Abstract

Following calls to spatialize conjunctures, this article proposes and practices conjunctural mapping through a case study of the ongoing struggle at People’s Park in Berkeley, California. Although the method of conjunctural analysis enables and requires an investigation into the multiple forces at work in the production of hegemony, such analyses tend to focus on cultural, economic, political, and social (or horizontal) dimensions of winning or contesting consent, without necessarily locating the formations of these expressions at different (vertical) scales. What is the role of the geographical in producing and countering hegemony, and how do we consider questions of scale in a conjunctural analysis? We offer an example through a conjunctural mapping of People’s Park, where the University of California, Berkeley, and park defenders address pressures and seize opportunities at the scales of the subject, city, and state to respectively redevelop or protect the park. Mapping their multiple geographies reveals how the neoliberal crisis (in higher education, affordable housing, and public space) takes place and requires work at each scale in the struggle for hegemonic settlement. Spiraling outward and upward, cases like People’s Park show that conjunctures are best analyzed through consideration of local complexities and scale articulations.

根据动乱空间化的号召, 本文研究了美国加州伯克利人民公园的斗争, 提出并实践了动乱制图。尽管动乱分析能够也需要对霸权的众多产生因素进行研究, 但这些分析往往侧重于赢得或争取认同的文化、经济、政治和社会等(横向)层面, 没有在不同(纵向)尺度上确定这些表述的形成。空间在产生和反对霸权中的作用是什么?在动乱分析中, 我们如何考虑尺度问题?我们提供了人民公园的动乱制图实例。加州大学伯克利分校和公园维护者面对压力并抓住机会, 分别在公园、城市和州尺度上进行公园的重建或保护。通过对多个空间的制图, 我们揭示了存在于高等教育、经济适用房和公共空间的新自由主义危机如何产生, 认为有必要在霸权定居斗争中考虑各种尺度。诸如人民公园这种外向螺旋上升的案例表明, 动乱分析应当考虑局部复杂性和尺度表述。

Atendiendo reclamos para espacializar las coyunturas, este artículo propone y aplica el mapeo coyuntural por medio de un estudio de caso de la lucha actual en el People’s Park de Berkeley, California. Aunque el método de análisis coyuntural habilita y requiere una investigación de las múltiples fuerzas que obran en la producción de hegemonía, tales análisis tienden a enfocarse en las dimensiones culturales, económicas, políticas y sociales (u horizontales) de ganar o impugnar el consentimiento, sin localizar necesariamente las formaciones de estas expresiones a diferentes escalas (verticales). ¿Cuál es el papel de lo geográfico cuando se trata de producir o contrarrestar la hegemonía, y cómo consideramos las cuestiones de escala en un análisis coyuntural? Presentamos un ejemplo a través del mapeo coyuntural del People’s Park, donde la Universidad de California, Berkeley, y los defensores del parque abordan las presiones y toman las oportunidades a las escalas del sujeto, la ciudad y el estado para remodelar o proteger el parque, respectivamente. El mapeo de sus múltiples geografías revela cómo la crisis neoliberal (en la educación superior, la vivienda asequible y el espacio público) ocurre y demanda trabajo a cada escala en la lucha por el asentamiento hegemónico. En una espiral hacia afuera y hacia arriba, casos como el del People’s Park muestran que las coyunturas se analizan mejor a través de la consideración de las complejidades locales y las articulaciones a escala.

Palabras clave:

[A] primarily historical conceptualization must be spatialized: examining how a particular territorial conjuncture is shaped also by events elsewhere, how conjunctures concatenate across different geographical scales, and the variegated nature of conjunctural moments across space.

—Sheppard (Citation2022, 15)

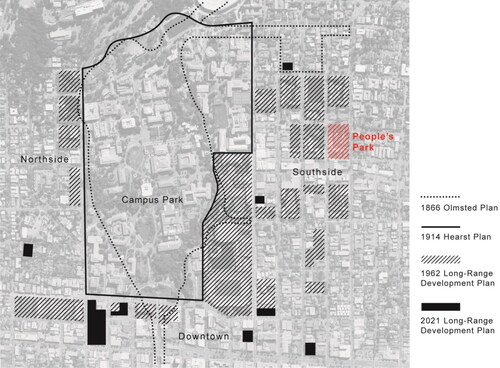

When construction crews and police officers arrived just after midnight on 3 August 2022—almost thirty-one years since they came to build volleyball courts (D. Mitchell Citation1995)—the redevelopment of People’s Park () in Berkeley, California, felt imminent. Unlike its previous attempts to control the site through primarily coercive strategies, such as evicting, fencing, clearing, and policing, the University of California, Berkeley (hereinafter UC Berkeley) has worked since 2018 to win consent for this project through persuasion at different scales. These efforts include “below-market student housing” for undergraduates, “a renewed green space that reinforces the site’s history” for the neighborhood, and a partnership with Berkeley to provide homes and services for unhoused people (UC Berkeley Citation2022d); such plans are said to address the region’s affordable housing crisis and the state’s growing student population (Public Affairs Citation2018). Allowed to proceed with construction by the Alameda County Superior Court after the project was stayed, UC Berkeley worked to reify its plans. Although establishing a construction site involved a return to coercion—with “uncanny echoes of Ronald Reagan’s use of state violence to try to reclaim the park” in 1969 (Berkeley Faculty Association Citation2022)—this attempt also included university representatives, the city’s Homeless Response Team, and gift cards for the owners of towed vehicles (Yelimeli Citation2022c). By midmorning, the perimeter of People’s Park was fenced and patrolled while workers cut down trees. As park defenders broke through the fences and blocked heavy equipment, however, UC Berkeley called off construction; the police retreated, the fence was removed, and defenders rallied (Prado Citation2022). Online messages of solidarity from those involved in similar struggles revealed a network of support across the state. The following day, the state’s First District Court of Appeals granted another stay on demolition and construction, pending a review of a California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) lawsuit by two neighborhood organizations (Yelimeli Citation2022b). Such efforts to protect People’s Park show how park defenders also work across scale.

Figure 1. People’s Park, September 2022. Source: Courtesy drone photography by Kevin Kunze, Kunze Productions.

This article considers how UC Berkeley and park defenders are respectively working to win consent and counter hegemonic production in the present neoliberal crisis—primarily in higher education (declining state funds, a shortage of student housing, growing enrollment), but also in relation to affordable housing and public space—by addressing and articulating different scales. Following so many false starts since UC Berkeley acquired lot 1875-2, near Telegraph Avenue and bounded by Haste Street, Bowditch Street, and Dwight Way, in 1967, what is it about the way that UC Berkeley is addressing this crisis at each scale that makes development now seem possible? Alternatively, how are park defenders addressing this crisis geographically to continue to protect People’s Park? We offer a conjunctural mapping of the contested project, paying particular attention to the pressures and opportunities at multiple scales and, in turn, how UC Berkeley is attempting to win consent and park defenders are countering its hegemonic efforts by working at the scales of the subject, city, and state. More than thirty years ago, Smith (Citation[1990] 2008) initiated an investigation into the production of scale, including the way that social movements extend the reach of their messages and expand their power through scale jumping, especially the move up from the local to broader geographical scales (Smith Citation1992; see also Herod Citation1997; Miller Citation2000). We show here how institutions and individuals use different registers of presentation and interpellation at multiple scales to win consent or allies to their cause. It is through the galvanization and articulation of these scales that UC Berkeley is working to forge a common sense about the necessity of developing a space that has withstood its more coercive efforts for more than five decades. At the same time, the ongoing protection of People’s Park similarly hinges on its defenders’ efforts to enact resistance across these same multiple scales.

