ABSTRACT

This article reports the findings of a survey of more than 100 Australian outer regional and remote public library managers. Public libraries in these areas serve more than 2.5 million Australians, representing an important yet under-researched topic. Using an online questionnaire, with a response rate of more than 40%, we asked public library managers in rural Australia about the services provided by both fixed-site and mobile libraries (where applicable), as well as online and other outreach services. Questions also covered the value, issues and challenges of respondents’ library services. Findings suggest that while rural libraries perform some similar functions to their more urban counterparts, and share some challenges, they are especially valued by their communities in the absence of alternative services and social outlets, making the library even more of a key facilitator, potentially, of social inclusion and community interaction. Respondents also noted an increasing demand for IT services and digital literacy support among their users, a need sometimes at odds with the challenge these libraries face maintaining up-to-date technical infrastructure.

Introduction

Whilst the various standards and frameworks pertaining to Australian libraries, such as the current APLA-ALIA Standards and Guidelines for Australian Public Libraries (Australian Public Library Alliance, Citation2021), might aim for a reasonably consistent and equitable level of service for library users across the nation, very little detailed research has been conducted into public library provision in Australia’s more geographically remote areas. These areas may be relatively sparsely populated, but nevertheless represent vast swathes of land, dotted with communities in and around which live significant numbers of people potentially with as much, or more, need for library services as people have in Australia’s cities and regional centres. However, even the standard reports on public library provision across Australia (or Australasia) as a whole (e.g. National and State Libraries Australasia (NSLA)) only occasionally differentiate by remoteness of service, breaking the data down by state, but not drilling down too much further geographically (National and State Libraries Australasia, Citation2023). Aiming to address this gap, we report here the findings from a questionnaire survey conducted with over 100 library service managers from across these more remote regions, presenting a snapshot of library provision in early 2020s rural Australia, and highlighting ways in which this provision might differ from that in more urban parts.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) uses the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) (University of Adelaide & Australian Centre for Housing Research, Citation2023) to measure the remoteness of different geographical areas, which divides degrees of remoteness into five categories: major cities, inner regional, outer regional, remote and very remote. These categories are intended to stand for the levels of accessibility to goods, services and people set out below (according to https://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/about-statistics/statistical-standards-classifications/accessibility–remoteness-index-australia).

Major Cities (ARIA score 0 ≤ 0.20) – relatively unrestricted accessibility to a wide range of goods, services and opportunities for social interaction.

Inner Regional (ARIA score greater than 0.20 to ≤2.40) – some restrictions to accessibility to some goods, services and opportunities for social interaction.

Outer Regional (ARIA score greater than 2.40 to ≤5.92) – significantly restricted accessibility to goods, services and opportunities for social interaction.

Remote (ARIA score greater than 5.92 to ≤10.53) – very restricted accessibility to goods, services and opportunities for social interaction.

Very Remote (ARIA score greater than 10.53 to ≤15) – very little accessibility to goods, services and opportunities for social interaction.

Whilst most of Australia’s land is remote or very remote, as per this index, most of the Australian population resides in the major cities. Nevertheless, according to data from the ABS, in 2021 about half a million people lived in remote or very remote areas, and a further two million people in the outer regions (Data.gov.au, Citation2024). In these areas, people’s access to goods and services is at least ‘significantly’ restricted. This is reflected in some of the other statistics found in the cited dashboard at Data.gov.au (Citation2024). While 66.0% of people in the major cities held a vocational or higher education qualification in 2021, only 52.3% in the outer regions and 36.8% in very remote areas did. Again, in 2021, 78.3% of young people in the major cities were earning or learning, but 71.9% in the outer regions and 47.3% in very remote areas. The level of generalised trust (a measurement of ‘the degree that people in a community feel they can trust one another’ (p. 158)) also graduates downwards according to remoteness: in 2014, it was measured as 55.6% for the major cities and 50.8% for the outer regional and remote areas (Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, Citation2016). It is of course also the case that Indigenous Australians, a group who have suffered systematic disadvantage since the days of the first colonial settlers, are overrepresented in this pattern, disproportionately populating many of the nation’s more remote regions. Whilst things may have improved for remote and outer regional Australia since the dates of these statistics, there is little indication that these patterns have dissolved: from the 2021 census data, the ABS (Citation2021) summarises that, according to socioeconomic indicators, ‘generally, disadvantaged areas tend to be in regional and remote communities, while advantaged areas tend to be in major cities’.

It is these relatively underserviced populations that are the subject of this article, that is, those living in the outer regional, remote, and very remote areas of Australia. We shall sometimes use the term ‘rural’ as a shorthand for these areas. They are differentiated here from the more urban parts of regional Australia, i.e. inner regional areas, which include cities and towns of considerable size, such as Wagga Wagga in New South Wales, in which three of the authors’ university is located. While around 200 km from the nearest capital city, Wagga Wagga, for instance, provides access to most services its residents need for daily living, in contrast to the settlements we focus on in this article, which are considerably more remote, and we hypothesise might rely more heavily on their libraries to fill service gaps and meet other community needs, given their relative isolation. The remoteness classification of all communities across Australia can be found using the Health Workforce Locator (https://www.health.gov.au/resources/apps-and-tools/health-workforce-locator/app).

The survey we report on was conducted with the support of both the Australian Library and Information Association and the Australian Public Library Alliance, and aimed not only to paint a picture of the services and role of public libraries in rural Australia, but also to give a voice to library managers working in these regions, and to highlight the particular challenges they might face, in light of ever tightening budgets, varied levels of infrastructure, and increasingly extreme weather conditions. Two research questions framed our investigation:

What are the public library services currently being offered to communities in rural Australia?

What are the challenges and prospects for public library services in rural Australia?

Literature Review

Studies looking at the issues specifically facing rural Australian libraries have been few and far between, and have tended to be state-based and to cover one particular facet of the public library service. Haines and Calvert (Citation2009) focused on the staffing of libraries in rural South Australia, concluding that many of the staff were very motivated due to their deep personal involvement with their users and communities, but that their geographic isolation could be a major challenge, especially in the way it limited opportunities for training and development. (One might speculate that since the time of this study, these opportunities are likely to have increased due to advent of Zoom and its ilk). A little later, Abu et al. (Citation2011) compared the ways in which public libraries contributed to rural development in Malaysia and Australia, through three case studies based in each country. They found that the libraries were having a major impact on the social and economic development of their communities, particularly in rural Malaysia. They also noted, however, that the Malaysian libraries could make an even greater impact with more current and appropriate resources, and would benefit from more support from their state library.

