ABSTRACT

A scoping review was conducted, analyzing peer-reviewed literature published between 1995 and 2022, focusing on school stakeholders' perceptions of K-12 health education (HE) in Canada. The results included 37 studies, with articles focused on the perceptions of students, in-service and pre-service teachers, parents, undergraduate students, and health partners/ educational professionals. Using reflexive thematic analysis, three main themes were identified: (a) HE is perceived as a valuable school subject; (b) teachers are not prepared to teach HE; and (c) HE courses are not meeting the needs of students. The outcomes of the review underscore the importance and value of HE as perceived by school stakeholders and highlight the necessity for heightened advocacy efforts to enhance HE at all school levels. The review emphasizes the need for broader consultation and research involving diverse school stakeholder groups in order to promote the advancement of HE in Canadian schools.

Introduction

The delivery of school-based health education (HE) can serve as a foundation for students’ wholistic wellbeing and may have a direct influence on fostering positive health outcomes while preventing adverse ones (Auld et al., Citation2020; Pulimeno et al., Citation2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined HE as ‘a combination of learning experiences designed to help individuals to improve their health by increasing their knowledge or influencing their attitudes’ (Kumar & Preetha, Citation2012, p. 6). This definition is supported by the national association Physical and Health Education Canada (PHE Canada). PHE Canada recently developed the Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies (CPHEC; Davis et al., Citation2023) to provide provinces the curriculum competencies and outcomes necessary for quality school-based HE. The CPHEC describe HE as a wholistic course of study that empowers students to balance, connect, and maintain their emotional, physical, cultural, spiritual, social, and psychological wellbeing. HE, as proposed by Davis et al. (Citation2023), places emphasis on enabling students to acquire the necessary skills, knowledge, and motivation to be healthy and aware, affirmed and connected, and active for their lifetime.

HE is critically important to the health of children and youth, and the continued wellbeing of future generations (Auld et al., Citation2020; Pulimeno et al., Citation2020). Auld et al. (Citation2020) and Nutbeam et al. (Citation2018) have argued that HE offers a means for improving health literacy – the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health for themselves, their families, and their communities. The WHO (Citation2008) suggests health literacy should be incorporated in all schools’ core curricula. Furthermore, schools offer children with diverse backgrounds the opportunity to develop health behaviours, ensuring that they receive equal support, attention, and opportunities (Davis et al., Citation2023). Coupled with HE affording all students access to information and resources, HE is the only school subject with learning opportunities on some critical topics, such as mental health support and stigma, sexual HE (SHE), social and emotional competencies, and topics associated with equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Despite its significance, HE has historically struggled to secure its position as a vital area of study in schools (Auld et al., Citation2020; Sinkinson & Burrows, Citation2011). Moreover, some have viewed HE as ‘contentious’ (Munro, Citation2003; Weaver et al., Citation2002), a ‘low-status’ subject (Sinkinson & Burrows, Citation2011), and/ or a ‘panacea that will transform the health of individual, community, and even nations’ (Leahy et al., Citation2016, p. 1). HE topics often spark debate, leading to a range of complex issues concerning the rights of students, parents, and governing bodies (Sinkinson & Burrows, Citation2011). SHE, for example, is a topic that is frequently discussed both within the education sector and the broader political arena (Rayside, Citation2014; Robinson et al., Citation2019). Other topics, such as mental health and gender identity, have also been considered controversial by some school stakeholders due to the perceived intrusion into the home and parental domain (Sinkinson & Burrows, Citation2011).

The implementation of quality and meaningful HE in K–12 schools remains an ongoing challenge (Auld et al., Citation2020; Lu & McLean, Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2023). Within Canada, there are no national or provincial guidelines mandating specific HE training for teachers (Vamos & Zhou, Citation2009). Consequently, HE is typically delivered by teachers who hold expertise in other subject areas or disciplines, rather than specialized training in HE (Birch et al., Citation2019). Insufficient formal training in HE leads to teacher frustration and a notable lack in confidence when navigating sensitive topics within the subject (Cohen et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Robinson et al., Citation2019). Due to the often-narrow focus of school priorities (e.g. literacy and numeracy), along with curricula time devoted to other subjects (Robinson et al., Citation2023; Videto & Dake, Citation2019), there is a lack of coherent understanding of, and value towards, Canadian HE programming. Robinson et al. (Citation2023), in their analysis of Canadian HE curricula, reported variations of instructional time allocations across provinces ranging from 2 to 8% of total instructional time, with limited senior secondary requirements. With such minimal instructional time, it is fair that some suggest that HE may have little to no impact on student health. In terms of structure, across Canadian provinces and territories, HE is offered both as an independent subject and as part of a combined health and physical education curriculum (i.e. British Columbia/Yukon, Manitoba, Ontario and Québec have combined physical education and HE). Notably, nearly all provinces and territories in Canada have distinct HE curricula, with two territories adopting the curricula of their neighboring provinces or territories (Robinson et al., Citation2023). Robinson et al. (Citation2023) concluded their analysis of HE curricula in Canada by asserting the importance of ‘a coordinated, inclusive, and unified voice for HE’ (Robinson et al., Citation2023, p. 18) to establish it as a priority across the country. This includes students, teachers, postsecondary teacher educators, parents, health experts, cultural knowledge keepers, Indigenous Elders, as well as provincial and national partners (Robinson et al., Citation2023).

