ABSTRACT

Jacques Becker is well known as an auteur, one of the few French directors working in the post-war period who has been hailed as an ‘uncle’ of the New Wave (alongside Robert Bresson, Max Ophuls, Jean-Pierre Melville and Jacques Tati). This article positions him in relation to the ‘quality’ and popular cinema of the period through an exploration of the critical discourses that coalesce around his films. Becker embraced an auteurist conception of cinema but operated in an industry that was dominated by a commercial, quality cinema of international co-productions, stars and films destined for export. Drawing on articles from both the specialist and general press, this article explores the construction of Becker as an auteur at the very moment when the politique des auteurs was setting out its stall in opposition to the Tradition of Quality and popular cinema more generally. By tracing how Becker came to occupy a unique position in post-war French film, it sheds light on the framing of popular, quality and auteur film in relation to key social, political and aesthetic discourses in play at this time.

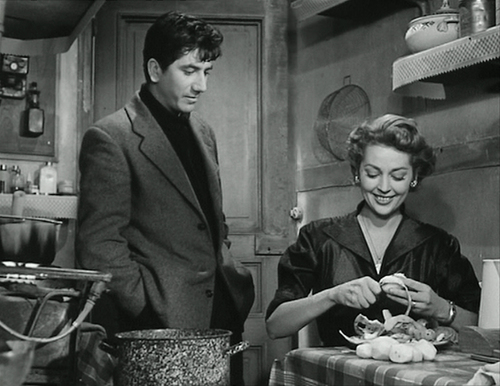

In Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin/The Adventures of Arsène Lupin (Jacques Becker, Citation1957), there is a sequence that was much commented on by critics of the time (for example, Laurent Citation1957; Truffaut Citation1957; Vivet Citation1957). It shows the gentleman-burglar Arsène Lupin (Robert Lamoureux), alias respectable and wealthy man about town André Laroche, returning home after robbing the Président du Conseil (Henri Rollan) of a Leonardo sketch and a Botticelli painting. Lupin/Laroche parks his car in the garage, goes into his house, gives orders to his servants, changes out of his disguise, listens to a song (‘Fermons nos rideaux’) and opens his post while waiting for his bath to run. The main characteristic of the sequence is the (anti-)spectacle of Lamoureux (cast against type) as Lupin/Laroche performing his morning ritual (). His gestures, often highlighted in close-up, reveal not only his secret dual identity, but also his mondain milieu and his tastes and lifestyle: music lover, dandy, gourmet, ladies’ man. In fact, he is very much like Jacques Becker himself. Whatever their general opinion of the film, the reviewers who highlighted this sequence singled it out as an example of Becker’s authorial signature, typical of his preference for the mundane over the extraordinary, for everyday gestures over heroics, for characters over plot.Footnote1 In this respect, it reveals the kinship between Becker’s Lupin and Max (Jean Gabin) and Riton (René Dary) in Touchez pas au grisbi/Honour Among Thieves (1954), gangsters coming to terms with betrayal over pâté and biscottes before changing into their pyjamas and brushing their teeth (), or Françoise (Anne Vernon), the middle-class housewife who has moved into a Left Bank garret to assert her independence from an unfaithful husband (Louis Jourdan), peeling potatoes in her cramped kitchen while fending off the attentions of her new neighbour Robert (Daniel Gélin) in Rue de l’Estrapade/Françoise Steps Out (1953) ().

Figures 1 and 2. Robert Lamoureux as Arsène Lupin/André Laroche. Removing his disguise is just another everyday gesture, like putting on a record.

Figure 4. Françoise (Anne Vernon) peeling potatoes in Rue de l’Estrapade while Robert (Daniel Gélin) looks on.

The precedence given in Arsène Lupin to character and setting caused certain critics (Baroncelli Citation1957; Mauriac Citation1957; Truffaut Citation1957) to lament the absence of the intricate plot mechanisms and elaborate heists that characterise Maurice Leblanc’s novels. However, this preference also establishes the film in Becker’s cinematic universe: he famously declared on more than one occasion that he had no interest in ‘subjects’, in the exceptional or picturesque, expressing instead his passion for his characters and, in turn, his actors (Becker Citation1953).Footnote2 Though François Truffaut criticised Becker’s Lupin as an ‘anodyne’ [anodin] repetition of Max le Menteur (Truffaut Citation1954a), in other writing he discerned an authenticity in Becker’s films that he saw as residing in the actors’ embodiment of their characters through everyday gestures (Citation1964). He described Becker as an ‘auteur’ working ‘in the margins of trends, in fact, […] he is diametrically opposed to all the tendencies of French cinema’ (Truffaut Citation1954a, 54).Footnote3 The following year, he would present Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs/Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1954) – often regarded as an embarrassing anomaly in Becker’s œuvre – as a test case for the politique des auteurs (Truffaut Citation1955).Footnote4

Becker is well known as an auteur, one of the few French directors working in the post-war period who has been hailed as an ‘uncle’ of the New Wave (alongside Robert Bresson, Max Ophuls, Jean-Pierre Melville and Jacques Tati). Bertrand Tavernier’s homage in Voyage à travers le cinéma français/A Journey through French Cinema (2016) has contributed to Becker’s prominence and reputation. This personal journey opens with Tavernier’s memories of discovering Becker; first Dernier atout (‘The trump card’) (1942), whose car chase marked him as a young child, and then, the tragic intensity of Casque d’or/Golden Marie (1952), which impressed him as an adolescent. Tavernier devotes a full 20 minutes to this director of ‘ordinary decency’ [la décence ordinaire], reiterating many of the characteristics that Becker’s contemporaries were already articulating in the 1940s and 1950s, as we shall see: elegant, pared-down films driven by characters, not plot; a technical mastery that goes hand in hand with human warmth; a very French cinema that nonetheless draws on the Hollywood films of Howard Hawks and Ernst Lubitsch. In this article, I want to position Becker in relation to the ‘quality’ and popular cinema of the period through an exploration of the critical discourses that coalesce around his films. In particular, I will focus on the interplay between the construction of his authorial persona and wider discourses – ideological and aesthetic – on the role of film and its relation to the real, and how these connect in turn to notions of quality and national cinema.

Becker has often been framed as a transitional figure, offering a bridge between classicism and the modernity of the New Wave. His film career began in the early days of sound as assistant to Jean Renoir and was cut short with his death at the age of 53, just as Le Trou/The Hole (1960), his thirteenth feature film as director, was being released. A glance at his filmography shows that this transitional position was synchronic as well as diachronic. Becker embraced an auteurist conception of cinema, for example contrasting his (unfulfilled) desire to make ‘[his] little Moroccan Nanook […] in peace’ [tranquillement [… son] petit Nanook marocain] with the realities of filming star comic actor Fernandel in the popular studio film Ali Baba et les 40 voleurs, henceforth Ali Baba (Rivette and Truffaut Citation1954, 15–16).Footnote5 He nevertheless operated in an industry that was dominated by a commercial, quality cinema of international co-productions, stars and films destined for export. Like his contemporaries Ophuls and Claude Autant-Lara, but unlike Bresson and Melville, all of Becker’s films (apart from Le Trou, which he co-produced himself) were mainstream productions, ranging from the low-budget Édouard et Caroline/Édouard and Caroline (Magnan Citation1951), filmed on two sets in a few weeks, to the super-production Ali Baba, shot in colour and partly on location, with an illustrious international cast including France’s number-one box-office star.Footnote6

Drawing on articles from both the specialist and general press, I will explore the construction of Becker as an auteur at the very moment when the politique des auteurs was setting out its stall in opposition to the Tradition of Quality and popular cinema more generally, in order to ask what this construction – which highlights authenticity and a focus on everyday gestures, as mentioned above, but also restrained elegance and Frenchness – reveals about debates around cinema and the French film industry. In a second part, I will focus on the somewhat contradictory discourses that emerge in relation to two of Becker’s more popular films as reviewers grapple with expectations of generic and aesthetic excess associated with popular comedies on the one hand, and of authenticity, restraint and ‘good taste’ linked to the filmmaker on the other. My contention is that the critical construction of Becker’s authorial persona reveals tensions in the framing of popular, quality and auteur film at this time, but also how these debates are bound up with social and cultural concerns around the everyday, the question of realism and the post-war reframing of national identity.

