Abstract

RATIONALE: There is a need to characterize the real-world impact of benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha antibody, for add-on maintenance therapy of patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.

OBJECTIVES

The objective of this study was to assess change in patient-reported outcomes following initiation of benralizumab, focusing on asthma control, quality of life (QoL), and work and activity impairment.

METHODS

This is an interim analysis of the prospective, single-arm, multi-center, observational POWER study. Eligible patients were recruited from 20 clinics across Canada from 2019 to 2022, had an Asthma Control Questionnaire, 6 Item (ACQ-6) score ≥1.5 and were benralizumab-naïve.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: A total of 131 patients had baseline assessments at the 24-week interim analysis. Asthma control was assessed with ACQ-6 (minimum clinically important difference: change of 0.5 units), and stratified into well-controlled (<0.75), partial control (0.75–1.5) and poor control (>1.5). Improvements in asthma control were observed as early as one week following benralizumab initiation. At 24 weeks, mean change in ACQ-6 was −1.46 (95% confidence interval: −1.71, −1.21), and 47% achieved well-controlled or partial control. Mean EuroQol 5 Dimension, 5 Level (EQ-5D-5L) utility score increased nearly 10% from baseline (0.09; standard deviation 0.2). Absenteeism and presenteeism decreased from baseline (20% and 39%, respectively) to 24 weeks (2% and 21%, respectively).

CONCLUSION

Patients reported meaningful improvements in asthma control, quality of life (QoL) and work and activity impairment 24 weeks after initiating benralizumab, highlighting its positive impact in patients with severe asthma. One- and two-year follow-up are planned to assess exacerbations, healthcare resource use and sustainability of observed benefits.

RÉSUMÉ

JUSTIFICATION

Il est nécessaire de caractériser l’effet réel du benralizumab, un anticorps pour le récepteur alpha de l’interleukine-5, en tant que traitement d’entretien complémentaire chez les patients souffrant d’asthme éosinophile sévère.

OBJECTIFS: Évaluer l’évolution des résultats rapportés par les patients après l’instauration du benralizumab, en se concentrant sur la maîtrise de l’asthme, la qualité de vie (QoL) et l’incapacité à travailler et à s’adonner à des activités.

MéTHODES

Il s’agit d’une analyse intermédiaire de l’étude prospective, à bras unique, multicentrique et observationnelle POWER. Les patients admissibles ont été recrutés dans 20 cliniques partout au Canada de 2019 à 2022. Ils avaient obtenu un score au Questionnaire de maîtrise de l’asthme à six éléments (ACQ-6) ≥1,5 et n’avaient jamais reçu de benralizumab.

MESURES ET RéSULTATS PRINCIPAUX

131 patients ont fait l’objet d’une évaluation initiale lors de l’analyse intermédiaire à 24 semaines. La maîtrise de l’asthme a été évaluée à l’aide de l’ACQ-6 (différence cliniquement importante minimale: changement de 0,5 unité) et stratifié en maîtrise complète (<0,75), partielle (0,75-1,5) et médiocre (>1,5). Des améliorations en matière de maîtrise de l’asthme ont été observées dès la semaine suivant le début du traitement par benralizumab. Après 24 semaines, la variation moyenne de l’ACQ-6 était de -1,46 (intervalle de confiance à 95 % : -1,71, -1,21), et 47 % des patients ont atteint une maîtrise totale ou partielle de leur asthme. Le score d’utilité de l’EuroQol 5 Dimensions, 5 Niveaux (EQ-5D-5L) moyen a augmenté de près de 10 % par rapport au début de l’étude (0,09; écart-type de 0,2). L’absentéisme et le présentéisme ont diminué entre le début de l’étude (20 % et 39 % respectivement) et la 24ième semaine (2 % et 21 % respectivement).

CONCLUSION

Les patients ont rapporté des améliorations significatives en matière de maîtrise de l’asthme, de qualité de vie et d’incapacité à travailler et à exercer une activité 24 semaines après le début du benralizumab, soulignant son effet positif chez les patients souffrant d’asthme sévère. Un suivi à un et deux ans est prévu pour évaluer les exacerbations, l’utilisation des ressources de santé et la durabilité des bénéfices observés.

