ABSTRACT

Since 2004 there has been a debate surrounding two streets and a square in Berlin’s Wedding district that bear the names of perpetrators of German colonialism: should the streets be renamed or simply be rededicated to other German men bearing the same surnames? Through struggles over street renaming within the African Quarter of Wedding, we show how processes of marginalization, racialization and whiteness are negotiated through the situated materiality of local spaces, yet these negotiations are continually tied to wider national and global struggles. We draw on critical whiteness studies, as well as post- and de-colonial theory, to examine what discourses are employed by groups agitating for and against street renaming and how these debates are covered by the international, national and local media. The paper unpacks the disconnection between present day racializing practices and colonial histories, highlighting how recognizing racism is connected to how colonialism has been dealt with (or not) in Germany.

Introduction

Since 2004 there has been a heated debate about the renaming of two streets, Petersalle and Lüderitzstraße, and the square of Nachtigalplatz in the African Quarter (AQ) of Berlin’s Wedding district which are named after figures who occupied central roles in Germany’s colonial period. On Friday, December 2, 2022, the debate came to a close, as Lüderitzstraße and Nachtigalplatz were finally renamed, replacing references to colonial figures with two important Africans who were active in resisting German colonialism ().Footnote1 This highly localized struggle around the renaming of streets provides insights into issues that stretch far beyond Wedding. It connects to movements like Rhodes Must Fall that “have challenged the veneration of historical figures that promotes settler colonialism, imperialism, slavery, and other forms of racialized violence” (Beebeejaun & Modarres, Citation2020, p. 7), but also to movements such as Black Lives Matter, and de-colonial initiatives across the Global North, which have foregrounded Europe’s colonial history and its enduring racisms within public discourse. By exploring the example of street renaming in Wedding, we aim to understand how processes of racialization (including whiteness) and remembering the colonial period manifest on the local level.

Figure 1. The transition between street names in Wedding, as Lüderitzstraße is changed to Cornelius-Fredericks Straße.

Given the material, symbolic, and interactional inscription of the colonial past onto urban space (Jacobs, Citation1996), struggles over renaming are also struggles over how to remember the past and the role of race in local, national, or transnational memory. Given Trouillot’s notion of history as something material that begins with physical bodies, artifacts, and actors undergoing processes that produce and narrate, then history is being produced across a range of sites that move from the streets to the media to the academy (Carby, Citation2015). Reflecting on Trouillot’s work, Carby (Citation2015) highlights what is at stake in the past: how it is remembered is the future itself, and what that future can become. History is being struggled over through the everyday mobilization of activists and counter-campaigners contesting pieces of steel on street corners that narrate and produce pasts, presents and futures to come. Street naming is not only a political action, but an “act of signification that produces a city-text, a form of public commemoration that constitutes places of memory, a medium through which struggles for social justice are materialized, and a performative enactment of sovereign authority over the spatial organization of cities” (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2018, p. 309). Street naming comes to encapsulate both “a seemingly mundane aspect of urban administration” while also making up “the very foundations of urban spatial imaginaries,” which features as a fundamental mechanism for “historicizing space and spatializing history” (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2018).

Given that Wedding is a highly diverse neighborhood (see below), street names can have a profound impact on feelings of belonging. Streets named after colonial perpetrators can be read as a sign of Germany’s incapability or unwillingness to actively deal with its colonial past and to address the injustices that stretch into the present. Germany’s colonial empire lasted from about 1884 to 1919. While colonial fantasies certainly lived on throughout the Nazi era (see e.g., Conrad, Citation2011), Germany’s relatively short period of empire in comparison to other colonial powers means that “Germany’s colonial past is to a large extent ignored by the official remembrance policies of the Federal Republic” (Conrad, Citation2011, p. 196). The colonial period is often romanticized (Conrad, Citation2011), and there is an “amnesia in regards to colonial genocide” (Melber, Citation2005, p. 146). This “amnesia” has only been addressed in recent years, triggered through events such as demands from Herero people for reparations, the restitution of museum artifacts, or heated debates about how museums (fail to) contribute to adequately address Germany’s colonial past. The renaming of streets, which is actively supported by the Berlin Senate and also occurs in other German cities, is a key example of how the remnants of colonialism are remembered are central to current day struggles connecting the local, national and transnational levels. Memory practices shape who is positioned as part of the nation.

Against this background, our paper aims to explore how mundane, yet fundamental practices of naming situated in the urban local are tied to Germany’s colonial past, processes of racialization, and belonging. By examining arguments for and against street renaming, we ask (1) how different groups’ positions and present day racism relates to how Germany has dealt with its colonial past, (2) how does whiteness reside in the materiality of the city and come to racialize bodies via how people orientate themselves to objects such as street signs and the discourses built around them, and (3) how do different groups of people—regarding their racialization and supposed local insider/outsider status—construct claims of belonging? By paying attention to how the local, national and global intersect in the analyzed arguments, we aim to address the relative dearth of literature that connects street renaming struggles across local and global contexts. We take calls for a “critical confrontation with the colonial remnants” scattered around cities seriously, and understand our paper as a contribution to urban decolonization (Ha, Citation2014, p. 30; see also Thompson, Citation2020 regarding Paris). Importantly, our paper also addresses calls to make race a central element of urban analysis (Beebeejaun & Modarres, Citation2020; Picker, Citation2017). We do so by focusing on the claims to belonging asserted by racialized people, but also by attending to how “urban whiteness” (Shaw, Citation2007, p. 2) is defended through “acts of defensiveness and aggression, and cultures of denial and indifferences to the unpleasantness of contemporary city life.”

Firstly, we provide an overview of literature relevant to understanding how racism and whiteness feature in European nation building and belonging, whereby the debris of colonialism is reflected through urban space. After presenting our methodology and data, we describe the arguments put forward by local groups and the media in favor of and against street renaming in Wedding. The arguments, alongside discussion in the popular press, show how racialization and belonging work in our present. How this colonial past should be handled is tied to current processes of racialization and the reification of whiteness, while also highlighting the interrelation of local, citywide and national processes.

