ABSTRACT

How might the creation of digital research infrastructure for preserving archival materials in Latin America resemble the infrastructure of extractivism? This essay examines the development of a digital repository for one of the most important collections of Amazonian history, culture, and politics at the Biblioteca Amazónica in Iquitos, Peru. Funded in part by the Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP) at the University of California, Los Angeles, the project seeks to digitally catalog and preserve photographs, newspapers, maps, and local journals at risk of further damage by humidity, rodents, lack of funding, and potential fires. In dialogue with critical infrastructure studies, I consider how this otherwise altruistic project fits into the broader landscape of extractive infrastructure in the Amazon region. To problematize what materialities might be flattened in the process of digitalization and their implications for the potential digital colonialism of the project, I compare the MEAP research infrastructure to other infrastructural projects in the Iquitos area, with special emphasis on the kinds of relational encounters that Iquiteños improvise when infrastructure does not work as intended. I argue that creating similar opportunities to engage and struggle with digital research technologies has the potential to transform them for local use and complicate their potentially extractive qualities.

RESUMO

Como a criação de plataformas digitais de armazenamento para preservar materiais de arquivo na América Latina poderia se assemelhar às infraestruturas do extrativismo? Este ensaio examina o desenvolvimento de um repositório digital para uma das mais importantes coleções de história, cultura e política da Amazônia na Biblioteca Amazônica em Iquitos, Peru. Financiado em parte pelo Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP) da Universidade da Califórnia, em Los Angeles, o projeto procura catalogar e preservar digitalmente fotografias, jornais, mapas e periódicos locais com risco piora nos danos devido à humidade, roedores, falta de financiamento e potenciais incêndios. Em diálogo com os estudos críticos de infraestrutura, exploro como esse projeto aparentemente altruísta se enquadra no panorama mais vasto das infraestruturas extrativistas na região amazônica. Para problematizar quais materialidades podem ser “achatadas” no processo de digitalização e assuas implicações para o potencial colonialismo digital do projeto, comparo a infraestrutura de investigação do MEAP com as de outros projetos infraestruturais na área de Iquitos, com especial ênfase nos tipos de encontros relacionais que os Iquitenhos improvisam quando a infraestrutura não funciona como esperado. Argumento que a criação de oportunidades semelhantes de envolvimento e de enfrentar dificuldades com as tecnologias de pesquisa digital tem o potencial de transformá-las para o uso local e complicar suas qualidades potencialmente extrativistas.

RESUMEN

¿En qué se parece la creación de plataformas digitales de almacenamiento para preservar materiales de archivo en América Latina a la infraestructura del extractivismo? Este ensayo examina la creación de un repositorio digital para una de las colecciones más importantes de historia, cultura y política amazónicas en la Biblioteca Amazónica de Iquitos, Perú. Financiado en parte por el Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP) de la Universidad de California, Los Ángeles, el proyecto pretende catalogar y preservar digitalmente fotografías, periódicos, mapas y diarios locales que corren el riesgo de sufrir más daños por la humedad, los roedores, la falta de financiación y los posibles incendios. En diálogo con la crítica de la infraestructura, considero cómo este proyecto, por lo demás altruista, encaja en el panorama más amplio de las infraestructuras extractivas de la región amazónica. Para problematizar qué materialidades podrían ser achatadas en el proceso de digitalización y las implicaciones de éstas para el potencial colonialismo digital del proyecto, comparo la infraestructura de investigación del MEAP con otros proyectos de infraestructura en el área de Iquitos, con especial énfasis en los tipos de encuentros relacionales que los iquiteños improvisan cuando la infraestructura no funciona como se pretendía. Sostengo que la creación de oportunidades semejantes para enfrentar y luchar con las tecnologías digitales de investigación tiene el potencial de transformarlas para el uso local y así complicar sus cualidades potencialmente extractivas.

On October 10, 2022, a fire ignited at the Biblioteca Amazónica in Iquitos, Peru, threatening one of the world’s most important collections of primary sources on Amazonian history, culture, and politics.Footnote1 The possibility of a fire in the nineteenth-century building that houses the institution was one of the many risk factors that my co-PI, the anthropologist Sydney Silverstein, and I had listed to qualify the library’s holdings as an “endangered archive” when we applied for a grant to digitize the collections through the Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Indeed, another of Iquitos’s most important collections of cultural heritage, the Archivo Departamental de Loreto, was razed by a fire in 1998. Having such a potential danger materialize five months into the funding period was a tragedy made worse by the fact that the origin point appeared to have been the room dedicated to digitization. Hundreds of items in the collection were waterlogged during firefighting efforts; the building itself also suffered smoke damage, and digital equipment worth thousands of dollars was lost to both heat and hose. Because of the immediate and heroic efforts of librarians and members of the MEAP digitizing team to prevent further damage by cleaning up after the firefighters, forensic experts could not determine the cause of the fire when they arrived on the scene the next day. The most likely culprit was a constellation of unfortunate coincidences: days of extremely high temperatures, a power outage, a power surge when the electricity returned, a leaky air conditioner disastrously situated above a surge protector, a short circuit, and a lithium camera battery that I had carried in my suitcase from California to Iquitos, and which was left plugged in for more than 24 h.Footnote2

My material entanglement with the circumstances surrounding a fire that sparked thousands of miles away from me compelled me to reflect more critically on the extractive implications of the otherwise altruistic aims of the project that Silverstein and I had initiated in May 2022 to give back to a library that had been important to both of our research. This essay takes up some of the questions that have emerged during the recovery period, questions that revolve around how US-based scholars of the Global South, and Latin America more specifically, position themselves with regard to their subjects of study. I consider what relationship might exist between digital colonialism and Global-North-generated scholarship that evaluates and interprets Latin American cultures, whether through traditional academic research or as part of a cultural preservation project like the one in Iquitos. How can we acknowledge our complicated material involvement with the regions we study? In doing so, how might we challenge if not get beyond the extractive paradigm?

