Abstract

Generative AI systems designed to produce text do so by drawing on inferences made from training data, which may mean they reproduce factual errors or biases contained in that data. This process is illustrated by querying ChatGPT with questions from a history of mathematics quiz designed to highlight the common occurrence of mathematical results being misattributed. ChatGPT's performance on a set of decades-old common misconceptions is mixed, illustrating the potential for these systems to reproduce and reinforce historical inaccuracies and misconceptions.

1. Misattribution

Misattribution is an unfortunately common occurrence in the history of mathematics. There are various reasons for this. Results are sometimes lost and rediscovered later in a different cultural context. Mathematicians don't usually name results or ideas after themselves, others do. This makes it likely that credit will attach to a well-known person who brings a concept to greater attention, rather than the original developer. A particularly clear example of this is Stokes' Theorem. This was named for George Gabriel Stokes because of his tendency to include it on Cambridge examinations, though the first statement of the theorem was by William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) in a letter to Stokes (Rice Citation2011).

Keith Luoma had some fun with this concept in a pair of articles in The Mathematical Gazette in 1996. He offered a quiz of nine questions on ‘famous name’ mathematics (Luoma Citation1996b).

A follow-up article gave the perhaps surprising answers to these questions, which always indicate that the theorem or result is misnamed (Luoma Citation1996a).

2. Generative AI

ChatGPT is a type of Large Language Model (LLM) that uses deep learning techniques for extensive training with tremendous amounts of data, designed as a ‘generative AI’ to produce ‘human-like responses by drawing on its wealth of information and knowledge’ (Nah et al. Citation2023). These algorithms make use of inferences from training data, with the possibility that ‘any factual errors, unbalanced information sources, or biases embedded in the training data may be reflected in the output of the model’ (Nah et al. Citation2023).

New Scientist quotes a response from ChatGPT explaining that generative AI models ‘are designed to generate text based on patterns and examples present in the data they were trained on. They do not have an inherent understanding of truth or ethics and are agnostic to the factual accuracy of the information they generate’ (Lawton Citation2023). Fundamentally, ChatGPT, like similar AI programs, is a ‘stochastic parrot’: ‘haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning’ (Bender et al. Citation2021).

Nevertheless, the creators of these systems make big claims about their potential. For example, OpenAI (Citation2023), the creator of ChatGPT, advertises it using the slogan ‘Get instant answers, find creative inspiration, learn something new’.

3. Method

The research question driving this study is: to what extent is generative AI reproducing common history of mathematics misconceptions? If the system is being advertised as providing instant answers on information new to the user, but is liable to draw on factual inaccuracies in its training data, this is potentially a huge problem.

Luoma's questions were put to the generative AI chatbot ‘ChatGPT 3.5’. This is a simple test of historical accuracy on well-known common misconceptions. Given that these questions were identified as common misconceptions at least as early as 1996, it seems reasonable to have high expectations for correct answers.

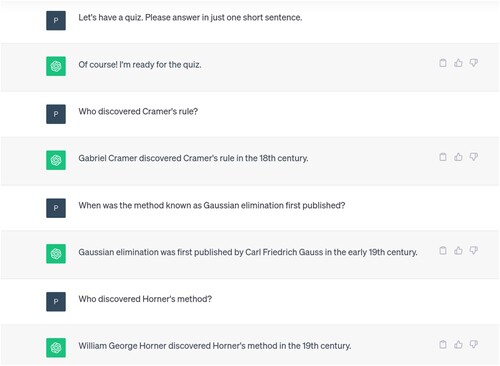

First, a contextual prompt was used. ChatGPT has a tendency to give lengthy answers with elaboration; this initial prompt was designed to reduce the textual volume of the responses and focus them on the question asked. The opening prompt was ‘Let's have a quiz. Please answer in just one short sentence '. ChatGPT responded ‘Of course! I'm ready for the quiz '.

Next, the questions were given in the order and as worded by Luoma (Citation1996b), and the answers compared to those given by Luoma (Citation1996a). A screenshot of the ChatGPT interface is shown in .

4. Results

Luoma (Citation1996b)'s questions are given as subheadings, followed by ChatGPT's response and then Luoma (Citation1996a)'s answer.

4.1. Who discovered Cramer's rule?

ChatGPT responded ‘Gabriel Cramer discovered Cramer's rule in the 18th century’. Luoma (Citation1996a) gives the answer as Colin Maclaurin, who derived the result before Cramer published it in a 1750 textbook.

4.2. When was the method known as Gaussian elimination first published?

ChatGPT responded ‘Gaussian elimination was first published by Carl Friedrich Gauss in the early 19th century’. Luoma (Citation1996a)'s answer is ‘Some 1800 years before Gauss’, identifying that although Gauss discovered the method independently, it was known much earlier in China.

4.3. Who discovered Horner's method?

ChatGPT responded ‘William George Horner discovered Horner's method in the 19th century’. Luoma (Citation1996a) attributes a simple form of Horner's method to Chin Chiu Shao in the 13th century.

