ABSTRACT

The way in which the living environment is designed has profound influences on inhabitants’ well-being; unfortunately, the search for leverage points for the socio-spatial assemblages of human wellbeing and the (re)configuration of their living environment is messy. This paper investigates how the project development of Wapping Wharf in Bristol impacted the dwellers’ well-being in emotional, physiological, and social aspects and to what extent they shaped their living environment. It affirms the significances of some contributors to human wellbeing enhancement in urban placemaking including greenspaces, walkability, and healthy eating, etc. Upon confirming the profound impacts of urban placemaking on dwellers’ wellbeing, the paper points out the relationship between urban placemaking and dwellers’ wellbeing is not just constitutive as suggested in existing literature review, but also mutually reinforcing. While previous research on the assemblage of placemaking and wellbeing has largely focused the former (placemaking), the future assemblage work should extend to the later (dweller wellbeing). In particular, sincere communications between the producers and the users of urban places are proved to help better placemaking and resident wellbeing enhancement; the paper thus suggests that any factors that can or have the potential to facilitate sincere communications should be prioritized in post-pandemic placemaking.

Introduction

The way in which the living environment is designed has profound influences on inhabitants’ well-being (Barton et al. Citation2015); this was widely acknowledged over two decades ago (Amin et al. Citation2000). Unfortunately, how exactly new developments should be designed to deliver positive impacts on dwellers’ wellbeing remains unclear (Ng Citation2016); and the search for leverage points for the socio-spatial assemblages of human wellbeing and the configuration of their living environment is still messy (Richardson et al. Citation2020). This is happening against the backdrop of the COVID-19 Pandemic, which has exerted more stress on human wellbeing (Kelsey and Chiara Citation2021), stimulating greater discussions on how to reframe planning practice to accommodate this assemblage.

This paper joins this discussion using a case study approach to investigate how the project development of Wapping Wharf in Bristol, United Kingdom, has impacted the dwellers’ well-being and to what extent their actions altered the living environment, aiming to provoke more thoughts on how new development should be designed to enhance wellbeing in post-pandemic planning. Qualitative research methods of interviews, site observation and further literature review are employed in this paper to achieve the research aim. The details of the methodology will be provided in the Methodology session.

Literature review

Health is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity but also a sense of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing (United Nations Citation1968). Human wellbeing comprises individual’s positive functioning of feelings, including emotional well-being related to feelings such as good spirits, happiness and life satisfaction; psychological well-being including self-acceptance, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery, autonomy; and social well-being e.g. social acceptance, actualization, contribution, coherence, integration, etc. (Keyes Citation2003, p. 299). The sustainability of human wellbeing as a whole is the capability to live well or achieve a good life within environmental limits (Burningham and Venn Citation2022). Whether an individual can live well or achieve a good life is deeply intertwined with their social and physical environments (Jackson Citation2017); in other words, how the urban places are made will have significant for the sustainability of dwellers’ wellbeing.

Numerous research has confirmed the profound impacts of (re)configuration of the built environment on human well-being in emotional, psychological and social aspects (Dannenberg et al. Citation2011, Barton et al. Citation2015). People are simultaneously natural, social and intellectual beings and have a constitutive relationship with places that they live in (Sack Citation1993, p. 329); healthy placemaking can shape human behaviours and enable human flourishing through the provision of natural, social or intellectual stimulus (Amin et al. Citation2000). It provides inhabitants access to constant contact with nature, minimizes stress and mental fatigue, enhances attention with aesthetical pleasure, creates platforms to sharing, learning and developing abilities to tackle difficulties, ultimately contributing to emotional wellbeing (e.g. self-acceptance), physiological wellbeing (e.g. better personal growth), and social wellbeing (e.g. integration, contribution) (Amin et al. Citation2000). On the opposite, the poor (re)configuration of urban settlements could cause chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart and lung diseases, cancer and depression, etc. (Ng Citation2016), deteriorating health status and preventing the positive functioning of wellbeing. Acknowledging the significance of urban placemaking on human wellbeing, many scholars have moved to the question of what to be addressed in the (re)configurating of the built environment in order to improve the state of human wellbeing.

A wealth of research sheds lights on the factor of greenspace, claiming that greenspace could enhance individuals’ good spirits, happiness and quality of life by alleviating urban heating and flood risks as well as nurturing natural habitats (Wolfram and Frantzeskaki Citation2016), and deliver aesthetical pleasure and help increase resilience against stressful life events (Russell et al. Citation2013, Zhang et al. Citation2015, Fretwell and Greig Citation2019). An international review of 263 relevant studies noted that 70% of articles reported a positive association between greenspace and human wellbeing (Wendelboe-Nelson et al. Citation2019). Dobson et al. (Citation2019) reviewed related 385 papers and found that visits to greeneries help reduce obesity, diabetes and heart disease and support social integration and community engagement. With these benefits of greenspace on human wellbeing, a growing proportion of urban populations show strong desires for urban wilds-capes (Jorgensen and Keenan Citation2012, Koninx Citation2019, Sandom et al. Citation2019); and unsurprisingly a dose of nature as a healthcare intervention has taken root (Shanahan et al. Citation2016, Cox et al. Citation2018).

It is widely acknowledged that the number of vehicles on the road impacts the levels of air and noise pollution, and consequently human well-being (European Environment Agency Citation2017). The access to daily facilities including affordable, healthy food and places to socialise within walking proximity will reduce car-use dependency; developing walkable neighbourhoods is thus an intervention to reduce dwellers’ car-use dependency to lower air and noise pollution exposure (Nicholas et al. Citation2017). In addition, walkable neighbourhoods, with the design of non-motored interconnected pedestrian and cycling paths are proved to be able to encourage more physical activities and inversely associated with obesity and diabetes (Hajna et al. Citation2015, Sallis et al. Citation2016).

