Abstract

The aim of this study is to explore the current scientific evidence for using the twelve-step method as a treatment method for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder). Peer-reviewed empirical articles on the twelve-step method and sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder) written in English, Danish, Norwegian, or Swedish, retrievable in selected databases were included. No limits were set on publication date or study design. The systematic review resulted in eight empirical studies which were read and assessed according to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. The results were inconclusive, and we found only three articles of high quality, where the samples were composed mainly by men, which indicate that peer-therapy in combination with individual therapy might be beneficial. That twelve-step treatment rests heavily on the idea of sex addiction was unproblematized in most of the publications. Overall, the findings raise issues concerning who benefits from this treatment.

Background

Self-help organizations such as Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) and Sex and Love Addictions Anonymous, (SLAA), offering twelve-step treatment for what it termed sex and/or love addiction, exist in approximately 42 countries and have about 16,000 members (SLAA Tampa Bay, Citation2024). In North America, Sexaholics Anonymous (SA) offer information of their twelve-step treatment in 22 different languages (SA, Citation2024), Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA) offer digital twelve-step meetings in different states of the US and in Berlin, Germany (SCA, Citation2024), and Sexual Recovery Anonymous (SRA) provides twelve-step meetings across the US, in the UK and in Mexico (SRA, Citation2024). In Sweden, SLAA and SAA operate in approximately twenty cities as well as online, and support groups can be found in the capital (SLAA, Citation2023; SAA, Citation2023). Across the country there are also coaches, clinics and institutions offering individual or group therapy, based on twelve-step ideas (e.g. Dysberoendekliniken, Citation2024). In 2020, a motion was put forward in the Swedish Parliament to formally classify sex and love addiction as an addiction diagnosis, and to make treatment publicly available (Swedish Parliament, Citation2023). Sex addiction and its treatment is thus a topical issue for sexology and sexuality research, both in the local Swedish context and globally. In this study we have conducted a systematic review of existing empirical research of twelve-step treatment. We examine the scientific support for using twelve-step treatment for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder), as both these concepts are used. We will describe the central concepts for this study – sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder) and twelve-step treatment – before we formulate our aim and describe the systematic literature review and our results.

Sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder)

Although the concept of sex addiction is used in various societal contexts (among politicians, professionals, researchers, and among self-diagnosed individuals), an established diagnose that address sex addiction is lacking in the classification and diagnostic instruments International statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems, (ICD), and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders, (DSM), that are globally used. Similar diagnoses, such as hypersexual disorder, HD, figure in the medical literature, but did not enter the latest version of DSM-5 (APA, Citation2013). In the newest version of ICD-11, a concept similar to sex addiction was added: compulsive sexual behavior disorder, (CSBD). In some studies researchers also refer to compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) when there is no clear diagnosis of disorder. However, CSBD emphasizes compulsivity in relation to sexuality, not addiction (WHO, Citation2020). Some researchers argue that sexual addiction disorder has been largely ignored by clinicians, and that increased attention is beneficial (Sahithya & Kashyap, Citation2022). There are no clear figures on how many people are having a compulsivity in relation to sexuality, or are identifying as sex addicts, but an American survey (N = 2325) found that 10.3% of men and 7.0% of women reported general distress over compulsive, excessive, or seemingly out-of-control sexual behaviors (Dickenson, Gleason, Coleman, & Miner, Citation2018). A more recent estimation, with data from 42 countries, is that close to 5% of the population are at risk of CSBD, though estimates varied between 1.6% to 16.7% across countries and genders (men had the highest scores, followed by gender-diverse individuals, and women), but not sexual orientations (Bőthe et al., Citation2023).

Overall, previous research on sex addiction is fragmented and lacks consensus. In an extensive review of 415 studies, it was found that research related to compulsive sexual behaviors has increased and proliferated (Grubbs et al., Citation2020). However, according to the authors, much of this work was characterized by simplistic methodological designs, a lack of theoretical integration, and an absence of quality measurement. Moreover, the authors found an absence of high-quality treatment-related research. The dominating description has been that sex addiction is a disease that can be cured (Rosenberg, O’Connor & Carnes, Citation2014; Carnes Citation2001). This description has however been contested and criticized as an expression of moralism and sex negativity (Dodge et al., Citation2004; Neves, Citation2021; Reay, Attwood & Gooder, Citation2013). Depending on view, different forms of treatment is suggested (van Tuijl et al., Citation2020), and assessment instruments developed (Miele et al., Citation2023). Those who advocate compulsive sexuality as a disease and addiction generally suggest 12-step treatment while critics argue that this method is ineffective and can lead to a worsened situation for individuals undergoing it (Neves, Citation2021).

