ABSTRACT

In Sub-Saharan African, specifically Ghana, the prevalence of dementia, has made the lack of care options available for the aged, a pressing issue. Combined with the slow deterioration of the traditional family system in Ghana and the rapid ageing of the population, the situation seems dire. Experts related to dementia are also severely lacking with care predominantly provided through mental health services. The research supports the provision of a better quality of life for persons living with dementia through dementia-friendly architectural interventions. Data was obtained through the review of 277 publications focused on dementia in Ghana, 2 case studies, as well as the thematic analysis of 15 semi-structured interviews of purposively sampled respondents. The study identified that persons living with dementia in Ghana face challenges with care, with design modifications made based on the needs of the individuals, but without specific guidance. Thus, a design framework is necessary to maximise the effects of design on the quality of life of persons living with dementia. Hitherto, no previous study in Ghana has focused on the living space as an alternative care option for dementia. The Ghanaian context allows for replication of results in other developing nations due to similar socio-economic characteristics.

Points of interest

This article explores the life of persons living with dementia in Ghana by revealing the numerous challenges the implication of the condition has on their livelihood, families, and other internal and external issues.

The possibility of using design to help these persons is explored with emphasis placed on the individualistic nature of the condition.

The plight of persons living with dementia through the eyes of family members, health care experts, designers and care home administrators are discussed.

Conclusions are drawn based on research findings and data collected.

JEL CLASSIFICATION:

1. Introduction

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) it has been predicted that there will be an increase of 7.62 million people living with dementia by 2050 (Guerchet et al., Citation2017; Prince et al., Citation2013), which will be one of the largest globally. Unfortunately, within the Sub- Saharan African region, Ghana is one of the countries most affected by dementia and by 2030, it has been projected that the number of individuals beyond 60 years old will increase by 147% (Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Association, Ghana ADRAG, Citation2016). With this increment of elderly individuals in Ghana, the predominance of dementia will likewise increase, turning the negligence of the situation into a significant issue. Additionally, the knowledge about dementia in Ghana is low (Appiah, Citation2017), and formal considerations for mental well-being is scarce (Roberts et al., Citation2014). Thus, persons living with dementia become dependent on the informal care given by their relatives (Ayisi-Boateng et al., Citation2022), which may affect their lives radically.

Dementia is an umbrella term for several conditions affecting memory, other cognitive abilities and behaviour that interfere significantly with a person’s ability to maintain their activities of daily living, where Alzheimer’s is the most widely recognized and adds to 60–70% of cases (World Health Organisation WHO, Citation2021). Many persons living with dementia live with family or companions; however, a notable number live at home alone (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2012). Unfortunately, many health professionals in Ghana do not wish to specialize in psychiatry, so care from an expertise level is also lacking (Ofori-Atta et al., Citation2010; Smalls-Mantey, Citation2019). These statistics are particularly important, as in Ghana, with the disintegration of the extended family unit and traditional framework, through urbanisation, education and the peaking rate of Christianity, more ageing relatives, rarely have support from their more youthful relatives (Aboderin, Citation2004; Akinny, Citation2016). Change is however emerging, as organizations such as Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Association, Ghana, among others are supporting by organizing programmes to train health professionals and educate care takers and family members on caring for persons living with dementia in Ghana.

Nonetheless, during the progression of this decline of the brain or mind, the requirement for help from others is unavoidable, and the focus moves from support of day by day working and exercises in the early stage, towards comfort and well-being in the late stage (Gaugler et al., Citation2014; Mace & Rabins, Citation2011; Schulz & Martire, Citation2004; van der Steen et al., Citation2014). Ultimately, in the late, extreme phase of dementia, persons living with dementia will be completely reliant on others and will eventually die (Engedal & Haugen, Citation2018; Livingston et al., Citation2017).

Unfortunately, without care, persons living with dementia tend to wander, and in places like Ghana, can be called witches or wizards (Spittel, Citation2014; Spittel et al., Citation2018, Citation2019), and in severe cases, burnt alive (Spittel, Citation2014). Thus, in giving the proper treatment and support to persons living with dementia, in accordance with their own needs and key human rights, information about how individuals with dementia experience and adapt to their present and future life circumstances, is essential. In 2013, Ghana launched its national ageing policy acknowledging the requirement for better nursing facilities for the elderly. Although there are some care homes available in Ghana, none of them have the expertise in caring for persons living with dementia, which makes the situation severe (Akinny, Citation2016; Appiah, Citation2017; Yiranbon et al., Citation2014). Moreover, Ghanaians do not fully accept the concept of care homes for different reasons, including the cost of the home’s services (Akinny, Citation2016). As the seriousness of psychological difficulty develops, living at home without help and management turns out to be increasingly challenging. Despite the foregoing, many persons living with dementia would like to keep up a normal lifestyle (Fukushima et al., Citation2005) and value the outdoors (Duggan et al., Citation2008), although, due to their condition, the outside world can turn into a scary place, especially in the later stages of this condition.

1.1. Problem statement and study justification

Dementia remains one of the biggest problems facing our ageing population, causing more disability in later life than cancer, heart disease or strokes (WHO, Citation2020). Nonetheless, the subject of dementia is not treated as an issue of much gravity, in Ghana and other developing nations (Aboderin, Citation2004; Spittel et al., Citation2018). Unfortunately, the cost implications for dementia are also high, as can be observed from other countries that are implementing strategies according to the WHO Global Plan of Action on Dementia. With the data and projections available to Ghana and its policy makers and the evidence that the prevalence of dementia is unavoidable, it is important for Ghana to take up the task of implementing the necessary strategies to help mitigate any unnecessary cost implications that may arise from negligence (WHO, Citation2020).

Additionally, besides the variables stated above, research has also demonstrated that several persons living with dementia stay in their homes (Dreyer et al., Citation2022), as it serves as a protected space for them, and thus the home has been portrayed as shelter, retreat, and a refuge as it is free from judgement and public observation (Mallett, Citation2004). However, decisions about whether it is yet safe for the individual to stay at home, are challenging and complex. Nevertheless, majority of current principles detailing architectural interventions for persons living with dementia are grounded in studies undertaken in hospital contexts. Similar concepts are assumed to be important for private residences and nursing homes and for encouraging the prolonged usage and navigation of exterior spaces (van Hoof et al., Citation2010) as can be seen in studies condoning the idea of the Hogeweyk Care Concept in the Netherlands (Jenkins & Smythe, Citation2013; Vinick, Citation2019).

According to a 2018 conference presentation on De Hogeweyk, the major goal is to protect and improve residents’ quality of life amid the advancement of dementia (CADTH, Citation2018) and according to evidence supplied by De Hogeweyk founder, antipsychotic usage at the facility has fallen from around 50% of residents before to the dementia village’s implementation to approximately 12% in 2019 (CADTH, Citation2018). In a Lancet review, the use of restraints is suggested as one measurable outcome of dementia care (Livingston et al., Citation2017) noting that, ‘Good evidence is available that person-centred care reduces use of restraint in care homes and hospitals and should be implemented’ (Livingston et al., Citation2017). This demonstrates that the lower levels observed in individuals staying at the Hogeweyk is a positive sign towards dementia care.

Despite this, Ghana’s approach to dementia requires more research, especially with regards to interventions for improved quality of life (Nyame et al., Citation2019). Some of the problems slowing down the progression of care for persons living with dementia in Ghana are highlighted below.

