000; Sheridan et al., Citation2019).

The triadic relationship within consultation describes the consultant as the content expert in the problem-solving process and the consultee as the expert on the child (also known as the client) and the child’s ecology. The systematic approach to consultation, as described by Kratochwill and Bergan (Citation1990), provides a vehicle to structure and clarify problems and, ultimately, verify the effectiveness of our work. Like other consultation models, the problem-solving consultation model extends services by alleviating a consultee’s presenting concern for a child while increasing the consultee’s knowledge and skills so that the consultee may address similarly situated problems in the future. Thus, consultation offers an avenue to increase consultants’ structural capacity by improving the consultee’s knowledge and skills.

Beyond knowledge of models and strategies for consultation, school psychologists must demonstrate effective communication and collaboration skills across various stakeholders to address the mental health needs of diverse student populations. Whereas consultation is a structured service-delivery framework, collaboration is best conceptualized as the approach to interacting with key stakeholders and other professionals brought together to achieve a shared goal (e.g., providing coaching and support to marginalized students). Subsequently, consultation models vary based on their level of collaboration. For example, the expert-model of consultation (i.e., a consultant is paid to provide their expertise to address a given concern) is frequently less collaborative relative to relationship-oriented models of consultation (e.g., conjoint-behavioral consultation [CBC] in which consultants work as co-equals with parents and teachers to address student concerns and build the parent-teacher relationship; Sheridan & Kratochwill, Citation2007).

Similarly, partnerships with community resources and organizations can vary in collaboration. For example, whereas one school district may allow a community psychological practice to offer services within their building, another district may ensure bi-directional communication with the outside agency, informing all relevant stakeholders (therapist, teachers, and parents) of student progress and facilitating consistent expectations across settings. High-quality and effective collaborations have been found to predict higher satisfaction levels, greater intervention adoption, higher implementation quality, and improved student outcomes (Erchul & Raven, Citation1997; Green et al., Citation2006; Gutkin & Curtis, Citation2009).

High-quality collaborations are marked by: (a) sincerity and respect, (b) trust, (c) effective communication, and (d) meaningful partnerships (Clarke et al., Citation2010). Briefly, sincerity and respect stem from a genuine belief that each member of the partnership is integral to achieving their shared goals and demonstrated by facilitating the co-equal participation of each stakeholder or partner agency. Trust is rooted in the belief that each collaborator has the best interest of the student(s) in mind, will carry out their role in the partnership, and will act in good faith. Trust can be demonstrated through transparency with other stakeholders, soliciting and accepting feedback and suggestions from partners, and following through on promises and obligations. Third, high-quality collaborations include effective communication, marked by the absence of jargon and the use of clear and concise language delivered in a manner each stakeholder can access and understand. Finally, strong collaborations require a deliberate commitment to fostering an active partnership. Such intentions must be explicitly stated at the partnership’s outset and reinforced throughout the collaboration.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

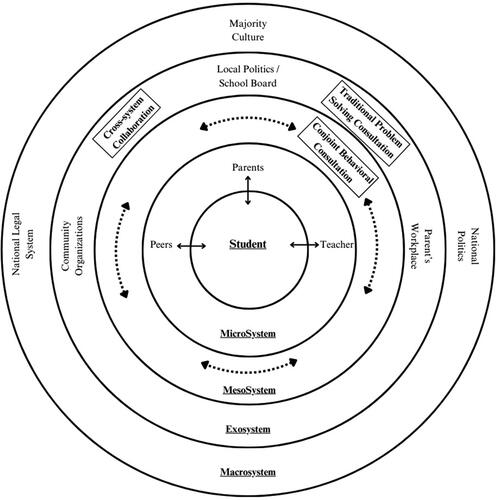

Consultation and cross-system collaboration are inherently grounded in ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979). This theory suggests that student behavior and development result from interactions within, across, and between the four systems surrounding children (i.e., microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem). The microsystem refers to the student’s functioning within a setting (e.g., home or school). The mesosystem refers to the interactions between these microsystems (e.g., a positive daily behavior report card resulting in positive reinforcement at home). The exosystem refers to systems in which the child is not directly present. However, the exosystem indirectly influences the child’s functioning (e.g., parents’ work schedule limiting their ability to assist the student with homework). Finally, the macrosystem refers to the broader social-cultural context (e.g., special education laws).

