ABSTRACT

The study was conducted in Bishoftu and Asella areas, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. This study aimed to identify the coping strategies utilized by smallholder dairy farmers in dealing with shocks and stresses encountered in dairy farming. Data were collected from September 2017 to April 2018, involving individual interviews with 120 households (60 per area), field observations, and focus group discussions. Dairy farmers were categorized into two groups (typical smallholders and entrepreneurial farmers) based on production potential, number of milking cows, and marketing practices. A STATA, version 12 software was used for analyses. The results showed that both entrepreneurial and typical dairy farmers in Asella ranked diseases and feed shortages as their main risks, closely followed by lack of access to inputs and services and milk market fluctuations. Both entrepreneurial and typical dairy farmers in Bishoftu ranked feed shortages as their main risk, followed by diseases and issues of poor genetics and reproduction. Vaccination, treatment, deworming with commercial drugs, and keeping animals and barns hygienic were the major coping strategies adopted to deal with diseases, parasites, and pests in both study areas. Major coping strategies to deal with feed shortages were utilizing crop residues, supplementary feed, fodder, and non-convectional feed. The study concludes that entrepreneurial dairy farmers have more effective coping strategies than typical dairy farmers in both study areas. It is essential for dairy farmers to comprehend the requirement to employ varied coping strategies to manage the risks involved in dairy farming to ensure the sustainability of dairy farming in the future.

1. Introduction

Multiple risks constrain dairy production. The nature and magnitude of these risks differ between production systems and agroecologies. Some factors that can influence dairy production are crosscutting across dairy production systems and agroecologies; others are system-specific (Tegegne et al., Citation2013). The most important constraints associated with livestock development in Ethiopia are technical and institutional factors. Technical constraints include poor genetic makeup of the animals, insufficient and low-quality feed sources, unavailability and prohibitive prices of improved breeds, and widespread disease. Institutional constraints include poor linkages between technology sources such as research centres and end users, policy gaps, and limited extension and financial services Shapiro et al. (Citation2015). Similarly, Wouters and van der Lee (Citation2009) revealed that small-scale milk producers in developing countries are facing market challenges next to technical and institutional challenges.

Various studies specify the main risks in Ethiopia. Studies in Gondar town showed that land shortage, scarcity and high prices of feed, seasonality of demand (particularly in fasting periods), and absence of a processing industry were the major challenges to dairy production and marketing in the area (Getachew & Tadele, Citation2015). Correspondingly, Duguma and Janssens (Citation2016) studies in Jimma town stated that feed shortage was a major bottleneck to increase milk production, especially in the dry seasons. These authors reported that farmers adopted various strategies to cope with dry season feed scarcity, i.e. by increasing the use of agro-industrial by-products, concentrate mix, hay, and non-conventional feeds, purchasing green feeds when available, and reducing herd size. To cope with a turbulent environment, dairy farmers need to build the capacity of their businesses to be able to better deal with periods of poor performance and capture the opportunities that arise to perform better (Detre et al., Citation2006).

Although livestock farmers’ perceptions of risk and management strategies have received some attention in developed economies, little specific attention has been paid to developing economies (Ahsan, Citation2011). This is despite the fact that risk in livestock farming is reported to be increasing in the arid and semi-arid regions of East Africa (Chantarat et al., Citation2013; Headey et al., Citation2014). Risk-reducing strategies are often used in combination with one another, because no single strategy can cover all of the risks likely to be encountered (Kahan, Citation2008). Coping strategies to alleviate the constraints to livestock production include improved feed production and conservation, veterinary health care and services, and increasing availability and quality of water during the dry season (Belay et al., Citation2013; Duguma & Janssens, Citation2016; Hussen, Citation2007).

Hence, risk management strategies depend on the type of risk, the costs and effectiveness of the available instruments, education status, technology and infrastructure development (Hoogeveen et al., Citation2004). Understanding the major risks (constraints) of dairy cattle farming and coping strategies used by farmers to overcome and deal with the risks is important in order to identify appropriate research and development interventions to enhance the health and performance of dairy cattle. As there was no such work done in the present study areas, the objective of this study was to identify risk coping strategies of typical and entrepreneurial smallholder dairy farmers that they employ to deal with the shocks and stresses that they encounter in dairy farming in Ethiopia.

2. MATERIALS and METHODS

2.1. Description of the study area

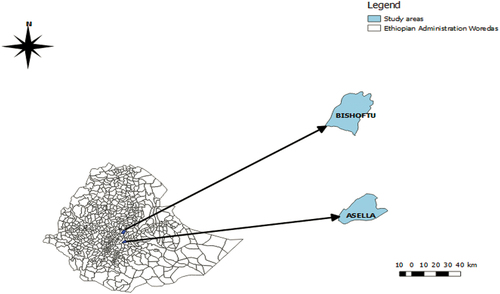

The study was conducted in the central highlands of Ethiopia that fall in the administrative territory of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia as indicated on . These two areas were selected based on their production potential, availability of dairy farms with different sizes, and milk marketing opportunities. A brief description of the selected towns is presented below.

