Abstract

Regular physical activity provides physical, mental and cognitive benefits for children. However, globally, only 20% of children meet the recommended levels of physical activity and, on average, students sit for three-quarters of the school day. Active breaks are a well-tested component of many school-based physical activity interventions, but there are many barriers to the sustainable implementation of active breaks by teachers in schools. To overcome these barriers, the narrow, traditional idea of the ‘brain break’ needs to be reconceptualized, where active breaks are viewed as being separate from learning and teaching, and where physical activity is perceived as an interruption to learning. This article presents the TransformUs Active Break (TAB) model, which positions active breaks as part of an overall approach to proactive classroom management and as a key contributor to effective teaching. The TAB model comprises five types of active breaks, each serving a specific educative function-structure, transition, manage, energize and learn. The model demonstrates how active breaks can be integrated meaningfully into lessons to enhance teaching and learning as an effective approach for sustained school-based physical activity.

It is well established that physical activity plays an important role in the metabolic, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal health of children (ages 5–12) and adolescents (ages 13–17; Carson et al., Citation2016; Janssen & LeBlanc, Citation2010; Poitras et al., Citation2016). In addition, physical activity has a positive effect on the mental health of children and adolescents by reducing levels of anxiety and depression; increasing resilience, self-esteem, and self-confidence; and improving mood and well-being (Andermo et al., Citation2020; S. J. H. Biddle et al., Citation2019). What is less widely known is the role that physical activity plays in learning. Physical activity has been positively associated with increased academic-related outcomes, including cognitive skills (e.g., executive functioning, attention, memory, comprehension), attitudes toward learning (e.g., motivation, self-concept, satisfaction, enjoyment), engagement in learning (e.g., on-task time), and academic achievement (e.g., standardized test scores; Mahar et al., Citation2006; Schmidt et al., Citation2016; Singh et al., Citation2019).

Sedentary behavior is also an important consideration in the health and well-being of children and adolescents. Sedentary behavior is defined as sitting, reclining, or lying down while awake and expending less than 1.5 metabolic equivalent units (Tremblay et al., Citation2017). There is emerging evidence of the negative health effects and impacts on academic outcomes of high levels of sedentary behavior (Carson et al., Citation2016; Tremblay et al., Citation2011). Considering this evidence, there have been global calls for greater policy emphasis on promoting regular physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in young people (Bull et al., Citation2020).

Despite the known benefits, young people globally are far less active than expected, with 81% of school-age children not meeting the recommendations of 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Further, excessive sedentary time is widespread among children and adolescents around the world (Pate et al., Citation2011), with only 35% of children and 20% of adolescents meeting sedentary screen-based behavior guidelines (Australian Institute of Health Welfare, Citation2018; Guthold et al., Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2022). This has been further exacerbated by COVID-19-related restrictions, during which young people were less active and more sedentary (Arundell et al., Citation2022; Rossi et al., Citation2021).

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and related policy responses, there have also been broad, long‐lasting implications for children’s and adolescents’ learning, including diminished engagement in learning and poorer academic outcomes (N. Biddle et al., Citation2020; Goldfeld et al., Citation2022). This is in addition to the long-term decline in reading, mathematics, and science presented by the latest Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment results (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2019). Considering that the current educational norm is for students to sit for approximately 75% of the school day (Arundell et al., Citation2019; Contardo Ayala et al., Citation2018), the school setting offers an ideal opportunity to enhance young people’s physical activity, reduce sedentary behavior, and simultaneously improve their learning and well-being outcomes (van Sluijs et al., Citation2021).

TransformUs: A Whole-of-School Education and Health Initiative

Whole-of-school physical activity and sedentary behavior interventions provide practical, low-cost, and effective strategies to improve learning and well-being outcomes (Watson et al., Citation2017). One example is TransformUs, a unique and efficacious education and health initiative designed for teachers, schools, and parents (https://transformus.com.au; Salmon et al., Citation2011, Citation2023; Yildirim et al., Citation2014). The change principles underpinning TransformUs include social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986; Rachlin, Citation1989), behavioral choice theory (Rachlin, Citation1989), and ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1986). The program uses innovative behavioral, pedagogical, and environmental strategies within the classroom (e.g., active breaks, active lessons, active equipment, and classroom layout), across school (e.g., recess and lunch, supportive playground environments), and at home (e.g., active homework, newsletters to parents) to support schoolchildren in being more active and more engaged in their learning, improve their educational outcomes, and benefit their health and well-being (Salmon et al., Citation2011).

