ABSTRACT

This paper examines how the Bangladeshi online media argues the country’s bilateral relations with bigger states by examining the media coverage on China, Japan, the US, and India. Methodologically, the study was conducted by combining quantitative text mining and qualitative analysis using the pentagonal model. The result shows that the Bangladeshi media publishes mostly economic related issues relating to each bigger state in line with the relationships based on investment, infrastructure, manufacture and exports between them and Bangladesh. In addition, comments on what Bangladesh expects to gain from bigger states are also observable. While Bangladesh faces various political and security issues with each of the bigger states, the media narrative is that the government is actively addressing these issues with the political motivation to enhance economic development, proactively engaging in balanced diplomacy while avoiding being passive and disadvantaged vis-à-vis the bigger states.

1. Introduction

Today’s global society is changingFootnote1 at a rapid pace, driven by advanced digitalization, and continuous evolution. The barriers of information disparity that existed within a country and the international community are gradually being broken down by digitalization on a global scale. This profound change is not only transforming the daily lives of people and societies downstream, but also upstream including the interrelations between big and small countries.Footnote2

The purpose of this paper is to examine how the Bangladeshi online media cover the bilateral relations between bigger states such as China, Japan, the US and India, and to explore the media’s argument on the relations between Bangladesh and these bigger states. There are three reasons for choosing the online media in Bangladesh as a case study. First, Bangladesh is one of the fastest growing developing countries in the number of internet users and online news platforms. Internet users have increased dramatically from 4% in 2010 to 25% in 2020Footnote3 and digital media have entered public life, providing opportunities for different groups to influence political events in the country.Footnote4 Second, since Bangladesh is considered a quasi-democracy and media freedom is observed as being limited, media coverage is not expected to diverge significantly from government policy.Footnote5 Third, as a smaller state, Bangladesh pursues its own national interests with all-weather-diplomacy and its proactive agency vis-à-vis bigger states that takes advantage of its geopolitical location in stimulating bilateral debate. Combining these reasons, Bangladeshi online media is a good showcase for the exploration of how smaller state media observe and argue a country’s bilateral relations with bigger ones.

This research selected two Bangladeshi online media platforms to collect samples of articles about China, Japan, the US, and India, and conducted an analysis of these samples in three steps. The first step was to undertake text mining to statistically extract the most frequently used keywords in articles about each state. The second step was to identify the major media frame from the result of co-occurrence network analysis. And the third step was to qualitatively analyze the content of the major articles to identify the political motivation to shape the bilateral relations with bigger states using the pentagonal model elaborated in the introductory paper of this Special Issue.

The analysis revealed the following. The most frequent topics published by the Bangladeshi media covered economic issues relating to each of the bigger states, especially articles about investment, infrastructure, manufacturing, and exports. The sectors and issues emphasized in relations with each bigger state are also distinctive: infrastructure construction with China, private investment with Japan, human rights and lifting of sanctions with the US, and a strong political will to strengthen connectivity and resolve water and security issues with India were evident. Furthermore, there is also an indication of Bangladesh’s expectations toward each of the bigger states. For example, the cooperation with China through mediation and humanitarian assistance to resolve the Rohingya issue caused by Myanmar, the continuation of Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) after Least Developed Country (LDC) graduation for Japan, access to the US market, and trade expansion with India. To meet these expectations, the media narrative is designed to show that the government is actively addressing the issues and challenges that exist with each larger state, while proactively conducting balanced diplomacy among them.

This paper is organized in four sections. The first explains the analytical and methodological framework. The second provides an overview of the media environment and online media platforms in Bangladesh. The third presents the results of analysis on the content of media coverage about China, Japan, the US, and India. And the fourth discusses the characteristics and commonalities revealed by the comparative analysis of media coverage. The fifth section concludes by discussing the relevance of smaller state media studies for understanding bilateral relations with bigger states.

2. Theoretical and analytical framework

2.1. Perspective of media studies

According to traditional media studies, which have theorized the role of the media and its impact on society, effectiveness is organized into three aspects: effectiveness and efficacy, time frames of the past or future, and the level a which effects occur – individuals, the group, the institutions, the whole society or the culture.Footnote6 So far, most media effects have been studied at the individual level, often aimed at drawing conclusions about collective or higher levels.Footnote7 However, limitations on the level and scope of influence should be pointed out. While “society as a whole” is mentioned as a collective and higher level to be influenced by the media, it could be broken down to “national society” and “international society.” Moreover, even “national society” and “international society” can be broken down further by various social characteristics, such as developed or developing countries, bigger or smaller states, or democratic or authoritarian systems, Western or non-Western value-based, and so on. This gap is due to the limitations of single-disciplinary analysis within media studies, and this criticism can be justified by looking at the different paths within which media research on developed and developing countries has been nurtured.

Media studies to date have developed in the following five streams, mainly in Europe and the US: (1) American mass communication studies; (2) critical Marxist commentary; (3) semiotic analysis developed in the context of European structuralism and post-structuralism;(4) critical studies of media audiences that emerged in the UK; and (5) anthropological studies of media that emerged from postmodern versions of symbolic anthropology.Footnote8 Media studies in developing countries, on the other hand, have an anthropological specificity along the historical timeline of: (1) colonialism; (2) the colonial period; (3) post-independence; and (4) post-democratization.Footnote9 In addition, scholarly attention to media in developing countries has focused on how domestic media in former colonial countries have developed, how they have been democratized, and what challenges are remaining in achieving media freedom today.Footnote10 Then, a few questions arise here. Have the media of the smaller developing countries on the so-called non-Western side been given enough attention to understand the dynamics of international relations? Has there been enough analysis of the media coverage of the smaller states to understand the factors that shaped the stories? Have the messages sent by the media of smaller states to domestic and international society been analyzed from the perspective of international relations? The answer is “not sufficient yet.”

2.2. Perspective from the media of smaller states

There are two backgrounds to the abovementioned question. The first is the rapid development of digital media. This technological innovation has provided both developed and developing countries, where information gaps used to exist, with the opportunity to build new information infrastructures, and the web of information has become much denser while expanding globally. As a result, the barriers to information and communication have gradually been broken down, not only bringing the media and the audience closer together, but also influencing international relations through applying digital diplomacy.Footnote11 Second, a new geopolitical concept of the Indo-Pacific has emerged with the rise of China. Developing countries, which in the past have been relegated to the periphery of the international community as former colonies and recipients of aid, are changing their passive and subordinated position. Although the US and China, locked in a standoff over the Indo-Pacific, are trying to attract smaller countries in the region with aid and investment, these are beginning to proactively negotiate and exercise agency with a calculation of national interests that the bigger states seek in their own countries.Footnote12

Previous studies have analyzed how the media in smaller countries report on their bilateral relations with China. For example, the domestic media in the Philippines clearly shows a sense of competition with China over the Spratly Islands.Footnote13 On the other hand, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Serbia, positive coverage of the Serbian government’s praise of Chinese leaders through vaccine diplomacy resulted in an increase in domestic support for China.Footnote14 These two cases show that a smaller state’s policy toward a bigger state can be a matter for wider discussions in their media. While the case of the media in Zambia provides another type of research to examine China’s proactive attempts to influence the public in Zambia,Footnote15 a South African case study analyzes the media frame and shows that there is a growing resonance with anti-Chinese narratives, particularly those espoused by the West.Footnote16 The previous studies on media and Bangladesh-China relations analyzed the production process.Footnote17

There are a growing number of media studies on small countries that focus on their relations with China, however, there is no comparative study that includes several bigger states, especially regional powers. This study, therefore, spotlights the Bangladeshi online media’s coverage of China, Japan, the US, and India analyzing the various events and incidents to qualitatively decipher the factors that small countries value in building bilateral relations with bigger states.

2.3. Methodology

As a method, this study undertakes analysis in three steps with combination of quantitative text mining and qualitative analysis using the pentagonal model.

The first step is to quantitatively analyze the content of sample media by text mining using free software called KH CoderFootnote18 to extract the most frequently used keywords. The second step is to cluster the topics formed by the extracted frequent words using KH Coder’s co-occurrence network analysis and identify the main media frame. The media frame is a comprehensive theoretical model of the interaction between information sources and media-constructed environments that has four criteria: (1) conceptual and linguistic characteristics; (2) observable in journalistic practice; (3) reliably distinguishable from other frames; and (4) recognizable by others.Footnote19 It is defined as the process of culling elements of perceived reality and assembling a narrative that highlights connections to promote a particular interpretation. Moreover, its effects depend on a mix of factors including the strength and repetition of the frame, the competitive environment, and individual motivations.Footnote20 This study follows the frame categorization of “human impact,” “powerlessness,” “economics,” “moral values,” and “conflict” as the most common generic frames used to capture the main frame used by the Bangladeshi media.Footnote21 The third step involves, based on the pentagonal model, observation of the statements and analysis of politicians, journalists, and intellectuals in the news to explore the characteristics that Bangladesh considers important in its bilateral relations with each bigger state. In addition, the study looks at the investment, infrastructure, manufacture, and export as an axis to capture the development priorities of Bangladesh in relation to the bigger states.

