Abstract

Based on ethnographic fieldwork at two Syrian organizations, the Syrian Archive and Bidayyat, both founded in exile but operating at different ends of the archival scale, this article theorizes the idea of an archive as a horizon of expectation that orients activists toward future justice in the face of defeat. While Bidayyat primarily associates the power of the archive with the judgment of history and the Syrian Archive with legal judgment, their underlying idea of an archive gives activists a sense of an ending, even when justice proves elusive.

BEGINNINGS OF AN END

There’s a small apartment in a nondescript suburb of Berlin () where, in the summer of 2019, the web crawler at the Syrian Archive offices was always on, day and night, scraping the servers of platforms that hosted “more minutes of video from Syria than there have been minutes of real time since 2011” (Deutch Citation2020; Greenberg Citation2016). If all the content from Syria uploaded on YouTube were compiled, it would take over 40 years to watch (Jeff Deutch, interview, June 2019).

Figure 1. The Syrian Archive’s offices in Berlin. (Image source: https://en.qantara.de/content/the-syrian-archive-netting-the-war-criminals; accessed March 26, 2023)

The web crawler downloaded the user-generated content (UGC), particularly audiovisual data and metadata, from social media platforms to an offline server. The data were then stored offline on magnetic tape, safe from deletion, takedowns and deterioration. Alongside the web crawler a dozen employees plus a fluctuating number of volunteers also worked in this modest apartment—just a couple of offices, a meeting room with a server blinking in the corner, and a kitchenette. Together they attempted to verify and investigate UGC using open-source tools. Once verified, their investigations could be published online in reports detailing crimes and violations. Most ambitiously the Syrian Archive team launched investigations aimed at constructing legally-felicitous evidence that they hoped would one day be used in an international tribunal. In the meantime, they established “chain of custody” protocols for archiving footage and metadata, so that they would be of “trial-ready standard” for future investigators.

At the other end of the archival scale, in a hotel in Istanbul about a year earlier, in June 2018, I was at a workshop organized by Bidayyat, a Syrian diasporic documentary film production organization, founded in Beirut in 2013 to train young media activists to repurpose their footage for creative documentaries. Many of the participants had crossed into Turkey from northern Syria to take part in this workshop (). Only two of the dozen participants would cross back to continue working as media activists: most either stayed in Istanbul or used the crossing as a first step of a longer journey into the European Union. At the workshop, there was a sense that the Syrian revolution had been overtaken by a grinding proxy war fought on Syrian soil, on behalf of foreign backers, with no clear end in sight, and devoid of a revolutionary horizon.

The activists brought small hard-drives storing footage they had themselves shot or that belonged to the media office (maktab i‘lāmī) they were part of, and over which they could claim a share of the collective ownership. It was striking how they all referred to these hard-drives as their “arshīf,” their archive. I asked why they were calling personal hard-drives full of uncategorized, often not-uploaded clips, “an archive.” They would proudly explain the period that their archives covered, and how many “teras” or “gigas” the hard-drives contained. But surely, I would reply, these weren’t archives: the clips were unsorted and inaccessible to anyone but the activists themselves; at best they were collections, more like hoards. When I pressed them on the point, I landed on “audiovisual data” as a more accurate term.

Why “archive”? What was behind these activists’ idea of an archive? By 2018, the activists in the workshop were willing to admit that the Syrian revolution, despite their ongoing commitment to the cause, wasn’t going to overthrow the Assad regime, an aim they’d spent years struggling and sacrificing for. Despite the crystallization of a certain kind of defeat, they hadn’t given in to despair. By bringing their hard-drives with them, they had salvaged something from their displacement for a new life in diaspora. Their expectations shifted to the idea of an archive and to different kinds of justice associated with it. In the wake of the years of revolution and siege, calling hard-drives loaded with uncategorized and unverified video clips an “archive” gave this data in diaspora a certain status, pointing them toward their next political project.

It was striking that they didn’t speak of these archives in the conditional tense, as traces of the past that might prove useful in the future. While they admitted that both the peaceful and the armed struggles were lost, they were adamant that their footage contained evidence of historical, political and legal importance—either evidence of crimes, or the history of the revolution in their local area, and often both. Whether investigated for evidence or edited into narratives, these archives were going to lead at best to future legal justice, and at least to countering historical amnesia for generations to come. That, in the face of defeat, was the defiant mood in the workshop, and it was how they explained the idea of an archive.

The aim of this article is to give an account of how the idea of an archive forms a horizon of expectation for activists in the face of defeat. It’s based on ethnographic fieldwork at two Syrian organizations, both founded in exile but operating at different ends of the archival scale. While Bidayyat primarily associates the power of the archive with the judgment of history (see Scott Citation2020 for a critique of this kind of expectation) and the Syrian Archive with legal judgment (Dubberley, Koenig, and Murray Citation2020 have an analysis of the experiences of attempting to use digital documentation as a new paradigmatic document in an international tribunal), I argue that both draw from canonical critical theories on the relations between archives and power. Across different scales, the idea of an archive contains an implicit narrative structure, giving activists a sense of an ending even while justice proves elusive.

IS IT AN ARCHIVE?

As Sune Haugbolle (Citation2019) has detailed, the idea of an archive and the kinds of transitional (as opposed to revolutionary) justice that it promises haven’t always been popular amongst Syrian opposition activists. I am not alone however in noticing an uptick in Syrian activists’ uses of the term; Saber and Long (Citation2017) have posed the same question to a media activist from Deraa using the term: if this is an archive, then is he “an archivist”? "No," he replied.Footnote1 They ask whether it’s “enough that its author sees it as an archive, for us to accept the definition …?” (Saber and Long Citation2017, 6) They don’t directly answer this question, but instead turn to Foucault’s influential definition of the archive as “the law of what can be said,” before coining the concept “crowd-sourced citizen archive.” Drawing on Ariella Azoulay’s reading of Derrida, Saber and Long argue that by calling their footage an archive, activists make radical political and conceptual claims on the archive’s temporal (re)structuring: “By so doing, [activists] … democratised the archive, and transformed the Daraa material from a trace of the past, to an object of the present” (Saber and Long Citation2017, 17).