We use this case study to advance an argument about the importance of thinking geographically when conducting conjunctural analysis, especially with respect to the ongoing relevance of scale—what we call conjunctural mapping. The method of conjunctural analysis requires an investigation into the multiple forces at work in the production of or resistance to hegemony amid a crisis. It takes the complexity of social phenomena and interactions as a starting point, eschewing single causes or primary contradictions in explanations of how ideology is naturalized and consent is won (Hall and Massey Citation2010; Clarke Citation2014; Gilbert Citation2019). Yet, despite the emphasis on complex fields of power, much of the earlier work on hegemonic production either ignored scalar distinctions or implicitly assumed the territorial container of the nation-state as a scalar backstop (K. Mitchell Citation2004; Sparke Citation2006). In a conversation between Hall and Massey (Citation2010), the necessity of thinking beyond the national scale arose—Hall noted, “hegemony in the Gramscian sense has to be rethought in a situation that goes beyond the national” (69). Despite this acknowledgment, the critical relevance of scale in conjunctural analysis often remains ignored (but see Peck Citation2017, Citation2023; Clarke Citation2018; Leitner and Sheppard Citation2020; Sheppard Citation2022). Analyses tend to focus on cultural, economic, political, and social (horizontal) forces in the production or contestation of consent, without adequately locating and investigating the different formations of these expressions at different (vertical) scales.

In what follows, we begin by discussing the method of conjunctural analysis, drawing on the formative theories of Hall and considering the link between conjunctural crises, hegemonic settlements, and multiple geographies. We then provide an overview of the conflict at People’s Park. Following this, we examine the forces at play at different scales, showing how People’s Park is imbricated in the present conjuncture. We also investigate UC Berkeley’s strategies for producing a hegemonized common sense and park defenders’ tactics to counter this hegemony. We conclude by considering how conjunctural mapping is vital to analyzing conjunctures and offering suggestions for future work with this method.

Conjunctural Mapping: Bringing Geography Back In

Gramsci (Citation1971) defined conjuncture in Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Although there is a large body of work on this concept, with some disagreement over interpretation, we rely on Carley’s (Citation2021) definition of conjuncture:

a moment where things (some of these things unforeseen or undetected) begin to converge in entirely unforeseen ways. … The conjuncture is a maelstrom; a chaotic mixture of different (social) forces … that, at the time it seems, can neither be controlled nor contained by politics as usual. Extant “elements” coming together in new ways. It gives rise to strange formations. It bursts forth. And it’s never a permanent state but, rather, a moment in time. (2–3)

Current theoretical work drawing on Gramsci’s conjuncture is often conducted in concert with attention to Hall’s reading of Gramsci; these are seen as formative of the Birmingham School and development of cultural studies (Hall Citation2016; Grossberg Citation2017; Carley Citation2021; Peck Citation2023). In his conversation with Massey, Hall defined a conjuncture as “a period during which the different social, political, economic and ideological contradictions that are at work in a society come together to give it a specific and distinctive shape” (Hall and Massey Citation2010, 57). Just as Gramsci identified the rise of fascism in Italy as a historical conjuncture, Hall analyzed the rise of neoliberalism in the United Kingdom during the Thatcher and New Labour years (Hall et al. Citation1978; Hall Citation1988). This period followed the conjunctural crisis of the 1970s and had a “specific and distinctive shape” resulting from the particular fusion of social forces coming together to form the hegemonic bloc Hall identified as Thatcherism. This bloc involved the articulation of multiple forces and institutions of civil society, especially racialized nationalist ideologies of the “organic unity of the English people” and ginned up militarism occasioned by the Falklands War (Hall Citation1988, 42). Because he was always attuned to power relations in society, Hall’s explanation of conjunctural analysis as a method emphasized “describing this complex field of power and consent, and looking at its different levels of expression—political, ideological, cultural and economic. It’s about trying to see how all of that is deployed in the form of power which ‘hegemony’ describes” (Hall and Massey Citation2010, 65). Both Hall and Massey were especially interested in the ideological dimension of these moments of fusion—that is, in the potential of the conjuncture to produce a hegemonized way of making sense of the crisis. Massey noted that this focus is about studying “the establishment of a particular kind of common sense” that is necessary in a hegemonic settlement of a crisis. For both, what followed the crisis of the welfare state in the 1970s was the most critical period to understand, as it led to the profound transformation of the United Kingdom and other Western industrialized societies. They used conjunctural analysis to answer the critical questions of why and how: Why did laissez-faire capitalism and neoliberal rationalities of governance become common sense then, and how was the crisis narrated or webs of belief sutured together to make this possible?

Following Gramsci (Citation1971), scholars have discussed and debated the process of what winning consent entails (e.g., Bourdieu Citation1977, Citation1988; Burawoy, Citation1979). For most working in cultural studies, winning consent involves “complex articulations of different social forces that do not necessarily correspond to simple class terms” (Hall Citation1988, 63). Hall’s elaboration of the concept of articulation (1988; see also Hall et al. Citation1978) drew on historical and contemporary phenomena to demonstrate the multiple forces that must come together in the assembly of hegemonic blocs. The production of hegemony inevitably involves a laborious, time-consuming, and ongoing process of alliance building and compromising that is always in process and never complete (cf. Clarke Citation2014, 120). Importantly, the process of building hegemony must be done in a manner that can “reach a level of unconsciousness where people aren’t aware that they’re speaking ideology at all. The ideology has become ‘naturalised,’ simply part of nature” (Hall and Massey Citation2010, 64; see also Eagleton Citation1991).

For cultural studies scholars like Grossberg (Citation2015), the importance of the empirical and the historical must be emphasized in any discussion of conjunctures and hegemonic production or resistance. It is the particularities that matter, informing and directing how to theorize more general processes and structures (Koivisto and Lahtinen Citation2012; Leitner and Sheppard Citation2020; Peck and Phillips Citation2020). As Hall (Citation1988) noted, the conjuncture must be conceptualized from the concrete—from the lived and produced social world. This is the link to the conjuncture as a political project. He wrote, “the object of the work is to always reproduce the concrete in thought—not to generate another good theory, but to give a better theorized account of concrete historical reality” (69–70). Nevertheless, the importance of the geographical was generally underemphasized in Hall’s work and remains primarily metaphorical in most literature on conjunctural analysis. For example, Gilbert (Citation2019) wrote, “The aim of conjunctural analysis is always to map a social territory, in order to identify possible sites of political intervention” (15, italics added). This conception of mapping a social territory, however, remains primarily descriptive rather than deeply cartographic—that is, it is viewed from an abstract theoretical and metaphorical perspective rather than through the mapping of actual places.

How can we render conjunctural analyses more spatial? How do cultural, economic, political, and social forces vary across but also connect places, and what is the role of the geographical in winning consent or countering hegemony? More specifically, how should we consider questions of scale in conjunctural analysis—that is, how can the conjuncture be analyzed vertically, reading “a social territory” in two dimensions rather than across a horizontal plane? Recent writings consider these questions. Camp (Citation2016) analyzed the “neoliberal carceral state” as a historical and geographical conjuncture, emerging in Los Angeles, Detroit, Attica, and New Orleans at specific moments. Leitner and Sheppard (Citation2020) offered a conjunctural interurban comparison of Jakarta and Bangalore, in which they argued for investigating the “events and processes happening in other places and at broader geographic scales” (492). Hart (Citation2020) considered South Africa, India, and the United States through a global conjunctural frame with “major turning points when interconnected forces at play at multiple levels and spatial scales in different regions of the world have come together” (242). In addition to these case studies, there are other calls to spatialize conjunctures. Asking “where the conjuncture takes place,” Clarke (Citation2018, 205) wrote, “the conjuncture articulates multiple spatial relations, such that politics come to play out on a terrain that combines and condenses multiples sites—the local (the deindustrialized city or region), the national, the regional (embodied in the EU, for example) and the global, whilst recognizing that all of these are folded into one another.” Most recently, Sheppard (Citation2022) explained how geography is well-suited to intervene in the present global conjuncture, which is “spatially heterogenous and multi-scalar” (17), and Peck (Citation2023) stated, “Relational comparison and conjunctural analysis each seek to explain, intervene, and theorize through the grounded but also structured contexts of place, positionality, and situation” (468).

