Abstract

Objective

To study patients’ levels of exercise activity and the clinical characteristics that relate to physical activity and inactivity among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods

A postal questionnaire was administered to 719 patients with COPD in 2010; patients were recruited from the Helsinki and Turku University Central Hospitals in Finland and have been followed since 2005. The questionnaire asked participants about their exercise routines and other daily activities, potential restrictions to exercise, health-related quality of life, and subjective sensations of dyspnea upon exertion.

Results

A total of 50% of the participants reported exercising > 2 times a week throughout the year. The proportion of the exercise inactive patients increased in parallel with disease progression, but the participants exhibited great variation in the degree of activity as well as in sport choices. Year-round activity was better maintained among patients who exercised both indoors and outdoors. Training activity was significantly correlated with patients’ reported subjective dyspnea (r = 0.32, P < 0.001), health-related quality of life (r = 0.25, P < 0.001), mobility score (r = 0.37, P < 0.001), and bronchial obstruction (r = 0.18, P < 0.001). Active patients did not differ from inactive patients in terms of sex, age, smoking status, somatic comorbidities, or body mass index. Irrespective of the level of severity of patients’ COPD, the most significant barrier to exercising was the subjective sensation of dyspnea.

Conclusion

When a patient with COPD suffers from dyspnea and does not have regular exercise routines, the patient will most likely benefit from an exercise program tailored to his or her physical capabilities.

Introduction

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are reported to be less physically active than both their age- and sex-matched healthy counterparts and patients with other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes.Citation1–Citation5 On the other hand, COPD patients who do remain physically active have lower mortality rates, better performance status, and better health-related quality of life (HRQoL).Citation6–Citation10 It is poorly understood why a significant proportion of patients with very severe bronchial obstruction can maintain remarkable levels of physical activity, while others start to lose their exercise capacity at early stages of the disease.Citation6–Citation12 Medical literature on clinical variables associated with physically inactive COPD patients, and data about their willingness to participate in pulmonary rehabilitation programs is sparse. The types of exercise activities that COPD patients favor are also largely unknown.

COPD is the only disease associated with consistently rising hospital admission and mortality rates worldwide,Citation13,Citation14 which results in significant health care costs. Physical inactivity is recognized as a significant risk factor for the exacerbation of COPD, which, in turn, can accelerate the decline of lung function.Citation7–Citation9,Citation15 Pulmonary rehabilitation is shown to be especially effective in preventing the exacerbation of the disease.Citation16–Citation18 There is also cumulative evidence that regular exercise improves patients’ exercise capacity, symptom tolerance, and HRQoL. Evidence pertaining to the positive effects of pulmonary rehabilitation programs on patient’s HRQoL are less abundant.Citation19–Citation23

While the short-term benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation programs are extremely encouraging, more research is needed to assess the long-term results of pulmonary rehabilitation. Previous studies suggest that the positive effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on a patient’s exercise capacity might be lost within a year.Citation19,Citation20 In order to develop more successful pulmonary rehabilitation programs, our aim in the present study was to improve the understanding of COPD patients’ spontaneous exercise routines, the sports they practice, the potential barriers of exercising, and the role of dyspnea in a patient’s capacity to exercise. Since the cohort that was examined in this study also displayed very severe stages of the disease, the overall physical activity among COPD patients was further studied by quantifying their daily activities and overall mobility. Our expectation was that COPD patients exercise less than is recommended according to health-promotion strategies, and that the sports in which they are able to participate are limited. We suspected that severe bronchial obstruction, comorbidities, impaired diffusion capacity, and old age would be the risk factors associated with physical inactivity. We also inquired as to whether the study subjects had previously participated in a pulmonary rehabilitation program or received guidance on physical training, and about their interest in participating in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. These COPD patients are well-defined and have been followed since 2005, which allowed us to add several clinical background variables to the analysis.

