Abstract

Aim: Patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) may be vulnerable to changes in healthcare management, safety standards and protocols that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Materials & methods: The REthink Access to Care & Treatment (REACT) survey assessed USA-based patient perspectives on COVID-19-related impacts to their MBC treatment experience between 27 April 2021 and 17 August 2021. Results: Participants (n = 341; 98.5% females, mean age 50.8 years) reported that overall oncology treatment quality was maintained during the pandemic. Delayed/canceled diagnostic imaging was reported by 44.9% of participants while telemedicine uptake was high among participants (80%). Conclusion: Overall, MBC care was minimally affected by the pandemic, possibly due to the expanded use of telemedicine, informing MBC management for future public health emergencies.

Plain language summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced healthcare providers to change the way that healthcare is delivered. These changes could particularly affect people with metastatic breast cancer (MBC), an advanced stage of cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. The authors of this study used a web-based survey to ask 341 volunteers with MBC how the pandemic has affected their cancer treatment. The authors found that people with MBC thought that the quality of their care stayed the same during the pandemic. Most people (80%) surveyed were able to use telemedicine, the remote delivery of care by phone or computer, to replace in-person visits to their doctor. However, almost half of people surveyed reported delays or cancellation of their diagnostic imaging appointments. Overall, this study shows that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect peoples' opinions of their MBC care. Increased use of telemedicine may have contributed to the lack of disruption in care. These findings will help guide MBC care during future public health emergencies.

Tweetable abstract

A survey of patient perspectives on their care for metastatic breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown consistent quality of care. Care delivery adaptations such as telemedicine may be key to maintaining cancer care quality during future public health emergencies.

Substantial changes in healthcare management, safety standards and protocols occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are particularly at risk of pandemic-related negative consequences due to the need for clinical visits, multimodal therapies, potential immunosuppression and compromised support services.

This cross-sectional study used a two-part REthink Access to Care & Treatment (REACT) survey to assess the perspective of patients with MBC on the effects of COVID-19 with regards to their MBC treatment experience.

Data from 341 validated participants (98.5% females; mean age 50.8 years) revealed that patient-reported overall quality of oncology treatment remained about the same during the pandemic.

Telemedicine uptake was high among participants (80%); replacement of in-person visits with telemedicine was the most reported change to regular clinical checkups and mental health visits due to the pandemic.

However, 44.9% of participants reported that diagnostic imaging appointments were either delayed or canceled.

During the pandemic, 48.1% of participants reported disease progression.

Overall, participants perceived that the management and treatment of their MBC were minimally disrupted by the pandemic, likely due in part to the utilization of telemedicine.

While these findings can inform MBC management decisions during future public health crises, future studies should solicit perceptions of care from more diverse patient populations.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, was declared a public health emergency in the USA on 27 January 2020 [Citation1]. By 30 September 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic had resulted in over 600 million confirmed cases with over 6.5 million deaths worldwide, along with significant advances in vaccination with over 12 billion vaccine doses administered, according to the World Health Organization [Citation2]. The pandemic and the societal responses to it, including quarantining and social distancing, greatly strained numerous aspects of the healthcare system [Citation3]. These pressures forced clinicians to adopt new protocols for safely interacting with patients and managing their treatment [Citation4,Citation5]. Ensuring safe clinical interactions is particularly important for patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC), given that many are considered high-risk for severe COVID-19 infection due to comorbidities, advanced age, and/or side effects related to their antitumor therapy (e.g., drug-induced immunosuppression) [Citation3,Citation4,Citation6]. Several organizations developed guidelines for treatment during the pandemic that included consensus-based recommendations for prioritization and treatment of breast cancer by severity (e.g., stage of disease, symptom burden, multiple comorbidities) and potential therapeutic efficacy [Citation4–7]. These guidelines suggest precautionary measures, such as prioritizing outpatient healthcare encounters via telemedicine, prescribing neoadjuvant therapy in lieu of upfront surgery, and adjusting systemic therapy regimens, aiming to reduce contact within the healthcare setting and thus exposure to COVID-19, and to reduce the incidence of adverse events [Citation4–6,Citation8].

