ABSTRACT

Focusing on Laos’s engagement with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), this article examines the role and limits of host-county agency toward foreign-backed infrastructure connectivity cooperation. Based on fieldwork observations, semi-structured interviews, and scholarly literature, this paper finds that Laos’s agency toward the BRI has been mixed and uneven, with both active and passive elements. That is, while Laos actively initiated cooperation with China on the Vientiane-Boten railway and other projects, during the negotiation and implementation phases it was at times passive and acquiescent. While the Lao government has attempted to shape the processes, it is unclear how successful these attempts have been. Although the Lao authorities have pursued pragmatic planning in order to benefit more fully from ventures with China, it is too early to determine actual progress. We argue that such patterns of agency result from internal and external dynamics. Internally, while Lao elites’ performance legitimation has been the main driver motivating the small state’s embrace of the BRI, its capacity to gather feedback, act responsively, and correct its course of cooperation has been limited by its one-party political system and near absence of societal agency. Externally, a lack of alternative infrastructure partner has further constrained Laos’s developmental options. Looking ahead, external partners have an important role to play.

1. Introduction: Laos-China connectivity cooperation in the regional context

Of all the Southeast Asian countries, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR) has been one of the most enthusiastic in engaging with and embracing China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The landmark Vientiane-Boten Railway, a 422-kilometer standard-gauge electrified rail connecting Vientiane, the capital city of Laos, with the northern border town of Boten, was inaugurated on 3 December 2021. Other BRI-related projects in the landlocked country include special economic zones, highways, hydropower, mining, and agricultural projects.

This essay aims to examine the extent and limits of small-state agency vis-à-vis foreign-backed infrastructure connectivity cooperation by focusing on Laos’s host-country agency (or the lack thereof) toward China’s BRI ventures. The reasons for studying infrastructure cooperation between Laos and China are threefold. First, the Vientiane-Boten railway was the first completed rail project built and funded by China in Southeast Asia. Additionally, the railway further links Boten to the southern Chinese city of Kunming, making it the only standard-gauge railway that connects Southeast Asia directly to China’s vast high-speed rail (HSR) network. Hence, the Laos-China Railway (LCR) is a bilateral Laos-China project with wider implications for Southeast Asia-China relations.

Second, given Laos’s geographical location between China and mainland Southeast Asia, the Vientiane-Boten railway is an important part of the regional connectivity network, with transformative potential for trans-boundary connectivity cooperation in mainland Asia. With the railway now up and running, Lao authorities are building capacity and connections with an eye to making Laos a gateway for regional transport and trade cooperation. From Vientiane’s Thanaleng Station, the railway will eventually connect Laos with Thailand’s Nong Khai, the northernmost terminus of the planned Bangkok-Nong Khai HSR (also known as the Thailand-China HSR, given China’s role as the builder of the 608-kilometer standard-gauge rail line). Since the opening of the Vientiane-Boten railway in December 2021, Thai and Lao authorities have discussed expanding transport, trade, and people-to-people connectivity across the Thailand-Laos border. In addition, the Thai and Malaysian leaders have discussed constructing the Bangkok-Kuala Lumpur HSR (even though the long-planned Kuala Lumpur-Singapore HSR project has been canceled, reinstated and again suspended by successive Malaysian governments following the country’s first regime change in 2018). Thus, the operational Vientiane-Boten rail project is more than Laos and more than simply a railway. While it is too early to determine whether the railway will be a catalyst for closer regional connectivity, it is clear the opening of the railway and subsequent cross-border policy talks mark a new phase in regional connectivity building within Southeast Asia and wider mainland Asia. These processes will shape China’s relations with its Asian neighbors.Footnote1

Third, Laos represents a “least likely case” for examining host-country agency. As one of the least developed nations in Asia and possessing limited strengths, Laos is widely perceived as a weak state with weak agency in dealing with external powers and related affairs, including foreign-backed development ventures. Thus, Laos’s dealings with China on big-ticket infrastructure projects offer a pertinent case to unpack the phenomenon, promises, and limits of small-state agency. Before and during the construction of the Vientiane-Boten railway, observers and pundits described the project as a “China push” and a “white elephant”, “debt-trap” venture. Against this backdrop, the completion of the project provides a timely opportunity to examine the progress, problems, and prospect of Laos’s host-country agency.

Methodologically, this paper relies primarily on field research (including interviews with Laos’s elites, informal conversations, and participant observations) to gather high-level and expert assessments of the project as well as gauge user experience and on-the-street feedback about Chinese projects in Laos. Particular attention was paid to the Vientiane-Boten railway because of its central salience to the research questions and focus. Fieldwork was conducted in September 2022, in Vientiane and other major urban centers and towns (i.e. Vang Vieng, Luang Prabang, Muang Xai, Luang Namtha, and Boten) along the rail line. In the capital and the northern towns, dozens of semi-structured interviews were carried out with Lao politicians, government officials at different levels and sectors, academics, policy researchers, and foreign experts based in Laos. Informal conversations with members of the public, private firms, business people, train users, and train attendants took place with the assistance of an interpreter in Vientiane and other selected towns.

The research reached the following findings. Laos’s host-country agency vis-à-vis the BRI is mixed and uneven, with signs of being both vigorous and acquiescent. Laos has demonstrated agency in setting the direction (e.g. proposing numerous infrastructure and development projects) and pushing the envelope (e.g. seeking to maximize cooperation with minimal resources) vis-à-vis its much more powerful partner, China. Once the projects took off, however, the ability of the Lao government to shape and alter things on the ground varied across policy areas. Specifically, while Laos played an active role in initiating proposals and institutionalizing cooperation with China on a variety of infrastructure connectivity projects (most notably the Vientiane-Boten railway, but also other projects), it has not shown an ability to renegotiate, let alone resist, the unsatisfactory aspects of the Chinese ventures. While there were some signs of Laos exerting its agency (e.g. bargaining and pushing back China’s terms), it is unclear whether such attempts were successful as there is no publicly available evidence on whether efforts to renegotiate were attempted, the extent to which China accommodated Laos’s requests, and whether Laos has secured the outcome it desired. Although the Laos elites engaged in some self-assessment and practical planning, it is still unclear how much progress has been made.

The remainder of this essay proceeds in five sections. Part 1 presents the conceptual and theoretical framework. It offers a definition of “host-country agency,” before identifying the key factors accounting for the varying degrees and forms of small-state agency in connectivity cooperation. Part 2, which is based on fieldwork, describes Laos’s engagement with China on the railway and other projects. Part 3 identifies and assesses the patterns of Laos’s host-country agency. Part 4 explains why Laos’s agency has remained mixed and uneven. Part 5 concludes by highlighting the theoretical and policy implications of the findings.

2. Framework: defining and explaining “host-country agency”

Agency is viewed as an intermediary between macro-structures and micro-processes.Footnote2 When applied to international relations, macro-structures refer to such structural, top-down conditions as asymmetrical power relations, power rivalries, and systemic uncertainties, while micro-processes refer to the unit-level interactions along the key stages of inter-state cooperation, i.e. initiation, negotiation, and implementation. Accordingly, “host-country agency” is defined as the inclination, insistence, and capacity of a sovereign host to make autonomous and independent decisions, shape circumstances, and pursue its desired outcomes during the initiation, negotiation, and implementation of a foreign-backed venture, despite the conditions of power asymmetry and uncertainty. Agency does not mean that a state can always get what it wants. However, agency does mean that a smaller and weaker state, despite its disadvantageous position, is often determined to cultivate options and optimize policy goals as much as circumstances allow.

Host-country agency in infrastructure cooperation manifests in multiple forms. These include: (a) proactive initiation (proposing an infrastructure connectivity partnership to a foreign power); (b) active involvement (enthusiastically participating in and partnering with an external power on an infrastructure construction venture); (c) active renegotiation (advocating for amendments to the previously agreed-upon terms of an infrastructure partnership); and/or (d) passive resistance (denying, delaying, or distancing from a stronger power’s initiative).

These typologies are not mutually exclusive. Often, a host country exhibits most if not all of these patterns across different times, projects, and/or key aspects of the cooperation.Footnote3 For instance, in the case of Laos, the small state has displayed a mixed, uneven, and still evolving pattern of agency across the four parameters, as discussed below.