Each instance of consultation or cross-system collaboration will differ in the number of Bronfenbrenner’s systems they explicitly attempt to address; however, these activities inherently seek to promote student functioning by altering at least one system by which the student interacts or is indirectly affected (see ). Within the ecological framework, traditional problem-solving consultation creates a new exosystem (i.e., the consultant and consultee meeting without the student present) to address a given microsystem (i.e., the student’s classroom behavior; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977, Citation1979). In more collaborative consultation models (e.g., CBC), the mesosystem is explicitly targeted, as building and maintaining the parent-teacher relationship is a central intervention aim (Sheridan & Kratochwill, Citation2007). Further, collaborations with community agencies (e.g., community mentors or local churches) also address exosystemic variables (e.g., access to mental and physical health care) and can offset macrosystemic variables that negatively impact students, especially students from marginalized groups (e.g., racist ideologies and policies).

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

School psychologists are faced with significant structural barriers, such as limited resources and high caseloads, that hinder the efficient delivery of services and prevent students from accessing critical psychological services. Addressing these systemic structural barriers will require long-term efforts among multiple professional fields. However, consultative efforts may be particularly beneficial within the contemporary context of the national shortage of school psychologists and, subsequently, high caseloads through indirect service delivery and task shifting (Hart et al., Citation2021). Consultation offers school psychologists the opportunity to: (a) provide psychoeducation and intervention training to key stakeholders (e.g., teachers, parents, paraeducators), (b) facilitate point-of-performance intervention, and (c) support more students versus providing direct care (e.g., individual therapy). Collaboration affords the opportunity to access: (a) necessary expertise (e.g., collaborating with a physician), (b) additional resources or programs (e.g., collaborating with community agencies), and (c) information and partnership with other settings in which our students spend time (e.g., collaborating with parents and coaches to facilitate comprehensive assessment and consistent intervention across settings). Consultation and cross-setting collaboration also have the ability to begin addressing systemic inequalities in service delivery for students from marginalized backgrounds.

RATIONALE FOR THE SPECIAL TOPIC SECTION

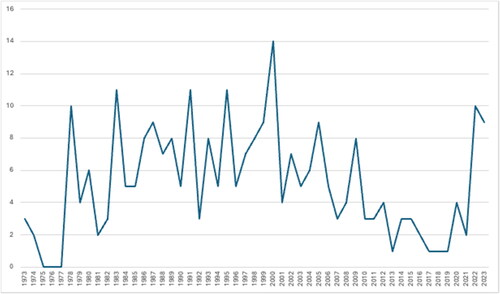

Since its adoption by school-based mental health professionals, consultation and collaboration have transitioned from theoretical concepts to evidence-based practices that permeate all professional activities (NASP, Citation2020). Through these developments, these models have continually expanded to meet new frontiers. These expansions have included responses to new developments in service delivery methods such as multidisciplinary teams, multi-tiered systems of support, and teleconsultation. School Psychology Review has a long history of commitment to these topics. Examining articles published in the journal that included the terms “Consultation” or “Collaboration” in the title or abstract revealed 268 non-duplicate articles between the years 1973 and 2023. When plotted by year (see ), the journal’s history of emphasizing these topics is apparent. Dating back to its second volume, the journal featured articles exploring methods to facilitate systems change through consultation (Carlson, Citation1973), expanding the role of counselors through consultation (Murray & Schmuck, Citation1973), and employing behavior modification procedures in the consultation process (Mayer, Citation1973). Research in consultation and collaboration flourished in the 1980s, with nearly 30 papers published in School Psychology Review, including some of the journal’s most widely cited papers (e.g., Fuchs & Fuchs, Citation1989; Gresham, Citation1989). These trends underscore the ongoing relevance and adaptability of consultation and collaboration in addressing the evolving needs of students, educators, and the educational system.

