ABSTRACT

The phenomenon of elected representatives ditching the political party on whose ticket they were elected for another party constitutes a problem for representative democracy. Especially in settings where identity politics is reportedly common, it is important to interrogate whether voters simply follow their politicians to a new party. This article examines public responses to party switching in Nigeria, drawing from a nationwide representative survey of 1,023 participants against existing debates on ethno-religious and money politics. The author argues that while identity and money politics do have some influence on electoral choices, Nigerian voters generally disapprove of party switchers, except those with a prior track record of good performance.

Introduction

It is generally understood that there are neither permanent friends nor permanent enemies in politics, but only permanent interests. Shifting political loyalties is therefore a tactic used by politicians to pursue their goals while brokering ephemeral alliances. However, what happens to voters who had elected these politicians on certain party platforms and manifestoes? Do they feel betrayed by their elected representatives jumping ship or do they move along with them? Existing research on party switching in older democracies reveal that voters are often suspicious of party switchers and punish them at the polls (Desposato, Citation2006; Mershon & Shvetsova, Citation2013). In new democracies in Eastern Europe on the other hand, switchers incurred few to no electoral costs because of strongman politics and weak party institutionalisation in the region (Klein, Citation2019; Tavits, Citation2009). From these studies, scholars have made sweeping assumptions that in non-western democracies, switchers can easily drag their constituency to their new camp without attracting any electoral punishment. However, the present author (Agboga, Citation2023) has uncovered that in Nigeria, Africa’s biggest democracy, most voters disapprove of party switching. He found 214 cases of party defection in the country’s federal legislature between 2011 and 2019, and revealed that switchers performed worse than non-switchers in elections, thereby challenging assumptions from some existing research that switchers incur no electoral costs in non-western democracies (Klein, Citation2019; Tavits, Citation2009).

This paper continues from where that research left off by exploring variables such as ethnicity, religion, wealth, and performance which are common talking points in debates and discussions on African politics, but which were not included in the previous quantitative analysis on the electoral performance of switchers in Nigeria. To address this, I conducted a nationwide representative survey with 1,023 participants to probe how these factors influence the choice between switchers and non-switchers, and triangulate the survey responses with existing data, literature, and debates on voting behaviour in Nigeria, and Africa more broadly. I find that co-ethnicity, religion, party identity, and wealth on their own are insufficient – instead, candidates must have a record of delivering public goods in their constituency in order to avoid reproach for switching parties. This suggests that African voters are far more discerning than previous research has acknowledged, employing a complex calculation of the costs and benefits of supporting politicians who switch political parties.

Methodology

I utilised a combination of responses from a 2022 nationwide representative survey in Nigeria comprising of 1,023 participants and evidence from existing literature on the role of ethnicity, religion, and wealth in African politics to foreground factors that influence support for party switching. The nationwide representative telephone survey conducted through NOI Polls in Nigeria involved participants drawn from a sampling frame of over 70 million telephone numbers from the NOI (https://noi-polls.com/) database. I targeted only adult Nigerians (18 years and above) and derived a proportional representation of the six geo-political zones in the country. The survey questionnaire was translated into English, Pidgin, Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba languages, to suit the participant’s preference. The survey results were then triangulated with previous voting patterns in Nigeria to check for social desirability bias in the survey responses. The subsequent section will situate this research amid existing discussions and debates on the role of ethnicity, religion, and wealth in driving voting choices, and tease out the paper’s original contribution to this research area through the use of new data. In addition, as the dust was yet to settle from the 2023 Nigerian general election when this paper was written, my analysis draws on incidents of switching and voters’ responses from 2011 to 2019.

Ethnic and religious politics, and party switching

Many scholars argue that most African political parties have strong ethnic ties evidenced by their regional and ethnic foundations which similarly serve as their source of strength and support (Ekeh, Citation1975; Ezeibe & Ikeanyibe, Citation2017; Horowitz, Citation2000; Manning, Citation2005; van de Walle, Citation2003). The ethnic character of African parties has been attributed to the (re)introduction of democracy from the 1990s where ethnic pressure groups metamorphosed into political parties after African governments were pressured to undertake multiparty elections (Manning, Citation2005). Carey (Citation2002, p. 19) traces this further back to the colonial era, arguing that colonialism set the stage for ethnic politics in Africa by first allowing ethnic and regional parties and by hindering ‘the formation of national parties that could have brought together different groups in society’.

