ABSTRACT

In outdoor spaces, people can adapt to urban microclimates even if they are outside comfortable standards. This adaptation needs to be triggered by external motivators – enjoying the city, seeing people, meeting friends, and so forth – and these motivators are culture and place dependent. Relationships between socio-cultural values and adaptation to urban microclimate can inform design to promote adaptive capacity, enhance liveability, and improve climate change adaptation. We use the urban comfort concept, which considers human comfort in open spaces as a result of regional identity and local culture; lifestyle, liveability, and urbanity; and adaptation to microclimate. This study adds to the body of emerging case studies by exploring the local meaning of urban comfort in Aachen (Germany), a multi-cultural city. A mixed-method interpretive research design enhances the understanding of meaning and context. Results suggest that urban comfort is associated with (1) regional identity related to local physical and social landscapes; (2) urban lifestyles, liveability and urbanity concepts associated with compact urban living, public green areas, building design and diversity; (3) adaptive strategies associated with mobility, clothing, and company. We argue that the role these preferences play in place-based adaptation is fundamental for urban sustainability and climate change.

Introduction

The qualities of urban environments, including microclimatic conditions, are important variables that influence use and activation of public open spaces. The role of culture in human adaptive capacity to their surrounding thermal environment has gained increasing attention in the last decade. Studies highlight that ‘cultural background contributes to variations in thermal perceptions, tolerance to, and preference for certain thermal conditions, thermal comfort requirements and expectations, choice of clothing, and environmental attitudes’ (Naheed and Shooshtarian Citation2021, p. 13). This evidence of cross-cultural differences in thermal comfort conditions between residents in different countries and cultural backgrounds, demonstrates a wide thermal comfort zone and different types of adaptation (Knez and Thorsson Citation2008, Lin et al. Citation2011, Aljawabra and Nikolopoulou Citation2018, Lyu et al. Citation2023). In this context, understanding the role of sociocultural values in promoting or inhibiting adaptation to different microclimatic conditions can help improve urban design and planning strategies in face of urban climate change adaptation (Tavares et al. Citation2019). While studies relating to cultural background and thermal perceptions have gained some attention in recent years (Naheed and Shooshtarian Citation2021), observational studies on identity and collective cultural meanings of climate, weather and place that affect people’s experiences and activities in urban open spaces are lacking (Brychkov et al. Citation2018, He et al. Citation2020, Kwong et al. Citation2021), but essential to understand human adaptation capacity (Barnett et al. Citation2021).

We focus on this gap by asking how people adapt to the local weather and climate in order to enjoy public spaces, and how this adaptation is collectively shaped by regional identity and culture. Through an interpretive analysis, it explores how Aachen’s public open spaces are used in respect to microclimate. This study is informed by the urban comfort concept that consider human comfort in open public spaces as a cultural outcome. Previous investigations in Christchurch (New Zealand) show that urban comfort is mainly influenced by three interconnected factors: regional identity and local culture; urban lifestyle, liveability, and urbanity; and adaptation to urban microclimate (Tavares et al. Citation2019). Christchurch has a very defined urban character and is geographically remote – conditions that help keep a strong local identity. However, the study has been less suitable to explore how multi-cultural city dwellers collectively respond to local climate and shape their urban comfort requirements. Aachen is a valuable case study in this regard. It is the westernmost large border city in Germany. Aachen’s location, where the borders of Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium intersect (), implies cultural exchange, including a mixture of languages and cultural habits. In addition, Aachen features one the highest-ranking universities in Germany attracting students and researchers from around the world. From an urban climate perspective, Aachen is a valuable case study, as it is located in the surroundings of the Central European Uplands, a common geographical condition of large areas in Central Europe (Sachsen et al. Citation2013).

Figure 1. Aachen’s location in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Western Germany (Source: Wikimedia commons).

Responding to the identified research gap, namely the lack of studies identifying relationships between culture and thermal perceptions, this paper uses Aachen to investigate urban life and climate response in a multi-cultural city by asking about the relationships between socio-cultural and physical environments that enhance urban comfort. The hypothesis is that even in sub-optimal urban microclimates, design can promote adaptation by responding to and accommodating activities that have cultural meaning. The novelty in this approach is the cultural lens applied to adaptive strategies in a multi-cultural place.

In this context, climate-responsive urban design that considers the cultural dimension and the flexibility, or adaptive capacity, given by ‘living in a place’ is vital to any future notion of sustainability (Erell Citation2008). To make sense of this phenomena and the aspects involved in ‘living in a place’ that are related to human adaptive capacity to their surrounding thermal environment, we introduce five key concepts that are explored in Aachen: regional or local identity, lifestyle, liveability, urbanity, and adaptive strategies.

Regional or local identity

When shared by a community, experiences that add meaning to place may become part of a regional or local identity. Regional identity relates to the uniqueness of specific regions and places, and the identification of people with them. It often connotes natural or cultural attributes, such as landscapes, seasonality, language, and food, which are seen both as determinants and expressions of identity (Paasi Citation2012). This regional approach has been suggested as an important dimension in addressing climate change to avoid generic strategies that are high level, avoid dealing with the complexities of place and, as a consequence, do not address the local needs (Taylor Citation2023). Regional identity constructs, therefore, may shape people’s response to urban environments and their weather and climate both through identity itself and symbolic interaction between people and between people and place (Strauss and Orlove Citation2003, Fine Citation2007, Del Casino and Thien Citation2020, Tavares et al. Citation2019).

Lifestyle

While regional identity is place-based, lifestyle can be associated with a way of living – e.g. urban lifestyle, rural lifestyle, sustainable lifestyle and so forth. Such ways of living do not necessarily relate to a specific place. However, they may have different characteristics that fit the regional identity of the place where they happen (see, for example, Lilius Citation2021). The understanding of urban lifestyle preferences as a collective construct and its relationship with local culture and climate is crucial for urban planning and design, and for providing urbanity (Dovey Citation2010).

In this study we define lifestyle as daily life routines and values as a consequence of collective meanings, in other words, a way of life that defines and reinforces identity (Van Diepen and Musterd Citation2009, Boone et al. Citation2014), or a set of activities that generate the urban spaces’ dynamics and character.

Liveability

Another concept arisen from the understanding of urban lifestyle preferences as a collective construct is liveability, which according to Lowe et al. (Citation2015) is a contested concept with many meanings. In this study we focus on the relationships between place meaning and identity (Masterson et al. Citation2017, Verbrugge et al. Citation2019), leading to certain place characteristics that make them urban environments that are attractive places to live from the perspective of specific cultures (Leby and Hashim Citation2010).

Different factors have been introduced as the criteria to liveability, such as to be pleasant, safe, healthy, affordable, and supportive of human community (Lowe et al. Citation2015, Bedi et al. Citation2023). In addition, the thermal performance of urban space (Chatzidimitriou and Yannas Citation2015, Shi et al. Citation2019, Teshnehdel et al. Citation2020, Kim et al. Citation2022) and human thermal comfort (Klemm et al. Citation2015, Lenzholzer et al. Citation2018) aim at providing pleasant and safe environments that are liveable and conducive to urban life and urbanity. Hebbert and Webb (Citation2012), for example, studied the impact of urban form on microclimate and its potential for enhancing or reducing the quality of urban life in Stuttgart, where the local weather systems are considered and managed through physical planning. Their conclusions highlight the importance of understanding microclimate for the liveability of cities, particularly when considering climate change.

