ABSTRACT

This paper considers Sino-Uzbek relations by critically assessing the positivist depictions of CA states in their relations with larger countries like China. It uses the post-positivist and constructivist framework and adaptations made from the four-factor analysis framework adopted in the case of Uzbekistan to demonstrate avenues in which Uzbekistan demonstrates active agency in relations with China. This paper argues that Uzbekistan and other CA states utilize nudging strategies which refer to a subtle and often indirect way of encouraging or guiding China’s behavior in a particular direction as opposed to so-called “nagging” which associates with persistent and repetitive pressuring China to perform a certain function. Accordingly, Uzbekistan’s approach to China can be described as the nudging strategy of designing the environment or context which makes China’s choices in its relations with Uzbekistan easier and more attractive in favor of policy decisions desired by the Uzbek government. As is depicted in the narrative of cooperation road maps, Uzbekistan’s approach involved both indirect signaling of certain policy preferences, choice-preserving (involving diversification of foreign partners), and positive reinforcement (through various policy incentives). This contrasts the persistent and repetitive pressuring, criticism, threats, or guilt-tripping, seen in relations between China and other Western states.

1. Introduction

The coverage of relations between the Central Asian states and their larger international counterparts like Russia, China, and the US has frequently been interpreted through the prism of Chinese and Russian neo-colonialism and domination, East-West rivalry, debates on CA states’ clientelism, and the “never dying” old “new” Great Game rhetoric. These frames have seen a new momentum in recent history with anti-governmental protests in Kazakhstan in early 2022 and a Russian “special operation” in Ukraine that began in early 2022. These recent developments demonstrate that the issue of how international affairs in the regions that emerged after the dissolution of the USSR should be narrated remains among the most debated topics in international media and academic discourses. Media and academic coverage are frequently dominated by the projection of intentions and images of larger actors such as the US, Russia, and China, while the analysis of the behavior and the narrative of the very states at the center of regional development remains underplayed, overlooked, or ignored.

With respect to the CA region, this media and academic framing presents two problems. The first is that while there are global attempts to critically engage with the dominant narratives regarding the global South and to provide the local perspectives that need to be further involved in a global dialogue on how to construct inclusive international relations, Central Asia remains ignored and frequently forgotten in such attempts. Accordingly, Chinese, Russian, American, and other global powers’ goals in the region are paid extensive attention to and widely discussed in the literature from various perspectives,Footnote1 while the CA regional states’ approaches are either highjacked by these global narratives or not provided at all.

The second problem is that the narrative of CA governmental approaches, in those rare studies available, is often presented in a static structure as a snapshot of CA attitudes toward greater powers that is then generalized as representing their attitude throughout different times and changing international environments. This is partly the reason why the CA states’ international relations with greater powers are still narrated through the centuries-old Great Game and other rivalries,Footnote2 as analyzed below. This brings to our attention the need to re-focus not only on what the structure of the relationships of these smaller states are with the global powers in a given period of time but also the need to analyze how and in what way this has changed over that period. In addition, the ability and logistics involved in how these states change and adapt to the global powers and their competition/cooperation paradigms also need to be nuanced and provided with empirical and conceptual detail.

The relationships of the CA states with China is a good opportunity to both demonstrate the deficiencies of the field of IR in narrating the agency of smaller international actors and to emphasize the strategies of these states to leverage potential attempts by larger states to establish a mentorship structure of relations instead of a partnership. Over the last 30 years, the role and place of China in the policies of CA regional states have evolved from China being a developing country in their vicinity, to China growing into an economic and political superpower. Thus, its influence has been interpreted and evaluated through various lenses over the years. On the one hand, the Shanghai process of demilitarizing the borders between Russia, CA, and China from 1993 onwards to the Shanghai five in 1996, which eventually transformed into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001, offered a certain degree of security and political stability to this region.Footnote3 Paired with Chinese development projects similar to the Belt and Road Initiative announced in Kazakhstan in 2013,Footnote4 China’s influence has been seen by some observers as offering a decolonizing alternative to over-excessive reliance on Russian energy and transportation infrastructure for the regional states.Footnote5 On the other hand, the increasing dependency of CA states on loans and grants from China in recent years, which in certain countries in the region (such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) constitute up to 70% of their national GDP, causes concerns about Chinese neo-colonizing tendenciesFootnote6 that sotto voce are pictured as an attempt by China “to deepen trade imbalances, targeted spending in infrastructure and debt under the BRI that supports China’s ambition to achieve political goals in Central Asia.”Footnote7 Some others speculate that although relations with BRI states might not necessarily have the tendency to neo-colonize these states by allowing them access to the economic advantages of Chinese economic growth, its influence displays the aspects of what they call the Chinese “neo-tribute system” which attempts to solidify the domestic legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party by strengthening ties with BRI states.Footnote8

In a separate group of studies, there is also discussion of Chinese and Russian attempts to either divide their influence along the lines of security (dominated by Russia) and economy (dominated by China)Footnote9or create a greater Central Eurasia,Footnote10 or a kind of “condominium over Eurasia” (Rolland, Citation2019). In an alternative framing, the involvement of China, Russia, the US, Turkey, Japan, India and others is considered to be part of the geopolitical games for influence and domination in the region.Footnote11 However, these conceptual constructs, although useful in describing various perceptions of the CA region, do little to provide narratives and voices for the local actors from the position of CA states, attributing only band-wagoning roles and the image of being “guided” by Russia or China to them.Footnote12

Those studies that provide room for the discussion of CA’s policies, do provide explanations of how these countries attempt to utilize opportunities offered by China by creating trade zones,Footnote13 or offer economic domestic concepts such as Kazakhstan’s Nurli Zhol to fit BRI.Footnote14 However, these important studies focus on a certain period of time or a particular policy event without necessarily providing an analysis of the process of construction and continuity of Sino-CA relations. To compensate for this insufficiency in the previous literature, this paper pursues the following sets of questions to provide an alternative framework for the analysis of relations between the CA states and China and to demonstrate the tools they need to employ to maximize the benefits of this cooperation while minimizing the dangers of being neo-colonized by China. These are: What are the ways through which CA states leverage Chinese influence in their countries? What are the priorities of CA governments that relate to the Chinese economic agenda? What is the process of leveraging Chinese priorities with the priorities of its CA counterparts?

This paper argues that Uzbekistan and other CA states utilize nudging strategies which refer to a subtle and often indirect way of encouraging or guiding China’s behavior in a particular direction as opposed to so-called “nagging” which associates with persistent and repetitive pressuring China to perform a certain function.

The methodology of this paper is three-fold: First is to place Uzbek-Chinese relations into the dominant literature on relations with China. By doing so, this paper aims to theoretically narrate the strategy employed by Uzbekistan in leveraging the Chinese agenda. Second, is to analyze three sets of cooperation road maps (2017, 2019, 2022) between Uzbekistan and China in order to empirically demonstrate the way in which Uzbekistan’s cooperation agenda relates to the announced Chinese intentions. And third, is to reflect on the social environment for an Uzbek-Chinese agenda by providing a summary of interviews with Uzbek policymakers (politicians, bureaucracy, think tank, and University representatives) conducted in Uzbekistan from February 11–24, 2023, and contrasting that summary with the views of youth extracted from several recent public polls.

The narrative of this paper has the following structure. The first section critically assesses the positivist depictions of CA states in their relations with larger countries like China. This section then outlines the post-positivist and constructivist framework and adaptations made from the four-factor analysis frameworkFootnote15 adopted in the case of Uzbekistan to demonstrate various avenues in which it demonstrates active agency in relations with China. The second section provides an analysis of bureaucracy as an important factor in shaping the Uzbek responses to various Chinese investment interests. The third section details the structure of economic cooperation and the actors involved in it as described in pre-pandemic cooperation roadmaps between China and Uzbekistan. The fourth section then focuses on the outcomes of the initially drafted cooperation road maps as depicted in the cooperation roadmaps of 2022. And the final section details people’s emotions, perceptions, and identity in placing China among the other cooperation partners of Uzbekistan.