2.1.1. Bishoftu

Bishoftu is located 45 km Southeast of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The town is located in Ada’a district of East Showa Zone of Oromia Regional State, at 8°45′N 38°59′E, at an altitude of 1850 metres above sea level in the central highlands of Ethiopia. A mixed farming system is practiced in the area. The main crop and livestock in the areas are teff and cattle, respectively. It is well known for high agricultural potential, with good access to markets for quality agricultural products, including milk, dairy products, and vegetables. Dairy production in the area is growing quickly. Many farm households are engaged in dairy production for their income and consumption. Availability of feed processing plants, veterinary services and access to Addis Abeba dairy markets help farmers to expand their dairy production.

2.1.2. Asella

Asella town is located in Oromia Regional State, in the Tiyo district of Arsi Zone, 175 km Southeast of Addis Ababa, at 7°57′N 39°7′E, with an elevation of 2,430 metres. The area is characterized by crop-livestock, a mixed farming system where livestock in general and dairy production in particular contributes significantly to livelihoods of the smallholder farmers. Market-oriented dairy production based on crossbred dairy cows is practiced in the district, but mainly in or close to the towns. Milk marketing at the time of the survey was mainly focused on Asella town. Benefits fetched from the livestock sector are below the district’s potential. In order to improve livestock production and to enhance the benefits obtained, understanding the problems, risks, shocks and opportunities existing within this sector is important.

2.2. Study design

A cross-sectional comparative study was conducted to examine the coping strategies used by typical and entrepreneurial smallholder farmers to deal with the shocks and stressors of dairy production. Both qualitative and quantitative research approaches were used to conduct the study. Individual smallholder dairy producers were interviewed with the help of a prepared questionnaire and a focus group discussion.

2.2.1. Sampling procedures

Secondary information from Woreda Livestock Development and Fisheries Offices and dairy cooperatives was utilized to select kebeles (villages) and to categorize dairy farmers. Dairy farmers were purposely categorized into two groups (typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers) based on their production potential, number of milking cows possessed, and marketing practices (Shadbolt, Citation2016). Typical smallholder dairy farmers were those who had 1–2 milking cows, supplied 5–12 l/day to the market, and economized on external inputs. Entrepreneurial smallholder dairy farmers were those who had at least three milking cows and do dairy as business, evidenced by more intensive dairy production and marketing practices; over the past 5 years marketing at least 25 l of milk per day to dairy cooperatives, restaurants, private processors or directly to customers; being more willing to take loans; and buy more inputs and services from outside as compared to typical smallholders. Thirty typical and 30 entrepreneurial dairy farmers were randomly selected for interviewing from Bishoftu area as well as from Asella area, total 120 dairy farms.

2.2.2. Sample size determinations

The sample size was determined by using the mathematical model of (Arsham, Citation2005). The sample size, n, can then be expressed as largest integer less than or equal to 0.25/SE2, with standard error (SE) of 0.0456 with 95% coefficient interval as follows, N = 0.25/0.04562 = 120.

2.2.3. Method of data collection

2.2.3.1. Survey questionnaire

A semi-structured questionnaire was prepared and pre-tested with two typical and two entrepreneurial smallholder farms in Bishoftu area, after which the questionnaire was revised. Training was given to one co-interviewer on how to administer the questionnaire to capture appropriate data. Interviews were carried out from December 2017 to April 2018, and done by the first author together with the trained interviewer and facilitators/experts from the respective Livestock and Fisheries Offices and dairy cooperatives, who served as a local guide to lead the selected farmers. The interviews were carried out at the farmer’s home, to enable counter checking of the farmer’s response with respect to the availability of dairy farming, number of lactating cows and species, and overall management of dairy farming.

The questionnaire started with collection of basic data such as household characteristics (gender, age, and position of respondents, major household income, labour and skills) and basic farm data (herd size, total number of milking and dry cows, livelihood strategies and sources of income, daily milk yield during rain and dry seasons, land size, and water source). The questionnaire then asked the farmer to prioritize risks from a long list, i.e. feed shortage, diseases, parasites and pests, difficulties with access to inputs & services in terms of price, market fluctuations in demand for/price of milk, issues of poor genetics & reproduction, water shortage (on-going) and environmental impact/manure-waste disposal and management. These risk areas (constraints) were drawn from previous studies on the constraints of dairy farming undertaken in Ethiopia. The top three risks prioritized by the dairy farmer were then explored in more detail in terms of coping strategies used.