Materials and methods

Study population

All of the study subjects were identified from the Finnish chronic airway disease cohort.Citation24 The cohort was recruited from the pulmonary clinics of the Helsinki and Turku University Central Hospitals, Finland, from 2005–2007, and their medical records were retrospectively evaluated starting from the onset of each patient’s disease. Smoking-related COPD or chronic bronchitis was verified for 959 patients. All participants provided their informed consent and the researchers were able to collect and analyze the patients’ medical records; furthermore, patients also agreed to participate in follow-up studies over the proceeding 10 years. A total of 19 participants withdrew from the study. The annual death rate noted in the cohort was 3.6%. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa.

Assessment of physical activity

All surviving and still actively participating COPD patients (n = 827) were mailed a questionnaire asking questions about their exercise activities, time spent on daily life activities, and fitness training between March and April 2010 (a translated version of the questionnaire is available in the ). Following one reminder, the overall response rate was 87% (n = 719). Exercise activity during winter and the rest of the year were inquired about separately (Q1B and Q1A, respectively) by the question: “How often do you exercise at least half an hour at a time with the intensity which makes you at least mildly short of breath and perspire?” Questions Q2 and Q3 were directed to those patients who were still working. Daily life activities and the amount of time spent on household chores and other leisure activities were inquired by question Q4. The questions Q1–Q4 were previously used in the Finnish Health and Functional Capacity Study.Citation25 Question Q6 was modified from the version used in a previous study assessing the barriers of physical activity among elderly adults.Citation26 The British Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale was used to evaluate patients’ subjective dyspnea (Q8).Citation27 Response rates for individual questions varied between 96% and 100% ().

Terms defining patient’s physical activity

Based on the recommendations of the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association,Citation28 patients were categorized as being “physically active” when they reported exercising at least 2–3 times a week and for at least 30 minutes each time, with an intensity causing shortness of breath and perspiration, throughout the year.

The exercise time per week was estimated based on Q1A and Q1B as follows: (1) daily = 210 minutes/week; (2) 2–3 times a week = 75 minutes/week; (3) once a week = 30 minutes/week; (4) 2–3 times a month = 19 minutes/week; (5) a couple of times a year or less = 0 minutes/week.

“Daily life activity” was estimated by summing up the amount of time during which patients performed different domestic/household chores and engaged in leisure activities (minutes/week; Q4). Question Q7 was designed to capture the most profound stages of physical inactivity. The “mobility score” was classified based on either no or minor restrictions in normal life (when the patient is mostly up all day and does light household chores in and outside of the home as needed), or based on the most severe restrictions (the patient rests all day and cannot leave his or her house without help).

Assessment of clinical characteristics

The participants’ HRQoL was assessed using the self-completed, airway-specific AQ20Citation29–Citation32 and generic 15DCitation33 instruments. Each of the hospitals, health care centers, and other outpatient clinics that treated the patients was contacted to gather a complete medical history for each participant. The medical history encompassed the period at least 5 years prior to recruitment. The patients’ social security numbers were used to combine the data from different sources and to link the data to each patient. From the medical records, we identified the results of the latest flow-volume spirometry including bronchodilation tests, and we also acquired information about each patient’s weight, height, and smoking status. The latest spirometry was taken on average 1.7 ± 1.9 (SD) years before recruitment. The diffusing capacity test was only available for a subgroup of patients (n = 294).

The reference values for forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and volume- and blood hemoglobin level-corrected diffusing capacity (DLCOcVA) were validated across large Finnish population samples.Citation34 All of the diagnoses stated in the medical records were carefully evaluated, and particular attention was paid to the time of disease onset and certainty of the diagnosis. The category “coronary disease” included patients who had a myocardial infarct, acute coronary syndrome, or angina pectoris diagnosed by an internist. “Cardiovascular diseases” consisted of patients having one of the following diseases: coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral artery occlusive disease. Chronic alcoholism, alcohol use disorder, and treatment of an alcohol use-related disorder were all categorized as “alcohol abuse.” A wide range of psychotic disorders – including long-lasting clinical depression and anxiety disorders that required regular medication – were categorized as “psychiatric condition.” “Diabetes” included both type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients being treated with medication.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical software packages (version 17.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Comparisons between the mean differences of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the subgroups were conducted using either the Chi-squared test or the Mann–Whiney test. Correlations between ordinal variables were compared using the Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r). The logistic regression analysis was used to determine the independent risk factors associated with physical inactivity. The potential interactions between FEV1 groups and exercise time, exercise activity, daily activity, and mobility were tested with two-way analysis of variance.