However, other scholars have argued that ethnicity is only one of many factors influencing African parties, and African political life in general, finding variations among African states (Cheeseman & Ford, Citation2007; Elischer, Citation2013). The picture is further complicated by the existence of a large block of swing voters in many African states who do not simply vote according to ethno-religious lines but consider other factors such as the state of the economy and the provision of public goods (Lindberg & Morrison, Citation2005; Weghorst & Lindberg, Citation2013). Similarly, many African parties have orchestrated power-sharing agreements and embraced multi-ethnicity in order to improve their nation-wide appeals, with the result that reducing African party politics to simple ethnic lines is at best reductionistic – ignoring evidence of swing voters, multi-ethnic alliances, programmatic politics, and variation among African states.

Nonetheless, parties have their regional strongholds which often coincide with ethnic groupings where they normally win elections (Wahman & Boone, Citation2018). Voters in the strongholds are usually more partisan, and vote along identity cleavages to protect their interests (Lindberg & Morrison, Citation2005). In these party strongholds, switching out of the popular party is expected to negatively affect (re)election chances, since voters are invested in the party and therefore less likely to move. In Nigeria, voters in the south-east and south (Niger Delta) have often voted for the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), with the All Progressive Congress (APC) struggling to get even as little as 10% of the votes (Angerbrandt, Citation2020). This may be a result of the PDP sponsoring Nigerian presidents from the South, making the party popular in the region. The APC on the contrary is often viewed with suspicion in the south as its political appointments have mostly favoured the north under President Buhari’s administration. BusinessDay (Citation2017) released a controversial report showing that President Buhari appointed 81 northerners among his 100 appointees as of 2017, and another report from the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR) revealed that 75% of the recruits into state security services as of 2021 were of northern extraction (ICIR, Citation2021).

To fuel suspicions of ethnic appointments, President Buhari who once said he was ‘for nobody and everybody’ at his inaugural speech, backtracked a few months later by disclosing that ‘the constituents [that], for example, gave me 97% [of the votes] cannot in all honesty be treated on some issues with constituencies that gave me 5%’ (Sahara Reporters, Citation2015). This suggests that what is often labelled ethnic voting is ‘defensive voting’ aimed at protecting group interests, where coethnics are voted into office not just because they are coethnics, but to protect group interests in settings with a history and widespread expectations of state bias. According to Carlson (Citation2015, p. 354), ‘voters prefer coethnic politicians because they expect coethnics to provide better future economic and political goods’, especially because they do not trust outsiders to channel these to them given a history of prior ethnic discrimination.

While candidates’ ethnicity is less of an issue during constituency-based elections because those running are likely to be from the same or neighbouring ethnic groups, the regional/ethnic appeal of the candidates’ political party as opposed to the ethnicity of the candidates themselves could be a major deciding factor here. The rotation of power among ethnic groups is a discussion often had more at the national rather than the constituency level, thereby differentiating the salience of ethnicity at the national and regional levels. This rotation of power has also been identified in other African states, with Cheeseman (Citation2010, p. 146) observing that ‘in highly diverse countries such as Kenya and Mali, successful parties must be multiethnic coalitions in which the presidential candidacy rotates among the different groups’. While this is expected at national level, the salience of ethnicity takes on a different nature in constituency-based elections where candidates are likely to be from the same or neighbouring ethnic groups. As a result of their ethnic homogeneity, the regional/ethnic popularity of their party becomes the leverage that one candidate has over another.

Apart from a ‘mixed state’ like Lagos with a diverse population, the distribution of seats among candidates from different ethnic groups is often less common in constituency-based elections. In 2015, three Igbo politicians won their House of Representative elections in Lagos, a Yoruba but urban state, representing constituencies with a large non-indigenous merchant population (PM News, 31 March Citation2015). Nonetheless, the contests for constituency seats around the country are generally among coethnics. For instance, the election for the seat of Kwara West Senatorial District would likely be contested by candidates from Kwara who were born and/or have lived in that constituency for years. The ‘son of the soil’ mentality, which is widely held in Nigeria and Africa more broadly (see Boone, Citation2017), though not backed by law, expects candidates to be from the constituency they are contesting in. As Boone (Citation2017) argues, voters are more at ease with their coethnics than outsiders amid intergroup competition for resources, similar to the argument made by Posner (Citation2005) and Carlson (Citation2015) on state bias and the distribution of public goods. In other words, coethnics, or in this case, ‘sons (and daughters) of the soil’ are expected to protect ethnic interests where there is suspicion of state discrimination, leading to their emergence as top candidates for constituency seats.