Introduction

Globally, asthma affects 315 million individuals, of whom 5-10% live with severe asthma.Citation1,Citation2 An estimated 250,000 Canadians have severe asthma.Citation2 Eosinophilic asthma, one of the severe asthma phenotypes, is characterized by increased levels of eosinophils (EOS), greater risk of exacerbations, poor asthma control and reduced lung function.Citation3,Citation4

Benralizumab (FASENRA®, AstraZeneca) is an interleukin-5 receptor alpha (IL-5Rα) antagonist that depletes EOS via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. The phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled SIROCCO (NCT01928771) and CALIMA (NCT01914757) clinical trials demonstrated that benralizumab treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the annual asthma exacerbation rate and improvements in lung function.Citation5,Citation6 Benralizumab is approved for use in several countries, including the United States and in Canada, as an add-on maintenance therapy for individuals with severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma.

Several other biologics are available for the treatment of severe asthma, including mepolizumab (anti-IL-5; GSK), reslizumab (anti-IL-5, Teva), omalizumab (anti-immunoglobulin E; Genentech/Roche & Novartis), dupilumab (anti-IL-4Ra; Sanofi/Regeneron) and tezepelumab (anti-thymic stromal lymphopoietin; AstraZeneca & Amgen). As these biologics are associated with different mechanisms of action and trial-based efficacy, there is a need to assess their effectiveness in the real world. While various real-world studies evaluate the effect of omalizumabCitation7 and mepolizumab,Citation8–10 there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of benralizumab in a real-world setting. Studies reporting benralizumab utilization and effectiveness have been reported in other countries,Citation11–14 but evidence in Canada is sparse, specifically as it relates to patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

The Respiratory Effectiveness Group highlighted the value of real-world studies as both complementary to the results from randomized clinical trials and sources of additional effectiveness data, which can be used to guide treatment-related decisions.Citation15 This descriptive interim analysis from the Patient Outcomes real-World Effectiveness Research study (POWER; NCT03833141) study sought to evaluate the impact of 24 weeks of benralizumab treatment on patients’ asthma control, quality of life (QoL) and work and activity impairment in a real-world setting.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The POWER study is a 24-month prospective, single-arm, multicenter, observational study in Canada, designed to assess change in patient outcomes following initiation of benralizumab. The POWER study is part of AstraZeneca’s XALOC-2 international effectiveness research program for benralizumab, currently underway across Europe and North America. This interim analysis includes data from patients who completed 24 weeks of follow-up, and is intended to examine early findings while the prospective follow-up of patients was still ongoing.

Ethical oversight was obtained from Advarra (Research Ethics Body [REB] # 00000971), University of Saskatchewan (REB# 538) and other site REBs as required for individual sites.

Patients were recruited from 20 participating community and institutional respiratory treatment centers across Canada from January 2019 to April 2022. Benralizumab-naïve patients were included in the study if they had severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma, were over 18 years of age, were prescribed benralizumab for the indicated asthma dosing regimen by their treating physician and received at least one dose. Disease control was assessed at screening using the Asthma Control Questionnaire − 6 Item (ACQ-6),Citation16 with a mean score of ≥1.5 for inclusion. EOS levels were aligned with the standard regulatory and access label: patients must have an EOS count ≥300 cells/µL and a history of two or more clinically significant exacerbations (ie, receipt of oral corticosteroids, emergency room visit or hospitalization) within the last 12 months, EOS ≥150 cells/µL and chronic treatment with oral corticosteroids, sputum EOS ≥3% or history of treatment with another biologic therapy before which the patient met the aforementioned EOS levels. Patients were excluded if they were participating in another clinical trial, had a history of benralizumab treatment or had documented lung disease other than asthma. Patient eligibility was assessed following the treating physician’s decision to initiate treatment with benralizumab, and eligible and interested patients provided informed consent to participate.