1.1.1. Disregard of dementia, its implications, and the necessary resources required for their daily living

To many people in Ghana, the symptoms of dementia in the old, such as, being absent-minded are the unimportant effects of ageing (Agyeman et al., Citation2019; Ohene, Citation2016). Issues of care for persons living with dementia basically emerge from the absence of information on the condition and absence of mental facilities in Ghana (Nyame et al., Citation2019; Roberts et al., Citation2014). In 2011, ‘there were a hundred and twenty-three (123) mental health outpatient facilities, three (3) psychiatric hospitals, seven (7) community-based psychiatric inpatient units, four (4) community residential facilities and one (1) day treatment centre, which was well below what would be expected for Ghana’s economic status’ (Roberts et al., Citation2014). Ghana´s healthcare system remains unprepared to address the ageing population and the related increase of age-related diseases like dementia, as evidenced by the lack of specialists, and the absence of aged-care wards in hospitals (Spittel et al., Citation2018). Persons living with dementia worry that engaging with the community, may result in stigmatisation related to dementia (Batsch & Mittelman, Citation2012; Spittel et al., Citation2018), thus they remain in their homes, and this comes with its own challenges.

1.1.2. Lack of adaptation of dementia-friendly principles in the design of spaces for persons living with dementia

The ability to engage independently in everyday activities is closely linked to feelings of well-being for persons living with dementia (Alzheimers Society, Citation2021; Andersen et al., Citation2004) and to reduced challenges for carers and family members. Therefore, one way to support persons living with dementia, and carers, is to understand difficulties with daily activities and develop strategies to support them (Woodbridge et al., Citation2018). Unfortunately, in Ghana, care options are limited as experts in geriatric care who diagnose dementia are extremely rare, thus families desiring to comprehend and manage the condition do not have access to the necessary knowledge (Spittel et al., Citation2018). Additionally, although care homes present an alternative care option, those available in Ghana do not specialise in dementia care (Appiah, Citation2017) and thus are not developed to consider the physical environment as an alternative care option for persons living with dementia. Moreover, Ghanaians do not support the concept of care homes despite the break in the traditional care process (Akinny, Citation2016). Research over the last couple of years on dementia in Ghana has focused on dementia prevalence (Agyeman, Citation2019; De Langavant et al., Citation2020), challenges (Gyimah et al., Citation2019; Nyame et al., Citation2019; Spittel et al., Citation2018) and perceptions (Agyeman et al., Citation2019; Brooke & Ojo, Citation2019; Dai et al., Citation2020; Larnyo et al., Citation2020; Spittel et al., Citation2019) and never on the physical environment as an alternative care option. Therefore, there exists a gap in research on the adaptation of dementia-friendly design principles in the design of spaces for persons living with dementia, not only within the care home setting but also private residences.

1.2. Research aim and questions

The aim of the study was to provide a better quality of life through architectural interventions for people living with dementia. To achieve this, the following research questions were established.

What are the current factors influencing the quality of life of persons living with dementia in Ghana?

What aspects of dementia friendly environmental design are currently available in Ghana to support people with dementia?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

The approach to the research involved a series of steps which have been outlined in .

2.1.1. Identifying the respondents

The research adopted a descriptive cross-sectional design. This is because the aim was to understand the intricate details of the daily life and challenges of persons living with dementia by collecting the data at a single point in time. Phenomenological studies were selected as a foundation for this study due to its underlying concepts which include examining the individual’s lived experience. In research conducted by Creswell (Citation1998) and Morse (Citation1994), on sample size determination for phenomenological studies, recommendations stated 5–25 participants and at least 6 participants, respectively. On the other hand,Guest et al. (Citation2006) believes that saturation in thematic analysis is more likely with a sample of twelve. Due to the geographical context, several factors had to be considered during the sampling process. The lack of experts in the field of dementia, psychology, neurology, and geriatrics, as well as the general perceptions surrounding the topic of dementia in Ghana, were among some of the reasons for identifying respondents using purposive sampling. In 2019, Ghana had an estimated 18–25 psychiatrists (Smalls-Mantey, Citation2019) representing an increase from 11 in 2011 (Smalls-Mantey, Citation2019) Additionally not all these individuals dealt specifically with dementia. The respondents were grouped into three (3) main target groups. This included major stakeholders, family and carers of persons living with dementia, and elderly care home administrators. The major stakeholders were further broken down into health experts, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and architects specialised in barrier-free and inclusive design. For persons living with dementia who were not available to participate in the research due to several reasons, proxy interviews were conducted with their caretakers and/or relatives. The purpose of the interviews was to grasp various perspectives of the current state of dementia care in Ghana as well as satisfy the research aim and questions of the study. Consequently, snowball sampling techniques were subsequently utilised to obtain respondents who met the respondent selection criteria. Convenience sampling was finally adopted to set up interviews for those willing and able to partake in the research. All these findings thus formed a basis for the respondent numbers and approach that was utilised in the study. However, due to the limited size restrictions relating to the pool of individuals associated with dementia in Ghana, the number of respondents obtained was a limitation of the study.

2.1.2. Study participation

A total of 15 respondents were obtained with 15 interviews conducted. The health experts contacted included psychiatrists, geriatricians, and a nurse. Their average years of experience was between 11 to 15 years, and their expertise comprised areas that adequately represented the data collected. Health experts were sourced from both public and private health institutions. This included Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH), which represented the southern sector of the country and Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH), which represented the northern part of the country. These hospitals were major referral facilities with specialists relating to the field of dementia. For the private sector, experts sourced had knowledge in geriatrics, psychology, and dementia. It is important to note that, many of the healthcare experts included in the study worked in multiple locations (some private and public) due to the lack of healthcare workers in fields relating to dementia.

To obtain a broader perspective of what it means to care for persons living with dementia, two elderly care homes and two NGOs were included in the study. For the case studies of the elderly care homes included in this study, the specific model targeted was the residential type, meaning they had residential facilities available. This was important to obtain a holistic understanding of the daily lives and routines of any persons living with dementia and carers that were present in these homes. Two facilities were included in the study, as they were the only ones that met the selection criteria and respondents were available to take part in the study. The care home administrators and nurses were interviewed for information about the main challenges faced. Both indoor and outdoor environments of the care home were also assessed and reviewed using principles of dementia friendly design whose fundamentals have been shown to be consistent over the last 30 years (Houston et al., Citation2019), and are available in literature (Alzheimers Disease International, Citation2020; Fleming et al., Citation2017; Government of New Zealand Ministry of Health, Citation2016; Halsall & MacDonald, Citation2015; Mitchell & Burton, Citation2010). The rating system used was the Likert scale, with the rankings as follows: 1 - Poor, 2 - Fair, 3 - Average, 4 - Good, 5 - Excellent. Unfortunately, due to the lack of expertise of architects in inclusive design in Ghana, one specialist from Germany was obtained for the study. To maintain the anonymity of respondents, Health Experts were given the code HE, NGO founders NGOF, inclusive design experts IDE, and family members and carers of persons living with dementia codes based on their names. For instance, for the name Martin Williams, the code generated was Mr. MWs. In total, 5 health experts (one of who doubled as a carer), 1 inclusive design expert, 2 NGO founders, 5 family members, and 2 elderly care homes were included in the study.

2.1.3. Structure of data collection

According to Barrett et al. (Citation2018), to understand and maximise the future of a particular person living with dementia, it is necessary to assess the collective and complete impact of the pharmacological/medical environment, the social and care/support environment, and the material environment on the specific individual. To achieve this, the respondents were asked various questions that encompassed these areas.