One well-tested component of TransformUs, as with many other whole-of-school physical activity interventions, is active breaks (Carson et al., Citation2013; Salmon et al., Citation2020; Yildirim et al., Citation2014). Active breaks have been defined in the literature as short bouts of physical activity performed as a break from academic instruction (Peiris et al., Citation2022). They are also sometimes referred to as “brain breaks” (Glapa et al., Citation2018). Active breaks have previously been categorized as non-curriculum linked, curriculum linked and cognitively challenging (Salmon et al., Citation2020). Systematic review evidence suggests that active breaks can reduce sitting time; increase physical activity; improve cognitive function, mood, on-task behavior, and perceived competence; and strengthen teacher–student relationships (Masini et al., Citation2020).

Although active breaks are often effective in the short term, there are many barriers to their adoption, implementation, fidelity, and sustainability when delivered by teachers in schools (Lai et al., Citation2014; Naylor et al., Citation2015). Common barriers to implementation of active breaks include lack of time, a crowded curriculum, lack of teacher confidence, lack of resources, limited student participation, and space constraints in classrooms (Jaimie McMullen et al., Citation2014; N. Nathan et al., Citation2018; Watson et al., Citation2019). Teachers have also reported a reluctance to deliver active breaks due to the perception that they interrupt and disrupt academic learning. Some teachers are concerned that active breaks compete with learning and curriculum time, increase off-task student behavior, and create subsequent challenges to resettle or refocus the class (Mazzoli et al., Citation2019; Watson et al., Citation2019). Perhaps one of the greatest barriers to teachers successfully embedding active breaks into routine teaching practice is the competing demands on their time and focus (McMullen et al., Citation2014; Metcalf et al., Citation2012; Watson et al., Citation2019). When active breaks are seen as being separate or isolated from learning and teaching, where the physical activity is perceived as interrupting learning and where students stand to be active and sit to learn, the aforementioned barriers may indeed hold true.

To overcome these perceived barriers, we need to reconceptualize the narrow, traditional focus of the brain break in a more purposeful, integrated and educative approach. We need to position active breaks as a teaching tool, part of an instructional model, a vehicle for increased student engagement, a proactive classroom management strategy, and a mechanism to create a positive classroom environment. The purpose of this article is to describe the TransformUs Active Break (TAB) model, which positions active breaks in an integrated approach to proactive classroom management for primary and secondary schools, which also contributes to effective teaching.

TransformUs Active Break Model

The TAB model positions active breaks within an overall approach to proactive classroom management and as a key contributor to effective teaching. Proactive classroom management is the practice of managing student behavior with positive strategies that prevent disruptive behaviors before they occur (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, Citation2020). If students are engaged in learning activities and feel connected, they are less likely to move off task and teaching will be more effective (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, Citation2020). Effective teaching is the single greatest determinant of student improvement (Department of Education–Victoria State Government, Citation2021). Teachers have a direct impact on student achievement and on student engagement and motivation for learning (Department of Education–Victoria State Government, Citation2021).

What teachers do in the classroom and how they interact with students is vital. Teachers maximize student learning when they create a classroom environment that is supportive, positive, and characterized by a clear focus on learning. Teachers have the greatest potential to positively impact student learning, and the strategies they use matter (Hanushek et al., Citation2005; Hattie, Citation2004). Hattie’s meta-analysis relating to student achievement identified the intentional alignment of learning and teaching strategies as a key finding to maximize impact on student learning (Hattie, Citation2009, Citation2023). As such, there is a need to go beyond brain breaks and see active breaks for their integrative, educative purpose, where they can be used as a strategy to complement and facilitate excellence in teaching and contribute to many evidence-based instructional models to improve student outcomes. By planning active breaks that are meaningfully integrated, teachers can mitigate off-task behavior, increase student engagement, and enhance student learning outcomes. The TAB model has the potential to add to the teacher’s repertoire of teaching strategies and maximize their effectiveness — thus having an impact on student learning.

