Abstract

The present paper explores how young children, depending on the provided input, acquire language-specific perspectives in the construal of goal-oriented locomotion events. We recorded parent–child interactions using drawings depicting such events. Czech monolingual pairs (n = 25), Russian monolingual pairs (n = 25), and Russian-German bilingual pairs (n = 22) were recruited for this study. Previous findings (Mertins 2018; Stutterheim et al. 2012) have demonstrated that Russian speakers conceptualize goal-oriented locomotion under the phasal perspective. Czech speakers, on the other hand, rely on the holistic perspective and are thus similar to German native speakers. In languages with a holistic perspective, speakers tend to focus on the endpoints of locomotion events. Therefore, we analyzed their prevalence in the parental language. The analyses revealed that Czech parents produced significantly more endpoints in the description of the critical stimuli than Russian and Russian-German parents. We argue that conceptual preferences and the verbalization of goal-oriented locomotion are input driven and acquired in early childhood.

1. Introduction

The acquisition of language involves more than just the learning of vocabulary, grammar, and communication strategies. It also encompasses language-specific patterns and rhetorical styles that are transmitted through parental input (Slobin Citation1996). Clark (Citation2009) highlights the importance of adult input in the acquisition of conventional language use, and emphasizes that children “learn what the conventions for that language are from the speakers who transmit the language to them” (Clark Citation2009, 234). In addition, when communicating with babies, adults use a specific type of speech known as child- or infant-directed speech (CDS or IDS).

This study explores language-specific perspectives in the construal of goal-oriented locomotion events in parental input. Goal-oriented locomotion events are defined by the continuous motion of animate or inanimate entities toward an endpoint (Schmiedtová, von Stutterheim, and Carroll 2011). Conceptual preferences of Czech, Russian, and Russian-German speakers are in focus. The term ‘conceptualization’ used in this paper is defined as the first phase in the process of language production, in which the preverbal message is prepared for expression and the communicative intention is formed (Levelt Citation1989). According to the thinking-for-speaking hypothesis, this component is language dependent and based on language-specific principles (Stutterheim and Nüse Citation2003). By ‘conceptual preferences,’ we mean such preferences, which are based on language-specific patterns and are retrieved during language production. According to a number of studies (cf. Mertins Citation2018; Schmiedtová, Stutterheim, and Carroll 2011), speakers of different languages select and verbalize information based on certain language-specific structures that influence event representation and conceptualization. In the area of locomotion events, studies have constantly been providing evidence that linguistic encoding of such events varies from language to language (Carroll, von Stutterheim, and Nüse Citation2004; Schmiedtová, Stutterheim, and Carroll 2011; Slobin Citation1996; Talmy Citation1985). These studies have demonstrated that speakers tend to prioritize either the process of motion events (phasal perspective) or the endpoint or outcome of the event (holistic perspective) based on the language they speak. These perspectives are referred to as “conceptual perspectives” in accordance with previous research (Schmiedtová Citation2013a; Mertins Citation2018). The variation in perspectives is associated with the grammaticalized aspect category, as detailed in Section 2. It has been shown that in verbalizations, these perspectives are reflected in the number of endpoints expressed by speakers. That is while talking about the same locomotion event, speakers of languages with holistic perspective (such as Czech and German) produce a higher number of endpoints than speakers of languages with phasal perspective (such as Russian) while talking about the same locomotion event (Schmiedtová Citation2008; Schmiedtová, von Stutterheim, and Carroll Citation2011; Schmiedtová Citation2013a; Schmiedtová and Sahonenko Citation2008; Stutterheim et al. Citation2012).

The research so far has only been concerned with adult speakers and has not investigated the emergence of language-specific perspectives in adult–child interaction. In our study, we focus on parental language input by looking at interactions of parent–child pairs in Russian, Czech, and Russian-German families over picture stimuli depicting goal-oriented locomotion events. We compare the expression of endpoints in parental input and hypothesize that their use will be language-specific. We formulated the following research questions: How do speakers of languages with different conceptual perspectives express endpoints in describing goal-oriented locomotion events while talking to children? Will there be cross-linguistic differences between Russian, Czech, and Russian-German speakers?

CDS is in our focus since it has, compared with speech directed to adults, some unique features: it is characterized by repetitions, a high number of questions, a large number of content words, and particular prosodic features such as slow pace, many pauses, clear language-specific rhythm, and pronounced speech melody (Snow Citation1977). Since CDS is a prevalent form of direct input, we were interested if language-specific preferences would be detectable in this kind of speech. ()

Table 1. Participants’ overview.

The current paper is organized as follows: Section 2 summarizes the theoretical framework, specifically focusing on research related to goal-oriented events and the acquisition of language-specific perspectives. Section 3 presents the research questions and the methodology employed in the experiment. Section 4 provides the study results, followed by a discussion of these findings in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 presents a summary and concluding remarks.

2. Previous studies

2.1. Investigation of locomotion events

There are two areas of investigation on language-specific patterns which characterize the field of motion events. One area of research has focused on Talmy’s lexicalization typology, i.e., the differences in the manner/path verb encoding (Talmy Citation1985). The studies show that the differences in the expression of path/manner verbs in satellite- and verb-framed languages have some impact on cognition (see Filipović and Ibarretxe-Antuñano Citation2015 for an overview). The second area explores holistic and phasal conceptual perspectives. We will describe the main findings of this research area in detail.

It has been demonstrated that there is a profound difference between languages with grammaticalized aspects, in which motion events are viewed as a process (phasal perspective), and non-aspectual languages, which emphasize the outcome/endpoint of the event (holistic perspective). The grammaticalized aspect is considered to be the primary influence on the perspectives taken when conceptualizing locomotion events. Speakers of aspectual languages are required to indicate whether an event is ongoing or completed directly in the verb. Stutterheim and Carroll (Citation2006) explain the significance of aspectual categories for the expression of endpoints; in languages where aspectual relations are grammaticalized and marked obligatorily, the time of utterance is linked to the topic time through aspectual markers, allowing ongoing events to be directly anchored. Therefore, “there is no need for one event to be represented as completed or bounded before another one is introduced” (Stutterheim and Carroll Citation2006, 43). On the other hand, speakers of languages without the grammaticalized aspect need to explicitly link the topic time to the preceding time of situation by expressing the points of completion (endpoints) or the results of the preceding events.