Urbanity

Lifestyles can also be associated with urbanity (Latham Citation2003, Wesener Citation2018) as they interact and shape each other. The concept of urbanity is diverse, often diffuse, and has changed over time. From a historical perspective, Schneider et al. (Citation2014) argues that in the early 20th century, urbanity was related to specific urban identity constructs; however, in recent decades notions of urbanity have been related to various urban lifestyles and experiences of plurality and difference (Dovey et al. Citation2016, Wesener Citation2018). In this study, we use the more recent definition to express the feeling of plurality distinctively provided by some urban spaces, its dynamics and capacity for exchange and communication promoted in some spaces (Castello Citation2010), or a combination of the most diverse social things in the smallest space (Lévy Citation1997), promoting social interaction. Urbanity has been investigated from different perspectives including identity (Lilius Citation2021), lifestyle (Latham Citation2003, Van Diepen and Musterd Citation2009), sustainability (Boone et al. Citation2014), economic and political considerations (Latham Citation2003, Lowe et al. Citation2022). Often, physical attributes, built form, and urban design qualities tend to dominate discussions on urbanity (Lévy Citation1997, Montgomery Citation1998, Castello Citation2010, Wesener Citation2018). While urban spaces and their distinct qualities shape urbanity, in this study we focus on how notions of urbanity may affect people’s adaptive capacity to the climate, and how this adaptation could be affected by regional identity.

Adaptive strategies

Studies on adaptation to climate have focused on thermal comfort indices to help understand people’s responses to air temperature (Fanger Citation1973, Höppe Citation1999, Elnabawi and Hamza Citation2020), including personal parameters such as clothing insulation and metabolic rate. Although thermal comfort is defined as ‘a condition of mind’ (ASHRAE Citation2001), these indices are focused on physiological parameters and physical variables, not considering that the meanings of thermal comfort may also vary in different social and cultural contexts. Recent studies, such as Brychkov et al. (Citation2018), have focused on the cultural background impacting thermal comfort responses, concluding that they exist and relate to thermal responses, but without unpacking the culture specificities and the connections. Our premise is that adaptation capacities to microclimatic conditions are a key factor on the use of public open spaces. Outdoor thermal comfort or discomfort affects people’s decisions of staying outdoors. It is one of the factors that influences activity and utilisation patterns of streets, plazas, playgrounds, urban parks, and so forth (Givoni et al. Citation2003, Erell Citation2008, Aljawabra and Nikolopoulou Citation2010, Erell et al. Citation2011). However, when the focus is on choosing ‘the right’ places for lingering and play, the influence of culture and social interaction on the adaptation to the climate must be considered (Gehl Citation1971, Whyte Citation2001, Stevens Citation2007). For example, some regional cultures might prefer vibrant spaces with higher density of people, activities, and buildings; others might prefer less populated, or more natural and peaceful spaces in their daily lives (Knez and Thorsson Citation2008). Responding to different cultural demands, urban design can influence public open space users’ adaptive capacity. Urban comfort is a useful concept in this regard, as it combines cultural meanings – it considers regional identities and local cultures – lifestyle preferences, and strategies and technologies available to promote people’s adaptation.

Materials and methods

This study emerged from a wider research project that used empirical data obtained from semi-structured qualitative interviews (Tavares Citation2018, Tavares et al. Citation2019). The past study concluded that urban comfort is constituted by regional identity and local culture; urban lifestyle, liveability, and urbanity; and adaptation to urban microclimate. This study used a simplified methodology (), based on semi-structured interviews and an online survey with Aachen residents. While the online survey provided a wider range of responses and allowed for an exploration of what was happening, the semi-structured interviews were useful to understand participants’ feelings and reasoning, and why certain responses to climate happen as they do. Data was collected between July 2014 and February 2015.

Case study

With a population of around 250,000, Aachen is the westernmost city in Germany with boundaries that coincide with Belgium and the Netherlands. Located in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Aachen’s urbanization resulted from its thermal springs, known since the Roman times, and the Aachen Cathedral served as the coronation place of over 30 German kings from the Middle Ages to the Reformation (Esser Citation2011). The city’s urban form consists of the old inner town and the newer outer town and suburbs. Aachen is a prosperous city with education being an important local industry, with more than 58,000 students enrolled in two universities (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst Citation2021). Tourism is also an important sector of the local economy due to the city’s history (Encyclopedia Britannica Citation2020) and its location. In addition, the number of residents living in the medieval city centre is high compared to other German cities with classic Central Business Districts (CBDs).

Regarding climate change impacts, hot summer days are likely to have an increased frequency, resulting in a growing number of heatwave episodes (IPCC Citation2022). Aachen and its surroundings are considered exemplar of the average expected climate changes in Germany (Schneider et al. Citation2011). In addition, in the last 200 years, Aachen’s growth resulted in a reduction of green open space – parks, gardens, and agricultural areas – significantly decreasing the cold air catchment area. This has caused a decrease of wind positive effects such as a night cooling and improvement of air quality both in the oldest parts of the city centre and the newer ones (Esser Citation2011, Sachsen et al. Citation2013). A combination of poor air exchange due to the area’s natural geography and human activity, has generated urban heat islands. To counterbalance this issue, Aachen has numerous protected cold air corridors, which are aimed to remain as free as possible from new constructions, playing an important role on the urban climate (Stadt Aachen Citation2014).

Germany has a maritime warm and humid temperate mid-latitude climate – predominantly CfB according to Köppen-Geiger classification (Kottek et al. Citation2006) with a mean annual temperature of 9.7°C, which is high if compared to German mean temperature (Kaspar et al. Citation2023). Moreover, frosty days (minimum under 0°C) and ice days (maximum under 0°C) are rare. July is the warmest month, with a mean temperature of 17.3°C, which is low if compared to the country’s mean temperatures at the same month. As a result, cold or heat stress are rarer in Aachen than in other German cities (Havlik and Ketzler Citation2000). Predominant wind direction in Aachen is southwest, particularly when high-speed gales occur (Havlik and Ketzler Citation2000). Aachen has an annual rainfall of 828 mm, which is higher than the German average (764 mm). Heavy rain is more common during summer months. The city has a low average of sunshine hours (1552 hours per year) if compared to other German cities (Havlik and Ketzler Citation2000).

Methods

Semi-structured interviews

Using semi-structured interviews, we aimed to gather information on regional identity and local culture – how Aacheners see themselves – and how that may affect choices for places, including their relationship with the weather and microclimate. The interviews took from 40 minutes to one-and-a-half hours and were recorded and transcribed in their entirety. An interview guide was prepared, but the interviewees were allowed to talk freely, which provided an opportunity to bring up new ideas during the interview (Stefansdottir Citation2017).

The semi-structured interviews had three parts. The first part delt with the value of outdoor settings, preferred lifestyle and the importance of social activity when choosing places to be. Respondents were asked if they consider themselves urbanites or if they prefer to be in the countryside or outdoors, if the way people use urban spaces affect their choices and what lifestyle – urban or countryside – is more likely to be conducive to quality of life. The second part regarded their preferred places in the city. Respondents were asked to describe the place they were in, how frequently they use that area, how do they feel about urban density, and the importance of private gardens and backyards. They were also asked if the climatic qualities of that specific area had a role on their choice to be there. The third part regarded the urban microclimate and the respondents’ perceptions. They were asked to describe Aachen weather, how the weather influences their daily lives and if it impacts choices for clothing and means of transportation. Respondents were also asked to describe their thermal comfort conditions during the interview.

Participants were randomly selected, and interviews were pre-arranged and undertaken in person. However, they had to be over 18 years old, speak English, and be residents of Aachen for at least one year to ensure climate and weather experience and that they had developed a lifestyle in the city. In total, seven interviews were conducted (n = 7), of which two worked in professional urban design and planning capacities for the local government.

Semi-structured interviews were qualitatively analysed using the process of coding and memoing (Lofland et al. Citation2006, pp. 209-212). The qualitative thematic analysis was carried out using principles of inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) based on three main steps: (1) coding; (2) code filtering; and (3) emerging themes. In the coding stage (step 1), responses were read in detail, and emerging codes were identified and tagged using NVivo software. At the same time, a ‘memoing’ document was created (Lofland et al. Citation2006) with the description of all codes. Once all responses were coded, the codes were reassessed along with their memos and filtered (step 2) to avoid repetition and review the wording for consistency. The overarching themes could then be identified (step 3). These themes were not predetermined and emerged from the data. In reporting the results, interviewees were attributed a code – general Aachen residents were identified as ‘G’ followed by a number and professionals and government were coded ‘P’ followed by a number.