In sum, ethnicity has a complicated role in Nigerian politics, and African politics more broadly. While it has often been suggested that African voters simply vote for their coethnics, the suspicion of state bias and the belief that coethnics are more likely to channel economic and political benefits back home amid interethnic competition for these resources, could offer a more nuanced picture. But, I argue that ethnicity has different degrees of salience at the national and constituency level, where power rotation is expected in the former, and the regional/ethnic reputation of candidates’ parties become important in the latter. However, I acknowledge that this could be different in mixed constituencies with a diverse population, especially those in urban areas, with Lagos as a case in point where Igbo traders contested and won seats in Yorubaland. Rather, the party affiliation of candidates is crucial at this point, as parties’ regional strength/appeals could determine voters’ confidence in candidates’ capacity to channel resources back home.

A similar logic applies to the influence of religion on African politics and voters’ choices. In fact, in many African states including Nigeria, ethnicity and religion move in tandem. Zurlo et al. (Citation2020) speak of a shift in Christianity, and religion in general, to the global south, with Africa leading in the number of new believers which interestingly coincides with the return of democracy to the continent in the so-called ‘third wave’. This return could have paved the way for more civic freedoms and opened the civic space, leading to bolder religious expression both for pastors and their flock. An interesting set of literature on the relationship between religion and politics in Africa has shown intriguing interactions between church and state (Kendhammer, Citation2019; Obadare, Citation2018; Patterson, Citation2019).

While many African countries remain secular states constitutionally, religious expressions and symbolisms are in common usage among African voters and politicians. Obadare (Citation2018) describes how Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999 marked a rejuvenation of Pentecostal religious fervour, with the new Nigerian president converting to Christianity. In the flourishing of Pentecostalism in Africa with the third wave of democratisation, many Pentecostal churches have traced the origin of political power to occultic wealth, and tout themselves as having the authority to purify politics and politicians from the negative powers of darkness (Meyer, Citation1998). It is therefore not unusual for politicians to throw large thanksgiving services, and attribute their electoral victory to divine favours. While Patterson (Citation2019) discusses how this Pentecostal fervour infuses the ethics of self-improvement and serves as new modes of economic and political mobilisation, Obadare (Citation2018) cautions the excesses of prosperity preachers who might not be too different from wealth-seeking politicians. Islam has displayed similar interactions with African politics, with Obadare (Citation2018) illustrating how competition for political influence manifests between Christians and Muslims in Nigeria’s democratic third wave.

Kendhammer (Citation2019) observes that Muslims on the continent are generally in support of democracy, even with the rise of jihadism in certain parts of Africa, especially when their voices and religious practices are not discriminated against by the state. The adoption of Sharia Law by 12 Muslim majority states in Nigeria stands side by side with the gains made by Pentecostal Christians in the south. The rotation of power earlier discussed in Nigeria involves not only an ethnic basis but also a religious one. For instance, if the presidency is zoned to the north, the northern candidate who is often a Muslim is expected to choose a Christian running mate from the south for the sake of balance.

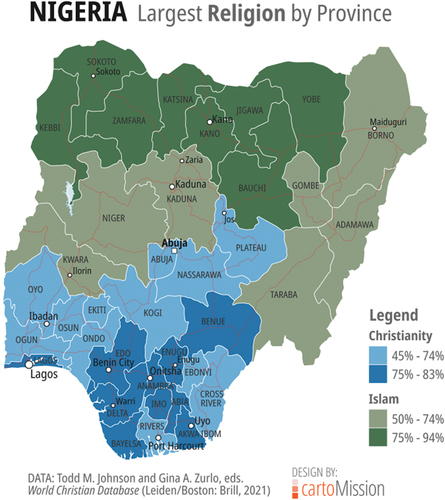

Nigeria’s religious geography adds a layer of complication in considering the influence of religion in politics – while voters in northern Nigeria are mostly Muslims, their countrymen in the south are mostly Christians as seen in , a path dependence from missionary activities in the colonial era, with western missionaries gaining more access to coastal settlements in the south, and less movement into the north where the jihad of Usman Dan Fodio had facilitated the spread of Islam (Martin, Citation2003), leading to a predominantly Muslim north, and predominantly Christian south.