To accomplish this goal, it is imperative to gain an understanding of K–12 HE across Canada from the perspectives of school stakeholders. By attending to the voices of school stakeholders, we can identify more effective strategies and supports for those looking to create more positive HE for all involved. Seeking an understanding of the HE-related perceptions of multiple school stakeholders has become a commonplace occurrence for many who are engaged in curriculum development or reform efforts (Ingman et al., Citation2017), as well as educational policy advancement (Stosich & Bae, Citation2018). We can learn from school stakeholders, and we can apply that learning to current and future teaching and research related to HE. As such, the purpose of this scoping review was to synthesize the evidence gathered from empirical literature focused on school stakeholders’ perceptions of K–12 HE in Canada. Specifically, we aimed to: (a) canvass the existing literature in the field to determine the volume, nature, and characteristics of the research available; (b) summarize main findings from this area of research to identify action areas to build a stronger K–12 HE system; and (c) identify potential gaps in our understanding of school stakeholders’ perceptions of K–12 HE in Canada, to inform future directions and research. The primary objective of this review was to transform these findings into practical strategies that can have a positive impact on school-based HE.

Methods

Given the nature of the research objectives, we conducted a scoping review guided by the methodological framework by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). Scoping reviews aim to assess the breadth and extent of existing evidence or literature pertaining to a specific topic and they are conducted to summarize and share a range of research findings for policy makers, practitioners, and consumers who may not have the time or resources to complete the review themselves (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Given that the focus of the review includes this target audience, and the aims are focused on accessing available literature and identifying gaps for future research, this type of review is well-suited. Following Arksey and O’Malley’s staged framework, we adopted the following five-stage scoping review protocol: (1) identify the research question, typically broad in scope; (2) identify relevant studies through a comprehensive process; (3) select studies by establishing inclusion/ exclusion criteria based on familiarity with the literature; (4) chart the data, involving the sifting, charting, and sorting of information based on key issues and themes; and (5) collate, summarize, and report the results, encompassing both descriptive and numerical summaries of the data and a thematic analysis.

Identifying relevant studies

Following the recommendations offered by The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI, Citation2015), two librarians (authors: Johnston and Frail) collaborated with the lead author (Sulz) to identify appropriate search terms. Johnston and Frail then created search strategies for, and conducted searches in, the following databases from database inception until August 12, 2022: Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Education Research Complete (both via EBSCOhost), Education Database and Canadian Business and Current Affairs (CBCA): Social Sciences Subset (both via ProQuest), and Scopus.

The search contained subject headings and free text search terms for four concepts: (a) stakeholder perceptions; (b) health curricula; (c) K–12 education; and (d) Canadian school systems. The search strategies were adapted for each database for optimal performance. (See details for the full search for ERIC in Appendix A.) All types of literature were included in the searches, and no language or methodological limits were applied to the searches, with the exception of excluding results for newswire feeds, magazines, and encyclopedias and reference works in CBCA: Social Sciences.

Study selection: inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, the studies and documents must have included: (a) at least one topic related to health curricula; (b) the K–12 education context; (c) Canadian education systems; (d) a copyright date or publication date between 1995 and 2022 (the start date was chosen as earlier publications would be referring to obsolete curricula); and (e) peer-reviewed journals. An article was excluded if it: (a) did not include a topic related to health curricula; (b) focused on pre-schools or post-secondary education contexts; (c) included a school system outside of Canada; (d) had a publication date prior to 1995; (e) was not considered peer-reviewed research; and/ or (f) was written in a language other than English.

Articles identified during the search were imported into Covidence, a web-based platform used to facilitate screening and data extraction for scoping and systematic reviews. The review consisted of two levels: a review of the title and abstract and a review of the full-text. Articles were first screened by the lead author according to titles and abstracts to determine which studies addressed the research question. When an article was deemed to meet the eligibility criteria, it was downloaded and saved for a comprehensive review of the full text by two separate researchers. Two researchers then screened full text articles for consensus.

Interpretation, synthesis, and reporting

The information was charted using the database program Excel by one author and confirmed by a second author, using the following categories: (a) author, year, province; (b) journal; (c) study design and participants; (d) goal or purpose of the study; and (e) notable results. Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) emphasize the importance of offering a descriptive numerical summary, advocating that researchers should delineate the features of incorporated studies. This includes detailing the overall number of studies included, types of study design, publication years, interventions’ types, characteristics of the study populations, and the countries where the studies were conducted. Upon review of the charted information, two additional groups were created: school stakeholder groups (e.g. student, parent) and HE topic studied (e.g. SHE, teacher preparation). The reporting of these insights emerged during the charting process with links to the goal and purpose of the study.

Following this, we performed a thematic analysis, categorizing our data into overarching themes. Our methodology aligned with Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) step 5 of collating, summarizing, and reporting the results and Levac et al.’s (Citation2010) suggestion to integrate a stage resembling qualitative data techniques, particularly employing thematic analysis. The presentation of our results included a combination of tables and descriptions corresponding to the identified themes. This approach established a clear link between our findings and the fulfillment of our research objectives (Daudt et al., Citation2013).

