ABSTRACT

Imaginaries of smart, sustainable autonomous vehicles carrying people of all ages and abilities to relax en-route to myriad destinations, evoke a sweet surrender to the machine. But such technocratic visions clash with visions of non-anthropocentric autonomy. The urgency of mobility transformation in the face of ecological overshoot makes this a site of turbulence where new “structures of feeling” are emerging. But how to study changing structures of feeling and apply insights? In this paper we discuss an exploratory study with twelve users of autonomous vehicles, non-users, engineers, and experts in China and the UK who used galvanic skin response sensors to probe their autonomobile emotions. Extending Christian Nold’s Bio Mapping approach, we discuss fissures in values and norms about mobility and the prospect of doughnut mobilities, concluding with reflections on applied mobilities research.

1. Introduction

The world market for autonomous vehicles (AV) is set to double to nearly 62 billion U.S. dollars in 2026 (Placek Citation2022). One of the top accounting firms in the world reports that in China autonomous driving is “frequently referred to as the ‘mobile third space’”, a “transformation [that] is already changing the value chain of the automotive industry”, where “true autonomous driving will transform our concepts of mobility, logistics, … personal and professional lives” (KPMG Citation2022, 2). Amidst such visions of sweet surrender, it seems that a new autononomobility system is born (Yu Citation2022).

This new autonomobility system may use the same streets as the automobility system (Urry Citation2004), but if combined with electrification and shared transport, CO2 emissions could be 80% lower than business as usual (Fulton Citation2018). Transport accounts for around 25% of CO2 emissions worldwide and “transformational adaptation will be necessary to limit intolerable risks” from climate change (IPCC Citation2022, 11), which is one symptom of wider anthropogenic ecological overshoot (Merz et al. Citation2023). Radical and rapid changes are required to address this, including changes to how and how much we travel (Marsden and Anable Citation2021). This is both challenging and a positive “opportunity for social reform” (Pelling Citation2010, 3). For example, in the city state of Singapore, combining autonomous driving with shared transport could reduce parked cars by 86%, creating space for new housing, parks, pedestrian and public space (Kondor et al. Citation2020).

However, in 2019, owners of semi-automated cars “drove an average of nearly 5,000 more miles per year” (Circella and Hardman Citation2022, 3), and many analysts envisage futures with innumerable individually owned and occupied fully automated cars, along with zero-occupancy cars sent to collect deliveries or get themselves cleaned, idly drive around or back home to avoid parking charges (Elliott, Kesselring, and Eugensson Citation2019). An autonomobility system that integrates autonomous vehicles into the material, infrastructural, cultural, and social folds of automobility may not engender a sustainable mobile third space, but a dystopian entrenchment of the automobility system and its overshoots (Sovacool et al. Citation2020).

The contradictions that these studies identify shape turbulent horizons of “hope, hype, and hell” (Kester et al. Citation2020, 88). But in a powerful critique, Cass and Katharina (Citation2020, 103) construct a vision of a very different autonomobility system centred on human autonomy, “freedom-focused, environmentally sustainable and socially just”. They “provocatively posit [this] autonomobility as an ideal for mobility studies and activism rather than the more standard goals of accessibility, equity or justice” (Calarco Citation2023, 81). Their autonomy is a relational freedom of self-determination and from compulsions of either mobility or immobility, which enables “the mutual flourishing of individuals and collectives” (Calarco Citation2023, 81). Calarco’s Reflections on Roadkill (Calarco Citation2023) push Cass and Manderscheid “to expand the future imaginary” to all living beings (p. 85). These contributions do not elaborate implications for AV, but by drawing out how post-capitalist economic models can help realise sustainable and just autonomobility, they do enable new visions for the socio-technical autonomobility system emerging around AV. This builds on economic theories that replace a focus on economic growth measured through Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with a focus on “human prosperity in a flourishing web of life”, for example through doughnut economics, where distributive and regenerative economic activity takes place within a safe and just space bounded by an ecological ceiling and a social foundation (Raworth Citation2017, 240). Cass and Katharina (Citation2020) and other mobilities analysts are beginning to show how societal innovation could shape what we would call doughnut mobilities.Footnote1 This includes commoning mobility (Nikolaeva et al. Citation2019), democratic reflections on “what mobility is for” (Cass and Katharina Citation2020, 106), operationalising degrowth in urban planning (Kaika et al. Citation2023; Kębłowski Citation2023), and a non-anthropocentric approach (Calarco Citation2023).

The intolerable risks of ecological overshoot and inequality require such tectonic cultural change, but for it to happen, some argue, humans need to “magically” become “indifferent to how well we do compared to others, and not really care about wealth and income” (Milanovic Citation2018, 4). Arguably, this is happening with social tipping points (Otto et al. Citation2020) and the gathering of a climate undercommons (Büscher Citation2024), but not fast enough. Many studies show that more “just and acceptable implementation” of change “requires taking account of the cultural meanings, emotional attachments and identities linked to particular landscapes and places” (Creutzig and Roy Citation2022, 82), and mobilities research has a rich seam of research on emotional attachments – from automotive emotions (Sheller Citation2004) and the driver-car (Dant Citation2004) to existential mobilities (Hage Citation2009) and emotional cartography (Nold Citation2018). Recent studies reveal mixed feelings about sustainability transition (Martiskainen and Sovacool Citation2021) as well as a deep embeddedness of such feelings in “specific regime[s] of orientations, attributions, values and norms” (Fraedrich Citation2021, 253). Our research develops this analysis by drawing on Raymond Williams’ study of cultural magic and structures of feeling (Williams Citation1961). This is challenging, because structures of feelings can be hard to define, trace and influence. In this paper, we report findings from exploratory investigations. Based on informed consent, we have used galvanic skin response (GSR) sensors as an instrument with twelve users of autonomous vehicles, non-users, engineers, and experts in China and the UK.Footnote2 We first motivate our focus on structures of feeling and methodology. Reporting findings, we discover “surrender” as a particularly turbulent structure of feeling. We discuss fissures in regimes of orientations, values and norms and the prospect of doughnut mobilities, concluding with reflections on applied mobilities research.

2. Why study structures of feeling?

This exploratory study is inspired by a back and forth between theory and listening to participants in collaborative mobilities research projects. Emotions have been an important, but under-analysed component of the first author’s research for many years (e.g. (Büscher Citation2017; Büscher et al. Citation2022; Gallego Méndez et al. Citation2023)). The second author’s PhD project on Autonomobility justice in China: a mobile methods study of how autonomous vehicles could shape future mobility systems explores how social inequalities are linked to urban transformations around autonomous vehicles (AVs) in China. It uses the sociological concept of “automobility system” which captures that “car culture” has many components, including the cultural object of the car/automobile, cultural values that link driving with freedom, urban design, and fossil fuel interests. The core argument is that societies are moving from automobility to “autonomobility”. The research extends research on “mobility justice” (Sheller Citation2018) and examines how autonomobility could make some citizens’ lives better or worse. Pilot research has revealed strong emotions, and this shared interest created an opportunity to collaborate on a small joint project to explore how one might research autonomobile emotions, which is what we report upon here.

