Abstract

Regulatory focus theory has been used as a framework to elucidate the effects of advertising messages as well as those of some non-verbal advertising elements including endorsers’ gestures. However, previous advertising research has not discussed the role of celebrity endorsement based on this theory. In this research, we conducted three experiments to examine the moderating effect of the endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) on the causal relationships of the gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) and the message framing (promotional vs. preventive) via consumer motivational mindset changes. We found that, compared to unknown, noncelebrity endorsers, familiar celebrity endorsers are more likely to promote eager (vigilant) gestures to generate consumers’ promotion (prevention) focus orientation, leading to a favorable evaluation of the product of which advertising message is framed in a promotional (preventive) way. This research contributes to research on both regulatory focus and celebrity endorsement.

Introduction

With the advance of information and communication technologies, electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) communication that is shared and exchanged by consumers has become increasingly important. Recently, YouTube and TikTok amateur videos have jeopardized not only the popularity of TV programs but also the effectiveness of TV advertising. Certainly, some YouTubers and TikTokers have become very famous as social media influencers and, thus, can be regarded as ‘(internet) celebrities’ though they are not given attention through the mass media. However, an overwhelming majority of information senders via social media networks are amateurs rather than celebrities because they achieve neither broad recognition nor good fame. Nevertheless, they eagerly produce social media content regarding product information and deliver them as forms of impressive, professional-looking videos. As a result, it can be said that the effects of such eWOM advertisements produced and endorsed by noncelebrity amateurs have become comparable to those produced by professionals and endorsed by celebrities. Note that there is a single crucial difference between them—The latter advertisements can employ well-known celebrity endorsers, while the former can feature only vloggers themselves, who are noncelebrities rather than celebrities unless they are famous influencers.

A celebrity can be defined as a famous person with a favorable public image, whereas noncelebrity, amateur endorsers are unfamiliar persons to consumers. This concept has been mentioned in the earliest studies of advertising endorsement and has always been mentioned in subsequent endorser studies. For example, Friedman and Friedman (Citation1979) argued that celebrities are more credible and attractive as persuaders and thus are more likely than noncelebrity endorsers to convey persuasive messages. McCracken (Citation1989) argued that consumers attach favorable meanings to celebrities, which can be transferred to advertised products via endorsement. However, Tripp, Jensen, and Carlson (Citation1994) claimed that such an effect is hindered when celebrities endorse too many products and their favorable meanings are difficult to be transferred. More recently, Carrillat and Ilicic (Citation2019) proposed a conceptual framework regarding celebrity capital based on the classical life cycle theory.

As examined by the most recent review article on celebrity endorsement (Schimmelpfennig and Hunt Citation2019), the role of celebrity endorsers has long been discussed based on classical models developed decades ago, such as the source credibility model, the source attractiveness model, or the meaning transfer model (Hovland, Janis, and Kelley Citation1953; Hovland and Weiss Citation1951; McCracken Citation1989; McGuire Citation1985) and significant progress in this field has not been made for many years. Rossiter and Percy (Citation1997), Rossiter and Bellman (Citation2005), and Schimmelpfennig and Hunt (Citation2019) proposed conceptual frameworks that consider all existing theoretical models mentioned above simultaneously. However, new proportions have not yet been induced from their comprehensive frameworks.

It should be noted that all these existing models have lacked the notion that as information recipients, consumers perceive advertising endorsers as information sources of verbal cues, i.e. the endorsers’ utterances and, at the same time, they perceive them as sources of non-verbal cues, i.e. gestures and other facial and body expressions. In general, consumer information processing to achieve their choice task has been explained based on any goal achievement theories. One of the most cited theories in recent years is Regulatory focus theory, which describes that individuals have different two regulatory focuses, i.e. promotion and prevention focuses. This theory has been formulated in the field of social psychology, and attention has also been paid to the theory in the field of marketing and consumer studies including advertising (cf. Kim et al. Citation2023; Yoon, Sarial-Abi, and Gürhan-Canli Citation2011) though it has not yet been applied to research on advertising endorsers. More and more researchers have employed the theory to investigate the effect of regulatory focus on attitude (e.g. Aaker and Lee Citation2001), judgment and decision-making (e.g. Higgins and Molden Citation2003), consumer payoff structure, sensitivity to gains and losses (e.g. Markman, Baldwin, and Maddox Citation2005), or consumer decision-making process (e.g. Kirmani and Zhu Citation2007; Monga and Zhu Citation2005; Pham and Avnet Citation2004; Pham and Chang Citation2010).

According to the findings of research based on Regulatory focus theory, promotion-focused consumers are likely to highly evaluate advertisements when the message emphasizes that the advertised products increase the consumers’ benefits. Contrarily, prevention-focused consumers highly evaluate the advertisements when the messages emphasize that the advertised products decrease the consumers’ costs (Aaker and Lee Citation2001; Avnet and Higgins Citation2006; Cesario, Grant, and Higgins Citation2004; Higgins, Idson, Freitas, Spiegel, and Molden Citation2003; Lee and Aaker Citation2004; Pham and Avnet Citation2004).

While most studies employing the theory have focused only on verbal cues in persuasion, a few studies have treated non-verbal cues. For example, as a pioneering study on the impacts of non-verbal cues employing Regulatory focus theory, Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008) pointed out that a fast speech rate, animated, broad opening movements, hand movements openly projecting outward, forward-learning body positions, and fast body movement may convey confidence and, in some cases, recklessness, and therefore, make promotion-focused recipients feel right and result in greater message effectiveness for individuals with a promotion focus. However, no research on non-verbal cues based on Regulatory focus theory has been conducted in the context of advertising and, thus, there is room for advertising research that takes into consideration whether the endorser is a celebrity or noncelebrity in addition to considering the endorser as a verbal cue as well as a non-verbal cue.

Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, all prior studies regarding endorsement in advertising have focused only on the effects of informative cues on product evaluations given that each consumer has an inherent motivational mindset (e.g. Aaker and Lee Citation2001; Lee and Aaker Citation2004). However, some related studies have reported that persuasive cues can change consumers’ motivational mindset (e.g. Fei, You, and Yang Citation2020; Jia, Yang, and Jiang Citation2022). Consumers exposed to eager style endorsement may become promotion-focus-oriented, whereas those exposed to vigilant style endorsement may become prevention-focus-oriented.

Thus, in this research, applying Regulatory focus theory to advertising endorsement research, we newly consider the effects of a celebrity/noncelebrity endorsement on consumer evaluations, in addition to the effects of the eager/vigilant gesture style (a non-verbal cue) and regulatory focus message frames (a verbal cue). Also, when constructing a model regarding the moderating effect of the endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) on the causal relationship between the gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) and the message focus frame (promotional vs. preventive ways), we consider the effect of endorsement on regulatory focus orientation. By doing so, this research contributes to research on both regulatory focus and celebrity endorsement. Also, advertisers are provided with deep insights into practical issues regarding the choice between celebrity and noncelebrity advertising endorsers, or the choice between famous influencers (e.g. celebrity influencers and mega influencers) and unknown amateur vloggers.

Theoretical background

Classification of endorser types

Some studies, especially pioneering studies, of advertising endorsement have compared the effects of different types of endorsers including celebrity endorsers and have accumulated a lot of empirical findings. For example, Friedman and Friedman (Citation1979) investigated celebrity endorsers and two types of noncelebrities (experts and typical consumers) and reported that celebrity endorsement helps consumers recall brands and leads to higher evaluations of products in some categories. Atkin and Block (Citation1983) divided endorsers into celebrities and noncelebrities and found that the former led to higher ad evaluations. More recently, Tom et al. (Citation1992) found that celebrities are superior to created spokespersons in terms of customer recall.

Contrary to these studies, Freiden (Citation1984) compared four types of endorsers (celebrities, CEOs, consumers, and technicians) and found no differences in consumer attitudes toward the ads. Moreover, Stafford, Stafford, and Day (Citation2002) examined the differences among four types of endorsers (celebrities, animated-spokes-characters, employees, and customers), and found that animated characters are superior to the other types. Pashupati (Citation2009) also provided evidence that animated characters best resulted in consumers’ positive emotions.