David Zeitlyn (Citation2012, 467) recently warned of the dangers of “extension” of the term "archive": “If everything is an archive, then what do we call the buildings that house the old files?” While similarly engaging with the relation between emic and etic uses of the term, this article doesn’t argue that something is an archive just because a person or a group says so. As with Talal Asad’s (Citation2009 [1986], 2–3) critique of Michael Gilsenan’s definition of Islam—“that Islam is simply what Muslims everywhere say it is”—such an approach wouldn’t help adjudicate between contradictory definitions from other authoritative claimants. In both of the cases that I discuss, it’s through institutions that material is authorized as being archival. The aim however isn’t to formulate an orthodox definition, then measure it against the institutions or documents that activists have referred to as an archive. Instead, I’m concerned with why the idea of an archive (which can remain untouched by an authority adjudicating whether something is actually an archive) became pervasive in the wake of defeat, when expectations of the revolutionary overthrow of the Assad regime had faded.

In this essay, I place two different kinds of archive in dialogue, one aiming primarily at the production of legal evidence and the other at historical narratives. On the one hand, this dialogue reveals how technics—the essential and universalizing features of a form of mediation—structure the production of documentation, for example by producing a proliferation of digital material uploaded to the “cloud.” Conversely, it also shows how a particular place at a particular time (such as the siege of Yarmouk) can reciprocally set radical limits on technics.Footnote2 Thus, despite the proliferation of material, the article remains indebted to the historical and ethnographic technics of reading both along the archival grain (Stoler Citation2009) and “against the limits” of the archive (Hartman Citation2008). In the aftermath of imperial, colonial or state violence this can involve “measuring silences” (Spivak Citation2010), or what has been called the formulation of a “negative methodology” (Navaro Citation2020), a methodology which can make an originary silence speak through parafictional strategies such as “critical fabulation,” while maintaining a “narrative restraint” (Hartman Citation2008). By placing two archives of vastly different scale side by side, digital proliferation might seem to challenge such theorizations of archival dearth and absence. Despite this proliferation however the critical moment or event, as in the account of a Syrian Archive investigation into hospital bombings, can remain elusive. Placing these two archives in dialogue is an attempt to stage a dialectic between trace and absence, law and history, document and narrative, evidence and art, speech and silence, proof and truth, in the theoretical dramas that archives enact in the scholarly literature.

As David Zeitlyn has noted (2012, 462), since archives can be both repositories and the materials contained in them, scholars frequently “exploit the slippage between these two senses, pitting them against each other.” This essay also considers how activists exploit both senses. Crudely the Syrian Archive is at the same time a repository and the material contained in it, while the archives (sing. arshīf) mentioned by the would-be Bidayyat filmmakers were exclusively material. In addition, the essay grapples with a third sense: how the idea of an archive affects institutional structures, what material gets deposited, and the ways the material should be investigated or “read.”

As a result, I continue a tradition of thinking of the archive not only as “source” but also as “subject,” as a “metaphoric invocation for any corpus of selective collections and the longing that the acquisitive quests for the primary, originary, and untouched entail” (Stoler Citation2009, 44–45). As I hope to show, however, the idea of an archive involves a temporal shift from the originary and primary, one that begins with a sense of an end, in the sense of both telos and eschaton.Footnote3 As Arjun Appadurai argues, “Rather than being the tomb of the trace, the archive is more frequently the product of the anticipation of collective memory. Thus the archive is itself an aspiration rather than a recollection” (Citation2012, xxx). It’s this horizon of expectation—pace Appadurai, recollection as aspiration—that emerged as a leitmotif during fieldwork when activists discussed ideas of an archive. As Koselleck argues, “Concrete history [is] produced within the medium of particular experiences and particular expectation” (Citation2004, 258). Here the archive—as both idea and technology, concept and technics—becomes the site of mediation between experience and expectation.

As a result, I draw on a useful distinction made by Ghassan Hage between “defeat” and the “sense of defeat.” Despite sounding almost identical, Hage argues that as social facts the two can work in opposite directions: "while defeat can be seen as an original accelerator of their sense of decline and decay, clinging to its memory [the sense of defeat] worked in the opposite direction. Paradoxically, it became an antidecay ‘maintenance’ mechanism, a desperate attempt at forging for themselves what I will call ‘a fantasy of viability’ that made life bearable and livable" (Citation2021, 120). While the archive preserves material from the past, the idea of an archive orients activists toward the future. It’s an idea drawn in part from readings of various canonical critical theories on the relationship between the archive and power. These theorizations help activists persevere despite repeated setbacks, including when archival practices misfire or fail to make good on expectations of justice.

Two conceptualizations of the archive loom large over the practices I encountered, both already mentioned in the discussion of Saber and Long. The first is the widely cited claim from Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge that the archive is not “the sum of all texts” but rather “the law of what can be said” (Citation1972, 129). Thus different kinds of power structure its grammar—what an archive can and cannot say (Trouillot Citation1995). The second is from a footnote in Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever, which reads, “There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation” (1988, 4). For archival activists these two theorizations can be called paradigmatic. Here I am less concerned with whether or not these are the “correct” scholarly interpretations than with how they are taken to demonstrate that the archive is essential to the constitution of (state) power, while also offering a hope that power can be harnessed or “democratized.” On the one hand, these theorizations warn activists not to reproduce the archival practices of state powers, as noted in the reflections by founding members of the Syrian Archive (Deutch Citation2020; Deutch and Habal Citation2018). On the other hand the imbrication of archives and power presents an opportunity to formulate an archival practice that can counter state power by challenging state narratives (Deutch and Para Citation2020, 167–68), or the state “monopoly” on the “means of evidence production” (Weizman Citation2017, 64).

As Leyla Dakhli recently noted, the Arab Spring and its subsequent counter-revolutions have led to two separate but related trends: “the opening (even sometimes in a very ephemeral way) of once inaccessible or invisible state archives… and the multiplication of private archiving initiatives, documenting revolts and revolutions but also older memories” (Citation2022, 75). This division of archival trends—wresting open the doors of state archives, and establishing a private (counter-)archive—also plays out in Syria post-2011.Footnote4 During my fieldwork activists frequently mentioned the undocumented Hama massacre of 1982 as an originary absence that their own documentary impulse attempted to rectify (Ismail Citation2018, 134–58). Cécile Boëx (Citation2018) has noted how new images and documents suddenly started circulating online after the 2011 uprising. There are also ongoing systematic attempts to collect documents seized from state institutions in rebel-held areas of Syria by organizations such as the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (Burgis-Kasthala Citation2021). Across the spectrum noted by Dakhli there is no shortage of archival initiatives in Syria or the region more broadly. In fact there is no shortage of evidence of crimes, including documents, like the Caesar Files, in which the state details its own bureaucratic acts of killing (Le Caisne Citation2015). Yet power has not been democratized and justice remains elusive. And yet archival initiatives continue unabated, so that the idea of an archive has become more not less prevalent (Haugbolle Citation2019). Why, in spite of the proliferation of evidence and dearth of justice, do activists persevere with these archives? What bearing does the idea of an archive have on their perseverance?