Earlier, Monley (Citation2006) examined three particular models of library co-location in rural Queensland, that is, libraries sharing spaces with (a) government service delivery, (b) tourist facilities, and (c) IT/training/business support services. He noted that co-location may well become an increasingly favoured option for public library provision in rural areas, given declining populations and the increasing viability issues surrounding physical service points. Meanwhile, Nakata et al. (Citation2007) reported on the implementation of a ‘Libraries and Knowledge Centre’ (LKC) model of service to support three remote Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory. They highlight the benefits of a service that incorporates both Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge systems, as well some of the issues that have to be faced, such as those relating to intellectual property. The LKCs might be considered similar in function to the Indigenous Knowledge Centres that have been developed by twelve Indigenous Shire Councils in Queensland (https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/about/partnerships-and-collaborations/local-government-and-public-libraries/indigenous-knowledge).

Earlier still, the last nationwide survey of mobile library services was published by Kenneally and Payne (Citation2000). The authors estimated that there was a total of about 81 mobile libraries at that point in time, and argued that they

play a vital role in communities throughout Australia. This is particularly so in rural and remote communities of low population density, where they also fulfil a social need as a meeting place, and function as distribution points for a myriad of specific local community information. (Kenneally & Payne, Citation2000, p. 63)

Knight and Makin (Citation2006) elaborate on the value of the modern mobile library, detailing its evolution from the more basic vehicles of the previous century to ‘a full branch on wheels’. They note that ‘they exist in both urban and rural areas, but [that] it is in rural and remote communities where mobiles make the most difference in terms of addressing access and equity of service issues’ (Knight & Makin, Citation2006, p. 95).

Other papers discussing developments and issues pertaining to Australian rural libraries, or at least some of them, can be found principally in issues of Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services from the 1980s and 90s (e.g. Edwards, Citation1988; Latrobe Valley Regional Library Service, Citation1992; Leary, Citation1991). A conference focused on Australian rural libraries was held in Wagga Wagga, in 1987 (Henri & Sanders, Citation1987).

Other, more recent research of broader scope has sometimes reported findings from case studies of, or survey respondents in, libraries located in rural and remote Australia, but which have seldom been given very great prominence. From their survey of Australian public library responses to the COVID-19 crisis, Garner et al. (Citation2021) noted that remote and regional libraries had been less well positioned to work around the forced site closures by moving services online than their metropolitan counterparts had been. Wakeling et al. (Citation2023) have likewise noted how their more remote case study of public library users’ needs in a COVID-changed world illustrated how rural Australia appears to be at particular risk of failing its library users, due in large measure to a lack of resourcing. Meanwhile, Osman et al. (Citation2023) worked with the State Library of Queensland to evaluate the impact of its digital inclusion programs across the whole of the state, including in its rural and remote communities.

Our paper aims to build on this relatively small body of work to shed new light on the present and future roles libraries play in rural Australian communities. We now outline our survey methodology before presenting the results in two parts in broad alignment with our two research questions. In Part A of the results, we give a descriptive account of public libraries and the services currently being offered to communities in rural Australia. In Part B of the results, we delve deeper into the value, challenges and prospects for public library services in rural Australia.

Method

The questionnaire survey targeted those responsible for Australia’s public library services, i.e. their managers, across outer regional, remote and very remote Australia. Modelling it on a survey conducted three years ago to investigate public library responses to the COVID-19 pandemic across the whole country (Garner et al., Citation2021), we asked the state and territory representatives of the Australian Public Library Alliance (APLA) to update the contacts lists they provided previously, with the aim of using these to invite the overall manager of each service to complete the survey, but in this case filtering out those services that did not cover any outer regional, remote or very remote areas, according to the Health Workforce Locator (https://www.health.gov.au/resources/apps-and-tools/health-workforce-locator/app), applying the 2016 ABS index.

We note that the lists we used were not altogether complete, as not all services, and not all services in outer regional and remote Australia in particular, are covered by APLA (most notably not in Queensland), and in a few cases the lists might also not have kept up with changes that occur from time to time to local government configurations and to arrangements specifically for public library provision. Nevertheless, ending up with contacts for a total of 250 different library services covering outer regional, remote and/or very remote areas, we are confident that we distributed the survey to representatives of most remote and outer regional library services in Australia. Those contacts who responded managed about two branch libraries on average, so extrapolating, the 250 contacts represented approximately 500 branches, whilst in the latest NSLA public library statistics, there are 1405 branch libraries across the whole of Australia, including the metropolitan and inner regional areas (National and State Libraries Australasia, Citation2023). We should also note, however, that our list did not cover most of the Indigenous Knowledge Centres that provide specialist services to Indigenous communities in some of the more remote areas of Queensland; while these centres do act as community libraries in some ways, they also serve additional functions, beyond the scope of the standard public library, which was the focus of this survey.

For efficiency and convenience, we asked library managers to complete the survey online rather than on paper, and thus created the questionnaire on the Survey Monkey platform. Emails inviting the 250 contacts to complete the survey were sent out in November 2023. The survey consisted of 30 questions, covering a wide range of aspects of the respondents’ library services, including those of both fixed-site libraries and mobile libraries (where applicable), as well as online and other outreach services. The last six questions in particular covered the value, issues and challenges of respondents’ library services, and invited open-ended responses; most of the earlier questions were closed. The survey was anonymous, and the contacts were given two weeks to submit their responses. One or two of the emails bounced, in which case a generic email address for the library service was identified and used instead; out-of-office emails were followed up by re-sending the invitation to the alternative contact provided, where applicable.

The quantitative survey data was statistically analysed using the Survey Monkey built-in analysis and Excel; the free-text answers were thematically coded and analysed as qualitative data, in line with Braun and Clarke (Citation2006).