The (post) colonial significance of race in Europe

Across much current scholarship, it is commonly accepted that race is a social construct, rather than something “real” or durable. Following Goldberg, race represents “a way (or a set of ways) of being in the world, of living, of meaning-making” (Goldberg, Citation2008, p. 152). Processes of racialization are dynamic and fluctuate across time and space (Virdee, Citation2019). Colonialism was founded on and justified through racial hierarchies, placing “some in a natural situation of inferiority” (Quijano & Ennis, Citation2000, p. 533), as the development of racial thinking was imperative to the development of modernity (S. Hall, Citation1991). While most formerly colonized countries have gained independence, remnants of the colonial period endure, described by Quijano as the “coloniality of power” (see also Boatcă, Citation2020). Although it has mobilized race and racism for processes of nation building and exclusion, Europe has also frequently denied the relevance of race, particularly since the end of World War II (Lentin, Citation2008). Among European countries, Germany in particular grapples with the question of if and how race should be discussed due to its centrality in the Shoah and subsequent censorship (Boulila, Citation2019; Lentin, Citation2008). As mentioned above, the colonial period and its after-effects are only slowly finding their way into the German politics of remembrance. Nevertheless, race and racialization are still largely absent from public, political and statistical discourses, yet they continue to have “real material and symbolic effects” on those who are racialized as nonwhite (S. Hall, Citation2002, p. 453).

Frequent claims that we live in a post-racial era gives racism a more flexible or “motile” character (Lentin, Citation2016, p. 35). Racism in post-racial times does not end, but can be made to apply to an ever-wider set of circumstances and people, while racialized people themselves are no longer permitted to define racism. Through racism’s “post-racial universalization,” it can be presented as an experience that anyone can perpetuate and that can affect us all equally, which means that “only those who constitute themselves as universal(ist), underpinned by the confected white, western ‘standards’ of objectivity and rational thought, are accorded the right to define the contours of racism” (Lentin, Citation2016, pp. 35–36). Referencing Song, Lentin notes how racism’s universalization disconnects it from its “historical basis, severity and power” (Song, Citation2014, p. 107, in Lentin, Citation2016, p. 37). This disconnection between present day racializing practices and colonial histories is relevant to the struggle for street renaming, as it highlights how recognizing present-day racism is deeply connected to how colonialism has been dealt with (or not) in Germany. While there has been attention to racialization and postcolonial struggles enacted through street naming processes (Aikins & Kopp, Citation2008), there has been a limited focus on understanding how whiteness is also asserted and sustained through opposition to street renaming (although see below, Bönkost, Citation2017).

Racialization and belonging in urban space

We position belonging as both a feeling of being “at home” and a political project (Yuval-Davis, Citation2006). As Fenster (Citation2005) posits, belonging is intimate as well as official in its nature. Through street renaming struggles we see these forms of belonging united, as official and formal belonging claimed through the signs of the city act as a conduit for feeling “at home” in a place. This belonging is about social inclusion and political representation, whereby histories are remembered or forgotten through the material and discursive elements of the city. BIPoC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) residents can see themselves represented or forgotten, as belonging happens in relation to what is remembered and how. Schien, writing about how African Americans in Kentucky are denied citizenship and the right to claim belonging, raises the possibility for “an oppositional politics of belonging in which land and landscape figures as a practical stage upon and through which citizenship and community can be practiced” (Schein, Citation2009, p. 811). In a similar vein, we can see an oppositional politics of belonging operating through street renaming which stakes a claim to belong via everyday urban material infrastructures, connecting the personal to more political projects of belonging. Centering the role of race (including whiteness) in the analysis of claims to local belonging foregrounds “processes of exclusionary whiteness” (Shaw) that occur despite the (local or wider) society’s diversity. Thus, the renaming of streets can act as a means of BIPoC people practicing and claiming belonging in Europe.

Whiteness continues to act as a key indicator of national and European belonging (Müller, Citation2011), with visible minorities, such as BIPoC or Muslims, constantly othered in European societies (El-Tayeb, Citation2011). From a social constructivist approach, whiteness has often been tied to privilege, innocence and invisibility (Frankenberg, Citation2001). Writing on media reactions to street naming campaigns in the African Quarter, Bönkost (Citation2017) employs the concept of white fragility and white stress to highlight “negative white emotions that the making visible of racist relations of power and inequality, which disguise the normality of racism, triggers” (Bönkost, Citation2017, p. 2). Using the lens of white fragility can provide a powerful tool to interrogate whiteness by attending to its invisibility, lack of accountability, and assumed innocence (Hunter & van der Westhuizen, Citation2021, p. 19). Yet, Hunter and van der Westhuizen counter that the concept does not adequately deal with the affective and material dimensions of whiteness—pointing to how white fragility can re-essentialize subjects so that whiteness becomes synonymous with the white body, rather than something that also works as a formation.

In contrast, phenomenological and affective approaches to whiteness highlight, for example, how whiteness is not only inhabited by white bodies, but can be approximated and worn by racialized bodies to show affinity to the “somatic norm” of whiteness (Puwar, Citation2004). In her phenomenological approach, Ahmed (Citation2007) describes how whiteness acts as a form of orientation. She describes how we inherit the reachability of some objects, yet this does not mean that “whiteness” itself features as a “reachable object,” but that whiteness becomes an orientation placing certain things within our reach, which includes not only physical objects, but also styles, capacities, aspirations, and habits (Ahmed, Citation2007, p. 154). In the context of debates in Wedding, whiteness is often not explicitly recognized, but is talked about through terms like local versus outsider. Taking a phenomenological approach explores how the whiteness of the objects already “in place” works to extend some bodies (and histories) while limiting others (Ahmed, Citation2007). The orientating power of the street sign does not just indicate the name of a corridor for passage, but the visibility, meaning and legibility of particular histories accompany this passage. The notion of whiteness as a formation that always already belongs to Europe is challenged and destabilized through street sign changing campaigns.

