ABSTRACT

This paper explores the integration of Urban Digital Twin (UDT) technology in Melbourne’s Greenline Project, focusing on a performance-based framework that aligns with Sustainable Development Goals and city-specific sustainability objectives. Recognising the complexities of urban ecosystems while anchoring on human-centric ‘placemaking’ – a participatory process involving the planning, design, and management of public spaces – the key capabilities and challenges in developing, implementing and applying UDTs and related technologies to achieve these objectives are reviewed and synthesised. Challenges in data collection and/or access, their use and integration into decision-making processes and capturing the dynamic interaction between physical and virtual environments, including updating UDT models are highlighted. The review emphasises the role of urban planners and stakeholders in driving UDT development and applications by better understanding and stating objectives, leveraging interdisciplinary collaboration for effective technology application, crucial for robust data management, analytics, and community contribution. International examples illustrate the potential utility of Digital Twins in enhancing urban planning, design, and operational management. The paper presents a preliminary framework to guide the further development of the Greenline Project and inform future research that is needed for improved and effective deployment and use of UDTs in other urban revitalisation projects.

Practitioner pointers

Urban planners have a central role in directing Urban Digital Twin technologies to address socio-economic and sustainability challenges facing cities and communities.

Interdisciplinary collaboration, skills development, user-friendly technologies and sharing of real-time spatial data will drive innovation and support sustainable urban development.

Developing performance frameworks will enhance planning and design practice, project monitoring and management and communications related to sustainable urban regeneration.

Introduction

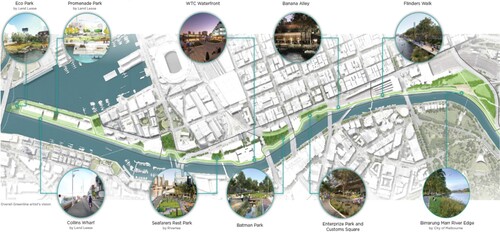

The Greenline Project is a $300 million major urban regeneration proposal that aims to transform four kilometres of public space along the north bank of the Yarra River – Birrarung in Central Melbourne (CoM Citation2021a) and ‘create a series of ecologically and culturally rich spaces that connect people, to their city and the water’ (TCL Citation2022). Planned to be delivered in stages across five precincts as multiple projects to 2028, it is an ambitious local project that also seeks to contribute to the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Or, stated from another perspective, it is a project with global impact aspirations but especially focused on meeting the local need for high-quality urban spaces that positively contribute to the enjoyment and overall quality of life of the city’s residents and visitors.

Such projects with significant global and local (‘glocal’) goals (Allan et al. Citation2021) and impact potential also have the opportunity to support the development of a sustainability assessment framework for placemaking (i.e. to assess and compare alternative concepts and solutions in a comprehensive and consistent manner) and demonstrate the applicability and value of a digital environment or platform to develop and evaluate or assess new concepts and innovative solutions that meet the desired outcomes that are set through this performance-based framework. With these types of tools and frameworks, the ability to extend and multiply the innovation and transformation potential of other placemaking initiatives – big or small, beyond Melbourne’s Greenline Project – will be enhanced or magnified.

The utilisation of digital technology to more effectively and efficiently plan and report project performance is a high-level aim. In 2023, the City of Melbourne with the Victorian Government’s Department of Transport and Planning will complete a 3D Photo Mesh survey providing the basis of a 3D digital model of the Greenline Project, a precursor to the development of a Digital Twin, which is defined as ‘a virtual representation of a physical system (and its associated environment and processes) that is updated through the exchange of information between the physical and virtual systems’ (VanDerHorn and Mahadevan Citation2021).

The Greenline is a partnership project led by the City of Melbourne, involving the Australian, and Victorian Governments, stakeholders, and the community.

Currently in the planning phase, implementation of the Greenline will fast-track the delivery of individual projects including the first project in the Birrarung Marr Precinct, known as Site One, the project is scheduled to commence construction in the second half of 2023. The final project, in Saltwater Wharf Precinct is scheduled to begin in 2025. The overall Greenline site plan, key locations and before and after images are illustrated in .

Figure 1. The Greenline Project Site Plan and Key Locations (CoM Citation2022a).

Figure 2. Before – Existing rivers edge adjacent to Flinders Street Station, Melbourne (CoM Citation2021a).

Figure 3. After – An artist impression Flinders Walk – the Greenline Project (CoM Citation2021a).

Key objectives for the Greenline Project relate to revitalisation of place around four themes; culture, place, connection and the environment, together with an economic objective to attract additional investment within the corridor and to increase commercial and visitor activation (CoM Citation2021a).