Becker and the critics: construction of an auteur

From his fourth completed feature, Antoine et Antoinette/Antoine and Antoinette (Best Film at Cannes in 1947), Becker was already considered to be an ‘artiste’ (Mauriac Citation1947), ‘the most accomplished and balanced of our filmmakers [with René Clair]’Footnote7 (Magnan Citation1947), ‘a master, a great master’Footnote8 (C. H. Citation1947). Given that the construction of an auteur is necessarily retrospective and cumulative, many reviews begin with a summary of Becker’s films to date, building a picture of an artist and an œuvre. Three main themes emerge: the heterosexual couple, as in Falbalas/Paris Frills (1945), Antoine et Antoinette (1947), Rendez-vous de juillet/Rendezvous in July (1949), Édouard et Caroline, Casque d’or and Rue de l’Estrapade; male friendship and questions of loyalty and betrayal, as seen in Dernier atout, Falbalas, Casque d’or, Touchez pas au grisbi and Le Trou; and artistic creation and artisanal skill, for example in Falbalas, Édouard et Caroline, Casque d’or, Rue de l’Estrapade, Arsène Lupin, Montparnasse 19/The Lovers of Montparnasse (1958) and Le Trou. It is also possible to trace how certain elements of style come to be identified with Becker: a focus on the everyday expressed through detailed observation of a milieu; a flowing editing style; precise and restrained mise en scène; and the importance of character. Given the importance now accorded to Becker in histories of post-war French film, it is unsurprising that these characteristics connect to wider discourses circulating at the time about film, most especially around realism, the role of the script and the idea of quality.

The most frequently recurring element in the construction of Becker’s authorial persona is the rather slippery concept of authenticity, linked to the equally tricky idea (or ideal) of cinematic realism. Contemporary reviews of Becker’s films are replete with terms used more or less interchangeably – ‘realism’, ‘neorealism’, ‘verism’, ‘truth’, ‘authenticity’, ‘quotidian’, ‘banal’, ‘intimist’, ‘simplicity’, ‘stripped back’, ‘natural’, ‘documentary’, ‘naturalism’, even ‘neo-intimism’ – referring to the films’ detailed attention to the everyday, the familiar, expressed through the characters, their interactions with each other and their environment.Footnote9 These terms are mobilised according to the reviewer’s opinion of the film – by no means always uncritical – and in certain cases, according to their stance on debates about the relationship between film and the world it depicts. These debates emerged with renewed prominence in post-war France, as the question was addressed from an aesthetic, philosophical or political perspective. As Colin Burnett (Citation2017, 141) describes, ‘“Realisms” of all kinds proliferated in the language of cinephiles and in the visual and storytelling forms of auteurs. What’s more, alongside these realisms, various naturalisms and verisms took hold as well.’

The two major ‘schools’ around which these debates coalesced in the late 1940s are represented in critical responses to Becker’s films. Roger Boussinot’s (Citation1947) Action review of Antoine et Antoinette, in which he decried Antoine’s lack of class solidarity and trade union card, and Georges Marescaux’s (Citation1954) dismissal of Touchez pas au grisbi as a ‘vindication of gangsterism’ [apologie du gangstérisme], published in L’Humanité, are exemplary of a certain Marxist view espoused and developed by figures such as Georges Sadoul and Louis Daquin. Burnett (Citation2015, 142) points out that these critics framed realism as the duty of an ‘engaged cinema’ that should ‘explore social reality in an effort to expose the exploitation of workers and peasants’ and the possibilities of emancipation through class consciousness.Footnote10 On the other hand, the concept developed by André Bazin and Roger Leenhardt (among others) of cinema as an inherently realist medium – the art form with the potential to most closely render the world of its creators and viewers – is exemplified by Jacques Doniol-Valcroze (Citation1954a), who highlights ‘artistic conscience and a refusal of gratuitous aestheticism’ in his review of Grisbi, or by Claude Mauriac (Citation1949), who describes Rendez-vous de juillet as revealing ‘the physical, moral and perhaps even metaphysical existence of a certain type of contemporary youth’.Footnote11

Both schools ‘claimed’ Becker to some extent. His Left-wing engagement, established in the 1930s and during the Occupation, raised expectations that his films should conform to the Marxist tenets of social realism.Footnote12 For the exponents of what would come to be known as Bazinian realism, the quasi-documentary attention to the contemporary world in his mise en scène and his cinephile embracing of neorealism (especially Vittorio de Sica’s Ladri di biciclette/The Bicycle Thieves, released in 1949 in France), corresponded to their sense of the potential relationship between film and the world.

Becker participated in these debates, directly responding to Boussinot in the following week’s edition of Action, making clear what his intentions were (‘to try and give as accurate as possible an impression to the spectator of the ATTITUDE that working-class men and women from Paris have in their relations with their peers’) and what they were not (‘my film doesn’t ask any [social] questions and in no way was that its intention’).Footnote13 He added that, unlike Boussinot, he thought Antoine did belong to a trade union, but this was not the ‘matière’ (matter) of his film (Becker Citation1947b). Becker had already considered the question of realism in a debate that appeared in the Left-leaning L’Écran français in October, entitled ‘To Depict Reality or Turn One’s Back on it?’Footnote14 (Dabat Citation1947):

With regard to realism, who today outclasses the Vidor of The Crowd or Stroheim’s Greed? It is above all a question of people and not tendencies; far from pushing directors to commit to this or that path, we should instead be begging them to work according to their own temperament. (Cited in Vignaux Citation2000, 95)Footnote15

Despite his long-standing Left-wing engagement, Becker clearly declines to embrace an ideological position here, preferring an apolitical authorial approach. In these post-war years, the idea of the film auteur seems to have been paramount for the filmmaker.Footnote16 The very same week that Action ran Boussinot’s review of Antoine et Antoinette, he was proposing in L’Écran français that a film auteur is ‘a complete author’ [un auteur complet]; that is, one who ‘owns’ a film because they have constructed it by writing the script and the dialogue as well as directing the actors and developing the mise en scène (Becker Citation1947a). To some extent, Becker is anticipating Alexandre Astruc’s seminal article ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: la caméra-stylo’, which would appear in L’Écran français a few months later, arguing for a cinema where ‘the scriptwriter directs his own scripts, or rather [where] the scriptwriter ceases to exist, for in this kind of filmmaking the distinction between author and director loses all meaning’ (Astruc Citation[1948] 2022, 35).

