Abstract

Many societal challenges need to be resolved through innovative solutions at system level. Previous scholars have argued that it may be wise to combine design practice and system theory to form a management method for public sector innovation. However, it appears that few scholars have developed innovation management methods based on that combination. The aim of this article is therefore to contribute with new knowledge about how design practice and system theory can be combined in order to drive public sector innovation. The article proposes the development of a previously proposed systemic design management model and presents a toolbox with twelve innovation management tools. Although there is a logic in using the tools in a certain order, this article emphasizes the need for a flexible use of the tools and to be open to moving back and forth between different tools. The results also indicate that an initial key tool is to ensure that the right people become involved in the different phases of the innovation process. It is more important to involve the right people in different phases than to follow a specific pre-designed process model. In order to successfully create and implement innovative solutions at system level, the innovation processes need to engage different human resources for different tools. Different resources that understand the needs can contribute with new perspectives and also possess the mandate to make systemic changes.

1. Introduction

Torfing, Sørensen, and Røiseland (Citation2019) argue that today’s societal challenges require a paradigmatic shift in governance. In practice, public managers have identified the same need, and act by embracing the concept of “innovation” as a key driver for finding solutions to pressing societal problems. Both public managers and scholars widely agree that incorporating design-thinking methods can foster this innovative mindset within the public sector, thereby leading to more effective policies and services (Kimbell Citation2016; Lewis, McGann, and Blomkamp Citation2020; Sangiorgi and Prendiville Citation2017). This trend is evident in the increasing utilization of design methods in innovation labs (Bason Citation2014; McGann, Lewis, and Blomkamp Citation2018) and public sector innovation units (Villa Alvarez, Auricchio, and Mortati Citation2022), such as participatory and human-centred approaches, to co-define, co-create and co-produce public value.

Despite the growing popularity of design methods in the public sector, scholars acknowledge several challenges that are associated with their implementation. One concern is that the traditional focus of design methods on experiences and creativity may overlook the understanding of organizational complexity, and clash with existing organizational cultures and practices (Kimbell and Bailey Citation2017). Critics argue that advocates of design thinking sometimes neglect empirical and theoretical work in public organizations, which leads to naive and ill-informed propositions (Clarke and Craft Citation2019). Moreover, there are challenges such as implementation barriers, political feasibility and decision-making constraints, which are often overlooked in the public administration literature but can significantly impact the effectiveness of design-led approaches (Howlett Citation2020). Additionally, design-led approaches often rely on small-scale experiments and prototyping, which are effective for generating innovative ideas and solutions. However, scaling up these initiatives to larger public service contexts can present challenges (Lewis et al. Citation2020). Without proper integration into public services or diffusion into broader public management processes, such interventions may be perceived as superficial or cosmetic uses of design (Komatsu et al. Citation2021).

To address these challenges, previous scholars have identified the strengths of combining design and systems theory (Pourdehnad, Wilson, and Wexler Citation2011; Buchanan Citation2019). However, there seems to be an inherent tension between the two aspects of designerly methods in public sector innovation: design practice, with its human-centred and intuitive approaches, and a system perspective, aimed at analyzing and managing complex system problems. The challenge is to create solutions that integrate the genuine needs of citizens’ everyday lives while ensuring the effective alignment of internal processes within a system structure for the optimum outcomes.

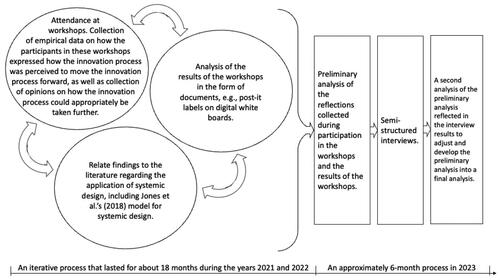

To explore this tension in practice, this paper examines a specific case study: the Care at Home initiative in Uppsala, Sweden. This initiative is part of a larger healthcare reform process in Sweden, which involves significant system and structural changes to the Swedish public healthcare system. The case illustrates the collaborative efforts of various stakeholders to integrate design and system perspectives in order to create and implement innovative solutions. The healthcare sector serves as an appropriate context for our case study as it is a system that faces increasing complexity due to a multitude of interconnected issues. These issues include interactions among patients, medical personnel, workplaces, tools, services, environment, society and the policy framework (Jones Citation2014). By examining how the Care at Home initiative unfolded, and investigating the opportunities and challenges perceived by the involved actors, our aim is to shed light on the integration of design and system-thinking approaches in practice, and thereby contribute to increased opportunities for researchers and practitioners to find solutions to pressing societal problems (See ).