The recent advances in COVID-19 control and the lifting of emergency protocols provide an opportunity to assess and modify patient management strategies to optimize clinical protocols in oncology care for future public health emergencies [Citation9,Citation10]. Early evidence indicates that pandemic-related changes in the management of gynecologic cancers have had a negative effect, including provider-initiated visit cancellations, delays in screening and/or surgery and treatment modifications [Citation9]. In addition, surveillance of new treatment initiation in patients with MBC during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA suggests initial shifts in the types of therapies being prescribed [Citation11]. However, detailed information from the patient's perspective about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on treatment management, healthcare visits, disease monitoring and daily living is limited, with available reports describing treatment delays and negative effects on emotional and mental health regarding fear of infection risk and worsening of disease [Citation12,Citation13]. Further investigation into the effects of COVID-19 on patients with MBC is necessary to understand the degree to which shifts in treatment occurred and how these potential shifts affected treatment for MBC in this at-risk population [Citation12,Citation13]. With this understanding, any adaptations necessary to improve the quality of care until and/or after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides can be determined. To address this objective, this study collected data via the REthink Access to Care & Treatment (REACT) survey completed by patients with MBC enrolled in MBC Connect, a patient registry created and managed by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation on behalf of the Metastatic Breast Cancer Alliance and operated by Greenphire, LLC (via their acquisition of Medaptive Health). The survey captured experiences with MBC treatment, disease management and daily living activities from the patients' perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we present the patient-reported impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on MBC management.

Materials & methods

Study design

This study consisted of a two-part cross-sectional, observational survey, REACT, delivered via web or mobile app and was completed by adults with MBC living in the USA, who were enrolled in the MBC Connect patient registry.

The MBC Connect registry is a patient-powered research registry owned by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation on behalf of the Metastatic Breast Cancer Alliance and operated by Greenphire, LLC (via their acquisition of Medaptive Health). The registry runs on the Greenphire Patient-Powered Research Registry platform, which provides the ability to engage participants. Patients enrolled in MBC Connect voluntarily completed baseline surveys that documented demographic and treatment data as part of their engagement with the registry. The REACT survey was built on top of MBC Connect, leveraging a subset of the information collected by the baseline MBC Connect surveys and adding two additional surveys that go beyond that baseline. The two-part REACT survey focused on COVID-19-related questions: Part 1 covered online services used and perceived effects of COVID-19-related changes in care and MBC treatment plans; Part 2 captured information about patient experiences with COVID-19 testing, vaccination and infection, as well as patient demographics, health and MBC history. Questions concerning financial hardship were adapted from the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) patient-reported outcome measure to fit the context of the pandemic [Citation14]. The study explored, through a secondary analysis of patient-reported data, the patient experience with MBC treatment and life during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA (from March 2020), and aimed to inform best practices from the patient's perspective. The study protocol specified that the survey would be open for approximately 1 month, but allowances were made for timeline variation depending on sample accrual and launch timing regarding COVID-19 trends in the USA. This study was approved by an independent Institutional Review Board (IRB) ‘North Star Review Board’. As this study involved anonymized structured data, which according to applicable legal requirements do not contain data subject to privacy laws, obtaining additional informed consent from patients was not required. Informed consent for participating in MBC Connect and associated surveys was completed during enrollment into the MBC Connect registry and covered under the MBC Connect main protocol.

