Abstract

Introduction

Health disparities are commonly identified within the transgender and gender-diverse community. Gender minority stress theory expands the existing minority stress theory to identify the unique stressors of this community. The outcomes of these stressors and disparities are recurring negative experiences among transgender and gender-diverse youths and subsequent care avoidance. This mixed-methods systematic review aims to identify and critically analyze the effect of interventions to improve the healthcare experiences of transgender and gender-diverse youths.

Methods

Studies published from inception until April 2023 were sought from CINAHL Plus with Full Text, PubMed, Academic Search Complete, PsycArticles, PsycInfo, ERIC, SocIndex, target journals, trial registries, and countries with significant transgender and gender-diverse academic outputs. Studies were double screened for eligibility. The included studies were critically appraised and assessed for risk of bias. Data were extracted and convergent segregated synthesis was conducted to synthesize evidence from various research designs.

Results

In total, 4487 records were identified. Of those, nine studies were included, and three narratives were identified: components of intervention design, impact of the intervention on transgender and gender-diverse youths, and impact of the intervention on healthcare providers. Interventions were predominantly education-based, in-person, targeted healthcare providers and assessed knowledge, beliefs, confidence, and understanding of transgender healthcare. Transgender and gender-diverse focused education interventions demonstrated more significant differences in outcomes when compared with LGBT + focused interventions. Interventions that included social contact with transgender and gender-diverse individuals demonstrated more significant outcomes in both beliefs and knowledge.

Conclusion

A targeted approach to the development and delivery of interventions is needed to improve outcomes, including the co-production of interventions, specific content, and the application of social contact with youths.

Introduction

Trans and gender diverse (TGD) youth are at an increased risk of healthcare disparities (Johns et al., Citation2023; Wittlin et al., Citation2023). Healthcare disparities are defined as variations in healthcare accessibility due to unique social, economic, and environmental factors (Braveman, Citation2014). In comparison to their cisgender peers, TGD youth are more likely to experience violence, stigma, discrimination, and negative mental and physical health outcomes (Call et al., Citation2021; Hunt et al., Citation2020).

A common lens to view disparities is the minority stress theory, developed by Meyer (Citation2003). This theory posits that the stressors resulting from social stigma, discrimination, and prejudice can have adverse effects on the mental and physical health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations (Meyer, Citation2003). Hendricks and Testa (Citation2012) extended this minority stress model to include the TGD community resulting in the development of gender minority stress theory. The stressors of the TGD community were incorporated further to reflect the disparities unique to this community. The theory postulates that stressors experienced uniquely by TGD individuals result in negative mental and physical health outcomes (Hendricks & Testa, Citation2012).

The World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) released version 8 of the Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People to help provide gender-affirming care (Coleman et al., Citation2022). These standards call for the need to educate all healthcare providers on TGD healthcare needs, enabling them to provide an appropriate standard of care for TGD youth.

In their recent systematic review of 16 studies, conducted in the USA (n = 7), Australia (n = 3), Canada (n = 3), and the UK (n = 3) exploring the experiences of TGD youths within healthcare, Goulding et al. (Citation2023) found that such experiences were predominantly negative, particularly in primary care and mental health settings. Healthcare providers’ lack of knowledge in TGD healthcare was identified as a key cause of negative experiences (Goulding et al., Citation2023). Additionally, misgendering (i.e. use of incorrect pronouns), deadnaming (i.e. using someone’s assigned name instead of their chosen name), and lack of adequate care provision were frequently identified by TGD youth (Goulding et al., Citation2023). As such, a review of interventions is warranted to critically analyze their effect.

The aim of this mixed-methods systematic review was to identify and critically analyze the effect of interventions used to improve the healthcare experiences of TGD youth. The review objectives were to: (i) identify interventions to improve the healthcare experiences of TGD youths; (ii) report on the effect of interventions to improve the healthcare experiences of TGD youth; (iii) evaluate the element(s) of interventions (e.g. structure and provision) to improve the healthcare experiences of TGD youth; and (iv) identify the experiences of TGD youth and healthcare staff of the implemented intervention(s).

Materials and methods

This review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute methodological guidelines for mixed-methods systematic reviews (Stern et al., Citation2021). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist guided the reporting of this systematic review (Page et al., Citation2021). A protocol was registered through the Open Science Framework: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/57XMG.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were formulated based on the review aim and objectives using the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome framework (Richardson et al., Citation1995). Studies were eligible for inclusion if they identified the healthcare experience of TGD youths post-intervention (primary outcome), included populations under 18 years of age, and described an intervention to improve the experiences of TGD youths. Studies were included if they identified the impact of LGBT + or TGD youth interventions on pediatric healthcare providers. Additionally, studies including non-pediatric healthcare providers were also included provided the intervention content was specifically focused on TGD youth (secondary outcome). All primary research designs were considered for inclusion. Excluded studies were those that did not include: TGD youths under 18 years of age, an intervention element, or did not identify the effect of the intervention.

Information sources and search strategy

A search was completed in CINAHL Plus with Full Text, PubMed, Academic Search Complete, PsycArticles, PsycInfo, ERIC, and SocIndex. The AIDS Care—Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV journal was searched as it was not indexed in any of the above databases and was identified as having high TGD health research outputs (Sweileh, Citation2018, Citation2022). Further details of these identified journals can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Synonyms of the keywords “Intervention,” “Transgender and Gender-diverse,” “Youth,” and “Healthcare” were used and subject headings were utilized as appropriate. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used along with smart searching functions, where possible.