Walkable neighbourhoods with diversified housing types, interconnected and non-motorized paths and plenty of common spaces will create opportunities for people to meet, chat, play, and learn, generating sense of belonging to that place. ‘People living in more walkable neighbourhoods tend to report a greater sense of community and stronger social networks’ (Centre for Active Design Citation2018, p. 22). Walking within the neighbourhood will enhance the sense of connection to the wider community (Kuboshima and McIntosh Citation2023). They further advocated that the physical environment must be considered at all scales from the interior layout to the outdoor common places to support good social connectedness. While the interior layout design such as big windows and balcony will enhance the sense of integration with the outside, the provision of a variety of forms and scales of communal spaces for accommodating individuals’ social relationships is widely recommended (Nordin et al. Citation2017).

The sense of belonging could then encourage dwellers’ participation of community organizations and group activities, potentially easing individuals’ stress and anxiousty (Carver et al. Citation2018), and helping them discover their purpose in life, acquire skills to master the environment, and secure autonomy in life (Beery et al. Citation2015, Ng Citation2016, Scannell and Gifford Citation2017, Lai et al. Citation2020, Subiza-P´erez et al. Citation2020). Frostick et al. (Citation2017) investigated 20 deprived neighbourhoods of London and found that thriving communities could enhance individuals’ wellbeing in aspects of stress reduction, pain relief and even longevity. Indeed, it was only in communities with positive functioning souls that active engagement and self-management of places by civil society are possible (Friedmann Citation1998).

Some researchers however point out that the safety concern in walkable neighbourhoods might potentially interrupt inhabitants’ social interactions. Though crimes may be an acceptable trade-off for living in their chosen vibrant and walkable community (Foster et al. Citation2016), with the fear of crime some might be reluctant to leave their houses or engage in social activities, leading to loneliness and isolation and reducing physical activities around greenspace areas (Richardson et al. Citation2020). In this regard, the way how greenspaces are designed is crucial for encouraging outdoor activities (Hipp et al. Citation2014, Kimpton et al. Citation2017).

While many studies are conducted on what to do for the better assemblage of urban placemaking and wellbeing enhancement, some look at what to be avoided, for instance, high-rise building design. ‘It is very important that the building, which includes many functions and services, does not become an unassailable fortress’ (Generalova et al. Citation2018, p. 4). Nichols and Del Casino (Citation2021) found that high-rise building design is largely a result of limited floor space in the urban areas and economic reward concern; many decision-makers privilege place-marketing over placemaking and fiscal well-being over people well-being (Ng Citation2016). However, human welfare should step from purely economic considerations to the need to develop people’s capabilities to become positive functioning members of a community (Zitcer et al. Citation2016). Fundamentally, ‘economic development is to allow us to survive well together and equitably …, and to invest our wealth to ensure the well-being of future generations’ (Gibson-Graham et al. Citation2013, p. xvi-xvii).

All in all, upon acknowledging the profound impacts of the (re)configuration of the living environment on human wellbeing, many researchers have dedicated to the socio-spatial assemblage of the two. A wealth of research affirms the significances of greenspaces, walkability and social connectivity and the subsequent sense of belonging for nurturing the state of wellbeing in urban placemaking, whist claiming that the safety concern could be a holdback and high-rise design should be avoided. Nevertheless, the search for leverage points for the socio-spatial assemblages of human wellbeing and the configuration of their living environment is not sufficiently done (Richardson et al. Citation2020); and how exactly new developments should be designed to deliver positive impacts on dwellers’ wellbeing remains unclear (Ng Citation2016). The recent COVID-19 pandemic has exerted more stress on human wellbeing (Kelsey and Chiara Citation2021), placing an urgent call on how to reframe planning practice to accommodate this social-spatial assemblage.

Methodology: case study approach

Case study research offers in-depth insights into specific instance or event, making it possible to uncover nuanced details and layers of the situation to explore variables in real-life settings that might be difficult to examine through other research methods (Yin Citation2003, Lee and Saunders Citation2017). Departing from a case study approach, this paper investigated how the project development of Wapping Wharf in Bristol has impacted the dwellers’ well-being and to what extent their actions altered the living environment, aiming to provoke more thoughts on this assemblage of dweller wellbeing and urban spacemaking for post-pandemic planning informing. The criteria for the case selection were, first, it was developed over a brownfield site on which the integration of greenspaces could be more challenging compared to those built on Greenfields; second, being a mixed-use development, the concept of walkability was inevitably integrated in the placemaking.

Methodologically, the study involves 22 interviews with developer, architect, planner, researcher, estate agent, resident, retailer owner and shop staff who are related to the case project. The resident and retail interviewees were selected via convenience sampling, while the rest were purposely appointed through network. Resident Interviewees are a mix of genders with an age range from 32 to 67. Apart from one couple living with a three-year boy, the rest resident interviewees were either couples or singles. The interview question lists were slightly different for the interviewee cohorts. Interviews were conducted in semi-structured format, aiming to provide room for interviewees to bring up their thoughts during the interview. Seven interviews were conducted online via Microsoft Teams due to the COVID-19 restrictions, with the rest carried out face to face onsite (e.g. cafes, public places). The analysis of the interview materials is supplemented by further literature review and seven site observations conducted between February 2020 and August 2022. The empirical data collection has strictly followed the Research Ethics Policy and Procedure by the authors’ affiliated organisation.

Discussion of the case study

The case project

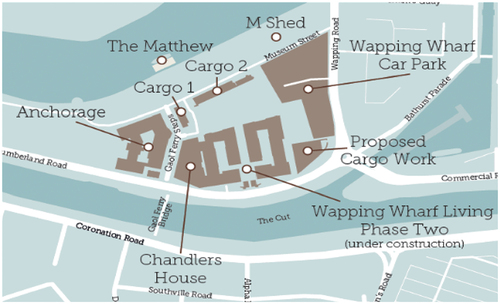

The Wapping Wharf project site sits on the harbour of River Avon which runs through the city centre of Bristol, England (). The site was a dockyard (see ; for the history of the site please see https://bristolcitydocks.co.uk/wapping-railway-wharf-2/). Following the decline of the dockyard trade in the 1950s and 60s, the area was largely disused. The Developer, Umberslade, purchased the site in 2003, and spent three years (instead of the planned 18 months) on negotiating with the local authorities about the project development masterplan, which was finally approved in 2007. With a construction area of approximately 500,000 square feet over the 7-acre land, the site was primarily to be developed into a residential area with some commercial, retail and leisure facilities (see for the masterplan). The commercial areas would locate on the ground floors of the residential buildings of Phase 1 and Phase 2, and the Cargo 1 and Cargo 2, the first-ever retail units converted by shipping storage containers in Bristol. The rental operation of these commercial units would be retained by the Developer. The office areas of the Cargo Work at the corner of Wapping Road and Cumberland Road (see ) would be developed in the final stage of the project.