This paper aims to explore the challenges and opportunities in implementing UDTs and related digital technologies in major urban regeneration projects, with the City of Melbourne’s Greenline Project as the main focus, considering its context and ambitious sustainability objectives. This approach is intended to guide the further development of this project and inform the types of further research needed to support a more general framework for improved and effective deployment and use of UDTs in future urban revitalisation and regeneration projects elsewhere.

Methodology

The methodology applied in this paper involves a review of literature and synthesis of views and observations utilising the authors’ roles as researchers and urban practitioners.

Digitalisation and urban planning

Public agencies, local governments and research institutions are increasingly looking to digital and smart city technologies to address the social, economic, and environmental challenges facing cities and communities. This includes the use of a range of rich data platforms, urban systems modelling and analytics methods and tools, including Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications for community engagement, participatory planning and placemaking which despite current challenges and limitations indicates a strong potential to enhance decision-making processes (Du et al. Citation2023). Building resilience and urban sustainability is another goal combined with the delivery of more efficient and equitable infrastructure and services to meet the needs of urban populations. Advances in Information Communication Technology (ICT) have driven significant societal changes including the way people interact, move around, and connect with one another in cities. Fuelled by technological innovation and digital connectivity there is a rush within business and government to digitalisation, seeking to put ‘everything on-line’ through ‘e-business, e-commerce and e-services’ channels (Ha Citation2022 in, Burinskienė and Seržantė Citation2022).

Better understanding people’s day to day interactions with the natural and built environment through digital platforms will assist city administrators in identifying urban patterns and information data with the potential to assist the management of urban public space. Delivering urban renewal and undertaking public realm improvements is more likely to be successful if delivered in partnership with communities (Ellery, Ellery, and Borkowsky Citation2021). ICT, data analytics and digital technologies have strong potential to assist urban planning practice, community engagement, urban design and in ‘placemaking’ – the collaborative processes of planning, design, and management of public space (Houghton, Miller, and Foth Citation2014).

Although the development and implementation of digital platforms are beyond the broad skill sets of most planners, the formation of multidisciplinary alliances involving planners and ICT specialists from data science, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Building Information Modelling (BIM) indicates high potential for collaborative outputs (Houghton, Miller, and Foth Citation2014). Currently, there are few instances of urban analytics and/or AI platforms being used by urban planners in practice in a sustained manner. There is, however, strong interest in the future use of AI in the design of place, and development and transport planning, sustainability (energy, water and waste management) although at present this is constrained by limited knowledge and technical skills, but with high potential to be progressed by further research (Sanchez et al. Citation2023). The increased application of smart city technologies and digitalisation to address urban socioeconomic challenges suggests a more central role for urban planners in directing these technologies in the urban realm (Sabri and Witte Citation2023).

Progress towards a more digitally connected knowledge-enabled smart city that responds in practical ways to the changing needs of the community is an objective of the City of Melbourne (CoM Citation2023a). The city currently monitors, maps, and provides a variety of publicly accessible online geospatial open data platforms including the City of Melbourne Maps (COMPAS), Development Activity Model (3D development approval information) and the Mapping Aboriginal Melbourne programs. In addition, the city’s smart city incubator team explores digital and data applications via its collaborative Emerging Technology Testbed program which explores technological impacts at the scale of the city, community and individual. The program includes a range of projects and initiatives including ‘Micro-Lab’ to reimagine retail, and a partnership with Climasens to develop a ‘new tool to map heat hazards and strength responses to extreme heat events’, utilising movement and microclimate sensors to inform the design of public space and support data-led decision making (CoM Citation2023b).

The past two decades have seen significant advances in the implementation of digital applications to the built environment, property and construction, and community participation (Batty Citation2018 and Pietzsch Citation2022). This includes a move from 2D to 3D computer-generated renders and visualisations used by proponents to communicate development proposals and to engage citizens and authorities in the evaluation and determination of development approval applications. While the use of increasingly sophisticated web-based 3D interactive models to communicate proposals presents clear benefits to planners and applicants, whether public participation is always improved using technology is debatable – as not all participants have access to computers, or the internet nor are they equally ‘tech-savvy’ (Judge and Harrie Citation2020).