3. Overview and sample of media

3.1. Rational to choose Bangladesh and its media

Bangladesh and its media were selected as the case study for three reasons. First, Bangladesh has a clear national goal of graduating from the LDC by 2026,Footnote22 and its policies toward bigger states such as China, Japan, the US, and India are formulated around this goal. In recent years, the increase in foreign direct investment has been significant among the countries of the Indo-Pacific region. Economic growth is also remarkable due to the growth of the manufacturing sector led by the apparel industry.Footnote23 The country is increasingly attracting attention as an emerging economy that could make a significant contribution to the regional economic development of South Asia. Second, only 50 years have passed since independence in 1971, and while it claims to be a democratic country the reality is closer to that of a quasi-democratic state.Footnote24 The recent economic growth has been achieved under the strong policies and control of the current administration. There is also observation that freedom of the press has been restricted, leading the media to be more pro-government.Footnote25 In other words, media coverage is not expected to diverge significantly from government policy. Third, although Bangladesh is a small state having most of its border with India, with only a narrow strip of land connecting it with Myanmar on its east, its geopolitical nature contributes to the political and economic competition between China and India, and China and the US, over strengthening their influence and presence in the country. Moreover, its location on the Bay of Bengal adds to its maritime strategic importance in the region. Since independence Bangladesh has pursued a traditional diplomatic approach of becoming an all-weather-friend, and even in recent years, there has been a growing academic debate on the agency that Bangladesh exerts vis-à-vis bigger states.Footnote26 For these reasons, Bangladeshi media coverage could be good showcase to explore how the media of smaller states argue their government’s bilateral relations with bigger states.

3.2. Overview of media environment in Bangladesh

Previous academic research on the media in Bangladesh has revolved around four main points: (1) the importance of press freedom in the dynamics of democracy; (2) the political economy of the media industry, media credibility and ethics; (3) how the media can contribute to development and social change; and (4) the readability of newspapers.Footnote27 With regard to the previous research on media freedom in Bangladesh, five areas:(1) media’s role in elections; (2) fake news; (3) state control; (4) the impact of laws on digital media; and (5) the impact of market demand, have been the main subjects of study.Footnote28 Elections are held regularly in Bangladesh as a practice of democracy; however, critics point out that the reality as authoritarian or at least hybrid.Footnote29 In fact, Freedom House scored the Bangladeshi net freedom as 43 out of 100Footnote30 in 2023 and Press Freedom Index produced by Word Bank was 39.40 in 2022 declined from 41.23 in 2021.Footnote31 Current media-related laws and regulations originate from the British colonial period (1857–1947). While the government is aware of the shortcomings of the laws and regulations, there is a lack of political will to undertake truly comprehensive reform.Footnote32 Applying the three principles of media regulation forms observed in the scholarly literature, Bangladesh can be described as a mixture of “state monopoly ownership,” “control of the media,” and “public service monopoly.”Footnote33

Bangladesh, the world’s fourth most populous country, has 98% of its population as native Bangla speakers, and there are more than 100 newspapers in the local Bangla language. The largest number of English-language newspapers are published in the capital city of Dhaka. Major English-language newspapers with online platforms include the Daily Star, Independent, Dhaka Tribune, New Age, Daily Sun, Financial Express, Daily Observer, The Bangladesh Today, The Asian Age, New Nation, News Today, Prothom Al Bangladesh, The Good Morning, and the Bangladesh Post. Of these, the Daily Start has the largest circulation, followed by the Independent, Daily Sun, New Age, and Dhaka Tribune. With the exception of the New Age, which is known for its anti-establishment editorial policy, these major newspapers are owned by large corporate conglomerates.Footnote34

3.3. Sample data

In this study, the “Daily Star” and “Daily Sun” were selected as sampleFootnote media based on three conditions: (1) leading media with large readership; (2) free online access; and (3) published in the English language. With the commonality of the business structure of being part of conglomerates and a larger readership, these two media provided a primarily sufficient sample to explore the attitudes of the media toward the government’s foreign policy. However, there is also a limitation in its ability to generalize how the Bangladeshi media as a whole views bilateral relations with the bigger states. The sample data for the analysis consisted of a total of 775 online articles on the relations between Bangladesh and the bigger states such as China, Japan, the US, and India. shows a breakdown of the 775 sample articles, and shows a breakdown by the year in which the article was published.

Table 1. Breakdown of samples.

Table 2. Breakdown of samples by year.

4. Analysis and results

4.1. China

4.1.1. Step 1: frequent words analysis

shows the most frequently used keywords among the top 100 in news articles that particularly represent Bangladesh’s relationship with China. The results show that most of these keywords are related to the economic arena.

Table 3. Frequent words in the top 100 in news coverage on China.

In addition, showsFootnote the frequently used keywords identified only in articles about China. This reveals the characteristics of the media coverage about China which touch upon construction, exports, the debt, and the refugee issues.

Table 4. Frequent words from the top 150 appeared only in articles on China.

4.1.2. Step 2: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

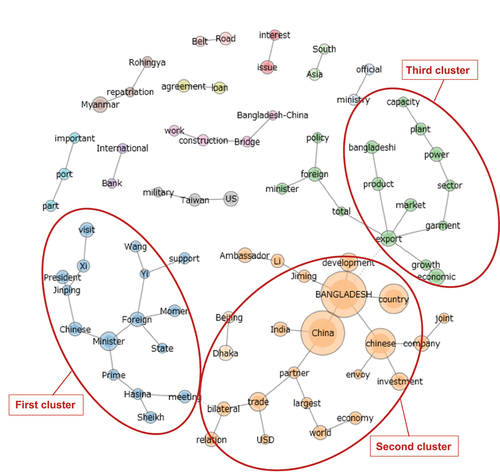

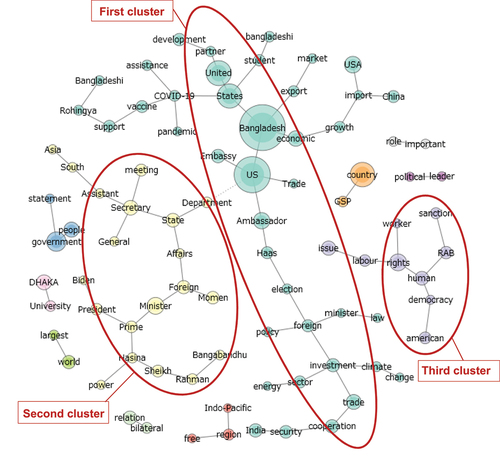

Co-occurrence network analysis was conducted using KH Coder to understand the context in which these keywords are used and how they relate to other words. shows 14 clusters of topics, and the characteristics of media coverage on China are evident in three main ones.

The first cluster is the diplomatic relationship at the summit and ministerial levels. The second cluster is the relationship with China centered on trade and investment for economic development. The third cluster is the economic growth through the export of Bangladeshi products to China. Other topics are also identified such as loan agreements, port development, bridge construction, and the Rohingya issue. The result of this analysis clearly demonstrates that the media frame on China is predominantly related to economic development, and it provides insight into what Bangladesh values most in its bilateral relationship with China, which is investment, promotion of bilateral trade, and increase in exports to China.

4.1.3. Step 3: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

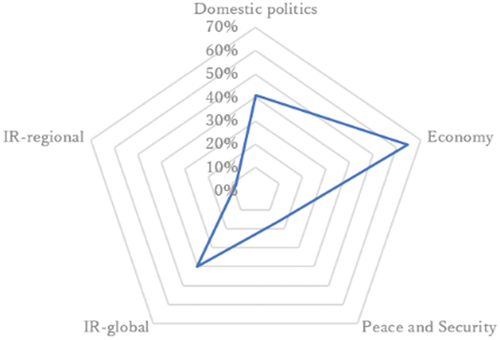

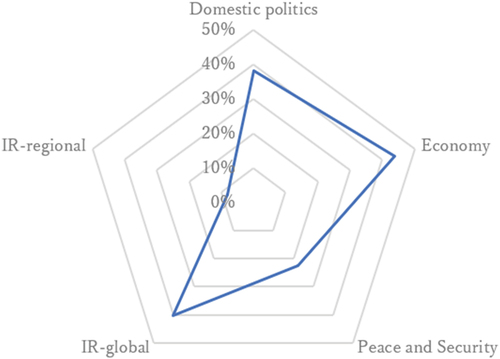

The characteristics of media coverage on bilateral relations with China were examined. A sample of 237 news articles were coded based on the pentagonal analytical framework and shows that the largest number of articles were on economic development, followed by international relations and domestic politics.