Results: Part A – Description of Rural Libraries and the Services They Provide

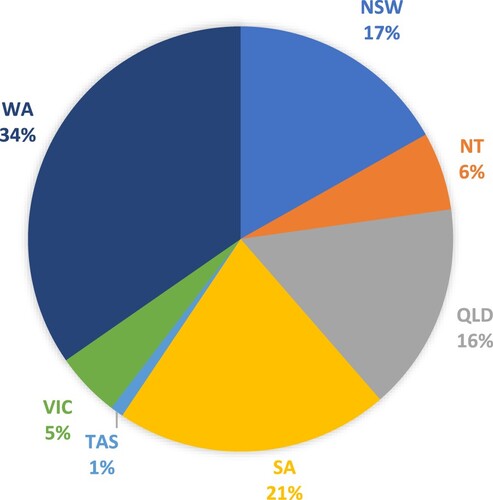

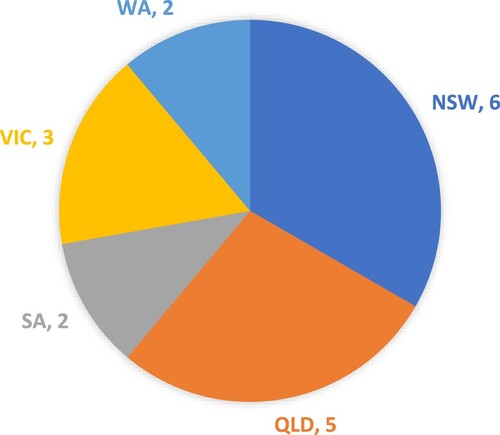

The survey garnered a total of 102 responses, with respondents hailing from all Australian states and territories except for the Australian Capital Territory, which does not cover any outer regional or remote areas. As shows, the state most represented in the survey responses is Western Australia, with about a third of the respondents, corresponding to the state with the largest number of contacts to which we emailed invitations. While the representation across the states is broadly in line with their representation on our contact lists, it should be borne in mind, as we relate the survey’s findings, that this representation may not be completely in line with the number of individual libraries, or even library services in an organisational sense, located in the remote and outer regional areas of each state and territory, as noted in the previous section. Nevertheless, the overall number of respondents constitutes over 40% of the total number of invitees, and thus a large sample of library service managers working in rural Australia, albeit one that might be biased towards those of Western and South Australia.

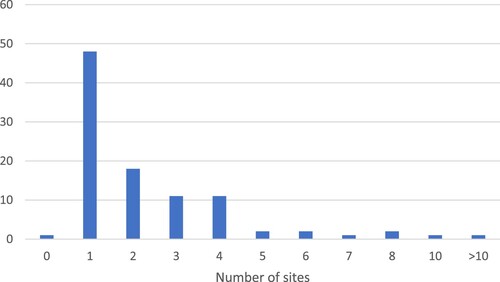

Ninety-eight of the respondents indicated how many fixed library sites they were responsible for. As shows, about half were responsible for just the one library site, but others were responsible for two or more, with a few responsible for five or more. The total number of fixed sites that respondents indicated they were responsible for was 216, though this would include some libraries in areas not classified as outer regional or remote, as some library services cover very large catchments. However, it would be safe to assume that about 200 libraries located in remote and inner regional Australia were represented by the survey’s responses, so that respondents were answering for about two fixed-site libraries in these areas on average.

Size of Communities Served

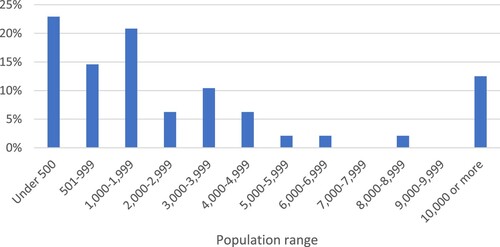

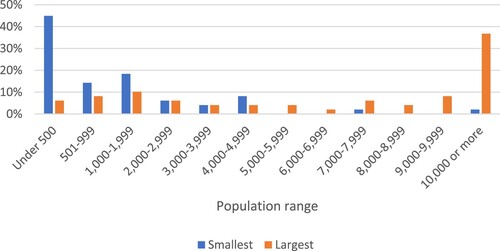

The next questions asked about the largest and smallest communities in which the respondent’s library service operated a fixed-site library. The estimated population size of the community served in the case of library services with one fixed site (n = 48) is summarised in . Over half the settlements in which the site is located have estimated populations of fewer than 2000 residents, and over 20% of them have fewer than 500 people. Over 10%, on the other hand, have over 10,000 residents. shows the percentage distributions of largest and smallest communities by estimated population size in the case of library services with multiple sites (n = 49). Like many of the single-site library services, many of these library services also operate libraries in quite small population centres, with their most remote library being located in settlements of fewer than 2000 people in about 75% of cases. On the other hand, over 35% of the multi-site services’ least remote library is located in a settlement with a population of over 10,000.

Staffing

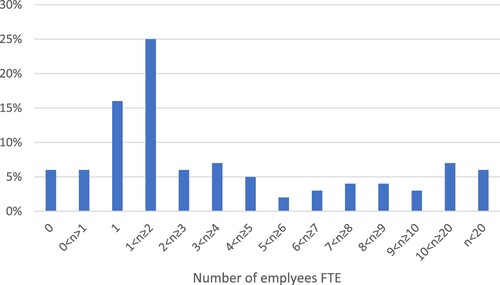

The respondents’ library services tended to be run by a small number of paid staff. About half employed two or fewer FTE staff, although some employed much larger numbers, as indicates. It is noteworthy that 5% did not employ any staff to run their service (one might assume that in these cases the respondent was employed at a higher level in the local government organisation). A further 5% employed only a part-time staff member, and another 15% exactly one FTE. Ninety-seven respondents provided figures for both their number of fixed-site libraries and the number of FTE staff. From these responses, the total number of FTE staff is 694.3, and the total number of fixed sites 261. Thus, the average from the responses is 2.66 FTE staff per library site, bearing in mind that some library services also operated mobile libraries, online libraries, and other outreach services, and that a few of the library sites would have served communities in inner regional areas.

About half the library services (51 out of 98 responses) reported engaging volunteers. The amount of volunteer work harnessed varied widely, however, from less than an hour a week, to scores of hours per week. The average amount of volunteer time spent per library site, including those sites that did not engage volunteers, worked out to be 1.1 h a week.

Sites

The library services housed their libraries in a range of building types. About a third housed them in dedicated, stand-alone buildings, about a quarter in a building that was shared with other local council services, and a few in a non-council building. However, another third of the library services housed their libraries in varying building types, of which the most common were dedicated and council buildings, but almost as common were spaces shared with schools, retail outlets, health services, and so on.

Library Resources Offered

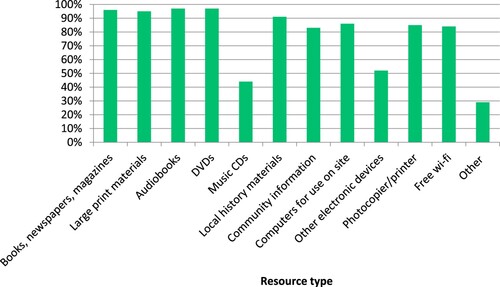

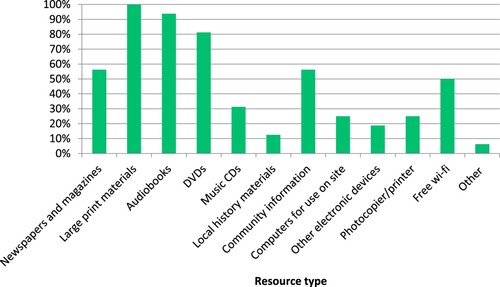

Most respondents reported that their libraries offered most of the expected kinds of resources. As per , over 80% reported that they provided the categories listed in the relevant question, except for music CDs (about 40%) and electronic devices apart from computers (about 50%). Over a quarter of the respondents also noted a range of other materials on offer (if not always for loan), including games, jigsaws, etc. (10), toys (4), kits for craftwork, etc. (3), makerspaces and STEAM equipment (e.g. robotics) (4), play stations, x-boxes, etc. (2), musical instruments (2), seeds (2), and various other items that were sometimes components of a ‘library of things’ (e.g. sewing machines).