Figure 1. Distribution of Christians and Muslims in Nigeria.

However, the Nigerian constitution prohibits the formation of parties on religious and ethnic bases, warning that parties must ‘not contain any ethnic or religious connotation or give the appearance that the activities of the association are confined to a part only of the geographical area of Nigeria’ (Nigerian Constitution, Citation1999, p.222e), thereby necessitating the existence of parties with broader appeals despite their ethno-religious strongholds. This ethno-religious consideration is more prominent at the national than constituency level, explaining why a Muslim-Christian or north-south ticket – in the form of power-sharing and rotation, is more of an informal arrangement within Nigerian parties in presidential elections (Agboga, Citation2021) than in constituency-based elections. In the latter, again, the ethno-religious appeals of candidates’ parties, rather than those of the candidates themselves because of their likely homogeneity, could influence voters’ choices.

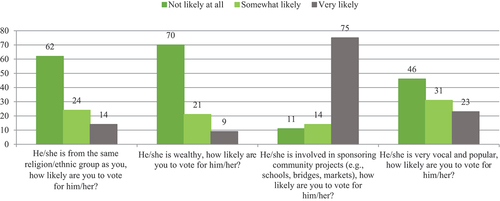

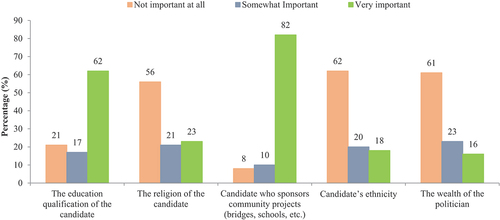

As for how this relates to support for party switching, the survey conducted for this research illustrates that a minority of about 40% responded that the ethnicity and religion of candidates are either important or somewhat important in their electoral choices as shown in .

Figure 2. In your opinion, how important are the following factors to you when considering who to vote for?.

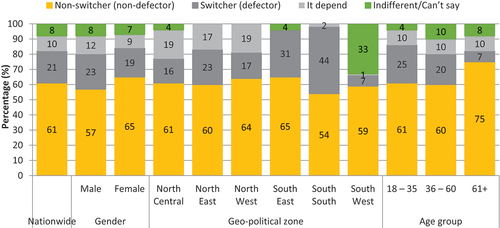

And in deciding between a switcher and a non-switcher, most participants (61%) responded that they would choose a non-switcher over a switcher – all things being equal – as shown in .

Figure 3. Suppose there are two politicians who are equal in every aspect except that one switched party, and the other one didn’t. Who would you likely vote for?.

When probed further, a similar percentage responded that they would not move with a switcher even if the latter is from their ethnic/religious group as illustrated in .

However, these can be construed as the socially acceptable responses, where participants might deny the salience of religion or ethnicity to avoid being profiled as bigots. I also found that while 57% of participants claimed that they participated in the last election (the socially acceptable answer), official government figures show that the turnout was just 34.75%. It should be noted that there could be some self-selection, as those who agreed to participate in the telephone survey could be those who are politically active. Bratton and Mwangi (Citation2008) found similar socially acceptable and politically correct responses when they conducted a survey on ethnicity in Kenya. While Kenyans denounced ethnic politics in the survey, their voting patterns and suspicion of outsiders revealed ‘defensive’ ethnic voting, like what I discussed earlier on perceived state bias and ethnic discrimination in the distribution of resources.

So, voting along religious or ethnic lines is not blind identity voting but rational in the context of intergroup competition for state resources, and history of state bias. Despite downplaying the importance of ethnicity in their choices, the electoral map of the 2019 election showed that the south predominantly voted PDP (which has produced two southern and Christian presidents), while APC won the north with the support of strong northern/Muslim elites as shown in . Juxtaposed with the religious map of Nigeria, it appears the predominantly Christian states voted PDP, while the Muslim states voted APC, but equally shows the presence of swing states/voters.

Figure 5. Voting patterns in the 2019 Nigerian general elections.