Results

Search outcome

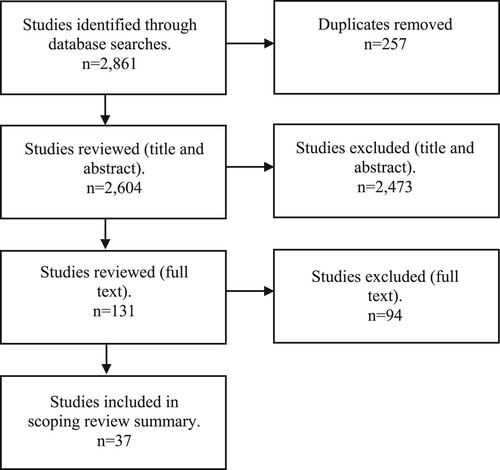

A total of 2,861 articles were identified through the initial search. Covidence identified 257 duplicates, leaving 2,604 results for the title and abstract screening phase. In total, 131 papers were full-text reviewed (2,473 ineligible/ irrelevant) using the identified inclusion/ exclusion criteria. The full review of 131 papers was completed by the lead author (Sulz) and a second co-author (Robinson) resulting in the exclusion of 94 more articles. The final scoping review included 37 articles. The review process is summarized in .

Characteristics of included studies

All included studies were published in peer-reviewed journals between 1998 and 2022. From the 37 studies, seven of the ten Canadian provinces were represented in the data: Ontario (n = 15); New Brunswick (n = 6); British Columbia (n = 6); Alberta (n = 5); Québec (n = 2), Nova Scotia (n = 1); and Newfoundland and Labrador (n = 1). The data did not include representation from any of the three Canadian territories. Summaries of the 37 studies for this research are found in (supplementary materials).

Table 1. Perceptions of School Stakeholders on K–12 HE.

Description of the stakeholder groups

Six school stakeholder groups were the focus of the studies within this review: (a) students and young adults (kindergarten to 25 years old; n = 18); (b) in-service teachers (n = 13); (c) parents (n = 8); (d) health partners/ educational professionals (e.g. public health agencies, faculties of education, provincial organizations; n = 6); (e) pre-service teachers (i.e. Bachelor of Education [BEd] students; n = 4); and (f) undergraduate students (n = 3). Some of the studies within this review focused on the perspectives from one stakeholder group, while others sought the perspectives from multiple stakeholder groups. The four conceptual/ theoretical publications did not include research data but, instead, offered reasoned discussions and arguments related to different stakeholders.

Description of HE topics

Given the primary objective of this review was to understand the viewpoints of school stakeholders in relation to K–12 HE, it is important to consider the specific topics that studies focused on when seeking stakeholders’ perceptions. From the 37 studies, five HE topics were explored: (a) SHE (n = 26); (b) health/ health promotion/ health literacy (n = 5); (c) teacher preparation (n = 3); (d) financial literacy (n = 2); and (e) teacher experiences (n = 1). The detailed results of the topic studied by school stakeholder group are presented in .

Table 2. Topic studied by school stakeholder group.

Description of study designs

The reviewed studies employed five different methods in terms of study design: (a) quantitative (descriptive/ correlational; n = 21); (b) general qualitative (n = 10); (c) conceptual/ theoretical manuscripts (n = 4); (d) qualitative case study (n = 1); and (e) qualitative action research (n = 1). The quantitative studies encompassed various stakeholder perspectives and primarily focused on the subject of SHE, with 19 out of the 21 studies addressing this topic. The general qualitative studies focused primarily on students’ perceptions (eight of the 10 studies). All four conceptual/ theoretical manuscripts centred around the topic of SHE. The single case study explored students’ and teachers’ perceptions related to financial literacy, while the sole action research study explored students’ perspectives on health in school settings.

Themes generated from included studies

Using reflexive thematic analysis, three themes were developed that speak to the perspectives of school stakeholders regarding K–12 HE and are presented below, referencing examples from the articles included in the review.

Theme 1: health education is perceived as a valuable school subject

The reviewed articles collectively demonstrate school stakeholders perceive HE as an essential school subject. While stakeholders express dissatisfaction with the quality of HE and their overall experiences with the subject (see Theme 3), they recognize the importance of its content and believe HE should be taught in schools. Students (Byers et al., Citation2003a, Citation2003b), teachers (Cohen et al., Citation2004), and parents (Weaver et al., Citation2002; Wood et al., Citation2021) were in favour of SHE at school and perceived the SHE topics in the curriculum as important. Studies examining parental attitudes related to SHE consistently revealed parental support for the inclusion of SHE, encompassing a wide range of topics, including those deemed ‘controversial’ (e.g. sexual orientation, birth control; McKay et al., Citation1998; Weaver et al., Citation2002; Wood et al., Citation2021). Parents expressed the need for SHE to commence in elementary or middle school (McKay et al., Citation2014; Weaver et al., Citation2002), before the onset of adolescence (McKay et al., Citation2014), and continue through high school (McKay et al., Citation1998, Citation2014; Weaver et al., Citation2002).

Although stakeholders support and value the teaching of SHE in schools, some studies reported students did not receive SHE throughout all grades (Byers et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). For example, Byers et al. (Citation2017) reported that most students received HE in middle school grades but less so in high school grades. Notably, students, teachers, and parents acknowledged the shared responsibility of SHE, involving collaboration between schools and parents (Byers et al., Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Cohen et al., Citation2004; Weaver et al., Citation2002). Lastly, Henderson et al. (Citation2021) highlighted in-service teachers’ perceptions of the importance of financial literacy in HE classroom instruction, citing numerous benefits to the student (e.g. learn to budget, learn the value of money). This theme highlights that while stakeholders’ express support for HE, specifically SHE and financial literacy, there are concerns about its consistent implementation across grades and the importance of school and parent collaboration.