Source credibility model

Some researchers have explicitly employed theoretical models that describe why some endorsers are superior to others. The source credibility model suggests that endorsers with high technical expertise and/or trustworthiness are perceived as credible, thus leading to effective endorsements. In this sense, technician endorsers would be superior to celebrities because they are high in expertise perceived by message recipients (cf.Hovland, Janis, and Kelley Citation1953; Hovland and Weiss Citation1951).

However, unlike expertise, the trustworthiness of technicians as information sources may not be higher because consumers are less likely to attach a high level of trust to advertising endorsers who were paid by advertisers. Ohanian (Citation1990) discussed that celebrities are not high in trustworthiness due to the same reason and concluded that trustworthiness does not have a significant impact on advertising effectiveness. Rossiter and Percy (Citation1997) proposed, therefore, that objectivity was an important factor rather than trustworthiness. However, more recently, Priester and Petty (Citation2003) reported that trustworthiness was significant. Biswas, Biswas, and Das (Citation2006) discussed that for technology-based products, expertise is more likely to be significant than trustworthiness and therefore, technician endorsers are more effective than celebrity endorsers.

Source attractiveness model

Based on the source attractiveness model, endorsers who are highly familiar and/or likable are perceived as attractive and thus effective endorsers; in this regard, both celebrities and typical consumers would be the best options (McGuire Citation1985). Raven et al. (Citation1998) suggested that celebrities are the best endorser type in attractiveness because they hold a high social status and are admired by consumers.

In related research, Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann (Citation1983) implied in their elaborated likelihood model, that low-involved consumers are likely to form favorable attitudes toward the advertised brand when the advertising endorser is attractive. Recently, it has been found that attractive endorsers are more effective than well-matched endorsers in certain cultures (Liu, Huang, and Minghua Citation2007).

Meaning transfer model

McCracken (Citation1989) proposed the meaning transfer model, suggesting that celebrities have their own favorable or unfavorable associations through their movie or musical performances or athletic achievements, which can be transferred to the advertised products through their performance as advertising endorsers. Then, consumers apply a final meaning transfer from the advertised products to themselves and purchase the products. It can be said that celebrities are more effective than noncelebrities because the former has a higher number of meanings than the latter (cf. Tellis 2004).

Rossiter and Percy (Citation1997) and Rossiter and Bellman (Citation2005) proposed the VisCAP and CESLIP presenter models, respectively, as frameworks to describe the types of endorsers that match the goal of marketing communications. The endorser types mentioned in the models were determined by prior models mentioned above. More recently, Schimmelphennig and Hunt (2019) tried to construct a comprehensive framework for celebrity endorsement strategies based on a vast amount of previous advertising endorsement research.

However, all existing models including comprehensive models have not described that advertising endorsers can send both verbal and non-verbal cues. Consumers receive verbal cues, i.e. the endorsers’ utterances and, at the same time, they receive non-verbal cues, i.e. gestures and other facial and body expressions, from endorsers in the ads. Therefore, an alternative model would be needed to describe endorsers as senders of both verbal and non-verbal cues.

Research on social media influencers

In recent years, with the widespread adoption of social media, advertisers are increasingly using not only ‘traditional’ celebrities such as actors, supermodels, and athletes, but also social media influencers to promote their products and services (Marwick Citation2015; Ye et al. Citation2021). Some of these influencers are unknown to consumers, while others are well-known celebrities or persons who become popular via the Internet. Campbell and Farrell (Citation2020) distinguished five categories of influencers, i.e. celebrity influencers, mega-influencers, macro-influencers, micro-influencers, and nano-influencers. According to them, the fame of celebrity influencers originates outside of social media, while other types of influencers gain their fame on social media. Campbell and Farrell argued that the primary difference among these categories lies in the number of followers, with mega-influencers having one million or more followers, macro-influencers ranging from 100,000 to one million, micro-influencers ranging from 10,000 to 100,000, and nano-influencers having fewer than 10,000 followers. According to them, macro-influencers are considered top in their specific domain with higher engagement rates compared to mega-influencers. Micro-influencers, although geographically limited, score higher on authenticity and intimacy, making their persuasive impact stronger than macro-influencers. Nano-influencers, often in the early stages of their careers, exhibit the highest engagement rates among all influencer categories.

Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman (Citation2021) conducted a bibliometric analysis of the definition given to influencers and asserted that reach and impact are two central characteristics for persons to be considered as influencers. To elaborate on how this impact can be achieved, the authors identified three crucial characteristics in obtaining a successful influencer status, i.e. expertise, authenticity, and intimacy. According to them, these characteristics may not only be crucial in determining the influencer’s impact on followers’ decision-making but also in attracting more followers and exerting a stronger influence on their decision-making.

Hudders and Lou (Citation2023) pointed out that while most prior studies had primarily focused on the positive aspects of influencer marketing for advertisers, they gave less attention to the potential risks that influencers face when they endorse products and services. According to the authors, the lives of well-known influencers are not as straightforward as they may appear. Consequently, influencers often exert continuous efforts to sustain likes and popularity, resulting in feelings of depression and pressure. Influencers frequently engage in competition to create exciting content and garner more views. Moreover, to gain followers’ trust, influencers commonly share a significant amount of personal information, sometimes losing control over how widely this information is disseminated.

In conclusion, social media influencers, excluding those with minimal influence, are more or less similar to traditional celebrities in the impact that they exert. Research on their influence on consumer response has largely adhered to traditional theoretical frameworks with expertise, trustworthiness, and intimacy as key constructs, similar to studies on celebrities.

Regulatory focus theory

As one of the latest research streams, Regulatory focus theory has been utilized in the research of persuasive communication including advertising (Higgins Citation1997, Citation1998). In general, consumer information processing to achieve their choice task has been explained based on goal achievement theories. One of the most cited theories in recent years is Regulatory focus theory, which is related to self-regulation, the control of one’s behavior including consumer choice of products through self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-reinforcement.

Prior studies have pointed out that self-regulation is involved in two types of orientation, i.e. approach motivations, with which persons try to approach what is favorable, and avoidance motivations, with which persons try to avoid what is unfavorable (Carver and Scheier Citation1982).

Research on self-regulation has been conducted mainly in the field of self-evaluation, especially self-esteem as a personal difference (cf. Tice and Masicampo Citation2008). For instance, it has been claimed that high self-esteem persons take risks for success, while low self-esteem persons avoid risks for the absence of failure (Baumeister, Tice, and Hutton Citation1989). However, contradictory evidence has been also presented. Roesch Adams, Hines, Palmores, Vyas, Tran, Pekin, and Vaughn (Citation2005) found that high self-esteem patients had more optimistic expectations than low self-esteem patients, but there was no difference in denial of their disease between the two groups. Also, in the field of help-seeking behavior, Tessler and Schwartz (Citation1972) found that low self-esteem recipients are more likely to decline helpers’ offers, while Nadler (Citation1987) found that high self-esteem recipients are more likely to do so.

Regulatory focus theory proposed by Higgins (Citation1997, Citation1998) is characterized by the notion that approach orientations can be related to non-loss as well as gain, while avoid orientations can be related to non-gain as well as loss, and that gain and non-gain are motivational goals for promotion focus, while loss and non-loss are motivational goals for prevention focus. For example, promotion focus makes persons try to purchase products they are satisfied with (gain) and avoid missing out on them (non-gain), whereas prevention focus makes persons try to avoid purchasing products they are dissatisfied with (loss) and not to fail to avoid them (non-loss).

Following Higgins (Citation1997, Citation1998), Higgins (2000) introduced a new concept, regulatory fit, to extend Regulatory focus theory. According to the extended theory called Regulatory fit theory, persons seek their goals using eager or vigilant strategies. Persons with a higher promotion (prevention) focus want to apply the former (latter) strategy because it fits their focus. If they succeed in adopting the fitted strategies, they feel ‘right’ in the adoption of the strategy, which in turn results in higher performance.

It should be noted that although there might be stable individual differences in regulatory focus, one’s focus also depends on situational factors (Higgins Citation1998; Higgins and Silberman Citation1998; Lockwood, Jordan, and Kunda Citation2002; Shah and Higgins Citation2001). For example, Lockwood et al. (Citation2002) found that positive role models instigate a promotion focus, while negative role models activate a prevention focus.