Succinctly, ethnicity and religion are key politically mobilising factors in Nigeria, with patterns of ethnic and religious voting as shown in the maps and figures above. But as earlier reiterated, these are not mere instances of people lining up behind politicians from their ethnic or religious group, but voting for the candidates or parties that they believe would best protect their interests amid suspicion of discrimination in the distribution of state resources. For party switching, those who defect to a party with a shaky ethno-religious reputation in their constituency are expected to have a difficult time winning elections. Agboga’s (Citation2023) study reveals a positive relationship between party strongholds and victory in elections. It demonstrated that candidates running in constituencies where their party is locally popular have a higher chance of winning. However, my analysis did not find a statistically significant result for individuals who switch to a popular party in their area. Thus, that research could not firmly conclude whether those who switch to a popular local party also secure re-election. I argue here that switching into a regionally popular party can improve one’s electoral prospect, given the party’s historical success in the region. The next section analyses the influence of wealth on support for party switchers, another important factor in (African) politics, and draws from the survey responses and existing literature on money politics on the continent.

Wealth and party switching

Politics is expensive in both developed and developing democracies alike, and to run a viable political campaign, politicians need to have strong financial backing. While donations could be sought from the private sector to support political campaigns, Arriola et al. (Citation2021) argue that African politicians seldom have this recourse to raise funds; rather, they are expected to expend their own money and other resources for political support. Nigerian politics is no exception to this, since both the public and party executives expect those vying for political offices to possess deep pockets for campaign expenses and handouts (Arriola et al., Citation2021; Lindberg, Citation2012). In Nigeria, it is obvious that politics is predominantly for the rich, given that the cost of party nomination forms is over a hundred times the country’s monthly minimum wage. The expression of interest and nomination forms alone (not adding other expenses) for the PDP for the 2023 election was about 3.5 million naira (Punch News, Citation2022), compared to the thirty thousand naira monthly minimum wage. As discussed by Agboga (Citation2023) on the ease of switching, wealth reduces the barriers to switching parties since party executives themselves actively encourage rich politicians to switch into their party to fund party expenses while advancing their own political ambitions. Koter (Citation2017, p. 576) argues that as campaign costs in Africa increase, including both traditional costs ‘such as printing posters and flyers and organizing meetings’, but also ‘transportation to rallies for their supporters, as well as food, drink, and entertainment’, less talented but wealthier politicians who can foot the bills crowd out talented but less wealthy candidates. With this, African democracies run the risk of replacing good leaders with simply wealthier ones with questionable character.

Nonetheless, many scholars of African politics have uncovered that wealth does not guarantee electoral success (Cheeseman et al., Citation2021; Lindberg, Citation2012). Cheeseman et al. (Citation2021) argued that while handouts from wealthy politicians could drive positives such as voter turnout and participation, wealthy candidates without credibility or a convincing story to tell behind the gifts they dole out often do not succeed at the polls. So, the moral justifications and promises made while giving out patronage and voters’ assessment of these is crucial. Relatedly, Lindberg (Citation2012) in his appropriately titled paper ‘Have the cake and eat it … ’ argued that, while African voters expect and collect gifts from politicians, the majority do not base their votes solely on the gifts received, but their general assessment of the candidates. Similarly, Gadjanova (Citation2020) argues that politicians give gifts to voters, voters expect gifts, but gifts do not guarantee victory. And since both incumbent and opposition compete in gift-giving, they adopt a second approach by constructing policy proposals for large group to outdo their opponents.

In Nigeria, when asked in the survey if they would choose a wealthy switcher over a non-switcher, a staggering 70% responded that they would choose a party loyalist, casting doubt on the power of wealth in shielding switchers from blowbacks of cross-carpeting. While they could be responding with the socially acceptable answer, Bratton (Citation2008) reveals that when voters were pressured by vote buying and electoral violence from both sides (incumbent and opposition) in Nigeria, they collected the money but stayed at home, or collected but secretly voted for their preferred candidates. So, there is corroborating evidence to suggest that money in and of itself has limited sway on Nigerian voters. However, it is important to admit the vital role of money in gaining political visibility, maintaining political networks, and even sponsoring community projects as Kramon (Citation2017) argues. So, while money could give politicians visibility, they need more than wealth to secure electoral victory as suggested in the survey response where only 30% responded that they were likely or somewhat likely to move camps with a wealthy party switcher.

