ABSTRACT

Background: Physicians and other health care personnel rely on the peer-reviewed biomedical literature as a key source for making clinical decisions. Thus, ensuring that the nonclinical and clinical findings published in biomedical journals are reported accurately and clearly, without undue influence from commercial interests, is essential. Accordingly, beginning in the mid-1990s and continuing to the present, various organizations, including the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, the American Medical Association, the Council of Science Editors, the American Medical Writers Association, and the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals, have published guidelines to strengthen and uphold ethical standards in biomedical communications.

Scope: A task force of staff members from the AXIS group of companies reviewed these and other guidelines to assess the need for a good publication practices (GPP) document specific to medical communications agencies. As this review demonstrated an unmet need, the task force was charged with developing GPP guidelines for the AXIS group of agencies in the United States.

Findings: Although such guidelines have been previously published on behalf of medical journal editors and publishers, medical writers, academic centers, and pharmaceutical companies, there has been no prior publication in the peer-reviewed literature of good publication practices for medical communications agencies, which face unique challenges in negotiating a balance among authors, sponsoring companies, and biomedical publishers.

Conclusion: This article presents and discusses these GPP guidelines. To our knowledge, this is the first publication of guidelines developed from the perspective of a medical communications agency.

* Presented in part at the International Publication Planning Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, June 26–27, 2008

Introduction

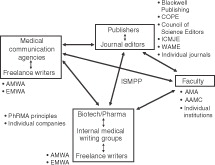

Research findings published in peer-reviewed biomedical journals are perhaps the most important source of information for physicians in making treatment decisions. In the early 1990s, initiatives were undertaken to improve the quality and applicability of such communications by developing standards for reporting clinical trial results (e.g., through the CONSORT group, founded in 1993)Citation1 and rigorous systematic reviews of evidence (e.g., the Cochrane Collaboration, also founded in 1993)Citation2. As interest in unbiased and evidence-based communications continued to grow, the manner in which clinical trial results were written and published came under greater scrutiny; and, in particular, concerns arose among medical professionals, academic institutions, regulators, and the public regarding possible undue influence by pharmaceutical and biotechnology firms on biomedical journal publishing. In response, beginning in the mid-1990s and continuing to the present, several organizations have published guidelines and recommendations on the role of medical writers in developing manuscripts submitted to peer-reviewed journals and congresses. Such guidelines include those from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)Citation3, Council of Science EditorsCitation4, American Medical AssociationCitation5, Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)Citation6, World Association of Medical EditorsCitation7, and Blackwell PublishingCitation8 on behalf of medical journals; the American Medical Writers AssociationCitation9 and European Medical Writers Association (EMWA)Citation10 representing the views of medical writers; and the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP)Citation11, an organization encompassing pharmaceutical companies, medical communications agencies, medical writers, and journal editors. In addition, a working group composed of individuals employed by various pharmaceutical companies has published good publication practices for pharmaceutical companiesCitation12, while the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) included a brief overview of publication practices within its larger document on principles for the conduct of clinical trials and communication of resultsCitation13. More recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges issued a report with recommendations on the involvement of the pharmaceutical industry in medical education, which mentions industry-sponsored writing supportCitation14. All of these documents discuss at least briefly the involvement of medical writers in general, who may be independent contractors or employees of pharmaceutical/biotechnology companies, contract research organizations, or medical communications agencies (). However, no guidelines have been published specifically focusing on the role of medical communications agencies in the development and publication of biomedical information.

Figure 1. The relationships among the various contributors (inside the boxes) to the development and publishing of peer-reviewed literature. Organizations that have developed publicly available guidelines to govern the publication process are noted outside the boxes. Abbreviations: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; AMA, American Medical Association; AMWA, American Medical Writers Association; COPE, Committee on Publication Ethics; EMWA, European Medical Writers Association; ICMJE, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; ISMPP, International Society for Medical Publication Professionals; PhRMA, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America; WAME, World Association of Medical Editors

Poised between the sometimes competing interests of authors, sponsoring companies, and journals or congresses, medical communications agencies face unique challenges in ensuring that any publications in which they collaborate are scientifically sound and compliant both with the generally accepted ethical guidelines discussed above and the particular requirements of specific publishing venues. Although general compliance considerations for medical communications agencies, including those relating to publications, were recently described by Cairns and YarkerCitation15, we perceived an unmet need for dissemination of specific good publication practice guidelines addressing issues faced by such agencies.