Digital technologies are used by public agencies to monitor activities within the public realm, survey stakeholders and analyse data to inform urban planning decisions. In the City of Melbourne, planning permit applications are now commonly lodged, registered and advertised online allowing applicants and submitters to login to monitor progress and or present to or attend live-streamed meetings of Council and decision-making committees. Local governments typically prepare annual budgets containing capital and operational expenditures outlining investments in urban infrastructure and service delivery. These are often based on strategic plans covering multi-year timeframes, the City of Melbourne’s Council Plan 2021–2025, an example of this. Increasingly city administrators are focusing on digitalisation and innovation to generate efficiencies, solve issues, and save costs while seeking to maintain service delivery levels (Lehtola et al. Citation2022). The City of Melbourne also has commitments to extend the provision of online information and investigation of further digitising operations and developing Digital Twin technology (CoM Citation2021b).

Urban Digital Twins

Digital and geospatial platforms including Digital Twin technologies are increasingly being developed and adapted for use in urban planning. Originally created for use in the aerospace and manufacturing industries some twenty years ago, these technologies are increasingly being applied to natural and built environments. The combination of systems monitoring, and data analytics enabled by advanced sensors and the Internet of Things (IoT) has facilitated the creation of interactive digital simulations of physical assets with the capacity to test performance and evaluate scenarios (Cureton and Dunn Citation2021). The UDT creates an interactive computer model of the physical city, which in one view of the World Economic Forum, April 2022, has a twofold goal: (1) ‘solve complexity and uncertainty of urban planning, design, construction, management and services through simulation, monitoring, diagnosis, and control’, and (2) ‘establish the simultaneous operation of an interaction between the physical and digital dimensions of the city’ with four features: (a) accurate mapping, (b) analytical insight, (c) virtual real interaction; and (d) intelligent intervention (WEF Citation2022).

There is a multiplicity of definitions used to describe a UDT. Considering the term in its constituent parts can assist our understanding – i.e. ‘Urban’ relating to, town, city or built-up area, ‘Digital’ to electronic technology and ‘Twin’ to a matching pair. The current ambiguity and lack of a single agreed definition of a UDT results in the term being applied ubiquitously to describe various digitalisation projects and programs. Helsinki’s smart city platform, the 3D city model of ETH Zurich, Virtual Singapore, and flood evacuation modelling in Dublin Ireland, are all variously described as UDTs. Although not all of these projects yet represent a fully functional UDT, each has elements that allow urban practitioners and decision makers to monitor and report on some aspects of performance. Increasingly, UDT technologies are being enhanced to improve visual communications and engagement with citizens and to forecast environmental, social and economic parameters and predict urban futures (Ye et al. Citation2022).

While conceptually connecting aspects of the physical and digital realms through data is achievable, the notion of fully functioning real and virtual worlds interacting in real time currently presents a considerable and possibly unassailable challenge (Tomko and Winter Citation2019). The necessity of developing individual use cases for the multiplicity of dynamic urban systems drives a diversity of outputs typically all labelled ambiguously as a Digital Twin further blurs the concept and creates additional uncertainty (van der Valk et al. Citation2021). While the general concept of a UDT may find some common ground, proposed definitions and thus understandings vary. In any case, there remains a high level of interest in Digital Twins both in practice and in research.

There are distinctions and parallels between the transformative impacts of City Information Models (CIM) and UDTs and the potential improvements in traditional inclusive decision-making processes, however, despite more user-friendly 3D visualisations (like CoM’s COMPASS, etc.) increasing equitable accessibility for local stakeholders and non-experts remains a challenge (Najafi et al. Citation2023).

There are considerable limitations on our ability to replicate physical urban, natural and social systems in real time given the dynamism and complexity of these urban systems, however, the concept of a Digital Twin city and potential applications to sustainability is improving (WEF Citation2022). Recent developments in computer software, on-site monitors and sensors and process engineering have expanded the contribution of Digital Twin applications to urban sustainability and smart cities. Technological advances in the last ten years have increased decision support for governments and stakeholders indicating good potential to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs (Tzachor et al. Citation2022).

As stated above, while there is no singularly accepted definition of a Digital Twin applied to the built and urban environment, the Australian and New Zealand Land Information Council (ANZLIC) uses the following description, ‘A Digital Twin is a dynamic representation of a real-world object or system’ (ANZLIC Citation2019). There is a need to develop holistic planning and implementation definitions, policies and strategies in Australia to optimise the potential of urban Digital Twins and address key challenges one of which is the need for guidance around best practice (Standards Australia et al., Citation2023). The use of data-driven multi-faceted digital replicas of the real world to promote sustainable urban practice is gaining momentum including for use in collaborative community engagement processes (Shahat, Hyun, and Yeom Citation2021). Careful management of these processes and transparent governance frameworks are necessary to mitigate unintended consequences and promote ethical use and protect privacy and gain the full benefit of citizen participation (Cappa, Franco, and Rosso Citation2021 and Bohnsack, et al., Citation2022).