Endpoints

The primary outcome of interest was change from baseline in asthma control, measured by the ACQ-6. Mean ACQ-6 scores of <0.75 indicate well-controlled asthma, ≥0.75 and ≤1.5 indicate partially controlled asthma and >1.5 indicate poorly controlled asthma.Citation17 The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in ACQ-6 is a change of 0.5 units.Citation17,Citation18 Secondary measures of importance included asthma-specific QoL (measured with the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire With Standardized Activities − 12 year and older; AQLQ(S)+12) which has an MCID of 0.5, generic QoL (measured with the EuroQol 5 Dimension, 5 Level; EQ-5D-5L), treatment satisfaction (measured with the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication; TSQM-9) and patient impression of change and severity (measured with the Patient Global Impression of Change and Patient Global Impression of Severity; PGI-C and PGI-S). Workplace presenteeism and absenteeism and activity impairment were assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire. Absenteeism was expressed as the percent of worktime missed and presenteeism as the percent of worktime impacted by asthma. Work impairment was expressed as the combination of absenteeism and presenteeism. Resource utilization and concomitant medications were also collected from patients at each follow-up visit.

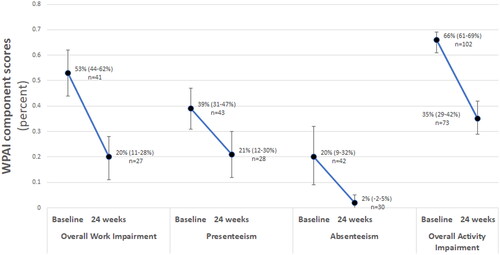

Study assessments were completed at baseline (pre-treatment initiation), in the short term (1, 2, 3 and 8 weeks post-initiation) and long term (24, 56 and 80 weeks post-initiation). Asthma control was assessed at all timepoints and other outcomes (QoL, WPAI, treatment satisfaction, etc.) were measured with lower frequency (see for assessment schedule). All assessments were completed at or before the routine care follow-ups, with some variance in pre-appointment assessment timing permitted depending on the week of follow-up (Online Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1. Study design & patient assessment timing. Abbreviations: ACQ-6, Asthma Control Questionnaire, 6 Item; AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimension, 5-level; HCRU, Healthcare resource utilization; Med, Medication; PGI-C/S: Patients’ Global Impression of Change/Severity; SAE, Serious adverse event; TSQM-9, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication, Version 9.

Initial study assessments were completed using paper copies of the measures in a supervised setting and during routine clinical visits. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many centers reduced or canceled recruitment and research activities, and shortened the length of in-person visits. As a result, clinics were permitted to maintain regular research activity, pause recruitment or suspend research activity entirely. Adaptations for patients included the options to receive at-home administration of benralizumab using a self-administered autoinjector (Fasenra Pen™; AstraZeneca) and completion of study assessments using an electronic data capture system (ClinCapture’s Captivate® platform) prior to their clinic visit. All other study protocol elements were maintained, and digital assessments were emailed to the patients within the defined measurement window.

Statistical analysis

This interim analysis was initiated following close of recruitment when at least 90 patients had completed 24 weeks follow-up. This paper presents baseline patient characteristics of the full cohort, and initial changes in asthma control, QoL, and workplace impact, as well as results from stratified analyses for the subset of patients with data at least 24 weeks post initiation of benralizumab. All analyses were descriptive in nature and were performed in Stata 16 (StataCorp 2016). Categorical data were summarized as count (percent) and continuous data as mean and 95% confidence interval (CI). Mean change from baseline with 95%CIs are reported.

Results

Patient characteristics

One hundred thirty-one patients had completed baseline assessments at the time of analysis. Most patients were of white race, female sex and resided in major urban centers (). Fewer than half of the cohort were employed (n = 58, 45%) at the time of study initiation.

Table 1. Patient demographics in patients with baseline assessments.

