ABSTRACT

Purpose

The National TeleOncology Service (NTO) is a clinical service that enables VA oncologists, from across the country, to provide services via telehealth to Veterans with cancer. We sought to understand the early experiences of medical oncologists, Veterans, and clinical staff to inform the national NTO scale–out.

Materials and methods

We recruited clinicians who provided and/or Veterans who received care from three early adopting NTO sites. We purposively sampled Veteran participants who were: (1) diagnosed and/or treated December 2016 – March 2021 with prostate, non-small cell lung, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, or colorectal cancer as confirmed by ICD–10 codes, and (2) obtained NTO-delivered care in October 2016 through July 2022 at one of the included NTO sites. We used rapid qualitative analysis.

Results

We conducted 3 provider focus groups and interviewed 15 Veterans. Participants noted the relative advantage of NTO over in-person care. A primary advantage of NTO is that it facilitates access to oncology specialists for Veterans who travel long distances. Clinicians and Veteran participants agreed that NTO service facilitates access to specialists for Veterans living far from VA medical facilities and community care and in areas lacking specialty oncologists. Although clinicians and Veteran participants agreed that NTO largely meets patient needs, some noted that NTO may not be personable.

Conclusion

There was consensus among clinicians that the NTO service, with its focus on specialized and individualized oncology care and increased access to care for patients through the virtual platform, is working well to meet the needs of Veterans with cancer.

Introduction

In the US there has been a significant increase in telehealth use. In 2020 telehealth use accounted for nearly 25% of all health care encounters [Citation1]. While the COVID-19 pandemic spurred a dramatic increase in telehealth-delivered healthcare, post-pandemic data demonstrate a steady use of telehealth visits, with an increased emphasis on video-based encounters [Citation2]. Telehealth use can improve health care access, quality, communication, and outcomes across a variety of health conditions [Citation3–6]. There has been differential use of telehealth-delivered care across specialties, with mental health services demonstrating higher adoption of telehealth [Citation7]. While there are early signals of successful potential telehealth use among patients with cancer [Citation8], less is known about telehealth preferences and experiences in the medical oncology setting.

The national Veterans Health Affairs Health Care System (VA) was an early adopter of telehealth-delivered care [Citation9]. In the pre-pandemic era, the VA routinely provided many telehealth-care delivered services including primary care and mental health care. Telehealth use in the VA has increased by 3.9-fold from 10% prior to the pandemic to 38% currently [Citation10]. Additionally, in fiscal year 2021, which is the most recent year with complete data, nearly 3.8 million Veterans had a telehealth visit [Citation10]. While there is clear evidence that Veterans in the general VA population (e.g. non-cancer) used telehealth, less is known about telehealth use among Veterans with cancer.

The VA cares for approximately 46,000 Veterans with newly diagnosed cancer annually [Citation11,Citation12]. Additionally, nearly 38% of VA health care system users live in rural areas where oncologists may be in short supply [Citation13,Citation14]. Many aspects of cancer care can also be practically delivered via telehealth including cancer screening, patient monitoring and symptom management, treatment, and survivorship care. As a result, the VA launched the National TeleOncology Service (NTO) [Citation13]. The NTO is a clinical service that enables VA oncologists from across the country to provide services via telehealth to Veterans with cancer who are in a different geographic area. As of fiscal year 2021, 23 VA clinics were served by or engaged in planning the delivery of NTO and there were 24 physicians providing care through an NTO virtual hub site [Citation13]. NTO is continues to be scaled out nationally across the VA health care system. As NTO services are expanding rapidly and demand is high, this is a crucial time for an early evaluation to inform ongoing health services delivery to provide early information about clinician and Veteran experiences with NTO.

Our goal was to inform the refinement and scale-out of NTO. Using qualitative research methodology, we sought to understand early experiences of medical oncologists, Veterans, and other clinical staff to inform national NTO scale-out.