These various archival initiatives are founded in a region beset by the ongoing destruction and disappearance of media archives from imperial and colonial powers (Estefan Citation2022; Shafik Citation2022). But the Arab revolutions also proved that destruction, archival or otherwise, is primarily being undertaken by the postcolonial states that inherited the mantle of anticolonial struggle. More troublingly Assad’s Syria is a state formation that legitimizes itself by claiming to ensure an ongoing anticolonial struggle against Zionism, even while inflicting starvation sieges on Palestinians in the Damascus suburb of Yarmouk. Thus, for Bidayyat, their selection of one activist archive is partly to build a narrative that can debunk the Assad regime’s anticolonial credentials, a counter-shot documenting the brutal treatment of Palestinians in Syria. Like the Arab revolutions that theorists once claimed were inaugurating an era “after postcoloniality” (Abourahme Citation2013; Dabashi Citation2012), the idea of archive reemerges as an attempt to counter the narrative of the postcolonial state and thus continue the revolutionary attempt to move beyond it, and perhaps beyond postcoloniality.

One of the questions that frequently gets asked about the idea of a postcolonial archive is: What should an archive that counters prevailing power look like? As Elizabeth Povinelli has argued, “if ‘archive’ is the name we give to the power to make and command what took place here or there, in this or that place, and thus what has an authoritative place in the contemporary organization of social life, the postcolonial archive cannot be merely a collection of new artifacts reflecting a different, subjugated history” (Citation2011, 152). Povinelli thinks through what it would mean to find and found an archive that helps “the otherwise” endure in the face of or within power; but she ends with the downbeat realization that there’s an ineluctable kind of postcolonial tragedy to these attempts. She describes being conscripted into the formation of a counter-archive which is—despite the best intentions and all the techno-political subtlety at her disposal—futile at the last instance in the face of power. Discussed here are similar attempts to strive for an end in spite of both practical setbacks and theoretical suggestions that it may remain out of reach.

Many scholars have noted the future orientation of archives, of traces from the past preserved for an unspecified future. Assmann, for example, has made a distinction between passive and active preservation (Citation2008, 98–99), following Burkhardt in calling documents addressed intentionally to the future “messages” and those that don’t “traces.” In Derrida’s celebrated essay the power of the archive is ontological; like all desire our mal d’archive is insatiable, initiating a drive in search of an originary, always-already, lost trace. By dint of this drive the archive ceases to orient to the past, and propels one toward the future. Thus Derrida argues the concept of the archive is “a question of the future, the question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow” (1998, 36).

Here there’s a different emphasis. The archival documents discussed here do not constitute messages in Burkhardt’s sense. However, rather than beginning with a search for a trace and then being propelled intentionally or not into the future, the idea of an archive begins as a search for future justice. Frank Kermode (Citation2000, 105) has argued that the search for ends is fundamental to the narrative or plot of justice, the way that humans attempt to systematize, give order to—or lay fictions over—“reality,” in the sense of “a world irreducible to human plot and human desire for order.” Aiming at justice, the idea of an archive has a narrative structure to it. Like tick then tock, if the beginning is an idea of an archive then the end is an idea of justice. Working on their archives in exile the activists find themselves in the midst of a struggle, which some at the Syrian Archive called intervening in “real time,” aiming to implement a turning point in time, which one could call a peripeteia. Within this generic narrative structure of the idea of an archive, adopting a new technology, such as a machine-learning algorithm for recognizing cluster munitions, works as a plot device, which media activists hope will precipitate a reversal in fortunes and so lead them to their end.

This isn’t to say that the idea of an archive is merely a consoling fiction—although my interlocutors certainly did draw consolation from it. What emerges from the two ethnographic accounts below, I hope, is not a kind of cruel optimism: a subject unable to relinquish a bad object in spite of its role in hastening their demise, the kind of attachment the ethnographer can diagnose from an “analyst’s perspective” (Berlant Citation2011, 24–25). The Syrian revolution and war have proved more tragic than that; it’s a situation in which both quiescence and activism have led to demise. Today one choice facing activists is whether to construct art or evidence, whether to place their faith in the judgments of law or history. Instead of the kind of analyst’s perspective that might judge which of those choices is crueler or more astute, my task is to sketch how both theories and practices interact in producing the temporal orientations of the idea of an archive. It’s an attempt to show that, at least for the time being in exile and in diaspora, the idea of an archive begins as a search for ends, not origins.

THE END OF LEGAL JUSTICE

The Syrian Archive was set up in 2014 by Hadi al-Khatib in Berlin, but the idea had come to him earlier:

Whenever I met people, they would complain about losing their digital documentation—for example, because of defective computers and hard-drives; or their phones and laptops were seized by the Turkish Gendarmerie during border crossings and raids of unregistered NGOs. Sometimes evidence was incinerated in regime airstrikes, and sometimes it was seized by rebel groups… There are so many reasons why the material was lost. I observed that there was a need for a repository, a safe place where documentation can be protected.Footnote5

In 2013 Hadi al-Khatib met Eliot Higgins, who was setting up the organization Bellingcat after the success of his blog, Brown Moses. They collaborated on an investigation into the use of ex-Yugoslavian weapons supplied to Syrian rebels (via Croatia) by the U.S. and Saudi governments (Brown Moses Citation2013). What came to be known as “online open-source investigations” brought together amateurs with digital know-how who would analyze and verify user-generated content (UGC), before publishing their findings and methods online in a commitment to “transparency, verifiability, and replicability” (Elliot Higgins, interview, April 25, 2023).