Participants & study recruitment

Adult patients with MBC residing in the USA and who were enrolled on the MBC Connect registry were initially contacted to participate in the REACT surveys. Eligible MBC Connect participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. Patients were also recruited to join the MBC Connect registry, and subsequently the REACT surveys, via networks of nonprofit members of the MBC Alliance, a social media and public relations campaign, and through oncology offices that volunteered to participate. The MBC Connect launch and ongoing recruitment campaign featured known advocates living with MBC, patients with a strong voice in the MBC community, medical researchers active in MBC research, press releases, fact sheets, postcards, video vignettes and information provided by MBC Alliance member organizations. All participant-facing recruitment materials were approved by the IRB prior to use.

Data collection

To capture information at the time of enrollment in MBC Connect, participants completed short surveys via the MBC Connect digital platform. MBC Connect is a patient experience registry in which patients share information about their diagnosis and treatment history by responding to surveys and entering their treatment profile. The surveys contained questions about demographics, disease history, genetics and tumor mutations, daily living activities and clinical trial experience. The treatment profile was obtained by entering information in a treatment profile tab. The survey questions and treatment profile could be completed over multiple sessions and updated at any time. The information provided by the participants was stored within a secure database and the user had the option to opt-in or -out to completing additional surveys provided by researchers.

All study data were collected from the MBC Connect enrollment and REACT surveys, including demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment profile and COVID-19 survey data. Demographic and clinical characteristics collected included age, gender, ethnicity, race, geographic region, marital status, highest level of education, type of health insurance, annual household income, comorbidities, stage at initial diagnosis, time since first breast cancer diagnosis, hormone receptor status, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status, germline genetic mutations (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2), ability to pay for MBC care, and change in out-of-pocket medical expenses for MBC. Of note, the survey design allowed participants to select multiple answers for the receptor questions, if applicable, for their metastatic biopsy.

Data collected regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic included changes in cancer treatment and healthcare utilization, as well as COVID-19 vaccination, diagnosis and treatment. Delay, cancellation, and location changes (provider- or patient-initiated) of scheduled tests, monitoring appointments, procedures and other healthcare visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic were captured, as was the use and usefulness of telemedicine, email, SMS and text message encounters with providers. Changes in cancer treatment schedule, dose, or type were recorded. Delays or avoidance of urgent care or emergency room visits, and changes in services for transportation, daily needs, errands, emotional support, caregiver support and financial needs were also included.

The technical team detected bot activity by creating a cluster score and digital ‘fingerprint’ for each answer to a survey. When the survey answers were sorted by cluster score, the result was identification of clusters of multiple identical fingerprints corresponding to identical answers to a survey. Because of the size of the surveys, the probability of identical fingerprints occurring with real users is vanishingly small, enabling the team to identify with high accuracy situations where a bot was used to rapidly complete a survey multiple times. Further evidence of bot activity included that the answers within these clusters always arrived within a few seconds of each other. These responses were excluded from the analysis.

Data analysis

Data from survey questions evaluating patient-reported experiences of MBC treatment and management during the COVID-19 pandemic were summarized. All study variables were analyzed descriptively and summarized by mean values, medians, ranges and standard deviations of continuous variables of interest and frequency distributions for categorical variables.

Results

Participant characteristics

Between 27 April 2021 and 17 August 2021, a total of 532 registry participants completed the two-part REACT survey. Of the 532 participants, 341 were included in the study (mean duration from MBC diagnosis to completion of REACT survey: 4.2 years [range, 0.09 to 25.4 years]). The remaining 191 patients were excluded from the study due to the detection of fraudulent bot activity. Participant-reported characteristics are presented in . Most participants were females (n = 336; 98.5%); the remainder were males (n = 4; 1.2%) and transgender/nonbinary (n = 1; 0.3%). Ages of participants ranged from 28.9 to 77.7 years, with a mean of 50.8 years. The majority (n = 300; 88.0%) had completed college education and 72.8% (n = 247) had a bachelor's degree or higher. The majority of participants reported annual household incomes of $50,000 or more (n = 243; 71.3%); 43.7% (n = 149) reported annual household incomes of US$75,000 or more, which exceeded the 2021 median US household wage ($67,000/year) [Citation15]. More than 30% (n = 112) had annual household incomes of ≥$100,000. Most participants (98.8%; n = 337) reported having medical insurance. The location of participants spanned 44 states. The most common MBC receptor type reported was estrogen receptor-positive (n = 249; 73.0%); 60.4% (n = 206) of participants were progesterone receptor-positive, 61.3% (n = 209) were HER2-negative and 7.0% (n = 24) of participants had triple-negative MBC (TNBC).