Theme 2: teachers are not prepared to teach health education

Many of the studies highlighted the need for teacher training to ensure teachers are competent, confident, and comfortable teaching topics within HE. Studies reported that pre-service teacher preparation in HE is low and, in many instances, non-existent. This suggests that preparation in HE may not be a priority in pre-service teacher education programs in Canada (Anderson & Thorsen, Citation1998; McKay & Barrett, Citation1999; Vamos & Zhou, Citation2009). Studies assessing the needs of pre-service and in-service teachers described teachers’ uncomfortable feelings about teaching HE and self-perceived gaps of knowledge and skills (Vamos & Zhou, Citation2007, Citation2009). Cohen et al. (Citation2004) reported in-service teachers felt only ‘somewhat’ knowledgeable to teach SHE and most teachers had received no training to teach SHE. This study and others (e.g. Grace, Citation2018; Henderson et al., Citation2021; Lokanc-Diluzio et al., Citation2007; Ninomiya, Citation2010; Russell-Mayhew et al., Citation2016) concluded that teacher training/ professional development in HE is an important and needed component in enhancing the knowledge, skills, and competence to teach HE.

Studies also reported that students perceived their teachers to be uncomfortable (DiCenso et al., Citation2001) and/ or unqualified and lacking motivation to teach HE (Begoray et al., Citation2009). Grace (Citation2018) described SHE as ‘non-education’ as teachers tended to ‘steer away’ from issues in SHE related to sexual and gender minorities and called on faculties of education and school districts to offer courses and continued professional development to prepare teachers to teach SHE. However, Byers et al. (Citation2003a, Citation2003b, Citation2013) found most students perceived their teachers as ‘pretty comfortable’ or ‘very comfortable’ with the topics covered in HE.

Theme 3: health education courses are not meeting the needs of students

Overall, the reviewed articles indicated that students’ needs were not being met in HE courses. When examining students’ perceptions of SHE, approximately a third of middle and high school students rated SHE as fair/ poor (Byers et al., Citation2003a, Citation2003b) or good (Byers et al., Citation2017). Similarly, parents rated the quality of SHE between fair and good (Wood et al., Citation2021). Several factors were identified as impacting the experiences of students within HE courses: (a) repetitive course content to previous grades (Begoray et al., Citation2009; Noon & Arcus, Citation2002); (b) limited time allocated to HE/ rushed curriculum (Noon & Arcus, Citation2002; Walters & Laverty, Citation2022); and (c) ineffective and unengaging teaching methods (e.g. videos, worksheets; Begoray et al., Citation2009; Byers et al., Citation2003a, Citation2017; Noon & Arcus, Citation2002). Students’ suggestions for HE to better meet their needs included extending the duration of course units to allow for more in-depth exploration, incorporating topics that are more relevant to their lives, sequencing content in a way that avoids repetition, offering opportunities for student voice and choice in learning activities, and portraying a more sex-positive approach to SHE (Begoray et al., Citation2009; Byers et al., Citation2003a; Larkin et al., Citation2017; Noon & Arcus, Citation2002; Phillips & Martinez, Citation2010). Furthermore, students have expressed the importance of including topics related to sexual orientation and sexual diversity (McKay et al., Citation2014; Meaney et al., Citation2009; Rye et al., Citation2015; Walters & Laverty, Citation2022). Similarly, undergraduate students reported being dissatisfied with their high school SHE courses and shared they did not learn enough personally relevant information in high school (Rye et al., Citation2015).

Religion and culture emerged as influential factors that negatively affected students’ experiences in HE. Undergraduate students expressed a preference to receive sexual health instruction from an unbiased source. This was particularly true for those students who attended religious high schools, who felt they received biased information in SHE courses (Rye et al., Citation2015). In a similar manner, Muslim youth were less inclined to express interest in learning about sexual health compared to students who identified as having no religion (Causarano et al., Citation2010), and they perceived that certain content in HE courses lacked sensitivity towards the religious and cultural difference of students (Zain Al-Dien, Citation2010). Moreover, within the context of religious and cultural diversity in Canada, parents emphasized the need to respect the diversity of moral beliefs in SHE within their school community (McKay et al., Citation1998, Citation2014).

Discussion

The abovementioned overview of school stakeholders and HE topics, as well as the related themes generated from the 37 articles, offer some possibilities for further contemplation and discussion. Certainly, two obvious possibilities here are the focus upon students (and teachers) as stakeholders and SHE being the most discussed issue within this stakeholder-related literature. In addition to these two topics deserving discussion, the literature also provides some important insight into school stakeholders’ views about the three themes detailed above. And while such stakeholders include many potential people, the literature here provides more insights into the views of students (and teachers) than any other groups. This student and teacher data has the potential to inform HE within similar Canadian (or Western) contexts. We can also offer some suggestions related to the relative shortage of some stakeholders’ perspectives. Accordingly, herein we offer a discussion of these interrelated and important topics/ issues.