Figure 1. A Schematic description of the relationship between the study behind this article and the aim of this article.

To achieve this aim, this article addresses the following research question: What seems to be enabling factors when combining systems perspective and design practice so it becomes a more well-functioning innovation management method?

Our research enriches the field of policy design and practice by providing insights into the integration of design and system principles, and addresses the call made by several researchers to explore how systemic design can be operationalized and utilized in practice in the public sector (Blomkamp Citation2022; Starostka, de Götzen, and Morelli Citation2022).

2. Theoretical background

In this section, we describe the theoretical background to why it is of interest to study enabling factors to combine design practice and system perspective, and how these can be combined.

System thinking involves understanding the relationships between components of a system, and how they interact to produce an outcome. Design thinking, on the other hand, is an approach to problem solving that focuses on user experience, creativity and collaboration. By combining these two approaches, innovation managers can create solutions that consider the complexity of the system while also considering the needs of the user. The combination of system thinking and design thinking has been recognized as a powerful approach to problem solving (Jones Citation2018; Mugadza and Marcus Citation2019). Further, Buchanan (Citation2019) argues that combining system thinking and design thinking can create more effective innovation processes that address complex problems. This reasoning is in line with Pourdehnad, Wilson, and Wexler (Citation2011), who propose the combination of system thinking and design thinking to create a more holistic, creative and effective approach to problem solving. They argue that combining system thinking and design thinking will lead to more successful problem solving.

Kaufman and Brethower (Citation2019) argue that we must integrate design thinking and system thinking into our planning processes. This perspective is also strengthened by Lynch et al. (Citation2021), who believe that “design thinking can and should include a more holistic systems thinking perspective as part of its drive to encourage corporate innovation. We argue that design thinking should take a much wider view of who are their stakeholders” (518). Further, Gianelloni and Goldstein (Citation2020) argue that system thinking and design thinking share many of the same skills and traits—a claim that increased our confidence that it is possible to combine these theories into a useful innovation management method.

Buchanan (Citation2019) argues that the best way to implement these two tools together is to first use system thinking to understand the underlying principles of the system, and then use design thinking to create solutions that address the identified problems. Similarly, Pourdehnad, Wilson, and Wexler (Citation2011) argue that “an integrated approach to problem resolution requires design thinkers to expand their understanding of good systems design principles with a purposeful consideration of the social systems they are working within” (59).

Pourdehnad, Wilson, and Wexler (Citation2011) argue that, in order to concretize the combination of design and system theory, it is necessary to ensure that everyone who works in the innovation process starts from the same system thinking principals, to give everyone the same shared mindset. Pourdehnad, Wilson, and Wexler (Citation2011) stress further that, in order to succeed with innovations at the system level, the actors involved need to have a willingness to sacrifice the performance of the part for the performance of the whole, in order to not risk sub-optimising the performance of the whole.

Conceptually, we use the term “systemic design” to describe an emerging and pluralistic design-led practice for planning and implementing envisioned changes in society (Blomkamp Citation2022; Jones Citation2014, Citation2018; Kimbell and Street Citation2009; Sevaldson Citation2011). Adopting a practice perspective in systemic design represents a distinct mode of thinking (Sevaldson Citation2019). It encourages us to dig deep into the actual work of systemic design, including formulating, planning and implementing these methods.