Table 1. Participant self-reported demographics.

COVID-19 vaccination & infection

Most participants (n = 261; 76.5%) received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination, and another 3.5% (n = 12) reported future plans for vaccination. Approximately 20% (n = 68) did not have a COVID-19 vaccination, and reported no plans to do so, or declined the vaccine when offered. The majority of participants (n = 258; 75.7%) were tested for COVID-19 infection, 7.8% (20/258) of which reported a positive test result. In total, COVID-19 infection was confirmed by a healthcare professional (HCP) for 16 (4.7%) participants; three went on to receive treatment for COVID-19. The majority of participants with an HCP-confirmed positive COVID-19 test result (10/16; 62.5%) reported that their COVID-19 infection interfered with their MBC treatment (disrupting treatments, scans, and/or access to treatment).

Self-reported impact of COVID-19

Effect on surveillance, treatment & care appointments

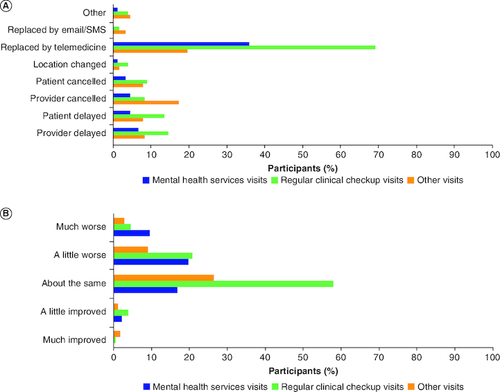

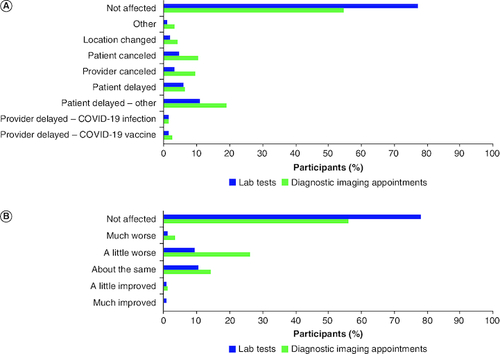

Most participants reported that the periods of January–June 2020 (n = 177; 51.9%) and November–December 2020 (n = 150; 44.0%) were the most challenging during the pandemic. Changes to scheduled clinical visits due to the pandemic were reported by 185 (54.3%) participants; 178 participants reported details on the type of change to their scheduled visit. The most reported change to regular clinical checkups and mental health visits was the replacement of in-person visits with telemedicine (69.1% [123/178] and 36.0% [64/178], respectively; A). Personal- or provider-initiated delays of regular clinical checkup visits were reported by 13.5% (24/178) and 14.6% (26/178) participants, respectively. Personal- or provider-initiated delays of mental health visits due to the pandemic were reported for 4.5% (8/178) and 6.7% (12/178) of participants, respectively (A). Most participants reported that they were not affected by the changes to regular clinical checkups; however, changes to mental health visits did have a slight negative impact on patient experience (B). Diagnostic imaging appointments and scheduled lab tests were changed due to the pandemic for 44.9% (n = 153) and 22.3% (n = 76) of participants (A). However, most participants reported that they were not affected by the changes in the diagnostic imaging and lab appointments as a result of pandemic (B). Notably, some diagnostic imaging appointments (9/153; 5.8%) were delayed by the healthcare provider to avoid false positives as a result of inflammation/immune activation due to receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.