Those tasked with curriculum development/ reform and/ or policy advancement might attend to this stakeholder ‘input.’ Amongst other insights, they would find that students and teachers place high value on HE and are wanting it to be offered in most-or-all years of schooling. Differences exist in the HE course requirements among Canada’s provinces and territories, notably with three (Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia) having no HE requirements in senior high school (grades 10–12) (Robinson et al., Citation2023). Considering that the CPHEC incorporates competencies and outcomes for all grades, including senior high school, provincial/territorial ministry might consider integrating the national competencies during future HE curriculum revisions. This approach would help move towards the provision of quality HE to all students throughout their schooling years (Robinson et al., Citation2023). Students have also been able to explain what was missing from their instruction, just as teachers have been able to describe what was missing from their teacher training programs. Parental input is largely absent (save for SHE-related topics), and input from health partners/ educational professionals is relatively limited. So, we would suggest those with an interest in HE teaching and learning contemplate this existing stakeholder data. And researchers with this same interest ought to consider engaging with some of those school stakeholders whose insights are limited in this literature, namely parents and health partners/ educational professionals.

Contemporary Canadian HE curricula have multiple topics or units of instruction (Lu & McLean, Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2023). Yet, a gross majority of the literature reviewed here (i.e. 26 of 37) focused exclusively upon one topic: SHE. And all four conceptual/ theoretical papers focused solely upon SHE – with all authors advocating for students’ rights to access it without parental ‘meddling’ (e.g. by enabling parents to have their children ‘opt out’ of classes which focus upon SHE). That this topic generates more attention than all others combined is in some ways not altogether surprising. Indeed, SHE provides more opportunities for opposition than do any other HE topics – from both conservative populists and moral pluralists (Bialystok, Citation2018; Bialystok et al., Citation2020).

The almost singular focus upon SHE has come at the expense of similar research focusing upon other important HE topics. Other than financial literacy and the much more general health/ health promotion/ health literacy, no other topics have been a central focus in any of these 37 publications. The consequence here, of course, is that although we have plenty of stakeholder input related to SHE within HE (and some input into financial literacy within HE), we have no mention of any other ‘staple’ HE topics – such as personal health, career and life choices, safety and injury prevention, and substance misuse and prevention (Lu & McLean, Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2023). So, while those whose research interests focus upon SHE may continue with studies like those reviewed here, we suggest that HE researchers and pedagogues might broaden their view to invite and understand stakeholders’ perspectives related to the other 95% of HE curricula.

Notwithstanding the abovementioned contentiousness of SHE, amongst all stakeholder groups there was wholesale agreement about the importance and value of quality HE, particularly with respect to how HE contributes to students’ health literacy and school communities’ health promotion. Students and teachers have provided insight into the perceived value and importance of HE, as well as some ongoing issues with its curriculum (delivery). Yet, despite plenty of stakeholder support for quality HE (e.g. see Begoray et al., Citation2009; Grace, Citation2018; Laverty et al., Citation2021; McKay et al., Citation1998, Citation2014; Weaver et al., Citation2002), HE remains a marginalized subject in many school communities (Auld et al., Citation2020; Lu & McLean, Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2023). This body of stakeholder literature finds students and teachers as advocates for quality HE – while the subject faces challenges related to limited core course offerings, inadequate instructional time allocations, and the availability of few-if-any ‘qualified’ HE specialists (Auld et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2023). We believe this stakeholder research offers support to those advocating for more core course offerings, instructional time, and HE specialists. It is difficult and careless, we believe, to ignore the views of students and teachers who suggest quality HE is important.

Although all stakeholders believed HE to be an especially important subject, many teachers felt under-prepared to effectively teach it (this finding was especially pronounced, unsurprisingly, for SHE). Research studies that made this point about ill-preparedness came from multiple stakeholders, including pre-service and in-service teachers themselves, as well as from pre-service teacher education program personnel (Anderson & Thorsen, Citation1998; McKay & Barrett, Citation1999; Vamos & Zhou, Citation2007). This presents an obvious cause for concern.

Across the nation, every province enjoys full autonomy with respect to teacher education (e.g. related to qualifications, licensure). So, teachers within each province do not have the same HE-related training (opportunities) as one another. That is, there is no ‘national standard’ of any sort. And so, it is difficult to fully understand teachers’ struggles teaching HE without first gaining a sense of the teacher education available or required in all of Canada’s teacher education programs. On this, there is limited available literature. In the few provinces which offer physical education and HE as one subject (i.e. British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec), elementary and secondary specialization is commonplace (Hickson et al., Citation2012; Kilborn et al., Citation2016). This elementary and secondary specialization is also commonplace within all other provinces which offer physical education as a ‘stand-alone’ course. However, the same high standard is not the case within HE. So, that the teacher stakeholders shared that they felt ill-prepared to teach HE presents little surprise; there is good chance they had little formal teacher training in HE.

Most teacher education programs do not require pre-service elementary teachers to complete a HE course, and they generally do not offer HE as an elementary or secondary specialization. Though this is the case, there is a paucity of literature related to this. Indeed, since Marshall’s (Citation1966) cross-Canada study found that only five of 143 (participating) teacher education programs allowed teachers to specialize in HE, the few similar studies have had narrow foci placed upon lone provinces or university programs (Anderson & Thorsen, Citation1998; Vamos & Zhou, Citation2007). Consequently, this is an area requiring immediate attention within the research community. A summary and review of HE across Canada would prove to be both informative and instrumental. That information would help us all connect some dots between teachers believing that HE is important while at the same time feeling unprepared to teach it themselves. We join others (like Veugelers & Schwartz, Citation2010) in calling for universities’ teacher education programs to require anyone who will be teaching HE to take some mandatory coursework in the disciplinary area.