Online survey

This survey was written in German language and widely circulated widely through email and social media. The sample was not meant to be statistically representative, but to provide support for the interviews through a larger number of responses in a short period of time. Therefore, the survey was based upon the interview guide. The survey had 42 questions divided in the same three question groups, in the survey titled: value of outdoor settings, choice for urban areas, and adapting to Aachen’s weather and climate. The questions were yes/no questions, multi-choice, Likert scale rating. There were also three questions where respondents were asked to describe in three words: the Aachen weather, the place they were in, and their daily activities affected by the weather.

Regarding the psychometric properties of the survey, the questionnaire was based on the literature and the previous applied interview guide (Tavares Citation2018, Tavares et al. Citation2019). Questions and topics to optimize understanding and minimise bias were developed. As the survey aimed at understanding the relationships between local identity, lifestyle, and adaptation to the climate in Aachen, rather than developing a standardized instrument, no further internal consistency checks have been undertaken. Survey participants had to be over 18 years old and reside in Aachen for at least two years to be familiar with the weather pattens and to have developed adaptation strategies when needed. The online survey was made available from October 2014 to February 2015 and included 42 questions.

The survey received 72 responses and survey respondents were 35 women and 37 men, the majority (n = 35) between 21 and 30 years old, with a high number of respondents (n = 14) between 31 and 40 years old. Of the remaining respondents two were aged between 18 and 20 years old, and all others together (n = 21) were older than 41 years old. They grew up in an inner city (35), in the countryside (23) and in suburbia (14). Their background helps understand their past experiences and how that may influence their preferences for living in or out of the city.

Survey responses for the multiple-choice questions were analysed based on descriptive statistics and reported based on frequency (absolute numbers) and relative frequency (percentage). The open-ended questions were analysed similarly to the semi-structured interviews coding process, but in addition to the three steps of the semi-structured interviews’ analysis, a fourth step was introduced: for each question. These summaries report on the meanings of charts and numbers, particularly how the themes and codes relate to each other.

Regarding the reporting of the survey data, ‘mentions’ (absolute numbers) refer to the survey open-ended questions, which have been coded. Hence the ‘mentions’ refer to the number of times each code appears. Relative frequency (percentage) is used to indicate how many respondents chose specific multiple-choice answers.

Results

The data analysis focused on nine main topics discussed with respondents in the interviews. These were coded and classified into three larger emerging (overarching) themes: (1) Regional identity and local culture (2) Urban lifestyle, liveability and urbanity; (3) Adaptive strategies. Each of these overarching themes also had several key sub-themes within them ().

Table 1. Interview topics and emerging themes.

The next sections explore each of these key themes and sub-themes () through the results from semi-structured interviews and survey responses.

Regional identity and local culture

Regional identity and local culture refer to the social and physical landscapes and outdoor values and recreation. This study’s premise is that regional identity, influenced by the city’s location and its physical landscape – both natural and built – affects the resulting social and cultural landscapes. Regarding its physical landscape, within Germany, Aachen is the centre for a region, and it has strong relationships with neighbouring countries. Interview data shows the importance of the physical landscape.

There’s competition between the cities, good places to live for example in Aachen, Maastricht … Everyone wants to have good attractive city to get more jobs, but if the city is not attractive only the people that have no choice would stay here. (G3)

Because of its location and surroundings, Aachen’s forest areas are located at the edge of the valley basin, while the inner city where about 32,000 people live (Stadt Aachen Citation2022) has very few green spaces. In this context, while outdoor recreation is important and was manifested as a reason to choose a specific place to live, locals tend to consider themselves urbanitesFootnote1 and ‘don’t want to be like agricultural population, (…) they want to visit it, but not to be part of it (G2)’.

I am from the countryside, but I am living in an urban context, and I think I prefer the urban context if there’s contact with nature. (…) I miss water, a river, something like that, but if you want to be in nature, you can. (…) I think there has to be some kind of urban feeling, and for me it is important that it is not too big but also not too small. I think Aachen is perfect [and] (…) people and my workspace are the most important, but for the personal and individual it is also important to have some parks and to have some open spaces which are full of people and where you can meet people, (…) I think Aachen is nearly perfect. (G5)

Some respondents said they dislike gardening because find ‘difficult to keep a garden’ (G2), in addition, they do not miss it as ‘there is a park just outside [their] place’ (G2) or they have a ‘park near so [they] can walk in about 2-5 minutes’ (G5). Having a ‘balcony or a very small garden’ (G5) is also enough for some. In addition, the urban lifestyle is manifested in children’s lives, as parents with ‘children who are living in the city centre and have no cars and the children can play’ (G5), so a typical backyard is not needed. It is also important to note that, while nature is valued, the history and narrow streets of the built landscape has the strongest influence on daily lives. This is further explored in the next section discussion on urban lifestyle, liveability, and urbanity.

Results from the survey support the ideas described by interviewees. Survey respondents were from many different places: only 10 out of 72 respondents were originally from Aachen, while 55 were from other places in Germany and seven from other countries. Due to its border location and the university which attracts students from many countries, Aachen is a multi-cultural place, fact represented in the respondents’ demographics. Also aligned with the interview results, Aacheners like to live urban but visit nature, and 72% of respondents currently live in Aachen city centre. The remaining 28% live in suburbs around Aachen or neighbouring towns or cities.

Regarding the social landscape, besides its history, Aachen is a city of events and education. Its history and heritage are part of locals’ identities. Respondents said to like to be close to significant buildings and monuments, so they ‘feel part of it’ (G1). The events calendar influences the urban dynamics throughout the year. When there are events, ‘such as the Christmas Market, the city is full’ (G2). During these periods locals avoid the area as ‘a lot of tourists come to the city’ (G3), and change their routines:

Last year I wanted to pass through the Christmas Market. I thought I could pass, but I needed one hour to get from my work to the place I wanted to be. Normally it takes 10 or 12 minutes (…). You need to go to the Christmas Market in the morning to buy things, (…) and if you want to get the full atmosphere, you go in the evening when it is dark outside, but then you need time. (G4)

Besides that, Aachen is a university and education-based city:

Most of Aachen is related to the university. More than 20% of the population are students and 5-10% are directly working at the university. Everything is about the university and education and it is different from other cities (…) that are more industrial and service-based. Here there is a different kind of people, I like that. (…) Because of the university, 20% are around 20 years old, and that’s good. (G3)

Other things mentioned were the preference for emptier spaces, as despite being very touristic, Aachen is not a very busy place. Others said they like to be in the city and amongst people, as they consider it relaxing. Aachen’s central area has also been mentioned as a place to meet friends and join festivals and events, not a place to be alone.

Outdoor value and recreation are important and were manifested as a reason to choose a specific place to live:

(…) That little town where I grew up many people from Bochum would go every weekend, and I used to think ‘why would they come here’? It is boring and nothing happens, but now I understand. They search for green and quiet areas and just sit there and do nothing and spend the weekend there. I talked to [a friend and] she lived in Israel and she came here and thought everything was green even in the summer. (…) When you spend some weeks in the desert and you come back you just think that really everything is so green here, (…) so now I understand that it is very important. I did not know what makes it so comfortable around here, but it is the forests (…) and the vegetation, everything grows and it is not a desert. (G3)

The outdoor value was also manifested as urban phenomenon:

Sometimes yes [I miss gardens], because I like flowers (…). When my children were small, I used to have a vegetable garden, and I liked that, but since I am working all day, I am happy that I have no garden because I wouldn’t have the time to do all the work. (G4)

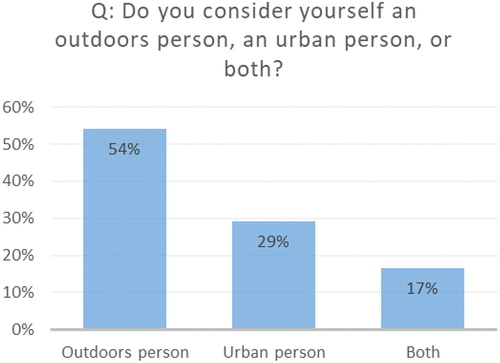

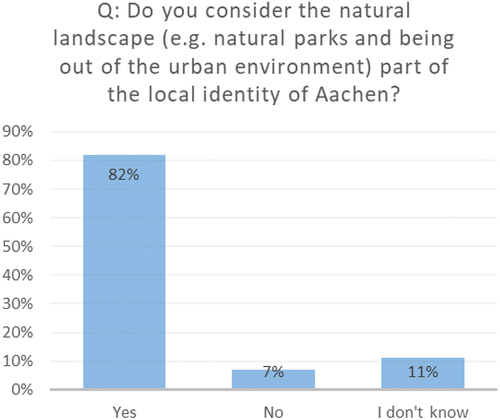

Even though Aacheners consider themselves urbanites regarding their identity, 54% of survey respondents consider themselves outdoor people (), urban parks are important for 100% of respondents, and only 8% said they do not use these spaces. 82% consider the natural landscape is part of the local identity ().