For media activists, this method of online open-source investigation opened up a horizon for hope as the revolution was becoming a proxy war, a hope which still imbues the Syrian Archive. In the space of a few months, Brown Moses broke more stories than many journalists manage in their whole careers. These successful investigations drove the hope that verified UGC could in future act as legally felicitous evidence in an international tribunal adjudicating war crimes or crimes against humanity. In 2014, after Bellingcat secured regular funding from the Google and Open Society Foundations, Hadi al-Khatib became their second full-time hire (Higgins Citation2021, 107). Bellingcat in turn funneled funding to the Syrian Archive, co-publishing Syrian Archive investigations on its website. In the process the Syrian Archive was pioneering methods of UGC preservation so as to preserve a “chain of custody.” This, they argue, will make archived footage admissible in court at some future date (Yvonne Ng, in Dubberley, Koenig, and Murray Citation2020).

The Syrian Archive had been founded to protect against UGC take-downs in the “digital war” between antagonists. In 2017, however, the takedowns “exploded… 400,000 anti-regime activist videos were taken down overnight… 1500 people reached out,” as I was told by Jeff Deutch, lead researcher at the Syrian Archive.Footnote6 After a series of attacks by ISIS in Europe, YouTube and other social media platforms had responded to pressure from Western governments by updating their user agreement policies. The platforms began using machine-learning algorithms to systematically remove user-generated content categorized as “terrorist.” Almost overnight the platforms removed more than 10 percent of the videos from Syria posted online since 2011 (Al-Khatib and Kayyali Citation2019). Deutch remembered activists’ panic: “This is my footage, my channel was shut down: can you help me?”

The Syrian Archive began to liaise with Silicon Valley giants to have clips and accounts restored while lobbying them to stop using machine-learning algorithms on Syrian UGC. The platforms replied that the sheer volume of uploaded content (300 hours are uploaded per minute on YouTube) made relying on human moderators impossible. For activists, not only were the algorithms unaccountable black boxes trained on opaque data-sets; social media platforms also had no clear definition of keywords such as “terrorist” (YouTube ads policy specialist, interview, November 6, 2015). The platforms’ concerns were also primarily commercial, making the broadest definition of terrorist content “whether or not we’d be willing to run an ad before it” (YouTube ads policy specialist, interview, November 6, 2015). YouTube’s particular concern with the possibility of running a sponsored advertisement before a clip of a beheading didn’t mean the content would eventually have been taken down without pressure from Western governments, but did suggest that the vast majority of footage uploaded by Syrian media activists was already considered suspect years before the machine-learning takedowns.

To make matters more complicated, Hadi al-Khatib explained, it’s often the violent content considered at risk of “radicalizing” viewers that also contains evidence of crimes. Against the background of commercial priorities, platforms theoretically faced a dilemma: humanitarian evidence or terrorist content? They reacted without hesitation, opting to automatically remove suspect content via algorithm. The “net,” according to Hadi al-Khatib, was cast calamitously wide.

Thus, by the time I began fieldwork there in 2019 there were two main aspects of the Syrian Archive’s work: preserving UGC, including by liaising with social media giants to restore footage; and turning it into legal evidence. In turn, the Syrian Archive faced three overlapping constraints working with the “accidental archives” of online platforms (Deutch Citation2020, 5056): the fact that these are huge companies that have been granted a license by users to the content they’re archiving (capital); that the sheer volume of content entails regulation by machine-learning algorithms over human moderators (technics); and that powerful states can pressure platforms to change the user-agreement policies (state power).Footnote7

Despite adopting the term for the title of his organization, Hadi al-Khatib remained wary of some of its conceptual resonances: “An archive is a librarian’s word dealing with a historian’s content. But we are dealing with a conflict right now, not in the future.” Dealing with a “conflict right now” seems to make the futurity of archival work not only secondary but objectionable too. There’s a need to constantly bear the present in mind, to prioritize what Hadi called “real-time effects.” The Syrian Archive isn’t investigating events as they occur (as Bellingcat does), but rather building up archives of incidents from the recent past which they investigate for a (possible) future tribunal. Hadi al-Khatib suggested that this notion of “real-time effects” can seem contrary to the point of archival practices, which are typically aimed at preserving the past for the future: “the Syrian Archive is a move away from the archive and memory—because that can be an offensive thing for some people. It’s not memory; it’s what we’re living!” By prioritizing work that bears most profoundly on struggle in the present, Ariella Azoulay might argue (Citation2017) that the Syrian Archive undermined the temporal “distancing” identified as a feature of state control over the archive. Real time however proved a slippery temporality.

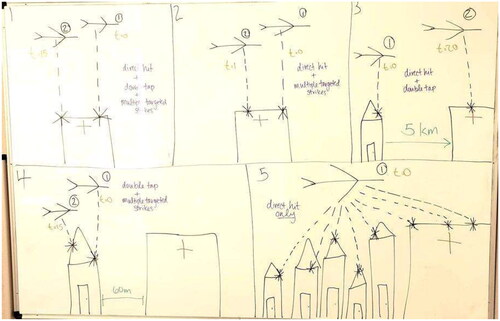

With the aim of having a “real-time effect” I spent a month participating in an investigation on the aerial bombardment of medical centers in Syria, as part of my doctoral fieldwork. I give a fuller account in my dissertation (Tarnowski Citation2022), but briefly the Syrian Archive had identified 410 incidents indexed by over 2000 user-generated videos. Out of this proliferation of content, however, I was told by the legal expert working on the investigation, Libby McAvoy, that we had probably only one verified “open-and-shut case,” proved on the basis of the legal concept of a “double tap” (). The primary obstacle wasn’t the amount of documentation we had but rather the kind: video footage could more easily be used to establish that an attack took place (actus reus) than to prove intent (mens rea). Both elements are necessary to construct legally felicitous evidence. This in fact is a well-known hurdle in any attempt to use “video as evidence” (WITNESS Citation2021, 21–35).