As we follow this geographical turn, we cannot disregard the historical. The forces fusing in a conjuncture have distinct temporalities, and tracing these sedimented histories (of the distant or immediate past) to the present moment is key to any conjunctural analysis. Our aim is to think specifically about where these forces take place over time—where do they fuse to create historically sedimented social formations, and what are the opportunities for political intervention? In adding geography to history, it is also important to recall earlier contributions of geographic theory, particularly the multiscalar approach (Park Citation2005), sociospatial relations (Jessop, Brenner, and Jones Citation2008), and relational place-making (Pierce et al. Citation2011). Such concepts remind us that territories, places, scales, and networks are never discrete and tidy through time, but inevitably linked and messy. Just as conjunctural analysis requires us to consider the articulation of cultural, economic, political, and social forces, we must consider relationships between spaces and between geographies and temporalities. This is especially necessary when examining the “complex geographies of social movement networks” (Nicholls Citation2009, 79), or contentious politics, such as at People’s Park, in which participants “are enormously creative in cobbling together different spatial imaginaries and strategies on the fly” (Leitner, Sheppard, and Sziarto Citation2008, 158).

Our analysis of People’s Park builds on this contextualized, materialist, and grounded framing of the conjuncture with an emphasis on the why and the how of conjunctural analysis. In other words, we identify some of the multiple forces coming together at this specific moment in time at different yet interrelated scales, while highlighting the strategies of the university and tactics of park defenders to seize this moment and produce a hegemonized settlement with respect to the redevelopment or protection of People’s Park. We use the concrete historical and geographical particularities of the case to study up and theorize out (and back) in a dialectical, multiscalar investigation of the phenomenon. Simultaneously, we emphasize the importance of examining hegemonic production as a core element of conjunctural mapping—both as method and political project.

People’s Park

In this section, we trace the site’s acquisition, the park’s creation, and the ongoing conflict. The struggle over People’s Park follows decisions made in the 1950s to accommodate UC Berkeley’s growing enrollment and enact urban renewal in the city’s Southside (Brentano Citation1995). Expansions followed modernist design and planning principles—Allen (Citation2011) explained, “this generation espoused the ‘tower in the park’ model,” and it “abandoned the notion that building programs should be limited to the campus proper” (358). New university buildings, especially student housing, were to be constructed on sites in the city, as revealed in successive campus plans (). These plans document and envision, so although every mapped site did not necessarily belong to the university when a plan was published, UC Berkeley set its sights on them for eventual acquisition. As of the 1962 long-range development plan (LRDP), three Southside sites had been transformed into dormitory towers (Units 1, 2, and 3), whereas other sites—including lot 1875-2, which would become People’s Park—were identified, but not yet acquired. By simply marking a site for development, UC Berkeley effectively discouraged its improvement, helping produce a landscape that would require renewal (Allen Citation2011, 363).

Figure 2. University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) expansion, 1866 through 2021. Source: Map by authors, based on UC Berkeley plans. Image courtesy U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farm Production and Conservation, Geospatial Enterprise Operations.

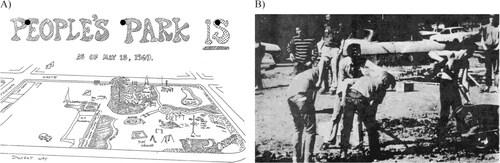

Figure 3. (A) Map and (B) photograph of People’s Park, 1969. Source: Courtesy Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley Free Church Collection.

According to Van der Ryn and Silverstein’s (Citation1967) analysis of UC Berkeley’s dorms, it was this very landscape of aging homes that was “prized by many students as symbols of warmth and free-living” (14). In contrast, new apartment buildings had “unreasonably high rents,” while the dormitory towers were “institutional” in terms of physical design and social regulations (Van der Ryn and Silverstein Citation1967, 18–19, 23). Unappealing to some students, the dorms had a vacancy rate of 10 percent by 1965. So, although lot 1875-2 was initially identified for student housing, it was acquired in 1967 for other reasons—purportedly, athletic fields (and eventual housing), but most likely to control the neighborhood’s “anti-authoritarian reputation” (Cash Citation2010, 8). Van der Ryn suggested that UC Berkeley Vice Chancellor Earl Cheit saw the Southside as “a threat to the stability of the University” (Cash Citation2010, 10), which echoes statements by other officials about drug use, sexual activity, radicals, and hippies (Dalzell Citation2019, 3–4; see also D. Mitchell Citation1992). Following the lot’s acquisition through eminent domain, houses were demolished (or moved) in less than a year. There was not enough funding to construct athletic fields, but the implicit goal was achieved, as University of California Regent Fred Dutton made explicit: “[t]he demolition was an intentional act against the hippie culture” (Dalzell Citation2019, 4).

Left with a muddy, informal parking lot for months, the neighborhood transformed the site into a park (). Scheer (Citation1969) described:

The park was allowed to develop for almost a month—from the first People’s Park Sunday, April 20th, until Bloody Thursday, May 15th. In that short time it bloomed and flourished. On weekends as many as 3000 people a day would come to plant flowers, shrubs and trees. A vegetable garden was created. Swings, slides and other play equipment—some homemade—were installed. (52)

How is UC Berkeley attempting to win consent for redevelopment in this moment, and in turn, how are park defenders resisting its hegemonic settlement? Their respective strategies and tactics address different scales, from the subject to the city to the state. The pressures and opportunities across these multiple geographies reveal some of the growing instabilities of neoliberalism as a hegemonic settlement—that is, a conjunctural crisis of neoliberalism. As we consider in the following sections, neoliberal policies have had cultural, economic, political, and social impacts on higher education, affordable housing, and public space, and its crisis is reified in People’s Park. The site also suggests how the struggle for a new (counter)hegemonic settlement is taking place. In this way, conjunctural mapping reveals how actors win consent and resist hegemony in two dimensions, both horizontally and vertically, as well as makes clear the opportunities for justice amid the broader crisis.

The Multiple Geographies of Winning Consent and Countering Hegemony

At People’s Park today, UC Berkeley and park defenders are working to produce a settlement from the neoliberal crisis that is concretized at the site. A conjunctural mapping of People’s Park reveals how these actors address pressures and seize opportunities at each scale to win consent or counter hegemony, respectively. This case study shows how cultural, economic, political, and social forces operate across multiple geographies, and it suggests that achieving any sort of settlement involves working across different scales. In the following sections, we consider how UC Berkeley and park defenders work at the scales of the subject, city, and state.

The Subject

In this section, we examine how UC Berkeley and park defenders work at the scale of the subject. For universities, neoliberal policies paired fewer public funds with a push to increase profits. Consequently, these institutions turned to other revenue sources, like tuition and fees, public–private partnerships, and philanthropy. Competing for these investments, from students (and parents), companies, or donors, universities must market themselves as “innovative, exciting, creative, and safe place[s] to live or to visit, to play and consume in,” as Harvey (Citation1989, 9) wrote of cities undergoing a similar shift from managerialism to entrepreneurialism. Marketing higher education in this way involves the built environment: describing a sense of place, constructing new “capital projects,” and drafting visionary plans for consuming subjects. Representations of People’s Park Housing, in the context of other university projects, reveal how UC Berkeley addresses the pressures of customer-investor subjects, and in turn, appeals to them to win consent.

While Discover Berkeley, a brochure for applicants, emphasizes the university’s “world of learning,” it also advertises a sense of place (UC Berkeley Citation2022b). Berkeley is a “community that sees you, hears you, and amplifies your voice”; it is “the birthplace of the Free Speech Movement” and “a melting pot of cultures and ideas.” An accompanying Web site describes local amenities and regional features. Housing options include Units 1, 2, and 3, in “the urban heart of Berkeley, close to local cafes, restaurants, and shops,” or Foothill and Stern, “nestled near the Berkeley Hills with ample access to green space” (UC Berkeley Citation2022c). A press release for Blackwell Hall, the newest residence, describes “patios, study rooms, bike racks, ping-pong tables, exercise machines and … million-dollar views of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco skyline” (Kane Citation2018). An even more luxurious residence, Anchor House, is under construction. Although this hall notably prioritizes transfer students and funds scholarships, it also intends to “set a new standard for student residential living” (UC Berkeley Citation2022a) as determined by the Helen Diller Family Foundation (enabled by Prometheus Real Estate Group, a developer of luxury apartments). Dinkelspiel (Citation2021b) of Berkeleyside described this standard:

Imagine a dormitory where every student has their own room lit up by large windows that let in the sun. There is a kitchen and built-in washer-dryer in every unit and at the end of the hall, the large living-room-like space has a massive TV. … Students can grow vegetables on a rooftop garden, their gardening knowledge augmented by a culinary library named after Alice Waters.