Library Services Offered

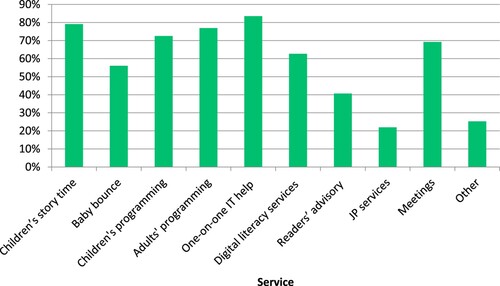

Most respondents noted an array of services that their libraries provided, although no category of service set out in the questionnaire was offered by 90% or more (see ). Notably, the most commonly offered was one-on-one IT help (84%), followed by children’s story time (79%). Most library services offered other kinds of children’s programming, as well as programming for adults, digital literacy services and meeting rooms. Readers’ advisory services were offered by 41% of libraries. Under ‘other’, respondents also noted support for local and family history research, more specific forms of programming (e.g. author events, book clubs, conversation classes for migrants, and so on), book sales, and various community services provided by external agencies, such as ‘tax help’, NDIS visits, parental training, etc.

Opening Hours

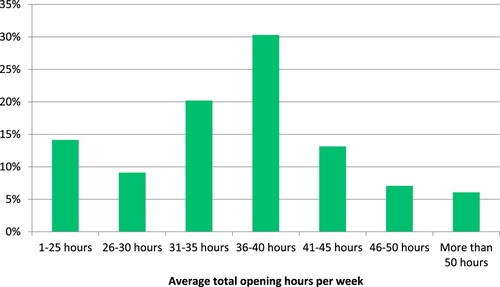

The average opening hours for sites in each of the respondents’ library service varied quite considerably, as shown in . For almost 15% of services, it was 25 h or fewer, whereas for about another 15% it was 46 or more hours. The median, and also the mode, was in the range of 36–40 h.

Future of Sites

Respondents were asked about the future of their library sites. Ten per cent thought it more likely that a new site would open than an existing site close, whereas 17% thought the opposite; the remainder were uncertain or considered the two scenarios to be similar in likelihood.

Mobile Libraries

Eighteen respondents indicated that their library service included a mobile library; two of these respondents indicated that they operated two vans. The respondents’ states are shown in , in line with other reports of mobiles being more of a feature in eastern than western Australia (especially given this survey’s possible respondent bias towards Western and South Australia), noting that this sample does not cover those mobile libraries serving metropolitan and inner regional areas. It is worth noting, however, that all of the largest states are represented, although not the Northern Territory.

The 18 respondents were asked how many staff were sometimes rostered to operate their mobile libraries. The 17 numerical responses ranged from zero (perhaps the van is operated by volunteers or is self-driving!) to five. The two respondents with two vans both had two staff covering their mobile service. The mean number of staff covering the mobile library services was 1.5.

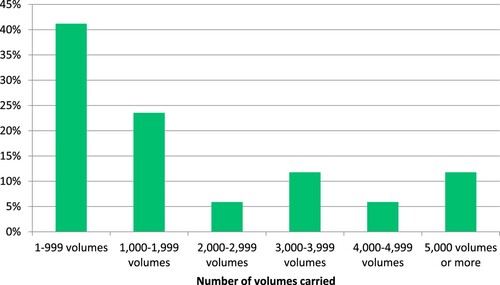

The respondents’ mobile libraries generally did not carry very large quantities of book stock. About 40% typically carried fewer than 1000 volumes, and about 70% fewer than 2000. However, some carried considerably more than this, with a few of the vans loaded up with 5000-plus volumes. gives the breakdown.

As shows, the mobile libraries offered other resources apart from standard book stock, although some carried a much greater range of materials than others. All carried large print materials, and almost all audiobooks. About 80% carried DVDs, and about half offered newspapers and/or magazines, community information, and free wi-fi. Some of the vans carried other materials, including local history materials in two cases, while four provided computers for patrons’ use, and four reprographic services. One mobile library even offered outdoor games equipment.

Six of sixteen respondents indicated that patrons are involved in other activities, apart from selecting and borrowing items, in the mobile library. In three cases, children’s activities, including story time, are hosted; other activities included seeking assistance with online resources, and with local history and genealogy enquiries, and engaging with other council services.

All but one of the 16 respondents indicated that the mobile library visited specific institutions. Most vans visited various schools and/or pre-school centres (13), with several also visiting aged-care facilities (5) and hospitals (3). Two visited community centres, one a retirement village, and one also stopped off at pubs (for the patrons, no doubt).

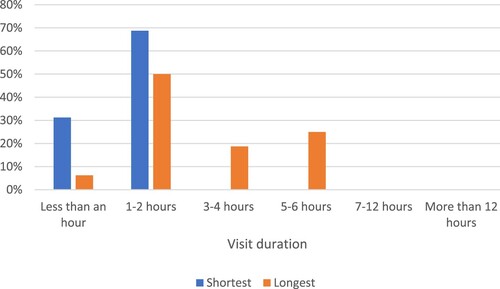

We can see from that the respondents’ mobile libraries did not visit places for extended periods of time, with no vans spending a whole day with any one community. Around a third of mobile libraries’ shortest visit to a community was for less than an hour, while only a quarter of the vans’ longest visit to any community was for 5–6 h. In 56% of cases, the longest visit was for no more than two hours.

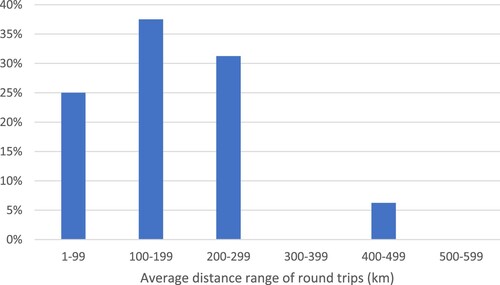

Most mobile libraries visited their communities either fortnightly (63%) or monthly (31%), on average, with only one mobile service visiting more frequently. shows the distance of the average round trip made by the 16 respondents’ mobile libraries. In most cases, it is over 100 km, and only in one case is it over 300 km (it being over 400 km in that case).