Figure 1. Changes in scheduled visits and effects on patient experience.

(A) Participant-reported changes in scheduled visits due to the pandemic, and (B) effects of changes in scheduled clinical visits on patient experience (n = 178)*†.

*185 participants reported a change to a scheduled clinical visit due to the pandemic, 7 of these participants reported an unspecified change, with no data collected about the type of change or the experience and thus were excluded from this cohort.

†Results may total >100% because participants could select ≥1 choice.

Figure 2. Effects of COVID-19 on laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging appointments.

Participants reported changes, delays and/or cancelations of laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging appointments that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how they were affected by this. (A) COVID-19 pandemic effects on laboratory and diagnostic imaging appointments* (n = 341). (B) Participant experience of changed laboratory and diagnostic imaging appointments* (n = 341).

*Results may total >100% because participants could select ≥1 choice.

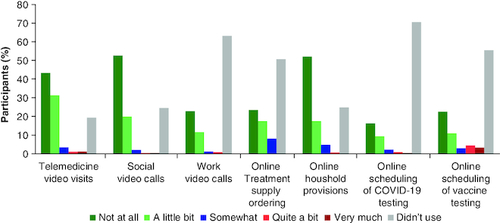

Most participants did not report a change to their treatment due to the pandemic ( & ). Telemedicine utilization was high, with 80.6% (n = 275) of participants having engaged in virtual health visits. The majority of those who used telemedicine (255/275; 92.7%) reported little or no difficulty with the technology (). During the emergency suspension of interstate regulations, a number of participants pursued consultation with oncologists out of state (n = 43; 12.6%) and/or outside their normal geographic area (n = 32; 9.4%; ). Disease progression during the pandemic was reported by 48.1% (n = 164) of participants.

Figure 3. Level of difficulty of using of online services.

Participants (n = 341) rated how difficult (not at all – very much) they found using different types of online services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants who did not use online services could select ‘didn't use’.

Table 2. COVID-19 effects on treatment.

Table 3. Patient experience of treatment changes due to COVID-19.

Table 4. Patient experience of expanded opportunities due to telemedicine and relaxed regulationsTable Footnote†.

Self-reported impact of COVID-19 on daily living activities, financial issues, employment & support services

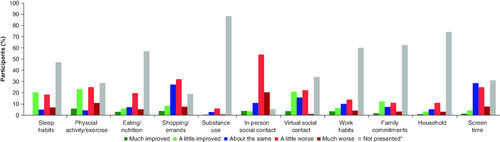

Similar proportions of participants reported most daily activities and lifestyle habits were ‘much improved’ or ‘much worse’ during the pandemic, with less than 5% difference between ‘much improved’ or ‘much worse’ responses for eating/nutrition, shopping/errands, substance use, virtual social contact, work habits, family commitments and household (). A similar percentage of participants reported physical activity/exercise to be ‘a little improved’ or ‘a little worse’ (~25% each). Screen time, in-person social contact, eating/nutrition and shopping/errands all tended to be negatively affected during the pandemic. Just over half of the participants (n = 176; 51.6.%) reported no financial-related impact on MBC treatment, and only 7.3% (n = 25) reported ‘quite a bit’ and ‘very much’. Of the 150 participants who were employed at the start of the pandemic; 54.0% (81/150) reported that the pandemic affected their employment per the reasons listed in . Just under half of the participants reported that their support systems were affected by the pandemic (n = 162; 47.5%). The support system most impacted was support with errands, with 25.5% (n = 87) of participants reporting that their support was at least a little worse. The support system least impacted was transportation with 13.5% (n = 46) of participants reporting that their support was at least a little worse ().

Figure 4. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on daily living activities.

Participants (n = 341) selected daily activities that had changed during the COVID-19 pandemic (11 daily activities were presented for selection within the survey). Participants also rated how the change in daily activities had changed their well-being (much improved – much worse).