Although People’s Park Housing is not Anchor House—it is explicitly “not luxury housing,” but “quality housing” without private developers, operators, or profits (UC Berkeley Citation2022d)—its representations also appeal to consuming subjects. Apartments in several sizes feature kitchens and living areas, and a “grab-and-go market that emphasizes healthy foods” is located on the ground level. The building is in a “green community park space,” which includes “the pastoral Gardens + Grove with views to the neighboring historic buildings” and the Central Glade, “a sunny meadow with plantings, pathways, and passive use areas” (UC Berkeley Citation2022d). Renderings by LMS Architects and Hood Design Studio reveal these “revitalized” and “renewed” open spaces: lush, green landscapes with preserved trees and new native plantings, as well as diverse people who “gather, relax, and socialize.” These descriptions and illustrations, representing a space that is supposedly “open to all” and “for the enjoyment of all,” contrast with UC Berkeley’s representation of the existing park as unsafe: “[t]here is extensive criminal activity at People’s Park, much of it violent” (UC Berkeley Citation2022d). This statement is accompanied by infographics quantifying crimes in the park and links to news about murders and assaults there. Unlike the existing park, which is “filled with vegetation that obscures activities” and “isolated from the surrounding community,” the redevelopment is more easily surveilled:

The configuration of the new park will be thoughtfully designed to allow clear views and daylighting. Walkways and paths will bring pedestrians and residents of the new housing through the site, rather than around it. … The design of the new park space will focus on visibility throughout—no hidden corners. If places are visible to the public, crime is less likely to occur.

If UC Berkeley addresses consuming subjects, park defenders address creative subjects. For public spaces, neoliberal policies have taken the form of enclosures, such as privatization, programming, and surveillance. At People’s Park, previous plans sought to program space for whom and what the university deemed appropriate (D. Mitchell Citation1995, Citation2017), and the latest plan “allow[s] residents to view and monitor activities” (UC Berkeley Citation2022d). D. Mitchell (Citation1995) distinguished between this vision of public space—“planned, orderly, and safe,” where users are “comfortable, and they should not be driven away by unsightly homeless people or unsolicited political activity”—from a vision of public space as an “unconstrained space within which political movements can organize” (115). Park defenders maintain this latter vision as they contest redevelopment. This requires appeals to creative subjects who will not only protect People’s Park, but also live the site in alternative ways.

Such appeals are apparent in written and visual calls to action. After the events in August 2022, the research collective Left in the Bay (Citation2022) wrote, “[The park’s] continued existence proves something dangerous: you, too, can seize something from the most powerful people in town, make it into whatever you want, and hold it for half a century.” This statement echoes writings in the radical newspaper Slingshot—“[w]e demand direct involvement in creating the world and deciding how things should work in our community because these processes bring meaning to our lives” (Montigue and Stooge Citation2021)—and the Disorientation Guide, an alternative guide to the university written by students, alumni, and activists—“[f]lip the tables, make a lot of noise, don’t listen to anything they tell you! It’s all bullshit. Start getting organized, and build a militant movement to stop it” (Disorientation Crew Citation2021). In contrast to UC Berkeley’s descriptions and renderings, suggesting that people should fear the existing space or use the planned space as designed, social media posts by Defend People’s Park (@defendppark) invite people to produce the park. Its posts document artistic and environmental creations, request donations for those living there, advertise activities and events, and organize protection. For instance, during Disorientation Weekend, park defenders screened a movie, held a concert, and offered nonviolent direct action training, as well as collaborated on wrapping an abandoned backhoe as a gift for the university (Wymer Citation2022). Such activities maintain legacies of action in the park by the People’s Park Council, East Bay Food Not Bombs, and Berkeley Copwatch, which have continuously reproduced the space through rallies and marches, gardens and art, films and concerts, and mutual aid. These written and visual calls and their resulting actions reveal how park defenders appeal to creative subjects to contest the planned redevelopment, and more broadly, address neoliberal enclosures of public space.

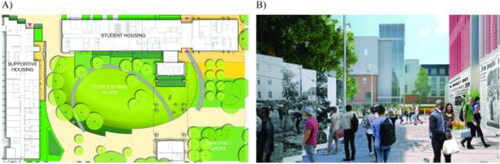

The contrast between consuming and creative subjects is exemplified in the respective ways that UC Berkeley and park defenders use the history of People’s Park. The redevelopment plans () include a “commemoration of the park and its history,” such as “a memorial walkway that mimics the path protestors walked in May 1969, murals or commemorative designs on the exterior of the buildings, displays of historic photos, and themed student housing floors around the topics of social justice, sustainability, and caring for the natural and human habitat” (UC Berkeley Citation2022d). A site plan suggests that “[t]he footprint of the gardens mimics the lot lines of houses that stood here from the early-1900s until the 1960s,” and a rendering shows a building clad in newspaper stories—“BIG BERKELEY RIOT” reads the San Francisco Chronicle—as well as panels with photographs of the park’s creation and a timeline etched into the ground. People are shown walking through this space and consuming its history. Notably, this plan is being coordinated by UC Berkeley Professor Walter Hood and his studio, which is known for its “artful landscapes for underserved communities and vulnerable cultural institutions” (“Hood Design Studio” Citation2020). The university emphasizes their involvement in the project. Prior to any physical construction, the photographs and timeline contribute to a particular historical narrative online, making a case that People’s Park is in decline and the growth of students and residents necessitates new housing. In this way, UC Berkeley is, in fact, saving the park: “The park was originally envisioned as an open, welcoming, and inclusive place—this project is consistent with the park’s past” (UC Berkeley Citation2022d). Park defenders reject this narrative and the representation of People’s Park as “history.” Harvey Smith of the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group (PPHDAG) argued, “The university proposes saving People’s Park by destroying it” (Señor Gigio Citation2022). For park defenders, UC Berkeley is not saving the site, but actively damaging it to necessitate redevelopment, as we further discuss later. Moreover, People’s Park is not history—according to the essay in Slingshot, “the park is an essential and vibrant place today, not just history to get memorialized in a plaque” (Montigue and Stooge Citation2021), and the People’s Park Council (Citation2022) maintains an online gallery showing how people continue to use the park. Although park defenders do share historical descriptions and photographs, it is to motivate action—that is, they recall history to encourage people to protect People’s Park today.

Figure 4. (A) Plan and (B) rendering for People’s Park Housing, 2022. Source: LMS Architects and Hood Design Studio for University of California, Berkeley.

In this section, we considered the ways in which UC Berkeley and park defenders appeal to subjects as they attempt to create a (counter)hegemonic settlement from the neoliberal pressures on higher education and in public spaces. As their words and visuals demonstrate, UC Berkeley addresses consuming subjects (who want a safe, if not luxurious, experience) and park defenders address creative subjects (who want to make a space of their own) to support or contest the redevelopment of People’s Park, respectively. In the following section, we continue this conjunctural mapping through considering how these actors address pressures and make opportunities at the city scale.

The City

We next examine how UC Berkeley and park supporters attempt to generate support for their causes at the scale of the city. Just as neoliberalism affects universities (and public spaces), such market-oriented policies and solutions, in conjunction with the wealth generated in nearby Silicon Valley, have made Berkeley (and the San Francisco Bay Area) particularly expensive, one of multiple real estate “hot spots” in California. As of mid-2023, Zillow valued homes in Berkeley at about $1.4 million on average, and it estimates rent for a one-bedroom apartment at $2,350 per month. Although neoliberal-supported and tech-related gentrification is partly responsible for these high prices throughout the city and region, the shortage of affordable housing is exacerbated by decades of “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) and libertarian “yes, in my backyard” (YIMBY) pressure by homeowners, organizations, and politicians against constructing low-income housing (Chapple Citation2017; McElroy and Szeto Citation2017; McNee and Pojani Citation2022). New student residences, as well as converted single-family homes, face similar opposition. The housing crisis in Berkeley was only made worse by COVID-19—prices rose in 2021, with bidding wars sometimes leading to sales of 50 percent to 100 percent over the asking price (White Citation2021). The number of people living in People’s Park also increased during this time, as they were protected by health guidelines against displacement. As UC Berkeley and park defenders address this housing crisis, their respective appeals reveal attempts to win consent and counter hegemony at the city scale.

