The Armed Conflict Survey 2023 continues to capture a world dominated by increasingly intractable conflicts and armed violence amid a proliferation of actors, complex and overlapping motives, global influences and accelerating climate change. The recent global shocks caused by the coronavirus pandemic and the ongoing war in Ukraine have added to the woes of fragile states and regions, reinforcing root causes of conflict while curtailing resources available to address or at least mitigate them. Moreover, Ukraine’s unprecedented humanitarian and reconstruction needs are diverting ever more scarce international aid and development funding from other ongoing conflicts, which have been increasing in number over the last decade.Footnote1 According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ Financial Tracking Service (FTS), the percentage of international humanitarian funding available to Yemen and Syria decreased from 11% and 9% respectively in 2021 to 7% and 6% in 2022, with Ukraine being the largest recipient globally that year at 10% (up from 0.6% in 2021).Footnote2

The accelerating climate crisis continues to act as a multiplier of both root causes of conflict and institutional weaknesses in fragile countries. Such countries are often very vulnerable to the effects of climate change, because they become trapped in a vicious circle where conflict erodes the state’s ability to adapt and address climate impacts, while those same climate impacts contribute to conflict dynamics and governance failures.

At the global level, the intensity of conflict has also risen year on year in the reporting period of The Armed Conflict Survey 2023 (1 May 2022–30 June 2023), with the number of fatalities and events increasing by 14% and 28% respectively.Footnote3 This points to an increasingly problematic situation in many parts of the world in terms of humanitarian, stabilisation and reconstruction needs.

Conflict intractability and non-state armed groups

At the core of the grim outlook for conflict globally is the current complexity of contemporary wars, which often feature a large number of diverse non-state armed groups (NSAGs) as well as external interference. This, coupled with the diminished leverage of traditional resolution actors and processes, makes progress on their settlement a daunting task, contributing to their protractedness and resulting in little prospect for durable peace. The average duration of conflicts has increased over the last three decades amid an accelerated internationalisation of internal wars (which remain the most prevalent modality globally).Footnote4

Proliferating and ever-stronger NSAGs are among the main culprits of this situation. While their motivations, structures and modi operandi vary greatly within countries and globally, they share some common features. These include, notably, a universally growing importance as belligerent parties, political actors and providers of services and governance to the population under their control, as state legitimacy and reach deteriorate. They are also increasingly showing an unprecedented degree of fragmentation, with a myriad of small-scale groups competing for control and influence in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, among others. Meanwhile, centralised insurgent movements have been largely disappearing or losing importance, contributing to the complexity of the conflict-actor landscape globally.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), 459 armed groups of humanitarian concern were active globally as of June 2023, with around 195 million people living under their full or fluid control. Almost 80% of these groups provide some form of public services (including security, healthcare, education and social support) and/or extract taxes from the population under their control.Footnote5 This phenomenon is of notable concern for Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa, where a total of 295 groups operate, but it is also an issue in the rest of the world, with 83, 68 and 14 such groups active in Asia, the Americas, and Europe and Eurasia respectively. These actors are also becoming increasingly internationalised in terms of their presence, networks and operations amid continued support from and cooperation with third-party states, which often use them as proxies in internal conflicts of strategic importance to their foreign-policy goals. The ICRC estimates that 15% of armed groups globally give support to states, while 27% receive support from states.

Despite their crucial role in shaping and fuelling conflict dynamics, there is surprisingly little research and analysis devoted to capturing (and standardising) data on NSAGs’ varying typologies and features. In an effort to fill this gap, The Armed Conflict Survey series provides standardised information on NSAGs active in each country covered, including their strength, areas of operation, organisational structure and leadership, resources, and domestic and external allies and opponents. The Regional Analysis chapters in The Armed Conflict Survey 2023 also focus on the most important NSAGs per region, shedding light on their main characteristics, dynamics, and regional and global interlinkages.