Figure 2. Number of Consultation & Collaboration Articles Published Per Year in School Psychology Review Since 1973

In the tradition of emphasizing the interconnectedness of various systems in influencing student functioning, there is a growing emphasis on tailoring consultation practices to meet the specific needs of diverse populations, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds. These approaches have also remained adaptive to meet new challenges in culturally responsive practices and socially just concepts (Fallon et al., Citation2023; Goforth, Citation2020; Ingraham, Citation2000; Luh et al., Citation2023; Parker et al., Citation2020). The articles published by Ingraham and colleagues (2000) in School Psychology Review over two decades ago have been instrumental in advancing understanding and implementation of multicultural and cross-cultural consultation in schools. These early on ongoing contributions highlight the field’s commitment to addressing systemic inequalities in service delivery, fostering cultural responsiveness, and exploring innovative models that extend the reach of school-based professionals. The continued exploration of these important topics holds promise for further advancing the field of school psychology and improving outcomes for all students. The articles in this special topic section continue this tradition by exploring collaborative partnerships to improve consultative practices and expand services to historically underserved populations, utilizing existing structures to maximize our efforts to serve the public.

Articles in the Current Special Topic Section

This issue includes five papers that explore consultation and collaborative services and have been specifically grouped to highlight the theoretical and practical effects of this innovative work on improving the delivery of student-level services. Two articles (i.e., Hart et al., Citation2021; Parker et al., Citation2022) describe collaborative partnerships to improve consultative practices and expand services to historically underserved populations by utilizing existing structures such as youth mentoring programs (Hart et al., Citation2021) and Black churches (Parker et al., Citation2022). The remaining three studies address aspects of consultation, including the role of racial match within the triadic relationship (Clinkscales et al., Citation2022), the role of target behavior framing on consultative outcomes (Schumacher et al., Citation2021), and finally, the cost-effectiveness of different levels of consultation intensity based on teacher characteristics (DeFouw et al., Citation2022).

Using an ecological framework, Hart et al. (Citation2021) describe a model that combines recent developments in school psychology with principles from community psychology to address long-ingrained limitations to school-based supports. The transdisciplinary approach outlined in their article integrates a youth mentoring program into a Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) framework to create an enhanced and dynamic service model that provides a broader coverage of services. Through a process known as task-shifting, school-based professionals may address the currently unmet demand of the field (McQuillin et al., Citation2019) while increasing access to services for historically underserved minority populations or individuals who express subclinical concerns that prevent them from qualifying for services. The community-based nature of the model also promises to reduce the stigma traditionally associated with traditional mental health services and help-seeking behaviors.

Working with a local Black Baptist church, Parker et al. (Citation2022) worked to co-develop an intervention and training support program to serve Black school-aged students, empower their families, and train pre-service school counselors and school psychologists in how to collaborate with Black families effectively. This initiative was begun in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated the virtual delivery of services to students and their families in addition to a virtual training experience for graduate student clinicians. This study focused on the virtual training delivered in the program, specifically evaluating the graduate students’ experience completing the virtual service-learning program and their perceptions of multicultural competence and social justice orientation development during the training and intervention program. The authors reported positive perceptions of the program, such that trainees felt they had increased their capacity to work with underserved students. Two primary themes emerged: (a) students felt more confident in providing adaptive and holistic interventions to their clients, and (b) the importance of presence and connection with marginalized youth and their families. With respect to the multicultural competence and social justice orientation development, four themes were identified: (a) increased openness and more positive beliefs of Black youth and their families, (b) increased knowledge of the disparities facing Black students, (c) building skills in fostering collaborative relationships, and (d) increased commitment to ongoing advocacy and allyship. Collectively, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of a virtual service-learning program that explicitly trains graduate students in school counseling and school psychology in building relationships with Black families.