In doing so, this section uses generated data from expert interviews with Uzbek stakeholders who participate in the formulation of Uzbekistan’s China agenda. This section also features analysis of the public polling run by AsiaBarometer and Central Asian Barometer between 2005 and 2020. This polling data, although not all-inclusive, informs on the way Uzbek youth perceives Uzbekistan’s cooperation partners including China. The focus on youth is especially important because the population of Uzbekistan is predominantly young with more than half of its 35 million people under 30 years of age. In conclusion, this paper then extracts the factors considered important for effectively internalizing Chinese projects into the developmental agenda of developing countries as demonstrated in our case-study of Uzbekistan.

2. Partnership, not mentorship: theoretical framing of Sino-Central Asian relations

In narrating the relations of CA states with their larger counterparts like China, scholars of CA international relations explain the motivations and strategies of smaller CA states through a number of frames. First, for a large part of their post-independent development, the CA region has often been considered to be part of the Russian sphere of influence whose behavior is closely related to the Russian foreign policy agenda.Footnote16 Similarly, the Russian narrative of Eurasian identity and destinyFootnote17 for CA states often overshadows the intentions and trajectories as understood by regional CA states.

Second, a number of studies have emphasized the importance of various foreign policy initiatives of China in recent years such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) or those related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in narrating the role of China in the CA region and explaining the interactions of the regional states with bigger states like China.Footnote18 Although these initiatives are important for regional development, excessive focus on Chinese intentions and frameworks hijacks the discussions of the goals and strategies of smaller CA states in interactions with China.Footnote19 Such a China-centered narrative also oversimplifies the structure of these regional engagement schemes to the “Great Game” type of rivalry with the US and even Russia,Footnote20 or a structure within which China and Russia are engaged in a “regional Great Game” of a kind.Footnote21

Following these depictions, the CA states’ rational choice is to hedge and balance through so-called “multivector” diplomacy.Footnote22 Hedging is a middle-ground between “pure balancing” and “pure bandwagoning”,Footnote23 and according to Kuik, it “exhibits elements of both power-acceptance (manifest in some forms of selective partnership, collaboration and even deference vis-à-vis a power) and power rejection (some signs of selective resistance and defiance vis-à-vis the same power)”.Footnote24 Such hedging, as exemplified by ASEAN’s behavior toward China is considered to be “one of the many forms of alignment behavior”.Footnote25 Some recent studies applied ASEAN “hedging” of China to the CA regional context.Footnote26 Following the ASEAN blueprint, they claim that CA states hedge China institutionally (in various regional engagements), economically, and in terms of security. According to these studies, the so-called “multi-vectoral” diplomacy and “‘heterarchy’ (or the existence of multiple hierarchies)”Footnote27are preconditions for successful “hedging” in the Central Asian region. As a result, they identify Kazakhstan as a heavy hedger while Uzbekistan is an emerging heavy hedger.

Although the notion of “hedging” can be an interesting angle to narrate the strategies of ASEAN countries, its applicability to the CA region needs further elaboration. In particular, manually copy-pasting ASEAN strategies of the hedging China to the CA region context would automatically imply that the CA regional states are presented with the choice of “Power Rejection,” “Neutrality” or “Power Acceptance”Footnote28 with respect to the Chinese, Russian or US policies. This would also mean that there are certain clearly defined goals that China and other states have for the CA region, and CA states are only in a position to accept, reject or ignore these blueprint goals because they also have their own solidified positions in respect to China. If we accept this logic, we need to accept the notion that the national interests and goals of China and CA states in their relations are given and pre-defined. We also need to ignore the process of mutual influences and the construction of each other’s goals and objectives when defining common approaches between these states. As such, applying a “hedging” framing of relations between China and CA states would follow the positivist understanding of IR by accepting the static and unchanging structure of national interests and goals and overlooking the actual process of the social construction of relations between states. Such a stance would also have to ignore the situations where states do not necessarily face the choice of having certain predefined policies imposed simply because these policies (be they Chinese, Russian, or other) are mutually constructed in a concerted manner in various operationalizable formats of inter-governmental negotiations.Footnote29

To a great extent, these are reflective of the positivist (realist or liberalist) perspectives in IR and impose the real-politic structure of relations between various states in the CA region and underestimate their decision-making capability in regard to international affairs. According to this flow of studies, CA states’ agency demonstrates itself in their ability to trade on their loyalties (or other currency) to Russia, the US, and China.Footnote30

Third, in response to the positivist claims above, there are several studies that develop a country-specific approach, detailing on how Kazakhstan attempts to leverage Chinese influence through a number of projects in the agriculture and food processing industry.Footnote31 They also argue that Kazakhstan successfully leverages Chinese interest in energy-related projects by complimenting these projects with projects in industrial development, transportation infrastructure, “renewable energy, finance, industrial parks, manufacturing, mechanical engineering, and metal mining and metallurgy” to mention a few.Footnote32 Some of these studies also offer an interesting comparative perspective of projects between Kazakhstan and China, South Korea, and Japan.Footnote33 According to them, Kazakhstan attempts to connect its own Nurli Zhol development strategy to the China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) at regional and subregional levels.Footnote34 The value of these studies is that they provide much-needed detail and empirical data to suggest that there is no evidence of Chinese domination in the economic agenda setting between Kazakhstan and China and that Kazakhstan benefits from its cooperation with China not only in energy-related fields.

At the same time, these studies, although very valuable to our discussion, do not necessarily focus on the tools of intergovernmental bargaining and on the question of how this leveraging is achieved. Although Bitabarova advances our understanding of economic bargaining between the two countries by pointing to the roles of the Kazakh-Chinese Coordination committee as well as the Kazakh-Chinese Business Council, the analysis of negotiation mechanisms and tools is left outside of the scope of the coverage of this study.Footnote35 Earlier studies on intergovernmental bargaining and cooperation plans between China and Uzbekistan demonstrate that there are certain degrees of complementarity between the priorities of these countries prior to the pandemic, especially in the fields of infrastructure development, energy exploration and manufacturing.Footnote36 However, these studies left the task for the comparative analysis of patterns of changes in the developmental agenda of cooperation road maps in different periods of time.

The current paper builds on these perspectives of relations between CA states and larger states such as China by focusing not only on the kind of projects present in the cooperation agenda between Central Asian states and China but importantly on the tools of intergovernmental bargaining and how diversification of the economic agenda is changed over a certain period of time. Although Kazakhstan has received much-deserved interest in its economic cooperation with China, this paper uses the case of Uzbekistan, which shows signs of achieving the most dynamic progress in the CA region both demographically, socially, politically, and economically since the death of its long-term first President Karimov in 2016 and the consequent change in its leadership, as detailed below. In order to trace the patterns of change, this paper focuses on the cooperation road maps for the pre-pandemic (2017, 2019) and pandemic (2022) years.

In terms of a theoretical framework, this study adheres to the constructivist theory of international relations by suggesting that interactions between Uzbekistan and China are subject to social construction which is impacted by their continuous interactions (through developmental projects), social international environment, the vision of “self and the other” as well as subjected to the influences of regional socialization in CA region.Footnote37 This theoretical reasoning is also in line with a four-factor analysis framework emerging as a preferred approach to analyzing the relations of China with other Asian states.Footnote38

To operationalize the constructivist narrative for the analysis of Sino-Central Asian relations, this paper adopts the pentagonal analytical frameworkFootnote39 for the analysis of projects and initiatives included in the cooperation road map in four areas: (1) Political-diplomatic (by focusing on cooperation bureaucracy); (2) economic development (subdivided into infrastructure, energy, and manufacturing); and (3) social perceptions and cultural ties (for details of this approach see Dadabaev, Citation2014). This operationalization covers such factors as a) domestic politics, (b) economic interests, (c) international environment and security, and (d) people’s emotions, perceptions, and identity in considering the impact of Chinese initiatives on developing countries.Footnote40

To further develop the pentagonal model, this study also adds important criteria of analysis such as the dynamics of change. This is done to emphasize that relations between the states (in this case of Uzbekistan and China) are the outcome of social construction over a certain period of time. They cannot be understood by just providing a snapshot of their relations for a given short time period. For this purpose, this paper considers the processes of construction of Sino-Uzbek relations through the dynamics of bureaucracy and then analyses how the cooperation roadmaps between Uzbekistan and China have evolved from 2017 to 2022 by providing the details and specificity of each year and then analyzing the initial outcomes.