In order to approach such questions, I join scholars like Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (Citation2012), Ramón Grosfoguel (Citation2016), and Macarena Gómez-Barris (Citation2017) in extending the idea of extractive economics to the cultural sphere, while also keeping present the material violence that extractivism always entails.Footnote3 To consider how digitizing the Biblioteca Amazónica might create extractive channels to remove knowledge from Iquitos as intellectual resources, I will focus on the idea of the pipeline as both a metaphor for and a physical part of the infrastructure of extractivism. Academic researchers in the Anglophone world refer to scholarly work in passive production as a research pipeline, and Angela Davis famously drew attention to public schools’ punitive systems as part of the pipeline feeding into the prison industrial complex (Citation2003). Both figurative usages draw from the invisibility of infrastructural hardware that seems to smoothly deliver gasoline to car tanks, water to faucets, and gas to stoves. But relatively recent events at the Dakota Access Pipeline and the PetroPeru pipeline in Bagua reveal these supposedly impervious and unseen ducts as sites of violent encounter between those who would have them be background and those for whom they represent palpable structural violence. In this case, then, “the dangers of [metaphorical] pipeline thinking,” to borrow from Ken McGrew (Citation2016), involve obscuring how even pipelines are “embedded in their physical environments … emerge within social ecologies, extending existing relationships between humans and their nonhuman environments” (Starosielski Citation2016, 44). If research infrastructures that facilitate the flow of information can function as extractive pipelines, then they do so as part of a complex ecology that interrupts and complicates the regulated flow of materialities earmarked as resources.Footnote4

Like scholarly production, infrastructure is an ambivalent and imperfect intervention in the colonial asymmetries of the present. It facilitates the transit of people, goods, and services, but it also introduces new uneven structural arrangements of power. Critical infrastructure studies have underscored the “boring” quality of infrastructure by focusing on the “analytical moment that happens precisely when one makes a distinction between figure and ground, where infrastructure appears to be the background of something else” (Hetherington Citation2019, 6). But pipelines make clear that the inherent unmentionableness of infrastructure hinges on one’s privilege. As Susan Leigh Star and others have theorized, infrastructure only recedes into the background when it works: “One person’s infrastructure is another person’s topic or difficulty” (Citation1999, 380). Building on this insight, postcolonial theorists have further argued that in colonial contexts, some infrastructure never recedes into the background. Kregg Hetherington and Jeremy Campbell state,

One aspect that Star’s definition of infrastructure as “background” does not account for particularly well is the primary experience of infrastructure that many people in the developing world have historically had: public building projects have offered spectacular proof of the presence of states, colonial powers, or multinational lenders. Infrastructure projects such as giant dams, highways, and canals, all of which were key to mid-20th century strategies of economic development, were hardly recognized as “invisible” by those who were touched by them (Citation2014, 192).

In what follows, I begin by considering the relationship that people in the Iquitos area have to their pipelines, broadly considered, in order to suggest how the digitization project fits into the wider landscape of more-than-human design. I then examine both the extractive qualities of the MEAP project and the ways in which the project challenges the smoothness implied in the pipeline metaphor. My argument is simple: the digitization of the Biblioteca Amazónica does in some ways follow the well-worn grooves of resource extraction in the region, but it is “not only” an extractive project.Footnote5 An ecological orientation toward pipelines that refuses to background their entanglements with the surrounding world can repurpose extractive infrastructure toward new research questions and generative self-critique.

Amazonian flows

Iquitos, the capital of Peru’s largest and least densely populated department, Loreto, is a city defined by its infrastructure or lack thereof. During the height of the rubber boom at the turn of the nineteenth century, the city was one of the wealthiest in South America, replete with building facades adorned by Portuguese tiles, elegant steamboats transiting its rivers, one of the best telegraph systems on the continent, and electricity long before other major cities in Peru such as Tacna and Cusco.Footnote6 By contrast, today, one of the most repeated descriptions of the Amazonian hub is that it is the largest city in the world inaccessible by road. The statement, though, depends on one’s perspective. While no road connects Peru’s fifth largest city of nearly half a million people to any of the country’s national highway networks, two paved paths offer routes in and out of Iquitos: one along the road to nearby Nauta, which took seventy years to build and was finally completed in 2005, and an under-construction route to the Colombian Putumayo that connects to Iquitos via the largest bridge in all of Peru, inaugurated in 2021. The stories of these and other engineering feats in the Iquitos area demonstrate the region’s disconnect between “infrastructures of control and coercion, often imposed from above in the interests of power, and the infrastructures of provision and entitlement, often demanded from below” (Rubenstein et al. Citation2015, 581). Whereas pipelines to extract raw materials from Iquitos are generally repaired when inoperable, demands for connectivity – whether via roads or Internet – have been characterized by sporadic delay, obstruction, and disjuncture.

Such interruptions are part of the capitalist flow of goods, services, capital, and labor in the upper Amazon. Anna Tsing has highlighted how in a globalized world, capitalist flows move only thanks to friction, that is, contact between universalizing forces that promote global capitalism and local governments, organizations, people, and conditions:

A wheel turns because of its encounter with the surface of the road spinning in the air it goes nowhere. Rubbing two sticks together produces heat and light; one stick alone is just a stick. As a metaphorical image, friction reminds us that heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power. (Citation2005, 5)

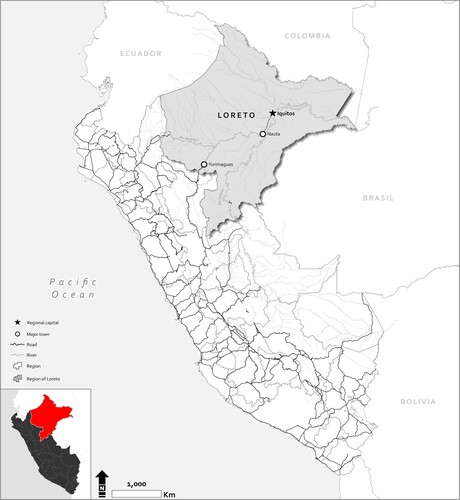

I am inspired by this idea of friction as a site for glocal connection, challenge, and change, to adapt the notion of “flow” to the geography of the Iquitos area. In this city that emerges at the confluence of various tributaries feeding into the Amazon, river currents are what tangibly flow (). Rivers are the original, material infrastructure of the Amazon basin, what Kregg Hetherington calls, referring to the environment, “the infrastructure of infrastructure” (Citation2019, 6).Footnote7 And, as Lisa Blackmore and Liliana Gómez have suggested, attention to the geopolitical and historical specificity of water can reveal “counterflows to hegemonic imaginaries” (Citation2020, 2). Flows through the Iquitos region have long been characterized by their irregularity, unpredictability, and sometimes circularity. Navigating the region’s rivers requires attention to fallen trees, fluctuating water levels, changing courses, shifting sands, and rapids; it demands contending, in other words, with what Javier Uriarte calls “fluvial poetics” (Uriarte, Citation2020). For Uriarte, not only do Amazonian peoples have an intimate relationship with riverine flows as infrastructure for transport and livelihood, but also the spatio-temporal rhythm of rivers inflects everyday life in the region and characterizes other infrastructural projects.Footnote8 Amazonian flows can be treacherous, unpredictable, and annoying as infrastructures that refuse backgrounding, but their irregularities can also be opportunities to adapt, respond, and work with the river, “to “read” rivers in new ways” (Uriarte, Citation2020). Relating infrastructurally to the Amazon region requires foregrounding the flow, and Loretano relationships with manmade infrastructures tend to resemble such Amazonian flows.