Geopolitical competition further to the fore

Another driver of complexity, noted by The Armed Conflict Survey series since its inception in 2015, has been the increasing internationalisation of civil wars, through the intervention of a growing number and range of regional and global powers in pursuit of their strategic interests.Footnote6 This accelerating trend of great-power (as well as emerging- and revisionist-power) competition resembles Cold War-style proxy wars, and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has escalated it to a new level. The invasion has not only ignited arguably the most important inter-state conflict since the Second World War, but it has also aggravated geopolitical divides between Western powers and those which do not completely subscribe to democratic principles and the prevalent rules-based international order.

The ascendence of these powers (China and Russia, but also Gulf countries, Iran and Turkiye, among others) has far-reaching repercussions for global stability and security. Their increased foreign-policy assertiveness is one of the main causes of the demise of traditional conflict-resolution and peacemaking processes, given that these powers often undermine or simply bypass existing institutions and forums (including the UN). It is also adding to an ongoing trend of democratic backsliding in many fragile regions of the world. By intervening with transactional approaches and an anti-Western bias, these powers often prop up authoritarian regimes and disregard fundamental principles of international humanitarian law, contributing to the weakening of democratic institutions, the militarisation of politics and coups d’état.

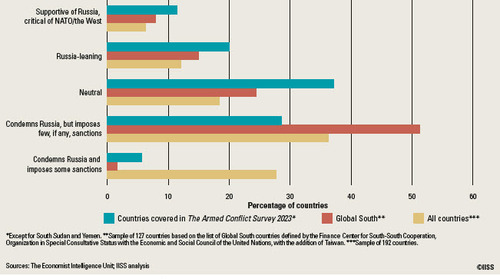

Finally, their ascendence, coupled with years of perceived disengagement from the West in many fragile and conflict-affected countries, has led to increased geopolitical fragmentation in the Global South. The war in Ukraine has accelerated this trend, as the divide between Russia and Western powers has become unbridgeable and securing allies has become a strategic imperative (especially for the former ). While Russia has faced widespread diplomatic isolation since the war began, many countries in the Global South have remained neutral or non-aligned despite Western powers’ efforts (see ), highlighting the latter’s diminishing influence and leverage in many parts of the world, including Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. This has important consequences for geopolitical balances in most active conflicts.

Global energy-transition and climate-change-mitigation strategies are also becoming an increasingly important focus of geopolitical competition – a trend that is sure to continue in the coming decades. Disagreements over mitigation responsibilities and competition for control of critical resources and technologies for the green transition will become important sources of inter-state tensions and will exacerbate current geopolitical divides. Notably, control of critical minerals for the green transition might drive third-party intervention in civil wars in resource-rich, fragile countries, while amplifying (or creating new) sources of disputes among domestic conflict parties.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies’ analysis filter for conflict has long added the geopolitical angle to the domestic dimension, in line with our global character and strategic research focus. Accordingly, The Armed Conflict Survey series has prominently featured regional and global drivers, interlinkages among conflicts across the world and international repercussions. Our Armed Conflict Global Relevance Indicator (ACGRI), now in its third edition, also benchmarks the global relevance of conflicts based on their geopolitical impact, as well as their intensity and human impact.

With geopolitics increasingly taking centre stage in the global conflict landscape, we have adopted a regional-focused approach for The Armed Conflict Survey 2023, with comprehensive Regional Analyses, as well as Regional Spotlight chapters on selected key regional trends. An increasing number of armed conflicts now have a consequential regional dimension which needs to be ascertained to fully understand or address them. This approach allows us to provide our audience of experts, practitioners and policymakers with unique insights into the geopolitical and geo-economic threads linking conflicts across the world, as well as their interrelations with domestic dynamics (covered in synthetic profiles of conflict-affected countries).