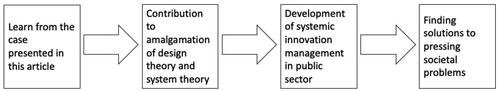

However, it appears that few scholars have developed innovation management methods based on design and system theory. Gianelloni and Goldstein (Citation2020) offer support for a model of the system thinking and design thinking relationship that is applied in education. Pourdehnad, Wilson, and Wexler (Citation2011) describe how they worked with design and systems in a case that contributes with some perspectives that are useful for concretization. The clearest idea about how to combine design and system theories was identified as a systemic change method suggested by Jones et al. (Citation2018) in their Systemic Design Toolkit, which comprises seven steps:

Framing the system; setting the boundaries of your system in space and time and identifying the hypothetical parts and relationships.

Listening to the system; Listening to the experiences of people and discovering how the interactions lead to the system’s behavior. Verifying the initial hypotheses.

Understanding the system; Seeing how the variables and interactions influence the dynamics and emergent behavior. Identifying the leverage points to work with.

Defining the desired future; Helping the stakeholders articulate the common desired future and the intended value creation.

Exploring the possibility space; Exploring the most effective design interventions with potential for system change. Defining variations for implementation in different contexts.

Designing the invention model; Defining and planning how your organization and eco-system should (re-)organise to deliver the intended value.

Fostering the transition; Defining how the interventions will mature, grow and finally be adopted in the system.

indicates how Jones et al. (Citation2018) describe the relationship of different stages to design and system perspectives.

Figure 2. An illustration describing Jones et al. (Citation2018) Systemic design model.

3. Method

In this section, we describe how the study was carried out and how the collected data was analyzed. We also describe the case in which this study was conducted.

In order to answer the research questions, this study was carried out using a qualitative method. Data was collected through document analysis, participatory observation and interviews. The paper is based on an in-depth case study. In the case, an innovation management process combined system theory and design theory with the aim of coming up with innovative solutions for the improvement of a complex healthcare system. The study took a practice-perspective by focusing on how systemic design is practised in a real-world context, and on the opportunities and challenges that arise during an innovation process.

3.1. The case

There is an ongoing major systemic and structural change of the Swedish healthcare system. One part of this change is related to increased distributed care at home (the Care at Home project). This involves different administrations within Region Uppsala and the social administrations in the county’s eight municipalities. In this area, a collaborative project between administrations within Region Uppsala and municipalities was started. The participants in the Care at Home project needed to increase collaboration, communication, and understanding of each other’s efforts, conditions and needs to increase the quality of the distributed care at home. This project constituted the case for this study. Systemic design was used at the start of the project to contribute to changes in the complex service system that constitutes the provision of care. The process of developing systemic design was initially developed for the Care at Home project, and was later implemented in a development process related to palliative care at home.

3.2. Action research

In the study behind this article, participatory action research (PAR) was considered to be a suitable method. This method gives participants in the research process the opportunity to benefit from the ongoing process of the research (Stringer Citation2014; Reason and Bradbury Citation2013). Further, Chevalier and Buckles (Citation2013) stated that action research is currently included as an “important method in professional business development and often includes interdisciplinary dialogue” (1). However, PAR is not an exact method but can be seen as a “family of approaches” (Reason and Bradbury Citation2013, 7). In the study behind this article, “action” has meant that the researchers have taken an active role in the studied phenomena.

3.3. Data collection

Data was collected by means of three data collection techniques: document studies, participant observation and interviews. The documents that formed the basis for the study were the material produced at project group meetings and by the collaboration workshops with participants from Region Uppsala and the municipalities. Documents were generated in the form of process maps, digital post-it notes and matrices. The material was produced in approximately 20 project meetings and one large workshop with a broader amount of concerned employees within the health care sector and one workshop with top health care management. The collection of data from the second source—participant observation—was performed by two of the authors of this article, who were responsible for the implementation of these approximately 20 meetings, and another of the authors, who was present during the workshops and four of the meetings. By working with PAR, the authors of this article gained good insight into what the participants in the innovation process experienced as enabling factors for applying systemic design as an innovation management method. Interviews comprised the third data collection technique, and these were conducted with participants in this development process. For more details about the documents, participant observation occasions, and participants and interviewees, see Appendix A.