Economically, the media identifies that the country’s main expectation is to secure export destinations for its products, thus it is seeking to establish solid trade relations with China. It targets import materials from China, processes them domestically, and reexports them to China. For example, China needs jute, leather, and fishery products from Bangladesh, Bangladesh needs Chinese-supported infrastructure development, including energy supply, and higher export revenues from China.Footnote37 In fiscal year 2021–22, Bangladesh’s total exports were reported at USD 6.0 billion and total imports at USD 8.2 billion, resulting in a trade deficit of USD 2.1 billion. Within this, the trade deficit with China was USD 1.93 billion.

Revealing this gap, the Minister of Commerce, Mr. Tipu Munshi strongly appealed the new progress made during the visit of the former Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi to Bangladesh in September 2022 saying that about 8,930 items (98%) have gained duty-free and quota-free access to the Chinese market, and that the trade deficit would therefore decrease due to increased exports to China.Footnote38 With regard to the garment sector, which is a Bangladeshi leading manufacturing sector, China with an apparel market of USD 350 billion had already allowed 97% of Bangladeshi garments to enter duty-free by July 2020. Though the current Bangladeshi share of exports to the Chinese market remains 0.05%, equivalent to about USD one billion, there is a prospect to grow to $25 billion if Bangladeshi suppliers can gain an additional 1% share.Footnote39 Bangladesh thus keeps its motivation to reduce business costs through the China-supported infrastructure development to strengthen its manufacturing sectors and increase export revenues.Footnote40

Bangladesh’s bilateral economic development cooperation with China is often also reported in the context of geopolitics with the US and India. For essence, in an article published in June 2015, the former UN Ambassador to Geneva, Mr. Harun ur Rashid, praised the Hasina government for building programmatic diplomatic relations with China and India, explaining that maintaining balanced relations with China and India would help accelerate the pace of economic and social development and enhance the country’s regional and global bargaining power.Footnote41 Taking over this perspective, an article in June 2019 asked an interesting question: “Who are the ‘real winners’ in the escalating the US-China trade war?”. It suggested that Bangladesh could emerge as a potential winner from this conflict due to its impact on supply chain dynamics and investment patterns. The unexpected trade war between the US and China has given Bangladesh new opportunities to enable the invitation of more foreign direct investment. To make the most of an opportunity, it asserted the importance of policies which are favorable to the country while avoiding unintended risks.Footnote42

Regarding politics, peace, and security, it is worth highlighting the media shows the way how Bangladesh see China. In August 2015, when China handed over the seventh Bangladesh-China friendship bridge, the Minister of Road Transport and Bridges, Mr. Obaidul Quader called China a “tested friend” in front of the journalists.Footnote43 This phrase implies that Bangladesh is being cautious in the establishment of bilateral relations with China. Why is Bangladesh able to build such a prudent yet proactive relationship with China? Because the country was promised investment from China’s deep pockets for four reasons: (1) Bangladesh’s strategically important geographic location; (2) physical and political proximity to India; (3) availability of cheap labor; and (4) proximity to the Bay of Bengal.Footnote44 In addition, observing the fact that 71% of China’s arms exports were to Pakistan, Myanmar, and Bangladesh between 2011 and 2015, the analysis in the media articles explained that China’s deepening ties with Bangladesh serves two purposes: to generate revenue from arms sales and to restrain India’s geopolitical ambitions in the South Asian region. As a result, Bangladesh has been able to assert itself vis-à-vis China out of the interests that China seeks in the country. There are two prominent examples to support this observation from political statements issued by the Minister and Ministry of Foreign Affairs. One is over QUAD and the other is on Padma bridge.

In May 2021, the Chinese ambassador to Bangladesh criticized Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) as “a military alliance aimed at countering China’s resurgence and relations with its neighbors,” and said Bangladesh should not join QUAD.Footnote45 And again, in June 2022, the Director of the Asian Bureau of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs told Bangladeshi Ambassador to China Mr. Mahbub Uz Zaman that he believed Bangladesh would reject Cold War thinking and bloc politics.Footnote46 In response to the Chinese attempt to pressure Bangladesh to be away from QUAD, The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. A. K Abdul Momen has claimed that as an independent, sovereign nation with a nonaligned foreign policy, Bangladesh decides its own foreign policy.

In June 2022, the Chinese ambassador stated that the Padma Bridge was supported by China as part of the BRI, on the other hand, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an official statement saying, “We affirm that the Padma Multipurpose Bridge is fully funded by the Government of Bangladesh and no foreign funds from bilateral or multilateral funding agencies have financially contributed to its construction.”Footnote47 This assertive position is in line with the statement of the Minister for Foreign Affairs made after the meeting with the Chinese Ambassador on May 2022: “We are very calculating about foreign loans and will not take loans for any project if it does not benefit us.”Footnote48 From these reports, one can see the media’s attitude is to maintain bilateral relations in which China cannot stand superior to Bangladesh.

An article in “Opinion” in June 2022 also said that Bangladesh had succeeded in balancing China and India and must now learn the new game of balancing the US and China. Sharing the common concern of many small countries to keep distance from great power confrontations, the article stated that as a developing country, Bangladesh’s main concerns are not about military agreements or security treaties, but about business, markets, and economy.Footnote49 While Bangladesh’s bilateral relations with China is in a sensitive but dynamic political environment, the Bangladeshi media’s view of China has been one of proactively welcoming its assistance in strengthening export-oriented manufacturing but with deep caution.

4.2. Japan

4.2.1. Step 1: frequent words analysis

below shows the top 100 keywords in news articles about Japan that describe bilateral relations with Japan. Other keywords related to education and technology are identified in addition to economic terms.

Table 5. Frequent words in the top 100 in news coverage on Japan.

Furthermore, shows the keywords extracted as frequent words identified only from articles about Japan. These keywords indicate the specificity of media coverage about Japan, such as the topics of Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), technology, and history.

Table 6. Frequent words from the top 150 appeared only in articles.

4.2.2. Step 2: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

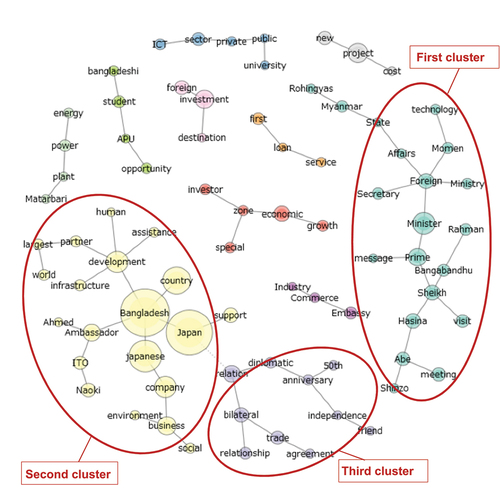

The result of co-occurrence network analysis in shows three major topics among 11 clusters identified from the media coverage in Japan. The first cluster is vigorous diplomatic activity at the summit and ministerial levels. The second cluster is the coverage of diverse bilateral cooperation through aid and business, such as human resource capacity development and assistance in the infrastructure sector, improving the business environment, and interest in social business. The third cluster is about the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations with Japan. Other clusters identified include topics related to Special Economic Zones (SEZs), energy, and education. While these results show that the media frame in Japan is also mainly about economic development, the inclusion of social and historical aspects is distinctive.

4.2.3. Step 3: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

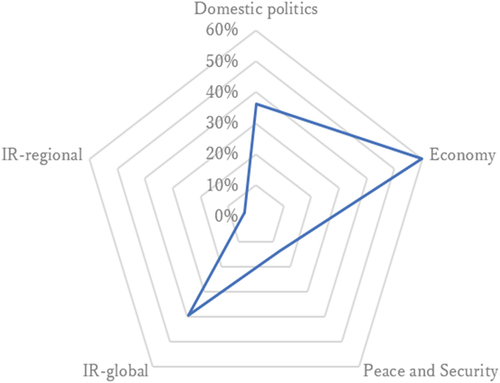

To conduct the qualitative analysis, a sample of 183 news articles were coded and shows that the largest number were on economic development, as in the case of China, followed by international relations and domestic politics. The characteristics of media coverage of economic development with Japan are attributed to historically solid bilateral relations. Of particular significance is the historical fact that the first Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who is regarded today as the Father of the Nation, was committed to the Japanese model of development. Today’s strengthened economic ties between the two countries are an expansion of this historical relationship, which has fostered Bangladesh’s deep trust in Japan.