Mobile Library Services are Likely to Continue

Respondents were generally optimistic about the likelihood of their mobile library service still operating three years from now. Of the 16 respondents to this question, three quarters answered that it was ‘likely’ (3) or very likely (9). Three respondents said it was ‘50:50’, while only one suggested it was ‘unlikely’. This last response may have been in error, as the associated free-text response only stated that the service was ‘still in high demand’. Expanding on their answers, the respondents who answered ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ pointed either to recent investments in new mobile library vehicles (‘Mobile Libraries are a big investment and so our vehicle is new so will likely stay in the next 3 years’) or their value in serving remote communities (‘Our mobile library is valued by our remote communities. It is more likely that we will expand’). One respondent who was 50:50 about the mobile library existing in three years gave three reasons for their answer: an ageing fleet, low return on investment, and the timing of visits not meeting the needs of the community (‘We go during the week when much of the community isn't at home’).

Online Services

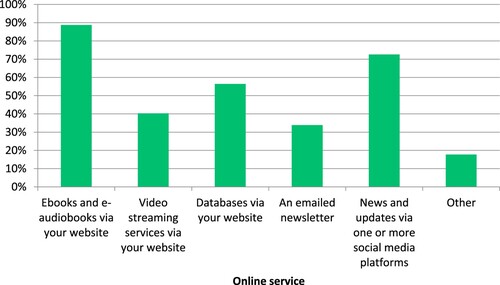

Almost 90% of library services offered ebooks and e-audiobooks via their website; a few respondents noted that their library service did not have its own website, though two mentioned that their patrons could instead access online resources via a consortium. The services’ own online offerings were otherwise somewhat limited, with less than 60% providing databases, and only 40% video streaming. About 70% of library services used one or more social media platforms. shows the breakdown of responses.

Other Outreach Services

Apart from online and mobile library services, about 60% of respondents noted other forms of outreach that their libraries engaged in. The most common form, listed by over 80% of these respondents, was a home delivery service, catering for the more remote communities and/or for the homebound. Some library services undertook visits to schools and/or pre-school centres, providing story time and other sessions. A few visited hospitals and health centres. Efforts were also made by some to participate in community events, and a few organised their own programming at community centres, parks, and/or for community groups, such as men’s sheds. Only two respondents listed kiosks, one ‘street libraries’, and another a mailing service.

Results: Part B – Value, Challenges and Prospects for Rural Public Libraries

The Value of Rural Libraries

Rural Libraries Serve Their Communities in Many Important Ways

In total, 89 respondents provided a written answer to the question about the most important ways in which their library service serves its communities. Many respondents highlighted the importance of the library space as a ‘community hub’. Some noted that it was the only public space available to the community, and many highlighted how it offered visitors an opportunity for connection with others in the community; as one put it, ‘somewhere that people can go and be able to connect with others’. The provision of meeting spaces for local community groups was often mentioned, and a number of respondents also highlighted the value of the library as a comfortable physical environment, often referencing the provision of air conditioning and comfortable furniture (‘Our library service provides a cool, safe place from the often harsh temperatures’). It was notable that three words were repeatedly used to describe the library space: ‘welcoming’, ‘safe’ and ‘inclusive’. Respondents often highlighted how important these qualities were to community members, and how, sometimes, the library was the only public space with the qualities available.

Respondents also highlighted the value of their collections to their users, particularly the physical resources. Book borrowing was unsurprisingly recognised as a key need for users, but DVDs were also frequently mentioned, because, as one respondent explained, ‘Many cannot use digital services due to connectivity or financial constraints.’ While electronic resources were mentioned less frequently, some respondents did suggest the value of ebooks and other digital material to users, and particularly the fact that users could access these outside library opening hours.

A significant number of respondents identified the provision of computers, free wi-fi, and printing services as being hugely valuable to their communities. Some respondents emphasised that users often did not have access to these services anywhere else: ‘It may be because of the remoteness and lack of alternatives nearby … computers and printers are the most demanded services in our library.’ Several responses also suggested that the provision of local community information (encompassing events and news, as well as local history) was highly valued.

Programs and events offered by libraries were another major theme of responses. Programs such as story time, holiday activities, book clubs and author talks were all cited as being valued by users. A large number of respondents also highlighted work done by their libraries to support digital literacy. In some cases, this was in the form of specific events or a training course (‘We offer technology training programs to help residents develop digital literacy skills’). More often, however, respondents referred to ad hoc support that librarians offer users for a multitude of technology-related needs, for example connecting to and using social media, setting up new devices, using mobile banking, or accessing online resources.

It was interesting to note that for many respondents the value of the library was perceived as being not just about what it does, but also who specifically it serves. While, as noted, many respondents emphasised inclusivity as a key quality of the library, several distinct user groups were commonly highlighted. Elderly users were mentioned by a large number of respondents as particularly valuing the services the library offers, and of often being most in need of the social connection afforded by the public library space, and of the digital literacy support provided by librarians. Children and young adults were also commonly referenced, sometimes in the context of after school or holiday activities, but also more generally as members of the community for whom there are often few other services. The life-long value of literacy programs for younger children was described by some respondents, as well as the value for mothers of the library as a place they could bring their children. Finally, some respondents did not name particular demographic user groups, but instead referred more broadly to ‘socially disadvantaged’ or ‘socially marginalised’ members of the community. Again, the library was seen as a vital service for such users who were perceived to value the social connection of the library space, the inclusivity of library services and programs, and the free access to resources.

How the Services Could be Improved

Bigger and Better Libraries Needed

The respondents were then asked about what they think would most improve their library service. The most commonly occurring theme to emerge from their answers related to their libraries’ sites. About a third of respondents (who answered this question) mentioned how they would like a new and bigger library building, or at least the refurbishment of an existing one. More space was desirable for a range of reasons, such as to accommodate new programming, meetings, study, displays, and so on, or to free up room currently taken up by other council services. Some of the respondents’ ideas for new or redesigned libraries included more innovative features, such as a café, and others more basic ones (e.g. ‘a toilet so people can stay in our library longer’). Two respondents wanted to relocate their library to the centre of town (‘so people would walk in unplanned, rather than having to make a special trip’).

More Staff, Resources and Outreach Also Needed

Another theme that arose quite often was that of staffing. About 20% of respondents highlighted the need for more staff, including more professionally trained (and paid) staff, and more specialist staff, such as those with more advanced IT skills; one respondent specifically asked for a social worker; another, for a dedicated reference librarian. Respondents also wanted to see more consistent staffing across their libraries, while several advocated for longer opening hours, particularly in the case of their smaller libraries, with corresponding staffing implications. More staffing would enable libraries to expand their services a variety of ways.