Five Functions of Active Breaks in the TAB Model

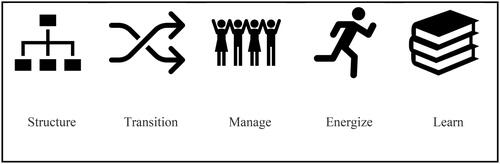

The TAB model comprises five types of active breaks, with each serving a specific function: structure, transition, manage, energize, and learn (; ). The model demonstrates how the active breaks can be meaningfully integrated into lessons to enhance teaching and learning.

Table 1. Overview of the TAB Model Components, Purpose, and Examples

Structure

The purpose of structured active breaks is to use movement as part of the structure of lessons. Effective educators plan and deliver structured lessons that incorporate a series of clear steps and transitions and scaffold learning to build learners’ knowledge and skills (Department of Education–NSW, Citation2022). How teachers structure lessons can have a significant impact on student learning. Research has shown that student achievement is maximized when teachers structure lessons purposefully, efficiently, and effectively (Kyriakides et al., Citation2013). Structured active breaks serve an instructional purpose, allowing students to move without disrupting the flow of the lesson or planned practice.

Structured active breaks can incorporate signs such as “yes/no,” “true/false,” “agree/disagree” on the walls of the classroom; “A/B/C/D” in the corners; or tape or line markings on the floor representing a scale or continuum. Instead of planning a traditionally seated question-and-answer session, teachers ask the students to respond to questions by physically moving to the relevant sign or location. Teachers can build on this by asking students to justify their response or build an argument for or against a statement using evidence or content covered in previous lessons.

Additionally, structured active breaks provide alternative means of questioning, which enables teachers to check for understanding, motivate students, lead students to think, and help develop problem-solving skills (Buchanan Hill, Citation2016). The most effective questions are high-order “why?,” “how?,” and “which is best?” questions that really make students think. These require processing time and may be more effective in pairs or groups than alone (Buchanan Hill, Citation2016). The structured active breaks promote collaborative learning opportunities (i.e., students physically moving into groups according to their responses; e.g., yes/no, A/B/C/D, strongly agree/strongly disagree). Here, peer questioning and group discussion can be incorporated within cooperating groups to stimulate the cognitive and metacognitive processing appropriate to the learning task, allowing deeper level processing. Deliberately planning structured active breaks in lessons can enable teachers to focus on long- to medium-term student learning goals (Department of Education–NSW, Citation2022).

Transition

The purpose of transitional active breaks is to allow intentional, structured, and task-orientated movement as students transition between learning tasks or lesson phases. In the TAB model, these transitions provide opportunities for purposeful movement. For example, the gradual release of responsibility model of instruction (Pearson & Gallagher, Citation1983) progresses from a worked example delivered by the teacher, to group work, to independent learning (Pearson & Gallagher, Citation1983). This model provides a structure for teachers to move from assuming all of the responsibility for performing a task to a situation in which the students assume all of the responsibility. The gradual release of responsibility model also includes defined transitions from one phase to the next, which provides a structure for the meaningful integration of transitional active breaks. For example, rather than students remaining sedentary when transitioning from teacher-directed to group work (e.g., working with the groups they are already seated with), teachers can ask students to stand and move into groups appropriate to the purpose of the lesson. By providing opportunities to physically move into groups, transitional active breaks also facilitate collaboration through movement, and research has consistently found that collaborative approaches positively impact student learning (Evidence for Learning, Citation2019).