The visibility of Japanese companies with a strong international brand name is very high in the media coverage of the economy. In November 2018, an article reported on the opening of a motorcycle manufacturing plant by Honda in the Abdul Monem Economic Zone (AMEZ) in Munshiganj.Footnote50 The article emphasized that the country expects the plant to diversify domestic manufacturing, promote exports, expand employment, train skilled workers, facilitate technology transfer, and grow the parts supply industry. About three weeks later there was news that Japan Tobacco Inc, one of the five largest tobacco companies in the world, had acquired the tobacco business of the Akzi Group for $1.47 billion as the largest single foreign direct investment ever made in Bangladesh.Footnote51 This article highlighted the expectation of further investment in supply chain infrastructure.

In May 2019, Mitsubishi Motors Corporation reported its new plan for $100 million investment in Bangladesh,Footnote52 and further stated in September 2021 that the company had signed a MoU with the state-owned Bangladesh Steel Engineering Corporation to conduct a feasibility study for setting up an automobile assembly plant.Footnote53 According to the interview with Mr. Ito, the former Japanese Ambassador to Bangladesh, published in May 2021, the number of Japanese companies operating in Bangladesh had increased from 83 in 2010 to approximately 321 as of April 2021, and that Japanese direct investment in Bangladesh had grown to $397.15 million as of March 2021.Footnote54

In February 2022, a webinar titled “Celebrating 50 Years of Bangladesh-Japan Friendship and Looking Forward to a Prosperous Future” was jointly hosted by the Chittagong Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CCCI), the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) in Dhaka, and the Japan Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce and Industry (JBCCI). The delegates noted that Bangladesh needs continuous cooperation from Japan to become a middle-income country by 2031 and a developed country by 2041, and former Ambassador Mr. Ito expressed Japan’s willingness to play a pivotal role in attracting more private sector investment to help Bangladesh seize its opportunities in the fourth industrial revolution.Footnote55 Four months later, in line with the Bangladesh government’s policy of diversifying defense cooperation, former Ambassador Mr. Ito reported that Japan was also interested in defense equipment supply, and stated that a Japanese private company had visited Dhaka to conduct a study on defense equipment sales, particularly air force radar.Footnote56 This series of economic reports indicates that the development of economic relations between Japan and Bangladesh has been remarkably enhanced in recent years, and that the media has been actively reporting on this process.

The observation made by the former Bangladesh Ambassador to Japan, Ashraf ud Doula, in June 2016 helps to understand the evolution of these strengthening economic ties, while the 2014 visit of former Prime Minister Abe to Bangladesh accompanied by 200 Japanese entrepreneurs also brought a significant impact. Furthermore, the presence of Prime Minister Hasina at the G7 outreach meeting held in Mie Prefecture in 2016, at the invitation of former Prime Minister Abe, was seen as a tailwind to enhance Japan’s engagement with Bangladesh’s development.Footnote57

The core feature of media reports on the economic partnership with Japan is not in the context of political balancing with other bigger states such as China, the US, and India, but as a fruit of the advancement of genuine bilateral relations. Interestingly, many of the articles on JICA’s contributions also report on large-scale infrastructure projects rather than social development. Media coverage in Japan is not presented as a counter to China, but can be read as an indirect appeal to the Bangladesh government’s proactive strategy of balancing China and Japan for economic development. To continue nurturing the existing and trusted bilateral relations, the key is to understand exactly what Bangladesh next expects from Japan and make efforts to provide it. In September 2020, the Minister of Commerce, Mr. Tipu Munshi requested the Japanese government to extend the zero-tariff privilege on exports to Japan for at least another five years after Bangladesh graduates from the LDC status.Footnote58 In this regard, an article in June 2022 reported that the Sub-Committee on Smooth LDC Graduation recommended the signing of trade agreements with seven major trading partners including China, India, Japan and Russia, but only China and India have expressed interest.Footnote59 This article emphasized the importance and necessity for Japanese investment, while acknowledging that Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs), and Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs) are not only subject to economic, but also political and strategic factors. Japan will have to make a sound decision on how to respond to Bangladesh’s trust in Japan by carefully observing and analyzing the way China and India meet Bangladesh’s demands.

This special position that Japan benefits from can be evidenced from the political perspective as well. For example, the comment of the Minister of Information and Broadcasting Mr. Hasan Mahmud in February 2022 features the contrast between Japan and China: Japan had a “remained a trusted friend” of Bangladesh in its socio-economic development for the last 50 years while China has been called as a “tested friend.” Prime Minister Hasina’s statements also sent a strong message about her trust in Japan. During her visit in May 2014, she announced that Bangladesh would withdraw its candidacy for the 2015 UN Security Council elections if Japan stood for election. She emphasized that “Bangladesh is ready to make any sacrifice for the sake of our trusted friends.Footnote60” Furthermore, in May 2019, Prime Minister Hasina said that Japan holds a very special place in the hearts of the people of Bangladesh and the level of commitment that Japan has shown since independence is truly remarkable.Footnote61 And this emotional bonding is largely attributed to historical experience and memory.

In June 2016, former Bangladesh’s Ambassador to Japan Ashraf ud Doula shared his personal experience in an article: the Emperor of Japan had great admiration and respect for Bangabandhu, the first Prime Minister, and fondly recalled his visit to Bangladesh in 1974 and his interaction with the “Father of the Nation.Footnote62” He also stated that that father of the nation modeled the development of Bangladesh on Japan’s experience. It is apparent that such media comments may have the positive effect of deepening the emotional bond that the country’s leaders have, among the general public, and spreading favorable perceptions of Japan downstream as well.

4.3. The US

4.3.1. Step 1: frequent word analysis

shows the most frequently used keywords in news articles about China from the top 100 that demonstrate the relationship with the US. While key economic terms are observed, various characteristic keywords related to such environments as politics, education and social welfare are also identified.

Table 7. Frequent words in the top 100 in news coverage on the US.

lists the extracted frequent words identified only in articles on the US. These terms provide an overview of the media coverage of the US within the specificity of human rights and political issues.

Table 8. Frequent words from the top 150 appeared only in articles on the US.

4.3.2. Step 2: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

As shown in , 11 clusters of topics are identified in media articles about the US, and there are three main topics to focus on. The first cluster is about US development cooperation, which targets not only economic development, but also the areas of COIVD-19 vaccine assistance, Rohingya issues, climate change, and security cooperation. An important aspect of this cluster is the inclusion of the topic of elections. The second cluster is diplomatic relations between the Hasina and Biden administrations. The third cluster is the diplomatic strategy of the US based on human rights values. The main media frame for the US relationship is also about economic development, however, the inclusion of topics on politics is a preeminent feature of the media coverage of the US.

4.3.3. Step 3: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

For the next step of qualitative analysis, 134 news articles were coded, and shows that the largest number of articles were on economic development similar to China and Japan. Nevertheless, the important feature of the media coverage of the US relationship are the additional factors of international relations and peace and security. In addition, closely equal volume of articles on domestic politics and economics was also observed.

Economic activity with the US is tied to human rights and political issues and the Tazreen Fashion Building fire and the Rana Plaza building collapse in April 2013 had a very significant impact on this matter. While Bangladesh had previously been eligible for the GSP status in trade with the US, this was suspended in June 2013 when the incident occurred due to the revelation of serious shortcomings in worker rights. As a result of the suspension of GSP status, while Bangladesh exported more than $5.58 billion in goods to the US, 95% of this was apparel subject to a 15.61% tariff between FY2013 and FY2014.Footnote63

In August 2015, the Minister of Commerce, Mr. Tofail Ahmed said that the US exclusion of Bangladesh from the 122 GSP countries was politically motivated.Footnote64 As recapturing GSP status is essential for Bangladesh’s economic growth, he insisted that the government of Bangladesh should take the necessary steps to change this situation. However, despite the suspension of GSP status Bangladesh has been pursuing the opportunity to gain from the tariff war between China and the US.Footnote65 One example is the cotton trade. Vietnam was the top source of US cotton imports, followed by China, but the trade embargoes have forced the US to shift its marketing focus to Bangladesh. In fact, Cotton USA opened an office in Dhaka to strengthen its marketing efforts and hired technicians to educate the public on the use and trade of cotton.Footnote66 Nevertheless, Bangladesh’s trade-based economic relationship with the US is strongly influenced by two factors: the human rights issue and the US-China trade war.