Figure 1. Map of the Loreto Department of Peru and its capital Iquitos, made by Nicholas Kotlinksi for Sydney Silverstein. Reproduced with permission from Silverstein.

Though the Iquitos-Nauta road – locally dubbed “the most expensive road on the planet” – is in many ways exceptional, it also exemplifies how the challenges of building pipelines in fluvial geography create material encounters in which infrastructures become critically foregrounded (Harvey and Knox Citation2015, 24). In the early nineteenth century, long before the founding of Iquitos, upriver Nauta was on its way to becoming an important trading post in the Upper Amazon, but the river’s flows had other plans. A sandbank formed in front of the town that changed the course of its history by preventing ships from docking (Knox Citation2017, 364). Nauta continued to serve as a major commercial center for smaller upriver communities, but Nauteños felt their distance from the international entrepôt of Iquitos as Loreto’s capital city grew and prospered in the years of the rubber boom and beyond. Before the road, the journey to Iquitos took days by land, twelve hours by ferry, and approximately five hours on the pricier “rápidos”; now one can arrive by motor vehicle in about an hour. Nonetheless, according to the ethnographers Penny Harvey and Hannah Knox, people’s relationships with the road have been fraught and antagonistic.

As Susan Star and Karen Ruhleder have insisted, structures become infrastructures only “in relation to organized practices,” their physical hardware entirely dependent on the human and nonhuman interactions that they knit together (Citation1996, 113). In the case of the Nauta Road, practices emerging with the road evoke disorder and disruption. Harvey and Knox’s illuminating ethnography of the road is peppered with local complaints about the lengthy construction – mired in corruption and political intrigue – the negligence of the local and state government, the road’s lack of functionality, its failed promise of connectivity, and the project’s penchant for bringing new problems to the area. Illegal loggers make use of the route in environmentally destructive ways; stagnant water dammed by the ruins of decades of construction caused a malarial outbreak; and people in Nauta insist that for a variety of reasons the road has exacerbated their isolation (Harvey and Knox Citation2015, 50). Additionally, the spatial practices of the Kukama people Indigenous to the region, who relate to the surrounding area through “movement, hunting, and gathering,” have been truncated by the presence of the road (Harvey and Knox Citation2015, 59–60). Like the rivers, the road makes its presence felt through such intrusive issues, which as Knox has suggested produce “an embodied or affective relationship with the road infrastructure” (Citation2017, 376). Whether through the deteriorated segments and potholes that lurch passengers and drivers from their seats or the rough sand and asphalt surface that wear at tires like sandpaper according to one of Harvey and Knox’s informants, the road does not retreat into the background (2015, 50).

The Iquitos-Nauta road’s pipeline ecology produces flows that are bumpy and disruptive, but in its Amazonian flow lies potential for accountability. I do not mean to suggest that Loretanos should not have more thoughtfully planned functional infrastructures nor that they should be deprived of the luxury of not having to think about their transportation networks. They should enjoy such privileges, but because of the geographic challenges of building large-scale projects in the region, erratic flows have defined Loretanos’ relationships with such projects. And, as Knox has convincingly argued, “politics enters the frame” at the sites of breakdown where those who move along, past, and over the road materially encounter their place in the region, the state, and the market (Citation2017, 376). Though this route was both “demanded from below” and initially carved out locally, when the state took over the project and contracted it out to a Brazilian construction firm, the road plan took on neocolonial qualities as a “universal” structure foisted on a riverine geography – indeed, mud was one of the major culprits of the road’s long and arduous construction (Knox Citation2017). As a result, Loretanos, according to Harvey and Knox, continuously confront their troubled relationships with the roadway. Far from a background, the road is a subject of conversations that keep exclusions, injustices, and “infrastructural violence” at the forefront of discussion.Footnote9

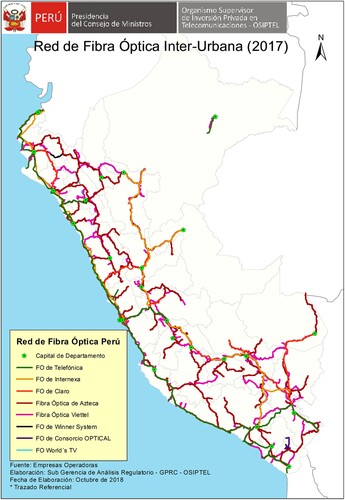

Two other major topics of conversation in the area further underscore the messy and generative ecological enmeshment of Loretanos with their infrastructure projects. Iquitos’s fiber-optic Internet and the Nanay Bridge, two very different kinds of networks, share a comically similar history of spectacular failure that helps to illustrate the everyday critique of infrastructure and consequent resilience in the face of it that is part of daily life in Loreto. In 2014, the Spanish multinational telecommunications company Telefónica published a color volume of collected essays on the culture, history, and biodiversity of Iquitos in honor of the arrival of fiber-optic Internet to the city, which coincided with the 150th anniversary of the Port of Iquitos. (The cables, by the way, snake below the Nauta road.)Footnote10 Numerous national newspaper articles also commemorated the achievement as a means of finally connecting Iquitos, with its infamously slow Internet, to the rest of the world. Despite the fanfare, the 90 kilometers of cable did not connect to anything at all (). Telefónica had laid the cable out of a contractual agreement with the Peruvian state to introduce fiber-optic infrastructure to major cities that did not have it, but the company had no obligation to make the cables functional. In relation to Peru’s fiber-optic network, Iquitos’s cables were in the middle of nowhere (see ). They received data from a microwave satellite network stretching from Yurimaguas to Nauta that then traveled along the subterranean pipeline to Iquitos resulting in approximately 1 Gigabit per second of Internet speed in Iquitos, one of the slowest in the country if not the world (Malpartida Citation2020). The invisibility of the subterranean fiber-optic cables became visible through discourse; Iquitos’s sloth-like bandwidth has long been a regular topic of conversation. In 2021, the country’s first “fibra subacuática que resista las agrestes condiciones que enfrentaría bajo los torrentes de los ríos” was introduced along the Huallaga River from Yurimaguas to Nauta, finally plugging Iquitos into the national network, but the hoped-for gigabits have not arrived along that pipeline. The Internet continues to follow an Amazonian flow through the region, entangled in the more-than-human ecology that slows and interrupts connectivity.Footnote11