The Developer planned to initiate the project construction in 2008 and complete it by 2030. However, interrupted by the Global Financial Crisis, the construction of Phase 1 was delayed to 2012 and then completed in 2014. It consisted of two apartment blocks, namely Chandlers House and Anchorage, with 194 apartment units including private market housing, affordable housing, and shared-ownership units. The Old City Gaol gatehouse between the two blocks was renovated as the main pedestrian through route of the site ().

The development of the commercial areas was introduced in Spring 2015 and completed in stages by 2018. Forty-five independent businesses (ranging from café, mini supermarket, restaurant, pub and bar, etc.) occupied the commercial areas. showed the example of a restaurant in Cargo 2. Upon completing the sale of Phase 1 and the rental organisation of the commercial units, the Developer moved to the Construction of Phase 2 in 2018, and the site preparation for the Cargo Work (the to-be office area) in February 2020; however, the development was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As of the research time, along with the construction work on the east side of the site, the west part of ‘Wapping Wharf is a flourishing new neighbourhood in the historical and cultural heart of Bristol where people can live, shop, eat and relax by the city’s glistening waterfront’ (Wapping Wharf website Citationn.d.). The average housing price of Phase 1 was £305,000 (Rightmove Citation2022), higher than the average price of £260,500 for flat/maisonette in City of Bristol as of August 2022 (Government UK Citation2022). The Frase 1 area contained a rented housing rate of 46%, in contrast with the national average of around 20%; 93% units were occupied by couple or singles; and 74% residents aged between 20 and 50 (Streetcheck Citationn.d.). Based on the assessment criteria for household deprivation by 2021 Census (which was measured against four dimensions – employment, education, health/disability, and overcrowding), 73% of households at Wapping Wharf were categorised as not deprived (Streetcheck Citationn.d.). Site observation taken at 21:00 on a weekday in February 2022 on the lighting of the residential buildings suggested an occupancy rate of around 85%. These statistical data suggested that Wapping Wharf was an upmarket housing area, resided mainly by young, up-middle income and small size households.

Factors that enable positive functioning of dweller wellbeing in the case project

This session identifies the major factors that impacted the inhabitants’ wellbeing in the case project, with evidence collected from the semi-structured interviews, site observations, and further literature view. All the resident interviewees said yes to the first question of ‘are you enjoying living here?’. Answers to the question of ‘what are the factors that make living here enjoyable?’ and the follow-up questions varied, which are to be discussed below.

Greenspaces

All the interviewees highlighted the factor of greenspaces as a key contributor. As of the site observation time, the onsite greenspaces largely included trees and shrubs which lined the walkways or around the buildings planted during the development. showed an example. Answers to the follow-up question about the sufficiency of onsite greenspaces varied. ‘We don’t think there needs to be more greeneries; we have the amazing harbour view’ (Resident Interviewee 15). ‘Here is open and light. If I need some fresh air to clear my head, I often lock up my container and go for a walk around the harbour’ (Retailer Interviewee 7). ‘Seeing butterflies dancing in the shrubs already makes my day’ (Resident Interviewee 16). These answers supported the literature review on the benefits of urban greenspaces to nurturing inhabitants’ emotional wellbeing.

Although most of the interviewees seemed content with the current setting of the onsite greenspaces, some anticipated more. A useful way to incorporate greenspaces into a development is to keep the existing greeneries (Lim and Xenarios Citation2021); However, this did not apply to the case site. According to Developer Interviewee 1, ‘landscaping around the industrial shipping harbour is difficult; it has never to have trees growing there’. The Developer once proposed to plant more trees around the Museum Square (next to the M-Shed in ). However, this was not approved by the planning authorities due to the undefined ownership of this brownfield plot. ‘It is a shame that the Museum Square cannot be incorporated into the Wapping Wharf Development’ (Architect Interviewee 5). Resident Interviewee 13 then suggested a public lawn area with lined trees to be part of the Cargo Work (the to-be office areas): ‘that would not only provide more greenspaces for us, but also encourage staff working there to take more outdoor breaks’. Researcher Interviewee 6 commented that the design of urban places should provide inhabitants with opportunities to connect with nature as many as possible; hence there would be never sufficient greenspaces in urban placemaking.

Some interviewees particularly expressed their options about the form of greenspaces. ‘I am always inclined to spend more time in outdoor green and peaceful areas; for me, the green colour has its magic in reducing the degree of my stress’ (Resident Interviewee 14). Resident Interviewee 17 and 18 however claimed that greenspaces were not necessary to be green and the harbour water was equivalent to greenery. This echoes Geary et al. (Citation2021)’s work, which used the term blue-green space (greenery sites and watercourses) rather than greenspace to include a fuller range of natural spaces in urban settlements.

Aesthetical design

The interviewees applauded the modern and neat look of the Wapping Wharf, with all buildings no more than 6-story height (see ). Being aware that high-rise placemaking could interrupt social connectivity, neither the planning authorities nor the Developer favoured the high-rise design. ‘It’s hard to retain the quality of public realm around the high-rise buildings; a high-rise development would have destroyed the relaxing and uplifting environment that Wapping Wharf has created today’ (Architect Interviewee 5). Both Resident Interviewee 11 and 16 believed the development would not be as popular if it were clustered with high-rise building. ‘Our settlements provide a sense of pride and an identity to which we can relate; Wapping Wharf will be out of our consideration if it were designed with high-rise buildings’ (Resident interviewee 18).