Twelve-step treatment

Twelve-step treatment is offered in several different forms, primarily through self-help organizations such as SLAA, SAA, SA, SCA and SRA who operate on a global scale. The groups are arranged according to the same principles as Alcoholics Anonymous’ twelve-step groups where structure and community are central aspects. Part of the twelve-step treatment is a sponsorship where a more experienced member guides and helps a newer member through the twelve steps. According to the method, sex addiction is a chronic disease in which the individual no longer has control over their life but can learn to master their addiction through the twelve steps. According to the Sex Addicts Anonymous book (Citation2005), a methods book or manual, the goal with the twelve-step treatment is sexual sobriety. The book provides instructions on the twelve steps and includes life stories of people with different types of sex addiction who have been helped by the treatment. The method has a pronounced religious and spiritual foundation and comprises several elements, for example believing in a higher power, admitting ones’ wrongdoings, asking for forgiveness, gaining strength through prayers, and ultimately using the spiritual awakening to help others (Parker & Guest, Citation1999; Tangenberg, Citation2005). Scientific support for the twelve-step method for love addiction (a concept or condition similar to sex addiction) is also lacking, despite the methods’ popularity (Sanches & John, Citation2019). Considering the well-established twelve-step treatment that is offered globally for sex (and love) addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder), for some individuals being the only treatment geographically or financially available to them, research on its effectiveness is needed.

Aim

The aim of this study is to explore the current scientific evidence for using the twelve-step method as a treatment method for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder). Our research questions are:

What is the current scientific support for considering twelve-step method an effective treatment for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder)?

What other results in the studies are important to consider when assessing the relevance of twelve-step method for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder)?

Methods

Data collection

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses, (PRISMA), statement (Moher et al., Citation2009). Peer-reviewed empirical articles on the twelve-step method (alternative phrases used were twelve step, twelve-step, 12 step, and 12-step) and sex addiction (alternative phrases used were sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive sexual disorder, hypersexuality, hypersexual disorder, sexaholics), written in English, Danish, Norwegian, or Swedish, retrievable in selected databases until 4th of April, 2023 were included. No limits were set on publication date or study design.

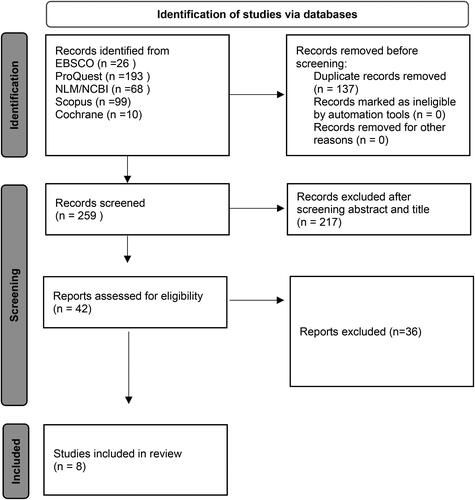

After consulting an information specialist at Malmö university library the following data bases were used: NLM/NCBI (PubMed), ProQuest (PsycInfo, Sociological abstracts and social services abstracts), EBSCO (Cinahl), Scopus, Cochrane, SVEPUB (Swedish publications), Cristin (Norwegian publications) and Forskningsdatabasen (Danish publications). The core database search strategy relied on free text search using the following string (“Sex addiction” OR “Sexual addiction” OR “Sexual compulsivity” OR “Compulsive sexual behavior” OR “Compulsive sexual disorder” OR “Hypersexuality” OR “Hypersexual disorder” OR “Sexaholics”) AND (“Twelve step” OR “Twelve-step” OR “12-step” OR “12 step”). The national Swedish, Norwegian and Danish databases generated no search hits, and NLM/NCBI, ProQuest and EBSCO, Scopus, and Cochrane generated 259 abstracts (duplicates removed). The 259 abstracts were read and rated on three levels (inclusion, exclusion or maybe) by all authors separately, using Rayyan (Ouzzani, et al., Citation2016). In a consensus meeting, 42 publications were selected for full-text reading. Full-text reading was also performed separately by all authors, and the publications were again rated, now for inclusion or exclusion, again using Rayyan. In a final consensus meeting, eight publications were included in the review. See for a flow chart describing the process.