Figure 2. Map of Peru’s Fiber-Optic Internet cables in 2017, showing the cables from Nauta to Iquitos isolated from the national network, created by Sub Gerencia de Análisis Regulatorio – GPRC – OSIPTEL and reproduced with permission.

The Internet has had a persistent presence in our work with the digitization team on the ground. We easily lose half of our Zoom meeting time to make our connection functional. Team members often link to their mobile phones or share personal hotspots to circumvent their sluggish wireless connections. Additionally, until fiber optic cables were extended to the Biblioteca Amazónica in May 2023, it was faster and more effective to take advantage of team members’ trips to Lima to upload large TIFF files, than to attempt the weeks-long endeavor of an Iquitos-based upload. Although Iquitos’s connectivity presents challenges, having it remains a luxury in the region; only 34% of Loretanos, six and older, accesses the Internet (López and Delgado Bardales Citation2022, 281).Footnote12 Through the truncated sentences and trailing syllables of Zoom check-ins and the long waits to see scanned materials, we inevitably face the irony of the project we are undertaking, namely, creating a digital repository for a library of local history and culture in a region where most people cannot yet access the Internet.

The recently opened Nanay Bridge even more strikingly materializes the Amazonian flows of Iquitos’s infrastructural webs and also inspires me to think about repurposing the potentially extractive elements of the access opportunities that we are creating. The imposing flame orange bridge towers over and eclipses the blackwater Nanay tributary, part of a multiphase project meant to connect Iquitos via roadways to Colombia’s Putumayo region in order to bolster regional travel and commerce, but when the bridge was ceremoniously launched in 2021, like Iquitos’s early fiber-optic cables, it did not connect to anything at all. News across Peru announced that the megaproject led to the backyard of a family in the predominantly Indigenous village of Santo Tomás, across the Nanay from Iquitos. Television images showed how the marvel of modern construction parodically and abruptly ended at a cement gateway that separated the road from the entrance to Don Luis and Doña Mirna Macuyama’s home. When I visited Iquitos in May 2022 to initiate the digitization project, the bridge’s obtrusive failures were also a popular topic of conversation. People seemed to take pleasure in the joke: “No va a ninguna parte,” they would say. “Termina en un huerto de paltas.” However, the disappointment of the bridge’s intended functionality did not leave the structure unused. Every evening, the Bellavista Port from which the bridge protrudes became congested with Motokars full of people wanting to catch the sunset – and perhaps an Instagram photo opportunity – from atop the bridge ().Footnote13 My co-PI, Sydney Silverstein, has insightfully theorized such infrastructural repurposing with regard to narco-infrastructure in the region as an affecting aesthetic relationship that promises Loretanos “consistency and resiliency” in the presence of otherwise nonfunctioning infrastructure (Citation2021, 444–445). Though the bridge, like the fiber-optic cables, was meant to introduce smooth pipelines to Iquitos, both became snarled in affecting Amazonian flows that demanded relational innovation through encounter.

The Biblioteca Amazónica Pipeline

The digitization of the Biblioteca Amazónica responds not to the potential opportunity presented by infrastructural “failures,” but rather to the potential threat they present, in this case, to cultural artifacts. Like many of the first library collections in Latin America, the Biblioteca Amazónica was created thanks to members of religious orders, but not until the late twentieth century.Footnote14 Founded in 1992 as a public institution under the auspices of the Centro de Estudios Teológicos de la Amazonía (CETA), the library has since absorbed local publications and numerous donations of private collections; its rare books, regional newspapers, maps, and photographs constitute the second most important collection of Amazonian history, culture, and politics after the Amazonas Public Library in Manaus, Brazil. Today, the library operates thanks to free rent provided by the Ministry of Culture and a shoestring budget financed by the Catholic Vicariate in the wake of CETA’s dissolution.Footnote15 Two part-time employees care for the collections and provide access to the handful of people who visit the library each week during its limited hours of operation. An Augustinian brother serves as the library’s director, though the charge is only one of his many responsibilities. The collections themselves are not climatized, and Amazonian humidity eats away at the paper pages taken from its forests, as do the rodents who inhabit the historic buildings along the Tarapacá Boulevard. I first became aware of these issues during a research trip in 2013, when the librarian Julio Ramírez Arévalo would apologetically hand me books and magazines, lamenting their fragility, or sometimes, with much chagrin, delivering the sad news that my request could not be fulfilled due to the material precarity of the item in question. What is more, as we discovered in the wake of the fire, the nineteenth-century building’s electrical wiring was treacherously out of date, and when rafters were downed and walls peeled back for repairs, the otherwise unobtrusive bat tenants, who inhabit many of Iquitos’s buildings, made their presence known. Feces lined the mahogany stairs leading up to the library’s iconic stained glass window during reconstruction. The post-fire triage awakened old concerns about the library’s future; in addition, the MEAP team and the Catholic priests voiced so many complaints reminiscent of the conversations generated by the Nauta Road, the Internet, and the Nanay Bridge. They revolved around the lack of support from Lima and the regional government in Loreto, the transience of pro-bono experts that flew in for only a couple of days, a budget in the red, and dishearteningly, the theft of documents and other objects as local contractors moved in and out of the building to make repairs.