Results

Study subjects

The study cohort represented patients with smoking-related chronic bronchitis or COPD across all stages of the disease. The cohort was followed by way of their medical records since the year 2000. During March and April 2010, all participants received a postal questionnaire inquiring about their present exercise routines, sports that they practice, exercise restrictions, other daily activities, their mobility score, and their subjective level of dyspnea. During that time, the mean age in the cohort was 63 years and 40% of the patients were women. A total of 12% of the patients were employed and 52 (7.4%) of them indicated they had a physically strenuous job. The clinical characteristics collected from the medical records are shown in , and the translation of the questionnaire and the patients’ responses are shown in .

Table 1 Comparison of the clinical characteristics between physically active (exercise ≥ 2–3 times a week) and inactive COPD patients

Physical activity among COPD patients

When patients were divided into active and inactive categories based on their exercise routines, common demographic and clinical determinants such as age, sex, comorbidities, or health behavior (continuation of smoking and body mass index [BMI]) showed very little differences between the groups. FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), and diffusion capacity were significantly better in physically active patients (). Exercise activity decreased in parallel with the progression of the disease (P < 0.001) (). The proportion of patients with FEV1 > 80% of the expected value who exercised > 2 times a week throughout the year was 60% (n = 60); with FEV1 65%–80% of expected was 51% (n = 96); with FEV1 40%–64% of expected was 50% (n = 143); and with FEV1 <40% of expected was 33% (n = 35) (P = 0.001).

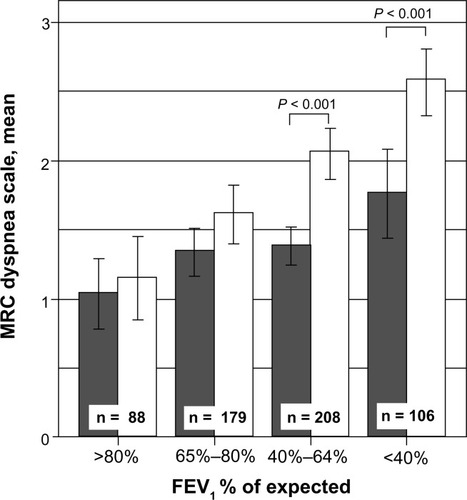

Figure 1 Seasonal changes in estimated exercise time (minutes/week) of patients with different FEV1 % values.

Abbreviation: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Exercise activity was lower during the winter than during the rest of the year across all levels of severity of the disease (). Eighty-seven patients (20%) who exercised actively in the summer became inactive during the winter. Year-round exercise activity correlated significantly with the level of bronchial obstruction (r = −0.14, P < 0.01), diffusing capacity (r = −0.20, P < 0.01), mobility score (Q7) (r = −0.31, P < 0.01), daily life activity (Q4) (r = −0.14, P < 0.01), generic (r = −0.23, P < 0.01) and airway-specific HRQoL (r = 0.19, P < 0.01) (). Overall, the observed correlations were statistically significant, but many of these relationships were rather weak.