UDT applications and trends

UDTs combine well with Augmented Reality (AR) (digital imagery overlayed on the actual world) and Virtual Reality (VR) (entirely digital images) (Farshid et al. Citation2018) to provide urban stakeholders with an ability to improve urban resilience by testing responses and scenarios. Sharing enhanced semi-realistic experiences of projects prior to construction or considering alternative scenarios before implementation enhances disaster preparedness and recovery. Further development of these technologies will greatly assist efforts to plan for disruptions and disasters exacerbated by extreme weather events and the impacts of climate change (Ye et al. Citation2022).

As stated above, digital infrastructures and UDTs are being applied in strategic planning and urban management in several cities including Singapore, Shanghai, Zurich and for the Fishermens Bend precinct in central Melbourne. Recent case study research in the Netherlands documented in Najafi et al. (Citation2023) outlines a high potential for systematic approaches for the use of CIM and other technologies for community collaboration. Presenting visually rich 3D imagery including UDTs to aid decision-making presents challenges, including selecting the correct workflow, understanding user profiles, the user friendliness of virtual models and systematic training/processes. Other examples include a partnership project being led by the NSW Government with Data61 and the CSIRO for a ‘Digital Twin proof-of-concept model to support multistakeholder participation in urban planning’. An accurate 4D framework for a Digital Twin of Western Sydney has been developed to facilitate collaboration and sharing of spatial data in real time with the stated aim to assist urban practitioners to design and manage future cities. ‘Twenty-two million trees, 540,000 buildings, 7,000 strata plans and close to 20,000 kilometres of roads have been mapped’ and making this data available to the public is a key aim combined with improved and more convenient delivery of government services (WEF, April Citation2022).

Current trends in the development of Digital Twins indicate increasing functionality, adaptability and autonomy applied across a range of industries and in a variety of private and public settings. In the context of an organisation, van der Aalst, Hinz, and Weinhardt (Citation2021) describe a progression from ‘Digital Model’, ‘Digital Shadow’, ‘Digital Twin’ to ‘Resilient Twin.’ Others such as, van der Valk et al. (Citation2021) describe these trends as five Digital Twin archetypes each evolving in capability from (1) ‘Basic Digital Twin’, (2) ‘Enriched Digital Twin’, (3) ‘Autonomous Control Twin’, (4) ‘Enhanced Autonomous Control Twin’ to (5) ‘Exhaustive Digital Twin’. To optimise the use of digital technologies in placemaking and other forms of participatory planning the trend of increasing technical sophistication will need to be aligned with increased user-friendly applications for locals and non-experts.

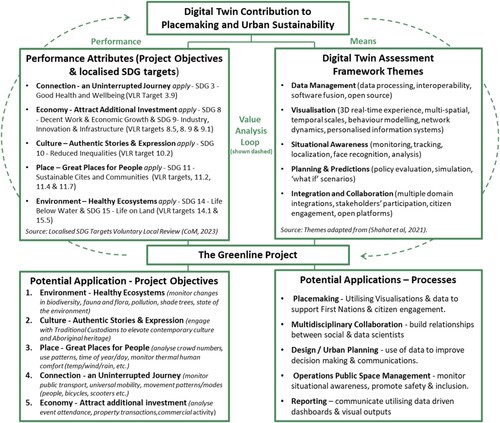

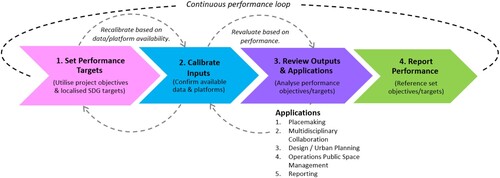

UDTs seek to analyse data and information from multiple sources, and increasingly apply artificial intelligence and machine learning, mimicking some actual physical conditions with an in-built capacity to monitor performance in real time and predict some behaviours (Lu et al. Citation2020). A systematic literature review undertaken by Shahat, Hyun, and Yeom (Citation2021), identified the potential application of Digital Twins to urban environments under five themes: (1) ‘Data Management’, (2) ‘Visualization’, (3) ‘Situational Awareness’, (4) ‘Planning and Prediction’ and (5) ‘Integration and Collaboration’. These five high-level groupings assist, not only in thinking about the ways Digital Twin technologies can be applied but also in setting performance targets, inputs and adapting outputs for individual projects or specific environments. summarises a four-step performance assessment approach (Foliente et al. Citation2005) overlayed on an implementation sequence for the Greenline Project adapting the themes identified by Shahat, Hyun, and Yeom (Citation2021).