2.2.3.2. Focus group discussions

Qualitative data collection was used to obtain in-depth information by using a semi-structured focus group discussion after the individual interviews were conducted. FGD facilitators used topical outlines to guide discussion, with focus on the nature of risks and stresses experienced by the community, the frequency of the most important risks that threatened dairy farming in the study area, common responses to these risks and how communities were coping with the risks, what role social capital played in coping with these risks, and how community structures held up under risks. The participants were asked for permission for digital recording of the discussions. The total number of participants per group or categories was held within a range of 6–12 people. In total, eight focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted, as separate FGDs were held for male and female farmers and for each dairy farmer category in each study area.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data entry and cleaning was done using Microsoft Excel 2010. Quantitative data analysis was conducted using STATA software version 12 to obtain descriptive statistics, tabulation (percentages), Pearson chi-square tests for association, and independent group mean t-test. Statistically significant differences were considered for p value <0.05. The qualitative information from the FGD (audio records and notes) was transcribed and coded. The information was then used to identify patterns in responses and contextual information to help explain and interpret the quantitative findings.

3. Results

3.1. Household characteristics in the study areas

The percentages of female respondents in both study areas were slightly higher (53.33% in Bishoftu and 51.67% in Asella) (). The ages of the majority of dairy farmers in the Bishoftu area ranged from 31 to 40 years (31.67%). This result showed that people of the most productive age are actively engaged in dairy farm activities, which in turn have the capacity to build the coping mechanisms of dairy farming for long-term sustainability. The majority of dairy farmers in the Asella area were in the 41–50 age bracket (30%).

Table 1. Gender and position of respondents in study areas.

The ages of the most entrepreneurial dairy farmers in both study areas ranged from 31 to 40 years (). This revealed that entrepreneurial dairy farmers actively engaged in dairy farming management contribute to enhanced coping methods as compared to traditional dairy farming. The majority of respondents in the present study had formal education, which is important to understand extension messages and quickly realize the importance of new technologies.

Table 2. Age and educational status of respondents.

3.1.1. Major sources of food and income

The major sources of food and income contributing to livelihood, obtained from both on-farm and off-farm activities are presented in . Income and food from on-farm activities were significantly larger than from off-farm activities in both study areas. (p < 0.05)

3.1.2. Dairy farming experience

The dairy farming experience of dairy farmers is presented in . About 50% and 30.55% of the respondents in Asella and Bishoftu, respectively, have 10–15 years’ experience. The smallest category of respondents had more than 20 years of experience in both study areas. The entrepreneurial dairy farmers had more years of farming experience when compared to typical dairy farmers in both study areas.

Table 3. Years of farming experience of dairy farmers in the study areas.

3.1.3. Milk production during rainy and dry seasons, and purposes of producing milk

Overall, average milk production for lactating cows in both study areas was significantly higher during the rainy season than the dry season (P 0.001) (). The mean and standard error of milk production during both seasons were significantly higher for entrepreneurial dairy farmers than for typical dairy farmers in the Bishoftu and Asella areas (P 0.001). Most of the entrepreneurial dairy farmers in both study areas were proportional sold their milk (). Thus, 93.17% and 94.12% of the entrepreneurial dairy farmers in Asella and Bishoftu, respectively, indicated that they produce milk in order to sell it or get money. The typical dairy farmers in Asella and Bishoftu areas also were producing milk for sale 87.97% and 92.13%, respectively. The reasons could be the availability of different dairy cooperatives and processors, nearness to a city or town with high numbers of consumers, more awareness of dairy farmer who see dairy cattle as income and business.

Figure 3. Proportions of milk sold and consumed for typical and entrepreneurial farmers in the study areas.

Table 4. Average milk production per herd during rainy and dry seasons.

3.2. Prioritized risks associated with dairy farming

The most important risks associated with dairy farming were prioritized by survey respondents, based on the perceived severity/impact on their farming, as indicated in . Perceptions of risk are based on subjective beliefs about the occurrence of uncertain events and their subsequent impact. In Asella, both farmer types ranked diseases and feed shortage as the main risks, closely followed by difficulties with access to inputs & services and milk market fluctuations. In Bishoftu, feed shortage clearly ranks highest, followed by diseases. Issues of poor genetics and reproduction then followed in both areas. The other risk areas, i.e. water shortage, environmental impact and manure management, had indices lower than 0.1 for all farm types.

Table 5. Major risks of dairy farming ranked by dairy farmers in study areas.

3.3. Dairy farmers’ coping strategies

3.3.1. Coping strategies to deal with diseases, parasites and pests

lists the major coping strategies that dairy farmers employ to deal with diseases, parasites, and pests. In both study areas, the most common coping strategies were preventive practices: vaccination, improving housing or sheds, and proper animal and barn hygiene, augmented by curative practice of treatment by veterinarian or animal health worker. The use of commercial deworming drugs, better animal diets, self-administered medication to treat illnesses, and the slaughter of sick animals were among the less widely reported strategies. The use of traditional remedies for illness prevention or treatment and animal spraying or dipping (against acaricides) were less often mentioned methods. Entrepreneurial farmers in Bishoftu reported using the highest average number of coping strategies.

Table 6. Frequency of reported strategies to cope with diseases, parasites and pests.