Materials and methods

Study setting. We conducted this qualitative descriptive project [Citation15,Citation16] in the national VA health care system, with a focus on recruiting clinicians who provided care and/or Veterans who received care from the three early adopting NTO hub sites: Durham, NC; Omaha, NE; and Pittsburgh, PA.

Interview guide development. Our research was guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [Citation17,Citation18]. The CFIR was developed by VA researchers, has been used across a variety healthcare settings, has been refined based on user feedback, and can be applied as a framework to guide examination of real-world implementation efforts to provide an indication of factors associated with implementation. CFIR is one of the most widely cited frameworks in the field of implementation science [Citation19]. Guided by CFIR, our multidisciplinary team selected specific CFIR constructs across domains to develop a semi-structured qualitative interview guide for individual Veteran interviews and a separate qualitative focus group guide for VA clinicians. All members of the team have had training and experience in conducting qualitative data collection and analysis.

Data collection. We purposively recruited two participant populations – clinicians and Veterans – with the goal of achieving information power [Citation20]. We invited clinicians from early adopting NTO sites: (1) Durham, NC; including Clarksburg, WV; Salisbury, NC; Salem, VA; Sioux Falls, ND and Fayetteville, AR; (2) Omaha, NE; including Lincoln, NE; Grand Island, NE; (3) Pittsburgh, PA; including Altoona, PA; Erie, PA. Focus groups were held during a standing NTO meeting time. A research staff person contacted all NTO providers who are invited to participate in the weekly standing meeting to offer them the opportunity to participate in a focus group. All clinicians provided telehealth-based oncology care. We held separate focus groups for physicians and non-physicians. We conducted separate groups to be mindful of professional dynamics and supervisory role considerations. Additionally, we split groups based on sample size considerations for conduct of virtual focus groups. All focus groups included a trained facilitator (HK or CB) and notetaker (JM or CB).

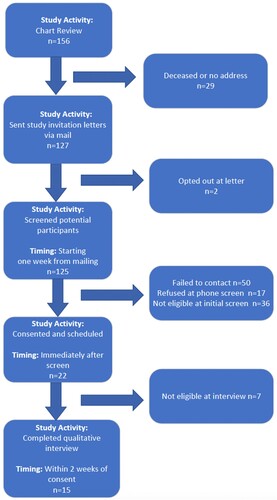

We purposively sampled Veteran participants based on the following characteristics: (1) diagnosed and/or treated from December 2016 through March 2021 with prostate, non-small cell lung, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or colorectal cancer as indicated by ICD-10 codes, and (2) obtained telehealth-delivered VA cancer care in October 2016 through July 2022 at one of the included sites. We also reviewed the Veteran sample to ensure that there was diversity and representation regarding Veterans’ cancer type, race, and sex. Eligible Veterans were identified via the electronic health record. A research team member sent them a letter explaining the research and followed-up with a phone call to determine interest and availability to complete an interview. A research team member initiated a telephone call via MS Teams audio to conduct Individual interviews with Veterans (CB; ).

Both focus groups and interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed using MS Teams. Research team members also took structured notes using a standardized template. Clinician and Veteran participants provided verbal consent prior to conducting qualitative data collection. This study was approved by the Durham VA Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis. We used a rapid qualitative analysis approach with purposeful data reduction activities [Citation15,Citation16]. Throughout the data collection and analysis process, we considered information power as well as rigor [Citation20]. The first step in data analysis involved two research team members (JM, CB) conducting interim analysis of the oncologist focus groups and non-oncologist focus groups, and one research team member (CB) conducting interim analysis of the Veteran interviews. Interim analysis consisted of reviewing templated notes to respond to “Top of Mind” questions. Interim analysis results were presented to the project lead and NTO leadership team for content-level feedback to focus data reduction activities on actionable information to inform NTO.

Next, using templated notes and feedback results from the interim analysis, research team members (CB & JM) independently summarized participant responses to each focus group question and subsequently combined summaries into an excel matrix. For Veteran interviews, one research team member (CB) summarized participant responses to each interview question and transferred summaries into a separate excel matrix. The senior qualitative researcher (HK) provided a close overread of Veteran interview findings. Any identified discrepancies with summaries were addressed by the research team.