Over 10% of respondents wanted to improve their library collections, in some cases their service’s online resources, in others its physical offerings. Several mentioned the need for an improved supply of hard copy materials, to better meet the reading interests and demand of their patrons. One respondent noted the need for more resources in Indigenous languages. Other kinds of physical resources, particularly IT-related ones (PCs, wi-fi, etc.), were also mentioned by a few respondents. Meanwhile, about 10% of respondents highlighted the value of more programming, for adults and/or children, such as IT-related classes and ‘special events’. Some respondents also advocated for a higher level of service provision to support digital literacy.

Again, around 10% of respondents talked about outreach, especially to those ‘less connected’ communities not served with their own library. Some advocated for more fixed sites, some a mobile library service, and others alternative forms of outreach, such as smart lockers. Related to outreach, several respondents thought that there could be more effective ways of promoting their library service, including the targeting of more vulnerable, disadvantaged groups. Finally, one respondent simply wanted to see more users, to enhance the library’s role as a community builder: ‘I know that [our current users] like the social aspects of activities in the library’.

Impact of COVID Pandemic

Around a third of respondents indicated that the COVID pandemic had changed things ‘in some ways’ for the library service, and about 10% that it had changed things ‘a lot’. The remainder thought that they were now mostly back to how things were before. The respondents’ commentary on their assessments is summarised below.

Digital Library Services Have Been Normalised

The pandemic initiated and/or accelerated the uptake of digital services by library patrons. Respondents reported that patrons are accessing online audio, e-books, and other e-resources more frequently than before and, accordingly, that loans of physical resources have declined. Not only is there higher demand for online resources by patrons, but libraries are also using more digital technologies, including collaborating online with colleagues (such as on MS Teams) and delivering services online (e.g. online workshops). As one respondent said, ‘We learnt to deliver many sessions, such as story time, via the internet.’ A challenge for libraries going digital post COVID is that, even though they are now expected to be operating ‘as usual’ in terms of in-library services, they are also needing to perform online and outreach activities, but without additional resourcing. As one respondent noted,

Staff and some areas of the budgets were reduced during the COVID pandemic and have not been reinstated or increased afterwards. Services offered are back to normal with reliance on volunteers to assist staff workloads.

Libraries Now Provide More Flexible and Inclusive Services

Some respondents said that, because they had not been required to lockdown for more than a few weeks, the pandemic had little impact on library patronage and services. These reports were outweighed, however, by respondents who recounted several ways that their library had made changes to meet customers’ needs during the pandemic. As one respondent said,

During Covid 19 we didn't let our patrons go without. We partnered with the local medical centre who provided a free pickup and delivery weekly to patrons.

Impacts on Physical Spaces, Events, and Resources

A majority of respondents noted an overall decline in patronage of their physical libraries, with most citing people’s health concerns as a primary reason, especially among the elderly. The move from offline to online services during the pandemic, as noted above, has had implications for the attractiveness and suitability of existing physical spaces in the library, such as computer desks and play/social areas. Also, the nature, frequency, attendance, and administration of physical library events have also been impacted, for example, ‘programming events are now a ticketed event with number limitations’. One respondent observed that a sustained move to home schooling of remote students during the pandemic has led to these families using the physical library spaces more frequently. This is just one example of how remote libraries may need to adapt their spaces to new user groups and their needs by, for example, providing e-learning facilities.

The Pandemic Highlighted the Persistent but Evolving Value of Libraries

While only a minority of respondents said that the pandemic had changed things ‘a lot’ for their library service, there was evidence that this change had been positive in many instances. There is tension, however, between improved perceptions of the libraries’ value to community members and a struggle for libraries to attract pre-pandemic patronage levels and resource new programming. For example, while one respondent said, ‘People have come to realise that the library is a valuable service that and are relying on us more than ever,’ another pointed out that ‘a lot of consumers have kept away’. The data also indicates a change in the demographics of people who visit the library (i.e. fewer backpackers, travellers, and older people, but more families with home-schooled children). These results demonstrate that the value of libraries persists post pandemic, but is evolving according to community needs and priorities.

Supporting Users’ IT Needs

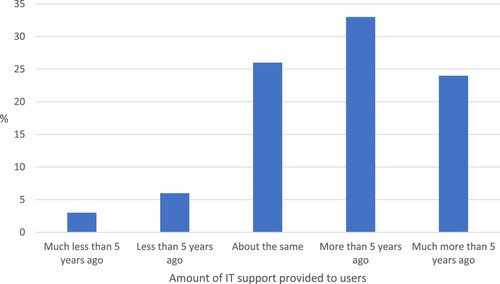

shows how Australian rural libraries are supporting their users’ IT and digital literacy needs more than they were five years ago. Indeed, almost a quarter are supporting their needs ‘much more’.

The Digital Needs of Communities are Varied

A minority of respondents, however, indicated that they are offering digital services ‘less’ or ‘much less’ than five years ago, with diverse reasons cited. Some respondents linked this decline to a lack of resourcing, such as limited funding and aging/failing computers in the library, as well of lack of skills/interest of the lead librarian. One respondent said they offer fewer digital services because digital services are now offered elsewhere, such as in a community centre. Others observed that some community members no longer require the IT assistance they used to because they ‘are confident in using their devices and now that there is more reliable and cheaper internet, people aren't coming in to use the computers’. This is further linked to patrons increasingly accessing the library online rather than in person. Conversely, other patrons are needing more, and more advanced, digital support than previously sought or offered. As one respondent noted, ‘There is less demand for the public computers, but this is translating into a higher demand for printing from mobile devices and assistance with understanding.’ The libraries’ digital services can differ widely depending on their local community’s needs and expectations, along with the in-house expertise, resourcing, and interest in providing such services.

Libraries are Offering More and New Digital Services

About 60% of respondents indicated that they have been providing more IT and digital literacy support work in the last five years. Respondents recognised that the pandemic has pushed people into using digital technologies to access the library and other services, and that patrons continue to expect these types of services as well as in-person services. Several had secured grants to deliver new digital programs, such as from the Good Things Foundation. More specific digital services that libraries have been providing more of in the last 5 years include: more PCs and tablets, dedicated computer areas, weekly digital literacy training, more printing/scanning, more accessible websites, and library apps. Overall, demand for such digital services continues to increase. As one respondent noted, ‘COVID [was] forcing people towards technology, and this trend [is] continuing.’