For the aspect of peace and security, the sanctions imposed on RAB in 2021 remain a key factor in the management of the bilateral relations with the US. For example, one Non-Governmental Organization in the US published the report to criticize the human rights violation in Bangladesh. It said that RAB and other Bangladeshi law enforcement agencies have engaged in more than 600 disappearances since 2009 and nearly 600 extrajudicial executions and cases of torture since 2018 that targeted opposition lawmakers, journalists, and human rights activists. The US condemns this undermining the rule of law and respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms, and national economic prosperity and threatening the country’s national security interests.Footnote67 In response to this, an article on 14 April 2022 quotes a critical statement by the Minister of Information and Broadcasting Mr. Hasan Mahmood that the sources of the report on human rights in Bangladesh are one-sided.Footnote68 Another article on 24 April quoted the comment of the US Ambassador to Bangladesh saying that there is no room to repeal sanctions against RAB without concrete action and accountability, and the US values the ability of the people of Bangladesh to choose their government, not elect one over the other.Footnote69 The Minster of Foreign Affairs Mr. Momen responded that Bangladesh would improve the situation if it can be shown where the gaps are. However, the next day, Foreign Minister Momen also told local journalists to ask the US ambassador why the US had not stopped the extrajudicial killings of Black and Hispanic citizens in his own country.Footnote70 This implies frustration with the RAB sanction as a contradiction by the US. During the visit of the US Assistant Secretary, Mr. Lu to Bangladesh in January 2023, the Foreign Minister, Mr. Momen again requested the lifting of sanctions and restoring the GSP status of Bangladesh, however no concrete response was suggested from the US side.Footnote71

The signing of the GSOMIA (General Security of Military Information Agreement) and ACSA (Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement) agreements to modernize the Bangladesh Armed Forces in response to the Armed Forces Goals 2030 formulated in 2009, also attracted media attention in terms of peace and security.Footnote72 GSOMIA sets the ground rules for the exchange of sensitive data on military operations and ACSA allows the exchange of fuel and food. It is different from “broad and vague defense agreements” such as the ““China-Bangladesh Defense Cooperation Agreement” signed with China in 2002 for military training and defense production. Foreign Secretary Mr. Masud expressed the Bangladeshi intentions to diversify the source of defense related materials,Footnote73 and the media argues the government’s policy to balance the China- US tensions in the country by purchasing arms from China while establishing the gateway of further military cooperation with the US.Footnote74

The media coverage on the US includes an argument of domestic politics that goes into the confrontation with the opposition party and a rebuttal to the US criticism of Bangladesh’s limited political freedoms. An article in July 2022 countered the criticism by the US State Department human rights report. The report strongly condemned that Bangladeshi opposition politicians, including the country’s largest Islamist party, have faced criminal confessions, been harassed by law enforcement, and been unable to exercise their freedom of speech and assembly, as well as the deregistration of the Jamaat as a political party and the ban on holding office in the name of the Jamaat-i-Islami. Criticizing Jamaat as an organization that sided with the Pakistani military in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War and committed war crimes, the article refutes the US report’s defense of Jamaat as evidence of a remarkable continuity in US policy in support of pro-Pakistan forces in Bangladesh.Footnote75

The above stories outline factors of economic development, domestic politics, peace and security, and international relations on how Bangladesh views the US, as the Minister of Foreign Minister, Mr. Momen called the US “a constructive partner in a positive manner.”Footnote76 The media argues that the status of partnership with the US has not developed as Bangladesh expected given the political friction over domestic politics and human rights issues, nevertheless Bangladesh needs the US as an export destination and a means of counterbalancing defense cooperation with China.

4.4. India

4.4.1. Step 1: frequent words analysis

is a list of the most frequently used keywords in news articles about India from the top 100 that are particularly important for understanding the bilateral relations between two countries. In addition to economic terms, other keywords related to regional matters, connectivity, and land are identified.

Table 9. Frequent words in the top 100 in news coverage on India.

shows the extracted frequent keywords identified only in articles about India. These keywords are used to characterize the media coverage about India such as on the topics of border, connectivity, rivers, and water.

Table 10. Frequent words from the top 150 appeared only in articles on India.

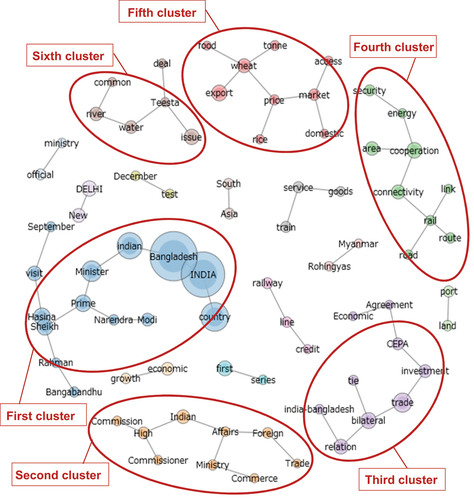

4.4.2. Step 2: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

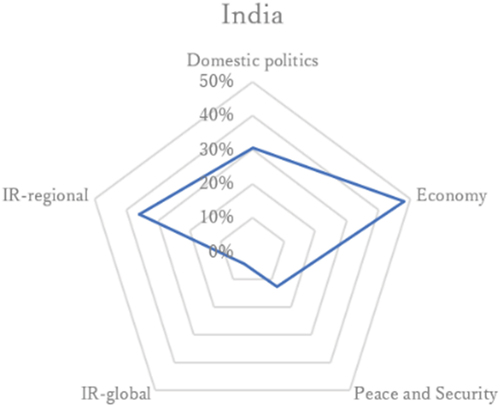

shows the result of 16 clusters identified from the media coverage on India, with six main topics to focus on. The first cluster is the invigorated high-level diplomacy between Prime Minister Hasina and Prime Minister Modi. The second cluster is ministerial-level trade negotiations. The third cluster is investment and trade, centered on CEPA, the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement. The fourth cluster is on issues of cooperation for enhanced connectivity, energy, and security, and the fifth cluster is on imports and exports of grains such as wheat and rice between the two countries. The sixth cluster is on river and water issues, including the sharing of the Teesta River. In addition, there are clusters on ports, railways, economic growth, and the Rohingya issue. As with the result of co-occurrence network analysis of other bigger countries, economic development could be identified as the main media frame, however, other issues such as connectivity, rivers, and food significantly shape the future of media coverage of India.

4.4.3. Step 3: media framing based on the co-occurrence network analysis

To conduct the next step of qualitative analysis, 221 news articles were coded. demonstrates that the largest number of articles were on economic development, however unlike the case of China, Japan, and the US, regional International Relations has a larger significance on the media coverage of India.

The relationship between the two countries has evolved over the past 50 years as Bangladesh has continued to grow economically and India has increased its presence as a regional power. Based on India’s contribution during Bangladesh’s independence, the relationship between the two countries has been likened to that of brotherhood, with India as the elder brother and Bangladesh as the younger. In recent years, however, Bangladesh has been advocating a more equal partner status with India. The article in May 2015 reported that India had passed a constitutional amendment to ratify the 41-year-old Land Boundary Agreement (LBA) and quoted the Indian foreign minister’s statement: India would maintain the attitude of a compassionate brother, not an arrogant one, toward its neighbors.Footnote77 The media analyzed this as an implication of the Modi government’s new foreign policy, which seeks to build good relations with its neighbors while aiming to establish itself as a regional power and participate in global great power politics. In contrast, Bangladesh does not need a powerful “big” brother or a gentle “elder” brother, but needs “equal friends” from its neighbors, confirming Bangladesh’s desire to build an equal partnership with India.Footnote78 To become good neighbors, the media presents the fact that Bangladesh realized the inevitability of overcoming perennial problems with India: issues of border security and the sharing of rivers and water.

The border management question has been seriously important matter for both countries, which have 4,096 km of border and 71 Bangladeshi enclaves in India and 102 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh. In July 2019, the Minister of Home Affairs, Mr. Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal reported the parliament that 294 Bangladeshis have been killed along the border in the last 10 years due to the “shoot on sight” policy of the Indian Border Security Force (BSF). He was referring to the incident of “Border Shooting of Felani Khatun” in 2011 in which her body was left hanging on barbed wire on Bangladesh-India border after shot by BSF to warn local people.Footnote79 An article in January 2020 quoted a report of the Human Rights Watch, “Happy Trigger,” citing claims by survivors and witnesses that the BSF fired indiscriminately without warning. While India asked that the BSF’s shooting of Bangladeshis on sight be reworded as “unintentional deaths rather than killings,” an Indian politician called illegal immigrants from Bangladesh “termites” in October 2020.Footnote80 And to date, the issue of killings and injuries along the border is reported every month. This is one of the key issues to be resolved at the level of political leaders to build a good bilateral relationship, as it is also tarnishing the impression of India among Bangladeshis.Footnote81