The term “host-country agency” does not imply that any of the countries hosting a foreign-backed project is a unitary or homogeneous actor. Indeed, in many countries, primarily those with pluralistic political systems with dynamic bottom-up, civil society movements and organizations at the societal level, host-country agency usually manifests in various forms of “state-level agency” and “societal-level agency” (or “subnational agency”). The interplay between state-level agency and societal agency is one of the key factors determining the progress and prospects of foreign-backed connectivity cooperation in different countries. Florian Schneider, for example, notes that many outcomes depend on the agency of host country: “the BRI is shaped by diverse local actors who exercise their agency for their own developmental ends or other goals.”Footnote4 The word “local” refers not just to provincial actors, but all host-country-based actors within and outside the government structure, across levels, sectors, and domains.Footnote5

Why then are some host countries more active and receptive than others when embracing connectivity partnerships with foreign powers? Building upon the pentagonal model elaborated in the introductory essay of this Special Issue – which highlights the interplay between domestic politics, the economy, peace and security, regional relations, and global dynamics – we hypothesize that the three clusters of factors that are the most important explanatory variables are: (a) the legitimation of elites; (b) internal resilience; and (c) external alternatives. While legitimation and resilience capture the combined effects of domestic politics, economy, and security, the presence/absence of external alternatives reflects the nature and extent of power dynamics in inter-state relations at the regional and global levels.

2.1. Driver: elites’ legitimation pathways

The primary driver in all connectivity cooperation is the ruling elites’ legitimation pathways. This variable intersects with such internal factors as political patronage and special interests, leading to different degrees and patterns of host-country receptivity. This framework focuses on the governing elites or political classes, that is, the small group of actors who exercise disproportionate power and influence over a particular society and country on the basis of governance authority, coercive capacity, or ideology.Footnote6 Regardless of their countries’ political systems, elites claim their “right” to rule by appealing to certain ideals, constructing substantial or substantiated narratives, and resorting to corresponding pathways. They do this in order to justify, enhance, and consolidate their domestic authority vis-à-vis other contesting elites and society at large. The three major ideals or legitimation pathways are: (a) procedural virtues (e.g. democratic values or social justice); (b) particularistic narratives (all forms of identity politics, including nationalist sentiment, ethnic and religious appeals, and personal charisma); and (c) performance-related rationales (e.g. ensuring growth and delivering development benefits, or managing nation-wide problems well, for instance maintaining internal order or quelling a pandemic). No elite relies on a single pathway to rule. In practice, all elites resort to a combination of legitimation pathways – with different degrees of emphasis and mobilization – for their inner justification.Footnote7

The prioritization of elite legitimation pathways matters because it motivates and limits the extent of host government engagement with foreign-backed projects and shapes the direction of state policies. In many countries, especially but not exclusively countries with questionable governance practices, patronage politics and elite co-option often intersect with and are covered by performance legitimation.

All things being equal, a host country is more likely to embrace foreign-backed development initiatives when close cooperation with the external power serves to boost the ruling elites’ growth-based performance and bolster other pathways of inner justification, e.g. managing internal conflict, neutralizing external pressure, and promoting national identity. The host-country is likely to be more receptive if the converging pathways of legitimation are also accompanied by opportunities for patronage and state-capital congruence (among elites and their transnational allies).Footnote8 However, where collaboration on a BRI project is expected to have a mixed impact on elite legitimation efforts, for example where performance justification is enhanced but identity-based particularistic legitimation is harmed, electoral support eroded, and/or national identity undermined, a host state is likely to be selective and cautious.Footnote9 Finally, a smaller state will tend to keep its distance from a foreign-backed project when close cooperation is expected to hurt the main basis for elite authority and legitimacy (e.g. nationalism, electoral pledges, or a reformist agenda), and when the perceived developmental benefits would be gained at the expense of security and territorial interests, autonomy, and/or sustainable development.Footnote10

In addition to elite legitimation, the relative degrees and manifestations of host-country agency in infrastructure cooperation, are influenced by other internal and external factors. Chief among these are the host country’s internal resilience and external alternatives, elaborated below.

2.2. Determinants: external alternatives and internal resilience

While elite legitimation and patronage politics explain the varying degrees of host-country receptivity, they do not explain why different countries show different patterns of agency in infrastructure cooperation. The latter is determined chiefly by the availability of alternative external partnership(s), as well as the host country’s degree of internal resilience.

Some scholars have used the term “hedging” or “economic hedging” to describe host-country agency in connectivity cooperation.Footnote11 Economic hedging refers to an active use of economic cooperation and developmental links as a means to leverage competitive power dynamics to pursue the policy ends of maximizing national interests, chiefly through the concurrent pursuits of active non-partiality, inclusive diversification, and prudent fallback cultivation.Footnote12 While virtually all sovereign actors are inclined to hedge under conditions of high-stakes and high-uncertainties, not all states possess the ability to turn this inclination into an ability to pursue an active, inclusive and prudent diversification, with an eye to offset risks and cultivate fallback options.

The extent to which a host country, especially a small and developing one, can bargain and hedge vis-à-vis an asymmetric partnership is determined primarily by the availability of alternative external partnerships. A host country can only pursue economic hedging when two or more powers vying for influence are courting it. As discussed in various chapters in Schindler and DiCarlo,Footnote13 the governments of Indonesia, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Nepal, and Ethiopia have been able to hedge and exercise agency primarily because competing powers (such as China, the United States, Japan, European countries, India) provided alternative partnership opportunities; this in turn, increases the leverage of smaller states when bargaining with any single power (e.g. China) to maximize their benefits from the foreign-backed connectivity cooperation (e.g. BRI-related projects). Conversely, when there is little alternative (e.g. when China is the principal source of infrastructure capital and technology), there is relatively limited room for smaller states to bargain for better deals.

However, in and of themselves, alternative partnerships only provide external space and resources for small-state hedging; they do not automatically translate into host-country agency. A more fundamental determinant of host country agency and the extent to which it can actively promote its interests in a partnership, is its internal resilience. Resilience – the ability to manage, withstand, and respond to certain challenges – involves multiple internal attributes and mechanisms for ensuring the survival, stability, and societal cohesion of a given country.Footnote14 Internal resilience matters the most because it determines the capability of host countries to pursue desired outcomes (including pushing back when necessary), while offsetting and mitigating risks surrounding power asymmetries and uncertainties.

Varying patterns of internal resilience are the result of internal attributes, most notably the degree and pattern of power pluralization: i.e. the extent and manner in which political power is distributed across the state and the society. Power pluralization, in turn, is a product of political systems, inter-elite relations, bureaucratic dynamics, and bottom-up activism.Footnote15 These themes play out across countries and time. Cambodia, Laos, and Malaysia are three enthusiastic embracers of China’s BRI in Southeast Asia, which have actively partnered with China on infrastructure cooperation. Each country, however, has demonstrated different patterns of host-country agency. The variations are attributable to different political systems and different patterns of power pluralization: Malaysia is a quasi- or semi-democracy, Cambodia a hegemonic authoritarian regime, and Laos, a Marxist-Leninist “party-state (phak-lat).” In all three countries, the leadership and inter-elite dynamics have intersected, shaping the extent and manner in which societal and bottom-up sentiments vis-à-vis Chinese projects are addressed. Different political systems and power pluralization, however, dictate different patterns of processes and outcomes.Footnote16

All in all, a host-country’s capacity to exert its agency and hedge against risks amid power asymmetries and uncertainties is determined by a combination of both internal and external factors. The greater a host country’s internal resilience and external alternatives, the greater its agency and ability to hedge.