Access to daily facilities

Most interviewees highlighted that the neighbourhood design with non-motored interconnected pedestrian and cycling access to amenities, businesses, and commons at Wapping Wharf encouraged dwellers to walk or cycle around. ‘The whole philosophy to begin with was how we can create a space where people can spend the whole day’ (Developer Interviewee 1). ‘It is far more enjoyable walking around a neighbourhood with good facilities on your doorstep than on the high street’ (Resident Interviewee 19). ‘There are 2 routes to work for my friend who lives in Southville (an area next to south of Wapping Wharf); the one through Wapping Wharf is slightly longer but she chooses it most of the time because she enjoys the atmosphere here’ (Resident Interviewee 22). Resident Interviewee 13 who used to live in Portishead stated that ‘we don’t use our cars as much as we used to; instead, we cycle and walk around whenever possible’. Site observations indicated improved air quality and reduced noise by less traffic inside the neighbourhood.

It is noted that good public transport services surrounding the site helped reduce dwellers’ car-use dependency. Resident Interviewee 15 took buses around the Wapping Wharf to and from work instead of driving as before. Resident Interviewee 14 stated that walkability was one of the highlights in his housing purchase decision-making: ‘I was looking to live somewhere that could embrace my car-free lifestyle; now I could go around by walk, cycle, bus or cars. Life is brilliant as I have choices’. Indeed, ‘a particular person’s well-being achievement is a reflection of her uncoerced choices among alternatives’ (Zitcer et al. Citation2016, p. 38).

The choice of food played an essential role in assessing the quality of life. Scutelnicu (Citation2017) identified good link between human wellbeing and healthy eating. Wapping Wharf offered a good range of hospitality from Asian and Western choices with most retailors rated top 200 out of the 1803 restaurants in Bristol as of August 2022, according to TripAdvisor rating. Wapping Wharf became a famous place in Bristol for dine-out, ‘attracting many outsiders to dine here … Yet it is not just about the number of customers. We aim to create a high-quality healthy dine-out place’ (Retailor Interviewee 7). The supermarket named Better Food sold organic fruits and vegetables, fairtrade groceries, and ethical household goods, etc. The concept of healthy eating was also shared by the residents. For instance, Resident Interviewee 20, a regular shopper to this supermarket, highly rated the importance of healthy eating to health and well-being: ‘when my body is healthy, so does my brain’.

Neighbourhood safety

As discussed in Session 2, feeling unsafe or vulnerable within their living spaces could discourage inhabitants’ outdoor activities; however, site observations and interviews revealed that this did not bother the residents at Wapping Wharf. Several interviewees mentioned that the site was well lit at night which made them feel safe. The high-volume and steady population flow by the dine-out business prosperity within the neighbourhood particularly around the area of Gaol Ferry Steps created a ‘self-policing’ environment. ‘The busier Wapping Wharf is, the safer I feel’ (Resident Interviewee 17). Even Retailer Interviewee 8, who had an unfortunate experience when her bag was stolen from her van parked outside her retail unit, put a positive tongue on the overall onsite safety.

Social connectivity

As stated in the literature review, non-motored interconnected pedestrian design with good onsite facilities and pleasant greenspaces encourages more walks and cycling, creating the opportunities to socialize with others (Nicholas et al. Citation2017). Resident Interviews showed their enjoyment of shopping, entertaining and socializing on their doorsteps in the neighbourhood. ‘I love hanging around here; there’s always a great buzz’ (Resident Interviewee 18). Site observations showed that the Wild Beer, had become a meet-up point of the neighbourhood, functioning as the marketplace or a local pub seen in many traditional towns or villages in England. Echoing Burningham and Venn (Citation2022)’s research, eating-related facilities at the Whopping Wharf provided friendly and safe social spaces where inhabitants to meet up; beyond immediate opportunities to meet existing friends, such activities enabled the residents to know more cultures and customs in the multiethnic neighbourhood. These social interactions helped develop the senses of self-discovery and acceptance, learning new, and acquire skills for mastering the environment, a sign of positive psychological and social well-being.

The diversification of small and independent business was believed to partially contribute to the social connectivity by encouraging inhabitants to shop more inside the neighbourhood. ‘I love independent retailers, I would 100% not want a Tesco here’ (Resident Interviewee 17). Retailer interviewee 9, once worked in high street, stated that ‘they (customers) don’t mind if we make small mistakes; they trust you and we get to know each other better and better. My work is less stressful here’. Developer smartly detected this trend: ‘we are considering more independent retails and possibly a cinema as demanded by the Phase 1 residents’ (Developer Interviewee 2).

It was noted that the format of social connectivity was not limited to physical meetups; many residents communicated frequently through the social media apps of Nextdoor and WhatsApp, etc. about the ongoings around Wapping Wharf. The convenience and accessibility of such digital tools motivated them to search for like-minded groups and provided instant access to communicate with others and get closer with each other, expanding their social connectivity into the non-physical notion and creating a virtual version of Wapping Wharf community. ‘With this (phenomenon), we planners should take the use of digital tools into account in post-pandemic planning’ (Planner Interviewee 3).

Community vitality

The Wapping Wharf community, which was established in 2015 initially to deal with some snagging issues with the Developer upon the completion of Phase 1, later was turned into a platform that cemented the residents through various event and activity organisations. “Seasonal culinary events took place at Wapping Wharf, such as Wokyfest for the Chinese New Year, Harbour Festival and Easter scavenger hunts, and so on. The Eatable Bristol Club organised the planting of herbs and wildflowers in some neglected patches and corners of Wapping Wharf, adding tiny bit greeneries to the site. ‘We can learn and survive better as groups’ (Resident Interviewee 21). A strong sense of belonging had been gradually developed over such active social interactions and event participations. ‘We are so proud of being part of the Wapping Wharf Community’ (Resident Interviewee 14); and ‘I feel more part of the community here than I have done at any of my previous homes; I belong here’ (Resident Interviewee 19). Through various organised events, the dwellers acquired skills to master the environment, secured autonomy and discovered their purpose in life, positively enabling the feeling of social-acceptance, actualization, integration, contribution, etc.