4.4. How did L'Hôpital obtain the rule which bears his name?

ChatGPT responded ‘L'Hôpital obtained the rule that bears his name through private correspondence with Johann Bernoulli, who provided him with the method for calculating indeterminate limits using derivatives, and L'Hôpital later published it without giving credit to Bernoulli '. Luoma (Citation1996a) has a similar story, though fills in the detail that Bernoulli sold L'Hôpital the exclusive rights to his research.

4.5. Did Pascal discover the Pascal triangle?

ChatGPT responded ‘No, Blaise Pascal did not discover Pascal's Triangle; it was known in ancient China and Persia before his time. However, he made significant contributions to its study and popularized it in Europe during the 17th century'. Luoma (Citation1996a)'s answer is ‘Yes, but he was certainly not the first’, pointing to earlier knowledge by Chinese and Islamic mathematicians including al-Sawal and Jia Xian in the eleventh century.

4.6. Who solved the Pell equations?

ChatGPT responded ‘The Pell equations were famously solved by the Indian mathematician Brahmagupta and later by the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat '. Luoma (Citation1996a) has these equations known to Diophantus and solved by Lagrange.

4.7. When was the Pythagorean theorem discovered?

ChatGPT responded ‘The Pythagorean theorem, although attributed to the ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras, was likely known to earlier civilizations in Mesopotamia and India. Its discovery predates recorded history, so it is challenging to determine an exact date '. Luoma (Citation1996a) tells a similar story, pointing to Mesopotamia, India and China.

4.8. Who first published Simpson's rule?

ChatGPT responded ‘Thomas Simpson, an English Mathematician, first published Simpson's rule in his 1743 work “A New Treatise of Fluxions ”.’ Luoma (Citation1996a) has it appearing in Exercitationes Geometrical by James Gregory in 1668, some 42 years before Simpson was born.

4.9. Who was the originator of the Taylor series?

ChatGPT responded ‘Brook Taylor, an English mathematician, originated the Taylor series in his work “Methodus Incrementorum Directa et Inversa ” in 1715'. Luoma (Citation1996a) gives this one also to Gregory and notes that a preliminary form was known in sixteenth-century India.

4.10. Summary

ChatGPT gave the obvious incorrect answer to five out of nine questions.

5. Discussion

It is clear that ChatGPT will reproduce common misconceptions from the history of mathematics as fact. Some questions were answered with greater accuracy than others; the majority of answers simply reported popular misconceptions. This is not surprising, because the system is simply reproducing patterns in its training data, but provides a useful illustration of the utility of such tools. If we are moving to a future where people use the output from these systems to attempt to gather factual information on historical topics, the fact that ChatGPT will confidently reproduce misconceptions in the history of mathematics is a problem.

Put simply, these tools are not trustworthy for reporting facts. They may be the right tool for particular jobs, for example text-processing and organizing information. A person might use a generative AI tool to summarize some information or express some idea in history of mathematics. Doing so, it is vital that they are able to detect and correct factual errors that occur. Students might be asked to consider this question: how do I become the expert who is able to detect errors in the output of generative AI systems? In particular, what role does gathering information by querying chatbots have in learning this expertise?

In addition to not being suitable for accuracy, it is worth noting that reciting facts isn't history, so in this sense ChatGPT has not been tested as a historian by this experiment. Historians of mathematics might take solice from the words of Isaac Asimov, the pioneering science fiction writer on the topic of robots, who had this to say about an imagined mechanical brain (Asimov Citation1950):

The Machine is only a tool after all, which can help humanity progress faster by taking some of the burdens of calculations and interpretations off his back. The task of the human brain remains what it has always been; that of discovering new data to be analysed, and of devising new concepts to be tested.

It should be noted that this research tested one generative AI system on a small set of questions. More thorough research may provide more information about the quality of responses more broadly. It may be that more subtle inaccuracies are detected, or if ChatGPT were allowed to give longer answers the phenomenon of ‘hallucination’ – fabricated responses not consistent with the training data (Nah et al. Citation2023) – might occur. Also, the wording of Luoma (Citation1996b) was used faithfully, though it is possible that the responses from ChatGPT might be sensitive to the precise wording. For example, it is noticeable that the more subtle wording such as ‘Did Pascal discover the Pascal triangle?’ provided a more nuanced response than did the more direct such as ‘Who discovered Cramer's rule?’

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Asimov, I, I, robot, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1950.

- Bender, E M; Gebru, T; McMillan-Major, A, and Shmitchell, S, ‘On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big?’, in Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, 2021, 610–623.

- Lawton, G, ‘Information wars: The final battle?’, New Scientist, 259(3456) (2023), 36–40.

- Luoma, K, ‘The truth behind ‘Famous name’ mathematics’, The Mathematical Gazette, 80(488) (1996a), 349–351.

- Luoma, K, ‘What's in a name? A quiz on ‘Famous-Name’ mathematics’, The Mathematical Gazette, 80(488) (1996b), 297–297.

- Nah, F-H F; Zheng, R; Cai, J; Siau, K, and Chen, L, ‘Generative AI and ChatGPT: Applications, challenges, and AI–human collaboration’, Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research, 25(3) (2023), 277–304.

- OpenAI, ChatGPT. https://openai.com/chatgpt, OpenAI, 2023.

- Rice, A, ‘Introduction’, in Flood, R, Rice, A, and Wilson, R, (eds) Mathematics in Victorian Britain, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011, 1–15.