Bringing conflict complexity to life

The data-rich analysis throughout The Armed Conflict Survey 2023 is visually complemented by multiple graphic elements, including regional and conflict-specific maps, charts and tables. These illustrate core conflict trends during the reporting period and related data (including on military events, interventions, and humanitarian impacts and forced displacement), as well as regional and global links and spillovers. An exhaustive categorisation and analysis of conflict parties, together with regional timelines of key military/violent and political events for the reporting period, provide invaluable background information on the conflicts covered.

The accompanying Chart of Armed Conflict provides a visual snapshot of the global conflict landscape’s complexity, with its proliferation of NSAGs and increasing external interventions. For each of the conflicts covered in The Armed Conflict Survey 2023, the Chart depicts involvements by foreign countries, deployments by major geopolitical powers, multilateral peace and stabilisation interventions, regional data on armed groups of humanitarian concern, total fatalities and the ACGRI’s human-impact pillar.

Regional interlinkages and trends

The Armed Conflict Survey 2023 adopts an expanded regional focus compared to previous editions. This is in line with our efforts to offer a strategic assessment of the global conflict landscape, highlighting its most important drivers, trends and actors at any given time.

Each regional section includes an extended Regional Analysis chapter, providing an overview of the regional conflict trends, drivers and main actors (including coalitions, NSAGs and third-party interventions). The Regional Analyses also delve into the regional and international dimensions of the active conflicts and their future evolutions in each region, analysing prospects for peace and escalation, political risks and potential flashpoints to monitor at the regional level. This ‘horizon scanning’ exercise aims to provide forward-looking insights to inform the strategies of policymakers, practitioners and corporate actors operating in or near conflict-affected countries.

Regional Spotlights complement the Regional Analyses, covering trends of strategic importance for the region or the global conflict landscape. Trends highlighted and discussed include shifting drug-trafficking dynamics and new conflict zones in the Americas; the centrality of security guarantees in Ukraine’s future reconstruction efforts; policy best practices to address overlapping climate, political and food-insecurity crises in North Africa; the changing nature of jihadism in Sub-Saharan Africa; and the re-emergence of the Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP) in Pakistan and its implications for Asian security.

Americas

Armed conflict in the Americas remained mostly driven by criminal contestation over the control of lucrative illicit economies (notably drugs) in the reporting period, with multiple NSAGs fighting against one another and the state. These groups have, in time, also become political actors, infiltrating the state and challenging the latter’s territorial control and governance. Their regional linkages along drug-supply chains in the Americas have been increasingly accompanied by global spillovers, as criminal groups progressively extend their international reach in response to shifting profit margins and trends in international demand.

The reconfiguration of drug routes and criminal networks continued during the reporting period, with outbreaks of violence and escalation in countries that were, until recently, considered relatively peaceful, including Argentina, Ecuador and Paraguay. Mexican criminal actors continued to diversify their portfolio into synthetic-drugs (including fentanyl) production and exports to the United States, heightening diplomatic friction between the two countries. Environmental crime was also on the rise, often converging with traditional drug-trafficking activities (‘narcoecology’). Haiti’s economic, political, security and humanitarian crises spiralled out of control, with violent events and fatalities registering a 22% and 100% increase (respectively) year on year and little hope for improvement amid timid steps towards external interventions to stabilise the country.Footnote7

The start of the ‘total peace’ process in Colombia (involving simultaneous peace negotiations with all active criminal groups in the country) and small steps towards the stabilisation of the Venezuela crisis (including the definition of a path towards fair elections in 2024) are reasons for hope for regional peace. However, the outlook remains fraught with risks, given the complexity of both processes and slow progress at the negotiating tables.