Processes of racialization occur within and through urban space. Place and space are also constructed and imbued with meanings through people and processes that are beyond, yet also include, the level of the street or neighborhood. We are inspired by Suzanne Hall’s attempt to “write the street as world” (S. M. Hall, Citation2021, p. 152), highlighting that local issues need to be understood across spatialities and temporalities, always being attentive to how local processes are always related to global histories of colonialism and imperialism. We focus on how the material and symbolic space of the streets are influenced and feedback on to “the world.” Space also plays a key role in shaping how process of belonging and social (in)justice unfolds.

Research design and methodology

The paper is based on an analysis of a variety of (mostly) local documents that address the contentious issue of street renaming in Wedding. These include the arguments put forward by the groups involved in the struggle for or against the renaming of streets within the African Quarter, such as the Initiative Pro African quarter (IPA) which was against renaming, and initiatives such as “Decolonize Berlin” and Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland (ISD, Initiative Black People in Germany), who fought for the renaming. The documents are derived from groups’ websites and public statements. In a second step, we analyze the media discourse. Media debates provoke and shape discourses on race, racism and the nation. Titley (Citation2019) highlights how racism features as a subject of continuous “debatability” with a constant contest about what and whose reality is valid in assessing what counts as racism. This is “a process that renders it (racism) a matter of opinion and speculative churn, not history, experience and power” (Titley, Citation2019, p. 3). We consulted all newspaper articles published on the renaming of streets in Berlin, with a specific reference to the African Quarter, between the dates of 2009 and 2022. We searched for relevant articles via Google and LexisNexis, which cumulatively yielded 163 results. Most are from Berlin based newspapers such as the left-leaning Taz, the right-leaning Berliner Zeitung and the more centrist Tagesspiegel, but there are also several articles in the national press, including Die Welt, Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, and the Süddeutsche Zeitung. The media coverage is concentrated between 2017 and 2019, with over half of the reports accessed being produced during these years. This coincides with the decision to rename streets being officially approved, and the process of choosing names and objections to renaming being lodged. As central to discourse analysis (Blommaert, Citation2005; Keller, Citation2006; Wodak & Reisigl, Citation1999) we focus on the positions and arguments of the main actors involved, the framing of their arguments, what is problematized and what is left unsaid. For the media debate, we ask similar questions, but focus in more detail on how the local debate is embedded in wider societal issues, how different media outlets report on the issue, and which actors are foregrounded. Through an analysis of the debates and arguments of various actors, we attend to how competing realities are asserted and claimed as valid and how history, experience and power are either evoked or ignored.

Context: Multicultural wedding

Wedding is a neighborhood in the northern part of Berlin and part of the Mitte district. Wedding has 180,633 inhabitants, about two thirds of which have a so-called migration background, meaning that they or one of their parents has migrated to Germany. Next to long-term white German residents, the population includes residents with a Turkish family background, but also intra-European migrants from Italy, Poland and Bulgaria, migrants from former Yugoslavia, Russia, Ukraine, from Islamic countries (including all OIC countries) and from Arab countries (counting countries from the Arab League), notably Syria and Lebanon.Footnote2 Wedding is a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood, with lower levels of education, income and a higher unemployment rate. Nevertheless, there are pockets of gentrification, particularly in neighborhoods close to the canal and close to a major square.

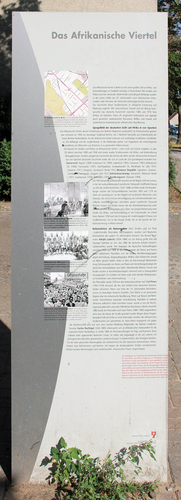

The “African quarter” (AV), a neighborhood in the eastern part of Wedding, is filled with streets that are named after places in Africa, many referring to places from former colonies, as well as central figures from the colonial era (). In the early 1900s, Carl Hagenbeck proposed the local park as a site for a human zoo displaying Africans from the German colonies; this never came to fruition due to the start of World War I. The adjacent English Quarter was named in honor of King Edward VII, who was also the Emperor of India. Thus, Wedding contains many references to Germany’s colonial period, the awareness of which is high, particularly within the AV. Each One Teach One (EOTO), an organization offering a variety of services and events for Black Germans, has its offices there, and several individuals and organizations offer tours through the neighborhood that examine Wedding’s colonial traces. Wedding provides a rich context to examine what struggles over street renaming can tell us about processes of whiteness and racialization connected to colonial histories.

Remembering colonialism differently

The groups in favor of street renaming include the local coalition parties (Social Democrats, the Greens, the Left) and local and national organizations representing Black Germans and their allies like Berlin Postkolonial e.V., Initiative Schwarzer Menschen in Deutschland (ISD), and Decolonise Berlin. Berlin Postkolonial e.V. is a citywide organization that aims to critically deal with Berlin’s colonial history and highlight the colonial and racist elements inscribed in urban space. ISD was founded in 1985 following the publication of Farbe bekennen, the first book about Afro Germans published by a Black feminist collective including May Amin. One of their many goals was to provoke a “decolonial culture of memory in the city.” Together with the Berlin Senate for Culture and Europe, the organizations started the project Dekoloniale as a response to “ever louder demands for a consistent change of perspective in the postcolonial culture of remembrance,” whereby opponents of colonial racism and exploitation should be honored rather than colonial actors. The debate around street renaming is thus part of a much broader national project fought for by Black Germans and other activist groups to acknowledge and deal with Germany’s colonial history. In 2010, the initial proposal to re-name the AV streets came from Mnyaka Sururu Mboro, a founding member of Dekolonial Berlin e.V., and Tahir Della, a longtime activist in the ISD, who also organized walking tours through Wedding’s colonial traces.

It was only in 2016—6 years after the first demand—that the local council and coalition parties decided to rename two streets and a square. Local residents were invited to submit proposals for names which a jury comprised of activists and council members selected. From the beginning, the renaming of streets was positioned as an important way of dealing with German colonial history. For Postkolonial Berlin, it was not only important to remove the names of colonial perpetrators, but to select new names that changed the perspective of remembering, shifting the focus to those who fought against colonialism. This demand was accepted by the Senate.