The topography of housing in the city has produced unusual alliances, especially when it comes to People’s Park. Despite a historically progressive city government—working toward rent controls, affordable housing, and real estate fees, while challenging the state’s antitax movement (Barton Citation2012)—and recent antidisplacement activism by Mayor Jesse Arreguín—tweeting in March 2021, “We need more student housing, but it cannot happen by eliminating existing affordable housing. That is why I support the tenants of @save1921walnut to stop their eviction by the University”—the city and university are aligned on People’s Park (and Anchor House, which displaced the residents of 1921 Walnut Street). The City Council’s support of these housing projects was a toss-up: The city sued the university in June 2019 for failing to analyze the impact of increased enrollment (Dinkelspiel Citation2019), but then Councilmembers Rigel Robinson and Lori Droste and Mayor Arreguín (Citation2020) called for “a new People’s Park” in the San Francisco Chronicle. Arreguín’s support for the residents of 1921 Walnut Street seemed to indicate another shift, but in July 2021, the town–gown alliance was solidified through a deal between the city and university. According to a press release, Berkeley will provide city services, as well as “drop its litigation … [and] not challenge the upcoming 2021 LRDP and UC’s Anchor House and People’s Park housing projects,” in exchange for $82.64 million over the next sixteen years (City of Berkeley and UC Berkeley Citation2021). The City Council approved the agreement eight votes to one, followed by the UC Board of Regents when it approved the LRDP (Dinkelspiel Citation2021c). Through this economic incentive, UC Berkeley secured the city government’s support, which it emphasizes along with student surveys, other endorsements, and planning participants to present the redevelopment as a “win-win-win-win for the campus and the community” (UC Berkeley Citation2022d).

On the other side, the formation of park defenders is also unusual. Yelimeli (Citation2022b) of Berkeleyside identified three groups of defenders: (1) “an older generation of activists who aim to preserve the park’s 53-year-old history as a communal gathering space and home for counterculture movements”; (2) current UC Berkeley students interested in “land rights and services for homeless residents”; and (3) Defend People’s Park, a coalition calling for the land to be rematriated to Indigenous stewardship, permanent housing for park residents, and the abolition of UC Berkeley’s police department. Given these different motivations, the tactics of these groups vary, from lawsuits in county court to direct action in city streets. For example, immediately following the 2021 agreement between the city and university, Make UC a Good Neighbor (MUCGN) and PPHDAG asked the Alameda County Superior Court for an injunction because the City Council “decid[ed] to approve a settlement agreement in a closed door session.” In August 2021, they filed a CEQA lawsuit over the impacts of the LRDP, Anchor House, and People’s Park Housing, renewing the fight that the city dropped when it partnered with the university (Dinkelspiel Citation2021a). These lawsuits followed direct actions earlier in the year—in January, protestors pulled down a fence at People’s Park, carried it up Telegraph Avenue, and placed it on the steps of Sproul Hall (Suth Citation2021), and in April, protestors marched from 1921 Walnut Street to People’s Park, with rallies at each site for those being displaced (Morrison Citation2021). These varied tactics continue to stall the project, as was the case in August when direct action shut down construction and the lawsuit delayed it indefinitely. Motivated by different reasons and protesting in different ways—yet articulated together in their desire to protect People’s Park—this alliance of NIMBY activists, historic preservationists, antidisplacement organizers, and movements for Indigenous sovereignty and police abolition is successfully countering the city–university partnership.

In addition to forming such alliances, establishing (counter)hegemony at the scale of the city has both UC Berkeley and park defenders addressing the park’s unhoused residents (and the broader homelessness crisis). Since announcing the project, UC Berkeley has emphasized its intention to “make land available for the construction of permanent supportive housing for members of the city’s homeless population” (Public Affairs Citation2018). Its redevelopment plans call for 100 units of housing, the Sacred Rest Daytime Drop-in Center, a full-time social worker, and a new public restroom (UC Berkeley Citation2022d). In March 2022, the city and university also leased the Rodeway Inn for those presently living in People’s Park. According to Councilmember Robinson, “never before has a university invested so directly in alleviating homelessness in its host city” (Yelimeli Citation2022a).

Park defenders are suspicious of these efforts. For instance, in the documentary Random Acts of Nonconformity: Save People’s Park (Señor Gigio Citation2022), Smith argued:

[UC Berkeley] allowed people to camp here. And they played that as being the very benevolent institution that was concerned about people during COVID. Well, they also at the same time describe People’s Park as a horrible, dangerous place filled with very threatening people. So they’ve created an impression that People’s Park is a place not to come for many people in Berkeley.

In this section, we considered how UC Berkeley and park defenders work at the scale of the city through forming unusual alliances and supporting unhoused people. UC Berkeley has used economic incentives to win consent—it increased payments to the city, and it offered land and funds for permanent and temporary supportive housing and services. As an aside, it also provided “generous assistance packages” for those displaced from 1921 Walnut Street (UC Berkeley Citation2022a). Park defenders have embraced varied tactics in courts and on the streets to articulate a diversely motivated alliance that is stalling redevelopment, protecting the park, and supporting unhoused residents. In the next section, we complete our conjunctural mapping by considering how these actors address pressures and make appeals at the state scale.

The State (and Beyond)

The final scale of hegemonic struggle we examine is the scale of the state. As previously noted, state support for higher education, including in the University of California system, has declined over the last four decades, leading to tuition and fee increases for students. Student demographics have also shifted, with a far higher proportion of low-income, first-generation, and underrepresented students arriving on campuses (Newfield and Lye Citation2011; Newfield Citation2020; Hale, Mitchell, and Maurer Citation2021). In this context of high tuition, a larger and more diverse student population, and the lack of enough affordable (or student) housing, UC Berkeley is working to win consent to the development of People’s Park at the state scale (and beyond). A key strategy at this scale has been to leverage sympathy and support for students, who have largely borne the brunt of increasing costs and are struggling with high tuition rates and the inability to find affordable housing. One of the most tangible ways that UC Berkeley used this strategy has been through its public contestation of NIMBY efforts to stop the development of housing in the city. In each of its highly publicized responses to no-growth efforts to block housing, UC Berkeley has highlighted the plight of students.

An example of this strategy is the media relations campaign surrounding the use of CEQA by Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods. This organization repeatedly sued the university—including as part of the city’s lawsuit in June 2019—for failing to consider the environmental impact of increased student enrollment. As a result of a California Supreme Court decision on the lawsuit in March 2022, it appeared that the university would have to reduce admissions (Dinkelspiel Citation2022b). UC Berkeley’s formal response was swift: “This is devastating news for the thousands of students who have worked so hard for and have earned a seat in our fall 2022 class. Our fight on behalf of every one of these students continues” (Public Affairs Citation2022). Another statement reads, “a shadow has been cast over this year’s admissions cycle,” suggesting the court order could impact “the campus’s broad outreach efforts and its momentum in increasing diversity” (Gilmore Citation2022). In addition, social media aided UC Berkeley as users discussed the declining chances of acceptance, playing to the anxieties of students and parents. A letter about the enrollment freeze to prospective applicants from Olufemi Ogundele, the dean of undergraduate admissions—stating “at least 5,100 freshman and transfer students who would otherwise have been offered admission for fall 2022 would not receive such an offer”—was widely shared on Twitter, including by city councilmembers. Councilmember Terry Taplin’s (Citation2022) tweet reiterated the connection between the enrollment freeze and minoritized students: “How many thousands of diverse, marginalized students will receive this letter?”