Figure 3. Carving out the legal concepts: double tap; single direct hit; multiple targeted strikes. (Author’s photograph, July 2019)

Sandra Ristovska (Citation2019) has theorized the Syrian Archive as being “visual experts” who work at the interface between NGOs, Internet companies and international courts. Together with collaborators including academics, lawyers and investigators, they aim to establish new protocols, knowledge and objects so as to instigate what Kelly Matheson, the head of Video as Evidence at WITNESS, has called a “paradigm shift”; so that open-source content becomes the new paradigmatic form of evidence, akin to state documents at the Nuremberg trials. Matheson argues that this might already be the case: “Whereas before, witness testimony had been at the core of [human rights cases], now, increasingly, the core is open source material—and then the witnesses and the documents come in at the edges” (Dubberley, Koenig, and Murray Citation2020, 41). This is an end that feels imminent. During my fieldwork however it was also clear that the process of instigating this paradigm shift involves frequent setbacks. In the case of investigation into hospital bombings, the outcome wasn’t a new kind of evidence tested in a trial, but a modest report published on the Syrian Archive’s website.Footnote8

Despite this apparent setback, the Syrian Archive perseveres in attempting to navigate a series of technical, legal and political hurdles that will have to be overcome to transform UGC into evidence. In a follow-up interview Jeff Deutch explained that they were changing their approach by attempting to think through what he called “new ontologies” of evidence and incidence, including attempting to formulate a statistical approach to intentionality in cases of aerial bombardment, and a machine-learning approach to incidence in cases of cluster munition usage (interview, April 28, 2023). As with justice more broadly, having a “real-time effect” can be postponed indefinitely, even as it shapes archival practices in the present, and gives activists a seemingly imminent end to aim for.

The Syrian Archive also has a distinctively national aim, which works to (re-)orient expectations in a more conventional archival sense: traces from the past preserved for an indefinite future. Hadi al-Khatib explained that the process of archiving was also “not memory” in contrast to the Syrian state initiative, Wathīqat watan (The Nation’s Documentation). In 2011 Bashar al-Assad’s spokesperson Buthaina Shaaban set up Wathīqat watan to collect witness testimonies from regime soldiers and their families. Unlike the Syrian Archive, however, “It doesn’t store user-generated content. The witness testimonies are intended to keep [the regime] ruling future generations, and future generations therefore have to know that they’re fighting terrorism [rather than a popular revolution]. The Syrian Archive needs to counter that as an institution.” User-generated content, from this perspective, is used to create a counter-archive to Syrian state archives, and thus a counter-narrative to the state narrative.Footnote9 Hadi al-Khatib predicted that:

In the future, the Syrian Archive will become an institution that people can visit and see in the long term. There will be access without restrictions. And that’s important for future generations. It will be better that way as an institution. It’s important to play the role of the constant digital memory of the Syrian people. This is very important because everyone is trying to create their own narrative.

A distinction between two kinds of archive and two juridical paradigms was also being drawn: the regime’s one, based on the memory practices of witness testimony by soldiers and their families; and the Syrian Archive’s, based on transparent, verified, replicable online open-source investigations. The first belongs to what Anette Wieviorka (Citation2006) has criticized as the “era of the witness”; the second to a particular, digital version of what Eyal Weizman (Citation2017, 82–83) has celebrated as “a forensic turn,” meaning “the art of making claims using matter and media, code and calculation, narrative and performance.” Weizman’s theorizations would dispute and nuance a binary distinction, but the former (i.e. testimony) is taken to be subjective and falsifiable, and the latter (forensics) replicable and verifiable. Constructing a particular kind of archive, one that collects digital matter and code documenting human rights violations, as opposed to oral testimonies from soldiers, will ensure what kind of story can be written about Syria. In theory, the archive is, or “will have been” (Derrida Citation1998, 17), the basis for political recognition (Abu El-Haj Citation2012, 183; Povinelli Citation2002), legitimizing either regime or revolution, either the postcolonial Syrian state or a state formation that comes after postcoloniality.

The idea of the archive works as both an aspiration and a limitation for the Syrian Archive, one that structures its temporal horizons. As Hadi al-Khatib told me,

There’s an offensive part: this is not something for history in the future, as [is the case] with archives in their traditional meaning; but also, it is [an archive of history for the future] because otherwise it’s going to be forgotten. It’s about saying, What you did as media activists was not for nothing. They really did risk everything to make sure they captured what they witnessed. We started the archive in the middle of this shit.

On the one hand, “real-time” investigations will precipitate justice; on the other, archives will be the basis for a future state formation. With Frank Kermode (Citation2000) we can call the temporality of the former sense of justice imminent,Footnote10 and the latter immanent. When the imminence of justice suffers a setback, such as when a “real-time” investigation doesn’t make it to court and UGC can’t be tested as evidence, then the immanence of justice to this kind of archive can step in. While contrapuntal, both kinds of “End-feeling” (Frank Kermode Citation2000, 25) work in concert. In that sense, despite being “in the middle of this shit,” whether striving for transitional justice or post-Arab Spring state formations, there’s always an end in sight for the archive, even if it’s out of reach.

THE END OF HISTORICAL JUSTICE

There’s a short video clip shot in 2013 during the siege of Yarmouk but that was never uploaded online. It shows a turtle slowly eating a leaf (). In the background two or three people bicker:

Figure 4. Still from an untitled short by Abdallah al-Khatib, 9 April 2021. (https://youtu.be/Zy40OoM80Ac. Accessed March 26, 2023)

Qusay: Why are you filming? For God’s sake, stop filming meaningless clips. Our hard-drives are full of them. I’m just going to delete it. Khaled: What’s your problem? Qusay: My laptop is full of videos. I need to free up space: it keeps crashing. Khaled: Just use a normal computer. Qusay: You think there are normal computers here? Khaled: Yes. Qusay: Where? [inaudible] Abdallah: We have four hard-drives. Let’s fill them. Qusay: They’re already full! [… cut]

In the midst of a starvation siege, Abdallah al-Khatib, a young Palestinian-Syrian activist and writer from Yarmouk camp, on the outskirts of Damascus, filmed a turtle slowly eating a leaf while activists discussed digital storage constraints. Cut off from electricity and the internet, Abdallah had to make conscious and difficult decisions about what to film and why, what to store on hard-drives and what to delete. His “archive,” despite being born digital and formed under general conditions of material proliferation, is consciously constituted through “gaps” and “silences.”