Clinkscales et al. (Citation2022) evaluated the role of racial match between students and teachers on school psychologists’ perceptions of: (a) their own ability to collaborate with the teacher, (b) the teacher’s expectations for the student, and (c) the student-teacher relationship. Importantly, the authors developed two identical two-minute video vignettes, one addressing a reading referral and the other regarding a behavioral referral. The authors also had each vignette performed by one white teacher and one black teacher resulting in a total of four vignettes. For the academic referral, participants (who were overwhelmingly white) reported they could more effectively collaborate with the Black teacher, but found no effects on teacher expectations or the student-teacher relationship. Participants again reported they could more effectively collaborate with Black teachers for the behavioral referral and reported they could more effectively collaborate with the teacher when the student was Black. Notably, the authors found that when both the student and teacher were White, participants reported a lower perceived ability to collaborate with the teacher. The results underscore that different combinations of racial match can impact school psychologists’ perceptions regarding the consultative process. The authors highlight the importance of self-reflecting on potential bias when consulting and collaborating with teachers and provide practical reflection questions that can aid practitioners in navigating their biases when working with teachers.

In addition to the racial match, other aspects of consultation can significantly affect student outcomes. Schumacher et al. (Citation2021) conducted a secondary analysis of 267 consultation cases evaluating the effect of how a target behavior is worded on student outcomes. Cases were coded as having a positive target behavior (i.e., increasing a behavior) or a negative target behavior (decreasing a behavior). The authors found that the majority of cases (64%) were positively framed and that although framing had no impact on off-task behavior (consultation was effective regardless), a positively-framed target behavior was associated with improved teacher-rated internalizing symptoms and higher levels of student compliance compared to negatively-framed target behaviors. Results highlight how seemingly minor language differences can significant affect student outcomes and underscore the importance of positive (e.g., increased time on task) vs. negative (e.g., decreased calling out) framing when working with teachers and families.

Finally, DeFouw et al. (Citation2022) evaluated the effect of two different consultation models (standard problem-solving vs. enhanced consultation) for teachers who differed in their: (a) knowledge of behavioral principles, (b) beliefs regarding teachers’ responsibility for student academic and behavioral failure, and (c) skills in classroom behavior management as measured by a classroom observation. The enhanced condition included motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy techniques, in addition to the traditional behavioral problem-solving process, to address the knowledge, beliefs, and skills of teachers. Results indicated that the enhanced version was more costly than the standard version and took more time (38 vs. 23 min per session). However, despite the higher costs, the enhanced version was more cost-effective (i.e., greater positive impact on student outcomes per dollar spent) for teachers with low knowledge, skills, and intervention beliefs. Conversely, the authors reported that for teachers with high levels of class-wide behavior management knowledge and skills, and those with positive intervention beliefs, standard consultation is both more effective and costs less money relative to the enhanced model. Stated differently, the results of this study suggest that school psychologists must understand the characteristics of the teachers they are working with and tailor their intervention approach to match the level of need of that teacher. When the level of teacher support matches that teacher’s needs, student outcomes appear better.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

School consultation and cross-system collaboration are core aspects of school psychological services (NASP, Citation2020). The five articles included in the present issue highlight the benefits of cross-system collaboration for improving outcomes for students from marginalized backgrounds and address key considerations for conducting school-based consultation that can maximize the impact of practitioners on the students, families, and teachers they serve. Such information is vital given the shortage of qualified mental health professionals in many communities and the unique position of schools to reduce the gap in mental health access, especially for students from minoritized backgrounds.

These articles add to the long history of consultative and collaboration work published in School Psychology Review and highlight areas of need for additional scholarship. For example, the positive effects of a community partnership with an influential, predominantly Black church had positive effects on graduate training and could improve outcomes for marginalized youth (Parker et al., Citation2022). Additional scholarship exploring the mechanisms of successful partnerships with a variety of community stakeholders is warranted, as is a further expansion of virtual service training and service delivery (both for collaboration and consultation). Hart and colleagues provide a foundation for innovatively incorporating task shifting to extend the reach of highly trained school professionals. An empirical test of their framework is necessary to clarify the efficacy of this service delivery model, and further exploration is warranted to identify additional cost-effective ways of supporting the needs of students.