Becker’s own temperament, as we have seen, led to a privileging of the everyday, in terms of subject matter, but also gesture and mise en scène. This corresponded very much with the theorist and filmmaker Roger Leenhardt’s framing of realism, summarised by Dudley Andrew (Citation2007) as a concern with ‘the magnificence of the quotidian’. In the 1930s, Leenhardt had set out a vision of cinematic realism as existing in the ellipses – as much in what is not on the screen as in what is shown – a notion that also has relevance to Becker’s films, as we will see. In a discussion of Leenhardt’s role in the Objectif 49 cine-club, Burnett (Citation2015) points out that his idea of cinematic realism shifted somewhat after the war: ‘Leenhardt stripped his subject down to “the detail”, the minuscule, because “cinematic vision is a concrete and meticulous form of analysis – the camera is a magnifying glass”.’Footnote17 Leenhardt could have been describing the ‘entomologist’ [entomologiste] (Naumann Citation2001, 87) approach Becker adopted, when approaching his characters in particular. Contemporary reviewers also highlighted this tendency, consistently emphasising the relationship between detailed observation, everyday gestures and the authenticity of characters and milieux.Footnote18 A recurring image is that of a painter of miniatures, who with a tiny brush paints in the details of daily lives. Such a perspective constructs Becker as a director concerned above all with the portrayal of characters’ interaction with their respective domestic and social environments.Footnote19 As Alastair Phillips (Citation2018) points out, this concern also links Becker’s films, with their ‘popular dramatized fictional lives of French people and their homes and occupations’, to the contemporary intellectual interest in ‘mass society, urbanism and the everyday’ proposed by Henri Lefebvre’s Critique of Everyday Life (vol. 1 of which was first published in 1947) (Lefebvre Citation[1947] 2008). Phillips argues that the attention to everyday spaces, rhythms and challenges in films such as Antoine et Antoinette and Rendez-vous de juillet is evidence of a ‘practice of real life’, a kind of cinematic version of Lefebvre’s proposed survey, ‘How we live’ (Lefebvre Citation[1947] 2008, 196). I would add that it is surely no coincidence that one of Becker’s key collaborators on Antoine et Antoinette was Françoise Giroud, who at this time was also the founding co-editor of Elle (with Hélène Lazareff). Giroud would go on to co-found L’Express with Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, with whom she would also form the ‘reigning couple of “everyday-life”’ (Ross Citation1996, 66).Footnote20 Giroud espoused a different and arguably more immediately influential concept of the quotidian to Lefebvre, one whose influence is also seen in the films Annette Wademant wrote for Becker, Édouard et Caroline and Rue de l’Estrapade, where the focus is clearly placed on everyday life from a female perspective, including the restrictions of heterosexuality and domesticity.Footnote21

Though they did not make the connection to what might be termed the post-war ‘invention of the everyday’, to borrow from Michel de Certeau, contemporary film critics generally (though not exclusively) welcomed Becker’s focus on the quotidian. And yet, this is tempered (sometimes in the same review) by concerns regarding what Bazin (Citation1953) called the ‘disconcerting tenuousness of his scripts’Footnote22: critics repeatedly remark that the script is too ‘slight’ [mince], lacking in coherence or pace. This frequently goes hand in hand with a sense of something missing. For example, Jean-Pierre Vivet (Citation1947) finds that the depiction of the streets of Paris in Antoine et Antoinette, accurate in detail and tone, is yet lacking in warmth and colour, several critics criticised Rendez-vous de juillet’s focus on the bohemian youth of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, wishing for a more diverse picture of a generation (Fayard Citation1949; Gaillard Citation1950; Opéra Citation1949), and we have already referred above to complaints that Arsène Lupin sacrifices the pace and verve of Maurice Leblanc’s novels in favour of a character study with a Belle Époque atmosphere (Baroncelli Citation1957; Truffaut Citation1957; Vivet Citation1957). For some, like Jean Queval (Citation1952), Becker’s choice of milieu is regarded as a missed opportunity; Casque d’or’s Belle Époque apaches and ‘difficult’ [pénible] subject left him nostalgic for Édouard et Caroline and Antoine et Antoinette. For others, disappointment is linked to a personal enthusiasm; Olivier Merlin (Citation1953) would have preferred Rue de l’Estrapade to be a film about motor racing, a passion he shared with his school friend Becker, while Mauriac (Citation1957), childhood fan of Leblanc’s stories, regrets what he regards to be an ersatz Lupin. For still others, the question is more political: Sadoul (Citation1953) dismissed Rue de l’Estrapade as the worst in a series of errors on the part of a fellow traveller who persisted in depicting the ‘tame adventures’ [plates aventures] of conventional bourgeois or déclassé characters.

In part, no doubt, critics were disconcerted by Becker’s desire to explore new territory and to avoid being generically pigeonholed. However, the filmmaker’s dislike of the extraordinary, the spectacular, the heroic or the didactic, also left his films open to this kind of critique. On the one hand, the absence of a strong plotline or standpoint had critics decrying a lack of substance; on the other, this lacuna facilitated the construction of a Becker corresponding to critics’ desires, with the inevitable result that they were disappointed when his next film did not match their vision and expectations. These recurring responses suggest that Becker’s films can be seen as an illustration of cinema as an ‘art of absence’ (Andrew Citation2007, 59), haunted by what is not there, excluded by the script, the framing, or in the cutting room. This comes back to the question of cinematic realism, and especially to Leenhardt’s idea that film’s ‘primordial realism’ exists primarily in the ellipses and the ‘assemblage’, the gaps in the diegesis and between shots (Andrew Citation2007, 58). Bazin expressed a similar idea when he referred to the dilemma of all filmmakers, ‘compelled to choose between one kind of reality and another’ (cited in Andrew Citation2007, 62). Becker’s collaborators frequently highlighted his constant struggles with this dilemma on set and in the cutting room: where to put the camera, which angle to choose, when to cut.Footnote23 This led, somewhat unfairly, to a reputation for prevarication and indecisiveness. Becker’s most consistent collaborator, the editor Marguerite Houllé-Renoir, however, regarded this constant questioning as fundamental to the precision and care of Becker’s craft (Vignaux Citation2000, 68). Becker’s choices (of subject matter, of camera position, framing or editing match), however painfully reached, systematically downplayed the dramatic in favour of the ordinary. This led, as seen above, to a sense for some critics that his films were sidestepping their subjects rather than confronting them head on. A frustrated Becker was led to respond in a text published in Arts (Becker Citation1953), ‘Allez donc au cinéma sans penser’, where he made explicit his lack of interest in the subject, his ‘passion’ for his characters (which he refers to as puppets [marionnettes]) and (perhaps disingenuously) set out the true aim of his films: ‘if in depicting my characters with care I have given some the illusion that I have wanted to portray my period (!) that’s all to the good, and flattering, but it is indeed an illusion; I don’t have such lofty pretentions …’ (cited in Vignaux Citation2000, 144).Footnote24 Although contemporary critics lamented the thin plotlines, they also bore Becker out in their celebration of how he enabled his actors to embody their characters in such a way that the viewer is able to ‘fill in the gaps’, to grasp what Darragh O’Donoghue (Citation2018, 23) describes as their ‘full, complex and shifting inner and outer lives’.

The (false) impression that Becker’s films never quite get to grips with their subject matter is expressed in characteristically forthright terms by critic and screenwriter Henri Jeanson. Jeanson and Becker clashed on several occasions but most notably over the film that would become Montparnasse 19 (1958), which Becker took over after the death of Max Ophuls, on the condition that he would be able to rework Ophuls’s and Jeanson’s script. Becker’s changes led to a very public dispute which Jeanson pursued through legal channels and in the columns of various newspapers.Footnote25 The weekly publication Arts invited both men to put forth their side in an article published in August 1957, just as filming was about to begin. Jeanson makes clear that he does not consider Becker to be the man for the job:

You’re in the habit of accepting a subject but then filming another. You didn’t film Arsène Lupin, you didn’t film Casque d’or; instead, you invented stories that had nothing to do with the original subject. Are you capable, for once, of effacing yourself? You need to film our script, not something else. (Jeanson and Becker Citation1957)Footnote26

Becker’s response – ‘The drama is that Jeanson refuses to understand that a script is not a finished film’ (Jeanson and Becker Citation1957) – appears to reiterate Truffaut’s accusation levelled at other screenwriters associated with the Tradition of Quality, Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost: ‘when they hand in their script, the film has already been made; in their view, the metteur en scène is the person who decides on the framing …’ (Truffaut Citation2022, 52).Footnote27 The exchange is emblematic of two different conceptions of cinema that were set against each other in the 1950s, expressed as a power struggle between screenwriters and directors that came to encapsulate the auteurists’ complaint against mainstream production. It also reveals Becker’s somewhat awkward position as a mainstream filmmaker who defended the idea of the director as auteur.