Accordingly, the guidelines in the Appendix were developed collaboratively by a working group of employees within the AXIS group of medical communications agencies (hereafter referred to as MedComm group). The working group convened for a number of teleconferences to discuss and reach consensus on issues; subsequently, the draft guidelines were repeatedly reviewed by all participants and refined until approved. Rather than comprising a specific set of rules, these guidelines are intended to provide general principles of ethical conduct relevant to medical communications agencies in collaborating with a wide range of pharmaceutical and biotechnology sponsoring companies (clients). Although they were developed for the use of agencies operating in the United States, we believe that they may be of interest to agencies in other countries as well. These guidelines will evolve as the publication environment changes and will therefore be updated annually after the annual meetings of ISMPP and The International Publication Planning Association (TIPPA, an industry-run association focused on medical publications and communications).

Discussion

Over the course of a year, employees representing various agencies from the MedComm group convened to address the unmet need for good publication practice guidelines focused specifically on issues faced by medical communications agencies. The resulting MedComm GPP guidelines (see Appendix) are aligned with the existing publication guidelinesCitation3–13 on several key issues such as authorship, disclosure of medical writer involvement, funding source, and potential conflicts of interest.

Although there are no areas in which the MedComm GPP guidelines contradict the existing published guidelines, we identified topics that either were absent from such guidelines or required expansion for specific application to medical communications agencies. The existing guidelines govern the interactions among medical writers (as individuals), authors, and journals/congresses; the MedComm GPP guidelines go beyond these to address the interactions among medical writers and editors as part of an agency, the authors, the journals/congresses, and the company sponsoring the publication.

Although the medical writer has the strongest impact, from the agency side, on collaborative content development, the tripartite balancing act among the agency, author, and sponsoring company is far more complex. For example, an agency generally provides both authors and the sponsoring company a wider range of services than medical writing alone; additional services may include development of illustrations and graphics, copyediting and journal-specific formatting, administrative support in tracking and compiling forms required for publication, managing multiple stages of review, compiling comments, and submitting manuscripts. Moreover, the agency may give guidance on strategic publications planning across various stages of a product's life cycle or may provide services unrelated to publications and medical writing work.

The additional interaction with a sponsoring company is unique to the medical communications industry and is a potential source of conflict with authors, journals, and congresses. Accordingly, compared with existing publication guidelines, the MedComm GPP includes more specific guidance on the collaborative process among all stakeholders, including carefully delineating the respective responsibilities of the authors, medical writers and editors, and sponsoring company from conception through submission of a manuscript, and resolving possible conflicts among authors, sponsoring companies, agency, and journals.

The MedComm GPP guidelines also address certain components of the collaborative process that are unique to publication support through an agency. For example, medical communications agencies may be asked to submit manuscripts on behalf of the corresponding author. The MedComm GPP provides guidance on how an agency can carry out the submission process in an ethical manner to facilitate publication in compliance with journal requirements. In addition, the MedComm GPP incorporates topics that, although not unique to agencies, may not be covered in existing guidelines. For example, an agency is often entrusted by the sponsoring company and authors with confidential patient and proprietary business information; thus, the MedComm GPP guidelines specifically discuss issues of data security and confidentiality through staff and contractor training as well as technological means, as appropriate.

In the complex balance among authors, agency, and sponsoring company, conflicts may arise regarding the MedComm GPP guidelines. Conflict resolution in such circumstances will require that the agency recognize which elements of the guidelines are negotiable and which are not. For example, in certain circumstances, the MedComm GPP guidelines allow the omission of the agency's name when acknowledging third-party editorial support, but the fact that a medical writer or editor was involved and the name of the funding source must always be disclosed and fully transparent. Moreover, serious conflicts among the parties may be avoided entirely if the agency, at the outset of a project, informs the sponsoring company and authors about its adherence both to generally accepted ethical publishing standards and to its own good publication practices guidelines.

Good publication practices are useful only to the extent that they are communicated to all stakeholders – agency staff, contractors, authors, and sponsoring companies – involved in content development and publication, enabling them to be allies in advancing ethical standards in medical publishing. Indeed, an agency can provide a valuable service to its clients by remaining up-to-date on developments in publishing standards and by educating its clients that adherence to good publication guidelines is in the sponsoring company's best interest and will enhance the likelihood of publication of the manuscripts the client supports.