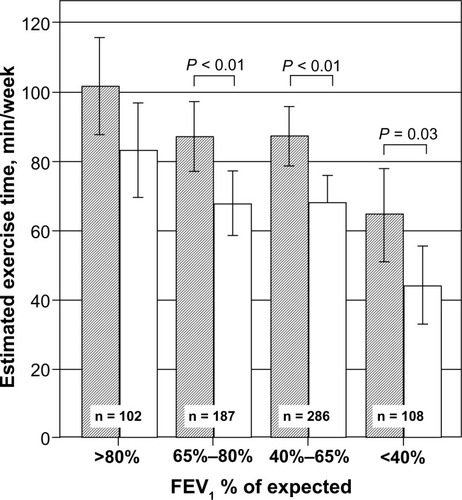

Interest in pulmonary rehabilitation

A total of 233 patients had previously been given guidance for training by health care professionals, and 15% (n = 96) had taken part in a 2-week inpatient (n = 71) or outpatient (n = 25) rehabilitation program (). A total of 14% (n = 94) of all patients had received exercise guidance from physicians; 58 of these patients (18%) were active and 36 (11%) were inactive. A history of competing in sports as a youth was not associated with the maintenance of exercise activity among the COPD patients. Sixty-two percent of the inactive patients compared with 54% of the active patients showed an interest in pulmonary rehabilitation (P < 0.01). Those who were interested were slightly younger (62.9 versus 64.1 years) than those who were not, but no difference was found based on disease severity, sex, or coexisting disease profiles. Whilst 71% of patients reported that COPD significantly restricts their exercising (Q9), the mobility score (Q7) was significantly pronounced within each FEV1 class among inactive patients when compared to active patients (). In daily life activities (Q4) the same trend was observed, even though the difference between active and inactive patients was significant only at the later stages of the disease, particularly when FEV1 ≤ 64% of expected was noted.

Table 2 Comparison of the patient-reported outcomes between physically active and inactive (exercise ≥ 2–3 times a week) COPD patients

Figure 2 Daily life activities (minutes/week) and mobility score in different FEV1 % classes.

Abbreviation: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

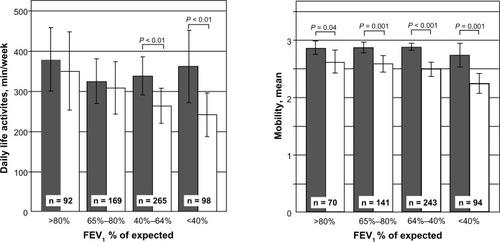

Dyspnea

Subjective dyspnea, assessed by the MRC dyspnea scale, showed constantly stronger correlations with patients’ exercise activity (r = 0.27, P < 0.01), daily life activity (r = −0.37, P < 0.01), mobility (r = −0.46, P < 0.01), airway-related (r = 0.33, P = 0.01), and generic HRQoL (r = −0.40, P < 0.01) levels than the FEV1 or the diffusing capacity corrected for alveolar volume (). When FEV1 was less than 65% of expected, the subjective perception of dyspnea was significantly stronger among inactive than active patients (). Using two-way analysis of variance, we found a significant interaction (P = 0.016) between the FEV1 and activity groups, suggesting that the sensation of dyspnea becomes disproportionally stronger as lung function decreases among the inactive patients when compared to the decrease in lung function among the active patients. The explanatory variables in and were also tested, but no significant interactions between the variables and physical activity were found.

Barriers to exercising

The most frequently reported reasons preventing patients from exercising (Q6) were sensation of dyspnea (66%), pain (36%), other illnesses (42%), discomfort of strenuous exercise (20%), and poor weather (17%) (). The most common exercise-limiting diseases reported were musculoskeletal disorders (n = 92) and ischemic heart conditions (n = 41).

Physically active patients

When the active patients were studied in greater detail, their common factor seemed to be the greater variety of sport activities in which they engaged. When walking was excluded, the active patients (n = 343) practiced a specific sport more frequently than inactive patients (215 patients, or 63%, versus 119 patients, or 33%; P < 0.001). The top 12 sports that COPD patients favored differed greatly in terms of their metabolic equivalents, which are used to compare the intensity between different types of sport activities ().Citation35 Metabolic equivalent values ranged from 2.0 (slow walking) to 6.0 (swimming and skiing). In addition, COPD patients adopted a wide range of sport activities, including skiing, golf, yoga, asahi (Chinese-style gymnastics), badminton, bowling, rowing, downhill skiing, sailing, and hiking. Even though high-intensity activities were practiced less often among patients with severe bronchial obstruction, some patients could still continue swimming, skiing, and participating in ballgames (). A total of 35 patients (32%) with FEV1 < 40% of predicted levels continued to exercise actively.