In addition, transitional active breaks can be utilized in assessment. Research demonstrates that quality assessment has a greater positive impact on student learning than any other intervention, and all students benefit from quality assessment practices (Davies et al., Citation2012; Wiliam, Citation2011). Transitional active breaks can be used for diagnostic assessment before commencing a new unit of work (Australian Capital Territory Government, Citation2016). For example, in a “standing pair share” students discuss what they know. Using these techniques, teachers can develop a clear understanding of student understanding, identify gaps in knowledge, set learning goals, and gauge the level of support needed for all students to succeed. Further, teachers can use transitional active breaks in formative assessment (Australian Education Research Organisation, Citation2023); for example, to indicate whether they need to spend more time on the current content or can move on to the next topic. Research has shown that formative assessment can have a significant impact on student learning when used consistently and systematically. A recent meta-analysis of 138 factors found that formative assessment and feedback are in the top 10 strategies to enhance student learning outcomes (The Council of Chief State School Officers, Citation2018). By including active breaks in lesson transitions and as part of quality assessment practices, active breaks can become a normalized, integrated, and purposeful component of teaching and learning.

Manage

The purpose of management active breaks is to proactively and preventatively manage the class. Off-task behavior often results from a decline in focus, interest, and concentration (Godwin et al., Citation2016), which is commonly associated with prolonged periods of seated learning (Brusseau & Burns, Citation2018). Effective classroom management increases on-task learning behaviors (Chaffee et al., Citation2017; Marzano et al., Citation2003) and reduces disruptive behaviors (Chaffee et al., Citation2017; Korpershoek et al., Citation2016; Oliver et al., Citation2011). Active breaks can be used as a preventative classroom management strategy.

Preventative classroom management strategies create a positive environment that supports students to engage in learning and develop prosocial behaviors, and can also increase the amount of time for instruction, minimize disruptions, and reduce the amount of time teachers spend on responding to inappropriate behaviors (Osher et al., Citation2010; Skiba et al., Citation2016; Sugai & Horner, Citation2008). For example, for every 20 to 30 minutes of prolonged sitting, teachers are encouraged to incorporate a short active break. These short management active breaks can be linked to the curriculum and directly contribute to the learning or can be used simply as a break from sitting and to reengage students via activity. As such, regular proactive use of active breaks can create a positive learning environment by mitigating the need to implement reactive, negative disciplinary approaches for classroom management.

Further, research has shown that children who have active breaks develop better emotional regulation and impulse control than children who do not have active breaks (Mazzoli et al., Citation2021). Moreover, physical activity improves overall well-being, and overall well-being has been shown to enhance intrinsic motivation and decrease disciplinary problems (Bücker et al., Citation2018).

Energize

The purpose of energizing active breaks is to break up long periods of sedentary class time with short bouts of physical activity. Some of the benefits of physical activity on children’s health occur immediately after a short bout of activity, such as reduced anxiety and improved cognitive function (Hillman et al., Citation2019; Verburgh et al., Citation2014). These effects allow students to become reenergized, refocused, and reengaged in their learning. The energizing active break does not have to be curriculum linked but rather serves to break up prolonged sitting through the provision of physical movement.

The TAB model encourages teachers to align the intensity of activity with the purpose and phase of a lesson. For example, teachers can implement high-intensity active breaks (e.g., dance breaks) on completion of a seated learning task to allow students to reinvigorate themselves before the next period of seated learning and simultaneously reap the physiological benefits of higher intensity physical activity. Conversely, teachers can implement lower intensity or calmer active breaks (e.g., stand and stretch with focused breath work) to resettle the class. By allowing students to choose or contribute to the selection of active breaks, teachers can build student agency (Vaughn, Citation2020) and convey the importance of movement for behavior regulation, focus, and productivity.

Learn

The purpose of learning active breaks is to introduce, reinforce, consolidate, or demonstrate learning in a visual and physically active way. This type of active break creates opportunities for students to “embody” their learning. An embodied perspective proposes that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body’s interactions with the world (Wilson, Citation2002). Embodied activities engage students in physical actions to help them better understand concepts (M. J. Nathan & Walkington, Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2014). For example, when teaching time or angles, students can be asked to stand and demonstrate a particular time or angle using their body and/or arms. These types of activities have great potential to help students develop deeper conceptual understanding, engage in the learning process, and retain knowledge (M. J. Nathan & Walkington, Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2014; Citation2016).

Learning active breaks also provide an opportunity for multiple exposures of content. Research demonstrates that deep learning of new knowledge develops over time via multiple, spaced interactions with the content (Kang, Citation2016). The use of physical and visual representations via learning active breaks provides an additional mechanism to convey content to build and reinforce student learning.