It was noted that the scope of participation was not limited to community events but also extended to the project development. The residents demonstrated strong desires for project participation, reflected by their proposals of cinema and lawn place, etc. to the Developer. Residents actively feedbacked on the consultation for the design of Wapping Wharf North. Some interviewees voiced that they would like more communal areas, e.g. a barbeque or fire-pit area to accommodate the community events and gatherings. Active and spontaneous resident participation was welcomed by the Developer and proved to have steered better placemaking in the case project.

The strong belonging sense bonded community resilience to challenges and difficulties by the COVID-19 Pandemic. The lockdown in March 2020 cooled off the business and social interactions. Resident Interviewees described the neighbourhood as being as empty as it was on Christmas Day. Three resident interviewees who were living alone, described the first few days of lockdown as nightmares, ‘as you don’t know when this will end’ (Resident Interviewee 19). Though living alone might not necessarily mean feeling lonely (Kelsey and Chiara Citation2021), the previous studies did show that cohabitation could lead to a lasting improvement in well-being (Zimmermann and Easterlin Citation2006). ‘I start planting tomatoes and herbs in the balcony and give some to my neighbours; we get to know more about each other’ (Interviewee 14). ‘Devolving myself to home-planting to competing with neighbours help ease my stress in this dark time (Pandemic)’ (Resident Interviewee 17). Some residents invited neighbours to home ‘to make sure that we are still up’ (Resident Interviewee 20), strengthening a greater sense of security and safety. Struggling with the dine-ins, some retailers started takeaway and delivery services. This was supported by the residents in their attempt to help the business; ‘even sometimes it was not necessary to order a takeaway’ (Resident Interviewee 20). Retail Interviewees highly appreciated this: ‘It’s bringing the good out in a lot of people in this wonderful community … The COVID-19 is bringing all of us closer to each other’ (Retail Interviewee 7). ‘The strong community bonding softens the hardness of steel, glass and concrete in the difficult time at Wapping Wharf, making people here happier’ (Researcher Interviewee 6). Indeed, as Giannetti et al. (Citation2022) concluded from their case study in São Paulo, Brazil, community vitality, was the one of the main contributors to residents’ happiness.

Even the Developer, which was generally seen as the outsider of the Community before the Pandemic, made the efforts on well maintaining the site during the lockdown. ‘I know that things are not going to get back to how they were quickly; But I hope every single business here can reopen and start trading successfully’ (Developer Interviewee 1). The Developer Interviewee 2 well responded to the request for fire-pit from residents: ‘we are indeed considering about making more common spaces in the later development’; ‘We get criticised for gentrifying the docks, but at the same time we are trying to create a pleasant and safe place for everyone. Knowing that they are happy here, I am relieved’ (Developer Interviewee 1).

Developer’s effort during the Pandemic was applauded by the residents: ‘a well-maintained and tidy area makes you feel a lot safer and more pleasant particularly in time of stress’ (Interviewee 13); and it was also rewarded by the market. The estate agent interviewee 4 identified the high demand for the apartments of the Phase 2. ‘Two friends of mine are buying here because they admire our lifestyle and want to be part of Wapping Wharf’ (Resident Interviewee 18). ‘I can’t say that I ever realised the importance of community at the early stage of the development, and I did not anticipate the benefits of this mouth-to-mouth advertisement neither’ (Developer Interviewee 1).

All in all, the discussion above highlighted the significance of some factors (e.g. greenspaces, aesthetical design, access to daily facilities, safety, social connectivity, community vitality, etc.) in contributing the assemblage of new placemaking and dwellers’ wellbeing in the case project. In particular, the factor of urban greenspace was proved to have its power to alleviate dwellers’ stress and anxiety; the integrity of more greenspaces into new placemaking was more emotionally demanding than ever during the Pandemic. Walkability backed up by good facility access encouraged more outdoor exercises, reducing car-reliance, and cementing social connectivity. Along with the onsite physical facilities, the residents used some digital tools (e.g. WhatsApp, Next-door) as platforms to participate, share, and develop abilities to tackle difficulties and challenges by the Pandemic, providing inhabitants with more lifestyle choices, enhancing environmental mastery, and promoting social integration. Food-related amenities and activities (e.g. culinary event organisations, the function of Wild Bar as gathering point, home-planting, the pursuit of healthy dine-out, the high-rating of the supermarket), jointly indicated that the concept of food directly or indirectly was playing a significant role in enhancing personal-life satisfaction and delivering good spirits. Indeed, there is widespread acknowledgement by public health research that (re)formulating the food system (consumption choices and supply chains) is key in helping cities tackle social and environmental challenges (Fanzo Citation2019). Numerous research (e.g. Bagwell Citation2011, Burgoine et al. Citation2018, Kelly et al. Citation2019) approved that the quality of food consumption, combined with limited physical activities, contributed to rising obesity levels. At the psychophysical level, the access to healthy food is paramount to social justice, especially in cities with a mix of race, class and ethnicity, etc. (Heynen et al. Citation2012, Agyeman et al. Citation2016, Burgoine et al. Citation2018).

Nevertheless, these factors were not isolated but casually related to each other in prompting dwellers’ wellbeing at Wapping Wharf. A neighbourhood with pleasant greenspaces encouraged more walks and promoted dwellers’ social interactions. Access to good amenities encouraged outdoor exercises and reduced car-reliance, which, together with the pleasant greenspaces and aesthetical building designs, provided a supportive system to encourage social connectivity. The high-volume gathering by community prosperity created a self-policing environment encouraging more walks and cycling around the neighbourhood. Food was the theme of events and activities, enabling many social interactions. With the strong sense of community belonging developed through social connectivity, residents created more onsite greeneries (e.g. aforementioned dotted herbs and wildflowers). The finding of this causal relationship implied that these factors should be considered at a holistic rather than isolated level in urban placemaking.