Ali Baba and Arsène Lupin: quality, taste and the popular

A further characteristic that emerges in reviews of Becker’s films is that of French refinement and taste, often set in opposition to Hollywood vulgarity.Footnote28 This characteristic – expressed particularly through mise en scène and acting – is also linked to a certain idea of French quality filmmaking. As Jean Montarnal (Citation2018) and Frédéric Gimello-Mesplomb (Citation2006, Citation2014) have shown, the notion of quality was central to the reconstruction of the French film industry in the post-war years, a reconstruction played out against a backdrop of audience demand for Hollywood films that had been banned during the war and economic measures such as the Blum–Byrnes agreements that further guaranteed American dominance. Gimello-Mesplomb (Citation2014) has traced how the idea of quality soon became imbricated with questions of funding. Automatic aid (the Fonds de soutien), introduced in 1948 to support domestic production in the face of the Hollywood threat, was highly successful in boosting production of a mainly commercial, genre cinema, of which the films that came to be known under the quality label were just a small part. Gimello-Mesplomb (Citation2006, 144) describes its ‘closed circuit’ effect, whereby already successful producers were encouraged to repeat winning formulae and innovation was stifled. Demands for state funding to be linked to quality, defined in terms of aesthetic or cultural value or public service, led to the setting aside of a small portion of the Fonds to support quality production. One of the side-effects of this regime was the development of a critical discourse that opposed commercial, popular cinema to the idea of quality, yet many commercial films were produced and promoted as quality productions, including several of Becker’s 1950s films.Footnote29 These growing tensions between popular film and the idea of quality – defined rather vaguely as ‘aesthetic value’ – can be seen in the reception of certain of Becker’s 1950s films, in particular Ali Baba but also Arsène Lupin.

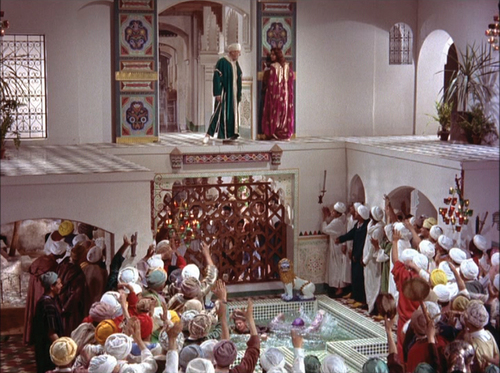

Ginette Vincendeau (Citation2012) qualifies Ali Baba as a ‘painful Orientalist farce’ [pénible farce orientaliste], Becker’s worst film and one of Fernandel’s worst.Footnote30 The film casts European actors in almost all main parts, transforms the fable into a Marseille farce and displaces Syria onto Morocco.Footnote31 To the charge of Orientalism, we could add that of misogyny: the only non-European actor in a major role, the Egyptian star Samia Gamal, is a radically transformed Morgiane.Footnote32 Instead of the wily and active character of the fable who repeatedly foils the thieves’ plots, the film presents us with a practically wordless spectacle deprived of all agency, the object of misogynistic jokes as well as the male gaze ().Footnote33 The contemporary reviews studied, however, do not tend to pick up on these aspects of the film; only Sadoul (Citation1955) and the Express critic (Express Citation1955) refer to the contemporary situation in North Africa (‘without risking any allusion to the contemporary Arab world’; ‘this Orient of the 1001 Nights devoid of oil interests or demands for independence’), and only the Canard enchaîné reviewer, writing under the pseudonym of Donald Duck (Citation1955), acknowledges the silencing of Gamal, though several reviewers have harsh words for the dialogue in general.Footnote34 More attention is given to the generic transformation of the Arabic tale into a Marseille farce via the presence of Fernandel, Henri Vilbert, Ardisson et al., and if, for Sadoul (Citation1955), this pragmatic choice makes sense given the Mediterranean connection (‘Arabic Africa is just opposite the Canebière’), Carrefour (Citation1954) and Donald Duck (Citation1955) find it artificial that Arab characters should speak with Marseille accents (though they do not at any point suggest that they should be played by Arab actors speaking Arabic).Footnote35

The two main topics raised by critics are the incongruity of the director-star-genre combination and the use of colour. The former poses a challenge for perplexed reviewers seeking the ‘right’ criteria by which to judge this film, an ‘Oriental’ fairytale transformed into farce, directed by an auteur known for intimist, realist films or the tragic intensity of Casque d’or, and featuring a monstre sacré of popular comedy. Apart from dissenting voices in L’Express and Le Canard enchaîné, most agree that the film succeeds on the level of popular entertainment: ‘an attractive spectacle’ (A. L. Citation1955), ‘successful/quality/charming entertainment […] in perfect/the best taste’ (Chazal Citation1954; Doniol-Valcroze Citation1954b; Truffaut Citation1954b), ‘a slightly mawkish but enjoyably puerile spectacle’ (Chauvet Citation1954) ().Footnote36 However, they struggle to see why Becker took on a subject which in their view required a broad brush and bold strokes (though more than one suggest that he must have done it for the money).Footnote37 A commonly held view is that, although Becker and Cesare Zavattini (the main co-author of the script) have tried their best with this material unsuited to their particular area of expertise (realism), simplifying the story and reframing it as a comic adventure with an impeccable mise en scène, the film fails to engage audiences.Footnote38 Fernandel, however, is hailed as being at the peak of his art. Even those critics who dislike him (such as Truffaut Citation1954b) acknowledge his mastery of his comic persona, while Donald Duck (Citation1955), who detests the film, finds that Fernandel manages to provoke the odd laugh in spite of the dreadful dialogue and inadequate screenplay. Several critics credit Becker’s direction for Fernandel’s ‘modesty’ [pudeur] and ‘sobriety’ [sobriété] (Baroncelli Citation1954), in a performance that is ‘more human … and more moving’ than the Ali Baba of the tale (Chazal Citation1954).Footnote39 For others, however, it is Fernandel who does his best to hold the audience’s interest in a slow-moving, dry film (Carrefour Citation1954); a farce lacking in gags (Sadoul Citation1955). What is particularly notable is the recurring use of a vocabulary associated with quality, restraint and ‘good taste’ in relation to a popular comedy and to Fernandel, a star with an excessive, physical performance style characterised by grimaces, nods and winks to the audience and an infectious, corporeal laugh (Vincendeau Citation2012).

Figure 6. Oriental fairytale and farce rendered in ‘sumptuous’ colour: Ali Baba (Fernandel) and Morgiane (Samia Gamal) triumph.

This question of taste – defined in opposition to vulgarity and excess – also features in relation to the use of colour: the prevailing view can be summarised as ‘so much better than the Americans’. Cinematographer Robert Lefebvre is singled out alongside Becker here as responsible for images, which are seen as ‘meriting the highest praise’ (Sadoul Citation1955); ‘the most beautiful colour images of French cinema’ (Chazal Citation1954); ‘a magnificent, gleaming picture book’ (Arlaud Citation1954); ‘irreproachable and in perfect taste’ (Truffaut Citation1954b); ‘gleaming, sumptuous images’ (Rochereau Citation1955).Footnote40 Doniol-Valcroze (Citation1954b) is more qualified (‘ravishing colour, if a little flat’), but for L’Express (Anon Citation1955), the colour is where Becker ‘triumphs’ [triomphe], the only aspect of the film that can be praised unequivocally.Footnote41 Even across these reviews drawn from publications as diverse as Arts, Les Lettres françaises, Paris Presse, Le Figaro and Le Canard enchaîné, the clash between an apparently auteurist impulse to seek out elements of Becker’s signature style – many of which are also seen as indicators of quality, such as restraint, subtlety, taste, careful attention to details in the mise en scène, even authenticity – and the requirement to judge the film as a popular comedy is very evident.