In terms of the used strategy, Uzbekistan’s approach to China can be described as the nudging strategy of designing the environment or context which makes China’s choices in its relations with Uzbekistan easier and more attractive in favor of policy decisions desired by the Uzbek government. As is depicted in the narrative of cooperation road maps, Uzbekistan’s approach involved both indirect signaling of certain policy preferences, choice-preserving (involving diversification of foreign partners), and positive reinforcement (through various policy incentives). This contrasts the persistent and repetitive pressuring, criticism, threats, or guilt-tripping, seen in relations between China and other Western states.

3. Uzbekistan-China relations as harbinger of leveraging

Due to the differences between the economic, social, political, and geographic positions of CA states, namely Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, the coverage of the relations of all of them with China are difficult to cover within the confinement of just one paper. Therefore, this paper chooses to focus on the cooperation road maps between Uzbekistan and China as a representative example. The choice of Uzbekistan for the analysis of this study was made for a variety of reasons: it is centrally located in the region bordering all five CA states and is the most populous country in the CA region. Uzbekistan is also one of the most dynamically developing economies in the region and is geographically located in the center of transportation and energy transportation networks. The new opening of Uzbekistan to the world started in 2016 with the death of dictatorial President Karimov. This led to new reforms in Uzbekistan and opened the country to various partnerships.

In this sense, Uzbekistan is a country that is critically important for the development of the region and can in many ways throw light on the challenges faced by regional countries in their relations with external powers. In addition, (unlike Kazakhstan which is part of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Community) Uzbekistan is not part of any political or economic blocs with Russia or China and does not have borders with any of these powerful states, making its political standing a more neutral one when compared to the one presented by Kazakhstan in its relations with China. The structure of the Uzbek economy also signifies a more balanced approach to its economic partners with a limited degree of dependence on Russia (the Eurasian Economic Community and Eurasian Economic Union) or on China (the share of debt is comparatively low), when compared to its regional neighbors such as Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan.

In terms of foreign policy engagement, Uzbekistan transitioned from a policy of isolationism signified by years of the dictatorial rule of Islam Karimov (1991–2016) to an open-door economic policy in 2016. Islam Karimov’s isolationism and authoritarian rule was largely in response to the initial challenges Uzbekistan faced in the early years of independence. As a remedy for Western criticism of his authoritarianism, Karimov’s government closed the country to foreign influences under the pretext of defending Uzbek sovereignty. He securitized his foreign policyFootnote41 and attempted to balance foreign influences, switching his foreign policy priorities from one country to another when the situation dictated. This is exemplified by the various periods of close cooperation with various countries, such as Russia in the early 1990s, Turkey in the mid-1990s, and the US in the early 2000s. However, Karimov’s rapprochement with the United States from 1999 to 2005 switched toward closer China relations in later years.Footnote42 In such drastic policy changes, the defense of Uzbekistan’s sovereignty has been interchangeably fused with the notion of the personal survival of Karimov.Footnote43 The major point of constraint in such a foreign policy decision-making system was that it left no space for other interests, actors, and (subnational or regional) initiatives not associated with Karimov.Footnote44

After Karimov’s passing in 2016, the new administration under President Mirziyoyev recognized that such a policy resulted in the decay of the Uzbek economy and the isolation of the country.Footnote45 To forge business-to-business ties, President Mirziyoyev liberalized the visa regime, abolishing entry visa requirements for most of its major international partners and welcoming foreign direct investments into what were once considered strategically important sectors (such as energy, agriculture, and industry). On par with this, it loosened controls over labor resource movement (liberalization of residence registration) within the country. It abolished the requirement that Uzbek citizens’ receive so-called “exit” permits every 2 years and instead introduced passports for foreign travel valid for 10 years. The current administration emphasizes economic growth and diversification of international partners as the only way to achieve the desired regional and global significance of the country. In doing so, President Mirizyoev reformed the MFA to almost exclusively serve the purpose of facilitating foreign direct investments. It went even further by initiating the merger of the MFA and the Ministry of Foreign Trade to signal to international partners that Uzbekistan is not interested in trading political favors to various regional powers but aims to maintain equal relations with all powers to prioritize the goal of turning it into the economic hub of the region.Footnote46

According to the National Committee for Statistics, Uzbekistan’s overall trade over in 2022 reached $44.95 billion, an increase of $6.84 billion, or 18%, compared to January-November the previous year. Since the beginning of the year, exports rose to 17.36 billion (+12%), and imports to 27.59 billion (+22.1%). In terms of the goods and services exported from Uzbekistan, manufactured goods (23.1%, $4.01 billion) and services (20.8%, $3.62 billion) constitute the majority of the exports followed by exports of gold (20.3% or $3.53 billion).

The data for January-November 2022 () also demonstrate that Russia regained the position of the leading foreign trade partner for Uzbekistan with an overall volume of USD 8.34 billion and a share of 18.6%. The volume of exports from Uzbekistan to Russia increased by 49.5% equaling $2.8 billion while imports increased by 17.3%, to $5.54 billion. China, which in the past years has featured as the leading trade partner for Uzbekistan dropped to second place in 2022 with overall trade equaling $8.18 billion, constituting 18.2% of its overall trade. According to the Chinese statistical reports on imports from Uzbekistan to China, sales of gas since the beginning of 2022 amounted to 1.03 billion dollars, and in November 114.2 million dollars. However, at the end of 2022, the government of Uzbekistan indicated that it intends to halt all exports of natural gas due to the increase in domestic consumption triggered by the enhanced economic activities of domestic enterprises. If implemented, this has the potential to trigger a change in the patterns of trade between the two countries and potentially influence the place of China in the overall trade with Uzbekistan.

Table 1. Trade between Uzbekistan and its major trading partners, in USD millions.

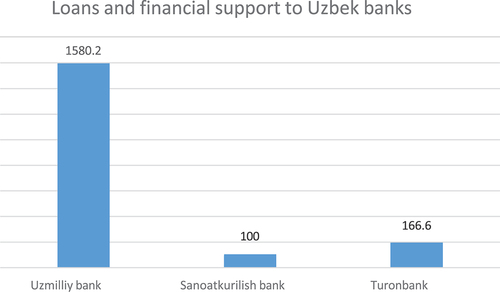

China is followed as a trade partner by Kazakhstan with $4.19 billion (9.3%), Turkey (6.5%) with $2.93 billion, and the Republic of Korea with $2.17 billion (4.8%). In terms of trade dynamics, trade with Russia and China is growing at a high rate (26.7% and 21.6%, respectively). In order to realize investment projects, Uzbekistan also relies on loans from international financial institutions (). However, its public debt is relatively balanced in terms of lending institutions and ratio to GDP. It reached $26.2 billion (34.1% of GDP) in late 2022. Despite the growth of the national debt, its ratio to the country’s GDP decreased from 38% at the beginning of 2022, to 34.1% as of October 2022. According to the Ministry of Finance, this was helped by the economic growth of 5.8% in the third quarter, a decrease in external public debt by 1.7% due to the repayment of $823 million, as well as diversification of the loan portfolio, and changes in exchange rates (Japanese yen, SDR, euro, Korean won, and Chinese yuan), which led to a decrease in the balance of the public debt. At the same time, in January-October Uzbekistan signed 16 new agreements on public debt worth $2.059 billion and issued government bonds worth 6.7 trillion Soum. However, in 2021 and the first nine months of 2022, the government provided no guarantees on domestic liabilities.

Table 2. Breakdown of public debt by sectors, Ministry of Finance of Uzbekistan, 2022.

Table 3. Breakdown of debt by institutions in 2022 Ministry of Finance of Uzbekistan, 2022.

Table 4. Breakdown of debt by currencies in 2022 (2021) Ministry of Finance of Uzbekistan, 2022.

As a tool for mid-term planning, Mirziyoeev actively utilizes the notion of so-called “road maps,” which are supposed to be a plan of step-by-step implementation of measures to achieve policy objectives in cooperation agenda with various countries. Although the snapshot of economic cooperation road maps for individual years for Uzbekistan has been analyzed in the past,Footnote47 this study traces how the articulated plans (in the developmental strategies of 2017–2021 and 2022–2026) that were outlined in roadmaps for various years (2017, 2019, 2022) evolved over the period of time thematically and otherwise.