A thorough review of literature and review of similar studies (Beck, Citation1998; Caffò et al., Citation2013; Cohen-Mansfield, Citation2001; Daykin et al., Citation2008; Gabriel et al., Citation2014; Letts et al., Citation2011; Padilla, Citation2011; Schipper et al., Citation1996; Torrington, Citation2006) helped to indicate the major themes and issues that were used not only to identify the gaps in knowledge but also to develop the research instrument. The interview structure and questions were also driven by the theoretical framework of the study, which included determinants of health-related quality of life by Schipper et al. Citation1996. Even though other scholars (Ghosh & Dinda, Citation2020; Martinez-Martin et al., Citation2012; Raggi et al., Citation2016; Talarska et al., Citation2018) had similar scopes, the scopes and descriptions by Schipper et al. Citation1996 encompassed all these areas. highlights the various aspects and definitions of this.

Table 1. Determinants of health-related quality of life.

This awareness and categorization of these determinants led to the development of the four major groups that led to the assessment criteria generated to help in the improvement of the quality of life of persons living with dementia in Ghana, through design interventions. The theoretical framework thus generated based on this can be seen in .

2.1.4. Interviewing of respondents

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted via zoom. The respondents were called ahead of schedule and a date and time were set. The interview sections were grouped based on the determinants of quality of life that formed the theoretical framework of the study. Areas of socialising, physical health, economics, and psychology were assessed based on the information obtained from the respondents. The interviews typically lasted between 20 and 40 minutes. Each respondent was briefed on the research topic and its purpose to ensure they had a full understanding and consented to the conditions of engagement. Additionally, permission was sought for the recording of the interviews to help in the transcription process during the presentation and analysis of the data. For individuals who preferred not to be recorded, the decision was respected. The interview was structured depending on the target group and based on the information that needed to be elicited. One common area, however, was the aspect of dementia and design.

2.1.5. Presentation of findings

Data collected was transcribed verbatim based on the recordings. Codes were then generated based on relevant themes that helped address the research questions. The relevant areas of the study included,

Current state of dementia care in Ghana

Translating concepts of Quality of Life (QoL) into architecture

2.1.6. Analysis and discussions of findings

Thematic analysis was utilised using the guidelines outlined by Braun and Clarke Citation(2006). This allowed for the categorisation of verbal and behavioural data which aided in the classification, summarisation, and tabulation of the data to ensure that maximum interpretation was obtained. Thematic analysis was the selected analysis method as the study sought to understand people’s views, opinions, knowledge, experiences, and values concerning the topic of dementia (Gorska et al., Citation2018; Hossain et al., Citation2019; Roche et al., Citation2021). This form of data analysis method employed for the study is flexible and allows for large data sets to be sorted and grouped according to themes that were more common among respondents (Caulfield, Citation2019). This, thus, helped to draw valid conclusions for the study. With the aid of the analysis tool Nvivo 11, the data analysis was documented from the interview transcripts. An inductive approach was adopted as the data obtained determined the major themes that were generated (Streefkerk, Citation2019).

Interview audio recordings that were received with permission from respondents were transcribed verbatim in full manually. To guarantee the validity of the interview sessions, voice recordings were used instead of researcher notes, allowing scrutinization of the original data (Gray, Citation2018). Likewise, the generation of verbatim interview transcripts offered a profound and disclosing perspective (Arksey & Knight, Citation1999; Maxwell, Citation2010) and the validation of the precision of the participants’ experience through informal check-ins were also employed throughout the study (Gray, Citation2018).

Additionally, accumulating data from multiple relevant stakeholder groups (including health care experts, family members and carers of persons living with dementia) not only provided triangulation but also ensured that the study explicitly integrated a broad spectrum of distinct standpoints to ensure that the perspective of one cohort was never conveyed as the ultimate reality (Mays & Pope, Citation2000).

Subsequently, specific passages of the text were highlighted, and codes—shorthand labels—were created. This made it possible to summarize the key ideas and give common meaning to information that had been rehashed by the respondents.

Both major themes and sub-themes were then generated for the various codes by identifying any patterns within the data set. For example, the major theme ‘financial implications’ covered other sub-themes such as lack of funding and support at policy level, lack of investments and planning for healthcare of the elderly and negative financial implications on the family. Here Nvivo played a key role in determining which themes recurred more often. Allowing for the data to be categorised on a priority basis. This then allowed for valid conclusions to be drawn from the data sets.

The themes were then reviewed to ensure that there was a useful and accurate representation of the data obtained. Finally, the themes were defined and named appropriately to prevent ambiguity and misunderstanding and a full and analytical assessment of techniques and approaches assisted in achieving validity.

3. Results

3.1. Current state of dementia care in Ghana

Dementia in Ghana is associated with many myths, and this was clearly identified during the study. The general misconception, as demonstrated by the study, is that the condition is related to old age, and is mainly viewed as a normal part of ageing which is not the case. Additionally, the condition, as well as persons living with dementia are linked to many cultural and superstitious beliefs including witchcraft. This thus poses a great challenge and risk for persons living with dementia in Ghana. From the data collected, education in diverse forms was expressed as a means of improving these perceptions and misconceptions about the condition as well as persons living with the condition in Ghana. Currently, there is no care option in Ghana that is available specifically for persons living with dementia. Due to this, they are forced to settle with four major care options, which includes mental or geriatric health facilities, nurses and care takers, elderly care homes and NGOs related to the ageing or persons living with dementia. This lack of personnel and facilities can, however, present as a threat to the optimisation of care that persons living with dementia require as lack of care options presented as the major challenge faced specifically in the form of resources. This included both personnel and facilities. However, it was identified that, by planning for the ageing, some of these issues can be mitigated. This can be achieved through the design of a more dementia and ageing friendly environment, planning in terms of conditions typically associated with old age and the training of specialised doctors or nurses to help provide optimal care for these individuals, which were all areas that were uncovered by the data collection of this study.

3.1.1. Misconceptions about dementia and dementia Care in Ghana

3.1.1.1. Theme 1: Lack of Knowledge

According to, HE 1, Ghanaians know that people lose their memory but cannot explicitly say that these symptoms are specifically related to dementia. She reveals that family members can tell when their relatives start losing their memory, however, the majority of them feel their family members are lying due to the implications of the condition, which includes short-term memory loss and long-term memory retention. This perception of persons living with dementia putting on a show or intentionally behaving in a certain way was backed by many individuals who took part in the study, including both respondents from the two NGOs and Madam MKn. Unfortunately, Mrs. GBw, who believed her relative was also lying when the symptoms started showing up, stated that if she knew that those were the symptoms of dementia, she and her family would have been able to provide better care for their relative before he passed. Unfortunately, this is the plight for many who have relatives with this condition, with findings revealing that lack of knowledge was a major misconception and ranked the highest by all participants. Similarly, the relation of the condition to the normal progression of ageing as well as beliefs that persons living with dementia were pretending were among the other misconceptions held, according to findings from the study.

3.1.1.2. Theme 2: Relation to Old Age

With the two major areas of misconceptions being the general lack of knowledge and relation to old age, it is clear that not enough is being done to educate the public on dementia. The high occurrence of the notion that dementia is also related to old age is damaging to not only persons living with dementia but also the relatives because it prevents relatives of these individuals from seeking the necessary care even if they recognise certain symptoms. This was confirmed by both HE 2 and Mrs. GBw.

HE 2, who also works at three other health facilities stated insistently that, dementia is a condition. He revealed that it may sound obvious, but many people do not acknowledge the symptoms in their relatives when they first start showing up. He continued saying that,

We see persons living with dementia late because when people bring their relations with dementia and you go into the history, you find that it started with forgetfulness maybe three, four, five years ago. Which they noticed alright. But even when the person goes out sometimes and get lost, and they bring them back, they still do not think that it is a problem.