Table 3 Most popular sports practiced by the COPD patients according to airway obstruction

Clinical variables explaining variability in physical activity levels

In the multivariate model, we found that subjective dyspnea remained by far the most significant marker (OR 7–12, CI 95% 3–38, P > 0.001 at dyspnea levels 3–4) for exercise inactivity when the model was adjusted for sex, age, smoking status, BMI, and common comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, psychiatric conditions, and alcohol diseases. FEV1 explained exercise inactivity only at the late state of the disease (OR 3.5, CI 95% 1.8–6.9, when FEV1< 40% of expected was observed).

Discussion

Main findings

Based on the present study, when COPD patients’ exercise activity was assessed by a self-reported questionnaire, 51% of the study subjects did not achieve the recommended minimum physical activity levels required to promote and maintain their health, as provided by the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association.Citation28 Most interestingly, we found that patients’ perceptions of dyspnea correlated more strongly with their exercise activity, daily life activity, mobility score, and HRQoL than with their level of bronchial obstruction. The subjective perception of dyspnea, captured by the MRC test, was significantly higher among inactive than active patients when FEV1 was less than 65% of expected levels. In the multivariate model, dyspnea remained the most significant explanatory factor for exercise inactivity. The findings are further supported by study designs in which dyspnea was better correlated with patients’ performance during a 6-minute walking test than with a patient’s FEV1 levels.Citation36,Citation37

Even though the proportion of inactive patients increased in parallel with disease progression, the participants showed great variation in activity as well as in sport choices. Sports that COPD patients favored were no different when compared to those favored by others in the population that were age- and sex-matched.Citation38 The great majority of these patients exercised without any assistance from health care professionals, and only a minority of these patients had taken part in a pulmonary rehabilitation course or had received guidance about exercising. Across the whole cohort, 24% of the patients were extremely inactive during the wintertime, exercising only once or twice in the whole season, while the most active participants (10%) exercised daily. Significant seasonal variations in exercise activity were found, and year-round exercise activity levels were better maintained among patients who exercised indoors (36% of the study subjects). Based on demographics, comorbidities, or health behavior, active and inactive patients were very similar.

Limitations and strengths of the study

The study population was large and represented all severity levels of the disease. The gathered clinical variables were valid and comprehensive, but relied completely on retrospective health care data. The assessment of exercise activity was based on two questions, which were used in two previous Finnish Health Surveys in 2000 and 2011, allowing us to compare the results among COPD patients in subsequent studies with members of the Finnish population at large.Citation25 These surveys also employed the more established International Physical Activity Questionnaire with extremely poor response rates. Based on that experience, we decided to use these two basic questions (Q1A and Q1B), which guaranteed us excellent response rates (98% and 97%, respectively), but the answers to these questions contained limited information. In particular, the intensity level of physical training was very roughly approximated.

Since our study relies completely on retrospective lung function data, the spirometry results presented here were not performed at the same time as the questionnaire survey, and this may have weakened the correlations observed in our results. The latest spirometry results were taken, on average, 1.7 years prior to recruitment. However, we had collected an average of 5.5 spirometry tests per patient during the follow-up period,Citation24 and we performed simple sensibility testing using participants’ baseline and bronchodilation spirometry results from different time points; we found that our basic findings did not change (data not shown). Thus, the time difference between the questionnaire survey and the physiological measures may not have played a major role in our results.