Regulatory focus theory applied to marketing and consumer studies

Regulatory focus theory and its extended theory, Regulatory fit theory, have been applied both inside and outside the research field of psychology. In the field of marketing and consumer research, many studies have been conducted since the publication of the work of Aaker and Lee (Citation2001).

Aaker and Lee (Citation2001) and Lee and Aaker (Citation2004) focused on advertisers who want to optimally frame their persuasive messages within their ads. They found that consumers with a higher promotion focus are more likely to be persuaded by promotional messages (e.g. message on vitamins and energy in juice and other persuasive messages that emphasize that customers can make a gain if they purchase the product), whereas consumers with higher prevention focus are more likely to be persuaded by prevention message (e.g. antioxidant and cancer-suppressing effects of juice and other persuasive messages that emphasize that customers can avoid making a loss if they purchase the product).

Moreover, Higgins et al. (Citation2003) and Avnet and Higgins (Citation2006) investigated the perceived value of advertised products (e.g. coffee cups and reading lights) and found that it is higher if the regulatory fit (eager strategy for promotion focus and vigilant strategy for prevention focus) occurs.

Lee, Keller, and Sternthal (Citation2010) investigated the relationship between regulatory focus and construal level (Liberman and Trope Citation1998; Trope and Liberman Citation2000) and found that advertising messages with a higher construal level (e.g. message regarding why you should exercise) have a higher persuasive effect for consumers with the promotion focus because the regulatory fit between the high construal-level message and the promotion focus occurs, whereas advertising messages with a lower construal level (e.g. message regarding how you should exercise) have a higher persuasive effect for consumers with the prevention focus because the regulatory fit between the low construal-level message and the prevention focus occurs.

Regulatory focus and non-verbal persuasive cues

As a pioneering study of non-verbal cues of persuasion based on Regulatory focus theory, Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008) focused on the effects of an endorser’s gesture styles. They reviewed some prior studies on persuasive communications with non-verbal cues (cf. Fernández-Dols and Ruiz-Belda Citation1995a, Citation1995b) and pointed out that eager gestures (e.g. animated, broad opening movements; hand movements openly projecting outwards; forward-leaning body positions; fast body movement; and fast speech rate) may convey confidence and, in some cases, recklessness, and make recipients with a promotion focus feeling right. On the other hand, vigilant gestures (e.g. pushing motions representing slowing down; slightly backward-leaning body positions; slower body movement; and slower speech rate) may convey vigilant carefulness.

In their experiments, two videos were created in which non-verbal cues were used to deliver the same persuasive message: one featured an endorser gesticulating eagerly; the other showed the same endorser gesticulating vigilantly. They found that ads with eager gestures were more effective for promotion-focused consumers, whereas ads with vigilant gestures were more effective for prevention-focused consumers. However, the endorser in that study was a schoolteacher, and thus the effects of celebrity/noncelebrity advertising endorsers in the context of the impacts of gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) remain unclear.

Recently, Fei et al. (Citation2020) explored the impact of personal temporal regulatory focus determined by non-verbal cues on consumer mindsets and favorable responses toward advertising messages. They focused on the differences between close friends and family members as non-verbal cues. According to the authors, close friends are often associated with individuals’ interests and aspirations, whereas family members are mostly associated with obligations and responsibilities. As a result, close friends trigger a promotion mindset, whereas family members induce a prevention mindset. The results of their experiments demonstrated that the accessibility of friends activates a promotion focus, resulting in more favorable consumer responses toward products with promotion-focused messages, whereas the accessibility of family members activates a prevention focus, resulting in more favorable consumer responses toward products with prevention-focused messages. However, the authors did not treat advertising endorsers and their gestures.

Jia et al. (Citation2022) explored the differential impact of the type of advertising endorsers on consumer mindsets as well as favorable responses toward advertising messages. They focused on dogs and cats as a pair of endorsers and examined on temporal regulatory focus determined by the endorser type. They found that exposure to an image of a dog made consumers promotion-focused and, thus, led to more favorable evaluations of a message framed in a promotional way, because the exposure to the dog activated a promotion-focused motivational mindset; in contrast, exposure to a cat triggered a prevention-focused mindset. This implies that exposure to pet stereotypes (typically, dogs are viewed as being open and expressive, i.e. eager, while cats are viewed as being elusive and cautious, i.e. vigilant) can shape a consumer’s mindset (promotion- vs. prevention-focused). Consequently, they found that exposure to a dog (a cat) leads to more favorable responses toward advertising messages featuring promotion- (prevention-) focused appeals. However, the authors did not extend their studies by changing the animals into human advertising endorsers. Also, they did not treat the movements of endorsers as another non-verbal cue.

Hypotheses

The effects of gestural cues on motivational mindset

As discussed earlier, this study examines the impacts of whether an endorser is a celebrity or a noncelebrity on consumer evaluations, in addition to the impacts of the endorser’s gesture style and message frame via consumer mindset change.

On the one hand, according to Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008), eager gestures that involve animated, broad opening movements, hand movements openly projecting outward, forward-leaning body positions, and fast body movement, may convey confidence and, in some cases, recklessness. Note that they focused only on stable differences among individuals in dominant regulatory focus. However, as mentioned earlier, advertising viewers’ regulatory focus can vary with situational factors (Higgins Citation1998, Higgins and Silberman Citation1998, Shah and Higgins Citation2001, Lockwood et al. Citation2002). Non-verbal cues in an ad can affect the viewers’ mindsets and, thus, the degree of the regulatory fit between the mindsets and the message frame in the ad, which in turn affects consumer evaluations of the ad and the advertised product (Fei et al. Citation2020; Jia et al. Citation2022). Therefore, consumers who are exposed to an ad with an eager gesture style are more likely to form a promotion-focused motivational mindset.

On the other hand, vigilant gestures that involve lethargic, narrowly opening movements, hand movements sparingly projecting homeward, leaning-back body positions, and slow body movement, may convey hesitation and, in some cases, cowardice (cf. Cesario and Higgins Citation2008), which encourages recipients to form a prevention-focused mindset. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

H1a: Consumers exposed to an endorser that uses eager gestures are more likely to form a promotion-focused mindset.

H1b: Consumers exposed to an endorser that uses vigilant gestures are more likely to form a prevention-focused mindset.

Celebrity endorsement as an accelerator

The type of advertising endorsers (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) has a moderating impact on consumers’ motivational mindset formation. As mentioned earlier, a celebrity can be defined as a famous person with a favorable public image, whereas noncelebrity, amateur endorsers are unfamiliar persons to consumers. What does the difference between well-known and unknown endorsers cause? The answer has been implicitly suggested by previous research.

Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008) employed a schoolteacher as an endorser of a new after-school assistance program for students in their experiment and found that the regulatory fit between the gesture type (eager vs. vigilant) of the teacher and the recipients’ mindset (promotion vs. prevention) results in more positive responses. Although they did not investigate other types of endorsers, unknown endorsers could not become influencers with greater impacts on students like schoolteachers. Unknown endorsers with eager (vigilant) gestures might be less likely to result in positive responses of the recipients with a promotion-focused (prevention-focused) mindset than schoolteachers with eager (vigilant) gestures.

Fei et al. (Citation2020) found that close friends and family members are associated with the promotion-focused mindset and the prevention-focused mindset, respectively. Although they did not investigate unknown persons, the influence of unknown persons can be inferred: The accessibility of unknown persons might be less likely to activate the promotion-focused mindset of message recipients than that of close friends. Also, the accessibility of unknown persons might be less likely to activate the prevention-focused mindset of recipients than that of family members. Because unknown persons facilitate neither the promotion-focused nor prevention-focused mindset, they could not result in more favorable responses from message recipients compared to close friends and family members.