Such contexts of fiscal abandonment and material precarity are common to many of the projects funded by the Modern Endangered Archives Project and its funding organization, Arcadia Fund.Footnote16 With a focus on projects outside of North America and Europe, “where the need is greatest and resources are most limited,”Footnote17 Arcadia and the Modern Endangered Archives Program have a “data ideology”Footnote18 deeply committed to avoiding the repetition of “colonial histories of extraction of both physical and intellectual property” in the form of digital colonialism. They turn down projects from scholars from the Global North to take equipment to the Global South, use it themselves, and leave with digital files, a practice which has been all too common in the history of Latin American libraries and archives.Footnote19 Instead, all of the work must be done locally by people from the community of the archive in question, and the equipment must remain in the community, too. The digital files generated must be made accessible through an online open-access repository, free and available to all Internet users. Furthermore, if those collections involve images or recordings of people, the principal investigators must consult them in the process of deciding what to share and how. The MEAP advisory board is so serious about the grant’s aims to serve local communities that PI intermediaries, such as Silverstein and me, based in other parts of the world, must seek outside funding for travel expenses so that one hundred percent of the Arcadia funds stay in the communities where projects are carried out.Footnote20 Additionally, unlike our project, many of the projects funded by MEAP have no intermediaries. The UCLA-based program has increasingly received applications from archives throughout the world and partnered with them directly. And, to account for the digital divide in Internet access between Los Angeles and the areas of their sponsored projects, MEAP has recently shifted to a mobile-friendly website design for digital collections. They also encourage cataloging metadata in multiple languages and the use of MEAP funds to create events on the ground to orient communities to the digital repositories.Footnote21 Through this community-grounded focus, a recent trend has emerged in which a specific project becomes a hub for people affiliated with other collections to learn hardware and software and borrow space and equipment. If, as Roberto Casati has suggested, the ideology of digital colonialism consists of, “If you can, you should,” then MEAP’s approach is more akin to, “If you have to, then how?” (Citation2015, 19)Footnote22

Our Iquitos-based project to digitize important journals, newspapers, photography collections, and maps was enthusiastically approved by the review board because of how much we had involved Iquiteños in the application process. Silverstein and I had numerous conversations with librarians, academics, and intellectuals, and Catholic priests to determine which artifacts to prioritize. We also began the laborious task of tracking down copyright holders in the area and securing permission to digitize and host their work. Silverstein, who completed eighteen months of ethnographic work in Iquitos between 2015 and 2016, built on the strength of her relationships with the Instituto de Investigación de la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP) and the Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (UNAP) to identify team members who could scan, edit, and generate metadata for the collection. At the time of writing in November 2023, we are eighteen months into our project and have an incredibly dedicated team of nine people divided into subgroups working on scanning, editing, and generating metadata. Silverstein and I are proud of having built a team comprised of students and young professionals, including Indigenous students on scholarship and young mothers.

Though in the initial phases of the project, Silverstein and I had to teach most of these team members how to use the hardware and software and archive the files, by now, their knowledge has far surpassed ours. Team members on the ground have increasingly stepped into leadership roles on their own initiative, organizing team trainings with local photographers and personnel from the Biblioteca Nacional del Perú in Lima. As a result, our WhatsApp conversations have transitioned from being questions directed at Silverstein and me to group members coordinating with one another and finding creative solutions for technical and logistical questions. Our dynamic is not entirely horizontal, but we take guidance from the team members on new ideas for procedures and needs. As an integral part of the research ecology of the Biblioteca Amazónica, the community formed by our team is the most immediate, and according to Silverstein, important result of the project. By taking charge of the digital archiving of historical documents according to international professional standards, investigating new work practices and processes, and training new team members, the team develops valuable knowledge and acquires professional experience relevant both in Peru and in the international network of document digitization and preservation. What is more, because of the fire, team members worked alongside specialists, learning how to stabilize and restore water-logged archival objects.Footnote23 These unexpected outcomes bring further tension to the potential coloniality of the project.

Further complicating our involvement is the archive’s relationship with a more notorious colonial entity, the Catholic Church. The Apostolic Vicariate of Iquitos, with a Spanish bishop and a team of Spanish priests, is the de facto custodian of the Biblioteca Amazónica’s cultural heritage. In the absence of support from the regional or state governments, ecclesiastical entities have long been at the forefront of producing, compiling, and archiving knowledge about Iquitos and the Loreto region. Nonetheless, the quality and intensity of their involvement waxes and wanes with changing leadership and personnel. The late Father Joaquín García, the former director of the Biblioteca Amazónica, was an avid reader and writer and a champion for the digitization of the library’s collections, but health issues prematurely put an end to his advocacy. When I first applied for the MEAP grant in 2019, the then-bishop Miguel Olaortúa Laspra refused to authorize the project, with no explanation. Upon the bishop’s untimely death, Father Miguel Fuertes, the parish accountant, reached out to me in hopes of reinitiating the process. Though the current church administration supports the project, our relationship with the priests is not without challenges. Both they and former members of CETA share a skepticism toward Arcadia’s open access requirement. During a public informational event on the project at the Feria del Libro de Iquitos in May 2022, CETA affiliates argued against offering the library’s content free of charge at a time when the library desperately needs funds to stay afloat. They also raised suspicions about the need for a digital repository hosted by UCLA when they felt that a locally generated one would suffice. Multiple layers of concerns with coloniality undergird these well-intentioned objections. On the one hand, given the history of strong-armed purchasing and looting of Latin American cultural heritage by institutions from the Global North, the priests’ skepticism is not unfounded. On the other hand, though, their anticolonial resistance to policies coming from a US institution also reflects “a privacy-fixated, data-clutching ideology” that opposes open access and is thus, according to Renata Ávila Pinto, a characteristic of digital colonialism.Footnote24 As intermediaries, Silverstein and I work actively to communicate with the priests across this plurality of data ideologies and build relationships in the shared interest of preserving the library’s cultural heritage and encouraging its use.