*Participants who were not presented with a given question, due to the operation of skip logic based on their previous answers, are included in the data as ‘Not presented’.

Table 5. Effects of COVID-19 on participant employment.

Table 6. Patient support changes during COVID-19.

Clinical trial experience

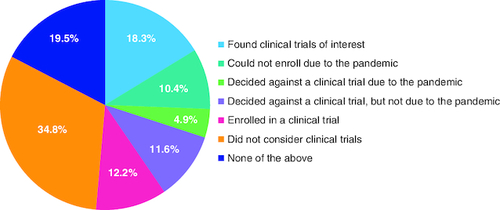

Among the participants who were actively enrolled in a clinical trial during the pandemic (n = 87; 25.5%), 26.4% (23/87) reported changes to their trial due to the pandemic. Types of changes that were reported included the following: pausing trial, protocol modified, visits moved to telemedicine, testing paused or delayed, medication paused, trial extended and other. Half of clinical trial participants reported a worse experience due to these changes. Among participants who reported disease progression (n = 164), 12.2% (20/164) subsequently enrolled in a clinical trial, while 15.3% (25/164) declined and/or were unable to participate in a trial due to the pandemic ().

Figure 5. Clinical trial experience of participants with progression.

Participants who had MBC disease progression reported on their experience, if any, of clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 164)*.

*Results may total >100% because participants could select ≥1 choice.

MBC: Metastatic breast cancer.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the delivery of oncologic care with some cancer types, including breast cancer, having longer term declines in new diagnoses than other cancers, as well as more lasting impacts on treatment delivery [Citation10,Citation16–18]. This study reports survey data obtained from patients with MBC to describe patient perspectives of the pandemic-related impact on MBC treatment and daily life. The complexity of cancer treatments can potentially increase the vulnerability of this population during public health emergencies, and patients with MBC are particularly at risk of negative consequences due to the need for clinical visits, multimodal therapies, potential immunosuppression and compromised support services [Citation5,Citation6,Citation19]. In this study, we found that MBC treatment and management remained unaltered for the majority of patients. Telemedicine uptake was substantial, reaching 80% among survey participants and may have contributed to the lack of disruption in care. These data align with the recommendations from the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium and other expert opinions for use of telemedicine for most healthcare encounters and in-person clinic visits only for unstable and/or symptomatic MBC during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation4,Citation5]. For the small number of participants who tested positive for COVID-19 during the study, the majority encountered treatment disruptions.

Most study participants reported little to no change in utilization of support systems. It should be noted that most of the participants in this study reported that their existing support systems did not noticeably waiver from pre-pandemic levels during the course of the survey. The median income of the participants was higher than the US median [Citation15], which may have mitigated the impact of the pandemic on their support systems. However, patients and healthcare providers need to plan for the possibility of living within a pandemic environment for the long term, including a realistic determination of the acceptable risk levels to both providers and patients [Citation9,Citation10,Citation20]. Given the persistently higher risk level, risk-sharing between the patient and the healthcare system will be required, as will the need to compensate for dwindling healthcare resources by determining potential treatment alternatives or possibly modifying the overall treatment plan.

Although the overall findings are reassuring, this study also provides insights from disruptions in MBC care that may inform the approach to MBC management in future public health emergencies. In particular, MBC treatment was disrupted in participants who tested positive for COVID-19. For example, treatment visits that included chemotherapy and targeted therapy were reported as changed most frequently. With regard to differences in receptor status and changes in visits and progression, it is more likely that participants who reported to have ER+ or TNBC MBC were receiving oral therapies (e.g., hormone modulation with targeted therapy and capecitabine) than those who reported to have HER2+ MBC (e.g., iv. trastuzumab), possibly leading to less disruption of treatment delivery in participants with HER2- MBC than those with HER2+ MBC who more frequently had clinical visits changed to ensure treatment was administered.