He also expressed that many people in our society tend to believe that forgetfulness is almost invariable when you are old. In his work with many individuals over the past 30 years, he mentioned that in his encounters with some relatives, dismissal of the symptoms was typical. He revealed that,

They (relatives) will say that oh she had been alright, it is just the usual old age kind of thing. And when you point out these things to them, they will tell you that ‘oh yes, we noticed it, but we thought it was part of ageing’. So, they do recognise the symptoms, but they do not put it down to a condition. But you just need to think of the fact that there are 95 year olds, who are strong, who can remember the details of everything they did yesterday as well as 50 years ago and who are very active because they do not have dementia.

Additionally, HE 3, a psychiatrist at a private clinic also shared that Ghanaians believe that the condition is associated with old age, which is again is not necessarily true. HE 3 went on to say that, due to this misconception, when people start noticing or complaining about something, they just say it is old age.

This was again experienced by Mrs. GBw who was told by a doctor that her relatives’ condition was associated with old age. This goes to show that the misinformation in Ghanaian society is in fact imminent and is causing distress in families as they are not able to handle the condition and these persons appropriately.

However, NGOF 1, stated that his organisation does well to educate not only the public but also the family members and people living in the same house as persons living with dementia, to help address issues such as those stated above. He indicated that some people also believe that dementia is associated with menopause, which is not the case. Additionally, in his years of experience with these individuals, he has come across that,

They are also perceived as people who are mad, so they lump them up with people who are suffering from psychosis, psychiatric patients. But they are not psychiatric patients, and they are given treatment like psychiatric patients, which should not be the case. They send them to the mental hospitals. Some of them are locked up in their homes and are not allowed to come out because they are going to be misbehaving.

From speaking to the organisations and health experts, findings have revealed that providing the necessary care and support system is imperative to help deal with some of these issues associated with the misconceptions. This is especially important because with the lack of proper care, the caretakers and family members become frustrated and that is when the abuse to persons living with dementia begins.

3.1.2. Societal Perceptions of Dementia and Dementia Care in Ghana

3.1.2.1. Theme 1: Dismissal

For HE 1, she does not believe that the Ghanaian society has recognised dementia as a societal problem. She explained saying that it is not something people talk about, and it is exceedingly difficult to take these individuals out. The data from the interviews from other professionals show clearly there is a consensus on this, with majority of respondents agreeing that the association with witchcraft is a key societal perception. Public doubt of the condition itself was also a key finding from the dismissal theme.

3.1.2.2. Theme 2: Cultural Beliefs

According to NGOF 2, generally the Ghanaian society views persons living with dementia with a lot of misconception, misunderstanding and misinformation. NGOF 2 stated that,

Unfortunately, if they are women, people will use all sorts of superstitious cultural beliefs about witchcraft. Or we may look at dementia as a curse, a sign of a curse, where you have basically lost your connection to the living.

These superstitious cultural beliefs, which associate dementia with witchcraft in Ghana, was also supported by NGOF 1 who stated that the incident that happened in 2009 with an elderly woman being burned alive due to the condition was what accelerated the formation of the organisation. He elaborated that at the time of the formation,

Some of them were also perceived as being witches and wizards because of the nature of the signs and symptoms of the condition. So, a lot of them were put in enclosures, some murdered, some excluded completely from the society because of their behaviours.

Despite these perceptions, it is believed that slowly, there is a little more education and a little more exposure within the last five years. However, this education is more prevalent within the middle class, exposed and more educated society, especially as we are seeing more and more of it.

3.1.3. Challenges with dementia and dementia Care in Ghana

3.1.3.1. Theme 1: Lack of human resources: According to NGOF 2

One extremely important one is caregivers. Providing caregivers with information. In a lot of our homes and families, we find family members, or housekeepers, house helps to come in and help with seniors who have zero training. Zero understanding in these things. So, this is where abuse also comes in, where people get abused. Seniors who have dementia, abused by caregivers who are frustrated and unable to process it and do not understand how to process it.

These sentiments are supported by the majority of the major stakeholders who were contacted for the study. The lack of human resources theme comprised areas that were consistent with the responses of NGOF 2 including the unavailability of time of relatives and the demanding nature of the condition.

HE 1 for instance pointed out that,

Biggest thing is human resource. For many, their children are outside the country and for those living in Ghana, they are not living with their parents. Their own family members are not present. It is also very demanding to care for these individuals and you would have to stop work to make time for them.

NGOF 1 also confirmed this pointing out that,

We also do not have specialised doctors and nurses trained in this area. Because you go to the nursing and health care providing institutions in the country and dementia is not part of it. The care for dementia, the treatment of dementia, is not part of it. It is just something that is given to them in one sentence or two. And so, there is little concentration in this area by professionals.

3.1.3.2. Theme 2: Financial implications

On the issue of finance, NGOF 1 pointed out that the families of these individuals get stressed out when a relative is diagnosed with dementia because it takes a negative toll on their finances, aside from the devotion of all their time to caring for these individuals. He continued saying that this challenge is especially crippling because,

Unfortunately, there is no policy in place to support people who are suffering from the disease or their families in the country. There is no benefit that is provided to them and so they cater for it on their own.

3.1.3.3. Theme 3: Lack of Knowledge

NGOF 1 stated that persons living with dementia in Ghana are strongly stigmatized, which does not benefit them in any way. In terms of care options, HE 1 indicated that there are no care options specifically for dementia in Ghana, and for NGOF 1, this was another challenge. He pointed out that, the care home concept has not been developed in Ghana specifically for dementia, although there are elderly care homes present in Ghana.

3.1.3.4. Theme 4: Lack of Care for the Ageing

HE 3 indicated that generally, in terms of elderly care, not much has been put in place to cater to their needs. He also continued saying that there is no real plan for the investments needed in our health care for the elderly, and this is due to the structure of our health care and insurance system. Unfortunately, according to him, dementia thus suffers from this shortfall.

Along with the general societal negligence of the elderly in Ghana, HE 2 and NGOF 2 expressed that generally our built environment does little in terms of design to help these individuals. NGOF 2 for instance expressed that,

Generally, our built environment does not take into consideration seniors. We build for young energetic people, and one of the things that is missing, is in the latter years, remodelling of homes.

3.1.4. Strategies to mitigate imminent challenges

3.1.4.1. Theme 1: Knowledge about the Condition

Stakeholders from this study have stressed the importance of knowledge and education in mitigating some of the challenges present. NGOF 2 believed that this was the way forward, stating that, public discourse, awareness, and the provision of general information can go a long way to help elderly who may develop the condition later in life. She elaborated that in her years of practise and work with the ageing, she has come across of number of seniors who panic when they forget something, so for her, it important to normalise the condition and help seniors understand that it may or may not happen to them, and if it does, there are support systems in place, through organisations such as hers, which provides psychosocial support to these individuals.

3.1.4.2. Theme 2: Planning for the Ageing

From the study, the training of specialised doctors and nurses was shown to be the most relevant strategy when it came to planning for the elderly. The provision of facilities such as day care was seen to be the least recommended strategy and can be linked to the outcomes of studies regarding the perceptions of Ghanaian society on the topic of elderly care homes. However, other feasible strategies included planning in relation to the ageing in society by designing a more friendly environment for individuals who are ageing.