3. Railway and Laos’s BRI engagement: elite and public perspectives

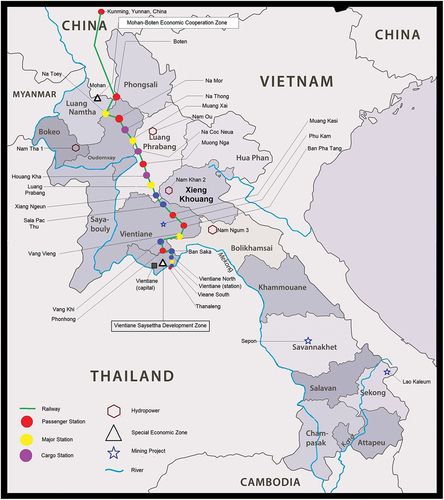

The Vientiane-Boten Railway is the signature project of Laos-China connectivity cooperation. At a cost of US$7 billion, the railway project is the most expensive mega project in Laos and is one of the signature BRI ventures in Southeast Asia. In addition to the railway project, Laos has also partnered with China on special economic zones, highways, hydropower, mining, and agricultural projects (see ). below shows the locations of the railway and selected BRI-related projects in Laos. The Lao government views the BRI as being in line with its own strategy to transform Laos from a landlocked country to one of Asia’s land-linked hubs.

Footnote17Table 1. List of BRI-related projects in Laos.

Based on observations from the first author’s interviews and fieldwork, this section reports on the assessments of the Lao elites and Lao public opinion toward the railway and other ventures. Additionally, the section covers the wider phenomenon of China’s growing presence in Laos, focusing on the impact of the railway on Laos’s economy and society.

3.1. Elite assessments

The Lao elites’ assessments of the Vientiane-Boten Railway have been largely upbeat and sanguine, with comments focusing primarily on economic impact. Such positive assessments, of course, do not necessarily mean that the Lao elites view the project as a “railway of dreams”. There are concerns about various aspects of the project (discussed below). Most assessments, however, highlighted such developmental benefits as transport, tourism, and trade and investment gains, as follows.

3.1.1. Transport

The transport benefits were highlighted by virtually all of the respondents the first author talked to in Vientiane and the northern provinces. Interviewees described the Vientiane-Boten Railway as the “backbone” of Laos’s gradually expanding transport connectivity and logistics system. The 422 km long railway not only connects the many cities and towns between Laos’s capital and the northern border town of Boten, it also links roads, other transport modes (e.g. airports) and logistics centers, including dry ports, cargo yards, and freight transit yards. With the train moving at a speed of up to 160 km per hour, the time and cost of transporting goods and means of production have been reduced, while capacity and efficiency have increased.Footnote18 The travel time between Vientiane and Kunming, the capital of China’s southwest Yunnan Province, is 30 hours by road but 10 hours by train. By December 2022, a year after the railway opened, the railway had carried 1.2 million passengers and nearly 2 million tons of goods, including moving more than 1.576 million tons of goods across the border.Footnote19

These transportation-related benefits are notable development dividends. Prior to December 2021, Laos only had a 3.5 km railway track linking Thanaleng Station with Thailand’s Nong Khai via the 1.2 km Friendship Bridge over the Mekong River.Footnote20 Hence, even before the construction of the Vientiane-Boten Railway was completed in 2021, it was viewed by many of Laos’s elites as a “river of iron,” designed to transform the landlocked country into a “land-linked” nation by connecting Laos to China and the more developed parts of Southeast Asia.Footnote21 Such a vision will take time to materialize, in part because Lao and Thai authorities are still in discussions to build a new railway bridge across the Mekong River to connect the Lao-China and Thai-China railways.Footnote22 However, within Laos, the railway is fast becoming one of the primary options for both passenger and freight transport in the mountainous country. With the opening of railway, transport connectivity has improved and transport costs have been reduced. These are likely to lead to several additional developmental benefits such as the integration of infrastructure, stimulation of sectoral development, and potentially the creation of cross-border competitive production clusters as new engines of growth. Over time, these may help bridge the urban-rural gap and the divide between the northern, central, and southern regions.

Nevertheless, despite the actual and potential benefits, some Lao elites also see challenges and risks posed by the Vientiane-Boten Railway. Logistics costs in Laos are still relatively high compared to neighboring Thailand and Vietnam.Footnote23 The possibility that Laos may become a mere “transit” point rather than a primary “gateway” of regional growth corridors linking southern China with Southeast Asian economies, was pointed out by a number of interviewees. A member of the Lao elite stated:

If Laos fails to make use of the current window of opportunity [of having the fast train connecting directly with China before neighboring countries complete their respective HSR links] in the coming years to make our domestic capacity competitive enough to attract foreign investors to build production plants and development stakes in Laos, we will face the risk of seeing potential investors and businesses using the railway as a passage to other neighboring economies, rather than coming to Laos with money and technology to make Laos a hub for logistics, manufacturing, services, and regional trade.Footnote24

3.1.2. Tourism

The tourism sector has significantly benefitted from the full operation of the Vientiane-Boten Railway. Since May 2022, when Laos reopened to foreigners post-COVID, tourist arrivals to such major tourist destinations as the Luang Prabang World Heritage Site and scenic Vang Vieng have increased significantly. The owners of hotels, restaurants, and travel agencies I talked to in Luang Prabang stated that “business [has gone] up a lot” compared to before COVID-19, with 60–70% local and the rest foreign tourists. At the main railway stations, foreign visitors are plentiful with an influx of tourists mostly from Thailand but also from Vietnam and Western countries. Thai tourists are not only from the neighboring Isan (northeast) region and Chiang Mai but also from Bangkok and elsewhere. Chinese travelers, including many Chinese nationals working in the northern region or returning to China after COVID, are now more visible at the main train stations in northern Laos (for example, Luang Namtha and Boten). Once the Chinese border reopens, hotel and restaurant operators anticipate a sizable inflow of Chinese tourists.

3.1.3. Trade and investment

Development benefits from the Vientiane-Boten Railway are seen by the Lao political leadership as mutually reinforcing. In July 2022, Laos’s Deputy Prime Minister Sonexay Siphandone stated: “I believed that the railway would create more business opportunities and bring great benefit to Laos.” He then added that the railway has “significantly reduced the time and logistics costs for cargo transportation” and that the railway will help boost “the growth of many industries like trade and investment.”Footnote25 The opening of the railway has boosted two-way cross-border trade between Laos and China, which has particularly benefited northern areas along the railway route, such as Muang Xay and Boten. below shows the total value of import and export trade between the two countries from 2018–2021.

Table 2. Laos-China trade, 2018–2021 (US$ thousand).

While some respondents were sanguine, others expressed anxiety about both the Vientiane-Boten Railway and China’s growing socioeconomic presence in Laos. Although such terms as “debts” and “dependency” were not used explicitly by respondents, their comments reflected such concerns or, at least, an awareness of these issues. Some elites, for instance, spoke about the possibility of “restructuring loans,” “exploring ways to work out some concessions and arrangements,” “our law … not allow[ing] foreigners to own land,” and stated that “no foreigners can take our land and property away from Laos.”Footnote26

There are growing concerns that the developmental benefits of China’s economic activities, such as the creation of jobs for the people of Laos and the advancement of transportation, might have been acquired at the expense of Laos’s national identity. They also expressed uneasiness about the over-presence of China in the northern region of Laos. The border town of Boten, for example, is fast becoming a “Chinese city,” with Renminbi (the Chinese currency) and Mandarin being used much more extensively than the Lao Kip and Lao language at restaurants, mini markets, and hotels.

3.2. Public’s views and user experiences

At the societal level, public comments about the Vientiane-Boten Railway are by and large affirmative. Members of the general public who I spoke to at various stations along the rail route, commented that the railway is “transforming peoples’ lives”, “changing the way Lao people travel” either to visit family, for leisure, or for work.Footnote27 Some have used the train as many as a dozen times and many have traveled all over Laos.

The Vientiane-Boten Railway was most frequently described as “faster,” “cheaper,” and “safer.” Some interviewees noted that the five-hour, 336 km road trip from Vientiane to Luang Prabang now only takes two hours by train. The passengers who used to drive, whom I interviewed, described taking the train as “safer” as they recalled the dangers they faced from frequent floods, landslides, and storms. Considering the rising price of gasoline, inflation and the depreciation of the Kip, rail passengers described the price of train tickets as reasonable and affordable.Footnote28 Travel with the railway is much cheaper than plane tickets and even using the highways and roads.