Voters’ backpedalling? Community projects and switching

After most participants in the survey responded that they would choose non-switchers over switchers even if the latter are wealthy and come from their ethno-religious group, most participants actually backpedalled in the last question presented to them. When asked if they would support a switcher who is popular for community projects such as the building of schools, markets, and roads, 75% of respondents comprising of those who initially answered that they would not choose a switcher reversed their decision for this question. This implies that while switching is a negative heuristic for voters choices, switchers who distinguished themselves through providing community amenities could shield themselves from the repercussions of switching.

However, all Nigerian MPs (members of parliament, known in Nigeria as members of the House of Assembly, composed of senators and members of the House of Representatives), have a budget for constituency projects which could help to win the support of their constituents, and enjoy some independence from the executive branch of government (Demarest, Citation2021). Constituency projects have proven to be largely ineffective because of the lack of transparency and corruption in their administration. The Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC), an anti-graft agency in Nigeria, recovered ‘approximately N2.8 billion worth of assets diverted or embezzled through the constituency projects scheme from 2019 to 2021’ (Premium Times, Citation2022). So, with rampant corruption and the diversion of funds meant for constituency projects, many MPs are less likely to get the support of their constituency after they switch, while the few who administered tangible projects could shield themselves from reproach.

The same could apply to philanthropists who even before getting into politics used personal funds for community outreach, as such good works could raise organic support regardless of the party the philanthropist chooses to join. This implies that voters pay more attention to output and tangible results than party affiliation per se. While they might have party preferences and are generally suspicious of those who switch parties, their backpedalling shows that they are more interested in tangible results than mere party loyalty. Wealth is once again worth discussing here because it could facilitate the timely implementation of community projects, thereby winning the confidence of the people. As Cheeseman et al. (Citation2021) discover, wealth alone cannot guarantee electoral victory, but those who have a track record of using their wealth to help the community before the election period are seen as more credible candidates than those who only appear during election cycles.

In this context, when an MP with a track record of community projects switches party, it is not surprising that the constituency could switch with him (following results from the survey), since he has an antecedent of meeting the needs of the community. So, regardless of where he pitches his political tent, his strong developmental track record could shield him from blowbacks from party defection. This has broader implications for democracy in general, showing that people would shift camps or remain behind depending on their perception of which camp would best deliver tangible development. So, for democracy to endure in Africa, it needs to provide tangible benefits to the people, or they will look elsewhere (for example to military leaders). An Afrobarometer survey found that ‘a slim majority (53%) [of Africans] are willing to countenance this option [of supporting military rule] if elected leaders abuse power’ (Afrobarometer, 31 March Citation2023). Despite the ideological appeals of democracy, people may switch to supporting a military regime that they expect would deliver public goods, in the same way as they abandoned their dislike for party switching to follow a candidate who has a track record of delivering, despite switching parties.

Conclusion

This article sought to explain when and under what conditions Nigerian voters support politicians who switch political parties. Ethnicity, religion, wealth, and provision of community projects are factors that could sway voters according to previous research. However, survey results such as the one on which this article is based demonstrate that ethno-religious appeals alone do not guarantee voters’ support – in fact ethnicity is just one of several other factors, including the state of the economy and candidate trustworthiness. I have argued that while parties have regional strongholds which coincide with ethnic cleavages, ethnicity plays different roles at both national and constituency levels, since candidates in constituency elections are more likely to be from the same or neighbouring ethnic group(s). Nonetheless, the candidates’ party and its popularity in the region as opposed to their ethnicity become more important here.

Since most candidates contesting constituency seats are from similar ethno-religious backgrounds, the popularity of their party then comes into play. Nevertheless, the majority of participants in my survey (over 62%) responded that they would not support a switcher even if (s)he is from their ethnic group. While they likely responded with the socially acceptable answer, their response was triangulated with recent voting patterns in Nigeria which showed signs of ethno-religious voting. I nuanced the so-called ethnic voting hypothesis as people voting for those most likely to protect their interests, rather than merely lining up behind co-ethnics with no extrinsic value. On the implications for party switchers, those who switch to parties that are not popular among their co-ethnics would struggle to be re-elected.