Despite our best efforts, though, the project cannot escape certain extractive qualities. We cannot use the MEAP funds to buy preservation materials for the precarious archival objects still at risk of damage in Iquitos, and we are limited by the $50,000 award amount to pay our workers Iquitos rates over twenty-four months for their highly technical skills, which are helping to build a digital repository hosted by a US institution, UCLA. That repository will inevitably go live with English metadata months before the Spanish metadata is ready and potentially years before the Vicariate creates a local repository. Additionally, that metadata, based on international norms, may not necessarily be useful to people from the general public in the Iquitos region wishing to access materials.Footnote25 Furthermore, we have yet to develop a plan that takes Internet access into account to make the digital collections usable to people throughout Loreto, beyond the city of Iquitos. And because infrastructure only comes into being relationally (Star Citation1999; Star and Ruhleder Citation1996), our digital research infrastructure implies more than the hardware, software, files, and online collections. As Sharon Webb and Aileen O’Carroll intimate, “providing access to our digital cultural heritage is an important task,” but it’s not enough (Citation2018, 134). Agiatis Benardou, Erik Champion, Costil Dallas, and Lorna Hughes assert that a “scholarly ecosystem” moves beyond the digital repository and access networks to include the users, the kind of research they conduct, and the requisition questions and projects that they formulate (Citation2018, 3). Only through the engaged and informed use of research infrastructures do researchers “act as a disruptive and transformative intervention that unsettles epistemic paradigms and allows the emergence of new kinds of intellectual enquiry” (Benardou et al. Citation2018, 11). In other words, only through the participation of researchers can our online repository adapt to surprising Amazonian flows.Footnote26 If we do not want our bridge to back up into an avocado orchard, it will have to come to life through work that happens beyond the funded phase of the project.

More-than-human lossyness and digital futurity in Loreto

To conclude, I return to one of the questions I posed at the start of this essay: how can we challenge if not escape the extractivist paradigm with this project and others like it? In general terms, to extract implies to remove and transform, and consequently, to lose something at the site of extraction, but at the end of our project, the collections of the Biblioteca Amazónica will remain on their shelves, however perilously. What is potentially lost, then, relates to what Zac Zimmer calls the “lossyness” implied in the digital conversion of material objects. Something is always lost, he insists, in the “translation between one medium and another” (Citation2018), whether the frequencies inaudible to human ears cut from WAV files in their conversion to MP3, or “the material traces of human interaction with textual objects … dog-eared pages, spines cracked from the frequent reference of a particular passage” (94). Such traces of human interaction certainly matter to our project, but there is also a more-than-human dimension to the Biblioteca Amazónica’s digital lossyness. Lost, too, will be the traces of future loss: the ashes of future fires and the molded pages, chewed spines, and excrement of nonhuman users of the collections. Though the physical library immersed in the Amazonian ecology will continue to acquire such a complex record of vulnerability, the digital collections will be safe from future flows. The digitization of the library’s collections thus gives rise to a quandary: by offering cultural artifacts for broad consumption, the project also hides its material connection to Iquitos’s rich history of cultural resilience despite the region’s willful exploitation, neglect, and abandonment by colonial, state, and neocolonial actors.

We cannot and probably should not attempt to maintain those potentially harmful Amazonian flows, but we can encourage Loretanos – so accustomed to turbulent rivers, bridges to nowhere, and the artifice of fiber optics – to create new points of embodied encounter with the digital repository pipeline, to find the ways that it does not work for them, to complain, and to adapt it and to it for their own new, improvised purposes. As both Harvey and Knox and Hetherington and Campbell have indicated, infrastructure always entails the promise of a better future. That future depends on what Lauren Berlant has called “a cluster of promises” whose fulfillment, in this case, is predicated on interventions by the regional and state government and the Catholic church (Citation2011, 24). Since the rubber boom, the futurity of infrastructural promises in Loreto has always depended on relationships of coloniality – whether internal or foreign – but Silverstein and I constantly discuss, question, and challenge our place in the North–South asymmetries as we work with the team in Iquitos. Acknowledgement of and attention to power structures involved in infrastructural projects is essential to undertaking the hard work of building to connect and engage rather than exclude and harm. Moving forward, I envision our part in the MEAP project’s cluster of promises to involve implementing measures to continue promoting the archive locally, so that its resources are not made available primarily for those beyond the region. We plan to create user guides in Spanish to complement the digital repositories and offer publicity events, radio spots, and social media campaigns to orient users to the collections. We have also begun initial talks with our team members about what it might take to implement a local intranet to extend access to the repository in areas of Loreto with little connectivity. For the project to work, we must encourage Amazonian flows that are more verbs than nouns, ones that keep the digital repository alive through innovative use while waiting for other connections. Our way out of the extractive paradigm of digital colonialism, then, is incomplete and postponed to an undetermined future that does not depend solely on us, but also on other promises to eventually incorporate Loreto more meaningfully into the nation and the world beyond, remedying cables, roads, and truncated bridges.

Acknowledgement

Mi más profundo agradecimiento a mi colaboradora, Sydney Silverstein, y al equipo MEAP: Iris Abril del Águila Yahuarcani, Margarita del Águila Villacorta, Juan José Bellido Collahuacho, Christian Ahuanari Tamani, Susan Layche Celis, Roldán Dunú Tumi Dësi, Julio Ramírez Arévalo, Jhonatan Rodríguez Macuyama, Nixia Nubia Rodríguez Macuyama, y Maruja Pierina Zárate Moreno. También agradezco al Padre Miguel Fuertes y al Hermano Víctor Lozano por su apoyo y dedicación al proyecto. Dedico este ensayo al Padre Joaquín García (1939–2024), gran amante de la Amazonía peruana y su biblioteca.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amanda M. Smith

Amanda M. Smith is Associate Professor of Latin American literature and culture at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her research explores relationships among space, ecology, decoloniality, and development in contemporary Latin American cultural production. Her book, Mapping the Amazon: Literary Geography after the Rubber Boom (Liverpool University Press, 2021), examines how canonical twentieth-century novels in constellation with a variety of other media forms produce Amazonian space by shaping how people across the globe understand and use the region. She was the co-founder and first co-chair of the Amazonia section of the Latin American Studies Association and is currently co-PI on a Modern Endangered Archives Program grant to digitize the Biblioteca Amazónica in Iquitos, Peru. Smith's work has appeared in The Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies; The Journal of West Indian Literatures; Revista de Estudios Hispánicos; Revista Hispánica Moderna; ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America; A contracorriente; Chiricú Journal: Latina/o Literatures, Arts, and Cultures; and Ciberletras.

Notes

1 Official reporting stated that there were no flames only glowing embers and smoke. See Fuentes (Citation2022). However, when I shared photographs of charred furniture and equipment with the structural fire engineering expert Erica Fischer on October 17, 2022, she determined that the damage was not possible without the presence of flames.