The crowded train platforms and train cars, especially on weekends, suggest that the earlier prediction that the Vientiane-Boten Railway would be a “white elephant” is not true. While there have been public complaints, they have primarily related to ticketing and other operational issues, rather than about the railway per se. More than ten months after the railway was launched, online ticketing was still unavailable and train tickets can only be purchased at train station ticket counters, which operate at certain hours and with several restrictions (e.g. tickets can only be booked three days in advance and each passenger can only purchase a maximum of three tickets). City ticket offices are only located in Vientiane and Luang Prabang, which only allow electronic payment. Accordingly, those who do not want to queue up at the ticket counters or offices often resort to using “agents” who impose extra charges of 20,000–50,000 Kip per ticket. These situations only changed in mid-March 2023, after Laos joined a China-developed all-in-one train ticketing system on a smartphone app, reportedly tailor-made for participating countries of the BRI.Footnote29

Elite assessments and the public’s views are significant because they are the indicators—and incentives—of political legitimation. That is, they combine to reflect the extent to which the key segments of a nation’s domestic constituencies resonate with (or resist against) the principal pathways of government’s inner justification.

In the case of Laos, positive elite assessments and generally affirmative attitudes among the populace about the developmental gains and transformative socioeconomic impacts of the railway have thus far served to echo and enhance the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP) government’s performance legitimation. An increased level of external maneuverability (vis-à-vis the West as well as Laos’s larger neighbors), alongside an increased sense of pride among the ordinary Lao people (having a more advanced transport system than Thailand and other neighboring countries) have also enhanced the LPRP elites’ particularistic legitimation. Longer-term concerns about debts, dependency, and detrimental influences on Lao national identity, however, have to some extent cast a shadow over the governing elites’ authority and overall legitimation.

4. Laos’s host-country agency: mixed, uneven, and uncertain

Laos’s host-country agency over the Vientiane-Boten Railway and the wider BRI has been mixed and uneven. Proactive agency was clearly evident in the early 2000s when Laos’s leaders took the initiative to explore cooperation with China on a number of connectivity ventures, most notably the building of the railway in the landlocked country. According to Ambassador Mai Sayavongs, the Director General of Laos’s Institute of Foreign Affairs:

The construction of the Laos-China railway was in the initiative of the Lao government for a long, long time and had been discussed with China many rounds of talk. The initial proposal was submitted to China in the early 2000s. Nevertheless, the Chinese side responded it was not the right time to build a railway connecting Laos and China. In August 2010, the Lao side sent a delegation to negotiate with the Chinese government. In October 2010 the Chinese government sent teams to work with the Lao side for a feasibility study. It took 4 years to complete the study and to arrive at the decision that it was possible to build [the railway]. In August 2015, Laos and China signed a bilateral agreement. On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Lao PDR on December 2, 2015, the groundbreaking ceremony was held in Vientiane. Construction started on December 2, 2016 and the official opening ceremony was on December 2, 2021.Footnote30

Such host-country agency indicates that the initiation of the rail line was more of a “small-country pull” than a “big-power push.” The pull persists until the present day. In 2022, when the railway was fully operational, Lao proposed that China could connect and integrate the Lao southern regions (including Champasak, Savannakhet, and Khammouane provinces) with the economic corridor along northern and central Laos.Footnote31 As elaborated below, Laos has also actively engaged in policy talks with the Thai authorities to connect the railway with northeastern Thailand, while at the same time developing and enhancing its domestic capacities to maximize the railway’s economic potential. Such proactive efforts and active involvement are clear manifestations of Laos’s host-country agency.

However, there are indicators that during the negotiation and operation phases, Laos has been reactive and at times reluctantly acquiescent, in part a result of the power asymmetry. First, the Laos-China rail cooperation is an unequal partnership. Under the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by the two governments in 2015, the Laos-China Railway Joint Venture Company was formed with 30% owned by Lao state railway and 70% by Chinese state-owned firms. The Vientiane-Boten Railway is operated by a special purpose vehicle joint venture firm, which funds 40% of the project costs. The remaining 60% is financed through a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China. Second, the railway is a highly controversial venture. This is attributable not only to concerns over the project’s high price tag and its fiscal sustainability, but also because of the perceived lack of transparency and other problems surrounding the project. A 22-page document submitted to the Laos National Assembly in 2012, stated that China’s loan would be guaranteed by all of the income and assets of the railway, and two unspecified mining areas.Footnote32 These terms led to concerns about the risks of Lao’s dependency on its big neighbor to the north, especially as China emerged as the top investor in Laos and its second largest trading partner in the recent years.Footnote33

During the protracted negotiation process, there were disagreements between Laos and China over worker arrangements, social and environmental impact, and loan details such as the interest rate.Footnote34 These controversial issues and other governance sensitivities appeared to be among the reasons why, despite the MoU being signed in 2015, commencement of construction was delayed until December 2016. Even after the ground-breaking ceremony in December 2016, internal concerns over the rail project’s financing terms, China’s rights to development along the rail route, and the management of the project operator (the Laos-China Railway Company [LCRC], with China having the majority control) were raised.

While many of the existing concerns have eased since the Vientiane-Boten Railway became operational in December 2021, other have only deepened. Growing dependency on China’s development aid and infrastructure partnerships, for example, has increased anxiety over economic security, as more experts caution against the longer-term impact of crippling debts, heavy fiscal burdens, and the unsustainable extraction of Laos’s natural resources.Footnote35 A World Bank report in 2022 indicated that half of Laos’s US$14.5 billion public debt (about 88% of Laos’s 2021 GDP) was owed to China because of loans to finance infrastructure projects, including the railway.Footnote36

Thus far, there is no available evidence indicating Laos’s ability to renegotiate the unequal aspects of its partnership with China. Laos’s response has appeared to be more reactive and adaptive (e.g. in terms of executing the environmental and social safeguards) and has not (at least not yet) amounted to effective enforcement or passive resistance.Footnote37 While the Lao authorities have attempted to shape the operational aspects of the railway (e.g. through formulation of regulatory framework as well as through efforts to bring employment and economic benefits to local communities along the rail line), it is unclear how strong or effective these attempts have been. The Lao elites have engaged in pragmatic planning and direction-setting (e.g. the “1-3-3” connectivity development plan, discussed shortly) to increase their benefits from the various railway-related projects, but the actual progress and prospects remain to be seen. While the authorities have sought to diversify Lao’s connectivity partnerships, the lack of accessible alternatives means no options have yet been actualized.

These reactive and passive signs notwithstanding, the Lao authorities have exercised host-country agency through active policy planning and implementation at home as well as active connectivity cooperation with its immediate neighbors (Thailand and Vietnam). The internal efforts aim to enhance Laos’s domestic capacity, whereas cooperation with Laos’s neighbors is aimed at establishing and deepening cross-border connectivity at the regional level.

4.1. Active internal planning and capacity-enhancement

The Lao government has been actively planning and implementing the connectivity concept of “1-3-3,” namely “One Corridor, Three Cities, and Three Economic Zones.”Footnote38 The corridor refers to the Laos-China Economic Corridor (LCEC); the cities refer to Vientiane, Luang Prabang, Boten; and the economic zones refer to the Vientiane Saysettha Economic Zone, Luang Prabang, and the Boten-Mohan Economic Zone. The Lao authorities envisage the following division of labor across these zones: Saysettha Economic Zone focuses on manufacturing, Luang Prabang on the service sectors, and the Boten-Mohan Economic Zone focuses on trade. The more integrated LCEC will be linked with and further integrated into other development centers and economic zones in Laos, and potentially with those in the neighboring countries over the long run. Presently there are a total of 12 Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in Laos but only three dry ports. The authorities plan to increase the number of dry ports across the country, with the goal of “one dry port for each SEZ.”Footnote39

4.2. Active connectivity cooperation with immediate neighbors

The Lao authorities have actively engaged and expanded cross-border connectivity cooperation with neighboring Thailand and Vietnam.Footnote40

In 2008, Laos and Thailand launched Phase I (Section 1) of the Lao-Thai Railway Construction Project with the commencement of construction on the 3.5 km Thanaleng-Nong Khai railway. The rail track became operational in March 2009. Phase II (Section I) began in 2013 and was completed in 2017. During this phase a siding track at Thanaleng Station, a 5,800-meter railway mainline extension from Thanaleng station to a container yard, was constructed, and signaling and telecommunication systems were upgraded from analogue to digital.Footnote41 The facilities, especially the container yard, serve as an important logistics center in Vientiane and ease rail transport between Laos and Thailand via Laem Chabang Seaport. Phase I (Section II) followed with the construction of the Khamsavath Railway Station. Work for Phase II (Section II) began in October 2019 and comprised the building of a 7.5 km rail extension from Thanaleng Station to Vientiane Station. The project, financed by a loan from Thailand’s Neighboring Countries Economic Development Cooperation Agency (NEDA), is owned by the Lao Department of Railway, Ministry of Public Work and Transportation.