That scene illustrates how media activists under conditions of siege couldn’t rely on the affordances typically associated with the digital. It’s also emblematic of the kind of footage that Abdallah screened at a Bidayyat workshop in Istanbul, where I met the dozen or so activists from across Syria who all brought hard-drives of footage they called their “archive” (arshīf). Out of all the footage screened at that workshop Abdallah’s stood out. The political aesthetics of these scenes starkly differed from the humanitarian or journalistic discourses that most activists followed, including other participants who had documented the siege of Yarmouk. Bidayyat quickly made the decision to work with Abdallah on turning his footage into a documentary. Together, they spent the next three years painstakingly producing Little Palestine (Diary of a Siege), which tells the story of the siege of Yarmouk, and went on to win a number of prizes and screen widely (Al-Khatib Citation2021). I followed the process and ended up subtitling the film.

There was another young activist at the Bidayyat workshop called Utba. When it was his turn to play his footage he clicked through the clips available online from Daraya’s Local Council media office (majlis mahalliy Daraya), which he had participated in filming.Footnote11 This footage was also compelling, but in a different way. There were videos of columns of tanks queuing to enter the town; long shots of barrel bombs landing on buildings in the distance; documentations of weekly protests; women describing to a local journalist their terror after an airstrike. The clips demonstrated the deep roots of peaceful civic activism for which Daraya had become a beacon during the Syrian Revolution—a template for new kinds of local governance based on a notion of democratic pacifism derived from a heterodox Islamic tradition (Said and Jalabi Citation2000)—and the brutality with which it was crushed by Assad’s forces.Footnote12 The footage looked like evidence of historical and perhaps also legal importance. For other participants in the workshop, especially those who had survived similar sieges by Assad’s forces, the footage from Daraya was urgent and epic: “There are certainly films that simply have to be made for cinema, for the big screen, not just for TV,” Younis, a media activist from Ghouta, responded. “They might patch up our forgetfulness [ratiy al-nisyān].”

However, the workshop facilitators didn’t agree. Rania Stephan and Noe Mendell certainly felt that Daraya’s revolutionary history deserved to be told, but that Utba’s footage couldn’t be turned into a creative documentary. It didn’t tell a “story,” it had no “characters,” nothing “personal.” “The images,” as Rania Stephan later said, “aren’t imaginative.” The Daraya footage showed the institutional functioning of the local council, documenting it in quasi-bureaucratic ways, as well as the systematic destruction and depopulation of the neighborhood.

After watching the footage, Mohammad Ali Atassi, the founder of Bidayyat, who was also observing the workshop, drew a link with Delphine Minoui’s Les Passeurs de livres de Daraya (Citation2017). He described Daraya as “the peaceful Stalingrad of Syria,” lamenting that the regime killed two of its most prominent peaceful activists while in forced detention, Ahmad Shurbaji and Ghiath Matar. Noe Mendell, the head of the Scottish Documentary Institute, who was leading the workshop, explained that Utba’s “role would be to become a director, and that means giving meaning to this archive, especially because this is an old, preexisting archive.” Although she was too diplomatic to say it outright, the suggestion was that this would be too tall a task. As expected, the Daraya film never got made by Bidayyat.

What did one activist’s “archive” have that the other’s didn’t? Both archives were made up largely of footage shot during sieges of central importance for the course of the Syrian revolution and its repression. Both “archives” were repositories of more or less ordered documents that could serve as the foundation for a kind of history “writing” through documentary film. In fact one was more ordered than the other, and one archive probably more useful for writing a scholarly history than the other; but it was the material of lesser historical, legal—perhaps also archival—importance that would become the basis for a creative documentary. This anecdote seems to show that even on this most humble scale that promotes a minoritarian tradition of archival practice, the archive is guarded by archons, gatekeepers who decide who and what can enter.

Why didn’t the Daraya material measure up to Bidayyat’s idea of an archive? At the risk of oversimplifying, Abdallah al-Khatib had managed to go against the prevailing archival grain, to produce images for the future by following what Yael Navaro (Citation2020) has memorably called a “negative methodology,” a depiction of siege through its gaps and silences. His practice can certainly be celebrated for offering a kind of “reparative fabulation” (Estefan Citation2022) for an experience of extreme suffering that might in the other hands have strayed into the realm of the “unrepresentable” (Didi-Huberman Citation2012). Insisting on filming and storing, even in the midst of a starvation siege and despite vocal disapproval, scenes of a turtle slowly eating a leaf instead of chasing after events of legal or historic importance were emblematic of the quality of his footage: it was precisely what led to his archive being chosen for the production of Bidayyat’s final feature-length documentary. The flipside of course is that this stance toward political aesthetics entails a rejection of another kind of footage—less personal, more bureaucratic, devoid of storytelling—for a film documenting a siege that also deserves to be made, a historical narrative that also deserves to be told.

Mohammad Ali Atassi is certainly aware that there is a proliferation of histories from Syria that deserve to be told, especially in the aftermath of the revolution’s defeat. It’s by generating a “wealth of stories” through activists’ archives that it becomes possible to keep something of the revolution alive. These activists’ archives keep the revolution’s end in sight in the wake of a profound defeat:

Today, we’ve lost a country… I don’t know when we will return, or whether we’ll ever be able to return [to Syria]. But I don’t think we should lose our narratives, our stories. Our stories are not just the archive that will remain outside Syria, or our memory, but what we can do with that archive… The question is about what can be done. I think that’s very important, because the young women and men who today are in Berlin, Paris or Amsterdam, or even Istanbul and Beirut, their Syrian past has gone up in smoke, but it’s also still there in the material. And there’s another generation who left Syria aged eleven, who grew up outside Syria, and who don’t have direct access to the story of Syria. What’s important today is to attempt to keep alive this narrative on their behalf, whether they grew up abroad afterward in Europe or Lebanon, or even those internally displaced in Syria. What is that story? It’s that, for a while, there was a generation of people in the region who demanded dignity, freedom, and who took to the streets, and who were able to bring down regimes, and that those people were met with terrible violence. That’s the headline story. And within it there are lots of stories, a wealth of stories, related to all the details of ordinary lives lived. (Tarnowski Citation2023, 68)