Asthma control

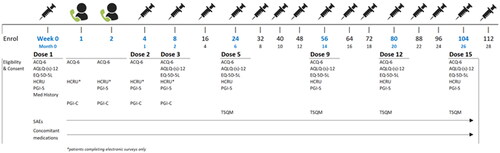

Disease control, as assessed by ACQ-6, was evaluated at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 8 and 24 post initiation of therapy. At baseline, the mean (95%CI) overall ACQ-6 score was 3.27 (3.11, 3.44), corresponding with a cohort of patients with uncontrolled asthma (). At week 24, the mean (95%CI) ACQ-6 score was 1.77 (1.54, 2.01; n = 95). Mean (95%CI) overall change in asthma control at week one was −0.82 (−0.99, −0.65; n = 127). Asthma control continued to improve over the first 24 weeks, with a mean overall change of −1.46 (−1.21, −1.71, n = 95). Overall, 78 patients (82.11%) had met or exceeded the MCID for ACQ-6 at week 24.

Figure 2. Mean asthma control (ACQ-6) score and change in ACQ-6 score from baseline. Abbreviations: ACQ-6, Asthma Control Questionnaire, 6 Item.

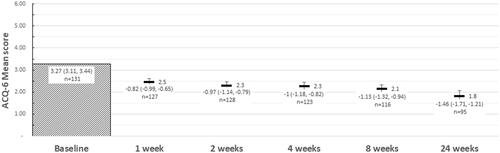

Patients who had completed their 24-week follow-up (n = 95) were stratified by asthma control status at that assessment. Differences between groups in asthma control were noted beginning at week one (). By 24 weeks following therapy initiation, patients with well-controlled (21%) had a mean (95%CI) improvement in their ACQ-6 score of −2.40 (−2.78, −2.02) and those with partial control (24%) improved a mean of −1.99 (−2.47, −1.52). Patients classified as uncontrolled at week 24 (55%) noted a mean change in overall asthma control of −0.65 (−0.90, −0.40) within 1 week of treatment initiation, and the change increased to −0.86 (−1.17, −0.55) by 24 weeks after therapy initiation.

Figure 3. Mean ACQ-6 scores, and change in ACQ-6 scores from baseline at each follow-up, by response at 24 weeks follow-up. Abbreviations: ACQ-6, Asthma Control Questionnaire, 6 Item. At 24 weeks, “Uncontrolled” asthma: ACQ-6 score ≥1.5; “partial control”: ACQ-6 score >0.75 and <1.5; “controlled” asthma: ACQ-6 score ≤0.75.

QoL

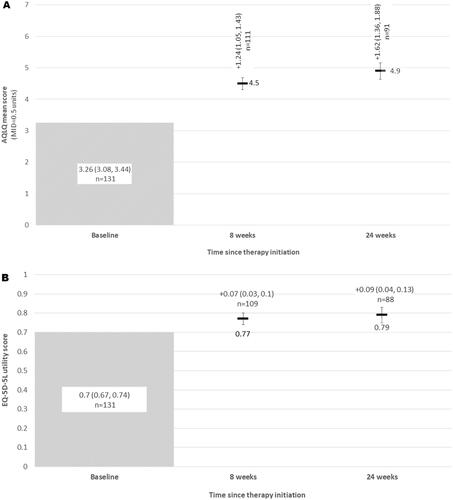

At week eight, the mean (95%CI) change in AQLQ(S)+12 score was 1.24 (1.05, 1.43), with continued improvement (mean change 1.62; 1.36, 1.88) noted at week 24 post treatment initiation (). Of the 91 patients with available AQLQ scores at week 24, 75 (82.4%) met or exceeded the MCID for AQLQ(S)+12 at week 24. Similar improvement was noted in the EQ-5D-5L utility scores for patients. Mean (95%CI) improvement at week eight was 0.07 (0.03, 0.10) and at week 24 was 0.09 (0.04, 0.13) from a baseline mean AQLQ(S)+12 utility score of 0.70 (0.67, 0.74) ().

Figure 4. (A) Mean asthma quality of life (AQLQ) scores, and change in AQLQ scores from baseline at each follow-up; (B) General quality of life (EQ-5D-5L utilities) and change from from baseline at each follow-up. Abbreviations: AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimension, 5-level.