3.1.4.3. Theme 3: Provision of Support

For NGOF 1, apart from awareness, he also stated that advocacy was equally important. For him, care that will centre around these individuals also played a major role in improving the quality of life of these persons. Additionally, the lack of person-centred care that was available in the western world but not in Ghana, was another determinant for the formation of the organisation. Their organisation thus serves as medium to connect family members to health care providers.

HE 1 indicated that giving the family a break can also help, by providing a day care unit or specialised staff. She elaborated that due to their condition you need to have patience to listen to them. She also mentioned that the assisted living concept that is currently available in countries like the United States of America could help. She continued saying that for institutions or facilities like that, they do not only care for you, but also there are many things to do.

3.1.5. Living with Persons living with dementia in Ghana

It is a known fact that dementia shows up differently in various individuals, and interestingly, even with the relatively small sample size of respondents representing family members of persons living with dementia, no two situations were entirely the same when it came to behavioural symptoms. Many of the persons living with dementia, lived at home and their daily lives typically consisted of activities that were scheduled in between mealtimes. These activities included a range of social, physical, and psychological activities to help keep their body and mind active. Social activities typically included interactions of various forms and the most common form of recreation was watching of television, for those who still had their vision. For relatives caring for persons living with dementia, the toll on the family played a major role in the challenges associated with care. Some of these included challenges relating to lack of human resources, financial implications, issues with communication, lack of knowledge and understanding of the condition as well as general lack of ageing care available. However, financial implications were experienced by all persons associated with persons living with dementia.

3.1.6. Dementia and quality of life

Behavioural symptoms obtained for each respondent were different. The symptoms identified included, memory loss, hallucinations, aggression (verbal and physical), agitation, wandering, delusions, rejection of care, shadowing, and sun-down syndrome.

Recreational activities typically included watching television, walking, listening to the radio or hymns, religious activities, going out and gardening. The most common social activities however included interactions of various forms such as going out with friends, visits from family and friends and the engagement in conversations with others.

For numerous people in Ghana, the indications of dementia, such as, being absent-minded are the unimportant impacts of mature age. This was experienced by Mrs. GBw, who stated that,

From the word go, we begun to have prayer meetings. It was prayer, prayer, because we were thinking that it was an attack. So, we had to take him to a doctor. The doctor did not really give us anything, he said it was old age. He was like why were we bothering ourselves with all this. He was a general doctor. It was the doctor who was seeing to him at the time (not a specialist). He used to see him for review and all that. Like I was saying they all said it was old age. They did not really have anything. They were looking at his age. They felt that it was just old age and that it was just a certain aspect to it.

She however expressed that,

It was when he passed on that we realised that the dementia, we could have handled it better. If we knew all the symptoms very well, I think we would have handled it properly.

Mr. JSo also shared his sentiments stating that,

What I realised is that when we were young, all those they were saying about someone being a witch, I was thinking that was dementia then. But we did not know about it. So, people were wrongly being accused of witchcraft and all those things and we never knew about it. Because even at her age, if I go and tell her that she killed this person and I start beating her with a stick, she will definitely say that yes, she did it. Because if you go to the northern part of Ghana, people are being beaten to accept that they are witches. It is dementia and other conditions that were affecting people, and we did not know.

Unfortunately, in Ghana, this is the plight of many persons not only living with dementia, but also family members who are unaware of the implications of the condition. Due to the various beliefs and cultural systems in place in the country, a lot of persons living with dementia are not given the adequate care they need and thus their quality of life dwindles. Despite this, Ghanaians, are however, still not in favour of taking their elderly family members to homes, despite the break in the traditional care process.

Mrs. SBh expressed this concern stating that, although people frown at the fact that her mother is in a care home, for her, the benefits outweigh the risks. She expressed that she is glad she can give her mother the 24/7 specialised care she requires, as the care home meets her most important needs, which includes being fed three times a day and being completely safe. For her,

The fear of losing her by her wandering off was paramount. So, her being in the care home I know she is safe and cannot leave because there are keypads on the doors and there are cameras everywhere so at least she is being monitored all the time.

She also believes that the lack of specialised care in Ghana for persons living with dementia is a major challenge for individuals living with the condition which was confirmed by the findings in this study. Madam D-NAh, also echoed this by stating that in her opinion,

Care options is the big challenge. Because there is little to no information on dementia generally. I do not think dementia is something that a lot of Ghanaians know about. Or even if they know about it, I do not think it is something that a lot of Ghanaians know about or understand. So, some people do not even know how to react to persons living with dementia. Some people just say oh it is old age. That is if the person is old. But if it happens to be early onset dementia, a lot of people will just call it madness and leave it at that.

Creation of awareness through education of the public was also believed to help improve the quality of life of these individuals. It is however important to note that aside the effects of the condition on persons living with dementia, the care takers and family members also experience a drastic lifestyle change when their relatives are diagnosed. Mr. JSo expressed that,

You will see her talking to herself and she is enjoying the conversation but you who is with her, you do not see whoever she is talking to. It is her mind that is controlling her now. It is not easy living with them. They are in their own world. Sometimes she is like a kid. If you do not tell her eat, she will not eat. If you do not tell her to bath, she will not bath. You have to give her the necessary instructions. Sometimes in the night, I have to go to her room and tell her to sleep. Because if you do not go and tell her to sleep, she will not sleep. She is sitting down and talking. You have to go and tell her that it is late, go to sleep.

3.2. Translating concepts of quality of life into architecture

3.2.1. Adaptations of Living Spaces for Persons Living with dementia who stay at home

From the interviews conducted with the family members and caretakers of persons living with dementia in Ghana, findings revealed that majority of these individuals stayed at home. This was expected based on the lack of specialised care available in the country, the need for maintenance of familiarity for these individuals, as well as the contextual perspective and thus relatives resorted to home modifications.

These were categorised into three major themes, namely fittings and fixtures, spatial configuration, and safety features. It is also crucial to note that, all changes that were made in the home were based on the person living with dementia-specific needs reiterating the concept of person-centred care and its relevance in designing for persons living with dementia. Some home modifications family members adapted included addition of a bath seat, use of raised toilet seats, inclusion of specialised chairs and automated beds. There were also general spatial changes including switching of rooms and the inclusion safety features such as handrails, provision of an automated bed, clearing the floor area to allow the space to be obstruction free to prevent trips and falls, and the securing of carpet edges. Consequently, at one point or another, majority of the relatives of persons living with dementia needed to make some changes in their homes either for safety reasons or just to help their relatives living with dementia feel a little more comfortable in their day-to-day activity.

Notably, one major home alteration that was observed was the changing of bathtubs to a walk-in shower or providing a seat in the bath. Many of the persons living with dementia who were included in the study, required some help when bathing and so for their families, making this switch came in very handy. For family members living in a storey building who could not necessarily provide for their relatives to stay on the ground floor, addition of handrails on the staircase was a must. The use of a raised toilet seat, changing of tiles and inclusion of a living room by closing off a porch, among other things were other modifications that were made.

3.2.2. Challenges with the Current environment

Some challenges with the current environment included lack of accessibility, exclusion of religious activities and surveillance. Some strategies that were stated to improve current environment included maintenance of individuals’ culture or tradition, easy identification of pathways and doors, and provision of safer walking spaces. Generally, when it came to challenges with dementia care in Ghana, lack of knowledge, lack of specialised care options and cost of care were imminent. Strategies to mitigate these challenges to included education, provision of specialised care and subsidising care costs. However, when it came to caring for these individuals, the major challenge was the toll on the family, which included emotional strain, negative financial impact, altering of normal daily routine, time needed for constant care and rejection of care such as feeding, bathing, etc.