Learning active breaks can also facilitate differentiated teaching. Students come to learning with different levels of readiness, interest, and knowledge. Further, learning does not occur at a predetermined pace. Teaching can be differentiated by modifying the content, process, product, and/or environment (Subban, Citation2006). Providing opportunities for students to learn through doing can help them understand a concept in a visual and physical way. In addition, learning through doing can enable students to progress to different levels of thinking (e.g., Bloom’s taxonomy; Bloom & Engelhart, Citation1956; Shane, Citation1981) and apply their knowledge using physical representations.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to describe the TAB model, which positions active breaks in an integrated approach to proactive classroom management in primary and secondary schools and also contributes to effective teaching. Active breaks in the classroom have been shown to effectively increase physical activity in children and improve classroom behavior. However, there are numerous barriers to the sustained use of active breaks by teachers. To address these barriers, we consider the educational benefits of active breaks to complement and facilitate instructional models and improve student outcomes.

In the TAB model, five types of active breaks — structured, transitional, management, energizing, and learning — are positioned within an overall approach to proactive classroom management as a key contributor to effective teaching. Active breaks need to be considered in the planning stage to ensure that they are viewed as an integrated component of lessons instead of isolated add-ons. Future research will explore how the other classroom-based components of TransformUs, such as active academic lessons and active environments, interact with active breaks as well as whether certain types of active breaks are adopted and implemented more readily by teachers than others and whether the five TAB types have similar impacts on the learning and health outcomes of children and adolescents.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natalie J. Lander

Natalie J. Lander ([email protected]) is an associate professor and Ana Maria Contardo Ayala is a research fellow at the Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences at Deakin University in Geelong, Australia. Emiliano Mazzoli is a research fellow in the School of Health and Social Development at Deakin University in Geelong, Australia. Samuel K. Lai is a project manager, Jess Orr is a research fellow, and Jo Salmon is a professor at the Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences in Deakin University, Geelong, Australia.

References

- Andermo, S., Hallgren, M., Nguyen, T. T., Jonsson, S., Petersen, S., Friberg, M., Romqvist, A., Stubbs, B., & Elinder, L. S. (2020). School-related physical activity interventions and mental health among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 6(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-020-00254-x

- Arundell, L., Salmon, J., Koorts, H., Contardo Ayala, A. M., & Timperio, A. (2019). Exploring when and how adolescents sit: Cross-sectional analysis of activPAL-measured patterns of daily sitting time, bouts and breaks. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 653. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6960-5

- Arundell, L., Salmon, J., Timperio, A., Sahlqvist, S., Uddin, R., Veitch, J., Ridgers, N. D., Brown, H., & Parker, K. (2022). Physical activity and active recreation before and during COVID-19: The Our Life at Home study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25(3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2021.10.004

- Australian Capital Territory Government. (2016). Teachers’ guide to assessment. https://www.education.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/297182/Teachers-Guide-To-Assessment.pdf.

- Australian Education Research Organisation. (2023). Formative assessment. https://www.edresearch.edu.au/practice-hub/formative-assessment.

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. (2018). Physical activity across the life stages. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/physical-activity/physical-activity-across-the-life-stages.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory [Bibliographies]. Prentice-Hall. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b1324426&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Biddle, N., Edwards, B., Gray, M., & Sollis, K. (2020). Experience and views on education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Centre for Social Research and Methods (ANU). https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2020/12/Experience_and_views_on_education_during_the_COVID-19_pandemic.pdf.