2 Fischer also confirmed that lithium batteries are highly combustible, especially in such conditions.

3 My book (Smith Citation2021) also addresses how extractive practices permeate tourism and literary and cultural production in and about Amazonia.

4 I consider digital research infrastructure as a pipeline following Nicole Starosielski’s provocation to extend the definition of a pipeline to any “media ecology that creates channels along which material can flow [seemingly] unhindered by environmental circumstances.” See Starosielski (Citation2016, 53).

5 Here I am following Marisol de la Cadena's call to consider how intersecting worlds and cosmovisions give rise to "not only entities." In this case, a pipeline may be extractive infrastructure in a worldview that separates humans from nature, but it will also inevitably be not only that. See De la Cadena (Citation2015).

6 Though Lima’s city lights were installed in 1886, streetlights came to Iquitos in 1905, to Tacna in 1912, and Cusco in 1914. See Huamaní Huamaní (Citation2014) and Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Energía y Minería, Osinergmin (Citation2016).

7 He writes, “The environment precedes infrastructure the way a landscape precedes an engineer’s design for a bridge, which itself precedes a bridge. To put is crassly, in this formulation, environment is the infrastructure of infrastructure.”

8 Uriarte makes a direct connection between rivers as infrastructure and other infrastructural projects in the Amazon region: “These ‘fluvial poetics,’ and their role in the everyday lives of the region’s inhabitants, have also been central to the state’s modernization and infrastructure projects of production and exploitation of the soil, as they tried to impose new ways of conceiving of travel (and, in more general terms, displacement).”

9 As Dennis Rodgers and Bruce O’Neill insist, “Infrastructure is not just a material embodiment of violence (structural or otherwise), but often its instrumental medium, insofar as the material organization and form of a landscape not only reflect social orders, thereby becoming a contributing factor to reoccurring forms of harm” (Citation2012, 404).

10 The layered nature of infrastructure is one of its qualities. Starosielski has shown how fiber-optic cables are often laid in relation to previously established infrastructures, and Fernando Santos-Granero and Federica Barclay have traced a history of extractivist cycles building on the infrastructure established by previous cycles. See Santos-Granero and Barclay (Citation2002).

11 The fiber-optic cables are yet to be extended to homes or most businesses, for example.

12 According to the essay, the percentage is even lower when considering those with access at home.

13 One need only search a social media platform for “Puente Nanay” to see creative selfies generated a top a bridge that did not go anywhere.

14 Even today, with a relative democratization of Internet and social media platforms for hosting cultural heritage, few Amazonian archives exist in Peru. José Ragas’s comprehensive annotated list of “important digital collections on Peruvian historical sources written, printed, visual, or sonic” includes only three mentions of Amazonian sources, two of which are Facebook pages. See “Digital Resources: Digital Peru, 2.

15 The late intellectual and progressive priest Joaquín García, author of many works on Iquitos, founded CETA in 1972 through an agreement with the Vicariate. The initial aim of the institution was to adapt the reforms of Vatican II to the Amazonian context, and CETA also produced numerous publications on the history and ethnography of the region. Eventually, members of CETA gathered their personal libraries to create the foundation for the Biblioteca Amazónica, which originally opened in 1992, with some support from the regional government of Loreto. Both a budget crisis and the declining health of García caused CETA to dissolve in 2018, at which time the Biblioteca Amazónica officially passed to the hands of the church, causing its status as a public institution to become muddied. See Vásquez Valcárcel (Citation2018).

16 The Arcadia Fund is a UK-based charity founded in 2001 by the philanthropist couple Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. The organization provides financial support to projects around the world focused on preserving endangered culture, protecting endangered nature, and promoting open access, according to their website, https://www.arcadiafund.org.uk/.

18 Poirier et al. define “data ideology” as “a complex set of assumptions and understandings, both tacit and explicit, that form a meta-discourse about data, how it functions, what needs to be done with it, who should handle it and how, and why it is valued and might be rendered still more valuable” (Citation2020, 215).

19 Aguirre and Salvatore underscore how important private collections in Latin America were the “objeto de saqueo o compra por parte de instituciones extranjeras interesadas en aquello que Ricardo Salvatore ha llamado ‘la empresa del conocimiento’” before they could be incorporated into public or university collections. See Aguirre and Salvatore (Citation2018, 13)

20 In fact, Arcadia does not allow for any indirect costs to be taken from the grant money either, which makes listing US universities as grant recipients a challenge. Indeed, they are infrastructurally set up to partner directly with archives abroad and place the pressure on US-based PIs to negotiate terms with their institutions when needed.

21 Rachel Deblinger, director of the Modern Endangered Archives Program at UCLA, in conversation with the author, July 31, 2022.

22 “El colonialismo digital es una ideología que se resume en un principio muy simple, un condicional: ‘Si puedes, debes.’ Si es posible hacer que una cosa o una actividad migre al ámbito digital, entonces debe migrar” Casati (Citation2015, 19).

23 Staff from the Prince Claus Cultural Emergency Relief Fund, which supported fire recovery efforts, were so impressed by our team’s knowledge, that they have invited us to apply for a prevention grant so that team members can put their skills to use training other local cultural heritage institutions in best practices for archiving and digitizing and preventing and mitigating damage from disasters.

24 Making sure to call attention to the potential surveillance made possible by an apparently democratic distribution of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), Ávila Pinto argues that a commons of digital heritage (“patrimonio digital común”) is central to overthrowing digital colonialism (Citation2018, 24). Indeed, user data from the Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies affirms that subscription academic articles are readily available to scholars working in the centers of former empires in the Global North, where universities provide them with paid access. The geography of informational access expands to the Global South dramatically when the same articles are made available with open access.

25 Poirier et al. suggest that international data standards can exclude certain publics. They write, "As more diverse research domains are incorporated into the universe of open data, standards tend to proliferate, becoming less 'standard' as they evolve to the specificities that diverse communities address with their data." See Poirier et al. (Citation2020, 211). So far, we have been limited by standards imposed by Arcadia and UCLA to reduce such diversity.

26 Because at the time of writing, the metadata for the project is not yet complete and our collection is not yet live, we cannot analyze how usage of the archival materials might reinforce or challenge the digital colonialism of the project. We hope to undertake this work moving forward in order to make the archive both desirable and accessible to people in Loreto, Peru, and Latin America more broadly.