By collaborating with Thailand on these and related projects, Laos has displayed its agency in actively shaping cross-boundaries connectivity-building and positioning itself as a gateway between China and other parts of Southeast Asia. In 2022, Lao and Thai officials held several meetings to discuss the Thai extension of the Laos-China railway. According to the Vientiane Times, the two sides discussed rail connectivity for passengers and freight, the construction of a new bridge across the Mekong, the possibility of using the old railway bridge, and the installation of a common control area at Thanaleng in Vientiane and at Nong Khai and Na Tha stations in Thailand. Train operations are expected to commence in mid-2023 with four return trips per day, each of which will also pass by the Thanaleng Dry Port and a container yard. The track will then be extended to Thailand’s Udon Thani and Nakhon Ratchasima, and will eventually go further south to Bang Sue Grand Station in Bangkok, thereby connecting the capitals of the two countries.Footnote42 Despite differences in rail gauge (Thai railroad uses meter-gauge track, while the standard Lao rail gauge is 1.435 m), the planned Thailand-Laos Railway will connect with the LCR, enabling passengers and goods to travel from Thailand to China via Laos.Footnote43 As a result, China will be connected with the two Southeast Asian countries and potentially more if and when the planned Thailand-China HSR is connected southwards to Malaysia and Singapore.Footnote44

Laos has also forged ahead with plans for physical infrastructure connectivity with Vietnam. In January 2022, Lao Prime Minister Phankham Viphavanh met with his Vietnamese counterpart Pham Minh Chinh in Hanoi. During the meeting, the Vietnamese leader reaffirmed Hanoi’s commitment to continue allowing Laos to use Vung Ang Port, a deep-water port in Vietnam’s central province of Ha Tinh that borders the Bolikhamsai and Khammouane provinces in Laos. To help Laos connect to the sea and actualize its goal of becoming a regional logistics center, Vietnam has facilitated the transit of freight to and from Laos for many years.Footnote45

5. Analysis: factors driving and limiting Laos’s host-country agency

The mixed and limited patterns of Laos’s host-country agency are a product of both internal and external factors. Above all, political legitimation of the ruling elites has been the principal driver motivating the small state to actively partner with China on various development ventures. However, there are also other domestic and external factors at work. Internally, Laos’s one-party political system and its near absence of societal agency have limited the capacity of the state to establish a positive feedback loop, to act responsively, and to monitor and correct its dealings with China. Externally, the lack of accessible and comparable alternative infrastructure partners to support Laos’s present and planned projects has further constrained Laos’s options in bargaining with China on connectivity cooperation.

5.1. Driver: elite legitimation

Elite legitimation drives the direction of policy choices. The LPRP government has embraced the BRI chiefly because the elites see China’s capital and know-how as crucial to boosting Laos’s developmental growth, and by extension, the party’s political authority and legitimacy.Footnote46

As previously discussed, the LPRP elites view the Beijing-backed north-south rail project and other connectivity cooperation as opportunities to transform Laos into a land-linked nation. Laos’s lack of a coastline limits its growth options. Its economy relies primarily on exporting a limited range of resources, such as minerals and hydropower. Lao elites thus envisage that the railway can help make Laos “a useful go-between” for neighbors sharing its borders, namely China, Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar.Footnote47 They see a range of transformative development benefits for Laos, namely: reducing transportation costs, increasing Laos’s competitiveness, diversifying the Lao economy beyond the resource sector by developing other export industries, attracting greater foreign direct investment (FDI), enhancing the country’s development ecosystem, turning it into a logistic hub for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as integrating it with the vast markets and production centers across Southeast Asia and southern China.Footnote48

These perceived benefits serve to advance and justify the Lao elites’ political authority at home, thereby increasing their performance legitimacy. Phanthanousone Khennavong, an advisor to the Lao Ministry of Planning and Investment, cites an anonymous respondent:

The only way that the Party can prove its legitimacy is to produce tangible outputs … So, to come up with something concrete quickly and to avoid a long process of consultations, the assistance from China has become very attractive for the Party. So far, Chinese aid has been helpful for both the Lao Government and the Party as a number of outputs such as hospitals, roads, schools, sport facilities, conference venues etc. were constructed within a short period of time. … there is no doubt that the Party is strongly committed to further strengthen China-Lao development cooperation as more Chinese aid means more concrete outputs.Footnote49

Beyond performance legitimation, other pathways of inner justification also drive Laos’s receptivity to cooperation with China. A stronger partnership with China will reduce Western political pressure and enable Laos to deal more effectively with its two larger neighbors, Thailand, and Vietnam, thereby enhancing the LPRP’s identity-based ethno-nationalistic justification (a form of particularistic legitimation). As the LPRP struggles to maintain its ideological appeal, enhancing performance- and particularistic-legitimation are key to preserving its political relevance and authority domestically. Moreover, the development projects provide the ruling elites with patronage resources. All in all, the development-based performance legitimation employed by the Lao elites, alongside identity-based and other domestic drivers, underpin Laos’s relatively high receptivity toward cooperation with China on infrastructure and connectivity projects.

Legitimation aside, the institutional configurations of the ODA framework and personal ties between Laos and China are also important factors. Scholar Sunida Aroonpipat suggests that while the ODA framework “is limited in transparency and depends on the preferences of donors,” such “embedded informality” among the key authority figures and the relatively independent line of command helps shape the positive perceptions of high-ranking Lao officials toward Chinese ODA in terms of responsiveness, speed, and predictability of project approvals. Potential misunderstandings have been reduced and several Chinese projects have been implemented smoothly.Footnote50 Accordingly, concerns about economic security risks such as potential dependency, debts, financial sustainability, and related challenges were acknowledged but downplayed, and public discontent managed and controlled.

Nevertheless, the current economic difficulties, as marked by the rising cost of living due to high inflation and the depreciation of the Lao currency, Kip, are seriously affecting household incomes, lowering people’s standard of living, and aggravating public dissatisfaction, thereby undermining the effectiveness of the elites’ inner-justification efforts. In April 2022, the World Bank warned that public debt could reach US$14.5 billion, or 90% of Lao gross domestic product, the majority owed to “bilateral creditors, particularly China”.Footnote51

5.2. Constraining factors: domestic and external determinants

Legitimation drives the direction of agency, but it does not dictate the outcomes. Laos’s mixed and limited agency, as manifested in its disadvantaged position in the negotiation and implementation of the China-funded projects, is constrained by both internal and external determinants.

Laos’s inherent internal inadequacies mean that it has to rely on external sources for financial and technical support for developing its big-ticket infrastructure projects (unlike its neighbor Thailand which possess the option of self-financing some of its mega-projects, including the HSR ventures). This reliance exposes Laos to the risks of unequal (and potentially unfair) treatment, external dependency and other problems. The loan for the Vientiane-Boten Railway project, for instance, is guaranteed by underground mineral resources in Laos. China was granted mining concessions as collateral – should revenue from the railway project be too low to service the debt, China, as the lender, would have the right to extract said minerals as an additional means of securing repayment of the loan.Footnote52 The Lao government has also made several tax concessions, including the waiving of import duties on imported Chinese equipment associated with the project. These moves are all likely to reduce the benefits accruing to Laos.Footnote53 Given the party-state political structure and the lack of openness in Laos, a full picture of the situation is difficult to ascertain.