Quality appraisal of included studies

The eight empirical studies were read and assessed according to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, (MMAT), a critical appraisal tool used for the appraisal stage in a systematic mixed studies review (Hong et al., Citation2018). The MMAT assessments were performed individually by the four authors, and disagreements were solved in consensus meetings. The MMAT assessment identified four quantitative non-randomized studies, two assessed of high quality (Efrati & Gola, Citation2018 and Wnuk & Charzyńska, Citation2022) and two assessed of medium quality (Merghati Khoei et al., Citation2021 and Wright, Citation2010), one quantitative descriptive study assessed of low quality (Schneider & Schnedier, 1996) and three studies using qualitative methods, one assessed of high quality (Fernandes, Kuss & Griffiths, 2021) and two assessed of low quality (Saulnier, Citation1996 and Yamamoto, Citation2020). For an overview of the MMAT quality appraisal of the studies, see .

Table 1. Study quality assessment according to the mixed methods appraisal tool, MMAT.

Data analysis

The identified studies varied substantially regarding participants characteristics and study contexts, aims, outcomes measures and main results. Therefore, standard summary measures for intervention outcomes were deemed inapplicable, and data were synthesized across studies and the findings are presented narratively (Popay et al. Citation2006).

Results

The findings of the narrative analysis are presented in the following three themes: (i) Participants characteristics and study contexts, (ii) Study aims, and (iii) Outcome measures and Main results. An overview of included studies is presented in .

Table 2. Detailed description of studies included in the systematic review of twelve-step treatments for people who identify as, or are identified as, having a sex addiction.

Participants characteristics and study contexts

As can be seen in , the number of participants vary between studies: between 4 and 14 in the studies with a qualitative design, and between 80 and 163 in the studies using quantitative design. A total of 611 persons were included in the eight studies, and a vast majority, ranging between 77% and 100% of participants were men. One study (Saulnier, Citation1996) included women only (n 14). Participants’ age is reported within the range 18 to 71 years, and mean age reported varies between 30.19 years (Efrati & Gola, Citation2018) and 50.96 (Wright, Citation2010). Three studies recruited participants in USA and Canada (Saulnier, Citation1996; Schneider & Schneider, Citation1996; and Wright, Citation2010), one in the United Kingdom (Yamamoto, Citation2020), one in Poland (Wnuk & Charzyńska, Citation2022), one in Israel (Efrati & Gola, Citation2018), and one in Iran (Mergati Khoei et al., 2021). One publication (Fernandez, Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2021) recruited participants (n 14) from eight different countries across the world. Two of the eight publications are from the 1990ies, and one from the 2010s, and these three older studies are the ones conducted in north America. Five studies were from the 2020ies.

Study aims

The four quantitative non-randomized studies all examined different aspects of twelve-step treatment. Efrati and Gola (Citation2018) examined relationships between advancement in the recovery process in SA groups and severity of compulsive sexual behavior, (CSB), sexual-related sense of helplessness, treatment-seeking behavior, self-control, social support, sexual suppression, mental health, and sociodemographic measures. Wnuk & Charzyńska (Citation2022) hypothesized and examined a direct positive relationship between SA involvement and life satisfaction. Mergati Khoei and colleagues (2021) hypothesized that community support (i.e. regular attendance in SA meetings, regular phone calls to other members, supporting other members as a sponsor or receiving support) may be associated with different coping styles (emotion-oriented, task-oriented, and avoidance styles). Wright (Citation2010) examined associations between attendance at 12-step meetings, involvement with 12-step sponsors, and levels of sexual compulsivity. The one study with a quantitative descriptive design explored the types of problems couples and individuals experience during recovery from sexual addiction and ways they resolved them (Schneider & Schneider, Citation1996).