The clinician focus groups and Veteran patient interview analysis matrices focused on CFIR key constructs. For each construct, two research team members (JM and CB) summarized main findings based on the summarized focus group data, and one research team member (CB) summarized main findings based on the summarized interview data. Key construct findings were then demonstrated by quotes from the focus group and interview participants in the matrices. Any discrepancies between summaries were again noted and addressed by the qualitative research team. The matrices with key constructs, findings, and illustrative quotes were then reviewed by the senior qualitative researcher (HK) and the project lead (LZ). The project lead then mapped the summary matrix to the current context of NTO and vetted the matrices with NTO leadership. Following separate analysis and vetting of the clinician and Veteran patient data, we integrated the analysis results below to facilitate their presentation.

Results

Participant sample. For the clinician focus groups, we sent invitations to 19 physician oncologists and 17 other clinicians. This resulted in three separate focus groups. One focus group was attended by 3 physician oncologists, one was attended by 5 other clinicians (2 nurse practitioners and 3 registered nurses), and the third focus group was attended by 4 other clinicians (1 nurse practitioner and 3 registered nurses). Clinician focus groups lasted approximately 29 min. We interviewed 15 Veterans whose median age was 72.4 years. The sample was predominately white (60%) men (87%). The participants were diagnosed with prostate (n = 7), lung (n = 3), colorectal (n = 4), and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 1). For the Veteran interviews, we mailed 127 invitations and conducted 15 interviews (). Veteran interviews lasted approximately 36 min.

General Veteran Experiences. Veteran participants’ experiences with the NTO program ranged from one to several NTO appointments, including video calls from their spoke site or phone calls and/or video calls from their homes. Among Veterans who had video appointments from their spoke site, clinical staff connected them to the video appointment and often stayed to assist with taking notes and asking questions of the oncologist. Participants typically had vitals and labs taken at their spoke site before the appointment so that results could be discussed with the oncologist. Patients’ family members could accompany them to appointments to ask questions about the patients’ treatment and health. Among Veterans who had NTO phone calls from home, NTO oncologists discussed their health status, lab results, and impact of treatment during the phone calls; participants often went to their local VA clinic before their phone appointment for labs, scans, and/or treatment.

Relative advantage. Clinician and Veteran participants noted the relative advantage of NTO over traditional in-person care. According to both participant groups, a primary advantage of NTO is that it facilitates access to oncology specialists for Veterans who may have to travel long distances to appointments and who may not have access to an oncologist at their local VA clinic (). Clinicians also noted that NTO provides teams of providers and staff to facilitate better care coordination and expedite necessary follow-up services for Veterans diagnosed with cancer. According to clinicians, NTO keeps Veterans engaged in the VA healthcare system which understands their unique needs and facilitates access to an array of multidisciplinary supportive services, including social workers and dieticians, not available in community care.

Table 1. Participant key quotes.

Whereas clinicians described the systems level advantages of NTO and how these benefit patients, Veterans reported on the personal advantages of NTO over traditional, in-person care. Veterans noted the convenience of avoiding long travel distances to their appointments, especially when they have multiple appointments, are not feeling well due to having cancer or other health issues, or during the pandemic. A few Veterans mentioned that the main advantage of NTO for them is not virtual over in person appointments, but rather the option for video calls over phone calls, because video calls allowed them to still see their oncologist which feels like an in-person visit.

Tension for Change. Clinician and Veteran participants agreed that the NTO program is strongly needed to facilitate access to specialists for Veterans diagnosed with cancer living far from VA medical facilities, in areas that lack specialty oncologists, and in areas far from community care. Veterans emphasized that NTO was vitally necessary to their health because there was no cancer care available at their local VA clinic.