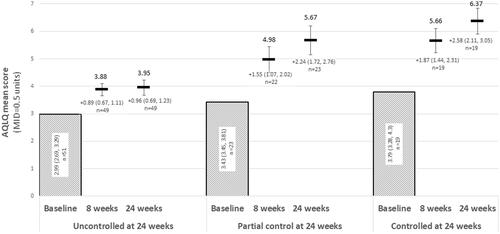

Patients who had completed their 24-week AQLQ follow-up (n = 91) were stratified by asthma control status at week 24. Differences between groups in asthma control were noted beginning at week eight (). Patients regardless of disease control strata exceeded the MCID in AQLQ scores within 8 weeks following initiation of therapy. By 24 weeks after treatment initiation, patients (n = 19) with control (as per the ACQ-6) had a mean improvement of 2.58 (2.11, 3.05) units and those with partial control (n = 23) had a mean improvement of 2.24 (1.72, 2.76) units as measured by the AQLQ. Patients still uncontrolled at week 24 (n = 49) reported a mean change in asthma-specific QoL of 0.96 (0.69, 1.23) after 24 weeks of treatment with benralizumab.

Figure 5. Change from baseline in AQLQ over 24 weeks of treatment, stratified by ACQ-6 responder status at 24 weeks. Abbreviations: ACQ-6, Asthma Control Questionnaire, 6 Item; AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. At 24 weeks, “Uncontrolled” asthma: ACQ-6 ≥ 1.5; “partial control”: ACQ-6 > 0.75 and <1.5; “controlled” asthma: ACQ-6 ≤ 0.75.

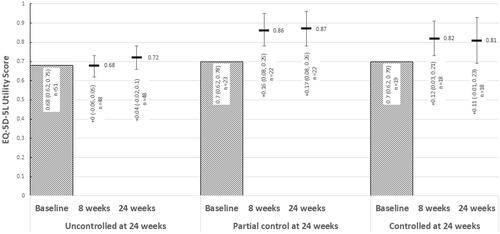

Similarly, improvements in QoL based on the EQ-5D-5L were observed in those who were classified as having partial/complete asthma control based on the ACQ-6, with smaller improvements in patients who continued to have uncontrolled asthma at 24 weeks ().

Figure 6. Change from baseline in EQ-5D-5L utilities over 24 weeks of treatment, stratified by ACQ-6 responder status at 24 weeks. Abbreviations: ACQ-6, Asthma Control Questionnaire, 6 Item; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimension, 5-level. At 24 weeks, “Uncontrolled” asthma: ACQ-6 ≥ 1.5; “partial control”: ACQ-6 > 0.75 and <1.5; “controlled” asthma: ACQ-6 ≤ 0.75.

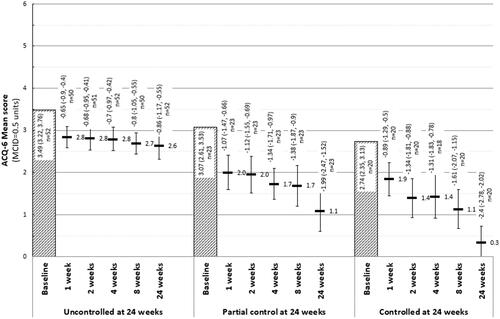

Work productivity and activity impairment

Nearly half of patients (44.6%, n = 58/130 with available data) reported employment at baseline, and approximately 41.1% of patients (n = 30/73 with available data) reported employment at 24 weeks. Results from the WPAI questionnaire at baseline and week 24 are presented in . Absenteeism decreased from a mean (95%CI) baseline of 20% (9%, 32%, n = 42) to 2% (−2%, 5%) at 24 weeks. Presenteeism decreased from 39% (31%, 47%, n = 43) to 21% (12%, 30%, n = 28) at 24 weeks. Work impairment decreased from 53% (44%, 62%, n = 41) at baseline to 20% (11%, 28%, n = 27) by week 24. At baseline both employed and non-employed patients (n = 102) noted asthma-related impairment during 66% (61%, 70%) of hours spent completing activities of daily living. By week 24, activity impairment was reduced to 35% (29%, 42%).

Discussion

The POWER study is an ongoing prospective cohort study focused on the collection of PROs from patients who initiated benralizumab in a real-world clinical setting. The results from this interim analysis highlight the early and sustained impact with 24 weeks of benralizumab treatment on asthma control, confirming its effectiveness in the real-world setting, as well as meaningful impacts from treatment on patients’ quality of life and work and activity impairment.