Liveability, urban lifestyle, and urbanity

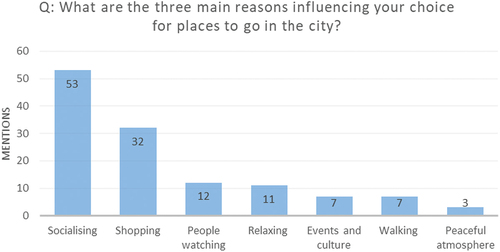

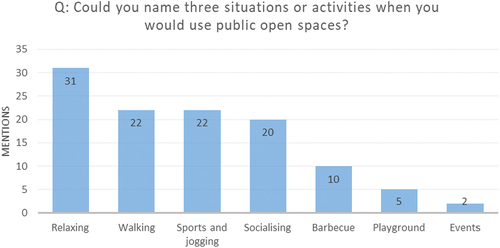

Liveability was described by respondents as related to meanings of urbanity and the urban lifestyle afforded by a compact city supported by high quality public open spaces and green areas. Compact city here refers to relatively high residential density combined with mixed-uses, in which walking, and cycling are encouraged due to the short distances. In this context, the main things influencing respondents’ choice for places in Aachen are spaces for socialising, shopping, people watching, relaxing, events and culture, and peaceful atmosphere (). In addition, the main recreational activities developed in public open spaces are relaxing, followed by walking, sports and jogging, socialising, barbecues, playground, and events ().

Figure 5. Reasons for choosing places in Aachen (Note: in this question each respondent could nominate up to three activities, hence the numbers higher than the total of 72 respondents).

Figure 6. Main recreational activities developed in Aachen’s public open spaces (Note: in this question each respondent could nominate up to three activities, hence the numbers higher than the total of 72 respondents).

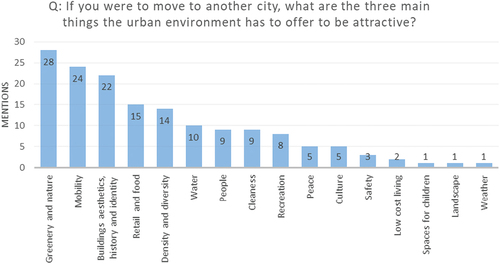

The survey also asked what respondents would look for in another city if they were to move away from Aachen. The most mentioned features were greenery and nature, followed by mobility, buildings aesthetics, history and identity, retail and food, density and diversity and other less frequently mentioned characteristics ().

Figure 7. Most desirable characteristics of the urban environment (Note: in this question each respondent could nominate up to three activities, hence the numbers higher than the total of 72 respondents).

While private gardens are considered important for 83% of respondents, 64% do not have a private garden, against 36% who do. In this context locals ‘like density in terms of buildings but also in terms of people (…) and if you want to be alone or in a quiet place you can find it in Aachen too’ (G5). When asked about Aachen’s level of urbanity, it has been considered ‘not really urban’ (G3) when compared to big cities:

You can walk through the centre in a few minutes, and you can take the bus and in a few minutes, you are in the woods or in the forest. (…) Sometimes urban is very good, but it is not necessarily to live there. If I want to have fun I can go to Cologne [which is] 1h drive, but if I want to have a bit quieter and nature around, I stay here. For living I think it is better to be in a city not bigger than Aachen. (G3)

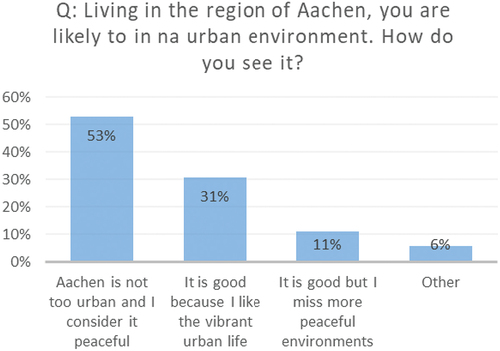

Results from the survey support this finding as 53% of respondents do not find Aachen too urban and they consider it peaceful despite the compact living arrangements ().

As Aachen is a compact city, apartment living is common. While a minority of respondents said they live outside the city, most respondents live in the city or in an inner suburb. With that comes the issues of privacy, therefore ‘it is very important that the walls absorb the main noise [so you] can close the door and have privacy’ (G2).

I was very afraid of not adapting to this kind of living. But now I am living in an apartment, [the building] has 85 units, but it is like a pyramid, and I am living very high, so I only have 2 neighbours. It is nice because sometimes I meet people in the elevator, and I like that. (G4)

Also, in this context of apartment living, the parks become even more important as they work as substitute for private gardens, for instance:

When people start sitting in the park again and (…) in the evening when everyone is doing barbecue there’s just blue smoke coming out of the park and settling in the street, so people don’t have their own garden, they use the parks to do what they’d do in a backyard. (G1)

Regarding liveability, important points were that work is close to home (G2), and that the city supports walkability through proximity to places and quality of streets:

I don’t need very much, I need some shops for the daily food, clothes, and all should be close enough. Supermarket should be within a few minutes walking distance. Other things I don’t need every week, so other shops could be in 30-minutes drive, that would be ok. I would not like to live in a town where there is nothing, only houses for living, so-called sleeping town where if you need anything (…) you must take the car, that’s not good. The most important things you should have very close. (G3)

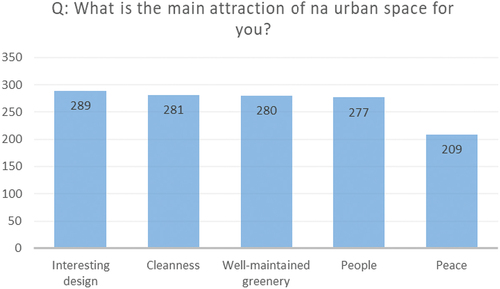

Survey respondents were asked to rank the most important aspects of urban places. shows that interesting design is considered by respondents the most important aspect of urban spaces, supporting the urbanite character of the local respondents. This aspect was followed by cleanness and well-maintained greenery.

Figure 9. Urban places main attraction (Note: in this question respondents ranked each one of the features of urban spaces from 1 to 5. The result shown on the graph is the numerical sum of all responses for each feature, hence the total numbers are higher than the total of 72 respondents).

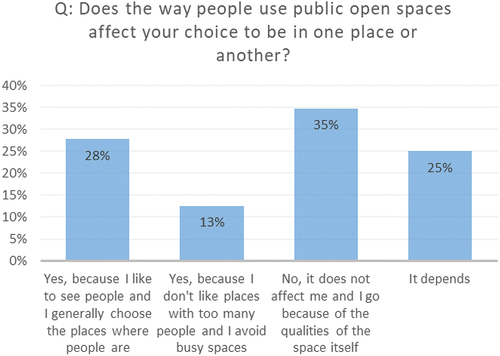

Though the presence of people was ranked as the most important feature of a space, survey respondents said their own choices are not affected by the way other people use public open spaces, and they go to places because of the space qualities themselves ().