Clearly, the observation that teachers themselves feel ill-prepared to teach HE partly explains this related finding that HE courses are not meeting the needs of their students. Undoubtedly, limited pre-service teacher coursework (or, more likely, no coursework) would have disquieting consequences on what was taught in HE and/ or on how it was taught. Students who found teachers relying upon ineffective and unengaging videos and worksheets (Byers et al., Citation2003a, Citation2017; Noon & Arcus, Citation2002) may have been finding themselves in classes taught by untrained HE teachers.

However, some concerns expressed by stakeholders placed the blame on things other than those teaching HE: the repetitive content (i.e. the curriculum) and limited time to learn and engage with HE content (Begoray et al., Citation2009; Noon & Arcus, Citation2002; Walters & Laverty, Citation2022). Attention might be placed on these two observations. First, those engaged in curriculum development and/ or reform and those engaged in curriculum studies and/ or inquiry might (re)consider existing HE curricula in light of these stakeholders’ concerns and complaints about repetitive content. It is possible that such (re)considerations might occur alongside Canada’s newly released (and first) national CPHEC (Davis et al., Citation2023). While the CPHEC offers an opportunity to address the aforementioned issues with HE, a challenge lies in the fact that CPHEC is not a mandatory national curriculum. Consequently, individual provinces and territories have the discretion to decide whether they engage with or consider this document in curriculum development and/ or reform. Also, attention must be placed upon the instructional time afforded to HE in all provinces. Certainly, teachers, administrators, government officials, and university researchers should see (or find) fault with limited instructional time for HE – and then do something about it.

Conclusion

A critical takeaway from this review is the consensus among stakeholders regarding the importance and value of quality HE. Collective agreement provides a promising foundation for the subject, but it is imperative to acknowledge the challenges that remain in fully realizing this vision, particularly in terms of teacher training and professional development, instructional time, and student experience. Ensuring that teachers are adequately equipped and confident in their ability to teach HE not only empowers them, but also holds the potential to better align their teaching with the educational needs of students within HE classrooms. We recommend that future research investigate teacher education programs and assess the level of preparation teachers currently receive concerning HE instruction. Furthermore, the studies in this review focused primarily on SHE, leaving a noticeable gap in our understanding of other crucial HE topics. To address the landscape of health education comprehensively, future research must expand its focus beyond SHE and encompass a broader spectrum of topics. Additionally, our exploration of school stakeholders’ perspectives should extend beyond those of students, in-service teachers, and parents. It is imperative that we also examine the viewpoints of key decision makers in the education community, including school administrators, district leaders, and government officials. Understanding their perceptions and how their views shape critical decisions, such as resource allocation, the perceived value attributed to HE, and the allocation of curriculum time for HE, stands as a pivotal step toward meaningful and quality HE.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lauren Sulz

Lauren Sulz is an associate professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Alberta. She is a co-founder of the Healthy Schools Lab which aims to create a whole-school environment where student health is an essential foundation for schools’ core mission of learning. Her research includes comprehensive school health; physical and health literacy; school sport; whole-child education; and health and physical education pedagogy.

Daniel B. Robinson

Daniel B. Robinson is professor in physical education and sport pedagogy at St. Francis Xavier University. He is also Chair of the Department of Curriculum and Leadership and Coordinator of the PhD in Educational Studies Program. His current research focuses upon the following: culturally relevant pedagogy; inclusive and adapted physical education, physical activity, and sport; physical literacy; and school communities’ health promotion programming.

Hayley Morrison

Hayley Morrison is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Alberta. Her research areas include inclusive/adaptive physical education, health and physical education teacher education, and professional development to ensure educative and inclusive health and physical education experiences for all individuals.

Josh Read

Josh Read is a secondary school physical education and science teacher with a passion for student well-being. Josh completed his BEd in 2022 and worked in the non-for-profit sector at Physical and Health Education Canada before starting his career in teaching. Josh brings his academic and sporting background into his classroom by creating active learning environments that amplify student voice and choice.

Ashley Johnson

Ashley Johnson is a PhD Candidate in the Community-Engaged Health Promotion Research Lab within the School of Kinesiology and Health Studies at Queen’s University. Concurrently, she holds a position as a research assistant for the Healthy Schools Lab at the University of Alberta. Ashley's research is focused on understanding how a community health promotion partnership can be successful and sustainable in the Canadian context.

Lucinda Johnston

Lucinda Johnston is a Faculty Engagement Librarian at the University of Alberta, and supports research for the departments of Music, Drama, Linguistics, Philosophy and the Faculty of Education. She is the President of the Canadian Association for Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres, and her research interests include library outreach, Indigenizing and decolonizing library instruction, music publishing, and sound as knowledge.

Kim Frail

Kim Frail is Head, Library Teaching and Learning at the University of Alberta. She has worked at UofA Library for two decades in a variety of roles, most recently as a subject librarian supporting the Faculty of Education. Her research interests include: the integration of library services in campus learning management systems and the impact of library teaching on academic performance and student retention.

References

- Anderson, A., & Thorsen, E. (1998). Pre-service teacher education in health education: An Ontario survey. Journal of Education for Teaching, 24(1), 73–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607479819935

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Auld, M. E., Allen, M. P., Hampton, C., Montes, J. H., Sherry, C., Mickalide, A. D., Logan, R. A., Alvarado-Little, W., & Parson, K. (2020). Health literacy and health education in schools: Collaboration for action. NAM Perspectives, Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine.