Our study compares speakers of three languages with different systems for expressing ongoingness and completion: Czech, German, and Russian. Firstly, we will describe the unique characteristics of the aspectual category in these languages, followed by a discussion of previous research on diverse languages.

As previously mentioned, the aspectual category expresses either ongoingness or completion of an event. Completion is expressed in perfective form, which is grammaticalized in Czech and Russian. Ongoingness can be expressed by progressive, simplex imperfective, or secondary imperfective aspects. Since the progressive aspect (e.g., the ing-form in English) is not available in Czech, German, or Russian, and the secondary imperfective is incompatible with verbs of motion, we will not discuss these forms further here (for more information, see Schmiedtová, von Stutterheim, and Carroll Citation2011). Thus, the attention will be focused on the simplex imperfective and perfective aspects, which are fundamental in Czech and Russian. German does not have a grammaticalized category of aspect (Schmiedtová Citation2013b), and it expresses ongoingness and completions by other means.

For a better understanding of the differences in the expression of ongoingness, consider the following examples from Czech (1a), Russian (1b), and German (1c). The event described in the examples is goal-oriented locomotion (horse runs), which includes three possible additional arguments: endpoint, path and manner:

Russian and Czech speakers use the simplex imperfective form of the verb, while Germans use a verb in the present tense. The example in Russian can be expressed without any additional arguments: Lošad´skačet (Rus) ‘a horse is running’. In Czech and German, by contrast, utterances of the type kůň běží (Czech) / ein Pferd reitet (Dt) ‘a horse is running’ are perceived as uncompleted or deviant by native speakers (Schmiedtová, von Stutterheim, and Carroll Citation2011). In all three languages, the encoding of manner, path, and endpoint presented in the examples as three alternatives can occur together in one utterance (Schmiedtová Citation2013b).

The perfective form in Czech and Russian is constructed by adding a prefix to the simple imperfective form, and it is utilized to denote the completion of an event.

Czech

Russian

A verb marked for perfectivity in goal-oriented locomotion requires an additional argument encoding the possible endpoint in both languages:

Czech

Russian

Czech

Russian

Although Czech and Russian can formally express identical aspectual forms (simplex imperfective, secondary imperfective, and perfective), they differ in how speakers use them. Simplex imperfective, which is the morphologically unmarked form and inherently imperfective, is accompanied in Czech by another argument, such as path, manner, or endpoint. This is not the case in Russian, where the imperfective form can be used in a bare phrase without additional grounding information. A further contrast lies in the usage of perfective verbs. In Russian, perfective verbs in the present tense always have a future tense reading (3b). In Czech, by contrast, the perfective aspect can also be used with the here-and-now reading (3a) (Schmiedtová Citation2008). The disparities mentioned above result in variations in how goal-oriented locomotion events are interpreted. Due to its specifics in the actual usage of the perfective and imperfective aspects, Czech can be grouped with German. Both languages prefer the holistic over the phasal perspective.

Czech, German, and Russian were examined in detail in Schmiedtová (Citation2013b). Language production data from adult speakers (N = 83) describing video clips depicting goal-oriented locomotion events were analyzed. While the number of endpoints expressed was significantly lower in Russian speakers (22 endpoints in total) compared with both Czech (52 in total) and German speakers (44 in total), there was no significant difference between Czech and German. Moreover, Russian speakers used bare verb phrases significantly more often than the other speakers (twenty times in total, compared with four times in Czech and five times in German).

Research on the conceptualization of locomotion events in other languages has revealed systematic language-specific differences. Stutterheim and Nüse (Citation2003) demonstrated cross-linguistic differences concerning encoding the endpoints of goal-oriented locomotion in native speakers of German, MS Arabic, and English. In this study, the subjects were presented with a silent film, the content of which they had to retell while watching the movie. The second task was to describe sixteen short computer animations depicting locomotion events unrelated to the silent movie. The results showed that the English-speaking subjects mentioned more events than the German-speaking subjects (21.5 events on average vs. 11.2), who concentrated on larger sequence units. In the descriptions, speakers of German preferred to verbalize events holistically and to focus more often on endpoints, even if they had to be inferred. They expressed 5.75 endpoints on average, compared with 1.8 expressed by English speakers, who preferred to divide the presented video clip into short sequences or phases and concentrated more on the process of the event. Endpoints were not in the foreground and were rarely mentioned (the phasal perspective). This means that German- and English-speaking participants encoded events differently, in a language-specific manner, despite being exposed to identical visual input. In several follow-up studies (Carroll, von Stutterheim, and Nüse Citation2004; Mertins Citation2018; Schmiedtová, von Stutterheim, and Carroll Citation2011), differences in the conceptualization and verbalization of motion events were identified for different languages (e.g., Dutch, Norwegian, Czech, Spanish, and Russian). Speakers of Dutch and Norwegian (both non-aspect languages) showed holistic conceptualization patterns when talking about goal-oriented locomotion. Native speakers of Spanish and Russian, similar to speakers of English, attended more to the phases of the locomotion event, with little or no attention to the endpoints. The same holds for other Slavic languages such as Polish and Slovak (Mertins Citation2018). Nonetheless, Czech stands out in this series. Although Czech, like other Slavic languages, encodes aspectual categories grammatically, Czech native speakers view goal-oriented locomotion events from a holistic perspective (Schmiedtová and Sahonenko Citation2008). These findings can be explained by the centuries-long, close language contact with German, which caused major changes in the usage of the Czech aspectual system (Mertins Citation2018).