Patient Needs and Resources. There was consensus across clinicians that the NTO program, with its focus on specialized and individualized oncology care and increased access to care for patients through the virtual platform, is working well to meet the needs of their Veteran patients diagnosed with cancer. Veterans also agreed that NTO is meeting their needs by providing them with access to a team of knowledgeable and caring oncologists, helpful and comforting support staff, and effective and state-of-the-art cancer treatment without having to endure long distance travel to medical visits. Some veterans described the convenience of also receiving their cancer treatment and lab tests at their local VA or community care center through the NTO program. Veterans were pleased that NTO doctors and staff were responsive to their needs and questions and encouraged their family members to attend their cancer care appointments and ask questions about their treatment and care. Furthermore, Veterans reported that the logistics of NTO have largely met their needs, including access to well-functioning technology for video calls at their local VA, punctual appointments, smooth appointment scheduling, and prompt sharing of test results and other medical information between their local VA staff and NTO oncologist.

Although clinician and Veteran participants agreed that NTO is largely meeting patient needs, some noted that one disadvantage of NTO is that it is not as personable as in-person care. One Veteran stated that she would have preferred in person doctor visits over video appointments to receive comfort and assurance from her doctor in person due to the seriousness of being diagnosed with cancer. Another participant explained that he would have preferred in person visits to see his oncologist’s reactions and concern for him in person, and another participant explained that meeting in person would have allowed him to be more “candid” with his oncologist. Nevertheless, Veterans reported that NTO had not changed their relationship with their cancer doctor whom they described as knowledgeable, patient, thorough, and concerned about their health. Additionally, clinicians explained that although Veterans were initially skeptical about meeting with their provider virtually, they ultimately “felt that they were in the same room” with the oncologist and appreciated that NTO specialists are more knowledgeable than onsite general oncologists.

Reflecting and Evaluating. Clinician and Veteran participants were asked to reflect and evaluate on the progress and quality of their experiences with NTO implementation. Non-oncologist clinicians reported that the current NTO program is successful in terms of staffing, teamwork and coordination, and prompt, remote communication between teams; however, they also reflected that NTO could delay care due to a need for more oncologist physicians to support rapidly increasing demand for NTO. Oncologists had suggestions for improving communication and distribution of administrative tasks, such as scheduling and ordering labs, among NTO team members to enhance patient care and avoid physician burnout. Veterans also suggested improving communication, but between providers and patients, by ensuring Veteran patients feel comfortable asking questions, clinicians provide clear responses, and Veterans can contact providers if they have questions after their appointment.

Clinicians noted that technology use can be challenging for some Veterans, such as older patients, and Veterans suggested having more information and training for NTO patients about how to access video calls from their home and about the NTO program generally. Veterans also suggested addressing technical challenges by providing a mobile nurse or recruiting volunteers to visit Veteran patients at home to help them connect to NTO appointments, especially for Veterans who may not have a computer. Nevertheless, Veterans reported confidence in their ability to successfully use telehealth for their oncology appointments, as those who attended their appointments via video at their local VA relied on NTO staff to connect them to virtual appointments, check their vitals, and follow up on requests from their oncologists. Participants who accessed their appointments from their home were also confident in their ability to do so by phone but not as confident about video appointments due to technical limitations.

Furthermore, Veteran participants reported that NTO would be very helpful for Veterans like them, particularly those with mobility issues, who are not feeling well, who lack transportation and/or support getting to medical appointments, and who live far from their cancer doctor. However, participants also mentioned that Veterans may need additional support to successfully use NTO, including assistance connecting to virtual appointments from home, transportation to spoke site, physical support getting to appointments due to feeling weak, clinical staff support at spoke site to connect to video calls, and an initial in-person visit with their oncologist for those newly diagnosed with cancer due to the emotional gravity of a cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