- Biddle, S. J. H., Ciaccioni, S., Thomas, G., & Vergeer, I. (2019). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.011

- Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals [1st ed]. Longmans. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b2872852&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human-development – Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

- Brusseau, T. A., & Burns, R. D. (2018). Physical activity, health-related fitness, and classroom behavior in children: A discriminant function analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 89(4), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2018.1519521

- Buchanan Hill, J. (2016). Questioning techniques: A study of instructional practice. Peabody Journal of Education, 91(5), 660–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1227190

- Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

- Carson, V., Hunter, S., Kuzik, N., Gray, C. E., Poitras, V. J., Chaput, J. P., Saunders, T. J., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Okely, A. D., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., Lee, H., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: An update. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6 (Suppl. 3), S240–S265. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0630

- Carson, V., Salmon, J., Arundell, L., Ridgers, N. D., Cerin, E., Brown, H., Hesketh, K. D., Ball, K., Chinapaw, M., Yildirim, M., Daly, R. M., Dunstan, D. W., & Crawford, D. (2013). Examination of mid-intervention mediating effects on objectively assessed sedentary time among children in the Transform-Us! Cluster-randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-62

- Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2020). Classroom management – creating and maintaining positive learning environments, NSW Department of Education. https://education.nsw.gov.au/about-us/educational-data/cese.

- Chaffee, R. K., Briesch, A. M., Johnson, A. H., & Volpe, R. J. (2017). A meta-analysis of class-wide interventions for supporting student behavior. School Psychology Review, 46(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0015.V46-2

- Contardo Ayala, A., Salmon, J., Dunstan, D., Arundell, L., Parker, K., & Timperio, A. (2018). Longitudinal changes in sitting patterns, physical activity, and health outcomes in adolescents. Children, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6010002

- Davies, A., Herbst, S., & Reynolds, B. P. (2012). Leading the way to assessment for learning: A practical guide (2nd Ed.). Solution Tree and Connections Publishing.

- Department of Education–NSW. (2022). Planning a lesson. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/teacher-quality-and-accreditation/strong-start-great-teachers/refining-practice/planning-a-lesson.

- Department of Education–Victoria State Government. (2021). Priority: Excellence in teaching and learning. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/management/improvement/Pages/priority1excellenceteaching.aspx.

- Evidence for Learning. (2019). Evidence for Learning - The toolkits. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/education-evidence.

- Glapa, A., Grzesiak, J., Laudanska-Krzeminska, I., Chin, M. K., Edginton, C. R., Mok, M. M. C., & Bronikowski, M. (2018). The impact of brain breaks classroom-based physical activities on attitudes toward physical activity in polish school children in third to fifth grade. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020368

- Godwin, K. E., Almeda, M. V., Seltman, H., Kai, S., Skerbetz, M. D., Baker, R. S., & Fisher, A. V. (2016). Off-task behavior in elementary school children. Learning and Instruction, 44, 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.04.003

- Goldfeld, S., O'Connor, E., Sung, V., Roberts, G., Wake, M., West, S., & Hiscock, H. (2022). Potential indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children: A narrative review using a community child health lens. Medical Journal of Australia, 216(7), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51368

- Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2

- Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J., O'Brien, D., Rivkin, S. G. (2005). The market for teacher quality. (Working Paper 11154). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w11154.

- Hattie, J. (2004). It’s official: Teachers make a difference. Educare News(144). https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsaup&AN=edsaup.132958&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement [Bibliographies]. Routledge. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b3539585&site=eds-live&scope=site. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=http://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203887332. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=367685

- Hattie, J. (2023). Visible .earning. A synthesis of over 2,100 meta-analyses relating to achievement [Online]. Taylor & Francis Group. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b5235270&site=eds-live&scope=site. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=7192138

- Hillman, C. H., Logan, N. E., & Shigeta, T. T. (2019). A review of acute physical activity effects on brain and cognition in children. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 2019(17), 4. https://journals.lww.com/acsm-tj/fulltext/2019/09010/a_review_of_acute_physical_activity_effects_on.3.aspx

- Janssen, I., & LeBlanc, A. G. (2010). Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-40

- Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

- Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., & Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 643–680. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626799

- Kyriakides, L., Christoforou, C., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2013). What matters for student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis of studies exploring factors of effective teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.010

- Lai, S. K., Costigan, S. A., Morgan, P. J., Lubans, D. R., Stodden, D. F., Salmon, J., & Barnett, L. M. (2014). Do school-based interventions focusing on physical activity, fitness, or fundamental movement skill competency produce a sustained impact in these outcomes in children and adolescents? A systematic review of follow-up studies. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0099-9

- Mahar, M. T., Murphy, S. K., Rowe, D. A., Golden, J., Shields, A. T., & Raedeke, T. D. (2006). Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 38(12), 2086–2094. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000235359.16685.a3

- Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., Pickering, D. (2003). Classroom management that works: research-based strategies for every teacher [Bibliographies]. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b2437052&site=eds-live&scope=site. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&AN=99261. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=3002081.