Through the analysis of the thematic evolution of cooperation road maps between Uzbekistan and China, this paper suggests that along with China (and its Belt and Road Initiative), Uzbekistan is also engaging in the construction of its own narrative about the role and place of China in its foreign and domestic policy. For Uzbekistan, the Chinese goals of building transportation and energy infrastructure are only important because they offer the opportunity to diversify its industrial base, attract investment into processing its natural gas and other energy resources into value-added products that can then be exported with higher added value to markets in Russia, the CA regional states, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey, and the EU. In this sense, the Uzbek approach toward internalizing Chinese initiatives is driven by the notions of “practicality” and “functionality” which are the key emerging bricks in constructing trust and norms with China.

4. Bureaucracy as a stakeholder?

The role of Uzbek economic bureaucracy in facilitating inter-state economic relations and trade with China and other parties as mentioned above is significant if not detrimental (see ). In this sense, it is an important stakeholder in Sino-Uzbek economic ties. This contrasts with the conventional structure of relations between the liberal free-market economies in which it is the private enterprises that are the main stakeholders in decisions to invest in certain markets. Although Uzbekistan has transitioned toward a market economy, the main sectors of its economy still have a large share of state participation, while China’s economy is carefully managed through various channels of governmental signaling. That is the reason why the economic cooperation between the two countries cannot be discussed without including governmental facilitation of this process. The process of compiling and implementing cooperation roadmaps is such a process.Footnote48

There are two ways in which intergovernmental bureaucracy serves as the indispensable stakeholder in compiling cooperation road maps between Uzbekistan and China. First, the way to define and announce developmental goals in Uzbekistan and China displays a certain degree of similarity. In post-Karimov Uzbekistan, the Development Strategy 2017–2021 was the first such strategy, that outlines important goals and objectives for Uzbekistan’s economic development when approaching foreign counterparts.Footnote49 It was followed by the Development Strategy of 2022–2026, which has 7 priority areas with 100 goals disbursed over these 7 areas. Cooperation roadmaps with China and other countries serve the purpose of meeting these goals and objectives.Footnote50

Second, the bureaucracy which facilitates negotiating process between the two countries bears certain responsibility not only for the facilitation of negotiations but also for producing tangible outcomes. The major stakeholders on the Chinese part are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Development and Reform Commission, and the Ministry of Commerce.Footnote51 The stakeholders on the Uzbek side consist of the Ministry of Foreign Trade, the Chamber of Commerce, and the Agency for Foreign Investments while the Cabinet of Ministers plays a coordinating function. The intergovernmental committee is composed of a number of subcommittees (ex: trade and economy, transportation, energy, etc.) coordinated by the relevant ministry/agency from the Uzbek and Chinese sides ().

Figure 2. The structure of communications in drafting road maps between China and Uzbekistan (2017–2022).

Even when agreements are reached between private enterprises, the governmental bureaucracy in Uzbekistan continues to retain certain controls on the pace of the implementation of these projects. This is not typical for countries with liberal market economies, but it is acceptable to Chinese corporations, and it is an accepted practice in Uzbekistan’s bureaucratic process.Footnote52

The negotiations between stakeholders are either conducted directly between the actors during the direct visits to the sites where the projects are planned or addressed through the embassies. When the Chinese stakeholders require feasibility studies visits, these are first arranged through the Ministries of Foreign Affairs.

Various projects and proposals received by the foreign missions and ministries are passed on to the so-called intergovernmental committee on cooperation (created for cooperation with all major partners) and its subcommittees responsible for a particular economic sector. They serve as channels of communication and a bargaining table functioning on an ad hoc basis throughout the year (see ). They help “to signal certain policy and priority changes for each country and provide coordination for enterprise activity.”Footnote53 The proposals are then itemized into agreements, statements of intent (memorandums) and hard/soft contracts to be included in cooperation road maps. Finally, there are certain similarities in the decision-making of Uzbekistan and China which facilitate smoother cooperation at the level of governmental bureaucracy.

5. Pre-pandemic roadmaps: infrastructure, resource, and manufacturing sectors

The pre-pandemic road maps, on the side of Uzbekistan, have been significantly influenced by goals set in the Developmental Strategy of 2017. This strategy defined five main priority areas to be targeted by governmental policy. In relation to foreign counterparts, priority area 3 (areas of economic development and liberalization) has been of particular focus. In drafting roadmaps with China, the subgoals 3.2 (modernization and diversification of economy), 3.3 (modernization and development of agriculture), and 3.4 (privatization of state property and increase in small and medium-size enterprises)Footnote54 have been signposts for Uzbek bureaucracy in defining priority projects. As a result, one of the first road maps generated by both countries was the one signed in May 2017.Footnote55 This consisted of 11 intergovernmental agreements, one inter-municipal agreement, and contracts (totaling US$22.8 billion). In line with the developmental strategy of Uzbekistan, the road map of 2017 mainly focused on the areas of infrastructure, resources, and manufacturing/export-oriented industries (see ).Footnote56

Among the most anticipated outcomes (both by the Uzbek and Chinese sides) was the agreement on the increase of the volume of international road transportation for commercial loads between the two countries.Footnote57 In line with these plans, the rail and roads in the Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan-China (Andijan in Uzbekistan and Kashgar in China, via Osh and Irkeshtam in Kyrgyzstan) routes were strongly supported by Uzbekistan to open a direct corridor into the Chinese market.Footnote58 Both sides agreed to intensify negotiations not only between themselves but also with Kyrgyzstan without which such a road would have been impossible.Footnote59 The negotiations with Kyrgyzstan continued until 2022 when Uzbekistan announced (in January 2023) that it had reached an agreement with Kyrgyzstan on the construction of roads.

The second broadly defined area supported by both sides included agreements on the joint production of fuel, energy-resource processing, and the construction of energy generation facilities. This largely reflects the Uzbek domestic and CA regional demand for facilities to process local resources and to produce cement, metals, and glass-related products (with Zhejiang Shangfeng Building Materials for cement)Footnote60 and with MingYuan Silu for glass production.Footnote61 This area also includes investments in energy resource extraction (example: a plant to produce synthetic fuel in Shurtan co-financed with the Chinese Development Bank).Footnote62

The third area () constituted contracts for Uzbek exports of mineral and natural resources (natural gas, textiles, agricultural products, etc.). There were also several contracts for the modernization of energy and hydro-energy generation equipment (example: Chinese Ministry of Commerce and Uzbekgidroenergoqurilish JSC),Footnote63 contracts for coal extracting equipment (China Coal Technology & Engineering Group)Footnote64 and production of biomass (Uzbekneftegaz, AKB Agrobank, and Poly International).Footnote65 And the last large area of cooperation was defined as facilitating the establishment of manufacturing facilities in Uzbekistan by Chinese enterprises such as the assembly of elevators,Footnote66 toysFootnote67 (see ), ceramics (example: Zhongguo Jingdezhen Porcelain) as well as high-quality paper production plants (example: Sun Paper Industry and China National Complete Plant Import & Export).

Table 5. Selected examples of the projects included into the roadmap of cooperation between China and Uzbekistan compiled in 2017.

The second set of roadmaps compiled in 2019 are to a great extent a continuation of the 2017 roadmaps (). In addition to the areas above, job creation in Uzbekistan was added as a special emphasis in the follow-up to the 2017 road maps. To secure both job creation and local resource processing several initiatives were forwarded by 2019 roadmaps which included cotton-processing and textile mills in the Qashqadarya region during 2017–2019.Footnote68 The newly established Jizzakh economic zone was designed to host facilities to process locally produced leather and metal into final products (ex: Wenzhou Jinsheng Trading).

Table 6. Some examples of the projects included in the roadmap of cooperation between China and Uzbekistan compiled in 2019.

Interestingly, this set of roadmaps also included security-related components which provided for the wider involvement of China in the pacification and development of Afghanistan (see security-related projects in ). However, this focus is also connected to the infrastructure needs of Uzbekistan as it hopes to construct a railway from Uzbek Termez toward Pakistan with access to the sea, which for a double-land-locked country like Uzbekistan is of crucial importance. By attracting China to infrastructure-related projects in Afghanistan, Uzbekistan hopes to find a co-financing partner capable of sharing the burden of constructing such infrastructure. This could also potentially become the subject of co-financing from the Asian Bank of Infrastructure and Investments and the Belt and Road associated project.