The VA health care system has been a significant and early adopter of telehealth [Citation21], yet telehealth use in medical oncology remains relatively novel. Within the VA, telehealth has been used for specific purposes, such as virtual tumor boards, remote cancer survivorship care, and genetic testing and counseling, among others [Citation22–26]. Building from these early experiences, the NTO is a growing national program to provide nearly comprehensive and remotely delivered care to Veterans seeking care across the cancer care continuum [Citation13]. Early evidence from the VA suggests that telehealth for Veterans’ cancer care is associated with high patient satisfaction and positive financial and environmental impacts [Citation8]. A limitation of our work is that it is U.S.-centric and focused on U.S. Veterans. However, in our study, both clinician and Veteran participants that we interviewed had mostly positive remarks regarding NTO. One specific area of shared positive remarks was that both participant groups appreciated that NTO overcomes traditional barriers to accessing cancer care such as transportation and travel times. Transportation is a well-documented barrier to cancer care among Veterans; [Citation27–30] thus, for Veterans with transportation problems NTO may provide a significant advantage over traditional in-person care. Similarly, both clinicians and Veterans reported that NTO is beneficial in providing access to specialists who live in isolated areas that lack specialized cancer services. This is of critical importance because approximately one quarter of Veterans live in highly rural areas [Citation31] and Veterans are less likely to undergo certain cancer services like cancer screenings [Citation32]. Historically, when a service is not available in a timely manner close to a Veterans home, the VA may pay for a Veteran to receive needed care from local provider in their community. However, in most of rural America there is a shortage of oncologists, which is resulting in poor treatment access [Citation33–35]. NTO may fill a critical gap for Veterans needing cancer services that are unavailable close to their home. Moreover, telehealth has been proposed by leading cancer care delivery experts as a mechanism to overcome this workforce problem [Citation36] and the NTO is well suited to address this. Interestingly, while clinicians noted that technology comfort and access may present a problem for some Veterans, most Veterans did not share this view. Veterans suggested that more information and training in technology use would be beneficial but reported a high degree of confidence in their ability to use telehealth. While NTO is well received overall, our research uncovers additional research questions. For example, what is the best way to assess a Veteran’s preferences regarding NTO use versus in-person care and how the quality and outcomes of NTO compare with cancer care provided in-person within the VA. While some questions remain, our early findings strongly support the relative advantage of NTO over traditional in-person care to fill critical cancer gaps and increase accessibility to specialized cancer services for Veterans, regardless of where they live.

Disclaimers

The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Previous presentations

This work has not been previously presented or published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Weiner JP, Bandeian S, Hatef E, et al. In-person and telehealth ambulatory contacts and costs in a large US insured cohort before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e212618. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2618

- Lee EC, Grigorescu V, Enogieru I, et al. Updated national survey trends in telehealth utilization and modality (2021-2022). US Department of Health and Human Services. 2023.

- Batsis JA, DiMilia PR, Seo LM, et al. Effectiveness of ambulatory telemedicine care in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. Aug 2019;67(8):1737–1749. doi:10.1111/jgs.15959

- Flodgren G, Rachas A, Farmer AJ, et al. Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Sep 7 2015;2015(9):Cd002098. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002098.pub2

- Lewinski AA, Walsh C, Rushton S, et al. Telehealth for the longitudinal management of chronic conditions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. Aug 26 2022;24(8):e37100. doi:10.2196/37100

- Paro A, Rice DR, Hyer JM, et al. Telehealth utilization among surgical oncology patients at a large academic cancer center. Ann Surg Oncol. Nov 2022;29(12):7267–7276. doi:10.1245/s10434-022-12259-9

- Drake C, Lian T, Cameron B, et al. Understanding telemedicine's “New Normal": variations in telemedicine use by specialty line and patient demographics. Telemed J E Health. Jan 2022;28(1):51–59. doi:10.1089/tmj.2021.0041

- Jiang CY, Strohbehn GW, Dedinsky RM, et al. Teleoncology for veterans: high patient satisfaction coupled with positive financial and environmental impacts. JCO Oncol Pract. Sep 2021;17(9):e1362–e1374. doi:10.1200/op.21.00317

- Ogrysko N. VA’s telehealth program is already the largest in the nation. It’s about to get bigger. Federal News Network. 2018.

- Affairs DoV. Vha support service. Center: Telehealth Workload.

- Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693–701. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-11-00434

- Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. Jul 2017;182(7):e1883–e1891. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-16-00371

- Zullig LL, Raska W, McWhirter G, et al. Veterans health administration national teleoncology service. JCO Oncol Pract. Apr 2023;19(4):e504–e510. doi:10.1200/op.22.00455

- Zullig LL, Goldstein KM, Bosworth HB. Changes in the delivery of veterans affairs cancer care: ensuring delivery of coordinated, quality cancer care in a time of uncertainty. J Oncol Pract. Nov 2017;13(11):709–711. doi:10.1200/jop.2017.021527

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. Aug 2000;23(4):334–340. 10 .1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4 < 334::aid-nur9 > 3.0.co;2-g

- Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. Feb 2010;33(1):77–84. doi:10.1002/nur.20362

- Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ. A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. Jun 2011;25(2):194–205. doi:10.1037/a0022284

- Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, et al. The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):75. doi:10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0

- Skolarus TA, Lehmann T, Tabak RG, et al. Assessing citation networks for dissemination and implementation research frameworks. Implement Sci. Jul 28 2017;12(1):97. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0628-2

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. Nov 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Spotlight on telehealth. October 5, 2023. [accessed 2023 October 5]. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/news/feature/telehealth-0720.cfm.

- Cheng HH, Sokolova AO, Gulati R, et al. Internet-based germline genetic testing for men with metastatic prostate cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. Jan 2023;7:e2200104. doi:10.1200/po.22.00104

- Ha DM, Comer A, Dollar B, et al. Telemedicine-based inspiratory muscle training and walking promotion with lung cancer survivors following curative intent therapy: a parallel-group pilot randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. Sep 1 2023;31(9):546. doi:10.1007/s00520-023-07999-7

- Ha DM, Nunnery MA, Klocko RP, et al. Lung cancer survivors’ views on telerehabilitation following curative intent therapy: a formative qualitative study. BMJ Open. Jun 23 2023;13(6):e073251. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073251

- Marshall CL, Petersen NJ, Naik AD, et al. Implementation of a regional virtual tumor board: a prospective study evaluating feasibility and provider acceptance. Telemed J E Health. Aug 2014;20(8):705–711. doi:10.1089/tmj.2013.0320

- Rock MC, Cidav Z, Sun V, et al. Adapting to the burdens of care: a telehealth program for cancer survivors with ostomies. Support Care Cancer. Dec 14 2022;31(1):15. doi:10.1007/s00520-022-07461-0

- Colamonici M, Khouzam N, Dell C, et al. Promoting lung cancer screening of high-risk patients by primary care providers. Cancer. Nov 15 2023;129(22):3574–3581. doi:10.1002/cncr.34955

- Navuluri N, Morrison S, Green CL, et al. Racial disparities in lung cancer screening among veterans, 2013 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. Jun 1 2023;6(6):e2318795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18795

- Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Provenzale D, et al. Transportation: a vehicle or roadblock to cancer care for VA patients with colorectal cancer? Clin Colorectal Cancer Mar. 2012;11(1):60–65. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2011.05.001

- Jazowski SA, Sico IP, Lindquist JH, et al. Transportation as a barrier to colorectal cancer care. BMC Health Serv Res. Apr 13 2021;21(1):332. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06339-x

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Rural Health. Rural veterans. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp.

- Spalluto LB, Lewis JA, Samuels LR, et al. Association of rurality with annual repeat lung cancer screening in the veterans health administration. J Am Coll Radiol. Jan 2022;19(1 Pt B):131–138. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2021.08.027

- Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, et al. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. Jul 2017;26(7):992–997. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-17-0092

- Shih YT, Kim B, Halpern MT. State of physician and pharmacist oncology workforce in the United States in 2019. JCO Oncol Pract. Jan 2021;17(1):e1–e10. doi:10.1200/op.20.00600

- West HJ, Bange E, Chino F. Telemedicine as patient-centred oncology care: will we embrace or resist disruption? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. Oct 2023;20(10):659–660. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00796-5

- Levit L, Patlak M. Ensuring quality cancer care through the oncology workforce: sustaining care in the 21st century: workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2009.