The three studies using qualitative methods also had varying study aims. Fernandez, Kuss and Griffiths (Citation2021) performed an analysis of phenomenological experiences of recovery from compulsive sex behavior among members of SLAA groups. Saulnier (Citation1996) explored how twelve-step programs are perceived by African American women members, and Yamamoto (Citation2020) examined the effectiveness of a combined intervention (regular involvement with a twelve-step program and weekly individual psychotherapy).

Outcome measures and Main results

In all four quantitative non-randomized studies, different questionnaires were administered, either in person or on-line. Efrati and Gola (Citation2018) used six scales (internal consistency reported as adequate) and found that advancement in an SA program was significantly related to lower levels of sexual-related overall sense of helplessness, avoidant help-seeking, self-control, overall CSB, sexual suppression and higher well-being. Mergati Khoei and colleagues (2021) used a single 48-item questionnaire (internal consistency reported as adequate) administered in an in-person meeting and showed a significant association between different coping styles and elements of community support in SA groups. Wnuk and Charzyńska (Citation2022) used six various scales (internal consistency reported as adequate) to measure SA group involvement, severity of the CSBD, meaning in life, hope, satisfaction with life, and subjective religiosity and found a direct positive relationship between SA involvement and life satisfaction, a relationship that was mediated by the presence of meaning in life and hope. Wright (Citation2010) used three different scales (internal consistency reported as adequate) to measure sexual compulsivity meeting attendance and sponsor work and concluded that higher levels of meeting attendance and sponsor work at an earlier period in participants’ lives were associated with lower levels of sexual compulsivity at a later period in their lives. However, meeting attendance and sponsor work did not explain interindividual change in sexual compulsivity over time.

In the one study having a descriptive quantitative design, Schneider and Schneider (Citation1996), distributed a 14-page anonymous on-line survey consisting of open-ended questions and forced choices measured on a Likert scale (internal consistency not reported) and found that among those with a high level of trust, most had a long-term commitment to a twelve-step program. When asked “What are you and your partner doing to rebuild trust in your relationship?” respondents reported, among other things, that going regularly to twelve-step meetings was a trust building activity.

The three studies with a qualitative design, all used individual interviews as data gathering method, and one also used group discussions and a case study (Saulnier, Citation1996), but the three studies applied different analytic methods. Fernandez, Kuss and Griffiths (Citation2021) applied a thematic analysis and found five themes (i) unmanageability of life as impetus for change, (ii) addiction as a symptom of a deeper problem, (iii) recovery is more than just abstinence, (iv) maintaining a new lifestyle and ongoing work on the self, and (v) the gifts of recovery) that captured twelve-step group members experiences of recovery from their compulsive sexual behavior. Saulnier (Citation1996) used a non-specified method to analyze recordings from individual interviews, group discussions, and a case study, and concluded that the African American female participants were sometimes critical of twelve-step programs (they experienced the programs as white, in terms of both membership and culture, and felt a lack of understanding during the meetings). Despite this, on many occasions, participants were also supportive of the twelve-step model, and felt it offered them something useful (Saulnier, Citation1996). Yamamoto (Citation2020) analyzed semi-structured interviews using an interpretative phenomenological analysis, and the main finding presented was the complementary benefit of twelve-step meeting attendance, active involvement with a sponsor, and individual psychotherapy.

Discussion

Inconclusive support

Initially we asked: What is the current scientific support for considering twelve-step method an effective treatment for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder)? The findings in this systematic review of eight empirical studies are inconclusive. Only two quantitative and one qualitative study was found to be of high quality and while the results of these studies are positive regarding the helpfulness of twelve-step treatment (peer-therapy in combination with individual therapy might be beneficial), the overall scientific support is very weak. As another example of the lacking scientific support, three different types of study designs (quantitative non-randomized, quantitative descriptive and qualitative) were found but no randomized control study or any other study with a design allowing for a control group. Our findings are in line with a systematic and methodological review of 25 years of research related to compulsive sexual behaviors: much of the work found was characterized by simplistic methodological designs, a lack of theoretical integration, an absence of quality measurement and of high-quality treatment-related research (Grubbs et al., Citation2020). The different designs, participants characteristics, study contexts, aims, outcomes measures and main results found in the present review also hindered a fruitful comparison between studies. Additionally, most studies found were based on small numbers of participants. Considering that no time limit for publications was set in the search phase of the review, we consider the total number of participants in the evaluated studies (N = 611), over a period of close to 30 years, to be surprisingly low. In line with previous findings in reviews regarding treatment of CBSD (Griffin, Way & Kraus, Citation2021), the participants in the reviewed studies are mainly white heterosexual men. This severely limits our understanding of how twelve-step treatment might work for individuals with other genders, ethnicities and sexual orientations.