This tension between ‘quality’ and ‘popular’, framed in terms of the relationship between the auteur-director and his material, also emerges in responses to Becker’s next film, Arsène Lupin. Like Ali Baba before it and Montparnasse 19 afterwards, Arsène Lupin was not the film Becker was planning to make; he seized the opportunity after failing to get finance for an original script, Vacances en novembre (‘November holidays’), set at the end of the First World War (Naumann Citation2001, 59). Like Ali Baba, Arsène Lupin presented its share of surprises, from the casting of Robert Lamoureux – another popular comic performer, famous for his stage and radio act and as the star of the recent comedy hit Papa, Maman, la bonne et moi/Father, Mother, the Maid and I and its sequel, Papa, Maman, ma femme et moi/Father, Mother, My Wife and I (Jean-Paul Le Chanois, 1954 and 1955) – to the decision not to use any of Leblanc’s Lupin stories but to write new ones.Footnote42 However, the film was also more easily assimilable to Becker’s œuvre than Ali Baba; in addition to Lupin’s kinship with Max le Menteur and other Becker characters, the Belle Époque setting recalled Casque d’or (the pair of apaches hired by Lupin in the episode of the President’s ball could have belonged to Leca’s gang). Furthermore, the main episode in Kaiser Wilhelm’s summer palace pays homage to La Grande Illusion/Grand Illusion (Renoir, 1937) through the use of Haut-Koenigsbourg as a location and the courtly rivalry between Lupin and the Kaiser, reminiscent of that of Boëldieu and Rauffenstein in the earlier film.Footnote43 On the surface, then, Arsène Lupin would seem to present more for cinephiles to get their teeth into. However, this time the critical reaction was even more mixed. There is a sense that emerges from the reviews in the corpus that Becker could be forgiven for one lapse of judgement, but this new popular venture was a step too far for a director of whom ‘more’ was expected. One unusual point of contention, given Becker’s passion for his characters, is the protagonist. He is seen as lacking depth and development (Mauriac Citation1957; Vivet Citation1957), transformed from the ‘strong and frenzied’ character of Leblanc’s novels to one which is ‘feeble, imprecise, blurred, non-existent’ (Truffaut Citation1957).Footnote44 These comments are set against almost universal praise for Lamoureux’s performance, which, as for Fernandel, is often ascribed to Becker’s direction. It is perhaps telling, though, that it was Lamoureux, not Becker, who reprised the character in a follow-up, Signé: Arsène Lupin/Signed, Arsène Lupin (1959), this time directed by Yves Robert, a long-time collaborator of the actor on stage and screen.Footnote45

The most common criticism, however, is a more familiar one for Becker’s films. The script is seen as lacking the intrigue and pace of Leblanc’s novels (Baroncelli Citation1957). France Roche (c. Citation1957) suggests that Becker’s attention to detail slows down the film, which never manages to achieve the ‘wild rhythm of Leblanc’s novels’.Footnote46 Truffaut (Citation1957), more severe, calls it ‘a film without line, without rhythm, that has run out of breath, so we spend our time looking at trinkets …’.Footnote47 For many, Lupin suffers from an excess of good taste; Becker has ‘polished’ [fignolé] the life out of his film (Baroncelli Citation1957). For others, though, this is why it succeeds: through its tone of detached irony and parodic panache (Canard enchaîné Citation1957); the ‘ease’, ‘elegance’ and ‘perfect taste’ of the mise en scène contrasted with the ‘extravagance’ and ‘implausibility’ [invraisemblance] of the story (Fressoz Citation1957); thanks to the ‘erudite meticulousness’ (Marion c. Citation1957), ‘wit’ and ‘impeccable taste’ of its ‘gentleman-director’ (Hérin Citation1957).Footnote48

What also emerges in these responses is the relationship between these indicators of quality and Frenchness, set against an inferior – and potentially pernicious – American influence. This Frenchness may in part derive from Becker’s association with Renoir, but it is mainly articulated by critics in terms of taste, in opposition to Hollywood coarseness. A number of reviews of Ali Baba contrast its tasteful use of colour and filming locations with garish Hollywood depictions of the ‘Orient’ – ‘pure Coca Cola style’ [pure style Coca Cola], in the words of Sadoul (Citation1955), – while Arsène Lupin is seen to offer a delightful (and nostalgic) alternative to the Série noire and the Lemmy Caution films in particular, seen as corrupting French film with American-style violence and vulgarity (Dubreuilh Citation1957) (see ). In this respect, ‘even’ Becker’s more ‘popular’ films are seen to encapsulate French ‘quality’, while Becker himself, in spite of his love of American culture (jazz, the Hollywood films of King Vidor, Erich von Stroheim and Howard Hawks, his tendencies at the cutting table), was embraced as a quintessentially French filmmaker, just as his Arsène Lupin is a ‘gentleman-cambrioleur bien de chez nous’, a mixture of Gavroche and d’Artagnan (Canard enchaîné Citation1957).Footnote49

Conclusion

As a transitional figure, then, Becker not only offers a bridge between classical and New Wave cinema but cuts across cinematic categories that were beginning to emerge in the 1950s, a reminder of the highly permeable and overlapping nature of labels such as auteur, popular and quality film. Historian Olivier Curchod summarises Arsène Lupin as ‘an attractive ornament of French quality cinema made by a great auteur’ (Gibert Citation2012), highlighting three elements of the debates discussed above: nationality, quality and authorship.Footnote50 If Arsène Lupin represented for Becker an effectively executed commission rather than a personal project – a Plan B adopted when he despaired of funding Vacances en novembre – it is nevertheless part of his œuvre, marked with his signature style and themes, as the critical continuity with which it was received demonstrates. In this way, it is analogous to those studio films of Hollywood directors such as Hawks or John Ford, who were celebrated by French critics as auteurs in spite of the commercial constraints they were subject to. Furthermore, Becker’s stylised realism, claimed (and critiqued) by both Bazinian and Sadoulian ‘schools’, bridged ideological divides thanks to the sense of care and attention to detail with which he portrayed his characters and their milieu; a sort of quality of the everyday, or, as one critic put it, a ‘comédie humaine’ of post-war France (Jotterand Citation1951). What this analysis has shown is that, far from being ‘diametrically opposed to all the tendencies of French cinema’ as Truffaut put it, in fact Becker’s films sit firmly at the nexus of these tendencies, indicative of a French quality that has its roots in the stylised realism of the 1930s films of Renoir or Clair, and which persists beyond the New Wave in the films of directors as disparate as Tavernier, Claude Sautet, Agnès Jaoui or Céline Sciamma, to name but a few. This is why these films, and the critical reactions to them, offer remarkable insights into issues that surfaced in relation to 1950s French production, but which are still in question today: film authorship, cinematic realism, definitions of quality, a concern with the script and the very idea of French national cinema.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Leahy

Sarah Leahy is Senior Lecturer in French and Film at Newcastle University. Her research focuses on French film history, with a particular focus on stars and screenwriters, and her publications include Casque d’or (I.B. Tauris 2007) and (with Isabelle Vanderschelden) Screenwriters in French Cinema (Manchester UP 2021).

Notes

1. For example, Dubreuilh (Citation1957), Laurent (Citation1957), Hérin Citation1957 and Vivet (Citation1957) love the film and celebrate this intimate depiction of the characters and setting. For Baroncelli (Citation1957) and Truffaut (Citation1957), on the other hand, the scene belongs to Becker but not to Arsène Lupin.