In this cohort of patients with severe asthma, the mean change from baseline in the ACQ-6 following a single dose of benralizumab (−0.82) indicated an early and meaningful beneficial response to benralizumab. Over 24 weeks, asthma control continued to improve, and approximately 82% of patients met or exceeded the MCID by 24 weeks post benralizumab initiation. The magnitude of this change was amplified in patients who were classified as having gained partial or well-controlled by 24 weeks (based on the ACQ-6 cutoff parameters), when restricted to the cohort with at least 24 weeks of follow-up. However, even patients who failed to gain asthma control (ACQ-6 ≥ 1.5) by 24 weeks of follow-up also reported a clinically meaningful improvement in their asthma control from baseline. Interestingly, patients with higher ACQ-6 scores at baseline had a smaller improvement in asthma control by 24 weeks and those with lower ACQ-6 scores (but still uncontrolled) at baseline had a larger magnitude of change by 24 weeks. Therefore, while ACQ-6 responses varied at 24 weeks, future analyses will aim to examine which factors predict a better response in patients.

As a result, on average, patients with available data at 24 weeks post treatment initiation achieved a clinically important improvement in their disease control over the first 24 weeks of treatment (prior to receiving five doses of benralizumab). It is of relevance that a large portion of this benefit was noted after a single dose (ie, within 28 days of initiation), with clinically important differences noted as early as seven days after the first dose. These findings provide evidence of the early and meaningful benefit with benralizumab, a finding valuable for patients, physicians and payers.

In addition, improvements in asthma-specific and general QoL were observed within the first eight weeks post treatment initiation, and these impacts continued to week 24. In particular, 82.4% met or exceeded the MCID for AQLQ at week 24, highlighting the clinical relevance of these results. While there is no accepted MCID for change in EQ-5D-5L, the utilities measured can be compared with the Canadian value set. In Canada, it has been previously reported that the average adult has a health utility score of 0.86, interpreted as 86% of perfect health.Citation19 At baseline, our cohort reported a mean utility score of 0.70 (0.67, 0.74), or approximately 16% lower health utility compared to the average Canadian. Over the first 24 weeks of treatment, this cohort noted a mean increase in health utility by 9% (4%, 13%), bringing it closer to that of the general Canadian population. When stratified by asthma control at 24 weeks, all patients noted improvements in health utility albeit with magnitude of change associated with asthma control.

The real-world observational CHRONICLE study reported reduced WPAI-identified work and activity impairment in over 1000 severe asthma patients treated with biologics (17%) versus those treated with maintenance systemic corticosteroids (34%) or high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids with additional controllers (27%), although details on the biologics received were not provided.Citation20 Overall impairment in CHRONICLE was lower than the baseline score in POWER (43% vs 53%) Nonetheless, substantive improvements were observed in workplace presenteeism and absenteeism by week 24 in POWER. For patients who were employed, absenteeism due to asthma was reduced by nearly 90%, presenteeism was reduced by 46%, and the overall work impairment due to asthma was reduced by 62%. In addition, limitation during daily activities was halved, with participants reporting a 31% decline in their daily impairment due to asthma. This study is the first to report meaningful reductions on work and activity impairment with benralizumab treatment in Canadian patients in a real-life setting. While a smaller subset of employed patients contributed to this portion of the analysis, these results are encouraging and highlight a patient-relevant endpoint that demonstrates the real-world patient impact of benralizumab on patient’s activities and participation in their daily life.

Overall, the POWER study highlights the benefits of benralizumab in improving asthma control and quality of life, as well as reducing work/activity impairment in patients with severe asthma. Similar findings have been reported from the study in Germany (IMPROVE) contributing to XALOC, highlighting early and sustained improvements in asthma symptoms (measured using a visual analogue scale) in patients over six months post-treatment initiation.Citation21 The IMPROVE study also reported improvements in all domains of the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, which aligns with our QoL findings using the EQ-5D-5L assessment.