3.2.3. Elderly care homes in Ghana as an alternative care option

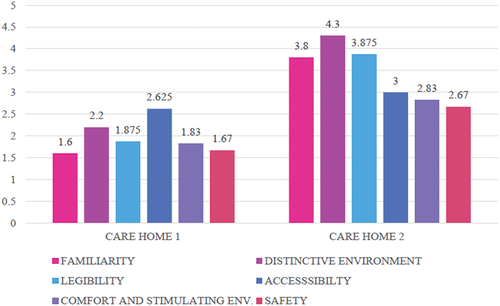

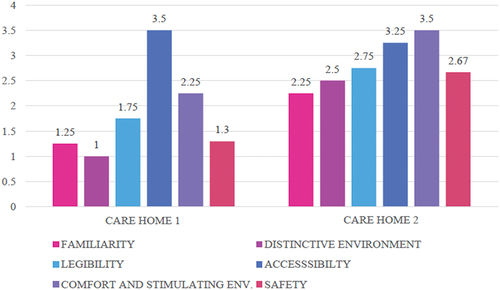

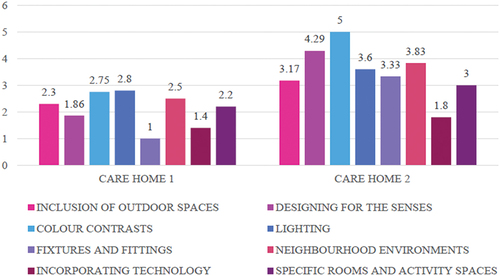

Each of the care homes visited had accommodation consisting of two to three persons per room. The main challenges associated with care for persons living with dementia included communication in diverse forms, from trying to get them to perform certain tasks to ensuring that these individuals do not feel disrespected due to the culture dimension regarding sequential age in Ghana. Their routines were likened that of those who lived at home, and activities also included both physical and cognitive training. From the spatial configurations presented in , there are clear issues with these care homes in relation to persons living with dementia. This includes lack of personalised spaces, absence of identifiable pieces from previous life, no use of tactile stimulation artwork, absence of technology among many other design issues as can be seen in the graphs presented in , and . This is important as the physical environment plays a pivotal role in helping persons living with dementia cope better with the condition and so once the fundamentals are missing, it becomes challenging for them.

Figure 5. Graphical representation for values for principles of dementia friendly design assessment (Indoors).

Figure 6. Graphical representation for values for principles of dementia friendly design assessment (Outdoors).

Figure 7. Graphical representation for values for contemporary trends of dementia friendly design Assessment.

When reviewed against the principles of dementia friendly design, the care homes were observed to meet some of the principles. From the assessment, the second care home had better results overall with key areas being the principles of familiarity, distinctive environments, and legibility and this was mainly due to their predominant use of colour contrasts and signage. However, both care homes lacked when it came to safety and comfort and stimulating environment when assessed against the principles of dementia friendly design due to the absence of tactile markings, the absence of sound absorbing materials, unambiguity of restricted areas and the lack of use of SMART technology.

Unfortunately, the outdoor environment was more deficient as compared to the indoor environment for both care homes. Both care homes had significantly low ratings in areas of familiarity, distinctive environments, and safety, although the second had slightly greater scores. The best ratings were however seen in accessibility of the outdoor space for both care homes.

When it came to the adoption of contemporary trends of dementia friendly design, fixtures and fittings was ranked lowest for the first care home while specific rooms and activity spaces was ranked lowest for the second care home. Overall incorporation of technology was low for both homes. This was due to the absence of multi-sensory rooms, no use of assistive technology or memory boxes.

Although these care homes are not specifically designed for persons living with dementia, dementia is a condition that is more prevalent in individuals who are ageing, and so it is important that in the design of these homes, especially as an alternative care option, special attention is paid to certain areas, to ensure that these individuals can live a good quality of life.

3.2.4. Experts’ approach to designing for dementia

From the data collected, it was realised that home modifications in Ghana were difficult due to the construction culture in Ghana and the predominant use of concrete. This makes it difficult for homes to be modified as an individual ages or develops certain symptoms causing major issues for the elderly later in life, which reveals another reason for the importance of this study.

HE 1 expressed that,

Home modifications are difficult in Ghana due to the construction culture and the predominant use of concrete, making it difficult for homes to be modified as individuals age or develop certain symptoms.

To help impede this strain, the use of one-level units, removal of steps and replacement with ramps and rails were encouraged to help connect spaces, especially in the bathroom as persons living with dementia may not remember to take their walker.

HE 2 also shared that,

Safety was of utmost importance because for me, the deficits that persons living with dementia suffer invariably, are the things that can be potentially life threatening.

He therefore suggested that the basic things should be a priority. This includes, water, fire, electricity, among other things. He also suggested the use of automation as some persons living with dementia may forget to do certain things such as close the tap after using it or flushing the toilet, as their understanding of processes virtually diminishes.

Additionally, prominence was placed on the fact that dementia is specific and presents itself differently in different individuals. Thus, experts emphasised the importance of design strategies being employed to suit the individual’s needs. By utilising technology in the form of automation, basic things would be catered for. This in turn reduces the impact of their cognitive decline and allows them to maintain their independence for a longer period.

Additionally, labelling of spaces to help with orientation, the addition of greenery or encouraging them to spend more time outside were all proposals made by health experts to persons living with dementia to help improve their quality of life. HE 4 expressed that,

When persons living with dementia are in their usual environment, they do better, they thrive better. They lessen their chances of missing their way around which is one of the symptoms in dementia. Additionally, in very calm environments it also helps them to settle down and reduce their chances of getting agitated.

Similarly, NGOF 1 advocated strongly for person centred care, expressing that his organisation provided help based on the individual. In terms of architecture, he elaborated that because persons living with dementia tend to remember past events, architectural design that is of their time is important to keep them going. He also believed that the use of simple layouts would be easily understood by them.

For IDE 1, persons living with dementia need spaces that offer and support the feeling of security. She explained that attributes such as clear and easy wayfinding, simple orientation, safe and well-organized moving spaces, good lighting, clear arrangements, barrier-free spaces, comfortable and pleasant atmospheres, supportive assistive technologies, and devices can go a long way to benefit these individuals. She expressed the need for qualified staff with the awareness that not being able to articulate does not mean persons living with dementia do not have wishes.

For home modifications, redesigning of the spaces to suit a person in a wheelchair was imperative. Redesigning of bathrooms according to barrier-free requirements and the removal of all obstacles, which might be dangerous, such as carpets was a necessity. Additionally, by offering views to the outside, these individuals can live a more normalised lifestyle. For many of the respondents, the presence of recreational facilities or sporting activities, tailored to their age was imperative. Additionally, any type of recreation that will help them exercise their brain and a space for stay-in caregivers was encouraged.

4. Discussions

4.1. Current state of demetia care in Ghana

The study revealed that, the current state of dementia care, were consistent with literature in terms of, misconceptions about dementia and dementia care in Ghana (Spittel et al., Citation2018), societal perceptions about dementia (Smith, Citation2010; Spittel et al., Citation2018; Spittel et al., Citation2019), care options available for persons living with dementia in Ghana (Aboderin, Citation2004; Akinny, Citation2016; N. Apt, Citation2002; N. A. Apt, Citation2001; Dovie, Citation2019), challenges with dementia and dementia care (Dey, Citation2017; Dovie, Citation2019; Spittel, Citation2014; Spittel et al., Citation2018), and strategies to mitigate imminent challenges (Dovie, Citation2019; Smalls-Mantey, Citation2019; Spittel et al., Citation2018).