2.2. Acquisition of language perspectives in the context of first language acquisition

The acquisition of conceptual perspectives takes place in the course of language acquisition. In our study, we follow a line of research on first language acquisition, emphasizing the importance of input as a basis for successful language acquisition. This line of research can be traced back to Vygotsky, who provided the basis for interactionist research, emphasizing interaction as a setting from which basic cognitive processes arise (Vygotsky Citation1962). Although the potential innate capacity for language acquisition has not yet been resolved (see Chomsky Citation1965 for the initial theory and Yang Citation2006 for an up-to-date overview), according to the interactionist approach to L1 acquisition, sufficient input and regular interaction between an adult and child are the most relevant preconditions for successful language acquisition (see, e.g., Arnon et al. Citation2014 for an overview). The role of input is crucial in the acquisition of language-specific patterns since it is the source of learning the conventional ways to use the preferred coding options.

Approximately between two and a half and three and half years of age, children comprehend (Wagner, Swensen, and Naigles Citation2009) and produce (Weist, Pawlak, and Carapella Citation2004; Gagarina Citation2009 for Russian) aspectual contrasts. In Slavic languages, expressing an aspect in the verb is obligatory, while verbal adjuncts may be left out. Since the canonical use of grammatical aspects is different in Czech compared with Russian (see chapter 2.1), it is highly probable that the particular way of using the aspectual forms is acquired, not inherently contained in the aspectual category itself. We expect the holistic and the phasal perspectives to be acquired during first language acquisition. Thus, we expect that the language input of speakers of languages with different perspectives will differ in a number of endpoints.

Several studies have investigated the acquisition of language-specific patterns for describing motion events during language acquisition. They followed Talmy’s research on lexicalization typology (see Harr Citation2012 for an overview). The ability to encode different elements of motion (i.e., manner, path) emerges in children younger than one year of age (Mandler Citation2004; Pulverman et al. Citation2008; Pulverman et al. Citation2003). Around three years of age, children follow the lexicalization patterns of their language when describing motion events (Choi and Bowerman Citation1991; Oh Citation2003; Ozc̣aliskan and Slobin Citation1999; Ozyürek et al. Citation2008; Papafragou, Massey, and Gleitman Citation2002). Hickmann and Hendriks (Citation2010) studied how speakers of French and English express motion events. It was analyzed which types of information components relevant to motion (cause, path, manner-of-cause, manner-of-motion) were expressed in children’s and adults’ utterances. Language-specific patterns were observable in spontaneous descriptions of motion events already in children of 2;6–3 years of age. While children learning English expressed more information about motion events by using both main verbs and elements of motion (i.e., cause, manner, and path), children learning French expressed all types of information relevant to motion using the main verb. A small number of studies investigating the encoding of motion events in bilingual children show an influence of L2 on L1 regarding the acquisition of lexicalization patterns. The cause of this influence is the increasing level of proficiency in L2, i.e., older children (Aveledo and Athanasopoulos Citation2016) or children who are more exposed to L2 (Aktan-Erciyes Citation2020) show more changes in lexicalization patterns towards L2 in their L1.

In the current study, we analyze parental input. Gopnik (Citation2001) underlines that “children do pay attention to the particularities of the adult language, and these particularities do affect the child’s conception of the world” (Gopnik Citation2001, 62). Parental input is also a major source of language-specific patterns. Bowerman and Choi (Citation2003) pointed out that “children’s utterances are more similar to those of adults speaking the same language than to children of the same age speaking another typologically different language” (Bowerman and Choi Citation2001, Citation2003). To our knowledge, no study to date has looked at the conceptual preferences of monolingual or bilingual children regarding the aspectual differences of languages and/or investigated the role of parental input in the acquisition of respective conceptual perspectives.

3. Experiment

3.1. Research question and hypotheses

In our experiment, we asked the following research question: Do parents speaking different languages differ regarding the number of endpoints they express in their child-directed speech?

Schmiedtová (Citation2013b) discovered differences in the number of endpoints in German, Russian, and Czech; Russian speakers expressed the endpoints significantly less than German and Czech speakers (see 2.1). We expect to find the same preferences in our speakers. Nonetheless, there is a number of dissimilarities between our sample and the groups of speakers examined in previous studies. To begin with, our emphasis is on parental input, specifically, child-directed Speech (CDS). As we know from the literature, this form of speech differs from adult-directed speech in several aspects (see 1; 2.1). While using CDS, adults pay more attention to their linguistic choices, giving children explicit directions on how to use the linguistic forms they are acquiring (Clark Citation2009). We are therefore interested if we find comparable results as in Schmiedtová (Citation2013b) in this particular way of speaking. Secondly, we included a group of bilingual speakers: Russian-German adults. We expected their way of expressing endpoints would be closer to the Russian perspective since Russian was their dominant language (more in 3.2). However, it was a variable not analyzed before in the CDS context.

We considered two main measurements to evaluate our data: the expression of endpoints in the conversation about picture stimuli and their expression in the first utterance relating to the locomotion event. The latter measurement was included due to the dialogic nature of our data. Previous studies have employed a monologue form consisting of brief scene descriptions. Although this form of measurement provides fairly comparable answers from participants regarding length, dialogues between parents and children differ significantly. Therefore, we required a measurement that would be the same in all conversations. As a result, we examined the first utterance in the description of the motion event. This allowed us to obtain additional information that the analysis of full dialogues could not provide. This approach is similar to the first passes in the area of an endpoint used in the analysis of eye movements in Stutterheim et al.’s (Citation2012) study. Stutterheim et al. (Citation2012) found that speakers of languages with a holistic perspective, such as German, Czech, and Dutch, focus more on the endpoint during the first period of fixation than during later periods, compared with speakers of languages with a phasal perspective, such as Spanish, Russian, Arabic, and English. This result is consistent with a similar finding reported by Stutterheim and Carroll’s (Citation2006).

To provide a better understanding of our coding system, we have included a full transcript of a conversation involving a stimulus that depicts a titmouse flying toward a bird feeder in winter (from the “clear endpoint” category).

The underlined utterance was coded as “first utterance relating to the motion event”:

Co je tady? Co je to za ptáčka?

‘What is it here? What kind of bird is it?’

Nevim

‘I don’t know’

Je zima co to tady padá? Sníh. Tadyten ptáček se jde napapat do budky. A já myslim že je to sýkorka

‘It is winter and what is it falling from the sky? Snow. This bird is going to eat into the bird-feeder. And I think it is a titmouse’

Sýkorka!