Aspects to consider

The second question we asked was: what other results in the studies are important to consider when assessing the relevance of twelve-step method for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder)? One important aspect was how the different studies treated central concepts. The three studies assessed as high quality all used the concept of compulsive sexual behavior (disorder) to measure the outcome of the treatment. However, in these studies, there is a general lack of problematization of measuring CSBD in a treatment method that is focused on addiction. As previously mentioned, sex addiction is not an established diagnosis. Perhaps connected to this, it is labeled differently across contexts (and indeed in the studies found), and it is a phenomenon that is controversial within both medicine and the field of sexology. In a meta-analysis of treatments for internet addiction, sex addiction and compulsive buying, twelve-step treatment studies were not included, and findings indicate that psychological, pharmacological and combined treatments for sex addiction is associated with robust pre-post improvements in the severity of sex addiction (Goslar et al., Citation2020). As examples of psychological treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy – either delivered in in-person group meetings (Hallberg et al., Citation2019) or on-line (Hallberg et al., Citation2020) appears to alleviate compulsiveness for men diagnosed with hypersexual disorder. There are limitations in the literature on pharmacology for the management of CSBD, as most evidence comes from case studies (Mestre‑Bach & Potenza, Citation2024)

The concurrent global access (the eight studies found do represent different parts of the world) to twelve-step treatment for people experiencing their sexuality as problematic can be seen as an example of how institutions offering support, care and treatment are continuously being faced with new and popularized concepts and self-diagnoses that are lacking in scientific support. These new concepts or self-diagnoses apparently speak to issues and experiences that people feel need to be articulated. It has been described that when sexual issues become medicalized outside of scientifically based care practices, this can result in a fast-growing market not only for treatment, but also a moralization of sexual practices (Reay, Attwood & Gooder, Citation2013). The findings can be translated into an important clinical implication: that these self-help groups exist and appear to thrive can be interpreted as a signal to established institutions and care givers of that peer groups meet needs that health care cannot. Indeed, individuals experiencing sex addiction or compulsivity related to their sexuality risk encountering professionals who lack not only basic skills within sexual and reproductive health and rights (Areskoug-Josefsson et al., Citation2019), but relatedly also the competence to respectfully deal with sexuality that is perceived to be non-normative or out of control. The seclusion provided by the twelve-step peer group can be experienced as protective. Additionally, this seclusion can be related to the low number studies found in the review, researchers may have had difficulties gaining access to the settings.

As sexuality researchers, we have come across participants who say they have a sex addiction, and as university teachers in the field of sexology we strive for providing students with accurate information regarding relevant treatment options related to different sexual problems. In relation to the latter, the review shows that current evidence, or support for the twelve-step treatment is inconclusive, and that most studies measure improvement in relation to compulsiveness, not addiction. Hence, there is low scientific support for treating sexual and intimate practices as issues of addiction today (Hesse, Citation2024), which makes it important to continue to investigate what is sometimes the only treatment offered or available for people with problems perceived as sex addiction or compulsive sexual behavior (disorder). Further studies should include explorations of how being part of twelve-step treatment and being labeled sex addicts affects people in various and intersecting positions related to, for instance, age, gender, sexual orientation, race, class, disability or religion.