We will describe how we have sought to study structures of feeling in more detail, but first it is important to explain why they are important to study. Listening to our participants, we can see how many highlight an intriguing turbulence of feelings. When examining his GSR plot, for example, Chengqi observes that the wiggly curve () captures mixed feelings:

the first [emotion] is that there is no pleasure of driving, right? The second is worried. … Surrendering one’s life to a machine … makes me a bit worried. It is a little uncomfortable at the beginning, but it feels better over time. … I mean, if safety were manageable, I would be okay with this driverless car.

Chengqi incongruously contrasts “surrendering one’s life to a machine” with being “a bit worried”, a loss of pleasure, and an expectation that, if safety could be ensured, a slow process of acceptance would naturally follow. This is a typical example from our study. Many participants also eagerly reflect on the sources of their emotions:

There is no denying that self-driving will become a main trend in the whole transportation system, … We as humans must catch up with the development of society. If not, we will be shifted out. … I trust our government, who allow AV to run in our city. The government never put their people in danger.

Other participants are more ambivalent:

I don’t know why- but I can see Google adopting self-driving Streetview cars, and for some reason I trust?(hesitant intonation) that [pause] but yeah. I am not sure, why would that be? … it all seems like a well integrated platform … if anyone would do it right probably they would, [pause]right in terms of the technology rather than ethics, but yeah hh.hhehe it would work.hh.hhe.

We start with these excerpts from our participants’ narratives of their GSR plots, because they highlight why insights into autonomobile emotions are interesting and important. Like many participants in this study, Chengqi, Sujie, and Alessia reflect on the capacity of governments or corporations to steer a safe, good course. They query the wisdom of surrender, progress, the ethics of innovation. But they also take some emotions for granted: a sense of pleasure and control, inevitable progress. These feelings rarely prompt reflections and their tacit cultural (re-)production of structures of feeling plays a critical part in “the ‘social’ definition of culture” (Williams Citation1961, 41).

In his book The Long Revolution, Williams shows that structures of feeling are pivotal in the long struggle for equality, freedom, democracy, social and ecological justice. He defines them as “a particular sense of life, a particular community of experience hardly needing expression, through which the characteristics of our way of life that an external analyst could describe are in some way passed” (Williams Citation1961, 48). Williams argues that examining structures of feeling provides important understanding of how social characteristics are produced and, importantly, how they change. To give an example, Williams unpacks how the emerging industrial society dealt with key contradictions of the era, such as the axiom that “success follow[s] effort” clashing with a reality where “[d]ebt and ruin haunt this apparently confident world” (p. 65). Structures of feeling tragically saw much of contemporary fiction employ what Williams calls cultural “magic” to “postpone the conflict” (p. 65). For the many heroes and heroines experiencing poverty and ruin in popular novels, unexpected “legacies, at the crucial moment, turn up from almost anywhere”, changing their fortunes (p. 66). These magic ways of cheating the system are “dissenting from the social character”, but they remain “bound by the structure of feeling”, working out their protagonists’ destinies “within the system” (p. 67). In contrast, Williams argues, the Brontë’s and Dickens capture the “personal and social reality of the system” (p. 68) with such intensity that they take “the work right outside the ordinary structures of feeling, and teach[] a new feeling” (p. 69). They highlight the “deadlocks and unsolved problems of the society, often admitted to consciousness for the first time” (p. 69); and examples of such transgressive “creative activities are to be found, not only in art, but … in industry and engineering, … new kinds of institutions” and everyday life (Williams Citation1961, 70–71). They paved the way for a new phase of capitalism shaped by more social solidarity and welfare.

Today, works of fiction (e.g. The Ministry for the Future (Stanley Robinson Citation2020)), art, and science (e.g. Raworth Citation2017), as well as new laws, like the Welsh Well-being of Future Generations Act (Davidson Citation2020), make the deadlocks of ecological overshoot stand out with similar intensity, teaching us new feelings of interdependence, opening up two paths. On the one hand, such efforts to change structures of feeling are drowned by a “magic system” (Williams Citation1960) of advertising and neoliberal ideology. For Williams, that system is magic, because it feeds on the same contradictions of the human condition, but offers only consumption as a solution. The system has been perfected over decades, gathering momentum when Edward Bernays, Sigmund Freud’s nephew, utilised psychoanalysis “to develop techniques for widespread behavioural manipulation” (Merz et al. Citation2023, 8). It blocks awareness that many people’s “needs are social” and ecological (Williams Citation1960, 29). Malene Freudendal-Pedersen powerfully documents how this magic suppresses feelings of interdependent autonomy today. She traces how, faced with the “enormous task” of addressing the unsustainability of automobility and the systemic deadlocks of high-carbon mobile lives, people use effectively self-harming “structural stories” to manage the cognitive dissonance of inaction (Freudendal-Pedersen Citation2016, 33). A structural story is “used to make an apparent rationale behind … the choices we make in everyday life, and functions as a guide for specific actions” (p. 34). The most powerful structural story – relentlessly advertised – suggests that “more mobility gives more freedom” (p. 42), and Freudendal-Pedersen shows how it perpetuates high-carbon mobilities in everyday life in Denmark, in resonance with ideologies of individual freedom that are globally promoted and key causes of ecological overshoot (Merz et al. Citation2023; Raworth Citation2017).

On the other hand, some structural stories break through these ideologies. When Freudendal-Pedersen asked her participants which mode of transport made them feel most free, contradictory responses suggest that structures of feeling close to Cass and Katharina’s (Citation2020) autonomobility are forged in everyday discourse:

… if I sit in rush-hour traffic in the car, then I’m not free, I feel more free when I bike past all of them.

It is, for sure, community which creates freedom. (p.84)

Freudendal-Pedersen acknowledges that these alternative stories are “the exception rather than the rule” (p. 84). However, she argues that applied mobilities research can create “communities where social learning is possible” (p. 139).

Like Freudendal-Pedersen, we have organised many collaborative research projects that bring citizens, non-governmental organisations, and policy-makers together to develop alternative visions, policies, and infrastructures for mobility (Büscher Citation2017; Büscher et al. Citation2022, Citation2023; Gallego Méndez et al. Citation2023). These encounters do nurture new structural stories, but often end with questions about how to achieve traction beyond those present. Global surveys like the Lloyd’s Register World Risk Poll find that 67% of people in 150 countries, including China and the UK, view climate change as a threat to their country (Lloyd’s Register Foundation Citation2022). Some analysts argue that leveraging this concern for change is a matter of recalibrating the magic system of advertising and marketing to new norms and values (Merz et al. Citation2023). But when the existing system grants the richest 1% nearly twice as much wealth as the 99% (Oxfam Citation2023), powerful vested interests are stacked against such recalibration. For example, ExxonMobile knew from their own research in the 1970s, that the extraction of fossil fuels would cause “potentially catastrophic” climate change (Supran, Rahmstorf, and Oreskes Citation2023, 1). They did not develop alternative energy solutions, but launched a “public deception campaign” designed to delay climate action (Supran, Rahmstorf, and Oreskes Citation2023, 1). More than 50 years later, the 198 countries in the United Nations Climate Change Convention recognise that there is no credible pathway to 1.5°C (UN Citation2022), and yet, “the largest expenditure” on political influence by “industries associated with the production and consumption of fossil fuels” is “on advertising and promotion”, a multi-billion U.S. dollar investment that has “played a key role in thwarting government attempts to implement climate policies” (Brulle and Downie Citation2022, 10).