‘A titmouse!’

Je to sýkorka viď?

‘It is a titmouse, right?’

Jo

‘Yes’

Sýkorka letí na zrníčka. Má hlad protože je všechno zapadaný sněhem

‘The titmouse is going to eat the seeds. She is hungry because everything is under the snow’

H1: Czech parents express the highest number of endpoints in the conversation over the critical stimuli compared with Russian and Russian-German parents.

H2: Czech parents talk about endpoints earlier than Russian and Russian-German parents (i.e., they produce the highest number of endpoints in the first utterance).

3.2. Participants

We formed three groups of participants:

25 child–parent pairs participated in the study. All parents were Czech monolingual native speakers, and four of them have achieved high proficiency in L2 during their lives. All children were Czech native speakers. The discussion of the stimuli was held in Czech. The parents were recruited after participating in another experiment at the Institute of Psychology, Academy of Science in Prague. Their participation was voluntary and without financial reward.

25 child–parent pairs participated in the study. All parents came from families living in Moscow (Russia), and none were bilingual. The discussion of the stimuli was held in Russian. The parent–child pairs were recruited in kindergarten by the preschool teacher.

22 child–parent pairs participated in the study. All parents were native Russian speakers. Four participants indicated being Russian-Ukrainian bilingual from birth and learning German later in life. Since the aspect system of Ukrainian is very close to Russian, we decided to combine both language groups. All participants indicated that German is one of the active languages they use daily to communicate with their partners, friends, or for professional reasons. All of the subjects became bilingual later in life. The majority of parents (in 21 out of 22 cases) defined Russian as their dominant language, and only one participant characterized herself as a balanced German-Russian bilingual. All children were bilingual speakers and spoke Russian and German fluently. The stimuli were discussed mainly in Russian except for one mother–child pair, who spoke only German. The bilingual participants were contacted and recruited through Bochum’s intercultural language association “Lukomorje.”

3.3. Material

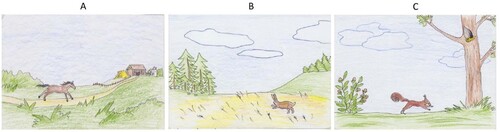

30 picture stimuli were used (see Appendix). They consisted of left and right variants of 15 original pictures on individual sheets of A5 paper. They all depicted an animal (or animals) performing a motion event. The control items depicted an animal heading toward an obvious endpoint. There were two kinds of critical stimuli: (1) The depiction of an animal heading toward an inferred endpoint; thus, it is up to the viewer to interpret the scene either in a holistic sense by expressing this endpoint, or to describe it as an ongoing event without expressing the endpoint. In line with Schmiedtová (Citation2013b) the endpoint was depicted in a way that was not obvious, but also never absent. We followed the same principle in constructing our stimuli. (2) The depiction of an animal heading from a starting point (source) towards an endpoint. These scenes provide the possibility to express another part of a locomotion event, the source, which serves as a distractor. We were aware of the phenomenon of goal-over-source asymmetry, which is an observed overall tendency of speakers of different languages to rather focus on a goal (semantically close to our endpoint) than on a source of an event (see e.g., Ungerer and Schmid Citation1996; Dirven and Verspoor Citation1998; Stefanowitsch Citation2018). However, since this asymmetry has so far been observed in languages independently of the aspectual systems, and since we are not interested in comparing the number of expressed “goals” compare to expressed “sources” in particular, we do not consider the asymmetry to interfere with the purpose of these stimuli. We chose these kinds of stimuli to assess if and how the level of complexity of the scene (source–goal stimuli) and ambiguity of an endpoint (inferred endpoint stimuli vs obvious endpoint stimuli) influences the prevalence of expressing the endpoint, and the differences between speakers of languages with different perspectives. The stimuli were piloted beforehand and changed accordingly. ()

Figure 1. Examples of stimuli: (A) control item: an animal heading towards an obvious endpoint (the barn); (B) critical item: an animal heading towards an inferred endpoint (the forest); (C) critical item: an animal heading from a starting point (source – the bush) towards an endpoint (the hole in the tree).

3.4. Procedure

Each parent received a set of 12 picture stimuli (4 from each group described above, six left-oriented and six right-oriented), a questionnaire about their demographic and linguistic background, and an audio recorder. They were instructed to view the pictures in random order with the child alone in a natural setting (i.e., without the experimenter’s presence), and speak with the child about the pictures. The interaction was recorded with an audio recorder, which was placed so that it could not be a distraction for the participating children. All participants gave their consent to participate in the experiment and for their data to be used in the context of further research projects at Dortmund University. In order to obtain relevant data, subjects were asked to concentrate on the events or actions depicted in the images while talking about the picture with the child (the instruction was “talk with your child about what is happening in the picture”). The participants were not told the true purpose of the study. In the last step, the recordings were transcribed, coded, and analyzed according to the rules explained in the next section. The average length of the audio recordings was around 15 min. All recordings were included in the analysis. The methodological approach is explained in more detail below.

3.5. Transcription, segmentation, and coding criteria

The audio data was transcribed at full length. The segmentation of the transcription followed. All utterances were coded based on coding criteria developed by Schmiedtová (Citation2013b). Two categories were defined for the analysis: the type of verbal adjuncts or complements and the type of utterance in which the coded adjuncts appear.

Verbal adjuncts and complements are defined as phrases that add additional information to the verb. Typical adjuncts are optional in the sentence, whereas complements are necessary to complete the sentence’s meaning. Adjuncts and complements provide a location, time, path, manner, or source information.

The following verbal adjuncts and complements were coded: endpoint (e.g., prepositional phrases, such as towards a stable, to the windowsill), location (e.g., in the meadow, in the forest), path (e.g., through the forest), source (e.g., from the house, from the stone), as well as any manner attribute (e.g., happy, high). The marking of purpose was also included in the analysis. Since an adjunct is never absolutely necessary in the sentence, the so-called bare verb phrases (BVP), i.e., verb phrases without any adjuncts (horse is running), were also considered in the coding. The examples below illustrate each of the different relevant coding categories. Russian examples are listed first, followed by Czech examples.