The trial registers ClinicalTrials.gov, Clinical Trials Registry EU, and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched, according to the guidelines by Hunter et al. (Citation2022). The keywords “Transgender and gender-diverse” and “Healthcare” were identified. A limit of “Adolescent or Child” was adopted where applicable. Full details of the search can be found in .

Table 1. PICO eligibility criteria and search strategy.

Grey literature databases BASE, WorldCat, and Google Scholar were also searched. Keywords were identified as “transgender,” “youth,” “intervention,” and “healthcare.” Countries that produced the highest amount of TGD health research output were identified, details can be found in Supplemental Table 1 (Sweileh, Citation2018, Citation2022). The health services and local transgender organizations of these countries were identified, and a search was completed. Details of the grey literature search can be found in .

Table 2. Grey literature search strategy.

Selection process

All identified records were imported into Covidence, an online software system used to streamline and facilitate the conduct of reviews (Veritas Health Innovation, Citation2023). Duplicates were automatically removed. A double screening approach was used for title and abstract screening. Full texts of the remaining records were retrieved and double screened. Records not meeting eligibility criteria were excluded. Screening conflicts were resolved by a third author. Relevant included materials were hand searched.

Data collection process

Data from included studies were extracted into a standardized table (Goulding et al., Citation2023). Headings of this table included: Author, year, country, and setting; sample size and identity descriptors; design; analysis; description of the intervention; data collection; and impact of the intervention on TGD youth or healthcare providers. Data were extracted by one author and cross-checked for accuracy by the remaining authors. Detailed findings inclusive of statistical evidence are included in the full data extraction table (Supplemental Table 2). A condensed data extraction table can be found in .

Table 3. Condensed data extraction table (n = 9).

Critical appraisal and risk of bias assessment

The Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies (Hong et al., Citation2018). Voting on quality items was conducted on a “Yes,” “No,” and “Cannot Tell” basis.

All quantitative non-randomized, randomized controlled trials (RCT), and experimental quantitative aspects of mixed-methods studies were assessed for risk of bias using Cochrane guidance (Higgins et al., Citation2019). The Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2; Sterne et al., Citation2019) tool was used to assess the risk of bias in RCTs across five domains. Each domain included signaling questions that were judged on a “Yes,” “Partially Yes,” “Partially No,” “No,” and “No Information.” Each domain received a risk of bias rating which informs the overall risk of bias rating.

The Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I; Sterne et al., Citation2016) tool was used to assess the risk of bias in non-randomized studies and experimental quantitative elements of mixed-methods studies. The ROBINS-I tool assessed for risk of bias within studies across seven domains. Each domain includes signaling questions that are judged on a “Yes” (Y), “Partially Yes” (PY), “Partially No” (PN), “No” (N), and “No Information” (NI). Each domain was given a risk of bias judgment which informed the overall risk of bias rating. Critical appraisal and risk of bias assessment were conducted by one author and cross-checked for accuracy by the remaining authors.

Synthesis methods

A convergent segregated approach was used to synthesize quantitative and qualitative data (Stern et al., Citation2021). This approach was chosen as the review sought to identify the effect of interventions as well as TGD youths’ experiences of the interventions. The convergent segregated approach commenced with a separate synthesis of qualitative and quantitative data (Stern et al., Citation2021). A narrative summary of quantitative and qualitative data was conducted as part of this synthesis due to the heterogenous nature of the studies. Following the separate development of narratives, a comparison of results was completed to integrate the evidence identified (Stern et al., Citation2021).

Results

Study selection

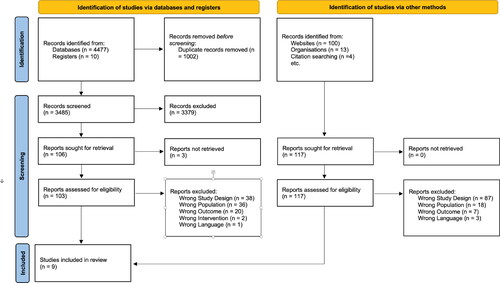

A total of 4487 records were identified from databases and trial registries. Once imported to Covidence, 1002 records were automatically removed as duplicates. Following this, 3485 records were screened at title and abstract and a further 3379 records were excluded. A total of 106 articles were sought for full-text retrieval, resulting in 103 articles being retrieved. Authors of the three studies not retrieved were contacted and outcome data were received from one study; however, findings were not published yet, and approval to use the data was not granted by the authors. A full text review of the 103 studies was completed and six studies were included based on eligibility criteria.

A further 117 studies were identified through grey literature sources and hand searching of citation lists. Following full text review, three studies were deemed eligible for review. In total, nine studies were included in this review. The full study selection process is presented in .

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers, and other sources (Page et al., Citation2021).

Study characteristics

Of the included studies, six were conducted in the United States of America (USA), two in Australia, and one in Switzerland. Study designs included mixed methods (n = 4), quasi-experimental (n = 4), and RCT (n = 1). The target population of seven studies was healthcare providers. Interventions were delivered either in-person (n = 5), online (n = 2), or using a hybrid model (n = 2). Intervention types varied across all nine studies. TGD youth samples ranged from n = 14 (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021) to n = 196 (Sequeira et al., Citation2022). Healthcare provider samples ranged from n = 20 (Vance et al., Citation2017) to n = 11,090 (Staggs et al., Citation2022). A more detailed overview of the study characteristics can be found in .