Librarians are Now Digital Mentors

As alluded to above, several respondents noted a dramatic increase in demand for one-on-one technical assistance. In responding to this need, librarians have become ‘digital mentors’. Patrons ask library staff for help with a plethora of activities on different devices including, but not limited to: accessing the internet, email, and social media; using digital library services (e.g. intra-library loans); completing online forms (e.g. tax, passports, visas); paying bills; online shopping; booking travel; accessing government apps; setting up SIM cards; accessing online education; and understanding cybersecurity. As one respondent put it, ‘In the past, we ran more formal training sessions … but people … want immediate help with their specific issues at the time they are experiencing their need.’ This marked shift in the tasks associated with librarianship have implications for staff capability and capacity. For example, while IT support is now a large part of the job, this requirement is unlikely to be noted in a position description and, therefore, to be resourced appropriately. One respondent observed that ‘it's remarkable how many we are able to help though staff are not specifically trained in the field’.

Libraries are Digital Islands in Remote Communities

Several respondents noted that, in the absence of telco shopfronts and IT support businesses in remote communities, the library is ‘a free first port of call’ for digital assistance. Many also said that other service providers in town (e.g. electrical suppliers) will often ‘send people to the library for assistance’. Furthermore, the digitalisation of government and banking services, and consequent closure of service centres in remote communities, leaves people with nowhere else to seek IT assistance. Others noted that the local aging population ‘do not have family members close enough to assist them’, and some cannot afford the devices and connections they need to effectively navigate the digital world. Remote residents, particularly the elderly, turn to the library as a safe and trusted service. As one respondent noted,

We help where we can. The online IT training that we receive is great, but customers often need help at the same time, so the training is missed. As we are a small library, we are often very busy with customers and other times no one but busy with other Library work and business.

Challenges

Asked to rate five themes as challenges for their library service, overall respondents were a little more concerned about budget, buildings and facilities, and community engagement, than they were about staff recruitment and retention, and technology. The median rating for the first three was ‘moderately’ a challenge, whereas the median for both the latter two was exactly in between ‘somewhat’ and ‘moderately’ a challenge.

The Need to do More with Less

When indicating challenges relating to budget, respondents described working with funds that cover little more than staff salaries. The outcome of budget challenges was reported as an inability to offer programs and services that are needed in the communities, or if attempts were made to offer these, libraries find themselves ‘stretched too thin’ to provide good quality offerings. Councils are encouraging libraries to do more with less to show ratepayers how well the council is operating on a lean budget. Some councils are also reluctant to spend more funds on their libraries due to a narrow, traditional view on what libraries do, or can do. One respondent observed that ‘the more traditional council and business members of this rural community believe that libraries are only for books and books are only for people who don't have enough work to do’. Another commented:

It is always a challenge to present the library to the elected members as the important institution that it is. The social capital it is contributing to a remote community is invaluable. Whilst people in leadership support the idea of a library, they rarely get really involved or fully understand what a modern library does.

Being in a remote part of a large local government area where individual towns are geographically isolated from their central governance body also creates budgeting problems. Respondents report that the joining together of small local councils into larger regional councils has led to small branches in the new region coming under pressure to merge or rationalise as a cost-saving measure. This leads to a reduction of proximate services for the more remote communities, and a loss of employment opportunities for library staff.

Staffing Recruitment and Retention Still an Issue

When asked to expand on the challenges they faced, staffing was also cited as a significant problem for many respondents. Libraries that are experiencing difficulties in recruiting sufficient staff identify their rural locations as a factor in the problem. A lack of suitably qualified local staff requires them to attempt to recruit from outside their communities. This proves difficult when there is a lack of housing available in the towns and when low rates of pay are offered by their governing council. These low rates of pay are also the cause of attrition of library staff who must move away to gain career advancement opportunities. Insufficient funds for salaries also affect casual labour, with employees unable to be obtain enough hours of employment per week to make library work an attractive option.

Libraries Squeezed in Shared Buildings

While many of the concerns expressed by respondents that relate to buildings and facilities, such as aging and repurposed buildings, are likely to also be experienced by libraries in non-rural areas, some concerns do relate to the unique nature of rural libraries. Community libraries that are shared with local schools face particular challenges, such as no access to bathroom facilities that are located elsewhere in the school, and a constant pressure to reduce in size as the schools attempt to accommodate the children of an expanding community by reclaiming library spaces for classrooms. Rural libraries that do manage to gain funding to repair damaged and aging buildings often face a shortage of local skilled labour, relying on city-based builders who are willing to travel to undertake this work.

Spread-Out and Itinerant Populations Less Likely to Visit

The most common challenge reported by respondents related to a decline in community usage. While some of the challenges reported are not unique to rural libraries, in particular a low level of engagement with children and youth due to their high levels of device use in their unstructured time, there were engagement challenges that would seem to be more common in rural communities. Libraries that serve farming communities have very low levels of engagement during peak periods of the farming cycle, such as planting and harvest times. In addition, some sections of rural communities are itinerant and don’t establish long-term residency or library use. Remote communities that are spread out over thousands of square kilometres often have only small numbers of people living in the towns, making it difficult for the majority of the community to pay regular visits to the library, and a decline in local media options has removed one successful way of promoting the library to users.

Sub-Par Technology

Technology-related challenges faced by rural libraries include aging hardware and software that cannot be replaced due to a lack of funds and cannot be repaired due to a lack of qualified IT support staff in their communities. In addition, poor digital infrastructure and internet connectivity in many rural and remote communities restricts the services and programs that their libraries are able to offer. Unstable electricity supplies in many rural areas also contribute to difficulties in offering online library services to communities, with one participant stating, ‘We are a very remote library service. Due to our location, power outages are common and make it very difficult to offer the community online services.’

Discussion

The survey findings portray a picture of libraries in rural areas of Australia that shows how they are performing similar functions to their more urban counterparts, and facing similar challenges, but also points to some ways in which they are especially valued by their communities and may play some even more important roles. Conversely, the indications are that typically their managers and staff are faced with some challenges that are even more acute than they are for public librarians working in metropolitan and inner regional areas.

Many libraries in rural Australia are located in quite small settlements, even though they may be serving a wider community of slightly larger numbers spread out over hundreds of square kilometres. These towns and townships are likely to offer only a very limited ranges of services and outlets for social interaction, making the library and its services of great importance. This may be particularly true for those patrons less well placed to make use of the other standard features of such towns (e.g. the pub or the sports club), including children and the elderly. Indeed, for some users it represents the only welcoming and safe place in town to go to.

Some of the rural library services and resources in most demand are those relating to IT and digital literacy. This demand has increased markedly over the past few years and since the COVID pandemic, with some rural libraries becoming ‘digital islands’ in communities that otherwise lack quality IT infrastructure and support. Correspondingly, some of the staff working in these libraries are being increasingly called upon to act as ‘digital mentors’. Many may be thriving in this role, but others may be less well-equipped for it.