Endpoint is typically expressed using prepositional phrases (PPs), in Russian with the prepositions к ‘to’, в ‘in’, на ‘to/on’, по направлению к ‘towards’, in Czech with the prepositions do ‘into’, k ‘to’, na ‘to/on’:

Russian

Czech

In questions an endpoint is usually expressed by the interrogative pronoun куда ‘where to’ in Russian, and kam ‘where to’ in Czech:

Russian

Czech

Path is expressed by PPs with the Russian prepositions через ‘over’, по ‘on’, or вдоль ‘along’ and and the Czech preposition přes ‘across/along’ together with an accusative object:

Russian

Czech

Source is expressed by PPs with the prepositions из, с ‘from’ in Russian and with the prepositions od, z ‘from’ in Czech:

Russian

Czech

In questions, the source is expressed using the interrogative pronoun откуда ‘where from’ in Russian and odkud ‘where from’ in Czech:

Russian

Czech

Location is most often expressed using the prepositions в ‘in’, на ‘on’, or над/по ‘over’ in Russian and po ‘on’, nad ‘above/over’ in Czech:

Russian

Czech

In questions, location is expressed through the pronoun где ‘where’ in Russian, and kde ‘where’ in Czech:

Russian

Czech

Manner describes how an action is carried out. It can be expressed by

- an adverb:

Russian

Czech

- a comparison particle как ‘as/like’ in Russian and jako ‘as/like’ in Czech:

Russian

Czech

- an object in the oblique case in Russian:

Russian

- an interrogative pronoun как ‘how’ in Russian and jak ‘how’ in Czech in a question:

Russian

Czech

The Purpose of a motion event is expressed by the following lexical means:

- an infinitive

Russian

Czech

- a prepositional phrase

Russian

Czech

- a subordinate clause with additional words что бы ‘to’, потому что ‘because’

Russian

Bare verbal phrases (BVP) are utterances that contain only a predicate (verb) and a subject (noun, pronoun, etc.):

Russian

Czech

Validation: To validate the coding, sixteen transcripts (717 utterances) were coded independently of one another by two coders according to the rules listed above. Both coders had native proficiency in the analyzed languages. The intercoder reliability calculation was then carried out using Cohen’s kappa index. The number of actual matches was divided by the number of total utterances. The value of Cohen’s kappa index between the two coders was 0.97, which means that the average coders’ agreement was “almost perfect”, according to Landis and Koch’s (Citation1977) benchmarks for assessing the relative strength of agreement (Poor (< 0), Slight (.0–.20), Fair (.21–.40), Moderate (.41–.60), Substantial (.61–.80), and Almost Perfect (.81–1.0)). The percentage agreement for the eleven data sets in the critical group is 97% on average (the minimum agreement is 96% and the maximum agreement is 97%). The specified coding criteria were thus validated due to the very high degree of agreement. The other data sets were simply coded by the authors.

4. Results

4.1. Results of H1

To test this hypothesis, the statements of the parent and those of the child were included in the analysis and evaluation. It was assumed that a parent would not return to the actual components of the motion event (such as the endpoint) in the description if the child had already described the stimulus in detail and addressed the most important components.

The methodological procedure listed above (section 3.5) was used for the evaluation. The parents’ first utterance containing the endpoint was analyzed. If an endpoint was not realized in the language spoken by the adults, we included the child's utterances in the analysis. If the conversation did not contain an endpoint, we looked for information about the purpose of movement using the same procedure. For the reason of similarity, we considered both categories as containing an endpoint.

The other parts of the motion event (location, path, source, manner or BVP) and the static description of the scene were regarded as utterances without an endpoint. The Chi-square analysis was performed using R Statistical Software 4.1.3 (R Core Team Citation2022).

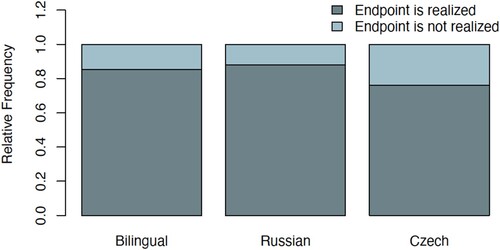

Control items. Clear endpoint (number of items: n = 10):

The difference between the three groups was statistically not significant (χ 2 = 2.2794, df = 2, p-value = 0.3199). This means that speakers of all groups produced a comparable number of endpoints in situations where the endpoint of locomotion was explicitly shown in the picture.

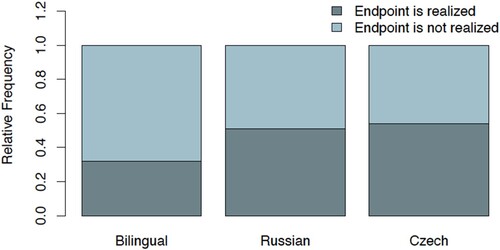

Critical items. Start-goal (number of items: n = 10): shows the comparison between bilingual, Russian and Czech speakers for critical items in the start-goal condition.

The difference between the three groups was similar to the control items with a “clear endpoint”, namely it was statistically not significant (χ 2 = 5.5503, df = 2, p-value = 0.06234).

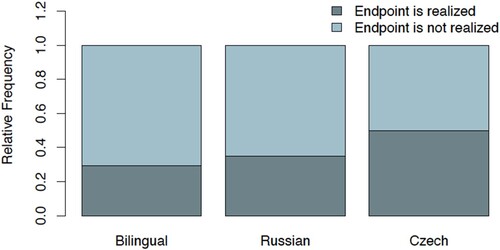

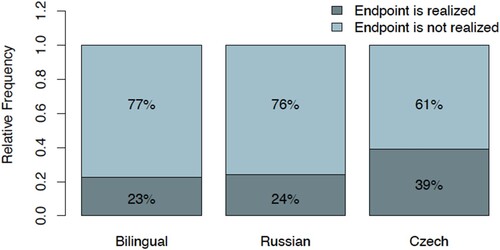

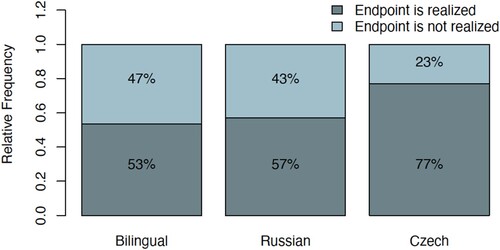

Critical items. Inferred endpoint (number of items: n = 10): shows the comparison between bilingual, Russian and Czech speakers for critical items with an inferred endpoint.