It is worth noting that the highlights of these factors in this paper does not imply that the contributors to promoting human wellbeing in urban placemaking are limited to these. The sustainability of human wellbeing is the capability to live well or to achieve a good life within environmental limits (Burningham and Venn Citation2022). However, the understanding of living well ‘is conceptualised’ (Moore and Woodcraft Citation2019, p. 277), and people’s ideas about what makes for a good life are socially and culturally shaped, varying over places, cultures and generations (Fattore et al. Citation2019). The state of wellbeing is determined by a range of socioeconomic, biological, and environmental factors (WHO Citationn.d.), and placemaking is place- and time-specific (Ball et al. Citation1999). With dynamics being the feature of the state of human wellbeing and placemaking, the contributors to the assemblage of the two should vary across scenarios and timelines.

A mutually reinforcing relationship between urban placemaking and human wellbeing

The analysis of the qualitative interviews and site observation echoes the discussion in Session 2 by reaffirming the profound impacts of urban place-making on human wellbeing. Healthy placemaking enables human flourishing through the provision of natural, social or intellectual stimulus (Amin et al. Citation2000). The analysis demonstrates that the living environment at Wapping Wharf provided inhabitants with access to contact with nature and lifestyle with choices; encouraged more physical exercises; generated platforms to participating, sharing, learning, and created opportunities of developing abilities to tackle difficulties and challenges by the Pandemic, through which the inhabitants were able to achieve their positive functioning of emotional wellbeing (e.g. self-acceptance, self-value acknowledgement), physiological wellbeing (e.g. better personal growth, environment mastery), and social wellbeing (e.g. integration, contribution). Indeed, ‘healthy placemaking is the premise for wellbeing enhancement’ (Researcher Interviewee 6).

As stated in the literature review, people are simultaneously natural, social and intellectual beings and have a constitutive relationship with places that they live in (Sack Citation1993, p. 329). Their perceptions and subsequent actions towards their surroundings will be orientated by the levels of their self-acceptance, social approval, the need to pursue, the motivation for environment mastery, etc. (Morsella et al. Citation2009). When people are living in a pleasant, safe and connected community with strong emotional support and love, they are willing to develop capabilities to improve their beloved community and shape the built environment, either directly or indirectly (Ng Citation2016). The analysis thus suggests that, while placemaking has a profound impact on human wellbeing, the latter could reversely shape their living places. A mutually reinforcing relationship between urban placemaking and dwellers’ wellbeing is identified in this paper.

Conclusions

This paper explored how the project development of Wapping Wharf in Bristol impacted the dwellers’ well-being and to what extent they shaped their living environment. It reaffirms the significances of some contributors to promoting dweller wellbeing in urban placemaking highlighted in the literature review session particularly in the following aspects. First, the factor of urban greenspace is proved to have its power to alleviate dwellers’ anxiety; yet greenspaces are not necessary to be green but could be any congener (e.g. blue water, colourful flowers). In this regard, nature could be a more appropriate wording than greenspace as a contributor to promoting wellbeing in urban placemaking. Second, the significance of walkability identified in this paper suggests that the format of mix-used property development could serve as a good strategy to accommodate the call for better assemblage between urban placemaking and human wellbeing in post-pandemic planning. Third, residents used digital tools as virtual platforms to master the environment and realize their social-integration, acceptation and contribution. This paper thus suggests that practitioners (e.g. planners, architects, developers) could incorporate the virtual flatforms with physical design in making and managing urban places so as to enhance the state of dweller’s wellbeing. Last but not least, the discussions about food-related amenities and activities indicate that food, or more accurately health eating, could promote dwellers’ wellbeing through personal-life satisfaction, good spirits, and social integration. In this regard, how to design supportive amenities and facilities in urban placemaking to enable more and easier access to health eating (e.g. onsite organic food supplies, space-design for home-planting, eating-well event facilities) could promote residents’ health both physically and mentally. At the theoretical level, while previous research identified good link between healthy eating and human welling (e.g. Scutelnicu Citation2017), this paper suggests a positive correlation between healthy eating and urban placemaking.

The discussion in this paper confirms the profound impact of urban placemaking on human wellbeing stated in the literature review. Development is not just about physical construction on the land; healthy urban space-making could enable human flourishing through the provision of natural, social or intellectual stimulus, leading to the positive functioning of dwellers’ wellbeing in emotional, physiological, and social aspects. Meanwhile, it is evident from this study that dwellers’ behaviours could reversely shape the dynamic place-making process; new placemaking is not a one-off, but a dynamic, deliberative, reflective, reciprocating process; Sincere communications between the producers and the users of urban places indeed have helped better new placemaking and resident wellbeing enhancement. In this regard, the relationship between urban placemaking and dwellers’ wellbeing is not just constitutive (Sack Citation1993), but also mutually reinforcing.

While previous research on the assemblage of placemaking and wellbeing largely casts lights on the former (placemaking), this paper, with the finding of the above mutually reinforcing relationship, extends the discussion by calling for attention to the later (dweller wellbeing). The strong sense of community belonging developed through active participation is approved to have its great power in consolidating community resilience against the stress generated in time of crisis and disasters (in this case, the Pandemic). In this regard, any factors that can facilitate or have the potential to facilitate dweller participation should be considered, if not prioritized, in post-pandemic placemaking.

A limitation in the methodological design should be noted at the end of the paper. Case study methodology generally features with the lack of generalizability: the findings of the study of a single social unit are not usually generalizable to the larger population of similar units due to its focus on specific instances or individuals (Yin Citation2003). With the case project being designed as flats occupied by young and small-size households, the research findings, though could provide good insights for city centre regeneration projects, might have its limitation for projects with different characters.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jo Zhou

Jo Zhou’s research interest mainly focuses on the momentum, processes and impacts of urban transformation and the relationships within growth, people and the built environment in the East-West comparative context, including but not limited to urban transformation and social inequality, urban governance and regime politics, citizen participation and community dynamics.