In the first selection round, the committee mistakenly selected Queen Nzinga from Ndongo and Matamba. Nzinga was certainly a leader in the fight against Portuguese colonial aspirations, yet she was also involved in the slave trade. Following a local outcry and mockery of the entire process, the jury procedure was declared a failure. The local council responded by selecting a panel of historians who provided an assessment of the proposed names. The council selected four new names, honoring the Manga Bell couple and their fight against German colonialism in Cameron, and Cornelis Fredericks who fought in Namibia. The renaming of the second street is still outstanding, but the names are selected: Anna-Mungunda-Allee and Maji-Maji-Allee. Anna Mungunda was the first Herero woman who supported the fight for independence. Maji-Maji refers to the largest liberation struggle against German colonialism, which took place between 1905 and 1907 in “German-East Africa.” After the official announcement of the new names, the district mayor Stefanie Remlinger from the Greens said “street names represent honors and are part of the remembrance culture.” Due to more than 400 legal complaints sent to the local council, the renaming process was stalled for several years. After the final renaming in December 2022, Anna Yeboah from Dekoloniale stated: “With the long overdue street re-naming, Germany’s largest colonial area monument will become an important anti-colonial learning and remembrance site.” This quote shows how the very localized renaming of streets serves a nationwide purpose and significance, namely to turn the AV into a place of learning and remembering about German colonialism.

Transplanting the names of white colonial perpetrators with Black Africans who were active in the fight against colonialism also impacts upon how whiteness figures in processes of remembering history. Mbembe asserts that to move forward into different human futures, we must alter how we remember, thereby also demystifying whiteness:

Human history is about the future. Whiteness is about entrapment. Whiteness is at its best when it turns into a myth. It is the most corrosive and the most lethal when it makes us believe that it is everywhere; that everything originates from it and it has no outside. (Mbembe, Citation2015, p. 3)

In this way, street renaming campaigns work to demythologize (urban) whiteness by breaking through the version of history that these signs represent(ed) and perpetuate(d). Renaming becomes part of the project of producing other versions of history outside of whiteness, thereby extending the space of belonging for racialized persons and their ability to assert their racial identity in urban space(s). This forges a future via histories that are not about entrapment inside mythologized whiteness, but about actively working to create plurality and make whiteness less omnipresent. This is relevant on the local, the national, but also on a global level—as illustrated by the presence of a delegation from Cameron, including the Duala King Emoumbou and his wife, at the renaming ceremony.

Local issues and “useless symbolic policies”

The Initiative pro Afrikanisches Viertel (IPA), together with the Christian Democrats, argued against the renaming of Wedding’s streets. Initially a loose group of residents, the IPA became an organized initiative led by lawyer Karina Filusch and Johann Ganz to counteract “the obvious aspirations of people from outside the African Quarter, to politicize the discussions and to organize advocacy.”Footnote3 The IPA claims to advocate for open discussions “free from ideological standpoints and moralizing arguments”—a statement that draws a clear boundary against the proponents of renaming and testifies to the hostile attitude (in contrast to just mere indifference) toward the implied groups. Instead of renaming streets, they aim to rededicate them. They argue that Petersalle has already been re-dedicated, from a colonial figure to a Christian Democratic politician and they would follow this model, suggesting dedicating Nachtigalplatz to theologist and writer Johann Carl Christoph Nachtigal and Lüderitzstrasse to the town of Lüderitz in Namibia, which is named after the same German colonial figure. The IPA organized several local meetings to discuss the topic and their proposals, inviting residents and local politicians from all parties. What stands out is that the IPA never directly engaged in a conversation or confrontation with the groups supporting the renaming; none of the groups were invited to join the meetings and they are never explicitly named in interviews with the IPA, although the IPA continually position themselves, albeit implicitly, against such groups. They thus avoided the “unpleasant” (Shaw, Citation2007) part of living with diversity, never engaging face-to-face, but always putting forward their arguments from their “safe” place of “exclusive whiteness” (Shaw, Citation2007, p. 2). The IPA’s major argument refers to conceptions of insiders and outsiders, arguing that people who do not live in the neighborhood are advocating for the renaming of streets, when local residents and shop owners should decide. The initiative forcefully lobbied that re-dedication was sufficient to deal with Germany’s colonial history and complied with the wishes of locals, who would be negatively affected by re-naming because of the costly bureaucracy related to changing street names. The IPA claimed that there was not enough local participation, referencing the mishap with Queen Nzinga to critique and invalidate the entire process. Criticizing the local government and aiming to maintain the status quo results in the perpetuation of racial inequalities and white privilege (Bonilla-Silva & Forman, Citation2000). White privilege becomes hidden behind the argument of local privilege. Localness is often mobilized as a justification to dictate how spaces are marked. Hence space is equated with being, or with one’s identity (Massey, Citation1994). Space becomes tied to stability and continuity, providing “a comforting bounded enclosure’ allowing us to return to a “stable past” with a “seamless character” (Massey, Citation1994, p. 168). This appeal to localness, stability and boundedness is employed by the campaigners. In the process, whiteness becomes localized despite Wedding being a highly diverse neighborhood, thereby restricting the space where racialized people can feel belonging to or assert their racial/cosmopolitan identity.

When the decision about renaming was passed by the local council in 2018, the IPA wrote, “Ostensibly, the name change was intended to change your view of colonialism. The red-red-green resolution majority thus assumes that your world view and level of information are primarily determined by street names.” This sarcastic and hurt statement ignores any possible relation between local materialities and wider processes of remembrance. It only accounts for a white perspective, without reflecting on how street renaming might affect (Black) Germans—local or not—who have to endure the lasting effects of colonial rule that translates into persistent racial hierarchies and present-day racisms. To attempt to reverse the decision, the IPA called on their members and all locals to file legal complaints against the decision. The initiative cited the cost of address changes and wasted tax money for “senseless and useless symbolic policies” as key grounds for complaint, illustrating again the lack of understanding of the proponents of street renaming. Citing the potential costs of street renaming is another example of what Shaw (Citation2007, p. 2) calls the “unpleasantness of contemporary city life,” which for these white residents consists in being told how to deal with the local expression of Germany’s colonial past.