Figure 3. Percentages of the endpoint realized and not realized for the critical items “inferred endpoint”.

The data in shows that in the target language, Czech speakers encode almost twice the number of endpoints compared with Russian-German bilinguals and monolingual speakers of Russian. This difference was statistically significant (χ 2 = 13.4, df = 2 p-value = 0.001231). By contrast, no reliable difference was found between Russian monolingual and bilingual groups (χ 2 = 0.2442, df = 2, p-value = 0.621193).

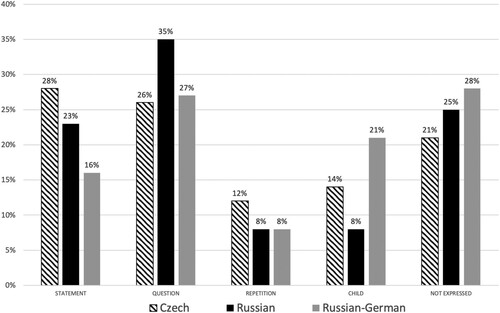

4.2. Results of H2

In the next step, the parents’ first utterance relating to the depicted locomotion was analyzed. This approach should show which component of the motion event is realized first in the conversation and therefore attracts greater attention. Since the focus of the present work is not the child’s response, only parental expressions were included in the analysis.

A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between language groups and the number of endpoints expressed in the first sentence. The relationship between these variables was significant for all three conditions: for the condition with a clear endpoint (χ 2 = 10.698, df = 2, p-value = 0.004752), start-goal items (χ 2 = 9.0791, df = 2, p-value = 0.01068) and inferred endpoint (χ 2 = 7.7768, df = 2, p-value = 0.02048). This means that Czech speakers were more likely to verbalize the endpoint in the first utterance in every condition compared with the bilinguals and speakers of Russian.

show the comparison between bilingual, Russian, and Czech speakers for the control items, start-goal condition, and critical items with an inferred endpoint.

5. Discussion

This study explored parental input’s role in acquiring language-specific conceptual perspectives. Child-directed speech (CDS) is a specific form of speech primarily found in Western cultures and has many specific features. Our aim was to investigate whether language-specific perspectives are part of this specific kind of speech, with a focus on the expression of endpoints since endpoint encoding is the main trigger for the emergence of the phasal and holistic perspectives. We hypothesized that the number of endpoints expressed in CDS by Czech-speaking parents would be higher than by parents speaking Russian and Russian-German. Furthermore, we predicted that Czech parents would introduce endpoints right at the outset of the conversation, specifically in the first utterance regarding the motion event. The results confirmed both our hypotheses.

There are several implications we can draw from the findings. When we consider the entire course of the conversation, the endpoint was expressed at some point, independent of language and condition. It was not unanticipated since the stimuli were simple scenes, and the endpoints were still a prominent part of the picture. However, the analyses showed that when the endpoint is unclear (stimulus type “inferred endpoint”), the language-specific perspectives influence how it is interpreted and conceptualized: Czech parents included the endpoint in the description of this stimulus type more often than the other two groups. This aligns with the previous findings: Czech speakers preferred expressing endpoints more than Russian speakers (e.g., Schmiedtová Citation2013b; Stutterheim and Carroll Citation2006). A new finding showed this still holds when comparing Czech speakers with Russian-German bilingual speakers. We assume that the choice of phasal perspective was driven by the dominance of the Russian language in the majority of bilingual speakers. This finding should be explored further, and bilingual speakers of languages with different conceptual perspectives should be employed more systematically in research.

Moreover, we have now analyzed a form of speech that has not been the primary focus of previous research: child-directed speech. We discovered that even in the CDS, participants adhere to the conceptual perspective of their language. Therefore, we consider it is crucial to shift the research attention towards language-specific patterns in input, rather than solely examining children’s language skills. Additionally, it is essential to analyze data from spontaneous conversations. Previous studies on holistic and phasal perspectives employed elicitation tasks where adult participants described scenes in simple sentences. Our experiment focused on the complex dialogue form and how the expression of endpoints emerges in the turn-taking procedure.

Another question investigated in this study relates to the time in the conversation when the parents verbalized the endpoint. The early attention to some remarkable components of a locomotion event can be connected to the prominence speakers attribute to these parts. As expected, the animal as a protagonist is spotted and commented on first, followed by a description of other parts of the scene. We analyzed the first utterances the parents produced containing the locomotion event. The analysis revealed that the prominence of endpoints is consistently the highest among Czech participants compared with the other two groups (see ). These findings are consistent with previous studies employing eye-tracking (Mertins Citation2018; Stutterheim et al. Citation2012). According to these studies, speakers of holistic languages showed a faster entry time into the endpoint area than speakers of phasal languages while observing a goal-oriented motion event. The distribution of attention in our dataset is comparable: the prominence of endpoints is high for Czech speakers. Moreover, they mention them very early in the conversation. We found many instances of sequences in Czech parent–child pairs, such as the following:

Example 12 is a segment from the start of the conversation, where a picture of a swallow flying to its nest was being discussed. Initially, the parent posed a general question about the swallow’s action. When the child responded with a bare verb phrase (i.e., she is flying), the parent immediately followed up with a question directly focused on the endpoint (i.e., where is she flying to?). This early exchange in the conversation demonstrates the parent’s intentional effort to direct the child’s attention to the endpoint.