The issue of water sharing is another serious challenge that the media promotes as important to resolve. In December 2010, an MoU was signed by the Water Resources Secretaries of India and Bangladesh but was not signed by their respective ministers due to obstruction by the West Bengal state government. Since then, skepticism about India’s intentions has prevailed in Bangladesh. In August 2022, the first meeting of the Joint Rivers Commission (JRC) in 12 years was held and a water sharing agreement for the Teesta River was prepared. Although the signing of the agreement was delayed due to opposition from the Chief Minister of West Bengal, the Indian Minister of Water Resources asserted that the central government would put pressure on the state government to find a solution. In fact, the JRC meeting discussed several ongoing bilateral issues including sharing water in common rivers, sharing flood data, addressing river pollution, conducting joint studies on sediment management, and riverbank protection works. From these efforts at the ministerial level, the strong political will of both governments to rebuild trust is growing.Footnote82

Why are both governments now vigorously trying to resolve such long-standing issues? The statement of Prime Minister Hasina on 10 March 2021 at the inauguration of the Friendship Bridge between two countries gives us an idea, saying that political boundaries should not be a physical barrier to trade in the region.Footnote83 On the same occasion, Prime Minister Modi said that connectivity will not only strengthen the friendship between India and Bangladesh but will also become a strong business link. Moreover, Prime Minister Hasina referred to the history of independence to explain not only economically but also politically signify to strengthen the connectivity with India noting that India opened its borders in 1971 to support the people of Bangladesh in their struggle for freedom. She regarded this as a testament to the Bangladesh government’s continued commitment to assist India in strengthening connectivity in northeastern India. Bangladesh complied with India’s request for free passage of Indian goods, did not ask India to pay for the increased maintenance costs to Bangladesh that would result from granting this facility to India, allowed India to “use Bangladeshi ports, and to install radar for coastal surveillance systems,” “take water from the Feni River,” and played an important role in supporting India’s counterinsurgency activities in the northeast. Why is Bangladesh willing to do this for India? The media argue that the motivation is nothing more than its own strategy to make the most of its geographical advantages aiming at the functional probability of a strong economic link between South Asia and Southeast Asia. To achieve this, the first task set for itself is to become a reliable neighbor to India.

Bangladesh has had a long history of complex issues with India, which have remained unresolved over the years. However, Bangladesh’s economic strategy to become a trade and a transit hub in the South Asian region and India’s shared national interests there have sparked a political drive to rapidly improve bilateral relations. The media has been positive, indicating a growing political will to resolve these traditional issues that have aggravated relations between the two countries by working together to further stimulate economic development.

5. Discussion

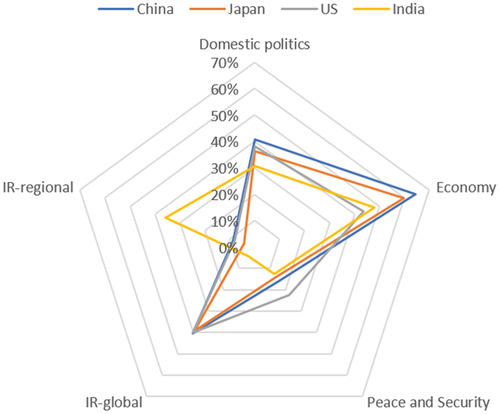

There are two findings from the comparison of Bangladesh’s media coverage of China, Japan, the US, and India. The most weight in the media coverage is about economics as indicates, and the most commonly used keywords in the media stories are investment, infrastructure, manufacture, and exports as shown in . This is aligned with national policies such as the Export Policy 2018–21, which encourages foreign investment in export-oriented industrial sectors to increase trade. This policy prioritizes mega projects for infrastructure development to reduce export lead times and build the necessary physical infrastructure such as electricity, gas, and water for all export-oriented industries (GoB 2018).

Table 11. Common high frequency words in news coverage on all four countries.

Furthermore, the content of the media coverage on each of the bigger states had the following characteristics. In relations with China, the media argues that the primary objective is to extract resources for economic development by proactively using China-India competition and the US-China confrontation to understand the national interests have in seeking a relationship with Bangladesh. At the same, the attitude of media tends to be cautious toward any approach in which China tries to gain the upper hand. In contrast, the media storied the relationship with Japan as rooted in the historically formed emotional ties with trust rather than political calculations. The media’s expectation toward Japan observed in the coverage was more genuine about strengthening economic development without political maneuvering. In other words, one could argue that having Japan as a guaranteed partner enables Bangladesh to negotiate proactively with other bigger states such as China, the US, and India.

Regarding relations with the US, the media explain the outstanding political issues that need to be overcome for the expansion of more windows of economic opportunities, in particular to access the US market. In negotiations with the US on restoring GSP status and economic sanctions for the past few years, Bangladesh is carefully balancing the political and economic aspects of its bilateral relations to the extent to which the values of freedom and human rights can prevail in its domestic society. In its relations with India, the media has revealed how various security issues have been a hindrance to mutual economic development, and has proactively appealed that those traditional issues, which have dragged the two countries down, have never been more important.

Based on the discussion above, the messages that the Bangladeshi media try to insist upon are observable along the pentagonal factors; first, for domestic politics, no one country is to be given an advantage over the other, but rather they should be equal partners, as dependence on any one country will be subject to criticism against the government; second, Bangladesh is practicing the traditional all-weather-friend diplomacy it has upheld since independence to seek peace and security; third, on the upswing, Bangladesh’s status is improving in today’s international relations; fourth, actively seeks to build good relations with neighboring regional powers that may pose a threat; and fifth, the current administration is achieving significant economic development from investment, infrastructure, manufacture, and exports.

However, this study has limitations using only the Daily Star and the Daily Sun as samples in Bangladesh which is considered a quasi-democracy with limited media freedom. Since both media are under the umbrella of traditional business conglomerates with connection to the governmentFootnote84, there is unlikely to be significant divergence between the content of their coverage and what the government intends to propagate. As a result, coverage of relations with bigger states tends to focus on economic development, resulting in a large discrepancy with the amount of coverage of domestic politics. It may reflect the reality of the limited media environment and muffled political debate regarding foreign policy toward bigger states which could be attributed to the unique media business structure in the country. Broadening the scope of the study by diversifying the sample, further research is needed to explore not only the extent of media freedom in Bangladesh, but also how media coverage and government policies reflect or challenge each other and why?

6. Conclusion

The results of the Bangladeshi media analysis of the relationship with the four bigger states provide five important perspectives to understand the smaller states’ policies toward the bigger states: first, the historical facts of the relationships in which bigger states took what actions at the time of independence of a smaller state are vividly etched in the memory of the smaller state and serve as the basis for bilateral relations with the bigger state to the present day; second, when a founding leader of the country plays an important role in shaping national identity, the leader’s perception of a bigger state can easily be used by the regime of the day to legitimize its own foreign policy; third, construction projects have a political importance that goes beyond just infrastructure development and highly reflects the pride and calculations of a smaller state; fourth, the stability of a smaller state’s political and economic foundation depends largely on how it strategically views neighboring regional powers as threats, rivals, or partners; and fifth, the most important bigger state for small countries as a partner is that one that provides essential cooperation for the national goals they set by themselves, that are not instructed or imposed by others, and are eagerly aspired to.

Media coverage is not about reporting or evaluating the facts but is littered with the Bangladeshi expectations toward the bigger states, and the ambitions, strategies, and calculations as a smaller state in not being swallowed by the politics of bigger states. In other words, the content of the smaller state’s media coverage on bigger states can be valuable as puzzle pieces to read the potential political will that small countries could proactively exert over bigger states. Bilateral relations between smaller and bigger countries will continue to deepen with the continuous dynamic changes in the international community. The relationship between smaller and bigger states is no longer fixed, but in flux. What does the media of small countries say about bigger states? The importance of deepening the debate on this point should be emphasized for a more strategic and rational understanding of the smaller states and for effective policy making toward them. Otherwise, a bigger state could be used in a balancing game cleverly led by a smaller state, resulting in a loss of presence and influence in the country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Natsuko Imai

Natsuko Imai Research Officer of JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development. She has worked for the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability to coordinate the global leadership training program in Africa, and the United Nations Development Program in Sierra Leone and Afghanistan for peacebuilding as Programme Manager and Head of Unit, and NGOs for humanitarian relief and refugee protection in Indonesia and Uganda as Project Director. Academically, she has researched the role of civil society and grassroots actors on the ground in conflict prevention and peace processes.

Notes

1 The term “smaller state” used in this paper refers to a “smaller or lesser power” that stands in an asymmetrical position in terms of national power in relation to a “big power” in international politics.

2 DiMaggio et. al., “Social implications of the Internet;” Grant, “China’s media expansion in Zambia: Influence on government, commercial, community, and religious media;” Westcott, “Digital diplomacy: The impact of the internet on international relations;” Neuman et al., “The dynamics of public attention: Agenda-setting theory meets big data;” Adesina, “Foreign policy in an era of digital diplomacy.”