Table 4. Study characteristics of included studies (n = 9).

Critical appraisal

All nine studies had clear research questions and collected data that addressed the research question. All four quantitative non-randomized studies recruited participants that represented their target population and administered the intervention as intended. No quantitative non-randomized study presented completed outcome data, and two used appropriate measurements (Sequeira et al., Citation2022; Wahlen et al., Citation2020).

Within the RCT (Martin et al., Citation2022), all participants adhered to the assigned intervention, and all groups were comparable at baseline. It was not possible to identify if randomization was appropriately performed or if outcome assessors were blinded to the intervention performed. Complete outcome data for this study were not presented.

All four mixed-methods studies represented target populations appropriately and all measurements were appropriate regarding the outcome and intervention. No studies controlled for confounders; however, all participants in the four studies adhered to the intervention administered. Complete outcome data were only presented by Dahlgren Allen et al. (Citation2021) and Riggs (Citation2021). A qualitative approach was appropriate and qualitative data collection methods were adequate within two studies (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Dahlgren Allen et al. (Citation2021) and Riggs (Citation2021) sufficiently substantiated their interpretations based on the data. Findings were adequately derived from the data and there was coherence identified between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation within three studies (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Riggs, Citation2021). One study provided an adequate rationale for using a mixed-methods design, effectively integrated the components of the study, adequately interpreted outputs of the integration, adequately addressed divergences and inconsistences, and adhered to the quality criteria of each method involved (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). All four mixed-methods studies addressed divergences and inconsistences between results. Details of critical appraisal can be found in .

Table 5. Critical appraisal mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT; Hong et al., Citation2018).

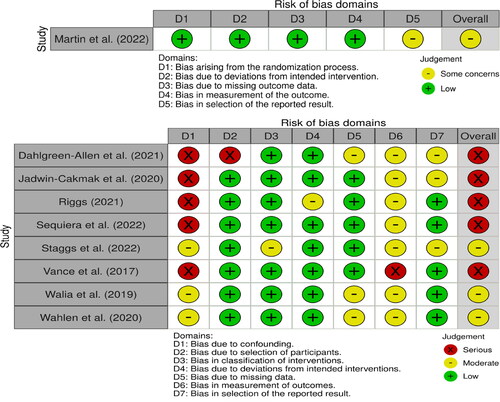

Risk of bias

Using the RoB2 tool, the RCT by Martin et al. (Citation2022) was judged as low risk of bias for domains 1–4. Some concerns were noted within domain 5, bias in the selection of the reported result. An overall judgment of some concerns was recorded for this study.

The risk of bias in the eight remaining studies was assessed using the ROBINS-I tool. All studies were judged to be a moderate or serious risk of bias due to the potential for confounding. Dahlgren Allen et al. (Citation2021) was identified as a serious risk of bias due to utilizing a historical control group. Staggs et al. (Citation2022) was judged to be at a moderate risk of bias relating to the classification of the intervention used. Riggs (Citation2021) received a moderate risk of bias scoring due to deviations presented relating to the intended intervention. Three studies were judged to be at moderate risk for bias relating to incomplete presentation of data (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019). Bias relating to measurements of the outcomes was judged to be moderate in seven studies and serious in Vance et al. (Citation2017). A moderate risk of bias was noted in three studies in relation to the selection of the reported results (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Staggs et al., Citation2022).

An overall serious risk of bias rating was identified in five studies (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Riggs, Citation2021; Sequeira et al., Citation2022; Vance et al., Citation2017). All remaining studies were assigned a moderate risk of bias rating (Staggs et al., Citation2022; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019). Results for the RoB2 and ROBINS-I tools were illustrated in , using the robvis tool (McGuinness and Higgins, Citation2021).

Three overarching narratives were identified including components of intervention design; impact of the intervention on TGD youth; and impact of the intervention on healthcare providers.

Components of intervention design

Intervention design varied widely across the included nine studies in terms of target population, intervention type, and development methods. Healthcare providers were the main population in seven studies. Staggs et al. (Citation2022) targeted healthcare providers as part of their intervention and assessed outcomes using TGD service users. Dahlgren Allen et al. (Citation2021) targeted TGD youths as their primary population and assessed the impact of the intervention on the youths. Sequeira et al. (Citation2022) identified behavior change in healthcare providers through the review of TGD youth’s healthcare records.

Of the interventions identified, eight were education-based aiming to improve healthcare providers’ knowledge of LGBT+ (n = 2), TGD youths (n = 4) healthcare and the use of affirming name and pronouns (n = 2). The remaining study tested the effect of a waitlist intervention aimed to improve the mental health and wellbeing of TGD youth (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021).

Methods to develop the interventions varied across studies. Co-production with TGD youth was identified in two studies (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2022). As part of intervention development, Jadwin-Cakmak et al. (Citation2020) engaged principles in community-based participatory research. Involvement with academic partners, a steering group of community-based organizations, and a youth advisory board inclusive of LGBT + adolescents were key components (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Martin et al. (Citation2022) used extracts from interviews with two transgender adolescents to form part of their intervention. The two transgender adolescents shared their lived experiences of the realities and barriers they experienced. Interviews were conducted with a cisgender coauthor. A transgender coauthor provided support to the adolescents during the interview process (Martin et al., Citation2022). Both coauthors identified their extensive experience with TGD healthcare (Martin et al., Citation2022). Authors of two further studies reported having clinical expertise working with TGD youth (Riggs, Citation2021; Vance et al., Citation2017). This self-identified expertise was noted when authors identified steps taken for intervention creation.