Study strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review of twelve-step treatment for people who identify as, or are identified as, having a sex addiction or compulsive sexual behavior (disorder). Still, it has several limitations. Although using a thorough search strategy, we may have overlooked studies, especially ones in other languages than English, Norwegian, Danish or Swedish. Additionally, a limitation that could have affected the search is the ambiguity surrounding the phrases sex addiction (e.g. CSBD or CSB) and twelve-step treatment (e.g. SLAA, SAA, SA, SCA, SRA or S groups). To overcome this, the search included as many phrases as possible. The stepwise process with a combination of individual, paired and group (all four authors) assessment during the inclusion and assessment process is seen a strength of the study.

Conclusion

Considering the well-established twelve-step treatment that is globally offered, it is surprising how few studies that have been conducted so far. The findings in this systematic review of eight empirical studies were based on small numbers of participants, and most participants were men. No randomized control study was found. Additionally, a problematization of using a method developed for addiction in matters related to compulsiveness is lacking. The current scientific support for considering twelve-step method an effective treatment for sex addiction and compulsive sexual behavior (disorder) is thus weak.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- APA (2013). American psychiatric association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American psychiatric association.

- Areskoug-Josefsson, K., Schindele, A. C. C., Deogan, C., & Lindroth, M. (2019). Education for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR): A mapping of the SRHR-related content in higher education in health care, police, law and social work in Sweden. Sex Education, 19(6), 720–729. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1572501

- Bőthe, B., Koós, M., Nagy, L., Kraus, S. W., Demetrovics, Z., Potenza, M. N, … Sungkyunkwan University’s research team (2023). Compulsive sexual behavior disorder in 42 countries: Insights from the International Sex Survey and introduction of standardized assessment tools. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(2), 393–407. doi:10.1556/2006.2023.00028

- Carnes, P. (2001). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction. Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing.

- Dickenson, J. A., Gleason, N., Coleman, E., & Miner, M. H. (2018). Prevalence of distress associated with difficulty controlling sexual urges, feelings, and behaviors in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184468–e184468. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4468

- Dodge, B., Reece, M., Cole, S. L., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2004). Sexual compulsivity among heterosexual college students. Journal of Sex Research, 41(4), 343–350. doi:10.1080/00224490409552241

- Dysberoendekliniken (2024). Retrived from https://www.dysberoende.se/.

- *Efrati, Y., & Gola, M. (2018). Compulsive sexual behavior: A twelve-step therapeutic approach. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 445–453. doi:10.1556/2006.7.2018.26

- *Fernandez, D. P., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Lived experiences of recovery from Compulsive Sexual Behavior among members of Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous: A qualitative thematic analysis. Sexual Health & Compulsivity, 28(1–2), 47–80. doi:10.1080/26929953.2021.1997842

- Goslar, M., Leibetseder, M., Muench, H. M., Hofmann, S. G., & Laireiter, A. R. (2020). Treatments for internet addiction, sex addiction and compulsive buying: A meta analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(1), 14–43. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00005

- Griffin, K. R., Way, B. M., & Kraus, S. W. (2021). Controversies and clinical recommendations for the treatment of compulsive sexual behavior disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 8(4), 546–555. doi:10.1007/s40429-021-00393-5

- Grubbs, J. B., Hoagland, K. C., Lee, B. N., Grant, J. T., Davison, P., Reid, R. C., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Sexual addiction 25 years on: A systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101925. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101925

- Hallberg, J., Kaldo, V., Arver, S., Dhejne, C., Piwowar, M., Jokinen, J., & Öberg, K. G. (2020). Internet-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersexual disorder, with or without paraphilia(s) or paraphilic disorder(s) in men: A pilot study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(10), 2039–2054. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.07.018

- Hallberg, J., Kaldo, V., Arver, S., Dhejne, C., Jokinen, J., & Öberg, K. G. (2019). A randomized controlled study of group-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersexual disorder in men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(5), 733–745. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.005

- Hesse, M. (2024). Why compulsive sexual behavior is not a form of addiction like drug addiction. Sexual Medicine, 12(1), qfae006. doi:10.1093/sexmed/qfae006

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., … Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34 (4), 285–291. doi:10.3233/EFI-180221

- *Merghati Khoei, E., Mirzakhani, F., Yousefi, H., & Hoseinzadeh, M. (2021). The relationship between stress coping styles and community support among Iranian members of Sexaholics Anonymous twelve-step program. Sexual Health & Compulsivity, 28(3–4), 171–188. doi:10.1080/26929953.2021.2007191