In addition to obstruction, restrictive impairment of FVC and thus the FEV/FVC ratio > 0.7 is rather common in COPD.Citation39,Citation40 To avoid exclusion of a significant number of patients with combined lung function impairments from the analysis, we chose to classify the level of airway obstruction solely based on the FEV1 instead of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) measurements. Unfortunately, diffusion capacity was available only for 285 patients, but the preliminary results showed an even smaller correlation between the sensation of dyspnea and exercise activity.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Compared to an epidemiological study conducted in Sweden (n = 526)Citation5 in which 84% of COPD patients were inactive, the Finnish COPD patients reported a higher level of physical activity. The difference can be at least partially explained by the 10-year age difference between the study populations. The patients in the present study have been participating actively for many years, and thus, to some degree, might represent a selected patient population. However, compared to the population from the Copenhagen Heart Study (n = 6568), in which patients participated actively, the exercise activity levels noted in this study were more similar to the levels noted in our study.Citation9 Approximately 19% of the Danish COPD patients showed low, 50% moderate, and 32% high physical activity levels.

Interesting details in the activity profile

Wintertime physical activity was evaluated separately from the rest of the year since COPD patients tend to become more symptomatic in cold and humid weather.Citation41 The winter season before the study began was colder than average, as the temperature in southern Finland was below 0°C for 60 days. Our results confirmed that exercise activity decreased during the winter months when FEV1 was under 80% of expected levels. This might partially explain why year-round activity was better maintained among patients who also practiced indoor sports. A total of 17% of patients reported poor weather as a barrier to exercising; on the other hand, dog-walking was a rather popular leisure activity among 10% of the COPD patients from our study (), suggesting that motivation helps COPD patients tolerate cold weather. A history of competing in sports as a youth was reported in 35% of patients; contrary to findings noted among healthy individuals, no protection against physical inactivity was observed compared to their noncompeting counterparts at the time of the survey.Citation42 It seems that COPD is a strong trigger for physical inactivity even among previous athletes. It is not known whether these former athletes would be more successful at restoring their physical capability and maintaining their exercise activity after pulmonary rehabilitation interventions than those who did not have a history of participating in sports as youth.

Implications for future research, policy, and practice

Dyspnea is the main symptom of COPD. This subjective experience of breathing discomfort is multidimensional, deriving from physiological, psychological, social, and environment factors, and is not directly comparable with physiological measurements.Citation43,Citation44 Limitations in exercise capacity among patients with COPD occur due to ventilatory limitation, dynamic hyperinflation, disturbances in respiratory muscles, ventilatory and vascular capacity imbalance, reduced oxygen uptake and hypoxemia, blood gases, and muscular metabolics.Citation44,Citation45 It is poorly understood why a significant proportion of patients who have very severe bronchial obstruction maintain remarkable levels of physical activity, while others start to lose their exercise capacity at early stages of disease.Citation2,Citation9

Large variations in COPD patients’ exercise capacity have also been described in studies in which patients’ physical activity levels were measured with motion sensors.Citation1–Citation3 Dyspnea was strongly associated with exercise activity among the participants, even when adjusted for FEV1 and other clinically valid variables such as age, sex, comorbidities, smoking status, or BMI. This suggests that COPD either harms cardiovascular exercise capacity by mechanisms other than airway obstruction, or that dyspnea is secondary to physical inactivity and is a marker of overall impaired physical fitness. Pulmonary rehabilitation, combined with pre- and post-intervention physiological measurements for exercise capacity, will be of value in examining the causality between dyspnea and inactivity.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that patients’ subjective sensations of dyspnea may be an indicator that patients’ exercise routines should be assessed. On the other hand, the patients in the cohort currently studied reported dyspnea as the most common barrier to exercise. We should inform inactive patients that dyspnea is not a barrier for exercising and encourage them to exercise despite the sensation of dyspnea. Most of the current rehabilitation programs do not acknowledge patients’ exercise history, nor do they aim to create more tailored programs, which would ultimately support the patient’s own exercise preferences. These programs might achieve better long term results by introducing a variety of indoor and outdoor sports, which may help the patient find the most attractive ways for him or her to train and enjoy exercise.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank clinical research nurses Kerstin Ahlskog, Kirsi Sariola, and Päivi Laakso for their commitment to the study over the years and for skillfully organizing mailing campaigns. The authors also thank Tuula Lahtinen for monitoring the study, and they also thank Dr Ulla Hodgson for providing valuable advice. The COPEX study was supported by The Finnish Social Insurance Institution, and the original clinical follow-up study was supported by the Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUS EVO), University of Helsinki; the Foundation of the Finnish Anti-Tuberculosis Association; the Finnish Allergy Program by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; the Allergiasäätiö ry and Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation; and the Pulmonary Association Heli.