Primary outcome: impact of the intervention on TGD youths

Only one study exclusively reported on our primary outcome (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). The intervention aimed to provide support and information to TGD youth and their families and triage them to a secondary waitlist (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). TGD youths perceived significant positive changes in their lives following the intervention (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). This was attributed to increased knowledge of available supports and receiving appointments and referrals to gender clinics and support groups. Concerns about available supports also decreased from 60.6% (n = 83) pre-attendance to 40% (n = 54) post-attendance. Engagement with First Assessment Single-Session Triage (FASST) demonstrated improvements in depression, anxiety, and quality of life. When compared with the historical control group, the Parent-Rated Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in the prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety among those who engaged with FASST (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). Dahlgren Allen et al. (Citation2021) were unable to compare the Youth Self Report (YSR) outcomes with the historical group due to a lack of data within the historical group.

TGD youths identified increased comfort in furthering their social transition (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). Following FASST, there was an identifiable increase in TGD youths who had engaged in full social transition. Social transition, as a fixed variable, was demonstrated in a continuous outcome mixed effect linear model as having a positive statistically significant impact on all outcomes, unhealthy family functioning, depressive and anxiety symptoms in the CBCL, depressive problems in the YSR, and quality-of-life (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). TGD youths reported feeling an increased agency over their lives post-involvement in FASST resulting in experiences of influence, control, and ownership over their lives (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). One participant stated: “It’s definitely made me feel a lot more confident … I think it was a confirmation that what I was doing was the right choice for me, and ever since then, I’ve been confident in my transition” (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021, p. 7).

This intervention also facilitated an increase in willingness to use primary care services, and an increase in the use of menstrual suppression among participants who were assigned female at birth (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). Menstrual suppression, as a continuous outcome, demonstrated a positive statistically significant change in depressive symptoms, and anxiety, within the CBCL scale, and quality-of-life, within the Child Health Utility 9D scale, among TGD youths (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021).

Secondary outcome: impact of the intervention on healthcare providers

Eight studies assessed the impact of interventions on healthcare providers, which varied across studies. The following outcomes were measured: Knowledge of LGBT + and TGD healthcare needs (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2022; Riggs, Citation2021; Staggs et al., Citation2022; Vance et al., Citation2017; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019); beliefs and attitudes toward LGBT + and TGD individuals and provision of LGBT + and TGD healthcare (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2022; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019); confidence in provision of healthcare services to TGD individuals (Riggs, Citation2021; Staggs et al., Citation2022); and increasing affirming practices (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Sequeira et al., Citation2022).

Studies assessing knowledge outcomes included LGBT + education programs (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Staggs et al., Citation2022; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019) and TGD specific education programs (Martin et al., Citation2022; Riggs, Citation2021; Vance et al., Citation2017). Methods of delivery consisted of 1-h mandatory lectures with medical students (Wahlen et al., Citation2020), mandatory online training modules for pediatric staff (Staggs et al., Citation2022), a two-part education and cultural competence training course (Walia et al., Citation2019), and multistage educational programs, comprising 2-h of online content, 4-h of in-person content, and the provision of technical assistance for multiple hospital sites (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020).

A 1-h mandatory lecture targeting medical students was associated with a significant improvement in students’ knowledge of LGBT + adolescent healthcare (Mean(M): baseline = 73.7/100, post-intervention = 87.9/100; Wahlen et al., Citation2020). When isolating students with active religious practices, less favorable outcomes for knowledge were identified (M: baseline = 63.1/100, post = 73.2/100; Wahlen et al., Citation2020). Additionally, when Swiss students were compared with foreign students, there was a statistically significant difference in knowledge scores, with foreign students having lower scores (M: foreign students = 59.2/100, Swiss students = 73.1/100; Wahlen et al., Citation2020). The outcome for knowledge demonstrated a large change with an effect size of d = 0.84 (Wahlen et al., Citation2020). Staggs et al. (Citation2022) received positive feedback regarding their online training module, video, and tip sheet with 81% of pediatric staff strongly agreeing or agreeing that they had learned something new. Similarly, Jadwin-Cakmak et al. (Citation2020) identified positive outcomes related to increased knowledge of LGBT + healthcare needs. Knowledge items for participants significantly increased post-intervention (M: baseline: 7.22/12, post: 7.82/12; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Within in-depth interviews exploring the technical assistance aspect of their intervention, several sites engaged in modifications of language and practice reported staff had increased sense of awareness, and started making changes to intake forms and electronic systems to promote inclusivity (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). In contrast, following a two-part live LGBT + education and cultural competence session, Walia et al. (Citation2019) reported a non-statistically significant difference in participants’ knowledge (Language use: M: baseline = 4/5, post = 4/5; Assuming identity: M: baseline = 3/5, post = 4/5; Awareness of multiple minority status: M: baseline = 4/5, post = 4/5).

Within TGD specific education programs, methods of delivery included 90-min online sessions (Riggs, Citation2021), six online modules, supported by an in-person visit to a gender clinic (Vance et al., Citation2017), and in-person lectures inclusive of videos of TGD youths, provided by either a TGD woman or a cisgender woman (Martin et al., Citation2022).