A notable strength of the POWER study is the prospective investigation of relevant PROs (ie, ACQ-6 [asthma control], EQ-5D-5L [QoL], WPAI) in a real-world Canadian healthcare setting. To our knowledge, there is no real-world prospective evidence for these outcomes associated with benralizumab treatment in Canadian patients. While this analysis is descriptive and interim, these outcomes will be assessed until 24 months, adding valuable insight into long-term durability of effect and value to patients. Lastly, data from the POWER study is also being integrated into the Global XALOC study program, which will combine findings from multiple replicate studies from a broad and multinational patient population.

Limitations of this study include the descriptive nature of the analyses, as no changes in outcomes were adjusted for baseline demographic or clinical characteristics. POWER is a single-arm real-world observational study and is therefore susceptible to design and selection biases that would ideally be addressed within a randomized and blinded trial. Furthermore, although prior biologic use was included in the questionnaire, numbers were too low to explore in this analysis. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic overlapped a portion of the study period during which standard of care and research activities were impacted differently across the study centers. However, the availability of electronic data collection helped to minimize this potential impact in terms of data collection.

Future planned analyses for the study include assessing if the observed early asthma control is sustained over the 2-year follow-up. It will also be important to assess whether an early response at 24 weeks predicts a sustained response over a longer follow-up and what factors may impact identification of long-term responders to benralizumab treatment, as this may influence treatment decisions and timing of treatment decisions. In addition, the study will continue to evaluate the impact of benralizumab on QoL and work and activity impairment, ensuring that these novel patient- and payer- relevant outcomes are evaluated over a longer follow-up.

Overall, this interim analysis for the POWER study highlights the early and sustained impact of benralizumab treatment on asthma control, and improvement of patient quality of life and work/activity impairments over 24 weeks of follow-up. Importantly, this study provides Canadian-generated real-world evidence on PROs of individuals with severe asthma, complementing phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled trial dataCitation5,Citation6 and provides novel findings on outcomes that have not been previously investigated in a Canadian setting such as workplace productivity. As a result, these findings will help to inform clinical and reimbursement decision making in the Canadian health care setting.

In conclusion, this observational study demonstrates substantial improvements in QoL, asthma control, and work and activity impairments within 24 weeks after initiation of treatment with benralizumab. Further work is planned to assess whether these findings are sustained over a longer follow-up, highlighting continued benefit to patients. Future analyses from the integrated global XALOC study will assess effectiveness and impact on PROs in a larger multinational patient population.

Author contributions

All authors provided their approval of the final version to be published. E. Penz was involved in the design, data acquisition, interpretation and review of the manuscript. S.G. Noorduyn was involved in the design, analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript. B. Lancaster and S. Kayaniyil were involved in the analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript. L. Mbuagbaw was involved in the design and analysis, as well as interpretation and review of the manuscript. D. Dorscheid, O. Tourin, B. Walker, A. Thawer, W. Ramesh, I. Khan, H. Kim and G. Sussman were involved in the acquisition of the data, interpretation and review of the manuscript.

Notation of prior abstract publication/presentation

ERS International Congress 2022 (Barcelona, Spain).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.8 KB)Acknowledgments

Guarantor statement: E. Penz takes responsibility for (and is the guarantor of) the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis

Role of the sponsors: The study sponsor (AstraZeneca) was involved in the study design and preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: The authors would like to acknowledge Alain Gendron for his strong contributions to the initial study design and his expert contributions to the study operationalization, as well as the participating site staff and clinical study coordinators who contributed to and continue to contribute to this study. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge Ozmosis Research Inc. for their support in site management for this study.