Similarly, Jia et al. (Citation2022) found that dogs and cats are associated with the promotion-focused mindset and the prevention-focused mindset, respectively. Although they did not consider any animals other than dogs and cats, the influence of an animal that the recipients cannot decide whether to behave like a dog or a cat can be inferred: Compared to dogs, exposure to an image of an unknown animal would be less likely to make consumers promotion-focused. Also, compared to cats, exposure to an image of an unknown animal would be less likely to make consumers prevention-focused. Because unknown animals facilitate neither the promotion-focused nor prevention-focused mindset, they could not result in more favorable responses from message recipients compared to dogs and cats.

In sum, with eager (vigilant) gestures, it is easier for well-known, familiar endorsers to activate consumers’ mindset change to promotion (prevention) focus than unknown, unfamiliar endorsers. Contrarily, if the endorser is unfamiliar, consumers’ mindset change may not be activated. By definition, celebrity endorsers are famous, and thus familiar persons with favorable public image, whereas noncelebrity endorsers are unknown, unfamiliar persons. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

H2a: The impact of advertising endorsers’ eager gesture style on consumers’ promotion-focused mindset is facilitated by celebrity endorsement.

H2b: The impact of advertising endorsers’ vigilant gesture style on consumers’ prevention-focused mindset is facilitated by celebrity endorsement.

The interactive effects of gesture style, message framing, and endorser type on brand evaluation

Consumers’ motivational mindset change caused by advertising endorsers’ gestural cues may result in consumer evaluations of the advertised brand. If consumers are exposed to an advertising endorser who gives a promotion-focused message with eager gestures, they are more likely to form a promotion-focused mindset and, in turn, highly evaluate the brand under the condition that the advertising endorser is a celebrity. Similarly, if consumers are exposed to an endorser who gives a prevention-focused message with vigilant gestures, they are more likely to form a prevention-focused mindset and, in turn, highly evaluate the brand under the condition that the endorser is a celebrity. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

H3a: (1) Consumers who are exposed to a celebrity endorser giving a promotion-focused message with eager gestures evaluate the advertised brand higher than consumers who are exposed to a celebrity endorser giving a promotion-focused message with vigilant gestures. (2) There are no differences in brand evaluations between consumers who are exposed to a noncelebrity endorser giving a promotion-focused message with eager gestures and consumers who are exposed to a noncelebrity endorser giving a promotion-focused message with vigilant gesturers.

H3b: (1) Consumers who are exposed to a celebrity endorser giving a prevention-focused message with eager gestures evaluate the advertised brand lower than consumers who are exposed to a celebrity endorser giving a prevention-focused message with vigilant gestures. (2) There are no differences in brand evaluations between consumers who are exposed to a noncelebrity endorser giving a promotion-focused message with eager gestures and consumers who are exposed to a noncelebrity endorser giving a promotion-focused message with vigilant gesturers.

Experiment 1

Method

Consumers who are exposed to eager-style (vigilant-style) endorsement may form a promotion-focused (prevention-focused) mindset (H1). To test the hypothesis, the first experiment was conducted.

Stimulus

Following Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008), we created two videos, i.e. one featuring a person making eager gestures and the other featuring the same person standing without gestures. In this experiment, and all other experiments, eager gestures are to be included openly outward, accompanied by a slight forward-leaning stance, swift bodily motions, and brisk pace of speech (cf. Cesario and Higgins Citation2008). As prior studies have assumed that the effects of non-verbal cues are independent of the message content, message context, and recipients’ characteristics (cf. Siegman and Reynolds, Citation1982), the two videos in this study were set as the same except for the gesture styles. We assumed a conversation program for second language learners as the message content for both videos. No significant difference between the two groups exposed to one of the two videos was found in the mean values of respondents’ interests in second language learning. Also, there was no difference in source impression ratings of the spokesperson employed in both videos.

Participants and procedures

We recruited 108 university students from several major universities in an East Asian country who participated in the experiment (Mage = 20.8, 58 females). The number of participants was determined to be appropriate based on references to previous research (n = 90 in Cesario and Higgins Citation2008: n = 135 − 220 in Fei et al. Citation2020; n = 145 − 283 in Jia et al. Citation2022). In appreciation of their participation, they received a gift worth 2.00 USD. They were informed that our study aimed to examine individuals’ first impressions. Participants were randomly assigned to either group.

All participants in both groups were told ‘In this video, a person recommends a second language learning program for university students. Before watching the video, please answer the degree to which you are interested in second language learning’ to check random assignments. Also, they were told ‘The person in the video is someone you have never met before, and it is the first time that he is talking to you. Please write down any words that describe your impression of this person’ (cf. Fei et al. Citation2020) to make them focus on the person in the video. Moreover, as a manipulation check for eager/vigilant gesture styles, they were asked to evaluate the person in terms of the degrees of agreement on the four statements. i.e. ‘The spokesperson was openly outward,’ ‘The spokesperson was accompanied by a slight forward-leaning stance,’ ‘The spokesperson was in swift bodily motions,’ and ‘The spokesperson was at brisk pace of speech’ in seven-point Likert scaling (cf. Cesario and Higgins Citation2008), resulting in significant differences between eager gesture group (Me = 4.44, SD = 1.13) and vigilant gesture group (Mv = 2.80, SD = 1.08) (t = 7.67, p < .001).

To measure regulatory orientation, each participant was asked to complete the eleven-item Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (RFQ) (Higgins et al. Citation2001) after watching the video. The presentation order of the questions was randomized. The Cronbach’s alpha for the promotion and prevention focuses computed for internal consistency (i.e. reliability) were α = 0.80 and α = 0.75, respectively (cf. Hair et al. Citation2012). Finally, participants responded to additional questions, including demographic information.

Following Cesario and Higgins’s procedure (Citation2008), participants’ predominant focuses were calculated by subtracting the mean value for prevention focus-related items from that for promotion focus-related items. As a result, we obtained a single measurement, which indicated that the promotion focus orientation was predominant with a positive value, while the prevention focus orientation was predominant with a negative value (Hong and Lee Citation2008; Louro, Pieters, and Zeelenberg Citation2005).

Results and discussion

As a result of the t-test, we found that the mean value for the promotion focus orientation of the eager gesture group (Me = 1.31, SD = 0.37) was significantly higher than that of the vigilant gesture group (Mv = −0.72, SD = 0.54) (t = 22.59, p < .001). This result indicates that endorsers’ gestures (eager vs. vigilant) do indeed shape consumers’ regulatory focus orientation (promotion vs. prevention), implying that H1 was supported.

Some regulatory-focus literature has assumed that there are no relationships between the cues and regulatory focus, including Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008), who investigated the impacts of endorsers’ gesture styles. However, in this study, we found that the gestures of the advertising endorsers did affect the regulatory focus orientation of consumers. When exposed to an ad employing an endorser using eager gestures, promotion focus orientation was facilitated, whereas when exposed to an endorser using moderate gestures, prevention focus orientation was facilitated.

Experiment 2

Method

The effects of gestural cues on motivational mindset (H1) tested in Experiment 1 may be facilitated by celebrity endorsement (H2). To test the hypothesis, a second experiment was conducted.

Stimulus

To compare the differential impacts of celebrity and noncelebrity endorsers on the relationship between endorsers’ gesture styles and consumers’ regulatory focus, a 2 (endorser type: celebrity vs. noncelebrity) × 2 (gesture style: eager vs. vigilant) between-subjects design was utilized. We selected five pairs of existing YouTube videos in which either a famous actor or an unknown performer dancer to the music by imitating the same dance popularized by pop singers. We also selected other five pairs of videos employing either a famous actor or an unknown performer standing and talking without any gesture and muted all videos when exposing respondents to them. We took care to choose a total of ten pairs of videos in terms that they were as similar as possible in appearance, i.e. facial features, hairstyles, body shape, clothing, and movements. The only difference between celebrity and noncelebrity videos was whether the performers were well-known or not. Three investigators watched the ten pairs of videos and chose the best pair in which there was no difference in appearance and movement for each of the eager and vigilant gesture styles.

Participants and procedures

We recruited 240 undergraduate university students from several major universities in an East Asian country to participate in the experiment (Mage = 20.2, 130 females). The number of participants was determined to be appropriate based on references to previous research (n = 90 in Cesario and Higgins Citation2008: n = 135 − 220 in Fei et al. Citation2020; n = 145 − 283 in Jia et al. Citation2022). In appreciation of their participation, they received a gift worth 2.00 USD. They were informed that the experiment aimed to examine viewers’ impressions of the actor in the video.