Furthermore, while wealth plays a crucial role in politics to help fund campaign expenses and handouts to the public, wealth alone has proven to be a necessary but insufficient condition in guaranteeing electoral success. Most participants in the survey answered that they would not necessarily shift their vote to a wealthy MP who switched parties, and corroborating evidence from Nigeria shows that many voters still collect money from candidates but do not turn out to vote if they do not like the candidate(s), or secretly vote for their preferred candidate (Bratton, Citation2008). As many other scholars have found, short-term private goods inducements have a limited impact on voters’ choices.

Interestingly, most participants changed their minds when asked if they would support a switcher who is popular for funding community projects such as schools, markets, and bridges. A large majority (75%) responded that they would move parties with the switcher, signalling that voters are more interested in public goods provision than party loyalty. So, it can be deduced from this that if an MP switched parties but is known for delivering tangible public goods for his/her constituency, these community projects could shield him/her from public reproach for switching. With corruption scandals rocking the administration of constituency projects by MPs, and with anti-graft agencies uncovering the diversion of funds meant for these projects, most Nigerian MPs are expected to be found wanting in this regard, thereby having little shield against public reproach if they switched parties. This research complements earlier findings by Agboga (Citation2023) which uncovered that Nigerian voters punish their politicians for switching parties. It however examined the influences of different sets of sociological factors such as ethnicity, religion, and wealth, to arrive at a similar conclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afrobarometer. (2023, March 31). Young Africans show tolerance for military intervention – A wake-up call, afrobarometer CEO tells German leaders. https://www.afrobarometer.org/articles/young-africans-show-tolerance-for-military-intervention-a-wake-up-call-afrobarometer-ceo-tells-german-leaders/

- Agboga, V. (2021). In sickness and in health: Politics of presidential illness and intraparty factions in Africa. Colloquium Paper for African Politics Conference Group (APCG).

- Agboga, V. (2023). How do voters respond to party switching in Africa? Democratization, 30(7), 1335–1356. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13510347.2023.2232305

- Agboga, V. (2023). Nigerian electoral black market: Where do party switchers go and why does it matter?. Africa Spectrum. https://doi.org/10.1177/00020397231211930

- Angerbrandt, H. (2020). Party system institutionalization and the 2019 state elections in Nigeria. Regional & Federal Studies, 3(30), 415–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2020.1758073

- Arriola, L., Donghyun, C., Justine, D., Melanie, P., & Lise, R. (2021). Paying to party: Candidate resources and party switching in new democracies. Party Politics, 28(3), 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068821989563

- Boone, C. (2017). Sons of the soil conflict in Africa: Institutional determinants of ethnic conflict over land. World Development, 96, 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.012

- Bratton, M. (2008). Vote buying and violence in Nigerian election campaigns. Electoral Studies, 27(4), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2008.04.013

- Bratton, M., & Mwangi, K. (2008). Voting in Kenya: Putting ethnicity in perspective. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050802058401

- BusinessDay. (2017, November 1). Fact-check: 81 of Buhari’s 100 appointees are Northerners. https://businessday.ng/backpage/article/fact-check-81-buharis-100-appointees-northerners/

- Carey, S. (2002). Comparative analysis of political parties in Kenya, Zambia and the democratic Republic of Congo. Democratization, 9(3), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000259

- Carlson, E. (2015). Ethnic voting and accountability in Africa: A choice experiment in Uganda. World Politics, 67(2), 353–385. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887115000015

- Carto, Mission. (2021). Christianity and Islam in Nigeria. https://cartomission.com/2021/08/12/christianity-islam-nigeria/

- Cheeseman, N. (2010). African elections as vehicles for change. Journal of Democracy, 21(4), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2010.0019

- Cheeseman, N., & Ford, R. (2007). Ethnicity as a political cleavage. Working Paper, Afrobarometer. https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/wp83-ethnicity-political-cleavage/

- Cheeseman, N., Lynch, G., & Willis, J. (2021). The moral economy of elections in Africa: Democracy, voting and virtue. Cambridge University Press.

- Demarest, L. (2021). Men of the people? Democracy and prebendalism in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic National Assembly. Democratization, 4(28), 684–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1856085

- Desposato, S. W. (2006). Parties for rent? Ambition, ideology, and party switching in Brazil’s chamber of deputies. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 62–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00170.x

- Ekeh, P. (1975). Colonialism and the two publics in Africa: A theoretical statement. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 17(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500007659

- Elischer, S. (2013). Political parties in Africa: Ethnicity and party formation. Cambridge University Press.