3.3.2. Coping strategies to deal with a feed shortage

Dairy farmers used different strategies (practices) to deal with the risk of feed shortage, stemming from land scarcity (). Both typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers in Asella mainly used crop residues, dairy meals, industrial by-products, supplementary feeds, commercial mineral premix, home-processed feeds, purchased fodders, and haymaking. Additionally, the FGDs pointed out the use of non-conventional feed like atela (brint) and beverages of local katikala and wet brewery waste, especially during dry season. It was a common practice for typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers in Bishoftu to deal with feed shortage by use of crop residues, hay, supplementary feeds, purchase brewer’s wastes, and home processed feed (from by-products). The entrepreneurial dairy farmers in both study areas used higher percentages of home processing of mixed ration.

Table 7. Frequency of reported strategies to deal with feed shortage.

Coping strategies in both Asella and Bishoftu areas were almost identical, except that in Asella area some farmers applied to cut and carry grazing that was not used in Bishoftu, as land holdings per dairy farmers in Asella area were larger than in Bishoftu area. FGDs in Asella indicated that they adopted several other coping strategies, i.e. changing between feed resources based on availability and cost, purchasing feed ingredients in bulk, using crop residues, and reducing the number of unproductive cattle in the herd.

3.3.3. Coping strategies to deal with issues of poor genetics and reproduction

Coping mechanisms to deal with issues of poor genetics are presented in . The smallholder dairy farmers in the study areas exploited different coping strategies to mitigate the issue of poor genetics and reproduction by using good feeding (quality of supplementary feed), follow-up by both government and private artificial insemination technicians, and limited use of bull service when a cow did not conceive by artificial insemination.

Table 8. Frequency of reported practices to cope with issues of poor genetics and reproduction.

3.3.4. Coping strategies to deal with the difficulties in access to inputs and services

Having positive relationships with input suppliers, receiving credit from input suppliers, purchasing inputs from authorized dealers, and reducing the use of external inputs were identified as the main strategies for coping by both typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers in both study areas (). Generally, the FGD results suggested that the contribution of both private and public sector in livestock/dairy input has been limited to supplies of veterinary drugs and services, roughage and concentrate feed, and processing equipment and utensils. This is especially the case in Asella area. Moreover, FGD results in Bishoftu revealed that both typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers had an advantage over farmers in Asella, because the dairy farmers in Bishoftu have better access to information, feed (such as a large feed supplier), various veterinary services and inputs from private mobile clinics in town, AI service, and access to credit for inputs.

Table 9. Frequency of reported practices to deal with difficulties in input supply.

3.3.5. Coping strategies to deal with milk market fluctuations

The major coping strategies of entrepreneurial and typical dairy farmers in Bishoftu area indicated that sale to cooperative society and sale to private processors to deal with market milk demand or price fluctuation (). However, both entrepreneurial and typical dairy farmer in Asella area were sale to informal trader/merchant, restaurant, cafe and hotel and home processing to deal with market milk demand or price fluctuation ).

Table 10. Frequency of reported practices to deal with market fluctuations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Farming characteristics

The percentages of female respondents in both study areas were slightly higher (53.33% in Bishoftu and 51.67% in Asella). This result was consistent with the reports of (Aweke & Mekibib, Citation2017; Katongole et al., Citation2012), who reported that the majority of respondents were female, 63.3% in Kampala (Uganda) and 53.8% in small-scale dairy farming in Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), respectively. The majority of the respondents in both study areas were farm owners, which agreed with the reports made by (Aweke & Mekibib, Citation2017; Moges, Citation2015).

The ages of the majority of dairy farmers in the Bishoftu area ranged from 31 to 40 years (31.67%). This result was related to the finding of (Hamza et al., Citation2015), who reported 45% of 30–40-year-olds in southern Sudan. This result showed that people of the most productive age are actively engaged in dairy farm activities, which in turn have the capacity to build the coping mechanisms of dairy farming for long-term sustainability. On the contrary, the majority of dairy farmers in the Asella area were in the 41–50 age bracket (30%). This result agrees with the finding of (Welearegay, Citation2012), who reported that age ranged from 40 to 45 years in Hawassa City. The present study was consistent with the finding of Tessema et al. (Citation2013), who reported that the average age of household heads was 45 years in the Adama-Asella milkshed. Education is an important entry point for empowerment of communities and an instrument to sustainable development. In this context, the majority of the respondents in both study areas were educated except the typical smallholder dairy farmers; a few respondents were illiterate or never went to school. The finding was agreement with the study of (Tadesse et al. Citation2014) who had reported that 73% of households were the secondary school, 20% primary school, 5% diploma holder, and 3% were illiterate the case of in Ada’a Liben Woreda. Evidence from the focus group discussions revealed that all entrepreneurial participants were educated, and they appeared to have more knowledge and skills for strategic planning of dairy farming in the long term than typical dairy farmer participants. According to (Ofuoku et al., Citation2009), farmers with high educational levels usually adopt new technologies more rapidly than lower-educated farmers. Adebabay (Citation2009) suggested that the role of education is obvious in affecting household income, adopting technologies, demography, health, and as a whole, the socioeconomic status of the family as well.