Thus, in terms of public concern, a social tipping point, a “point when a certain belief, behavior, or technology, spreads from a minor tendency to a major practice” (Otto et al. Citation2020, 2356) may have been reached. Social tipping has radically changed the world before, for example with the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, and the internet, but is this happening now? Otto et al. consider how social movements like #FridaysForFuture are “causing ‘irritations’ in personal worldviews” that “might be changing peoples’ norms and values” from the bottom up (p. 2361). AV are a potential setting for such changing structures of feeling, but how to study them?

3. How to study structures of feeling?

To comprehensively track how the social characteristics of an era change in the day to day of culture, one would have to examine “evidence from ‘all the elements in the general organization’ of a society” (Kleese Citation2021, 22). This is an impossible task and, like Williams himself, many analysts see literature and art “as a specific cultural mode that mediates human thought” (Kleese Citation2021, 23), and use it to produce powerful insights. However, one of Williams’ intentions was to democratise culture through “redistribution of cultural authority”, and granting artists “a privileged role” makes such democratisation difficult (Middleton Citation2020, 4). For our study we used purposive and convenience sampling to find people with different experiences related to AV. The study takes advantage of the fact that we are based in the UK and China, respectively. While the UK ranks 9th on the Autonomous vehicle readiness index (KPMG Citation2020), and China 20th, many cities in China are running state-approved commercial AV trials with “robo-taxis” and buses – bookable through an app. Current examples include the commercial district of Dalian city, a famous resort and tourist city, or the Winter Olympic village in the Shijingshan area of Beijing. The trial sites include pick-up areas and platforms, and the company that runs most AV trials, Baidu, is in liaison with the relevant Department of Transport officials. Through pilot interviews and observations for her PhD, the second author is in contact with a range of different kinds of stakeholders, including passengers using AV, engineers and safety supervisors at Baidu, experts in different fields, as well as people who had not heard of the trials and do not use AV (henceforth non-users). Through a call for participation from these contacts, we recruited eight different participants (). The small number is proportionate to the size of AV trials. In general, AVs are very niche in the current transportation systems in China, far from being commonly used. AV trials are only conducted in fewer than 10 cities. Dalian is one of the leading cities to run AVs. However, within cities, too, AVs are tested in very limited areas. For example, Dalian City is testing AVs within 5 km of a commercial centre in one of the nine zones in the city. Few people live in this zone. Only those who often go to the commercial centre are likely to know about the AVs trials. Similarly, AVs are niche within Baidu company. There are only 5 developers in the Dalian Department of Baidu company to test AVs in Dalian City. However, China is the first country to run AV such extensive “robo-taxi” trials on public roads, as well as running a public consultation on the incorporation of AV into urban transport (China Ministry of Transport Citation2022), so the nature of engagement is different than in the UK and Europe, where more limited trials are underway, or the US, where robo-taxi trials started, but have been suspended following incidents. A cross-cultural comparison is beyond the remit of this research, but to complement insights from the Chinese participants with perspectives from other contexts, we included four non-user participants with different cultural backgrounds, forms of expertise and experience based in the UK. These were recruited from collagues of the first author. maps key information about our participants:

Table 1. List of Participants.

As shows, the seven male and five female participants are well-educated and in quite privileged positions. This resonates with studies of mobility justice in emerging AV markets, where the less privileged are likely to find themselves excluded or disadvantaged (Sparrow and Howard Citation2020). We want to counteract this trend by including a wider range of participants in future studies. However, for the study at hand, we can only note how this effect also manifests in research. One participant is a regular AV rider in Dalian City, the second author’s home city (Sujie), one agreed to undertake her first AV ride as part of this research (Jiayi), and one is a regular user of the autonomous Docklands Light Railway in London, which is quite different from the AV that are the focus of our study (Alejandro). Yifan, a project manager in one of Baidu’s trials and a safety supervisor who rides AV daily, combines expert knowledge with everyday experience. All other participants are non-users. Leyi, a professor of computer science, has significant insider knowledge about the computational complexity of AV, while John, who runs a small engineering company, has in-depth knowledge of AV technology. The expertise of the other non-users varies widely, ranging from home-making (Yuxi) to developing academic and business partnerships at a university (Louise). We cannot claim that assembling this group of participants is a major step towards democratising cultural analysis, but they are a diverse group that allows us to probe structures of feeling around AV and explore the potential of Bio Mapping.

But how to elicit their reflections on feelings? In her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Ahmed (Citation2014, 10) shows that “emotions are not ‘in’ either the individual or the social, but produce the very … boundaries that allow the individual and the social to be delineated as if they are objects”.Footnote4 This means that to understand emotions, we need to examine how they are articulated, both in the way they are expressed, and the way they construct material and political realities. Bruno Latour’s analysis of how perfumists learn to articulate sensory experiences of smell is useful here. Latour (Citation2004) observes how, through a carefully calibrated exercise of comparing ever more subtly different scents, trainee perfumists train their noses to register differences, and learn how to describe them.Footnote5 In the process, they and the scents, become different objects. Like an articulated lorry becomes an extended vehicle, the scent molecules’ landing on receptors in the trainees’ noses, and the trainees’ learning to register them, articulates new entities. As they become expert perfumists, the trainees are also able to name new sensory objects (and mix perfumes from them). Ahmed shows how emotions similarly articulate cultural, material, as well as political realities around ethnicity, and we are keen to explore these performative dynamics to understand how people discursively and physically articulate autonomobile realities.