2. ‘Je n’ai jamais voulu (exprès) traiter un sujet.’ See also Néry (Citation1954), where Becker declares that he much prefers characters to stories.

3. ‘en marge des modes, et même le situerons-nous aux antipodes de toutes les tendances du cinéma français.’

4. As Truffaut also noted, Ali Baba is as much a creation of its star, Fernandel, as of its director. Vignaux (Citation2000, 164–165) cites clauses in Fernandel’s contract that show the extent of the star’s control over the musical numbers, script and the final cut. Although the original title of the film is technically Ali Baba et les 40 voleurs, this essay adopts the more common spelling of Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs.

5. The reference is to Nanook of the North (Robert J. Flaherty, 1922).

6. As Burnett points out (Burnett Citation2017, 87–88), at times Bresson also navigated in mainstream waters, especially in the earlier days of his directing career. Raoul Ploquin produced Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne/The Ladies of the Bois de Boulogne (1945), while Journal d’un curé de campagne/Diary of a Country Priest (1951) shared its production company (UGC) as well as an actor (Jean Riveyre) and composer (Jean-Jacques Grünenwald) with Édouard et Caroline.

7. See note below.

8. ‘le plus accompli et le plus équilibré de nos cinéastes’; ‘un maître, un grand maître’.

9. ‘réalisme’, ‘néorealisme’, ‘vérisme’, ‘vérité’, ‘authenticité’, ‘quotidien’, ‘banal’, ‘intimiste’, ‘simplicité’, ‘dépouillé’, ‘naturel’, ‘documentaire’, ‘naturalisme’, ‘néointimisme’. These particular examples are drawn from a sample of contemporary reviews found in the Cinémathèque française digitised press dossiers for Antoine et Antoinette, Rendez-vous de juillet, Édouard et Caroline, Casque d’or, Rue de l’Estrapade, Touchez pas au grisbi, Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs and Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin. These press cuttings are not exhaustive, but contain a range of types of publication, from large circulation dailies or weeklies (e.g. Paris Presse, France Soir, Carrefour, Franc-Tireur, Le Figaro, Le Monde, Libération), to Catholic (e.g. Témoignage chrétien, Radio-Cinéma, La Croix) or Communist (e.g. Humanité, L’Écran français) newspapers, and also including more specialist cultural or film weeklies or monthlies (e.g. L’Écran français, Radio-Cinéma, Arts, Nouvelles littéraires, France Observateur, L’Express, Cahiers du Cinéma).

10. In Sadoul’s review of Rue de l’Estrapade (1953), he evokes Antoine et Antoinette as a film whose strength and quality derives from its ‘hero’, the people of Paris, and hopes that Becker will one day return to ‘la réalité française et notre peuple’ (‘French reality and our people’).

11. ‘conscience artistique et le refus d’esthétisme gratuit’; ‘l’existence physique, morale et peut-être même métaphysique d’une certaine jeunesse d’aujourd’hui’.

12. Becker was a leading figure in Communist-inspired and funded filmmaking, working alongside Renoir on the Popular Front propaganda film La Vie est à nous/Life Is Ours (1936), contributing to the Ciné-Liberté collective and directing La Grande Espérance/The Great Hope (1937), a documentary about the ninth French Communist Party congress). His Communist involvement continued during the Occupation through Resistance activity.

13. ‘essayer de donner au spectateur une impression aussi exacte que possible de l’ATTITUDE des hommes et des femmes de la classe ouvrière parisienne dans leurs rapports avec leurs semblables’; ‘mon film ne pose aucune question [sociale] et n’avait nullement cette intention.’

14. ‘Peindre la réalité ou lui tourner le dos?’

15. ‘En fait de réalisme, qui dépasse aujourd’hui le Vidor de La Foule ou Greed de Stroheim ? Il est surtout question d’hommes et non de tendances ; loin de pousser les réalisateurs à s’engager dans telle voie ou telle autre, il faut au contraire les supplier de travailler suivant leur tempérament.’

16. This can also be seen in Becker’s defence of fellow filmmakers Bresson (Becker Citation1945) and Ophuls (Becker et al. Citation1956) and his homages to Renoir (Becker Citation1948) and Stroheim (Becker Citation1957).

17. This theory was set out in the preface to the March 1947 version of the script for Leenhardt’s first feature film, Les Dernières vacances/The Last Vacation (1948).

18. Numerous reviews highlight these aspects in Becker’s films: ‘a hoard of minute details’ [une foule de détails minuscules] (C. H. Citation1947); ‘the sense of truth in the detail … perfectly real beings’ [le sens du détail vrai … deux êtres parfaitements réels] (Nouvelles Littéraires Citation1951); ‘the revealing detail’ [le détail révélateur] (Jotterand Citation1951); ‘marvellously precise in the detail’ [merveilleusement exact dans le détail] (Lauwick Citation1950); ‘touching meticulousness … universe of the day to day’ [touchante minutie … univers du quotidien] (Bertrand Citation1948); ‘the significant detail […] minute, clever observations that strike the right chord’ [le détail significatif … toutes sortes de menues observations qui sonnent juste] (Gautier Citation1951); ‘it’s not invented, it’s observed’ [ce n’est pas inventé, c’est noté] (Arlaud Citation1954); ‘a thousand little everyday nothings’ [mille petits riens de tous les jours] (Le Monde 1947); ‘characters marked with an extraordinary authenticity’ [ses personnages empreints d’une extraordinaire authenticité] (Fabre Citation1953); ‘an accumulation of precisely observed details that draws us to the characters to the characters’ [une accumulation de détails exactement observés qui attache aux personnages] (Néry Citation1953).

19. For example, Favalelli (Citation1951): ‘precise little strokes, without ever pressing too hard on the brush’ [petites touches précises sans que le pinceau n’appuie jamais]. See also Le Monde (Citation1947) and Vermorel (Citation1947) on Antoine et Antoinette or Le Monde (Citation1949), Opéra (Citation1949) and Charensol (Citation1949) on Rendez-vous de juillet.

20. Giroud continued to collaborate with Becker, whom she had got to know on the set of La Grande Illusion. She published a synopsis of the ‘prequel’ for Antoine et Antoinette that she and Becker were working on at the time of his death, a sketch entitled ‘Virginity’ for the portmanteau film, La Française et l’amour/French Women and Love (Henri Decoin, Jean Delannoy, Michel Boisrond, René Clair, Henri Verneuil, Christian-Jaque, Jean-Paul Le Chanois, 1960). A note states that this would be replaced by a contribution from René Clair (Giroud Citation1960). However, in the eventual film, René Clair’s segment is entitled ‘Le Mariage’ (‘Marriage’), while the one on ‘La Virginité’ (‘Virginity’) was directed by Michel Boisrond and written by Annette Wademant.

21. Wademant was the principal screenwriter for these two films, drawing extensively on her own experiences for the characters and settings. Perhaps best known for her collaboration with Max Ophuls on Madame de … /The Earrings of Madame de… (1953), she also contributed to the writing of Casque d’or alongside Becker and Jean Companeez.

22. ‘la ténuité déconcertante de ses scénarios’

23. Marguerite Houllé-Renoir, Marc Maurette, Jacques Rivette and others recall Becker’s difficulty in deciding about camera angles and editing in particular (Valérie Vignaux Citation2000, 68, 115, 194).

24. ‘… si en peignant mes personnages avec soin je donne à certains l’illusion d’avoir voulu peindre mon époque (!) tant mieux, et c’est flatteur, mais il s’agit bien là d’une illusion, mes prétentions ne vont pas si loin ….’