The publication of these MedComm GPP guidelines, developed by and for the use of a medical communications agency, is particularly timely, considering the recent article by Ross et al. critiquing the publication development approach used by Merck & Co. Inc. in support of rofecoxibCitation16. The unethical practices detailed in the article, specifically the practices of ‘ghostwriting’ (medical writing support provided by an individual who is not acknowledged as a contributor) and ‘guest authorship’ (including as an author an individual who did not contribute to a manuscript sufficiently to merit authorship), contradict the MedComm GPP guidelines and other good publication practice documentsCitation3–13. It is important to note, however, that the situation described by Ross et al. occurred in a different publishing environment almost 10 years ago, before many of regulations and guidelines cited herein were developed; and, further, both Merck and some of the authors of the publications referenced by Ross and colleagues deny the assertion that the authors had little involvement in manuscript development. Notably, although Ross et al. recognize that the current prevalence of such practices is difficult to quantify, they nevertheless suggest that such practices may still be relatively widespread in biomedical publishing given the very existence of a medical writing industry. This interpretation unjustly characterizes the medical communications industry in general as being unethical. We feel strongly that medical communications agencies offer legitimate and valuable services that, when performed in compliance with good publication practices, are both ethical and beneficial. The benefits accrue not only to company sponsors but also to the medical community, patients and their caregivers, and society at large, because such efficient and expert content development facilitates the communication of important medical findings with timeliness and clarity.

Conclusions

In developing, disseminating, and, most importantly, adhering to guidelines such as those presented here, the medical communications industry as a whole can help to eradicate unethical practices in biomedical publishing and foster a collaborative and ethical publication environment. Thus, contrary to the implication by Dr Ross and his colleagues, the medical communications industry can actually be part of the solution, not the problem, in ethical publication practice.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest: All the authors are employees of AXIS Healthcare Communications agencies and developed this manuscript as part of their employment.

Notes

* Presented in part at the International Publication Planning Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, June 26–27, 2008

References

- The CONSORT Group. How CONSORT began. Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/index.aspx?o=1210 [Last accessed 24 March 2008]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. About the Cochrane Collaboration. Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/docs/descrip.htm [Last accessed 24 March 2008]

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. Available at: http://www.icmje.org [Last accessed 24 March 2008]

- Scott-Lichter D; and the Editorial Policy Committee, Council of Science Editors. CSE’s White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications. Reston, VA: CSE, 2006

- Iverson C, Christiansen S, Flanagin A, et al. AMA Manual of Style: A Guide for Authors and Editors, 10th edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 126-299

- Committee on Publication Ethics. Guidelines on good publication practice. Available at: http://www.publicationethics.org.uk/guidelines [Last accessed 1 October 2008]

- World Association of Medical Editors. WAME policy statements. Available at: http://www.wame.org/resources/policies [Last accessed 24 March 2008]

- Graf C, Wager E, Bowman A, et al. Best practice guidelines on publication ethics: a publisher's perspective. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61 (s152):1-26

- American Medical Writers Association. AMWA code of ethics. Available at: http://www.amwa.org/default.asp?id=114 [Last accessed 22 February 2008]

- Jacobs A, Wager E. European Medical Writers Association (EMWA) guidelines on the role of medical writers in developing peer-reviewed publications. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:317-21

- Norris R, Bowman A, Fagan M, et al. International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) position statement: the role of the professional medical writer. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;32:1837-40

- Wager W, Field E, Grossman L. Good publication practices for pharmaceutical companies. Curr Med Res Opin 2003; 19:149-54

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Principles on conduct of clinical trials and communication of clinical trial results. Available at: http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org/primers/2004-06-30%201035.pdf [Last accessed 28 August 2008]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Industry funding of medical education: report of an AAMC task force, June 2008. Available at: https://services.aamc.org/Publications/showfile.fm?file=version114.pdf&prd_id=232 [Last accessed 28 August 2008]

- Cairns A, Yarker YE. The role of healthcare communications agencies in maintaining compliance when working with the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1371-8