Our study provides valuable information regarding input’s role in acquiring language-specific preferences. The expression of endpoints in CDS during an active parent–child interaction follows the same patterns as in single utterances of adult speakers (Schmiedtová Citation2013b; Stutterheim and Carroll Citation2006; Stutterheim and Nüse Citation2003). In our forthcoming studies, we seek to examine when the expression of endpoints begins to conform to language-specific patterns, as the onset of this process varies across different areas of language-specific conceptualization (see section 2.2). We hypothesize that language-specific preferences for endpoint expression may emerge around three years of age, as children of this age already follow lexicalization patterns of their language while describing locomotion (Hickmann and Hendriks Citation2010; Choi and Bowerman Citation1991; Oh Citation2003; Ozc̣aliskan and Slobin Citation1999; Ozyürek et al. Citation2008; Papafragou, Massey, and Gleitman Citation2002). However, as Lucy (Citation2004) pointed out, some more complex preferences are gradually acquired until approximately nine years of age. Therefore, a further investigation of children’s expression of endpoints is needed.

Including a group of bilingual children and their parents whose dominant language was mainly Russian made it possible to examine if the bilingual setting influences the expression of endpoints. The results revealed that bilingual Russian-German parents did not differ significantly from Russian parents in the number of endpoints expressed in Russian. However, several intriguing patterns were identified when we examined the whole conversation and considered the child’s speech. We counted the situations where the parent did not express the endpoint during the whole conversation and then looked at whether the child expressed the missing endpoint in such situations. The data showed a tendency for bilingual children to express the endpoint in such cases – they did it 21% of the time. In comparison, Czech children did this less often (14%), and Russian children did it in the least number of cases (8%). We interpreted these results as a compensation strategy employed by bilingual children for the absence of endpoints in the parent’s description. To put it differently, for bilingual children whose exposure to German was comparable to or greater than their exposure to Russian (with German being the dominant language for seven of them), the holistic perspective played an important role in their interpretation of the pictures. At the same time, it did not hold true for their parents, who considered Russian as their dominant language. Additionally, the recordings of bilingual speakers were carried out in Russian. We assume that the language context influences the activation of a particular perspective. That would explain why Russian-German and Russian parents behave similarly while speaking Russian. However, the children’s data suggests that activation of a particular conceptual perspective could occur regardless of the local language context. Further studies aimed at this question are necessary to evaluate the plausibility of this presumption.

6. Conclusion

The current study sheds new light on the role of input in the acquisition of conceptual preferences. Although the qualitative and quantitative analysis of our data shows that caregivers follow the conceptual perspectives of their native (or dominant) language while talking about goal-oriented locomotion events to their child, we should be careful when interpreting these results. Our experiment carries the same limitations as essentially all behavioral studies: the recording conditions and language-independent factors cause an inevitable noise. For example, we observed that Russian parents expressed endpoints in “clear-endpoint” stimuli types earlier than Czech and bilingual speakers. This phenomenon could be attributed to the fact that the Russian parents were asked to record their verbalizations by their child’s preschool teacher, which motivated them to perform the task with greater precision, potentially adopting a more interrogative style than they would in an unrecorded conversation. Further studies investigating language-specific conceptual perspectives in parental input are thus necessary to study the influence of the recording environment.

Moreover, we need more studies aimed at bilingual speakers. We observed that Czech and Russian monolingual parents followed the perspectives of their language, and the parents in the bilingual group with Russian as their dominant language followed the perspective of the Russian language when speaking Russian. However, their children, under the influence of the German language, provided a holistic interpretation of the scene in situations where their parents did not. We did not observe this pattern in the verbalizations by monolingual Russian children. We interpret this observation as a sign of the impact of language input on the acquisition of conceptual preferences. Further research should focus on the bilingual context, with data collected from Russian-German bilingual households in German to provide further evidence of the impact of language context and dominance.

Supplemental Material

Download (111.3 MB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aktan-Erciyes, Asli. 2020. “Effects of Second Language on Motion Event Lexicalization: Comparison of Bilingual and Monolingual Children’s Frog Story Narratives.” Dil Ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi 16 (3): 1127–1145. https://doi.org/10.17263/jlls.803576.

- Arnon, Inbal, Marisa Casillas, Chikusa Kurumada, and Bruno Estigarribia. 2014. Language in Interaction: Studies in Honor of Eve V. Clark (Trends in Language Acquisition Research). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Aveledo, Fraibet and Panos Athanasopoulos. 2016. “Second Language Influence on First Language Motion Event Encoding and Categorization in Spanish-Speaking Children Learning L2 English.” International Journal of Bilingualism 20 (4): 403–420.

- Bowerman, Melissa and Soonja Choi. 2001. “Shaping Meanings for Language: Universal and Language-Specific in the Acquisition of Semantic Categories.” In Language, Culture and Cognition: Vol. 3 Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development, edited by Melissa Bowerman and Stephen C. Levinson, 475–511. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bowerman, Melissa and Soonja Choi. 2003. “Space Under Construction: Language-Specific Spatial Categorization in First Language Acquisition.” In Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Thought, edited by Dedre Gentner and Susan Goldin, 387–428. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Carroll, Mary, Christiane von Stutterheim, and Ralf Nüse. 2004. “The Language and Thought Debate: A Psycholinguistic Approach.” In Multidisciplinary Approaches to Language Production, edited by Thomas Pechmann and Christopher Habel, 183–218. New York: Mouton De Gruyter.

- Choi, Soonja and Melissa Bowerman. 1991. “Learning to Express Motion Events in English and Korean: The Influence of Language-Specific Lexicalization Patterns.” Cognition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(91)90033-Z

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Clark, Eve V. 2009. First Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dirven, René and Marjolijn Verspoor. 1998. Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Filipović, Luna and Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano. 2015. “Motion.” In Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics (Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science 39), edited by Ewa Dąbrowska and Dagmar Divjak, 527–545. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Gagarina, Natalia V. 2009. “Formirovanije grammaticheskih kategorij vida i vremeni, lica I chisla na rannih etapah rechevogo ontogeneza.” Trudy inatituta linguisticheskih issledovanij, Sankt-Petersburg: Nestor-Istorija 7–64.