Semi-structured interviews were used in this study, see Appendix B. A purposeful selection process was used in order to identify appropriate respondents. The selection of respondents was based on the level of involvement in the work that sought to combine design theory with system theory. The selection process resulted in the ten people who were most involved in the development of the project for distributed care at home. Three of the respondents had also been involved in the development of the methodology that was used in the Care at Home project, which was conducted within the framework of seeking to combine system and design theories. Two of these respondents (the same two who also conducted the above-mentioned participatory observation) are also coauthors of this article.

The two respondents who are also authors of this article were interviewed by the research colleague who conducted all of the interviews. All ten interviews were conducted using the online platform Zoom. All interviews were transcribed to obtain clear material to analyze.

3.4. Analysis

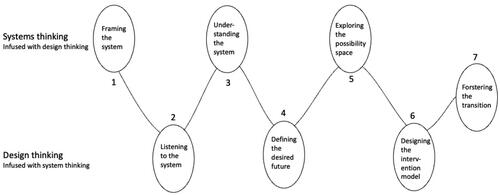

For about a year and a half, an iterative process took place in collecting data from documents and participant observation, and relating this data to the literature regarding the application of systemic design, including Jones et al. (Citation2018) model for systemic design, with the purpose of seeking to develop the model and its application. A preliminary analysis was then made of the important lessons that we had learned by seeking to apply systemic design in the innovation work within the case. This was followed up with semi-structured interviews to generate more data and validate preliminary findings, which ultimately resulted in a final, second analysis (see ). By interviewing the two respondents who are also authors of this article, an equivalent empirical basis was generated in the form of transcribed interviews before the second analysis. In the second analysis, the results of the preliminary analysis could therefore be compared with the texts in the transcribed interview transcripts. Thereby it became easier to equate these two respondent’s input with the other interviewees.

The final analysis consisted of two parts. The first was a summary of how the process of applying systemic design as an innovation management method had developed, and the second was an analysis of what seemed to be enabling factors for applying systemic design as an innovation management method. In the latter, the focus was on what constituted key factors in the work of improving and practically applying systemic design in an innovation process.

The analysis process can be described as abductive, insofar as the starting point in the empirical process (the first phase) was based on existing theories about systemic design and how the iterative analysis process reflected on existing theory, while the data that the empirical process initially generated was categorized and analyzed inductively to then be applied to the existing theories of systemic design.

Both the preliminary and the second analysis were performed by the thematic compilation of findings in documents and orally provided statements. In the preliminary analysis, the oral statements consisted of material from participant observations, with the inclusion of statements from the interviews in the second analysis. In the second analysis, the results of the preliminary analysis were validated to the extent that any findings from the preliminary analysis that were disputed in the second analysis were removed. The output from the second analysis comprised findings from the preliminary analysis that were repeated in the second analysis.

3.5. Bias

Qualitative research always involves a risk of bias. The subjective nature of qualitative research means that it is next to impossible for the researcher to be completely detached from the data, and nor was that the ambition in this case, as this research was conducted using PAR. As the participants in the processes that generated the data for this study did not know what expectations the researchers had, and as we worked with open-ended questions in the interviews, we consider to be likely that there was no obvious bias on the part of the respondents. Throughout the initial iterative process, we continually reevaluated the impressions and the gathered data.

4. Findings

In this section, we report on what emerged in the study with regard to answering the research question: What seems to be enabling factors when combining systems perspective and design practice so it becomes a more well-functioning innovation management method?

We have also included some quotes as examples of the findings. These are presented in italics with indents.

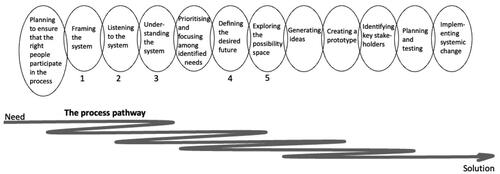

The use of a systemic design framework as an innovation management method started within the Care at Home working group during 2021, applying the systemic design approach developed and described as a “toolkit” (Jones et al. Citation2018). It led to an evolved toolkit containing parts of the Jones et al. (Citation2018), toolkit but in some parts developed and supplemented. See . Below is also described how findings during the action research led to the developed toolbox.