3 World Bank, Individuals using the Internet (% of population) – Bangladesh | Data. The ratio of internet users has rapidly increased from 0% in 2005 to 25% in 2020. A sharp increase is observable since 2013.

4 Udupa, Media as politics in South Asia; Al-Zaman, “Digital media and political communication in Bangladesh;” CGS, Who owns the media in Bangladesh?

5 Ahmed, “Media, politics and the emergence of democracy in Bangladesh;” Al-Zaman, “Digital media and political communication in Bangladesh.”

6 McQuail,“The influence and effects of mass media.”

7 Bryant and Olivier, Media effects: Advances in theory and research; Valkenburg et al., “Media effects: Theory and research;” McQuail and Deuze, McQuail’s media and mass communication theory.

8 Couldry, “Theorising media as practice.”

9 Schramm, Mass media and national development: The role of information in the developing countries; Wasserman, Popular media, democracy and development in Africa; Adegoke, “Africa and the Media..”

10 Ochilo, “Press freedom and the role of the media in Kenya;” Phiri, “Media in ‘democratic’ Zambia: Problems and prospects;” Ahmed, “Media, politics and the emergence of democracy in Bangladesh;” PiMA, Background paper: Politics and interactive media in Zambia; Arora, “Bottom of the data pyramid: Big data and the global south..”

11 Wekesa et al., “Introduction to the special issue: Digital diplomacy in Africa;” Intentilia et al., “Utilizing digital platforms for diplomacy in ASEAN: A preliminary overview;” Garud-Patkar, “Is digital diplomacy an effective foreign policy tool? Evaluating India’s digital diplomacy through agenda-building in South Asia.”

12 Kuik, “The essence of hedging: Malaysia and Singapore’s response to a rising China;” “Asymmetry and authority: Theorizing Southeast Asian responses to China’s Belt and Road Initiative;” “Getting hedging right: a small-state perspective.”

13 Montiel et al., “Nationalism in local media during international conflict: Text mining domestic news reports of the China – Philippines maritime dispute;” “Narrative congruence between populist President Duterte and the Filipino public: Shifting global alliances from the United States to China.”

14 Ciborek, “The People’s Republic of China as a ‘pillar’ in the foreign policy of the Republic of Serbia during COVID-19 pandemic;” Styczyńska, “Who are Belgrade’s most desired allies?.”

15 Gondwe, “China’s media expansion in Zambia: Influence on government, commercial, community, and religious media;” Chimbelu, “Status complicated: In Zambia, China-Africa is a partnership Washington should not necessarily envy.”

16 Wu, “China’s media and public diplomacy approach in Africa: Illustrations from South Africa;” Munoriyarwa, “Is this not colonization? Framing Sino-South African relations in South Africa’s mainstream press.”

17 Akanda, “Ideational meaning: Media representations of Sino-Bangladesh relation and its actors;” “Ideology and power in the headlines: A critical discourse analysis of Bangladesh-China relations;” Nominalizations: Application of grammatical metaphor in the news articles of Bangladesh-China relations.

18 Higuchi, A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis using Anne of Green Gables, Part I.

19 Entman, “Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm;” Cappella and Jamieson, Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good.

20 Chong and Druckman, “Framing theory;” Entman, “Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power.”

21 Neuman et al., Common knowledge: News and the construction of political meaning.

22 United Nations. Graduation of Bangladesh, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Nepal from the least developed country category.

23 Yunus, “The garment industry in Bangladesh;” Alam et al., “Determinants of the Bangladesh garment exports in the post-MFA environment.”

24 Rahman, “Development, democracy and the NGO sector: Theory and evidence from Bangladesh;” Islam, “The toxic politics of Bangladesh: A bipolar competitive neopatrimonial state?;” Mostofa and Subedi, “Rise of competitive authoritarianism in Bangladesh;” Riaz, “The pathway of democratic backsliding in Bangladesh.”

25 Rahman, “Freedom of speech & expression in Bangladesh in the context of the ICT Act 2006;” Hasan, “Digital Security Act 2018: From the lens of investigative journalism and freedom of expression..”

26 Pattanaik, “Engaging the Asian giants: India, China and Bangladesh’s crucial balancing act;” Chakma, “The BRI and Sino-Indian geo-economic competition in Bangladesh: Coping strategy of a small state;” Yasmin, “India and China in South Asia: Bangladesh’s opportunities and challenges;” Pal, “China’s influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and resilience in four countries.”

27 Genilo et al., “Small circulation, big impact: English language newspaper readability in Bangladesh.”

28 CGS, Who owns the media in Bangladesh?

29 Riaz, “Bangladesh: From an electoral democracy to a hybrid regime (1991–2018);” Riaz and Parvez, “Anatomy of a rigged election in a hybrid regime: the lessons from Bangladesh;” Jackman and Maitrot, “The Party-Police nexus in Bangladesh..”

30 Freedom House, Bangladesh: Freedom on the Net 2022 Country Report. According to the international ranking published by Freedom House, the status of media freedom in Bangladesh is party free. While social media is not blocked, network restriction and website blockage exist and commentors are pro-government.

31 World Bank, Press Freedom Index – GovData360. According to the index published by the World Bank since 2002, the index, which was rated at 62.5 at its highest point in 2004, has continued to decline since 2012.

32 Ahmed, “Media, politics and the emergence of democracy in Bangladesh.”

33 Price, The enabling environment for free and independent media: Contribution to transparent and accountable governance. “The historicity of media regulation in Zambia;” Ndawana et al., “Examining the proposed statutory self-regulation..”

34 Genilo et al., “Small circulation, big impact: English language newspaper readability in Bangladesh;” CGS, Who owns the media in Bangladesh?

35 Articles were collected from each media’s internal search engine using the keywords of China, Japan, USA, India and Bangladesh. The number of samples collected is the result of an automated search.

36 Note that for articles published before 2012, two were available in 2003 and 2010 for Japan, one in 2004 and two in 2010 for the US, and one was published in 2011 for India.

37 The Daily Star, October 17, 2016.

38 September 1, 2022.

39 February 23, 2022.

40 See the paper by Yasmin in this special issue for the details of Chinese funded infrastructure projects in Bangladesh.

41 May 26, 2015.

42 The Daily Star, June 19, 2019.

43 August 26, 2015.

44 The Daily Star, April 21, 2017.

45 May 10, 2021.

46 June 2, 2022.

47 June 18, 2022.

48 May 11, 2022.

49 June 2, 2022.

50 November 12, 2018.

51 November 30, 2018.

52 May 17, 2019.

53 September 2, 2021.

54 May 12, 2021.

55 The Daily Star, February 16, 2022.

56 June 8, 2022.

57 June 1, 2016.

58 September 3, 2020.

59 June 6, 2022.

60 July 5, 2014.

61 May 30, 2019.

62 June 1, 2016.

63 August 11, 2015.

64 The Daily Star, August 13, 2015.

65 October 24, 2019.

66 August 17, 2015.

67 December 11, 2021.

68 April 14, 2022.

69 April 24, 2022.

70 The Daily Star, June 1, 2022.

71 Daily Sun, January 15, 2023.

72 October 18, 2019.

73 Daily Sun, April 12, 2022.

74 April 8, 2022.

75 July 15, 2022.

76 Daily Sun, January 9, 2023.

77 The Daily Star, May 11, 2015.

78 May 28, 2015.

79 December 31, 2021.

80 October 27, 2020.

81 November 26, 2019.

82 August 25, 2022.

83 March 10, 2021.

84 CGS. Who Owns the Media in Bangladesh?.

Bibliography

- Adegoke, D. “Africa and the Media.” In The Development of Africa: Issues, Diagnoses and Prognoses, edited by O. A. Adésìnà and J. Olálékan, 173–188. Berlin: Springer, 2018. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-66242-8.

- Adesina, O. S., and J. Summers. “Foreign Policy in an Era of Digital Diplomacy.” Cogent Social Sciences 3, no. 1 (2017): 1297175. doi:10.1080/23311886.2017.1297175.

- Ahmed, A. M. “Media, Politics and the Emergence of Democracy in Bangladesh.” Canadian Journal of Media Studies 5, no. 1 (2009): 50–69.

- Akanda, M. A. R. “Ideational Meaning: Media Representations of Sino-Bangladesh Relation and Its Actors.” Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics 52 (2019). doi:10.7176/JLLL/52-11.

- Akanda, M. A. R. “Ideology and Power in the Headlines: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Bangladesh-China Relations.” Global Journal of Human Social Science: G Linguistics & Education 20, no. 7 (2020): 9–26.

- Akanda, M. A. R. Nominalizations: Application of Grammatical Metaphor in the News Articles of Bangladesh-China Relations. 2021. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-161178/v1.