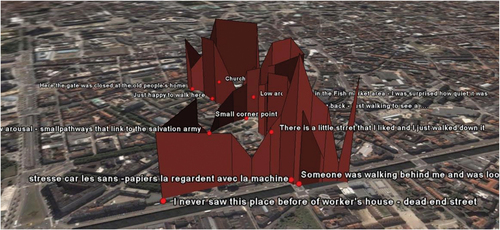

Christian Nold’s use of Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) sensors builds on Latour’s analysis to facilitate collaborative articulation in urban design. Emotions stimulate the human nervous system, which increases the electric conductivity of the skin, and GSR sensors measure fluctuations in this conductivity. They are often perceived as scientific instruments, and the most well-known use is in lie detectors, which are sometimes used in criminal investigations and involve suspects being asked a mix of questions about general facts and the crime at issue. It is often assumed that the jagged lines on the lie detector plotter can reveal whether a suspect is lying. However, Nold (Citation2018, 2) observes that “while it is easy to detect physiological arousal, it is difficult to associate it with a definitive cause and make it meaningful”. He argues that what matters to interrogators is “not what the machine is measuring, but how it can make the subject talk”, within “a larger performance of interrogation that consists of a coercive setting, an interrogator, a subject, the spectacle of measurement and the subject’s fear about what their body might disclose” (p. 2). By staging an entirely different performance designed to elicit articulations of embodied experiences of urban environments, Nold mis-appropriates this performance. He has organised hundreds of workshops in cities like San Francisco and Munich, where he gives participants GSR sensors combined with Global Positioning System (GPS) trackers, explaining the ambiguities of the performance. Participants then go for a walk and return for a collaborative workshop, where they are invited to narrate a visualisation of their personal GPS and GSR data, which look “like a spatialised cardiogram” ().

Figure 1. Bio Map made in Brussels. Reproduced with permission from (Nold Citation2018, 3).

Participants control what they relate and how it is recorded. They often remark that the Bio Mapping prompted them to notice phenomena they would have forgotten or “thought too insignificant to share” Nold (Citation2018, 4).

Institutionally powerful parties – urban planners, businesses and local authorities – often consider this information valuable, but hard to interpret. However, Nold and his collaborators’ efforts to translate are not always well received. In one town, even though the Bio Mapping “had been commissioned as a hybrid between an art project and a public consultation, the funders deemed the final map to be ‘too political to be art’ because it did not censor the local problems the residents had identified” (Nold Citation2018, 8). This prompted Nold to use Bio Mapping “itself as a site for alternative politics” of “autonomous public urbanism”, where inhabitants and institutional stakeholders “join the process as equal participants” as part of long-term collaboration to “build the city from the body upward” (Citation2018, 9).

Similar collaborative politics of autonomous mobility transformation are needed, and we have developed a methodology for societal readiness assessment (https://www.soradash.org/) to facilitate it, but the new structures of feeling that emerge from societal readiness assessment with stakeholders involved in decarbonisating transport are not rippling through society fast enough (Büscher et al. Citation2022, Citation2023; Mitchell Citation2023). Key factors blocking change are structures of feeling about mobile ways of life, and fears about change. The study at hand is an attempt to develop methodologies to understand structures of feeling, and support the articulation of new ones. We ask “How do people feel about passing control to autonomous vehicles? How do they feel about visions of smart mobility with AV?” and “How do they articulate their emotions?”. We invited the twelve participants in to a 30–60 minute individual session (), where they would:

Wear a GSR sensor by attaching two electrodes to two fingers on one hand.

Undertake an AV ride (Jiayi, Sujie) or watch a short video or slideshow, voicing their feelings out loud.

Watch recordings of the above and their GSR plot and narrate their emotions.

Figure 2. Bio Mapping set-up: (a) Jiayi wearing a GSR sensor during her first AV ride and (b) recording her ride; (c) Chengqi watching Jiayi’s ride with a GSR sensor; (d) Yuxi narrating her GSR plot, (e) Alessia watching a slideshow of AV and (f) narrating her GSR plot, (g) Alessia using her GSR plot as a prompt.

We have deliberately experimented with different versions of Bio Mapping. Jiayi and Sujie were asked to undertake a 10 min AV ride, record it, and narrate their GSR plot afterwards (). The other Chinese participants individually watched short excerpts from Jiayi and Sujie’s AV rides with the researcher (), and then narrated their GSR plot (d). In Lancaster, participants were invited to watch a slideshow of 29 images selected from Google image searches on “autonomous vehicles” (e), voicing their associations and narrating their GSR plot (f). John and Louise did a joint session. In all sessions, a collaborative analytical conversation naturally unfolded. Unlike Nold, we did not have the capacity to make an artistic combined visualisation of the AV ride videos or the slideshow and the GSR plot. This made for a comparatively more clumsy set-up, and because we wanted to explore what kinds of approaches different participants would take, we deliberately gave loose instructions to narrate their GSR plots. Some participants looked out for spikes and troughs and took them as prompts to articulate how they indicate emotional responses (e.g. Alessia (g)). Others took a more broadly reflective approach and voiced their emotional journey without reference to specific aspects of the plot. We have transcribed over seven hours of GSR narration, using AtlasTi to code findings. We note that important and very interesting differences in cultural context and individual backgrounds emerge from our analysis. In Louise and John’s discussion, an analytical discussion about this naturally emerged. However, otherwise, the research design does not facilitate analysis of this. It would be possible to draw out some trends and patterns (such as the fact that non-users seem more concerned, or that Chinese participants seem to show more trust in the state, while our other participants express (ambivalent) trust in corporations. However, in the spirit of democratising cultural analysis and working towards a methodology of co-creative analysis for autonomous mobility transformation, we plan to undertake analysis of cultural differences with participants in future research, e.g. by staging collaborative cross-cultural workshops and long-term collaborations between different stakeholders, similar to Nold’s autonomous urbanism approach. In our analysis here we trace key aspects of structures of feeling emerging from the participants’ responses.

4. Findings

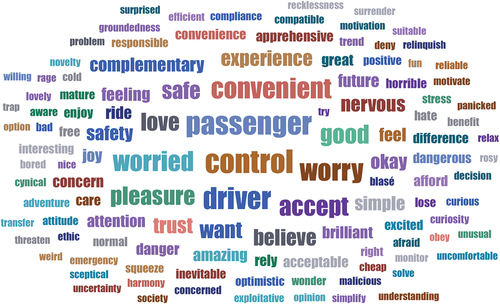

Our exploratory probing of autonomobile emotions reveals a kaleidoscope of feelings () as well as system-reproducing and alternative structural stories. We interweave our analysis with that voiced by the participants to trace emergent structures of feeling.

All participants consider some aspects of autonomous driving positive. This includes widening access “for people who struggle to use public transport or drive” (Alessia), assumptions that it “can alleviate congestion”, “is more objective” and “can make changes based on real-time traffic information” (Sihan), and is “probably safer than people driving” (Louise). Just under half are positively enthusiastic:

It is an all-round realization; it is only a matter of time. My attitude is positive because I am in this industry, and I want to see that day.

It is quite good, … very stable. … smooth. It is fun. … the speed was okay, too. The price is also suitable. … it is like taking a taxi but cheaper than a taxi.

… the [slideshow image] where you could read or do other stuff, that I really like, … I can’t wait for that to happen cause it’d be brilliant not to have to sit and stress about driving

What the government did allows the city to have a sustainable future and has benefit for the citizens. I guess the autonomous mobility systems will offer us a city with less congestion, less air pollution, more space to park. Parking space may even be unnecessary. The government may cancel the odd-even number policy. I have high expectations on the rosy vision of future intelligent autonomous mobility systems.