The libraries of rural Australia do their best to provide the resources and services available to public library users elsewhere in the country, but struggle in particular to offer a wide range of programming, given their limited staffing, typically of just one or two employees. They also tend to be short of space, which can hinder the hosting of different activities. If they have their own building, it may well be quite old and outdated, while if they are sharing a building with other council services, or a school, or another organisation, there may well be competing demands on the facility.

Mobile libraries are still a feature of some rural library services, but do not seem to have progressed all that much since the heady days of the turn of the century, when vans of books were being converted into ‘branches on wheels’. The current fleet do provide a range of resources beyond books, and allow for some other activities beyond selecting and borrowing, but they are generally quite modest ‘branches’ and do not make very long stops at their target communities, nor do they make very frequent ones. The rural libraries’ outreach services otherwise mostly comprised basic online offerings, with some home delivery and visits to schools.

One of the biggest challenges for public librarians working in rural Australia is the aging infrastructure. Both the facilities and the technology tend to be in need of updates. Library staff recruitment and retention also remains a particular issue in rural areas. Perhaps most fundamental of all, however, is the enduring challenge of the tyranny of distance, no matter how many online options there might now be, in remote and regional Australia. Librarians working in these areas need to continue to work on ways to reach out to their prospective users: physically, they are still as spread out as ever, across sometimes vast distances. More research in this area would support these endeavours. As one respondent noted:

The traditional library service is not valued greatly, and it has been difficult to get new ideas and suggestions off the ground. Perhaps the biggest issue is that we don't have a lot of data about what works or does not work in remote settings which makes it more difficult to get new ideas off the ground and get senior management commitment.

Conclusion

This article presents the results of research undertaken to understand the roles of libraries in rural Australian communities, building on the small existing body of work. The findings shed new light on the make-up and characteristics of rural libraries as well as the enormous value they bring to rural communities. While rural libraries’ practices are in many ways similar to libraries in more urban areas, our survey demonstrates that their impact – through the contextualised delivery of library services to meet patrons’ needs – is widely felt across communities. Furthermore, with libraries being one of the few social infrastructure entities that remain in rural communities, their role is even more important. Rural libraries are resilient and responsive in the face of challenges that urban libraries often need not accommodate. More work is needed to understand how libraries can be better supported to maintain their relevance and effectiveness as climate change, digitalisation, and regionalisation present new challenge and opportunities for the communities of rural Australia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Australian Library and Information Association and the Australian Public Library Alliance for their support in the conduct of this research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Philip Hider

Philip Hider is a Professor of Library and Information Management in the School of Information and Communication Studies at Charles Sturt University. He has been researching in the field of Library and Information Science since the 1990s, specialising in the area of knowledge organisation.

Simon Wakeling

Simon Wakeling is a senior lecturer in the School of Information and Communication Studies at Charles Sturt University. His research interests include the role and function of public libraries, and scholarly communication, particularly the open access publication and dissemination of research outputs.

Amber Marshall

Amber Marshall is a lecturer in Management at Griffith University. Her research focuses on digital inclusion. Drawing on management and communication sciences, she employs socio-technical theoretical perspectives to investigate how individuals, organisations, and communities become digitally connected and adopt digital technologies in rural contexts.

Jane Garner

Jane Garner is a senior lecturer at the School of Information and Communication Studies at Charles Sturt University. Her research interests include those relating to library services to disadvantaged groups, most specifically adult and child prisoner communities, and those experiencing homelessness.

References

- Abu, R., Grace, M., & Carroll, M. (2011). The role of the rural public library in community development and empowerment. International Journal of the Book, 8(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9516/CGP/v08i02/36863

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/latest-release

- Australian Public Library Alliance, & Australian Library and Information Association. (2021). APLA-ALIA standards and guidelines for Australian public libraries. https://read.alia.org.au/apla-alia-standards-and-guidelines-australian-public-libraries-may-2021

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Data.gov.au. (2024). Progress in Australian regions and cities dashboard (December 2023 ed.). https://data.gov.au/data/dataset/fad540d4-7172-4a65-b51f-0b484120e2e3/resource/b783a476-4c7a-4184-bdee-c5a80333a595/download/2023-progress-in-australian-regions-and-cities-dashboard-dataset.csv

- Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. (2016). Progress in Australian regions yearbook, 2016.

- Edwards, E. (1988). What does the community expect from a country library? Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 1(1), 12–17.

- Garner, J., Hider, P., Jamali, H. R., Lymn, J., Mansourian, Y., Randell-Moon, H., & Wakeling, S. (2021). ‘Steady ships’ in the COVID-19 crisis: Australian public library responses to the pandemic. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 70(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2021.1901329

- Haines, R., & Calvert, P. J. (2009). Is isolation a problem? Issues faced by rural libraries and rural library staff in South Australia. The Australian Library Journal, 58(4), 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2009.10735928

- Henri, J., & Sanders, R. (Eds.). (1987). Rural and isolated libraries conference proceedings. Libraries Alone.

- Kenneally, A., & Payne, C. (2000). Mobile library services: Australian trends. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 13(2), 63–71. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p = AONE&u = googlescholar&id = GALE|A62761090&v = 2.1&it = r&sid = bookmark-AONE&asid = f973285f

- Knight, R., & Makin, L. (2006). Branches on wheels: Innovations in public library mobile services. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 19(2), 89–96.

- Latrobe Valley Regional Library Service. (1992). Mission and program objectives: Latrobe Valley Regional Library Service, Victoria. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 5(1), 41–45.

- Leary, J. (1991). Library services for isolated communities: A western New South Wales perspective. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 4(3), 150–154.

- Monley, B. (2006). Colocated rural public libraries: Partnerships for progress. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 19(2), 70–75.

- Nakata, N., Nakata, V., Anderson, J., Hunter, J., Hart, V., Smallacombe, S., McGill, J., Lloyd, B., Richmond, C., & Maynard, G. (2007). Libraries and knowledge centres: Implementing public library services in remote indigenous communities in the Northern Territory of Australia. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 38(3), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2007.10721297

- National and State Libraries Australasia. (2023). Australian public libraries statistical report 2021–22.

- Osman, K., Marshall, A., Rogers, J., & Wilson, C.-A. (2023). State library of Queensland digital inclusion programs evaluation, 2016–2022. Queensland University of Technology. https://research.qut.edu.au/dmrc/projects/state-library-of-queensland-digital-inclusion-programs-evaluation

- University of Adelaide, & Australian Centre for Housing Research. (2023). Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+).

- Wakeling, S., Kennan, M. A., Hider, P., Jamali Mahmuei, H. R., Mansourian, Y., & Randell-Moon, H. (2023). Understanding the needs of public library users in a COVID-changed world: Report prepared for the state library of New South Wales. Charles Sturt University.