Martin et al. (Citation2022) identified a positive change across all active intervention groups relating to the five knowledge-based questions. Of the five included questions, four demonstrated a statistically significant increase in knowledge post-intervention. The remaining knowledge-based question also showed a statistically significant increase in knowledge post-intervention. Similarly, Vance et al. (Citation2017) reported a positive change in all 20 transgender knowledge and awareness measures following engagement with a TGD youth curriculum. Additionally, within 13/20 outcome measures, median knowledge and awareness scores increased from, Likert score <3 to Likert score >3, which indicated an increase from not knowledgeable/aware to knowledgeable/aware (Vance et al., Citation2017). Awareness of the diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria within the Diagnostic Statistical Manual V increased from 84% (n = 46) to 100% (n = 55) following the intervention (Riggs, Citation2021). The open text responses requested participants to define cisgenderism, transgender, and non-binary. Before the educational intervention, 48 participants (87%) were unable to provide a definition of cisgenderism, however, following the webinar, 55 (100%) provided a valid definition of cisgenderism. Similarly, 32 (58%) participants provided a definition of transgender that was deemed as cisgenderist before the webinar series, while 40 (73%) provided an inclusive definition post-intervention. Following the webinar series, 55 participants (100%) were able to provide a sufficient definition of non-binary, in comparison to 40 participants (73%) before the intervention.

Outcomes assessing beliefs and attitudes were identified across four studies (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2022; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019). The educational content and the method of delivery varied across studies. Within three studies, LGBT + content was delivered to healthcare providers online and in-person (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Wahlen et al., Citation2020; Walia et al., Citation2019).

Following an LGBT + educational program, positive changes in attitude were observed (M: baseline = 3.40/4 6-month follow up = 3.61/4; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Participants were more willing to work with colleagues to create a safe space within their healthcare environment (M: baseline = 0.98/1, 6 months = 1.00/1; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Similarly, the belief that patients identify as their assigned sex changed significantly following the educational intervention (M: baseline = 3.26/5, 6 months = 2.27/5; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Through the assessment of attitudes, post an LGBT + education program, Wahlen et al. (Citation2020) identified a statistically significant difference in attitudes (M: baseline = 84.8/100; 6 month mean = 86.8/100). Of note, the effect size was d = 0.14 which demonstrates a negligible effect overall for belief outcomes (Wahlen et al., Citation2020). In addition, Wahlen et al. (Citation2020) compared medical students who had active religious practices and noted a less favorable outcome in beliefs (M: baseline = 75.3/100, post = 84.7/100) for this group. The assessment of the beliefs of participants following a two-part live education session relating to LGBT + cultural competence did not demonstrate any statistically significant difference (M: pre-intervention = 3/5; post-intervention = 4/5; Walia et al., Citation2019).

Martin et al. (Citation2022) assessed for changes in belief, using a temperature rating scale, a social tolerance subscale, an acceptance of gender spectrum subscale, and a comfort and contact subscale, following the provision of in-person TGD youth education. The temperature rating scale allowed for the exploration of the levels of warmth participants felt toward TGD individuals pre- and post-intervention. When all three active intervention arms were combined for the temperature scale all three points, friend, or social acquaintance, teacher or fellow student, and family member demonstrated a statistically significant difference. Of note, only the arm that had a transgender instructor demonstrated a statistically significant change in temperature toward a friend or social acquaintance, teacher or fellow student, and family member.

The social tolerance subscale demonstrated a statistically significant change when all three active intervention arms were combined. When assessed individually, no group demonstrated statistically significant change following their intervention on the social tolerance subscale (Martin et al., Citation2022). The comfort and contact subscale also demonstrated very limited significant differences following the intervention in individual groups (Martin et al., Citation2022). Acceptance of the gender spectrum subscale demonstrated the most significant difference in individual arms of the active intervention groups (Martin et al., Citation2022). The intervention arm which used TGD material, presented by a transgender person identified the greatest number of statistically significant differences (Martin et al., Citation2022).

Confidence in working with LGBT + and TGD individuals was an outcome also assessed in two of the included studies (Riggs, Citation2021; Staggs et al., Citation2022). Intervention content varied within these studies which included one study focused on TGD healthcare (Riggs, Citation2021), while the other focused on LGBT + healthcare (Staggs et al., Citation2022). Delivery was completed via online synchronous sessions and SOGI inclusivity training (Riggs, Citation2021; Staggs et al., Citation2022).

Following SOGI training, Staggs et al. (Citation2022) found that 85% (n = 11,090) of hospital employees strongly agreed or agreed that the online training module would inform their practice. Riggs (Citation2021) demonstrated a statistically significant increase (p = 0.02) in levels of confidence in working with TGD youths after a TGD webinar series (M = 22.11) as compared to before (M = 11.97). It was noted however that those who had undertaken TGD training before the webinar series reported greater confidence at baseline (M = 20.34) compared to those who had not (M = 10.15). In addition, providers who had previously worked with TGD youths also demonstrated greater confidence at baseline (M = 20.05) as compared to those who had not (M = 15.60). Finally, Riggs (Citation2021) identified a moderate strength positive correlation between the numbers of TGD youths a professional had worked with and their levels of reported confidence at baseline. As such, previous experience, and exposure to TGD clients impact the baseline level of confidence among professionals.