The present study also revealed that the sources of income and food from on-farm activities were significantly greater than off-farm activities in both study areas (p < 0.05). The results were comparable with the finding of (Terefe et al., Citation2014) who reported that the sources of income for livelihood strategies of Dale and Shebedino woreda of Southern Ethiopia mainly come from on-farm activities than off-farm.

The present study showed that the overall average milk production for all milking cows in both studies was highest during the rainy season than in the dry season. In Asella area, daily milk production during rainy season was 43.47 ± 4.14 liters/herd and dry seasons 41.4 ± 3.97 l/herd. Meanwhile, Bishoftu during rainy and dry seasons were accounted for 43.47 ± 4.14 l/herd and 41.4 ± 3.97 l/herd, respectively. Welearegay (Citation2012) reported that 53.9% of the farmers had higher milk production during the wet season than during the dry season, which accounts for 0.9% and depends on feed availability (45.6%) in the small-scale dairy farming system. The mean and standard error of milk production during both seasons were significantly higher for entrepreneurial dairy farmers than for typical dairy farmers in the Bishoftu and Asella areas (P 0.001). Because entrepreneurial dairy farmers are those who actively follow their dairy cattle, consider farming a business, and buy more inputs and services from outside than typical dairy farmers. This result is also consistent with the findings of Welearegay (Citation2012), who reported that higher milk production is reported by medium- and large-scale dairy farmers than by small-scale dairy farmers.

Most urban dairy producers are engaged in the dairy business to generate income; a few households and some per-urban keep dairy cow mainly local breeds to produce milk for household consumption. Accordingly, 93.17% and 87.97% of entrepreneurial and typical dairy farmers in Asella who sell their milk, respectively. Also, 94.12% and 92.13% of entrepreneurial and typical dairy farmers in Bishofu sell their milk. The results were higher than the findings of (Sintayehu et al., Citation2008; Welearegay, Citation2012) who reported that 78.8% and 74.2% of dairy producers in the urban area of Hawassa produce milk primarily for sale, respectively. The proportion of production that was sold by entrepreneurial dairy farmers in both Bishoftu and Asella areas was significantly higher than that of typical dairy farmers (p < 0.001).

4.2. Prioritizing risks associated with dairy farming and coping strategies of farmers for their risks

Perceptions of risk are based on subjective beliefs about the occurrence of uncertain events and their subsequent impact. In Asella, both farmer types ranked diseases and feed shortage as the main risks, closely followed by difficulties with access to inputs & services and milk market fluctuations. In Bishoftu, feed shortage clearly ranks highest, followed by diseases. Issues of poor genetics and reproduction then followed in both areas.

These findings are comparable with the reports of various authors who either found diseases as major risk area, followed by feed shortage - e.g. (Megersa et al., Citation2011), for medium scale farms in Bishoftu, and (Tibezinda et al., Citation2016) in southwestern Uganda – or feed shortage followed by diseases – e.g. (Belay et al., Citation2013; Galmessa et al., Citation2013; Katongole et al., Citation2012; Kebede, Citation2015; Yetera et al., Citation2018). Terefe et al. (Citation2014) identified feed shortage, access to improved breeds, and market and credit services as major development constraints in Southern Ethiopia. The high risk of diseases in Asella was underlined by the participants of the entrepreneurial male FGD in Asella. They were reluctant to participate in the discussions, because they were expecting immediate solutions for the outbreak of Lumpy Skin Disease, as a recent outbreak of this disease killed many cattle in the area, supposedly due to the unavailability of regular and timely vaccination.

Both entrepreneurial and typical FGDs in Bishoftu area reported that they had good opportunity to deal with diseases, parasites, and pests because they have access to many private or mobile clinics, the presence of the National Veterinary Institute (NVI), and the Addis Ababa University College of Veterinary Medicine of Veterinary Teaching Hospital. These findings were consistent with (Jibat et al., Citation2015) who reported that the public veterinary service in the same district was considered as the preferred choice for livestock owners for its effectiveness and affordability compared to private veterinary services in their areas. The female-typical farmers’ FGD in Asella pointed out the effective use of traditional medicine to deal with bloating of cattle (a blend of oil, soap, and chilli pepper). Similarly, the female typical farmers’ FGD in Bishoftu indicated that use of the traditional medicine such as the leaf of Milia tree and drenched in coca cola and beer has been common in the community to deal with bloating of dairy cattle.