The high percentage of participants with de novo disease within the analysis is reflected in the younger age of the population than the average patient with MBC [Citation21]. De novo presentations are mostly young premenopausal patients with aggressive tumor biology, primarily HER2+ or TNBC types [Citation22,Citation23]. This dataset reflects an overrepresentation of HER2+ patients, and an underrepresentation of HR+ patients and TNBC relative to the general MBC population in the USA [Citation22,Citation24]. Disease progression during the period of the pandemic was reported by 48% of participants. The effects of relaxed consultation and trial rules (e.g., telemedicine use) and the data reported support a case for permanently allowing cross-state virtual consultations for patients with MBC. Other studies of patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic have also reported high utilization of telemedicine and generally show that quality of care can be maintained or improved in multiple realms (e.g., post-surgical wound healing, physical activity, access to care) during times of compromised healthcare resources [Citation25–27]. Continued advancements in telemedicine have the potential to improve care access and the management of patients with MBC with the added benefit of conserving healthcare resources, especially in future public health emergencies [Citation16,Citation26,Citation27].

The most important strength of this study was the ability to collect real-time data from MBC Connect and the REACT survey. The analysis was limited by data-capture from a voluntary cross-sectional survey of participants; therefore, the data may not be generalizable across the US population with MBC. The population was 90% White, the majority of participants were college-educated, and just under half had an income exceeding the US median [Citation15]. Survey participation required app/computer literacy, which may also influence the generalization of the study findings. Furthermore, in a portion of survey responses, fraudulent bot activity was detected, and these surveys were excluded from the dataset. This is a technological problem that requires attention in public health research studies to better ensure online survey data integrity. Future studies are needed to better understand whether the impact of the pandemic on cancer care varies by race, socioeconomic status and other factors. Data were self-reported by the patient with no additional checks against data sources. Survey participants had a wide range of duration from MBC diagnosis to completion of the survey; the time since MBC diagnosis may have had an impact on patient responses as a more recent diagnosis may result in more distress to patients to have changes in care, rather than later once established on a treatment regimen. Finally, the responses are based on patient reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic within a recall period of approximately 12 months. This longer recall period may result in recency bias due to differences in the accuracy of recalled experiences and/or events.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings indicate that most participants perceived minimal disruption to MBC care during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may be attributable to the high utilization of telemedicine services. Among participants reporting a negative impact of the pandemic on cancer care, delays in diagnostic imaging appointments and chemotherapy, and the inability to participate in clinical trials were most commonly reported. Although some participants leveraged the relaxed interstate licensure guidelines to consult with oncologists outside of their geographic regions, this was not common. Support systems were unaffected by the pandemic for most participants. Future studies are warranted to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on MBC care in underrepresented populations and to further interrogate the barriers identified in this study. Ultimately, these findings could inform the approach to improve MBC management and to establish best practices for holistically supporting patients with MBC during future public health emergencies.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting/revision of the article. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Financial disclosure

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. N Iyengar receives consulting fees from Pfizer, Novartis, TerSera Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics and research funding (to institution) from Novartis and SynDevRx. C Chen, J Doan and SK Kurosky are employees of and stockholders in Pfizer Inc. C Williams, M Rogan, J Block and M Ebling were employees of Medaptive Health (now Greenphire LLC) who was funded by Pfizer Inc to conduct the study. L Campbell, S Mertz and T Pluard have no conflicts to report. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Writing disclosure

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by J Tieber of ICON plc, USA, and Z Kelly and K Woolfrey of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc., Newtown, PA, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice 3 guidelines, and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Ethical disclosure

As this study involved anonymized structured data, which according to applicable legal requirements do not contain data subject to privacy laws, obtaining additional informed consent from patients was not required. Informed consent for participating in MBC Connect and associated surveys was completed during enrollment into the MBC Connect registry and covered under the MBC Connect main protocol.