Disclosure

M Katajisto and the other authors did not have a financial relationship with any commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M Katajisto has participated on the Advisory Board for Novartis and Leiras. She has received lecture fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Leiras, and Novartis, and a fee to act as a consultant for Boehringer. Helsinki University Central Hospital has sent her to medical congresses abroad, sponsored by many different pharmaceutical companies. T Laitinen is a member of the Boehringer-Ingelheim, Admirall, and Leiras Advisory Boards. She has received lecture fees, and Turku University Central Hospital has sent her to congresses abroad, sponsored by different pharmaceutical companies. M Kilpeläinen has been a member of the Pfizer advisory board. She has received lecture fees from Boehringer, Pfizer, GSK, and Novartis. Turku University Central Hospital has sent her to congresses abroad, sponsored by different pharmaceutical companies. Ari Lindqvist, Piritta Rantanen, Heikki Tikkanen, and Henna Kupiainen have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Table S1 COPEX questionnaire and response rates among 719 COPD patients

Table S2 Correlation table between clinical variables and specific items in the questionnaire used in the COPEX study

References

- TroostersTSciurbaFBattagliaSPhysical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-studyRespir Med201010471005101120167463

- PittaFTroostersTSpruitMAProbstVSDecramerMGosselinkRCharacteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171997297715665324

- WatzHWaschkiBMeyerTMagnussenHPhysical activity in patients with COPDEur Respir J200933226227219010994

- BossenbroekLde GreefMHWempeJBKrijnenWPTen HackenNHDaily physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewCOPD20118430631921728804

- ArneMJansonCJansonSPhysical activity and quality of life in subjects with chronic disease: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared with rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitusScand J Prim Health Care200927314114719306158

- Garcia-AymerichJSerraIGomezFPfor Phenotype and Course of COPD Study GroupPhysical activity and clinical and functional status in COPDChest20091361627019255291

- WaschkiBKirstenAHolzOPhysical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort studyChest2011140233134221273294

- PittaFTroostersTProbstVSLucasSDecramerMGosselinkRPotential consequences for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients who do not get the recommended minimum daily amount of physical activityJ Bras Pneumol200632430130817268729

- Garcia-AymerichJLangePBenetMSchnohrPAntoJMRegular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort studyThorax200661977277816738033

- WatzHWaschkiBBoehmeCClaussenMMeyerTMagnussenHExtrapulmonary effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on physical activity: a cross-sectional studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177774375118048807

- AgustiACalverleyPMCelliBEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigatorsCharacterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20101112220831787

- Rodriguez Gonzalez-MoroJMde Lucas RamosPIzguierdo AlonsoJLImpact of COPD severity on physical disability and daily living activities: EDIP-EPOC I and EDIP-EPOC II studiesInt J Clin Pract200963574275019392924

- ChapmanKRManninoDMSorianoJBEpidemiology and costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Resp J2006271188207

- BuistASMcBurnieMAVollmerWMfor BOLD Collaborative Research GroupInternational variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence studyLancet2007370958974175017765523

- AnzuetoAImpact of exacerbations on COPDEur Respir Rev20101911611311820956179

- PuhanMScharplatzMTroostersTWaltersEHSteurerJPulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20091CD005305 Review19160250

- ManWDPolkeyMIDonaldsonNGrayBJMoxhamJCommunity pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomised controlled studyBMJ20043297476120915504763

- RubíMRenomFRamisFEffectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in reducing health resources use in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Phys Med Rehabil201091336436820298825

- GuellRCasanPBeldaJLong-term effects of outpatient rehabilitation of COPD: a randomized trialChest2000117497698310767227