Also, in the survey an open question allowed respondents to add aspects of public spaces they judged important, which were not on the list. Personal views were added by 18 respondents, and highlighting the importance of building diversity, comfortable spaces regarding weather and climate, recreation opportunities, security and transport, and outdoor seating.

Adaptive strategies

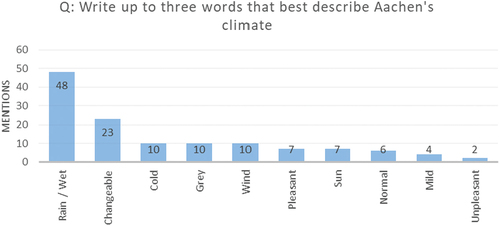

In the survey, respondents were asked to write up to three words that characterise Aachen weather. The most frequent mention was rainy/wet, followed by changeable, cold, grey, and windy, pleasant, and sunny, normal, mild, and unpleasant ().

The local weather and microclimate were frequently not a priority in the locals’ minds as it is considered predictable apart from the rain. However, 61% of survey respondents said they check the forecast, fact also illustrated by an interviewee:

A few minutes before I leave the house, I check the rain forecast radar, I see the clouds and the places where the rain comes from, so I just decide to take my bicycle and check the temperatures. I check the weather several times a day. (G3)

In addition, most survey respondents said they do not think about microclimate when choosing places to go in Aachen (74%), and they do not remember any place because of its good microclimate (58%). Interview respondents said that weather in the city does not matter much ‘as long as you have an umbrella’ (G1), and similarly to the survey responses, the general Aachen climate was described as unpredictable, changeable, strange, rainy, and predominantly wet and cold. Spaces are emptier in the winter and the weather is generally cloudy, grey, overcast, dark. Aachen is not a windy place and has no extremes, but defined seasons.

I think it is often rainy [and] not so windy. It is regular, it is not cold but also not hot. It is not always the same, but there’s not too much difference in this. I am from Germany so, it is just ‘normal’ weather if you can say this. (G5)

Besides being influenced by the shape of buildings and exposure to the wind and sun, locals’ relationship with nature is influenced by weather and seasons. It has been considered that, while ice can make it dangerous, ‘all other times this change in the weather and nature [is good]’ (G4). Locals said they prefer to go for ‘walk[s] in the fields than in the city [as] you can see weather and flowers changing. When you are in the city you don’t realise what time [of year] it is’ (G4)

Decisions about what to wear are also mainly influenced by rain. As most residents walk, they ‘dress to the weather because (…) if raining [they] don’t want to get wet while outside’ (G4). The ability to look outside, feel the weather and see what other people are wearing also influences personal decisions, for example, ‘temperature is more important for me (…). Also opening the window always helps. Sometimes it helps to look on what people on the street are wearing’ (G5).

Weather shapes life in some ways. It shapes what outdoors activities Aacheners choose to undertake in their private lives – i.e. ‘sports, biking, hiking, or swimming, therefore [they] do completely different things in the winter and in the summer’ (G3). During the summer, locals also use parks for barbecues, but overall, the choice to be in certain places depends on people, sun and wind.

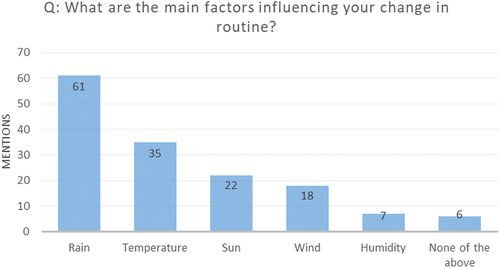

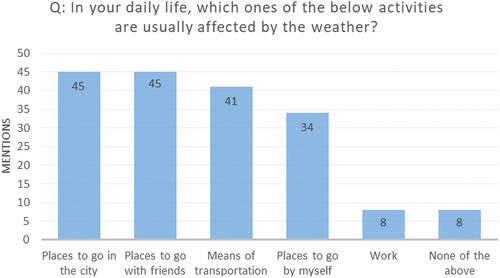

Survey responses show that most respondents do not change their routine due to the weather (53%). Activities mentioned as affected by the weather were: places to go in the city and places to go with friends (45 mentions each), followed by means of transportation, places to go alone, and work arrangements (). Main factors influencing these choices and changes are illustrated in .

Figure 12. Routine changes due to weather (Note: in this question respondents could choose all responses that applied to their circumstances. The result shown on the graph is the numerical sum of all responses for each response option, hence the total numbers are higher than the total of 72 respondents).

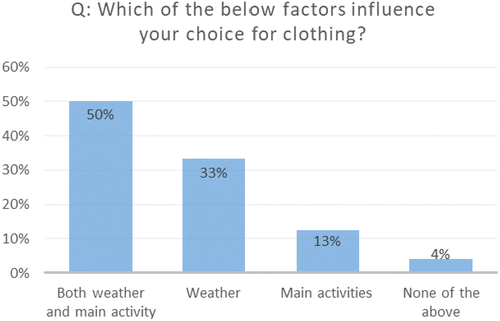

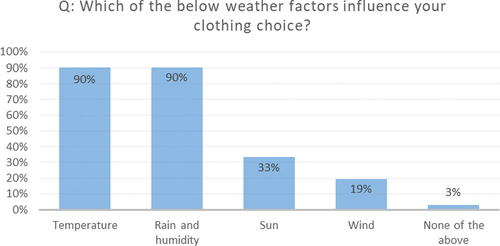

Regarding how Aacheners prepare for the weather, 50% said they choose clothes according to the weather and activities, the others only consider one of these variables (). The main things influencing the clothes respondents choose are illustrated in .

The ‘not so comfortable’ winter conditions seem to be balanced by events and festivals. Although locals ‘like summer [to] sit outside’ (G4), the special time in Aachen has frequently been mentioned as ‘the winter [as] there is the Christmas Market and that is nice to enjoy with friends’ (G4), ‘especially if snow is falling (…) and because the spaces are not so wide [as] there are little tents, you are more protected’ (G5). This demonstrates that culture and urban design impact on urban microclimate experience, and that the experience of urban climate – i.e. urban comfort – is a result of these factors combined.

In summary, the place-based aspects of the regional identity and local culture; liveability, urban lifestyle and urbanity; and adaptive strategies adopted in Aachen are presented in , and further explored in the discussion session.

Discussion

This work set out to investigate the relationships between socio-cultural and physical environments in Aachen that enhance urban comfort. The hypothesis is that even in sub-optimal urban microclimates design can promote adaptation by responding and accommodating activities that have cultural meaning. In the context of climate change and warmer temperatures, urban areas are expected to become warmer increasing the need for adaptation strategies and enhancing adaptive capacity (Hunt and Watkiss Citation2011). Culture and social habits quite clearly play a role on adaptive capacity through the way they shape people’s response to urban microclimate conditions (Eliasson et al. Citation2007, Thorsson et al. Citation2007, Kwong and Lam Citation2018, Tavares Citation2018, Tavares et al. Citation2019, Naheed and Shooshtarian Citation2021), and these, in turn, affect outdoor permanence contributing to social cohesion and local economies (Aljawabra and Nikolopoulou Citation2010).

This pilot investigation was designed as a compact and time-efficient way to explore urban comfort in Aachen as an example of a multi-cultural context. Similar to previous studies (Brychkov et al. Citation2018, Tavares et al. Citation2019), results show that cultural background plays a role in people’s thermal comfort and how they experience the weather. That is particularly related to regional identity and local culture – i.e. historical connections with the physical landscape (Christchurch) or the history associated with city life (Aachen).