25. See Vignaux (Citation2000, 195–208) and Claude Naumann (Citation2002) on the difficult genesis of this film.

26. Tu as l’habitude lorsque tu acceptes un sujet d’en tourner un autre. Tu n’as pas tourné Arsène Lupin, tu n’as pas tourné Casque d’or, mais tu as fabriqué des histoires qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec le sujet initial. Es-tu capable, pour une fois, de t’effacer ? Il faudrait que tu tournes notre scénario et pas autre chose.’ Henri-Georges Clouzot shared this view of Casque d’or, which he described as a ‘non-film’ [non-film], telling Simone Signoret that he would have done a better job with Martine Carol in the title role (Signoret Citation1975, 127).

27. ‘Le drame, c’est que Jeanson se refuse à comprendre qu’un scénario n’est pas un film terminé.’ Archives show that in fact Aurenche and Bost collaborated closely with directors such as Autant-Lara and René Clément on their scripts (Leahy and Vanderschelden Citation2021, 125).

28. Recurring terms include ‘purity’ [pureté], ‘charming’ [charmant], ‘sensitive’ [sensible], ‘simplicity’ [simplicité], ‘scrupulous’ [scrupuleux], ‘elegant discretion’ [élégante discrétion], ‘modesty’ [pudeur], ‘skilful découpage’ [découpage habile], ‘restraint’ [retenue] (Arlaud Citation1953; Baroncelli Citation1957; Bertrand Citation1948; Charensol Citation1949; Doniol-Valcroze Citation1954a; Gaillard Citation1950; Gautier Citation1951; Helsey Citation1947; Le Monde Citation1949; Mauriac Citation1947, Citation1954; Vermorel Citation1947), along with comments on the excellence and precision of the mise en scène (Hérin Citation1957; Jotterand Citation1951; Magnan Citation1947; Truffaut Citation1954b).

29. In this respect, they follow in the footsteps of the pre-war cinema of Renoir, Carné and others, where quality films were made for popular audiences.

30. O’Donoghue (Citation2018) also addresses the film’s grating Orientalism but suggests that this is redeemed by the final reel.

31. Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves was one of the tales that Syrian storyteller Hannā Diyāb told to the French Orientalist Antoine Galland, who added them to the first European translation of the 1001 Nights (Marzolph Citation2018, 115).

32. Gamal, a major star of both dance and film in Egypt and beyond, was known for her innovative mixing of traditional Egyptian dance, Latin and ballet. Among her many prior film credits is an Egyptian version of Ali Baba and the forty thieves (Togo Mizrahi, 1942).

33. 1954 was a bad year for women in Becker’s films; Jeanne Moreau and Dora Doll hardly fare any better in Touchez pas au grisbi.

34. ‘sans courir le risque d’une allusion au monde arabe contemporain’; ‘cet Orient de mille et une nuits, sans intérêts pétroliers ni revendications nationalistes.’

35. ‘l’Afrique arabe est juste en face de la Canebière.’

36. ‘un très joli spectacle’; ‘un divertissement réussi/de qualité/charmant … d’un goût parfait/du meilleur goût’; ‘un spectacle un peu mièvre mais joliment puéril.’

37. See Sadoul Citation1955 and Doniol-Valcroze Citation1954b. This view is also backed up by Astruc and Rivette (cited in Vignaux Citation2000, 165–166).

38. Zavattini, as several reviewers point out (Doniol-Valcroze Citation1954b; Donald Duck Citation1955; Rochereau Citation1955), was sometimes referred to as the father of neo-realism thanks to collaborations with de Sica, e.g. Sciuscià/Shoeshine (1946), Ladri de biciclette (1948), Umberto D (1952).

39. ‘plus humain … et plus touchant.’

40. ‘mérite les plus grands éloges’; ‘les plus belles images en couleurs du cinéma français’; ‘un magnifique et rutilant livre d’images’; ‘irreprochable et d’un goût parfait’; ‘images rutilantes et somptueuses.’

41. ‘couleur … continuement ravissante, encore qu’un peu plate.’

42. The script is co-authored by Albert Simonin.

43. Becker was a key contributor to La Grande Illusion: he appears fleetingly as the British soldier who stamps on his watch rather than hand it over to the Germans, but also acted as interpreter between Renoir and Stroheim and directed certain sequences himself (notably the final escape into Switzerland in the snow).

44. ‘fort et forcené’; ‘faible, imprécis, flou … inexistant.’

45. Becker, whose health was ailing in 1959, had perhaps learned from his previous three films. He put on hold a contract for Les Trois Mousquetaires – which was nonetheless a long-standing project – in order to prioritise the more intimate Le Trou (Naumann Citation2001, 80).

46. ‘le rythme délirant des romans de Maurice Leblanc.’

47. ‘un film qui n’a pas de ligne, pas de rythme, pas de souffle et l’on passe son temps à regarder les bibelots ….’

48. ‘aisance’, ‘élégance’, ‘goût parfait’, ‘extravagance’, ‘savante minutie’, ‘l’esprit’, ‘le goût très sûr’, ‘gentleman-réalisateur.’

49. ‘a home-grown gentleman-burglar.’

50. ‘un joli fleuron de la qualité française fait par un grand auteur’

References

- A. L.1955. Ali-Baba et les quarante voleurs, France Soir. 2 January.

- Andrew, D. 2007. “A Film Aesthetic to Discover.” Cinémas 17 (2–3) ( Spring): 47–71.

- Arlaud, R.-M. 1953. “Rue de l’Estrapade.” Combat, April 22.

- Arlaud, R.-M. 1954. “Ali-Baba. Quand Becker ouvre la fenêtre.” Combat, December 31.

- Astruc, A. [1948] 2022. “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La caméra-stylo.” In The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks, edited by Peter Graham and Ginette Vincendeau, 31–36. London: BFI/Bloomsbury.

- Baroncelli, J. 1954. “Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs.” Le Monde, December 27.

- Baroncelli, J. 1957. “Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin.” Le Monde, March 26.

- Bazin, A. 1953. “La Rue de l’Estrapade.” L’observateur d’aujourd’hui, May 14.

- Becker, J. 1945. “Hommage à Robert Bresson.” L’Écran français, October 7.

- Becker, J. 1947a. “L’auteur de film ? Un auteur complet.” L’Écran français, 123, November 4.

- Becker, J. 1947b. “Réponse de Jacques Becker à Roger Boussinot.” Action, November 12.

- Becker, J. 1948. “Hommage à Jean Renoir.” Ciné-club, April 6.

- Becker, J. 1953. “Allez donc au cinéma sans penser.” Arts, April 24, 408.

- Becker, J. 1957. “Nous avons perdu notre Dieu vivant.” Paris-Presse-L’Intransigeant, May 15.

- Becker, J., J. Cocteau, A. Astruc, R. Rossellini, J. Tati, Christian-Jaque, P.and Kast. 1956. “Défense de Lola Montès, Lettre ouverte au Figaro.” Le Figaro Littéraire, January 5.

- Bertrand, J. 1948. [ No title.] Nation Belge, February 13.

- Boussinot, R. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette.” Action, November 5.

- Burnett, C. 2015. “Under the Auspices of Simplicity: Roger Leenhardt’s New Realism and the Aesthetic History of Objectif 49.” Film History 27 (2): 33–75.

- Burnett, C. 2017. The Invention of Robert Bresson: The Auteur and His Market. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Canard enchaîné. 1957. “Le film qu’on peut voir cette semaine: Arsène Lupin.” 27 March. ( Cinémathèque Française archives, Kovacs 21 B4, Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin)

- Carrefour. 1954. “Jacques Becker et les quarante voleurs.” January 12.

- C. H. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette.” Paris Presse, November 4.

- Charensol, G. 1949. “Rendez-vous de juillet.” Les Nouvelles littéraires, December 22.