6. Post-pandemic roadmaps 2022: domestic regional development, manufacturing, and renewable energy

By January 2022 however, the scale of the roadmaps and the amounts of investments indicated in them had somewhat decreased, to USD13.6 billion. Post-pandemic roadmaps were influenced by two main factors. The first is a reevaluation of “self” by Uzbekistan in a format of reshaping its development strategy for 2022–2026 and using it as a guide for reshaping its roadmaps for cooperation with China. In these roadmaps Uzbekistan reassessed its prior goals and engagements and defined more nuanced targets. This also represents a “maturing” of certain projects with those considered feasible transitioning to the stage of implementation, while those difficult to implement were eventually canceled. Of the seven priority areas, area 3 (development of the national economy) in particular was applied to drafting new roadmaps with China as the main guideline.

In particular, projects were drafted to fulfill Goal 23 (increase investments into geological explorations), Goal 25 (development of the digital economy), and the Goal 26 (attract investments into the economy over the next five years in the amount of USD 120 billion, including 70 billion dollars of foreign investment). Goal 26 in particular refers to Chinese investments and specifies the need to develop “investment and foreign economic relations of the Syrdarya region with the People’s Republic of China” as the province where Chinese investments are of particular importance. This is also related to Goals 28 (an increase of export capabilities) and 29 (an increase of the private sector in the overall structure of the economy to 80% of GDP and 60% of exports).Footnote69

The second obvious reason is the impact of COVID-19 on the previous projects many of which were delayed or canceled altogether. The COVID-19 pandemic severely restricted access to funding, and the physical movement of people and slowed down general economic activities in both countries. As a result, by the beginning of 2022, the number of announced investment plans was 133 over the period 2017 to 2022. Of these plans, the number of projects which were successfully accomplished reached 36 projects amounting to almost USD 6 billion (USD 5.954 million). The projects which are considered to be in the process of implementation number 84 with the projected amounts of investments being at around USD 7 billion (7.089 million). There are 10 main projects which are behind schedule in terms of implementation amounting to USD566 million while three projects have been canceled (amounting to USD 31 million).

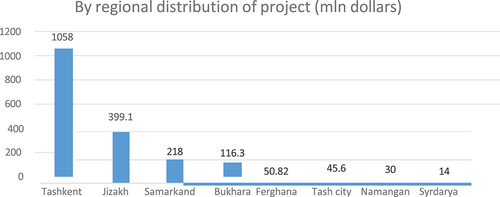

The focus of the recent roadmaps as modified at the beginning of 2022 demonstrate that government planning and channeling of the China-related projects favors a more balanced regional distribution of these projects throughout Uzbekistan. For instance, in early roadmaps, the Tashkent and Tashkent region of Uzbekistan featured prominently due to it having a developed infrastructure and access to international transportation networks. Since then, the government-subsidized improvement of domestic transportation and energy supply infrastructure has meant that developmental projects not only concentrate around the capital but also reach other regions so that places for employment and wealth generation go beyond the cities. As can be seen in , this has brought certain positive outcomes as the major regions of Uzbekistan managed to attract the attention of Chinese investors.

Accordingly, Tashkent city (8 projects) and the Tashkent region (21 projects) remain the most attractive areas for investments but are now followed by Jizakh (8 projects), Samarkand (9 projects), Bukhara (8 projects), and others.

In addition to the projects above which are administered by each regional administration, there are a number of projects which are administered by the republican (central) government in Uzbekistan. These often relate to the areas which are under the jurisdiction of the central government, and focus on higher level matters such as mineral resources, processing, communications, and others ().

Table 7. Roadmaps by project areas.

These are the projects that are administered by public companies and institutions such as Uzbekneftegaz (2 projects), the Ministry of International Trade (3 projects), the Ministry of Technology Communication Development (3 projects), the State Committee of Geology and Mineral Resources (3 projects), the National Association of Construction Materials Production (4 projects), Angren Industrial Zone (7 projects), the Agency for Development of Pharmacy Sector (5 projects), and others (). The goals of these projects are to import equipment that enables the production of goods with added value from the mineral resources available in Uzbekistan and support the development of products that can replace materials currently imported from abroad.

The most exemplary case is the construction materials that were largely imported to Uzbekistan in the past but now are widely produced domestically from locally extracted raw materials. By encouraging these types of productions domestically, the Uzbek government hopes not only to satisfy the domestic need for such products but also to establish a hub for such production to export these products to the neighboring CA states, Russia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and others. In doing so, the Uzbek government is attempting to take advantage of the surplus labor force available in the country and its geographic position at the center of the region. In developing the textile industry, it hopes to attract Chinese projects into processing Uzbek raw cotton of which China has extensive experience (for details see ).

In addition to the developmental projects, there is a certain amount of credits and loans acquired by the Uzbek financial institutions to enhance their ability to provide financial services to businesses in Uzbekistan. For instance, Uzmilliy bank has acquired five financing projects for the amount of USD 1.5 billion followed by Turan bank acquiring four projects in the amount of USD 166.6 million and Uzsanoat bank (one project for USD 100 million). These sources are projected to be used for the projects financing projects in agriculture, car assembly and other industrial projects (; see for details).

Table 8. Some examples of the projects included in the roadmap of April 2022.

7. Public perceptions and Sino-Uzbek developmental agenda: policymakers and the youth perception of Uzbekistan’s international partners

The analysis of the factors of the pentagonal model provided above included domestic politics (bureaucracy as a stakeholder), the vision of “self” (developmental strategy), and economic projects along the line of goals set in the domestic developmental agenda and serve as safeguards against one-sided economic domination in cooperation schemes. Over the course of interviews with 13 governmental officials which included members of parliament, Cabinet of Ministers representatives, Research Institute personnel, and members of universities (). Although interviews were conducted with important stakeholders, most of them continue their active service in their positions. As such, they indicated their desire to have their interviews be anonymous as any positions they indicate may negatively impact the relations of Uzbekistan with China.

Table 9. Anonymized list of respondents to the interview survey conducted in February 2023 in Uzbekistan.

Due to the anonymity requested by the respondents, the findings below cannot be clearly attributed to individual respondents in the table above. However, they provide insights into the views of members of policy-making institutions with regard to China.

In terms of the views which unite the perspectives of all the respondents, there are the following three points. First, all respondents indicated their perception that China is both an Uzbek neighbor and an important economic partner. In the view of all respondents, there is no event/circumstance that can change this situation in the foreseeable future due to close geographic proximity and the economic might of China. The second point made during almost all the interviews is that there is a need to facilitate technology transfer from China to Uzbekistan which is the primary concern of all the governmental agencies in Uzbekistan. The third point made in all interviews is that Uzbekistan’s priority is to develop economic ties that do not necessarily need to extend into political or social spheres. In other words, Uzbekistan, both at the level of legislative and executive bodies is primarily interested in the economic and IT dimensions of relations with China with other sectors remaining of secondary importance.

Depending on the sphere of expertise, there were also diverse points expressed by different respondents reflecting the interests of the institutions they currently represent. For instance, the members of parliament who discussed the Chinese policy toward Uzbekistan emphasized that Uzbekistan needs to define its own national interests in approaching Chinese economic offers. The Uzbek government links its national interests to the development of the Central Asian region, and it is implementing such a policy in its relations with China. This implies that projects undertaken with China should not conflict with the national interests of other CA regional countries.

In the same manner, some of the respondents from think tanks informing foreign policy priorities indicated that the Uzbek government’s preference for cooperation in technology transfer should not spill over into increased Chinese social presence or influence in the country. For this reason, some respondents from the educational institutions suggested that there are no Chinese universities in Uzbekistan and that the Ministry of Higher Education does not particularly encourage inter-university agreements with Chinese liberal arts universities. In a similar manner, when the establishment of the third Confucius Institute was proposed, the idea did not receive any particular support from the government. Currently, the only Confucius Institutes in Uzbekistan are based at the premises of the University of Oriental Studies in Tashkent and the University of Foreign Studies in Samarkand.Footnote70 These numbers are relatively small when compared to the presence of such institutes in other former Soviet countries such as Russia (19), Kazakhstan (5), and Kyrgyzstan (4) or in other countries neighboring China, such as South Korea (23), Japan (15) or Mongolia (3).