References

- Aguirre, Carlos, and Ricardo D. Salvatore. 2018. Bibliotecas y cultura letrada en América Latina: Siglos XIX y XX. Lima: Fondo Editorial Pontifícia Universidad Católica del Perú.

- Benardou, Agiatis, Erik Champion, Costis Dallas, and Lorna M. Hughes. 2018. Cultural Heritage Infrastructures in Digital Humanities. Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Blackmore, Lisa, and Liliana Gómez. 2020. “Beyond the Blue: Notes on the Liquid Turn.” In Liquid Ecologies in Latin American and Caribbean Art, edited by Lisa Blackmore and Liliana Gómez, 1–10. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Casati, Roberto. 2015. Elogio del papel: Contra el colonialismo digital. Translated by Jorge Alcides Paredes. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. 2012. “Ch'ixinakax Utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111 (1): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-1472612.

- Davis, Angela Y. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete? An Open Media Book. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press.

- De la Cadena. August 22, 2015. “Uncommoning Nature.” E-Flux Journal. http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/authors/marisol-de-la-cadena/.

- Fuentes, Valentin. October 10, 2022. “Iquitos: Incendio y cortes de luz en Biblioteca Amazónica de Loreto pone en riesgo libros y escritos.” La República. https://larepublica.pe/sociedad/2022/10/09/iquitos-incendio-y-cortes-de-luz-en-biblioteca-amazonica-de-loreto-pone-en-riesgo-libros-y-escritos-iglesia-catolica-de-iquitos-ministerio-de-cultura-direccion-desconcentrada-cultura-loreto.

- Gómez-Barris, Macarena. 2017. The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives. Dissident Acts. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2016. “Del extractivismo económico al extractivismo epistémico y ontológico.” Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo (RICD) 1 (4). https://doi.org/10.15304/ricd.1.4.3295.

- Harvey, Penny, and Hannah Knox. 2015. Roads: An Anthropology of Infrastructure and Expertise. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hetherington, Kregg. 2019. “Introduction. Keywords of the Anthropocene.” In Infrastructure, Environment, and Life in the Anthropocene, Experimental Futures, edited by Kregg Hetherington, 1–13. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478002567.

- Hetherington, Kregg, and Jeremy M. Campbell. 2014. “Nature, Infrastructure, and the State: Rethinking Development in Latin America: Nature, Infrastructure, and the State.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 19 (2): 191–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12095.

- Huamaní Huamaní, Edilberto. 2014. “Iquitos tan lejos y tan cerca: Un siglo de telecomunicaciones en la Amazonía.” In Iquitos, edited by Rafael Varón Gabai, and Carlos Maza, 76–81. Lima: Telefónica del Perú.

- Knox, Hannah. 2017. “Affective Infrastructures and the Political Imagination.” Public Culture 29 (2): 363–384. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-3749105.

- López, Lee Frank Mendoza, and José Manuel Delgado Bardales. 2022. “Tecnologías de información del gobierno digital: Acceso a internet y barrera digital caso Loreto- 2021.” Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 6 (4 ): 281–297. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i4.2586.

- Malpartida, Víctor. August 4, 2020. “Tenemos fibra óptica en Iquitos?” Diario La Región. https://diariolaregion.com/web/tenemos-fibra-optica-en-iquitos/.

- McGrew, Ken. 2016. “The Dangers of Pipeline Thinking: How the School-to-Prison Pipeline Metaphor Squeezes Out Complexity.” Educational Theory 66 (3): 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12173.

- Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Energía y Minería, Osinergmin. 2016. La industria de la electricidad en el Perú: 25 años de aportes al crecimiento económico del país. Lima: Osinergmin.

- Pinto, Renata Ávila. 2018. “¿Soberanía digital o colonialismo digital?” Sur: Revista Internacional de Derechos Humanos 15 (27): 15–28.

- Poirier, Lindsay, Kim Fortun, Brandon Costelloe-Kuehn, and Mike Fortun. 2020. “Metadata, Digital Infrastructure, and the Data Ideologies of Cultural Anthropology.” In Anthropological Data in the Digital Age: New Possibilities – New Challenges, edited by Jerome W. Crowder, Mike Fortun, Rachel Besara, and Lindsay Poirier, 209–237. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24925-0_10.

- Rodgers, Dennis, and Bruce O’Neill. 2012. “Infrastructural Violence: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Ethnography 13 (4): 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435738.

- Rubenstein, Michael, Bruce Robbins, and Sophia Beal. 2015. “Infrastructuralism: An Introduction.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 61 (4): 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2015.0049.

- Santos-Granero, Fernando, and Frederica Barclay. 2002. La frontera domesticada: Historia económica y social de Loreto, 1850–2000. Lima: Fondo Editorial PUCP.

- Silverstein, Sydney M. 2021. “Narco-Infrastructures and the Persistence of Illicit Coca in Loreto.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 26 (3-4): 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12582.

- Smith, Amanda M. 2021. Mapping the Amazon: Literary Geography After the Rubber Boom. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Star, Susan Leigh. 1999. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (3): 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326.

- Star, Susan Leigh, and Karen Ruhleder. 1996. “Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces.” Information Systems Research 7 (1): 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.7.1.111.

- Starosielski, Nicole. “Pipeline Ecologies: Rural Entanglements of Fiber-Optic Cable.” In Sustainable Media: Critical Approaches to Media and Environment New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Uriarte, Javier. July 28, 2020. “Fluvial Poetics in the Amazon.” ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America xix, xix (3). https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/fluvial-poetics-in-the-amazon/.

- Vásquez Valcárcel, Jaime. September 4, 2018. “CETA, disuelta sin revuelta.” Diario Pro y Contra. Accessed September 4, 2018. https://proycontra.com.pe/ceta-disuelta-sin-revuelta/.

- Webb, Sharon, and Aileen O’Carroll. 2018. “Digital Heritage Tools in Ireland: A Review.” In Cultural Heritage Infrastructures in Digital Humanities. Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities, edited by Agiatis Benardou, Erik Champion, Costis Dallas, and Lorna M. Hughes, 127–135. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Zimmer, Zac. 2018. “Lossyness: Material Loss in the Cloud or Digital Ekphrasis.” Revista Hispánica Moderna 71 (1): 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhm.2018.0005.