- Mestre‑Bach, G., & Potenza, M. N. (2024). Current understanding of compulsive sexual behavior disorder and co‑occurring conditions: What clinicians should know about pharmacological options. CNS Drugs, 38(4), 255–265. doi:10.1007/s40263-024-01075-2

- Miele, C., Cabé, J., Cabé, N., Bertsch, I., Brousse, G., Pereira, B., … Barrault, S. (2023). Measuring craving: A systematic review and mapping of assessment instruments. What about sexual craving? Addiction (Abingdon, England), 118(12), 2277–2314. doi:10.1111/add.16287

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G, The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Neves, S. (2021). Compulsive Sexual Behaviours. A psycho-sexual treatment guide for clinicians. New York: Routledge.

- Parker., & Guest, DL. (1999). The clinician’s guide to 12-step programs: How, when, and why to refer a client. Westport: Auburn House.

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., … Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1(1), b92.

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Reay, B., Attwood, N., & Gooder, C. (2013). Inventing sex: The short history of sex addiction. Sexuality & Culture, 17(1), 1–19. doi:10.1007/s12119-012-9136-3

- Rosenberg, K P., O’Connor, S., & Carnes, P. (2014). Sex addiction: An overview. In Behavioral Addictions (pp. 215–236). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

- Sanches, M., & John, V. P. (2019). Treatment of love addiction: Current status and perspectives. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 33(1), 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.ejpsy.2018.07.002

- SA (2024). Sexaholics anonymous. Retrieved from https://www.sa.org/

- SAA. (2023). SAA – Sex Addicts Anonomoys. Retrieved from http://saasverige.se/ [In Swedish: SAA – Anonyma sexmissbrukare].

- SCA (2024). Sexual Compulsives Anonymous. Retrieved from https://sca-recovery.org/WP/fellowships/

- SLAA. (2023). SLAA– Sex and Love Addicts Anonomoys. Retrieved from www.slaa.se/ [In Swedish: SLAA – Anonyma sex- och kärleksberoende].

- SLAA Tampa Bay (2024). Retrieved from https://tampabayslaa.org/for-mental-health-professionals/

- SRA (2024). Sexual recovery anonymous. Retrieved from https://sexualrecovery.org/find-a-meeting-2/

- Sahithya, B. R., & Kashyap, R. S. (2022). Sexual Addiction Disorder – A review with recent updates. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 4(2), 95–101. doi:10.1177/26318318221081080

- *Saulnier, C. F. (1996). Images of the twelve-step model, and sex and love addiction in an alcohol intervention group for black women. Journal of Drug Issues, 26(1), 95–123. doi:10.1177/002204269602600107

- *Schneider, J. P., & Schneider, B. H. (1996). Couple recovery from sexual addiction/coaddiction: Results of a Survey of 88 Marriages. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 3 (2), 111–126. doi:10.1080/10720169608400106

- Sex Addicts Anonymous book (2005). International Service Organizations of SAA.

- Swedish Parliament. (2023). Retrieved from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokumentlagar/dokument/motion/klassa-sex–och-karleksberoende-som_H802203

- Tangenberg, M. K. (2005). Twelve-step programs and faith-based recovery. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 2(1–2), 19–40. doi:10.1300/J394v02n01_02

- van Tuijl, P., Tamminga, A., Meerkerk, G. J., Verboon, P., Leontjevas, R., & Lankveld, J. (2020). Three diagnoses for problematic hypersexuality; Which criteria predict help-seeking behavior? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6907. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186907

- WHO (2020). World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. Retrived from https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/

- *Wnuk, M., & Charzyńska, E. (2022). Involvement in Sexaholics Anonymous and life satisfaction: The mediating role of meaning in life and hope. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11 (2), 544–556. doi:10.1556/2006.2022.00024

- *Wright, P. (2010). Sexual compulsivity and 12-step peer and sponsor supportive communication: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(2), 154–169. doi:10.1080/10720161003796123

- *Yamamoto, M. (2020). Recovery from Hypersexual Disorder (HD): An examination of the effectiveness of combination treatment. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 27(3–4), 211–235. doi:10.1080/10720162.2020.1815267