Figure 4. A Description of the proposed toolbox and the flexible process of using different tools, during the journey from need to solution, in order to create good conditions for an innovation process. The numbers one through five under some tools indicate that those tools are directly derived from Jones et al. (Citation2018) toolkit, while the tools without numbers under them are new to this toolbox.

One challenge that emerged early in the process of applying Jones et al. (Citation2018) toolkit was that this method did not sufficiently help the working group to create solutions to manage the organizational structures that constituted the barriers they had identified. When the working group worked from the patient’s perspective, the group saw problems and challenges directly connected to the patient, but it was not necessarily there that the changes had to take place. In order to implement changes, the group needed to work much more deeply with the organizational structures and cultures. The Care at Home working group realized that the systemic design approach by Jones et al. (Citation2018) needed to include several new steps in order to achieve system improvement. These new steps are described below.

One insight the working group gained was that the quality of the result of the innovation process did not primarily depend on how the process was carried out, but more on who was involved in the process. Through the various workshops that were held, it turned out that it was possible to work with the innovation process if people with a mandate for change were involved, regardless of the work process, but the opposite was not possible—i.e. it was not possible to drive a good innovation process unless the “right people” were involved. The working group felt that an early step was missing that would have ensured that the right participants were involved in the process at the right time. What was needed were people who have the capacity to make appropriate analyses, people who come up with innovative solutions, and people who have the mandate to implement changes. This means that there may need to be different people involved in different phases of the systemic design process. There seems to be a need to ensure this at an initial stage.

It is important to see in which step the patient cannot be involved, because they may not understand the system concept.

In the work with Care at Home, new individuals were therefore invited so that the “right participants” would be involved. The process received support from both economists and lawyers in different phases. In other phases, additional professions were invited to develop solutions. However, participants with a greater mandate for change were, to a greater extent, asked to participate and make decisions on systemic changes.

In processes like this, the people who have the change mandate need to be involved, and it is difficult to get those people involved, as we are talking about politicians and senior officials.

In order to include these people, a great deal of focus was then needed on ensuring that everyone involved understood the “why we are doing this” before working on the “how to do it.” The experience showed that many of those involved had not accepted the “why,” and therefore felt a more or less explicit resistance to working with the question of “how” to do it. In order to succeed in this, the working group saw that what was needed was to recruit dialogue-oriented process managers who could create trusting relationships. It is very important that there is trust among people who represent different organizations, and among people who need to understand each other’s perspectives and cooperate for a common good. It therefore became very important to establish good individual relationships in the development team.

It is easy to perform a common analysis, but then when you have to get into the actual “doing” and changes in your business and structure, then we are so incredibly stuck in these organisational challenges.

Therefore, an initial step was added to Jones et al. (Citation2018) model:

Plan to ensure that the right people to participate in the process, including (often different people) with the following important competencies: (a) the experience from the need owners, (b) the capacity to generate ideas for innovative solutions, and (c) the mandate to change the system. Also ensure that the innovation management process is led by a dialogue-oriented process manager.

As the work continued to apply Jones et al. (Citation2018) process model, the working group saw that by “listening to the system,” there were many identified needs and it was difficult to delimit which system dimensions it was appropriate to focus on. The group saw that a consequence of this was that the process tended to get stuck at the initial stages. The group became stuck in listening to the system, and the energy of the participants ran out during the analysis process. There was then no energy left to the later stages, i.e. arrive at the development of new solutions.

It is possible that the mapping phase was too large and too deep, which meant that it took too long and that we got stuck in the needs mapping, and did not get as far as we should have with the change process itself.