Esme Hatton

Esme Hatton graduated from the Real Estate Programme at University of the West of England. Currently I am working as the Development and Asset Manager at Umberslade, a reputable property development, management and investment company in the UK.

References

- Agyeman, J., et al., 2016. Trends and directions in environmental justice: from inequity to everyday life, community and just sustainability. Annual review of environmental resources, 41 (6), 321–340. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090052.

- Amin, A., Doreen, M., and Thrift, N., 2000. Cities for the many not the few. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Bagwell, S., 2011. The role of independent fast-food outlets in obesogenic environments: a case study of east end London in the UK. Environment and planning A, 43 (9), 2217–2236. doi:10.1068/a44110.

- Ball, M., Lizieri, C., and MacGregor, B., 1999. The economics of commercial property markets. London: Routledge.

- Barton, H., et al., eds., 2015. The Routledge handbook of planning for health and well-being. London: Routledge.

- Beery, T., Ingemar J¨onsson, K., and Elmberg, J., 2015. From environmental connectedness to sustainable futures: topophilia and human affiliation with nature. Sustainability, 7 (7), 8837–8854. doi:10.3390/su7078837.

- Bristol city docks, n.d. Wapping railway wharf. Available from: https://bristolcitydocks.co.uk/wapping-railway-wharf-2/ [Accessed 5 January 2023].

- Burgoine, T., et al., 2018. Examining the interaction of fast-food outlet exposure and income on diet and obesity: evidence from 51,361 UK biobank participants. International journal of behavioural nutrition & physical activity, 15 (1), 71. doi:10.1186/s12966-018-0699-8.

- Burningham, K. and Venn, S., 2022. Two quid, chicken and chips, done”: understanding what makes for young people’s sense of living well in the city through the lens of fast-food consumption. Local Environment, 27 (1), 80–96. doi:10.1080/13549839.2021.2001797.

- Carver, L.F., et al., 2018. A scoping review: social participation as a cornerstone of successful aging in place among rural older adults. Geriatrics, 3 (4), 75. doi:10.3390/geriatrics3040075.

- Centre for Active Design, 2018. Assembly: civic design guidelines. Available from: https://civicas.net/art-1/2018/6/27/center-for-active-design-assembly-civic-design-guidelines [Accessed March 2020].

- Cox, D.T., et al., 2018. The impact of urbanisation on nature dose and the implications for human health. Landscape and urban planning, 179, 72–80. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.013

- Dannenberg, A.L., Frumkin, H., and Jackson, R.J., eds., 2011. Making healthy places: designing and building for health, well-being, and sustainability. Washington: Island Press.

- Dobson, J., et al., 2019. Space to thrive: a rapid evidence review of the benefits of parks and green spaces for people and communities. London: The National Lottery Heritage Fund and The National Lottery Community Fund.

- European Environment Agency, 2017. Managing exposure to noise in Europe. Available from: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/managing-exposure-to-noise-in-europe [Accessed 12 September 2022].

- Fanzo, J., 2019. Healthy and sustainable diets and food systems: the key to achieving sustainable development goal? Food ethics, 4 (2), 159–174. doi:10.1007/s41055-019-00052-6.

- Fattore, T., Fegter, S., and Hunner-Kreisel, C., 2019. Children’s understandings of well-being in global and local contexts: theoretical and methodological considerations for a multinational qualitative study. Child indicators research, 12 (2), 385–407. doi:10.1007/s12187-018-9594-8.

- Foster, S., et al., 2016. Are liveable neighbourhoods’ safer neighbourhoods? Testing the rhetoric on new urbanism and safety from crime in Perth, Western Australia. Social science & medicine, 164, 150–157. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.013

- Fretwell, K. and Greig, A., 2019. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between individual’s self-reported connection to nature, personal well-being and environmental awareness. Sustainability, 11 (5), 1386. doi:10.3390/su11051386.

- Friedmann, J., 1998. The new political economy of planning: the rise of civil society. In: M. Douglass and J. Friedmann, eds. Cities for citizens. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 19–35.

- Frostick, C., et al., 2017. Well London: results of a community engagement approach to improving health among adolescents from areas of deprivation in London. Journal of community practice, 25 (2), 235–252. doi:10.1080/10705422.2017.1309611.

- Geary, R.S., et al., 2021. A call to action: improving urban green spaces to reduce health inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19. Preventive medicine, 145, 106425–106425. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106425

- Generalova, E., et al., 2018. Mixed-use development in high-rise context. E3S Web of Conferences 33, Available from: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2018/08/e3sconf_hrc2018_01021.pdf [Accessed November 2022].

- Giannetti, B.F., et al., 2022. The ecological footprint of happiness: a case study of a low-income community in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Sustainability, 14 (19), 12056. doi:10.3390/su141912056.

- Gibson-Graham, J.K., Cameron, J., and Healy, S., 2013. Take back the economy: an ethical guide for transforming our communities. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Government UK, 2022. House price statistics: city of Bristol. Available from: https://landregistry.data.gov.uk/app/ukhpi/browse?from=2022-08-01&location=http%3A%2F%2Flandregistry.data.gov.uk%2Fid%2Fregion%2Fcity-of-bristol&to=2023-08-01&lang=en [Accessed 12 January 2024].

- Hajna, S., et al., 2015. Associations between neighbourhood walkability and daily steps in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC public health, 15 (1), 768. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2082-x.

- Heynen, N., Kurtz, H.E., and Trauger, A., 2012. Food justice, hunger and the city. Geography compass, 6 (5), 304–311. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00486.x.

- Hipp, J.R., et al., 2014. Examining the social porosity of environmental features on neighbourhood sociability and attachment. Public library of science One, 9 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084544.

- Jackson, T., 2017. Prosperity without growth. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jorgensen, A. and Keenan, R., eds., 2012. Urban wildscapes. London: Routledge.