… it’s doing a great job just like we normal drivers. … When it comes to traffic lights, it feels like it’s taking the same route as we would. It’s right. I think it’s amazing. It’s incredible.

However, for most participants, enthusiasm is conditional. Jiayi expresses a widely shared feeling that she is “perfectly fine” with “the whole transferring rights to my car”, “if it’s convenient, efficient and, crucially, safe”. Many preconditions for acceptance imply concerns, but it is striking that while only Sihan uses the phrase “surrendering one’s life to a machine”, all participants report experiencing a form of surrender. Their feelings about this differ.

4.1. Sweet surrender

Most people impress feelings of “sweet surrender” onto the emerging socio-technical autonomobility system:

I think human autonomy will gradually be replaced by machine sovereignty … nowadays, many things rely on computers to replace human labour. Including some waiter robots in restaurants. … Actually, I think that’s going well. But the car, well, I think it’s going to be pretty good

I will happily give up control of the car. Because driving is more tiring. …

I would feel a little bit scared when I first started … I would … close my eyes. Think of myself as a passenger. …

However, many are puzzled by this “new sort of feeling”:

It is a new sort of feeling, in which there is a changing identity from driver to passenger. … driver and passenger at the same time.

It cannot be said that autonomous driving is a passenger’s feeling, it is a new feeling. … I may be less nervous and can better see the scenery outside

Jiayi articulates how attention can turn to the scenery, taking a photograph of a view during her ride ():

She qualifies the nature of her experience of surrender:

Nor can I be said to give up my autonomy. … it can only be said to be a shift. I am a driver and a passenger, I can experience two different identities, ah, this experience, it is also quite interesting. … it is more like a ride experience.

Jiayi’s notion of a “ride” surrenders autonomy only as a “shift” that affords convenience, extra time to work or relax, or admire the scenery. Most participants report not leaning into this form of surrender immediately: there is a structural story of a slow process of having to experience a ride for oneself, perhaps repeatedly, before accepting AV. For most, this surrender is sweet, but blind in terms of the functionality of the technology. Yifan, in contrast, experiences it through his knowledge and belief in the power of technology:

as a safety officer, I can trust this car completely. … It’s not going to have an accident, it’s not going to hit a person or a car. It won’t. It means that the safety officer absolutely trusts the system of the car. But I don’t trust the outside.

These narrations articulate objects such as technological progress, human frailties such as the propensity to tire, trustworthy governments, corporations, and technology as part of the emerging socio-technical autonomobility system. However, this is not (yet?) an “all-round realization”, and Yifan elaborates his mistrust of “the outside” thus:

sometimes there is a car, and you don’t feel right. … this car is going to swerve out. There might be a traffic accident. I’ll pre-empt that judgement … , put the brakes on. … That’s the idea. It’s complementary. The technology is getting more mature, … . [in fully automated vehicles] there’s no one in the car. … the technology doesn’t need safety supervisors to anticipate. It’s doing it all by itself. … people are clever and take shortcuts. … a person, who feels that there is no danger, he may … break the rules … . AVs do it in full compliance with the law. … traffic order will be better in the future, right? … You know it obeys all the rules, and it is all calculated. … Human drivers may be completely replaced in the future, but the background still needs to be maintained by humans.

He contrasts human risk-taking, his own superior judgement, technological sophistication, “clever” human rule-breaking, and machines bound to obey “all the rules” (made by humans), which almost evokes a reversal of surrender.Footnote6 He seems to flounder in these contradictions, and for others they fuel a desire for “no surrender”.

4.2. No surrender

Rejection of AV is focused on two structural stories:

handing over control to a machine or AI is not something I’m willing to do because I lose the joy of controlling my car. I think it can only be public transportation. I am not going to buy myself a driverless car and turn myself into a waste.

I wouldn’t be able to give up that hh.hh. sense of control (Alejandro)

Even though I believe in science, I don’t want to give up control of my car. (Leyi)

The first story posits that “driving enables unique pleasure”, resonant with Dant’s driver-car phenomenology, and many participants reflect on how the pleasure is gendered, conflicted, curtailed by urban congestion, and absent in AV. The second structural story takes us deeper into fissures in structures of feeling. It takes for granted that “humans can control complex dynamic processes like driving” better than machines. Yifan’s contradictions reverberate through Alejandro’s and Leyi’s articulations, rooted in the very ideology of human mastery that drives ecological overshoot. Its capacity to trap human reasoning/feeling is enormous, beyond the remit of our analysis here, but the participants’ reflections reveal interesting turbulences. Alejandro exemplifies this, as he reflects on the origins of his unease:

does the fact that you drive, does that give you a sense of safety or security or groundedness, so that would be me, for example, I wouldn’t be able to give up that hh.hh. sense of control, cause I drive, … I mean at the same time, I probably have been in those, there’s the DLR [automated light metro system] in London, they’ve been autonomous for a long time, … and yeah, you trust the system, but … in this case it’s introducing a vehicle within a setting that is not set to [it], so that’s very different, and I think there’s an element of forcing the technology then to create new dynamics, not all of which we probably agree with

Alejandro traces his inability to surrender control to his experience of driving, but like Yifan, he fears the unruly outside. They are not alone in this:

I kind of expect that in the future, the whole transport system will be intelligent and full of self-driving cars. If it’s just a pilot scheme, some are self-driving cars and some are driven by human beings, the humans may steal the lane from the self-driving cars or there may be some other trouble.

if part of it is human driving but part of it is autonomous driving, … this creates some psychological worries.

These participants prefer to suspend surrender until a “whole system” is operational. Some also explore solutions, similar to Sihan’s suggestion that AV should only be used for public transport:

If I go to an unfamiliar city, I may choose self-driving cars. The joy of driving becomes less important because I am going to be very purposeful about where I am going; … . But if I just want to drive, I do not want driverless cars.

Some people like the feeling of speed, but they’re going to be socialised in the future. If autonomous driving is widely used in big first-tier cities like Beijing … , it could cause other second- and third-tier cities to become a place of entertainment for people who like to drive.

But even with choice, socialisation, and spatial segregation, feelings of sweet surrender cannot fill the cracks in the structural story of control. The contradictions seem to feed a desire for technology to take over completely, whilst bemoaning a diffuse sense of loss (of human autonomy?). Even the most enthusiastic, like Yifan, have to juggle these troublesome incompatibilities between human and machine. For others, visions of surrender are decidedly dark.

4.3. Bitter-sweet surrender

Many participants’ narratives resent the powerless-ness of surrender:

The future of intelligent transport system is inevitable, unstoppable. I worry, not about safety, but about the fact that AI will replace more than 95% of jobs … What is the meaning of our existence after we are replaced by machines? If we can’t handle the relationship between humans and machines, our future will be a disaster.

Leyi, an expert in computation for autonomous machines, is the most deeply concerned, resigned to “inevitable, unstoppable” technological progress. Like Sihan, he fears that human capacities will turn to waste. Alessia, in turn, explores the widest range of concerns:

I see [state] control … this is because I lived [in China], … what’s being monitored?