- Chauvet, L. 1954. “Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs.” Le Figaro, December 28.

- Chazal, R. 1954. “Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs.” Paris Presse, December 26.

- Dabat, G. 1947. “Peindre la réalité ou lui tourner le dos ?” L’Écran français, 121, October 21.

- Doniol-Valcroze, J. 1954a. “Touchez pas au grisbi.” L’observateur d’aujourd’hui, March 25.

- Doniol-Valcroze, J. 1954b. “Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs.” France Observateur, 242, December 30.

- Dubreuilh, S. 1957. “Arsène Lupin, ou allez vous rhabiller à la française, Lemmy Caution.” Libération, March 26.

- Duck, D. 1955. “Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs.” Le Canard enchaîné, January 5.

- Express. 1955. “Une histoire cousue de fil d’or.” 25, 2 January.

- Fabre, J. 1953. “Rue de l’Estrapade.” Libération, April 20.

- Favalelli, M. 1951. “En marge d’Édouard et Caroline, J. Becker a dessiné une caricature des salons mondains.” Paris Presse, April 14.

- Fayard, J. 1949. “Rendez-vous de juillet.” September 21.

- Fressoz, R. 1957. “Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin.” Témoignage chrétien, April 12.

- Gaillard, P. 1950. “Rendez-vous de juillet.” Parallèle, January 20.

- Gautier, J.-J. 1951. “Édouard et Caroline de Jacques Becker.” Le Figaro, April 11.

- Gibert, P.-H. 2012. “Jacques Becker a le nez creux.” In Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin. Supplement, DVD, Gaumont Video.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. 2006. “The Economy of 1950s Popular French Cinema.” Studies in French Cinema 6 (2): 141–150.

- Gimello-Mesplomb, F. 2014. “La Qualité comme clef de voûte de la politique du cinéma : retour sur la genèse du régime du soutien financier sélectif à la production.” In Le Cinéma : une affaire d’état, edited by Dimitri Vezyroglou, 85–102. Paris: Comité d’histoire du ministère de la Culture et de la Communication/La Documentation française.

- Giroud, F. c.1960. “Le dernier projet de Becker. La Française et l’amour.” No publication details (Cinémathèque Française archive, Sadoul 40 B3).

- Helsey, E. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette : favori numéro 1.” Aurore, September.

- Hérin, P. c.1957. “Lupin-Lamoureux.” No publication details (Cinémathèque Française archive, Kovacs 21 B4, Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin).

- Jeanson, H., and J. Becker 1957. “Une confrontation attendue.” Arts, August 14.

- Jotterand, F. 1951. “Un film de Jacques Becker: Édouard et Caroline.” Gazette de Lausanne, April 21.

- Laurent, J. 1957. “Deux heures avec Arsène Lupin.” Arts, April 3.

- Lauwick, H. 1950. “Rendez-vous de juillet.” Noir et Blanc, January 4.

- Leahy, S., and I. Vanderschelden. 2021. Screenwriters in French Cinema. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. [1947] 2008. Critique of Everyday Life, Volume 1. Translated by John Moore. London and New York: Verso.

- Le Monde. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette de Jacques Becker, à Cannes.” 21 September.

- Le Monde. 1949. “Rendez-vous de juillet.” September 18.

- Magnan, H. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette de Jacques Becker, à Cannes.” Le Monde, September 21.

- Magnan, H. 1951. “Édouard et Caroline.” Le Monde, April 14.

- Marescaux, G. 1954. “Touchez pas au grisbi.” L’Humanité, March 23.

- Marion, D. c. 1957. “Arsène Lupin.” No publication details. (Cinémathèque Française archives, Kovacs 21 B4, Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin).

- Marzolph, U. 2018. “The Man Who Made the Nights Immortal: The Tales of the Syrian Maronite Storyteller Ḥannā Diyāb.” Marvels & Tales 32 (1): 114–129, 198.

- Mauriac, C. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette de Jacques Becker.” Le Figaro littéraire, October 24.

- Mauriac, C. 1949. “Le Mal du siècle à l’écran.” Le Figaro littéraire, December 17.

- Mauriac, C. 1954. “Touchez pas au grisbi.” Le Figaro littéraire, March 23.

- Mauriac, C. 1957. “Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin.” Le Figaro littéraire, March 30.

- Merlin, O. 1953. “Rue de l’Estrapade.” Le Monde, April 20.

- Montarnal, J. 2018. “La Qualité française”. Un mythe critique ? Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Naumann, C. 2001. Jacques Becker. Entre classicisme et modernité. Paris: BiFi/Durante.

- Naumann, C. 2002. “Genèse d’un film. De ‘Modigliani’ à ‘Montparnasse 19’ (Jacques Becker, 1957).” Cinémathèque française. https://www.cinematheque.fr/article/996.html

- Néry, J. 1953. “Rue de l’Estrapade.” Franc-Tireur, April 21.

- Néry, J. 1954. “En bavardant à bâtons rompus avec Jacques Becker.” No publication details (Cinémathèque Française archive, Kovacs 21 B4, Jacques Becker).

- Nouvelles Litteraires. 1951. “Édouard et Caroline.” April 12.

- O’Donoghue, D. 2018. “Beyond the Visible: Realism in the Films of Jacques Becker.” Cineaste 44 (1) ( Winter): 18–23.

- Opéra. 1949. “Rendez-vous de juillet.” December 28.

- Phillips, A. 2018. “‘Unremarkable Paris’: Jacques Becker’s Urban Everyday.” In Paris in the Cinema: Beyond the Flaneur, Locations, Characters, History, edited by Alastair Phillips and Ginette Vincendeau, 207–217. London: BFI.

- Queval, J. 1952. “Casque d’or.” Radio-Cinéma-Télévision, May 4.

- Rivette, J., and F. Truffaut. 1954. “Entretien avec Jacques Becker.” Les Cahiers du Cinéma 32 (February): 3–17.

- Roche, F. c.1957. “Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin (hold-up-polka)”. No publication details. (Cinémathèque Française archives, Kovacs 21 B4, Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin).

- Rochereau, J. 1955. “Ali Baba.” La Croix, January 7.

- Ross, K. 1996. Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press.

- Sadoul, G. 1953. “Rue de l’Estrapade.” L’Humanité, April 30.

- Sadoul, G. 1955. “Mille et une nuits marseillaises.” Lettres françaises, 550, January 6.

- Signoret, S. 1975. La Nostalgie n’est plus ce qu’elle était. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Truffaut, F. 1954a. “Les Truands sont fatigués.” Les Cahiers du Cinéma 34 (April): 54–57.

- Truffaut, F. 1954b. “Ali Baba.” Arts, December 22.

- Truffaut, F. 1955. “Ali baba et la politique des auteurs.” Les Cahiers du Cinéma 44 (February): 45–47.

- Truffaut, F. 1957. “Arsène Lupin : un film décoratif.” Arts, March 27.

- Truffaut, F. 1964. “De vraies moustaches.” L’Avant-Scène Cinéma 43: 6.

- Truffaut, F. 2022. “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema.” In The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks, edited by Peter Graham and Ginette Vincendeau, 38–58. London: BFI/Bloomsbury.

- Vermorel, C. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette.” Spectateur, September 30.

- Vignaux, V. 2000. Jacques Becker ou l’exercice de la liberté. Liège: Éditions du Céfal.

- Vincendeau, G. 2012. “Fernandel : de l’innocent du village à ‘Monsieur Tout le Monde.” In Genres et acteurs du cinéma 1930–1960, edited by Delphine Chedaleux and Gwenaelle Le Gras, 134–155. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Vivet, J.-P. 1947. “Antoine et Antoinette.” Combat, November 9.

- Vivet, J.-P. 1957. “Lafcadio chez le Kaiser.” L’Express, March 29.