- Begoray, D. L., Wharf-Higgins, J., & MacDonald, M. (2009). High school health curriculum and health literacy: Canadian student voices. Global Health Promotion, 16(4), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975909348101

- Bialystok, L. (2018). My child, my choice?” Mandatory curriculum, sex, and the conscience of parents. Educational Theory, 68(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12286

- Bialystok, L. (2019). Ontario teachers’ perceptions of the controversial update to sexual health and human development. Canadian Society for the Study of Education, 42(1), 1–41.

- Bialystok, L., Wright, J., Berzins, T., Guy, C., & Osborne, E. (2020). The appropriation of sex education by conservative populism. Curriculum Inquiry, 50(4), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2020.1809967

- Birch, D. A., Goekler, S., Auld, M. E., Lohrmann, D. K., & Lyde, A. (2019). Quality assurance in teaching k–12 health education: Paving a new path forward. Health Promotion Practice, 20(6), 845–857. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919868167

- Byers, S. E., Hamilton, L. D., & Fisher, B. (2017). Emerging adults’ experiences of middle and high school sexual health education in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Ontario. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 26(3), 186–195. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2017-0006

- Byers, S. E., Sears, H. A., & Foster, L. R. (2013). Factors associated with middle school students’ perceptions of the quality of school-based sexual health education. Sex Education, 13(2), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2012.727083

- Byers, S. E., Sears, H. A., Voyer, S. D., Thurlow, J. L., Cohen, J. N., & Weaver, A. D. (2003a). An adolescent perspective on sexual health education at school and at home: II. Middle school students. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 12(1), 19–33.

- Byers, S. E., Sears, H. A., Voyer, S. D., Thurlow, J. L., Cohen, J. N., & Weaver, A. D. (2003b). An adolescent perspective on sexual health education at school and at home: I. High school students. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 12(1), 1–17.

- Causarano, N., Pole, J. D., Flicker, S., & Toronto Teen Survey Team (2010). Exposure to and desire for sexual health education among urban youth: Associations with religion and other factors. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 19(4), 169–184.

- Cohen, J. N., Byers, E. S., & Sears, H. A. (2012). Factors affecting Canadian teachers’ willingness to teach sexual health education. Sex Education, 12(3), 299–316.

- Cohen, J. N., Byers, S. E., Sears, H. A., & Weaver, A. D. (2004). Sexual health education: Attitudes, knowledge, and comfort of teachers in New Brunswick schools. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13(1), 1–16.

- Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(48), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Davis, M., Gleddie, D. L., Nylen, J., Leidl, R., Toulouse, P., Baker, K., & Gillies, L. (2023). Canadian physical and health education competencies. Physical and Health Education Canada.

- DiCenso, A., Borthwick, V. W., Busca, C. A., Creatura, C., Holmes, J. A., Kalagian, W. F., & Partington, B. M. (2001). Completing the picture: Adolescents talk about what’s missing in sexual health services. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 92(1), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404840

- Foster, L. R., Byers, S. E., & Sears, H. A. (2011). Middle school students’ perceptions of the quality of the sexual health education received from their parents. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 20(3), 55–65.

- Grace, A. P. (2018). Alberta bounded: Comprehensive sexual health education, parentism, and gaps in the provincial legislation and educational policy. Canadian Journal of Education, 41(2), 472–497.

- Gray, S., MacIsaac, S., & Harvey, W. J. (2018). A comparative study of Canadian and Scottish students’ perspectives on health, the body and the physical education curriculum: The challenge of ‘doing’ critical. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 9(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2017.1418179

- Henderson, G. E., Beach, P., & Coombs, A. (2021). Financial literacy education in Ontario: An exploratory study of elementary teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, and practices. Canadian Journal of Education, 44(2), 308–336. https://doi.org/10.53967/cje-rce.v44i2.4249

- Hickson, C., Robinson, D. B., Berg, S., & Hall, N. (2012). Active in the north: School and community physical activity programming in Canada. International Journal of Physical Education, 49(2), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.5771/2747-6073-2012-2-16

- Ingman, B. C., Lohmiller, K., Cutforth, N., Borley, L., & Belansky, E. S. (2017). Community-engaged curriculum development: Working with middle school students, teachers, principals, and stakeholders for healthier schools. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 19(2), 9–34.

- Kilborn, M., Lorusso, J., & Francis, N. (2016). An analysis of Canadian physical education curricula. European Physical Education Review, 22(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15586909

- Kumar, S., & Preetha, G. (2012). Health promotion: An effective tool for global health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 37(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.94009

- Larkin, J., Flicker, S., Flynn, S., Layne, C., Schwartz, A., Travers, R., Pole, J., & Guta, A. (2017). The Ontario sexual health education update: Perspectives from the Toronto Teen Survey (TTS) youth. Canadian Journal of Education, 40(2), 1–24.

- Laverty, E. K., Noble, S. M., Pucci, A., & MacLean, R. E. (2021). Let’s talk about sexual health education: Youth perspectives on their learning experiences in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 30(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2020-0051

- Leahy, D., Burrows, L., McCuaig, L., Wright, J., & Penney, D. (2016). School health education in changing times: Curriculum, pedagogies and partnerships. Routledge.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lokanc-Diluzio, W., Cobb, H., Harrison, R., & Nelson, A. (2007). Building capacity to talk, teach, and tackle sexual health. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 42(1/2), 135–143.

- Lu, C., & McLean, C. (2011). School health education curricula in Canada: A critical analysis. Revue phénEPS/ PHEnex Journal, 3(2), 1–20.