Participants were randomly assigned to each of four groups. Before watching a video out of four videos, each participant was shown a still image of the face of the performer in the video and told ‘Before watching a video, I would like to ask you if you know the performer in the video. Are you familiar with the performer?’ (y/n). All participants in the two celebrity groups confirmed that they knew the performer, while all participants in the two noncelebrity groups confirmed that they did not recognize the performer. We also measured the expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness of a pair of performers using scale items developed by Ohanian (Citation1990). As a result, there is no significant difference between the average levels of attractiveness perceived by participants in the celebrity and noncelebrity groups, implying no effect of the endorsers’ attractiveness on consumers’ regulatory focus should be considered.

After watching a video, as in Experiment 1, respondents were asked to evaluate the person in terms of the degrees of agreement on the four statements. i.e. ‘The spokesperson was openly outward,’ ‘The spokesperson was accompanied by a slight forward-leaning stance,’ ‘The spokesperson was in swift bodily motions,’ and ‘The spokesperson was at brisk pace of speech’ (cf. Cesario and Higgins Citation2008) for a manipulation check, resulting in significant differences between eager gesture group (Me = 4.24, SD = 1.21) and vigilant gesture group (Mv = 2.54, SD = 1.02) (t = 11.59, p < .001). Participants were also asked to answer the RFQ developed by Higgins et al. (Citation2001) to measure their regulatory focus orientation in the same manner as in Experiment 1.

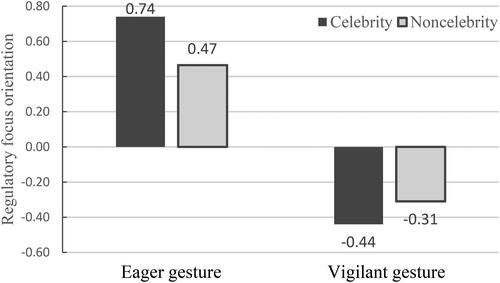

Results and discussion

The results of a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated significant main effects of gesture style (F (1, 236) = 41.16, p < .001) and endorser type (F (1, 236) = 5.24, p < .05) were found. The results also revealed a significant interaction between endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) and gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) (F (1, 236) = 26.99, p < .001). Thus, we conducted a simple main effect, suggesting that the mean value for promotion focus orientation was significantly higher in the celebrity-eager group (Mc-e = 0.74, SD = 0.57) than in the noncelebrity-eager group (Mn-e = 0.47, SD = 0.97) (F (1, 236) = 4.27, p < .05). In the vigilant groups, the results were opposite: The mean value for promotion focus orientation was significantly lower in the celebrity-vigilant group (Mc-v = −0.44, SD = 0.74) than in the noncelebrity-vigilant group (Mn-v = −0.31, SD = 0.85) (F (1, 236) = 27.73, p < .01) (see ). Those results support Hypothesis 2.

Figure 1. Interaction effects between endorse type and gesture style on promotional focus orientation in Experiment 2.

The results of Experiment 1 implied that eager gestures facilitate a promotion mindset while vigilant gestures promote a prevention mindset. The results of Experiment 2 imply that these effects are augmented by celebrity endorsement: Eager gestures are more likely to facilitate a promotion mindset if the endorser is a celebrity rather than if the endorser is a noncelebrity; vigilant gesturers are more likely to facilitate a prevention mindset if the endorser is a celebrity rather than if the endorser is a noncelebrity.

Experiment 3

Method

In Experiments 1 and 2, we tested the impacts of two factors, i.e. the endorser type and the gesture style, only on recipients’ motivational mindset. The mindset change caused by the interactions of these factors may result in consumer evaluation of the brand advertised with a certain message frame (H3). To test the hypothesis, the third experiment with a 2 (endorser type: celebrity vs. noncelebrity) × 2 (gesture style: eager vs. vigilant) × 2 (message framing: promotional vs. preventive) between-subjects design was conducted.

Stimulus

We created eight original YouTube videos about the introduction of a fictional brand of sunscreen (cf. Lee and Aaker Citation2004), featuring the same split-screen video: The right side showed the product information including a picture of the product, the fictional brand name, and all attributes, e.g. price, SPF rating, etc., while the left side showed each of the four types of performers, i.e. a dancing celebrity actor, a dancing unknown amateur YouTuber, a standing celebrity actor, and a standing unknown amateur YouTuber. As in Experiment 2, a pair of existing videos employing celebrity or noncelebrity performers were selected in terms of facial features, body shape, clothing, and behavior, and they were different from each other only in terms of whether they were well-known or unknown. The advertising message was placed along the bottom, spanning both sides of the screen. The message for promotion focus groups was ‘Let’s enjoy summer together’ whereas the message for prevention focus groups was ‘Protection from harmful UV radiation.’

Participants and procedures

In total, 312 participants (Mage = 21.2, 125 females) from several major universities in an East Asian country took part in the experiment. The number of participants was determined to be appropriate based on references to previous research (n = 90 in Cesario and Higgins Citation2008: n = 135 − 220 in Fei et al. Citation2020; n = 145 − 283 in Jia et al. Citation2022). In appreciation of their participation, they received a gift worth 2.00 USD. They were informed that the experiment aimed to investigate consumer responses to an advertised product. They were randomly assigned to one of eight groups.

As in Experiment 2, participants were shown a still image of the face of the performer in the video and asked, ‘Are you familiar with the performer?’ All participants in the four celebrity groups confirmed that they knew the performer, while all participants in the four noncelebrity groups confirmed that they did not know the performer. We also measured the expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness of performers using scale items developed by Ohanian (Citation1990), suggesting that there is no significant difference in attractiveness between the celebrity and noncelebrity employed for the fictitious ad. Moreover, we asked to participants, ‘Do you know the new sunscreen?’ and ‘Have you ever used the new sunscreen?’ and confirmed that all participants were not familiar with the product that we produced only for the product.

After watching a video, as in Experiments 1 and 2, respondents were asked to evaluate the person in terms of the degrees of agreement on the four statements. i.e. ‘The spokesperson was openly outward,’ ‘The spokesperson was accompanied by a slight forward-leaning stance,’ ‘The spokesperson was in swift bodily motions,’ and ‘The spokesperson was at brisk pace of speech’ (cf. Cesario and Higgins Citation2008) for a manipulation check, resulting in significant differences between eager gesture group (Me = 4.33, SD = 1.23) and vigilant gesture group (Mv = 2.37, SD = 0.94) (t = 15.80, p < .001). Participants were also asked to evaluate whether the provided message was associated with promotional benefits or preventive benefits (cf. Aaker and Lee, Citation2001), resulting in significant differences between promotional and preventive message farming groups. Again, the RFQ developed by Higgins et al. (Citation2001) was utilized to measure their regulatory focus orientation.

In the experiment, brand evaluations were also measured using three seven-point items anchored at ‘good/bad’, ‘favorable/unfavorable’, and ‘like/dislike’ adapted from Pham and Avnet (Citation2004). To avoid the ordering effect, the order to answer the questions for the regulatory focus orientation and those for brand evaluations were randomized for each response. Any ordering effects were observed.

At the end of the experiment, a debriefing was conducted. Participants were informed that the advertised new product is fictitious and unavailable in the real world.