Finally, increased affirming TGD practices were noted across three studies (Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020; Sequeira et al., Citation2022; Staggs et al., Citation2022). Following the multistage education program there was no statistically significant difference and negligible effect size in healthcare providers’ use of preferred names (M: baseline = 4.72, 6 months = 4.76) and pronouns (M: baseline = 4.51, 6 months = 4.55; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., Citation2020). Sequeira et al. (Citation2022) utilized a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model to implement a three-cycle initiative within a pediatric emergency department. At baseline, adherence to documentation of preferred pronouns was 13.8%. Post cycle 1, this increased to 20.1% remaining static at this level post cycle 2 with the largest increase during cycle 3 with adherence at 47.8% (Sequeira et al., Citation2022). As part of cycle 3, a case study was circulated in which a TGD youth was misgendered for their entire stay during the PDSA cycle. Staggs et al. (Citation2022) identified limited significant differences in the use of pronouns and chosen names throughout the hospital campuses. Check-in, and medical assistant/nurse/technician interactions, within gender diversity clinics were the two areas demonstrating significant changes out of a potential 19 areas (Staggs et al., Citation2022).

Discussion

The aim of this mixed-methods systematic review was to identify and critically analyze the effect of interventions to improve the healthcare experiences of TGD youth. Interventions were predominantly education-based, in-person, targeted healthcare providers and assessed knowledge, beliefs, confidence, and understanding of transgender healthcare. TGD focused education interventions demonstrated more significant differences in outcomes when compared with LGBT + focused interventions. Interventions that included social contact with TGD individuals demonstrated more significant outcomes in both beliefs and knowledge.

Despite our primary outcome focusing on the impact of interventions on the experiences of TGD youth, only one study included TGD youths as their primary population (Dahlgren Allen et al., Citation2021). This lack of co-production is noted across the majority of included studies. Co-production in healthcare is defined as a collaborative partnership between healthcare providers and patients, involving sharing knowledge, and experience to improve the quality of care (Batalden et al., Citation2016). When applied to healthcare, research co-production aims to ensure that research priorities, methodologies, and outcomes are shaped by the perspectives and needs of all stakeholders (Hamilton et al., Citation2018; Saab et al., Citation2023). Vincent (Citation2018) provided guidelines for the ethical recruitment and involvement of the TGD community in academic research. Such guidelines provide a roadmap for researchers to increase capacity for co-production with the TGD community. Staples et al. (Citation2018) identified the reluctance of some members of the TGD community to engage with healthcare research, primarily due to fear of the potential misuse of findings. In addition, Portz and Burns (Citation2020) identified a lack of cultural competence among researchers resulting in TGD individuals not being involved in research design and evaluation. It is evident that the feeling of mistrust among TGD individuals and the lack of cultural competence among providers has the potential to undermine co-production efforts in healthcare research.

The content type of the intervention (i.e. TGD focused content or broader LGBT + content), affected the impact on outcome measures. TGD-focused content exhibited a more positive impact on knowledge, beliefs, and use of affirming practices outcomes in comparison to LGBT + content. Knowledge of healthcare needs of TGD youth increased in all studies that provided TGD specific education content however did not when LGBT + education was delivered. Health disparities are population-specific inequalities occurring in marginalized groups (Braveman, Citation2014). As such, it is important to acknowledge the distinct health disparities that exist between individual groups within the larger LGBT + community umbrella, particularly those who self-identify as TGD. Within the LGBT + youths’ community, Hafeez et al. (Citation2017) noted concerning issues including peer victimization, rejection from family, stigmatization, and social stress. Also identified was the insufficient LGBT + healthcare training of providers which has the potential to sustain bias and inequity, resulting in negative health outcomes. In comparison, Su et al. (Citation2016) noted that relative to their LGB counterparts, TGD individuals were more likely to experience instances of discrimination, depressive symptoms, and suicidality. This is supported by Kachen and Pharr (Citation2020) who identified that within the TGD population, disparities existed for transgender people which varied from gender-diverse people. Transgender individuals were more likely to have experienced discrimination in healthcare and to have postponed healthcare access due to fears of discrimination, whereas gender-diverse individuals delayed care due to cost. The acknowledgment of these unique experiences of members of the TGD population should influence the educational content chosen for healthcare professionals.

Stroumsa et al. (Citation2019) reported that the provision of TGD healthcare education alone may not be sufficient to improve competence. This is evidenced by the lack of increased knowledge, about TGD healthcare, following an education intervention, among healthcare students with active religious beliefs. Healthcare providers’ transphobic beliefs have the potential to negate the positive impacts of the educational intervention (Stroumsa et al., Citation2019). The Knowledge-Attitude-Behavior model posits that the acquisition of knowledge influences the development of preconceived attitudes, resulting in behaviors that correspond with a preconceived attitude (Allport, Citation1935). Additionally, the Mere-Exposure effect postulates that repeated exposure to stimulus biases will result in a change of attitudes toward that stimulus (Zajonc, Citation1968). In line with this, belief and attitude measures increased in interventions with TGD specific content, demonstrating its most significant positive change when TGD social contact was an element (Martin et al., Citation2022; Vance et al., Citation2017). Prior social contact with TGD youths was also identified as impacting healthcare providers level of confidence in working with TGD individuals (Riggs, Citation2021). As such, while knowledge can increase, its impact on underlying belief systems may not be affected. A meta-analysis of 79 stigma reduction studies noted that interventions containing an element of social contact with communities demonstrated twice the effect size in comparison with education only elements (Corrigan et al., Citation2012). In keeping with this model, Angermeyer and Matschinger (Citation1996) indicated that those with personal exposure to mental illness demonstrated a more positive attitude toward those with mental illness. This was further supported by Kaiser et al. (Citation2022) who identified social contact as a determinant of increased willingness to care for service users. Similarly, Tsujita et al. (Citation2023) noted a marked decrease in stigmatizing beliefs toward those with autism spectrum disorders following a simulated autistic perception and social contact. It can be inferred that interventions that contain TGD only content and allow contact with TGD individuals have a greater impact on providers beliefs and attitudes.