- LacasseYMartinSLassersonTJGoldsteinRSMeta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A Cochrane systematic reviewEura Medicophys200743447548518084170

- CasaburiRZuWallackRPulmonary rehabilitation for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2009360131329133519321869

- QaseemAWiltTJWeinbergerSEAmerican College of PhysiciansAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAmerican Thoracic Society; European Respiratory SocietyDiagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory SocietyAnn Intern Med2011155317919121810710

- NiciLDonnerCWoutersEfor ATS/ERS Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing CommitteeAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173121390141316760357

- LaitinenTHodgsonUKupiainenHReal-world clinical data identifies gender-related profiles in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCOPD20096425626219811384

- AromaaAKoskinenSHealth and Functional Capacity in Finland: Baseline Results of the Health 2000 Health Examination SurveyHelsinkiNational Public Health Institute2004 Available from: http://www.terveys2000.fi/julkaisut/baseline.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2010

- RasinahoMHirvensaloMLeinonenRLintunenTRantanenTMotives for and barriers to physical activity among older adults with mobility limitationsJ Aging Phys Act20071519010217387231

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- HaskellWLLeeIMPateRRPhysical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart AssociationMed Sci Sports Exer200739814231434

- BarleyEAQuirkFHJonesPWAsthma health status measurement in clinical practice: validity of a new short and simple instrumentRespir Med19989210120712149926151

- ChenHEisnerMDKatzPPYelinEHBlancPDMeasuring disease-specific quality of life in obstructive airway disease: validation of a modified version of the airways questionnaire 20Chest200612961644165216778287

- HajiroTNishimuraKJonesPWA novel, short, and simple questionnaire to measure health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199915961874187810351933

- MazurWKupiainenHPitkäniemiJComparison between the disease-specific Airways Questionnaire 20 and the generic 15D instruments in COPDHealth Qual Life Outcomes20119421235818

- SintonenHThe 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applicationsAnn Med200133532833611491191

- ViljanenAAHalttunenPKKreusKEViljanenBCSpirometric studies in non-smoking, healthy adultsScand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl19821595206957974

- AinsworthBEHaskellWLWhittMCCompendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensitiesMed Sci Sports Exerc200032Suppl 9S498S50410993420

- SpruitMAWatkinsMLEdwardsLDfor Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study investigatorsDeterminants of poor 6-min walking distance in patients with COPD: the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Med2010104684985720471236

- MarinJMCarrizoSJGasconMSanchezAGallegoBCelliBRInspiratory capacity, dynamic hyperinflation, breathlessness, and exercise performance during the 6-minute-walk test in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116361395139911371407

- Suomen Liikunta ja Urheilu [homepage on the Internet]. [National exercise report]. Helsinki, Finland: Suomen Liikunta ja Urheilu. Available from: http://www.slu.fi/liikuntatutkimus. Accessed 18 November, 2011. Finnish

- AaronSDDalesRECardinalPHow accurate is spirometry at predicting restrictive pulmonary impairment?Chest1999115386987310084506

- WanESHokansonJEMurphyJRCOPDGene InvestigatorsClinical and radiographic predictors of GOLD-unclassified smokers in the COPDGene studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med20111841576321493737

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTJeffriesDJWedzichaJAEffect of temperature on lung function and symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J199913484484910362051

- TammelinTNayhaSLaitinenJRintamakiHJarvelinMRPhysical activity and social status in adolescence as predictors of physical inactivity in adulthoodPrev Med200337437538114507496

- PuhanMAGarcia-AymerichJFreyMExpansion of the prognostic assessment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the updated BODE index and the ADO indexLancet2009374969170471119716962

- NguyenHQAltingerJCarrieri-KohlmanVGormleyJMStulbargMSFactor analysis of laboratory and clinical measurements of dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Pain Symptom Manage200325211812712590027

- PepinVSaeyDLavioletteLMaltaisFExercise capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: mechanisms of limitationCOPD20074319520417729063