Europe and Eurasia

Conflict in the region continued to be linked to dis-agreements over borders between countries, as well as Russia’s aspirations to restore dominance over the former countries of the Soviet Union and its position as a revisionist global power. Tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh built up in the reporting period, culminating in a third full-blown war on 19 September 2023 initiated by an Azerbaijani ‘anti-terrorist operation’ there. The war concluded in a matter of days with Azerbaijan’s decisive victory. The ethnic Armenian government in Nagorno-Karabakh agreed to disband its army immediately and its institutions by the end of the year. The war triggered a mass exodus of the ethnic Armenian population, with more than 100,000 of its estimated 120,000 residents fleeing to Armenia by the end of September 2023. The latest dramatic developments were partly caused by unresolved issues regarding the region’s final status after the 2020 war over Nagorno-Karabakh, which concluded without a final peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In Central Asia, border tensions between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which had erupted in April 2021, continued to flare up episodically, while the conflict between Georgia and Russia remained frozen but of concern. The latter continues to occupy the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia following its 2008 war with the former.

The war in Ukraine has been and remains unpredictable. The diplomatic deadlock and military stalemate (i.e., the slow Ukrainian advance) point to a potentially protracted conflict. Meanwhile, instability has also begun to spread into Russia itself. Acts of sabotage and arson, carried out by Ukrainian operatives and dissident Russians, have increased. There are also domestic cracks within Russia’s regime, exemplified by the Wagner Group mutiny in June 2023.

Ukraine has nevertheless begun planning for its post-war reconstruction with the support of the European Union, United Kingdom and US, among others, but this way forward will be challenging. In fact, the feasibility and sustainability of reconstruction will be inextricably linked to Kyiv obtaining meaningful security guarantees that ensure Ukraine’s future territorial integrity against external aggression. Further, the emergence of a Ukrainian domestic military industry is a critical pillar going forward because security guarantees will likely not include NATO membership.

Middle East and North Africa

With the exception of the Israel–Palestinian Territories conflict, the reporting period saw a stale-mate in conflicts across the region and a reluctant acceptance of the status quo by the international community, notably in Syria and Yemen – historically two of the region’s most violent wars. The Arab League welcomed back Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to its annual summit in May 2023, more than a decade after it expelled the country due to Assad’s conduct. Turkiye also started normalising relations with Assad. In Yemen, Saudi Arabia entered into direct negotiations with Ansarullah (the Houthi movement), putting the kingdom on a path that will likely result in recognition of Houthi rule over Sanaa and northern Yemen and the eventual partition of the country. The conflict in Libya remained at a stalemate, with the country divided between competing governments, while Iraq and Egypt both saw a decrease in fighting. Turkiye and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party continued to clash, but with no significant loss of territory.

The Israel–Palestinian Territories conflict witnessed increased tensions and fighting, notably in the West Bank, where levels of violence have been at their highest since 2005. Israeli security services conducted an unprecedented number of deadly raids on Palestinian towns, while Palestinians continued lone-wolf violent assaults against civilians and the security sector. Violence was exacerbated by the Israeli extreme right-wing government, which continued settlement building and its attempts to strengthen the executive branch at the expense of the judiciary.

The spike in food prices has compounded the region’s extreme climate-change vulnerability to create a major food-insecurity crisis, especially for import-dependent countries, notably in North Africa. The region’s ability to tackle these multiple crises will have important implications for regional security dynamics as well as global energy security.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa continued to be the most conflict-affected region globally, with wars largely concentrated in four adjacent theatres – the Sahel, the Lake Chad Basin, the Great Lakes Region and East Africa – as well as the Central African Republic and Mozambique. Most conflicts there have internal, regional and international elements which contribute to their intractability.

Notable developments during the reporting period included the breakout of conflict in Sudan between the Sudan Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces in April 2023, which engulfed Khartoum, other urban centres and peripheral regions, with critical regional implications; the end of the two-year civil war in Ethiopia with the signing of a peace agreement between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in November 2022; the reignition of inter-state tensions between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda; the end of France’s Operation Barkhane and its pull-out from Mali and Burkina Faso; and the announced withdrawal of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, amid a wider drift towards military authoritarianism across the Sahel (with Niger being the latest country experiencing a military coup).