- Ross JS, Hill KP, Egilman DS, et al. Guest authorship and ghostwriting in publications related to rofecoxib: a case study of industry documents from rofecoxib litigation. JAMA 2008; 299:1801-12

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. ACCME policies. Available at: http://www.accme.org/index.cfm/fa/Policy.home/Policy.cfm [Last accessed 2 October 2008]

- United States. Department of Health and Human Services. OCR privacy brief: summary of the HIPAA privacy rule, updated May 2003. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacysummary.pdf [Last accessed 2 October 2008]

Appendix: MedComm Good Publication Practices

Mission statement

The goal of the MedComm Good Publication Practices (MedComm GPP) guidelines is to provide guidance for medical communications agencies supporting the development of medical publications in collaboration with both the research sponsors and the authors/researchers responsible for the design of the study and the collection of the data. These activities are to be conducted in a professional, ethical, and scientifically sound manner consistent with existing publication guidelines and in compliance with journal and congress requirements.

The various guidelines that have been published to date reflect the perspective of medical journalsCitation3, medical writersCitation9,Citation10, publishing professionalsCitation11, and the pharmaceutical/biotechnology industryCitation12,Citation13. None of these guidelines provide specific direction regarding the role of medical communications agencies in providing medical publication support.

The MedComm GPP guidelines are intended to fill this gap and to be applied in conjunction with existing guidelines such as the Good Publication Practice guidelines for pharmaceutical companiesCitation13 or those developed by the ICMJECitation3.

Scope

MedComm GPP guidelines cover data dissemination by means of publication in peer-reviewed scientific and biomedical journals (both print and online) as well as abstracts, posters, and oral presentations developed for scientific and biomedical congresses.

MedComm GPP guidelines do not cover content development for accredited continuing medical education activities; MedComm group endorses and adheres to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) policies in this regardCitation17.

MedComm GPP guidelines do not cover content development for promotional activities, which include advisory boards, investigator meetings, consensus meetings, nonaccredited educational activities, and advertising. MedComm group adheres to all relevant regulations and legislation in this regard.

Guidelines

MedComm GPP guidelines are designed to govern the process by which the medical communications agency (agency) and its medical writing staff (medical directors, writers, and editors) collaborate with pharmaceutical/biotechnology sponsors of the research and authors/researchers to develop scientific/medical publications as defined above (see Scope).

Role of third-party medical writing

Contributions of medical writers

Third-party medical writers and editors make an honorable and important contribution to the dissemination of scientific/clinical data to the medical community and society at large by providing expertise in publication preparation. Medical writers and editors collaborate closely with the authors, the originators of the research data, as well as the sponsor of the research to develop scientifically rigorous, clear, and concise publications in a timely manner in adherence to journal or congress guidelines and existing good publication guidelines.

Authorship

Authorship criteria

MedComm GPP guidelines uphold the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Writing and Editing for Biomedical PublicationCitation3, which state: ‘Authorship credit should be based on (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published. Authors should meet conditions 1, 2, and 3.’

According to the Uniform Requirements, a third-party medical writer generally does not merit authorship; however, the writer should be included in the acknowledgments (see Transparency and acknowledgments).

Transparency and acknowledgments

MedComm GPP guidelines support the fundamental principle of full transparency in the publication process. Accordingly, the contributions of the individual third-party medical writers/editors, the agency involved, and the funding source should be fully disclosed in the manner required by the journal/congress (e.g., in the online submission process), as well as in the acknowledgment section of the publication.

MedComm GPP guidelines include two recommended wordings for acknowledgments (similar to those developed by EMWACitation10), depending on the contributions of the medical writer(s)/editor(s) to the development of the publication:

‘The authors thank Jane Doe, PhD [MD, PharmD, etc], in association with MedComm group for providing medical writing assistance supported by ABC Pharmaceuticals.’

or

‘The authors thank Jane Doe, PhD [MD, PharmD, etc], in association with MedComm group for providing editorial assistance supported by ABC Pharmaceuticals.’

If the authors or the sponsoring company disagree with the MedComm GPP guideline recommendations, the agency should engage in a dialogue with them regarding best publication practices. MedComm group considers the funding source to be the most critical component of the disclosure; thus, the acknowledgment may follow the preferences of the authors or sponsoring company as long as (1) it does not contradict the journal or congress guidelines and (2) it identifies the funding source as a minimally required disclosure.