… it saves you time and maybe kind of like when you are on a train you can do some work. … but do we want all of our time to be efficient?

I also hate Teslahehehehehaha … the recklessness of sort of knowing that something could go wrong and still launching the product

… if you are driving a car [yourself] you might get into an accident and then reflect back oh yeah I wasn’t really paying attention there … but [with AV] the thing that goes wrong is in a sphere that’s beyond your control, also beyond your understanding of how things work

[autonomous delivery] maybe less exploitative than Deliveroo[pause] … it potentially could be a positive thing, errm (.) but could lead to even more overconsumption and that type of interaction becoming more ubiquitous in our lives …

It’s like nobody’s walking hh.heehehe … probably all these people could have taken a train or some kind of collective transport system … if you’re a pedestrian … it’s probably safer … but it’s not a nice environment to be in

Resonant with these dark sides, Louise and John both critique the commercialisation of autonomobility, alternately considering corporate and consumer power:

Tesla and Google stand out to me, because they’re everything that is bad about AV … But then if people like Tesla and Google weren’t developing these systems, they wouldn’t happen

it’s horrible to say when you think about society, … most people will go “what will that cost?” Well, I’ll get a cheap one … and that’s about as far as they get

In conversation, John rejects Louise’s resigned surrender to corporate power. He argues that governments like Norway’s have successfully controlled these “horrible” societal dynamics and the magic system of high carbon mobility marketing by making sustainable solutions such as electric vehicles the cheapest consumer option. He has ideas that creatively resist surrender to a technocratic, capitalist autonomobility system, which chime with the other participants’ feelings.

4.4. Beyond surrender

Unlike the Chinese participants who can personally experience AV, Louise is doubtful about its realistic prospects:

although I believe that this is the future … , part of me is very cynical and given how slow we move on stuff like climate change and … from oil to renewables, I wonder if I’ll ever see this in my lifetime? I’d love to think that I will, but part of me thinks “will that really happen before I die?” You know?

Many participants stress the importance of seeking complementarity of human and machine autonomy:

Human and machine autonomy are complementary and compatible, not contradictory. (Sihan)

But we have to grasp a balance. Once we lose that balance, machine autonomy threatens our human autonomy (Leyi)

John’s response is practical – as CEO of a small engineering company, he is envisaging a fleet of small autonomous electric pods governed by a “Community Interest Company” (CIC), a legal structure for a non-charitable limited social enterprise designed to benefit the community:

I can see everyone having the opportunity to take enough income for it to be commercially viable. And I want to be clear about the word enough, because if you were to do it from a more capitalist business perspective, it could easily increase the profit margin, easily, and that’s why I want to set it up as a CIC and make sure it’s ring fenced from day one, cause I know what could happen, … Shell, BP and people will buy a stake in it, and … they’ll say we want to do targeted advertising, we want to do pay-per-use, we want to do peak time eight o’clock in the morning at this rate and two in the morning at that rate and all the other trappings of how we can squeeze money out of people … you know all the stuff that we’re all used to, it’s a horrible society to live in- one of us at some time is always being trapped out, you know …

I am not against capitalism, … but if we’re not careful with greed and the commercial machine that bolt on to this, and just do what it always does and squeeze every last bit out, that isn’t what society needs or wants- certainly isn’t what’s best for the environment, … I think we can do it … it’ll be a huge market, so they will come, but they can’t change the core values of what we’re trying to do.

Are these creative responses a sign of significant shifts in structures of feeling? Our study is too exploratory to know, but Bio Mapping has shown itself to be a powerful method for generating insight into structures of feeling, and autonomobility is an important site for the “social definition of culture” (Williams Citation1961, 41) at a time when ecological overshoot has become an existential threat to life.

5. Discussion

Urry projected that “by 2100 [steel and petroleum automobility] is inconceivable … [it] will disappear and become like a dinosaur, housed in museums” (Urry Citation2004, 36). This incredible social tipping point might actually happen sooner. However, it seems far less “an opportunity for social reform” than Pelling (Citation2010, 3) hoped for. Very few of the participants in our study prioritize sustainability or social justice, they do not list them as conditions for acceptance of socio-technical autonomobility. While some see autonomous vehicles best used as public transport, most value the personal convenience, freedom, and comfort of an autonomobility system that entrenches the values and norms of automobility. It would seem that Urry was right there, too, when he prognosed that public mobility has been “irreversibly lost because of the self-expanding character of the car system that has produced and necessitated individualized mobility” (Urry Citation2004, 36). The participants in our study – despite their being educated and privileged – see themselves as helpless faced with siren calls of a sweet surrender, “inevitable” progress, and the indefatigably rule-following machine; they have swallowed ideologies of a good life of convenience, efficiency, safety (more or less) hook, line, and sinker. Those who query it are hardly becoming magically indifferent to the lure of the magic system, albeit desperate to balance human autonomy against machine autonomy and the “horrible” commercial machine that drives greed and social and environmental exploitation. Raworth’s doughnut economy is a powerful alternative story that could amplify these feelings. Human activity currently overshoots six out of nine planetary boundaries, pushing Earth “well outside of the safe operating space for humanity” (Richardson et al. Citation2023, 1). At the same time, inequality is deadly: “[t]he emissions of the super-rich 1% in 2019 are enough to cause 1.3 million excess deaths due to heat” (Oxfam et al. Citation2023, 22). Raworth addresses both crises by explaining how the economy actually does and could work differently. She introduces the idea of a “safe operating space”, bounded by a social foundation and an ecological ceiling. Her concepts are being implemented by almost 30 cities and regions, including Portland, Toronto, Mexico City, Amsterdam, and Barcelona, who use them to develop policies, including transport and mobility plans.Footnote7 But doughnut economics is currently a sedentary concept, assuming that if people have the bases for human flourishing in place, good life in harmony with nature is possible.

Mobilising doughnut economics with the analytical orientations of the mobilities paradigm could serve the more ambitious aim of buen vivir (roughly translated as living well) (Kothari et al. Citation2019). Moving beyond “the good life” promoted by the magic system towards buen vivir is important, and we could work towards a more mobile doughnut economics by incorporating our participants’ calls for mobile pleasure and joy, a meaningful existence, liveable environments, control, and non-exploitative community business models as aspects of non-anthropocentric autonomy requirements for living well. To drive this, studies of the constitutive role of mobilities, blocked movements, and immobilities for a safe operating space for humanity and social reform to re-balance them are needed.

Our study was designed to explore the potential of Bio Mapping for this endeavour, firstly, to generate a deeper understanding of changing structures of feeling around autonomobility, and, secondly, to support an alternative politics of autonomous mobility transformation. There are many limitations. In terms of the empirical analysis, more could be done through a fuller discourse analysis, also focusing on aspects we have not addressed at all, such as gender, which many of the Chinese participants mention. We could consider the participants’ background more, and explore how it influences the narrations of their feelings, as well as expanding the number and diversity of participants. In terms of Bio Mapping as a process of alternative autonomous politics, it would be good to orchestrate performances where more and more diverse ordinary citizens, institutional actors, designers, corporations (including AI and lithium mining companies), communities, and other stakeholders involved in, or affected by, autonomobility systems could come together on an equal footing to build a new mobility system from heart, body and soul upwards. This would involve workshops, enabling co-creative analysis and facilitating long-term collaborations with processes for integrating insights into planning and design, and processes for accountability.