In this sense, attracting direct investment is considered to be the priority while cooperation in the field of education is not. In addition, respondents from the educational institutions indicated that there are few proposals from national universities in China to establish cooperation with Uzbekistan. Rather, there are a greater number of proposals from private Chinese universities, which are received with caution on the Uzbek side as there is an understanding among Uzbek officials that for Chinese Universities this represents a business opportunity to attract more Uzbek students with little benefit for Uzbekistan. Even the International Tourism University established under the patronage of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Samarkand is an institution proposed and almost fully financed by the Uzbek government with few funds coming from China or the SCO. It rather positions itself as a fully-fledged International University with many if not all classes taught in foreign languages and having faculty recruited internationally.

It is noticeable that one of the Vice Presidents of this University is from China with his main field of responsibility defined as innovation and research and annual projects funded from the funds coming from various ministries in China interested in establishing laboratories in Uzbekistan/Central Asia or feasibility studies into the tourism sector in Uzbekistan. However, even such China-funded projects need to be coordinated with the Uzbek government and approved by it before they commence. In addition, the outcomes of the feasibility studies or the projects are also submitted in the form of a report to the Uzbek government, thus making sure that there is oversight over the funds and the projects.

In terms of the concerns expressed by various stakeholders in Uzbekistan, one is related to the understanding of the national interests of Uzbekistan that is shared by the Presidential office and the Cabinet of Ministers, and some parliamentarians. However, the degree of understanding of the national interests of Uzbekistan among all parliamentarians is not equal and those not well-versed in government policy might sometimes be tempted to attract Chinese presence in areas that are not necessarily beneficial from the perspective of the government.

Finally, most of the policymakers suggested that there are two effective ways to leverage Chinese influence in the cooperation agenda. One is to diversify international partners of Uzbekistan and to have two or more countries involved in each economic sector so that there is no dominance of or dependence on any particular country. The second way is to have a process of careful planning and drafting cooperation road maps as the instrument used to diversify projects with different international partners.

In addition to the views from policymakers, there is also the angle of public opinion as represented by the emotions and perceptions related to China as a cooperation partner of Uzbekistan, especially among the youth. The focus on the images of Uzbekistan’s main international partners is especially important as youngsters under 30 years old constitute more than half of the 35 million population of the country. It should be noted, however, that the polls discussed below were conducted prior to the Russian war in Ukraine and the consequent criticism of Russia. Therefore, while these Figures provide an important angle for considering the images of the US, EU, and China, the image perceptions toward Russia have potentially been influenced by recent events surrounding the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

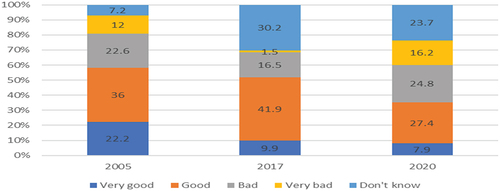

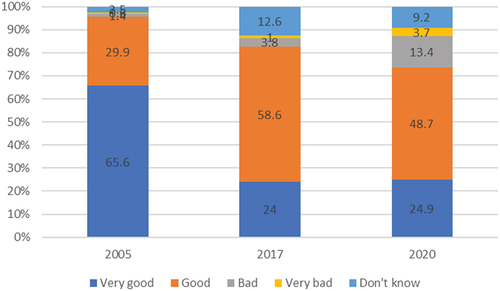

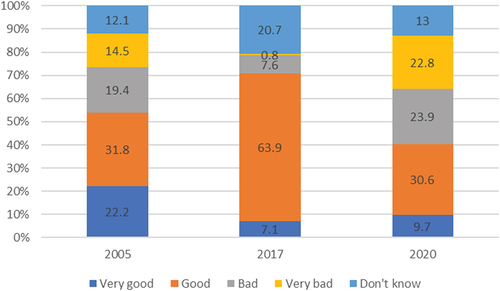

There are several databases from which data can be aggregated in order to place China among the other international partners of Uzbekistan. We use comparisons generated from the AsiaBrometer 2005 survey which covered the CA states including Uzbekistan and from the Central Asian Barometer based in Bishkek and operating since 2017. As depicted in the tables below, in order to focus on the youth’s voices we generated data from samples of answers from 30 year olds and under this age from the total number of respondents. The resulting three Figures demonstrate chronological changes in the images of the US, Russia, and China respectively ().Footnote71 The results show that there is a tendency toward the diversification of Uzbek youth’s views of these countries over time, influenced by factors such as their increasing knowledge about these countries, their personal experiences, and the changing international environment.

Figure 7. Uzbek youth’s views of the US: 2005–2020.

Figure 8. Uzbek youth’s views of Russia: 2005–2020.

Figure 9. Uzbek youth’s views of China: 2005–2020.

In regard to the images projected by the major international partners of Uzbekistan, the positive image of the US among youth has decreased over the three different surveys, while the image associated with a negative view shows signs of increasing. Interestingly, however, around one-fourth (24.8% for 2020) of the respondents chose the “Don’t Know” (DK) answer, indicating they have no image to associate them with the US (). In line with these answers, it can be hypothesized that the US’s idealized image largely predisposes the choice of this country in terms of values and lifestyles depicted in mass media and pop culture to which the youth are the most exposed. In addition, the US hosts one of the largest communities of migrants originating from Uzbekistan, which often serves as another motivation to explore the possibility of life in the US. A large number of DK answers can be related to the fact that although youth in general have a positive view of the US, the impact of US developmental projects on improving everyday lives in Uzbekistan is very limited. The US, when compared to Russia or China is not actively involved in the developmental agenda of Uzbekistan and this creates the “emptiness” of the image associated with it.

In terms of the image of Russia (), positive images (“very good” answers) registered between 2005 and 2020 in three different polls show clear signs of decrease, which in the post-Ukrainian war world can be expected to be even worse than these data. At the same time, the number of respondents who consider images of Russia to be generally positive (very good+good) answers demonstrate decreasing but steady support toward Russia among Uzbek youth. This is brought about by several factors. One is related to Russia being the leading economic partner for Uzbekistan in many areas as indicated in the data provided in section two of this paper. Another reason is related to the fact that Russia, as a the former metropole, serves as the place of residence for a large number of the Uzbek diaspora. It is also often considered by many as a possible place for relocation. The significant Uzbek diaspora in Russia, as well as being acquainted with the Russian language in many cases, serves as a pull factor for Uzbek migrants.Footnote72 Lack of employment opportunities and educational opportunities at home, administrative controls prevalent under the past Karimov administration, and the more widespread (compared to Russia) corruption serve as push factors for such individuals. As is the case with the US, the images of these countries are often linked to the roles they play in the everyday lives of people in Uzbekistan. In this sense, the role of Russia as an educational and employment hub and its media as a source of information for many serves as a factor in painting it in positive terms.

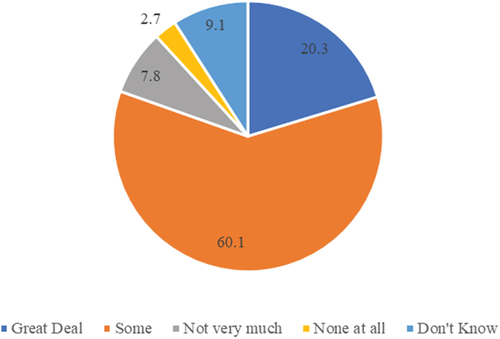

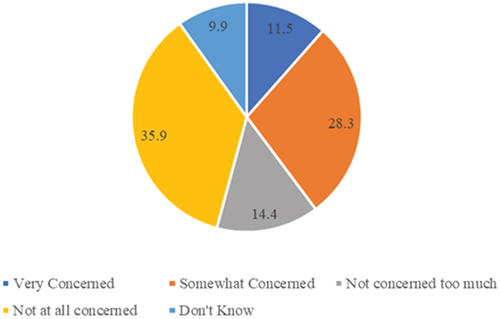

In terms of China (), the survey participants seem torn between the images of positivity and negativity associated with it. Although declining from 54.0% in 2005 to 47.7% in 2020, roughly half of the respondents consider China’s influence to be good for Uzbekistan. Paired with around one-third (30.6% in 2020) of those who evaluated Chinese influence as “good,” they represent a significant number of youth who appreciate Chinese influence in their country. The positivity associated with China is largely connected to opportunities and support, indicated as the second-choice attribute, and economic power as the third-choice image of China.Footnote73 In addition, one-tenth (10.1%) responded with “Don’t know” answers, indicating the transitionary image of China in Uzbekistan. This could mean that many of the younger generations are not yet certain about how to come to terms with China’s growing economic might and presence in their society, thus simultaneously projecting both positive and negative images. In fact, youth in Uzbekistan are aware of both positive and negative aspects of Chinese investment to Uzbekistan. All in all, Uzbekistan youth are confident in China’s investment (see ), but when it comes to its negative effect, roughly two-fifths of them have concerns with the increase of national debt with China (see ).