- Alam, M. S., E. A. Selvanathan, and S. Selvanathan. “Determinants of the Bangladesh Garment Exports in the Post-MFA Environment.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 22, no. 2 (2017): 330–352. doi:10.1080/13547860.2017.1292768.

- Al-Zaman, S. “Digital media and political communication in Bangladesh.” Artha Journal of Social Sciences 19, no. 2 (2020): 1–19. doi:10.12724/ajss.53.1.

- Arora, P. “Bottom of the Data Pyramid: Big Data and the Global South.” International Journal of Communication 10 (2016): 19.

- Bryant, J., and M. B. Oliver, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. New York: Routledge, 2009.

- Cappella, J. N., and K. H. Jamieson. Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- CGS. Who Owns the Media in Bangladesh?. Dhaka: Centre for Governance Studies, 2021.

- Chakma, B. “The BRI and Sino-Indian Geo-Economic Competition in Bangladesh: Coping Strategy of a Small State.” Strategic Analysis 43, no. 3 (2019): 227–239. doi:10.1080/09700161.2019.1599567.

- Chimbelu, C. “Status Complicated: In Zambia, China-Africa is a Partnership Washington Should Not Necessarily Envy.” Asia Policy 17, no. 3 (2022): 61–69. doi:10.1353/asp.2022.0048.

- Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10, no. 1 (2007): 103–126. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054.

- Ciborek, P. “The People’s Republic of China as a ‘Pillar’in the Foreign Policy of the Republic of Serbia During COVID-19 Pandemic.” Politeja-Pismo Wydziału Studiów Międzynarodowych i Politycznych Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego 18, no. 7 (2021): 145–169. doi:10.12797/Politeja.18.2021.73.08.

- Couldry, N. “Theorising Media as Practice.” Social Semiotics 14, no. 2 (2004): 115–132. doi:10.1080/1035033042000238295.

- DiMaggio, P., E. Hargittai, W. R. Neuman, and J. P. Robinson. “Social Implications of the Internet.” Annual Review of Sociology 27, no. 1 (2001): 307–336. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.307.

- Entman, R. M. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43, no. 4 (1993): 1–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Entman, R. M. “Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power.” Journal of Communication 57, no. 1 (2007): 163–173. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x.

- Garud-Patkar, N. “Is Digital Diplomacy an Effective Foreign Policy Tool? Evaluating India’s Digital Diplomacy Through Agenda-Building in South Asia.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 18, no. 2 (2022): 128–143. doi:10.1057/s41254-021-00199-2.

- Genilo, J. W., M. Asiuzzaman, and M. M. H. Osmani. “Small circulation, big impact: English language newspaper readability in Bangladesh.” Advances in Journalism and Communication 4, no. 4 (2016): 127–148. doi:10.4236/ajc.2016.44012.

- Gondwe, G. “China’s Media Expansion in Zambia: Influence on Government, Commercial, Community, and Religious Media.” Journalism and Media 3, no. 4 (2022): 784–793. doi:10.3390/journalmedia3040052.

- Government of Bangladesh. National Export Policy 2018-2021. Dhaka: GoB, 2012.

- Grant, R. The Democratisation of Diplomacy: Negotiating with the Internet. Oxford Internet Institute Research Report No. 5, 2004. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1325241.

- Hasan, A. R. “Digital Security Act 2018: From the Lens of Investigative Journalism and Freedom of Expression.” Perspectives in Social Science 17 (2023). doi:10.59146/PSSV170110.59146/PSSV1701.

- Higuchi, K. “A Two-Step Approach to Quantitative Content Analysis: KH Coder Tutorial Using Anne of Green Gables (Part I).” Ritsumeikan Social Science Review 52, no. 3 (2016): 77–91.

- Intentilia, A. A. M., P. E. Haes, and G. Suardana. “Utilizing digital platforms for diplomacy in ASEAN: A preliminary overview.” COMMUSTY Journal of Communication Studies and Society 1, no. 1 (2022): 1–7. doi:10.38043/commusty.v1i1.3685.

- Islam, M. M. “The Toxic Politics of Bangladesh: A Bipolar Competitive Neopatrimonial State?” Asian Journal of Political Science 21, no. 2 (2013): 48–168. doi:10.1080/02185377.2013.823799.

- Jackman, D., and M. Maitrot. “The Party-Police Nexus in Bangladesh.” The Journal of Development Studies 58, no. 8 (2022): 1516–1530. doi:10.1080/00220388.2022.2055463.

- Kuik, C. C. “The Essence of Hedging: Malaysia and Singapore’s Response to a Rising China.” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 30, no. 2 (2008): 159–185. doi:10.1355/CS30-2A.

- Kuik, C. C. “Asymmetry and Authority: Theorizing Southeast Asian Responses to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Asian Perspective 2, no. 2 (2021): 255–276. doi:10.1353/apr.2021.0000.

- Kuik, C. C. “Getting Hedging Right: A Small-State Perspective.” China International Strategy Review 3, no. 2 (2021): 300–315. doi:10.1007/s42533-021-00089-5.

- McQuail, D. “The Influence and Effects of Mass Media.”In Mass Communication and Society, edited. by J. Curran, M. Gurevitch, and J. Woollacott, SAGE Publication Inc. London, UK. p.7–23. (1977).

- McQuail, D., and M. Deuze, eds. McQuail’s Media and Mass Communication Theory. 2020. London UK: SAGE Publications Int.

- Montiel, C. J., A. J. Boller, J. Uyheng, and E. A. Espina. “Narrative Congruence Between Populist President Duterte and the Filipino Public: Shifting Global Alliances from the United States to China.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 29, no. 6 (2019): 520–534. doi:10.1002/casp.2411.

- Montiel, C. J., A. M. O. Salvador, D. C. See, and M. M. De Leon. “Nationalism in Local Media During International Conflict: Text Mining Domestic News Reports of the China–Philippines Maritime Dispute.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 33, no. 5 (2014): 445–464. doi:10.1177/0261927X14542435.

- Mostofa, S. M., and D. B. Subedi. “Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism in Bangladesh.” Politics and Religion 14, no. 3 (2021): 431–459. doi:10.1017/S1755048320000401.

- Munoriyarwa, A., and A. Chibuwe. “Is This Not Colonization? Framing Sino-South African Relations in South Africa’s Mainstream Press.” Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa 41, no. 1 (2022): 11–24. doi:10.36615/jcsa.v41i1.1392.

- Ndawana, Y., J. Knowles, and C. Vaughan. “The Historicity of Media Regulation in Zambia; Examining the Proposed Statutory Self-Regulation.” African Journalism Studies 42, no. 2 (2021): 59–76. doi:10.1080/23743670.2021.1939749.

- Neuman, R. W., L. Guggenheim, S. A. Mo Jang, and S. Y. Bae. “The Dynamics of Public Attention: Agenda-Setting Theory Meets Big Data.” Journal of Communication 64, no. 2 (2014): 193–214. doi:10.1111/jcom.12088.

- Neuman, W. R., M. R. Just, and A. N. Crigler. Common Knowledge: News and the Construction of Political Meaning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Ochilo, P. J. O. “Press Freedom and the Role of the Media in Kenya.” Africa Media Review 7, no. 3 (1993): 19–33.

- Pal, D. “China’s Influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries.” In China’s Impact on Strategic Regions. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Publications Department Washington, DC, 2021.

- Pattanaik, S. S. “Engaging the Asian Giants: India, China and Bangladesh’s Crucial Balancing Act.” Issues and Studies 5, no. 5 (2019): 1940003. doi:10.1142/S1013251119400034.

- Phiri, I. “Media in “Democratic” Zambia: Problems and Prospects.” Africa Today 46, no. 2 (1999): 53–65. doi:10.1353/at.1999.0013.

- PiMA. Background Paper: Politics and Interactive Media in Zambia. PiMa Working Paper Series No.3. London: SOAS, PiMA, 2015.

- Price, M. The Enabling Environment for Free and Independent Media: Contribution to Transparent and Accountable Governance. Washington DC: USAID Office of Democracy and Governance, Occasional Paper Series, 2002.

- Rahman, M. H. “Freedom of Speech & Expression in Bangladesh in the Context of the ICT Act 2006.” SSRN Electronic Journal (2021). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3840306

- Rahman, S. “Development, Democracy and the NGO Sector: Theory and Evidence from Bangladesh.” Journal of Developing Societies 22, no. 4 (2006): 451–473. doi:10.1177/0169796X06072650.

- Riaz, A. “Bangladesh: From an Electoral Democracy to a Hybrid Regime (1991–2018).” In Voting in a Hybrid Regime, 21–31. Singapore: Palgrave Pivot, 2019. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-7956-7_3.