CONCLUSION

Across these cases, the idea of an archive has remarkable resilience, reemerging unscathed in the face of political setback and conceptual impasse. Although the boundaries are somewhat blurred, each is used to construct a different paradigmatic kind of document, one evidence, the other narrative; and each of these archives aims at a different kind of justice, one historical, the other legal. But rather than criticize one or the other, or contrast faith in law with history, evidence with art, or proof with truth, I have tried to show that despite these differences the underlying idea of an archive orients these activists, not in search of origins or past traces but toward the ends of justice. Justice might never come, but the idea of an archive still bears the sense of an ending. For both Bidayyat and the Syrian Archive, the idea of an archive is the beginning of an idea about an end.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Andreas Bandak, Christine Crone, and Nina Grønlykke Mollerup from “Archiving the Future,” who organized the workshop in September 2022 at the University of Copenhagen, which this essay emerged from. I’m grateful for comments, questions, and encouragement from participants Chad Elias, Uğur Ümit Üngör, Sune Haugbølle, Tom Keenan, Dima Saber, Christa Salamandra, Lisa Wedeen and the two anonymous peer reviewers, as well as edits and incisive readings by Rania Stephan, Victoria Lupton, and Janine Su.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stefan Tarnowski

Stefan Tarnowski is currently an Early-Career Research Fellow at Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge, and a postdoctoral researcher on the “Views of Violence” project at the University of Copenhagen. He completed a Ph.D. in Columbia University’s Department of Anthropology and the Institute for Comparative Literature and Society in 2022. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]

Notes

1 See also the film project Our Memory Belongs to Us (Farah Citation2021), featuring Yadan Drajy and the “Daraa archive.”

2 For a critical discussion of the “cloud” and its limitless capacity for storage, see Hu (Citation2015). For a discussion of the way a milieu and a technical system can exist in reciprocal relationships, see Larkin (Citation2021).

3 See Haugbolle and Bandak’s (Citation2017) exploration of these two senses of the term “end” in relation to revolution, drawn from Derrida’s (Citation1969) distinction between eschaton and telos.

4 For a series of discussions on the “Arab Archive” since 2011, see the important collective volume The Arab Archive: Mediated Memories and Digital Flows (Della Ratta, Dickinson, and Haugbølle Citation2020).

5 All quotations are from author’s interview, in Berlin, July 23, 2019.

6 All quotations are from author’s interview, Jeff Deutch, Syrian Archive offices, in Berlin, July 1, 2019.

7 For a reading of the Syrian Archive in terms of the relationship between activist agency and the structural constraints of commercial platforms, see Anden-Papadopoulos (Citation2020). Internet governance has recently been discussed in terms of “four internets,” in which the particular balance between these three realms– technology, capital and the state–determines the kind of internet that arises (O’Hara, Hall and Cerf Citation2021). The confluence of constraints between new technologies and “neoliberal” economics has been captured by scholars such as Jodi Dean (Citation2005).

8 https://medical.syrianarchive.org/. Accessed June 16, 2023.

9 See also Üngör (Citation2019) and Iojain (Citation2018).

10 For a recent engagement with imminence, see Bandak and Anderson (Citation2022). I’m grateful to Nina Grønlykke Mollerup for this reference.

12 On Daraya and the experiments in revolutionary governance, see Yassin-Kassab and Al-Shami (Citation2016); Ayoub (Citation2019); and Al-Khalili (Citation2021).

13 For a recent example involving plans for the storage of nuclear waste, see Galison and Ross (Citation2015).

REFERENCES

- Abourahme, Nasser. 2013. “Past the End, Not yet at the Beginning.” City 17 (4): 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.829632

- Abu El-Haj, Nadia. 2012. The Genealogical Science: The Search for Jewish Origins and the Politics of Epistemology. Chicago Studies in Practices of Meaning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Al-Khalili, Charlotte. 2021. “Halaqas, Relational Subjects, and Revolutionary Committees in Syria.” focaal 2021 (91): 50–66. https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2021.910104

- Al-Khatib, Hadi, and Dia Kayyali. 2019. “Video: Opinion | YouTube Is Erasing History.” New York Times, October 23; https://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000006702129/syria-youtube-content-moderation.html.

- Anden-Papadopoulos, Kari. 2020. “The ‘Image-as-Forensic-Evidence’ Economy in the Post-2011 Syrian Conflict: The Power and Constraints of Contemporary Practices of Video Activism.” International Journal of Communication 14: 5072–5092.

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2012. “Archive and Aspiration.” Archive Public (blog), May 12; https://archivepublic.wordpress.com/texts/arjun-appadurai/.

- Asad, Talal. 2009. “The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam.” Qui Parle 17 (2): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.5250/quiparle.17.2.1

- Assmann, Aleida. 2008. “Canon and Archive.” In Canon and Archive, 97–108. Berlin, Germany: Walther De Gruyter.

- Ayoub, Joey (ed.). 2019. Enab Baladi: Citizen Chronicles of the Syrian Uprising. Istanbul, Turkey: Enab Baladi.

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2017. “Archive.” Political Concepts, July 21; http://www.politicalconcepts.org/archive-ariella-azoulay/#fn1.

- Bandak, Andreas, and Paul Anderson. 2022. “Urgency and Imminence: The Politics of the Very near Future.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 30 (4): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3167/saas.2022.300402

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Boëx, Cécile. 2018. “Between Life and Death. Liminal Images from the Syrian Revolt.” Bidayyat, January 30; http://bidayyat.org/opinions_article.php?id=176.

- Brown Moses. 2013. “Yugoslavian Anti-Tank Weapons Being Smuggled into Syria?” Brown Moses Blog, January 16; http://brown-moses.blogspot.com/2013/01/are-yugoslavian-anti-tank-weapons-being.html.

- Burgis-Kasthala, Michelle. 2021. “Assembling Atrocity Archives for Syria: Assessing the Work of the CIJA and the IIIM.” Journal of International Criminal Justice 19 (5): 1193–1220. https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqab065

- Dabashi, Hamid. 2012. The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism. London, UK: Zed Books.

- Dakhli, Leyla. 2022. “Archiving in an Age of (Counter)Revolutions.” In Altered States: The Remaking of the Political in the Arab World, edited by Sune Haugbolle and Mark LeVine. London, UK: Routledge (Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern Democratization and Government).