- Marshall, J. M. (1966). Teacher preparation in health and health education in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 57(10), 458–462.

- Matheson, M. N., DeLuca, C., & Matheson, I. A. (2020). An assessment of personal financial literacy teaching and learning in Ontario high schools. Citizenship, Social, and Economics Education, 19(2), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173420927665

- McKay, A. (2004). Sexual health education in the schools: Questions and answers. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13(3/4), 129–141.

- McKay, A., & Barrett, M. (1999). Pre-service sexual health education training of elementary, secondary, and physical health education teachers in Canadian faculties of education. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 8(2), 91–101.

- McKay, A., & Bissell, M. (2009). Sexual health education in the schools: Questions & answers. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 18(1/2), 47–60.

- McKay, A., Byers, S. E., Voyer, S. D., Humphreys, T. P., & Markham, C. (2014). Ontario parents’ opinions and attitudes towards sexual health education in the schools. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(3), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.23.3-A1

- McKay, A., Pietrusiak, M.-A., & Holowaty, P. (1998). Parents’ opinions and attitude towards sexuality education in the schools. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 7(2), 139–145.

- Meaney, G. J., Rye, B. J., Wood, E., & Solovieva, E. (2009). Satisfaction with school-based sexual health education in a sample of university students recently graduated from Ontario high schools. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 18(3), 107–125.

- Munro, J. (2003). Sexuality education: Reflecting on teachers’ narratives of experiences and collaborative research. In B. Ross, & L. Burrows (Eds.), It takes two feet: Teaching physical education and health in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 101–112). Dunmore Press.

- Ninomiya, M. (2010). Sexual health education in Newfoundland and Labrador schools: Junior high teachers’ experiences, coverage of topics, comfort levels, and views about professional practice. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 19(1/2), 15–26.

- Noon, S., & Arcus, M. (2002). Student perceptions of their experience in sexuality education. Canadian Home Economics Journal, 51(2), 15–20.

- Nutbeam, D., McGill, B., & Premkumar, P. (2018). Improving health literacy in community populations: A review of progress. Health Promotion International, 33(5), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax015

- Phillips, K. P., & Martinez, A. (2010). Sexual and reproductive health education: Contrasting teachers’, health partners’ and former students’ perspectives. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101(5), 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404856

- Pulimeno, M., Piscitelli, P., Colazzo, S., Colao, A., & Miani, A. (2020). School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. Health Promotion Perspectives, 10(4), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2020.50

- Rayside, D. (2014). The inadequate recognition of sexual diversity by Canadian schools: LGBT advocacy and its impact. Journal of Canadian Studies, 48(1), 190–225. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.48.1.190

- Riecken, T., Tanaka, M. T., & Scott, T. (2006). First nations youth reframing the focus: Cultural knowledge as a site for health education. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 29(1), 29–42.

- Robinson, D. B., MacLaughlin, V., & Poole, J. (2019). Sexual health education outcomes within Canada’s elementary health education curricula: A summary and analysis. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 28(3), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2018-0036

- Robinson, D. B., Sulz, L., Morrison, H., Wilson, L., & Harding-Kuriger, L. (2023). Health education curricula in Canada: An overview and analysis. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2023.2178944

- Russell-Mayhew, S., Ireland, A., & Klingle, K. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to promoting health in schools: Lessons learned from educational professionals. Canadian School Counselling Review, 1(1), 49–55.

- Rye, B. J., Mashinter, C., Meanet, G. J., Wood, E., & Gentile, S. (2015). Satisfaction with previous sexual health education as a predictor of intentions to pursue further sexual health education. Sex Education, 15(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.967389

- Sinkinson, M., & Burrows, L. (2011). Reframing health education in New Zealand/Aotearoa schools. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 2(3–4), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2011.9730359

- Stosich, E. L., & Bae, S. (2018). Engaging diverse stakeholders to strengthen policy. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(8), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718775670

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). (2015). The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. The University of Adelaide.

- Vamos, S., & Zhou, M. (2007). Educator preparedness to teach health education in British Columbia. American Journal of Health Education, 38(5), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2007.10598983

- Vamos, S., & Zhou, M. (2009). Using focus group research to assess health education needs of pre-service and in-service teachers. American Journal of Health Education, 40(4), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2009.10599094

- Veugelers, P. J., & Schwartz, M. E. (2010). Supportive environments for learning: Healthy eating and physical activity within comprehensive school health. Canadian Journal of Public Health/ Revue Canadienne de Santé Publique, 101(Suppl. 2), S5–S8.

- Videto, D. M., & Dake, J. A. (2019). Promoting health literacy through defining and measuring quality school health education. Health Promotion Practice, 20(6), 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919870194

- Walters, L., & Laverty, E. (2022). Sexual health education and different learning experiences reported by youth across Canada. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 31(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2021-0060

- Weaver, A. D., Byers, S. E., Sears, H. A., Cohen, J. N., & Randall, H. E. S. (2002). Sexual health education at school and at home: Attitudes and experiences of New Brunswick parents. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11(1), 19–31.

- Wood, J., McKay, A., Wentland, J., & Byers, S. E. (2021). Attitudes towards sexual health education in schools: A national survey of parents in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 30(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2020-0049

- World Health Organization. (2008). School policy framework: Implementation of the WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. World Health Organization.

- Zain Al-Dien, M. M. (2010). Perceptions of sex education among Muslim adolescents in Canada. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 30(3), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602004.2010.515823