- Gopnik, Alison. 2001. “Theories, Language, and Culture: Whorf Without Wincing.” In Language, Culture, and Cognition (vol. 3): Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development, edited by Melissa Bowerman and Stephen C. Levinson, 45–69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harr, Anne-Katharina. 2012. Language-specific Factors in First Language Acquisition. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Hickmann, Maya and Henriette Hendriks. 2010. “Typological Constraints on the Acquisition of Spatial Language in French and English.” Cognitive Linguistics 21 (2): 189–215.

- Landis, James and Gert Koch. 1977. “The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data.” Biometrics 33: 159–174.

- Levelt, Willem J. M. 1989. Speaking: From Intention to Articulation. Cambridge/Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Lucy, John A. 2004. “Language, Culture, and Mind in Comparative Perspective.” In Language, Culture and Mind, edited by Michel Achard and Suzanne Kemmer, 1–22. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

- Mandler, Jean M. 2004. The Foundations of Mind: Origins of Conceptual Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mertins, Barbara. 2018. Sprache und Kognition. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Oh, K. J. 2003. “Manner and Path in Motion Event Descriptions in English and Korean.” In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development I-II, edited by Barbara Beachley, Amanda Brown, and Frances Conlin, 580–590. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

- Ozc̣aliskan, Şeyda and Dan I. Slobin. 1999. “Learning How to Search for the Frog: Expression of Manner of Motion in English, Spanish, and Turkish.” In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development I-II, edited by Annabel Greenhill, Heather Littlefield, and Cheryl Tano, 541–552. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

- Ozyürek, Asli, Sotaro Kita, Shanley Allen, Amanda Brown, Reyhan Furman, and Tomoko Ishizuka. 2008. “Development of Cross-Linguistic Variation in Speech and Gesture: Motion Events in English and Turkish.” Developmental Psychology 44 (4): 1040–1054.

- Papafragou, Anna, Christine Massey, and Lila Gleitman. 2002. “Shake, Rattle, ‘n’ Roll: The Representation of Motion in Language and Cognition.” Cognition 84 (2): 189–219.

- Pulverman, Rachel, Roberto M. Golinkoff, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Jennifer S. Buresh. 2008. “Infants Discriminate Manners and Paths in Non-Linguistic Dynamic Events.” Cognition 108 (3): 825–830.

- Pulverman, Rachel, Jennifer L. Sootsman, Roberto M. Golinkoff, and Kathy Hirsh Pasek. 2003. “The Role of Lexical Knowledge in Nonlinguistic Event Processing: English-Speaking Infants’ Attention to Manner and Path.” In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development I-II, edited by Barbara Beachley, Amanda Brown, and Frances Conlin, 662–673. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Schmiedtová, Barbara. 2008. At the Same Time: The Expression of Simultaneity in Learner Varieties. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Schmiedtová, Barbara. 2013a. “Traces of L1 Patterns in the Event Construal of Czech Advanced Speakers of L2 English and L2 German.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 51 (2): 87–116.

- Schmiedtová, Barbara. 2013b. “Zum Einfluss des Deutschen auf das Tschechische: Die Effekte des Zeitdrucks auf die Sprachproduktion.” In Bilingualer Sprachvergleich und Typologie: Deutsch - Tschechisch, edited by Marek Nekula, Kateřina Šichová, and Jana Valdrová, 177–206. Tübingen: Julius Groos.

- Schmiedtová, Barbara and Natalya Sahonenko. 2008. “Die Rolle des Grammatischen Aspekts in Ereignis-Enkodierung: Ein Vergleich Zwischen Tschechischen und Russischen Lernern des Deutschen.” In Fortgeschrittene Lernervarietäten: Korpuslinguistik und Zweitspracherwerbsforschung, edited by Maik Walter and Patrick Grommes, 45–71. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer.

- Schmiedtová, Barbara, Christiane von Stutterheim, and Mary Carroll. 2011. “Language-specific Patterns in Event Construal of Advanced Second Language Speakers.” In Thinking and Speaking in Two Languages, edited by Aneta Pavlnko, 66–107. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Slobin, Dan I. 1996. “From ‘Thought and Language’ to ‘Thinking for Speaking’.” In Rethinking Linguistic Relativity, edited by John J. Gumperz and Stephen C. Levinson, 70–96. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Snow, Catherine E., ed. 1977. Talking to Children: Language Input and Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stefanowitsch, Anatol. 2018. “The Goal Bias Revised: A Collostructional Approach.” Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association 6 (1): 143–166.

- Stutterheim, Christiane von, Martin Andermann, Mary Carroll, Monique Flecken, and Barbara Schmiedtová. 2012. “How Grammaticized Concepts Shape Event Conceptualization in Language Production: Insights from Linguistic Analysis, Eye Tracking Data, and Memory Performance.” Linguistics 50 (4): 833–867.

- Stutterheim, Christiane von and Mary Carroll. 2006. “The Impact of Grammatical Temporal Categories on Ultimate Attainment in L2 Learning.” In Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics Series. Educating for Advanced Foreign Language Capacities: Constructs, Curriculum, Instruction, Aassessment, edited by Heidi Byrnes, Heather Weger-Guntharp, and Katherine A. Sprang, 40–53. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Stutterheim, Christiane von and Ralf Nüse. 2003. “Processes of Conceptualization in Language Production: Language-Specific Perspectives and Event Construal.” Linguistics 41 (5): 851–881.

- Talmy, Leonard. 1985. “Lexicalization Patterns: Semantic Structure in Lexical Forms.” In LanguageTypology and Syntactic Description (vol 3): Grammatical Categories and the Lexicon, edited by Timothy Shopen, 57–149. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ungerer, Friedrich and Hans-Jörg Schmid. 1996. An Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics. London/New York: Longman.

- Vygotsky, Lev. 1962. Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Wagner, Laura, Lauren D. Swensen, and Letitia R. Naigles. 2009. “Children's Early Productivity with Verbal Morphology.” Cognitive Development 24 (3): 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2009.05.001.

- Weist, Richard M., Aleksandra Pawlak, and Jenell Carapella. 2004. “Syntactic-semantic Interface in the Acquisition of Verb Morphology.” Journal of Child Language 31 (1): 31–60.

- Yang, Charles. 2006. The Infinite Gift: How Children Can Learn and Unlearn all the Languages of the World. New York: Scribner.