In keeping with ICMJE requirements, the agency should routinely obtain and keep on file permission from the medical writers/editors involved in the development of a publication to be named in the acknowledgment section. Permission will be forwarded to the journal/congress as part of the submission process if required.

Medical writer/editor collaboration with authors

The role of third-party medical writers and editors is to assist the authors with content development. Accordingly, the authors should control and approve all aspects of the publication from concept to completion.

Depending on the individual project and authors involved, the medical writer or editor may provide services ranging from limited editorial support (e.g., copyediting and styling the publication according to journal/congress guidelines) to full medical writing assistance (e.g., performing literature searches, developing tables and figures, writing outlines and drafts).

Outreach to an author may be initiated by the sponsoring company or by the agency. If undertaken by the agency, the first contact should occur at the inception of the project, and the agency should fully disclose the involvement of the sponsoring company.

Regardless of the extent of the services provided, the authors are responsible for, and retain control of, the content and scientific integrity of the publication.

The review process

MedComm GPP guidelines emphasize that all authors are fully responsible for the content of the publication. Thus, a well-managed review process between the authors and the agency is essential to the integrity of the work. Although the number of reviews and execution of the process will vary depending on the specific project, the agency should adhere to the following principles:

The lead author, at a minimum, provides direction on topic and scope before the agency initiates work on the publication.

At each stage in the content development process, the authors will review the materials (e.g., outlines, drafts, graphics, and tables) and make decisions regarding content direction.

Not all of the authors need to be involved at every developmental stage, but all must provide content direction at least once prior to final approval.

Content will be revised according to authors’ comments, and additional review and revisions will occur until the authors are satisfied with the content.

Authors must be given adequate time during each review cycle to read the work critically and provide in-depth comments.

For a multiauthored manuscript, all authors must participate in the review process and provide final approval before submission.

The sponsoring company should adhere to the following guidelines during the review process:

If some or all authors are company employees, collaboration with the authors will follow the aforementioned steps.

For publications in which there are no company authors, such as manuscripts based on investigator-sponsored trials (ISTs) or investigator-initiated studies (IISs) (in cases where the sponsors’ policies allow funding to support agency assistance with manuscripts based on ISTs/IISs), case studies, or review articles, the sponsoring company will receive only a courtesy review of a late-stage draft. Comments from the sponsoring company will be conveyed to the authors, as appropriate, by the medical writer, and the authors may address them at their discretion, while maintaining full editorial control.

The submission process

Although it is preferable for corresponding authors to submit their own manuscripts for publication, MedComm group recognizes that authors often prefer the agency submit on their behalf. MedComm GPP guidelines recommend the following approach for carrying out submissions:

The agency will obtain documented permission from the corresponding author to submit on his/her behalf.

The agency will obtain documented verification that all authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The agency will coordinate obtaining signed forms (e.g., copyright transfer, disclosure; see Conflicts of Interest/Financial Disclosures) from all authors and will get permissions for tables and figures as needed.

Online submission (currently the predominant method of submitting manuscripts and abstracts): When the agency submits online, it does so with the full knowledge and consent of the corresponding author, using the e-mail and log-in information provided by the author, agreeing to all conditions of submission, and approving the submission on behalf of the author.

Alternatively, the agency can make all preparations for online submission, then transfer the responsibility for approving the submission to the corresponding author. In this situation, the agency would populate all information screens and upload files but would not complete the submission; the author would be required to go online, review uploaded materials, and approve or change the final submission as appropriate.

Hard-copy submission: The agency may assist the corresponding author by preparing a complete package for submission. The submission package will contain the manuscript, artwork, and cover letter previously developed in collaboration with and approved by the author, as well as any required forms and permissions; the corresponding author will review these materials, sign the letter and forms, and forward the package to the journal.

Access to data

Authors must have a deep understanding of the study they are reporting. This understanding cannot be attained without access to the complete and final relevant study reports (for company-sponsored clinical trials, the clinical study report [CSR]), along with supporting tables, appendices, and study protocol, which together should provide sufficient detail for authors to appreciate fully the nuances of the study and to allow a comprehensive dialogue among the co-authors regarding the data to include and conclusions to be drawn.