Limitations

Articles published only in the English language were included, meaning relevant materials may have been excluded. Studies that targeted healthcare providers were limited to providers working within pediatric settings or healthcare providers who received TGD-specific education intervention. This limits the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare services.

Only one study addressed the review’s primary outcome i.e. TGD youth as the primary population. As such, it is not possible to ascertain the direct effect of interventions targeting healthcare providers on TGD youths’ experiences of access to healthcare and care provision. The countries in which the studies were conducted would be considered high income countries and as such do not necessarily reflect the impact or experiences these interventions would have in lower income countries and in countries where TGD youths face discrimination and/or do not have access to healthcare services tailored to their needs.

Conclusion

Overall, this review has demonstrated that educational interventions aimed at improving the healthcare experiences of TGD youth are focused on enhancing the knowledge of healthcare providers. Such interventions are not TGD specific, as TGD youth were not involved in intervention co-production and the intervention impact on TGD youth was not assessed. TGD healthcare education is often being delivered under the umbrella of LGBT + education despite the TGD population experiencing unique sets of health disparities. Findings demonstrate implications for research and education. Future research should involve TGD youth in the co-creation and evaluation of interventions, while interventions should include TGD youth as their primary target population. Knowledge-based interventions targeting healthcare providers had a significant impact on knowledge of TGD healthcare. As such, education should be provided to both healthcare staff and students. Further exploration of the use of social contact with TGD individuals within interventions to improve healthcare provider knowledge is needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.1 KB)Acknowledgments

There are no further acknowledgments required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In A handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Clark University Press.

- Angermeyer, M. C., & Matschinger, H. (1996). The effect of personal experience with mental illness on the attitude towards individuals suffering from mental disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 31(6), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00783420

- Batalden, M., Batalden, P., Margolis, P., Seid, M., Armstrong, G., Opipari-Arrigan, L., & Hartung, H. (2016). Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(7), 509–517. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315

- Braveman, P. (2014). What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl 2), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291s203

- Call, D. C., Challa, M., & Telingator, C. J. (2021). Providing affirmative care to transgender and gender diverse youth: Disparities, interventions, and outcomes. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(6), 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01245-9

- Coleman, E., Radix, A. E., Bouman, W. P., Brown, G. R., de Vries, A. L. C., Deutsch, M. B., Ettner, R., Fraser, L., Goodman, M., Green, J., Hancock, A. B., Johnson, T. W., Karasic, D. H., Knudson, G. A., Leibowitz, S. F., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Monstrey, S. J., Motmans, J., Nahata, L., … Arcelus, J. (2022). Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(Suppl 1), S1–S259. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

- Dahlgren Allen, S., Tollit, M. A., McDougall, R., Eade, D., Hoq, M., & Pang, K. C. (2021). A waitlist intervention for transgender young people and psychosocial outcomes. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2020042762. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-042762

- Goulding, R., Goodwin, J., O’Donovan, A., & Saab, M. M. (2023). Transgender and gender diverse youths’ experiences of healthcare: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Journal of Child Health Care, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935231222054

- Hafeez, H.,Zeshan, M.,Tahir, M. A.,Jahan, N., &Naveed, S. (2017). Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: A literature review. Cureus, 9(4), e1184. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1184

- Hamilton, C. B., Hoens, A. M., Backman, C. L., McKinnon, A. M., McQuitty, S., English, K., & Li, L. C. (2018). An empirically based conceptual framework for fostering meaningful patient engagement in research. Health Expectations, 21(1), 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12635

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Hunt, Q. A., Morrow, Q. J., & McGuire, J. K. (2020). Experiences of suicide in transgender youth: A qualitative, community-based study. Archives of Suicide Research, 24(sup2), S340–S355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1610677

- Hunter, K. E., Webster, A. C., Page, M. J., Willson, M., McDonald, S., Berber, S., Skeers, P., Tan-Koay, A. G., Parkhill, A., & Seidler, A. L. (2022). Searching clinical trials registers: Guide for systematic reviewers. BMJ, 377, e068791. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068791

- Jadwin-Cakmak, L., Bauermeister, J. A., Cutler, J. M., Loveluck, J., Kazaleh Sirdenis, T., Fessler, K. B., Popoff, E. E., Benton, A., Pomerantz, N. F., Gotts Atkins, S. L., Springer, T., & Harper, G. W. (2020). The Health Access Initiative: A training and technical assistance program to improve health care for sexual and gender minority youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(1), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.013

- Johns, M. M., Gordon, A. R., Andrzejewski, J., Harper, C. R., Michaels, S., Hansen, C., Fordyce, E., & Dunville, R. (2023). Differences in health care experiences among transgender and gender diverse youth by gender identity and race/ethnicity. Prevention Science, 24(6), 1128–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01521-5