As discussion continued, the link between the housing shortage, lawsuits by homeowners, and the impact on minoritized students became common sense. Although these impacts were avoided—state lawmakers “approved a legislative fix” within two weeks of the court’s decision (Zinshteyn Citation2022)—the narrative persisted, inevitably lending support to UC Berkeley’s new housing efforts, including at People’s Park. It is notable that the university and city announced their partnership “to aid unhoused people in People’s Park” during this time (Kell Citation2022), perhaps sensing that park defenders could not easily oppose the redevelopment in that moment. Beyond the local effect of this developing common sense, the narrative generated broader impact at the scale of the state. The governor and campus pointed to the economic benefits of the University of California system, such as being the state’s third-largest employer. These discourses and alliances, through the networking by students, alumni, administrators, and politicians, helped to shift consensus in favor of UC Berkeley’s (and the University of California system’s) right and indeed responsibility to build more student housing, including in contested situations involving NIMBY activists and antidisplacement organizers, namely People’s Park. This political consensus was manifested most concretely in September 2022, when Governor Gavin Newsom signed SB 886, state legislation exempting public university housing development projects from CEQA.

Although many park defenders claim to support more student housing, they argue People’s Park Housing is an exception, and they also work at the state scale to contest its development. Park defenders have used both CEQA and preservation to protect the park, despite their association with NIMBY homeowners. Several CEQA lawsuits, particularly that of MUCGN and PPHDAG, have successfully stalled construction (Dinkelspiel Citation2021a). By focusing on People’s Park Housing (and Anchor House), this lawsuit has been less controversial than that by Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods, even as they both challenge the environmental impact of the university’s new LRDP. Moreover, unlike those who oppose any new student housing, park defenders list several alternative building sites that could be developed, from parking lots to the chancellor’s residence. “UC has many sites they could develop into housing (they have 9 sites listed on their 2019 ‘opportunity sites’ document) but they are focusing on sites where activists gather and organize,” according to the Disorientation Guide (Citation2021). Park defenders have also worked to shift the discussion to the rising cost of student housing—the Disorientation Guide continues, “the plan was sold as much needed student housing. Never mind that the housing will be some of the most expensive student housing available, with no planned affordable units for low income students.” Indeed, these costs are rising: The cost for a single room (with a basic meal plan) for 2019–2020 was $19,350, which was projected to increase to $23,205 for 2023–2024 (Hutchinson Citation2023).

The narratives employed by park defenders thus attempt to counter the story of student distress with direct critiques of the university and its student housing plans and prices, at the same time pointing to the advantages of keeping the park intact. These benefits include the importance of preserving open space in what they represent as a dense area of the city, as well as the necessity of keeping existing trees and plants as an important factor in combating climate change. This is a critique of UC Berkeley, which despite the “environmentally friendly design” and open, green spaces in its plans, has only removed trees over the past decade—a visual that park defenders share. These proponents also note the value of the park as a magnet for tourists and hence a revenue generator for local businesses and the city. According to PPHDAG (Citation2022), the park draws tourists “from all parts of the globe” to see and learn more about what happened in Berkeley in the 1960s that made this city the heart of the free speech movement and California a key locus of the counterculture movement.

Indeed, perhaps the most direct and effective means of winning support for the park at the state scale (and beyond) is through historic preservation. People’s Park is heralded by its defenders in numerous quotes and writings as a place that “commemorate[s] the great social and cultural conflicts of the 60s” (PPHDAG Citation2021). It is a place that holds in its very soil and in the memories of those who struggled to build and protect it the essence of resistance to “the machine”—capitalism, ruthless development, and top-down systems of authority—and its very name conjures up a vital historical movement of the people, by the people, and for the people. Moreover, its success in resisting pressures to give in and give up for more than half a century has simultaneously created an almost fairy-tale myth of the power of the people to take space and hold onto it in the face of great pressure to acquiesce. This is most clear in the cartographies of solidarity mapped by those struggling for public space, both in the past—“from People’s Park to Tompkins Square: rise up, rise up, everywhere” (People’s Park Emergency Bulletin Citation1991)—and present—“24th St. Plaza in SF was reclaimed for the people in solidarity with People’s Park in Berkeley, Parker Elementary in Oakland, Echo Park in LA” (Defund SFPD Now Citation2022). Such significance is only further evinced by the addition of People’s Park to the National Register of Historic Places in May 2022 (Dinkelspiel Citation2022a).

This national designation, coming two months after state legislators undid the enrollment freeze, again shifted the prevailing political winds. Consequently, despite all the discourse against CEQA lawsuits in March 2022, the redevelopment of People’s Park was stalled by a CEQA lawsuit as of July 2023. All these efforts—lawsuits, sympathy, legislation, preservation, and solidarity—demonstrate how both UC Berkeley and park defenders work at the scale of the state (and beyond).

Conclusion

In the year since they blocked construction, park defenders maintained control of People’s Park. In January 2023, after heavy equipment was finally removed, activists opened a temporary warming center amid successive winter storms (Kwok Citation2023). In February, the First District Court of Appeals agreed with neighborhood organizations that UC Berkeley did not consider alternative sites for, nor the noise impacts of, the redevelopment project (Yelimeli Citation2023a). In April, people celebrated the anniversary of the park’s creation and mourned the recent death of cofounder Michael Delacour (Natera Citation2023). Nevertheless, the Supreme Court of California has agreed to hear UC Berkeley’s appeal, which is supported by briefs from the city and state. Proponents of the university’s position have also sought to delegitimize park defenders. Governor Newsom noted that “California cannot be held hostage by NIMBYs who weaponize CEQA to block student and affordable housing,” and according to Mayor Arreguín, the plaintiffs “used the homeless as a prop to support their campaign of obstruction” (Yelimeli Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

These recent events underscore the multiscalar character of conjunctural crises and articulated (counter)hegemonic settlements at People’s Park. Various pressures across several levels—including lack of affordable housing, struggles over public space, increased student enrollment, and enhanced student expectations—fused into a crisis and reopened the site to contestation. UC Berkeley attempted to settle this crisis through aesthetic changes, economic incentives, and affective appeals. At the subject scale, it enticed students with comfortable new residences and a safe park; at the city scale, it offered financial incentives to the city of Berkeley and housing to park residents; and at the state scale (and beyond), it generated sympathy during its (brief) enrollment freeze by decrying the potential impact on an increasingly diverse student body. Through differentially scaled (vertical) strategies such as these, UC Berkeley worked to fracture the opposition, control the narrative around redevelopment, and produce a hegemonized common sense. At the same time, however, park defenders continued to create a compelling counternarrative. At the subject scale, they decried how students are cultivated as consumers rather than political actors; at the city scale, they aligned with neighborhood groups delaying redevelopment through lawsuits; and at the state scale (and beyond), they promoted the site’s historical and symbolic significance.

Ongoing, highly contentious cases such as People’s Park can thus be seen to spiral outward and upward, connecting multiple scales and processes over time, where broad historical and structuring forces can be implicated in the outcomes of seemingly local disputes. We believe this complex, messy articulation of horizontal forces (cultural, economic, political, and social) across vertical scales (subject, city, and state) requires a spatialized conjunctural analysis. The method of conjunctural mapping relies on a conceptualization of hegemony as a dominant social formation and way of thinking that is constituted and challenged at different scales. It is important to consider beyond the case study presented here as it has the capacity to shed light on the many sites of hegemonic production and disjuncture that make up the “variegated economies” (Peck Citation2023) currently being created and contested worldwide.

In addition to practicing this method in other settings, future work on conjunctural mapping must investigate the relationship between temporalities and spatialities as well as the complexities of interscalar connections. When charting horizontal forces coming together across vertical scales, scholars ought to consider the longer histories of these forces in a particular place. Moreover, they cannot neglect the relations between scales as well as territories, places, and networks. These are critical considerations for conjunctures, not only as phenomenon and form of analysis but also as political project, more fully revealing contemporary struggles over what constitutes reasonable economies, equitable and just development projects, and common sense both locally and globally.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gregory Woolston

GREGORY WOOLSTON is a PhD Student in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064. E-mail: [email protected]. His research considers contested practices of architectural design and regional planning in the United States through the fields of cultural studies and critical race and ethnic studies.

Katharyne Mitchell

KATHARYNE MITCHELL is a Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Dean of the Division of Social Sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064. E-mail: [email protected]. Her current research focuses on migration, urban development, squatting, and the politics of refusal. She is the recent recipient of a Max Planck Institute fellowship in Göttingen, Germany, and an Alexander von Humboldt research award.