Figure 4. Sequential Steps to Develop a Digital Twin Framework for the Greenline Project (Performance loop adapted from Foliente et al.,Citation2005 and Applications adapted from Shahat, Hyun, and Yeom Citation2021).

A Digital Twin for the Greenline Project

In 2022 the City of Melbourne appointed a multidisciplinary consortium led by Aspect TCL to develop a Master Plan for the Greenline Project. A key component of the Master Plan is the development of a digital strategy including a proof-of-concept for a Digital Twin. This innovation presents a first for the City of Melbourne with strategic opportunities to design and implement new approaches to digital urban infrastructure and the management of project performance.

Measuring project performance

The Greenline Project as a people-centric urban renewal program which prioritises objectives related to improving ‘places for people’ while protecting the environment and enhancing natural, physical, and community assets. Together with building urban resilience (the capacity to withstand and respond to short and long-term hazards) while contributing to the city economy. Improving the functionality and amenities of dilapidated places can positively impact related socio-economic challenges, usually but not exclusively, the result of environmental degradation (Roberts, Sykes, and Granger Citation2016). Digital platforms are already being used to gather data and analyse movement patterns, and the performance of the health of physical and natural assets including trees, shade, and canopy cover. Adding social and urban sustainability measures is a future goal and is reliant upon identifying the right performance measures and ensuring platform and data availability and analytical capacity.

Applying the Sustainable Development Goals to the Greenline Project

The 2022 Greenline Business Case analysed the delivery of the project against triple-bottom line outputs, forecast over a 20-year investment period 2021–41. Additionally, the Greenline Business Case outlined the capacity of the Greenline Project to contribute to the UN SDGs (CoM and EY Citation2022). The SDGs are part of the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development, made up of 17 goals, 169 targets and 232 interrelated indicators. These global measures were adopted by all UN member states as a pathway to a sustainable future by 2030 (UN Citation2015). Despite considerable efforts, it is evident that the SDGs will not now be achieved holistically and in all places by 2030.

The City of Melbourne incorporated the SDGs into the Council Plan 2021–25. In 2022 the Melbourne City Council adopted the implementation of a Voluntary Local Review (VLR) of the SDGs, the first city in Australia to do so (CoM Citation2022b). VLRs assist administrators to streamline the process of localising SDGs, relevant, in this instance to the City of Melbourne. Localisation of the SDGs facilitates tailored measures and bespoke targets which recognise national, regional and city-level contexts. Monitoring performance can be enhanced by using digital and data innovations applied openly and transparently (Narang Suri, Miraglia, and Ferrannini Citation2021). At the precinct level, the SDGs, when localised, present a framework from which relevant targets can be selected for application to urban regeneration programs, such as the Greenline Project to measure sustainability performance. Delivery of the project is forecast to contribute directly to ten localised targets for seven of the SDGs, these are summarised in in the context of five overarching objectives for the Greenline Project.

Figure 5. Localised SDG Targets in the Context of Greenline Project Objectives (Adapted from CoM Citation2022a and CoM Citation2022b).

Greenline Project objectives

Framing performance measures from the high-level project objectives included in the Greenline Implementation Plan is the starting point for the selection of performance attributes. Four key project objectives address (1) Environment, (2) Culture, (3) Place, and (4) Connection (CoM Citation2021a), in addition to activities that relate to (5) Economy which seeks to attract additional investment to the corridor. Project themes/objectives contained in the Greenline Implementation Plan 2021 were developed by the City of Melbourne with stakeholders as part of a comprehensive ongoing public and stakeholder engagement process throughout 2021. They are organised as environmental, social, and economic parameters designed to promote urban sustainability and achievement of the SDGs building upon and incorporating a range of major and strategic planning policies of the Melbourne City Council and State Government of Victoria, in particular the Yarra River – Birrarung Strategy (CoM Citation2019) and Yarra Strategic Plan (Burndap Birrarung burndap umarkoo) 2022–2032 (Melbourne Water Citation2022).

Presented as a summary statement in the Greenline Implementation Plan 2021 each of the four themes/objectives is described as follows.

‘Environment: Healthy ecosystems – The river will be enhanced as an ecological corridor. Increased planting and revitalisation of the riparian edge will improve biodiversity and river health and increase resilience. Water quality and flood management will be addressed to help mitigate the effects of climate change.’

‘Culture: Authentic stories and experiences – Melbourne’s heritage will be made more tangible by creatively embedding stories into the landscape. Spaces that inspire and educate will celebrate Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and broader Aboriginal significance along the Birrarung, and our immigration and maritime past.’