- Masini, A., Marini, S., Gori, D., Leoni, E., Rochira, A., & Dallolio, L. (2020). Evaluation of school-based interventions of active breaks in primary schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(4), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.008

- Mazzoli, E., Koorts, H., Salmon, J., Pesce, C., May, T., Teo, W. P., & Barnett, L. M. (2019). Feasibility of breaking up sitting time in mainstream and special schools with a cognitively challenging motor task. Journal of Sport and Health Science., 8(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2019.01.002

- Mazzoli, E., Salmon, J., Teo, W. P., Pesce, C., He, J., Ben-Soussan, T. D., & Barnett, L. M. (2021). Breaking up classroom sitting time with cognitively engaging physical activity: Behavioural and brain responses. PLoS One, 16(7), e0253733. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253733

- McMullen, J., Kulinna, P., & Cothran, D. (2014). Chapter 5 physical activity opportunities during the school day: Classroom teachers’ perceptions of using activity breaks in the classroom. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 33(4), 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0062

- Metcalf, B., Henley, W., & Wilkin, T. (2012). Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). BMJ, 345, Article e5888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5888

- Nathan, M. J., & Walkington, C. (2017). Grounded and embodied mathematical cognition: Promoting mathematical insight and proof using action and language. Cognitive Research, 2(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0040-5

- Nathan, N., Elton, B., Babic, M., McCarthy, N., Sutherland, R., Presseau, J., Seward, K., Hodder, R., Booth, D., Yoong, S. L., & Wolfenden, L. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 107, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.012

- Naylor, P. J., Nettlefold, L., Race, D., Hoy, C., Ashe, M. C., Wharf Higgins, J., & McKay, H. A. (2015). Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 72, 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.034

- Oliver, R. M., Wehby, J. H., & Reschly, D. J. (2011). Teacher classroom management practices: effects on disruptive or aggressive student behavior [article. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2011.4

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume I). https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

- Osher, D., Bear, G. G., Sprague, J. R., & Doyle, W. (2010). How can we improve school discipline?. Educational Researcher, 39(1), 48–58. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.27764553&site=eds-live&scope=site https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09357618

- Pate, R. R., Mitchell, J. A., Byun, W., & Dowda, M. (2011). Sedentary behaviour in youth. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(11), 906–913. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090192

- Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading-comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476x(83)90019-X

- Peiris, D., Duan, Y., Vandelanotte, C., Liang, W., Yang, M., & Baker, J. S. (2022). Effects of in-classroom physical activity breaks on children’s academic performance, cognition, health behaviours and health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159479

- Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Borghese, M. M., Carson, V., Chaput, J. P., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Pate, R. R., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6 (Suppl. 3), S197–S239. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0663

- Rachlin, H. (1989). Judgment, decision, and choice: A cognitive/behavioral synthesis [Bibliographies]. W.H. Freeman. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b1505890&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Rossi, L., Behme, N., & Breuer, C. (2021). Physical activity of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic – A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111440

- Salmon, J., Arundell, L., Cerin, E., Ridgers, N. D., Hesketh, K. D., Daly, R. M., Dunstan, D., Brown, H., Della Gatta, J., Della Gatta, P., Chinapaw, M. J. M., Shepphard, L., Moodie, M., Hume, C., Brown, V., Ball, K., & Crawford, D. (2023). Transform-us! cluster RCT: 18-month and 30-month effects on children’s physical activity, sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk markers. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(5), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-105825

- Salmon, J., Arundell, L., Hume, C., Brown, H., Hesketh, K., Dunstan, D. W., Daly, R. M., Pearson, N., Cerin, E., Moodie, M., Sheppard, L., Ball, K., Bagley, S., Paw, M. C., & Crawford, D. (2011). A cluster-randomized controlled trial to reduce sedentary behavior and promote physical activity and health of 8-9 year olds: The transform-us! study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 759. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-759

- Salmon, J., Mazzoli, E., Lander, N., Contardo Ayala, A. M., Sherar, L., Ridgers, N. (2020). Classroom-based physical activity interventions. In (pp. 523–540). Deakin University. https://dro.deakin.edu.au/articles/chapter/Classroom-based_physical_activity_interventions/20672796.