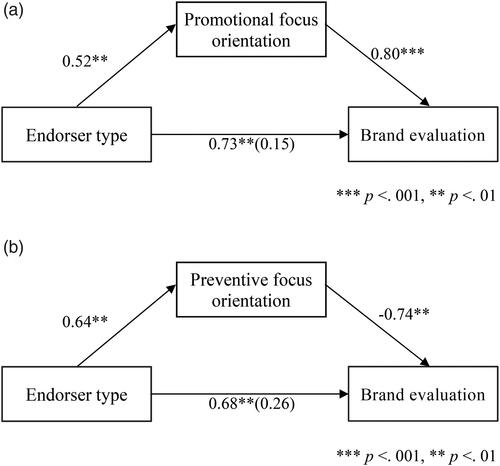

Results and discussion

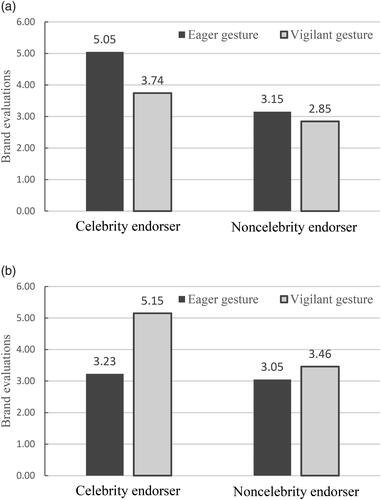

The result of a three-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of endorser type (F (1, 304) = 117.33, p < .001), whereas no significant main effects of gesture style and message framing were found (F (1, 304) = 2.78, p > .05 for gesture style; F (1, 304) = 0.06, p > .05 for message framing). Also, the two-way interactions between gesture style and message framing (F (1, 304) = 84.01, p < .001) and between endorse type and message framing were significant, whereas the two-way interaction between endorser type and gesture style was insignificant (F (1, 304) = 1.42, p > .05). The results revealed a significant interaction among the three classification variables (F (1, 304) = 34.02, p < .001). Following Wang et al.’s procedure (Citation2017), we decomposed the three-way interaction by separating a pair of 2 (endorser type: celebrity vs. noncelebrity) × 2 (gesture style: eager vs. vigilant) analyses for each kind of message framing (promotional vs. preventive).

Among the promotion-focused groups, there was a significant interaction between endorser type and gesture style (F (1, 304) = 11.27, p < .001). The results of a simple main effect test implied that advertising messages framed in a promotional way led to more favorable brand evaluations when endorsed by a celebrity with eager gestures (Mc-e = 5.05, SD = 1.06) rather than when endorsed by a celebrity with vigilant gestures (Mc-v = 3.74, SD = 0.87) (F (1, 304) = 34.56, p < .001). However, another simple main effect test revealed no significant difference in brand evaluations between noncelebrity endorsement with eager and vigilant gestures (Mn-e = 3.15, SD = 0.70; Mn-v = 2.85, SD = 1.00; F (1, 304) = 2.41, p > .10) and both values were lower than those in celebrity endorsement (See ).

Figure 2. (a) Interaction effects between endorse type and gesture style on brand evaluations in Experiment 3: Promotional message framing. (b) Interaction effects between endorse type and gesture style on brand evaluations in Experiment 3: Preventive message framing.

Among the prevention-focused groups, the interaction between endorser type and gesture style was also significant (F (1, 304) = 23.62, p < .001). The results of a simple main effect test revealed that messages flamed in a preventive way led to more favorable brand evaluations when endorsed by a celebrity with vigilant gestures (Mc-v = 5.15, SD = 0.98) than a celebrity with eager gestures (Mc-e = 3.23, SD = 0.77) (F (1, 304) = 91.35, p < .001). However, the results of another simple main effect test implied that when endorsed by a noncelebrity, gesture styles only exhibited a marginally significant influence on brand evaluations. (Mn-v = 3.46, SD = 1.13; Mn-e = 3.05, SD = 0.93; F (1, 304) = 2.98, p < .10) (see ).

As an additional examination of the causal relationship (cf. Hayes Citation2013), a bootstrap test with 5,000 resamples was conducted to test whether promotion focus orientation mediates the relationship between endorser type and brand evaluation, when the advertising message is framed in a promotional way. As a result, there was a significant indirect effect of celebrity on brand evaluation through regulatory focus orientation. (b = 0.57, SE = 0.30, 95% CI = [0.18, 0.98]) (see ). The same was done for regulatory focus orientation with a message framed in a preventive way. As a result, a significant indirect effect was found again (b = −0.57, SE = 0.28, 95% CI = [−0.92, −0.20]) (see ).

General discussion

Recently, there have been more and more vlogs in which unknown amateur performers introduce products and services like TV commercial films. Some of these vloggers have become famous and may be called ‘internet celebrities’. However, most vloggers are either unknown amateurs or at best, light influencers. Are these unknown performers effective as advertising endorsers? In other words, are well-known celebrity endorsers still more effective?

Research on advertising endorsement has a long history, and much research has been developed focusing on celebrity endorsement (e.g. Friedman and Friedman Citation1979, Atkin and Block Citation1983, Ohanian Citation1990, Raven et al. 1998). However, prior studies regarding advertising endorser types have not focused on the differences among various endorser types in the effects of their gestures as a non-verbal cue on persuasion. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have assumed the notion that consumers perceive advertising endorsers as both verbal cues, i.e. the endorsers’ utterances, and non-verbal cues, i.e. gestures. To explain the moderating effects of the endorser type (celebrity vs. non-celebrity) on the causal relationships of the gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) and the advertising message (promotional vs. preventive) via consumer motivational mindset changes, we employed the most cited goal achievement theory, Regulatory focus theory (Higgins Citation1997, Citation1998, Citation2000).

However, advertising research based on Regulatory focus theory is just getting started and it has not yet been applied to research on advertising endorsers. Only one prior study has treated gestural cues (eager vs. vigilant) without considering the endorser type (Cesario and Higgins Citation2008). Therefore, this research conducted a series of experiments to examine the interactive effects of the endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity), the gesture type (eager vs. vigilant), and the message frame (promotion-focused vs. prevention-focused). As a result of three experiments, all our hypotheses were supported.

First, whereas previous research on gestural cues from a regulatory focus viewpoint has assumed stable individual differences in dominant regulatory focus (Cesario and Higgins Citation2008), Experiment 1 in this research found that the gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) employed by endorsers influenced message recipients’ regulatory focus orientation (promotion vs. prevention). Consumers exposed to eager endorsement were likely to form a promotion-focused motivational mindset, whereas consumers exposed to vigilant endorsement were likely to form a prevention-focused mindset. Consistent with the findings of prior studies conducted outside the field of advertising (Higgins Citation1998, Higgins and Silberman Citation1998, Shah and Higgins Citation2001, Lockwood et al. Citation2002, Fei Citation2020, Jia et al. Citation2022), the results of Experiment 1 in this research imply that advertising viewers’ regulatory focus must be seen as variable under the influences of environmental factors rather than as constant.

Second, unlike previous research on gestural cues from a regulatory focus viewpoint has ignored the impacts of the endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) (Cesario and Higgins Citation2008), Experiment 2 in this research first considered the endorser type and revealed that celebrity endorsement increased the impact of the gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) on regulatory focus orientation (promotion vs. prevention) shown in Experiment 1. The results imply that consumers exposed to eager endorsement were more likely to form a promotion-focused motivational mindset when the endorser is a celebrity rather than a noncelebrity, and consumers exposed to vigilant endorsement were more likely to form a prevention-focused mindset when the endorser is a celebrity rather than a noncelebrity. Consistent with the findings of prior studies focusing on well-known endorsers such as close friends and family members (Fei et al. Citation2020), and dogs and cats (Jia et al. Citation2022), the findings of Experiment 2 in this research imply that when an advertisement employed a well-known celebrity endorser, the endorser’s impact on recipients’ mindset change was greater. The findings of the experiment also imply when the endorser is unknown to consumers, the endorser’s impact on recipients’ mindset change is smaller, whereas prior studies have neglected to consider situations in which endorsers are unknown.

Finally, while Experiments 1 and 2 focused on the endorsers’ impacts on recipients’ regulatory focus, Experiment 3 considered the endorsers’ impacts on brand evaluation via regulatory focus. The results of the experiment imply that consumers exposed to a celebrity endorser with an eager gesture style were likely to form a promotion-focused motivational mindset and, in turn, evaluate the advertised brand highly with a promotion-focused advertising message. In contrast, when consumers were exposed to a celebrity endorser using vigilant gestures, their regulatory mindset was likely to become prevention-focused, and the advertised brand was evaluated highly with the prevention-focused message framing.