References

- Allen, P. 2011. The end of modernism? People’s Park, urban renewal, and community design. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 70 (3):354–74. doi: 10.1525/jsah.2011.70.3.354.

- Arreguín, J. (@JesseArreguin). 2021. “We need …” Twitter, March 18, 4:16 p.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/JesseArreguin/status/1372688434150612993.

- Barton, S. E. 2012. The city’s wealth and the city’s limits: Progressive housing policy in Berkeley, California, 1976–2011. Journal of Planning History 11 (2):160–78. doi: 10.1177/1538513211429932.

- Berkeley Faculty Association. 2022. People’s Park and the future of the public university. Verso Blog, August 22. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/5406-people-s-park-and-the-future-of-the-public-university.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice, trans. R. Nice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1988. Homo ACADEMICUS, trans. P. Collier. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Brentano, C. 1995. The two Berkeleys: City and university through 125 years. Minerva 33 (4):361–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01096518.

- Burawoy, M. 1979. Manufacturing consent: Changes in the labour process under monopoly capitalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Camp, J. T. 2016. Incarcerating the crisis: Freedom struggles and the rise of the neoliberal state. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Carley, R. F. 2021. Cultural studies methodology and political strategy: Metaconjuncture. London: Macmillan.

- Cash, J. D. 2010. People’s Park: Birth and survival. California History 88 (1):8–55. doi: 10.2307/25763082.

- Chapple, K. 2017. Income inequality and urban displacement: The new gentrification. New Labor Forum 26 (1):84–93. doi: 10.1177/1095796016682018.

- City of Berkeley and UC Berkeley. 2021. City council approves historic agreement with University of California, Berkeley. Press release, July 14. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-0714-UC-Agreement.pdf.

- Clarke, J. 2010. Of crises and conjunctures: The problem of the present. Journal of Communication Inquiry 34 (4):337–54. doi: 10.1177/0196859910382451.

- Clarke, J. 2014. Conjunctures, crises, and cultures: Valuing Stuart Hall. Focaal 70:113–22.

- Clarke, J. 2018. Finding place in the conjuncture: A dialogue with Doreen. In Doreen Massey: Critical dialogues, ed. M. Werner, J. Peck, R. Lave, and B. Christophers, 201–13. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Agenda.

- Compost, T. 2009. People’s Park, still blooming: 1969–2009 and on. Berkeley, CA: Slingshot Collective.

- Dalzell, T. 2019. The battle for People’s Park, Berkeley 1969. Berkeley, CA: Heyday.

- Defund SFPD Now (@DefundSFPDnow). 2022. “Last night …” Twitter, August 10, 2:49 p.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/DefundSFPDnow/status/1557484398592765952.

- Dinkelspiel, F. 2019. City sues UC Berkeley for not studying impacts of 30% student enrollment hike. Berkeleyside, June 17. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2019/06/17/city-sues-uc-berkeley-for-not-studying-impacts-of-34-student-enrollment-increase.

- Dinkelspiel, F. 2021a. Labor, community groups file lawsuits to stop Cal “Gobbling up Berkeley.” Berkeleyside, August 23. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2021/08/23/afscme-uc-berkeley-growth-lawsuits-make-uc-a-good-neighbor-the-peoples-park-historic-district-advocacy-group.

- Dinkelspiel, F. 2021b. UC Berkeley is getting a big gift: A $300M, 772-bed student dorm. Berkeleyside, July 7. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2021/07/07/berkeley-new-dorm-helen-diller-safier-donation.

- Dinkelspiel, F. 2021c. UC Berkeley will more than double what it pays the city under new settlement agreement. Berkeleyside, July 14. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2021/07/14/uc-berkeley-payment-settlement-agreement.

- Dinkelspiel, F. 2022a. People’s Park is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Berkeleyside, May 31. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2022/05/31/peoples-park-listed-on-national-register-of-historic-places.

- Dinkelspiel, F. 2022b. UC Berkeley must cut new enrollment by 3K students after high court ruling. Berkeleyside, March 3. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2022/03/03/uc-berkeley-enrollment-cap-ca-supreme-court.

- Disorientation Crew. 2021. Disorientation guide 2021. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://vxkat.info/pages/disorientation/.

- Eagleton, T. 1991. Ideology: An introduction. New York: Verso.

- Gilbert, J. 2019. This conjuncture: For Stuart Hall. New Formations 96 (96):5–37. doi: 10.3898/NEWF:96/97.EDITORIAL.2019.

- Gilmore, J. 2022. Record number of students apply to UC Berkeley. Berkeley News, February 24. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://news.berkeley.edu/2022/02/24/record-number-of-students-apply-to-uc-berkeley/.

- Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the prison notebooks, trans. Q. Hoare and G. N. Smith. New York: International.

- Grossberg, L. 2015. Learning from Stuart Hall, following the path with heart. Cultural Studies 29 (1):3–11. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2014.917228.

- Grossberg, L. 2017. Wrestling with the angels of cultural studies. In Stuart Hall: Conversations, projects and legacies, ed. D. Morley and J. Henriques, 117–26. London: Goldsmiths University Press.

- Grossberg, L. 2019. Cultural studies in search of a method, or looking for conjunctural analysis. New Formations 96 (96):38–68. doi: 10.3898/NEWF:96/97.02.2019.

- Hale, C. R., K. Mitchell, and B. Maurer. 2021. Racial (in)justice and the UC budget crisis. CalMatters, February 8. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://calmatters.org/commentary/my-turn/2021/02/racial-injustice-and-the-uc-budget-crisis/.

- Hall, S. 1988. The hard road to renewal: Thatcherism and the crisis of the left. New York: Verso.

- Hall, S. 2016. Cultural studies 1983: A theoretical history, ed. J. D. Slack and L. Grossberg. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hall, S., C. Critcher, T. Jefferson, J. Clarke, and B. Roberts. 1978. Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state and law and order. London: Macmillan.

- Hall, S., and D. Massey. 2010. Interpreting the crisis: Doreen Massey and Stuart Hall discuss ways of understanding the current crisis. Soundings 44 (44):57–71. doi: 10.3898/136266210791036791.

- Hart, G. 2020. Why did it take so long? Trump-Bannonism in a global conjunctural frame. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 102 (3):239–66. doi: 10.1080/04353684.2020.1780791.

- Harvey, D. 1989. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 71 (1):3–17. doi: 10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583.

- Herod, A. 1997. Labor’s spatial praxis and the geography of contract bargaining in the US East Coast longshore industry, 1953–1989. Political Geography 16 (2):145–69. doi: 10.1016/S0962-6298(96)00048-0.

- Hood Design Studio. 2020. Architectural Digest, December 8. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/ad100-debut-hooddesignstudio.

- Hutchinson, L. 2023. UC Berkeley dorm price rises outpace tuition increases by more than double. The Daily Californian, April 26. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://dailycal.org/2023/04/26/uc-berkeley-dorm-price-rises-outpace-tuition-increases-by-more-than-double.

- Jessop, B., N. Brenner, and M. Jones. 2008. Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26 (3):389–401. doi: 10.1068/d9107.

- Kane, W. 2018. A first look inside Blackwell Hall, Berkeley’s newest freshman living space. Berkeley News, July 31. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://news.berkeley.edu/2018/07/31/a-first-look-inside-blackwell-hall-berkeleys-newest-freshman-living-space/.

- Kell, G. 2022. Campus, city form model alliances to aid unhoused people in People’s Park. Berkeley News, March 9. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://news.berkeley.edu/2022/03/09/peoples-park-press-conference-coverage/.

- Koivisto, J., and M. Lahtinen. 2012. Conjuncture, politico-historical. Historical Materialism 20 (1):267–77.

- Kwok, I. 2023. People’s Park activists open temporary warming shelter. Berkeleyside, January 12. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2023/01/12/peoples-park-warming-center.

- Left in the Bay. 2022. Who owns the park. Verso Blog, August 11. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/5398-who-owns-the-park.

- Leitner, H., and E. Sheppard. 2020. Towards an epistemology for conjunctural inter-urban comparison. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 13 (3):491–508. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsaa025.