Aspects that help shape how Aacheners see themselves and their regional identity are the local culture, the physical landscape, along with the influence of visitors from surrounding countries, the importance of the built environment and history, and the value put on nature through urban parks, forests, and hills. It was observed that even people who see themselves as ‘from the countryside’ have a strong connection with the city. This finding highlights differences in the opportunities of promoting adaptive capacity when compared to results from previous studies undertaken in New Zealand (Tavares et al. Citation2019) in the sense that urbanity, city history and city life, play an important role in local’s identity. It therefore supports previous studies which have found out that culture plays a role in thermal perception (Knez and Thorsson Citation2008, Lin et al. Citation2011, Aljawabra and Nikolopoulou Citation2018, Brychkov et al. Citation2018, Lyu et al. Citation2023), and adds an exploration of some of these cultural characteristics that make up a unique local identity. As Taylor (Citation2023) highlights, regional identity is related to the uniqueness of places, and Aachen’s history and compact city fabric shaped by the former medieval walls play an important role in the local identities. But Aachen is also a multi-cultural city; hence it is not always possible to define what is purely local and what is influenced by neighbouring cities or by the habits of immigrants. In this sense, the social landscape that constitute Aachen’s regional identity and local culture is also influenced by the city’s history, events such as the Christmas Market, education institutions, tourism and the values placed on outdoors and recreation.

Aachen’s central city is not a CBD, but a place where a large part of the population lives, emphasising an urban lifestyle and enhancing the levels of urbanity (Castello Citation2010, Wesener Citation2018). It also offers plenty of opportunity for encounters and socialising, associated with urban density, apartment living, and the use public open space as a substitute for private gardens. This highlights that ‘collective’ understanding of liveability relates to urbanity ‘as an urban way of life’ (Wesener (Citation2018) and translated into a compact city form, the ability to walk and cycle rather than relying on private cars, and proximity to work is an important feature in enabling active mobility, indicating adaptive capacity strategies. This is different from what has been identified in previous studies of urban comfort, where the outdoor landscape and peacefulness was a main identity feature and preference (Tavares Citation2018, Tavares et al. Citation2019). In Aachen, the design of public spaces was considered the most important aspect of urban areas, followed by cleanness and greenery to support and ensure liveability. Even though the presence of people was not one of prioritised aspects of urban spaces, it was still more important than ‘peaceful spaces’ - again, supporting Aachen’s urban character, highlighting the importance of planning and designing for urbanity.

Aachen was described as not a windy city, but important places are avoided because of wind, influencing people’s adaptive capacity (Givoni et al. Citation2003, Stathopoulos et al. Citation2004, Reiter Citation2010). The local climate was described as mild, changeable and a ‘normal German weather’ and the main required adaptation to urban microclimate is due to the frequent rain. Aachen’s climate sits outside of the comfort zone during long winters, but despite those characteristics locals enjoy urban life highlighting the role of ‘people as the main attractors’ to urban spaces as Gehl and Rogers (Citation2010) have pointed out and their consequent role on thermal perception. The role of street life here – related to density and urbanity – is in evidence when locals highlight that it is necessary to be able to ‘open the window and see people’ to then make an informed decision on what to wear or where to go. In addition, versatile places are important as they make possible to use indoor areas if it rains and outdoor ones if the sun is out. These are important notions to be considered in attempting to enhance adaptive strategies to microclimate, as when compared to the previous studies on urban comfort, the role of cultural differences becomes clear, supporting Knez and Thorsson (Citation2008).

Strategies adopted to adapt to the local microclimate include means of transportation, as cycling can be difficult at times; choices for clothes, largely regarding the rain and season-based change in weather conditions, and having or not company, as public spaces are usually used when with friends. This implies that citizens may be more willing to accept sub-optimal conditions when in the presence of friends, as explained by Givoni (Citation2003), Gehl (Citation1971), and Stevens (Citation2007). Due to cultural and social interaction influences, providing opportunities for social encounters is also important in the context of adaptation to urban climate. The provision of urbanity can enhance local liveability levels and the capacity to adapt to urban climate.

Local culture informs the types of spaces that cities offer. In Christchurch, for example, regional identity is largely connected to the physical landscape and the activities undertaken in that landscape. This informs the expected level of urbanity, which prioritises peaceful and low-density environments, shaped around the ‘Garden City way of living’ with the need for meeting people and escaping from crowds in urban spaces. In Aachen, on the other hand, the compact city is favoured. Urbanity, walking to places, and seeing people takes priority. The urban spaces, the history and connections to the past, or ‘being part of it’ are part of the local culture and influence people’s willingness to adapt to sub-optimal microclimatic conditions.

The expected levels of urbanity in Christchurch lead to adaptive strategies that create viable urban spaces that often serve as retreat spaces, where locals can be in the city and see people without necessarily participating in social activities. In turn, public spaces in Aachen are considered as more active social spaces. Urban comfort in Aachen is influenced by local culture – the level of urbanity expressed in the value of history, city-wide events, education, and the multi-cultural aspects of city-life with a value placed in nature; liveability in regard to preferred ways of urban living is expressed in compact and walkable urban areas, with high quality urban spaces and public green areas; and adaptive capacity is influenced by modes of transport – frequently cycling – dressing for the weather (mainly the rain) and social environment, including company.

Conclusions

The paper argues that urban comfort (regional identity and local culture; urban lifestyle, liveability and urbanity; and adaptive strategies to the local microclimate) in Aachen is influenced by a combination of factors including the physical and social landscapes, a compact urban form which enables an urban way of living with plenty of opportunities for socialising, proximity between work and home, public green areas, building design and diversity. The adopted adaptive strategies are influenced by these factors and reflected in the choice for means of transportation (cycling, taking public transport and so forth) to adapt in rainy days, wear appropriate clothes to keep dry when raining and make sure they are warm to be able to enjoy the public open spaces, particularly when it is cold and the city is ‘alive’ due to traditional events such as the Christmas market. In these situations, the city was said to feel warmer despite the cold weather.

This study adds a multi-cultural dimension to the study of urban comfort. Human comfort in urban environments depends on adaptive capacity and strategies, which depend on culture. Our study confirmed previous research findings about the role of cultural background and past experiences on people’s tolerance of urban climate conditions and added new findings concerning the aspects that shape those responses. Results of this study demonstrate aspects of the design requirements of outdoor public spaces that should be considered from the perspectives of culture adaptation microclimate. In practice, meanings of weather and climate (Strauss and Orlove Citation2003) should inform urban design practices and use the potential of microclimatic design to enhance liveability in the city. There is a need to consider ways of influencing microclimate perception, and in Aachen the connection with history and the compact city living are central to this adaptation. In this regard, the concept of urban comfort can be operationalised to help address sustainability and climate change adaptation of urban public spaces by enabling adaptation through the provision of spaces that particular cultures expect and prioritise in the urban environment – for example, retreat or social – enhancing public space use, social cohesion, connection to place, and local economies.

We also added a new perspective by adding a discussion around urbanity and its role on adaptation to urban climate, in comparison to places where nature and outdoors life are more at the centre. The current predictions for a changing climate also add an extra layer of challenges facing urban environments, especially regarding how cultures will adapt to new scenarios, and values, symbols and meanings that can potentially be lost. Understanding these dimensions of climate adaptation can contribute to the design of more resilient and sustainable cities.

A limitation of this study regards participants recruitment. Participants were randomly selected, and interviews were pre-arranged and undertaken in person. However, interviewees had to be over 18 years old, speak English – as the interviews were carried out in English – and be residents of Aachen for at least one year to ensure climate and weather experience, and that they had developed their lifestyle in the city. This limited the potential number of participants. Regardless of this limitation, our study provides a direction on some of the key cultural aspects influencing adaptation to urban climates and, as researchers have previously pointed out, understanding these perceptions and the role they play in place-based adaptation opportunities and people’s willingness to adapt is fundamental in the context of climate change (Taylor Citation2023) and to achieve urban sustainability (Erell Citation2008). Therefore, we believe this study can serve as a basis for future studies focused on additional case studies that explore different climatic zones (such as tropical zones) and use diverse research methodologies that help to organise complexity. The complexity of urban comfort could be explored in various contexts, and different scenarios could be tested to achieve the best possible outcome through an understanding of the relationships between urban microclimates, concepts of liveability, and local cultures, and to inform appropriate allocation of land uses according to local requirements to support and improve the adaptive capacity to urban climate (and climate change).