In line with research by Ohene (Citation2016), the general misconception, as demonstrated by the study, is that the condition is related to old age, and is mainly viewed as a normal part of ageing which is not the case. Consequently, numerous research (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021; Irwin et al., Citation2018; National Institute on Aging, Citation2020; WHO, Citation2021) have stated emphatically that dementia is not a normal part of ageing.

In Ghana, the condition was also linked to many cultural and superstitious beliefs including witchcraft, which was revealed in a study by Agyeman et al. Citation(2019) and Spittel et al. Citation(2019). Cultural beliefs were discussed by over half of the participants as a challenge to the quality of life for persons living with dementia, with associations between dementia and witchcraft identified by several participants. This finding has also been observed in similar studies (Brooke & Ojo, Citation2019; Spittel, Citation2014). The general misconceptions and misinformation as substantiated by studies including WHO Citation(2015) and Nyame et al. Citation(2019) was also a key finding in the research.

In Smalls-Mantey Citation(2019) study, the lack of personnel and facilities was discussed, and this presents a threat to the optimisation of care that persons living with dementia require as can be seen in the care options available in Ghana (Appiah, Citation2017). Generally, Roberts et al. Citation(2014) highlighted that issues of care for persons living with dementia basically emerge from the absence of information on the disease and absence of mental facilities in Ghana, which was clearly observed in the theme lack of knowledge that was discussed by over half of the participants.

In terms of the impact of dementia, WHO Citation(2021) also highlights that the load on carers can also be extraneous thus supporting the findings from the study. NGOF 2 confirms this statement by explaining that the unavailability of time of relatives and the demanding nature of the condition makes it difficult to find suitable care for persons living with dementia. This leads to worry at the diagnosis of dementia because it takes a negative toll on the family’s finances, aside from the devotion of all their time to caring for these individuals (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2003; Sörensen & Conwell, Citation2011; WHO, Citation2021).

Similarly, for the life of an individual living with dementia in Ghana, findings were in line with behavioural symptoms (Steele et al., Citation1990), types of social Activities (O’Sullivan, Citation2008; Piot, Citation2015), challenges with social activities (Algase et al., Citation2007), types of recreational activities (Day et al., Citation2000; Fleming et al., Citation2008; Gitlin et al., Citation2003), and home modifications (Fleming & Sum, Citation2014; social care institute for excellence, Citation2019).

It is a known fact that dementia shows up differently in various individuals (Barrett et al., Citation2018; Dementia Australia, Citation2016), and interestingly, even with the relatively small sample size of respondents who gave their perspectives on the life of a person living with dementia, no two situations were entirely the same when it came to behavioural symptoms. Just like Hyde Citation(2012), stated many of the persons living with dementia, lived at home, which was a similar situation in Ghana. This phenomenon was also contextual as Akinny Citation(2016) through a study discovered that Ghanaians, are do not fully accept the concept of care homes, despite the break in the traditional care process and growing demand for them in light of shifting cultural and social dynamics. In line with findings by WHO Citation(2020), which expressed that ‘Physical, emotional, and financial pressures can also cause great stress to families and carers, and support is required from the health, social, financial and legal systems’, respondents included in the study confirmed the varying dynamics associated with care for persons living with dementia. Additionally, majority of the health care experts pushed for person-centered care as stipulated by Kitwood and Bredin (Citation1991), which was later developed by CitationBrooker (Citation2003). Generally, modifications made in the home environments of persons living with dementia were also made specifically in relation to their specific needs which helped to reiterate the importance of individual care for persons living with dementia.

4.2. Dementia and design

When it came to dementia and design, home modifications were a key aspect of the lives of persons living with dementia. Both experts in the field and relatives of these individuals supported the idea of spatial changes to not only make persons living with dementia feel comfortable but also to help them cope better with the disease. There was a consensus on the benefits of certain design implications for persons living with dementia, as can be seen by design guides such as Halsall and MacDonald Citation(2015), Fleming et al. Citation(2017), Alzheimers Disease International Citation2020 among others, however, there was nothing concrete to help family members interested in considering this approach to long-term care for their relatives. Instead, changes were made as an when needed to suit the needs of the person in question which again demonstrates the essence of the research by Kitwood and Bredin Citation(1991). The changes were made to make their lives more comfortable and not necessarily as a strategy to follow specific guidelines. Similarly, when it came to the elderly care homes, there was a general attempt to include certain aspects of design that made movement and living easier for the residents. However, as with the private residences, there was nothing definitive and key elements such as personalisation and independence were not principles that were strongly adhered to.

While there may be the argument that the care home concept has not been developed in Ghana specifically for dementia, there are residential care homes present in Ghana, which has been revealed in detail in the study by Dovie Citation(2019). Additionally, the idea that the concept is not accepted by Ghanaians as presented by Akinny Citation(2016) is quickly shifting and with the current cultural and societal dynamics, combined with the decreased birth and mortality rates, as well as enhanced health care. Lack of care or provision for the ageing in society is therefore quickly becoming a problem. It is therefore imperative to make provisions for alternative care options through the design of ageing friendly architecture not only within institutionalised settings like care homes but also for private residences.

As Dovie Citation(2019) stated, care homes in Ghana are not an area that is patronised due to stigma and finances. However, the lack of affluency should not be a determinant of a comfortable life for persons living with dementia especially when welfare alternatives that cater to their well-being are scarce. Additionally, for the care homes that are available in Ghana, and are within reach for those within the middle to high classes, adoption of dementia friendly principles is low.

Fortunately, findings from the study demonstrated that that family members of persons living with dementia are knowledgeable about the implications of design and are willing to explore alternative care options if they are within reach and available to them. This thus gives the opportunity to explore design as an alternative care option especially given the contextual dynamics of the findings. Many respondents expressed their desire to do more if they knew more, revealing that it was necessary to provide support for persons living with dementia and their relatives.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Current state of dementia in Ghana

The current state of dementia care in Ghana is characterised by a great deal of misconception, misunderstanding and misinformation and education through awareness, advocacy and training can go a long way to help mitigate some of these challenges. There are currently no welfare packages specifically for persons living with dementia leaving them as well as their relatives to settle for care in the form of mental or geriatric health facilities, nurses and care takers, elderly care homes and NGOs related to the ageing or persons living with dementia all of which are scarce. Additionally, limited resources in terms of not only facilities but also personnel make it incredibly difficult for interested persons to get the necessary help they require. Unfortunately, in Ghana the exploration and adoption of design as an alternative care option to improve the livelihoods for persons living with dementia is understudied, but not unknown. This indicates that there could be an opportunity to explore the subject to add to the options that these individuals can adopt.

5.2. Design approaches to dementia

Relatives of persons living with dementia typically addressed design issues based on the developing behavioural symptoms. The findings indicated that, planning for dementia, the provision of support and the availability of specialised care are important. Additionally, health experts are aware of the tools and design modifications needed when it came to persons living with dementia, however, they can only make assertions based on their experience from the health perspective. Due to the absence of a set design framework to help these family members address these issues directly, modifications adopted may not necessarily maximise results. There is an opportunity therefore, through the translation of quality of life into some design frameworks for dementia friendly design, to improve or maintain the quality of life of persons living with dementia in both private residences and care homes.