- Dean, Jodi. 2005. “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics.” Cultural Politics 1 (1): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.2752/174321905778054845

- Della Ratta, Donatella, Kay Dickinson, and Sune Haugbolle. 2020. The Arab Archive: Mediated Memories and Digital Flows. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Institute of Network Cultures; https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/tod35-the-arab-archive-mediated-memories-and-digital-flows/.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1969. “The Ends of Man.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 30 (1): 31–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/2105919

- Derrida, Jacques. 1998. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Deutch, Jeff. 2020. “Challenges in Codifying Events within Large and Diverse Data Sets of Human Rights Documentation: Memory, Intent, and Bias.” International Journal of Communication (Online) 14: 5055–5072.

- Deutch, Jeff, and Hadi Habal. 2018. “The Syrian Archive: A Methodological Case Study of Open-Source Investigation of State Crime Using Video Evidence from Social Media Platforms.” State Crime Journal 7 (1): 46–76. https://doi.org/10.13169/statecrime.7.1.0046

- Deutch, Jeff, and Niko Para. 2020. “Targeted Mass Archiving of Open Source Information: A Case Study.” In Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability, edited by Sam Dubberley, Alexa Koenig, and Daragh Murray. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2012. Images in spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz. Translated by Shane B. Lillis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Dubberley, Sam, Alexa Koenig, and Daragh Murray, eds. 2020. Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Estefan, Kareem. 2022. “Narrating Looted and Living Palestinian Archives: Reparative Fabulation in Azza El-Hassan’s Kings and Extras.” Feminist Media Histories 8 (2): 43–69. https://doi.org/10.1525/fmh.2022.8.2.43

- Foucault, Michel. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Galison, Peter, and Rob Ross. 2015. Containment. New York, NY: Film Sprout.

- Greenberg, Andy. 2016. “Google’s New YouTube Analysis App Crowdsources War Reporting.” Wired, April 20; https://www.wired.com/2016/04/googles-youtube-montage-crowdsources-war-reporting/.

- Hage, Ghassan. 2021. “Decay as Decline in Social Viability among Ex-Militiamen in Lebanon.” In Decay, edited by Ghassan Hage. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1

- Haugbolle, Sune. 2019. “Holding out for the Day after Tomorrow–Futurity, Memory, and Transitional Justice Evidence in Syria.” In Resolving International Conflict: Dynamics of Escalation, Continuation and Transformation, edited by Isabel Bramsen, Poul Poder, and Ole Waever. London, UK: Routledge.

- Haugbolle, Sune, and Andreas Bandak. 2017. “The Ends of Revolution: Rethinking Ideology and Time in the Arab Uprisings.” Middle East Critique 26 (3): 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2017.1334304

- Higgins, Eliot. 2021. We Are Bellingcat: An Intelligence Agency for the People. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Hu, Tung-Hui. 2015. A Prehistory of the Cloud. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Iojain. 2018. “The Project of Documenting the War on Syria.” Wathiqat wattan, June 28; https://en.wathiqat-wattan.org/452/the-project-of-documenting-the-war-on-syria.

- Ismail, Salwa. 2018. The Rule of Violence: Subjectivity, Memory and Government in Syria. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kermode, Frank. 2000. The Sense of an Ending. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Koselleck, Reinhart. 2004. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time. New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

- Larkin, Brian. 2021. “The Cinematic Milieu: Technological Evolution, Digital Infrastructure, and Urban Space.” Public Culture 33 (3): 313–348. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-9262849

- Le Caisne, Garance. 2015. Opération César : Au Cœur de la Machine de Mort Syrienne [Operation César: At the Heart of the Syrian Death Machine]. Paris, France: Stock.

- Minoui, Delphine. 2017. Les Passeurs de Livres de Daraya: Une Bibliothèque Secrète en Syrie. Paris, France: Seuil.

- Navaro, Yael. 2020. “The Aftermath of Mass Violence: A Negative Methodology.” Annual Review of Anthropology 49 (1): 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-010220-075549

- O’Hara, Kieron, Wendy Hall, and Vinton Cerf. 2021. Four Internets: Data, Geopolitics, and the Governance of Cyberspace. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1093/oso/9780197523681.001.0001/oso-9780197523681.

- Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2002. The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2011. “The Woman on the Other Side of the Wall: Archiving the Otherwise in Postcolonial Digital Archives.” differences 22 (1): 146–171. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1218274

- Ristovska, Sandra. 2019. “Human Rights Collectives as Visual Experts: The Case of Syrian Archive.” Visual Communication 18 (3): 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357219851728

- Saber, Dima, and Paul Long. 2017. “‘I Will Not Leave, My Freedom Is More Precious than My Blood’. From Affect to Precarity: Crowd-Sourced Citizen Archives as Memories of the Syrian War.” Archives and Records 38 (1): 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/23257962.2016.1274256

- Said, Jawdat, and Afra Jalabi. 2000. “Law, Religion and the Prophetic Method of Social Change.” Translated by Afra Jalabi. Journal of Law and Religion 15 (1/2): 83–150. https://doi.org/10.2307/1051516

- Scott, Joan Wallach. 2020. On the Judgment of History. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Shafik, Viola, ed. 2022. Documentary Filmmaking in the Middle East and North Africa. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2010. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Reflections on the History of an Idea. Edited by Rosalind Morris. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tarnowski, Stefan. 2022. “Struggling with Images: Revolution, War, and Media in Syria.” PhD diss., Columbia University, New York, NY.

- Tarnowski, Stefan. 2023. “A Link, a Courier, a Smuggler between Generations: An Interview with Mohammad Ali Atassi.” World Records 8 (May): 51–75.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit. 2019. “Narrative War Is Coming.” Al-Jumhuriya, June 7; https://www.aljumhuriya.net/en/content/narrative-war-coming.

- Weizman, Eyal. 2017. Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability. New York, NY: Zone Books.

- Wieviorka, Annette. 2006. The Era of the Witness. Translated by Jared Stark. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- WITNESS. 2021. “Video as Evidence Field Guide.” Video as Evidence (blog). Accessed May 19, 2021; https://vae.witness.org/video-as-evidence-field-guide/.

- Yassin-Kassab, Robin, and Leila Al-Shami. 2016. Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2012. “Anthropology in and of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (1): 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145721

FILMOGRAPHY

- Al-Khatib, Abdallah, dir. 2021. “Little Palestine (Diary of a Siege).” Bidayyat, for Audiovisual Arts, Films de Force Majeure.

- Farah, Rami, dir. 2021. “Our Memory Belongs to Us.” https://vimeo.com/539047720.