6. Conclusion

Our study cracks open a window onto changing structures of feeling on autonomobility, sustainability, and social justice. We are in search of footholds for the tectonic cultural change towards non-anthropocentric autonomobility needed to address the intolerable risks of ecological overshoot. What we find are hairline fissures in a socio-technical autonomobility system hell-bent on entrenching individualized automobility. Most participants in our exploratory study are perturbed by the relationship between human and machine autonomy, and the many dark sides of autonomous driving, from state surveillance to the prospect of meaningless existence. But they are still seeking cultural magic to sustain the good life rather than social reform or tipping towards buen vivir. There is little sign of a hunger for democratic debate, commoning, operationalising degrowth, or non-anthropocentric autonomy. This is not a hopeful picture. With Merz et al, we blame the magic system of advertising and marketing. However, behind the magic system are vested interests and power (Oxfam et al. Citation2023; Provost and Kennard Citation2023; Supran, Rahmstorf, and Oreskes Citation2023). Applied mobilities research could help leverage social tipping by investigating the relationship between the 1% and the 99%. How are structures of feeling supporting the secret and not so secret mobilities of money, information, and influence to the super-rich, and the inertia of this system? How could it be challenged? What mobile methods could support a politics of autonomous mobility transformation? For us, this would be normative research that deepens and multiplies the fissures in structures of feelings, perhaps by joining the “school of politics” that operates at grassroots level in many countries (Barbas and Postill Citation2017, 646). But to mobilise and articulate doughnut mobilities, mobile methods like Bio Mapping also need to change structures of feeling amongst the 1%, and engage them in articulating the sweet promise of buen vivir inside the doughnut. We do not know how to facilitate this, but consider Bio Mapping as a performance of such articulation a promising approach.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the participants for their contributions, the editors of this journal for a truly inspiring conference. We are grateful to our anonymous reviewers and our colleagues in the DecarboN8 (UK EPSRC Energy Programme, grant agreement EP/S032002/1) and GCRF-funded Gridding Equitable Urban Futures in Areas of Transition (GREAT) projects for their insightful suggestions on previous drafts of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We thank Keith Mitchell for inspiring the idea of doughnut mobilities in the context of our collaboration on the Stantec Bridging the Gap report (Mitchell Citation2023).

2. The research was approved by Lancaster University’s Research Ethics Committee FASSLUMS-2022–0959-RECR-3.

3. We use pseudonyms. All Chinese quotes have been translated by Fei Yu.

4. We use the terms “feelings” and “emotions” interchangeably.

5. Latour is inspired by Geneviève Teil’s ethnography.

6. We do not know whether the AV systems are equipped with machine learning that would incorporate corrective input from safety supervisor’s braking into the driving model.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. NED-New edition, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Barbas, A., and J. Postill. 2017. “Communication Activism As a School of Politics: Lessons from Spain’s Indignados Movement.” Journal of Communication 67(5):646–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12321.

- Brulle, R., and C. Downie. 2022. “Following the Money: Trade Associations, Political Activity and Climate Change.” Climatic Change 175 (3–4): 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03466-0.

- Büscher, M. 2017. “The Mobile Utopia Experiment.” In Mobile Utopia: Art and Experiments. Exhibition Catalogue, edited by J. Southern, E. Rose, and L. O’Keeffe, 12–18. http://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/89847/1/AMCatalogue_inners_lok.pdf.

- Büscher, M. 2024. “Mobile Politics, Media, Methods: A Climate Undercommons?” In The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media, edited by G. Goggin and L. Hjorth. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Büscher, M., J. Clark, R. Colderley, A. Kirkbride, J. Larty, S. McCulloch, E. Moody, et al. 2022. “Cumbria 2037: Decarbonising Mobility Futures”. DecarboN8 Research Network. https://issuu.com/niftyfoxcreative/docs/decarbon8_cumbria.

- Büscher, M., C. Cronshaw, A. Kirkbride, and N. Spurling. 2023. “Making Response-Ability: Societal Readiness Assessment for Sustainability Governance.” Sustainability 15 (6): 5140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065140.

- Calarco, M. 2023. Reflections on Roadkill Between Mobility Studies and Animal Studies: Altermobilities. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-30578-8.

- Cass, N., and K. Manderscheid. 2020. “The Autonomobility System. Mobility Justice and Freedom Under Sustainability.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 101–115. London: Routledge.

- China Ministry of Transport. 2022. “Notice on Public Comments on the ‘Guidelines for Transportation Safety Services for Autonomous Vehicles (Trial)’ (Draft for Comment)-Government Information Disclosure-Ministry of Transport”. https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/ysfws/202208/t20220808_3662374.html.

- Circella, G., and S. Hardman. 2022. “Driverless Cars Won’t Be Good for the Environment if They Lead to More Auto Use.” The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/driverless-cars-wont-be-good-for-the-environment-if-they-lead-to-more-auto-use-173819.

- Creutzig, F., and J. Roy. 2022. “Chapter 5: Demand, Services and Social Aspects of Mitigation.” In IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, by IPCC. IPCC. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FinalDraft_Chapter05.pdf.

- Dant, T. 2004. “The Driver-Car.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (4): 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046061.

- Davidson, J. 2020. #futuregen: Lessons from a Small Country. London: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Elliott, A., S. Kesselring, and A. Eugensson. 2019. “In the End, it Is Up to the Individual.” Applied Mobilities 4 (2): 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2019.1626047.

- Fraedrich, E. 2021. “How Collective Frames of Orientation Toward Automobile Practices Provide Hints for a Future with Autonomous Vehicles.” Applied Mobilities 6 (3): 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2018.1501198.

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M. 2016. Mobility in Daily Life: Between Freedom and Unfreedom. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315595764.

- Fulton, L. M. 2018. “Three Revolutions in Urban Passenger Travel.” Joule 2 (4): 575–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2018.03.005.

- Gallego Méndez, J., L. M. García-Moreno, Á. María Franco-Calderón, J. Murillo-Hoyos, and C. Jaramillo Molina. ‘Populab Policy Briefs’. 2023. https://populab.correounivalle.edu.co/recursos/policy-briefs.

- Hage, G. 2009. “Waiting Out the Crisis: On Stuckedness and Governmentality.” In Waiting, edited by G. Hage, 97–106. Victoria: Melbourne University Press.

- IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022 Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Frequently Asked Questions. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/faqs/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FAQ-Brochure.pdf.