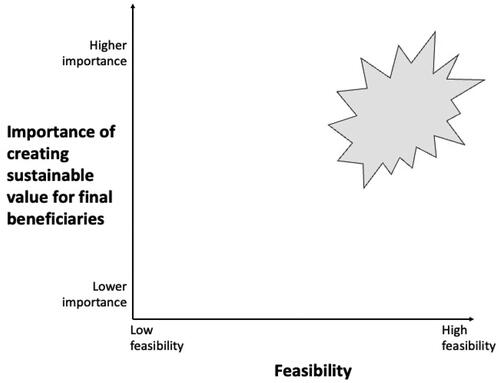

Therefore, the working group realized that another step could be suggested early in the process that would provide support for sorting through all the innovation needs that were identified. The group realized that the process would benefit from identifying and prioritizing identified needs based on the importance for creating sustainable value for final beneficiaries, in combination with feasibility. This was done based on the matrix presented in .

Figure 5. A Matrix to support prioritization among identified needs. Identified needs placed in the upper right corner, the “hot spotarea”, are appropriate needs to take further in the systemic design process.

Therefore, after the third step in the model developed by Jones et al. (Citation2018), (understanding the system) the group inserted a new step:

Prioritize among identified needs.

After working with Jones et al. (Citation2018) fourth and fifth steps of “Defining the desired future” and “exploring the possibility spaces,” the working group saw that it was actually the most challenging thing that lay ahead—i.e. to really bring about change. The feeling was that the focus of Jones et al.’s model was on analysis, but not on driving the innovative development process itself. There was a lack of structure to generate ideas, to develop or to drive implementation of new solutions to address the identified needs. These steps were also perceived to be significantly more time and resource-consuming and more difficult to operate than the initial analysis steps.

Therefore, the working group saw that there was a great development potential in strengthening the solution and implementation phases in Jones et al. (Citation2018) model. It was seen that the group needed to work deeply with the radical development of organizational structures and cultures, which came to be described as a paradox: the group had to leave the perspective of the individual patient to overcome the structural and cultural challenges in order to improve care for the patient.

One must start with an idea of how to run system issues, and of what is in the gap between organisations. And then you can also add methodology and insights from the design thinking methodology.

In the work to develop proposed solutions, the relationship between the individual and the organizational system-complex dimensions was emphasized, and a working method for elaborating proposed solutions that would keep both dimensions in mind at the same time was needed.

It’s a bit like balancing different perspectives. Reality is so complex that we have to be able to do this. There is always a system perspective and there is always a user perspective.

The group therefore replaced Jones et al. (Citation2018) final two steps—designing the invention model and fostering the transition—with the following five new steps:

Generating ideas.

Creating a prototype.

Identifying key stakeholders.

Planning and testing.

Implementing systemic change.

Thus, a new twelve-step process flow model was created.

In the continued work with the innovation management model, a more limited working group for Palliative Care at Home was formed. Early in the process, the Palliative Care at Home working group initiated a clear focus on creating good relationships within the group, which meant that participants got to know each other and understood each other’s different perspectives. The project group met often—at least twice per week. The group managed to get senior officials involved in the process, and also invited a mother who had lost her son to cancer and had a lot of experience of palliative care at home. This was to respond to the new first step (Plan to ensure that the right people to participate in the process) to ensure that the right people were involved in the process, but also to ensure that the work was permeated by good personal relationships, which were felt to be more important than how the process model was designed, in order to achieve a good innovation climate.

I joined this project because I knew all about the solution, and I had a clear vision of how we were going to solve this. Now that I have listened to all the professions represented in this group, I have acquired a much wider understanding and see completely different answers to our common challenges. This was very important.

The new limited working group for Palliative Care at Home also started working with the twelve-step process model in a different way. The twelve steps began to be used more flexibly and more as different tools in a toolbox than following a predetermined process flow. Some tools were used over and over again to solve certain challenges, whilst in some cases, other tools were barely used at all.

5. Discussion

Combining design and systems theory has previously been described as a strength in public sector innovation. However, it seems to be a challenge to create a functioning amalgamation in integrating the genuine needs of citizens’ everyday lives within a development process targeting system challenges. It seems that innovation management in the public sector increasingly needs to start from the individual’s experiences and see what generates value for the citizen, but also needs to develop innovative solutions at the system level in an often complex societal structure. In recent years, methods and routines have been developed that start with the individual citizen and design practices to increase the value for the citizens. But if innovation processes are to contribute to managing the extensive system-complex societal challenges, it is not enough to create solutions that only apply in the context close to the citizens. The innovation processes must identify the system challenges, and enlist human resources that understand the needs, can contribute with new perspectives and also possess the mandate to make systemic changes. This can often mean that one need to involve different people in different phases. It is therefore important to be able to drive innovation processes from both a micro and a macro perspective—i.e. by combining systems perspective and design practice. In order to succeed in this, this study indicates that it is more important to involve the right people in an innovation process in different phases than to follow a specific process model. This can be summed up like that you can have the right people but the wrong process and still get far in the innovation process, but not the other way around.