- Ezeibe, C. C., & Ikeanyibe, O. M. (2017). Ethnic politics, hate speech, and access to political power in Nigeria. Africa Today, 63(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.63.4.04

- Gadjanova, E. (2020). Status-quo or grievance coalitions: The logic of cross-ethnic campaign appeals in Africa’s highly diverse states. Comparative Political Studies, 5(2), 652–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020957683

- Horowitz, D. (2000). Ethnic groups in conflict. University of California Press.

- International Centre for Investigative Reporting. (2021, May 29). Buhari’s lopsided appointments in six years continue to generate controversy. https://www.icirnigeria.org/buharis-lopsided-appointments-in-six-years-continue-to-generate-controversy/

- Kendhammer, B. (2019). Islam and democracy. In G. Lynch & V. Petter (Eds.), Routledge handbook of democratization in Africa (pp. 289–301). Routledge.

- Klein, E. (2019). Explaining legislative party switching in advanced and new democracies. Party Politics, 16(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819852262

- Koter, D. (2017). Costly electoral campaigns and the changing composition and quality of parliament: Evidence from Benin. African Affairs, 116(465), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adx022

- Kramon, E. (2017). Money for votes: The causes and consequences of electoral clientelism in Africa. Cambridge Press.

- Lindberg, S. (2012). Have the cake and eat it: The rational voter in Africa. Party Politics, 19(6), 945–961. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811436030

- Lindberg, S., & Morrison, M. (2005). Exploring voter alignments in Africa: Core and swing voters in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 43(4), 565–586. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X05001229

- Manning, C. (2005). Assessing African party systems after the third wave. Party Politics, 11(6), 707–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068805057606

- Martin, B. (2003). Muslim brotherhoods in nineteenth-century Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Mershon, C., & Shvetsova, O. (2013). The microfoundations of party system stability in legislatures. The Journal of Politics, 75(4), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000716

- Meyer, B. (1998). The power of money: Politics, occult forces, and pentecostalism in Ghana. African Studies Review, 41(3), 15. https://doi.org/10.2307/525352

- Nigerian Constitution. (1999). Federal Republic of Nigeria.

- Obadare, E. (2018). Pentecostal republic: Religion and the struggle for state power in Nigeria. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Patterson, A. (2019). Christianity and democracy. In G. Lynch & V. Petter (Eds.), Routledge handbook of democratization in Africa (pp. 275–288). Routledge.

- PM News. (2015, March 31). Igbo candidates win lagos reps seats. https://pmnewsnigeria.com/2015/03/31/igbo-candidates-win-lagos-reps-seats/

- Posner, D. (2005). Institutions and ethnic politics in Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Premium Times. (2022, September 15). Constituency projects fraud: ICPC recovers N2.8 billion in three years. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/554074-constituency-projects-fraud-icpc-recovers-n2-8-billion-in-three-years.html

- Punch News. (2022, March 30). Understanding new campaign finance law in Nigeria. https://punchng.com/understanding-new-campaign-finance-law-in-nigeria/

- Sahara Reporters. (2015, July 25). Buhari’s statement at the US Institute of peace that made everyone cringe. http://saharareporters.com/2015/07/25/buhari%E2%80%99s-statement-us-institute-peace-made-everyone-cringe-0

- Tavits, M. (2009). The making of mavericks: Local loyalties and party defection. Comparative Political Studies, 42(6), 793–815. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414008329900

- van de Walle, N. (2003). Presidentialism and clientelism in Africa’s emerging party systems. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 41(2), 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X03004269

- Wahman, M., & Boone, C. (2018). Captured countryside? Stability and change in sub-national support for African incumbent parties. Comparative Politics, 2(50), 189–216. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26532678

- Weghorst, K., & Lindberg, S. (2013). What drives the swing voter in Africa? American Journal of Political Science, 57(3), 717–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12022

- Zurlo, G. A., Johnson, T. M., & Crossing, P. F. (2020). World Christianity and mission 2020: Ongoing shift to the global south. International Bulletin of Mission Research, 44(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396939319880074