Dairy farmers in the study areas used different strategies (practices) to deal with the risk of feed shortage due to land scarcity. Both typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers in Asellaand Bishoftu were mainly used crop residues, dairy meals, industrial by-products, supplementary feeds, commercial mineral premix, home-processed feeds, purchased fodders, and haymaking to coup the shortage of feed. The results match in lined with findings of (Belay et al., Citation2013) in Ginchi watershed (Ethiopia) who reported that increasing of the utilization of crop residues was ranked first for coping with feed shortage. Duguma and Janssens (Citation2016) in Jimma town reported that coping strategies during dry season feed scarcity were increased use of agro-industrial by-products, premix, hay, and non-conventional feeds; purchasing green feeds when available; and reducing herd size. Another comparable study reported that in Jimma and Sebata town indicated that almost all dairy farmers depend on purchased supplementary feeds (Wondatir, Citation2010). These results were also in agreement with the study of (Beyene et al., Citation2015) at Horo Guduru Wellaga, where the coping strategies were use of crop residues with some grazing and use of homemade feed like atela (brint). Similarly, Belay et al. (Citation2013) suggested that increased utilization of crop residues and production of improved forages were major coping strategies to deal with feed shortage in Ginchi watershed.

Moreover, typical dairy farmers in Bishoftu indicated the use of crop residues, industrial by-products, and fodder as coping strategies. In contrast, to this study (Katongole et al., Citation2012; Malede et al., Citation2015), reported that the use of harvested natural forage was the primary coping strategy to deal with feed shortages in the areas. However, the male entrepreneurial FGD suggested that improving forage on selected land, establishing a forage seed bank in the group, and improving and utilizing crop residue and hay were the recommended solutions to mitigate feed shortages.

Artificial insemination was the main coping strategy used by dairy farmers in both study areas to deal with issues of poor reproduction. Natural or bull service was used only when cows/heifers failed to become pregnant with artificial insemination service and when semen or artificial insemination technicians were not available. Good management can alleviate some of the stresses/risks associated with high production; producers are looking for genetic means to build a more efficient and robust cow for both current and future production environments. Genetic parameters for traits of economic importance need to be identified and validated, thus permitting the development of improved genetic evaluation systems for traits associated with cow profitability (Koeck et al., Citation2012).

The major inputs for livestock development include animal genetic resources, feeds and forages, veterinary drugs, vaccines, machinery equipment and utensils as well as knowledge (Tegegne et al., Citation2006). The present study identified different coping strategies to deal with the issue of input supply, such as maintaining a good relationship with input suppliers, taking credit from stockiest/delayed payment, and reduce the purchase of external inputs. The focus group discussions result suggested that the contribution of the private sector and even the government sector in livestock/dairy input has been limited to supplies of veterinary drugs and services, roughage and concentrate feed, and processing equipment and utensils. This is especially the case in Asella areas higher than in Bishoftu. Moreover, FGDs results in Bishoftu revealed that both typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers had an advantage over in Asella in terms of coping with difficulties of input supply. Because of the dairy farmers in Bishoftu have better access to information, better access to feed and veterinary service input (such as AKF feed supplier and varies inputs from private mobile clinics in town), AI service, and access of input credit services than the dairy farmers in Asella area.

The milk marketing system in Ethiopia is not well developed. About 98% of national milk production is marketed through informal marketing channels (Makoni et al., Citation2014). The traditional processing and marketing of dairy products, especially traditional lactic butter, dominate the Ethiopian dairy sector. Formal milk markets are particularly limited to urban and peri-urban areas of Ethiopia (SNV Netherlands Development Organization, Citation2008).

The present study pointed out that farmers had many opportunities to sell their milk directly through the formal marketing system, particularly in Bishoftu area, to deal with issues of market fluctuation. Bishoftu FGD results pointed out stability and continuation of milk sales, even during the fasting period. This can be explained by the many functional dairy co-operatives and private collectors in Bishoftu, such as Ada’a dairy cooperative, Genesis dairy farm, Sebata Agro-Industry (MAMA), Holland dairy PLC and LEMA milk house, which have played a significant role in fostering dairy development, primarily by providing a stable market environment and service delivery to farmers. On the opposite, dairy farmers in Asella were forced to sell their milk through informal marketing channels and to bars, hotels, and restaurants to cope with market challenges due to an absence of functional dairy cooperatives and milk collectors in an area. Other strategies FGDs in Asella area mentioned that they sell their milk to Muslim believers in bulk and change to local processing (butter and cheese) transported to Addis, Adama, and Hawassa during the fasting period. Tessema et al. (Citation2013) observed that Asella town has a large number of Muslim inhabitants who do not have a fasting culture that discourages consumption of milk and dairy products.

5. Conclusion

Risk perceptions are based on subjective beliefs about the occurrence of uncertain occurrences and their consequences. Dairy farmers were asked to prioritize the most serious threats to their dairy operations. As a result, diseases, parasites, and pests; feed shortage; difficulties with access to inputs and services in terms of price, quality, or availability; issues with poor genetics and reproduction; and market fluctuation were the top five risks ranked by typical dairy farmers in Asella. Typical and entrepreneurial dairy farmers in Bishoftu prioritized feed shortage, followed by diseases, parasites and pests, issues of poor genetics, market fluctuation, and difficulties in input supply in terms of price, quality or affordability.