While the IPA largely avoids addressing the issue of race, they instrumentalize race for their own purposes by directly referring to an unsuccessful attempt to rename the town of Lüderitz in Namibia, arguing that if a town named after a German colonial figure continues to exist in Namibia, it could also exist in Germany. Yet this is a highly partial account. Namibia was colonized as “German South West Africa” between the 1880s and 1915, and many material structures date back to this era, including street names. Places like Otjozundijii became Swakomund, as Heroro or Nama names were transplanted by German ones as an assertion of power, and because local names were difficult for colonizers to pronounce (Mbenzi, Citation2019, p. 74). Attempts to rename streets have occurred in several Namibian cities like Windhoek, and we can see similar counter arguments like cost or undemocratic processes used to oppose this (Mbenzi, Citation2019; Yankson, Citation2023). Namibian President Pohamba asked in a 2012 state of the nation address why there was a Lüderitz in Namibia, and subsequently, Lüderitz was officially renamed—something that the IPA conveniently omits from debates (Mbenzi, Citation2019, p. 93). Referring to Lüderitz creates a closed circle of self-referential whiteness, or as Mbembe describes, everything here originates from whiteness. There is no exterior to whiteness, as the persistence of colonial names on streets in Germany are justified through Germany’s colonial conquest in Namibia. The conflict, as narrated by the IPA, is about recognizing situated, local wishes versus recognizing more spatially diffused national imperatives. In this way, the IPA attempts to sever the expression of colonial histories through the AV’s street signs from wider issues of how colonial pasts should be confronted. The IPA unties the micro from wider national and international struggles by focusing on the economic burden for local businesses and framing the uniting of micro and macro concerns as disingenuous. They also present the pro-renaming campaign as mobilizing skin color to accomplish instrumental goals irrelevant to the space of Wedding. They fashion a dividing line that supposedly transcends pigmentation, despite the body and its pigmentation featuring as inescapable fault lines of how the colonial and post-colonial continue to be organized.

Re-dedicating the streets to different white men bearing identical surnames ties to what Hunter and van der Westhuizen (Citation2021, p. 2) call the “invisibility-ignorance-innocence triad” that is often expressed through predominant epistemologies of critical whiteness studies. The street re-dedication fits this triad in many ways—by attempting to ignore history and whiteness by focusing on localism and practicalities in public discussions whilst simultaneously attempting to restore innocence to the materiality of these signs through an invisible shift of reference point. Hunter and van der Westhuizen describe how whiteness knowing itself can become part of its successful reproduction, as it can recognize its problematic aspects, address them and then carry on innocently again. However, “this relies on the same possessive, narcissistic mastery logic of coloniality, whereby the white subject knows and controls, mind over matter” (Hunter & van der Westhuizen, Citation2021, p. 2). This attempt to retain control is evident within the re-dedication campaign, as it recognizes the problem without making substantive alterations. Innocence is restored by re-dedicating the streets to less offensive white men, rather than changing their names entirely. This retains not only whiteness, but male whiteness—albeit in a less blemished form. While whiteness remains tacitly invisible in discussions around rededication, it can retain its innocent visibility on the street sign and remain imbedded in urban materiality. After having presented the arguments of various local, city- and nationwide actors in favor and against the renaming, we now turn to how street renaming was negotiated in the media.

Media discourses: Reception of the conflict in the press

There are notable differences between the international and national coverage, and the local coverage of street renaming. The former is overall more sympathetic to renaming, with some sectors of the local press comparatively revanchist in their approach. In the following, we will describe four articles in more detail, as examples of the discursive support of the renaming or re-dedication campaign. Unsurprisingly, the press coverage that is supportive of renaming foregrounds the voices and arguments of Black activists and devalues the arguments put forward from the IPA. Two articles illustrate this well, namely one based on a radio feature on Deutschlandfunk Kultur (DFK; Götzke, Citation2019) and one from The Guardian (De Souza, Citation2017). In both texts, arguments from activists such as Mnyaka Sururu Mboro from the NGO Decolonise Berlin, and ISM activist Tahir Dalla are foregrounded, while those of the IPA are less prominent. In the DFK article, Mboro and Dalla are cited as addressing two key assertions made by the opposition: firstly, that Nachtigal was not “that bad”—thus expressing a romanticized picture of the German colonial period and the involvement of its central figures. Mboro is cited as objecting to the notion floated by IPA campaigners that Nachtigal supported “ending slavery” as being “complete nonsense.” Secondly, the article argues that street renaming is a small, yet integral part of a much wider reckoning of German society with colonial histories. Dalla presents the struggle as about who is honored and who has the power to choose who is honored. He emphasizes the need for mutual respect and engagement, citing that the opposition group is keen for stasis. For Dalla, changing the street sign is the first and easiest step in a much longer struggle of getting Germany to recognize its colonial history after 100 years, thus connecting the localized struggle to wider issues. The IPA spokesperson Filusch mentions the instrumentalization of skin color and the continual presence of advocates, placing the IPA campaign inherently in opposition to the spokespeople of ISM and Decolonise Berlin.

The Guardian article picks up on the topic of how street renaming relates to how Germany remembers its colonial history. They start with a description of the neighborhood, explaining that while only six percent of residents have an African background, the AV bears its name due to colonial histories. It also features pictures of Della and activists who have held mock renaming ceremonies by holding up new homemade street signs. This active demonstration of change highlights re-dedication as comparatively a nonevent, bereft of the physical movement of replacement and visual difference. They quote Della to cite the emotional impact of street names, connecting the struggle in the AV to global campaigns like Rhodes Must Fall. He describes how “It’s a slap in the face of black people every time they walk through these streets honoring those who committed the most serious of crimes in Africa.” This quote illustrates how the struggle to rename streets is also a struggle to belong, which not only affects locals, but all Black people (and those who want Germany to recognize its role in colonialism) who walk around in this neighborhood or have any relation to it. The Guardian article queries Berlin’s selective capacity for memorialization, highlighting how historical changes to Berlin signage are not a new phenomenon. Streets have been repeatedly renamed throughout the pre- and post-Nazi era and during the Cold War division. While the city has been praised for its handling of Nazi atrocities, colonialism is much more removed from “public consciousness.” While both articles recount some of the IPA’s arguments against renaming, their sympathies are clear. Both articles cite Della who says street rededication arguments show how groups like the IPA do not understand what they are advocating for, or they place the IPA campaign inherently in opposition to the spokespeople of ISM and Decolonize Berlin. While the two articles in favor of the street renaming stem from a national and an international news outlet, it is important to note that left-leaning local media also supported the street renaming, notably the taz, while the Tagesspiegel had positive and ambivalent coverage of the topic.