5.3. The future of dementia and design

From the findings, certain areas were observed to be neglected when it came to dementia and design in Ghana. Although the concepts of home modifications and design considerations were not novel, guidance is needed in providing specific design solutions. Consequently, through the provision of a comprehensive design framework to help individuals who may be looking to design dementia friendly spaces, individuals will have a step-by-step guide to implementing design strategies that can help improve the livelihoods of their relatives with dementia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly. Secondly, due to the sensitive nature of the research data is not available.

References

- Aboderin, I. (2004). Decline material family support for older people in urban Ghana, africa: Under-standing processes and causes of change. Gerontology: Social Sciences, 59B(3), S128–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.3.s128

- Agyeman, N. (2019). The prevalence and socio-cultural features of dementia among older people in rural Ghana, Kintampo, Health Service & Population Research, Student Doctoral Thesis, Kings College London, Online, Available at: https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/studentTheses/the-prevalence-and-socio-cultural-features-of-dementia-among-olde (Accessed on 5 January 2020)

- Agyeman, N., Guerchet, M., Nyame, S., Tawiah, C., Owusu-Agyei, S., Prince, M. J., & Mayston, R. (2019). “When someone becomes old then every part of the body too becomes old”: Experiences of living with dementia in Kintampo, rural Ghana. Transcultural Psychiatry, 56(5), 895–917. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519847054

- Akinny, W. (2016). Investigating the desirability and feasibility of the ‘Old People’s home’ as a viable business in Ghana. Ashesi University College. Retrieved November 30, 2020. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Investigating-the-desirability-and-feasibility-of-a-Akinny/59fddb39feb934378890c893469f61f1a4d44fb0

- Algase, D., Helen Moore, D., Vandeweerd, C., & Gavin-Dreschnack, D. (2007). Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging & Mental Health, 11(6), 686–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860701366434

- Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Association, Ghana (ADRAG), (2016) Research. Retrieved October 30, 2020. https://alzheimersgh.org/research/

- Alzheimers Disease International. (2020). World Alzheimer Report 2020, design, dignity, dementia: Dementia-related design and the built environment. 1. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2020Vol1.pdf

- Alzheimers Society. (2021). Staying independent. Retrieved March 11, 2022. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/staying-independent

- Andersen, C. K., Wittrup-Jensen, K. U., Lolk, A., Andersen, K., & Kragh-Sørensen, P. (2004). Ability to perform activities of daily living is the main factor affecting quality of life in patients with dementia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-52

- Appiah, D. (2017). Dementia in Ghana: Care options available and how technology can be used to publicize them. Retrieved January 8, 2020. https://air.ashesi.edu.gh/items/b40dc92d-756e-4f75-ace1-b2ea9085efe5

- Apt, N. (2002). Ageing and the changing role of the family and the community: An African perspective. International Social Security Review, 55(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-246X.00113

- Apt, N. A. (2001). Rapid Urbanisation and Living Arrangements of Older Persons in Africa. United Nations Population Bulletin, ( Special Issue, (Special Issue Nos. 42/43)). 1–30. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_egm_200002_apt.pdf

- Arksey, H., & Knight, P. (1999). Interviewing for social scientists. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209335

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Dementia in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/199796bc-34bf-4c49-a046-7e83c24968f1/13995.pdf?v=20230605142904&inline=true

- Ayisi-Boateng, N. K., Opoku, D. A., Tawiah, P., Owusu-Antwi, R., Konadu, E., Apenteng, G. T., Essuman, A., Mock, C., Barnie, B., Donkor, P., & Sarfo, F. S. (2022). Carers’ needs assessment for patients with dementia in Ghana. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 14(1), e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3595

- Barrett, P., Sharma, M., & Zeisel, J. (2018). Optimal spaces for those living with dementia: Principles and evidence. Building Research & Information, 47(6), 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2018.1489473

- Batsch, N. L., & Mittelman, M. S. (2012). World alzheimer report 2012: Overcoming the stigma of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Beck, C. K. (1998). Psychosocial and behavioral interventions for Alzheimer’s disease patients and their families. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 6(2 Suppl), S41–S48. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-199821001-00006

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brooke, J., & Ojo, O. (2019). Contemporary views on dementia as witchcraft in sub‐Saharan africa: A systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(1–2), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15066

- Brooker, D. (2003). What is person-centred care in dementia? Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 13(3), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095925980400108X

- CADTH. (2018). ‘Dementia villages: Innovative residential care for people with dementia’, online. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/dementia-villages-innovative-residential-care-people-dementia (Accessd on 25 November 2023)

- Caffò, A. O., Hoogeveen, F., Groenendaal, M., Perilli, A. V., Picucci, L., Lancioni, G. E., & Bosco, A. (2013). Intervention strategies for spatial orientation disorders in dementia: A selective review. Developmental neurorehabilitation, 17(3), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2012.749951

- Caulfield, J. (2019). How to do thematic analysis. Step-by-Step Guide & Examples, Scribbr. Retrieved February 2, 2021. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/#:~:text=Thematic%20analysis%20allows%20you%20a,sorting%20them%20into%20broad%20themes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). The truth about aging and dementia online. Retrieved October 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/publications/features/dementia-not-normal-aging.html

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. (2001). Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: A review, summary, and critique. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 9(4), 361–381. https://doi.org/10.1176/foc.2.2.288

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications.

- Dai, B., Larnyo, E., Tetteh, E., Aboagye, A. K., & I, M.-A.-A. (2020). Factors affecting caregivers’ acceptance of the use of wearable devices by patients with dementia: An extension of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 35(4), 153331751988349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317519883493

- Day, K., Carreon, D., & Stump, C. (2000). The therapeutic design of environments for people with dementia: A review of the empirical research. The Gerontologist, 40(4), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/40.4.397

- Daykin, N., Byrne, E., Soteriou, T., & O’Connor, S. (2008). The impact of art, design and environment in mental healthcare: A systematic review of the literature. Royal Society of Health Journal, 128(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424007087806

- De Langavant, L. C., Bayen, E., Bachoud-Lévi, A. C., & Yaffe, K. (2020). Approximating dementia prevalence in population‐based surveys of aging worldwide: An unsupervised machine learning approach. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 6(1), e12074. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12074

- Dementia Australia. (2016). How to design dementia-friendly care environments online. Retrieved November 1, 2020. https://www.dementia.org.au/files/helpsheets/Helpsheet-Environment03_HowToDesign_english.pdf

- Dey, E. (2017). Dementia in Ghana: care options available and how technology can be used to publicize them (D.-N. Appiah, interviewer), Student Thesis, Afribrary, Online. Available at: https://afribary.com/works/dementia-in-ghana-care-options-available-and-how-technology-can-be-used-to-publicize-them (Accessed on 3 July 2021)

- Dovie, D. A. (2019). The status of older adult care in contemporary Ghana: A profile of some emerging issues. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00025

- Dreyer, J., Bergmann, J. M., Köhler, K., Hochgraeber, I., Pinkert, C., Roes, M., Thyrian, J. R., Wiegelmann, H., Holle, B. (2022). Differences and commonalities of home-based care arrangements for persons living with dementia in Germany – a theory-driven development of types using multiple correspondence analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 723. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03310-1

- Duggan, S., Blackman, T., Martyr, A., & Van Schaik, P. (2008). The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: A “shrinking world”? Dementia (London, England), 7(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301208091158

- Engedal, K., & Haugen, P. (2018). “To be, or not to be”: Experiencing deterioration among people with young-onset dementia living alone. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 1490620. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1490620

- Fleming, R., Bennett, K. A., Preece, T., & Phillipson, L. (2017). The development and testing of the dementia friendly communities environment assessment tool (DFC EAT). International Psychogeriatrics / IPA, 29(2), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001678