Dairy farmers have adopted several coping strategies to deal with the top five issues, as well as management of manure and water shortage. Adoption of strategies depends on availability of resources and cost of strategies, including access to accurate information sources and availability of extension workers and AI technicians, farmers own economic and financial situation, resources (such as physical assets and technology), knowledge and skills, educational status, farming experience, livelihood strategies, and attitude towards risk. The coping strategies that interviewed dairy farmers employed to deal with risks differed greatly, even within the same geographical location. The results showed that entrepreneurial smallholder dairy farmers had more effective coping mechanisms than typical smallholder dairy farmers to deal with the risks they face in dairy farming.

6. Recommendations

Based on the results obtained from this study, we recommend to increase access to information services and early warning systems for smallholder dairy farmers. Because the provision of timely information allows the households of smallholder dairy farmers exposed to hazards to take timely action to avoid or reduce their risk and prepare for effective responses. The government and NGO sectors should increase access to appropriate innovative financial products and services (e.g. loans) in order to invest in adaptive strategies and savings structures that allow for debt-free recovery, which further helps to reduce risks from shocks and stresses in dairy farming.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank NWO-WOTRO for financial assistance (project W 08.260.301).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adebabay, K. (2009). Characterization of Milk Production Systems, Marketing and On-Farm Evaluation of the Effect of Feed Supplementation Milk Yield and Milk Composition of Cows at Bure District, Ethiopia. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Animal Science and Technology School of Graduate Studies, Bahir Dar University, 1–23.

- Ahsan, D. A. (2011). Farmers’ motivations, risk perceptions and risk management strategies in a developing economy: Bangladesh experience. Journal of Risk Research, 14, 325–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.541558

- Arsham, H. (2005). In D. C. church & W. C. Pond (Eds.), Questionnaire design and surveys sampling 1982 Basic Animal Nutrition and Feeding Records (9th ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

- Aweke, S., & Mekibib, B. (2017). Major production problems of dairy cows of different farm scales located in the capital city of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of Veterinary Science & Technology, 8, 483. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7579.1000483

- Belay, D., Getachew, E., Azage, T., & Hegde, B. H. (2013). Farmers perceived livestock production constraints in Ginchi watershed area: Result of participatory rural appraisal. International Journal of Livestock Production, 4, 128–134. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2013.0164

- Beyene, B., Hundie, D., & Gobena, G. (2015). Assessment on dairy production system and its constraints in horoguduru wollega zone, Western Ethiopia. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 4, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.4314/star.v4i2.28

- Chantarat, S., Mude, A. G., Barrett, C. B., & Carter, M. R. (2013). Designing index based livestock insurance for managing asset risk in northern Kenya. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 80, 205–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2012.01463.x

- Detre, J., Briggeman, B., Boehlje, M., & Gray, A. W. (2006). Score carding and heat mapping: Tools and concepts for assessing strategic uncertainty. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 9(1), 71–92.

- Duguma, B., & Janssens, G. P. J. (2016). Assessment of feed resources, feeding practices and coping strategies to feed scarcity by smallholder urban dairy producers in Jimma town, Ethiopia. Springer Plus, 5, 717. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2417-9 PMID: 27375986; PMCID: PMC4908093.Galmessa.

- Galmessa, U., Dessalegn, J., Tola, A., Prasad, S., & Kebede, L. M. (2013). Dairy production potential and challenges in western Oromia milk value chain, Oromia, Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Sustainability, 2(1), 1–21.

- Getachew, M., & Tadele, Y. (2015). Constraints and opportunities of dairy cattle production in chencha and Kucha districts, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 5(15), 1–7. www.iiste.org

- Hamza, A. E., Eltahir, S. S., Hiam, M. E., & Makarim, A. G. (2015). A study of management, husbandry practices and production constraints of cross-breed dairy cattle in South Darfur State, Sudan. Online Journal of Animal and Feed Research, 5(2), 62–67. http://www.science-line.com/index/

- Headey, D., Taffesse, A. S., & You, L. (2014). Diversification and development in pastoralist Ethiopia. World Development, 56, 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.015

- Hoogeveen, J., Tesliuc, E., Vakis, R., & Dercon, S. (2004). A guide to the analysis of risk, vulnerability and vulnerable groups. World Bank. Available on line at http://siteresources. World Bank. Org/INTSRM/Publications/20316319/RVA. Pdf. Processed.

- Hussen, K. (2007). Characterization of Milk Production System and Opportunity for Market Orientation: A Case Study of Mieso District, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. PhD Dissertation, Haramaya University, 2010.

- Jibat, T., Mengistu, A., & Girmay, K. (2015). Assessment of veterinary services in central Ethiopia: A case study in Ada’a district of Oromia region, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 19, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4314/evj.v19i2.9

- Kahan, D. (2008). Managing risk in farming. Farm management extension guide. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Katongole, C. B., Nambi-Kasozi, J., Lumu, R., Bareeba, F., Presto, M., Ivarsson, E., & Lindberg, J. E. (2012). Strategies for coping with feed scarcity among urban and peri-urban livestock farmers in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 113(2), 165–174.