Disclosure statement

S.G. Noorduyn was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time of the study conduct. S. Kayaniyil and B. Lancaster are employees of, and own stock in, AstraZeneca. E. Penz is a board member of the Institute for Cancer Research, CIHR. She is medical lead for the Lung Screening Program, Saskatchewan Cancer Agency; she has received non-restricted research grants from CIHR, the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, University of Saskatchewan Respiratory Research Center, Saskatchewan Center for Patient Oriented Research and AstraZeneca; she received advisory board honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim and COVIS Pharma; she received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi-Regeneron. L. Mbuagbaw received fees from AstraZeneca to support the analysis of this work. D. Dorscheid is on faculty at the University of British Columbia and is supported by the following grants: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, British Columbia Lung Association and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. In addition, he has received speaking fees, travel grants, unrestricted project grants, writing fees and is a paid consultant for Pharma including Sanofi Regeneron, Novartis Canada, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and ValeoPharma. He is an active member of the Canadian Thoracic Society, American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society and the Allergen Research Network. B. Walker received advisory board honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim and COVIS Pharma. All other coauthors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Côté A, Godbout K, Boulet L-P. The management of severe asthma in 2020. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;179:114112. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114112.

- To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):204. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-204.

- Aleman F, Lim HF, Nair P. Eosinophilic endotype of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2016;36(3):559−568. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2016.03.006.

- Nelson RK, Bush A, Stokes J, Nair P, Akuthota P. Eosinophilic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):465–473. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.024.

- Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. SIROCCO study investigators. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1.

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2128–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31322-8.

- Lee JK, Amin S, Erdmann M, et al. Real-world observational study on the characteristics and treatment patterns of allergic asthma patients receiving omalizumab in Canada. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:725–735. doi:10.2147/PPA.S248324.

- Lee JK, Gendron A, Knutson M, Sriskandarajah N, Mbuagbaw L, Noorduyn SG. Time on therapy and concomitant medication use of mepolizumab in Canada: a retrospective cohort study. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00778-2020. doi:10.1183/23120541.00778-2020.

- Pilette C, Canonica GW, Chaudhuri R, et al. REALITI-A study: real-world oral corticosteroid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(10):2646–2656. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.05.042.

- Harrison T, Canonica GW, Chupp G, et al. Real-world mepolizumab in the prospective severe asthma REALITI-A study: initial analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(4):2000151. doi:10.1183/13993003.00151-2020.

- Jackson DJ, Burhan H, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Benralizumab effectiveness in severe asthma is independent of previous biologic use. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(6):1534–1544.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.02.014.

- Kavanagh JE, Hearn AP, Dhariwal J, et al. Real-world effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest. 2021;159(2):496–506. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2083.

- Menzella F, Bargagli E, Aliani M, et al. ChAracterization of ItaliaN severe uncontrolled Asthmatic patieNts Key features when receiving Benralizumab in a real-life setting: the observational rEtrospective ANANKE study. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):36. doi:10.1186/s12931-022-01952-8.

- Padilla-Galo A, Levy-Abitbol R, Olveira C, et al. Real-life experience with benralizumab during 6 months. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):184. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-01220-9.

- Roche N, Anzueto A, Bosnic Anticevich S, et al. The importance of real-life research in respiratory medicine: manifesto of the Respiratory Effectiveness Group: Endorsed by the International Primary Care Respiratory Group and the World Allergy Organization. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1901511. doi:10.1183/13993003.01511-2019.

- Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(4):902–907. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x.

- Juniper EF, Bousquet J, Abetz L, Bateman E, GOAL Committee. Identifying ‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the Asthma Control Questionnaire. Respir Med. 2006;100(4):616–621. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.012.

- Juniper EF, Svensson K, Mörk AC, Ståhl E. Measurement properties and interpretation of three shortened version of the asthma control questionnaire. Respir Med. 2005;99(5):553–558. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2004.10.008.

- Guertin JR, Feeny D, Tarride J. Age- and sex-specific Canadian utility norms, based on the 2013-2014 Canadian Community Health Survey. CMAJ. 2018;190(6):E155–E161. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170317.

- Soong W, Chipps BE, O’Quinn S, et al. Health-realted quality of life and productivity among US patients with severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2021;14:713–725. doi:10.2147/JAA.S305513.

- Lommatzsch M, Korn S, Plate T, Grund T, Watz H. Early benefits in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and physical activity (PA) in patients with severe eosinphilic asthma (SEA) treated with benralizumab: interim analysis of the imPROve asthma study. Paper presented at: European Respiratory Society International Congress 2022; September 4–6, 2022. Barcelona, Spain.