Access to ‘raw’ (source) data is not routinely necessary or warrantedCitation13. ‘Raw’ data are defined as ‘stand-alone’ tables, figures, or listings generated from a clinical database and provided without explanatory narrative on the methods used to generate those data. However, if authors have questions about the data that cannot be answered by information in the study report, MedComm GPP guidelines recommend that the medical writer initiate (and facilitate, as needed) a dialogue between the authors and the trial sponsor to resolve such questions. If requested, the sponsor should provide source data to the authors.

Medical writers who are drafting a manuscript, abstract, or presentation should also have access to the final study report. ISTs/IISs and case studies/series present particular challenges because they may not have a formal protocol (for case studies) or CSR, and the availability of data depends on the individual authors/researchers. Thus, MedComm GPP guidelines recommend the following approach:

When the agency is assisting in the de novo development of a data-driven publication, full access to original data (in the CSR, if such exists), supporting tables, appendices, and study protocol is essential.

If the agency is not able to obtain full, original data for a publication upon request, this limitation should be clearly documented in communications with the company sponsoring the publication. The medical writer cannot ensure scientific accuracy when using only secondary information/data sources.

Honoraria

MedComm group believes that honoraria should not be provided for authors of publications, regardless of publication type. The development and dissemination of articles, abstracts, and congress presentations that report new data or educate peers on important aspects of clinical care is a fundamental aspect of academic medicine that should be conducted without financial incentive. Further, such payments could create the perception of undue influence by the sponsor on the publication's content. Thus, MedComm GPP guidelines prohibit remuneration on behalf of the sponsoring company for authoring a manuscript or other publication.

Conflicts of interest/financial disclosures

In keeping with MedComm group's commitment to transparency in biomedical publications, MedComm GPP guidelines support full disclosure of any possible conflicts of interest (COI).

The agency will adhere to the guidelines provided by the journal or congress regarding disclosure of possible COI.

The agency will inform the authors and the sponsoring company about COI requirements and facilitate author compliance by providing all necessary forms to the authors and coordinating their completion and transmission to the journal or congress.

Although the agency will exercise due diligence in advising authors of guidelines and assisting with collecting and collating the forms, MedComm GPP guidelines recognize that compliance is ultimately the authors’ responsibility.

Policy on conflicts with MedComm GPP guidelines

Conflicts regarding the MedComm GPP guidelines may arise between the agency and journals/congresses, sponsoring company, or authors. Because MedComm GPP guidelines provide guidance and recommendations rather than mandates, the agency will consider any conflicts on a case-by-case basis. However, in negotiations among stakeholders during the publication process, the agency will always be guided by the principle of transparency in publication.

Agency vs journal/congress: The agency will follow journal/congress requirements.

Agency vs sponsoring company: To minimize potential conflicts, the agency will, from the beginning of a relationship, inform sponsoring companies of its commitment to good publication practices and, as part of its services, help educate them on journal and congress guidelines. However, the agency is willing to negotiate on specific issues according to the following guidelines:

The agency will uphold the guiding principles of ethical publication practices and clearly distinguish between these and smaller points of process or language.

Key nonnegotiable elements are transparency in regard to writing/editing support and disclosure of funding source.

Agency vs author: As stated previously, the MedComm GPP guidelines recognize that the authors are fully responsible for the content of their publications. On occasion, however, the medical writer might suspect that data may have been misrepresented, with or without intent. The medical writer should first address the matter with the author for clarification; if no resolution is reached, the agency should bring the matter to the attention of the sponsoring company.

Content confidentiality/security

In providing content development services, agencies are entrusted with confidential data, including proprietary product and marketing information and potentially sensitive patient data.

The agency will abide by the confidentiality statements included in all service agreements and contracts and will ensure that all contractors working on behalf of the agency are apprised of, and will adhere to, these same standards.

If the agency receives IST/IIS data/case reports with identifiable patient information, it will comply with the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) requirements and not disclose or retain any such informationCitation18.

If the sponsoring company has particular concerns about sensitive data, the agency will develop company-specific security measures (which may include physical, technological, and procedural solutions) to address the matter.

Responsibility for implementing MedComm GPP guidelines

Each of the medical communications agencies within MedComm group will distribute the guidelines to all stakeholders – sponsoring companies (both new and current clients), authors, staff, and contractors – and educate them as appropriate on the key principles of the MedComm GPP guidelines.