Laos’s constrained host-country agency can also be seen in other examples. The country’s low internal resilience is reflected in the limited ability of authorities to perform some governance functions and to secure a strong commitment from their Chinese partners, either to protect Laos’s financial position or to safeguard the country’s environment and resources.Footnote54 In view of the fact that the Lao authorities may never be able to fulfil the equity requirement as originally designed, the China Exim Bank re-adjusted the ratio of cash capital to land assets in the equity composition, agreeing to accept more of the latter. The joint venture was thus asked to select additional valuable land parcels along the railway and proposed that they be held by the Lao state as equity for the loan.Footnote55

Additional governance issues are present, most notably the lack of transparency and the lack of stakeholder engagement.Footnote56 Many of these are chiefly attributable to the authoritarian nature of Laos’s political system as well as the practices of China’s state-owned entities, which tend to rely largely on local standards rather than on the social safeguards employed by global financial watchdogs. As a communist-ruled state with no independent media and very limited civil society groups, the Lao one-party political system is characterized by high power concentration and weak institutionalized checks-and-balances. Decisions and dealings are often made through political power and personalized networks. Policy disagreements among party elites and officials are usually aired behind closed doors.Footnote57 Such a system impedes a culture of transparency, discourages open expression of views, and suppresses societal voices over the implementation of big-ticket development projects, including those funded by foreign entities.

For the general public, the main issues surrounding the Vientiane-Boten Railway have been resettlement, land acquisition, and adequate compensation for individuals and communities adversely affected by the project construction. While the Lao PDR government Decree on Compensation and Resettlement Management in Development Projects (“Decree 84”) provides the basis for addressing these issues, challenges related to implementation problems, financial limitations, and the lack of robust social safety standards, still remain.Footnote58 Scholar Oliver Tappe observes that many families were displaced by the project but due to delays in compensation payments, they could not afford to relocate themselves.Footnote59 The government’s negligence, coupled with harassment from land investors and security forces, all contributed to local resentment.

The above internal complexities and inadequacies have been complicated by the lack of external options. China is not the only source of infrastructure financing for Laos; it is a latecomer compared to Japan, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank (WB). Japan has long been Laos’s key development partner (see below). However, after 2012, there have not been many major Japan-funded projects in the country while multilateral lenders, WB and ADB, have continued to fund Laos’ infrastructure projects (the latest ones in 2018 and 2022, respectively), the scope and scale of their financing have been overtaken by that of China.Footnote62

Table 3. Major infrastructure projects funded by JICA, ADB, and WB in Laos.

For Laos, the partnership with China is not necessarily a preferred choice, but a major available option under the current circumstances. Although Japan has been a longstanding and important development partner, as noted, a member of the Lao elites opined that over the past decade Japan has seemed “too concerned about governance issues,” “too attentive to every single detail,” and has been “swayed away to Vietnam and other countries.” He contrasted that with China’s pattern of cooperation: “China comes [to Laos], even when some projects are perceived to be ‘zero profit.’ China just come[s], making [its] presence [felt], forging cooperation. Then opportunities [for both sides] will follow.”Footnote60 He stressed: “Laos is open for every country. It depends on other countries to see the potentials and values of Laos [as a partner or host country] to forge cooperation and partnership [emphasis added].”Footnote61

In virtually all interviews, the Lao elites I talked to emphasized the importance of diversification; many highlighted “East-West” development corridor when the “North-South” corridor was mentioned, and most alluded to what Lampton et al. have termed “balanced connectivity” – a connectivity that “multiplies points of interdependence rather than simply focuses on links to China.”Footnote63 Laos, like many of China’s neighbors to the south, wants to see an injection of connectivity balance into the geopolitical and geo-economic equations. The Lao elites view the West, particularly the United States, as being reluctant to engage with Laos due to human rights and other political issues. In contrast, the elites are hopeful that other Asian countries, especially Japan and South Korea, will increasingly engage with Laos, thereby providing credible and sustainable alternative partnership opportunities. Balanced connectivity is seen as the way to increase the leverage of smaller states when bargaining with China vis-à-vis the BRI-related projects.

Several respondents expressed that there is a need for Japan to revitalize and enhance its role in Laos’s development, especially in relation to connectivity-building. While Japan still provides significant financial aid to Laos, it is behind China on virtually all other economic indicators. China is not only one of Laos’s top trading partners and the source of the largest number of tourists in the country, but also the largest provider of FDI. From 2001 to 2021, China invested more than US$10 billion in Laos; over the same 20-year period, Thailand and Vietnam invested $4.7 billion and $3.9 billion, respectively, while Korea and Japan’s FDI stood at $751 million and $180 million, respectively.Footnote64 A similar trend is discernible in aid financing. Kearrin Sims notes that while it is difficult to make precise comparisons between development financing from the Chinese and OECD donors (because China doesn’t adhere to the same lending or reporting systems), the broad consensus among experts is that “China has now matched or exceeded Japan in terms of its development financing.”Footnote65 These trends, in effect, have reduced room for Laos to pursue economic hedging. As China is becoming one of the few principal sources of funds for Laos’s present and future infrastructure projects, Laos is limited in its ability to bargain and exercise its agency.

6. Conclusions

To conclude, host-country agency is a central element in understanding the progress and problems of such foreign-backed connectivity cooperation as China’s BRI-related projects in Asia and elsewhere. Although China as a much more powerful country would always push its agenda in all partnerships, host governments can and often do exercise agency in shaping the process and prospects of the joint ventures. In the case of Laos, as discussed in this essay, the small state has demonstrated some degree of agency by taking the initiative to partner with China on the railway and other projects. Laos has also been proactive in forging connectivity cooperation with its immediate neighbors while actively seeking to enhance its capacity and advance Laos’s envisaged role as a regional logistics hub and development gateway (rather than as a country of “transit”) in the widening regional connectivity. Laos’s host-country agency, however, is mixed, constrained, and uncertain. Thus far, its record of interacting with China during the negotiation and implementation stages has been marked by passive and reactive elements. Such a mixed pattern of agency is the result of weak internal resilience and a lack of accessible external alternatives.

These findings have both theoretical and policy implications. Theoretically, the findings highlight that small-state agency in connectivity cooperation (or for that matter, any form of inter-state partnerships) is determined not only by the host country’s relative size and strength, but also its internal and external conditions. The availability and the relative range of external alternative partnerships, on one hand, determine the relative room for a small state to exercise its bargaining capacity vis-à-vis its stronger partner(s). Internal resilience, on the other, determines the host country’s relative ability to pursue its prioritized policy ends wherever possible, and to push back and protect its interests whenever necessary. In addition, the findings also indicate that the elite’s political need to optimize their internal legitimacy is the principal driver that determines the direction, extent and sustainability of a state’s receptivity toward a foreign-backed connectivity partnership.

Policy wise, the preceding analysis underscores the need for multiple external powers to play a bigger role in promoting balanced connectivity in infrastructure cooperation across the region. This role is particularly acute in such small developing countries as Laos. External partners could cultivate balanced connectivity by stepping up cooperation with Laos on connectivity ventures in ways which broaden alternative partnerships for the landlocked country. Particular attention should be paid to the following three sectors: (a) sectors where Laos needs the most assistance (e.g. enhancing Laos’s domestic capacity to serve as a gateway for regional integration); (b) sectors where a particular external partner enjoys a comparative advantage; and (c) sectors with profound long-term geo-economic impact.

Future studies should focus on unpacking how and why an elite’s legitimacy optimization efforts lead a state to balance the policy tradeoffs across the sectoral, spatial and temporal terms the way it does under given internal and external circumstances. Addressing these interrelated themes will make important contributions to several bodies of scholarly literature: small-state agency in infrastructure connectivity cooperation, links between political legitimation and policy choices, as well as resilience in authoritarian regimes.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Alvin Camba, Fong Chin Wei, Shiga Hiroaki, Naohiro Kitano, Phouphet Kyophilavong, Kaewkamol Pitakdumrongkit, Soulatha Sayalath, Mai Sayavongs, Akio Takahara, and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. Any shortcomings are the authors’ own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cheng-Chwee Kuik

Cheng-Chwee Kuik is Professor of International Relations and Head of Asian Studies at the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), National University of Malaysia (UKM). He is concurrently a non-resident Fellow at Johns Hopkins SAIS Foreign Policy Institute. Previously, he was a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Princeton-Harvard “China and the World” Program. Professor Kuik’s research focuses on small-state foreign and defence policies, Asian security, and international relations. Cheng-Chwee’s publications have appeared in such peer-reviewed journals as International Affairs, Pacific Review, Journal of Contemporary China, Chinese Journal of International Politics, and Contemporary Southeast Asia. He is co-author (with David Lampton and Selina Ho) of Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia (2020) and co-editor (with Alice Ba and Sueo Sudo) of Institutionalizing East Asia (2016). His current projects include: hedging in international relations, elite legitimation and foreign policy choices, and host-country agency in connectivity cooperation. Cheng-Chwee serves on the editorial boards of Contemporary Southeast Asia, Australian Journal of International Affairs, Asian Politics and Policy, International Journal of Asian Studies, and East Asian Policy. He holds an M.Litt. from the University of St. Andrews and a PhD from Johns Hopkins University.