- Schmidt, M., Benzing, V., & Kamer, M. (2016). Classroom-based physical activity breaks and children’s attention: Cognitive engagement works! Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1474. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01474

- Shane, H. G. (1981). Significant writings that have influenced the curriculum – 1906–81. Phi Delta Kappan, 62(5), 311–314. <Go to ISI>://WOS:A1981KW22700005

- Singh, A. S., Saliasi, E., van den Berg, V., Uijtdewilligen, L., de Groot, R. H. M., Jolles, J., Andersen, L. B., Bailey, R., Chang, Y. K., Diamond, A., Ericsson, I., Etnier, J. L., Fedewa, A. L., Hillman, C. H., McMorris, T., Pesce, C., Puhse, U., Tomporowski, P. D., & Chinapaw, M. J. M. (2019). Effects of physical activity interventions on cognitive and academic performance in children and adolescents: A novel combination of a systematic review and recommendations from an expert panel. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(10), 640–647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098136

- Skiba, R., Ormiston, H., Martinez, S., & Cummings, J. (2016). Teaching the social curriculum: Classroom management as behavioral instruction. Theory into Practice, 55(2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148990

- Smith, C. P., King, B., & Gonzalez, D. (2016). Using multimodal learning analytics to identify patterns of interactions in a body-based mathematics activity. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 27, 355–379.

- Smith, C. P., King, B., & Hoyte, J. (2014). Learning angles through movement: Critical actions for developing understanding in an embodied activity. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 36, 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmathb.2014.09.001

- Subban, P. (2006). Differentiated instruction: A research basis. International Education Journal, 7(7), 935–947.

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2008). What we know and need to know about preventing problem behavior in schools. Exceptionality, 16(2), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362830801981138

- The Council of Chief State School Officers. (2018). Revising the definition of formative assessment. https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/Revising%20the%20Definition%20of%20Formative%20Assessment.pdf.

- Tremblay, M. S., Aubert, S., Barnes, J. D., Saunders, T. J., Carson, V., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., Chastin, S. F. M., Altenburg, T. M., Chinapaw, M. J. M., & Participants, S. T. C. P. (2017). Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) – Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8

- Tremblay, M. S., LeBlanc, A. G., Kho, M. E., Saunders, T. J., Larouche, R., Colley, R. C., Goldfield, G., & Gorber, S. (2011). Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-98

- van Sluijs, E. M. F., Ekelund, U., Crochemore-Silva, I., Guthold, R., Ha, A., Lubans, D., Oyeyemi, A. L., Ding, D., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2021). Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: Current evidence and opportunities for intervention. The Lancet, 398(10298), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01259-9

- Vaughn, M. (2020). What is student agency and why is it needed now more than ever? Theory into Practice, 59(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1702393

- Verburgh, L., Königs, M., Scherder, E., & Oosterlaan, J. (2014). Physical exercise and executive functions in preadolescent children, adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(12), 973–979. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091441

- Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H., Best, K., & Hesketh, K. D. (2017). Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0569-9

- Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H., & Hesketh, K. D. (2019). Process evaluation of a classroom active break (ACTI-BREAK) program for improving academic-related and physical activity outcomes for students in years 3 and 4. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 633. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6982-z

- Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment [Bibliographies]. Solution Tree Press. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00097a&AN=deakin.b3288675&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(4), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196322

- World Health Organization. (2022). Global status report on physical activity 2022.

- Yıldırım, M., Arundell, L., Cerin, E., Carson, V., Brown, H., Crawford, D., Hesketh, K. D., Ridgers, N. D., Te Velde, S. J., Chinapaw, M. J. M., & Salmon, J. (2014). What helps children to move more at school recess and lunchtime? Mid-intervention results from Transform-Us! cluster-randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092466