Finally, although in this study the factors influencing urban comfort – regional identity and local culture, liveability and urbanity, and adaptive strategies to the local climate – are separately categorised, there is no definite boundary between these factors. This is because of the complexity of sociocultural systems and relationships involved in urban life that can influence responses to local weather – adaptation strategies – as a factor of local cultures. Thus, we suggest further research must be developed to clarify the boundaries or better represent the relationships between the factors in this system.

Acknowledgements

Human research ethics approval for this project has been granted by the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). The ethics approval number for the project is A221721. Ethics approval indicates that this project meets the requirements of Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council’s (NHMRC) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). The interview guide, the online survey, and all other supporting documents have been approved by HREC.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Silvia G. Tavares

Silvia G. Tavares is an urban designer with a background in architecture, urbanism, and building and city science. She is the founder and co-leader of UniSC’s Bioclimatic and Sociotechnical Cities Lab (BASC Lab) and chief investigator in several projects focused on improving urban climate through design and planning. These projects aim to inform strategies related to human thermal comfort, green infrastructure, public health, and climate change impacts. Before UniSC, she worked at James Cook University in Australia, Lincoln University in New Zealand, the Research Institute for Regional and Urban Development in Germany, and at the Universidade Federal do Tocantins in Brazil.

Andreas Wesener

Andreas Wesener is a Senior Lecturer in Urban Design and Head of the School of Landscape Architecture at Lincoln University, New Zealand. He studied architecture in Bochum and London and was awarded his doctorate from the Bauhaus-Universität in Weimar (Germany). Wesener’s research explores approaches for more sustainable and resilient cities. He investigates processes, structures and meanings that characterize urban environments in times of transition including experiences of urban space and place, post-disaster urbanism, bottom-up governance, integrated (green-grey) urban infrastructure, and urban agriculture with a particular interest in urban community gardens.

Runrid Fox-Kämper

Runrid Fox-Kämper is a Deputy Head of Research Group Spatial Planning and Urban Design at ILS Institut für Lands-und Stadtentwicklungsforschung in Dortmund, Germany and Senior Research Manager at ILS Research gGmbH, a subsidiary non-university institute of ILS. She studied Architecture and Urban Planning at the RWTH Aachen. She focuses her research on the role of climate protection and adaptation in urban development, urban agriculture and urban food planning.

Lisandra Krebs

Lisandra Krebs is a Tenured Lecturer (US Assistant Professor) at the Urbanism Lab of the Federal University of Pelotas, Brazil. She is an Architect with a Ph.D. in Engineering (Lund University, Sweden) and a Doctor Degree in Architecture (the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil). Dr. Lisandra has experience in sustainable projects, and her main interests are urban microclimate and its relation to healthy cities and indoor thermal comfort.

Notes

1. Urbanites are conceptualized in this study simply as people living in cities.

References

- Aljawabra, F. and Nikolopoulou, M., 2010. Influence of hot arid climate on the use of outdoor urban spaces and thermal comfort: do cultural and social backgrounds matter? Intelligent buildings international, 2 (3), 198–217.

- Aljawabra, F. and Nikolopoulou, M., 2018. Thermal comfort in urban spaces: a cross-cultural study in the hot arid climate. International journal of biometeorology, 62 (10), 1901–1909. doi:10.1007/s00484-018-1592-5.

- ASHRAE, 2001. Fundamentals handbook. New York, US: ASHRAE.

- Barnett, J., et al., 2021. Three ways social identity shapes climate change adaptation. Environmental research letters, 16 (12), 124029. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac36f7.

- Bedi, C., Kansal, A., and Mukheibir, P., 2023. A conceptual framework for the assessment of and the transition to liveable, sustainable and equitable cities. Environmental science and policy, 140 (January 2022), 134–145. Elsevier Ltd: doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2022.11.018.

- Boone, C.G., et al., 2014. Reconceptualizing land for sustainable urbanity. In: K. Seto and A. Reenberg, eds. Rethinking global land use in an Urban Era. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 313–330.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brychkov, D., Garb, Y., and Pearlmutter, D., 2018. The influence of climatocultural background on outdoor thermal perception. International journal of biometeorology, 62 (10), 1873–1886. doi:10.1007/s00484-018-1590-7.

- Castello, L., 2010. Perception of place: rethinking the concepts of place in architecture-urbanism. Farnham, Surrey, GBR: Ashgate Publishing Group.

- Chatzidimitriou, A. and Yannas, S., 2015. Microclimate development in open urban spaces: the influence of form and materials. Energy and buildings, 108 (October), 156–174. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.08.048.

- Del Casino, V.J. and Thien, D., 2020. Symbolic Interactionism. In: R. Kitchin and N. Thrift eds. International encyclopedia of human geography. Elsevier, 177–181. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10716-4.

- Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, 2021. Aachen: regal education in the heart of Europe. Available from: https://www.study-in-germany.de/en/discover-germany/german-cities/aachen_26953.php [Accessed 10 March 2021].

- Dovey, K., 2010. Becoming places: Urbanism/Architecture/Identity/power. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Dovey, K., Pike, L., and Woodcock, I., 2016. Incremental urban intensification: transit-oriented Re-development of small-lot corridors. Urban policy & research, 1146 (3), 261–274. Routledge: doi:10.1080/08111146.2016.1252324.

- Eliasson, I., et al., 2007. Climate and behaviour in a Nordic city. Landscape and urban planning, 82 (1–2), 72–84. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.01.020.

- Elnabawi, M.H. and Hamza, N., 2020. Behavioural perspectives of outdoor thermal comfort in urban areas: a critical review. Atmosphere, 11 (1), 1–23. doi:10.3390/atmos11010051.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 2020. Aachen. Available from: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/200/Aachen.

- Erell, E., 2008. The application of urban climate research in the design of cities. Advances in building energy research, 2 (1), 95–121. doi:10.3763/aber.2008.0204.

- Erell, E., Pearlmutter, D., and Williamson, T., 2011. Urban microclimate: designing the spaces between buildings. Oxford, UK: Earthscan.

- Esser, K., 2011. City weathers in Aachen during the 1800s. In: M. Hebbert, V. Jankovic, and B. Webb, eds. City weathers: meteorology and urban design 1950-2010. Manchester, England: Manchester Architecture Research Centre, University of Manchester, 99–103.

- Fanger, P.O., 1973. Assessment of man’s thermal comfort in practice. British journal of industrial medicine, 30 (4), 313–324. doi:10.1136/oem.30.4.313.

- Fine, G.A., 2007. Authors of the storm: meteorologists and the culture of prediction. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

- Gehl, J., 1971. Life between buildings: using public space. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Gehl, J. and Rogers, R., 2010. Cities for people. Washington, DC, USA: Island Press.

- Givoni, B., et al., 2003. Outdoor comfort research issues. Energy and buildings, 35 (1), 77–86. doi:10.1016/S0378-7788(02)00082-8.

- Havlik, D. and Ketzler, G., 2000. Gesamtstädtisches Klimagutachten Aachen. Aachen, Germany. Available from: http://www.klimageo.rwth-aachen.de/wtst/Stadtklimagutachten_Aachen.pdf.

- He, X., et al., 2020. Cross-cultural differences in thermal comfort in campus open spaces: a longitudinal field survey in China’s cold region. Building and environment, 172 (January), 106739. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106739.

- Hebbert, M. and Webb, B., 2012. Towards a liveable urban climate - lessons from Stuttgart. In: C. Gossop and S. Nan, eds. Liveable cities: urbanising world: iSOCARP review 07. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 132–150.

- Höppe, P., 1999. The physiological equivalent temperature – a universal index for the biometeorological assessment of the thermal environment. International journal of biometeorology, 43 (2), 71–75. Springer-Verlag: doi:10.1007/s004840050118.

- Hunt, A. and Watkiss, P., 2011. Climate change impacts and adaptation in cities: a review of the literature. Climatic change, 104 (1), 13–49. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9975-6.

- IPCC, 2022. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. The working group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernamental Panel on climate change. Edited by H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, M. Tignor, et al. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. Available from: https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf.