Unlike previous advertising research on the endorsement type, this study succeeded in constructing a model assuming celebrity endorsers can send not only verbal cues, but also gestural cues, and describing that gestural cues of persuasion can shape consumers’ regulatory focus orientation, where eager gestures tend to trigger a promotion mindset and vigilant gestures promote a prevention mindset (Experiment 1), the effects are augmented by celebrity endorsement (Experiment 2), and, in turn, celebrity endorsement accelerating the impacts of gesture on regulatory focus results in higher evaluations of the advertised brand (Experiment 3).

Theoretical contributions

As mentioned earlier, the role of celebrity endorsers has long been discussed based on classical models developed decades ago. All these existing models have lacked the notion that consumers utilize advertising endorsers as verbal cues, i.e. utterances, and non-verbal cues, i.e. gestures and other facial and body expressions, as well as the endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) itself, to achieve their goal to choose a proper brand. By newly applying Regulatory focus theory to celebrity endorsement research, this research contributed to the research field of advertising endorsement.

There have been prior studies on non-verbal persuasive cues based on Regulatory focus theory. However, they were insufficient to be employed in advertising research regarding celebrity endorsement. The pioneering study considered the interaction effect of promotional vs. preventive message framing (a verbal cue) and eager vs. vigilant gesture style (a non-verbal cue) and ignored the impact of endorser type (celebrity vs. noncelebrity) as another non-verbal cue (Cesario and Higgins Citation2008). Moreover, the research assumed stable individual differences in dominant regulatory focus, though information receivers’ regulatory focus can vary with situational factors including persuasive cues of the information sources. The following studies, in contrast, assumed that regulatory focus could be influenced by persuasive cues and considered the interaction effect of promotional vs. preventive message framing and the endorser type (Fei et al. Citation2020, Jia et al. Citation2022). However, these studies ignored the impact of the gesture style. Moreover, the endorser types that they treated were friends vs. family and dogs vs. cats. No previous research has been conducted to examine whether the message sender is a familiar person (celebrity) or an unknown person (noncelebrity). Thus, it can be said that this research contributed also to Regulatory focus theory as the first research examined the impacts of two kinds of non-verbal cues (endorser type and gesture style) as well as verbal cues (utterances).

Managerial implications

Today, not only large companies but also small firms and consumers promulgate product information on the Internet. Many small advertisers post inexpensive video ads online and amateur performers also post video logs that introduce and evaluate many kinds of products and services. In addition, to create and supply a series of personalized ads and make their ads effective, even large companies have become more inclined to employ noncelebrity endorsers in their online ads to save costs. However, our experiments imply that celebrity endorsement may be effective not only in terms of their popularity, as classical endorsement studies have suggested, but also in terms of augmenting the effects of a regulatory fit of verbal and gestural cues on consumer evaluations of the advertised product. Therefore, advertisers should reconsider featuring celebrity endorsers in their ads. When they cannot employ celebrities, they should employ a particular unknown person continuously until that person becomes a famous performer on the Internet.

Also, in contrast to previous research, we found that consumers do not have an inherent mindset; Their motivations can be shaped by the gesturing strategy. Therefore, advertisers do not need to consider the regulatory fit between an endorser’s style of gestures and consumers’ regulatory focus, because the gesture style can influence consumers’ regulatory focus and a regulatory fit between them can be accomplished to a certain extent. Rather, advertisers should ensure a regulatory fit between an endorser’s style of gestures—and thus the recipients’ regulatory focus—and the advertising message frame. And again, the effects of this regulatory fit can be more effective in celebrity endorsement.

Limitations

Although this study obtained much richer findings than previous research, our experiments have some limitations. First, due to the limitations of time, we recruited university students as the participants in our experiments. This choice brings forth the advantage of anticipating homogeneity in specific characteristics or conditions among the participants. Consequently, the experimental results are expected to have higher reliability compared to collecting participants with diverse attributes, leading to an enhancement in the internal validity of the research. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential drawback, as there is a possibility of reduced external validity. To avoid the risk that the results may not apply to the broader population, other kinds of participants should be recruited.

Also, our experiments considered only two endorsers for one fictional product. It would be worthwhile to experiment with more endorsers and products to examine the external validity of our hypotheses. Moreover, this study focused on the celebrity vs. noncelebrity dichotomy and assumed typical consumers are familiar with well-known celebrity endorsers, while they are unfamiliar with unknown noncelebrity endorsers. However, the construct of familiarity has been treated as a continuous variable. We may have to investigate various endorsers with different levels of familiarity, instead of a pair of well-known and unknown endorsers.

Future research

Following previous research, this research treated the dichotomy of eager vs. vigilant as gesture style. However, as suggested earlier, the gesture styles have multi-dimensional elements including body movement, hand movement, body position, and speech rate: According to Cesario and Higgins (Citation2008), the eager gesture style is associated with animated, broad opening movements, hand movements openly projecting outwards, forward-leaning body positions, fast body movement, and fast speech rate, whereas the vigilant gesture style is associated with pushing motions representing slowing down, slightly backward, leaning body positions slower body movement, and slower speech rate. However, this research as well as previous research did not investigate which dimensions promote a promotion- (prevention-) focused mindset better than other dimensions. Identification of elements that have greater impacts on the recipients’ motivational mindsets will be an important challenge in the future.

Celebrities, by definition, are well-known persons to advertising viewers. Some celebrities may be known for comedic roles, whereas others may be known for tragic roles. If the celebrity has a comedic role, but his or her gestures are minimized in the ad, the vigilant gesture style might be assimilated by the comedic role and, therefore, make consumers’ mindsets inclined towards a promotion focus. Conversely, contrasting with the known role, the ad viewers’ mindset may tend towards a prevention-focused mindset. Similarly, if the celebrity has a tragic role, but his or her gestures are exaggerated in the ad, the eager gesture style might be assimilated by the tragic role and, therefore, make consumers’ mindsets inclined towards a prevention focus. Conversely, contrasting with the known role, the ad viewers’ mindset may tend towards a promotion-focused mindset. Further exploration is needed to delve into the topic.

According to the Persuasion knowledge model, celebrity endorsement may lead to not only weak persuasive effects of the ad, but also ad avoidance because consumers perceive it as a compensated appearance (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). Although the findings of this research imply the opposite—celebrity endorsement had a positive impact on consumer evaluations of advertised products, future research should consider this kind of consumer knowledge when estimating a new model. Regarding the issue, it should be noted that not only celebrity endorsers but also amateur vloggers, catering to a small number of viewers, may be paid by the firm to introduce its product. It will be an interesting topic to examine which is more effective in persuasion: celebrities, who are paid performers, or amateur vloggers, who are unsure whether they are paid or unpaid.

This research focused on the celebrity vs. noncelebrity dichotomy when discussing the influences of the gesture style on consumer evaluation. However, some prior studies on advertising endorsers have treated other types of endorsers such as technical experts, company employees, and animated characters though they have not considered the gesture style. Future research can explore the differences among various endorser types with consideration of the gesture style.

Finally, recent endorsement research has explored endorsers’ stylistic properties, i.e. camera angle and visual perspective, instead of the endorser type (Yang, Zhang, and Peracchio Citation2010. Zhang and Yang Citation2015). According to the authors, consumer evaluations of the advertised product may vary with whether the advertising endorser is captured from an actor’s visual perspective or an observer’s visual perspective. However, the gesture style has not been considered because previous studies have examined still images. Shifting the subject of research from still images to videos, future studies can employ the framework of this current research and model the relationship between two non-verbal cues, i.e. visual perspective (an actor’s vs. observer’s perspectives) and gesture style (eager vs. vigilant) along with a verbal cue (advertising message).

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Professor Charles R. Taylor, Professor Yung Kyun Choi, Professor Jihee Song, and anonymous reviewers for their fruitful comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The fictitious ads and the datasets in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaker, J.L, and A.Y. Lee. 2001. “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: The role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research 28, no. 1: 33–49.

- Atkin, C., and M. Block. 1983. Effectiveness of celebrity endorsers. Journal of Advertising Research 23, no. 1: 57–61.

- Avnet, T., and E.T. Higgins. 2006. How regulatory fit affects value in consumer choices and opinions. Journal of Marketing Research 43, no. 1: 1–10.

- Baumeister, R.F., D.M. Tice, and D.G. Hutton. 1989. Self-presentational motivations and personality-differences in self-esteem. Journal of Personality 57, no. 3: 547–79.