- Kelly, C., et al., 2019. Food environments in and around post-primary schools in Ireland: associations with youth dietary habits. Appetite, 132, 182–189. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2018.08.021

- Kelsey, J.O., and Peroni, C., 2021. One in three Luxembourg residents report their mental health declined during the COVID-19 Crisis. International journal of community well-being, 4, 345–351.

- Keyes, C.L.M., 2003. Complete mental health: an agenda for the 21st century. In: C.L.M. Keyes and J. Haidt, eds. Flourishing: positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association, 293–312.

- Kimpton, A., Corcoran, J., and Wickes, R., 2017. Greenspace and crime: an analysis of greenspace types, neighbouring composition, and the temporal dimensions of crime. The journal of research in crime and delinquency, 54 (3), 303–337. doi:10.1177/0022427816666309.

- Koninx, F., 2019. Ecotourism and rewilding: the case of Swedish Lapland. Journal of ecotourism, 18 (4), 332–347. doi:10.1080/14724049.2018.1538227.

- Kuboshima, Y. and McIntosh, J., 2023. The impact of housing environments on social connection: an ethnographic investigation on quality of life for older adults with care needs. Journal of housing and the built environment, 38 (3), 1353–1383. doi:10.1007/s10901-022-09999-1.

- Lai, K.Y., et al., 2020. Are greenspace attributes associated with perceived restorativeness? A comparative study of urban cemeteries and parks in Edinburgh, Scotland. Urban forestry and urban greening, 53, 126720. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126720

- Lee, B. and Saunders, M.N.K., 2017. Conducting case study research for business and management students. London: SAGE Publications.

- Lim, M. and Xenarios, S., 2021. Economic assessment of urban space and blue-green infrastructure in Singapore. Journal of urban ecology, 7 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1093/jue/juab020.

- Moore, H. and Woodcraft, S., 2019. Understanding prosperity in East London: local meanings and sticky measures of the good life. City & society, 31 (2), 275–298. doi:10.1111/ciso.12208.

- Morsella, E., Bargh, J.A., and Gollwitzer, P.M., eds., 2009. Oxford handbook of human action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ng, M.K., 2016. The right to healthy place-making and well-being. Planning theory & practice, 17 (1), 3–6. doi:10.1080/14649357.2016.1139227.

- Nicholas, A.H., et al., 2017. Residential or activity space walkability: what drives transportation physical activity? Journal of transport & health, 7, 160–171. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2017.08.011

- Nichols, C. and Del Casino, V., 2021. Towards an integrated political ecology of health and bodies. Progress in human geography, 45 (3), 776–795. doi:10.1177/0309132520946489.

- Nordin, S., et al., 2017. The physical environment, activity and interaction in residential care facilities for older people: a comparative case study scandinavian. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 31 (4), 727–738. doi:10.1111/scs.12391.

- Richardson, M., et al., 2020. Applying the pathways to nature connectedness at a societal scale: a leverage points perspective. Ecosystems & people, 16 (1), 387–401. doi:10.1080/26395916.2020.1844296.

- Rightmove, 2022. House prices in Wapping Wharf. Available from: https://www.rightmove.co.uk/house-prices/wapping-wharf-94595.html [Accessed 3 January 2023].

- Russell, R., et al., 2013. Humans and nature: how knowing and experiencing nature affect well-being. Annual review of environment and resources, 38 (1), 473–502. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012312-110838.

- Sack, R.D., 1993. The power of place and space. American Geographical Society, 83 (3), 326–329. doi:10.2307/215735.

- Sallis, J.F., et al., 2016. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: across-sectional study. Lancet, 387 (10034), 2207–2217. (British edition): doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01284-2.

- Sandom, C.J., et al., 2019. Rewilding in the English uplands: policy and practice. Journal of applied ecology, 56 (2), 266–273. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13276.

- Scannell, L. and Gifford, R., 2017. The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. Journal of environmental psychology, 51, 256–269. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.04.001

- Scutelnicu, G., 2017. How do healthy eating and active living policies influence the potential for a community’s healthy behaviour? The case of Mississippi State. Journal of health and human services administration, 40 (3), 310–352.

- Shanahan, D.F., et al., 2016. Health benefits from nature experiences depend on dose. Scientific Reports, 6 (1), 28551. doi:10.1038/srep28551.

- Streetcheck, n.d. Area information for gaol ferry steps, Bristol. Available from: https://www.streetcheck.co.uk/postcode/bs16uw [Accessed 12 January 2024].

- Subiza-P´erez, M., Vozmediano, L., and San Juan, C., 2020. Green and blue settings as providers of mental health ecosystem services: comparing urban beaches and parks and building a predictive model of psychological restoration. Landscape and urban planning, 204, 103926. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103926

- United Nations, 1968. Final act of the international conference on human rights. New York, NY: United Nations.

- Wapping Wharf website, n.d. Available from: http://wappingwharf.co.uk/vision [Accessed 12 January 2023].

- Wendelboe-Nelson, C., et al., 2019. A scoping review mapping research on green space and associated mental health benets. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16 (12), 1–49. doi:10.3390/ijerph16122081.

- WHO, n.d. Health and Well-Being. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being [Accessed November 2022].

- Wolfram, M. and Frantzeskaki, N., 2016. Cities and systemic change for sustainability: prevailing epistemologies and an emerging research agenda. Sustainability, 8 (2), 144.

- Yin, R., 2003. Case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zhang, Y., et al., 2015. Green space attachment and health: a comparative study in two urban neighbourhoods. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12 (11), 14342–14363. doi:10.3390/ijerph121114342.

- Zimmermann, A.C. and Easterlin, R.A., 2006. Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and happiness in Germany. Population and development review, 32 (3), 511–528. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00135.x.

- Zitcer, A., Hawkins, A., and Neville Vakharia, N., 2016. A capabilities approach to arts and culture? Theorizing community development in West Philadelphia. Planning theory & practice, 17 (1), 35–51. doi:10.1080/14649357.2015.1105284.