Data-sharing statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in the REACT COVID-19 survey.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azar II AM. Determination that a public health emergency exists. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, WA, USA (2020). Available at: www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions/phe/Pages/2019-nCoV.aspx

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) (2022). Available at: https://covid19.who.int/

- Ueda M, Martins R, Hendrie PC et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: agility and collaboration toward a common goal. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 18, 1–4 (2020). https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/18/4/article-p366.xml

- Sheng JY, Santa-Maria CA, Mangini N et al. Management of breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: a stage- and subtype-specific approach. JCO Oncol. Pract. 16(10), 665–674 (2020).

- Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ et al. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment, and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. the COVID-19 pandemic breast cancer consortium. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 181(3), 487–497 (2020).

- de Azambuja E, Trapani D, Loibl S et al. ESMO management and treatment adapted recommendations in the COVID-19 era: breast cancer. ESMO Open 5(Suppl. 3), e000793 (2020).

- Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, Fesko Y. Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3(8), e2017267 (2020).

- Garg PK, Kaul P, Choudhary D et al. Discordance of COVID-19 guidelines for patients with cancer: a systematic review. J. Surg. Oncol. 122(4), 579–593 (2020).

- Nakayama J, El-Nashar SA, Waggoner S, Traughber B, Kesterson J. Adjusting to the new reality: evaluation of early practice pattern adaptations to the COVID-19 pandemic. Gynecol. Oncol. 158(2), 256–261 (2020).

- Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 10(11), e043828 (2020).

- Kurosky S, Liu X, Meche A, Levin R, Sullivan A, McRoy L. Abstract PS11-21: first-line treatment trends in metastatic breast cancer before and at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Cancer Res. 81(Suppl. 4), PS11-21-PS11-21 (2021).

- Rodriguez GM, Ferguson JM, Kurian A, Bondy M, Patel MI. The impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer: a national study of patient experiences. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 44(11), 580–587 (2021).

- Papautsky EL, Hamlish T. Patient-reported treatment delays in breast cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 184(1), 249–254 (2020).

- de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer 120(20), 3245–3253 (2014).

- Shrider EAK, Chen MF, Semega J. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020 (2021). Available at: www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html#:~:text=Median%20household%20income%20was%20%2467%2C521,median%20household%20income%20since%202011

- Sturz JL, Boughey JC. Lasting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in the United States. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 32(4), 811–819 (2023).

- Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles JK, Fesko YA. Changes in newly identified cancer among US patients from before COVID-19 through the first full year of the pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 4(8), e2125681 (2021).

- Decker KM, Feely A, Bucher O et al. New cancer diagnoses before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 6(9), e2332363 (2023).

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an International Collaborative Group. Oncologist 25(6), e936–e945 (2020).

- Battershill PM. Influenza pandemic planning for cancer patients. Curr. Oncol. 13(4), 119–120 (2006).

- Mariotto AB, Etzioni R, Hurlbert M, Penberthy L, Mayer M. Estimation of the number of women living with metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 26(6), 809–815 (2017).

- Gong Y, Liu YR, Ji P, Hu X, Shao ZM. Impact of molecular subtypes on metastatic breast cancer patients: a SEER population-based study. Sci. Rep. 7, 45411 (2017).

- Shah AN, Metzger O, Bartlett CH, Liu Y, Huang X, Cristofanilli M. Hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer in young women: emerging data in the era of molecularly targeted agents. Oncologist 25(6), e900–e908 (2020).

- SEER. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer subtypes (2019). Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html

- Ludwigson A, Huynh V, Myers S et al. Patient perceptions of changes in breast cancer care and well-being during COVID-19: a mixed methods study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29(3), 1649–1657 (2022).

- McGrowder DA, Miller FG, Vaz K et al. The utilization and benefits of telehealth services by health care professionals managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare (Basel) 9(10), doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101401 (2021).

- Dietz JR. Editorial: impact of the covid-19 pandemic on breast cancer treatment and patient experience. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29(3), 1502–1503 (2022).