- Leitner, H., E. Sheppard, and K. M. Sziarto. 2008. The spatialities of contentious politics. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33 (2):157–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2008.00293.x.

- McElroy, E., and A. Szeto. 2017. The racial contours of YIMBY/NIMBY Bay Area gentrification. Berkeley Planning Journal 29 (1):7–45.

- McNee, G., and D. Pojani. 2022. NIMBYism as a barrier to housing and social mix in San Francisco. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 37 (1):553–73. doi: 10.1007/s10901-021-09857-6.

- Miller, B. 2000. Geography and social movements. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mitchell, D. 1992. Iconography and locational conflict from the underside: Free speech, People’s Park, and the politics of homelessness in Berkeley, California. Political Geography 11 (2):152–69. doi: 10.1016/0962-6298(92)90046-V.

- Mitchell, D. 1995. The end of public space? People’s Park, definitions of the public, and democracy. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 85 (1):108–33.

- Mitchell, D. 2017. People’s Park again: On the end and ends of public space. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (3):503–18. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15611557.

- Mitchell, K. 2004. Crossing the neoliberal line. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Montigue, J., and Stooge . 2021. People’s Park—Rumors of its demise have been grossly exaggerated. Slingshot, March 17. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://slingshotcollective.org/3-peoples-park-rumors-of-its-demise-have-been-grossly-exaggerated/.

- Morrison, R. (@renepakmorrison). 2021. “A march …” Twitter, April 24, 1:17 p.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/renepakmorrison/status/1386051698334990336.

- Natera, X. 2023. Photos: People’s Park turns 54. Berkeleyside, April 25. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2023/04/25/photos-peoples-park-turns-54.

- Neumann, O. 2022. Opinion: Demand the impossible, defend People’s Park. Berkeleyside, August 12. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2022/08/12/opinion-defend-peoples-park-berkeley.

- Newfield, C. 2020. When are access and inclusion also racist? Remaking the University, June 28. Accessed October 28, 2022. http://utotherescue.blogspot.com/2020/06/when-are-access-and-inclusion-also.html.

- Newfield, C., and C. Lye. 2011. The struggle for public education in California: Introduction. South Atlantic Quarterly 110 (2):529–38. doi: 10.1215/00382876-1162570.

- Nicholls, W. 2009. Places, networks, space: Theorising the geographies of social movements. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34 (1):78–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00331.x.

- Park, B.-G. 2005. Globalization and local political economy: The multi-scalar approach. Global Economic Review 34 (4):397–414. doi: 10.1080/12265080500441453.

- Peck, J. 2017. Transatlantic city, Part 1: Conjunctural urbanism. Urban Studies 54 (1):4–30. doi: 10.1177/0042098016679355.

- Peck, J. 2023. Variegated economies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Peck, J., and R. Phillips. 2020. The platform conjuncture. Sociologica 14 (3):73–99.

- People’s Park Council. 2022. People’s Park. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.peoplespark.org/wp/.

- People’s Park Emergency Bulletin. 1991. To the people of Berkeley from the people of the Lower East Side, NYC. People’s Park Emergency Bulletin, August 9.

- People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group (PPHDAG). 2021. Open letter, April 19. Accessed October 28, 2022. http://www.peoplesparkhxdist.org/.

- People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group (PPHDAG). 2022. Nationally significant People’s Park was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 24, 2022. Press release, May 29. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.peoplespark.org/wp/nationally-significant-peoples-park-was-officially-listed-on-the-national-register-of-historic-places-on-may-24-2022/.

- Pierce, J., D. G. Martin, and J. T. Murphy. 2011. Relational place-making: The networked politics of place. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 (1):54–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00411.x.

- Prado, Y. (@Prado_Reports). 2022. “5:58 a.m. …” Twitter, August 3, 6:08 a.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/Prado_Reports/status/1554816527689388032.

- Public Affairs. 2018. New UC Berkeley plans for People’s Park call for student, homeless housing. Berkeley News, May 3. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://news.berkeley.edu/2018/05/03/new-uc-berkeley-plans-for-peoples-park-call-for-student-homeless-housing/.

- Public Affairs. 2022. UC Berkeley statement on court ruling that leaves student enrollment freeze intact. Berkeley News, March 3. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://news.berkeley.edu/2022/03/03/uc-berkeley-statement-on-court-ruling-that-leaves-student-enrollment-freeze-intact/.

- Robinson, R., L. Droste, and J. Arreguín. 2020. It’s time for a new people’s park. San Francisco Chronicle, February 3. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/openforum/article/It-s-time-for-a-new-People-s-Park-15024231.php.

- Scheer, R. 1969. The dialectics of confrontation. Ramparts 8 (2):41–53.

- Señor Gigio. 2022. Random acts of nonconformity: Save People’s Park. YouTube, July 21. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXrS_qJAKTM.

- Sheppard, E. 2022. Geography and the present conjuncture. Environment and Planning F 1 (1):14–25. doi: 10.1177/26349825221082164.

- Smith, N. [1990] 2008. Uneven development: Nature, capital, and the production of space. 2nd ed. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Smith, N. 1992. Geography, difference, and the politics of scale. In Postmodernism and the social sciences, ed. J. Doherty, E. Graham, and M. Malek, 57–79. London: Macmillan.

- Sparke, M. 2006. In the space of theory: Postfoundational geographies of the nation-state. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Suth, K. (@kellyannesuth). 2021. “A gathering …” Twitter, January 29, 3:03 p.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/kellyannesuth/status/1355290423825027072.

- Taplin, T. (@TaplinTerry). 2022. “How many …” Twitter, February 15, 8:27 a.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/TaplinTerry/status/1493622988750483458.

- UC Berkeley. 2022a. Anchor House. Berkeley Capital Strategies. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://capitalstrategies.berkeley.edu/anchor-house.

- UC Berkeley. 2022b. Discover Berkeley. Berkeley Office of Undergraduate Admissions. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://admissions.berkeley.edu/publications/.

- UC Berkeley. 2022c. Explore housing options. Berkeley Housing. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://housing.berkeley.edu/explore-housing-options/.

- UC Berkeley. 2022d. People’s Park Housing. Berkeley Capital Strategies. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://peoplesparkhousing.berkeley.edu/.

- Van der Ryn, S. H., and M. Silverstein. 1967. Dorms at Berkeley: An environmental analysis. Center for Planning and Development Research, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

- White, D. 2021. Berkeley real estate is in a pandemic rise to the stratosphere. Berkeleyside, April 18. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2021/04/18/berkeley-real-estate-is-in-a-pandemic-rise-to-the-stratosphere.

- Wymer, R. 2022. Art, activism combine at People’s Park over Labor Day weekend. The Daily Californian, September 7. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://dailycal.org/2022/09/07/art-activism-combine-at-peoples-park-over-labor-day-weekend.

- Yelimeli, S. (@SupriyaYelimeli). 2022a. “Berkeley and Cal …” Twitter, March 9, 1:05 p.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/SupriyaYelimeli/status/1501665484751585281.

- Yelimeli, S. 2022b. Court order halts UC Berkeley construction at People’s Park likely until October. Berkeleyside, August 5. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2022/08/05/court-order-halts-uc-berkeley-construction-at-peoples-park-at-least-until-october.

- Yelimeli, S. (@SupriyaYelimeli). 2022c. “Dwight blocked …” Twitter, August 3, 12:21 a.m. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://twitter.com/SupriyaYelimeli/status/1554729068683091970.

- Yelimeli, S. 2023a. Appeals court decision halts People’s Park construction indefinitely. Berkeleyside, February 25. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2023/02/25/appeals-court-decision-halts-peoples-park-construction-indefinitely.

- Yelimeli, S. 2023b. Developer walks away from building supportive housing at People’s Park. Berkeleyside, May 11. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2023/05/11/peoples-park-uc-berkeley-rcd-supportive-housing-project.

- Zinshteyn, M. 2022. Lawmakers pass legislative fix to undo UC Berkeley’s enrollment cap. CalMatters, March 14. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://calmatters.org/education/higher-education/2022/03/uc-enrollment-cap-fix/.