The results of this study show that starting from a fixed process model is not necessarily a success factor. It is instead more appropriate to create an innovation process-management toolbox from which different tools can be used depending on the situation and needs in different phases. This box could consist of the steps proposed by Jones et al. (Citation2018) in combination with the complementary process steps that we developed in this study. Furthermore, the results of the study presented in this article are in line with previous researchers (e.g. Buchanan Citation2019; Jones et al. Citation2018), insofar as there is a logic in using the tools in a certain order, but this article also emphasizes the need to be flexible with the different process tools and to be open to moving back and forth between different tools in the twelve-tools model (see the process pathway in ).

Jones et al. (Citation2018) model () illustrates that different steps are connected to systems theory while other steps are connected to design theory. The results of this study point more to the need to include the system level in all steps and at the same time start from the perspective of the individual beneficiary and consider the increase in value for them. This means that it is an advantage not to link different steps to systems or design perspectives, but to seek to work in parallel with both system and design perspectives in all steps. An example of how this can be done is to start from a persona who represents beneficiaries already in the early stages, for example "listening to the system" and based on this individual persona’s perspective identify system components. This then becomes an example of using a classic design method to create system understanding.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this article was to shed light on the integration of design and system-thinking approaches in practice, and thereby contribute to increased opportunities for researchers and practitioners to find solutions to pressing societal problems. The article has responded to that aim by highlighting important lessons from a practical case, and identifying certain factors that create enabling conditions that will allow the strength (previously identified by other scholars) of combining design and systems theory to be concretized as an innovation management tool box.

The study behind this article identified the potential to build upon and further develop the innovation management model presented by Jones et al. (Citation2018). This study develops their model into a toolbox consisting of 12 innovation management tools (see ). We believe that it is a pedagogical point to present as many as 12 tools on the journey from need to solution. It shows that it is a laborious process that includes many important decisions along the way, and it would be a mistake to believe that there is a quick fix to go from a need to an implemented system change.

This study is based on empirical data from a collaborative project for increased quality of care. The empirical context can be seen as an example of a complex collaborative project between different stakeholders who do not have mandate to make decisions over each other but at the same time have a common overall goal and a need work together to deliver important societal services. We believe that the results of this study can be applied in many similar contexts and processes working with complex societal development processes.

Continued research needs to be conducted regarding whether and how this toolbox can be used within various societal sectors in order to increase innovation management.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (27.5 KB)Acknowledgements

This research has been partly sponsored by the Region Uppsala public authority. These interests have been fully disclosed to Taylor & Francis. The research has no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bason, C. 2014. Design for Policy. London: Routledge.

- Blomkamp, E. 2022. “Systemic Design Practice for Participatory Policymaking.” Policy Design and Practice 5 (1): 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1887576.

- Buchanan, R. 2019. “Systems Thinking and Design Thinking: The Search for Principles in the World We Are Making.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 5 (2): 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.04.001.

- Chevalier, J. M., and D. J. Buckles. 2013. Handbook for Participatory Action Research, Planning and Evaluation, 155. Ottawa: SAS2 Dialogue.

- Clarke, A., and J. Craft. 2019. “The Twin Faces of Public Sector Design.” Governance 35: 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12342.

- Howlett, M. 2020. “Challenges in Applying Design Thinking to Public Policy: Dealing with the Varieties of Policy Formulation and Their Vicissitudes.” Policy & Politics 48 (1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15613699681219.

- Gianelloni, S., and M. H. Goldstein. 2020. “Modelling the Design Systems Thinking Paradigm.” ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, 2020-June, [1025]. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2–34981.