Clinkscales and colleagues found that racial match or mismatch has important implications for school psychologists’ perceptions regarding potential collaboration. The effect of these perceptions could be empirically evaluated to determine the real-life outcomes for the consultative relationship and subsequent child outcomes. Such work would have important implications for combatting bias in consultative relationships. The results from both Schumacher and colleagues and DeFouw and colleagues highlight a need to evaluate demographic and process variables that may affect the effectiveness of consultation (e.g., teacher knowledge, target framing, intervention framing) and how these combinations ultimately change the cost-effectiveness of school-based consultation. Stated differently, we need to learn more about what works best for whom under what circumstances.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matthew J. Gormley

Matthew J. Gormley is an Associate Professor at the University of Nebraska - Lincoln. His research focuses on improving outcomes for individuals with ADHD across their educational careers with a specific interest in the collaboration between families, schools, and healthcare settings that support these individuals. Dr. Gormley is currently an Editorial Fellow with School Psychology Review.

Justin P. Allen

Justin P. Allen is an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University and a Nationally Certified School Psychologist. Dr. Allen’s research examines school-based interventions to support struggling students with a specific focus on assessment and intervention practices within manifestation determination reviews; he also maintains an interest in advancing structured reviews to advance empirically informed practices. Currently, he serves as an Editorial Fellow with School Psychology Review.

Shane R. Jimerson

Shane R. Jimerson, PhD, is a Professor University of California, Santa Barbara and Nationally Certified School Psychologist. His scholarship focuses on understanding and supporting the social, emotional, behavioral, academic, and mental health development of youth and also understanding and advancing the field of school psychology internationally.

REFERENCES

- Albee, G. W. (1968). Conceptual models and manpower requirements in psychology. The American Psychologist, 23(5), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026125

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Carlson, J. (1973). Consulting: Facilitating school change. School Psychology Review, 2(1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1973.12086054

- Clarke, B. L., Sheridan, S. M., & Woods, K. E. (2010). Elements of healthy family-school relationships. In S. Christenson & A. Reschly (Eds.), Handbook of school-family partnerships (pp. 61–79). Routledge.

- Clinkscales, A., Barrett, C. A., & Spear, S. E. (2022). The role of racial match between students and teachers in school-based consultation. School Psychology Review, 53(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2087477

- DeFouw, E. R., Owens, J. S., Margherio, S. M., & Evans, S. (2022). Supporting teachers’ use of classroom management strategies via different school-based consultation models: Which is more cost-effective for whom? School Psychology Review, 53(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2087476

- Erchul, W. P., & Raven, B. H. (1997). Social power in school consultation: A contemporary view of French and Raven’s bases of power model. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 137–171.

- Fallon, L. M., & Bender, S. L. (2023). Best practices in behavioral consultation in schools. In A. Thomas, S. Proctor, & P. Harrison (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology (7th ed.). National Association of School Psychologists.

- Fallon, L. M., Veiga, M., & Sugai, G. (2023). Strengthening MTSS for behavior (MTSS-B) to promote racial equity. School Psychology Review, 52(5), 518–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1972333

- Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (1989). Exploring effective and efficient prereferral interventions: A component analysis of behavioral consultation. School Psychology Review, 18(2), 260–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1989.12085424

- Goforth, A. N. (2020). A challenge to consultation research and practice: Examining the “Culture” in culturally responsive consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 30(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2020.1728284

- Gormley, M. J., & DuPaul, G. J. (2015). Teacher-to-teacher consultation: Facilitating consistent and effective intervention across grade levels for students with ADHD. Psychology in the Schools, 52(2), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21803

- Green, B. L., Everhart, M., Gordon, L., & Garcia Gettman, M. (2006). Characteristics of effective mental health. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26(3), 142–152. consultation in early childhood settings: Multilevel analysis of a national survey. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214060260030201

- Gresham. (1989). Assessment of treatment integrity in school consultation and prereferral intervention. School Psychology Review, 18(1), 37–50.

- Gutkin, T. B., & Curtis, M. J. (2009). School-based consultation: The science and practice of indirect service delivery. In T. B. Gutkin & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.), The handbook of school psychology. (4th ed., pp. 591–635) John Wiley & Sons.

- Hart, M. J., Flitner, A. M., Kornbluh, M. E., Thompson, D. C., Davis, A. L., Lanza-Gregory, J., McQuillin, S. D., Gonzalez, J. E., & Strait, G. G. (2021). Combining MTSS and community-based mentoring programs. School Psychology Review, 53(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1922937

- Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., Thompson, A. M., Hawley, K. M., Wallis, K., Stormont, M., & Peters, C. (2021). A public health approach to reducing the societal prevalence and burden of youth mental health problems: Introduction to the special issue. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1827682

- Hughes, T. L., Kolbert, J. B., & Crothers, L. M. (2014). Best practices in behavioral/ecological consultation. In P. L. Harrison & A. Thomas (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology: Data-based and collaborative decision making (pp. 483–492). National Association of School Psychologists.