Figure 10. “How much confidence do you have that China’s investment in our country will improve energy and infrastructure in our country? (%).

Figure 11. “How concerned, if at all, are you that Chinese development projects could lead to an increase of national debt with China? (%).

There are several hypothetical narratives that can be made to fit the data above. Uzbekistan’s foreign policy behavior has been dominated by agendas that had little, if any, input from younger generations in the years prior to 2016 when dictatorial president Karimov passed away. The newly formed foreign policy under President Mirzyoeev opens some space for the public’s wider participation in formulating its goals, which have significant relevance to youth. Thus, there are two separate but connected aspects of Uzbekistan’s foreign policy agenda that relate to Uzbek youth.

The first is the tendency to open up Uzbekistan to the international community. This tendency championed and implemented by President Mirziyoyev received a warm welcome from youth for changing the image of Uzbekistan and because it opened more opportunities for developing their skills, establishing ties with foreign counterparts, and possibly expanding their activities beyond Uzbek boundaries. This is an important aspect for many youths in Uzbekistan who, for a long time, felt isolated from their counterparts in other parts of the world under the administration of the late President Islam Karimov. As indicated in this survey, many young people see such changes expanding their opportunities abroad, consequently improving their lives and positively impacting Uzbekistan.

The second aspect that can be observed is the changing perception of the international community and other countries through the prism of changing domestic politics and values in Uzbekistan. As is observed in the respondents’ answers, one can see that youth are far from dividing countries into «friendly» or «unfriendly» in political terms. They tend to attribute meanings to these terms from the perspectives of these states’ contribution to the well-being and career of themselves. In this sense, the evaluations of relations with various countries based on practical and functional benefits used by the new foreign policy of President Mirziyoyev are well received and, to a great extent, reflect the views and perceptions of the younger generations.

In terms of the tasks and future agenda that youth consider to be important in foreign policy, the responses in the current survey indicate that evaluation and imagining of various countries in young respondents’ minds are closely connected to how these relations are conceptualized in practical terms. In contrast to youth in developing countries, who tend to perceive the world and patterns of interactions with foreign countries through an idealist-driven perspective of the common good and benefit, youth in Uzbekistan tend to be conscious of its benefits and particular relationships with respect to their own individual interests. When youth can hardly imagine the practicality or use of a particular part of their life, they tend to undervalue its importance. In this sense, the foreign policy agenda of youth and the international community’s image for many of them are closely related to how these connections impact youths’ everyday lives. Thus, this is one of the criteria they use in evaluating the efficiency and the benefit of relations with foreign counterparts. In addition, when respondents are requested to evaluate relations with a particular country not directly linked to their needs, they tend to produce conflicting images of both positivity and negativity, as exemplified by China, providing little clue as to how to understand these answers.

8. Conclusions

This paper outlined the patterns of interactions between Central Asian states and China, exemplified by Uzbekistan and China, using the process of drafting and implementing cooperative road maps as a case study. There are a few factors that need to be extracted as facilitating cooperation between Uzbekistan and China over the last years. First, against the backdrop of previous studies which suggest that China dominates cooperation agenda setting in its relations with smaller counterparts, this paper demonstrates that there is no empirical evidence to suggest the structure of relations between China and Uzbekistan victimizes Uzbekistan or offers a competitive advantage to China. On the contrary, given the similarity of economic governance structures, the practice of drafting cooperation roadmaps offers Uzbekistan the opportunity to effectively manage its bargaining power and facilitate equal bargaining opportunities to the private market participants which otherwise could have been dominated by their larger Chinese counterparts, if they were to negotiate with them on their own. In addition, these roadmaps are a result of the pattern of interactions between these states and as such, are a product of their social interaction from the time of the first inception of roadmaps in 2017 to the present. There is a great deal of maturing of these roadmaps from 2017 to 2022 as they have been subject not only to the interaction between these two states but also the international environment, the COVID-19 pandemic, public opinion, and regional development as exemplified by the project on the construction of transport infrastructure from China to Uzbekistan through Kyrgyzstan.

Second, a functioning bureaucracy capable of drafting and presenting a national strategy to Chinese partners is essential to properly conveying the interests of developing countries represented by Uzbekistan in this paper. Although there are many instances of corruption and malfunctioning of bureaucracy in Uzbekistan, the case of Sino-Uzbek economic cooperation demonstrates that the bureaucracy has been instrumental in providing and protecting the narrative of Uzbek national interests in relation to Chinese public and private enterprises.

Third, in contrast to the previous literature on relations between energy-resource-rich CA countries and China that claims that the Chinese government and its corporations effectively exploit CA states’ mineral resources, this study suggests that Uzbekistan actually exploits Chinese interest in the energy resources for the purpose of diversifying its industrial base and establishing production cycles to process these resources into value-added products.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timur Dadabaev

Dr. Timur Dadabaev is a Professor of International Relations and the Director of the Special Program for Japanese and Eurasian Studies at the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Tsukuba, Japan. He published extensively with Communist and Post-Communist Studies, The Pacific Review, Europe Asia Studies, Nationalities Papers, Journal of Contemporary China, Asian Survey, Asia Europe Journal, International Journal of Asian Studies, Inner Asia, Central Asian Survey, Asian Affairs, Strategic Analysis, Journal of Eurasian Studies, Japanese Journal of Political Science, Cambridge Journal of Eurasian Studies and others. His latest monographic books are Decolonizing Central Asian International Relations: Beyond Empires (Oxon: Routledge, 2021), Transcontinental Silk Road Strategies: Comparing China, Japan and Korea in Uzbekistan (Oxon: Routledge, 2019), Chinese, Japanese and Korean In-roads into Central Asia (Policy Studies Series, Honolulu: East-West Center 2019), Japan in Central Asia: Strategies, Initiatives, and Neighboring Powers (NY: Palgrave Macmillan 2016) and Identity and Memory in Post-Soviet Central Asia (Oxon: Routledge, 2015). His edited volumes include The Grass is Always Greener? Unpacking Uzbek Migration to Japan (NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan: Life and Politics during the Soviet Era, (Co-edited with Hisao Komatsu), NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017 and Social Capital Construction and Governance in Central Asia: Communities and NGOs in post-Soviet Uzbekistan (Co-edited with Yutaka Tsujinaka), NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Shigeto Sonoda

Prof. Shigeto Sonoda is Professor of comparative sociology and Asian studies at the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia (IASA), the University of Tokyo. He has been serving as director of Beijing Center for Japanese Studies at Beijing Foreign Studies University in China as well as program advisor of Collaborative Research Workshop for Young Aspiring Scholars in Japanese Studies hosted by the Japan Foundation since 2018. His major publications include Asiabound of Japanese Company (Yuhikaku, 2001) and National Sentiments in Asia (Chuo Koron, 2020) as well as edited books including China Impact (with David S. G. Goodman, University of Tokyo Press, 2018) and Global Views of China (with Yu Xie, University of Tokyo Press, 2021).

Notes

1 Fabienne and Kaczmarski, “Russia and China between Cooperation and Competition at the Regional and Global Level,” 539–556; Soboleva and Krivokhizh, “Chinese Initiatives in Central Asia: Claim for Regional Leadership?,” 634–658; Leskina and Sabzalieva, “Constructing a Eurasian Higher Education Region: ‘Points of Correspondence’ between Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia,” 716–744.

2 Pizzolo and Carteny, “The ‘New Great Game’ in Central Asia: From a Sino-Russian Axis of Convenience to Chinese Primacy?” 85–102; Freeman, “New Strategies for an Old Rivalry? China – Russia Relations in Central Asia after the Energy Boom,” 635–654

3 Dadabaev, “Chinese and Japanese Foreign Policies toward Central Asia from a Comparative Perspective,” 123–145; Dadabaev, “Discourses of Rivalry or Rivalry of Discourses: Discursive Strategies of China and Japan in Central Asia” 61–96; Porshneva et.al, From Interaction to Integration? Exploring New Horizons, 9–24.