‘Place: Great Places for People – Open spaces along the river will be reimagined through bold interventions, strengthening their identities and respecting existing values. These spaces will provide opportunities for public activities and places of respite. They will build connections with nearby areas to encourage new economic opportunities. The Greenline will provide for and welcome everyone, ensuring diverse and safe places and experiences.’

‘Connection: An uninterrupted journey – Access along the river and to the Greenline public spaces will be improved, as will connections between the river and city. Physical barriers will be reduced, modal conflicts will be minimised, and wayfinding will be enhanced. Safety and inclusivity will be prioritised. Compelling journeys will be created through varying landscape experiences and will enable opportunities to connect with the water’. (CoM Citation2021a, 6 and 7)

The fifth objective relates to economy and seeks to ‘Encourage inclusive economic activation along the Greenline’, (CoM Citation2021a). This aim was later expanded and referenced in the Greenline Business Case of 2022 which estimated total economic benefits of $1.2 billion over 20 years to 2042. This includes forecast increases of $740 million in economic activity (adjoining retail spending, uplift in property values, etc.), $250 million of social value (improved community health and wellbeing, connection to Country, social capital, etc.) and $60 million of environmental value (ecosystem, biodiversity and environmental restoration, etc.) (CoM and EY Citation2022).

Systematic processes are required to mitigate risks associated with identifying both the data available and the data required together with aspects of usability and reporting via dashboards or other visual means. There are considerable challenges ensuring dashboards are maintained with accurate and up to date information these operability challenges were experienced in Dublin, Ireland at the City University campus, and other districts (Calzati Citation2023). For the Greenline Project data will be captured by on-site monitors and sensors installed along the Greenline enabling a better understanding of land use patterns within the physical environment. The analysis of this information will support data led decision-making, for example in terms of relevant themes/objectives: (1) Environment – monitoring micro-climate and relating to human comfort, (2) Culture – connecting First Nations stories geospatially to place (utilising cultural programs including the Aboriginal Mapping project), (3) and (4) Place improvements on – using pedestrian monitors and sensors to map movement patterns for improved safety and mobility for pedestrian and active transport users, and (5) Analyse retail spending and other financial metrics and communicate this information to local businesses. Overall, data will be applied to inform design actions and interrelationships with open space and public realm improvements.

The preliminary conceptual framework shown in summarises the specific high-level performance objectives and localised SDGs selected for the completed Greenline Project and illustrates key interrelationships and the potential contribution UDT technologies can make to project design and assessment. The relationships between these metrics and UDT applications require further research to test if the selected attributes provide a sufficiently comprehensive assessment of functionality and sustainable project performance and can be supported by relevant data sources and timely data analytics for practical application to the Greenline and other people-centric urban regeneration projects.

Conclusion and future outlook

This paper explored the challenges and opportunities in implementing Digital Twin technology in Melbourne’s Greenline Project, in its context, based on a performance-based framework focused on the SDGs, as well as city-wide and project-specific sustainability objectives. This framework has wider potential applications and benefits in enhancing the design process, performance monitoring, communication and management of urban revitalisation and regeneration projects, despite the challenges posed by the complex and ever-evolving urban ecosystems.

The key challenges include collecting and/or accessing the appropriate type and amount of data or information needed to develop and apply the UDTs for specific purposes. Another is the knowledge, effort and technology needed to mirror the interaction between physical and virtual urban environments in or near real time, or even the relatively easier task to regularly update the critically needed attributes of a UDT. Urban planners and key stakeholders should be enabled and supported to identify performance objectives and outcomes in urban revitalisation and regeneration projects, and thus, spearhead the development of practical applications, leveraging expertise across disciplines. The challenge of upskilling the planning profession with state-of-the-art Digital Twin, geospatial and 3D visualisation technologies is a hot topic. Academic institutions, services firms and professional associations including, the Planning Institute of Australia, are hosting seminars, shorts courses, micro-credentials and professional development programs to equip planners with new skills to build capacity and lead project outputs. This approach will drive the integration of data collection and management, analytics, understanding the interplay between built environments and social systems, and fostering collaborative efforts among urban professionals, data scientists, policymakers and technology providers.

International examples of Digital Twins in urban and transport planning demonstrate their utility in fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, design, operational management, and placemaking. Focusing on the City of Melbourne’s Greenline Project, in particular, helped us better understand the elements and relationships that need to be considered in a performance-based framework that addresses the SDGs and project-specific objectives. The framework presented herein needs to be tested and its utility and value demonstrated next. Urban regeneration projects do not systematically apply the SDGs or other explicit performance objectives or functional criteria potentially missing opportunities to systematically utilise information and data in the evaluation of public space design options or to innovate in ways that contribute to project aspirations.