- Ingraham, C. L. (2000). Consultation through a multicultural lens: Multicultural and cross-cultural consultation in schools. School Psychology Review, 29(3), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086018

- Ingraham, C. L. (2017). Multicultural process and communication issues in consultee-centered consultation. In E. C. Lopez, S. G. Nahari, & S. L. Proctor (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural school psychology: An interdisciplinary perspective (2nd ed., pp. 77–93). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203754948-5

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Bergan, J. R. (1990). Behavioral consultation in applied settings: An individual guide. Plenum Press.

- Luh, H., LaBrot, Z. C., Cobek, C., Sunda, R., & Fallon, L. M. (2023). Social justice and multiculturalism in consultation training: An analysis of syllabi from school psychology programs. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 1–25. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2023.2261921

- Mayer, R. G. (1973). Behavioral consulting: Using behavior modification procedures in the consulting relationship. School Psychology Review, 2(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1973.12086055

- McQuillin, S. D., Lyons, M. D., Becker, K. D., Hart, M. J., & Cohen, K. (2019). Strengthening and expanding child services in low resource communities: The role of task‐shifting and just‐in‐time training. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(3-4), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12314

- Medway, F. J. (1979). How effective is school consultation?: A review of recent research. Journal of School Psychology, 17(3), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(79)90011-6

- Murray & Schmuck. (1973). The counselor as a consultant in organization development. School Psychology Review, 2(1), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1973.12086053

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2020). NASP practice model.

- Parker, J. S., Castillo, J. M., Sabnis, S., Daye, J., & Hanson, P. (2020). Culturally responsive consultation among practicing school psychologists. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 30(2), 119–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2019.1680293

- Parker, J. S., Haskins, N., Lee, A., Rodenbo, A., & O’Brien, E. (2022). School mental health trainees’ perceptions of a virtual community-based partnership to support black youth. School Psychology Review, 53(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2015248

- Rosenfield, S. A., & Humphrey, C. F. (2012). Consulting psychology in education: Challenge and change. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 64(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027825

- Reddy, L. A., Barboza-Whitehead, S., Files, T., & Reddy, L. A. (2000). Clinical focus of consultation outcome research with children and adolescents. Special Services in the Schools, 16(1-2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/J008v16n01_01

- Sander, J. B., Finch, M. E. H., Pierson, E. E., Bishop, J. A., German, R. L., & Wilmoth, C. E. (2016). School-based consultation: Training challenges, solutions and building cultural competence. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 26(3), 220–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2015.1042976

- Schumacher, R. E., Bass, H. P., Cheng, K. C., Wheeler, L. A., Sheridan, S. M., & Witte, A. L. (2021). The role of target behaviors in enhancing the efficacy of conjoint behavioral consultation. School Psychology Review, 53(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1938210

- Sheridan, S. M., & Kratochwill, T. J. (2007). Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family-school connections and interventions (2nd ed.). Springer.

- Sheridan, S. M., Witte, A. L., Wheeler, L. A., Eastberg, S. R. A., Dizona, P. J., & Gormley, M. J. (2019). Conjoint behavioral consultation in rural schools: Do student effects maintain after one year? School Psychology, 34(4), 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000279

- Strein, W., Hoagwood, K., & Cohn, A. (2003). School psychology: A public health perspective. Prevention, populations, and systems change. Journal of School Psychology, 41(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00142-5

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2013). Integrating behavioral health and primary care for children and youth: Concepts and strategies. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/Integrated_Care_System_ for_Children_final.pdf.

- Weist, M. D., Lever, N. A., Bradshaw, C. P., & Sarno Owens, J. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of school mental health (2nd ed.) Springer.

- Zablotsky, B., & Ng, A. E. (2023). Mental health treatment among children aged 5-17 years. National Center for Health Statistics.