4 National Development and Reform Commission, “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”

5 Tang and Joldybayeva, “Pipelines and Power Lines: China, Infrastructure and the Geopolitical (Re)construction of Central Asia”

6 Macikenaite, “China’s Economic Statecraft: The Use of Economic Power in an Interdependent World,” 108–26.

7 Aryal, “Central Asia Region in China’s Foreign Policy after 2013: A Geoeconomics Study,” 743–753.

8 Hobson and Zhang, “The Return of the Chinese Tribute System? Re-viewing the Belt and Road Initiative”

9 Uyama, “Sino-Russian Coordination in Central Asia and Implications for U.S. and Japanese Policies Asia Policy,”26–31; Zhang, China’s Emergence and Development Challenges that China Faces in Central Asia; Jiang, “Central Asian Elites Choose China over Russia.”

10 Kazantsev et al. “Between Russia and China: Central Asia in Greater Eurasia”

11 Zhou, He, and Yang, “Energy geopolitics in Central Asia: China’s involvement and responses;” Sachdeva,“Indian Perceptions of the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative,”

285–296.

12 Voloshin,“Central Asia Ready to Follow China’s Lead Despite Russian Ties”

13 Bitabarova, “Unpacking Sino-Central Asian Engagement along the New Silk Road: A Case Study of Kazakhstan,”149–173.

14 Ibid.; Tjia, “Kazakhstan’s Leverage and Economic Diversification amid Chinese Connectivity Dreams,” 797–822.

15 Takahara,“Introduction to the Special Issue on the Comparative Study of Asian Countries’ Bilateral Relations with China,”157–161.

16 e.g., descriptions of IR developments by Acharya and Buzan, The Making of Global International Relations: Origins and Evolution of IR at its Centenary,187–192; Freeman, “New Strategies for an Old Rivalry? China – Russia Relations in Central Asia after the Energy Boom,”635–654; Kirkham “The Formation of the Eurasian Economic Union: How Successful is the Russian Regional Hegemony?” 111–128.

17 Dugin, Geopolitika Post-Moderna: Vremena Novyh Imperii. Ocherki Geopolitiki 21 Veka (Geopolitics of Post-Modern: The Times of New Empires. Essays on Geopolitics of 21st Century).

18 Zhang, “China’s Emergence and Development Challenges that China Faces in Central Asia;” Alimov “The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Its Role and Place in the Development of Eurasia,” 114–124; Obydenkova, “Comparative Regionalism: Eurasian Cooperation and European Integration. The Case for Neofunctionalism?” 87–102.

19 Zhang, “China’s Emergence and Development Challenges that China Faces in Central Asia;” Li, “The Greater Eurasian Partnership and the Belt and Road Initiative: Can the Two be Linked?” 94–99.

20 Li, “China’s Energy Diplomacy toward Central Asia and the Implications of its “Belt and Road Initiative,” 1–33; Chen and Fazilov, “Re-centering Central Asia: China’s ‘New Great Game’ in the Old Eurasian Heartland,” 71.

21 Zhang, “China’s Emergence and Development Challenges that China Faces in Central Asia;” Pizzolo and Carteny,“The ‘New Great Game’ in Central Asia: From a Sino-Russian Axis of Convenience to Chinese Primacy?” 85–102; Zhou, He, and Yang, “Energy Geopolitics in Central Asia: China’s Involvement and Responses,” 1871–1895; “New Strategies for an Old rivalry? China – Russia Relations in Central Asia after the Energy Boom,”635–654.

22 Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva, “Between the Bear and the Dragon: Multivectorism in Kazakhstan as a Model Strategy for Secondary Powers”

23 Haacke, “The Concept of Hedging and its Application to Southeast Asia: A Critique and a Proposal for a Modified Conceptual and Methodological Framework,” 375–417.

24 Kuik, “How Do Weaker States Hedge? Unpacking ASEAN states’ Alignment Behavior toward China,” 3.

25 Ibid.

26 Li-Chen and Aminjonov,“Statecraft in the Steppes: Central Asia’s Relations with China”

27 Ibid:3–5.

28 Kuik, “How Do Weaker States Hedge? Unpacking ASEAN States’ Alignment Behavior toward China,” 3.

29 For details see Dadabaev, Transcontinental Silk Road Strategies: Comparing China, Japan, and South Korea in Uzbekistan; Dadabaev, Chinese, Japanese and Korean In-roads into Central Asia: Comparative Analysis of the Economic Cooperation Road Maps for Uzbekistan; Dadabaev “De-securitizing the Silk Road: Uzbekistan’s Cooperation Agenda with Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea in the Post-Karimov era.” 174–187.

30 For criticism of this view see Cooley, Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia; Heathershaw, Owen, and Cooley, “Centered Discourse, Decentred Practice: The Relational Production of Russian and Chinese ‘Rising’ Power in Central Asia,”1440–1458.

31 Tjia, Kazakhstan’s Leverage and Economic Diversification amid Chinese Connectivity Dreams, 797–822.

32 ibid. Also see Dyssikov, “Kazakhstan’s Investment Strategy toward China, Korea, and Japan: Place and Role of Foreign Investments (2010–2019),” Bitabarova, “Unpacking Sino-Central Asian engagement along the New Silk Road: A Case Study of Kazakhstan,” 164–169, 808.

33 Dyssikov, “Kazakhstan’s Investment Strategy toward China, Korea, and Japan: Place and Role of Foreign Investments (2010–2019).”

34 Bitabarova, “Unpacking Sino-Central Asian Engagement along the New Silk Road: a Case study of Kazakhstan,”149–173; Tjia, Kazakhstan’s Leverage and Economic Diversification amid Chinese Connectivity Dreams, 797–822.

35 Bitabarova, “Unpacking Sino-Central Asian Engagement along the New Silk Road: A Case Study of Kazakhstan,”162–163.

36 Dadabaev, Transcontinental Silk Road Strategies: Comparing China, Japan, and South Korea in Uzbekistan; Dadabaev, Chinese, Japanese and Korean In-roads into Central Asia: Comparative Analysis of the Economic Cooperation Road Maps for Uzbekistan; Dadabaev “De-securitizing the Silk Road: Uzbekistan’s Cooperation Agenda with Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea in the Post-Karimov Era,” 174–187.

37 For this approach see Dadabaev,“Chinese and Japanese Foreign Policies toward Central Asia from a Comparative Perspective,”123–145; Decolonizing Central Asian International Relations: Beyond Empires; “Nationhood through Neighborhood? From State Sovereignty to Regional Belonging in Central Asia.”

38 see Fitriani, “Linking the Impacts of Perception, Domestic Politics, Economic Engagements, and the International Environment on Bilateral Relations between Indonesia and China in the Onset of the 21st Century,” 183–202; Lam 2021; Hwang, “The Continuous but Rocky Developments of Sino-South Korean Relations: Examined by the Four Factor Model,” 218–229; Sonoda, “Asian Views of China in the Age of China’s Rise: Interpreting the Results of Pew Survey and Asian Student Survey in Chronological and Comparative Perspectives, 2002–2019,” 262–279.

39 Takahara, “Introduction to the Special Issue on the Comparative Study of Asian Countries’ Bilateral Relations with China,”157–161.

40 Ibid.

41 Dadabaev “De-securitizing the ‘Silk Road:’ Uzbekistan’s Cooperation Agenda with Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea in the Post-Karimov Era,” 174–187.

42 Kim and Blank, “Same Bed, Different Dreams” and Sullivan, “Uzbekistan and the United States.”

43 Dadabaev, “De-Securitizing the Silk Road.”

44 Fazendeiro, “Uzbekistan’s ‘Spirit’ of Self-Reliance and the Logic of Appropriateness: TAPOich and Interaction with Russia,”484–498; “Uzbekistan’s Defensive Self-reliance: Karimov’s Foreign Policy Legacy,”409–427. Dadabaev “De-securitizing the ‘Silk Road:’ Uzbekistan’s Cooperation Agenda with Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea in the Post-Karimov era,”174–187.