- Kebede, H. (2015). Productive and reproductive performance of holstein-friesian cows under farmers management in Hossana Town, Ethiopia. International Journal of Dairy Science, 10, 126–133. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijds.2015.126.133

- Koeck, A., Miglior, F., Kelton, D. F., & Schenkel, F. S. (2012). Health recording in Canadian holsteins: Data and genetic parameters. Journal of Dairy Science, 95, 4099–4108. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2011-5127

- Makoni, N., Mwai, R., Redda, T., van der Zijpp, A. J., & van der Lee, J. (2014). White Gold : Opportunities for dairy sector development collaboration in East Africa. Wageningen: Centre for Development Innovation. 205.

- Malede, B., Kalkidan, T., & Maya, T. (2015). Constraints and opportunities on small scale dairy production and marketing in Gondar Town. World Journal of Dairy & Food Sciences, 10, 90–94. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wjdfs.2015.10.2.95116

- Megersa, M., Feyisa, A., Wondimu, A., & Jibat, T. (2011). Herd composition and characteristics of dairy production in Bishoftu Town, Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Extension & Rural Development, 3(6), 113–117.

- Moges, N. (2015). Survey on dairy farm management and infertility problems in small, medium and large scale dairy farms in and around Gondar, North West Ethiopia. Journal of Dairy Veterinary Animal Resources, 2, 00054. https://doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2015.02.00054

- Ofuoku, A. U., Egho, E. O., & Enujeke, E. C. (2009). Integrated pest management (IPM) adoption among farmers in central agro-ecological zone of Delta State, Nigeria. Advances in Biological Research, 3(4), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.15835/arspa.v83i3-4.9078

- Shadbolt, N. M. (2016). Resilience, risk and entrepreneurship. International Food and Agribusiness Management, 19, 33–52. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.234955

- Shapiro, B. I., Gebru, G., Desta, S., Negassa, A., Nigussie, K., Aboset, G., & Mechal, H. (2015). Ethiopia livestock master plan. ILRI Project Report Nairobi, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI): 142.

- Sintayehu, T., Fekadu, B., Azage, T., & Berhanu, G. (2008). Dairy production, processing and marketing systems of shashemene- Dilla area, South Ethiopia. IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project Working Paper 9. ILRI, International Livestock Research Institute. 62.

- SNV (Netherlands Development Organization). (2008). Study on dairy investment opportunities in Ethiopia. SNV Netherlands Development Organization, Addis Ababa.

- Tadesse, M., Melesse, A., Tegegne, A., & Melesse, K. (2014). Urban dairy production system, the case of Ada’a Liben Woreda dairy and dairy products marketing association. livestock and economic growth: Value chains as pathways for development. In proceedings of the 21th Annual Conference of the Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP) held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Augest 28–30.

- Tegegne, A., Gebremedhin, B., & Hoekstra, D. (2006). Input supply system and services for market-oriented livestock production in Ethiopia. IN: Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of the Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP), held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, September 5-7, 2006. Part I: Plenary session. ESAP Proceedings. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): 1–19.

- Tegegne, A., Gebremedhin, B., Hoekstra, D., Belay, B., & Mekasha, Y. (2013). Smallholder dairy production and marketing systems in Ethiopia: IPMS experiences and opportunities for market-oriented development. IPMS (improving productivity and market success) of Ethiopian farmers project working paper 31. ILRI: 78.

- Terefe, T., Oosting, S. J., & van der Lee, J. (2014). Smallholder dairy production: Analysis of development constraints in the dairy value chain of Southern-Ethiopia. Proceedings of the 6th All Africa Conference on Animal Agriculture (AACAA) Nairobi, Kenya.

- Tessema, Y. A., Ayana, A. A., Aweke, C. S., van der Lee, J., & Dereje, M. (2013). Marketing strategies of smallholder dairy farmers in Ethiopia and options for improvement: The case of Adama-Asella Milkshed: Research report of Wageningen Livestock Research: 67.

- Tibezinda, M., Wredle, E., Sabiiti, E. N., & Mpairwe, D. (2016). Feed resource utilization and dairy cattle productivity in the agro-pastoral system of South Western Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 11, 2957–2967. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2016.10785

- Welearegay, H. (2012). Challenges and opportunities of milk production under different urban dairy farm sizes in Hawassa City, Southern Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7, 3860–3866.

- Wondatir, Z. (2010). Livestock Production Systems in Relation with Feed Availability in the Highlands and Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. MSc Thesis, Haramaya University, 160.

- Wouters, A. P., & van der Lee, J. (2009). Smallholder dairy development-drivers, trends and opportunities. Conference paper: AgriProFocus - Heifer Learning Event “Dairy and Development: Dilemmas of scaling-up”, at Veessen, Netherlands, July 2009: 1–10.

- Yetera, A., Urge, M., & Nurfeta, A. (2018). Productive and reproductive performance of local dairy cows in selected districts of sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 9, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2018.0447