Zikri Rosli

Zikri Rosli holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from International Islamic University Malaysia and a Master’s Degree in East Asian Studies from National University of Malaysia (UKM). He is an Associate Analyst at Bait Al Amanah, a political development think tank in Kuala Lumpur.

Notes

1 Takahara, “The Rise of China;” Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron.

2 Parsons, The Social System; Giddens, The Constitution of Society; Sewell, “A Theory of Structure;” Wight, Agents.

3 Goh, Rising China’s Influence; Oh, “Power Asymmetry;” Carrai, Defraigne, and Wouters, The Belt and Road Initiative; Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron; Schneider, Global Perspectives; and Kuik, “Asymmetry and Authority.”

4 Schneider, Global Perspectives, 25.

5 Camba, “Derailing Development.”

6 Bottomore, Elites and Society; Lipset and Solari, Elites in Latin America; Parry, Political Elites; Axelrod, Structure of Decision; Camba, Cruz, and Lim, “Contradictory Infrastructures.”

7 Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron; Kuik, “Asymmetry and Authority.”

8 Ibid.

9 See, for instance, articles in the Special Issue in Asian Perspective, Volume 45, Number 2, 2021, especially Kuik, “Asymmetry and Authority;” Yeremia, “Explaining Indonesia’s Constrained Engagement.” See also Wang and Fu, “Local Politics and Fluctuating Engagement;” Lim, Li, and Syailendra, “Why Is It So Hard.”

10 Pham and Ba, “Vietnam’s Cautious Response.”

11 Liao and Dang, “The Nexus of Security;” Yan, “Navigating between China and Japan;” Pitakdumrongkit, “What Causes Changes.”

12 Kuik, “Interlude” See also Kuik, “Southeast Asia Hedges.”

13 Schindler and DiCarlo, Rise of Infrastructure State.

14 Cavelty et al., “Resilience and (In)security;” and Brassett and Vaughan-Williams, “Security.”

15 Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron, 89–91.

16 Kuik, “Elite Legitimation”.

17 Kuik, “Laos’s Enthusiastic Embrace”; HKUST Institute for Emerging Market Studies, “The Belt and Road”; Kishimoto, “Laos Deepens Reliance”; International Rivers, “Nam Ou River Cascade”; “China-backed Gold Mine”; “China’s Chifeng Jilong Restarts”; “Chinese Firm Signs MoU”; “Laos, China Sign”.

18 Ibid.

19 “Lao DPM Hails Railway.”

20 Constructed between October 2006 and May 2008 with financial support from Thailand, the railway began operations in March 2009.

21 Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron; Kuik, “Laos’s Enthusiastic Embrace”.

22 Interviews, Vientiane, September 2022.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 “China-Laos Railway.”

26 Interviews and informal conversations, Vientiane, Luang Prabang, Muang Xay, September 2022.

27 Ibid.

28 Interviews and conversations in Vang Vieng, Luang Prabang, Muang Xay, and Luang Namtha, September 2022.

29 Chen, “China Offers Joined-up Rail.”

30 Personal e-communication, September 2023.

31 Interview, Vientiane, September 2022.

32 “High Speed Rail.”

33 Chinese direct investment jumped from US$846 million in 2010 to US$6.65 billion in 2017, making Laos the 6th highest receiver of Chinese FDI in Asia and the 16th worldwide. See Chen, The Power of Mirage.

34 Doig, High-Speed Empire; Personal communications with Lao researchers, June 2019.

35 Sims, “High Modernism;” Morris, “The Kunming-Vientiane Railway.”

36 Lo, “Chinese President Xi Jinping.”

37 DiCarlo, “Lost in Translation.”

38 Interview with a senior governmental official in Vientiane, September 2022.

39 Interview, Vientiane, September 2022.

40 Ibid.

41 “Section II of Lao-Thai.”

42 “Laos, Thailand Mull Plans.”

43 “Railway Extension between Laos.”

44 Cooperation between Laos and Thailand on the new railway is taking place at the same time as Thailand is collaborating with China on the Thailand-China HSR, designed to have a maximum speed of 250 km per hour. The first phase of the HSR project, a 253 km standard-gauge railway from Bangkok to Nakhon Ratchasima, which has been under construction in stages since December 2017, is expected to open for operation in 2026. The project’s second phase, a 356k m line between Nakhon Ratchasima and Nong Khai, will be proposed to the Thai cabinet for approval in 2023, with construction expected to begin in 2024. The project is planned for completion in 2028. The planned new bridge over the Mekong between Thailand and Laos is being designed to accommodate two regular rail links and two HSR links to allow trains to cross without having to wait until the other train passes. See Wancharoen and Hutasingh, “High-Speed Train.”

45 Vu, “Vietnam Allows Laos.”

46 Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron; Kuik, “Laos’s Enthusiastic Embrace”. On LPRP regime security, see Sayalath and Creak, “Regime Renewal in Laos”; Baird, “Party, State and the Control”.

47 Peter, “Laos Braces for Promise.”

48 Kyophilavong et al., “The Impact of Chinese FDI;” Suhardiman et al., “(Re)constructing State Power.”

49 Khennavong, “Chinese Aid to Laos.”

50 Aroonpipat, “Governing Aid from China.”

51 Jones, “Laos” Fast Train.”

52 Freeman, “Laos’s High-Speed Railway”; Tappe, “On the Right Track?”.

53 Morris, “The Kunming-Vientiane railway.”

54 DiCarlo, Rise of Infrastructure State.

55 Chen, The Power of Mirage.

56 DiCarlo and Ingalls, “Multipolar Infrastructures”; and Kuik, “Laos’s Enthusiastic Embrace”. See also Creak and Barney, “The Role of ‘Resources’”.

57 Creak and Barney, “Conceptualising Party-State Governance;” and Chen, The Power of Mirage.

58 Morris, “The Kunming-Vientiane Railway,” 18–20.

59 Tappe, “On the Right Track?.”

62 Japan International Cooperation Agency, “List of JICA’s Cooperation in Laos;” Asian Development Bank, “Projects & Tenders;” World Bank, “Lao National Road 13 Improvement and Maintenance..”

60 Interviews with government and policy elites, Vientiane, September 2022.

61 Interview 2022.

63 Lampton, Ho, and Kuik, Rivers of Iron.

64 In 2019, China’s FDI totaled US$1 billion, compared to Japan’s US$22 million. See Sims, “On China’s Doorstep.”

65 Sims, ibid.

Bibliography

- Aroonpipat, S. “Governing Aid from China Through Embedded Informality: Institutional Response to Chinese Development Aid in Laos.” China Information 32, no. 1 (2018): 46–68. doi:10.1177/0920203X17730330.

- Asian Development Bank. “Projects & Tenders.” Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.adb.org/projects/country/lao-peoples-democratic-republic.

- Axelrod, R., ed. Structure of Decision: The Cognitive Maps of Political Elite. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Baird, I. G. “Party, State and the Control of Information in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Secrecy, Falsification and Denial.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48, no. 5 (2018): 739–760. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1451552.

- Bottomore, T. Elites and Society. London: Penguin Books, 1964.

- Brassett, J., and N. Vaughan-Williams. “Security and the Performative Politics of Resilience: Critical Infrastructure Protection and Humanitarian Emergency Preparedness.” Security Dialogue 46, no. 1 (2015): 32–50. doi:10.1177/0967010614555943.