The specific implementation role of UDTs in real-world cases such as the Greenline Project is essential. Lessons on integration with assessment and design, associated tools and collection and use of information and data to support a performance-based approach in the delivery and management of urban public places in people-centric urban regeneration projects need to be synthesised and used to refine the UDT application framework. This will be further helped by a better understanding of how different urban stakeholders view the barriers and constraints to effectively use UDTs in major or complex urban regeneration projects.

Further research into how effectively physical and virtual systems interconnect in real-life applications is also crucial. This should include a wide range of technologies, including Digital Twins, VR, AR, AI, and 3D visualisation, that can significantly enhance communication, community involvement, and participatory planning, leading to more sustainable and resilient urban spaces.

Successfully addressing the above challenges will not only benefit Melbourne’s Greenline Project but can also be adapted for diverse urban regeneration initiatives worldwide.

Disclosure statement

Mark Allan is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne and an employee of the City of Melbourne an organisation that may be affected by research reported in this paper.

References

- Allan, M., A. Rajabifard, G. Foliente, and S. Sabri. 2021. “SDG 11 as a ‘Glocal’ Framework - The Challenges of Implementing Global and National Goals at a City Level.” GIM International 35 (6): 45–48.https://www.gim-international.com/content/article/sdg-11-as-a-glocal-framework.

- ANZLIC. 2019. “Principles for Spatially Enabled Digital Twins of the Built and Natural Environment in Australia.” (p. 25). https://www.anzlic.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/principles.

- Batty, Michael. 2018. “Digital Twins.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 45 (5): 817–820.

- Standards Australia, Beck, A., and G. Cotterill. 2023. Digital Twin White Paper. Standards Australia. https://www.standards.org.au/getmedia/c81ae488-b13d-4921-8961-2cf61cb8e94a/Digital_Twin-Report.pdf.aspx.

- Bohnsack, R., C. M. Bidmon, and J. Pinkse. 2022. “Sustainability in the Digital Age: Intended and Unintended Consequences of Digital Technologies for Sustainable Development.” Business Strategy and the Environment 31 (2): 599–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2938.

- Burinskienė, A., and M. Seržantė. 2022. “Digitalisation as the Indicator of the Evidence of Sustainability in the European Union.” Sustainability 2022: 1–20.https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/14/8371.

- Calzati, Stefano. 2023. “No Longer Hype, Not yet Mainstream? Recalibrating City Digital Twins’ Expectations and Reality: A Case Study Perspective.” Frontiers in Big Data 6: 1–12https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2023.1236397.

- Cappa, F., S. Franco, and F. Rosso. 2021. “Citizens and Cities: Leveraging Citizen Science and Big Data for Sustainable Urban Development.” Business Strategy and the Environment 31 (2): 648–667. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2942.

- CoM (City of Melbourne). 2019. “Yarra River – Birrarung Strategy.” Participate Melbourne. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/city-river-strategy.

- CoM (City of Melbourne. 2021a. The Greenline Implementation Plan. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/greenline-implementation-plan.pdf.

- CoM (City of Melbourne). 2021b. “Economic Development Strategy 2031.” https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/economic-development-strategy-2031.pdf.

- CoM (City of Melbourne). 2022a. The Greenline Project Self-Guided Tour Brochure.

- CoM (City of Melbourne). 2022b. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals City of Melbourne Voluntary Local Review 2022. Melbourne, Australia.

- CoM (City of Melbourne). 2023a. Melbourne as a Smart City. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/about-melbourne/melbourne-profile/smart-city/pages/smart-city.aspx.

- CoM (City of Melbourne). 2023b. “Emerging Technology Testbed.” Participate Melbourne. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/emerging-tech-testbed.

- CoM (City of Melbourne), and EY. 2022. The Greenline Project Summary Business Case. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/news-and-media/Pages/Business-case-stacks-up-for-the-Greenline-Project–.aspx.

- Cureton, P., and N. Dunn. 2021. “Digital Twins of Cities and Evasive Futures.” In Shaping Smart for Better Cities, 267–282. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818636-7.00017-2.

- Du, Jiaxin, Xinyue Ye, Piotr Jankowski, Thomas W. Sanchez, and Gengchen Mai. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence Enabled Participatory Planning: A Review.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 0 (0): 1–28. 10.1080/12265934.2023.2262427.

- Ellery, P. J., J. Ellery, and M. Borkowsky. 2021. “Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking.” International Journal of Community Well-Being 4 (1): 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-020-00078-3.