Two clearly dismissive articles featured in the right-leaning Berliner Zeitung. The first one (Schupelius, Citation2016) question whether the names of colonial rulers should really disappear from the urban landscape, thus feeding into the romanticization and trivialization of German colonial rule. The author positions Berlin as a city of memories where history is always being reassessed and negotiated. Part of this is assessing whether someone is “too guilty” to be honored. In the piece, the BZ asks the reader to ask how “bad” these colonial masters really were in comparison to murderers and war criminals, especially as 130 years have passed since their deaths—implying that the passage of time lessens their culpability. We are asked to disconnect these men from the historical impact their names signify, as well as the wider impact of colonialism as a system. To take down the names of men who perpetuated colonial logics is positioned as “overzealous,” despite the history of genocide. After inviting us to consider their possible innocence, the author performs a small concession: while we should be critical of colonial history, this does not require removing their names, but explaining and classifying them. This argument is rooted in a standpoint of whiteness, which disregards the effect these street names might have on racialized people. The author also mentions the “big nuisance” that street renaming causes for local residents. The one-off nuisance of a new postal address seems more taxing than how BIPoC might feel about seeing these street names and the intergenerational damage that colonialism has wrought. BZ presents the arguments of the IPA as a more workable alternative to the erasure of colonial names and concludes by citing the Christian Democrat’s support of the IPA’s alternative rededication program, asserting that this is what compromises “look like.” However, this does not really constitute a compromise, given that the street signs continue to “look like” they did before and remain uninterrupted by the names of People of Color.

The last article illustrates how arguments of reverse racism are constructed in reaction to street renaming in Wedding. BZ author Seidl (Citation2017) opens his piece by describing how Portuguese explorer Gaspar de Lemos landed on the coast of South America and designated the area as Rio de Janeiro against the advice of the local Tupinambá. This example, to him, shows how “Emissaries of a supposedly enlightened and civilized society decreed the fate of the local population in the name of a higher good, who were denied the right to determine their own fate. And so it is sometimes still today.” He then skips across time and space to arrive in Wedding, where he describes how street renaming also takes place “against the will of local people who are not trusted to reflect, for example, on the role of the doctor and explorer Gustav Nachtigal in the German colonial empire,” a statement that uses a similarly hurt and sarcastic approach to that of the IPA. Referring to the jury’s selection process, Seidl argues that colonialism’s legacy is being addressed through a reimposition of colonial logic whereby supposed outsiders decide the “fate” of insiders, and Wedding residents should defend themselves against this ignorant conceit. Here an imagined—white—public in Wedding are being dominated by a foreign and arrogant power imposing its own agenda.

Street renaming advocacy groups, including significant amounts of BIPoC, suddenly take on the role of colonizer in Wedding. Through pushing for redress in the face of colonial histories, previously colonized and presently racialized groups are positioned as the oppressive power in a move that subverts power. This argument ignores that many campaigners for street renaming were born in Germany, or they now live here and have a stake in German society as citizens and residents. This ties back to how racialized people are seldom allowed to define what constitutes racialization; racism is presented as something ahistorical that could be inflicted on anyone. A divisive class dynamic is embedded within this discourse through the idea of an enlightened emissary who arrives in Wedding, i.e., a middle class, educated and diverse group who implicitly decides what a more working-class white population should do. This illustrates Hunter and van der Westhuizen’s claim (Hunter & van der Westhuizen, Citation2021, p. 3) that “Whiteness now comes to rely on the dualism of white savior/traumatized victim, because what white subjects can ‘save,’ they can contain and control. Pluralism and incompleteness are the basic threats to whiteness.” The plurality introduced by street renaming threatens to take the power of control away from whiteness, leaving it fragmented and incomplete. This threat to whiteness is attached not simply to the white body or white people, but to the material matter of the street sign (see Berg & Ramos-Zayas, Citation2015; Blickstein, Citation2019).

Conclusion

The renaming of Berlin streets challenges how Germany is dealing with its colonial past and shows how the treatment of the colonial period remains largely disconnected from Germany’s present. Referencing the colonial genocide, Melber describes how “the treatment of the issue (intentionally or not) avoids any references to the subsequent developments in Germany” (Melber, Citation2005, p. 144). Here, the denial of human value to native Namibians was based on the “structurally racist set-up of colonialism” and this same colonial racism acted as a “fertile breeding ground” for radical anti-Semitism (Melber, Citation2005, p. 145). Rebuttals against street renaming in Germany highlight these disconnections. While the extermination of the Nama and Herero tribes was classified by the United Nation’s Whitaker Report in 1985 as the first genocide of the 20th century, the lack of recognition of this history allows the names of colonialists to remain on street markers—something unthinkable for the names of National Socialists. The struggle to rename Wedding streets is bound up with remembering differently and giving voice to colonial encounters so that un/mis-remembered “silences speak and, in the process, lay claim to the future” (Carby, Citation2015, p. viii). Bhambra (Citation2007, p. 2) argues that a key aspect of this process lies in pursuing connected sociologies whereby the West as privileged “‘maker’ of universal history” is eschewed as a categorization—something she feels is embedded within the very notion of Eurocentrism. She also highlights how “if our understandings of the past are inadequate it follows that our grasp of the present will also be inadequate” (Bhambra, Citation2007, p. 2). Renaming is bound up with new, more adequate ways of remembering that shifts toward recognizing the multiplicity of history-makers functioning outside Western logic. It also exposes the “exclusive whiteness” that both implicitly and explicitly resides within many urban spaces, and how this whiteness is challenged or defended.