Although overall levels of violence in the region remained broadly unchanged year on year, jihadist violence markedly increased, especially in Somalia and the Sahel. Jihadist groups in the region have been evolving, becoming much more localised and intertwined with community and ethnic conflicts. Their international ties to the Islamic State (ISIS) and al-Qaeda have weakened, and connections between insurgent groups now appear to be limited to intra-regional collaborations.

Asia

Violence has significantly reduced in two of the three most consequential conflicts in Asia, those in Kashmir and Afghanistan, amid a continuation of the ceasefire brokered in February 2021 between India and Pakistan for the former and the consolidation of power and territorial control of the Afghan Taliban for the latter. On the other hand, the conflict in Myanmar between the military junta and a coalition of pro-democracy forces and ethnic armed organisations, following the former’s coup in February 2021, continues despite sanctions imposed by the West on the State Administration Council (Myanmar armed forces or Tatmadaw) and the suspension of aid.

There is a risk that inter-state tensions between nuclear powers in the region could escalate into major conventional wars, including those between the US and China over the Taiwan Strait, between Pakistan and India along the Line of Control, and between China and India along the Line of Actual Control. Of these conflicts, the first two carry the highest risk of escalation.

The risks represented by the TTP to regional security and Pakistan’s security and political stability have grown as the group has increased its activities in the region. Pakistan’s deep political crisis and upcoming elections will make it difficult to reach a consensus around implementing an effective counter-terrorist strategy.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://doi.org/10.1080/23740973.2024.2307740).

Notes

1 The total number of conflicts as captured by the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset has been consistently on the rise since 2011, totalling 137 in 2022, among the highest in three decades. UCDP disaggregates between state-based (i.e., at least one conflict party is a state) and non-state-based armed conflicts (i.e., conflict parties are exclusively NSAGs), and defines an armed conflict as the ‘use of armed force between two parties’ that ‘results in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year’. Conflict ‘parties’ can be either state- or non-state-based depending on the type of conflict under consideration. Based on this definition, each country can have several different ongoing conflicts per year. This methodology explains the larger number of conflicts accounted for by UCDP compared to those identified in The Armed Conflict Survey 2023, which adopts the country as the primary unit of analysis. See UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset Version 23.1 and UCDP Non-State Conflict Dataset Version 23.1. Nils Petter Gleditsch et al., ‘Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 39, no. 5, 2002, pp. 615–37; Shawn Davies, Therese Pettersson and Magnus Öberg, ‘Organized Violence 1989–2022 and the Return of Conflicts Between States?’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 60, no. 4, 2023; Ralph Sundberg, Kristine Eck and Joakim Kreutz, ‘Introducing the UCDP Non-state Conflict Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 49, no. 2, 2012; and Uppsala Universitet, ‘UCDP Definitions’.

2 IISS calculations based on data reported as of 26 July 2023. This data refers to funding from multilateral organisations and governments only. See FTS, ‘Total Reported Funding 2021’; and FTS, ‘Total Reported Funding 2022’.

3 IISS calculations based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com.

4 For more details on both trends, see ‘The Long Aftermath of Armed Conflicts’, in IISS, The Armed Conflict Survey 2021 (Abingdon: Routledge for the IISS, 2021), pp. 22–8.

5 This data is drawn from the annual ICRC survey on armed groups completed in June 2023. The ICRC uses the generic term ‘armed group’ for a group that is not a state but has the capacity to cause violence that is of humanitarian concern. Armed groups also include those groups that qualify as conflict parties to a non-international armed conflict according to the Geneva Conventions, which the ICRC defines as ‘non-state armed groups’. See Matthew Bamber-Zryd, ‘ICRC Engagement with Armed Groups in 2023’, ICRC Humanitarian Law & Policy, 20 October 2023.

6 In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, there are currently more armed conflicts with external intervention and regional dimensions than purely internal ones (i.e., confined within the borders of one country).

7 IISS calculations based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com.