- Carver, C.S, and M.F. Scheier. 1982. Control theory: A useful framework for personality-social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin 92, no. 1: 111–35.

- Biswas, D., A. Biswas, and N. Das. 2006. The differential effects of celebrity and expert endorsements on consumer risk perceptions: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived congruency, and product technology orientation. Journal of Advertising 35, no. 2: 17–31.

- Campbell, C., and J.R. Farrell. 2020. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons 63, no. 4: 469–79.

- Carrillat, F.A, and J. Ilicic. 2019. The celebrity capital life cycle a framework for future research directions on celebrity endorsement. Journal of Advertising 48, no. 1: 61–71.

- Cesario, J., H. Grant, and E.T. Higgins. 2004. Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from "feeling right. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86, no. 3: 388–404.

- Cesario, J., and E.T. Higgins. 2008. Making message recipients “feel right”: how nonverbal cues can increase persuasion. Psychological Science 19, no. 5: 415–20.

- Fei, X.Z., Y.F. You, and X.J. Yang. 2020. “We” are different: Exploring the diverse effects of friend and family accessibility on consumers’ product preferences. Journal of Consumer Psychology 30, no. 3: 543–50.

- Fernández-Dols, J.M, and M.A. Ruiz-Belda. 1995a. Expression of emotion versus expressions of emotions: Everyday conceptions about spontaneous facial behavior. In Everyday conceptions of emotion: An introduction to the psychology, anthropology and linguistics of emotion, eds. J.A. Russell, J.M. Fernández-Dols, A.S.R. Manstead, and J.C. Wellenkamp, 505–22. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer.

- Fernández-Dols, J.M, and M.A. Ruiz-Belda. 1995b. Are smiles a sign of happiness? Gold medal winners at the Olympic games. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69, no. 6: 1113–9.

- Freiden, J.B. 1984. Advertising spokesperson effects—An examination of endorser type and gender on 2 audiences. Journal of Advertising Research 24, no. 5: 33–41.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research 21, no. 1: 1–31.

- Friedman, H.H, and L. Friedman. 1979. Endorser effectiveness by product type. Journal of Advertising Research 19, no. 5: 63–71.

- Hair, J.F., N. Sarstedt, C.M. Ringle, and J.A. Mena. 2012. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40, no. 3: 414–33.

- Hayes, A.F. 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Higgins, E.T. 1997. Beyond pleasure and pain. The American Psychologist 52, no. 12: 1280–300.

- Higgins, E.T. 1998. Promotion, and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in experimental social psychology 30, ed. M.P. Zanna, 1–46. New York: Academic Press.

- Higgins, E. T. 2000. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist 55, no. 11: 1217–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.11.1217

- Higgins, E.T., R.S. Friedman, R.E. Harlow, L.C. Idson, O.N. Ayduk, and A. Taylor. 2001. Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology 31, no. 1: 3–23.

- Higgins, E.T, and D.C. Molden. 2003. How strategies for making judgments and decisions: Motivated cognition revisited. In Foundations of social cognition: A festschrift in honor of Robert S. Wyer Jr., eds. R.S.Wyer, G.V.Bodenhausen, and A.J. Lambert, 211–33. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Higgins, E.T., L.C. Idson, A. L. Freitas, S. Spiegel, and D.C. Molden. 2003. Transfer of value from fit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84, no. 6: 1140–53.

- Higgins, E.T., and I. Silberman. 1998. Development of regulatory focus: Promotion and prevention as ways of living. In Motivation and self-regulation across the life span, eds. J.Heckhausen and C.S.Dweck, 78–113, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hong, J., and A.Y. Lee. 2008. Be fit and be strong: Mastering self-regulation through regulatory fit. Journal of Consumer Research 34, no. 5: 682–95.

- Hovland, C.I, and W. Weiss. 1951. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly 15, no. 4: 635–50.

- Hovland, C.I., I.L. Janis, and H.H. Kelley. 1953. Communication and persuasion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hudders, L., S. De Jans, and M. De Veirman. 2021. The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising 40, no. 3: 327–75.

- Hudders, L., and C. Lou. 2023. The rosy world of influencer marketing? Its bright and dark sides, and future research recommendations. International Journal of Advertising 42, no. 1: 151–61.

- Jia, L., X.J. Yang, and Y.W. Jiang. 2022. The pet exposure effect: Exploring the differential impact of dogs versus cats on consumer mindsets. Journal of Marketing 86, no. 5: 42–57.

- Kim, W., Y. Ryoo, S.Y. Lee, and J.A. Lee. 2023. Chatbot advertising as a double-edged sword; the roles of regulatory focus and privacy concerns. Journal of Advertising 52, no. 4: 504–22.

- Kirmani, A., and R. Zhu. 2007. Vigilant against manipulation: The effect of regulatory focus on the use of persuasion knowledge. Journal of Marketing Research 44, no. 4: 688–701.

- Lee, A.Y, and J.L. Aaker. 2004. Bringing the frame into focus: The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86, no. 2: 205–18.

- Lee, A. Y., P. A. Keller, and B. Sternthal. 2010. Value from regulatory construal fit: The persuasive impact of fit between consumer goals and message concreteness. Journal of Consumer Research 36, no. 5: 735–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/605591

- Liberman, N., and Y. Trope. 1998. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75, no. 1: 5–18.

- Liu, M.T., Y.-Y. Huang, and J. Minghua. 2007. Relations among attractiveness of endorsers, match-up, and purchase intention in sport marketing in China. Journal of Consumer Marketing 24, no. 6: 358–65.

- Lockwood, P., C.H. Jordan, and Z. Kunda. 2002. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83, no. 4: 854–64.

- Louro, M.J., R. Pieters, and M. Zeelenberg. 2005. Negative returns on positive emotions: The influence of pride and selfregulatory goals on repurchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research 31, no. 4: 833–40.

- Markman, A.B., G.C. Baldwin, and W.T. Maddox. 2005. The interaction of payoff structure and regulatory focus in classification. Psychological Science 16, no. 11: 852–5.

- Marwick, A.E. 2015. Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public Culture 27, no. 1: 137–60.

- McCracken, G. 1989. Who is the celebrity endorser – cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research 16, no. 3: 310–21.

- McGuire, W.J. 1985. Attitudes and attitude change. In Handbook of social psychology 2, eds. G. Lindzey and E. Aronson, 233-346. New York: Random House.

- Monga, A., and R. Zhu. 2005. Buyers versus sellers: How they differ in their responses to framed outcomes. Journal of Consumer Psychology 15, no. 4: 325–33.

- Nadler, A. 1987. Determinants of help seeking behavior: The effects of helper’s similarity, task centrality and recipient’s self-esteem. European Journal of Social Psychology 17, no. 1: 57–67.

- Ohanian, R. 1990. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising 19, no. 3: 39–52.

- Pashupati, K. 2009. Beavers, bubbles, bees, and moths: An examination of animated spokescharacters in DTC prescription-drug advertisements and websites. Journal of Advertising Research 49, no. 3: 373–93.

- Petty, R.E., J.T. Cacioppo, and D. Schumann. 1983. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research 10, no. 2: 135–46.

- Priester, J.R, and R.E. Petty. 2003. The influence of spokesperson trustworthiness on message elaboration, attitude strength, and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Psychology 13, no. 4: 408–21.

- Pham, M.T, and T. Avnet. 2004. Ideals and oughts and the reliance on affect versus substance in persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research 30, no. 4: 503–18.

- Pham, M.T, and H.H. Chang. 2010. Regulatory focus, regulatory fit, and the search and consideration of choice alternatives. Journal of Consumer Research 37, no. 4: 626–40.

- Raven, B. H., J. Schwarzwald, J., and M. Koslowsky. 1998. Conceptualizing and measuring a power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 28, no. 4: 307–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15591816.1998.tb01708.x

- Roesch, S.C., L. Adams, A. Hines, A. Palmores, P. Vyas, C. Tran, S. Pekin, and A.A. Vaughn. 2005. Coping with prostate cancer: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 28, no. 3: 281–93.