The struggle to rename streets is also a struggle over how spaces should be imagined as relating to one another. A quick tour through AV’s U-Bahn station with its images of giraffes and meerkats, to street signs denoting rivers in Africa, to shops selling goods from around the world, evidences modernity’s lack of geographical limitations (Bhambra, Citation2007). The arguments supportive of renaming recognize how local street names connect to citywide, nationwide and global questions around how Germany’s colonial period should be remembered and how this connects to issues of belonging. Similar struggles to remove the names of German colonizers are simultaneously taking place within the streets of Namibia, highlighting how the global relationship between former African colonies and European colonialists manifest within local street signs and monuments from the streets of Berlin to Windhoek. The activism taking place through Rhodes Must Fall or Black Lives Matters is global in its vision, yet this activism always manifests in and through local material spaces so that the local and global are inextricably intertwined. As Massey reminds us, the space of the local is not stable or continuous in nature; instead, it is porous, unbounded and always connected to elsewhere. In contrast, the arguments against street renaming highlight how only certain aspects of the intertwining of global and local should be acknowledged: that Lüderitzstrasse in Berlin comes to signify the Lüderitz port city of Namibia provides a crude example of Eurocentric forms of remembering. The politics of naming connects to history and power via what names are afforded legibility in the city and how legibility is tied to granting value and legitimacy.

Regarding issues of racialization, the demands of the IPA and its resistance to visible change ties to oblique, disavowed claims of whiteness whereby the material of the street sign itself is imbued with a whiteness that IPA campaigners are loath to relinquish. Here we can see how whiteness “works as a formation, a logic and an assemblage whereby the material, symbolic and affective are interconnected” (Hunter & van der Westhuizen, Citation2021, p. 2). The IPA’s Filusch denounces the debates around street renaming as “political and ideological.” While the IPA may present re-dedication as the politically innocent and common-sense choice of the victimized underdog, their campaign is deeply political given that there is no place to consider these issues outside of politics, ideology and history. The desire for the street sign shows how it possesses the cultural and affective lure of whiteness through its materiality. This is also about the restoration of an innocence that is defended in aggressive ways; whiteness can become cleansed and reified through the sign’s subtle re-dedication. The spatial environment offers unconscious feelings of either comfort or discomfort; as Ahmed describes, the experience of discomfort is not that of sinking comfortably into a space, but of feeling that the spaces occupied “do not ‘extend’ the surfaces of our bodies … To be not white is to be not extended by the spaces you inhabit. This is an uncomfortable feeling” (Ahmed, Citation2007, p. 163). This impacts on who can/is supposed to belong to certain places. The analysis clearly shows that the IPA views belonging as only open to those who live in the neighborhood, while at the same time disregarding if not mis-representing the area’s diversity. To include the names of BIPoC therefore invites the space to extend beyond whiteness, arguably providing a modicum of comfort. Re-dedication does not disrupt this discomfort, but retains a space for whiteness to extend itself without allowing for plurality.

We also have the use of globally employed right-leaning arguments where local government is portrayed as inept, power hungry, and non-democratic. Here the “real” citizen on the street is silenced and inconvenienced through ideological zealots positioned as reactionary. As Bönkost (Citation2017) has also indicated, there is little mention of racism in the media coverage. While we see important alliances developing that defy simplistic racial categorizations, it is hard to ignore that the IPA spokespeople against renaming are white and the spokespeople in the press arguing for renaming are Black. Notably, this tense dynamic is not acknowledged in the media, but silently present. Bönkost describes how the only time “racism” is used in media coverage is when The Tagesspiegel claims that the jury focusing on choosing Black, female personalities is racist. This notion of reverse racism ties back to Lentin’s comments on the universalization of racism, whereby reverse racism acts as a close companion to the notion of reverse colonialism. Through analyzing struggles in the AV, we can gain a better understanding of how racialization and classification process work through the material spaces of Berlin. Renaming is enacted on the local level and portrays the tensions between a nationwide discourse and how this discourse becomes locally and materially enacted in urban space.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our anonymous reviewer for the numerous helpful comments they provided.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christine Barwick-Gross

Christine Barwick-Gross is a sociologist, working at the Interdisciplinary Centre for European Studies at the Europa-Universität Flensburg. Her research covers themes related to the sociology of Europe, migration and mobility studies, and urban theory. She has previously held positions at Humboldt University Berlin, the Centre Marc Bloch Berlin and the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics at Sciences Po Paris.

Christy Kulz

Christy Kulz is a sociologist whose research interests center around how intersectional classificatory systems like race, class and gender are historically constructed in relation to particular formations of space and power, and how these shifting signifiers are (re)made through everyday practice. Kulz is a postdoctoral researcher at the Technical University Berlin; prior to this she was a Leverhulme Trust Fellow at the University of Cambridge.

Notes

1. The renaming of Petersallee is still outstanding, due to residents’ legal objections.

3. All quotes are derived from their website (https://www.pro-afrikanisches-viertel.de/index.php) at the beginning of 2023. It seems that the IPA closed their website after the streets were officially renamed. They still have a Facebook page, but the last post is from 2019 (https://www.facebook.com/proafrikanischesviertel).

References

- Ahmed, S. (2007). A phenomenology of whiteness. Feminist Theory, 8(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700107078139

- Aikins, J. K., & Kopp, C. (2008) Dossier: Straßennamen mit Bezügen zum Kolonialismus in Berlin. https://www.africavenir.org/fileadmin/downloads/occasional_papers/Dossier_kolonialistische_strassennamen.pdf

- Beebeejaun, Y., & Modarres, A. (2020). Race, ethnicity and the city. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City, 1(1–2), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/26884674.2020.1787754

- Berg, U., & Ramos-Zayas, A. (2015). Racializing affect: A theoretical proposition. Current Anthropology, 56(5), 654–677. https://doi.org/10.1086/683053

- Bhambra, G. (2007). Rethinking modernity: Postcolonialism and the sociological imagination. Palgrave.

- Blickstein, T. (2019). Affects of racialization. In J. Slaby & C. von Scheve (Eds.), Affective societies: Key concepts (pp. 152–165). Routledge.

- Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Boatcă, M. (2020). Thinking Europe otherwise. Lessons from the Caribbean. Current Sociology, 21(3), 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120931139

- Bonilla-Silva, E., & Forman, T. A. (2000). ’I am not a racist but … ‘: Mapping White college students’ racial ideology in the USA. Discourse & Society, 11(1), 50–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926500011001003

- Bönkost, J. (2017). Straßenumbenennung als weißer Stressfaktor und die Notwendigkeit über Rassismus zu lernen. IDB Institut für diskriminierungsfreie Bildung.

- Boulila, S. (2019). Race in post-racial Europe. Rowman and Littlefield.

- Carby, H. (2015). Imperial intimacies: A tales of two islands. Verso.

- Conrad, S. (2011). German colonialism: A short history. (Sorcha O’Hagan, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

- De Souza, A. N. (2017, April 27). Germany’s other brutal history: Should Berlin’s ‘African Quarter’ be renamed? The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/apr/04/germanys-other-brutal-history-should-berlins-african-quarter-be-renamed

- El-Tayeb, F. (2011). European others. Queering ethnicity in postnational Europe. University of Minnesota Press.

- Fenster, T. (2005). Gender and the city: The different formations of belonging. In L. Nelson & J. Seager (Eds.), A companion to feminist geography (pp. 242–257). Blackwell.

- Frankenberg, R. (2001). The mirage of an unmarked whiteness. In The mirage of an unmarked whiteness (pp. 72–96). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822381044-005

- Goldberg, D. (2008). The threat of race: Reflections on racial neoliberalism. John Wiley & Sons.

- Götzke, M. (2019). Wie in Berlin um einen Straßennamen gestritten wird. Deutschlandfunkkultur. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/widerstand-gegen-manga-bell-platz-wie-in-berlin-um-einen-100.html

- Ha, N. (2014). Perspektiven urbaner Dekolonisierung: Die europäische Stadt als ‘Contact Zone‘. sub\urban zeitschrift für kritische stadtforschung, 2(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.36900/suburban.v2i1.106

- Hall, S. (1991). Europe‘s other self. Marxism Today, August, 18–19.

- Hall, S. (2002). ‘In but not of Europe’: Europe and its myths. Soundings, 22, 57–69.

- Hall, S. M. (2021). The Migrant’s paradox: Street livelihoods and marginal citizenship in Britain. University of Minnesota Press.

- Hunter, S., & van der Westhuizen, C. (2021). Viral whiteness: Twenty-first century global colonialities. In Hunter, S. & van der Westhuizen (Eds.), Routledge handbook of critical whiteness studies (pp. 1–28). Routledge.

- Jacobs, J. M. (1996). Edge of empire. Routledge.

- Keller, R. (2006). Analysing discourse. An approach from the sociology of knowledge. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 31(2 (116), 223–242.

- Lentin, A. (2008). Europe and the silence about race. European Journal of Social Theory, 11(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431008097008

- Lentin, A. (2016). Racism in public or public racism: Doing anti-racism in ‘post-racial’ times. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096409

- Massey, D. (1994). Space, place and gender. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mbembe, A. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive. “Africa is a country,” contributed by Angela Okune. Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography. Retrieved April 6, 2023, from https://worldpece.org/content/mbembe-achille-2015-%E2%80%9Cdecolonizing-knowledge-and-question-archive%E2%80%9D-africa-country

- Mbenzi, P. A. (2019). Renaming of places in Namibia in the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial era: Colonising and decolonising place names. Journal of Namibian Studies, 25(2019), 71–99.

- Melber, H. (2005). How to come to terms with the past: Re-visiting the German colonial genocide in Namibia. Afrika Spectrum, 40(1), 139–148.

- Müller, U. (2011). Far away so close: Race, whiteness, and German identity. Identities Global Studies in Culture & Power, 18(6), 620–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2011.672863

- Picker, G. (2017). Racial cities: Governance and the segregation of Romani people in Urban Europe. Routledge.

- Puwar, N. (2004). Space invaders: Race, gender and bodies out of place. Berg.

- Quijano, A., & Ennis, M. (2000). Coloniality of power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533–580.

- Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D., & Azaryahu, M. (2018). The political life of urban streetscapes: Naming, politics, and place. Routledge.

- Schein, R. H. (2009). Belonging through land/scape. Environment and Planning A, 41(4), 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1068/a41125

- Schupelius, G. (2016, March 20). Müssen die Namen der Kolonialzeit aus dem Afrikanischen Viertel verschwinden? Berliner Zeitung. Retrieved September 27, 2023, from https://www.bz-berlin.de/archiv-artikel/muessen-die-namen-der-kolonialzeit-aus-dem-afrikanischen-viertel-verschwinden

- Seidl, C. (2017, June 12). Afrikanisches Viertel: Das Verfahren zur Straßenumbenennung in Wedding ist skandalös. Berliner Zeitung. Retrieved September 27, 2023, from https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/mensch-metropole/afrikanisches-viertel-das-verfahren-zur-strassenumbenennung-in-wedding-ist-skandaloes-li.39485

- Shaw, W. S. (2007). Cities of whiteness. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Song, M. (2014). Challenging a culture of racial equivalence. The British Journal of Sociology, 65(1), 107–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12054

- Thompson, V. (2020). Decolonizing city spaces and images. Black Collective Solidarity and conviviality in Paris. Darkmatter Hub (Beta). https://darkmatter-hub.pubpub.org/pub/hzzpjlmx/release/1

- Titley, G. (2019). Racism and media (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Virdee, S. (2019). Racialized capitalism: An account of its contested origins and consolidation. The Sociological Review, 67(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118820293

- Wodak, R., & Reisigl, M. (1999). Discourse and racism: European perspectives. Annual Review of Anthropology, 28(1), 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.175

- Yankson, E. (2023). Street naming and political identity in the postcolonial African city: A social sustainability framework. Journal of Urban Affairs, 45(3), 685–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2023.2166839

- Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Belonging and the politics of belonging. Patterns of Prejudice, 40(3), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220600769331