- Farshid, Mana, Jeannette Paschen, Theresa Eriksson, and Jan Kietzmann. 2018. “Go Boldly!: Explore Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Mixed Reality (MR) for Business.” Business Horizons 61 (5): 657–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.05.009.

- Foliente, G. C., P. Huovila, D. Spekkink, G. Ang, and W. Bakens. 2005. Performance Based Building R&D Roadmap. EUR 21988. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: CIBdf — International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction-Development Foundation. http://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3148.8643.

- Ha, L. T. 2022. “Effects of Digitalization on Financialization: Empirical Evidence from European Countries.” Technology in Society 68:101851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101851.

- Houghton, K., E. Miller, and M. Foth. 2014. “Integrating ICT Into the Planning Process: Impacts, Opportunities and Challenges.” Australian Planner 51 (1): 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2013.770771.

- Judge, S., and L. Harrie. 2020. “Visualizing a Possible Future: Map Guidelines for a 3D Detailed Development Plan.” Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis 4 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41651-020-00049-4.

- Lehtola, V. V., M. Koeva, S. O. Elberink, P. Raposo, J.-P. Virtanen, F. Vahdatikhaki, and S. Borsci. 2022. “Can Digital Twin Techniques Serve City Needs? – GIM International from Digital Twin of a City: Review of Technology Serving City Needs.” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 114:102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2022.102915.

- Lu, Q., A. Kumar Parlikad, G. D. Ranasinghe, X. Xie, Z. Liang, E. Konstantinou, J. Heaton, and J. Schooling. 2020. “Developing a Digital Twin at Building and City Levels: Case Study of West Cambridge Campus.” Journal of Management in Engineering 36 (3): 1–19 https://ascelibrary.org/action/cookieAbsent.

- Melbourne Water. 2022. Burndap Birrarunbg Burndap UMarkoo Yarra Strategic Plan A 10-Year Plan for the Yarra River Corridor 2022-2032 Yarra Strategic Plan. Burndap Birrarung burndap umarkoo. Melbourne Water, Victoria, Australia.

- Najafi, P., M. Mohammadi, P. van Wesemael, and P. M. Le Blanc. 2023. “A User-Centred Virtual City Information Model for Inclusive Community Design: State-of-Art.” Cities 134:104203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104203.

- Narang Suri, S., M. Miraglia, and A. Ferrannini. 2021. “Voluntary Local Reviews as Drivers for SDG Localisation and Sustainable Human Development.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 22 (4): 725–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2021.1986689.

- Pietzsch, Holger. 2022. “Can Digital Construction Save the Planet?” Havard Data Science Review (HDSR) 1–3.

- Roberts, P., H. Sykes, and R. Granger, eds. 2016. Urban Regeneration. 2nd ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Sabri, S., and P. Witte. 2023. “Digital Technologies in Urban Planning and Urban Management.” Journal of Urban Management 12 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2023.02.003.

- Sanchez, T. W., H. Shumway, T. Gordner, and T. Lim. 2023. “The Prospects of Artificial Intelligence in Urban Planning.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 27 (2): 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2022.2102538.

- Shahat, E., C. T. Hyun, and C. Yeom. 2021. “City Digital Twin Potentials: A Review and Research Agenda.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063386.

- TCL (Taylor Cullity and Lethlean). 2022. The Greenline Project. https://www.tcl.net.au/news/the-greenline-project.

- Tomko, Martin, and Stephan Winter. 2019. “Beyond Digital Twins – A Commentary.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 46 (2): 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808318816992.

- Tzachor, A., S. Sabri, C. E. Richards, A. Rajabifard, and M. Acuto. 2022. “Potential and Limitations of Digital Twins to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 5 (10): 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00923-7.

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs (un.org).

- van der Aalst, W. M. P., O. Hinz, and C. Weinhardt. 2021. “Resilient Digital Twins.” Business & Information Systems Engineering 63 (6): 615–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-021-00721-z.

- VanDerHorn, E., and S. Mahadevan. 2021. “Digital Twin: Generalization, Characterization and Implementation.” Decision Support Sytems 145:113524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2021.113524.

- van der Valk, H., H. Haße, F. Möller, and B. Otto. 2021. “Archetypes of Digital Twins.” Business & Information Systems Engineering 64 (3): 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-021-00727-7.

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2022. Digital Twin Cities: Framework and Global Practices. April 20. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/publications/digital-twin-cities-framework-and-global-practices/.

- Ye, X., J. Du, Y. Han, G. Newman, D. Retchless, L. Zou, Y. Ham, and Z. Cai. 2023. “Developing Human-Centered Urban Digital Twins for Community Infrastructure Resilience: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Planning Literature 38 (2): 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122221137861.