- Kaika, M., A. Varvarousis, F. Demaria, and H. March. 2023. “Urbanizing Degrowth: Five Steps Towards a Radical Spatial Degrowth Agenda for Planning in the Face of Climate Emergency.” Urban Studies 60 (7): 1191–1211. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231162234.

- Kębłowski, W. 2023. “Degrowth Is Coming to Town: What Can it Learn from Critical Perspectives on Urban Transport?” Urban Studies 60 (7): 1249–1265. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221149825.

- Kester, J., B. K. Sovacool, L. Noel, and R. Zarazua de. 2020. “Between Hope, Hype, and Hell: Electric Mobility and the Interplay of Fear and Desire in Sustainability Transitions – ScienceDirect.” Environmental Innovations and Societal Transitions 35: 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.02.004.

- Kleese, N. E. 2021. ‘Beyond Urbanization: (Un)sustainable Geographies and Young People’s Literature – ProQuest’. University of Minnesota. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.proquest.com/openview/2f02ce1311eb945471a219423f733b37/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Kondor, D., P. Santi, D.-T. Le, X. Zhang, A. Millard-Ball, and C. Ratti. 2020. “Addressing the “Minimum Parking” Problem for On-Demand Mobility.” Scientific Reports 10 (1): 15885. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71867-1.

- Kothari, A., A. Salleh, A. Escobar, F. Demaria, and A. Acosta. 2019. Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary. New Dheli: Tulika Books.

- KPMG. 2020. ‘2020 Autonomous Vehicles Readiness Index’. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/es/pdf/2020/07/2020_KPMG_Autonomous_Vehicles_Readiness_Index.pdf.

- KPMG. 2022. ‘Levelling Up: China’s Race to an Autonomous Future’. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/cn/pdf/en/2022/06/special-report-on-autonomous-driving.pdf.

- Latour, B. 2004. “How to Talk About the Body? The Normative Dimension of Science Studies.” Body Society 10 (2/3): 205–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X04042943.

- Lloyd’s Register Foundation. 2022. ‘World Risk Poll 2021 – Report 1 a Changed World? Perceptions and Experiences of Risk in the Covid Age’. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://wrp.lrfoundation.org.uk/LRF_2021_report_risk-in-the-covid-age_online_version.pdf.

- Marsden, G., and J. Anable. 2021. “Behind the Targets? The Case for Coherence in a Multi-Scalar Approach to Carbon Action Plans in the Transport Sector.” Sustainability 13 (13): 7122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137122.

- Martiskainen, M., and B. K. Sovacool. 2021. “Mixed Feelings: A Review and Research Agenda for Emotions in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 40 (September): 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.023.

- Merz, J. J., P. Barnard, W. E. Rees, D. Smith, M. Maroni, C. J. Rhodes, J. H. Dederer, et al. 2023. “World Scientists’ Warning: The Behavioural Crisis Driving Ecological Overshoot.” Science Progress 106 (3): 00368504231201372. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504231201372.

- Middleton, S. 2020. “Raymond Williams’s “Structure of Feeling” and the Problem of Democratic Values in Britain 1938–1961.” Modern Intellectual History 17 (4): 1133–1161. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244318000537.

- Milanovic, B. 2018. “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist by Kate Raworth.” Brave New Europe (Blog). 25 June 2018. https://braveneweurope.com/doughnut-economics-seven-ways-to-think-like-a-21st-century-economist-by-kate-raworth.

- Mitchell, K. 2023. ‘Bridging the Gap: A Study of the Role of People and Place in Transport Decarbonisation.’ Stantec. https://www.stantec.com/uk/ideas/content/technical/2023/bridging-the-gap-understanding-uks-transport-decarbonisation-challenges.

- Nikolaeva, A., P. Adey, T. Cresswell, J. Yeonjae Lee, A. Nóvoa, and C. Temenos. 2019. “Commoning Mobility: Towards a New Politics of Mobility Transitions.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (2): 346–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12287.

- Nold, C. 2018. “Bio Mapping: How Can We Use Emotion to Articulate Cities?” Livingmaps Review 4 (March): 1–16.

- Otto, I. M., J. F. Donges, R. Cremades, A. Bhowmik, R. J. Hewitt, W. Lucht, J. Rockström, et al. 2020. “Social Tipping Dynamics for Stabilizing Earth’s Climate by 2050.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (5): 2354–2365. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900577117.

- Oxfam. 2023. ‘Survival of the Richest’. OXFAM. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/survival-richest.

- Oxfam, S. J., J. Dabi Persson, N. Dabi, and S. Acharya. 2023. Climate Equality: A Planet for the 99%. Oxfam. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/climate-equality-a-planet-for-the-99-621551/.

- Pelling, M. 2010. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. London: Routledge.

- Placek, M. 2022. “Global Autonomous Car Market Size.” Statista. 8 July 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/428692/projected-size-of-global-autonomous-vehicle-market-by-vehicle-type/.

- Provost, C., and M. Kennard. 2023. Silent Coup: How Corporations Overthrew Democracy. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Raworth, K. 2017. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. 1st ed. London: Cornerstone Digital.

- Richardson, K., W. Steffen, W. Lucht, J. Bendtsen, S. E. Cornell, J. F. Donges, M. Drüke, et al. 2023. “Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries.” Science Advances 9 (37): eadh2458. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh2458.

- Sheller, M. 2004. “Automotive Emotions: Feeling the Car.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (4): 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046068.

- Sheller, M. 2018. Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. London: Verso Books.

- Sovacool, B. K., N. Bergman, D. Hopkins, K. E. Jenkins, S. Hielscher, A. Goldthau, and B. Brossmann. 2020. “Imagining Sustainable Energy and Mobility Transitions: Valence, Temporality, and Radicalism in 38 Visions of a Low-Carbon Future.” Social Studies of Science 50 (4): 642–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312720915283.

- Sparrow, R., and M. Howard. 2020. “Make Way for the Wealthy? Autonomous Vehicles, Markets in Mobility, and Social Justice.” Mobilities 15 (4): 514–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1739832.

- Stanley Robinson, K. 2020. The Ministry for the Future. London: Orbit Books.

- Supran, G., S. Rahmstorf, and N. Oreskes. 2023. “Assessing ExxonMobil’s Global Warming Projections.” Science 379 (Online): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk0063.

- UN. 2022. “Climate Change: No ‘Credible Pathway’ to 1.5C Limit, UNEP Warns | UN News”. 27 October 2022. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/10/1129912.

- Urry, J. 2004. “The “System” of Automobility.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (4): 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046059.

- Williams, R. 1960. “The Magic System.” New Left Review 1/4 (July/August): 27–32. https://newleftreview.org/issues/i4/articles/raymond-williams-the-magic-system.

- Williams, R. 1961. The Long Revolution. London: Parthian Books.

- Yu, F. 2022. ‘Autonomobility Justice in China: A Mixed Methods Study of How Autonomous Vehicles Could Shape Future Mobility Systems’. Presented at the Intellectual Party, Lancaster University, Lancaster.