- Kaspar, F., Friedrich, K., and Imbery, F., 2023. Observed temperature trends in Germany: current status and communication tools. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 32 (4), 279–291. doi:10.1127/metz/2023/1150.

- Kim, J., et al., 2022. The effect of extremely low sky view factor on land surface temperatures in urban residential areas. Sustainable cities and society, 80 (February), 103799. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2022.103799.

- Klemm, W., et al., 2015. Psychological and physical impact of urban green spaces on outdoor thermal comfort during summertime in the Netherlands. Building and environment, 83 (April), 120–128. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.05.013.

- Knez, I. and Thorsson, S., 2008. Thermal, emotional and perceptual evaluations of a park: Cross-cultural and environmental attitudes comparisons. Buildings and environment, 43 (9), 1483–1490. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.08.002.

- Kottek, M., et al., 2006. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 15 (3), 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- Kwong, C., et al., 2021. Interactive effect between long-term and short-term thermal history on outdoor thermal comfort: comparison between Guangzhou, Zhuhai and Melbourne. Science of the total environment, 760, 144141. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144141.

- Kwong, C. and Lam, C., 2018. Visitors’perception of thermal comfort during extreme heat events at the royal botanic garden Melbourne. International journal of biometeorology, 62 (1), 97–112. doi:10.1007/s00484-015-1125-4.

- Latham, A., 2003. Urbanity, lifestyle and making sense of the new urban cultural economy: notes from Auckland, New Zealand. Urban Studies, 40 (9), 1699–1724. doi:10.1080/0042098032000106564.

- Leby, J.L. and Hashim, A.H., 2010. Liveability dimensions and attributes: their relative importance in the eyes of neighbourhood residents. Journal of construction in developing countries, 15 (1), 67–91.

- Lenzholzer, S., Klemm, W., and Vasilikou, C., 2018. Qualitative methods to explore thermal-spatial perception in urban spaces. Urban climate, 23, 231–249. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2016.10.003.

- Lévy, J., 1997. La mesure de l’urbanité. Paris, France: Urbanisme.

- Lilius, J., 2021. ‘Mentally, we’re rather country people’ - planssplaining the quest for urbanity in Helsinki, Finland. International planning studies, 26 (1), 70–80. Taylor & Francis: doi:10.1080/13563475.2019.1701425.

- Lin, T.P., De Dear, R., and Hwang, R.L., 2011. Effect of thermal adaptation on seasonal outdoor thermal comfort. International journal of climatology, 31 (2), 302–312. doi:10.1002/joc.2120.

- Lofland, J., et al., 2006. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Belmont, USA: Wadsworth.

- Lowe, M., et al., 2015. Planning healthy, liveable and sustainable cities: how can indicators inform policy? Urban policy and research, 33 (2), 131–144. doi:10.1080/08111146.2014.1002606.

- Lowe, M., et al., 2022. City planning policies to support health and sustainability: an international comparison of policy indicators for 25 cities. The Lancet global health, 10 (6), e882–e894. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00069-9.

- Lyu, K., et al., 2023. A socio-cultural perspective to semi-outdoor thermal experience and restorative benefits – comparison between Chinese and Australian cultural groups. Building and environment, 243 (May), 110622. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110622.

- Masterson, V.A., et al., 2017. The contribution of sense of place to social-ecological systems research: a review and research agenda. Ecology and society, 22 (1). doi:10.5751/ES-08872-220149.

- Montgomery, J., 1998. Making a city: urbanity, vitality and urban design. Journal of urban design, 3 (1), 93–116. Routledge. doi:10.1080/13574809808724418.

- Naheed, S. and Shooshtarian, S., 2021. A review of cultural background and thermal perceptions in urban environments. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13 (16), 1–15. doi:10.3390/su13169080.

- Paasi, A., 2012. Regional planning and the mobilization of ‘regional identity’: from bounded spaces to relational complexity. Regional studies, 47 (8), 1206–1219. Routledge: doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.661410.

- Reiter, S., 2010. Assessing wind comfort in urban planning. Environment and planning B: planning and design, 37 (5), 857–873. doi:10.1068/b35154.

- Sachsen, T., et al., 2013. Past and future evolution of night time urban cooling by suburban cold air drainage in Aachen. DIE ERDE - Journal of the geographical society of Berlin, 144 (3–4), 274–289.

- Schneider, C., et al., 2011. ”CITY 2020+”: assessing climate change impacts for the city of Aachen related to demographic change and health – a progress report. Advances in science and research, 6 (1), 261–270. Aachen, Germany. doi:10.5194/asr-6-261-2011.

- Schneider, C., Achilles, B., and Merbitz, H., 2014. Urbanity and urbanization: an interdisciplinary review combining cultural and physical approaches. Land, 3 (1), 105–130. doi:10.3390/land3010105.

- Shi, X., et al., 2019. Effects of thermally modified asphalt concrete on pavement temperature. International journal of pavement engineering, 20 (6), 669–681. doi:10.1080/10298436.2017.1326234.

- Stadt Aachen, 2014. Klimakonzept für den Aachener Talkessel. Available from: http://www.aachen.de/DE/stadt_buerger/umwelt/luft-stadtklima/klimakonzept_ac_talkessel/index.html.

- Stadt Aachen, 2022. Fachbereich 02/200 Statistik. Aachen, Germany.

- Stathopoulos, T., Wu, H., and Zacharias, J., 2004. Outdoor human comfort in an urban climate. Building and environment, 39 (3), 297–305. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2003.09.001.

- Stefansdottir, H., 2017. The role of urban atmosphere for non-work activity locations. Journal of urban design, 23 (3), 1–17. doi:10.1080/13574809.2017.1383150.

- Stevens, Q., 2007. The ludic city: exploring the potential of public spaces. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Strauss, S. and Orlove, B., eds, 2003. Weather, climate, culture. 1st ed. New York, NY, USA: Berg Publishers. Available from: http://site.ebrary.com/lib/lincoln/docDetail.action?docID=10060552.

- Tavares, S.G., 2018. Public microclimates: thermal outdoor expectations in Post-Earthquake Christchurch (New Zealand). In: S. Roesler and M. Kobi, eds. The urban microclimate as artifact: towards an architectural theory of thermal diversity. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser, 82–100.

- Tavares, S.G., Swaffield, S., and Stewart, E.J., 2019. A case-based methodology for investigating urban comfort through interpretive research and microclimate analysis in post-earthquake Christchurch, New Zealand. Environment and planning B: urban analytics and city science, 46 (4), 731–750. doi:10.1177/2399808317725318.

- Taylor, P.J., 2023. The geographical ontology challenge in attending to anthropogenic climate change: regional geography revisited. Tijdschrift voor Economische en sociale geografie, 114 (2), 63–70. doi:10.1111/tesg.12540.

- Teshnehdel, S., et al., 2020. Effect of tree cover and tree species on microclimate and pedestrian comfort in a residential district in Iran. Building and environment, 178 (April), 106899. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106899.

- Thorsson, S., et al., 2007. Thermal comfort and outdoor activity in Japanese urban public places. Environment and behavior, 39 (5), 660–684. doi:10.1177/0013916506294937.

- Van Diepen, A.M.L. and Musterd, S., 2009. Lifestyles and the city: connecting daily life to urbanity. Journal of housing and the built environment, 24 (3), 331–345. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9150-4.

- Verbrugge, L., et al., 2019. Integrating sense of place in planning and management of multifunctional river landscapes: experiences from five European case studies. Sustainability science, 14 (3), 669–680. Springer Japan. doi:10.1007/s11625-019-00686-9.

- Wesener, A., 2018. How to contribute to urbanity when the city centre is gone: a design-directed exploration of temporary public open space and related notions of urbanity in a post-disaster urban environment. Urban design international, 23 (3), 165–181. : doi:10.1057/s41289-017-0053-9.

- Whyte, W.H., 2001. The social life of small urban spaces. New York, NY, USA: Project for Public Spaces Incorporated.