- Jones, P. 2014. Design for Care: Innovating Healthcare Experience. New York: Rosenfeld Media, LLC.

- Jones, P. 2018. “Contexts of Co-Creation: Designing with System Stakeholders.” In Systemic Design, 3–52. Japan: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55639-8_1.

- Jones, P. H., S. Monastiridis, S. Ryan, V. Toye, K. Van Ael, and P. Vandenbroeck. 2018. “State of the Art Practice: Are We Ready for Systemic Design Toolkits?.” Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design (RSD7) 2018 Symposium. Turin, Italy, October 24–26, 2018.

- Kaufman, R., and D. Brethower. 2019. “Are Design Thinking and System Thinking and Planning Really Different? And Are They Both Missing a Critical Focus?” Performance Improvement 58 (10): 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21899.

- Kimbell, L. 2016, June 27–30. Design in the Time of Policy Problems [Paper presentation].

- Kimbell, L., and P. E. Street. 2009, September. Beyond Design Thinking: Design-as-Practice and Designs-in-Practice [Paper Presentation]. CRESC Conference, Manchester.

- Kimbell, L., and J. Bailey. 2017. “Prototyping and the New Spirit of Policy-Making.” CoDesign 13 (3), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003.

- Komatsu, T., M. Salgado, A. Deserti, and F. Rizzo. 2021. “Policy Labs Challenges in the Public Sector: The Value of Design for More Responsive Organizations.” Policy Design and Practice 4 (2): 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1917173.

- Lewis, J. M., M. McGann, and E. Blomkamp. 2020. “When Design Meets Power: Design Thinking, Public Sector Innovation, and the Politics of Policymaking.” Policy & Politics 48 (1): 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15579230420081.

- Lynch, M., G. Andersson, F. R. Johansen, and P. Lindgren. 2021, September 16–17. Entangling Corporate Innovation, Systems Thinking and Design Thinking [Paper Presentation]. 16th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Online. https://doi.org/10.34190/EIE.21.117.

- McGann, M., J. M. Lewis, and E. Blomkamp. 2018. Mapping public sector innovation units in Australia and New Zealand: 2018 Survey Report. The Policy Lab. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2018-04/apo-nid181376.pdf

- Mugadza, G., and R. Marcus. 2019. “A Systems Thinking and Design Thinking Approach to Leadership.” Expert Journal of Business and Management 7 (1): 1–10. https://business.expertjournals.com/23446781-701/.

- Pourdehnad, J., D. Wilson, and E. Wexler. 2011. “Systems & Design Thinking: A Conceptual Framework for Their Integration.” Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the ISSS – 2011, Hull, UK, 55(1). https://journals.isss.org/index.php/proceedings55th/article/view/1650.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2013. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Sangiorgi, D. & Prendiville, A. (Eds.). 2017. Designing for Service: Key Issues and New Directions. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sevaldson, B. 2011. “GIGA-Mapping: Visualisation for Complexity and Systems Thinking in Design.” Nordes 2011: Making Design Matter. https://doi.org/10.21606/nordes.2011.015.

- Sevaldson, B. 2019. “What is Systemic Design? Practices beyond Analyses and Modeling.” Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design (RSD8) 2019 Symposium, Oct 13-15 2019, Chicago, USA. http://openrewsearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/3233

- Starostka, J., A. de Götzen, and N. Morelli. 2022. “Design Thinking in the Public Sector – A Case Study of Three Danish Municipalities.” Policy Design and Practice 5 (4): 504–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2022.2144817.

- Stringer, E. T. 2014. Action Research, 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Torfing, J., E. Sørensen, and A. Røiseland. 2019. “Transforming the Public Sector into an Arena for Co-Creation: Barriers, Drivers, Benefits, and Ways Forward.” Administration & Society 51 (5): 795–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716680057.

- Villa Alvarez, D. P., V. Auricchio, and M. Mortati. 2022. “Mapping Design Activities and Methods of Public Sector Innovation Units through the Policy Cycle Model.” Policy Sciences 55 (1): 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-022-09448-4.