- Camba, A. “Derailing Development: China’s Railway Projects and Financing Coalitions in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.” GCI Working Paper No. 008. Boston, MA: Global Development Policy Center, 2020. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2020/02/05/derailing-development-chinas-railway-projects-and-financing-coalitions-in-indonesia-malaysia-and-the-philippines/

- Camba, A., J. Cruz, and G. Lim. “Contradictory Infrastructures and Military (D)alliance: Philippine Elite Coalitions and Their Response to US–China Competition.” In The Rise of the Infrastructure State, edited by S. Schindler and J. DiCarlo, 89–105. Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2022.

- Carrai, M., J.-C. Defraigne, and J. Wouters. The Belt and Road Initiative and Global Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020. doi:10.4337/9781789906226.

- Cavelty, M. D., M. Kaufmann, and K. S. Kristensen. “Resilience and (In)security: Practices, Subjects, Temporalities.” Security Dialogue 46, no. 1 (2015): 3–14. doi:10.1177/0967010614559637.

- Chen, S. “China Offers Joined-Up Rail Ticketing to Belt and Road Countries.” South China Morning Post, April 6, 2023. https://scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3214757/china-offers-joined-rail-ticketing-belt-and-road-countries.

- Chen, W. “The Power of Mirage: State, Capital, and Politics in the Grounding of ‘Belt and Road’ in Laos.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2020.

- “China-Backed Gold Mine in Laos Pollutes Local River, Killing Fish.” Radio Free Asia, November 2, 2021. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/laos/pollutes-11022021183052.html.

- “China-Laos Railway Transit Yard Put into Operation for Transporting Goods to Thailand.” Xinhua, July 2, 2022. https://english.news.cn/asiapacific/20220702/f32faa5500fb4eda807e2901c49351f3/c.html

- “China’s Chifeng Jilong Restarts Gold Production at Laos Mine After 6 Yrs.” Reuters, May 17, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/china-gold-laos-idUKL4N2CZ015.

- “Chinese Firm Signs MoU on Agriculture Development Project in Laos.” Xinhua, April 8, 2021. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-04/08/c_139866707.htm.

- Creak, S., and K. Barney. “Conceptualising Party-State Governance and Rule in Laos.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48, no. 5 (2018): 693–716. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1494849.

- Creak, S., and K. Barney. “The Role of ‘Resources’ in Regime Durability in Laos.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 55, no. 4 December 1 (2022): 35–58. doi:10.1525/cpcs.2022.1713051.

- DiCarlo, J. “Mind the Gap: Grounding Development Finance and Safeguards Through Land Compensation on the Laos-China Belt and Road Corridor.” GCI Working Paper No. 013. Boston, MA: Global Development Policy Center, 2020. 10.13140/RG.2.2.17892.30088

- DiCarlo, J. “Lost in Translation: Environmental and Social Safeguards for the Laos-China Railway.” BU Global Development Policy Center, February 11, 2021. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2021/02/11/lost-in-translation-environmental-and-social-safeguards-for-the-laos-china-railway/.

- DiCarlo, J., and M. Ingalls. “Multipolar Infrastructures and Mosaic Geopolitics in Laos.” In The Rise of the Infrastructure State, edited by S. Schindler and J. DiCarlo, 180–193. Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2022. doi:10.51952/9781529220803.ch013.

- Doig, W. High-Speed Empire: Chinese Expansion and the Future of Southeast Asia. New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2018. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1fx4hhg.

- Freeman, N. “Laos’s High-Speed Railway Coming Round the Bend.” ISEAS Perspective 101 (2019): 1–7.

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Goh, E., ed. Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Han, Y. “Laotian Businesses Urged to Make Full Use of New Opportunities.” China Daily, August 31, 2022. https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202208/31/WS630eb9ada310fd2b29e75240.html

- “High Speed Rail Could Bankrupt Laos, but It’ll Keep China Happy.” The Conversation, April 7, 2014. https://theconversation.com/high-speed-rail-could-bankrupt-laos-but-itll-keep-china-happy-22657

- HKUST Institute for Emerging Market Studies. The Belt and Road Initiative in ASEAN. Hong Kong: HKUST Institute for Emerging Market Studies, 2020.

- International Rivers. “Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project,” March 24, 2022. https://www.internationalrivers.org/news/nam-ou-river-cascade-hydropower-project/.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. “List of Jica’s Cooperation in Laos.” Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.jica.go.jp/Resource/laos/english/activities/activity.html.

- Jennings, R. “Japan, Thailand, Vietnam Vie with China for Influence in Impoverished, Landlocked Laos.” VOA News, April 23, 2021. https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_japan-thailand-vietnam-vie-china-influence-impoverished-landlocked-laos/6204950.html

- Jones, A. “Laos’ Fast Train to China Brings Connection at a Cost, with Big Promises but Uneven Progress.” South China Morning Post, October 29, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3197616/laos-fast-train-china-brings-connection-cost-big-promises-uneven-progress.

- Khennavong, P. “Chinese Aid to Laos – a Mixed Blessing.” 2015. https://devpolicy.org/2015-Australasian-aid-conference/presentations/1d/Pepe-Khennavong.pdf

- Kishimoto, M. “Laos Deepens Reliance on China for Key Transport Projects.” Nikkei Asia, July 12, 2021. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Belt-and-Road/Laos-deepens-reliance-on-China-for-key-transport-projects.

- Kuik, C.-C. “Asymmetry and Authority: Theorizing Southeast Asian Responses to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Asian Perspective 45, no. 2 (2021): 255–276. doi:10.1353/apr.2021.0000.

- Kuik, C.-C. “Elite Legitimation and the Agency of the Host Country: Evidence from Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand’s BRI Engagement.” In Global Perspectives on China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Asserting Agency Through Regional Connectivity, edited by F. Schneider, 217–244. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021. doi:10.1515/9789048553952-010.

- Kuik, C.-C. “Irresistible Inducement? Assessing China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia.” Council on Foreign Relations, 2021 https://www.cfr.org/sites/default/files/pdf/kuik_irresistible-inducement-assessing-bri-in-southeast-asia_june-2021.pdf

- Kuik, C.-C. “Laos’s Enthusiastic Embrace of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Asian Perspective 45, no. 4 (2021): 735–759. doi:10.1353/apr.2021.0042.

- Kuik, C.-C. “Interlude: Locating Host-Country Agency and Hedging in Infrastructure Cooperation.” In The Rise of the Infrastructure State, edited by S. Schindler and J. DiCarlo, 194–210. Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2022. doi:10.51952/9781529220803.ch014.

- Kuik, C.-C. “Southeast Asia Hedges Between Feasibility and Desirability.” East Asia Forum, July 4, 2023. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2023/07/04/southeast-asia-hedges-between-feasibility-and-desirability/.

- Kyophilavong, P., X. Bin, B. Vanhnala, P. Wongpit, A. Phonvisay, and P. Onphandala. “The Impact of Chinese FDI on Economy and Poverty of Lao PDR.” International Journal of China Studies 8, no. 2 (2017): 259–276.

- Lampton, D. M., S. Ho, and C.-C. Kuik. Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020.

- “Lao DPM Hails Railway as Pride of Laos.” Bangkok Post, December 4, 2022. https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2452844/lao-dpm-hails-railway-as-pride-of-laos

- “Laos, China Sign an Agreement on Clean Agriculture Cooperation.” Lao News Agency, March 20, 2023. https://kpl.gov.la/En/detail.aspx?id=72066.

- “Laos, Thailand Mull Plans for Vientiane-Nong Khai Railway.” Vientiane Times, October 11, 2022. https://www.vientianetimes.org.la/freeContent/FreeConten197_Laothai.php

- Liao, J. C., and N.-T. Dang. “The Nexus of Security and Economic Hedging: Vietnam’s Strategic Response to Japan–China Infrastructure Financing Competition.” The Pacific Review 33, no. 3–4 (2020): 669–696. doi:10.1080/09512748.2019.1599997.

- Lim, G., C. Li, and E. A. Syailendra. “Why is It so Hard to Push Chinese Railway Projects in Southeast Asia? The Role of Domestic Politics in Malaysia and Indonesia.” World Development 138 (2021): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105272.

- Lipset, S. M., and A. Solari, eds. Elites in Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.