- Kachen, A., & Pharr, J. R. (2020). Health care access and utilization by transgender populations: A United States transgender survey study. Transgender Health, 5(3), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0017

- Kaiser, B. N., Gurung, D., Rai, S., Bhardwaj, A., Dhakal, M., Cafaro, C. L., Sikkema, K. J., Lund, C., Patel, V., Jordans, M. J. D., Luitel, N. P., & Kohrt, B. A. (2022). Mechanisms of action for stigma reduction among primary care providers following social contact with service users and aspirational figures in Nepal: An explanatory qualitative design. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00546-7

- Martin, A., Celentano, J., Olezeski, C., Halloran, J., Penque, B., Aguilar, J., & Amsalem, D. (2022). Collaborating with transgender youth to educate healthcare trainees and professionals: Randomized controlled trial of a didactic enhanced by brief videos. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2427. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14791-5

- McGuinness, L. A., &Higgins, J. P. T. (2021). Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1411 32336025

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Portz, K. J., & Burns, A. (2020). Utilizing mixed methodology to increase cultural competency in research with transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Transgender Health, 5(1), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0057

- Rajkovic, A., Cirino, A. L., Berro, T., Koeller, D. R., & Zayhowski, K. (2022). Transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals’ perspectives on research seeking genetic variants associated with TGD identities: A qualitative study. Journal of Community Genetics, 13(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-021-00554-z

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), 12–13.

- Riggs, D. W. (2021). Evaluating outcomes from an Australian webinar series on affirming approaches to working with trans and non-binary young people. Australian Psychologist, 56(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1902747

- Saab, M. M., Shetty, V. N., McCarthy, M., Davoren, M. P., Flynn, A., Kirby, A., Robertson, S., Shorter, G. W., Murphy, D., Rovito, M. J., Shiely, F., & Hegarty, J. (2023). Promoting ‘testicular awareness’: Co-design of an inclusive campaign using the World Café Methodology. Health Expectations, 27(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13898

- Sequeira, G. M., Kidd, K. M., Thornburgh, C., Ley, A., Sciulli, D., Clapp, M., Pitetti, R., Matheo, L., Womeldorff, H., Christakis, D. A., & Zuckerbraun, N. S. (2022). Increasing frequency of affirmed name and pronoun documentation in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Hospital Pediatrics, 12(11), 995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2022-006818

- Staggs, S., Sewell, R., Buchanan, C., Claussen, L., Franklin, R., Levett, L., Poppy, D. C., Porto, A., Reirden, D. H., Simon, A., Whiteside, S., & Nokoff, N. J. (2022). Instituting sexual orientation and gender identity training and documentation to increase inclusivity at a pediatric health system. Transgender Health, 7(5), 461–467. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0016

- Staples, J. M., Bird, E. R., Masters, T. N., & George, W. H. (2018). Considerations for culturally sensitive research with transgender adults: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 55(8), 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1292419

- Stern, C., Lizarondo, L., Carrier, J., Godfrey, C., Rieger, K., Salmond, S., Apostolo, J., Kirkpatrick, P., & Loveday, H. (2021). Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(2), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000282

- Sterne, J. A. C., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A. W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H.-Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., McAleenan, A., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Stroumsa, D., Shires, D. A., Richardson, C. R., Jaffee, K. D., & Woodford, M. R. (2019). Transphobia rather than education predicts provider knowledge of transgender health care. Medical Education, 53(4), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13796

- Su, D., Irwin, J. A., Fisher, C., Ramos, A., Kelley, M., Mendoza, D. A. R., & Coleman, J. D. (2016). Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0001

- Sweileh, W. M. (2018). Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature in transgender health (1900–2017). BMC International Health Human Rights, 18(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0155-5

- Sweileh, W. M. (2022). Research publications on the mental health of transgender people: A bibliometric analysis using Scopus database (1992–2021). Transgender Health. [Online Ahead of Print] https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2022.0006

- Tsujita, M., Homma, M., Kumagaya, S. I., & Nagai, Y. (2023). Comprehensive intervention for reducing stigma of autism spectrum disorders: Incorporating the experience of simulated autistic perception and social contact. PLOS One, 18(8), e0288586. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288586

- Vance, S. R.Jr., Deutsch, M. B., Rosenthal, S. M., & Buckelew, S. M. (2017). Enhancing pediatric trainees’ and students’ knowledge in providing care to transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(4), 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.020

- Veritas Health Innovation (2023). Covidence systematic review software, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from www.covidence.org

- Vincent, B. W. (2018). Studying trans: Recommendations for ethical recruitment and collaboration with transgender participants in academic research. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1434558

- Wahlen, R., Bize, R., Wang, J., Merglen, A., & Ambresin, A.-E. (2020). Medical students’ knowledge of and attitudes towards LGBT people and their health care needs: Impact of a lecture on LGBT health. PLOS One, 15(7), e0234743. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234743

- Walia, H., Banoub, R., Cambier, G. S., Rice, J., Tumin, D., Tobias, J. D., & Raman, V. T. (2019). Perioperative provider and staff competency in providing culturally competent LGBTQ healthcare in pediatric setting. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 10, 1097–1102. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.S220578

- Wittlin, N. M., Kuper, L. E., & Olson, K. R. (2023). Mental health of transgender and gender diverse youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072220-020326

- Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2, Pt.2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848